Abstract

Assessing children’s reasoning about food, including their health knowledge and their food preferences, is an important step toward understanding how health messages may influence children’s food choices. However, in many studies, assessing children’s reasoning relies on parent report or could be susceptible to social pressure from adults. To address these limitations, the present study describes the development of a food version of the Implicit Association Test (IAT). The IAT has been used to examine children’s implicit stereotypes about social groups, yet few studies have used the IAT in other domains (such as food cognition). Four- to 12-year-olds (n = 123) completed the food IAT and an explicit card sort task, in which children assessed foods based on their perception of the food’s healthfulness (healthy vs. unhealthy) and palatability (yummy vs. yucky). Surprisingly, children demonstrated positive implicit associations towards vegetables. This pattern may reflect children’s health knowledge, given that the accuracy of children’s healthfulness ratings in the card sort task positively predicted children’s food IAT d-scores. Implications for both food cognition and the IAT are discussed.

Keywords: Cognitive development, food preferences, implicit associations, health knowledge, eating behavior

Studying the development and predictors of children’s food-related behavior and reasoning has recently emerged as a critical area of research. What children do and do not eat has direct health relevance, as children in the United States are not consuming recommended amounts of fruits and vegetables (Banfield et al., 2016; Kim et al., 2014) and childhood obesity is a critical health concern (Cunningham et al., 2014; Levi et al., 2015). Evidence of children’s early health knowledge and positive attitudes toward healthy foods is mixed. Although children are capable of correctly classifying foods as “healthy” or “junky” by age 3 (Nguyen, 2007) and can learn more complex information about nutrition in the preschool and early school years (Gripshover & Markman, 2013; Nguyen et al., 2011; Sigman-Grant et al., 2014), they nonetheless often reject healthy foods (Maimaran & Fishbach, 2014; Wardle & Huon, 2000). At the same time, children seem to have some understanding that unhealthy foods should be avoided: When given the choice between two foods, one described as “healthy” and one described as “unhealthy,” 5- and 6-year-old children tended to eat more of the “healthy” food (DeJesus, Du, et al., 2019). This pattern could suggest a preference for healthy foods, an avoidance of unhealthy foods, or both. However, children did not differentiate between a food described as “healthy” and a food described neutrally as “right here” (without health-related attributes), again suggesting a potential gap between children’s emerging knowledge of food healthfulness and the likelihood that children will actually eat healthy foods.

In addition to knowledge of the health or taxonomic properties of food (i.e., factual components that could be correct or incorrect and that increase with age), we define food cognition as also encompassing more subjective preferences, beliefs, and attitudes towards food, which might also be important to understand and intervene on to promote healthy food choices across the lifespan. Researchers who study children’s eating behavior struggle with assessing children’s “true” attitudes, that is what children really think about foods or their willingness to eat those foods in typical contexts, rather than what children think their parents (or adult researchers) expect or prefer. Many studies of children’s eating behavior rely on parental reports, such as the Child Eating Behavior Questionnaire, a widely used measure that asks parents to report on several aspects of their child’s eating behavior, including their pickiness and enjoyment of food (Wardle et al., 2001). Although studies comparing parental report to children’s observed eating behaviors tend to find convergence in these measures (e.g., Fernandez et al., 2018), the correlation is at times only moderate (Pliner, 1994). These measures often ask parents to answer general questions about their children’s eating habits, such as “my child refuses new foods at first” or “my child enjoys tasting new foods,” but do not tap into children’s perceptions of food healthfulness or of a specific food’s palatability. Consequently, comparisons between healthfulness and palatability as influences on children’s food choices are not provided by these measures.

Studies with child participants (rather than parents reporting on their child’s behalf) have assessed children’s food healthfulness knowledge by asking children to sort foods as “healthy” versus “unhealthy or “junky,” by asking children to explain why they think a particular food is healthy (and analyzing the content of children’s explanations), and by describing foods using different health messages and measuring children’s food choices and intake (DeJesus, Du, et al., 2019; Gripshover & Markman, 2013; Maimaran & Fishbach, 2014; Nguyen, 2007; Nguyen et al., 2011; Sigman-Grant et al., 2014). Many of these studies are conducted in school settings, so their parents are not present. Nonetheless, in these settings children are still under the authority of adults (e.g., their teachers) and being asked questions by adult researchers. Some studies attempt to reduce social pressure in their design, such directing the experimenter to not directly face children while children are eating, having adults who provide messages about foods leave the room while children are eating, or having other children provide messages about foods (DeJesus, Du, et al., 2019), yet the extent to which these efforts actually reduce social pressure to make food choices that would be socially desirable to adults is unclear.

One potential method to study children’s food cognition while reducing social pressure from adults is the Implicit Association Test (IAT), a widely used tool to measure social attitudes. This measure capitalizes on differences in reaction time to categorize stimuli (rather than asking participants directly about their attitudes) and is therefore thought to be less susceptible to conscious control or social desirability concerns compared to self-report measures. Previous studies using the IAT have typically focused on attitudes towards people. Of particular relevance to food cognition, nutrition, and public health, IATs have examined negative associations that people hold toward heavier body shapes (Charlesworth & Banaji, 2019; Schwartz et al., 2006), including negative associations observed among students and health professionals who specialize in obesity (Chambliss et al., 2004; Schwartz et al., 2003) and biases that predict discriminatory practices on the part of hiring managers (Agerström & Rooth, 2011).

A few recent studies have used a similar design to examine adults’ attitudes towards foods. One study asked adults to categorize pictures of fruits and chocolate snacks, as well as positive and negative stimuli (such as a picture of an angry dog and the word “joy”). When participants’ cognitive resources were taxed by asking participants to remember an 8-digit number during the study, participants’ scores on the implicit measure predicted the number of chocolates participants chose, whereas their explicit preferences predicted food choices when participants were only asked to remember a 1-digit number (Friese et al., 2008; Hofmann et al., 2007, for related findings, see 2009). In another study, an interaction between implicit preferences for snack foods and inhibitory control was observed: Among participants with a high implicit preference for snack foods (+1 SD), low inhibitory control was positively associated with weight gain over one year (Nederkoorn et al., 2010). Researchers have suggested that these implicit measures would be useful in food studies to reduce the influence of demand characteristics (similar to studies of social attitudes) and tap into more automatic, impulsive aspects of food cognition (Nederkoorn et al., 2010). Yet to date, this method has not been extended to child populations and has not previously included vegetables, which would be useful for examining children’s food cognition given their frequent rejection of vegetables (e.g., Cooke & Wardle, 2005).

The current paper presents a measure of children’s food cognition using the methodology of the IAT. Prior research extending the IAT to children has examined implicit ingroup preferences (Baron & Banaji, 2006; Dunham et al., 2006, 2007; Newheiser & Olson, 2012), gender attitudes (Dunham, Baron, & Banaji, 2016; Meyer & Gelman, 2016), and early stereotypes (such as gender stereotypes about math ability) that could influence children’s perceptions of their own skills and abilities (Cvencek et al., 2016). One important strength of this method, particularly for studies of eating behavior across the lifespan, is that the same task can be used to study a wide age range, from preschool through adulthood (see Baron & Banaji, 2006). However, few studies have used the IAT to examine children’s thinking about topics outside of social stereotypes.

The present study employs a food version of the IAT. In this task, children were asked to categorize pictures of foods as either vegetables and desserts and pictures of faces as either happy or sad by pressing buttons on a computer keyboard. The critical trials asked participants to either: (1) categorize vegetables and happy faces using one button and desserts and sad faces using another button, or (2) categorize vegetables and sad faces using one button and desserts and happy faces using another button. Four- to 12-year-old children were tested at a children’s museum. Participants completed the food IAT, as well as an explicit card sort task that asked children to assess foods based on their perception of the food’s healthfulness (healthy vs. unhealthy) and palatability (yummy vs. yucky). Children’s parents provided information about their children’s dietary intake in the previous 3 months. In a pilot study in the supplemental materials, 4- to 12-year-old children and their parents participated in a study in a laboratory setting, in which children and their parents both completed the food IAT and a snack choice task.

We hypothesized that children’s food IAT responses would mirror patterns of implicit and explicit associations in studies of social groups and stereotypes: Participants across ages were predicted to demonstrate stronger implicit “dessert-happy” than “vegetable-happy” associations across ages. In line with findings that children find highly palatable foods to be salient and are vigilant towards those foods (Gearhardt et al., 2012; Werthmann et al., 2015), we expected that the food IAT would reveal a more affective, emotion-laden view of food (i.e., greater speed at categorizing highly palatable foods and happy faces using the same button). In contrast, we expected the card sort task to be more indicative of children’s health knowledge or expectation that adults prefer them to eat healthy foods (which may increase with age). In contrast, it is possible that the food IAT could mirror patterns of food acceptance and rejection: Rejection of vegetables is most common among younger children (Cooke & Wardle, 2005). Therefore, a possible alternative is that children’s implicit and explicit associations may be aligned: Children who dislike vegetables (which may be especially characteristic of younger children’s preferences) may demonstrate a stronger “vegetable-unhappy” association compared to children who are willing to report that they like vegetables. A third possibility is that children’s performance on the food IAT could reflect messages that they receive about food (e.g., that healthy eating is important), rather than their perceived palatability of the food. If so, children might demonstrate implicit positivity toward vegetables in the IAT, even if their explicit taste assessments reflect more positive perceived palatability of desserts than vegetables.

Method

Children across a wide range of ages (4 to 12 years) were tested in a food version of the IAT in a children’s museum. In addition to the food IAT, to evaluate children’s explicit assessments of foods, children completed a card sort task in which they assessed vegetables, desserts, and fruits based on each food’s healthfulness and perceived palatability. Parents completed a dietary intake questionnaire reporting the frequency with which children ate each of the foods in this study in the last 3 months.

Participants

Participants included 123 4- to 12-year-old children (29 4- and 5-year-olds, 13 girls, 16 boys; 34 6- and 7-year-olds, 17 girls, 16 boys, 1 did not report; 31 8- and 9-year-olds, 16 girls, 15 boys; and 29 10- to 12-year-olds, 15 girls, 14 boys; mean age = 7.98 years, range = 4.02 – 12.92 years) recruited at a children’s museum in Southeastern Michigan. We selected this age range based on previous findings that children are capable of categorizing foods accurately based on healthfulness at age 4 (Nguyen, 2007). This also allowed us to examine whether children’s food cognition mirrors IAT findings in the area of social cognition, in which children’s implicit associations are consistent across ages whereas their explicit associations differ across ages (Baron & Banaji, 2006). In addition, although children’s earliest food choices are primarily driven by taste, children’s later food choices are also influenced by other factors, including knowledge of food healthfulness and social desirability among their peers (Birch, 1979, 1980; DeJesus, Du, et al., 2019; DeJesus et al., 2018).

Race and ethnicity (reported by parents) were as follows: 63 participants were White, 15 were Asian/Asian American, 14 reported more than one race/ethnicity, 10 were Hispanic/Latino, 4 were Black/African American, 1 was American Indian/Alaska Native, and 16 did not report. Detailed information about family income was not collected. The museum admission price ranged from $5-$12.50 (with a discount offered for low income families) and family memberships ranged from $80-$150 per year. Children received a small prize for participating in the study. A target sample of 32 children per age group was planned based on prior studies using the IAT with children (e.g., Meyer & Gelman, 2016; Newheiser & Olson, 2012). In addition, based on the goal of predicting children’s IAT d-scores, a power analysis for a linear multiple regression with 3–5 predictors and a small-to-moderate effect size (0.15) in GPower returned a recommended sample size of 89 (Faul et al., 2009).

Materials

The stimuli for this study included images of foods and children’s faces. All participants viewed the same images. Images of foods were obtained from Google Images searches and the Food-pics database (Blechert et al., 2014). Specific foods were selected based on expected familiarity; we aimed to select highly familiar foods because items in the IAT are not explicitly labeled and are typically highly familiar, such as happy or sad words, or can be categorized based on their perceptual features, such as Black or White faces (Baron & Banaji, 2006). The food IAT included pictures of vegetables (carrots, cauliflower, corn, lettuce) and desserts (cookie, doughnut, ice cream, lollipops). The card sort task included the same pictures of vegetables and desserts, individually printed in color on 2.5 × 3-inch cards and laminated (see Figure 1). The card sort task also included pictures of fruit (see supplemental materials for materials and data from fruit trials).

Figure 1.

Images of foods used in the card sort task and food IAT.

Images of children’s faces were used in the food IAT and were selected from the Child Affective Facial Expression (CAFE) set (LoBue & Thrasher, 2015). Images were selected to be reliably rated as happy or sad and included two Black girls, two White girls, two Black boys, and two White boys (see supplemental materials for the filenames of the specific images selected). Only adult ratings were available when this study was designed, but faces from the CAFE set have since been validated with preschool-aged children, with a robust positive association between children’s and adults’ ratings (LoBue et al., 2018). Two face sets were created such that, if a child was depicted with a happy face in Set A, that child was depicted with a sad face in Set B (face set counterbalanced across participants).

Procedures and scoring

Food IAT

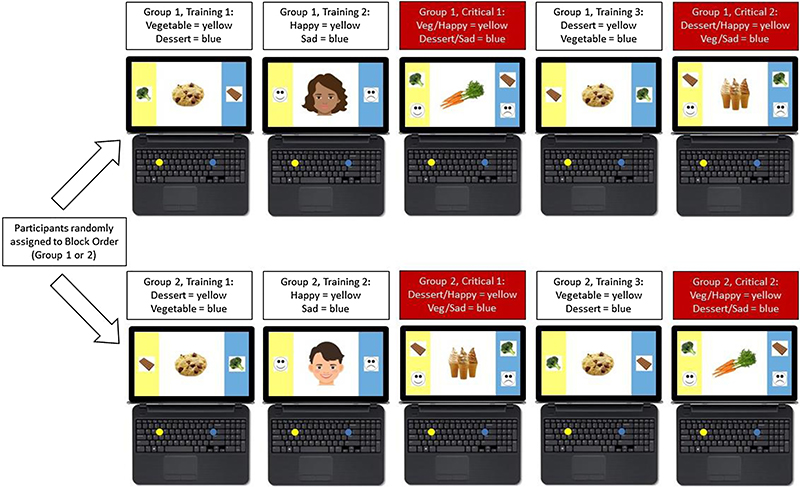

Children completed the food IAT on a laptop computer using Millisecond Inquisit 5 Lab software. The software script was adapted from the Child IAT script developed by Baron and Banaji (2006), available at http://www.millisecond.com/download/library/childiat/. The script was adapted to reduce the number of presented trials and replace positive and negative words with images of faces, given the age of our youngest participants and the busy museum setting (Cvencek et al., 2016). The computerized task included five blocks. In between each block, children selected a star sticker to preserve their attention for the entire study (Meyer & Gelman, 2016). See Figure 2 for a visual depiction of the study design. A demonstration video of the food IAT and researcher scripts for each task is available on the Open Science Framework (OSF): https://osf.io/r6bqn/?view_only=793ab491f08c46bdb7ffe236d8f91dba.

Figure 2.

Food IAT study design and example trials from each block and order group. Children categorized pictures of foods (as vegetables or desserts) and faces (as happy or sad) on a laptop computer. Due to copyright restrictions, the photos of children used in the study have been replaced with cartoon faces in this figure for illustration purposes.

In the first block, children categorized foods as either vegetables or desserts using a yellow or blue button on the keyboard. A picture of broccoli as an example vegetable and chocolate as an example dessert were shown inside yellow and blue bars on either side of the screen as reminders, which remained on screen while images of vegetables (carrots, cauliflower, corn, lettuce) and desserts (cookie, doughnut, ice cream, lollipops) appeared in the middle of the screen in random order for 16 trials. For example, a child would press the yellow button when they saw a picture of a vegetable and the blue button when they saw a picture of a dessert (see Figure 2, top, far left picture). In the second block, children categorized children’s faces displaying happy or sad expressions as either happy or sad using a yellow or blue button on the keyboard. Schematic line drawings of happy and sad faces were shown inside yellow and blue bars on either side of the screen as reminders, which remained on screen while color photo images of happy and sad faces appeared in the middle of the screen in random order for 16 trials. For example, a child would press the yellow button when they saw a picture of a happy face and the blue button when they saw a picture of a sad face (see Figure 2, top, left center picture).

In the third block, children categorized foods and faces, presented in random order for 40 trials, with a break after the first 16 trials (see Figure 2). In this first critical block, participants were assigned either to: (1) Categorize vegetables and happy faces using the same button (and desserts and sad faces using the other button) or (2) categorize desserts and happy faces using the same button (and vegetables and sad faces using the other button), consistent with the counterbalancing procedures of previous studies using the IAT. For example, a child would press the yellow button when they saw a picture of a vegetable or a happy face and the blue button when they saw a picture of a dessert or a sad face (see Figure 2, top, center picture). In the fourth block, the lateral position of the foods switched, such that children now needed to use the opposite buttons to categorize vegetables and desserts, presented in random order for 16 trials. For example, a child would press the yellow button if they saw a picture of a dessert and the blue button when they saw a picture of a vegetable (see Figure 2, top, right center picture). In the fifth block, children categorized foods and faces in the opposite pairing as block 3 (the first critical block), presented in random order for 40 trials, with a break after the first 16 trials. For example, a child would press the yellow button when they saw a picture of a dessert or a happy face and the blue button when they saw a picture of a vegetable or a sad face (see Figure 2, top, far right picture). Children completed a total of 128 trials and the task took on average 7.45 minutes to complete (95% CI = 6.95, 7.95).

To analyze the food IAT, d-scores were computed by Inquisit using the available script. As described in the original paper (Baron & Banaji, 2006), “scores were computed by calculating the difference between the mean response latencies for the two double-categorization blocks [i.e., critical trial blocks in which participants categorized foods and faces during the same block] for each child and dividing that difference by its associated pooled standard deviation.” Positive d-scores in the food IAT reflect a stronger vegetable-happy association (i.e., an overall faster reaction time when vegetables and happy faces were categorized using the same button) and negative scores reflect a stronger dessert-happy association (i.e., an overall faster reaction time when desserts and happy faces were categorized using the same button). For context, children’s and adults’ mean d-scores on a race IAT (in which positive scores represented a stronger association between White faces and happy words) were 0.22 in Baron and Banaji (2006).

Card sort task

Children were presented with cards depicting vegetables, desserts, and fruits (see supplemental materials for the fruit trials). Participants sorted the foods based on the food’s healthfulness (healthy vs. unhealthy) and perceived palatability (yummy vs. yucky; question order counterbalanced across participants). Specifically, children were asked “I want you to tell me which foods are healthy and which foods are unhealthy” and “This is [name of food]. Is it healthy or unhealthy?” to assess the food’s healthfulness and “I want you to tell me which foods are yummy and which foods are yucky” and “This is [name of food]. Is it yummy or yucky?” to assess the food’s perceived palatability.

To analyze the card sort task, we computed two indexes: Food healthfulness accuracy and perceived palatability. To create a food healthfulness accuracy index for each participant, we summed children’s categorizations of vegetables as healthy and desserts as unhealthy. Scores on this index could range from 0 (meaning that the child categorized all the vegetables as unhealthy and all the desserts as healthy) to 8 (meaning that the child categorized all the vegetables as healthy and all the desserts as unhealthy). Higher scores therefore represented greater accuracy of children’s food healthfulness assessment. Considering children’s palatability assessments, we were especially interested in the extent to which they were willing to explicitly report that a healthy food was “yummy.” To create a perceived palatability index for each participant, we summed children’s assessments of vegetables as yummy and desserts as yucky. Scores for fruits are in the supplemental materials. The perceived palatability index could range from 0 (meaning that the child assessed all the vegetables as yucky and all the desserts as yummy) to 8 (meaning that the child assessed all the vegetables as yummy and all the desserts as yucky). Higher perceived palatability scores reflected greater perceived palatability of healthier, compared to less healthy, foods.

Dietary intake questionnaire

In addition to a demographics questionnaire, parents were given a dietary intake questionnaire to report the frequency with which children ate each of the 8 foods in this study in the last 3 months. The response options were based on standard choices in the literature on food frequency: Never, less than 1 time per week, 1–3 times per week, 4–6 times per week, 1 time per day, 2–3 times per day, 4 or more times per day. We transformed these scores into a count per week (0, 1, 2, 5, 7, 14, 28 times per week) and from these counts created a vegetable-dessert ratio (vegetable sum per week divided by dessert sum per week). A score of 0 would mean that the child typically did not eat any of the 4 vegetables in a week (n = 6). A score above 0 but less than 1 would mean that the child typically ate more of the 4 desserts than the 4 vegetables per week (n = 27). A score of 1 would mean that the child typically ate equal numbers of the 4 vegetables and the 4 desserts per week (n = 7). A score above 1 would mean that the child typically ate more of the 4 vegetables than the 4 desserts per week (n = 48). The maximum possible score was 122, which would mean that the child ate each of the 4 vegetables at least 28 times per week (the maximum response) and never ate the desserts. Scores in our sample ranged from 0 to 35; higher scores indicate greater intake of vegetables relative to desserts.

On average, children in this sample were reported to eat the vegetables more often per week than the desserts (median vegetable-to-dessert ratio = 1.20, 95% CI = 1.27, 3.04); 48 children ate more vegetables than desserts per week (including 2 who ate no desserts), 33 ate more desserts than vegetables per week (including 6 who ate no vegetables), and 7 ate equal numbers of vegetables and desserts per week. For the two children whose parents reported that they ate none of the desserts, to avoid dividing by zero, we summed the vegetables per week the parent reported their child ate as the vegetable-dessert ratio for those children (note that this would be the same score as a child who ate the same number of vegetables per week and also ate one dessert per week, so may be a slight underestimation of these two children’s scores). In the busy museum setting, not all parents completed this questionnaire; therefore, we could not compute the vegetable-dessert ratio for 35 children.

Design and analyses

In addition to the counterbalancing described thus far, children participated in either the food IAT or the card sort task first. In general, parents were at or nearby the testing table at the museum. The card sort task was administered verbally, so parents could potentially their child’s responses. No instances of overt parental influence (i.e., a parent correcting the child or commenting positively or negatively about the child’s responses during the study) were observed; therefore, no trials were excluded on this basis. Nonetheless, children could be aware of their parents’ presence and have felt social pressure to respond in a particular way (such as rating vegetables as “yummy”) or could have noticed more subtle cues from their parents that were not obvious or visible to the experimenters during the study (such as smiling or nodding towards particular responses). For the food IAT, it is less clear what potential influence parents could have, as the overt goal of task was to correctly categorize images of foods and faces (and children were generally successful at achieving this goal), and it would be very difficult for parents (or any observer) to notice more subtle reaction time patterns.

Data and supplemental materials

Data were analyzed in R (R Core Team, 2016). Supplemental materials are available on OSF: https://osf.io/r6bqn/?view_only=793ab491f08c46bdb7ffe236d8f91dba. These supplemental materials include: (1) Filenames of the images selected from the CAFE set; (2) children’s performance in the fruit trials of the card sort task; (3) a supplemental analysis that analyzes individual trials of the food IAT to examine potential associations between children’s food categorizations and dietary intake frequency for individual foods; (4) children’s performance in a pilot study (n = 55) in which children and their parents both completed the food IAT, designed to test for possible associations between children’s and parents’ IAT d-scores and between participants’ IAT d-scores and their food choices in a snack choice task; (5) analysis code in R and deidentified data; and (6) supplemental references.

Results

Food IAT (implicit associations)

Children’s categorization accuracy in the food IAT was high, meaning that they generally categorized each target picture (either a food or a face) using the correct button: M = 91.52% correct, 95% CI = 90.33, 92.71, range: 70.73%−100%. No participants had 10% of trials under 300 ms; across 30 participants, 56 trials of 10,000 ms or more were observed.

To examine the directionality of children’s food IAT d-scores, a one-sample t-test was performed comparing children’s food IAT d-scores to 0. Overall, children demonstrated a stronger “vegetable-happy” association, meaning that children were faster to categorize foods and faces when they used the same button to categorize vegetables and happy faces (M = 0.14, 95% CI = 0.06, 0.22), t(122) = 3.54, p < .001, r = .31, see Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Boxplots of children’s food IAT d-scores. Positive scores reflect a stronger “vegetable-happy” association and negative scores reflect a stronger “dessert-happy” association. Left: “vegetable-happy” block first; center: “dessert-happy” block first; right: block order collapsed.

To further examine children’s food IAT d-scores, a linear regression with task order (food IAT or card sort first), block order (“vegetable-happy” or “dessert-happy” first), child age, child gender, and an Age x Gender interaction as predictors of food IAT d-scores was performed. Regarding block order, evidence for an effect of block order on the IAT is mixed in prior work. In some IAT studies with children, no effect of block order is observed (Baron & Banaji, 2006) and many studies do not test for an effect of block order (Cvencek et al., 2016; Dunham et al., 2006, 2007; Newheiser & Olson, 2012; Rutland, Cameron, Milne, & McGeorge, 2005). Some studies present the IAT materials in the same order for all participants (Friese et al., 2008). Other studies report block order to be a known influence on IAT performance, and specifically an attenuation of the condition difference in the stereotype inconsistent-first order has been observed (Meyer & Gelman, 2016; Nosek, Greenwald, & Banaji, 2005). The FAQ section of the Project Implicit website acknowledges the block order effect but notes that “the difference is small” (Project Implicit, 2011). In this present data, this model revealed a significant effect of block order: Children who received the “vegetable-happy” block first (M = 0.35, 95% CI = 0.25, 0.44) had higher food IAT d-scores than children who received the “dessert-happy” block first (M = −0.07, 95% CI = −0.17, 0.03), b = −0.41, SE = 0.07, t = −5.85, p < .001. No significant effects of task order (b = −0.07, SE = 0.07, t = −0.93, p = .355), age (b = −0.01, SE = 0.02, t = −0.49, p = .623), gender (b = 0.08, SE = 0.26, t = 0.30, p = .763), or Age x Gender interaction (b < 0.01, SE = 0.03, t = 0.08, p = .938) were observed.

Card sort (explicit assessments)

Food healthfulness accuracy

See Table 1 for children’s food healthfulness accuracy by item. Overall, children’s food healthfulness accuracy scores were high (chance = .50; M = .95, 95% CI = .93, .98), t(122) = 33.12, p < .001, r = .95, and even the youngest age group of participants in our sample (4- to 5-year-olds) performed above chance (M = .87, 95% CI = .77, .98), t(28) = 7.27, p < .001, r = .81. Differences in food healthfulness accuracy scores were observed depending on the category of the food, χ2 (1) = 32.98, p < .001. Children were more likely to be inaccurate for dessert trials (assessing 34 out of 456, or 7.46%, as “healthy”) than for vegetable trials (all vegetables were assessed as “healthy”).

Table 1.

The proportion of children’s explicit assessments of each food as healthy (vs. unhealthy) or yummy (vs. yucky). Dietary intake of each food is reported as the median number of times per week parents reported their child ate that food in the last 3 months.

| Food | Food healthfulness accuracy (“healthy”) Mean (95% CI) | Perceived palatability (“yummy”) Mean (95% CI) | Dietary iutake (times per week) Median (95% Cl) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vegetable | |||

| Carrot | .97 (.94, 1.00) | .77 (.69, .85) | 2 (2.18, 3.15) |

| Cauliflower | .97 (.94, 1.00) | .46 (.37, .54) | 1 (0.86, 1.40) |

| Corn | .98 (.96, 1.00) | .88 (.83, .94) | 2 (1.39, 1.92) |

| Lettuce | .98 (.96, 1.00) | .67 (.59, .76) | 1 (1.59.2, 74) |

| Dessert | |||

| Cookies | .10 (.04, .15) | .90 (.85, .96) | 1 (1.57, 3.04) |

| Doughnut | .07 (.03, .12) | .85 (.78, .91) | 1 (0.83, 1.19) |

| Ice cream | .05 (.01, .09) | .90 (.85, .96) | 1 (1.47, 2.79) |

| Lollipop | .06 (.02, .10) | .76 (.68, .83) | 1 (0.72, 1.13) |

To test for task order, age, or gender effects on children’s food healthfulness accuracy scores, we performed a linear regression with task order, child age, gender, and an Age x Gender interaction as predictors of children’s food healthfulness accuracy scores. Age and gender both predicted children’s food healthfulness accuracy scores. Children’s food healthfulness accuracy scores were positively associated with age, b = 0.25, SE = 0.07, t = 3.80, p < .001. Boys (M = .98, 95% CI = .95, 1.00) were more accurate than girls (M = .93, 95% CI = .88, .98; b = 1.68, SE = 0.78), t = 2.16, p = .033. No significant effect of task order (b = 0.25, SE = 0.22, t = 1.03, p = .304) or Age x Gender interaction were observed (b = −0.17, SE = 0.09, t = −1.80, p = .074).

Perceived palatability

See Table 1 for children’s assessment of each food’s perceived palatability. Children tended to assess the perceived palatability of both vegetables (M = .69, 95% CI = .64, .74, t(122) = 7.72, p < .001, r = .57) and desserts (M = .85, 95% CI = .80, .90, t(122) = 14.82, p < .001, r = .80) as yummy. Children were more likely to assess desserts as yummy compared to vegetables (t(122), 4.17, p < .001, r = .35. To test for task order, age, or gender effects on children’s assessment of perceived palatability, we performed a linear regression with task order, child age, gender, and an Age x Gender interaction as predictors of children’s perceived palatability index (maximum = 8; higher perceived palatability scores reflected greater perceived palatability of healthier, compared to less healthy, foods). No significant predictors were observed: Task order, b = 0.47, SE = 0.31, t = 1.49, p = .139; age, b = 0.19, SE = 0.10, t = 1.92, p = .057; gender, b = 0.26, SE = 1.13, t = 0.23, p = .819; Age x Gender interaction, b = −0.07, SE = 0.14, t = −0.53, p = .601).

Associations between explicit and implicit assessments

To test for associations between explicit and implicit assessments, we performed a repeated-measures linear regression on children’s food IAT d-scores, with block order, food healthfulness accuracy scores, perceived palatability scores, and parent-reported child dietary intake entered simultaneously as predictors. This analysis revealed a significant effect of block order (b = −0.36, SE = 0.08, t = −4.33, p < .001) and food healthfulness accuracy score, (b = 0.10, SE = 0.04, t = 2.66, p = .009). Perceived palatability score (b = 0.03, SE = 0.03, t = 1.02, p = .312) and parent-reported child dietary intake (b < 0.01, SE < 0.01, t = 0.74, p = .459) did not predict food IAT d-scores. Breaking down children’s responses by block order, children who received the vegetable-happy block first, had significantly positive d-scores (M = 0.35, 95% CI = 0.25, 0.44), t(60) = 7.35, p < .001, r = .69. Children who received the dessert-happy block first did not differ from 0 in their food IAT d-scores (M = −0.07, 95% CI = −0.17, 0.03), t(61) = −1.32, p = .192, r = .17.

Summary of findings in supplemental materials

Two additional analyses are presented in detail in the supplemental materials. First, we report an analysis of individual trials in the food IAT. The individual trial analysis revealed that, at the level of specific foods, children’s food healthfulness assessments and their dietary intake of that food (as reported by their parents) were both associated with their reaction times on individual trials. The IAT is not typically analyzed in this way so we do not discuss these findings further, except to note that they align with the aggregate finding that children’s assessments of food healthfulness were positively associated with their food IAT d-scores. Second, we present a pilot study (n = 55) that examines associations between parents’ and children’s food IAT d-scores, and between participants’ food IAT d-scores and their snack choices. We found no significant association between parent and child scores and no association between participants’ food IAT d-scores and their snack choices.

Discussion

The current study tests whether an implicit association test (IAT) design could be used to study the development of food cognition in children. This study reveals three findings. First, and surprisingly, children were overall faster to categorize stimuli (foods and faces) when they were asked to use one button to categorize vegetables and happy faces and a different button to categorize desserts and sad faces. This result was the opposite of our hypothesis that children would demonstrate faster responses when they were asked to use one button to categorize desserts and happy faces and a different button to categorize vegetables and sad faces. In contrast, we found a robust vegetable-happy association.

Second, children’s food healthfulness assessments were highly accurate, even among our youngest participants, and children’s perceived palatability demonstrated considerable positivity toward the vegetables in the study. Although participants were more likely to assess desserts as yummy compared to vegetables, their perceived palatability of vegetables ranged from 46% yummy (cauliflower) to 88% yummy (corn). Parents of children in this sample reported that their children also typically ate the vegetables depicted in this study more often per week than they ate the desserts. This result could reflect several tendencies, including increasing health knowledge in recent years among adults (Guthrie et al., 1999; Rehm et al., 2016) which may be directly or indirectly transmitted to children, children’s understanding that unhealthy foods should be avoided (DeJesus, Du, et al., 2019), and general positivity biases (observed in the domain of personality trait attribution) in early childhood (Boseovski, 2010). These findings suggest that children may receive positive messages about vegetables in their food environment or be rewarded for eating vegetables, which may be reflected in their food IAT d-scores. This finding could also reflect biases in terms of the sample recruited (i.e., families visiting a children’s museum in a Midwestern university town) or parents’ reporting of their children’s typical food intake to researchers at the museum (i.e., an overestimate of children’s true vegetable intake). Additionally, the positivity toward vegetables here may also have reflected the inclusion of relatively sweet vegetables (e.g., corn, carrots) rather than more bitter vegetables (e.g., spinach, Brussels sprouts), therefore we do not necessarily interpret these findings as suggesting that children broadly enjoy the taste of vegetables.

Third, we observed individual differences in children’s assessment of food healthfulness and dietary intake that were associated with their performance in the food IAT. In the aggregate, the accuracy of children’s assessments of food healthfulness was positively associated with their food IAT d-scores (the more accurate, the stronger the vegetable-happy association). We discuss these results in terms of their implications for food cognition and what they might reveal about the IAT.

Implications for food cognition

These findings suggest associations among children’s rapid food categorizations, their explicit assessments foods, and their food experiences. Rather than uncovering a more subjective or affective view of food categorization, in which children’s assessments of food palatability would predict their speed to categorize images of vegetables and desserts, this method revealed an influence of children’s assessments of food healthfulness and how often parents reported their children ate that food. These findings align with previous studies that children’s ability to categorize foods as fruits versus vegetables is related to their food pickiness (Rioux et al., 2016) and that increasing children’s visual exposure to a food (via a place mat with pictures of vegetables) increased children’s willingness to eat those foods (Rioux et al., 2018). Rioux et al. proposed a potential link between parent’s willingness to offer children a food (especially if their children are picky eaters) and children’s taxonomic categorization abilities (e.g., the ability to categorize foods as fruits vs. vegetables). Similarly, in the present study, parents who reported that their children ate a particular food more often may have been more willing to offer those foods to their children (see also Daniel, 2016).

These findings raise important questions regarding the causal relations between the many ways that children can assess or think about a particular food and their food choices. This study provides mixed evidence. On the one hand, in an exploratory analysis (see supplemental materials), we found that children’s food intake as reported by their parents was related to their reaction time to categorize that food as a vegetable or a dessert. Similarly, other studies have found links between patterns of eating behavior (such as food pickiness) and children’s taxonomic categorization abilities (e.g., Rioux et al., 2016). On the other hand, in the pilot study reported in the supplemental materials, participants’ food IAT d-scores did not predict their food choices. Other studies have shown that not all food cognition is equivalent. Notably, teaching children basic facts about foods (such as the effects of healthy eating and exercise) were less effective than interventions that provided causal mechanisms about nutrition (e.g., how digestion breaks down nutrients to promote health and taking in a diverse set of foods increases the types of nutrients available) in promoting children’s vegetable intake (Gripshover & Markman, 2013). At the same time, children’s assessment of a food as healthy vs. unhealthy or as belonging to a particular taxonomic category (e.g., fruits, vegetables, desserts) are not irrelevant to children’s food choices – a child must be able to identify a food’s category in order to achieve the goal of eating healthy foods or a diverse diet (when choosing foods for themselves).

Moreover, food cognition may interact with other potential influences on children’s eating behavior, including peer modeling and social messages about what peers are eating (Birch, 1980; DeJesus et al., 2018) and cultural beliefs about what should or should not be eaten (Bian & Markman, 2020; DeJesus, Gerdin, et al., 2019; Ruby et al., 2015). Food has important social relevance, and from an early age children appreciate its social and cultural significance (DeJesus et al., 2018; DeJesus, Gerdin, et al., 2019; Liberman et al., 2016). For instance, the foods American adults tend to perceive as especially well-suited to be breakfast foods (i.e., foods that adults endorse as right to eat for breakfast compared to foods adults endorse as wrong to eat for breakfast) also tend to be less nutritious than foods they conceptualize as lunch or dinner foods (Bian & Markman, 2020). In addition to several other factors, ranging from genetic differences in taste perception (Reed & Knaapila, 2010) to children’s experiences of food insecurity (Jansen et al., 2017), these factors represent a constellation of influence on children’s food choices and the relation between food choices and health outcomes, suggesting that food cognition may be a necessary but not a sufficient mechanism to promote healthy food choices and actual improvements in child health.

Implications for the IAT

Both the overall analyses and the exploratory individual trial analysis support the suggestion that children’s performance on the food IAT may be more reflective of children’s health knowledge or food environment, rather than their assessment of a food’s palatability. This raises the more general question of the implications of these findings for the interpretation of the IAT. A longstanding debate in the literature concerns whether the IAT reflects personally held implicit attitudes and bias versus knowledge of broader cultural beliefs or attitudes (e.g., Jost, 2019; Uhlmann et al., 2012). Although the present findings certainly cannot resolve this broader debate, they provide important new evidence. Note that the design of this task makes opposing directional predictions for effects of personal, subjective experience (in which desserts should more readily pair with a happy face) versus effects of cultural knowledge (in which vegetables should more readily pair with a happy face). That we found that even young children make greater use of the latter than the former is suggestive that the IAT may be less linked to personal attitudes than some may assume, but much more research is needed to explore this idea more thoroughly.

An additional finding (specific to the IAT design) was the robust effect of block order on children’s food IAT d-scores. Specifically, children’s food IAT d-scores differed as a function of which critical block they received first. These scores were positive (meaning that they were faster to categorize foods and faces when they used the same button to categorize vegetables and happy faces than when they used the same button to categorize desserts and happy faces) if they received the vegetable-happy critical block first, but were at chance if they received the dessert-happy critical block first. As mentioned previously, block order is rarely discussed or analyzed in studies using the IAT with children. In those few studies that do examine block order, results are inconsistent: Some studies have found no effect of block order (Baron & Banaji, 2006), other studies do find effects of block order (Meyer & Gelman, 2016), and some researchers have described this phenomenon as a known feature of the IAT (Nosek et al., 2005). Studies that have tested for and observed block order effects typically observed an attenuation of the condition difference when participants received the stereotype-inconsistent block first (Meyer & Gelman, 2016; Nosek et al., 2005). Although the food IAT does not neatly map on to the stereotype-consistent and stereotype-inconsistent framework (if anything, we expected “vegetable-happy” to map on to stereotype-inconsistent), the absence of an effect in one block order aligns with these previous studies. Altogether, then, we recommend consistently testing for an effect of block order in future IAT studies.

Open questions and limitations

Several open questions remain from this study, which future research is needed to fully understand. First, we do not have detailed information about the socioeconomic status of the families who participated in the museum study. Families who participated in the lab pilot study in the same location tended to be high income (the modal reported gross family income range in this study was $100,000 to $149,000 and the second highest response was $150,000 or more; see supplemental materials). Examining this phenomenon among low-income families (who would be more likely to have experienced food insecurity or have less access to fruits and vegetables) would be useful to further assess the relation between children’s food cognition, their health knowledge, and their dietary intake. Second, this study did not include a measurement of child body mass index (BMI). Though we have no specific reason to believe that children’s basic knowledge of food healthfulness or attitudes towards well-known foods would differ based on weight status, this would be important to measure in future studies, especially in light of evidence that visual attention biases for food images are related to weight gain and obesity (Castellanos et al., 2009; Hendrikse et al., 2015; Yokum et al., 2015). Third, we did not have a measurement of children’s history of picky eating, such as the Food Fussiness subscale of the Child Eating Behavior Questionnaire (Wardle et al., 2001). Food pickiness may be an important influence not only on children’s perceptions of taste but also on other aspects of their food cognition, given that in prior research, children who rejected more foods were also less accurate at appropriately categorizing fruits and vegetables (Rioux et al., 2016). Children’s vegetable intake could be considered a proxy for picky eating, but a more direct measure of picky eating would be useful to include in future studies.

A key open question that this study does not address directly is what might be the potential limits of health messages in guiding children’s food attitudes and choices. Children’s performance in these studies might be most reflective of their food environments, rather than their perceptions of the palatability of specific foods. It would be critical for future research to more thoroughly characterize children’s food environments, both in terms of the availability of healthy foods and the types of messages children regularly receive about health at home and at school, and then to test the extent to which these environments are related to children’s actual food choices. One possible interpretation of the present findings is that children (at least in this sample) have received the message that healthy eating is important, but receiving that message does not necessarily mean that children will actually select healthy foods (in the pilot study, no association between children’s food IAT d-scores and their actual snack choices was observed). Many interventions to promote healthy eating and prevent obesity have been implemented that focus on delivering verbal lessons to children in preschool classrooms but have observed modest beneficial effects (Colquitt et al., 2016; Gripshover & Markman, 2013; Sigman-Grant et al., 2014; Wolfenden et al., 2012). These findings suggest that additional strategies, beyond nutrition education or promoting healthy food choices, are necessary to prevent obesity and other health concerns, which occur in the broader context of children’s exposure to psychosocial stress, genetic risk factors, and broader social policy (Doom et al., 2019; Knutson et al., 2007; Lott et al., 2018; Lumeng et al., 2014; Pesch & Lumeng, 2018).

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Describes the development of a food IAT with 4- to 12-year-old children.

Children categorized images of foods (vegetables, desserts) and faces (happy, sad).

Children also explicitly assessed each food’s healthfulness and palatability.

Children demonstrated positive implicit associations towards vegetables.

Health accuracy in the explicit task positively predicted their food IAT d-scores.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by an NIH T32 Postdoctoral Research Fellowship (T32HD079350) and an AHA Postdoctoral Research Fellowship (17POST33400006) to JMD. We thank Joy Boakye, Grace Chen, Alicia DeMartini, Evan Hammon, Isabella Herold, Payge Lindow, Xiang Meng, Andrea Nagorski, and Megan Remer for assistance in recruitment and data collection. We also thank the Living Lab at the Ann Arbor Hands-On Museum and University of Michigan Museum of Natural History for their support.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Agerström J, & Rooth D-O (2011). The role of automatic obesity stereotypes in real hiring discrimination. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(4), 790–805. 10.1037/a0021594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banfield EC, Liu Y, Davis JS, Chang S, & Frazier-Wood AC (2016). Poor adherence to U.S. dietary guidelines for children and adolescents in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey population. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 116(1), 21–27. 10.1016/j.jand.2015.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron AS, & Banaji MR (2006). The development of implicit attitudes. Evidence of race evaluations from ages 6 and 10 and adulthood. Psychological Science, 17(1), 53–58. 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2005.01664.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bian L, & Markman EM (2020). Why do we eat cereal but not lamb chops at breakfast? Investigating Americans’ beliefs about breakfast foods. Appetite, 144, 104458 10.1016/j.appet.2019.104458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birch LL (1979). Preschool children’s food preferences and consumption patterns. Journal of Nutrition Education, 11(4), 189–192. 10.1016/S0022-3182(79)80025-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Birch LL (1980). Effects of peer models’ food choices and eating behaviors on preschoolers’ food preferences. Child Development, 51(2), 489–496. 10.2307/1129283 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blechert J, Meule A, Busch NA, & Ohla K (2014). Food-pics: An image database for experimental research on eating and appetite. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 617 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boseovski JJ (2010). Evidence for “rose-colored glasses”: An examination of the positivity bias in young children’s personality judgments. Child Development Perspectives, 4(3), 212–218. 10.1111/j.1750-8606.2010.00149..x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Castellanos EH, Charboneau E, Dietrich MS, Park S, Bradley BP, Mogg K, & Cowan RL (2009). Obese adults have visual attention bias for food cue images: Evidence for altered reward system function. International Journal of Obesity, 33(9), 1063–1073. 10.1038/ijo.2009.138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambliss HO, Finley CE, & Blair SN (2004). Attitudes toward obese individuals among exercise science students. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 36(3), 468–474. 10.1249/01.MSS.0000117115.94062.E4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlesworth TES, & Banaji MR (2019). Patterns of implicit and explicit attitudes: I. Long-term change and stability from 2007 to 2016. Psychological Science, 30(2), 174–192. 10.1177/0956797618813087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke LJ, & Wardle J (2005). Age and gender differences in children’s food preferences. British Journal of Nutrition, 93(5), 741–746. 10.1079/BJN20051389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham SA, Kramer MR, & Narayan KV (2014). Incidence of childhood obesity in the United States. New England Journal of Medicine, 370(5), 403–411. 10.1056/NEJMoa1309753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cvencek D, Greenwald AG, & Meltzoff AN (2016). Implicit measures for preschool children confirm self-esteem’s role in maintaining a balanced identity. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 62, 50–57. 10.1016/j.jesp.2015.09.015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel C (2016). Economic constraints on taste formation and the true cost of healthy eating. Social Science & Medicine, 148, 34–41. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.11.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeJesus JM, Du KM, Shutts K, & Kinzler KD (2019). How information about what is “healthy” versus “unhealthy” impacts children’s consumption of otherwise identical foods. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 148(12), 2091–2103. 10.1037/xge0000588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeJesus JM, Gerdin E, Sullivan KR, & Kinzler KD (2019). Children judge others based on their food choices. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 179, 143–161. 10.1016/j.jecp.2018.10.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeJesus JM, Shutts K, & Kinzler KD (2018). Mere social knowledge impacts children’s consumption and categorization of foods. Developmental Science, 21(5), e12627 10.1111/desc.12627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doom JR, Lumeng JC, Sturza J, Kaciroti N, Vazquez DM, & Miller AL (2019). Longitudinal associations between overweight/obesity and stress biology in low-income children. International Journal of Obesity, 1–10. 10.1038/s41366-019-0447-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunham Y, Baron AS, & Banaji MR (2006). From American city to Japanese village: A cross-cultural investigation of implicit race attitudes. Child Development, 77(5), 1268–1281. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00933.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunham Y, Baron AS, & Banaji MR (2007). Children and social groups: A developmental analysis of implicit consistency in Hispanic Americans. Self and Identity, 6(2–3), 238–255. 10.1080/15298860601115344 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dunham Y, Baron AS, & Banaji MR (2016). The development of implicit gender attitudes. Developmental Science, 19(5), 781–789. 10.1111/desc.12321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faul F, Erdfelder E, Buchner A, & Lang A-G (2009). Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods, 41(4), 1149–1160. 10.3758/brm.41.4.1149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez C, DeJesus JM, Miller AL, Appugliese DP, Rosenblum KL, Lumeng JC, & Pesch MH (2018). Selective eating behaviors in children: An observational validation of parental report measures. Appetite, 127, 163–170. 10.1016/j.appet.2018.04.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friese M, Hofmann W, & Wänke M (2008). When impulses take over: Moderated predictive validity of explicit and implicit attitude measures in predicting food choice and consumption behaviour. British Journal of Social Psychology, 47(3), 397–419. 10.1348/014466607X241540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gearhardt AN, Treat TA, Hollingworth A, & Corbin WR (2012). The relationship between eating-related individual differences and visual attention to foods high in added fat and sugar. Eating Behaviors, 13(4), 371–374. 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2012.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gripshover SJ, & Markman EM (2013). Teaching young children a theory of nutrition conceptual change and the potential for increased vegetable consumption. Psychological Science, 24(8), 1541–1553. 10.1177/0956797612474827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guthrie JF, Derby BM, & Levy AS (1999). What people know and do not know about nutrition. America’s Eating Habits: Changes and Consequences, 243–290. [Google Scholar]

- Hendrikse JJ, Cachia RL, Kothe EJ, McPhie S, Skouteris H, & Hayden MJ (2015). Attentional biases for food cues in overweight and individuals with obesity: A systematic review of the literature. Obesity Reviews, 16(5), 424–432. 10.1111/obr.12265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann W, Friese M, & Roefs A (2009). Three ways to resist temptation: The independent contributions of executive attention, inhibitory control, and affect regulation to the impulse control of eating behavior. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 45(2), 431–435. 10.1016/j.jesp.2008.09.013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann W, Rauch W, & Gawronski B (2007). And deplete us not into temptation: Automatic attitudes, dietary restraint, and self-regulatory resources as determinants of eating behavior. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 43(3), 497–504. 10.1016/j.jesp.2006.05.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen EC, Kasper N, Lumeng JC, Herb HEB, Horodynski MA, Miller AL, Contreras D, & Peterson KE (2017). Changes in household food insecurity are related to changes in BMI and diet quality among Michigan Head Start preschoolers in a sex-specific manner. Social Science & Medicine, 181, 168–176. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.04.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jost JT (2019). The IAT is dead, long live the IAT: Context-sensitive measures of implicit attitudes are indispensable to social and political psychology. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 28(1), 10–19. 10.1177/0963721418797309 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SA, Moore LV, Galuska D, Wright AP, Harris D, Grummer-Strawn LM, Merlo CL, Nihiser AJ, & Rhodes DG (2014). Vital signs: Fruit and vegetable intake among children—United States, 2003–2010. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 63(31), 671–676. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knutson KL, Spiegel K, Penev P, & Van Cauter E (2007). The metabolic consequences of sleep deprivation. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 11(3), 163–178. 10.1016/j.smrv.2007.01.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levi J, Segal LM, Rayburn J, & Martin A (2015). State of Obesity: Better Policies for a Healthier America: 2015. Trust for America’s Health. http://stateofobesity.org/files/stateofobesity2015.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Liberman Z, Woodward AL, Sullivan KR, & Kinzler KD (2016). Early emerging system for reasoning about the social nature of food. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 10.1073/pnas.1605456113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LoBue V, Baker L, & Thrasher C (2018). Through the eyes of a child: Preschoolers’ identification of emotional expressions from the child affective facial expression (CAFE) set. Cognition and Emotion, 32(5), 1122–1130. 10.1080/02699931.2017.1365046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LoBue V, & Thrasher C (2015). The Child Affective Facial Expression (CAFE) set: Validity and reliability from untrained adults. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 1532 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lott M, Schwartz M, Story M, & Brownell KD (2018). Why we need local, state, and national policy-based approaches to improve children’s nutrition in the United States In Freemark MS (Ed.), Pediatric Obesity: Etiology, Pathogenesis and Treatment (pp. 731–755). Springer International Publishing; 10.1007/978-3-319-68192-4_42 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lumeng JC, Miller A, Peterson KE, Kaciroti N, Sturza J, Rosenblum K, & Vazquez DM (2014). Diurnal cortisol pattern, eating behaviors and overweight in low-income preschool-aged children. Appetite, 73, 65–72. 10.1016/j.appet.2013.10.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maimaran M, & Fishbach A (2014). If it’s useful and you know it, do you eat? Preschoolers refrain from instrumental food. Journal of Consumer Research, 41(3), 642–655. 10.1086/677224 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer M, & Gelman SA (2016). Gender essentialism in children and parents: Implications for the development of gender stereotyping and gender-typed preferences. Sex Roles, 75(9–10), 409–421. [Google Scholar]

- Nederkoorn C, Houben K, Hofmann W, Roefs A, & Jansen A (2010). Control yourself or just eat what you like? Weight gain over a year is predicted by an interactive effect of response inhibition and implicit preference for snack foods. Health Psychology, 29(4), 389–393. pdh. 10.1037/a0019921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newheiser A-K, & Olson KR (2012). White and Black American children’s implicit intergroup bias. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 48(1), 264–270. 10.1016/j.jesp.2011.08.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen SP (2007). An apple a day keeps the doctor away: Children’s evaluative categories of food. Appetite, 48(1), 114–118. 10.1016/j.appet.2006.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen SP, McCullough MB, & Noble A (2011). A theory-based approach to teaching young children about health: A recipe for understanding. Journal of Educational Psychology, 103(3), 594 10.1037/a0023392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nosek BA, Greenwald AG, & Banaji MR (2005). Understanding and using the Implicit Association Test: II. Method variables and construct validity. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 31(2), 166–180. 10.1177/0146167204271418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pesch MH, & Lumeng JC (2018). Early feeding practices and development of childhood obesity In Freemark MS (Ed.), Pediatric Obesity: Etiology, Pathogenesis and Treatment (pp. 257–270). Springer International Publishing; 10.1007/978-3-319-68192-4_15 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pliner P (1994). Development of measures of food neophobia in children. Appetite, 23(2), 147–163. 10.1006/appe.1994.1043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. (2016). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. [Google Scholar]

- Reed DR, & Knaapila A (2010). Genetics of taste and smell: Poisons and pleasures. Progress in Molecular Biology and Translational Science, 94, 213–240. PMC. 10.1016/B978-0-12-375003-7.00008-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehm CD, Peñalvo JL, Afshin A, & Mozaffarian D (2016). Dietary intake among US adults, 1999–2012. JAMA, 315(23), 2542–2553. 10.1001/jama.2016.7491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rioux C, Lafraire J, & Picard D (2018). Visual exposure and categorization performance positively influence 3- to 6-year-old children’s willingness to taste unfamiliar vegetables. Appetite, 120, 32–42. 10.1016/j.appet.2017.08.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rioux C, Picard D, & Lafraire J (2016). Food rejection and the development of food categorization in young children. Cognitive Development, 40, 163–177. 10.1016/j.cogdev.2016.09.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ruby MB, Rozin P, & Chan C (2015). Determinants of willingness to eat insects in the USA and India. Journal of Insects as Food and Feed, 1(3), 215–225. 10.3920/JIFF2015.0029 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz MB, Chambliss HO, Brownell KD, Blair SN, & Billington C (2003). Weight bias among health professionals specializing in obesity. Obesity Research, 11(9), 1033–1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz MB, Vartanian LR, Nosek BA, & Brownell KD (2006). The influence of one’s own body weight on implicit and explicit anti-fat bias. Obesity, 14(3), 440–447. 10.1038/oby.2006.58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigman-Grant M, Byington TA, Lindsay AR, Lu M, Mobley AR, Fitzgerald N, & Hildebrand D (2014). Preschoolers can distinguish between healthy and unhealthy foods: The All 4 Kids Study. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 46(2), 121–127. 10.1016/j.jneb.2013.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhlmann EL, Poehlman TA, & Nosek BA (2012). Automatic associations: Personal attitudes or cultural knowledge In Hanson J & Jost JT (Eds.), Ideology, Psychology, and Law (pp. 228–260). Oxford University Press, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Wardle J, Guthrie CA, Sanderson S, & Rapoport L (2001). Development of the children’s eating behaviour questionnaire. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 42(7), 963–970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wardle J, & Huon G (2000). An experimental investigation of the influence of health information on children’s taste preferences. Health Education Research, 15(1), 39–44. 10.1093/her/15.1.39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werthmann J, Jansen A, Vreugdenhil ACE, Nederkoorn C, Schyns G, & Roefs A (2015). Food through the child’s eye: An eye-tracking study on attentional bias for food in healthy-weight children and children with obesity. Health Psychology, 34(12), 1123–1132. 10.1037/hea0000225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokum S, Ng J, & Stice E (2015). Attentional bias to food iImages associated with elevated weight and future weight gain: An fMRI study. Obesity Reviews, 16, 424–432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.