Abstract

Background

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) can induce immune-related adverse events (irAEs) including thyroid dysfunction. There are only a few reports on Graves’ disease induced by ICIs. We report a case of new-onset Graves’ disease after the initiation of nivolumab therapy in a patient receiving gastric cancer treatment.

Case presentation

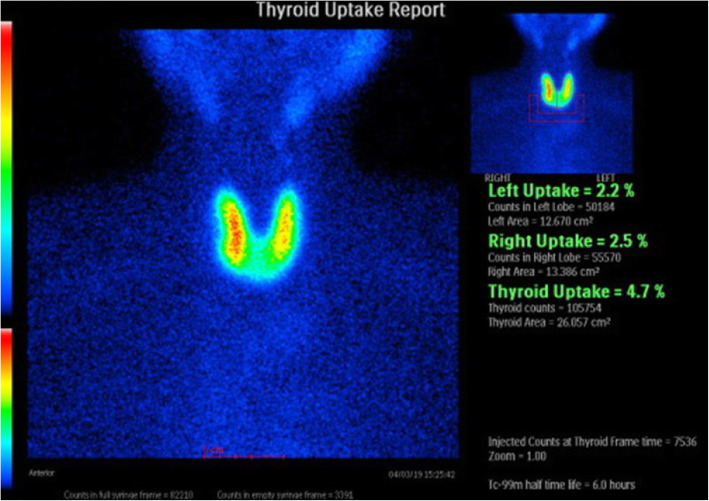

The patient was a 66-year-old Japanese man, who was administered nivolumab (240 mg every 3 weeks) as a third-line therapy for stage IVb gastric cancer. His thyroid function was normal before the initiation of nivolumab therapy. However, he developed thyrotoxicosis before the third administration of nivolumab. Elevated, bilateral, and diffuse uptake of radioactive tracer was observed in the 99mTc-pertechnetate scintigraphy. Furthermore, the thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor antibody (TRAb) and thyroid-stimulating antibody (TSAb) test results, which were negative before the first administration of nivolumab, were positive after starting the therapy. The patient was diagnosed with Graves’ disease, and the treatment with methimazole and potassium iodide restored thyroid function.

Conclusions

This is the first complete report of a case of new-onset Graves’ disease after starting nivolumab therapy, confirmed by diffusely increased thyroid uptake in scintigraphy and the positive conversion of antibodies against thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor. It is important to perform thyroid scintigraphy and ultrasonography to accurately diagnose and treat ICI-induced thyrotoxicosis, because there are various cases in which Graves’ disease is developed with negative and positive TRAb titres.

Keywords: Graves’ disease, Nivolumab, Thyrotoxicosis, Immune checkpoint inhibitor, 99mTc-pertechnetate scintigraphy, Thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor antibody

Background

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), such as cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4), programmed cell death protein-1 (PD-1), and programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) inhibitors, have been widely used as a standard cancer treatment during recent years. However, occasionally, ICIs cause immune-related adverse events (irAEs), which affect different organs, such as the lung, gastrointestinal tract, liver, nervous system, skin, and endocrine glands. The endocrine irAEs include hypophysitis, thyroid dysfunction, adrenal insufficiency, and type 1 diabetes. While endocrine irAEs due to CTLA-4 inhibitors, such as ipilimumab and tremelimumab, mainly include pituitary dysfunction, those due to PD-1 inhibitors, such as nivolumab and pembrolizumab, are mainly related to thyroid dysfunction [1–4]. The PD-1 inhibitor-induced thyroid dysfunction often includes hypothyroidism rather than hyperthyroidism [1, 2, 5, 6]. Thyrotoxicosis following ICI therapy is caused mostly by thyroiditis syndrome, which has been reported to spontaneously recover with the subsequent hypothyroidism in many cases [2, 7, 8]. However, Graves’ disease induced by ICI treatment has not been extensively explored. Here, we present a case of Graves’ disease shortly after the initiation of nivolumab therapy for gastric cancer.

Case presentation

A 66-year-old man was diagnosed with stage IVb (T4bN0M1) human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-positive gastric cancer at Nippon Medical School Chiba Hokusoh Hospital, one and a half years before the onset of thyrotoxicosis. After diagnosis, he was not referred for surgery because of liver metastasis with a portal tumour thrombus; rather, the patient received 8 cycles of first line chemotherapy with a combination of tegafur/gimeracil/oteracil (S-1), cisplatin, and trastuzumab. However, the patient presented with progressive disease, assessed based on the computed tomography (CT) and oesophagogastroduodenoscopy (OGD) evaluations following the first line therapy. Hence, he received a second line chemotherapy with paclitaxel and ramucirumab. After 4 cycles of the second line chemotherapy, although there was a reduction in tumour size, after 10 cycles, the patient presented with progressive disease, as assessed by CT. At this stage, nivolumab (240 mg every 3 weeks) was started. The patient had a normal thyroid function before the first administration. However, TSH suppression was observed before the second administration, and thyrotoxicosis occurred before the third administration of the drug; hence, nivolumab therapy was discontinued and the patient was referred to our department.

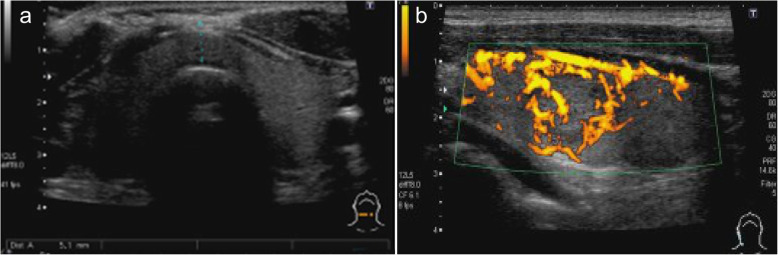

The patient had complained of fatigue and shortness of breath during exertion. His height was 174.5 cm, body weight was 79.85 kg, heart rate was 114 beats per minute, and blood pressure was 86/62 mmHg. There was no evidence of Graves’ orbitopathy or pretibial myxedema. He and his family members had no history of thyroid diseases. The thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), free triiodothyronine (FT3), and free thyroxine (FT4) levels were < 0.010 μIU/mL, 15.30 pg/mL, and > 5.00 ng/dL, respectively (Table 1). The titres of thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor antibody (TRAb) and thyroid-stimulating antibody (TSAb) were positive (24.2 IU/L and 2184%, respectively), whereas those of anti-thyroglobulin antibody (TgAb) and anti-thyroid-peroxidase antibody (TPOAb) were negative (14.1 IU/L and < 9.0 IU/L, respectively). The thyroglobulin (Tg) level was 347.00 ng/mL. Thyroid ultrasonography showed slight goitre (Fig. 1a) and rich blood flow in the parenchyma (Fig. 1b). 99mTc-pertechnetate scintigraphy, which was performed on the first consultation day of the patient at our department, showed elevated, bilateral, and diffuse uptake of the radioactive tracer (Fig. 2). We measured anti-thyroid autoantibodies in preserved serum samples. The titres of TRAb and TSAb were negative before the first administration of nivolumab, whereas they were positive (3.1 IU/L and 227%, respectively) before the second administration. Thus, we diagnosed his thyrotoxicosis as new-onset Graves’ disease after the initiation of nivolumab therapy. The human leukocyte antigen (HLA) typing of the patient showed the following allelic variants: A*24:02/26:01, B*51:01/54:01, C*01:02/15:02, DRB1*04:05/15:01, DQA1*01:02/03:01, DQB1*04:01/06:02, DPA1*02:02, and DPB1*05:01.

Table 1.

TSH, FT3, FT4, and Tg levels and TRAb and TSAb titres in our patient

| Day of nivolumab administration | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 21 | 43 | 72 | 100 | 107 | 114 | 121 | 139 | |

| TSH (μIU/mL) | 2.822 | 0.133 | < 0.010 | < 0.010 | < 0.010 | < 0.010 | 0.027 | 0.034 | 0.010 |

| FT3 (pg/mL) | 1.73 | 2.82 | 15.30 | 2.57 | 1.80 | < 1.50 | 1.98 | 1.58 | 1.67 |

| FT4 (ng/dL) | 0.86 | 1.15 | > 5.00 | 1.18 | 0.82 | 0.80 | 0.70 | 0.70 | 1.18 |

| TRAb (IU/L) | < 1.0 | 3.1 | 24.2 | 27.5 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 10.7 |

| TSAb (%) | 95 | 227 | 2184 | NA | NA | 1683 | NA | NA | 667 |

| Tg (ng/mL) | 11.20 | 40.70 | 347.00 | 28.70 | |||||

Day 0: first administration of nivolumab, Day 21: second administration of nivolumab

The normal range of the thyroid parameters is as follows: TSH (0.350–4.940 μIU/mL), FT3 (1.88–3.18 pg/mL), FT4 (0.70–1.48 ng/dL), TRAb (< 1.0 IU/L), TSAb (≤ 120%), and Tg (≤ 33.70 ng/mL)

Fig. 1.

Thyroid ultrasonography of the patient. a Slight swelling in isthmus. b Rich blood flow in parenchyma

Fig. 2.

99mTc-pertechnetate scintigraphy showing elevated, bilateral, and diffuse uptake of the radioactive tracer (4.7%)

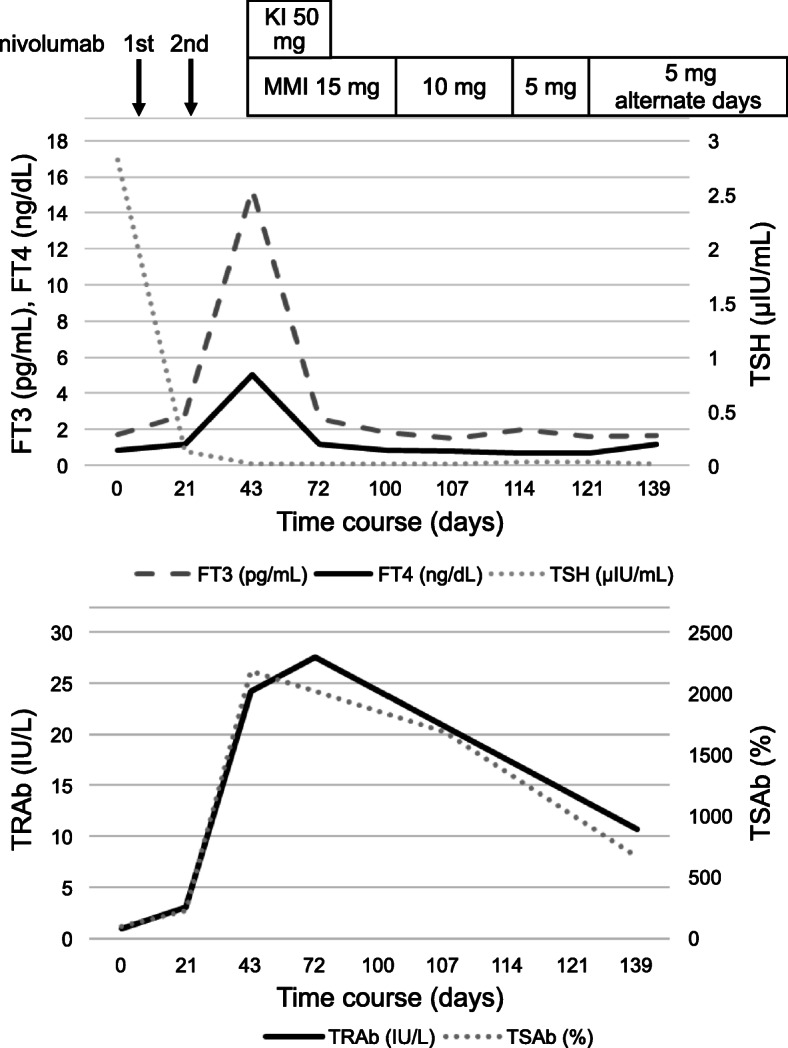

We treated the patient with methimazole (MMI) at a dose of 15 mg/day and potassium iodide (KI) at a dose of 50 mg/day. One month after the initiation of the therapy, when the FT3 and FT4 levels of the patient were normal, we discontinued KI. Gradually, we reduced the dosage of MMI, and the continued administration (till the death of the patient) of MMI at a dose of 5 mg every alternate day stabilised his thyroid function (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Clinical course of the patient. MMI: methimazole, KI: potassium iodide. Day 0: first administration of nivolumab, Day 21: second administration of nivolumab

Furthermore, as nivolumab was found to be ineffective (based on the CT and OGD evaluations), the patient received irinotecan therapy. However, after 2 cycles of chemotherapy, the patient was diagnosed with brain metastasis by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), for which, he received gamma knife and steroid therapy. The patient died 4 months after his first visit to our department.

Discussion and conclusions

We present a case of new-onset Graves’ disease after the initiation of nivolumab therapy in a patient receiving gastric cancer treatment. Thyrotoxicosis, induced by ICIs, is mainly a form of destructive thyroiditis. Three cases of new-onset Graves’ disease during nivolumab therapy, other than the present case, have been reported [9–11] (Table 2). Iadarola et al. [9] reported a case of Graves’ disease-like hyperthyroidism after the second administration of nivolumab in a patient with left lung carcinoma. In this case, 99mTc-pertechnetate scintigraphy in the patient with T3-toxicosis showed diffuse thyroid uptake of the radionuclide suggesting Graves’ disease-like hyperthyroidism, whereas the TRAb tests were consistently negative. Thyroid ultrasonography showed a multinodular goitre, with a normo-echoic pattern and normal vascularity of the parenchyma [9]. Brancatella et al. [10] reported a case similar to that of Iadarola et al. [9] with diffuse thyroid uptake and negative TRAb titre. In this case, ultrasonography showed an enlargement of the thyroid with a hypoechoic pattern and mild hypervascularity. Kurihara et al. [11] reported a case of simultaneous development of Graves’ disease and type 1 diabetes mellitus during nivolumab therapy. In this case, thyrotoxicosis was detected after the sixth administration of nivolumab, with positive TRAb titre. However, ultrasonography showed no enlargement of the thyroid and a normal vascularisation pattern. This patient was clinically diagnosed as mild Graves’ disease and treated with MMI [11]. Unlike these cases, our case is important in terms of confirmation of both positive TRAb titre and diffuse thyroid uptake in scintigraphy. Moreover, titres of TRAb and TSAb were converted from negative to positive after starting nivolumab therapy. It seems reasonable to presume that Graves’ disease was induced by nivolumab, although there is a possibility of coincidence. Furthermore, our patient had HLA-DPB1*05:01, which has been reported to be associated with Japanese Graves’ disease [12, 13]. Although the involvement of HLA cannot be argued based only on a single case, accumulating similar cases might help clarify the mechanism of development of rare ICI-induced Graves’ disease.

Table 2.

Comparison of case reports on new-onset Graves’ disease during nivolumab therapy

| Study | TSH (μIU/mL) | FT3 (pg/mL) | FT4 (ng/dL) | TRAb (IU/L) | TSAb (%) | US | RAIU/ 99mTc uptake | HLA | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before | After | Before | After | |||||||

| Iadarola et al. [9] | < 0.01 | 5.71 | 1.36 | NA | Negative | NA | NA | Normal | High (99mTc) | NA |

| Brancatella et al. [10] | 0.04 | 7.29 | 2.28 | NA | Negative | NA | NA | Hyper-vascular | High (RAIU) | NA |

| Kurihara et al. [11] | 0.008 | 3.88 | 1.72 | NA | Positive (3.7) | NA | NA | Normal | NA | DRB1*04:05 |

| Yamada et al. (present case) | < 0.010 | 15.30 | > 5.00 | Negative (< 1.0) | Positive (24.2) | Negative (95) | Positive (2184) | Hyper-vascular | High (99mTc) | DPB1*05:01 |

US ultrasonography, RAIU radioactive iodine uptake, Before: before the initiation of nivolumab therapy, After: after the initiation of nivolumab therapy (at the onset of the thyrotoxicosis)

Graves’ disease induced by ICIs other than nivolumab has been rarely reported. Azmat et al. [14] reported a case of ipilimumab-induced thyrotoxicosis caused by Graves’ disease. Gan et al. [15] reported a case of tremelimumab-induced Graves’ hyperthyroidism. Yajima et al. [16] reported a case of Graves’ disease induced by pembrolizumab, a PD-1 inhibitor. In this case, TRAb was positive after the fifth administration of pembrolizumab, and thyroid ultrasonography showed a mild increase in the intra-thyroidal blood flow. A thyroid scintigraphy was not performed because of the iodine treatment [16]. The cases of nivolumab-induced Graves’ disease with negative TRAb titre suggest that performing thyroid scintigraphy and ultrasonography can help to accurately diagnose and treat ICI-induced thyrotoxicosis.

A relationship between thyroid antibodies and PD-1 inhibitor-induced thyroid dysfunction has not been explained. Kimbara et al. [8] suggested that patients with pre-existing TgAb and an elevated TSH level at baseline are at a higher risk of thyroid dysfunction induced by nivolumab. Osorio et al. [17] reported an association between positive thyroid antibodies (anti-thyroglobulin or anti-microsomal antibodies) and thyroid dysfunction induced by ICIs. In the studies on new-onset Graves’ disease during nivolumab therapy, it is interesting to note that in two caucasian patients with Graves’ disease, TRAb was negative [9, 10]. Furthermore, TRAb was positive in two Japanese patients, including our patient [11] (Table 2). However, additional evidence is required to reveal the role of TRAb in the pathogenesis of ICI-induced hyperthyroidism.

A limitation of our case was radioactive iodine uptake (RAIU) was not performed. Because imaging with 99mTc-pertechnetate reflects both blood flow and uptake via the symporter and does not assess organification, malignant nodules may appear hyperfunctioning in pertechnetate imaging, but hypofunctioning in 123I-imaging. In our study, tumours were not detected although a part of 99mTc uptake was stronger.

In conclusion, we reported a case of Graves’ disease shortly after the initiation of nivolumab therapy for gastric cancer. Our case presented a typical Graves’ disease with both positive TRAb titre and diffuse thyroid uptake in scintigraphy. Moreover, our case is valuable in terms of confirming the conversion of TRAb and TSAb from negative to positive titres after starting the therapy. It is important to perform thyroid scintigraphy and ultrasonography because there are cases of nivolumab-induced Graves’ disease with negative TRAb titre as previously reported. To reveal the pathogenesis of ICI-induced Graves’ disease, it is necessary to study additional cases of similar nature.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- CT

Computed tomography

- CTLA-4

Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4

- FT3

Free triiodothyronine

- FT4

Free thyroxine

- HER2

Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2

- HLA

Human leukocyte antigen

- ICI

Immune checkpoint inhibitor

- IrAE

Immune-related adverse event

- KI

Potassium iodide

- MMI

Methimazole

- MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging

- OGD

Oesophagogastroduodenoscopy

- PD-1

Programmed cell death protein-1

- PD-L1

Programmed death ligand 1

- RAIU

Radioactive iodine uptake

- Tg

Thyroglobulin

- TgAb

Anti-thyroglobulin antibody

- TPOAb

Anti-thyroid-peroxidase antibody

- TRAb

TSH receptor antibody

- TSAb

Thyroid-stimulating antibody

- TSH

Thyroid-stimulating hormone

Authors’ contributions

HY, FO, and NE interpreted the data, drafted the manuscript, and participated in the endocrinological treatment of the patient. HS revised the manuscript. TO and SF participated in the gastroenterological treatment of the patient. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript for publication.

Funding

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are stored in Nippon Medical School Chiba Hokusoh Hospital (Inzai, Chiba) and available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This case report was approved by the ethics committee of Nippon Medical School Chiba Hokusoh Hospital.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient’s next of kin for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editor of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Gonzalez-Rodriguez E, Rodriguez-Abreu D, Spanish Group for Cancer Immuno-Biotherapy (GETICA) Immune checkpoint inhibitors: review and management of endocrine adverse events. Oncologist. 2016;21:804–816. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2015-0509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Michot JM, Bigenwald C, Champiat S, Collins M, Carbonnel F, Postel-Vinay S, et al. Immune-related adverse events with immune checkpoint blockade: a comprehensive review. Eur J Cancer. 2016;54:139–148. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2015.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bertrand A, Kostine M, Barnetche T, Truchetet ME, Schaeverbeke T. Immune related adverse events associated with anti-CTLA-4 antibodies: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. 2015;13:211. doi: 10.1186/s12916-015-0455-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Faje A. Immunotherapy and hypophysitis: clinical presentation, treatment, and biologic insights. Pituitary. 2016;19:82–92. doi: 10.1007/s11102-015-0671-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Topalian SL, Hodi FS, Brahmer JR, Gettinger SN, Smith DC, McDermott DF, et al. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti-PD-1 antibody in cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2443–2454. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Robert C, Schachter J, Long GV, Arance A, Grob JJ, Mortier L, et al. Pembrolizumab versus ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2521–2532. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1503093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Orlov S, Salari F, Kashat L, Walfish PG. Induction of painless thyroiditis in patients receiving programmed death 1 receptor immunotherapy for metastatic malignancies. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100:1738–1741. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-4560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kimbara S, Fujiwara Y, Iwama S, Ohashi K, Kuchiba A, Arima H, et al. Association of antithyroglobulin antibodies with the development of thyroid dysfunction induced by nivolumab. Cancer Sci. 2018;109:3583–3590. doi: 10.1111/cas.13800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iadarola C, Croce L, Quaquarini E, Teragni C, Pinto S, Bernardo A, et al. Nivolumab induced thyroid dysfunction: Unusual clinical presentation and challenging diagnosis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2019;9:813. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2018.00813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brancatella A, Viola N, Brogioni S, Montanelli L, Sardella C, Vitti P, et al. Graves' disease induced by immune checkpoint inhibitors: a case report and review of the literature. Eur Thyroid J. 2019;8:192–195. doi: 10.1159/000501824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kurihara S, Oikawa Y, Nakajima R, Satomura A, Tanaka R, Kagamu H, et al. Simultaneous development of Graves' disease and type 1 diabetes during anti-programmed cell death-1 therapy: a case report. J Diabetes Investig. 2020;11:1006–1009. doi: 10.1111/jdi.13212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dong RP, Kimura A, Okubo R, Shinagawa H, Tamai H, Nishimura Y, et al. HLA-A and DPB1 loci confer susceptibility to graves’ disease. Hum Immunol. 1992;35:165–172. doi: 10.1016/0198-8859(92)90101-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ueda S, Oryoji D, Yamamoto K, Noh JY, Okamura K, Noda M, et al. Identification of independent susceptible and protective HLA alleles in Japanese autoimmune thyroid disease and their epistasis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99:379–383. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-2841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Azmat U, Liebner D, Joehlin-Price A, Agrawal A, Nabhan F. Treatment of ipilimumab induced graves’ disease in a patient with metastatic melanoma. Case Rep Endocrinol. 2016;2016:2087525. doi: 10.1155/2016/2087525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gan EH, Mitchell AL, Plummer R, Pearce S, Perros P. Tremelimumab induced graves hyperthyroidism. Eur Thyroid J. 2017;6:167–170. doi: 10.1159/000464285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yajima K, Akise Y. A case report of Graves' disease induced by the anti-human programmed cell death-1 monoclonal antibody pembrolizumab in a bladder cancer patient. Case Rep Endocrinol. 2019;2019:2314032. doi: 10.1155/2019/2314032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Osorio JC, Ni A, Chaft JE, Pollina R, Kasler MK, Stephens D, et al. Antibody-mediated thyroid dysfunction during T-cell checkpoint blockade in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol. 2017;28:583–589. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are stored in Nippon Medical School Chiba Hokusoh Hospital (Inzai, Chiba) and available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.