Abstract

The neurotransmitter gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) is the most abundant inhibitory neurotransmitter in the human brain; however, it is becoming more evident that this non-proteinogenic amino acid plays multiple physiological roles in biology. In the present study, the transport and function of GABA is studied in the highly infectious intracellular bacterium Brucella abortus. The data show that 3H-GABA is imported by B. abortus under nutrient limiting conditions and that the small RNAs AbcR1 and AbcR2 negatively regulate this transport. A specific transport system, gts, is responsible for the transport of GABA as determined by measuring 3H-GABA transport in isogenic deletion strains of known AbcR1/2 regulatory targets; however, this locus is unnecessary for Brucella infection in BALB/c mice. Similar assays revealed that 3H-GABA transport is uninhibited by the 20 standard proteinogenic amino acids, representing preference for the transport of 3H-GABA. Metabolic studies did not show any potential metabolic utilization of GABA by B. abortus as a carbon or nitrogen source, and RNA sequencing analysis revealed limited transcriptional differences between B. abortus 2308 with or without exposure to GABA. While this study provides evidence for GABA transport by B. abortus, questions remain as to why and when this transport is utilized during Brucella pathogenesis.

Introduction

Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) is a non-proteinogenic amino acid that is a common and important inhibitory neurotransmitter in the vertebrate brain [1]. However, our understanding of the biological function of GABA has expanded over the years to include neurobiology, immunology, and bacteriology. With regards to metabolism, the GABA shunt is utilized by both prokaryotes and eukaryotes to metabolize GABA to succinate, which can then be supplied into the TCA cycle [2, 3]. This is achieved by transport of exogenous GABA or conversion of endogenous glutamate to GABA by the enzyme glutamate decarboxylase (GAD). GAD is an important enzyme for both the production of GABA and deacidification of the intracellular environment. If the pH of the cell becomes unfavorably low, GAD can convert glutamate to GABA with the attachment of a proton, then export it out of the cell, which will result in increased intracellular pH [4, 5].

In plants, several studies have revealed the necessity for GABA during metabolism and developmental growth [6–8], but GABA is also an important modulator of immunity against pathogenic organisms, including insects, fungi, and bacteria. Upon plant cell damage, the pH of the plant intracellular environment will decrease, activating the GAD system, producing an excess of secreted GABA surrounding the damaged area of the plant [3]. In insects, increased environmental GABA concentrations have been shown to lead to decreased larvae growth rate, survival, and feeding by pests on tobacco plants [9–11]. Exogenous GABA also has a negative effect on bacterial pathogenesis of plants. A deletion of the GABA transaminase, responsible for the conversion of GABA to succinic semialdehyde in the GABA shunt, in Pseudomonas syringae led to decreased expression of a type III secretion system required for full virulence of the bacterium [12]. This deletion strain displayed significant reductions in virulence in planta when compared to the parental strain, which was attributed to the decreased expression of the type III secretion system [12]. Decreased virulence by exogenous GABA has also been shown in the bacterial plant pathogen Agrobacterium tumefaciens. A. tumefaciens encodes two ABC transport systems, Bra and Gts, that import exogenous GABA [13, 14]. Once GABA is transported into A. tumefaciens, it is catabolized via the GABA shunt and byproducts of the shunt induce the expression of AttM, a lactonase [15]. This lactonase will quench quorum signaling molecules expressed by A. tumefaciens leading to a decrease in the expression of virulence related genes [13, 14]. By increasing the expression of GAD and secretion of GABA by plants, studies have shown that tobacco plant susceptibility to A. tumefaciens can be decreased. Mutating the GAD system in a plant, however, led to increased T-DNA transfer, a major virulence factor, from A. tumefaciens to a tomato plant model [15, 16]. Alternatively, increasing GABA transaminase activity in A. tumefaciens, causing a decrease in intracellular GABA concentrations, led to higher rates of T-DNA transfer and transformation of tomato plants, further emphasizing the inhibitory role of GABA in A. tumefaciens virulence [16].

More recently, GABA has been observed to be an immunomodulator in mammalian systems, and several studies have shown that GABA activates immune cells and plays a role in the antimicrobial activity of macrophages. Bhat et al. demonstrated that immune cells (dendritic cells and macrophages) can synthesize and catabolize GABA, and the presence of GABAergic agents led to a decrease in inflammation [17]. The authors hypothesize that GABA could potentially be utilized as a signaling molecule between immune cells to modulate inflammation. Interestingly, GABAergic signaling has also been shown to enhance phagosomal maturation in macrophages, and inhibition of this signaling led to increased intracellular concentrations of bacteria within a macrophage [18]. These studies reinforce that further understanding of the role GABA plays in eukaryotic immunology is necessary.

Brucella spp. are pathogenic intracellular bacteria within the Order Rhizobiales in the Class Alphaproteobacteria. The brucellae infect a variety of mammalian species, both wild and domesticated, in which brucellosis primarily affects reproductive health in these animals, and chronic infection can lead to multiple organ complications [19, 20]. Several Brucella spp. also have the capacity to cause infection in humans via direct contact with contaminated animal products, and brucellosis is one of the most prevalent zoonoses worldwide [21]. Human brucellosis primarily presents as flu-like symptoms including an undulating fever and chronic infection can also cause damage to multiple organs [22, 23]. Brucella spp. are stealth pathogens that contain few classical virulence factors and primarily evade the host immune system by adaptation to the harsh intracellular environment and formation of a replicative niche within primary immune cells (dendritic cells and macrophages) of the host [24, 25].

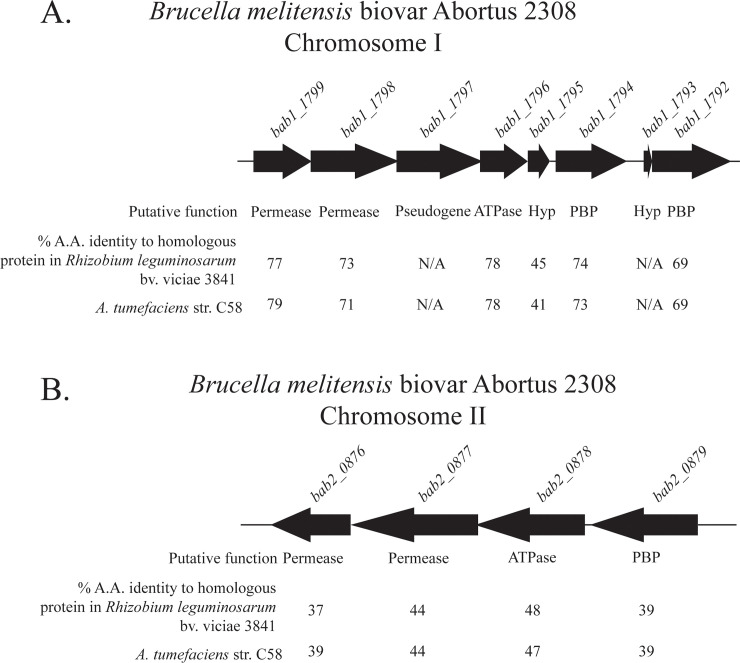

Small regulatory RNAs (sRNAs) are understudied virulence factors of the brucellae, and importantly, sRNAs can swiftly regulate gene function post-transcriptionally to adapt to changing environmental conditions [26]. While characterizing the role of the sRNAs AbcR1 and AbcR2 (AbcR1/2) in B. abortus pathogenesis, it was demonstrated that these small RNAs primarily function as negative regulators of several ABC type transport systems in B. abortus [27]. Two loci regulated by AbcR1/2 have previously been studied with regards to GABA transport in other Alphaproteobacteria [28, 29]. One putative transport system, a locus including bab1_1792-bab1_1799 (bab_rs24455-bab_rs24485), encodes proteins with high amino acid sequence identity to one of the GABA ABC transport systems, Bra, mentioned above in Agrobacterium tumefaciens (Fig 1A). It should be noted that the B. abortus genome has recently been reannotated, and while the old nomenclature will be utilized throughout this manuscript, new gene designations (bab_rs#####) will follow the old designation after the initial mention in the manuscript for reference. Similar to B. abortus, the homologous transport system in A. tumefaciens has also been shown to be negatively regulated by AbcR1 [28]. The second putative transport system, a locus including bab2_0876-bab2_0879 (bab_rs30470-bab_rs30485), encodes proteins with low amino acid sequence identity to the GABA Transport System, Gts, in Rhizobium leguminosarum and A. tumefaciens (Fig 1B) [29].

Fig 1. Organization of putative GABA ABC-type transport systems in B. abortus 2308 and homology to the GABA transport systems in Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. viciae 3841 and Agrobacterium tumefaciens str. C58.

A. Genetic organization of bab1_1972-bab1_1799 located on chromosome I of Brucella melitensis biovar Abortus 2308. Putative functions for each gene and percent amino acid identity to bra genes in related organisms are located below the gene. Proteins encoded from this locus exhibit high amino acid identity to the bra locus in Agrobacterium tumefaciens str. C58. B. Genetic organization of bab2_0876-bab2_0879 located on chromosome II of Brucella melitensis biovar Abortus 2308. Putative functions for each gene and percent amino acid identity to gts genes in related organisms are located below the gene. Proteins encoded from this locus exhibit moderate amino acid identity to the gts locus in R. leguminosarum bv. viciae 3841.

No previous studies have explored the function of GABA within the brucellae, with the exception of the GAD system [30]. Interestingly, the functionality of the GAD system differs between species of Brucella. The “classical” species of Brucella (B. melitensis, B. abortus, B. suis, B. canis, B. neotomae, and B. ovis) do not possess a functional GAD system due to point or frame-shift mutations in gadB and gadC genes [30]. Thus, the potential role for GABA utilization by the “classical” species of Brucella is unknown. The following study will focus on characterizing the potential import of GABA into B. abortus and elucidate the functional role of GABA in Brucella pathogenesis. The results reveal that GABA is transported under nutrient limiting conditions, and GABA transport is regulated by AbcR1 and AbcR2 in B. abortus. The data also showed minimal metabolic or regulatory potential for GABA by B. abortus in vitro under the conditions tested.

Results

B. abortus can import 3H-GABA, and this transport is inhibited by the presence of glutamate

GMM is a commonly used minimal medium in which to grow Brucella to mimic a nutrient-limiting environment [31]. Brucella growth is sustained in this medium but will not reach high concentrations compared to growth in nutrient rich medium, such as brucella broth. GMM specifically contains the amino acid glutamate as a carbon and nitrogen source. We hypothesized that if Brucella could transport GABA, it would most likely occur in growth of limited nutrient concentrations when transport system expression is increased. A GABA transport study was utilized to determine 1) if B. abortus could import 3H-GABA in GMM and 2) if glutamate in the medium would inhibit the uptake of 3H-GABA. The experiment was conducted with GMM containing glutamate (GMM) and GMM without the addition of glutamate (GMM-Glu).

Briefly, B. abortus strains were grown on SBA plates for 48 hours, and then cultures of B. abortus were incubated for 20 minutes in either GMM or GMM-Glu. Subsequently, the cultures were inoculated with 3H-GABA and incubated for an additional 20 minutes. Cultures were then collected via filtration through a syringe filter (see methods). The radioactivity of the filter was measured to quantify the amount of radiation imported by the brucellae collected. If 3H-GABA is imported by B. abortus, then the filter will measure high radioactivity above background; however, if 3H-GABA is not imported by B. abortus, then the 3H-GABA will pass through the filter and the filter will not measure high radioactivity above background. As a control, 1000-fold excess non-radiolabeled GABA was added to the cultures simultaneously to out-compete 3H-GABA import and show specificity for GABA.

The assay revealed that B. abortus 2308 imported 3H-GABA in both GMM and GMM-Glu and this transport was specific for GABA as the addition of excess non-radiolabeled GABA in both culture media significantly decreased 3H-GABA import (Fig 2). However, when glutamate was present in the culture medium, the amount of 3H-GABA imported by B. abortus 2308 decreased by over 95%. These data indicate that transport of 3H-GABA is increased under nutrient limitation.

Fig 2. 3H-GABA import is induced under nutrient limiting conditions.

3H-GABA uptake by B. abortus 2308 was assessed in minimal medium with (GMM) and without (-Glu) the addition of glutamate to the medium. Data is normalized to GMM(-Glu) at 100%. Controls include the addition of excess nonradiolabled GABA to competitively inhibit 3H-GABA uptake. The asterisks denote a statistically significant difference (** P<0.005, *** P<0.0005; Student’s t test) in uptake.

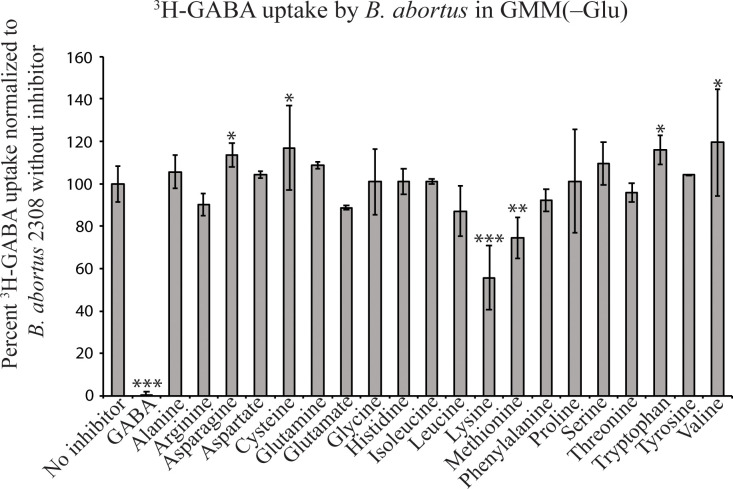

The presence of proteinogenic amino acids does not considerably inhibit the import of 3H-GABA into B. abortus

The above 3H-GABA transport assay was again utilized to assess whether proteinogenic amino acids could competitively inhibit 3H-GABA import in B. abortus. The same assay was utilized, except that B. abortus 2308 was incubated in GMM-Glu (as glutamate inhibited 3H-GABA transport in Fig 2) throughout the experiment. After the initial incubation period, the cultures were inoculated with 3H-GABA and the addition of no inhibitor or 100 μM individual amino acids, resulting in a ratio of 1:1,000 3H-GABA:nonradiolabeled amino acid. The cultures were filtered and measured for radioactivity. The control group showed 3H-GABA uptake was almost completely inhibited by the presence of 1,000-fold excess nonradiolabeled GABA (Fig 3). The import of 3H-GABA was not significantly changed by the presence of most other nonradiolabled amino acids. However, 1,000-fold excess lysine or methionine significantly decreased 3H-GABA import and 1,000-fold excess asparagine, cysteine, tryptophan, or valine significantly increased 3H-GABA import. It should be noted, however, that these difference are small, implying a preference for 3H-GABA import over all proteinogenic amino acids under these conditions.

Fig 3. 3H-GABA import by B. abortus 2308 is not greatly inhibited by the presence of other amino acids in vitro.

3H-GABA uptake by B. abortus 2308 was assessed uninhibited and in the presence of 1,000-fold excess GABA or 20 proteinogenic amino acids. Data is normalized to the absence of inhibitor at 100%. The asterisk denotes a statistically significant difference (* P<0.05, ** P<0.005, *** P<0.0005; Student’s t test) in uptake of 3H-GABA between B. abortus 2308 uninhibited (no inhibitor) and in the presence of excess nonradiolabled GABA, asparagine, cysteine, lysine, methionine, and tryptophan.

Combined with the previous experiment, these results suggest that glutamate does not competitively inhibit the transport of GABA via interactions with the putative transport system, but rather the expression of the GABA transporter may be induced in the absence of glutamate. This experiment also indicates that the mechanism responsible for the transport of GABA would preferentially transport GABA prior to the transport of other amino acids; if this mechanism can transport other amino acids at all.

3H-GABA import is inhibited by the sRNAs AbcR1 and AbcR2

The regulation of GABA transport is mediated by the sRNA AbcR1 in A. tumefaciens, and a deletion of abcR1 results in increased import of radiolabeled GABA in A. tumefaciens [28]. B. abortus 2308 encodes the sRNAs AbcR1 and AbcR2, homologs of AbcR1 in A. tumefaciens, which regulate ABC-type transport systems, including the homologous GABA transport in A. tumefaciens [27]. Therefore, we hypothesized that a deletion of abcR1 and abcR2 in B. abortus would result in increased GABA transport.

To test this hypothesis, the above mentioned 3H-GABA transport assay was utilized to assess the import of 3H-GABA by B. abortus 2308 (2308) or B. abortus 2308::ΔabcR1ΔabcR2 (ΔabcR1/2) (Fig 4). The results indicated that 3H-GABA import was increased by almost 50% in ΔabcR1/2 compared to the parental strain. 1,000-fold excess nonradiolabled GABA was added to cultures as a control, which inhibited 3H-GABA import in both 2308 and ΔabcR1/2. This indicated that GABA transport was negatively regulated by the sRNAs AbcR1 and AbcR2, similarly to what has been observed in A. tumefaciens.

Fig 4. 3H-GABA import is negatively regulated by the sRNAs AbcR1 and AbcR2 in B.

abortus. 3H-GABA uptake by B. abortus 2308 and B. abortus 2308:: ΔabcR1/2 was assessed in minimal medium, GMM(-Glu). Data is normalized to 2308 at 100%. Asterisks denote a statistically significant difference (* P<0.05, ** P<0.005; Student’s t test) in uptake.

bab2_0879 is necessary for the transport of 3H-GABA in B. abortus

Due to the negative regulation of 3H-GABA transport by AbcR1/2 (Fig 4), it was hypothesized that one or more of the transport systems negatively regulated by AbcR1/2 is responsible for the transport of 3H-GABA. To test this hypothesis, the above 3H-GABA transport assay was repeated to measure 3H-GABA uptake in B. abortus 2308, as well as several strains carrying isogenic deletion of genes encoding putative periplasmic binding proteins of transporter systems that are significantly negatively regulated by AbcR1 and AbcR2 [27, 32]. These deletion strains include Δbab2_0612 (bab_rs29240), Δbab2_0879, and Δbab1_1792-bab1_1794 (Fig 5). The isogenic deletion strains of bab2_0612 and bab2_0879 were constructed previously [32], and the combined bab1_1792–1794 deletion strain was generated in the present study. The transport of 3H-GABA only decreased by ~20% in Δbab2_0612 and Δbab1_1792-bab1_1794 when compared to the parental strain, B. abortus 2308, indicating that they may partially be involved in GABA transport. However, the transport of 3H-GABA by Δbab2_0879 decreased by ~97% when compared to B. abortus 2308, implicating bab2_0879 as a component of the main transporter of GABA in B. abortus (Fig 5A). Reconstruction of bab2_0879 on the B. abortus 2308:: Δbab2_0879 genome complemented 3H-GABA import (Fig 5B). These data clearly show that bab2_0879 is involved in GABA transport and should be annotated as gtsA based on homology and function.

Fig 5. Transport of 3H-GABA transport in B. abortus 2308 by AbcR regulated systems.

A. 3H-GABA uptake by B. abortus 2308, Δbab2_0612, Δbab2_0879, Δbab1_1792Δbab1_1794, and Δbab2_0879 in assessed in minimal medium, GMM(-Glu). Data is normalized to 2308 at 100%. Asterisks denote a statistically significant difference (* P<0.05, *** P<0.0005; Student’s t test) in uptake between B. abortus 2308 and deletion strains. B. 3H-GABA uptake by B. abortus 2308, Δbab2_0879, and Δbab2_0879-RCbab2_0879 in minimal medium, GMM(-Glu). Data is normalized to 2308 at 100%. Asterisks denote a statistically significant difference (*** P<0.0005; Student’s t test) in uptake between strains.

bab2_0879 is not necessary for survival and replication in peritoneal derived macrophages nor chronic infection of a mouse model of brucellosis via the oral route of infection

It was reported previously that a deletion of bab2_0879 did not affect the ability of B. abortus to colonize the spleen of a mouse infected intraperitoneally [32]. Therefore, this strain was further tested for its ability to survive and replicate within peritoneally derived macrophages in vitro and to colonize the spleens of mice infected orally in vivo.

A gentamycin protection assay was utilized to assess the survival and replication of B. abortus strains within macrophages. Naïve macrophages were isolated from the peritoneal cavity and infected with either B. abortus 2308 or B. abortus 2308:: Δbab2_0879 (Δbab2_0879) at an MOI of 100. Infected macrophages were lysed 2, 24, and 48 hours post-infection and serial diluted to calculate CFU brucellae/well. A deletion of bab2_0879 did not affect the ability of B. abortus to survive and replicate within macrophages when compared to the parental strain B. abortus 2308 (Fig 6A).

Fig 6. Virulence of B. abortus 2308 and Δbab2_0879 in peritoneally derived macrophages and BALB/c mice.

A. Macrophage survival and replication experiments. Cultured peritoneal macrophages from BALB/c mice were infected with B. abortus 2308 and the isogenic bab2_0879 deletion strain (Δbab2_0879). At the indicated times post-infection, macrophages were lysed, and the number of intracellular brucellae present in these phagocytes was determined by serial dilution and plating on agar medium. B. Oral mouse infection experiments. BALB/c mice (6 per strain) were infected intraperitoneally with B. abortus 2308 and Δbab2_0879. Mice were sacrificed 1, 2, and 4 weeks post-infection, and Log10 brucellae/spleen were calculated. The data are presented as average numbers of brucellae ± standard deviations of results from the 6 mice (3 male and 3 female mice) colonized with a specific Brucella strain at each time point.

BALB/c mice were infected orally with 109 CFU of B. abortus 2308 or Δbab2_0879 and infection was monitored 1, 2, and 4 weeks post-infection. After 1, 2, or 4 weeks, the mice were sacrificed, spleens removed and homogenized, and homogenates were serial diluted to determine CFU brucellae/spleen (Fig 6B). Under the conditions tested, the ability of the B. abortus Δbab2_0879 strain to colonize the spleen was not significantly changed when compared to the parental strain.

GABA is not utilized as a nitrogen or carbon source by Brucella

To elucidate the biological role of GABA in the brucellae, two situations were considered: GABA is either acting as a source of carbon and/or nitrogen, or GABA functions as a signaling molecule to induce changes in gene expression. The hypothesis that GABA is a metabolite was first examined. As mentioned before, GMM is often utilized as a defined medium to mimic a nutrient-limiting environment. This medium was developed in 1958 by Philipp Gerhardt and contains several sources of carbon; including lactic acid, glycerol, and glutamate; and glutamate as the sole nitrogen source [31]. Growth curves were utilized to test the ability for GABA to be utilized as a nitrogen source for the brucellae via replacement of glutamate. B. abortus 2308 was grown overnight in brucella broth to late exponential phase, pelleted and washed, and then used to inoculate GMM with glutamate (GMM), GMM without glutamate (GMM-Glu), or GMM without glutamate but supplemented with GABA (0.15%) (GMM-Glu+GABA). Growth of the bacterium was measured in each culture for 175 hours (Fig 7A). Initially, all cultures showed growth, most likely due to residual nutrients from the nutrient rich brucella broth. However, B. abortus 2308 grown in GMM-Glu and GMM-Glu+GABA revealed a decrease in bacterial concentration in comparison to B. abortus 2308 in GMM over time. This indicated that GABA is likely not utilized as a nitrogen source in place of glutamate for sustained B. abortus growth.

Fig 7. GABA is not utilized as a metabolite by B. abortus 2308 in vitro.

A. Growth of B. abortus 2308 in minimal medium (GMM), minimal medium lacking glutamate (GMM-Glu), and minimal medium lacking glutamate with the addition of GABA (0.15%) (GMM-Glu+GABA). The asterisk denotes a statistically significant difference (* P<0.05; Student’s t test) in uptake between B. abortus 2308 grown in GMM compared to B. abortus 2308 grown in either GMM-Glu or GMM-Glu+GABA. B. Oxygen consumption by B. abortus 2308 grown in TSB with the addition of either GABA, glutamate, or erythritol 300 seconds after inoculation measured via oxygraph machine.

A respirometry assay was utilized to assess GABA as a potential carbon source utilized by B. abortus. Oxygen concentrations of B. abortus cultures were measured via oxygraph machine to calculate respiration in response to different carbon sources. The carbon sources tested included GABA, glutamate, or erythritol. The metabolic role of glutamate is discussed above. Erythritol is a sugar alcohol found in the reproductive tracts of animals susceptible to brucellosis and has been shown to be a preferred carbon source for brucellae growth as well as an inducer of virulence related genes [33, 34]. Oxygen is consumed during aerobic respiration, thus if the bacterium is actively utilizing the supplied carbon source, then respiration will increase and oxygen concentrations of the culture medium will decrease. In the presence of erythritol, a preferred carbon source of B. abortus, respiration occurred at a high rate and oxygen levels decreased rapidly (Fig 7B). In the presence of glutamate, a suitable carbon and nitrogen source for B. abortus, but not preferred over erythritol, respiration occurred at a slower rate compared to erythritol, but oxygen consumption still occurred. In the presence of GABA, however, the change in oxygen concentration over time was negligible, indicating that GABA was not utilized as a carbon source by B. abortus (Fig 7B).

Minimal transcriptional changes were observed in B. abortus 2308 exposed to exogenous GABA

RNAseq analysis was performed to assess the potential role of GABA as a signaling molecule. RNA was isolated from cultures of B. abortus 2308 grown aerobically in GMM in the presence or absence of 1 mM GABA and analyzed via RNA-seq analysis. Only one gene, the putative transposase BAB_RS29595, was downregulated 2.26 fold in the culture treated with 1 mM GABA.

Discussion

In this study, the transport and biological function of GABA was analyzed in the intracellular pathogen B. abortus. The data presented revealed that 3H-GABA is transported under nutrient limiting conditions, transport was regulated by the sRNAs AbcR1 and AbcR2, and transport occurred via an ABC-transport system homologous to the gts system in Rhizobium leguminosarum and A. tumefaciens. Because of these results, we have annotated bab2_0876-bab2_0879 as gtsC, gtsB, gtsD, gtsA for GABA transport system, respectively (Fig 1B).

The observation that the Gts system transports GABA preferentially over proteinogenic amino acids is intriguing, because this is not what is observed in A. tumefaciens. In A. tumefaciens, 3H-GABA uptake was competitively inhibited by short lateral chain amino acids, as well as proline [13]. Dissimilar from A. tumefaciens, 3H-GABA transport in B. abortus was uninhibited by the presence of other amino acids (Fig 3). This is a significant divergence between the two related organisms with regards to GABA transport and can be explained by a difference in the number of transporters between the two organisms. A. tumefaciens contains two GABA transport systems, Bra which is responsible for the transport of several amino acids and Gts which solely transports GABA [35]. As stated previously, B. abortus encodes two putative GABA transporters, bab1_1794 which is homologous to the periplasmic binding protein of Bra and bab2_0879 which is homologous to the periplasmic binding protein of Gts. Our results clearly show GABA transport in B. abortus is primarily mediated by gts (Fig 5). This result was surprising due to the low amino acid sequence identity of BAB2_0876-BAB2_0879 to the Gts GABA transporter in R. leguminosarum and A. tumefaciens (<40%) compared to the high amino acid sequence identity of BAB1_1794-BAB1_1799 compared to the Bra GABA transport system in A. tumefaciens (>70%) (Fig 1). In B. abortus, the Bra system (i.e., BAB1_1792–1799) does not appear to be a specific GABA transporter, and this reveals a deviation within the Rhizobiales with regards to amino acid transport, which may explain why GABA transport was unaffected by the presence of other amino acids. Nonetheless, it is important to note that deletion of bab2_0612 and bab1_1792–1794 also lead to significant decreases in GABA transport (Fig 5), and therefore, while these systems may not be primary GABA transporters, it is clear that BAB2_0612 and BAB1_1792–1794 have the ability to support moderate GABA import by B. abortus.

We were unable to clearly define the biological role of GABA transport in B. abortus, despite metabolic and transcriptomic analyses. There are several potential reasons for this, including the potential for the identified transporter to also be able to transport other molecules. While the amino acid competition assay showed preference for GABA transport over proteinogenic amino acids, this does not discount the possibility that the Gts system is also able to transport other non-proteinogenic amino acids. The National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) has gtsA annotated as a “spermidine/putrescine ABC transporter substrate-binding protein” in B. abortus. It has recently come to light that polyamines, such as spermidine and putrescine, are important for the persistence of B. abortus during chronic infection [36]. Therefore, further analyses of Gts in B. abortus may be necessary to characterize the potential for transport of both proteinogenic amino acids and polyamines.

Understanding the processing of imported GABA in other organisms can lead to important insights into the biological role of GABA; the Brucella genome may provide clues to this processing. The GABA shunt can be utilized to form succinate, a substrate utilized during the TCA cycle [2, 3]. This process occurs by converting GABA to succinic semialdehyde by the enzyme GABA-transaminase (GabT), followed by the conversion from succinic semialdehyde to succinate by succinic semialdehyde dehydrogenase (SSDH) [2]. Although the metabolic studies presented here do not reveal any metabolic utilization of GABA by B. abortus, the Brucella genome does contain genes encoding putative GabT (BAB2_0285) and SSDH (GabD, BAB1_1655). The function of these genes has not been characterized, but if functional, one or both could be important in the conversion of GABA to a utilizable carbon substrate. It is possible that mass spectrometry analyses of imported radiolabeled GABA could identify if and how GABA is processed by B. abortus and could lead to the formation of new hypotheses regarding the processing of this molecule by the brucellae. In the end, while we did not observe GABA utilization under the specific experimental conditions shown here, it is possible that Brucella catabolizes GABA under another condition or set of conditions that are encountered by the bacteria during infection.

This study and previous work from our lab has shown that deletion of gtsA (bab2_0879) did not change the ability of B. abortus to survival and replicate in peritoneally derived macrophage nor in a mouse model of infection via IP injection or oral route in BALB/c mice [32]. Interestingly, several studies identified gtsA as a potential virulence factor via different in vitro and in vivo screens. Firstly, the expression of gtsA has been shown to be increased in a quorum sensing mutant (ΔbabR) and in the B. melitensis Rev. 1 vaccine strain when compared to the parental strain B. melitensis 16M [37, 38]. Genomic analysis revealed a nonsynonymous mutation in gtsA in the B. melitensis vaccine strain M5 when compared to B. melitensis 16M [39]. Delrue et al. published a list of attenuated Brucella mutants in large-scale in vitro and in vivo screens [40]. They reported that a mutation in BMEII0923 (a homolog of gtsA in B. melitensis) and BRA0326 (a homolog of gtsA in B. suis) was attenuated in a mouse model. Importantly, BAB2_0879, BMEII0923, and BRA0326 are 100% identical at the amino acid level. The type of mutation and mouse model utilized in this screen was not described, but this finding is intriguing and leads to further questions about whether gtsA has homologous functions in different Brucella species and whether the mouse model utilized in our study versus the Delrue study could lead to different observations in virulence [41]. Despite our results showing no difference in infection between ΔgtsA compared to B. abortus 2308, these studies highlight the potential role for gtsA in B. abortus virulence and further analysis may be warranted. There are several possibilities for these differences, including differences in mouse strains (e.g., BALB/c vs. C57BL/6) and routes of infection (e.g., oral vs. intraperitoneal vs. aerosol) employed and moreover, while the gts system is dispensable for the infection of mice, it is possible that the Gts system is important for infection in natural host animals. Brucellosis also presents as a neurological disease in humans and marine mammals and recent evidence has shown that B. abortus can traverse the blood brain barrier [41–43]. Since GABA is an important and abundant neurotransmitter in the brain, it is possible that gts plays a significant and specific role in neurobrucellosis pathology.

Overall, this study characterizes the transport of the ubiquitous non-proteinogenic amino acid GABA by the intracellular bacterial pathogen B. abortus. While transport assays provided novel insights into the transport of this molecule by B. abortus, the data revealed limited metabolic, transcriptional, or virulence phenotypes in a deletion strain of this transporter. However, evidence found throughout scientific literature continues to add to the hypothesis that GABA and the Gts system are important for the pathogenesis of Brucella, warranting further studies to understand the biological role of GABA.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strains and growth conditions

B. abortus 2308 and derivative strains were routinely grown on Schaedler blood agar (SBA), which is composed of Schaedler agar (BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ) containing 5% defibrinated bovine blood (Quad Five, Ryegate, MT). Cultures were routinely grown in brucella broth (BD), tryptic soy broth (TSB), or in Gerhardt’s Minimal Medium (GMM) [31]. For cloning, Escherichia coli strain DH5α was grown on tryptic soy agar (BD) or in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth. When appropriate, growth media were supplemented with kanamycin (45 μg/ml).

Ethics statement

The experiments involving animals were carried out in strict accordance to the regulations set forth by Virginia Tech, as well as in accordance with all federal regulations. These experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) under Virginia Tech IACUC protocol 19–052. Additionally, these experiments were performed at Virginia Tech’s VA-MD College of Veterinary Medicine, which is accredited by the Association for the Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC).

Construction of B. abortus deletion strains

B. abortus strains containing isogenic, unmarked, nonpolar deletions of bab2_0879 and bab2_0612 were constructed for a previous study [32]. A single strain containing a deletion of the bab1_1794 and bab1_1792 locus in B. abortus 2308 was constructed using a nonpolar, unmarked gene excision strategy as described previously [44]. Briefly, an approximately 1-kb fragment of the upstream region of bab1_1794 extending to the second codon of the coding region was amplified by PCR using primers bab1_1794-Up-For and bab1_1794-Up-Rev and genomic DNA from B. abortus 2308 as a template. Similarly, a fragment containing the last two codons of the coding region and extending to approximately 1 kb downstream of the bab1_1792 open reading frame (ORF) was amplified with primers bab1_1792-Down-For and bab1_1792-Down-Rev. The sequences of all oligonucleotide primers used in this study can be found in Table 1, and the plasmids used in the study are listed in Table 2. The upstream fragment was digested with BamHI, the downstream fragment was digested with PstI, and both fragments were treated with polynucleotide kinase in the presence of ATP. Both of the DNA fragments were included in a single ligation mix with BamHI/PstI-digested pNTPS138 (M.R.K. Alley, unpublished data) and T4 DNA ligase (Monserate Biotechnology Group, San Diego, CA). The resulting plasmid (pΔbab1_1794Δbab1_1792) was introduced into B. abortus 2308, and merodiploid transformants were obtained by selection on SBA plus kanamycin. A single kanamycin-resistant clone was grown for >6 h in brucella broth and then plated onto SBA containing 10% sucrose. Genomic DNA was isolated from sucrose resistant, kanamycin-sensitive colonies and screened by PCR for loss of the bab1_1794-bab1_1792 locus.

Table 1. Oligonucleotide primers used in this study.

| Primer name | Sequence (5'->3’) |

|---|---|

| bab1_1794-Up-For | TAGGATCCTGTTCCCGCGTCTGAAGGAGC |

| bab1_1794-Up-Rev | GAAGGCGATGACTGCAGCAAGAG |

| bab1_1792-Down-For | TACTTCCAGAAGTAAATTGCC |

| bab1_1792-Down-Rev | GACTGCAGACGCTCAAAAAGATGGACCG |

*Underlined sequences depict a restriction endonuclease recognition site.

Table 2. Plasmids used in this study.

| Plasmid name | Description | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| pNPTS138 | Cloning vector; contains sacB; KanR | (M.R.K. Alley, unpublished) |

| pΔbab1_1794Δbab1_1792 | In-frame deletion of bab1_1794 and bab1_1792 locus plus 1 kb of each flanking region in pNPTS138 | This study |

3H-GABA uptake assays

A radiolabeled transport assay was utilized to assess the ability of B. abortus strains to import tritium labelled GABA (3H-GABA) grown under several growth conditions. Gerhardt’s Minimal Media (GMM) was inoculated with Brucella strains at a concentration of 109 CFU brucellae/ml and incubated for 20 minutes at 37°C with shaking. The cultures were then inoculated with 3H-GABA at a final concentration of 100 nM and incubated for another 20 minutes at 37°C with shaking. The bacteria were collected via filtration through a filter (0.45 μm), washed three times with GMM, and the radioactivity of the filter was measured to quantify the amount of radiation imported by the brucellae collected on the filter by scintillation counter. If 3H-GABA is imported by B. abortus, then the filter will measure high radioactivity above background; however, if 3H-GABA is not imported by B. abortus, then the 3H-GABA will pass through the filter and the filter will not measure high radioactivity above background.

Respirometry assay

Culture tubes of 5 mL of TSB were inoculated with B. abortus 2308 at a final concentration of 107 CFU/mL and either 10 mM erythritol, glutamic acid, or GABA. The cultures were grown overnight at 37°C with shaking. The following day, the brucellae were pelleted, supernatant removed, and pellet resuspended in PBS at a final concentration of 102 CFU/mL. Samples were then loaded into an oxygraph and oxygen concentrations were subsequently measured. After 300 seconds, erythritol, glutamic acid, or GABA were added to the corresponding culture tube at a final concentration of 100 mM and culture oxygen concentrations were measured for 2000 seconds.

RNA sampling of GABA treated cultures

Brucella broth was inoculated with B. abortus 2308 and incubated at 37°C with shaking for ~24 hours until the cultured obtained an O.D. 600 nm of 0.15. Cells were then washed with PBS and cells were used to inoculate either GMM or GMM with the addition of 1 mM L-GABA at a concentration of 109 CFU/mL. Cultures were incubated for 20 minutes at 37°C with shaking. Following incubation, an equal volume of 1:1 ethanol:acetone was added to each culture and cultures were frozen at -80°C until RNA isolation. This was performed in triplicate for each condition. RNA was isolated from each culture and DNase treated prior to submission for RNAseq analysis.

Stranded RNA library construction for prokaryotic RNA-seq

1 μg of total RNA with RIN ≥ 8.0 was depleted of rRNA using Illumina's Ribo-Zero rRNA Removal Kit (Gram-Positive and Gram-Negative Bacteria) (P/N MRZB12424, Illumina, CA). The depleted RNA is fragmented and converted to first strand cDNA using reverse transcriptase and random primers using Illumina’s TruSeq Stranded mRNA HT Sample Prep Kit (Illumina, RS-122-2103). This is followed by second strand synthesis using polymerase I and RNAse H, and dNTPs that contain dUTP instead of dTTP. The cDNA fragments then go through end repair, addition of a single ‘A’ base, and then ligation of adapters and indexed individually. The products are then purified and the second strand digested with N-Glycosylase, thus resulting in stranded template. The template molecules with the adapters are enriched by 10 cycles of PCR to create the final cDNA library. The library generated is validated using Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer and quantitated using Quant-iT dsDNA HS Kit (Invitrogen) and qPCR. A total of 12 individually indexed cDNA libraries were pooled and sequenced on Illumina NextSeq.

Illumina NextSeq sequencing

The libraries are clustered and sequenced using, NextSeq 500/550 High Output kit V2 (150 cycles) (P/N FC-404-2002) to 2 x 75 cycles to generate paired end reads. The Illumina NextSeq Control Software v2.1.0.32 with Real Time Analysis RTA v2.4.11.0 was used to provide the management and execution of the NextSeq 500 and to generate BCL files. The BCL files were converted to FASTQ files and demultiplexed using bcl2fastq Conversion Software v2.20.

RNA-Seq data processing and analysis

The B. abortus 2308 gene and genome sequences, as well as corresponding annotations from NCBI (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) were used as the reference. Raw reads were quality-controlled and filtered with FastqMcf [45], resulting in an average of 1,821 Mbp (1,672 to 2,061 Mbp) nucleotides. The remaining reads were mapped to the gene reference using BWA (Li & Durbin, 2009) with default parameters. Differential expression of genes was calculated using the edgeR [46] package in R software (http://www.r-project.org/), with Benjamini–Hochberg adjusted P-values of 0.05 considered to be significant. The NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) accession number for the RNA-seq data is PRJNA629010.

Virulence of Brucella strains in cultured murine macrophages and experimentally infected mice

Experiments to test the virulence of Brucella strains in primary murine peritoneal macrophages were carried out as described previously [47]. Briefly, resident peritoneal macrophages were isolated from BALB/c mice and seeded in 96-well plates in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium with 5% fetal bovine serum. The following day, Brucella strains were opsonized by incubating the strains with serum (1:1000 dilution) from previously infected mice (8 weeks post-infection) and the seeded macrophages were infected with brucellae at an MOI of 100:1. After 2 h of infection, extracellular bacteria were killed by treatment with gentamicin (50 μg/ml). For the 2-h time point, the macrophages were then lysed with 0.1% deoxycholate–PBS, and serial dilutions were plated on Schaedler blood agar (SBA). For the 24- and 48-h time points, the cells were washed with PBS following gentamicin treatment, and fresh cell culture medium containing gentamicin (20 μg/ml) was added to the monolayer. At the indicated time point, the macrophages were lysed, and serial dilutions were plated on SBA. Triplicate wells were used for each Brucella strain tested. Infection and colonization of mice by Brucella strains were measured by oral route of infection. BALB/c mice (6 mice per Brucella strain, 3 male and 3 female) were infected orally with 109 CFU of each Brucella strain in sterile PBS. The animals were housed in microisolator cages in the ABSL3 laboratory, and the mice were subjected to 12-hour light– 12-hour dark cycles. Additionally, the mice were given access to pellet-style food and water ad libitum. The animals were monitored daily for signs of distress and pain in accordance with the guidelines of NIH’s Animal Research Advisory Committee (https://oacu.oir.nih.gov/animal-research-advisory-committee-guidelines). The mice were sacrificed at 1, 2, and 4 weeks post-infection, and serial dilutions of spleen homogenates were plated on SBA to determine CFU counts of brucellae/spleen.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Teaching & Research Animal Care Support Service (TRACSS) at the VA-MD College of Veterinary Medicine for their rigorous and meticulous care of the animals used in this work.

Data Availability

All RNA-seq files are available from the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) database (accession number PRJNA629010)

Funding Statement

C.C.C. AI125958 National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) https://www.niaid.nih.gov/ The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Mittal R, Debs LH, Patel AP, Nguyen D, Patel K, O'Connor G, et al. Neurotransmitters: The Critical Modulators Regulating Gut-Brain Axis. J Cell Physiol. 2017;232(9):2359–72. 10.1002/jcp.25518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feehily C, Karatzas KA. Role of glutamate metabolism in bacterial responses towards acid and other stresses. J Appl Microbiol. 2013;114(1):11–24. 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2012.05434.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shelp BJ, Bown AW, McLean MD. Metabolism and functions of gamma-aminobutyric acid. Trends Plant Sci. 1999;4(11):446–52. 10.1016/s1360-1385(99)01486-7 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pennacchietti E, D'Alonzo C, Freddi L, Occhialini A, De Biase D. The Glutaminase-Dependent Acid Resistance System: Qualitative and Quantitative Assays and Analysis of Its Distribution in Enteric Bacteria. Frontiers in microbiology. 2018;9:2869 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Biase D, Pennacchietti E. Glutamate decarboxylase-dependent acid resistance in orally acquired bacteria: function, distribution and biomedical implications of the gadBC operon. Mol Microbiol. 2012;86(4):770–86. 10.1111/mmi.12020 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Palanivelu R, Brass L, Edlund AF, Preuss D. Pollen tube growth and guidance is regulated by POP2, an Arabidopsis gene that controls GABA levels. Cell. 2003;114(1):47–59. 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00479-3 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bown AW, Shelp BJ. Plant GABA: Not Just a Metabolite. Trends Plant Sci. 2016;21(10):811–3. 10.1016/j.tplants.2016.08.001 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Michaeli S, Fromm H. Closing the loop on the GABA shunt in plants: are GABA metabolism and signaling entwined? Front Plant Sci. 2015;6:419 10.3389/fpls.2015.00419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ramputh AI, Bown AW. Rapid [gamma]-Aminobutyric Acid Synthesis and the Inhibition of the Growth and Development of Oblique-Banded Leaf-Roller Larvae. Plant Physiol. 1996;111(4):1349–52. 10.1104/pp.111.4.1349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shelp BJ, Bown AW, Faure D. Extracellular gamma-aminobutyrate mediates communication between plants and other organisms. Plant Physiol. 2006;142(4):1350–2. 10.1104/pp.106.088955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.MacGregor KB, Shelp BJ, Peiris S, Bown AW. Overexpression of glutamate decarboxylase in transgenic tobacco plants deters feeding by phytophagous insect larvae. J Chem Ecol. 2003;29(9):2177–82. 10.1023/a:1025650914947 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park DH, Mirabella R, Bronstein PA, Preston GM, Haring MA, Lim CK, et al. Mutations in gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) transaminase genes in plants or Pseudomonas syringae reduce bacterial virulence. Plant J. 2010;64(2):318–30. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04327.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Planamente S, Vigouroux A, Mondy S, Nicaise M, Faure D, Morera S. A conserved mechanism of GABA binding and antagonism is revealed by structure-function analysis of the periplasmic binding protein Atu2422 in Agrobacterium tumefaciens. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(39):30294–303. 10.1074/jbc.M110.140715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Planamente S, Morera S, Faure D. In planta fitness-cost of the Atu4232-regulon encoding for a selective GABA-binding sensor in Agrobacterium. Commun Integr Biol. 2013;6(3):e23692 10.4161/cib.23692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chevrot R, Rosen R, Haudecoeur E, Cirou A, Shelp BJ, Ron E, et al. GABA controls the level of quorum-sensing signal in Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(19):7460–4. 10.1073/pnas.0600313103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nonaka S, Someya T, Zhou S, Takayama M, Nakamura K, Ezura H. An Agrobacterium tumefaciens Strain with Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid Transaminase Activity Shows an Enhanced Genetic Transformation Ability in Plants. Sci Rep. 2017;7:42649 10.1038/srep42649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bhat R, Axtell R, Mitra A, Miranda M, Lock C, Tsien RW, et al. Inhibitory role for GABA in autoimmune inflammation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(6):2580–5. 10.1073/pnas.0915139107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim JK, Kim YS, Lee HM, Jin HS, Neupane C, Kim S, et al. GABAergic signaling linked to autophagy enhances host protection against intracellular bacterial infections. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):4184 10.1038/s41467-018-06487-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hull NC, Schumaker BA. Comparisons of brucellosis between human and veterinary medicine. Infect Ecol Epidemiol. 2018;8(1):1500846 10.1080/20008686.2018.1500846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.von Bargen K, Gorvel JP, Salcedo SP. Internal affairs: investigating the Brucella intracellular lifestyle. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2012;36(3):533–62. 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2012.00334.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pappas G, Papadimitriou P, Akritidis N, Christou L, Tsianos EV. The new global map of human brucellosis. The Lancet Infectious diseases. 2006;6(2):91–9. Epub 2006/01/28. 10.1016/S1473-3099(06)70382-6 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Figueiredo P, Ficht TA, Rice-Ficht A, Rossetti CA, Adams LG. Pathogenesis and immunobiology of brucellosis: review of Brucella-host interactions. Am J Pathol. 2015;185(6):1505–17. 10.1016/j.ajpath.2015.03.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dean AS, Crump L, Greter H, Hattendorf J, Schelling E, Zinsstag J. Clinical manifestations of human brucellosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2012;6(12):e1929 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roop RM 2nd, Gaines JM, Anderson ES, Caswell CC, Martin DW. Survival of the fittest: how Brucella strains adapt to their intracellular niche in the host. Med Microbiol Immunol. 2009;198(4):221–38. 10.1007/s00430-009-0123-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.He Y. Analyses of Brucella pathogenesis, host immunity, and vaccine targets using systems biology and bioinformatics. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2012;2:2 10.3389/fcimb.2012.00002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Waters LS, Storz G. Regulatory RNAs in bacteria. Cell. 2009;136(4):615–28. 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Caswell CC, Gaines JM, Ciborowski P, Smith D, Borchers CH, Roux CM, et al. Identification of two small regulatory RNAs linked to virulence in Brucella abortus 2308. Mol Microbiol. 2012;85(2):345–60. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2012.08117.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wilms I, Voss B, Hess WR, Leichert LI, Narberhaus F. Small RNA-mediated control of the Agrobacterium tumefaciens GABA binding protein. Mol Microbiol. 2011;80(2):492–506. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07589.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.White JP, Prell J, Ramachandran VK, Poole PS. Characterization of a {gamma}-aminobutyric acid transport system of Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. viciae 3841. J Bacteriol. 2009;191(5):1547–55. 10.1128/JB.00926-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Damiano MA, Bastianelli D, Al Dahouk S, Kohler S, Cloeckaert A, De Biase D, et al. Glutamate decarboxylase-dependent acid resistance in Brucella spp.: distribution and contribution to fitness under extremely acidic conditions. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2015;81(2):578–86. 10.1128/AEM.02928-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gerhardt P. The nutrition of brucellae. Bacteriol Rev. 1958;22(2):81–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sheehan LM, Caswell CC. A 6-Nucleotide Regulatory Motif within the AbcR Small RNAs of Brucella abortus Mediates Host-Pathogen Interactions. mBio. 2017;8(3). 10.1128/mBio.00473-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Keppie J, Williams AE, Witt K, Smith H. The Role of Erythritol in the Tissue Localization of the Brucellae. Br J Exp Pathol. 1965;46:104–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Petersen E, Rajashekara G, Sanakkayala N, Eskra L, Harms J, Splitter G. Erythritol triggers expression of virulence traits in Brucella melitensis. Microbes Infect. 2013;15(6–7):440–9. 10.1016/j.micinf.2013.02.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lang J, Gonzalez-Mula A, Taconnat L, Clement G, Faure D. The plant GABA signaling downregulates horizontal transfer of the Agrobacterium tumefaciens virulence plasmid. New Phytol. 2016;210(3):974–83. 10.1111/nph.13813 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kerrinnes T, Winter MG, Young BM, Diaz-Ochoa VE, Winter SE, Tsolis RM. Utilization of Host Polyamines in Alternatively Activated Macrophages Promotes Chronic Infection by Brucella abortus. Infect Immun. 2018;86(3). 10.1128/IAI.00458-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Uzureau S, Lemaire J, Delaive E, Dieu M, Gaigneaux A, Raes M, et al. Global analysis of quorum sensing targets in the intracellular pathogen Brucella melitensis 16 M. J Proteome Res. 2010;9(6):3200–17. 10.1021/pr100068p [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Salmon-Divon M, Zahavi T, Kornspan D. Transcriptomic Analysis of the Brucella melitensis Rev.1 Vaccine Strain in an Acidic Environment: Insights Into Virulence Attenuation. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:250 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jiang H, Du P, Zhang W, Wang H, Zhao H, Piao D, et al. Comparative genomic analysis of Brucella melitensis vaccine strain M5 provides insights into virulence attenuation. PLoS One. 2013;8(8):e70852 10.1371/journal.pone.0070852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Delrue RM, Lestrate P, Tibor A, Letesson JJ, De Bolle X. Brucella pathogenesis, genes identified from random large-scale screens. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2004;231(1):1–12. 10.1016/S0378-1097(03)00963-7 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miraglia MC, Rodriguez AM, Barrionuevo P, Rodriguez J, Kim KS, Dennis VA, et al. Brucella abortus Traverses Brain Microvascular Endothelial Cells Using Infected Monocytes as a Trojan Horse. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2018;8:200 10.3389/fcimb.2018.00200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rodriguez AM, Delpino MV, Miraglia MC, Giambartolomei GH. Immune Mediators of Pathology in Neurobrucellosis: From Blood to Central Nervous System. Neuroscience. 2019;410:264–73. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2019.05.018 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bahemuka M, Shemena AR, Panayiotopoulos CP, al-Aska AK, Obeid T, Daif AK. Neurological syndromes of brucellosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1988;51(8):1017–21. 10.1136/jnnp.51.8.1017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Budnick JA, Sheehan LM, Colquhoun JM, Dunman PM, Walker GC, Roop RM 2nd, et al. Endoribonuclease YbeY Is Linked to Proper Cellular Morphology and Virulence in Brucella abortus. J Bacteriol. 2018;200(12). 10.1128/JB.00105-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Aronesty E. Comparison of Sequencing Utility Programs. The Open Bioinformatics Journal. 2013;7:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, Smyth GK. edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(1):139–40. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gee JM, Valderas MW, Kovach ME, Grippe VK, Robertson GT, Ng WL, et al. The Brucella abortus Cu,Zn superoxide dismutase is required for optimal resistance to oxidative killing by murine macrophages and wild-type virulence in experimentally infected mice. Infect Immun. 2005;73(5):2873–80. 10.1128/IAI.73.5.2873-2880.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]