Abstract

Background

Men who have sex with men (MSM) and transgender women (TGW) are disproportionately impacted by HIV and may face barriers to HIV status disclosure with negative ramifications for HIV prevention and care. We evaluated HIV status disclosure to sexual partners, HIV treatment outcomes, and stigma patterns of MSM and TGW in Abuja and Lagos, Nigeria.

Methods

Previously-diagnosed MSM and TGW living with HIV who enrolled in the TRUST/RV368 cohort from March 2013 to August 2018 were asked, “Have you told your (male/female) sexual partners (MSP/FSP) that you are living with HIV?” In separate analyses, robust Poisson regression models were used to estimate risk ratios (RRs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) for characteristics associated with HIV status disclosure to MSP and FSP. Self-reported stigma indicators were compared between groups.

Results

Of 493 participants living with HIV, 153 (31.0%) had disclosed their HIV status to some or all MSP since being diagnosed. Among 222 with FSP, 34 (15.3%) had disclosed to some or all FSP. Factors independently associated with disclosure to MSP included living in Lagos (RR 1.58 [95% CI 1.14–2.20]) and having viral load < 50 copies/mL (RR 1.67 [95% CI 1.24–2.25]). Disclosure to FSP was more common among participants who were working in entertainment industries (RR 6.25 [95% CI 1.06–36.84]) or as drivers/laborers (RR 6.66 [95% CI 1.10–40.36], as compared to unemployed) and also among those married/cohabiting (RR 3.95 [95% CI 1.97–7.91], as compared to single) and prescribed ART (RR 2.27 [95% CI 1.07–4.83]). No differences in self-reported stigma indicators were observed by disclosure status to MSP but disclosure to FSP was associated with a lower likelihood of ever having been assaulted (26.5% versus 45.2%, p = 0.042).

Conclusions

HIV status disclosure to sexual partners was uncommon among Nigerian MSM and TGW living with HIV but was associated with improved HIV care outcomes. Disclosure was not associated with substantially increased experiences of stigma. Strategies to encourage HIV status disclosure may improve HIV management outcomes in these highly-marginalized populations with a high burden of HIV infection.

Keywords: HIV, Disclosure, Sexual and gender minorities, Nigeria, Social stigma, HIV management outcomes

Background

Sub-Saharan Africa is home to about 25.7 million people living with HIV (PLWH) and over two-thirds of the global burden of HIV incidence is in this region [1]. Nigeria is the most populous African country and has the second largest population of PLWH, accounting for 10% of new infections and 14% of AIDS-related deaths worldwide every year [2, 3]. HIV disproportionately impacts men who have sex with men (MSM) and transgender women (TGW) as compared to other reproductive aged adults [1]. Nigerian national estimates suggest that HIV prevalence among MSM is about 23%, which is 4–10 times higher than the general population [4, 5]. We have previously reported HIV prevalence of 44–66% among MSM and TGW receiving care at community-based health centers in Abuja and Lagos, Nigeria [6].

The disproportionate impact of HIV can be partly explained by stigmatization, discrimination, and homophobia that impede engagement of Nigerian MSM and TGW in HIV prevention and care services [7]. These factors perpetuate the HIV epidemic and drive some individuals to maintain both public heterosexual relationships and private same-sex ones [8]. Nigerian MSM and TGW rarely disclose their same-sex sexual practices to healthcare providers and family members, creating barriers to receipt of appropriate healthcare services such as HIV testing and anatomically appropriate screening for other sexually transmitted infections [9]. Stigma that is deep-rooted within Nigerian culture was codified into law in 2014, when Nigeria passed the Same Sex Marriage Prohibition Act, which prohibits marriage or civil union by persons of the same sex, solemnization of same sex marriage in places of worship, direct or indirect public displays of affection by same-sex couples and registration of homosexual clubs and societies [10–13]. The passage of this Act was supported by leaders of both major religions in Nigeria —Christianity and Islam [14]. Studies from other African countries have linked negative religious perspectives of same-sex sexual practices to increased stress and stigmatization [15, 16]. MSM and TGW who are living with HIV are subject to compounded and intersectional stigma due to both same-sex sexual practices and HIV [17–20].

Disclosure of HIV status may expose PLWH to societal rejection, stigma, persecution, and discrimination [17]. Among Nigerian cisgender women, risk of abandonment or separation and feelings of shame, worry and fear have been identified as barriers to HIV status disclosure in one prior study [21]. The paradox is that disclosure of HIV status offers potential individual and public health benefits. Disclosure can enhance adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART), create social support, lessen anxiety, enhance partners’ HIV testing, facilitate engagement in care, and reduce condomless sex [22–26]. Disclosure to sexual partners enables informed discussion and decision-making surrounding the use of HIV prevention technologies such as condoms, pre-exposure prophylaxis, and treatment as prevention [27]. In a previous study of predominantly heterosexual Nigerian men and women living with HIV, about three-quarters reported that their sexual partners responded with support, understanding, or kindness upon HIV status disclosure [28]. Studies in other populations have found HIV status disclosure to be facilitated by factors such as ethical obligations or feelings of guilt, opportunities for romantic relationships, open bi-directional communications between sexual partners, support for disclosure provided by healthcare workers, and de-stigmatizing community education programs [29–32].

Understanding HIV status disclosure practices among Nigerian MSM and TGW could inform interventions to optimize delivery of HIV prevention and treatment services to this marginalized population with a high burden of HIV. Among Nigerian MSM and TGW living with HIV, we characterized HIV status disclosure patterns to sexual partners and evaluated downstream effects on HIV management outcomes and stigma indicators. We hypothesized that HIV status disclosure would be associated with both improved HIV management outcomes and potentially increased stigma.

Methods

Study population

The TRUST/RV368 cohort is a prospective observational study of MSM and TGW engaged in community-based HIV prevention and treatment programs in Abuja and Lagos, Nigeria. Recruitment utilized respondent-driven sampling (RDS), in which 12 “seed” participants were identified through local non-governmental organizations and key opinion leaders to represent diverse demographic and socioeconomic characteristics. Each “seed” referred up to three potential participants from their social networks in the MSM and TGW communities [33, 34]. Potential participants followed instructions on their referral coupons to present to the site for individualized study briefings prior to enrollment. Each enrolled participant could similarly refer up to three additional participants. To be enrolled, prospective participants had to present a valid RDS recruitment coupon indicating referral from a current study participant. Inclusion criteria for enrollment also included male sex at birth; age of at least 16 years in Abuja or 18 years in Lagos (reflecting differences in local IRB guidance); and self-reported insertive or receptive anal sex with a male partner in the last year. Compensation was provided for both participation in study visits (Naira 2000–3400 [approximately US$6–11] depending on visit) and for successful referrals (Naira 1500 [approximately US$5]).

These analyses included MSM and TGW who enrolled from March 2013 to August 2018, were previously known to be living with HIV, and answered the survey question about HIV status disclosure to male sexual partners.

Data collection

Data for these cross-sectional analyses were collected at enrollment into the TRUST/RV368 cohort with evaluations spread across two visits approximately 2 weeks apart. Participant demographics (age, gender identity, sexual orientation, education level, occupation, and marital status), perceptions and experiences of stigma, and sexual behaviors were evaluated using questionnaires developed specifically for this this study (Supplementary Files 1–2) that were administered during a face-to-face interview with a specially-trained staff member lasting approximately 1–2 h at each visit [19]. Participants were asked up to two questions about HIV status disclosure(s) since becoming aware that they were living with HIV. First, all participants were asked, “Have you told your male sexual partners (MSP) that you are living with HIV?” Participants answered “yes, all male sexual partners”, “some but not all male sexual partners”, or “no, none”. If a participant reported female sexual partners (FSP), the participant was also asked, “Have you told your female sexual partners that you are living with HIV?” and provided similar answer choices. For these analyses, disclosure was dichotomized as disclosure to some/all partners or none. Perceived and experienced stigma were assessed using a variety of self-reported indicators including lifetime experience of fear of accessing healthcare services, avoidance of healthcare, denial of healthcare, verbal harassment, assault, and forced sex due to same-sex sexual practices.

HIV status was confirmed using a parallel algorithm of rapid tests with Determine® (Alere, Waltham, MA, USA) and Uni-gold® (Trinity Biotech, Co-Wicklow, Ireland) kits plus, if needed, a tie-breaker STAT-PAK (Chembio, NY, USA) kit. HIV viral load was quantified using the COBAS TaqMan HIV-1 Test (Roche Molecular Diagnostics, Pleasanton, CA). CD4 count was estimated using the Partec CyFlow Counter (Sysmex, Lincolnshire, IL). A study clinician reviewed existing medical records and took a detailed medical history from each participant, including a chronicle of any prior ART use.

Statistical analyses

All participants included in these analyses reported MSP and were stratified based on whether or not they reported disclosing their HIV status to MSP. Among participants who reported FSP, stratification was also performed based on self-reported disclosure of HIV status to FSP. Variables were pre-selected based on review of prior literature about disclosure patterns. Categorical variables of interest were compared between these groups using Pearson’s Chi-square test or, in cases with small cell sizes, the exact Chi-square test. In separate analyses by sexual partner type, unadjusted and adjusted robust Poisson regression models were used to estimate relative risks (RRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for pre-specified factors potentially associated with HIV status disclosure [35]. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.04 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Study population

A total of 2737 participants were enrolled. Of these, 984 were living with HIV, 529 knew their HIV status prior to enrollment, and 493 answered the question about disclosure to MSP. Of these, 222 also reported FSP, all of whom answered the question about disclosure to FSP. The median age of participants in these analyses was 25 (interquartile range [IQR] 22–29) years. Only 153 of 493 (31.0%) disclosed their HIV status to some or all MSP and 34 of 222 who reported FSP (15.3%) disclosed to some or all FSP (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of previously-diagnosed Nigerian men who have sex with men and transgender women living with HIV

| Characteristics | Disclosed to Male Sexual Partners | P | Disclosed to Female Sexual Partners | P* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None (n = 340) |

Some/All (n = 153) |

None (n = 188) |

Some/All (n = 34) |

|||

| Age | ||||||

| ≤ 21 years | 59 (70.2) | 25 (29.8) | 0.700 | 20 (87.0) | 3 (13.0) | < 0.001 |

| 22–30 years | 229 (69.6) | 100 (30.4) | 135 (90.6) | 14 (9.4) | ||

| > 30 years | 52 (65.0) | 28 (35.0) | 33 (66.0) | 17 (34.0) | ||

| Gender Identity | ||||||

| Cisgender Man | 249 (67.3) | 121 (32.7) | 0.310 | 155 (85.6) | 26 (14.4) | 0.724 |

| Transgender Woman | 49 (76.6) | 15 (23.4) | 14 (77.8) | 4 (22.2) | ||

| Other/Unknown | 42 (71.2) | 17 (28.8) | 19 (82.6) | 4 (17.4) | ||

| Sexual Orientation | ||||||

| Gay/Homosexual | 110 (67.1) | 54 (32.9) | 0.794* | 10 (76.9) | 3 (23.1) | 0.743 |

| Bisexual | 228 (69.9) | 98 (30.1) | 177 (85.1) | 31 (14.9) | ||

| Other/Unknown | 2 (66.7) | 1 (33.3) | 1 (100) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Education Level | ||||||

| Junior Secondary or Less | 16 (55.2) | 13 (44.8) | 0.083* | 11 (78.6) | 3 (21.4) | 0.890 |

| Senior Secondary | 187 (73.6) | 67 (26.4) | 95 (84.8) | 17 (15.2) | ||

| Higher than Senior Secondary | 134 (65.4) | 71 (34.6) | 81 (85.3) | 14 (14.7) | ||

| Unknown | 3 (60.0) | 2 (40.0) | 1 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Occupation | ||||||

| Unemployed | 50 (69.4) | 22 (30.6) | 0.587 | 24 (96.0) | 1 (4.0) | 0.122 |

| Student | 48 (75.0) | 16 (25.0) | 26 (96.3) | 1 (3.7) | ||

| Professional/Self-Employed | 40 (64.5) | 22 (35.5) | 25 (86.2) | 4 (13.8) | ||

| Entertainment/Hospitality | 32 (78.0) | 9 (22.0) | 13 (72.2) | 5 (27.8) | ||

| Driver/Laborer | 6 (66.7) | 3 (33.3) | 5 (83.3) | 1 (16.7) | ||

| Other/Unknown | 164 (66.9) | 81 (33.1) | 95 (81.2) | 22 (18.8) | ||

| Marital Status | ||||||

| Single/Never Married | 306 (70.7) | 127 (29.3) | 0.062 | 169 (90.4) | 18 (9.6) | < 0.001 |

| Married/Cohabiting | 23 (60.5) | 15 (39.5) | 12 (46.2) | 14 (53.8) | ||

| Divorced/Widowed/Other | 11 (50.0) | 11 (50.0) | 7 (77.8) | 2 (22.2) | ||

| Site | ||||||

| Abuja | 210 (70.9) | 86 (29.1) | 0.244 | 127 (82.5) | 27 (17.5) | 0.225 |

| Lagos | 130 (66.0) | 67 (34.0) | 61 (89.7) | 7 (10.3) | ||

All data are presented as n (%). Comparisons were made between groups using Pearson’s Chi-square test or, if indicated by an asterisk (*), exact Chi-square test. Statistically significant p-values (p ≤ 0.05) are in bold

Disclosure patterns

Among participants who reported FSP, those who disclosed their HIV status to MSP were more likely to also disclose to FSP as compared to those who did not disclose to MSP (25.4% versus 11.7%, p = 0.012). Stated another way, participants who disclosed their HIV status to FSP were more likely to also disclose to MSP as compared to those who did not disclose to FSP (44.1% versus 23.4%, p = 0.012). A total of 15 participants disclosed to both MSP and FSP.

Participants who disclosed their HIV status to MSP were more likely to disclose to healthcare providers (88.9% versus 76.2%, p = 0.001). However, the proportion who disclosed to healthcare providers did not differ significantly between participants who did and did not disclose to FSP (82.4% versus 77.1%, p = 0.499).

HIV care cascade

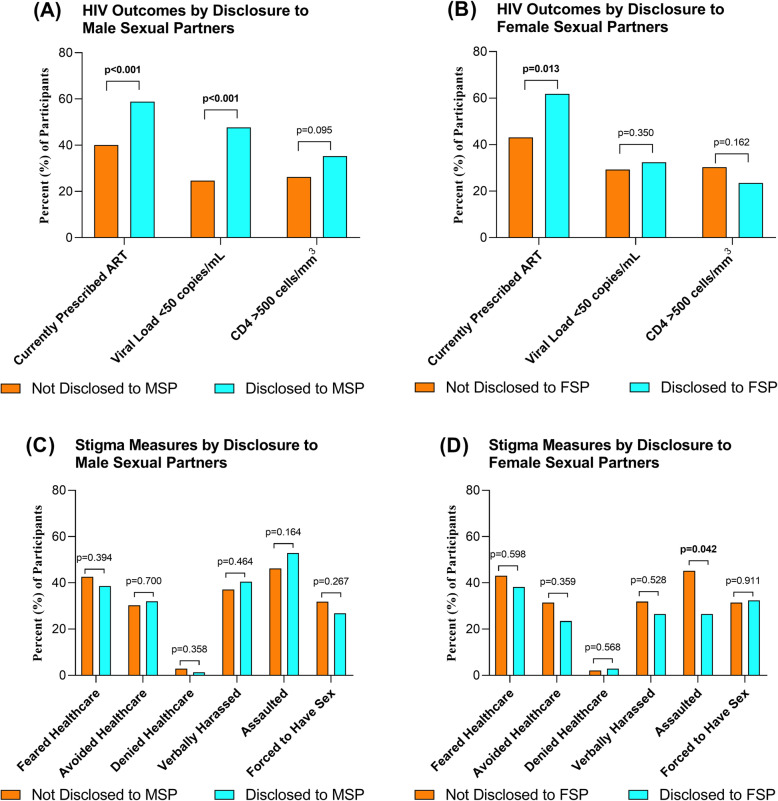

Compared to those who had not disclosed their HIV status to MSP, participants who had disclosed were more likely to be prescribed ART (58.8% versus 40.0%, p < 0.001) and to have viral load < 50 copies/mL (47.7% versus 24.7%, p < 0.001; Fig. 1a). There was no difference in the proportion of participants with CD4 > 500 cells/mm3 based on having disclosed or not to MSP (35.4% versus 26.2%, p = 0.095), though median CD4 was higher in the group that had disclosed (438 [IQR 327–572] versus 384 [IQR 270–537] cells/mm3, p = 0.032). Participants who had disclosed their status to FSP were more likely to be prescribed ART (61.8% versus 43.1%, p = 0.013; Fig. 1b). There were no statistically significant differences between participants who had and had not disclosed their HIV status to FSP in terms of viral suppression (32.4% versus 29.3%, p = 0.350), CD4 > 500 cells/mm3 (23.5% versus 30.3%, p = 0.162), or median CD4 (337 [IQR 172–651] versus 409 [IQR 267–558] cells/mm3, p = 0.219).

Fig. 1.

Associations of HIV Status Disclosure with HIV Care Outcomes and Self-Reported Stigma among Nigerian Men who have Sex with Men and Transgender Women. Medical records were reviewed at study enrollment to ascertain ART prescription status. HIV viral load and CD4 count were enumerated for all enrolled participants living with HIV. Participants were asked whether or not they had ever experienced a variety of specific indicators of anticipated and enacted stigma. The percentage of participants demonstrating each key HIV care outcome is presented with stratification by disclosure of HIV status to male sexual partners (Panel a) and to female sexual partners (Panel b). The percentage of participants who reported each stigma indicator is presented with stratification by disclosure of HIV status to male sexual partners (Panel c) and to female sexual partners (Panel d). Statistically significant p-values (p ≤ 0.05) for comparisons by disclosure status are in bold

Stigma

The prevalence of self-reported stigma indicators was similar between participants who had disclosed their HIV status to MSP and those who had not (Fig. 1c). Participants who disclosed their HIV status to FSP were less likely to report assault than were participants who had not disclosed to FSP (26.5% versus 45.2%, p = 0.042), but other indicators of stigma did not vary by disclosure status to FSP (Fig. 1d).

Factors associated with HIV status disclosure

After adjusting for other factors, HIV status disclosure to MSP was more likely among participants at the Lagos site (RR 1.58 [95% CI 1.14–2.20, P = 0.006]) or who were virally suppressed (RR 1.67 [95% CI 1.24–2.25, P < 0.001]) and less likely with increasing education levels (RR 0.63 [95% CI 0.41–0.95, P = 0.029]) (Table 2). HIV status disclosure to FSP was more likely among participants that were married or living with a woman (RR 3.95 [95% CI 1.97–7.91, P < 0.001]), were working in entertainment industries (RR 6.25 [95% CI 1.06–36.84, P = 0.043]) or as a driver/laborer (RR 6.66 [95% CI 1.10–40.36, P = 0.039]), were prescribed ART (RR 2.27 [95% CI 1.07–4.83, P = 0.033]), and had disclosed to MSP (RR 1.93 [95% CI 1.02–3.67, P = 0.043]).

Table 2.

Factors associated with HIV status disclosure to male and female sexual partners of Nigerian men who have Sex with Men and Transgender Women

| Characteristics |

Disclosure to Some/All Male Sexual Partners Relative Risk (95% Confidence Interval) |

Disclosure to Some/All Female Sexual Partners Relative Risk (95% Confidence Interval) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | p | Adjusted | p | Unadjusted | p | Adjusted | p | |

| Age | ||||||||

| ≤ 21 years | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| 22–30 years | 1.02 (0.71–1.47) | 0.910 | 0.88 (0.61–1.28) | 0.512 | 0.72 (0.22–2.31) | 0.582 | 0.45 (0.13–1.53) | 0.201 |

| > 30 years | 1.18 (0.75–1.83) | 0.474 | 0.74 (0.46–1.19) | 0.213 | 2.61 (0.85–8.02) | 0.095 | 0.87 (0.25–3.10) | 0.835 |

| Gender Identity | ||||||||

| Man | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Woman | 0.72 (0.45–1.14) | 0.161 | 0.67 (0.43–1.05) | 0.078 | 1.55 (0.61–3.94) | 0.360 | 1.58 (0.62–4.04) | 0.336 |

| Other/Unknown | 0.88 (0.57–1.35) | 0.561 | 0.89 (0.58–1.36) | 0.594 | 1.21 (0.46–3.16) | 0.696 | 1.59 (0.60–4.25) | 0.351 |

| Sexual Orientation | ||||||||

| Gay/Homosexuala | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Bisexual | 0.91 (0.70–1.20) | 0.512 | 1.01 (0.76–1.34) | 0.952 | 0.70 (0.24–2.00) | 0.500 | 0.62 (0.17–2.28) | 0.474 |

| Education Level | ||||||||

| Junior Secondary or lessa | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Senior Secondary | 0.60 (0.39–0.92) | 0.019 | 0.47 (0.30–0.73) | < 0.001 | 0.76 (0.25–2.29) | 0.624 | 1.24 (0.51–3.03) | 0.634 |

| Higher than Senior Secondary | 0.79 (0.51–1.20) | 0.262 | 0.63 (0.41–0.95) | 0.029 | 0.74 (0.24–2.26) | 0.594 | 1.40 (0.55–3.56) | 0.476 |

| Occupation | ||||||||

| Unemployed | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Student | 0.82 (0.47–1.42) | 0.474 | 0.78 (0.46–1.33) | 0.369 | 0.93 (0.06–14.03) | 0.956 | 1.62 (0.15–17.42) | 0.689 |

| Professional/Self-Employed | 1.16 (0.72–1.88) | 0.545 | 0.97 (0.59–1.59) | 0.902 | 3.45 (0.41–28.87) | 0.254 | 2.84 (0.48–16.70) | 0.247 |

| Entertainment/Hospitality | 0.72 (0.37–1.41) | 0.336 | 0.87 (0.44–1.72) | 0.685 | 6.94 (0.89–54.47) | 0.065 | 6.25 (1.06–36.84) | 0.043 |

| Driver/Laborer | 1.09 (0.41–2.93) | 0.863 | 0.92 (0.41–2.07) | 0.834 | 4.17 (0.30–57.50) | 0.287 | 6.66 (1.10–40.36) | 0.039 |

| Other/Unknown/Missing | 1.08 (0.73–1.60) | 0.693 | 1.24 (0.80–1.91) | 0.334 | 4.70 (0.66–33.27) | 0.121 | 4.06 (0.84–19.74) | 0.082 |

| Marital Status | ||||||||

| Single/Never Married | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Married/Cohabiting | 1.35 (0.88–2.05) | 0.166 | 1.16 (0.71–1.90) | 0.545 | 5.59 (3.18–9.84) | < 0.001 | 3.95 (1.97–7.91) | < 0.001 |

| Divorced/Widowed/Other | 1.70 (1.09–2.65) | 0.018 | 1.29 (0.86–1.94) | 0.210 | 2.31 (0.63–8.46)3 | 0.207 | 1.26 (0.31–5.08)3 | 0.748 |

| Site | ||||||||

| Abuja | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Lagos | 1.17 (0.90–1.52) | 0.242 | 1.58 (1.14–2.20) | 0.006 | 0.59 (0.27–1.28) | 0.181 | 1.03 (0.33–3.25) | 0.960 |

| CD4 Count | ||||||||

| < 500 cells/mm3 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| ≥ 500 cells/mm3 | 1.31 (0.99–1.72) | 0.055 | 1.10 (0.83–1.45) | 0.496 | 0.86 (0.40–1.85) | 0.691 | 0.85 (0.42–1.70) | 0.639 |

| Unknown/Missing | 0.82 (0.47–1.46) | 0.505 | 1.31 (0.71–2.41) | 0.381 | 1.95 (0.92–4.13) | 0.084 | 2.53 (0.99–6.44) | 0.051 |

| Viral Load | ||||||||

| > =50 copies/mL | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| < 50 copies/mL | 1.87 (1.44–2.43) | < 0.001 | 1.67 (1.24–2.25) | < 0.001 | 1.28 (0.64–2.58) | 0.482 | 0.61 (0.26–1.41) | 0.247 |

| Unknown/Missing | 0.67 (0.33–1.36) | 0.268 | 0.57 (0.23–1.39) | 0.218 | 1.85 (0.81–4.23) | 0.145 | 0.77 (0.23–2.53) | 0.667 |

| Currently Prescribed ART | ||||||||

| No | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Yes | 1.67 (1.27–2.19) | < 0.001 | 1.32 (0.93–1.86) | 0.117 | 1.56 (0.99–2.44) | 0.053 | 2.27 (1.07–4.83) | 0.033 |

| Unknown/Missing | 0.76 (0.21–2.72) | 0.677 | 1.34 (0.29–6.13) | 0.706 | 0.58 (0.09–3.77) | 0.572 | 1.82 (0.48–6.87) | 0.377 |

| Disclosed to Healthcare Provider | ||||||||

| No | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Yes, any HCP | 1.98 (1.26–3.12) | 0.003 | 1.51 (0.93–2.46) | 0.097 | 3.06 (1.30–7.23) | 0.011 | 1.09 (0.42–2.82) | 0.857 |

| Disclosed to Male Sexual Partners | ||||||||

| No | Not Applicable | Not Applicable | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Some or all MSP | 2.18 (1.19–4.01) | 0.012 | 1.93 (1.02–3.67) | 0.043 | ||||

| Disclosed to Female Sexual Partners | ||||||||

| No | Reference | Reference | Not Applicable | Not Applicable | ||||

| Some or all FSP | 1.54 (1.04–2.26) | 0.030 | 1.45 (0.97–2.18) | 0.069 | ||||

| Not Applicable (No FSP) | 1.14 (0.81–1.62) | 0.447 | 1.21 (0.82–1.79) | 0.338 | ||||

Abbreviations: ART antiretroviral therapy, HCP healthcare provider, FSP female sexual partner, MSP male sexual partner

aTo enable convergence of the models, “other/unknown” was combined into the reference group for sexual orientation and education level

Modified Poisson regression models were used to calculate relative risk and 95% confidence intervals for factors associated with HIV status disclosure. All variables in unadjusted models were included in the adjusted model for disclosure to each sex. All 493 participants included in these analyses reported male sexual partners in the preceding 12 months and contributed data to the models for disclosure to male sexual partners. Only the 222 participants who reported female sexual partners in the preceding 12 months contributed data to the models for disclosure to female sexual partners. Statistically significant associations (p ≤ 0.05) are shown in bold

Discussion

We found that HIV status disclosure was relatively uncommon to sexual partners of Nigerian MSM and TGW living with HIV. Our finding that about one-third disclosed to MSP and one-sixth to FSP is similar to the 33% of MSM who disclosed their HIV status to sexual partners in one internet-based study in Asia [36] but much lower than the approximately 70% of MSM living with HIV in the United States who have disclosed to their partners [37, 38]. HIV-related stigma is one potential barrier to HIV status disclosure, which has been extensively documented among Nigerian MSM and TGW and can intersect with stigmas related to same-sex sexual practices [17, 21, 39]. These intersecting stigmas likely contributed to the lower prevalence of HIV status disclosure in our study as compared to the US, where stigma related to both HIV and same-sex sexual practices is less severe [40]. Notably, Nigeria passed an antidiscrimination bill into law in early 2015 that aimed to protect the rights and dignity of PLWH [41], but did so months after passing a law that criminalized same-sex sexual practices and relationships [42].

In our study, HIV status disclosure to sexual partners was associated with improved ART uptake, greater likelihood of viral suppression, and increased CD4 count. This finding is consistent with previous data among PLWH that suggested that disclosure improved access to HIV care and treatment [22–24, 27]. In addition, disclosure has been associated with reduced frequency of condomless sex and other behaviors associated with HIV transmission and acquisition [23, 24]. Facilitating HIV status disclosure could be a useful component of comprehensive care models to improve individual health of PLWH and decrease HIV transmission risk.

There is concern that potential beneficial effects of disclosure could be offset by adverse consequences such as societal rejection, persecution, discrimination, abandonment, separation and feelings of shame, worry or fear [17, 21, 39]. MSM and TGW living with HIV may face additional stigma due to same-sex sexual practices [9, 17–20]. However, we found few differences in self-reported stigma based on disclosure status. In fact, disclosure to FSP was associated with decreased risk of assault, a desirable indicator of decreased stigma. These findings suggest that safe spaces for disclosure of HIV status exist within some individual sexual partnerships of PLWH attending trusted community healthcare centers in Lagos and Abuja, Nigeria. Continued education and counseling to facilitate discussion and disclosure of HIV status should be provided to PLWH and those in serodiscordant partnerships.

These analyses were strengthened by an RDS recruitment strategy that enabled enrollment and characterization of hard-to-reach populations and a standardized questionnaire that enabled thorough description of demographic characteristics, disclosure patterns, and stigma indicators. However, these analyses may have been susceptible to response and reporting biases from self-reporting of sensitive and potentially stigmatizing information to study interviewers. Stigma indicators were constructed around perceived and experienced stigma due to same-sex sexual practices, which may be different from any stigma experienced due to HIV status. Furthermore, these analyses used pooled data from populations independently recruited in two cities using RDS to evaluate internal relationships between HIV status disclosure and other variables of interest; they did not account for any sampling bias introduced through the RDS recruitment methodology. Recruitment spanned a five-year period and longitudinal changes in HIV status disclosure practices were not evaluated in these cross-sectional analyses but could have been influenced by factors such as passage of the Same-Sex Marriage Prohibition Act in 2014. Findings from participants recruited at community health centers catering to sexual and gender minorities in Nigerian urban centers may not be generalizable to populations unwilling or unable to access care at such dedicated facilities.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated complex relationships between of HIV status disclosure, stigma, and HIV care outcomes among Nigerian MSM and TGW attending trusted community healthcare centers in Lagos and Abuja. Cultural and behavioral implications of HIV status disclosure must be carefully considered when designing interventional strategies to engage MSM and TGW in HIV prevention and treatment. Interventions that encourage HIV status disclosure should be accompanied by community education about HIV, creation of safe spaces for PLWH to access care, and promotion of policies to encourage acceptance of PLWH in their communities. Similar sensitization to the needs of gender and sexual minorities must also be conducted. Improved HIV status disclosure practices are necessary to improve HIV care uptake and decrease HIV transmission among key populations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Supplementary File 1. TRUST/RV368 Questionnaire (Visit 0). Participant demographics, perceptions and experiences of stigma, and sexual behaviors were evaluated using questionnaires developed specifically for this study that were administered by a trained interviewer over the first two study visits, approximately two weeks apart. The first set of questions (Visit 0) covered demographic and socioeconomic information; human rights and exposure to violations; disclosure of same-sex sexual practices; risk behavior with sexual partners; depression; and knowledge, attitudes, and behavior.

Additional file 2: Supplementary File 2. TRUST/RV368 Questionnaire (Visit 1). Participant demographics, perceptions and experiences of stigma, and sexual behaviors were evaluated using questionnaires developed specifically for this study that were administered by a trained interviewer over the first two study visits, approximately two weeks apart. The second set of questions (Visit 1) covered sexual network risks; composition and influence of social networks; condom negotiation; social capital; and exposure to health information.

Acknowledgments

The TRUST/RV368 Study Group includes Principal Investigators: Manhattan Charurat (IHV, University of Maryland, Baltimore, MD, USA), Julie Ake (MHRP, Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, Silver Spring, MD, USA); Co-Investigators: Aka Abayomi, Sylvia Adebajo, Stefan Baral, Trevor Crowell, Charlotte Gaydos, Afoke Kokogho, Jennifer Malia, Olumide Makanjuola, Nelson Michael, Nicaise Ndembi,, Rebecca Nowak, Oluwasolape Olawore, Zahra Parker, Sheila Peel, Habib Ramadhani, Merlin Robb, Cristina Rodriguez-Hart, Eric Sanders-Buell, Elizabeth Shoyemi, Sodsai Tovanabutra, Sandhya Vasan; Institutions: Institute of Human Virology at the University of Maryland School of Medicine (IHV-UMB), Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health (JHSPH), Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine (JHUSOM), U.S. Military HIV Research Program (MHRP), Walter Reed Army Institute of Research (WRAIR), Henry M. Jackson Foundation for the Advancement of Military Medicine (HJF), Henry M. Jackson Foundation Medical Research International (HJFMRI), Institute of Human Virology Nigeria (IHVN), International Centre for Advocacy for the Right to Health (ICARH), The Initiative for Equal Rights (TIERS), Population Council Nigeria.

Prior presentation

This work was presented, in part, at the 20th International Conference on AIDS and STIs in Africa, Kigali, Rwanda, 2–7 December 2019.

Disclaimer

The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be construed to represent the positions of the U.S. Army, the Department of Defense, or the Department of Health and Human Services. The investigators have adhered to the policies for protection of human subjects as prescribed in AR-70.

Abbreviations

- ART

Antiretroviral therapy

- CI

Confidence interval

- FSP

Female sexual partners

- IQR

Interquartile range

- IRB

Institutional review board

- MSM

Men who have sex with men

- MSP

Male sexual partners

- PLWH

People living with HIV

- RR

Risk ratio

- TGW

Transgender women

Authors’ contributions

ABT formulated the research question and authored the first draft of the manuscript. JL and FH conducted data analyses. AK, CE, SA, and GE oversaw the collection of clinical data. MEC, MLR, JAA, SDB, and RGN contributed to the design of these analyses and assisted in the interpretation of results. TAC contributed to the design of these analyses, assisted in the interpretation of results, and provided general oversight of this work. All authors reviewed this manuscript, provided feedback, and approved of the manuscript in its final form.

Funding

This work was supported by a cooperative agreement between the Henry M. Jackson Foundation for the Advancement of Military Medicine, Inc., and the U.S. Department of Defense [W81XWH-11-2-0174, W81XWH-18-2-0040]; the National Institutes of Health [R01 MH099001, R01 AI120913, R01 MH110358]; Fogarty Epidemiology Research Training for Public Health Impact in Nigeria program [D43TW010051]; and the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief through a cooperative agreement between the Department of Health and Human Services/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Global AIDS Program, and the Institute for Human Virology-Nigeria [NU2GGH002099]. The funders were involved in the design of the study, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, and writing of the report. The corresponding author had full access to all study data and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Availability of data and materials

The Henry M. Jackson Foundation for the Advancement of Military Medicine (HJF) and the U.S. Department of the Army are committed to safeguarding the privacy of all research participants. Due to the unique vulnerability of the Nigerian MSM and TGW participants in this study, the study investigators and ethical review committees have implemented additional measures to ensure participant anonymity is maintained in all reporting of research data. Distribution of de-identified participant-level data and accompanying research resources will require compliance with all applicable regulatory and ethical processes. Requests for these materials can be made via e-mail to PubRequest@hivresearch.org.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All participants provided written informed consent prior to enrollment. The study was approved by the University of Maryland Baltimore institutional review board (IRB), Baltimore, MD, USA; the Federal Capital Territory Health Research Ethics Committee, Abuja, Nigeria; Walter Reed Army Institute of Research IRB; Ministry of Defence Health Research Ethics Committee, Abuja, Nigeria; and all collaborating institutions.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Trevor A. Crowell, Email: tcrowell@hivresearch.org

for the TRUST/RV368 Study Group:

Sylvia Adebajo, Stefan Baral, Trevor Crowell, Charlotte Gaydos, Afoke Kokogho, Jennifer Malia, Olumide Makanjuola, Nelson Michael, Nicaise Ndembi, Rebecca Nowak, Oluwasolape Olawore, Zahra Parker, Sheila Peel, Habib Ramadhani, Merlin Robb, Cristina Rodriguez-Hart, Eric Sanders-Buell, Elizabeth Shoyemi, Sodsai Tovanabutra, and Sandhya Vasan

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s12889-020-09315-y.

References

- 1.World Health Organization . HIV/AIDS Key Facts. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS . The GAP Report. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Agency for the Control of AIDS . Nigeria Prevalence Rate. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS: 2018. https://www.unaids.org/en/regionscountries/countries/nigeria. Accessed 17 Apr 2020.

- 5.Vu L, Adebajo S, Tun W, Sheehy M, Karlyn A, Njab J, Azeez A, Ahonsi B. High HIV prevalence among men who have sex with men in Nigeria: implications for combination prevention. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;63(2):221–227. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31828a3e60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keshinro B, Crowell TA, Nowak RG, Adebajo S, Peel S, Gaydos CA, Rodriguez-Hart C, Baral SD, Walsh MJ, Njoku OS, et al. High prevalence of HIV, chlamydia and gonorrhoea among men who have sex with men and transgender women attending trusted community centres in Abuja and Lagos, Nigeria. J Int AIDS Soc. 2016;19(1):21270. doi: 10.7448/IAS.19.1.21270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vu L, Tun W, Sheehy M, Nel D. Levels and correlates of internalized homophobia among men who have sex with men in Pretoria, South Africa. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(3):717–723. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9948-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Allman D, Adebajo S, Myers T, Odumuye O, Ogunsola S. Challenges for the sexual health and social acceptance of men who have sex with men in Nigeria. Cult Health Sex. 2007;9(2):153–168. doi: 10.1080/13691050601040480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kokogho A, Amusu S, Baral SD, Charurat ME, Adebajo S, Makanjuola O, Tonwe V, Storme C, Michael NL, Robb ML, et al. Disclosure of same-sex sexual practices to family and healthcare providers by men who have sex with men and transgender women in Nigeria. Arch Sex Behav. 2020. 10.1007/s10508-020-01644-8. Online ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Beyrer C. Pushback: the current wave of anti-homosexuality laws and impacts on health. PLoS Med. 2014;11(6):e1001658. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beyrer C, Baral SD, Collins C, Richardson ET, Sullivan PS, Sanchez J, Trapence G, Katabira E, Kazatchkine M, Ryan O, et al. The global response to HIV in men who have sex with men. Lancet. 2016;388(10040):198–206. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30781-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees . Opening remarks by UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Navi Pillay at a press conference during her mission to Nigeria. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 13.International Association of African Researchers and Reviewers . AFRREV LALIGENS: an international journal of language and gender studies. Bahir Dar: International Association of African Researchers and Reviewers Inc.; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Floribert E, Calvain P. Christian resistance to gay-proselytism in a secular Nigeria: anathema or social heroism. Eur Rev Appl Sociol. 2015;8(11):6–13. doi: 10.1515/eras-2015-0006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ntetmen Mbetbo J. Internalised conflicts in the practice of religion among kwandengue living with HIV in Douala, Cameroun. Cult Health Sex. 2013;15(Suppl):76–87. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2013.779025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mbote DK, Sandfort TGM, Waweru E, Zapfel A. Kenyan religious Leaders' views on same-sex sexuality and gender nonconformity: religious freedom versus constitutional rights. J Sex Res. 2018;55(4–5):630–641. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2016.1255702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Preau M, Beaulieu-Prevost D, Henry E, Bernier A, Veillette-Bourbeau L, Otis J. HIV serostatus disclosure: development and validation of indicators considering target and modality. Results from a community-based research in 5 countries. Soc Sci Med. 2015;146:137–146. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rodriguez-Hart C, Musci R, Nowak RG, German D, Orazulike I, Ononaku U, Liu H, Crowell TA, Baral S, Charurat M, et al. Sexual stigma patterns among Nigerian men who have sex with men and their link to HIV and sexually transmitted infection prevalence. AIDS Behav. 2018;22(5):1662–1670. doi: 10.1007/s10461-017-1982-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rodriguez-Hart C, Nowak RG, Musci R, German D, Orazulike I, Kayode B, Liu H, Gureje O, Crowell TA, Baral S, et al. Pathways from sexual stigma to incident HIV and sexually transmitted infections among Nigerian MSM. AIDS. 2017;31(17):2415–2420. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stahlman S, Sanchez TH, Sullivan PS, Ketende S, Lyons C, Charurat ME, Drame FM, Diouf D, Ezouatchi R, Kouanda S, et al. The prevalence of sexual behavior stigma affecting gay men and other men who have sex with men across sub-Saharan Africa and in the United States. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2016;2(2):e35. doi: 10.2196/publichealth.5824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oseni OE, Okafor IP, Sekoni AO. Issues surrounding HIV status disclosure: experiences of seropositive women in Lagos, Nigeria. Int J Prev Med. 2017;8:60. doi: 10.4103/ijpvm.IJPVM_136_15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ekama SO, Herbertson EC, Addeh EJ, Gab-Okafor CV, Onwujekwe DI, Tayo F, Ezechi OC. Pattern and determinants of antiretroviral drug adherence among Nigerian pregnant women. J Pregnancy. 2012;2012:851810. doi: 10.1155/2012/851810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.King R, Katuntu D, Lifshay J, Packel L, Batamwita R, Nakayiwa S, Abang B, Babirye F, Lindkvist P, Johansson E, et al. Processes and outcomes of HIV serostatus disclosure to sexual partners among people living with HIV in Uganda. AIDS Behav. 2008;12(2):232–243. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9307-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Przybyla S, Golin C, Widman L, Grodensky C, Earp JA, Suchindran C. Examining the role of serostatus disclosure on unprotected sex among people living with HIV. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2014;28(12):677–684. doi: 10.1089/apc.2014.0203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Salami AK, Fadeyi A, Ogunmodede JA, Desalu OO. Status disclosure among people living with HIV/AIDS in Ilorin, Nigeria. West Afr J Med. 2011;30(5):359–363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salami A, Araoye M, Adamu U. Knowledge, risk perception and willingness of relatives of patients to submit to voluntary HIV counseling and testing. Afr J Clin Exp Microbiol. 2006;7:57–64. [Google Scholar]

- 27.O'Connell AA, Reed SJ, Serovich JA. The efficacy of serostatus disclosure for HIV transmission risk reduction. AIDS Behav. 2015;19(2):283–290. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0848-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ogoina D, Ikuabe P, Ebuenyi I, Harry T, Inatimi O, Chukwueke O. Types and predictors of partner reactions to HIV status disclosure among HIV-infected adult Nigerians in a tertiary hospital in the Niger Delta. Afr Health Sci. 2015;15(1):10–18. doi: 10.4314/ahs.v15i1.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Serovich JM, Mosack KE. Reasons for HIV disclosure or nondisclosure to casual sexual partners. AIDS Educ Prev. 2003;15(1):70–80. doi: 10.1521/aeap.15.1.70.23846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wolitski RJ, Bailey CJ, O'Leary A, Gomez CA, Parsons JT. Seropositive urban Men's s: self-perceived responsibility of HIV-seropositive men who have sex with men for preventing HIV transmission. AIDS Behav. 2003;7(4):363–372. doi: 10.1023/B:AIBE.0000004728.73443.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Driskell JR, Salomon E, Mayer K, Capistrant B, Safren S. Barriers and facilitators of HIV disclosure: perspectives from HIV-infected men who have sex with men. J HIV AIDS Soc Serv. 2008;7(2):135–156. doi: 10.1080/15381500802006573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Odiachi A, Erekaha S, Cornelius LJ, Isah C, Ramadhani HO, Rapoport L, Sam-Agudu NA. HIV status disclosure to male partners among rural Nigerian women along the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV cascade: a mixed methods study. Reprod Health. 2018;15(1):36. doi: 10.1186/s12978-018-0474-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baral SD, Ketende S, Schwartz S, Orazulike I, Ugoh K, Peel SA, Ake J, Blattner W, Charurat M. Evaluating respondent-driven sampling as an implementation tool for universal coverage of antiretroviral studies among men who have sex with men living with HIV. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;68(Suppl 2):S107–S113. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Merrigan M, Azeez A, Afolabi B, Chabikuli ON, Onyekwena O, Eluwa G, Aiyenigba B, Kawu I, Ogungbemi K, Hamelmann C. HIV prevalence and risk behaviours among men having sex with men in Nigeria. Sex Transm Infect. 2011;87(1):65–70. doi: 10.1136/sti.2008.034991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zou G. A modified poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159(7):702–706. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wei C, Lim SH, Guadamuz TE, Koe S. HIV disclosure and sexual transmission behaviors among an internet sample of HIV-positive men who have sex with men in Asia: implications for prevention with positives. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(7):1970–1978. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0105-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cook CL, Staras SAS, Zhou Z, Chichetto N, Cook RL. Disclosure of HIV serostatus and condomless sex among men living with HIV/AIDS in Florida. PLoS One. 2018;13(12):e0207838. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0207838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rietmeijer CA, Lloyd LV, McLean C. Discussing HIV serostatus with prospective sex partners: a potential HIV prevention strategy among high-risk men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Dis. 2007;34(4):215–219. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000233668.45976.a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dahlui M, Azahar N, Bulgiba A, Zaki R, Oche OM, Adekunjo FO, Chinna K. HIV/AIDS related stigma and discrimination against PLWHA in Nigerian population. PLoS One. 2015;10(12):e0143749. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0143749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS . Reducing HIV Stigma and Discrimination: a critical part of national AIDS programmes. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS . Nigeria passes law to stop discrimination related to HIV. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schwartz SR, Nowak RG, Orazulike I, Keshinro B, Ake J, Kennedy S, Njoku O, Blattner WA, Charurat ME, Baral SD, et al. The immediate eff ect of the same-sex marriage prohibition act on stigma, discrimination, and engagement on HIV prevention and treatment services in men who have sex with men in Nigeria: analysis of prospective data from the TRUST cohort. Lancet HIV. 2015;2(7):e299–e306. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(15)00078-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Supplementary File 1. TRUST/RV368 Questionnaire (Visit 0). Participant demographics, perceptions and experiences of stigma, and sexual behaviors were evaluated using questionnaires developed specifically for this study that were administered by a trained interviewer over the first two study visits, approximately two weeks apart. The first set of questions (Visit 0) covered demographic and socioeconomic information; human rights and exposure to violations; disclosure of same-sex sexual practices; risk behavior with sexual partners; depression; and knowledge, attitudes, and behavior.

Additional file 2: Supplementary File 2. TRUST/RV368 Questionnaire (Visit 1). Participant demographics, perceptions and experiences of stigma, and sexual behaviors were evaluated using questionnaires developed specifically for this study that were administered by a trained interviewer over the first two study visits, approximately two weeks apart. The second set of questions (Visit 1) covered sexual network risks; composition and influence of social networks; condom negotiation; social capital; and exposure to health information.

Data Availability Statement

The Henry M. Jackson Foundation for the Advancement of Military Medicine (HJF) and the U.S. Department of the Army are committed to safeguarding the privacy of all research participants. Due to the unique vulnerability of the Nigerian MSM and TGW participants in this study, the study investigators and ethical review committees have implemented additional measures to ensure participant anonymity is maintained in all reporting of research data. Distribution of de-identified participant-level data and accompanying research resources will require compliance with all applicable regulatory and ethical processes. Requests for these materials can be made via e-mail to PubRequest@hivresearch.org.