Nasal decolonization is an integral part of the strategies used to control and prevent the spread of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infections. The two most commonly used agents for decolonization are intranasal mupirocin 2% ointment and chlorhexidine wash, but the increasing emergence of resistance and treatment failure has underscored the need for alternative therapies. This article discusses povidone iodine (PVP-I) as an alternative decolonization agent and is based on literature reviewed during an expert’s workshop on resistance and MRSA decolonization.

KEYWORDS: povidone iodine, nasal decolonization, surgical site infection, Staphylococcus aureus

ABSTRACT

Nasal decolonization is an integral part of the strategies used to control and prevent the spread of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infections. The two most commonly used agents for decolonization are intranasal mupirocin 2% ointment and chlorhexidine wash, but the increasing emergence of resistance and treatment failure has underscored the need for alternative therapies. This article discusses povidone iodine (PVP-I) as an alternative decolonization agent and is based on literature reviewed during an expert’s workshop on resistance and MRSA decolonization. Compared to chlorhexidine and mupirocin, respectively, PVP-I 10 and 7.5% solutions demonstrated rapid and superior bactericidal activity against MRSA in in vitro and ex vivo studies. Notably, PVP-I 10 and 5% solutions were also active against both chlorhexidine-resistant and mupirocin-resistant strains, respectively. Unlike chlorhexidine and mupirocin, available reports have not observed a link between PVP-I and the induction of bacterial resistance or cross-resistance to antiseptics and antibiotics. These preclinical findings also translate into clinical decolonization, where intranasal PVP-I significantly improved the efficacy of chlorhexidine wash and was as effective as mupirocin in reducing surgical site infection in orthopedic surgery. Overall, these qualities of PVP-I make it a useful alternative decolonizing agent for the prevention of S. aureus infections, but additional experimental and clinical data are required to further evaluate the use of PVP-I in this setting.

INTRODUCTION

Staphylococcus aureus is a leading cause of health care-associated infections worldwide (1), which include bacteremia, endocarditis, osteomyelitis (2), and surgical site infections (SSIs) (3). S. aureus infections, including those caused by methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA) and methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) strains, are associated with prolonged hospital stay and increased mortality (4). S. aureus colonizes several body sites, including the nose, throat, and perineum (5–8). It is estimated that approximately 20% of the general population are permanent nasal carriers of S. aureus (9, 10). Colonization by MRSA increases the risk of infection by up to 27% (11), with infecting strains matching colonizing strains in up to 86% of cases (9, 12).

Despite active surveillance efforts, advances in the prevention of infection and new antibiotics, MRSA remains a prominent pathogen associated with high rates of mortality (2). Decolonization, the goal of which is to decrease or eliminate bacterial load on the body, is an integral part of the strategies used to control and prevent the spread of MRSA (13). This approach involves eradication of MRSA carriage from the nose through the intranasal application of an antimicrobial agent and body washes with an antiseptic soap to eliminate bacteria from other body sites (13). The most commonly used agents for MRSA decolonization are intranasal mupirocin ointment applied to the anterior nares and chlorhexidine body wash (13–15).

Mupirocin nasal ointment is effective in eradicating MRSA colonization in 94% of cases 1 week after treatment and in 65% of cases after longer follow-up (16). Furthermore, mupirocin-based nasal decolonization decreases infections among patients in high-risk settings, including surgery, intensive care unit (ICU), hemodialysis, and long-term care (13, 16). However, there are growing concerns about decolonization failures following the emergence of mupirocin (17, 18) and chlorhexidine resistance (18–20). These concerns, along with suboptimal compliance and the high cost of branded nasal mupirocin ointment, have underscored the need for alternative therapies (15, 21, 22).

We review here the properties, antimicrobial activity, and clinical efficacy of the antiseptic agent povidone iodine (PVP-I) and discuss its role as an alternative agent for S. aureus decolonization.

METHODS

This narrative review is based primarily on literature reviewed and recommended by the authors based on their expertise and experience in S. aureus decolonization. Additional studies were identified from a search conducted in PubMed using the key terms “povidone iodine” and “Staphylococcus aureus.” Searches in Google Scholar were also carried out using the key terms “povidone iodine,” “Staphylococcus aureus,” and “methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus.” The key terms in all searches were combined using Boolean operators such as “OR” or “AND”. These main searches, carried out in June 2019, aimed to identify full text articles, reporting human studies, published with no date restrictions. Gray literature sources, such as reports, academic dissertations, and conference abstracts, were also examined. The reference lists of included articles were hand-searched to identify any potential relevant articles. A total of 379 English language publications were identified from the PubMed search, and most of these were open-access articles. Papers were selected for inclusion based on their relevance to the topics of this review: the mechanism of action and antimicrobial efficacy of PVP-I, the potential for resistance to PVP-I, and clinical evidence comparing PVP-I to mupirocin and chlorhexidine as a S. aureus decolonization agent, focusing on the efficacy, safety, and cost-effectiveness of these agents in the prevention of SSI.

POVIDONE IODINE

Properties.

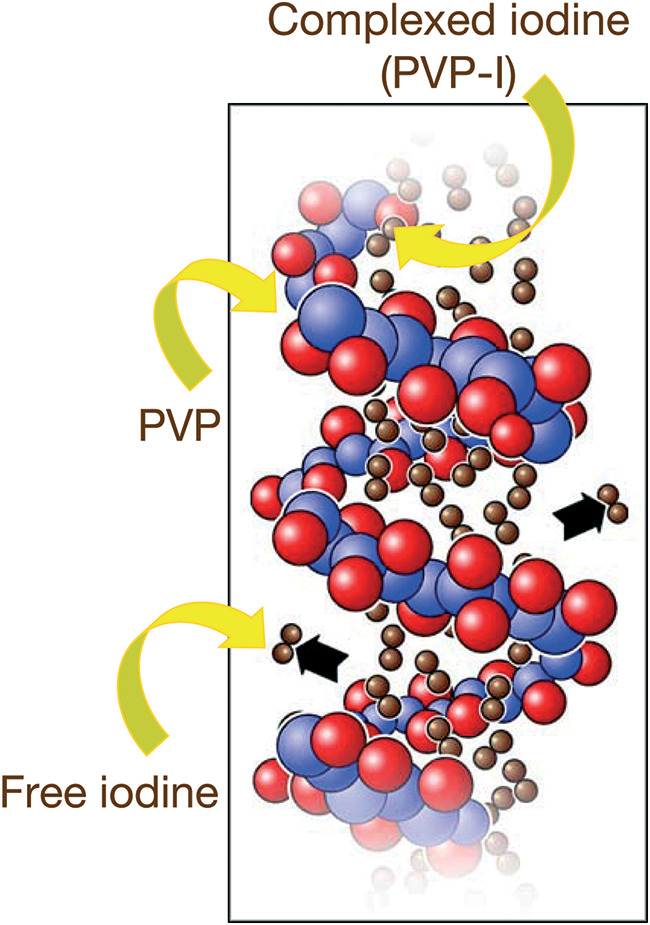

PVP-I is a water-soluble iodophor (or iodine-releasing agent) that consists of a complex between iodine and a solubilizing polymer carrier, polyvinylpyrrolidone (Fig. 1) (23, 24). In aqueous solution, a dynamic equilibrium occurs between free iodine (I2), the active bactericidal agent, and the PVP-I-complex. After dilution of PVP-I 10% solution, the iodine levels follow a bell-shaped curve and increase with dilution, reaching a maximum at approximately 0.1% strength solution and then decreasing with further dilution (25, 26). There is a good correlation between free iodine concentration and the microbicidal activity of PVP-I (25, 27).

FIG 1.

PVP-I (povidone iodine) is a complex of iodine and the solubilizing polymer carrier polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) (23, 24). In aqueous solution, a dynamic equilibrium occurs between free iodine and the PVP-I complex (25, 26).

Mechanism of action and antimicrobial spectrum.

As a small molecule, iodine rapidly penetrates into microorganisms and oxidizes key proteins, nucleotides, and fatty acids, eventually leading to cell death (23, 24). PVP-I has a broad antimicrobial spectrum with activity against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, including antibiotic-resistant and antiseptic-resistant strains (28, 29), fungi, and protozoa (Table 1) (23). It is also active against a wide range of enveloped and nonenveloped viruses (30, 31), as well as some bacterial spores with increased exposure time (23). In addition, PVP-I has been shown to have activity against mature bacterial and fungal biofilms in vitro and ex vivo (32–35).

TABLE 1.

Indicative antimicrobial spectrum of PVP-I, chlorhexidine, and ethanola

| Antiseptic | Vegetative bacteria |

Spores | Fungi | Viruses | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gram positive | Gram negative | Actinobacteria | ||||

| PVP-I, 10% | BC+++, LS | BC+++, LS | BC++ | SC++ | FC+++, LS | VC++, LS |

| Chlorhexidine | BC+++, LS | BC+++, IS | NA | NA | FC++, IS | VC+, IS |

| Ethanol 70% | BC+, LS | BC+, LS | BC+ | NA | FC+, LS | VC+ |

Data are as reported by Lachapelle et al. (23), reproduced under CC-BY license. BC, bactericidal; FC, fungicidal; IS, incomplete spectrum (signifying antimicrobial activity is limited to certain, not all, microbes); LS, large spectrum (signifying a broad spectrum of antimicrobial activity); NA, no activity; PVP-I, povidone iodine; SC, sporicidal; VC, virucidal. Strength: +, weak; ++, medium; and +++, high (based on a subjective analysis of eight papers on antiseptic agents by Lachapelle et al.).

Activity against S. aureus.

The activity of PVP-I against S. aureus has been tested using traditional in vitro suspension and surface tests, as well as more complex ex vivo porcine mucosal and human skin models. It has been suggested that ex vivo models may be more clinically relevant, since in vitro studies do not take into account host proteins that can neutralize antiseptic activity (36). In contrast, substances commonly present in test media and diluents (e.g., sulfur-containing amino acids) may negate antiseptic activity and lead to false-negative results (37).

The interpretation of in vitro studies of PVP-I is also complicated by the paradoxical increase in bactericidal activity with dilutions up to a 0.1% strength solution. This is related to the subtle equilibrium between bound and unbound iodine; the concentration of the latter active compound, I2, follows a bell-shaped curve as the dilution is increased. The activity of PVP-I against S. aureus correlates to this, and several studies have observed decreased activity at concentrations above and below 0.1% (25–27, 38–41).

In vitro studies have confirmed the bactericidal activity of PVP-I 10% solution against clinical isolates of MSSA and MRSA using both suspension tests (28, 37, 39, 42–45) and surface test methods (46). In these studies, the action of PVP-I against MSSA and MRSA was rapid, with bactericidal activity typically observed within 15 to 60 s (39, 43, 45). Comparative in vitro studies have generally showed that, irrespective of exposure time or dilution, 10% PVP-I was more active than chlorhexidine against MRSA and was bactericidal against chlorhexidine-resistant strains (28, 39, 42, 44, 46). Furthermore, two in vitro studies also showed that 5% PVP-I cream had bactericidal activity against MSSA, MRSA, and mupirocin-resistant strains of MRSA (40, 43). However, the in vitro activity of PVP-I, but not mupirocin, was reduced by the addition of nasal secretions (40).

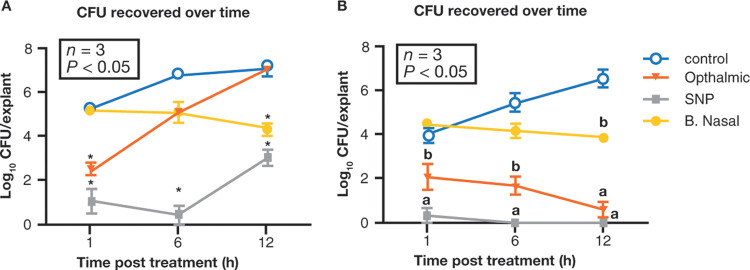

In an ex vivo model of porcine vaginal mucosa infected with MSSA, 7.5% PVP-I solution significantly reduced bacterial load (measured in log CFU/explant) at 0.25 to 4 h compared to untreated controls, although some regrowth was evident at 24 h (36). In the same porcine model infected with MRSA, a skin and nasal preparation (SNP) of 5% PVP-I significantly reduced viable bacterial cells after 1 h versus the control (1.09 ± 0.57 versus 5.30 ± 0.06 log10 CFU/explant, respectively; P < 0.05), with sustained activity over 12 h (P < 0.05 versus the control) (47). Interestingly, an ophthalmic iodine preparation lacked this sustained activity, only significantly differing from control at 1 h (2.51 ± 0.20; P < 0.05). Conversely, mupirocin had a slower onset of action (5.14 ± 0.09 at 1 h, 5.07 ± 0.06 at 6 h; P > 0.05), with significant bactericidal effects evident only after 12 h (Fig. 2A) (47). The SNP of 5% PVP-I was also significantly more effective than mupirocin against low-level and high-level mupirocin-resistant MRSA isolates in this porcine model (P < 0.05) (47). Finally, in a human skin model infected with MRSA, both the SNP and the ophthalmic PVP-I-based 5% preparation were significantly bactericidal after 1, 6, and 12 h compared to controls (P < 0.05), whereas mupirocin was only significantly bactericidal versus control after 12 h (P < 0.05) (Fig. 2B) (47).

FIG 2.

Efficacy of PVP-I (5% ophthalmic solution or 5% SNP), 2% mupirocin (B. Nasal), or no treatment (control) against MRSA infection in ex vivo models of porcine vaginal mucosa (A) and human skin (B) (adapted from ref. 47). The results are expressed in log10 CFU per explant recovered over time. Values are means ± the standard errors of the means (indicated by error bars). Values that are significantly different (P < 0.05) from untreated controls are indicated by an asterisk in panel A. In panel B, values with a different letter (a, b, or no letter) are significantly different (P < 0.05) from each other, and values with the same letter are not significantly different (P > 0.05) from each other. In panel A, the SNP of 5% PVP-I had significant activity versus the control at all time points, whereas the ophthalmic PVP-I preparation and mupirocin only differed significantly from control at 1 and 12 h, respectively. In panel B, both the SNP and the ophthalmic 5% PVP-I preparations were significantly bactericidal at 1, 6, and 12 h versus the control (P < 0.05), while mupirocin only differed significantly from control at 12 h (P < 0.05). Labels: B. Nasal, Bactroban nasal ointment; MRSA, methicillin-resistant S. aureus; PVP-I, povidone iodine; SNP, skin and nasal preparation.

Potential for resistance.

As with antibiotics, resistance to antiseptics (the ability of a bacterial strain to survive the use of an antiseptic that could previously eliminate that strain) can occur in bacteria because of intrinsic properties (e.g., biofilm formation, endospores, and expression of intrinsic mechanisms) or can be acquired via mutation or external genetic material (plasmids or transposons) (24, 48, 49). However, less is known about fungal or viral mechanisms of resistance to antiseptics (24, 48). Although there are no standard criteria for evaluating the capability of an antiseptic agent to induce or select for antibiotic resistance in bacteria, a protocol based on evaluating the change in susceptibility profile to the antiseptic and antibiotics has been proposed (50, 51). Based on available reports, no link has been observed between PVP-I and the development of resistance, probably due to its numerous and simultaneous molecular targets (e.g., double bonds, amino groups, and sulfydral groups) (23, 47, 52–56). To date, evidence suggests that PVP-I does not select for resistance among staphylococci (37) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Serratia marcescens, Escherichia coli, and Klebsiella aerogenes in vitro (28, 57) or among staphylococci after long-term clinical application to catheter exit sites (58). Isolated reports of slow bactericidal activity (27, 41) or apparent resistance to PVP-I (41, 59) are available, but they were later attributed to difficulties in determining its in vitro activity and/or the use of culture conditions antagonistic to its action (40). Furthermore, reports of intrinsic contamination of 10% PVP-I solution with Burkholderia (formerly Pseudomonas) cepacia were concerning when initially published in the 1980s and early 1990s (60–66) but were subsequently attributed to confounding factors in the manufacturing process (62). The occurrence of such phenomena has not been widely reproduced with PVP-I, and similar reports of contamination with other antiseptics were also published during this time period (53, 67). Finally, unlike other antiseptics, there have been no reports of PVP-I inducing horizontal gene transfer, antibiotic resistance genes, or cross-tolerance and cross-resistance to antibiotics and other antiseptics (20, 53).

Clinical evidence.

(i) Decolonization prior to surgery. Intranasal and topical PVP-I has been investigated in several studies for the preoperative decolonization of patients undergoing surgery. Four of these studies were prospective with a randomized controlled design (22, 68–70), and the remaining studies were retrospective database studies with historical controls (71–75). The main outcome measures were either S. aureus colonization status (68–70) or the prevention of SSI (22, 71–75). Current World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines for decolonization recommend intranasal mupirocin with or without chlorhexidine body wash in patients with known S. aureus carriage that are undergoing cardiothoracic or orthopedic surgery (1); patients undergoing other types of surgery with known S. aureus carriage should also be considered for decolonization with the same regimen (1). A summary of clinical studies investigating intranasal and topical PVP-I is presented in Table 2 (22, 68–75).

TABLE 2.

Summary of clinical studies investigating preoperative decolonization with intranasal or topical PVP-I for the prevention of SSIsa

| Treatment and reference | Study design | Patient population | No. of patients | Intervention | S. aureus colonization and SSI rateb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intranasal PVP-I | Postoperative nasal colonization | ||||

| Rezapoor et al. (68) | Randomized, placebo controlled | Orthopedic surgery | 34 | SNP of 5% PVP-I | 7 (21), P = 0.003, vs saline |

| 29 | Off-the-shelf 10% PVP-I | 15 (52) | |||

| 32 | Saline (placebo) | 19 (59) | |||

| SSI rate | |||||

| Bebko et al. (71) | Retrospective | Orthopedic surgery | 365 | Intranasal 5% PVP-I (morning of surgery) + 2% CHG wash + 0.12% oral rinse (night before and morning of surgery) versus historical control. | 4 (1.1), P = 0.02 vs historical control |

| 344 | Historical control (before introduction of decontamination protocol). | 13 (3.8) | |||

| Urias et al. (75) | Retrospective | Orthopedic surgery | 962 | Nasal painting with PVP-I skin and nasal antiseptic + CHG washcloth bath/CHG solution shower. | 2 (0.2) |

| 930 | CHG washcloth bath/CHG solution shower. | 10 (1.1) | |||

| Phillips et al. (22) | Prospective, open label, randomized | Orthopedic surgery | 842 | Two 30-s applications of 5% PVP-I solution into each nostril within 2 h of surgical incision + topical 2% CHG wipes. | 6 (NA), P = 0.1 vs mupirocin |

| 855 | 2% mupirocin ointment twice daily for the 5 days prior to surgery + topical 2% CHG wipes. | 14 (NA) | |||

| Torres et al. (74) | Retrospective | Orthopedic surgery | 1,004 | Universal treatment: two 30-s applications of 5% PVP-I solution into each nostril ∼1 h prior to surgical incision + CHG baths for 5 days before surgery + a topical CHG wipe preoperatively applied to the leg. | 8 (0.8) |

| 849 | Screening and treatment of MRSA-positive patients: intranasal mupirocin twice daily for 5 days prior to surgical incision + CHG baths for 5 days prior to surgical incision + a topical CHG wipe preoperatively applied to the leg. | 6 (0.8) | |||

| Topical PVP-I | Preoperative skin colonization | ||||

| Veiga et al. (69) | Prospective, randomized, controlled | Plastic surgery | 57 | Shower with liquid detergent–based 10% PVP-I 2 h before surgery. | 1, P = 0.0019 vs control |

| 57 | Control (no special instructions for showering were implemented before surgery). | 12 | |||

| SSI rate | |||||

| Ghobrial et al. (72) | Prospective database analysis | Spinal neurosurgery | 3,185 | 7.5% PVP-I | 33 (1.036), P = 0.728 vs CHG/IPA |

| 3,774 | 2% CHG and 70% IPA | 36 (0.954) | |||

| Raja et al. (73) | Retrospective | Cardiac surgery | 738 | Skin preparation with 10% PVP-I in 30% industrial methylated spirit | NA (3.8), P = 0.14 |

| 738 | Skin preparation with 2% CHG in 70% IPA | NA (3.3) |

CHG, chlorhexidine; PVP-I, povidone iodine; SNP, skin and nasal preparation; SSI, surgical site infection; IPA, isopropyl alcohol/isopropanol.

Colonization is expressed as the number of patients with a positive culture result (numbers in parentheses indicate % of patients); the SSI rate is expressed number (%).

(ii) Efficacy of intranasal PVP-I decolonization. One large randomized, placebo-controlled study evaluated the effects of intranasal PVP-I on nasal S. aureus colonization in patients undergoing orthopedic surgery (68). In this study, a single preoperative application of 5% PVP-I nasal solution eliminated nasal S. aureus in over two-thirds of patients at 4 h posttreatment, although an off-the-shelf preparation of 10% PVP-I solution was found to be less effective (68). In another randomized, placebo-controlled study, a single application of 10% PVP-I nasal preparation significantly reduced nasal MRSA at 1 and 6 h (P < 0.05); however, significant activity was not maintained at 12 and 24 h (P > 0.05) (70). Based on these results, the authors concluded that PVP-I may be effective for the short-term suppression of MRSA during surgery, and they proposed that this may be sufficient to reduce the risk of SSI (70). Of interest, the study demonstrated that repeated dosing with PVP-I every 12 h for 5 days did not enhance its efficacy, since there was no significant reduction in nasal MRSA with PVP-I compared to control (P > 0.05) (70).

Studies have also investigated the effect of intranasal PVP-I on the rate of SSI. In a retrospective database study, universal preoperative decontamination with intranasal PVP-I plus chlorhexidine wash and oral rinse significantly reduced the 30-day SSI rate versus historical controls in patients undergoing elective orthopedic surgery (1.1% versus 3.8% in controls; P = 0.02) (71). In another retrospective review, the addition of intranasal PVP-I to chlorhexidine wash also significantly reduced the SSI rate in trauma patients undergoing emergency orthopedic surgery compared to chlorhexidine alone (0.2% with chlorhexidine plus intranasal PVP-I versus 1.1% with chlorhexidine alone; P = 0.02) (Table 2) (75).

Compared to intranasal mupirocin, preoperative intranasal PVP-I was found to have similar efficacy in preventing SSI in patients undergoing orthopedic surgery, with or without screening for MRSA (Table 2) (22, 74). In an investigator-initiated, open-label, randomized study, 90-day deep SSI rates caused by any pathogen, including S. aureus, were similar with either intranasal PVP-I applied within 2 h of surgery or intranasal mupirocin given for 5 days before surgery with topical chlorhexidine (22). Likewise, in a retrospective study, the 90-day SSI rate was similar in patients treated with universal intranasal PVP-I 1 h before surgery compared to screening for MRSA followed by intranasal mupirocin for 5 days (with both groups also treated with chlorhexidine washes and a preoperative chlorhexidine wipe) (74). Alongside similar efficacy, patients treated with mupirocin were more likely to report headache, rhinorrhea, congestion, and sore throat than those treated with PVP-I, in which a single case of vasovagal reaction was reported (22). Overall, fewer patients (3.4%) rated their experience of treatment with nasal PVP-I solution treatment as unpleasant/very unpleasant compared to patients treated with intranasal mupirocin ointment (38.8%) (P < 0.0001) (76).

According to a U.S. cost-effectiveness model, universal preoperative decolonization with intranasal PVP-I in patients undergoing orthopedic surgery potentially saved $74.42 per patient compared to preoperative screening and treatment of MRSA-positive patients with a 5-day course of intranasal mupirocin (77). Other studies conducted in different settings led to a similar conclusion, i.e., systemic preoperative decolonization with PVP-I was more cost-effective than the standard MRSA screening protocol in orthopedic surgery, with no difference in infection rates (74, 78).

(iii) Efficacy of topical PVP-I decolonization. In a prospective study in patients undergoing elective plastic surgery, a preoperative shower with PVP-I significantly decreased presurgical staphylococcal skin colonization versus controls (P < 0.0019) (69). Furthermore, the efficacy of preoperative skin decontamination with topical 7.5 or 10% PVP-I was similar to that of topical 2% chlorhexidine in the prevention of SSI in patients undergoing spinal or cardiac surgery, respectively (Table 2) (72, 73).

(iv) Decolonization of health care professionals. In a study investigating the longer-term use of PVP-I in the ICU neonatal setting, intranasal PVP-I cream was applied to health care personnel three times per working day for 3 months. This procedure dramatically reduced the rate of nasal carriage of MRSA from 13.3% at baseline to 0% (79).

STATE OF THE ART AND PERSPECTIVES

Intranasal mupirocin and topical chlorhexidine are currently the preferred agents for the decolonization of S. aureus. However, the widespread use of mupirocin has led to resistance and treatment failures, and antibiotic resistance and the horizontal transfer of mobile antibiotic resistance elements following low-level exposure to chlorhexidine have also been reported (20, 80), highlighting the need for alternative treatment strategies.

PVP-I has several properties which make it an attractive option for S. aureus decolonization, including strong antistaphylococcal activity in in vitro and ex vivo models, and uniform activity against S. aureus regardless of the presence of antibiotic or antiseptic resistance (28, 39, 40, 42–44, 46). Of note, a lack of acquired bacterial resistance or cross-resistance to antibiotics or other antiseptics has been observed with PVP-I use (20, 23, 28, 37, 55–58). Furthermore, clinical trial data suggest that intranasal PVP-I demonstrates favorable efficacy in the preoperative decolonization of MRSA and prevention of SSI, compared with chlorhexidine and mupirocin (22, 71, 74). Table 3 summarizes the properties of PVP-I, chlorhexidine, and mupirocin (22, 23, 28, 37, 39, 40, 42–47, 57, 58, 71, 72, 81–101).

TABLE 3.

State of the art and perspectives: use of PVP-I, CHG, and mupirocin for the preoperative decolonization of MRSA and prevention of SSIsa

| Antiseptic | Spectrum of activity | Activity against MRSA and mupirocin-resistant S. aureus | Bacterial resistance | Efficacy in surgical site infections |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PVP-I | Broad spectrum, including Gram-positive bacteria, Gram-negative bacteria, actinobacteria, antiviral, antifungal, antiprotozoal, and antispore (23, 81) | • Biocidal against MSSA/MRSA within 15 to 60 s (39, 43, 45) |

• Very limited occurrence of the induction of iodine resistance (37, 57, 58) |

Preoperative intranasal PVP-I in orthopedic surgery: |

| • Active against S. aureus regardless of the presence of antibiotic or antiseptic resistance (28, 39, 40, 42–44, 46) | • Does not induce cross-resistance to antibiotics (57, 58) | • Significantly reduced 30-day SSI rate in combination with topical CHG (1.1%) vs controls (3.8%); P = 0.02 (71) | ||

| • Similar efficacy (6/842) to a 5-day course of intranasal mupirocin (14/855) in reducing 90-day deep SSI rate following surgery (fraction of surgeries with presence of deep SSI) (22) | ||||

| Chlorhexidine | Broad spectrum, including activity against Gram-positive bacteria and some Gram-negative bacteria and limited activity against fungi (e.g., yeasts) and enveloped viruses (81) | • Biocidal against MRSA within 2 to 30 min (45) |

• Several reports of the induction of CHG resistance but a low incidence in some studies (81, 84–90) |

Preoperative topical CHG in orthopedic surgery: |

| • Dual CHG and mupirocin-resistant MRSA rare but has been reported to cause decolonization failure (82) | • More common in MRSA than MSSA (91) | • 2% CHG no-rinse cloth reduced SSI rates from 3.19% to 1.59% when introduced into decolonization protocol in orthopedic surgery (93) | ||

| • One study found that in mupirocin-resistant MRSA, the rate of qacA/B gene was 65% and smr gene was 71% (83) | • Reports of cross-resistance to antibiotics (92) | • No significant difference in incidence of SSI between topical 2% CHG (36 [0.954%] of 3,774) and topical 7.5% PVP-I (33 [1.036%] of 3,185; P = 0.728) (72) | ||

| Mupirocin | Broad antibacterial spectrum, including some Gram-positive bacteria (staphylococci and streptococci) and some Gram-negative bacteria (Haemophilus influenzae, Neisseria spp., and Branhamella catarrhalis) (94) | Active against MRSA after 12 h (47) | • Several reports of resistance (95–99) |

Intranasal mupirocin in orthopedic surgery: |

| • No significant difference in SSI rate between nasal mupirocin (3.8%) and placebo (4.7%) (100) | ||||

| • High-level resistance (MIC ≥512 μg/ml) associated with treatment failure (95) | Intranasal mupirocin in other surgery (gynecologic, neurologic, or cardiothoracic surgery): | |||

| • Clinical significance of low-level resistance (MIC ≥8–256 μg/ml) unknown (95) | • No significant difference in S. aureus SSI rate between nasal mupirocin (2.3%) and placebo (2.4%) (101) |

CHG, chlorhexidine gluconate; MRSA, methicillin-resistant S. aureus; MSSA, methicillin-sensitive S. aureus; PVP-I, povidone iodine; qac, quaternary ammonium compound; smr, streptomycin resistance gene; SSI, surgical site infection.

Decolonization is most effective among patient populations who are at risk of infection for only a short period (13). As documented in the WHO guidelines (1), the strongest evidence for decolonization is among surgical patients to prevent postoperative SSIs, particularly those undergoing cardiac and orthopedic surgery (13). Overall, the clinical data published to date on intranasal PVP-I support its short-term use prior to orthopedic surgery. Its successful use in trauma patients undergoing emergency surgery within 24 h of admission is also notable, since the use of a 5-day regimen of mupirocin is not feasible in this setting (75). Recent data indicate that a single preoperative application of intranasal PVP-I may be enough for the short-term suppression of MRSA during the perioperative period (70). Therefore, repeated dosing with intranasal PVP-I after surgery in order to enhance or prolong its antimicrobial activity may not be necessary, although studies are required to investigate this further. A large, randomized, controlled clinical trial is currently recruiting patients in order to compare the efficacy and safety of alcohol-based solutions of 5% PVP-I and 2% chlorhexidine in reducing SSI after cardiac surgery (102). Such a study should help to address the paucity of data regarding preoperative decolonization with topical PVP-I versus chlorhexidine for the prevention of SSI in patients undergoing cardiac surgery. Moving forward, studies investigating PVP-I in other patient groups who are at an elevated risk of infection for short periods (e.g., ICU patients) would be of interest.

The management of MRSA colonization continues to evolve, and decolonization should not be considered in isolation. Other notable preventative measures include screening, contact isolation, environmental disinfection, and good hand hygiene practices. Usually, a collection of interventions works better than just one, and combined interventions can reduce infection rates by 40 to 60% (2). With this in mind, further research is required to define the best approaches for persistent carriers, as well as the efficacy of different decolonization strategies and protocols in both surgical and nonsurgical patients (1, 2, 13).

Despite the wealth of evidence obtained from different in vitro and ex vivo settings supporting the use of various concentrations of PVP-I (5, 7.5, and 10%), the selection of the most appropriate concentration of PVP-I for clinical use should be made on a case-by-case basis. One factor to consider that may guide selection is whether PVP-I is available in aqueous or alcoholic solution. For example, based on our clinical experience, we advocate 10% PVP-I in aqueous solution for use on mucous membranes, whereas we recommend 5% PVP-I in alcoholic solution for use on healthy skin before an invasive or surgical procedure. The final selection should be made by the treating physician, with the ultimate goal to select the concentration of PVP-I which will significantly reduce the bacterial load of the skin without causing issues with skin toxicity.

FUTURE AREAS OF RESEARCH WITH POVIDONE IODINE

Studies investigating the longer term effects of PVP-I (e.g., prevention of recolonization postsurgery and use in long-term-care facilities) are needed. We also recognized the paucity of information related to bacterial resistance to PVP-I. For this reason, studies examining the potential for bacterial resistance to PVP-I are also recommended, as well as studies to confirm the absence of an association between exposure to PVP-I and the selection of antibiotic resistance among recent clinical isolates.

Evidence suggests that PVP-I in combination with chlorhexidine may prove to be more effective in preoperative antisepsis than when either agent is used alone, a finding indicative of a possible synergistic effect between the two agents (103–105). Indeed, given the different mechanisms of action of PVP-I and chlorhexidine, there is good reason to believe that the disruptive action of chlorhexidine on the bacterial cell membrane may facilitate intracellular entry of PVP-I, thereby potentiating its antimicrobial efficacy (104). A synergistic effect with the use of two or more antimicrobials would provide the opportunity to reduce the dose of each respective antimicrobial, helping to further minimize possible adverse effects without sacrificing antimicrobial activity. Overall, there is a general absence of data relating to the possible synergistic actions of PVP-I in combination with other antiseptics or antibiotics, and this is an area of research that warrants further investigation.

Some studies suggest that PVP-I may have a shorter time to bacterial regrowth than other antiseptic agents (36, 68, 70, 106, 107). Although this is unlikely to be an issue for surgical patients, clinical studies are needed to understand the long-term dynamics of PVP-I. In the case of S. aureus, the bacterium is capable of invading nasal epithelial cells, which appears to protect it from host defense mechanisms (7). A better understanding of the role of the resulting intracellular reservoir of S. aureus during nasal colonization may lead to improved decolonization procedures. This is necessary since both mupirocin and chlorhexidine exhibit weak activity against intracellular S. aureus (108), and there are currently no data available for PVP-I.

CONCLUSIONS

Based on current evidence, PVP-I may be a useful preoperative decolonizing agent for the prevention of S. aureus infections, including MRSA and mupirocin-resistant strains. The broad spectrum of activity of PVP-I, encompassing viruses and fungi, and its reported activity against biofilm formation distinguish it from other antiseptics. However, compared to the current literature, additional experimental and clinical data are required to further evaluate the use of PVP-I in this setting.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Medical writing assistance in the preparation of this review article was provided by Jane Murphy and Jack Lassados (CircleScience, an Ashfield Company, part of UDG Healthcare plc). Writing/editorial support was funded by Meda Pharma S.p.A., a Mylan company.

D.L. has conflicts of interest with the following laboratories: Boston Industry, Mylan, Beckton Dickinson. J.Y.M. is currently Director of Biocide Consult, Ltd. A.S. and B.P. have no conflicts of interest to declare. All authors participated in a workshop on the topic of resistance and MRSA decolonization held in Paris in May 2019. This workshop was funded by Mylan, and travel and accommodations were paid.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization. 2016. Global guidelines for the prevention of surgical site infection. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Turner NA, Sharma-Kuinkel BK, Maskarinec SA, Eichenberger EM, Shah PP, Carugati M, Holland TL, Fowler VG Jr. 2019. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: an overview of basic and clinical research. Nat Rev Microbiol 17:203–218. doi: 10.1038/s41579-018-0147-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. 2017. Healthcare-associated infections: surgical site infections In ECDC: annual epidemiological report for 2015. ECDC, Stockholm, Sweden. [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Kraker ME, Wolkewitz M, Davey PG, Koller W, Berger J, Nagler J, Icket C, Kalenic S, Horvatic J, Seifert H, Kaasch AJ, Paniara O, Argyropoulou A, Bompola M, Smyth E, Skally M, Raglio A, Dumpis U, Kelmere AM, Borg M, Xuereb D, Ghita MC, Noble M, Kolman J, Grabljevec S, Turner D, Lansbury L, Grundmann H, BURDEN Study Group. 2011. Clinical impact of antimicrobial resistance in European hospitals: excess mortality and length of hospital stay related to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bloodstream infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 55:1598–1605. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01157-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leigh DA, Joy G. 1993. Treatment of familial staphylococcal infection–comparison of mupirocin nasal ointment and chlorhexidine/neomycin (Naseptin) cream in eradication of nasal carriage. J Antimicrob Chemother 31:909–917. doi: 10.1093/jac/31.6.909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ringberg H, Cathrine Petersson A, Walder M, Hugo Johansson PJ. 2006. The throat: an important site for MRSA colonization. Scand J Infect Dis 38:888–893. doi: 10.1080/00365540600740546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sakr A, Bregeon F, Mege JL, Rolain JM, Blin O. 2018. Staphylococcus aureus nasal colonization: an update on mechanisms, epidemiology, risk factors, and subsequent infections. Front Microbiol 9:2419. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Verhoeven PO, Gagnaire J, Botelho-Nevers E, Grattard F, Carricajo A, Lucht F, Pozzetto B, Berthelot P. 2014. Detection and clinical relevance of Staphylococcus aureus nasal carriage: an update. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 12:75–89. doi: 10.1586/14787210.2014.859985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wertheim HF, Melles DC, Vos MC, van Leeuwen W, van Belkum A, Verbrugh HA, Nouwen JL. 2005. The role of nasal carriage in Staphylococcus aureus infections. Lancet Infect Dis 5:751–762. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(05)70295-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kluytmans J, van Belkum A, Verbrugh H. 1997. Nasal carriage of Staphylococcus aureus: epidemiology, underlying mechanisms, and associated risks. Clin Microbiol Rev 10:505–520. doi: 10.1128/CMR.10.3.505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Datta R, Huang SS. 2008. Risk of infection and death due to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in long-term carriers. Clin Infect Dis 47:176–181. doi: 10.1086/589241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.von Eiff C, Becker K, Machka K, Stammer H, Peters G. 2001. Nasal carriage as a source of Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. N Engl J Med 344:11–16. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200101043440102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Septimus EJ, Schweizer ML. 2016. Decolonization in prevention of health care-associated infections. Clin Microbiol Rev 29:201–222. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00049-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Edgeworth JD. 2011. Has decolonization played a central role in the decline in UK methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus transmission? A focus on evidence from intensive care. J Antimicrob Chemother 66(Suppl 2):ii41–ii47. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkq325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Troeman DPR, Van Hout D, Kluytmans J. 2019. Antimicrobial approaches in the prevention of Staphylococcus aureus infections: a review. J Antimicrob Chemother 74:281–294. doi: 10.1093/jac/dky421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kock R, Becker K, Cookson B, van Gemert-Pijnen JE, Harbarth S, Kluytmans J, Mielke M, Peters G, Skov RL, Struelens MJ, Tacconelli E, Witte W, Friedrich AW. 2014. Systematic literature analysis and review of targeted preventive measures to limit healthcare-associated infections by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Euro Surveill 19:20860. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.es2014.19.29.20860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Poovelikunnel T, Gethin G, Humphreys H. 2015. Mupirocin resistance: clinical implications and potential alternatives for the eradication of MRSA. J Antimicrob Chemother 70:2681–2692. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkv169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Williamson DA, Carter GP, Howden BP. 2017. Current and emerging topical antibacterials and antiseptics: agents, action, and resistance patterns. Clin Microbiol Rev 30:827–860. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00112-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Horner C, Mawer D, Wilcox M. 2012. Reduced susceptibility to chlorhexidine in staphylococci: is it increasing and does it matter? J Antimicrob Chemother 67:2547–2559. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kampf G. 2018. Biocidal agents used for disinfection can enhance antibiotic resistance in Gram-negative species. Antibiotics (Basel) 7:110. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics7040110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Septimus EJ. 2019. Nasal decolonization: what antimicrobials are most effective prior to surgery? Am J Infect Control 47s:A53–A57. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2019.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Phillips M, Rosenberg A, Shopsin B, Cuff G, Skeete F, Foti A, Kraemer K, Inglima K, Press R, Bosco J. 2014. Preventing surgical site infections: a randomized, open-label trial of nasal mupirocin ointment and nasal povidone-iodine solution. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 35:826–832. doi: 10.1086/676872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lachapelle J-M, Castel O, Casado AF, Leroy B, Micali G, Tennstedt D, Lambert J. 2013. Antiseptics in the era of bacterial resistance: a focus on povidone iodine. Clin Pract 10:579–592. doi: 10.2217/cpr.13.50. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McDonnell G, Russell AD. 2001. Antiseptics and disinfectants: activity, action, and resistance Clin Microbiol Rev 12:147–179. doi: 10.1128/CMR.12.1.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rackur H. 1985. New aspects of mechanism of action of povidone-iodine. J Hosp Infect 6(Suppl A):13–23. doi: 10.1016/s0195-6701(85)80041-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gottardi W. 1983. Potentiometrische Bestimmung der Gleichgewichtskonzentrationen an freiem und komplex gebundenem Iod in Wässrigen Lösungen von Polyvinylpyrrolidon-Iod (PVP-Iod). Z Anal Chem 314:582–585. doi: 10.1007/BF00474852. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Berkelman RL, Holland BW, Anderson RL. 1982. Increased bactericidal activity of dilute preparations of povidone-iodine solutions. J Clin Microbiol 15:635–639. doi: 10.1128/JCM.15.4.635-639.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kunisada T, Yamada K, Oda S, Hara O. 1997. Investigation on the efficacy of povidone-iodine against antiseptic-resistant species. Dermatology 195(Suppl 2):14–18. doi: 10.1159/000246025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yasuda T, Yoshimura Y, Takada H, Kawaguchi S, Ito M, Yamazaki F, Iriyama J, Ishigo S, Asano Y. 1997. Comparison of bactericidal effects of commonly used antiseptics against pathogens causing nosocomial infections: part 2. Dermatology 195(Suppl 2):19–28. doi: 10.1159/000246026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kawana R, Kitamura T, Nakagomi O, Matsumoto I, Arita M, Yoshihara N, Yanagi K, Yamada A, Morita O, Yoshida Y, Furuya Y, Chiba S. 1997. Inactivation of human viruses by povidone-iodine in comparison with other antiseptics. Dermatology 195(Suppl 2):29–35. doi: 10.1159/000246027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wutzler P, Sauerbrei A, Klocking R, Brogmann B, Reimer K. 2002. Virucidal activity and cytotoxicity of the liposomal formulation of povidone-iodine. Antiviral Res 54:89–97. doi: 10.1016/s0166-3542(01)00213-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hoekstra MJ, Westgate SJ, Mueller S. 2017. Povidone-iodine ointment demonstrates in vitro efficacy against biofilm formation. Int Wound J 14:172–179. doi: 10.1111/iwj.12578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oduwole KO, Glynn AA, Molony DC, Murray D, Rowe S, Holland LM, McCormack DJ, O’Gara JP. 2010. Anti-biofilm activity of subinhibitory povidone-iodine concentrations against Staphylococcus epidermidis and Staphylococcus aureus. J Orthop Res 28:1252–1256. doi: 10.1002/jor.21110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johani K, Malone M, Jensen SO, Dickson HG, Gosbell IB, Hu H, Yang Q, Schultz G, Vickery K. 2018. Evaluation of short exposure times of antimicrobial wound solutions against microbial biofilms: from in vitro to in vivo. J Antimicrob Chemother 73:494–502. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkx391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Capriotti K, Pelletier J, Barone S, Capriotti J. 2018. Efficacy of dilute povidone-iodine against multidrug resistant bacterial biofilms, fungal biofilms and fungal spores. Clin Res Dermatol Open Access 5:1–5. doi: 10.15226/2378-1726/5/1/00174. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Anderson MJ, Scholz MT, Parks PJ, Peterson ML. 2013. Ex vivo porcine vaginal mucosal model of infection for determining effectiveness and toxicity of antiseptics. J Appl Microbiol 115:679–688. doi: 10.1111/jam.12277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lacey RW, Catto A. 1993. Action of povidone-iodine against methicillin-sensitive and -resistant cultures of Staphylococcus aureus. Postgrad Med J 69(Suppl 3):S78–S83. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gottardi W. 1981. The formation of iodate as a reason for the decrease of efficiency of iodine containing disinfectants. Zentralbl Bakteriol Mikrobiol Hyg B 172:498–507. (Author’s translation.) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Haley CE, Marling-Cason M, Smith JW, Luby JP, Mackowiak PA. 1985. Bactericidal activity of antiseptics against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Clin Microbiol 21:991–992. doi: 10.1128/JCM.21.6.991-992.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hill RL, Casewell MW. 2000. The in vitro activity of povidone-iodine cream against Staphylococcus aureus and its bioavailability in nasal secretions. J Hosp Infect 45:198–205. doi: 10.1053/jhin.2000.0733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gocke DJ, Ponticas S, Pollack W. 1985. In vitro studies of the killing of clinical isolates by povidone-iodine solutions. J Hosp Infect 6(Suppl A):59–66. doi: 10.1016/s0195-6701(85)80047-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cichos KH, Andrews RM, Wolschendorf F, Narmore W, Mabry SE, Ghanem ES. 2019. Efficacy of intraoperative antiseptic techniques in the prevention of periprosthetic joint infection: superiority of betadine. J Arthroplasty 34:S312–S318. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2019.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Goldenheim PD. 1993. In vitro efficacy of povidone-iodine solution and cream against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Postgrad Med J 69(Suppl 3):S62–S65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McLure AR, Gordon J. 1992. In vitro evaluation of povidone-iodine and chlorhexidine against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Hosp Infect 21:291–299. doi: 10.1016/0195-6701(92)90139-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yasuda T, Yoshimura S, Katsuno Y, Takada H, Ito M, Takahashi M, Yahazaki F, Iriyama J, Ishigo S, Asano Y. 1993. Comparison of bactericidal activities of various disinfectants against methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Postgrad Med J 69(Suppl 3):S66–S69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Block C, Robenshtok E, Simhon A, Shapiro M. 2000. Evaluation of chlorhexidine and povidone iodine activity against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecalis using a surface test. J Hosp Infect 46:147–152. doi: 10.1053/jhin.2000.0805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Anderson MJ, David ML, Scholz M, Bull SJ, Morse D, Hulse-Stevens M, Peterson ML. 2015. Efficacy of skin and nasal povidone-iodine preparation against mupirocin-resistant methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and S. aureus within the anterior nares. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:2765–2773. doi: 10.1128/AAC.04624-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Maillard JY. 2005. Antimicrobial biocides in the healthcare environment: efficacy, usage, policies, and perceived problems. Ther Clin Risk Manag 1:307–320. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Leggett MJ, McDonnell G, Denyer SP, Setlow P, Maillard JY. 2012. Bacterial spore structures and their protective role in biocide resistance. J Appl Microbiol 113:485–498. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2012.05336.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Maillard JY, Bloomfield S, Coelho JR, Collier P, Cookson B, Fanning S, Hill A, Hartemann P, McBain AJ, Oggioni M, Sattar S, Schweizer HP, Threlfall J. 2013. Does microbicide use in consumer products promote antimicrobial resistance? A critical review and recommendations for a cohesive approach to risk assessment. Microb Drug Resist 19:344–354. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2013.0039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wesgate R, Grasha P, Maillard JY. 2016. Use of a predictive protocol to measure the antimicrobial resistance risks associated with biocidal product usage. Am J Infect Control 44:458–464. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2015.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Uchiyama S, Dahesh S, Nizet V, Kessler J. 2019. Enhanced topical delivery of non-complexed molecular iodine for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus decolonization. Int J Pharm 554:81–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2018.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bigliardi PL, Alsagoff SAL, El-Kafrawi HY, Pyon JK, Wa CTC, Villa MA. 2017. Povidone iodine in wound healing: a review of current concepts and practices. Int J Surg 44:260–268. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2017.06.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schreier H, Erdos G, Reimer K, Konig B, Konig W, Fleischer W. 1997. Molecular effects of povidone-iodine on relevant microorganisms: an electron-microscopic and biochemical study. Dermatology 195(Suppl 2):111–116. doi: 10.1159/000246043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Eggers M. 2019. Infectious disease management and control with povidone iodine. Infect Dis Ther 8:581–593. doi: 10.1007/s40121-019-00260-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fleischer W, Reimer K. 1997. Povidone-iodine in antisepsis: state of the art. Dermatology 195(Suppl 2):3–9. doi: 10.1159/000246022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Houang ET, Gilmore OJ, Reid C, Shaw EJ. 1976. Absence of bacterial resistance to povidone iodine. J Clin Pathol 29:752–755. doi: 10.1136/jcp.29.8.752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lanker Klossner B, Widmer HR, Frey F. 1997. Nondevelopment of resistance by bacteria during hospital use of povidone-iodine. Dermatology 195(Suppl 2):10–13. doi: 10.1159/000246024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mycock G. 1985. Methicillin/antiseptic-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Lancet 2:949–950. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(85)90881-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Anderson RL. 1989. Iodophor antiseptics: intrinsic microbial contamination with resistant bacteria. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 10:443–446. doi: 10.1086/645918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Anderson RL, Vess RW, Carr JH, Bond WW, Panlilio AL, Favero MS. 1991. Investigations of intrinsic Pseudomonas cepacia contamination in commercially manufactured povidone-iodine. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 12:297–302. doi: 10.1086/646342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Anderson RL, Vess RW, Panlilio AL, Favero MS. 1990. Prolonged survival of Pseudomonas cepacia in commercially manufactured povidone-iodine. Appl Environ Microbiol 56:3598–3600. doi: 10.1128/AEM.56.11.3598-3600.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Anonymous. 1989. Contaminated povidone-iodine solution–Texas. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 38:133–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Berkelman RL, Lewin S, Allen JR, Anderson RL, Budnick LD, Shapiro S, Friedman SM, Nicholas P, Holzman RS, Haley RW. 1981. Pseudobacteremia attributed to contamination of povidone-iodine with Pseudomonas cepacia. Ann Intern Med 95:32–36. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-95-1-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Craven DE, Moody B, Connolly MG, Kollisch NR, Stottmeier KD, McCabe WR. 1981. Pseudobacteremia caused by povidone-iodine solution contaminated with Pseudomonas cepacia. N Engl J Med 305:621–623. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198109103051106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Panlilio AL, Beck-Sague CM, Siegel JD, Anderson RL, Yetts SY, Clark NC, Duer PN, Thomassen KA, Vess RW, Hill BC. 1992. Infections and pseudoinfections due to povidone-iodine solution contaminated with Pseudomonas cepacia. Clin Infect Dis 14:1078–1083. doi: 10.1093/clinids/14.5.1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Marrie TJ, Costerton JW. 1981. Prolonged survival of Serratia marcescens in chlorhexidine. Appl Environ Microbiol 42:1093–1102. doi: 10.1128/AEM.42.6.1093-1102.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rezapoor M, Nicholson T, Tabatabaee RM, Chen AF, Maltenfort MG, Parvizi J. 2017. Povidone-iodine-based solutions for decolonization of nasal Staphylococcus aureus: a randomized, prospective, placebo-controlled study. J Arthroplasty 32:2815–2819. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2017.04.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Veiga DF, Damasceno CA, Veiga Filho J, Silva RV Jr, Cordeiro DL, Vieira AM, Andrade CH, Ferreira LM. 2008. Influence of povidone-iodine preoperative showers on skin colonization in elective plastic surgery procedures. Plast Reconstr Surg 121:115–118. (Discussion, 119–120.) doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000293861.02825.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ghaddara HA, Kumar JA, Cadnum JL, Ng-Wong YK, Donskey CJ. 2020. Efficacy of a povidone iodine preparation in reducing nasal methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in colonized patients. Am J Infect Control 48:456–459. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2019.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bebko SP, Green DM, Awad SS. 2015. Effect of a preoperative decontamination protocol on surgical site infections in patients undergoing elective orthopedic surgery with hardware implantation. JAMA Surg 150:390–395. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2014.3480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ghobrial GM, Wang MY, Green BA, Levene HB, Manzano G, Vanni S, Starke RM, Jimsheleishvili G, Crandall KM, Dididze M, Levi AD. 2018. Preoperative skin antisepsis with chlorhexidine gluconate versus povidone-iodine: a prospective analysis of 6959 consecutive spinal surgery patients. J Neurosurg Spine 28:209–214. doi: 10.3171/2017.5.SPINE17158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Raja SG, Rochon M, Mullins C, Morais C, Kourliouros A, Wishart E, De Souza A, Bhudia S. 2018. Impact of choice of skin preparation solution in cardiac surgery on rate of surgical site infection: a propensity score matched analysis. J Infect Prev 19:16–21. doi: 10.1177/1757177417722045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Torres EG, Lindmair-Snell JM, Langan JW, Burnikel BG. 2016. Is preoperative nasal povidone-iodine as efficient and cost-effective as standard methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus screening protocol in total joint arthroplasty? J Arthroplasty 31:215–218. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2015.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Urias DS, Varghese M, Simunich T, Morrissey S, Dumire R. 2018. Preoperative decolonization to reduce infections in urgent lower extremity repairs. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg 44:787–793. doi: 10.1007/s00068-017-0896-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Maslow J, Hutzler L, Cuff G, Rosenberg A, Phillips M, Bosco J. 2014. Patient experience with mupirocin or povidone-iodine nasal decolonization. Orthopedics 37:e576–e581. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20140528-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rieser GR, Moskal JT. 2018. Cost efficacy of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus decolonization with intranasal povidone-iodine. J Arthroplasty 33:1652–1655. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2018.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Peng HM, Wang LC, Zhai JL, Weng XS, Feng B, Wang W. 2017. Effectiveness of preoperative decolonization with nasal povidone iodine in Chinese patients undergoing elective orthopedic surgery: a prospective cross-sectional study. Braz J Med Biol Res 51:e6736. doi: 10.1590/1414-431X20176736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Masano H, Fukuchi K, Wakuta R, Tanaka Y. 1993. Efficacy of intranasal application of povidone-iodine cream in eradicating nasal methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) staff. Postgrad Med J 69(Suppl 3):S122–S125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Jutkina J, Marathe NP, Flach CF, Larsson D. 2018. Antibiotics and common antibacterial biocides stimulate horizontal transfer of resistance at low concentrations. Sci Total Environ 616–617:172–178. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.10.312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sakr A, Bregeon F, Rolain JM, Blin O. 2019. Staphylococcus aureus nasal decolonization strategies: a review. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 17:327–340. doi: 10.1080/14787210.2019.1604220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lee AS, Macedo-Vinas M, Francois P, Renzi G, Schrenzel J, Vernaz N, Pittet D, Harbarth S. 2011. Impact of combined low-level mupirocin and genotypic chlorhexidine resistance on persistent methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus carriage after decolonization therapy: a case-control study. Clin Infect Dis 52:1422–1430. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lee H, Lim H, Bae IK, Yong D, Jeong SH, Lee K, Chong Y. 2013. Coexistence of mupirocin and antiseptic resistance in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates from Korea. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 75:308–312. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2012.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Vali L, Dashti AA, Mathew F, Udo EE. 2017. Characterization of heterogeneous MRSA and MSSA with reduced susceptibility to chlorhexidine in Kuwaiti hospitals. Front Microbiol 8:1359. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Htun HL, Hon PY, Holden MTG, Ang B, Chow A. 2019. Chlorhexidine and octenidine use, qac gene carriage, and reduced antiseptic susceptibility in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates from a healthcare network. Clin Microbiol Infect 25:1154.e1151–1154.e1157. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2018.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Prag G, Falk-Brynhildsen K, Jacobsson S, Hellmark B, Unemo M, Söderquist B. 2014. Decreased susceptibility to chlorhexidine and prevalence of disinfectant resistance genes among clinical isolates of Staphylococcus epidermidis. APMIS 122:961–967. doi: 10.1111/apm.12239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hijazi K, Mukhopadhya I, Abbott F, Milne K, Al-Jabri ZJ, Oggioni MR, Gould IM. 2016. Susceptibility to chlorhexidine amongst multidrug-resistant clinical isolates of Staphylococcus epidermidis from bloodstream infections. Int J Antimicrob Agents 48:86–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2016.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Gomaa FAM, Helal ZH, Khan MI. 2017. High Prevalence of blaNDM-1, blaVIM, qacE, and qacEΔ1 genes and their association with decreased susceptibility to antibiotics and common hospital biocides in clinical isolates of Acinetobacter baumannii. Microorganisms 5:18. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms5020018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Cheng A, Sun HY, Tsai YT, Wu UI, Chuang YC, Wang JT, Sheng WH, Hsueh PR, Chen YC, Chang SC. 2017. In vitro evaluation of povidone-iodine and chlorhexidine against outbreak and nonoutbreak strains of Mycobacterium abscessus using standard quantitative suspension and carrier testing. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 62:e01364-17. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01364-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Alotaibi SMI, Ayibiekea A, Pedersen AF, Jakobsen L, Pinholt M, Gumpert H, Hammerum AM, Westh H, Ingmer H. 2017. Susceptibility of vancomycin-resistant and -sensitive Enterococcus faecium obtained from Danish hospitals to benzalkonium chloride, chlorhexidine, and hydrogen peroxide biocides. J Med Microbiol 66:1744–1751. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.000642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hardy K, Sunnucks K, Gil H, Shabir S, Trampari E, Hawkey P, Webber M. 2018. Increased usage of antiseptics is associated with reduced susceptibility in clinical isolates of Staphylococcus aureus. mBio 9:e00894-18. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00894-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Wand ME, Bock LJ, Bonney LC, Sutton JM. 2017. Mechanisms of increased resistance to chlorhexidine and cross-resistance to colistin following exposure of Klebsiella pneumoniae clinical isolates to chlorhexidine. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 61:e01162-16. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01162-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Eiselt D. 2009. Presurgical skin preparation with a novel 2% chlorhexidine gluconate cloth reduces rates of surgical site infection in orthopaedic surgical patients. Orthop Nurs 28:141–145. doi: 10.1097/NOR.0b013e3181a469db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Sutherland R, Boon RJ, Griffin KE, Masters PJ, Slocombe B, White AR. 1985. Antibacterial activity of mupirocin (pseudomonic acid), a new antibiotic for topical use. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 27:495–498. doi: 10.1128/aac.27.4.495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Patel JB, Gorwitz RJ, Jernigan JA. 2009. Mupirocin resistance. Clin Infect Dis 49:935–941. doi: 10.1086/605495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Walker ES, Vasquez JE, Dula R, Bullock H, Sarubbi FA. 2003. Mupirocin-resistant, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: does mupirocin remain effective? Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 24:342–346. doi: 10.1086/502218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Fritz SA, Hogan PG, Camins BC, Ainsworth AJ, Patrick C, Martin MS, Krauss MJ, Rodriguez M, Burnham CA. 2013. Mupirocin and chlorhexidine resistance in Staphylococcus aureus in patients with community-onset skin and soft tissue infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:559–568. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01633-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Miller MA, Dascal A, Portnoy J, Mendelson J. 1996. Development of mupirocin resistance among methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus after widespread use of nasal mupirocin ointment. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 17:811–813. doi: 10.1086/647242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Caffrey AR, Quilliam BJ, LaPlante KL. 2010. Risk factors associated with mupirocin resistance in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Hosp Infect 76:206–210. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2010.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kalmeijer MD, Coertjens H, van Nieuwland-Bollen PM, Bogaers-Hofman D, de Baere GA, Stuurman A, van Belkum A, Kluytmans JA. 2002. Surgical site infections in orthopedic surgery: the effect of mupirocin nasal ointment in a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Clin Infect Dis 35:353–358. doi: 10.1086/341025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Perl TM, Cullen JJ, Wenzel RP, Zimmerman MB, Pfaller MA, Sheppard D, Twombley J, French PP, Herwaldt LA, Mupirocin and the Risk of Staphylococcus aureus Study Team. 2002. Intranasal mupirocin to prevent postoperative Staphylococcus aureus infections. N Engl J Med 346:1871–1877. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa003069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Boisson M, Corbi P, Kerforne T, Camilleri L, Debauchez M, Demondion P, Eljezi V, Flecher E, Lepelletier D, Leprince P, Nesseler N, Nizou JY, Roussel JC, Rozec B, Ruckly S, Lucet JC, Timsit JF, Mimoz O. 2019. Multicentre, open-label, randomised, controlled clinical trial comparing 2% chlorhexidine-70% isopropanol and 5% povidone iodine-69% ethanol for skin antisepsis in reducing surgical-site infection after cardiac surgery: the CLEAN 2 study protocol. BMJ Open 9:e026929. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-026929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Guzel A, Ozekinci T, Ozkan U, Celik Y, Ceviz A, Belen D. 2009. Evaluation of the skin flora after chlorhexidine and povidone-iodine preparation in neurosurgical practice. Surg Neurol 71:207–210. doi: 10.1016/j.surneu.2007.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Davies BM, Patel HC. 2016. Systematic review and meta-analysis of preoperative antisepsis with combination chlorhexidine and povidone-iodine. Surg J 2:e70–e77. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1587691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Davies BM, Patel HC. 2016. Does chlorhexidine and povidone-iodine preoperative antisepsis reduce surgical site infection in cranial neurosurgery. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 98:405–408. doi: 10.1308/rcsann.2016.0143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Fuursted K, Hjort A, Knudsen L. 1997. Evaluation of bactericidal activity and lag of regrowth (postantibiotic effect) of five antiseptics on nine bacterial pathogens. J Antimicrob Chemother 40:221–226. doi: 10.1093/jac/40.2.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Smylie HG, Logie JR, Smith G. 1973. From Phisohex to Hibiscrub. Br Med J 4:586–589. doi: 10.1136/bmj.4.5892.586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Rigaill J, Morgene MF, Gavid M, Lelonge Y, He Z, Carricajo A, Grattard F, Pozzetto B, Berthelot P, Botelho-Nevers E, Verhoeven PO. 2018. Intracellular activity of antimicrobial compounds used for Staphylococcus aureus nasal decolonization. J Antimicrob Chemother 73:3044–3048. doi: 10.1093/jac/dky318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]