However, as bad as things were, the worst was yet to come, for germs would kill more people than bullets. 1

CRISIS DEFINED

A crisis is defined as a critical turning point, a time of intense difficulty, or danger when an associated important decision is made to protect individuals from harm and save lives. Indeed, in their book Theorizing Crisis Communication, professors Timothy Sellnow and Matthew Seeger outline over 2 dozen typologies of crisis. They assert that a crisis poses a significant threat to high priority goals such as life, property, security, health, and psychological stability.2 Collectively, the threats to high priority goals create anxiety and stress, and often require some immediate action by leaders in response to the crisis to limit and contain harm.

Clear communication by leaders during a crisis is essential to limit harm and ultimately resolve the crisis. General axioms of crisis communication include preparation, communication plan development, and coordination of message through designated personnel.3 However, even in the best cases, critical information can be lost in communication and consequently place lives at risk.

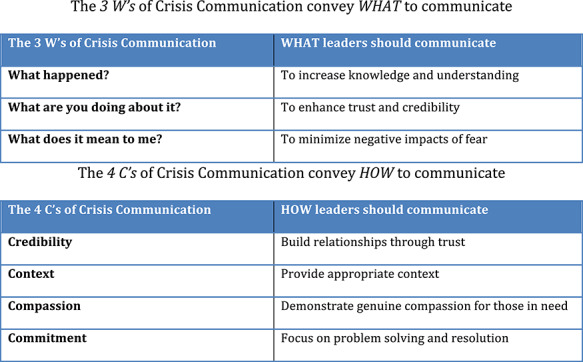

The consideration of “what to communicate and how to communicate” during a crisis using lessons learned from the Ebola outbreak as well as lessons now emerging from the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic is the focus of this perspective. This perspective offers practical guidelines for leaders identified here as the 3 W’s and 4C’s of crisis communication. These factors offer a checklist to be readily applied in a crisis, as well as in training for crisis response.

INTRODUCTION

Thomas Eric Duncan died at Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital on October 8, 2014. He was admitted with Ebola. Two nurses, Nina Pham and Amber Vinson, cared for Mr Duncan at the Dallas hospital, and they were each diagnosed with Ebola days later. Both nurses survived Ebola.4 However, as Americans learned more about the disease, the nurses’ ordeal highlighted the severe global threat of Ebola. The disease claimed over 4,000 lives and provided the professional health community many lessons, including how to communicate during a crisis. At the time of this writing, over 247,000 individuals have died, worldwide, of the coronavirus in the COVID-19 pandemic.5 This perspective borrows lessons learned from the Ebola outbreak to serve as a practical guide for leaders facing the COVID-19 challenge. It has implications for leaders who must communicate during a wide range of crises. The perspective focuses on “what” and "how” to communicate.

BACKGROUND

In July 2015, the Economic Community of West African States, Kofi Annan International Peacekeeping Training Centre and the Republic of Ghana National Disaster Management Organization, supported by the U.S. Africa Command Operation United Assistance Transition Disaster Preparedness Project, successfully launched the West Africa Disaster Preparedness Initiative in Accra, Ghana.6

In my role as a Defense Institute for Medical Operations instructor, I had the privilege to develop a curriculum and teach the Crisis Communication module to the Togo and Senegal delegations. As part of the West Africa Disaster Preparedness Initiative, we also helped facilitate an Ebola Awareness Course with my medical colleagues from the U.S. Army, the U.S. Air Force, and local experts. Indeed, the experience was especially rewarding, and the exchange of knowledge exceptional.

Accordingly, a framework consisting of 3 elements, called the 3W’s (described below), emerged from this experience. Utilizing this framework can provide societal confidence in both those who are engaged in communicating, as well as in the quality and accuracy of what they communicate. This is critical, for, among other reasons, to avoid conspiracy theories and the misbehavior they induce. As Kate Pine, an Assistant Professor of Health Solutions at the University of Arizona, explains, “When frightened, [as they are in a Pandemic] people believe implausible lies that give order to their lives. When they feel like they are inundated with information but don’t have the information they want [or trust], they will believe [and in some cases act on] outlandish falsehoods”.7

What to Communicate During a Crisis

Crisis communication ideally begins well before needed with a plan. This observation was made clear by Turner during his years of study and essential work on the origin of disasters.8 Thus, having clear objectives as to what to communicate is essential. Three fundamental goals during crisis communication include:

To increase knowledge and understanding

To enhance trust and credibility

To minimize the negative impacts of fear and concern

During the initial Ebola outbreak in West Africa, officials attempted to increase knowledge and understanding of the epidemic, build trust within the affected communities, and minimize the negative impacts of fear and concern, particularly as so many lives were being lost. In a crisis, the goal of reducing the adverse effects of the situation should guide communication and focus a team’s attention. Understanding the 3W’s can help leaders direct, precisely, what to communicate during a crisis. The 3W’s consist of the following:

What happened?

What are you doing about it?

What does it mean to me?

In crisis communication, these 3 questions guide “what to communicate” to individuals that are impacted by the crisis. As illustrated in Figure 1, each question should be answered adequately within the context of providing information to guide constructive action, minimize the negative impact of fear, and, ultimately, ameliorate the adverse consequences of the crisis.

Figure 1.

The 3 W’s of Crisis Communication convey WHAT to communicate. The 4 C’s of Crisis Communication convey HOW to communicate.

On March 24, 2014, at the very beginning of the recent Ebola outbreak, the World Health Organization (WHO) issued news about the Ebola virus disease in Guinea. The communication outlined what happened: 86 cases and 50 deaths with a case fatality risk (CFR) of 68.5% were recorded impacting 4 districts of Guinea, including Guekedou, Macenta, Nzerekore, and Kissidougou. The communication also outlined what the WHO and local officials were doing about the outbreak: The Minister of Health with the WHO and other agencies activated national and district management committees to coordinate a response to address the outbreak. The coordinated response included the deployment of multidisciplinary teams to the field to search for and manage cases actively; perform trace and follow-up contacts, and to sensitize affected communities on outbreak prevention and control of Ebola spread.

Additionally, Doctors Without Borders (Médecins Sans Frontières), Switzerland (MSF-CH) began work in the affected areas to assist with the establishment of isolation facilities and support the transport of biological samples from suspected cases and contacts for urgent testing. Finally, the communication conveyed what the Ebola outbreak meant to individuals locally impacted and throughout the world: The Ministry of Health in Guinea advised the public to take necessary measures to avert the spread of the disease and to report any suspected cases.9

In the ensuing weeks to months after the first reported cases of Ebola in Guinea, the WHO and other agencies continued to deliver communications about the crisis. The WHO and Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), in particular, regularly highlighted the 3W’s of “what” was happening, “what” was being done, and “what” the crisis meant to individuals. Since the initial 2014 reports in Guinea, thousands of individuals, including members of the U.S. military and billions of dollars in resources were mobilized to address the outbreak, contain the spread of Ebola, and treat individuals that were directly impacted by the deadly virus.10

For leaders, the 3W’s provide a practical framework and checklist for rapidly and effectively communicating during a crisis. In the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, it was imperative to first recognize the problem, even with incomplete information, and incumbent on leaders to know what to say so that an effective response could be developed. Once COVID-19 was identified as a global pandemic in early March 2020, by the WHO, leaders had to alert constituents as to what happened or was still happening, what was being done, and what COVID-19 meant in the context of their workplaces, hospitals, and communities. Leaders had to rapidly communicate their plans for how the immediate threat of COVID-19 would be addressed to mitigate the negative impact of the pandemic and save lives.

The 3W’s framework can also be used by healthcare leaders to communicate the increased threat of COVID-19 and its inherent danger over other infections. In such situations, designated hospital leaders must describe to hospital staff and patients what is occurring both medically and epidemiologically and explain what is required in terms of active and preventive measures that need to be implemented. This is especially the case when steps above and beyond standard hospital procedures are needed to contain the spread of infection (ie, masks for patients and staff, body temperature screening before entry to hospitals, and limiting patient visitation).

How to Communicate During a Crisis

In a crisis, particularly as first events evolve, all of the information may not be available for leaders and designated individuals responsible for communication. The Ebola outbreak and COVID-19 pandemic especially illustrate this point, and the lessons learned from this phenomenon are instructive for all leaders. Initial communication during the Ebola crisis aimed to achieve the overarching objectives of increasing knowledge and understanding and minimize the negative impact of fear and concern by helping the public understand the immediate risks of the disease, despite incomplete information. Likewise, COVID-19 has initially proven enigmatic in its spread, presentation, and response to therapy.

Thus, the most effective communication by leaders during both crises instruct individuals to take protective actions and aimed to help prevent casualties and support overall response efforts. Effective communication is achieved by knowing the 4C’s, and these principles can help direct individuals “how” to communicate during a crisis. The 4C’s include:

Credibility

Context

Compassion

Commitment

Michelle Gielan, a former CBS news anchor, observed during her years of coverage how a crisis could leave viewers paralyzed and encouraged the use of “the four C’s” framework when delivering bad news.11 In healthcare environments, particularly when information is incomplete, a response can be delayed. A crisis can often paralyze the appropriate response to the situation. Following the recognition of a crisis, communication is the essential critical next step that leads to an appropriate response and resolution of the crisis. Therefore, knowing how to communicate is as important as knowing what to communicate. Employing the 4C’s of credibility, context, compassion, and commitment ensures the crisis communicator delivers a compelling message that yields the best response when it is needed most, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Credibility

Officials from the CDC, MSF, and WHO slowly engendered trust and credibility during the Ebola outbreak by leveraging the social capital resources of information, relationships, goodwill, and cooperation. The task was difficult. The WHO, for example, encountered many challenges as they communicated about the Ebola outbreak. Indeed, there was a global lack of acceptance that Ebola was real. The WHO and others had to adopt a method of communication that was caring and understanding, and that would build trust over time. In some West African regions impacted by Ebola, it was recognized early that cultural rituals of burial included washing corpses without barrier protection, potentially exacerbating the spread of Ebola to others. This practice, coupled with an inherent distrust of outsiders, fear, superstition, and stigma, required delicate communication that was empathetic and sensitive to local cultural factors.

Leaders and individual team members also build relationships by sharing information, goodwill, and cooperation. The trust that emerges from these behaviors is a widely recognized foundational principle of ethically effective leadership.12 This process takes time, and these social capital resources engender trust and credibility and become important during crisis communication. To communicate with credibility, leaders may require expertise. In this respect, the novelty of COVID-19 presents a challenge as expertise, experience, and data are limited. Thus, leaders should enlist the help of experts when their own experience and expertise are limited.

Context

In October 2014, as the first case of Ebola was reported in Texas, there was public anxiety in the United States that the outbreak would spread rapidly, and some called for the government to close airports to travelers from West Africa.13 However, despite the pervasive fear and concern that existed, the CDC and others were careful to effectively communicate a message during the crisis that provided context so that the appropriate response and resolution could be obtained to combat the Ebola outbreak. Officials needed to highlight that Liberia, Guinea, and Sierra Leone were the countries most affected by Ebola and provide the context that these countries also needed the most assistance from the rest of the world. Closing airports to those countries and other West African ports of entry would only make the delivery of life-saving aid to the countries more difficult. If the aid and personnel could not reach the people that needed help, this would likely increase the spread of Ebola and consequent risk to the rest of the world. In crisis communication, providing information regarding these broad overlapping issues of national and international context is an essential part of how to communicate.

In the global pandemic of COVID-19, providing the appropriate context during crisis communication directly affects the type of response individuals take to achieve appropriate resolution of the problem. In the COVID-19 pandemic response, how leaders communicate the problem determines how effective their constituents’ response in addressing the problem will be. Characterizing COVID-19 with the appropriate context could limit morbidity and mortality. At this time, there is no known effective cure or vaccine for COVID-19. Additionally, data so far suggest the virus has a basic reproduction number (R0) <2, so for every infected individual, the virus can be spread potentially, on average, to 2 additional people. The COVID-19 virus also has a CFR of ~1%.14 Collectively, these data points, coupled with the number of lives already claimed by COVID-19, require a series of maneuvers, emergency intervention, and rapid response to prevent significant population morbidity and mortality. Context is an integral part of how leaders must communicate during a crisis to ensure that appropriate response and resolution are achieved.

Compassion

Nina Pham held the hand of Mr Duncan when he told her, “He felt very isolated”.15 Days later, Mr Duncan died at the Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital, and Nina Pham was one of the nurses that cared for him. In the wake of the Ebola outbreak, over 800 healthcare workers were affected by the disease, and close to 500 died as a result.16 Ebola significantly affected West African healthcare workers. The dedication of West African healthcare workers and the volunteers from MSF, and others from around the world serve as excellent exemplars of compassion. Their work conclusively demonstrates how compassionate communication during a crisis achieves the desired response of saving lives. Collectively, the providers’ actions showed compassion in advocating and caring for those most in need at a time of their greatest need for human connection. During our work with the West African Disaster Preparedness Initiative, it was clear that many lives were saved because of a genuine concern for the suffering and needs of others. People were anxious, afraid, and concerned about the Ebola outbreak, and there was a need for leaders to respond appropriately with compassion to contain the spread of disease and prevent consequent sequelae.

During the early days of the Ebola crisis, it was how officials and care providers communicated, with compassion and care, that tempered public anxiety, eased the pain of those suffering, and made those last hours of the dying comfortable. As Nina Pham related, “[We] fought in the trenches together, the frontline healthcare workers. That’s what nursing is about: putting the patient first. We did what we had to do.” It was because so many acted with compassion, risked their own safety at times, and did what was needed, that so many lives were ultimately saved during the Ebola outbreak. Based on current experience caring for patients and in practice, the public’s view on COVID-19 is also characterized by anxiety, fear, and uncertainty. Consequently, leaders that employ compassionate communication can help individuals to respond appropriately to COVID-19 and ultimately save lives.

Commitment

The last of the 4C’s principles focuses on commitment. Knowing how to deliver a credible message and provide the appropriate context with care and compassion means little without conveying a commitment to achieving resolution of the problem. During the very first reports of the Ebola outbreak, the WHO expressed a commitment to the local community and the world at large. There was a focused and coordinated coalition being mobilized by the Guinea Minister of Health with the WHO and other agencies to address the Ebola outbreak. This communication provided some assurance to the public that something was being done and helped to minimize the negative impact of fear and concern associated with Ebola. Even for the isolated Ebola patient, it was the commitment of the provider at the bedside willing to hold a hand that delivered the powerful message for the patient, at least temporarily, that someone was there. Similarly, in the COVID-19 pandemic, leaders that convey a commitment to helping people during the crisis is essential to achieve the appropriate response of individuals and engender potential resolution and solutions to the crisis.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSION

The Ebola outbreak exposed the world to a dangerous and deadly virus and provided many lessons and opportunities for improving crisis response. The 2020 COVID-19 pandemic has led to a global crisis. Each leader’s response will test their resolve and their effectiveness. Many situations in healthcare, especially pandemics, require effective crisis communication. President Theodore Roosevelt admonished, “In any moment of [crisis] the best thing you can do is the right thing, the next best thing is the wrong thing, and the worst thing is nothing.”17 This practical guide to crisis communication provides a veritable framework. At the time of crisis recognition, the critical next step of crisis communication is best executed using the 3W’s of what to communicate and the 4C’s of how to communicate to effectively achieve the best response and resolution to keep the public and patients safe and save lives.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author thanks the Defense Institute for Medical Operations (DIMO), U.S. Africa Command (USAFRICOM), Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), Kofi Annan International Peacekeeping Training Centre (KAIPTC), the Republic of Ghana National Disaster Management Organization (NADMO), Operation United Assistance (OUA), and the West Africa Disaster Preparedness Initiative (WADPI) for their support. Special thanks to Dr E. Thomas Moran, Distinguished Service Professor Emeritus, State University of New York (SUNY) Plattsburgh for his support and editorial contributions.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the U.S. Navy, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.

References

- 1. River C. (editor). In: The 1918 Spanish flu pandemic: The history and legacy of the world’s deadliest influenza outbreak. Scotts Valley, California, Create Space Independent Publishing Platform, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sellnow TL, Seeger MW. Theorizing Crisis Communication, Inc. West Sussex UK, John Wiley & Sons, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sellnow TL, Seeger MW. Theorizing Crisis Communication, Inc. West Sussex UK, John Wiley & Sons, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Emily J: Free of Ebola but not fear The Dallas Morning News. 2015. http://res.dallasnews.com/interactives/nina-pham/accessed March 27, 2020.

- 5. Ansari T, et al. : Even hard-hit areas ease limits. Wall Street J 2020. https://www.wsj.com/articles/coronavirus-latest-news-05-03-2020-11588499307accessed May 4, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Morton Hamer MJ, Reed PL, Greulich JD: The West Africa preparedness initiative. Disaster Med Public Health Prep 2017; 11(4): 431–8. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2016.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Andrews TM: Why dangerous conspiracy theories about the virus spread so fast-and how they can be stopped The Washington Post .2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2020/05/01/5g-conspiracy-theory-coronavirus-misinformation/accessed May 4, 2020.

- 8. Turner BA: The organizational and interorganizational development of disasters. Adm Sci Q 1976; 21: 378–97. [Google Scholar]

- 9. World Health Organization Regional Office for Africa. https://www.afro.who.intaccessed March 27, 2020.

- 10. Muller Z: The cost of Ebola. The Lancet 2015; 3(8): 423. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(15)00092-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gielan M. Broadcasting happiness: The science of igniting and sustaining positive change. Dallas, Texas, BenBella Books, Inc, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Price T. Leadership Ethics. Cambridge University Press, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Apuzzo M, Fernandez M: 5 U.S. airports set for travelers from 3 West African nations. New York Times; 2014. http://www.nytimes.com/2014/10/22/us/ebola-west-africa-united-states-flights.html?_r=0accessed March 26, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fauci AS, Lane HC, Redfield RR: Covid-19-navigating the uncharted. N Engl J Med 2020; 382(13): 1268–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe2002387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Emily J: Free of Ebola but not fear. The Dallas Morning News; 2015. http://res.dallasnews.com/interactives/nina-pham/accessed March 27, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fox M: Ebola kills nearly 500 healthcare workers. NBC News.2015. http://www.nbcnews.com/storyline/ebola-virus-outbreak/ebola-kills-nearly-500-health-care-workers-n281801accessed March 26, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Roosevelt T: Brainy Quotes. http://www.brainyquote.com/quotes/quotes/t/theodorero403358.htmlaccessed March 27, 2020.