Abstract

BACKGROUND

The outbreak of COVID-19 has become pandemic. Pediatric population has been less studied than adult population and prompt diagnosis is challenging due to asymptomatic or mild episodes. Radiology is an important complement to clinical and epidemiological features.

OBJECTIVE

To establish the most common CXR patterns in children with COVID-19, evaluate interobserver correlation and to discuss the role of imaging techniques in the management of children.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Forty-four patients between 0 and 16 years of age with confirmed SARS-Cov-2 infection and CXR were selected. Two paediatric radiologists independently evaluated the images and assessed the type of abnormality, distribution and evolution when available.

RESULTS

Median age was 79.8 months (ranging from 2 weeks to 16 years of age). Fever was the most common symptom (43.5 %). 90 % of CXR showed abnormalities. Peribronchial cuffing was the most common finding (86.3 %) followed by GGOs (50 %). In both cases central distribution was more common than peripheral. Consolidations accounted for 18.1 %. Normal CXR, pleural effusion, and altered cardiomediastinal contour were the least common.

CONCLUSION

The vast majority of CXR showed abnormalities in children with COVID-19. However, findings are nonspecific. Interobserver correlation was good in describing consolidations, normal x-rays and GGOs. Imaging techniques have a role in the management of children with known or suspected COVID-19, especially in those with moderate or severe symptoms or with underlying risk factors.

Abbreviations: SARS, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome; MERS, Middle East Respiratory Syndrome; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; WHO, World Health Organization; ICTV, international committee on taxonomy of viruses; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; CXR, chest-x-ray(s); CT, computed tomography; GGOs, ground-glass opacities; IUC, Intensive Unit Care

Keywords: COVID 19, SARS-CoV-2, Outbreak, Pneumonia, Paediatric, Radiology, Thoracic imaging, Paediatric imaging

1. Introduction

A pneumonia of unknown cause detected in the city of Wuhan in Hubei province (China) was first reported to the World Health Organization (WHO) Office in China on 31st December 2019 [1]. A novel coronavirus, firstly named 2019-nCoV, was isolated from human airway epithelial cells [2]. On 11th February 2020, the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV), named this novel coronavirus "severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2″ (SARS-CoV-2) [3]. Afterwards, the WHO named the disease officially, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) [3,4]. Since then, it has become pandemic [1].

As shown in initial reports from Wuhan, a small number of children was affected with COVID 19. They often present with fever, cough and breathing difficulties, and in many cases gastrointestinal symptoms. Although children often have mild symptoms, they can be potential agents of transmission [5].

Chest computed tomography (CT) has become important in screening, diagnosis and follow up of patients with COVID-19 [6], and it adds prognostic information [7]. CT has shown high sensitivity rates (even higher than polymerase chain reaction test) and negative predictive values close to 99 %; although specificity and positive predictive values are low [8]. Chest x-rays (CXR) have been less studied. Findings are similar to those described on CT, however, sensitivity is lesser. This understudied field opens the door to consider a study to value CXR-findings in children with COVID-19. Additionally, as children are more sensitive to radiation, systematic use of CT is not recommended, making a difference in their radiological work-up compared to adults.

It is believed that CXR can be useful in clinical decision and management of children with suspected COVID-19 and for this purpose; it was intended to establish the most common CXR findings.

2. Materials and methods

This study took place in a reference tertiary paediatric hospital in Madrid (Spain). Forty-four patients from one day to sixteen years of age who tested positive on polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test for COVID-19 were detected from 13 March 2020 to 6 April 2020. Selection of patients for CXR was based on standard protocols (severity of symptoms or underlying risk factors) and not influenced by this study. All patients underwent a CXR in the emergency department before hospital admission, at the time of pharyngeal swab sample taking. CXR were acquired in the posteroanterior or anteroposterior projection when portable in bed. Radiological follow-up or further explorations such us CT was based on clinical criteria.

All images were retrospectively reviewed by two radiologists by consensus. One of them had more than 12 years of experience in paediatric radiology whilst the other was a novel paediatric radiologist with one year of experience.

Data regarding sex, age, respiratory symptoms (fever, cough and dyspnoea) and previous diseases was collected. Radiological features were assessed in terms of type of abnormality and distribution in the lung. Three main categories were created: peribronquial cuffing, ground-glass opacities (GGOs) and consolidations. Distribution was considered in terms of peripheral, central or diffuse. Central location was considered as involvement if the hiliar regions and peripheral when involvement was away from the hilum (middle third of the lung and subpleural space when visible). Additional considered features were pleural effusion and the cardiomediastinal contour. Parental or legal guardian informed consent was obtained in every case. As an outbreak situation was being faced and the study did not modify established protocols in the management of children, oral consent was obtained before performing CXR.

2.1. Secondary objective

To evaluate interobserver correlation.

2.2. Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed by the appropriate department of the hospital. Descriptive analysis for each variable was performed using frequency tables. Age-subgroups analysis was done based on crosstabulation tables and Chi-square test and correlation was assessed using crosstabulation tables and Cohen’s Kappa coefficient.

3. Results

A total amount of one hundred and twenty-one CXR were performed in children with fever or respiratory symptoms. Forty-four patients tested positive to PCR for COVID-19, and therefore they were included in this study; 29 male (65.9 %) and 15 female (34.1 %). The median age was 79.8 months, ranging from 2 weeks up to 16 years of age. Distribution by age group showed mild tendency to bimodal distribution. 14 out of 44 children were 10 years or older (31.8 %) and 13 out of 44 under 1 year of age (29.5 %). All patients with negative PCR (77) were excluded.

Fever was detected in 43.5 % (19/44), cough in 34.1 % (15/44), and difficulty respiratory in 15.9 % (7/44). More than half of the patients (23/44; 52.3 %) suffered from previous pathology: cardiomyopathies (13.6 %), nephropathies (9%), history of prematurity (6.8 %), liver and renal transplantation (4.5 %), and neoplasm (4.5 %).

3.1. Radiological findings

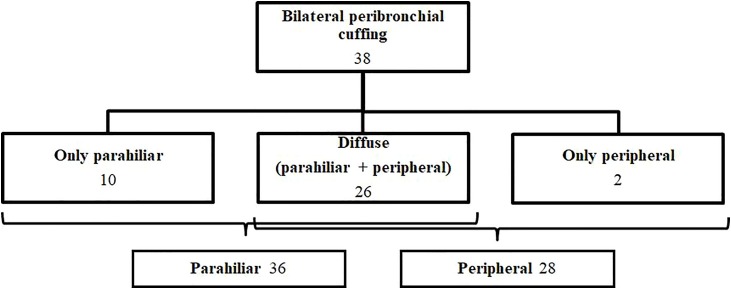

Radiological patterns are summarized in Table 1 . Among 44 children, 38 were positive for peribronchial cuffing (86.3 %), all of them bilateral (Fig. 1 ). Location was predominantly central, seen in 36 patients (81.8 %) and it was the only finding in 10 patients (22.7 %). Involvement of the peripheral space was seen in 28 patients (63.3 %). Diffuse peribronchial cuffing affecting both, centre and periphery of the lungs, was seen in 26 patients (59 %) (Fig. 2 ).

Table 1.

Radiological patterns are summarized in Table1.

| Feature | Number | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peribronchial thickening | Total | 38 | 863 |

| Parahiliar | 36 | 818 | |

| Subpleural | 28 | 633 | |

| Ground-glass opacities | Total | 22 | 50 |

| Central | 18 | 409 | |

| Subpleural | 14 | 318 | |

| Consolidation | 8 | 181 | |

| Normal x-ray | 4 | 9,1 | |

| Pleural effusion | 4 | 9,1 | |

| Mediastinal widening | 2 | 4,5 | |

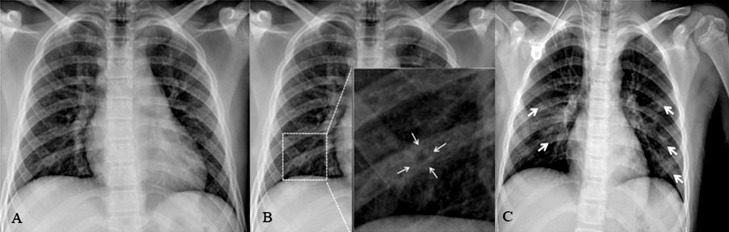

Fig. 1.

Two different children with COVID-19. A and B a fourteen-year-old boy with fever and cough. A. Chest x-ray shows diffuse areas of peri-bronchial thickening. There is slight predominance in the parahiliar regions. B. Magnified right lower lobe shows dense cuff surrounding an aerated bronchus. C. corresponds to a ten-year-old girl with patchy bilateral ground-glass opacities (arrows).

Fig. 2.

Distribution of peribronchial cuffing in the lungs.

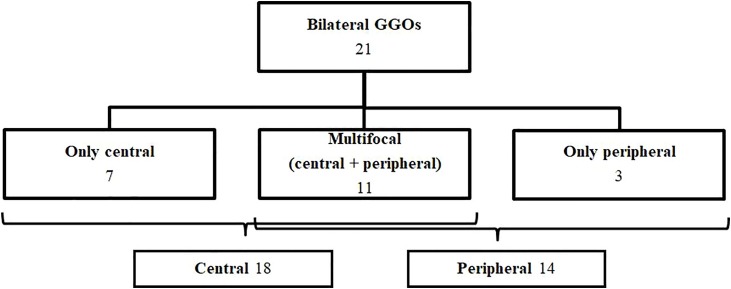

22 children were positive for GGOs (50 %). One was unilateral (2.27 %); while 21 were bilateral (47.7 %). Among bilateral, central GGO were depicted in 18 (409%) and peripheral in 14 (31.8 %). Multifocal opacities represented 25 % of the sample (11/44). Only central (7/44, 15.9 %) or only peripheral GGOs (3/44, 6.8 %) were less common (Fig. 3 ).

Fig. 3.

Distribution of GGOs in the lungs.

Consolidation was seen in 18.2 %. Unilateral consolidation accounted for 11.3 % and bilateral for 6.8 %. When unilateral, left lower lobe (6.8 %) and right upper lobe (4.5%) were affected. When bilateral, distribution was symmetric and there was slightly predilection for upper zones.

Less common findings included pleural effusion (9.1 %) and mediastinal widening (4.5 %). Four of all of the children had no findings in the x-ray (13.6 %).

Data regarding inter-observer agreement is depicted in Table 2 .

Table 2.

Data regarding inter-observer agreement is depicted in Table 2:

| Variable | Cohen's kappa coefficient (κ) | Percent | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peri-bronchial thickening | Central | 0.373 | (6 + 27)/44 | 75 % |

| Subpleural | 0.358 | (14 + 15)/44 | 65.9 % | |

| GGOs | Central | 0.325 | (25 + 6)/44 | 70.4% |

| Subpleural | 0.596 | (25 + 11)/44 | 81.8 % | |

| Consolidation | 0.847 | (35 + 7)/44 | 95.4% | |

| Nomral x-ray | 0.551 | (37 + 3)/44 | 90.9% | |

| Pleural effusion | 0.377 | (40 + 1)/44 | 93.1% | |

| Altered mediastinal contour | −0.31 | (41 + 0)/44 | 93.1% | |

| Central distribution | 0.349 | (5 + 28)/44 | 75 % | |

| Peripheral distribution | 0.789 | (13 + 27)/44 | 90.9% | |

4. Evolution

Follow-up radiographs were obtained depending on clinical evolution. Most of the children recovered rapidly without complications (33/44; 75 %), and underwent one CXR before discharge, which showed complete resolution of previous involvement. Persistence or worsening of symptoms was observed in 15.9 % of the patients (7/44) who also showed exacerbation in radiological features and appearance of new consolidations. Unfavourable outcomes were more frequent when initial radiograph showed bilateral involvement, diffuse affectation and combination of peribronchial cuffing and GGOs. The periodicity of the follow up was based on severity of symptoms: almost daily in the intensive unit care (IUC) and lower frequency (every two or three days) in the rest.

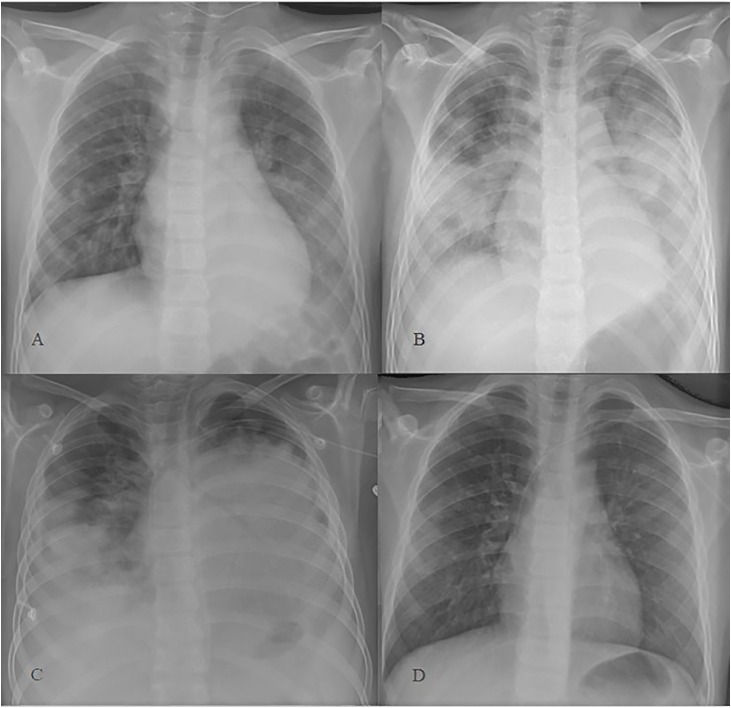

A ten-year-old male developed acute respiratory distress syndrome and was admitted to IUC and placed on ventilator due to respiratory failure (Fig. 4 ).

Fig. 4.

A. Baseline CXR in a ten-year-old boy with fever, cough, and dyspnoea. There were multifocal GGOs in both lungs and a consolidation in left inferior lobe. The consolidation is depicted as an increased retrocardiac density and loss of the silhouette of the diaphragm. B. Diffuse bilateral coalescent consolidations appeared 24 h after. No pleural effusion was seen on ultrasound. Findings were consistent with acute respiratory distress syndrome. C. In the follow up CXR 24 h later, bilateral progression was seen. D. 8 days after the initial radiograph most of the lung injury had already resolved.

CT was not performed systematically. Images were obtained only in two of the patients due to clinical deterioration. In fact, CT was not performed to assess evolution of the pneumonia, but to detect and characterize other complications.

One of the patients, a twelve-year-old healthy female, complained of abdominal pain 2 days after hospital admission. She underwent abdominal ultrasound, which showed wall-thickened bowel-loops. CT was performed to evaluate extension of the inflammatory changes and to rule out pneumoperitoneum or hollow viscus perforation.

The second patient was a six-year-old female with systemic sclerosis and severe pulmonary involvement. Initial clinical picture raised doubts between progression of the disease or superimposed COVID-19 infection. First PCR was negative. CT showed new bilateral consolidations and GGOs compared to previous. After lack of response to steroids and immunomodulatory drugs and clinical deterioration, bronchoscopy with transbronchial biopsy was performed. CT after the procedure showed pneumothorax, pneumomediastinum, interstitial emphysema and subcutaneous emphysema (presumably as complications of the procedure) (Fig. 5 ). Additionally, signs of acute pancreatitis and splenic infarctions were detected. A second PCR was positive. Pulmonary involvement and splenic infarctions were assumed to be related to COVID-19. Pancreatitis was thought to be idiopathic, drug-induced or ischemic in the onset of the viral infection. She was admitted to IUC and placed on ventilator due to respiratory failure. She finally died.

Fig. 5.

Six-year-old female with COVID-19 pneumonia. She had previous history of pulmonary involvement of systemic sclerosis. Coronal contrast-enhanced CT-scan (lung window) after bronchoscopy. Extensive pneumomediastinum, right basal pneumothorax and subcutaneous emphysema. Patchy bilateral subpleural GGOs and left lower lobe consolidation.

5. Discussion

As paediatric radiologists in a reference tertiary hospital for children’s diseases, we found the opportunity to study radiological manifestations of COVID-19 in a group of 44 patients who tested positive to PCR.

No significant differences were found between age groups; however, there was some predominance in children over 10 years of age and under 1 year of age. There is some controversy regarding age. Some authors have reported ages from 1.5 months to 7 years of age as most common among children [[9], [10], [11], [12]]. According to the largest epidemiologic survey, which mostly included adults, the age distribution is mainly 30–79 years (87 %) [13].

Most of the publications showed fever and cough as major symptoms in children [11,13]. Accordingly, in this study the most common symptom was fever (43.5 %). Abdominal symptoms were presented by two patients during hospital admission.

52.3 % of the patients in this study suffered from previous diseases, such as transplantation, prematurity, nephropathies, and neoplasm. Cardiomyopathies were the most common (13.6 %). Statistics regarding children with co-morbidities and COVID-19 were not found. As far as we know, in adults, SARS-CoV-2 infection is more common in individuals with comorbidities [5].

Sensitivity rates of CXR in adults vary from 25 % [14] to 69 % [15]. Sensitivity rates for CT–scans are higher. Yicheng Fang et all. reported that sensitivity of CT for COVID-19 infection was 98 % compared to PCR sensitivity of 71 % (p < .001) [16]. In paediatric population, radiological manifestations seem to be less marked. Most of the publications regarding children are based on CT and a significant number of them did not show abnormalities on initial studies [9,13,17].

In this study, abnormalities were found in 90 % of the baseline CXR. The most common findings were peribronchial cuffing (86.3 %) and GGOs (50 %). Peribronchial cuffing is defined as increased density around the walls of pulmonary bronchus. It is a nonspecific response of the bronchus, which can be seen in the onset of infectious and non-infectious diseases [18,19]. In addition, peribronchial cuffing is a common finding in other viral pneumonias such as H1N1 influenza [20], rhinoviruses, respiratory syncytial viruses, adenoviruses and other coronaviruses. Bilateral parahiliar peribronchial cuffing were observed as far as in 818% of the CXR in our study; however due to its low specificity, it should not be considered as a definitive sign for COVID-19. Involvement of the periphery of the lungs, which has been more associated with coronavirus 19 disease [6,21,22] and previous emergent coronavirus infection, like SARS and MERS [23], was seen in 63.3 %, especially in the onset of a diffuse pattern (59 %).

On the contrary, opacities detected close to visceral pleural surfaces and multifocal have been described as highly suspicious for COVID 19 [6,14]. Typical chest CT findings in children include unilateral or bilateral subpleural opacities [9,11,13]. Opacities are ground-glass in attenuation and therefore underdetected and underestimated in size in CXR when compared to CT [14,24]; however, they are still common in radiographs (33 %–56 %) [14,15]. Opacities were detected in up to 50 % of our CXR and 25 % manifested with the typical pattern of multifocal GGOs. These opacities are mostly rounded [6], irregular and small in size. Certain predilection for lower lobes has been described [15,22], however, this seems not be a constant finding [6]. Moreover, peripheral distribution in children may not be as common as in adults [25]. Our study highlighted that GGOs were more frequent in parahiliar regions (40.9 %) than in the periphery (31.8 %) of the lungs.

Combination of GGOs and peribronchial cuffing was common, more frequently diffuse and multifocal in distribution (22.7 %). These patterns are still nonspecific. It is hypothesised that it could be due to simultaneous infection of viral pathogens. Huanhuan Liu et al., described in their study that when superimposed with other pathogen infections, the pulmonary involvement was more severe and reported a case of simultaneous infection of respiratory syncytial virus and SARS-CoV-2 [25].

Consolidation as the main finding (47 %) in CXR was described by Ho Yuen Frank Wong et all [15]. Also, in children lung consolidation has been detected as an important finding [13]. In this study, consolidation was the initial finding in 18.2 % of the x-rays. Unilateral consolidations were constantly located in the left lower lobe or in the right upper lobe. Bilateral consolidations were less common, and when present, distribution was symmetric, more diffuse, and slightly predominant in the upper zones of the lungs. Wei Xia et all., described that consolidations with surrounding halo sign account for up to 50 % cases in children, and suggested that it should be considered as a typical sign in paediatric patients [11]. In this study the reverse halo sign was absent in all of the CXR.

Other radiological features such as crazy paving pattern or organizing pneumonia pattern, which have been suggested as highly suspicious for COVID-19, at least in adults [6,23], were not present in our study. Pleural effusion and distortion of the cardiomediastinal contour were uncommon, as other authors have shown [11,25].

Good agreement between radiologists was observed when describing consolidations, normal x-rays and peripheral and multifocal GGOs. The rest of the categories showed lower rates of concordance; possibly due to the fact that the interpretation of these features is more subjective, with less precise definitions. Moreover, findings such as peribronchial cuffing tend to be subtle and undefined, highly variable depending on the grade of inspiration of the CXR and generally better identified with experience.

5.1. Role of image techniques in paediatric population

The American College of Radiology (ACR) states that neither CXR nor chest CT should be used to screen for or as a first‐line test to diagnose COVID‐19. However, imaging studies play an important role [26].

CXR is not indicated for most paediatric patients with known or suspected COVID‐19 with mild clinical symptoms that do not require hospitalization; although CXR is usually indicated in neonates with fever and respiratory symptoms [26].

CXR should be performed in children with moderate or severe symptoms and in those with medical history and underlying risk factors, which probably will need hospital admission and close follow-up. In these patients, CXR are usually indicated to establish an imaging baseline and to assess for an alternative diagnosis [26]. In addition, positive signs in CXR will support the hospitalization or even repeating the swab sample if a first PCR is negative, as it raises suspicion for pneumonia. Additionally, it will be important in assessing evolution and treatment response. In our sample, evolution has shown to be worse when initial involvement was more extent (combination of peribronchial cuffing, GGOS and/or consolidation, bilateral and diffuse); therefore these children should be treated prompt and intensively.

On the contrary, when initial CXR was normal or involvement mild (unilateral, peribronchial cuffing as the only finding) ambulatory management was performed, avoiding radiological follow-up unless clinical worsening.

CT should not be performed systematically in children to avoid radiation exposure. It is useful to evaluate pulmonary and extrapulmonary complications or after invasive procedures. Some authors have suggested that indications should be limited to address a specific clinical question in the paediatric patients presenting with acute symptoms (ie, hypoxia, dyspnea, tachycardia), worrisome abnormal laboratory findings (such as an elevated D‐dimer), or to evaluate a patient demonstrating clinical deterioration or not responding as expected to supportive treatment [26].

Utilization of chest ultrasounds has not been evaluated in the current literature, and thus no specific recommendations have been provided. Chest ultrasounds were not systematically performed in where this study took place, as it is believed by the authors that it does not add information over CXR in known or suspected COVID-19, and increases risk of contagion due to the proximity of the radiologist to the patient. The main role of US is to evaluate the size and complexity of pleural effusions, which are a rare finding in paediatric COVID‐19 pneumonia [26].

6. Limitations

This study has some limitations: the small sample size and the diagnostic technique. CXR are less sensitive than other imaging techniques such as CT; therefore, several findings must have been underestimated. Selection bias was probably inherent to our study as far as a significant amount of children did already suffered from previous pathologies and probably were more symptomatic. However, the selection of the patients was based on clinical decisions in the emergency department and radiologist did not intercede in that decision. Finally, most of the publications regarding radiology and COVID-19 are based on CT-scans in adults, limiting the comparison between our results and the previously published ones.

7. Conclusion

This study demonstrated that most symptomatic children with COVID-19 disease show abnormalities in CXR. Findings are nonspecific, and therefore CXR cannot be used to screen for or as a first‐line diagnostic test. However, radiographs should be considered complementary tools in management of these patients. CT should be considered in patients with torpid evolution and in suspected complications, but not systematically. Agreement between observers was in general good.

Acknowledgements

No.

References

- 1.World Health Organization . 2020. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19). Events As They Happen.https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/events-as-they-happen [Google Scholar]

- 2.Na Zhu, Zhang Dingyu, Wang Wenling, Li Xingwang, Bo Yang, Song Jingdong, Zhao Xiang, Huang Baoying, Shi Weifeng, Roujian Lu, Niu Peihua, Zhan Faxian, et al. For the China novel coronavirus investigating and research team. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382(8):727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.International Committee on Taxonomy Viruses . 2020. Naming the 2019 Coronavirus.https://talk.ictvonline.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization . 2020. Naming the Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) and the Virus That Causes It.https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/technical-guidance/naming-the-coronavirus-disease-(covid-2019)-and-the-virus-that-causes-it [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kar SujitaKumar, Verma Nishant, Saxena ShailendraK. In: Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, Diagnosis and Therapeutics. 1st ed. Saxena ShailendraK., editor. Centre for Advanced Research King George’s Medical University; Lucknow, India: 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prokop M., van Everdingen W., van Rees Vellinga T., et al. CO-RADS: a categorical CT assessment scheme for patients suspected of having COVID-19-definition and evaluation. Radiology. 2020;296(2):E97–E104. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020201473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tabatabaei SeyedMohammadHossein, Talari Hamidreza, Moghaddas Fahimeh, Rajebi Hamid. Computed tomographic features and short-term prognosis of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pneumonia: a single-center study from Kashan, Iran. Radiology. Cardiothoracic Imaging. 2020;2(2) doi: 10.1148/ryct.2020200130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim Hyungjin, Hong Hyunsook, Yoon Soon Ho. Diagnostic performance of CT and reverse e-Polymerase chain reaction for coronavirus disease 2019: a meta-analysis. Radiology. 2020 doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020201343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li W., Cui H., Li K., Fang Y., Li S. Chest computed tomography in children with COVID-19 respiratory infection. Pediatr. Radiol. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s00247-020-04656-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu Weiyong, et al. Detection of Covid-19 in children in early January 2020 in Wuhan, China. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:1370–1371. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2003717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xia W., Shao J., Guo Y., Peng X., Li Z., Hu D. Clinical and CT features in pediatric patients with COVID-19 infection: different points from adults. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2020;55(5):1169–1174. doi: 10.1002/ppul.24718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tan Ypin, Tan B.yu, Pan J., Wu J., Zeng S.zhen, Wei H.yan. Epidemiologic and clinical characteristics of 10 children with coronavirus disease 2019 in Changsha, China. J. Clin. Virol. 2020;127 doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104353. April. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chang T.-H., et al. Clinical characteristics and diagnostic challenges of pediatric COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2020.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Choi Hyewon, Qi Xiaolong, Yoon Soon Ho, Park SangJoon, Lee KyungHee, Kim Jin Yong, Lee Young Kyung, Ko Hongseok, Ki Hwan Kim, Park Chang Min, Kim Yun-Hyeon, Lei Junqiang, Hong JungHee, Kim Hyungjin, Hwang EuiJin, Yoo SeungJin, Gang Nam Ju, Lee Chang Hyun, Goo Jin Mo. Extension of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on chest CT and implications for chest radiograph interpretation. Radiology: Cardiothoracic Imaging. 2020;2(2):e204001. doi: 10.1148/ryct.2020200107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wong H.Y.F., Lam H.Y.S., Fong A.H., et al. Frequency and distribution of chest radiographic findings in patients positive for COVID-19. Radiology. 2020;296(2):E72–E78. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020201160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fang Yicheng, Zhang Huangqi, Xie Jicheng, Lin Minjie, Ying Lingjun, Pang Peipei, Ji Wenbin. Sensitivity of chest CT for COVID-19: comparison to RT-PCR. Radiology. 2020 doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200432. Feb 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rujittika Mungmunpuntipantip, Viroj Wiwanitkit Chest computed tomography in children with COVID-19. Pediatric Radiology. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s00247-020-04676-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bramson Robert T., Thorne Griscom N., Cleveland Robert H. Interpretation of chest radiographs in infants with cough and fever. Radiology. 2005 doi: 10.1148/radiol.2361041278. Jul 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Conway Don, Richard Johnson The nature and significance of peribronchial cuffing in pulmonary edema. Radiology. 1977 doi: 10.1148/125.3.577. Dec 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Patel I.K.A.R.A., Joshi S.K. H1N1 influenza: characterization of initial chest radiographic findings and prognostic value of serial chest radiographs. Radiol. Infect. Dis. 2016;3(4):157–164. doi: 10.1016/j.jrid.2016.11.005. U. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Piero Boraschi COVID-19 pulmonary involvement: is really an interstitial pneumonia? Letters to the editor. Acad. Radiol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2020.04.010. Apr 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Caruso Damiano, et al. Chest CT features of COVID-19 in Rome, Italy. Radiology. 2020 doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020201237. Apr 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yu Minhua, Xu Dan, Lan Lan., Tu Mengqi, Liao Rufang, Cai Shuhan, Cao Yiyuan, Xu Liying, Liao Meiyan, Zhang Xiaochun, Xiao Shu-Yuan, Li Yirong, Haibo Xu. Thin-section Chest CT Imaging of Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pneumonia: Comparison Between Patients with Mild and Severe Disease. Radiology: Cardiothoracic Imaging. 2020;2(2):e200126. doi: 10.1148/ryct.2020200126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kong Weifang, Agarwal Prachi P. Chest imaging appearance of COVID-19 infection. Radiology: Cardiothoracic Imaging. 2020 doi: 10.1148/ryct.2020200028. Feb 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu Huanhuan, Liu Fang, Li Jinning, Zhang Tingting, Wang Dengbin, Lan Weishun. Clinical and CT imaging features of the COVID-19 pneumonia: Focus on pregnant women and child. J. Infect. 2020;80:e7–e13. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Foust DO Alexandra M., McAdam Alexander J., Chu Winnie C., Pilar Garcia‐Peña F.R.C.R., Phillips Grace S., Plut Domen, Lee Edward Y. Practical guide for pediatric pulmonologists on imaging management of pediatric patients with COVID‐19. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2020:1–12. doi: 10.1002/ppul.24870. 28 May 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]