Abstract

During the COVID-19 crisis period, firms headquartered in high social trust US states perform better than their counterparts from the low social trust states. Stock returns over the crisis period are 3 to 4 percentage points higher, on average, if social trust increases by one standard deviation. The association is stronger for firms of more affected industries (COVID-19 industries). More specifically, a one standard deviation increase of social trust associates with a 6.45% increase of if firms belong to the COVID-19 industries. Next, I analyze the stock market reactions to the Fed’s announcements on March 23, 2020. The results show that firms headquartered in the high trust states benefit less from the announcements because these firms can access to other external financings cheaply. The average three-day announcement and (FF 3-factor adjusted) are higher by 2.5% and 2.6% respectively if firms headquartered in low trust states.

Keywords: Social trust, COVID-19 crisis period, Event study, Leverage, The Fed announcements, Abnormal returns

1. Introduction

Existing literature documents the impacts of social trust on a broad array of financial outcomes (Arrow, 1972, Coleman, 1990). In the macro-level, Putnam (1993) documents that higher social capital with a high level of trust fosters economic growth. More related to the capital market, the social trust allows for higher market participation (Georgarakos and Pasini, 2011, Guiso et al., 2004), larger earnings announcement returns (Pevzner et al., 2015), higher firm-level performance during housing crisis (Lins, Servaes, & Tamayo (hereafter LST, 2017)), and lower crash risk (Li et al., 2017). Although the study of social trust in the stock market performance is substantial, the extent to which social trust impacts stock performance during the COVID-19 crisis period is relatively unexplored in the literature. The purpose of the paper is to address two important questions. First, to see if firms from high trust US states perform better during the COVID-19 crisis period. Second, whether firms’ performances are more (less) sensitive with the Federal Reserve Board’s (hereafter the Fed) announcements during the crisis when firms are headquartered in high (low) trust intensive society.2

I tie the analysis from two different angles: from the perspective of investors and from the viewpoint of corporations. First, from stockholders’ point of view, the decision of whether to invest is not only a matter of risk and return tradeoff, but depends on the reliability of the reported financial information and the fairness of the overall system (Guiso et al., 2008). Importantly, this reliability becomes more vital when the macro-level trust in the country deteriorates due to the sudden emergence of a crisis. As Stiglitz (2008) and Reich (2008) state, social trust weakened when the housing crisis occurred, and the recent COVID-19 pandemic also wakens a mistrust in society (Wadhams, 2020).3 In this situation, ex-ante social trust plays a more crucial role in the declining phase of social trust. More to the point, outside investors usually place more valuation premiums if firms report the financials on time and in more reliable ways, as Merton (1987) states, investors demand more returns if the information asymmetry between managers and investors is high. I argue that managers from the high social trust areas are less likely to withhold bad information, if any (Li et al., 2017), which reduces the likelihood of stock price crash risk. Further, these firms from high trust society tend to report financials more reliably (Berglund and Kang, 2013), which increases investors’ willingness to pay premiums for these firms. Based on the above discussion, I hypothesize that firms headquartered in high trust areas, ex-ante, perform better than expected during the COVID-19 crisis period.

Moreover, the uniqueness of this current crisis imposes a severe impediment to the day to day life because of unanticipated lockdowns, restrictions, travel bans, and social distancing guidelines. For this, some industries such as tourism, travel, transportation, services, and entertainment become more affected than other industries.4 I supplement the analysis regarding the impact of social trust on firms’ performance when the firms belong to the more affected sectors during the crisis period. I argue that firms’ in the affected or distressed industries are subject to more investors’ confidence because these firms engage with more earnings management than their healthy counterparts (Habib et al., 2013). Hence, I expect that firms’ from more affected industries headquartered in high social trust states perform better than other firms in those states.

Second, I analyze the impact of the Fed facilities announcements during the crisis from the lens of the corporations. On March 23, 2020, the Fed announced two facilities to provide easy access to corporate credits to maintain regular operations and capacity by firms during the crisis period. The COVID-19 crisis appeared to be a pure exogenous shock to the market participants. The overall markets tumbled by more than 30%, in one month, from its all-time high position.5 As a result, firms’ liquidity dried up due to the sudden stop in some or all the revenue-generating activities. However, firms’ capacities and crisis management abilities vary substantially in how they can access external financing. Previous studies find that firms located in the high social trust environments enjoy reduced cost of financing (Duarte et al., 2012, Gupta et al., 2018, Hasan et al., 2017, Meng and Yin, 2019) because of reduced monitoring cost and less information asymmetry. Consistent with this belief, firms from the high-trust region can meet up the liquidity by accessing credit with less cost from different sources such as banks (Hasan et al., 2017), public credit (Meng and Yin, 2019), issuing equity (Gupta et al., 2018), and so on. On the other hand, firms headquartered in low trust areas incur higher costs of accessing external funds; thus, these firms might need to take shelter to the Government policy resorts, such as the Fed facilities. Hence, I hypothesize that the impact of the facilities is more prominent for firms headquartered in low social trust states since these firms benefit more from the facilities by accessing affordable credit from the Fed.

I test the hypotheses using 1709 US firms that are constituent of the Russell 3000 index during the crisis period over January 02, 2020 to May 30, 2020.6 I measure social trust using the survey data from the “General Social Survey (GSS)” that the National Opinion Research Center (NORC) conducts. Following LST (2017), social trust is a proportion of respondents who trust most of the people in the society (see also Guiso et al., 2004, Meng and Yin, 2019, Pevzner et al., 2015). After calculating the abnormal returns during the COVID-19 period, I test the hypotheses at the firm-level using cross-sectional regressions.7 I find that state-level social trust is positively related to abnormal returns over the crisis period. The results are both statistically and economically significant. More precisely, if social trust increases by one standard deviation the abnormal returns measured as , , , and increase by 3.95%, 3.957%, 3.20%, and 3.67% respectively. The association is much stronger for firms of the most affected industries, COVID-19 industries. A one standard deviation increase of social trust associates with 6.45% and 7.47% increase of and if firms belong to the COVID-19 industries. Testing the second hypothesis of the impacts of social trust on the announcement day returns, I find that firms headquartered in the low-trust regions benefit more from the Fed announcement. More specifically, firms headquartered in the low-trust states earn and (three days announcement returns) of 2.5% or 2.6%, respectively, higher than firms located in the high-trust states. The results are both statistically and economically significant.

To my best knowledge, this study is the first to offer an analysis of how social trust influences firms’ performance during the COVID-19 crisis period when the macro-level social trust deteriorates. The study by LST (2017) is the closest to this analysis of the effects of US firm-level CSR activities on firms’ performance during the housing crisis of 2008–2009. This study is different from the LST (2017) in several extents. First, they use firm-level CSR activities as a proxy of social capital, while I use the social trust for each of the states where firms are located. Following the claim of Pevzner et al. (2015), I argue that investors tend to believe more about the information provided by the managers of firms from the high trust society, and this reliability of information becomes more prominent during the crisis period. The results complement the findings of LST (2017) that social trust is a crucial macro-level variable that can explain firms’ performance during the crisis periods. Second, I contribute to the impact of the social trust on firms’ performances that are severely affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. The reason for analyzing the affected industries is because the performance of these industries is more sensitive to the investors’ confidence. Lastly, I contribute to event study literature by analyzing the announcement effects of the Fed facilities in the context of the easiness of access to corporate borrowings. Thus, the market reactions to the Fed announcements in light of how easily firms can access external financing is an exciting addition to the existing literature.

The paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents the important events of the study. In Section 3, I briefly describe the extant literature and develop the testable hypotheses. The data and sample statistics are presented in Section 4, followed by the empirical findings with analysis in Section 5. Finally, Section 6 presents discussion and conclusions.

2. Important event dates

Two dates are crucial for the study: the beginning date of the crisis period and the Fed announcement date. In this section, I describe the rationale of why I declare January 02, 2020 as the beginning of the crisis period, and later I describe the Fed intervention facilities briefly.

On December 31, 2019, China reported World Health Organization (WHO) a string of pneumonia-like cases in Wuhan. The next day, the seafood market in Huanan was identified as a suspected center of the outbreak and became closed. The first trading day after these events was January 02, 2020. Thus, I consider January 02, 2020 as the starting date of the COVID-19 crisis period. From January 02, 2020 till May 30, 2020 (end of the sample period) is considered as the crisis period of the pandemic. For the sake of the analysis, I divide the crisis period into two sub-periods: before the Fed intervention crisis period and after the Fed intervention crisis period.

On March 23, 2020, the Fed announced two facilities- “Primary Market Corporate Credit Facility (PMCCF)” and “Secondary Market Corporate Credit Facilities (SMCCF)”,- to provide easy corporate credit and to increase the liquidity of the outstanding bonds (Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, 2020).8 The PMCCF allows companies to access to credit so that firms can better maintain the business operation and existing capacity during the pandemic period. This facility is open to investment-grade companies and also extends the bridge financing for four years. Borrowers can elect to defer interest and principal payment up to the first six months of taking the credits. The other facility, SMCCF, purchases the secondary market investment-grade bonds of US companies, and the objective is to provide broad exposure to the market for investment-grade bonds. These two facilities are designed to extend credit to employers and to support the corporate bond market. The Fed announcement about purchasing the newly issued bonds and loans from the primary market supports firms to meet up the immediate cash requirement by the corporations. The other announcement to purchase the outstanding corporate bonds and ETFs from the secondary market facilitates firms’ leverage.

3. Literature review and hypothesis development

Existing literature examines the impact of the financial crisis of 2008–09 on firms’ performance (e.g., Almeida et al., 2009, Campello et al., 2010, LST, 2017). The stock market performance of the recent pandemic, COVID-19, also examines in limited extents in the literature, such as stocks’ performance of Chinese firms with confirmed COVID cases (Al-Awadhi et al., 2020), global stock market performances (Liu et al., 2020), government interventions and global stock returns (Zaremba et al., 2020, Zhang et al., 2020), market volatility of the announcement of COVID cases (Albulescu, 2020), media panic sentiment and market volatility (Haroon and Rizvi, 2020) and so on. However, the extent of how social trust associates with firms’ performance during the COVID-19 crisis period gets little attention.

According to Stiglitz (2008), the crisis period of 2008–09 made an abrupt collapse of confidence, and the trust also eroded. In this similar vein, the Bloomberg Businessweek recently headlines about the growing mistrust in society during the recent COVID-19 pandemic (Wadhams, 2020). This lack of trust may create a fundamental problem in the overall market, as Reich (2008) states that the lack of trust may fold up Wall Street in its fancy tents. Investors make an investment decision based on the information they acquire about firms. Moreover, the investment decision is more than a risk-return tradeoff, rather how reliable firms’ financial reporting as well as the fairness of the overall system (Guiso et al., 2008). I argue that firms headquartered in high trust societies tend to report more reliably (Berglund and Kang, 2013) and less likely to hoard bad news (Li et al., 2017). Based on the preceding, since the overall trust level decreases during the crisis period, the reliability of information appears a more vital factor in investment decisions. Consistent with this view, I hypothesize that social trust explains the crisis period stock performance positively. I further expect that this association is even more vital for firms of the highly affected industries because the likelihood of earnings management is higher for distressed firms (Habib et al., 2013).

H1a. Social trust is positively associated with the crisis-period stock returns.

H1b. Social trust is more positively associated with the crisis-period stock returns for firms that belong to the affected industries than those of other industries.

A growing stream of research focuses on the role of social trust in the capital structure decision of firms. Hasan et al. (2017) find that firms headquartered in high social trust states can finance with lower credit spreads. In another study using global data, Meng and Yin (2019) find that social trust is negatively associated with the cost of debt. A study on equity financing also reveals a negative association between social trust and the cost of equity (Gupta et al., 2018). In line with these views, firms headquartered in the high social trust regions can finance from various sources at a lower cost than their peers from low trust regions; thus, benefit less from the Fed’s facilities. Based on the above discussion, I hypothesize that firms from low social trust states benefit more from the Fed facilities; thus, the announcement day returns are more positive for firms from low social trust states.

H2. Announcement day returns are more positive for firms headquartered in the low trust society than those of high trust societies.

4. Sample and summary statistics

4.1. Sample construction

In this section, I explain how I construct the sample and measure the performance during the sample period. I consider the firms belong to the Russell 3000 index. I obtain daily stock price data from the COMPUSTAT Capital IQ North America Daily database. The prices are adjusted by the dividends adjustment factor (adjustment factors cumulative ex-ante), and the daily total return factor that are reported by COMPUSTAT. Consistent with the existing literature, I exclude financial firms (GIS industry code of 40) from the sample. To estimate the abnormal returns, I use both CAPM-adjusted abnormal return and Fama and French (FF) 3 factors adjusted abnormal returns.

Following the methodology of Ramelli and Wagner (2020), I estimate each firm’s market beta, size, and value loadings. For this, the year 2019’s daily excess returns are regressed on daily market excess returns, size, and value factors. Excess market return, size, value, and the risk-free rate (US one-month T bill rate) are collected from Kenneth French’s Website. To make the estimate unbiased from illiquid stocks, I drop firms that have less than 127 daily trading observations in the estimation period. After computing the three-factor loadings, the CAPM adjusted abnormal returns are calculated by subtracting the beta times the market excess return from the excess returns of the stocks. Similarly, I calculate the Fama and French three factors adjusted returns of a firm as the excess stock returns minus factor exposures times the factor returns. To make the study robust, I consider both cumulative abnormal returns () and buy and hold abnormal returns () over the COVID-19 period and three-day abnormal returns surrounding the Fed announcement on March 23, 2020. I collect firm-specific financial data from the COMPUSTAT annual database. For cross-sectional analysis, I use the firm-level characteristics one-year lag of the stock returns; thus, I use the financial data from the year 2019. I focus on firms for which 2019 fiscal year-end data is available from Compustat. After applying all the filtering approaches, the final sample stands for 1709 firms. Lastly, US state-level controls are collected from various sources: US Census Bureau, Bureau of Economic Analysis, and US Labor Statistics database.

Social Trust, , is measured from the General Social Survey (GSS) responses conducted by National Opinion Research Center (NORC) following the methodology used by LST (2017).9 is the proportion of the positive answers from the respondents to the following questions: “Generally speaking, would you say that most people can be trusted or that you cannot be too careful in dealing with people?” I use the 2016 survey to construct the trust measure.10 There are 2867 respondents from the nine regions of US. First, I drop 77 responses that answer the question- “It depends”. Then, I remove another 920 responses that answer “Don’t know or N/A”. After cleaning these responses, I find 1,867 responses, of which 33.4% report they trust most of the people in the society. Then, I assign social trust to each firm based on the headquarter location from the COMPUSTAT variable “state”.

Table 2.

Mean abnormal return before and after the Fed intervention.

| Region | Social trust |

|

|

|

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before Fed Intervention | After Fed Intervention | Before Fed Intervention | After Fed Intervention | Before Fed Intervention | After Fed Intervention | Before Fed Intervention | After Fed Intervention | ||

| Panel A: Abnormal return by region before and after the Fed intervention | |||||||||

| West South Cent | 0.216 | −0.265 | 0.107 | −0.071 | 0.111 | −0.249 | 0.069 | −0.090 | 0.078 |

| East South Cent | 0.269 | −0.116 | 0.135 | 0.002 | 0.135 | −0.118 | 0.116 | 0.013 | 0.125 |

| South Atlantic | 0.313 | −0.096 | 0.073 | −0.042 | 0.076 | −0.084 | 0.050 | −0.031 | 0.058 |

| Mountain | 0.344 | −0.176 | 0.150 | −0.100 | 0.155 | −0.186 | 0.140 | −0.123 | 0.145 |

| East North Cent | 0.356 | −0.117 | 0.005 | 0.006 | 0.005 | −0.118 | −0.010 | 0.012 | −0.004 |

| Pacific | 0.361 | 0.101 | 0.049 | 0.021 | 0.052 | 0.101 | 0.030 | 0.025 | 0.034 |

| Mid Atlantic | 0.367 | −0.060 | 0.069 | −0.018 | 0.072 | −0.058 | 0.037 | −0.009 | 0.043 |

| West North Cent | 0.400 | −0.048 | −0.017 | 0.034 | −0.016 | −0.059 | −0.035 | 0.060 | −0.034 |

| New England | 0.412 | 0.115 | 0.026 | 0.078 | 0.031 | 0.111 | 0.012 | 0.090 | 0.018 |

| Panel B: Abnormal return by trust tercile before and after the Fed intervention | |||||||||

| Low Trust | 0.265 | −0.173 | 0.094 | −0.050 | 0.098 | −0.161 | 0.065 | −0.053 | 0.074 |

| Medium Trust | 0.357 | −0.005 | 0.055 | −0.004 | 0.058 | −0.006 | 0.039 | −0.004 | 0.043 |

| High Trust | 0.389 | 0.010 | 0.041 | 0.027 | 0.044 | 0.008 | 0.018 | 0.039 | 0.023 |

The sample consists of 1709 firms from the Russell 3000 index. Return data is from January 02, 2020 to May 30, 2020. is the cumulative abnormal return during the sample period with market model parameters estimated over the previous year’s (January 01, 2019 to December 31, 2019) daily return. is the cumulative abnormal return with Fama–French three factors model and parameters estimated over the previous year’s daily return. is the buy and hold abnormal return with market model parameters estimated over the previous daily return. is the buy and hold abnormal return with Fama–French three factors model parameters estimated over the previous year’s daily returns. Social trust is the proportion of the response that respondents trust most of the people in the society. Region is defined as a region of the respondents participates in the survey of the General Social Survey (GSS) by the National Opinion Research Center. Before-Fed Intervention period is January 02, 2020 to March 23, 2020. After-Fed intervention is from March 24, 2020 to May 30, 2020. Panel A reports the mean abnormal returns by the trust region segregated into two sub-periods. Panel B reports the mean abnormal returns sorted by the trust tercile.

4.2. Descriptive statistics

Table 1 displays the stock returns of the firms over the crisis period from January 02, 2020 to May 30, 2020. In Panel A, I report the abnormal returns of the full sample period. For the sample as a whole, the average (median) is 1.4% (0.5%), while the is 5.7% (2.9%). The average value of is −4.7%, and the median value is −8.9%. Lastly, the mean FF three-factor adjusted BHAR, , is −0.9%, when the median value is −6.2%. In Panel B, I report the abnormal returns of the crisis period segregated by the before and after the Fed intervention date.11 I find that the mean abnormal returns, both CAR and BHAR, are negative in the pre-Fed Intervention period but turn positive in the post-Fed Intervention period. The mean is 6.2% and the median is 3.9% after the Fed intervention period, while the before-intervention period mean (median) is −4.8% (−4.4%).

Table 1.

Summary statistics of abnormal return.

| Mean | p5 | p25 | Median | p75 | p95 | N | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A: Full Sample period | |||||||

| 0.014 | −0.566 | −0.205 | 0.005 | 0.184 | 0.638 | 1709 | |

| 0.057 | −0.471 | −0.164 | 0.029 | 0.220 | 0.725 | 1709 | |

| −0.047 | −0.565 | −0.283 | −0.089 | 0.101 | 0.580 | 1709 | |

| −0.009 | −0.502 | −0.229 | −0.062 | 0.121 | 0.628 | 1709 | |

| Panel B: Before and After Fed Intervention | |||||||

| Before Fed Intervention | |||||||

| −0.048 | −0.720 | −0.266 | −0.044 | 0.167 | 0.550 | 1709 | |

| −0.008 | −0.609 | −0.236 | −0.023 | 0.203 | 0.591 | 1709 | |

| −0.046 | −0.584 | −0.287 | −0.089 | 0.132 | 0.571 | 1709 | |

| −0.004 | −0.513 | −0.256 | −0.069 | 0.172 | 0.636 | 1709 | |

| After Fed Intervention | |||||||

| 0.062 | −0.391 | −0.117 | 0.039 | 0.213 | 0.600 | 1709 | |

| 0.065 | −0.381 | −0.117 | 0.035 | 0.216 | 0.602 | 1709 | |

| 0.040 | −0.371 | −0.153 | −0.002 | 0.171 | 0.603 | 1709 | |

| 0.046 | −0.369 | −0.148 | 0.002 | 0.175 | 0.604 | 1709 | |

| Panel C: Descriptive Statistics of control variables | |||||||

| Total Asset | 7847.070 | 90.9200 | 410.253 | 1427.206 | 4729.200 | 33876.361 | 1709 |

| Book to Market | 0.558 | 0.134 | 0.311 | 0.522 | 0.764 | 1.075 | 1709 |

| Leverage Ratio | 0.304 | 0.000 | 0.107 | 0.279 | 0.431 | 0.718 | 1709 |

| Cash to Asset | 0.239 | 0.004 | 0.038 | 0.115 | 0.353 | 0.853 | 1709 |

| Profitability | −0.021 | −0.541 | −0.015 | 0.054 | 0.101 | 0.202 | 1709 |

| Momentum | 0.270 | −0.521 | −0.067 | 0.200 | 0.464 | 1.084 | 1709 |

| Idios. Volatility | 0.415 | 0.167 | 0.249 | 0.348 | 0.512 | 0.841 | 1709 |

| Social Trust | 0.340 | 0.216 | 0.313 | 0.361 | 0.366 | 0.412 | 1709 |

| Panel D: Correlation Matrix | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) |

| (1) Social Trust | 1.000 | |||||||

| (2) Size | −0.125 | 1.000 | ||||||

| (3) Book to Market | −0.268 | 0.244 | 1.000 | |||||

| (4) Lev Ratio | −0.104 | 0.245 | 0.083 | 1.000 | ||||

| (5) Cash to Asset | 0.274 | −0.536 | −0.457 | −0.292 | 1.000 | |||

| (6) Profitability | −0.142 | 0.497 | 0.131 | 0.106 | −0.588 | 1.000 | ||

| (7) Momentum | 0.049 | −0.015 | −0.216 | −0.054 | 0.115 | 0.029 | 1.000 | |

| (8) Idio. Volatility | 0.030 | −0.481 | 0.037 | −0.067 | 0.455 | −0.511 | 0.120 | 1.000 |

The sample consists of 1709 firms from the Russell 3000 index. Return data is from January 02, 2020, to May 30, 2020. is the cumulative abnormal return during the sample period with market model parameters estimated over the previous year’s (January 01, 2019 to December 31, 2019) daily return. is the cumulative abnormal return with Fama–French three factors model and parameters estimated over the previous year’s daily return. is the buy and hold abnormal return with market model parameters estimated over the previous daily return. is the buy and hold abnormal return with Fama–French three factors model parameters estimated over the previous year’s daily return. Panel A reports the abnormal returns of the full sample. Panel B reports the abnormal returns segregated into before and after the Fed announcement date period. Panel C reports the descriptive statistics of control variables. Size is the natural log of total assets. Book to Market is the book value scaled by the market value of a firm. Leverage ratio is the sum of long-term debt and short-term debt scaled by total assets. Cash to Asset is the ratio of cash and short-term liabilities by total assets. The EBIT scaled by total assets measures profitability. Momentum is the buy and hold raw return for the daily return from January 02, 2019 to December 31, 2019. Idios. Volatility is calculated as the residual standard error from the market model estimated over the last year. Panel D reports the correlation matrix of the control variables.

Panel C provides descriptive statistics for the variables used in the regression. To capture the firm-level heterogeneity, I control five variables following the existing literature (LST, 2017): size, book to market, total leverage ratio, cash to total asset, and profitability. Table A.1 reports variable descriptions in detail. The first row of Panel C reports the summary statistics of the size of the firms used in the sample. The mean size of the firms is 7847 million when the fifty-percentile value is 1427 million. The second row shows the book to market ratio with a mean of 0.558 and the median of 0.552, meaning the sample firms are growth firms on average. The next row presents the leverage ratio, where the mean total leverage ratio is 0.304 and the median value is 0.279. The other two firm-level control variables are cash to asset and profitability with the mean (median) value of 0.239 (0.115), −0.021 (0.054) respectively. Next, I control two stock price-related factors: the previous years’ stock performance (momentum), and the idiosyncratic volatility (the residual standard error from the market model estimated over the last year using daily stock returns, Fu (2009)). I take these two controls because firms’ previous years’ returns can predict stock returns (Jegadeesh and Titman, 1993), and Goyal and Santa-Clara (2003) find that firms’ idiosyncratic volatility associates positively with stock returns. The average holding period return for the previous year (momentum) is 0.270, and the mean idiosyncratic volatility is 0.415. Lastly, the variable of interest, social trust, has a mean (median) value of 0.34 (0.361). Panel D presents a correlation matrix of all the firm-level control variables employed in the baseline model.

Table A.1.

Description of Variables.

| Variable name | Description | Source |

|---|---|---|

| CAPM adjusted daily abnormal return | COMPUSTAT (Daily) | |

| FF3 factors adjusted daily abnormal return | COMPUSTAT (Daily) | |

| After (Before)-Fed Interven. | From March 24, 2020 till May 30, 2020 (January 02, 2020 till March 23, 2020) | Federalreserve.gov |

| CAPM adjusted buy and hold abnormal returns. The expected return is calculated based on the market model. Coefficients are estimated over the previous one-year daily excess market return on daily excess return. | COMPUSTAT North America Security Daily | |

| Fama and French 3 factor model adjusted buy and hold abnormal return. The expected return is calculated based on the FF 3 factor model. Coefficients are estimated over the previous one-year daily excess market return, size, and value factor on the daily excess return. | COMPUSTAT North America Security Daily and Kenneth French Website | |

| Book to Market | Total Asset/ (Closing Price* Share Outstanding+ Total Asset- Equity value(ceq)) | COMPUSTAT |

| CAPM adjusted cumulated abnormal return. The expected return is calculated based on the market model. Coefficients are estimated over the previous one-year’s daily excess market return on daily excess return. | COMPUSTAT North America Security Daily | |

| Fama and French 3 factor model adjusted cumulative abnormal return. The expected return is calculated based on the FF 3 factor model. Coefficients are estimated over the previous one-year daily excess market return, size, and value factor on the daily excess return. | COMPUSTAT North America Security Daily and Kenneth French Website | |

| Cash to Asset | che/Total Asset | COMPUSTAT |

| COVID Industries | COVID-19 industries are defined as Fama–French 49 industries Entertainment, Construction, Automobiles and trucks, Aircraft, Ships, Personal Services, Business Services, Transportation, Wholesale, Retail, and Restaurants, hotels, and motels. | OECD (2020) |

| Crisis | January 02, 2020 to May 30, 2020 | |

| GDP per capita | The state-level per capita GDP | Bureau of Econ Analy. |

| High Trust | Top tercile of social trust. | NORC |

| Median Age | State-level median age | US Census Bureau |

| Momentum | Firms’ raw holding period returns over the period of January 01, 2019 to December 31, 2019. | COMPUSTAT North America Security Daily |

| Idiosyncratic Volatility | IVOL=Std. Dev (Errors)* . Errors are calculated based on the market model over the previous years’ daily return data. | COMPUSTAT North America Security Daily |

| Leverage Ratio | (Long term debt(dltt)+ Short-term debt(dlc))/Total Asset | COMPUSTAT |

| Low Trust | Bottom tercile of social trust. | NORC |

| Profitability | EBIT/Total Asset | COMPUSTAT |

| Region | New England: Maine, Vermont, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Connecticut, Rhode Island. Mid Atlantic: New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania. East North Cent.: Wisconsin, Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Ohio. West North Cent.: Minnesota, Iowa, Missouri, North Dakota, South Dakota, Nebraska, Kansas. South Atlantic: Delaware, Maryland, West Virginia, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Florida, DC. East South Cent.: Kentucky, Tennessee, Alabama, Mississippi. West South Cent.: Arkansas, Oklahoma, Louisiana, Texas. Mountain: Montana, Idaho, Wyoming, Colorado, Nevada, Utah, Arizona, New Mexico. Pacific: Washington, Oregon, California, Alaska, Hawaii | National Opinion Research Center (NORC) |

| RawReturn | Raw return= ((adj_-ret-l.adj_ret)/l.adj_ret)*(1+trfd/100). Where adj_ret= prccd / ajexdi. ajexdi is dividend adjustment factor. trfd is daily total return factor. | COMPUSTAT North America Security Daily. |

| Size | Ln(Total Asset) | COMPUSTAT |

| Social Trust | If respondents of the GSS survey answer yes to the following question: “Generally speaking, would you say that most people can be trusted.” | NORC |

| Unemployment rate | The state-level unemployment rate for the year 2019 and 2018 | US Bureau of Labor Statistics |

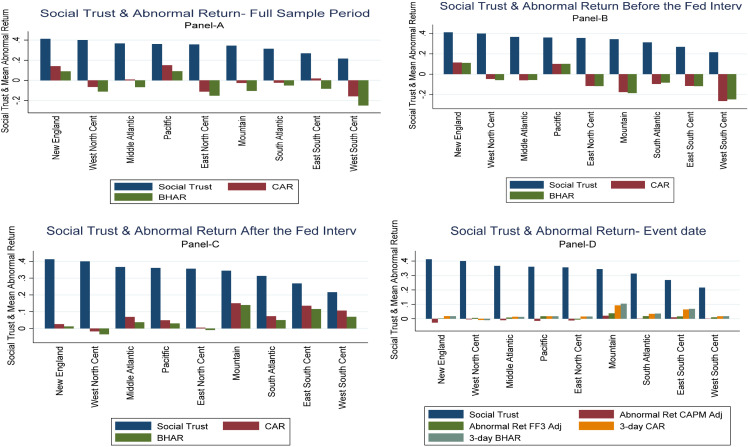

In Table 2, the abnormal returns are reported by the trust regions. The NORC’s GSS survey divides US into nine regions (see Table A.1 about the state composition by regions). Panel A reports abnormal returns for each of the regions by segregating into two sub-periods: before-Fed intervention and after-Fed intervention. The social trust measure is high in the New England region with 41.2% people trusting most of the people in the society, and in contrast, people of the West South Central trust each other the least in the society with an average value of 21.6%. Before Fed intervention, the firms located in the New England region have of 11.5%, while the firms from West South Central reports of −26.5% during the same crisis period. However, after the Fed intervention, the CAR of lower social trust areas become more positive than that of higher social trust areas. The pattern is almost identical for all other measures of abnormal returns. To observe the relationship more closely, I create a tercile portfolio of firms based on social trust of firms’ location. The findings suggest that firms in lower social trust areas report more substantial abnormal returns after the Fed intervention than those of high social trust areas. These findings motivate us to study the association of social trust on firms’ performance during the COVID-19 crisis with an intervention from the Fed. Fig. 1 reports the abnormal returns by the social trust regions. Panel A, B, and C exhibit the and by regions during the full sample period, before the Fed intervention, and after the Fed intervention. Panel D displays the event date and 3-day and of the Fed policy announcements. The figure provides a clear view that the abnormal returns are more positive (negative) before the Fed intervention for firms headquartered in the high (low) trust area. The after-intervention CAR and BHAR are higher for low trust societies. The announcement day returns both one-day and three-days are more positive for firms located in low trust states.

Fig. 1.

This figure displays Social Trust and Abnormal Returns by Region. CAR and BHAR are market model adjusted abnormal returns. Sample Period ranges from January 02, 2020 to May 30, 2020. The sample consists of 1709 firms from Russell 3000. Before Fed Intervention covers from January 02, 2020 to March 23, 2020, while After Fed intervention is from March 24, 2020 till May 30, 2020. The event date is March 23, 2020. Abnormal return CAPM (FF3) adjusted is the market model (Fama and French 3 factors) adjusted announcement date return. 3-days CAR and BHAR (market model adjusted) are from −1 day to +1 day of the event date (March 23, 2020 to March 25, 2020).

5. Empirical results

5.1. Baseline regression

I estimate various regression models of stock returns during the COVID-19 crisis period as a function of the pre-COVID-19 period social trust. For the primary hypothesis, I regress the crisis period cumulative or buy and hold abnormal returns on social trust along with a number of control variables. Precisely, I estimate the following regression model:

| (1) |

Where, is the abnormal returns over the crisis period. I consider four abnormal returns as the dependent variable: , , , and . is the proportion of the positive answers from the survey respondents, of state k, that they trust most of the people. is a vector of control variables. Following LST (2017) and Ramelli and Wagner (2020), I control firms’ size, book to market, total leverage ratio, cash to total asset, profitability, momentum, idiosyncratic volatility, and Fama–French three-factor loadings in the models. I also control three state-level variables to capture the state-level variation: unemployment rate, GDP per capita, and the median age of the state. is the Fama and French 49 industry dummies and is the white noise when standard errors are clustered at a firm-level.12

Table 3 contains the results of the baseline regressions. The variable of interest is the . Columns (1) to (4) report the regression results when I do not control any firm-level and state-level variables. The result shows that social trust is positively and significantly associated with the crisis period abnormal returns. The results are economically significant, meaning that a one standard deviation increase of social trust (0.063) is associated with 3.95%, 3.96%, 3.20%, and 3.67% increase of , , , and respectively during the COVID-19 crisis period. One big concern is whether the association is due to firm-level omitted variables that may be correlated with the , rather than due to the itself. To overcome the concern, I re-run the regressions controlling the firm-level and state-level control variables mentioned earlier. I find the results robust. More specifically, the results from columns (5) to (8) confirm that firms’ location in high social trust states matters to the higher stock returns during the COVID-19 crisis period. An economic interpretation of the coefficients is as follows: a one standard deviation increase of is associated with the increase in , , , and by 3.74%, 3.745%, 3.21%, and 3.61% consecutively. These results qualitatively confirm the hypothesis H1a that social trust associates with better performance during the crisis periods.

Table 3.

Baseline regression.

| (1) |

(2) |

(3) |

(4) |

(5) |

(6) |

(7) |

(8) |

(9) |

(10) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COVID-19 Industries |

||||||||||

| Social Trust | 0.627⁎⁎⁎ | 0.627⁎⁎⁎ | 0.509⁎⁎ | 0.582⁎⁎ | 0.593⁎⁎ | 0.593⁎⁎ | 0.501⁎ | 0.574⁎ | 1.024⁎⁎ | 1.186⁎⁎ |

| (0.204) | (0.204) | (0.255) | (0.277) | (0.248) | (0.248) | (0.292) | (0.321) | (0.448) | (0.522) | |

| Size | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.008 | 0.007 | 0.004 | −0.000 | ||||

| (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.009) | (0.015) | (0.016) | |||||

| Book to Market | −0.095⁎ | −0.094⁎ | −0.139⁎⁎ | −0.141⁎⁎ | −0.319⁎⁎⁎ | −0.328⁎⁎⁎ | ||||

| (0.054) | (0.054) | (0.057) | (0.061) | (0.091) | (0.102) | |||||

| Leverage Ratio | 0.076 | 0.076 | 0.170 | 0.148 | 0.052 | 0.053 | ||||

| (0.064) | (0.064) | (0.165) | (0.145) | (0.061) | (0.075) | |||||

| Cash to Assets | 0.102 | 0.102 | 0.118⁎ | 0.091 | −0.014 | −0.007 | ||||

| (0.064) | (0.064) | (0.069) | (0.068) | (0.154) | (0.171) | |||||

| Profitability | −0.212⁎⁎⁎ | −0.212⁎⁎⁎ | −0.140⁎ | −0.171⁎⁎ | −0.389 | −0.478 | ||||

| (0.077) | (0.077) | (0.079) | (0.077) | (0.310) | (0.413) | |||||

| Momentum | −0.022⁎⁎⁎ | −0.022⁎⁎⁎ | −0.026⁎⁎ | −0.017⁎ | 0.000 | −0.001 | ||||

| (0.007) | (0.007) | (0.011) | (0.010) | (0.044) | (0.045) | |||||

| Idios. Volatility | 0.112⁎ | 0.112⁎ | 0.098 | 0.079 | 0.171 | 0.027 | ||||

| (0.066) | (0.065) | (0.082) | (0.084) | (0.185) | (0.212) | |||||

| Constant | −0.232⁎⁎⁎ | −0.232⁎⁎⁎ | −0.193⁎ | −0.208⁎ | −0.345 | −0.345 | −0.342 | −0.355 | −0.031 | 0.314 |

| (0.080) | (0.080) | (0.113) | (0.118) | (0.227) | (0.227) | (0.243) | (0.266) | (0.491) | (0.655) | |

| Obs. | 1709 | 1709 | 1709 | 1709 | 1709 | 1709 | 1709 | 1709 | 425 | 425 |

| R-squared | 0.178 | 0.171 | 0.166 | 0.099 | 0.208 | 0.201 | 0.191 | 0.123 | 0.280 | 0.227 |

| 3 Factor Loadings | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| State Controls | NO | NO | NO | NO | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Industry FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

This table presents regression results of social trust on abnormal returns. is the cumulative abnormal return during the sample period with market model parameters estimated over the previous year’s (January 01, 2019 to December 31, 2019) daily return. is the cumulative abnormal return with Fama–French three factors model parameters estimated over the previous year’s daily return. is the buy and hold abnormal return with market model parameters estimated over the previous daily return. is the buy and hold abnormal return with Fama–French three factors model parameters estimated over the previous year’s daily return. Social Trust is the proportion of the response that respondents trust most of the people in the society. Size is the natural log of total assets. Book to Market is the book value scaled by the market value of a firm. Leverage ratio is the sum of long-term and short-term debt scaled by total assets. Cash to Asset is cash and short-term liabilities scaled by total assets. Profitability is the EBIT scaled by total assets. Momentum is the buy and hold raw daily return from January 02, 2019 to December 31, 2019. Idiosyncratic volatility is calculated as the residual standard error from the market model estimated over the last year. State-level controls are the unemployment rate, GDP per capita, and median age. Three factors loadings are Fama–French Three factors loadings. The industry is Fama and French 49 industry. COVID19 industries are defined as Fama–French 49 industries: Entertainment, Construction, Automobiles and trucks, Aircraft, Ships, Personal Services, Business Services, Transportation, Wholesale, Retail, and Restaurants, hotels, and motels. Numbers in parentheses are heteroskedasticity-consistent standard error clustered at the firm level.

Indicate the parameter estimates are significant at 1% level.

Indicate the parameter estimates are significant at 5% level.

Indicate the parameter estimates are significant at 10% level.

Lastly, I analyze whether the association is higher for firms that belong to the directly affected industries, COVID-19 industries. Following OECD (2020), I identify the following sectors are the most affected, from Fama and French 49 industries: Entertainment, Construction, Automobiles and trucks, Aircraft, Ships, Personal Services, Business Services, Transportation, Wholesale, Retail, and Restaurants, hotels, and motels. Columns 9 and 10 report the cross-sectional regression for the sub-sample of 425 firms from the COVID-19 industries. I find that the coefficients of and are higher than those of the full sample.13 A one standard deviation increase of social trust associates with the higher and by 6.45% and 7.47% respectively, while the and of full sample increase by 3.74% and 3.61% consecutively. These results support the hypothesis H1b that firms from the affected industries perform better than those of other industries during the crisis if the affected industries’ firms are headquartered in high trust states.

5.2. Comparing returns before and during the COVID-19 crisis period

The findings so far evidence that ex-ante positively affects the stock returns during the COVID-19 crisis period when the overall trust in the society deteriorates. In this section, I extend the investigation to whether the positive association is unique during the crisis periods or is common to the pre-crisis periods, perhaps due to some unobservable risk factors that correlate with the .14 To address this issue, I adopt a difference in difference (DID) model with industry and time fixed effects.15 More precisely, I construct a Panel dataset of daily returns starting on January 02, 2019, one year before the crisis begins, and ending on May 30, 2020. For this Panel dataset, I estimate the following model:

| (2) |

Where, is the raw return, , or abnormal returns (). is a dummy variable set to one if the data lies between January 02, 2020 and May 30, 2020. is a dummy variable one if the data lies between January 02, 2019 and December 31, 2019. and are the industry and month fixed effects. I take the same control variables that I use in the baseline regression as well as the variable of interest, state-level social trust(). captures the differential impact of social trust on daily returns during the crisis period from January 02, 2020 to May 30, 2020.

Table 4 depicts the results of regressions of social trust on , (CAPM adjusted abnormal returns), and (FF3 factors adjusted returns). In all the specifications, the increase of of states, where firms headquartered, results in superior performance during the COVID-19 crisis period. In terms of economic significance for column 1, the interaction term of 0.009 on the suggests that a one standard deviation increase of (0.063) is associated with six basis points higher daily raw returns during the crisis period. For columns 2 and 3, the interaction terms are 0.009 and 0.003, which mean that the daily abnormal returns are higher by six basis points and two basis points respectively for and during the crisis periods with an increase of one standard deviation of . Columns (4) to (6) report the interaction coefficients when I include the firm-level and state-level control variables. The results are similar to columns (1) to (3). These results indicate that the association of social trust and abnormal returns is unique during the crisis period. The bottom two rows report the difference of coefficients tests from the crisis period to the pre-crisis periods. I find that the difference of coefficient tests are 0.01 for columns (1), (2), (4), and (5), meaning that one standard deviation of increase in social trust enhances the net firms’ performance by 6.3 basis points. The results offer a robust view that social trust explains the crisis period returns.

Table 4.

Abnormal returns surrounding COVID and social trust.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| * | 0.009⁎⁎⁎ | 0.009⁎⁎⁎ | 0.003⁎ | 0.009⁎⁎⁎ | 0.009⁎⁎⁎ | 0.003⁎ |

| (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | |

| * | −0.001 | −0.001 | 0.002⁎⁎⁎ | −0.001 | −0.001 | 0.002⁎⁎ |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | |

| Constant | 0.006⁎⁎⁎ | 0.003⁎⁎⁎ | 0.000 | 0.005⁎⁎⁎ | 0.002⁎ | −0.001 |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | |

| Obs. | 582034 | 582034 | 582034 | 576994 | 576994 | 576994 |

| R-squared | 0.010 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.010 | 0.002 | 0.001 |

| Firm-Level Controls | NO | NO | NO | YES | YES | YES |

| Three-Factor Loadings | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| State-Level Controls | NO | NO | NO | YES | YES | YES |

| Month FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Industry FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Std. errors clustered by | Firm | Firm | Firm | Firm | Firm | Firm |

| * (Crisis- Pre-Crisis) | 0.010⁎⁎⁎ | 0.010⁎⁎⁎ | 0.001 | 0.010⁎⁎⁎ | 0.010⁎⁎⁎ | 0.001 |

| Z-value | 4.776 | 4.693 | 0.415 | 4.737 | 4.742 | 0.453 |

Indicate the parameter estimates are significant at 1% level.

Indicate the parameter estimates are significant at 5% level.

Indicate the parameter estimates are significant at 10% level.

5.3. Social trust, firms’ performance, and policy intervention

In this section, I analyze the market reactions to the Fed policy announcements on March 23rd, 2020. The purpose of the section is to examine how sensitive firms’ performances are on policy announcements based on firms’ location. I argue that firms headquartered in the higher social trust regions benefit less from the policy announcements to the crisis. Extant literature finds that firms headquartered in the higher level of social trust regions incur the lower credit spreads (Hasan et al., 2017, Meng and Yin, 2019). In another study using global data, Mazumder and Rao (2020) find that firms headquartered in high trust countries use more long-term debt. As a result, firms headquartered in high trust states can finance from the other sources such as banks (Hasan et al., 2017), private placement, public debt (Meng and Yin, 2019), issuing equity (Gupta et al., 2018), and so on, quite cheaply; thus, rely less on the Fed facilities. Table 5 reports the association of social trust on abnormal returns surrounding the Fed’s policy announcement date.

Table 5.

Market reactions to the Fed policy intervention.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A: Mean announcement day Return | ||||

| Announcement day Return March 24, 2020 |

3 Day (−1 to +1) Abnormal Return (March 23 to March 25, 2020) |

|||

| Low Trust | 0.006 | 0.019 | 0.045 | 0.048 |

| Medium Trust | −0.013 | 0.010 | 0.025 | 0.026 |

| High Trust | −0.016 | 0.006 | 0.020 | 0.020 |

| Panel B: Cross-sectional regression of social trust on announcement day and 3-day Abnormal Return | ||||

| Announcement day Return March 24, 2020 |

3 Day (−1 to +1) Abnormal Return (March 23 to March 25, 2020) |

|||

| 0.015⁎⁎ | 0.016⁎⁎⁎ | 0.025⁎⁎⁎ | 0.026⁎⁎⁎ | |

| (0.006) | (0.006) | (0.009) | (0.010) | |

| Firm-Level and State-Level Controls | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Constant | 0.002 | 0.041⁎⁎ | 0.037 | 0.033 |

| (0.015) | (0.016) | (0.084) | (0.089) | |

| Obs. | 1709 | 1709 | 1709 | 1709 |

| R-squared | 0.170 | 0.146 | 0.177 | 0.183 |

| Industry FE | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Panel C: Cross-sectional regression of social trust on cumulative returns before and after the Fed intervention | ||||

| Before Fed Intervention (January 02, 2020 to March 23, 2020) |

After Fed Intervention (March 24, 2020 to May 30, 2020) |

|||

| 0.617⁎⁎⁎ | 0.607⁎⁎ | −0.024 | 0.077 | |

| (0.231) | (0.298) | (0.194) | (0.194) | |

| Firm-Level and State-Level Controls | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Constant | −0.563⁎⁎⁎ | −0.671⁎⁎⁎ | 0.218 | 0.314⁎ |

| (0.188) | (0.209) | (0.172) | (0.188) | |

| Obs. | 1709 | 1709 | 1709 | 1709 |

| R-squared | 0.297 | 0.287 | 0.211 | 0.223 |

| Three-Factor Loadings | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Industry FE | YES | YES | YES | YES |

This table reports the mean event date returns and cross-sectional regression results of social trust on abnormal return surrounding the event date. In Panel A, I report the mean value of abnormal return in the announcement day and 3-day abnormal returns. Panel B reports the cross-sectional regressions of announcement day abnormal return () and 3-days window abnormal returns. is the cumulative abnormal return during the sample period with FF 3 factor model parameters estimated over the previous year’s (January 01, 2019 to December 31, 2019) daily return. is the buy and hold abnormal return with FF 3 factors model parameters estimated over the previous daily return. Panel C reports the regression results of the cross-sectional regression of social trust on the abnormal returns before and after the fed intervention. After-Fed Intervention period starts from March 24th, 2020. Social trust is the proportion of the response that respondents trust most of the people in the society. The following control variables are taken in Panels B and C: Size is the natural log of total assets. Book to Market is the book value scaled by the market value of a firm. Leverage ratio is the sum of long-term debt and short-term debt scaled by total assets. Cash to Asset is cash and short-term liabilities scaled by total assets. Profitability is the EBIT scaled by total assets. Momentum is the buy and hold raw return for the daily return over January 02, 2019 to December 31, 2019. Idiosyncratic volatility is calculated as the residual standard deviation from the market model estimated over the last year. State-level controls are the unemployment rate, GDP per capita, and median age. Three factors loadings are Fama–French three factors loadings are calculated with the daily return over the last year. The industry is Fama and French 49 industry. Except when otherwise indicated, numbers in parentheses are heteroskedasticity- consistent standard error clustered at the firm level.

Indicate the parameter estimates are significant at 1% level.

Indicate the parameter estimates are significant at 5% level.

Indicate the parameter estimates are significant at 10% level.

Table 5 Panel A reports the mean announcement-day returns and three-day announcement returns sorted by the social trust tercile. Columns (1) and (2) report the mean announcement day returns. Both the CAPM and FF3 adjusted returns, and , are monotonically negatively associated with the increase of trust in society. Columns (3) and (4) report the three days (-1 to +1) FF three-factor adjusted CAR and BHAR, ( and ) sorted by social trust tercile. I find that three-day and are 4.5% and 4.8% for the firms headquartered in the low trust states, while both the returns are 2.0% for the firms in the high trust states. In Panel B, I run the cross-sectional regressions of social trust on the announcement day abnormal returns. Consistent with the observed association in Panel A, the results show that the coefficient of dummy is associated positively with the announcement day returns both in and . The results show that firms’ announcement day returns, and , are higher by 1.5% and 1.6% if the firms’ locations are in low trust-region. Both the coefficients are economically and statistically significant at 1% level. In columns (3) and (4), I find that the three-day abnormal returns are positively associated with low social trust. More specifically, firms’ and increase by 2.5% or 2.6% if firms’ locations are in low trust states. Both the statistics are statistically significant at 1% level. The results offer robust evidence in favor of the hypothesis H2 that firms from low trust states benefit more from the Fed announcements on March 23, 2020.

Panel C reports the regression results of social trust on and in the two sub-crisis periods: before and after the Fed announcement date. I primarily expect that social trust plays a significant role during the crisis period without policy intervention, which helps to overcome the liquidity crisis of a firm. Consistent with the belief, I find that the pre-Fed intervention crisis period cumulative abnormal returns are positively associated with . Columns (1) and (2) in Panel C report that the increases by 3.9% and increases by 3.8% if social trust increases by one standard deviation. The results are both economically and statistically significant at 1% level. Analysis of the post-Fed intervention period shows that the and are statistically non-significant with the . Overall, the result offers robust evidence in support of the claim that the matters for firms’ performance during the crisis periods, especially without the policy support to access the credit from the Fed.

6. Discussion and conclusion

In this paper, I examine the value of social trust during the unexpected COVID-19 crisis period. I find that, everything else equal, firms headquartered in the high trust states, ex-ante, perform better during the crisis period. Investors value more to firms from high trust states because they believe in getting more transparent and timely information from these firms. The association is stronger for firms of the more affected sectors, COVID-19 industries. Moreover, the observed positive association is exclusive to the crisis period, meaning social trust plays a significant role in firms’ performance when the aggregate mistrust becomes prominent. I also investigate how firms’ stock prices react to the announcement of the macroeconomic measures designed to support the firms. I hypothesize that firms headquartered in the high trust states benefit less from the announcements because these firms can enjoy affordable financing from other sources along with the Fed facilities. Consistent with the hypothesis, I find that the announcement day returns are higher for firms from the low trust society. The results further show that social trust does not associate with firms’ post-intervention performance when the overall market performs better. All the results provide robust evidence that social trust is important to explain firms’ performance, especially when the overall market is in crisis. The study is the very preliminary analysis of the impact of the Fed facilities (PMCCF, SMCCF); thus, the long-term effects of the facilities and the sustainability of the event date abnormal returns are subject to future research. Other reasons (such as financial flexibility, credit accessibility, and so on) of event date performance differentials are worthwhile to examine.

Footnotes

On March 23, the Fed announced two facilities — Primary Market Corporate Credit Facilities (PMCCF) and Secondary Market corporate Credit Facilities (SMCCF). The brief description of the facilities is presented in Section 2.

OECD (2020) determines several industries that are more affected during the pandemic, such as Entertainment, Construction, Automobiles and trucks, Aircraft, Ships, Personal Services, Business Services, Transportation, Wholesale, Retail, and Restaurants, hotels, and motels.

The S&P 500 index fall by 33% from February 19, 2020 till March 23, 2020. On February 19, 2020, S&P closing value was 3,386.15, while the index plunged to 2,237.40 on March 23, 2020 right before the Fed announcement. The market responded by 9.36% spike on the following day of the announcements.

Russell 3000 is the largest 3000 publicly traded firms incorporated in US represents almost 97% of the total market capitalization.

I compute four abnormal returns: CAPM-adjusted cumulative abnormal returns (), FF three-factor adjusted cumulative abnormal returns (), CAPM adjusted buy-hold abnormal returns (), and FF three-factor adjusted buy-hold abnormal returns ().

See “Federal Reserve announces extensive new measures to support the economy”, press release, March 23, 2020.

This survey asks a large collection of questionnaires to a random sample of US citizens from nine regions. The composition of the nine regions are presented in Table A.1 briefly.

The latest survey is conducted in 2018. I use the survey of 2016 for two reasons. First, the number of responses for the question to measure trust is higher in 2016 survey that may provide us more reliable trust measure. Second, I find that 33.4% of the respondents responses that they trust most of the people from 2016 survey, while LST (2017) find the percentage of 34% from 2006 survey data. Thus, social trust is very sticky measure with little time variation. Moreover, Knack and Keefer (1997) suggest that the measure of regional trust is indeed a persistent feature. Thus, using the survey responses of 2016 does not vary a lot than survey of 2018.

Before-Fed intervention period started from January 02, 2020 to March 23, 2020 and After-Fed intervention day ranges the day after the announcement date till May 30, 2020.

I control industry dummies because some industry may affect differently from the other industries.

I also analyze using and and find the result robust but do not report for brevity.

I cannot take the post-crisis sample as the impact of the COVID-19 does not finish yet when I complete the study.

I take month fixed effects in the regressions. The result is robust if I take day fixed effect instead of month fixed effect. Moreover, I take industry fixed effects rather firm fixed effects because the variable of interest, , does not have any time variation unless firms shift the location, which is a very rare event. Hence, I take industry fixed effect rather than firm level fixed effects.

Appendix.

See Table A.1

References

- Al-Awadhi A.M., Al-Saifi K., Al-Awadhi A., Alhamadi S. Death and contagious infectious diseases: Impact of the COVID-19 virus on stock market returns. J. Behav. Exp. Finance. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jbef.2020.100326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albulescu C. 2020. Coronavirus and financial volatility: 40 days of fasting and fear. arXiv preprint arXiv:2003.04005. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida H., Campello M., Laranjeira B., Weisbenner S. National Bureau of Economic Research; 2009. Corporate Debt Maturity and the Real Effects of the 2007 Credit Crisis (No. W14990) [Google Scholar]

- Arrow K.J. Philosophy & Public Affairs. 1972. Gifts and exchanges; pp. 343–362. [Google Scholar]

- Berglund N., Kang T. Does social trust matter in financial reporting? Evidence from audit pricing. J. Accounting Res. 2013;12:119–121. [Google Scholar]

- Campello M., Graham J.R., Harvey C.R. The real effects of financial constraints: Evidence from a financial crisis. J. Financ. Econ. 2010;97(3):470–487. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman J.S. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.; Cambridge, MA: 1990. Foundations of Social Theory. [Google Scholar]

- Duarte J., Siegel S., Young L. Trust and credit: The role of appearance in peer-to-peer lending. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2012;25(8):2455–2484. [Google Scholar]

- Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System . 2020. Federal reserve announces extensive new measures to support the economy [press release] Retrieved from https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/pressreleases/monetary20200323b.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Fu F. Idiosyncratic risk and the cross-section of expected stock returns. J. Financ. Econ. 2009;91(1):24–37. [Google Scholar]

- Georgarakos D., Pasini G. Trust, sociability, and stock market participation. Rev. Finance. 2011;15(4):693–725. [Google Scholar]

- Goyal A., Santa-Clara P. Idiosyncratic risk matters! J. Finance. 2003;58(3):975–1007. [Google Scholar]

- Guiso L., Sapienza P., Zingales L. The role of social capital in financial development. Amer. Econ. Rev. 2004;94(3):526–556. [Google Scholar]

- Guiso L., Sapienza P., Zingales L. Trusting the stock market. J. Finance. 2008;63(6):2557–2600. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta A., Raman K., Shang C. Social capital and the cost of equity. J. Bank. Financ. 2018;87:102–117. [Google Scholar]

- Habib A., Bhuiyan B.U., Islam A. Financial distress, earnings management and market pricing of accruals during the global financial crisis. Manag. Finance. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- Haroon O., Rizvi S.A.R. COVID-19: Media coverage and financial markets behavior—A sectoral inquiry. J. Behav. Exp. Finance. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jbef.2020.100343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasan I., Hoi C.K., Wu Q., Zhang H. Social capital and debt contracting: Evidence from bank loans and public bonds. J. Financ. Quant. Anal. 2017;52(3):1017–1047. [Google Scholar]

- Jegadeesh N., Titman S. Returns to buying winners and selling losers: Implications for stock market efficiency. J. Finance. 1993;48(1):65–91. [Google Scholar]

- Knack S., Keefer P. Does social capital have an economic payoff? A cross-country investigation. Q. J. Econ. 1997;112(4):1251–1288. [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Wang S.S., Wang X. Trust and stock price crash risk: Evidence from China. J. Bank. Financ. 2017;76:74–91. [Google Scholar]

- Lins K.V., Servaes H., Tamayo A. Social capital, trust, and firm performance: The value of corporate social responsibility during the financial crisis. J. Finance. 2017;72(4):1785–1824. [Google Scholar]

- Liu H., Manzoor A., Wang C., Zhang L., Manzoor Z. The COVID-19 outbreak and affected countries stock markets response. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020;17(8):2800. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17082800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazumder S., Rao R. 2020. Social trust and capital structure: Evidence from international data. [Google Scholar]

- Meng Y., Yin C. Trust and the cost of debt financing. J. Int. Financ. Markets, Inst. Money. 2019;59:58–73. [Google Scholar]

- Merton R.C. 1987. A simple model of capital market equilibrium with incomplete information. [Google Scholar]

- OECD R.C. Evaluating the Initial Impact of COVID-19 Containment Measures on Economic Activity: Staff Report. 2020. https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/en/. (Accessed 20 June 2020) [Google Scholar]

- Pevzner M., Xie F., Xin X. When firms talk, do investors listen? The role of trust in stock market reactions to corporate earnings announcements. J. Financ. Econ. 2015;117(1):190–223. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam R. The American Prospect 13(Spring), Vol. 4. 1993. The prosperous community: Social capital and public life. Available online: http://www.prospect.org/print/vol/13. (Accessed 7 April 2003) [Google Scholar]

- Ramelli S., Wagner A.F. 2020. Feverish stock price reactions to covid-19. [Google Scholar]

- Reich Robert. Government Needs To Rebuild Trust in the Markets: U.S. News and World Report September 16 2008. 2008. Available at http://www.usnews.com/opinion/articles/2008/09/16/robert-reich-government-needs-to-rebuild-trust-in-the-markets (Accessed 30 April 2020) [Google Scholar]

- Stiglitz Joseph E. Economics Opinion, the Guardian, September 16 2008. 2008. The fruit of hypocrisy. Available at https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2008/sep/16/economics.wallstreet. (Accessed April May 30, 2020) [Google Scholar]

- Wadhams Nick. Bloomberg Businessweek, May 17, 2020. 2020. Pandemic shatters world order, sowing anger and mistrust in its wake. Available at https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-05-17/pandemic-shatters-world-order-sowing-anger-and-mistrust-in-wake (Accessed 30 May 2020) [Google Scholar]

- Zaremba A., Kizys R., Aharon D.Y., Demir E. Infected markets: Novel coronavirus, government interventions, and stock return volatility around the globe. Finance Res. Lett. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.frl.2020.101597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D., Hu M., Ji Q. Financial markets under the global pandemic of COVID-19. Finance Res. Lett. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.frl.2020.101528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]