Abstract

The current COVID-19 crisis has significantly impacted healthcare systems worldwide. There has been a palpable increase in public avoidance of hospitals, which has interfered in timely care of critical cardiovascular conditions. Complications from late presentation of myocardial infarction, which had become a rarity, resurfaced during the pandemic. We present two such encounters that occurred due to delay in seeking medical care following myocardial infarction due to the fear of contracting COVID-19 in the hospital. Moreover, a comprehensive review of literature is performed to illustrate the potential factors delaying and decreasing timely presentations and interventions for time-dependent medical emergencies like ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). We emphasise that clinicians should remain vigilant of encountering rare and catastrophic complications of STEMI during this current era of COVID-19 pandemic.

Keywords: cardiovascular medicine, interventional cardiology, global health, healthcare improvement and patient safety

Background

A dramatic and perplexing drop in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) admissions has been observed during the current COVID-19 crisis. Anecdotal evidence suggests that the principal reason behind this is patient’s anxiety to avoid seeking medical care at hospitals and overwhelmed healthcare systems due to the pandemic.1 Patients are less inclined to visit hospitals with fear of acquiring COVID-19. Many patients with risk factors of STEMI may dismiss their angina symptoms as benign relative to this fear. This attitude of medical care avoidance has led to delay in hospital presentations, with dire consequences.2 Furthermore, the COVID-19 pandemic has impacted the healthcare system’s maintenance of operational integrity of high-acuity patients.3 Herein, we chronicle two cases of delayed presentations of STEMI with rare complications that we encountered at our centre in the month of April 2020. Both patients belonged to the Cuyahoga county of the state of Ohio, USA. They avoided medical care for a time-dependent medical emergency, despite having good social and financial support and easy access to tertiary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) capable healthcare facilities.4 Their dramatic presentation of STEMI with a complicated clinical course and outcomes could have been prevented by an early referral to emergency medical services. This was the time period when the Cuyahoga county was one of the most severely affected regions of Ohio with the most COVID-19 fatalities reported across the state.5

Case presentation

Case presentation 1

Patient 1 is a 62-year-old Caucasian woman who presented to the emergency department (ED) with shortness of breath and dizziness for 1 day. She stated having nausea and diarrhoea for 2 weeks, associated with intermittent chest pain. She was hesitant getting medical attention and her symptoms got complicated with shortness of breath and dizziness. Her medical history is significant for lifelong cigarette smoking, obesity (BMI of 38 kg/m2) and untreated hyperlipidaemia. On presentation, she had a blood pressure of 96/69 mm Hg, heart rate of 89 beats per minute (bpm), temperature of 98.7°F and respiratory rate of 14 breaths/minute. Physical examination showed an anxious woman with cold extremities, tachycardia with no murmurs and increased effort of breathing with a benign abdominal examination. While in the emergency room, patient became haemodynamically unstable and her rhythm converted to ventricular tachycardia (VT) requiring successful cardioversion on three subsequent occasions following which she was transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) for VT storm.

Investigations

ECG revealed a wide complex tachycardia at a rate of 200 bpm (figure 1A), high sensitivity troponin T (TnT) was 1151 mg/L (normal <12 mg/L) and proBNP of 34 430 pg/mL (normal <125 pg/mL). COVID-19 testing with nasopharyngeal swab was negative and chest X-ray revealed bilateral opacities. Complete blood count showed leucocytosis, serum lactate 6.6 mmol/L (normal 0.5–2.2 mmol/L), alanine aminotransferase 6497 U/L (normal 7–38 U/L) and aspartate aminotransferase 14 739 U/L (normal 13–35 U/L).

Figure 1.

(A) Twelve-lead ECG shows wide complex tachycardia at a ventricular rate of approximately 200 beats/minute. (B) Twelve-lead ECG shows repolarisation abnormalities in leads II, III and aVF (blue arrows).

Treatment

Synchronised cardioversion with three successive shocks were performed for VT storm, with conversion to sinus rhythm with repolarisation changes in inferior leads (figure 1B). She was intubated and transferred to ICU on infusion of amiodarone and lidocaine. Over the next hour, she became progressively hypotensive with cold extremities requiring vasopressor support. A transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) revealed severely reduced biventricular function. Patient was transferred to the cardiac catheterisation laboratory, left and right heart catheterisation (LHC/RHC) performed. RHC revealed the patient to be in cardiogenic shock (table 1).

Table 1.

Right heart catheterisation measurements in patient 1

| Haemodynamics | |

| Right atrial pressure (mean) | 22 mm Hg (normal 4 mm Hg) |

| Right ventricular pressure (systolic/diastolic) | 31/20 mm Hg (normal 25/5 mm Hg) |

| Pulmonary artery pressure (systolic/diastolic) | 36/27 mm Hg (normal 25/10 mm Hg) |

| Pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (mean) | 24 mm Hg (normal 12 mm Hg) |

| Mixed venous oxygen saturation (%) | 35 (normal 70) |

LHC revealed total occlusion of the mid-distal right coronary artery (RCA) and 90% stenosis of the left anterior descending artery (LAD) (figure 2a and b). During an attempt to cross the RCA lesion with a guidewire, patient became asystolic. Advanced cardiac life support was instituted with return of spontaneous circulation in 3 min. A temporary pacemaker was implanted and three drug eluting stents were placed in the RCA with TIMI 2 flow post-revascularisation. Due to small diameter iliac arteries, an intra-aortic balloon pump was favoured over an Impella device for haemodynamic support for cardiogenic shock. Patient was transferred to the ICU with an augmented systolic blood pressure of 70 mm Hg.

Figure 2.

Coronary angiogram in left anterior oblique cranial view shows (A) complete occlusion of mid-distal right coronary artery (yellow arrow) and (B) stenosis of the left anterior descending artery (yellow arrow).

Outcome and follow-up

She became progressively acidotic despite haemodynamic support and her lactate climbed to 9.1 mmol/L, indicating worsening cardiogenic shock. Haemodynamic support was escalated to venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VA-ECMO). Patient remained on VA-ECMO for 6 days and was successfully decannulated on day 7. Repeat TTE revealed mildly decreased systolic function with an left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of 50%. Patient is currently recovering on the regular medical floor.

Case presentation 2

Patient 2 is an 82-year-old Caucasian woman who presented to the ED with worsening shortness of breath and leg swelling for 2 days. Her history included coronary artery disease (CAD) with remote angioplasty in 1995, peripheral vascular disease, hypertension, hyperlipidaemia, gastro-oesophageal reflux disease and chronic smoking. She reported waking up with chest pressure followed by vomiting 12 days prior to presentation. She was reluctant to visit the ED in ongoing viral pandemic and instead visited her primary care physician’s office. ECG during the office visit was unremarkable, her symptoms were considered atypical and she was sent home on pantoprazole. However, new onset worsening shortness of breath prompted her to report to the ED. On presentation, she had a blood pressure of 116/77 mm Hg, heart rate of 97 bpm, temperature of 97.1°F and respiratory rate of 21 breaths/minute. Physical examination revealed a systolic murmur in the third intercostal space along the left sternal border and crackles in the lung bases.

Investigations

ECG revealed ST-segment elevations in leads V2–V6 with Q waves in leads I, aVL, V5–V6 (figure 3). TnT was elevated to 0.718 ng/mL (normal 0–0.029 ng/mL) and proBNP was 13 346 pg/mL.

Figure 3.

Twelve-lead ECG shows ST-segment elevations in leads V2–V6 (blue arrows) with Q waves in leads I, aVL and V5–V6 (red arrows).

Treatment

Patient was administered aspirin 325 mg and clopidogrel 300 mg and started on a heparin infusion. An emergent TTE revealed severely decreased LV function with an EF of 30%, right ventricular systolic pressure of 57 mm Hg and a muscular ventricular septal rupture in the mid anteroseptal wall (figure 4). Patient underwent combined LHC/RHC with saturation study. RHC was significant for a pulmonary capillary wedge pressure of 28 mm Hg and LHC revealed acute total occlusion of the proximal LAD, diffuse 40% stenosis in the LCx, 70% stenosis of ramus intermedius and 40% stenosis of mid-RCA (figure 5A–C). A left ventriculogram confirmed a muscular ventricular septal rupture (VSR) (figure 5D). There was oxygen step up in the right ventricle and pulmonary artery and the Qp/Qs was 1.56 (table 2).

Figure 4.

Transthoracic echocardiogram still image of parasternal long axis view with colour flow shows ventricular septal rupture with left to right shunt (yellow arrow).

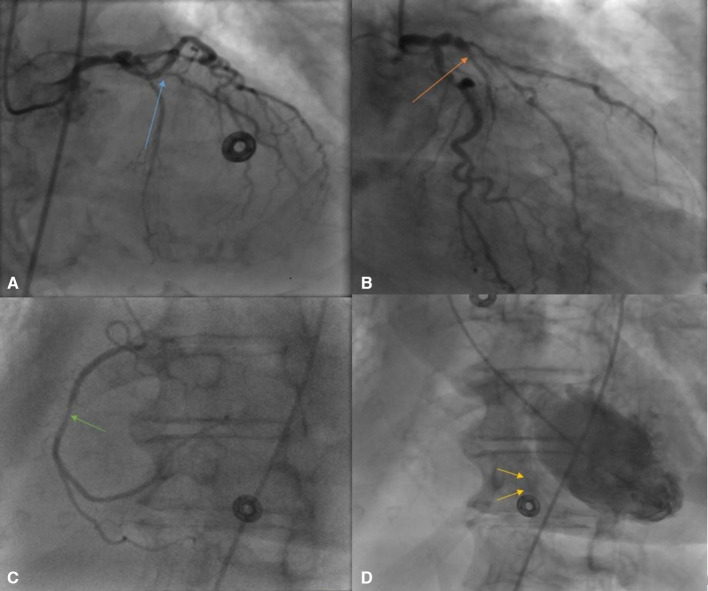

Figure 5.

(A) Coronary angiogram (CA) in left anterior oblique (LAO) cranial view shows total occlusion of proximal left anterior descending artery (LAD) (blue arrow). (B) CA in right anterior oblique (RAO) caudal view shows occlusion of proximal LAD (orange arrow). (C) CA in LAO cranial view shows 40% stenosis of right coronary artery (green arrow). (D) Left ventriculogram in LAO cranial view shows left to right shunt with dye in right ventricle (yellow arrows).

Table 2.

Right heart catheterisation measurements in patient 2

| Haemodynamics | |

| Right atrial pressure (mean) | 7 mm Hg (normal 4 mm Hg) |

| Right ventricular pressure (systolic/diastolic) | 48/7 mm Hg (normal 25/5 mm Hg) |

| Pulmonary artery pressure (systolic/diastolic) | 41/28 mm Hg (normal 25/15 mm Hg) |

| Pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (mean) | 28 mm Hg (normal 12 mm Hg) |

| Cardiac output | 5.6 L/min (normal 4–8 L/min) |

| Cardiac Index | 3.2 L/min/m2 (normal 2.5–4 L/min/m2) |

| Systemic vascular resistance | 986 dynes/sec/cm5 (normal 800–1200 dynes/sec/cm5) |

| Pulmonary vascular resistance | 129 dynes/sec/cm5 (normal 100–200 dynes/sec/cm5) |

| Oxygen saturations | |

| Inferior vena cava | 73% |

| Superior vena cava | 69% |

| Right atrium | 70% |

| Right ventricle | 72% |

| Pulmonary artery | 79% |

| Systemic | 95% |

| Qp/Qs | 1.56 |

Conservative management of the CAD was pursued of concerns for reperfusion injury of infarcted myocardium. Patient was discharged home on dual antiplatelet therapy, high-intensity statin, beta-blocker and daily furosemide.

Outcome and follow-up

On a follow-up visit, 1 week after discharge, patient reported worsening shortness of breath at rest. The symptoms were deemed secondary to increased shunting across the VSR. Her ECG showed Q waves in the inferior leads with residual ST-segment elevations. A cardiac MRI showed a small defect in the mid-anteroseptum (figure 6). Patient underwent percutaneous closure of VSR and tolerated the procedure well. Currently, the patient is recovering on the medical floor with no symptoms of angina or heart failure.

Figure 6.

Cardiac MRI in short axis view shows small ventricular septal defect (yellow arrow).

Global health problem list

There is a delay and decrease in presentations and timely interventions for medical emergencies like STEMI during the current era of COVID-19 crisis.

There is a resultant increase in mechanical and arrhythmogenic complications of STEMI as a presenting encounter, a rarity in the age of primary PPI (PPCI).

Healthcare providers need to be vigilant in identification and management of late presentations of STEMI and its complications.

Global health problem analysis

Acute STEMI is the major cause of mortality globally. It is well established that early diagnosis and immediate reperfusion with PPCI are the most effective to improve outcomes by lowering risk of post-STEMI complications.6 However, the COVID-19 outbreak has threatened to overwhelm healthcare systems worldwide, potentially overshadowing other medical emergencies, including STEMI.7 The data from various countries of Europe show a 25%–40% drop in STEMI presentations and admissions as compared with during the peak of pandemic.8–10 In the USA, a comparable decrease in STEMI presentations is reported in different states irrespective of the state’s burden of COVID-19.11 12 Findings from the Cleveland Clinic Foundation, a tertiary care referral centre, also show a consistent reduction in emergency transfers for STEMI and other time-dependent emergencies coinciding with the COVID-19 pandemic.13 Garcia et al analysed and quantified STEMI activations for nine high volume cardiac catheterisation laboratories in the USA and found a 38% decrease in STEMI activations of cardiac catheterisation laboratories across the US during the COVID-19 period.14 A recent international survey was conducted by the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) looking at the perception of cardiology care providers with regards to STEMI admissions to their hospitals. The investigators found a significant reduction in number of STEMI admissions (>40%), an increase in presentations beyond the optimal window for PPCI or thrombolysis (>40%).1 The data from Hong Kong reported an increase in time taken for STEMIs to reach the hospital from 82.5 min to 318 min during the pandemic.15 As a consequence of this latest trend of STEMI-delayed presentation, the number of mechanical and arrhythmogenic complications of STEMI has seen a rise, which is a rare occurrence in the age of PPCI.16 It corresponds with our clinical experience with the forementioned patients who were reluctant to visit ED as they would have in normal circumstances. Both of our patients had good family and social support, healthcare insurance to cover for medical expenses, but still evaded medical care for a time-dependent medical emergency. They belong to the Cuyahoga county, one of the three largest counties of Ohio, which has about 7400 hospital beds at 23 registered hospitals, 7427 physicians and 13 PCI-capable healthcare facilities serving a population of approximately 12 million.17 The decreased rate of hospital presentations for STEMI has paralleled an increased incidence of patients presenting late after STEMI onset.18 Physicians around the world are reporting severe complications of STEMI from delayed presentations or lack of reperfusion2 19–26 (table 3).

Table 3.

Literature review of delayed presentations of STEMI with complications during COVID-19 pandemic

| Author | Country | Publication month/year | Age/sex | Comorbidities | Clinical presentation | COVID-19 status | ECG/ cardiac enzymes | Multimodality imaging | Invasive findings | Management | Clinical course | Outcome |

| Moroni et al2 | Italy | March/2020 | 64/M | Not reported | Left lower limb pain, cyanosis and paraesthesia for 10 days. CP and SOB for 10 days | NR | Q waves and STE in inferior leads | TTE: severe LV dilation, systolic dysfunction and apical thrombus. CTA: LAD occlusion, thromboembolic material in femoral arteries | Not performed | Emergent amputation of left lower limb | Cardiogenic shock necessitating inotropes and IABP | Recovered and discharged from ICU |

| Moroni et al2 | Italy | March/2020 | 65/F | Not reported | Progressive SOB for 5 days, hypotension and respiratory distress. Episode of epigastric tightness few days earlier treated with antacids at home | NR | Q waves and STE anterior leads | CXR: acute pulmonary oedema. TTE: severe LV dysfunction, apical aneurysm, anteroseptal and anteroapical dyskinesia. CTA: critical LAD stenosis | Not performed | Intravenous diuretics, inotropic support and non-invasive ventilation | Not significant | Transferred to cardiology ward |

| Moroni et al2 | Italy | March/2020 | 60/M | Not reported | Hypotension, diaphoresis, respiratory distress. Four-day history of crushing chest pain | NR | STE and Q waves in anterior leads | TTE: severe LV dysfunction with anteroseptal, anteroapical and lateral akinesia | LHC: CTO of proximal RCA and acute occlusion of proximal LAD | LHC: no-reflow phenomenon after stent implantation to LAD and ventricular fibrillation requiring defibrillation with I&V | ROSC, cardiogenic shock necessitating inotropes and mechanical support with Imeplla CP | Died after few days |

| Gadella et al19 | Spain | April/2020 | 65/F | Dyslipidaemia, chronic hepatitis C, cervical cancer with surgical removal and active smoking | Typical CP for 24 hours, low grade fever and dry cough, and tachypnoea | + | Acute evolving anterior MI | CXR: bilateral patchy infiltrates. TTE: extensive LV wall motion abnormalities and severe systolic dysfunction | Urgent angiography and PCI deferred and considered elective after recovery from COVID-19 | Aspirin, ticagrelor, empiric ceftriaxone and azithromycin, and hydroxychloroquine | Cardiogenic shock in 24 hours. New-onset holosystolic murmur and 13 mm apical VSR. | Patient managed conservatively and died the following day |

| Ullah et al20 | USA | May/2020 | 36/M | No comorbidities | Unresponsive at home and last seen normal 15 hours ago | + | STE V2–V4. TnT elevated | TTE: extensive septal, anterior and apical akinesia with apical LV thrombus and EF of 35% (normal >55%). CXR and CT of the chest: multifocal infiltrates | LHC: 99% occlusion of LAD | DES in LAD, aspirin, clopidogrel, atorvastatin, carvedilol and lisinopril | Refused further work-up and discharged home | Not reported |

| Dash et al21 | India | June/2020 | 59/F | HTN, DM, CAD with STEMI in March 2020 | Dyspnoea for 2 days, tachycardia and hypoxia | NR | Left-axis deviation with Qs in anterior leads; TnT positive | Not reported | Not performed | Non-invasive ventilation, inotrope infusions, heparin, antiplatelets, lipid-lowering agents, antianginals and antibiotics | Gradual oliguria followed by anuria with severe metabolic acidosis and refractory hypotension | Cardiac arrest and died |

| Dash et al21 | India | June/2020 | 58/F | DM and HTN | Anginal chest pain, dyspnoea and autonomic symptoms | NR | Qs complex in V1–V4. TnT + | CXR: cardiomegaly with bilateral alveolar opacities | Not performed | Oxygen, heparin, diuretics, antiplatelets, insulin and lipid-lowering agents | Responded well with symptom relief | Discharged from hospital |

| Dash et al21 | India | June/2020 | 69/M | Not reported | Chest pain for more than 12 hours | NR | STE I, aVL with reciprocal ST depressions | Not performed | Ostial LAD 100% occlusion with poor retrograde filling from RCA | Repeated thrombosuction of LAD and DES to LAD | Managed on antiplatelets and inotropes, and developed refractory pulmonary oedema requiring I&V | Died after 12 hours |

| Mitevska et al22 | North Macedonia | May/2020 | 47/M | HTN, DM II, smoking and increased body weight | Recurrent episodes of CP for 2 days prior to hospitalisation | – | Sinus tachycardia with STE in leads V2–V6, I, II, III and aVF. HsTnt 6385 ng/mL (normal <15 ng/mL) | TTE: akinesia of apex, anterior wall, mid-apical septal wall and global reduction in LV function with EF 35% | LHC: 99% stenosis of mid LAD, CTO of LCx and OM1, and 95% stenosis of RCA | DES to culprit lesion in mid LAD followed by another stage procedure with DES to proximal RCA on day 3 of hospitalisation | Angina relieved and STE resolution | Discharged on day 7 of hospitalisation and clinically stable |

| El Sakr and Marshall23 | USA | June/2020 | 64/F | 40-pack year history of tobacco use and mild COPD | CP and SOB for 1 day. Muscle and back aches for 5 days | – | STE in II, III, aVF, V3–V6 with reciprocal changes in I and aVL | TTE: inferior, inferoseptal, inferolateral and proximal-mid anteroseptal wall hypokinesis | LHC: occluded mid PCA, LVEDP 34 mm Hg (normal 19 mm Hg) and VSD. RHC: 73% sat on RV c/w step up and shunt, PCWP of 26 mm Hg (normal 12 mm Hg) | IABP support, rotational atherectomy and DES to RCA. Cardiac CT: VSD in basilar inferior septum with patch repair on day 4, mechanical support escalated to ECMO and Impella for cardiogenic shock | Postoperative bleeding requiring reoperation | Died |

| Joshi et al24 | USA | June/2020 | 72/F | Dyslipidaemia and CAD with PCI in 2002 | Substernal chest heaviness, light headedness and patient presentation 14 hours after persistent symptoms | NR | STE in inferior leads with Q waves reciprocal ST depressions and elevated TnT | CTA: insignificant |

LHC: occlusion of mid RCA and ventriculogram showed VSR. RHC: O2 step up in RV and Qp:Qs 2.2:1 | DES to mid RCA | Patient wished comfort measures | Died |

| Alsidawi et al25 | USA | June/2020 | 67/F | CAD with prior LCx stent | CP, delayed seeking medical attention and presented after 14 hours | NR | Inferior STE with Q wave and elevated Tnt | TTE: EF 50% and hypokinesis of inferior and inferoseptal myocardium | LHC: dominant RCA totally occluded | Aspiration thrombectomy with symptom resolution | Discharged and presented with shock and new murmur 5 days later and found to have VSR | Complex VSD repair and ICU admission |

| Alsidawi et al25 | USA | June/2020 | 62/F | HTN and MS | Chest pain for 4 days, dyspnoea and fever. Systolic thrill on examination | – | Anterior STE with Q waves | TTE: EF 35% with LAD WMA, apical VSR | RHC:Qp:Qs 1.5:1 | Patient elected non-invasive management | Transitioned to hospice care | Not reported |

| Otero et al26 | USA | July/2020 | 69/M | HTN, HD, DM II, tobacco use and aortic aneurysm | Exertional chest pain of unknown duration | – | Posterior STE | TTE: EF 25% and small circumferential pericardial effusion with visible thrombus | LHC: 100% occlusion of LCx and 90% occlusion of LAD. Unable to wore or balloon due to extensive thrombus burden | Initially received tenecteplase, aspirin and clopidogrel | Transferred to ICU on IABP. Medical management of STEMI. Avoidance of anticoagulation due to haemorrhagic pericardial effusion due to tenecteplase | Repeat TTE with resolution of pericardial effusion, staged PCI of LAD and discharged on day 19 |

| The present report of patient 1 | USA | 2020 | 62/F | Cigarette smoking, hyperlipidaemia and obesity | Nausea, diarrhoea and chest pain for 2 weeks. SOB for 1 day. | – | Wide complex tachycardia. Elevated hsTnt and Tnt | TTE: severely reduced biventricular function | RHC: cardiogenic shock. LHC: total occlusion of RCA and 90% stenosis of LAD | Asystole during PCI and worsening cardiogenic shock with VA-ECMO support | Successful decannulation from VA-ECMO on day 7 and repeat TTE: LVEF 50% | Recovering on medical floor |

| The present report of patient 2 | USA | 2020 | 82/F | CAD, vascular disease, HTN, hyperlipidaemia and smoker | SOB and leg swelling for 2 days. New systolic murmur | – | STE V2–V6 with Q waves. Tnt elevated | TTE: LVEF 30% and muscular VSR | RHC: O2 step up in RV, Qp:Qs: 1:56. LHC: total occlusion of LAD, stenosis in LCx, RCA and muscular VSR | Antiplatelets, statin and anticoagulation | Progressive SOB on discharge and underwent percutaneous closure of VSR | Recovering well on medical floor |

CAD, coronary artery disease; CP, chest pain; CXR, chest X-ray; DM, diabetes mellitus; EF, ejection fraction; HTN, hypertension; IABP, intra-aortic balloon pump; ICU, intensive care unit; I&V, intubation and ventilation; LAD, left anterior descending artery; LHC, left heart catheterisation; LV, left ventricle; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; RCA, right coronary artery; RHC, right heart catheterization; ROSC, return of spontaneous circulation; SOB, shortness of breath; STE, ST-segment elevations; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; TnT, troponin T; TTE, transthoracic echocardiogram; VA-ECMO, venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; VSD/R, ventricular septal defect/rupture.

Based on our review we hypothesise:

Patients are not presenting to the hospital for medical emergencies

Patients with angina symptoms and with/suspected/without COVID-19 are presenting late to the hospital.

Delays in patients seeking medical care, delay in medical testing for suspected patients and delay due to severe COVID-19 related symptoms are observed during the period of crisis.2 19 20 Physicians are observing worsening left ventricular functions, massive myocardial infarctions, life-threatening arrhythmias and cardiogenic shocks as complications of STEMI, a rarity in the age of PPCI.2 19–26 It has translated into an increased mortality, prolonged admissions to the ICU, a grave concern in these times of scarce resources. The observed phenomenon can be attributed to numerable patient and healthcare-related factors.27 28

Community-related factors

The establishment of COVID-19 hospitals is making many patients reluctant to come to the hospital. Patient 1 had concerns whether the Cleveland Clinic was transformed into a COVID-19 hospital. Such misconceptions and confusions along with alterations in patient behaviours of fear of contracting nosocomial COVID-19 are a potential culprit.2 Moreover, patient 2 attempted to self-medicate herself with pantoprazole until her symptoms got severe. Reduced family contact and supports during lockdown and the stress associated with stay-at-home orders are potential factors for delayed and decreased presentations for time-dependent medical emergencies.19 Low levels of exertion at home might not trigger cardiac symptoms and impaired manifestations of STEMI related to neurotropic and neuroinvasive symptoms of COVID-19 can play a role in those affected with the disease.16 17 19 Misinterpretation of STEMI being relatively benign compared with COVID-19 disease along with the fear of infection spread via hospitalised patients and healthcare workers is a common perception among community dwellers.22

Healthcare-system-related factors

The COVID-19 pandemic has put tremendous stress on the healthcare system across the world, even affecting countries with established medical resources. It has disrupted the established care pathways and work flow due to overwhelmed EDs. There is a higher threshold of ED referrals by outpatient care providers, as observed with patient 2. Healthcare personnel safety concerns are undeniable, especially with limited staffing resources from high healthcare worker infection rates.27 The increasing trend of using fibrinolytic therapies to manage STEMIs in the ED, in an attempt to mitigate system-based delays, has also been described as a causative for re-emergence of rare complications.26

Proposed steps to be implemented to halt this trend

There has been press releases from ESC, American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association, and healthcare experts have voiced concern in major newspapers for public awareness.29–33 Many patients, their families and their caregivers have come forward to share their experiences during this period of crisis.33 34 On the media page of the Cleveland Clinic, cardiovascular experts have explained in simple terms the telltale signs of a heart attack as well as how delaying heart care in this COVID-19 surge can lead to devastating consequences.35 As the pandemic continues, it is imperative to commit stern steps of mass education and public awareness.3 27 28 36 Identification and correction of internal process delays is vital. The utilisation of telemedicine strategies, according to recent reports, was associated with improvement of STEMI time of diagnosis and outcomes during the period of crisis.37 Further studies comparing telemedicine to the conventional way of managing patients with ACS are need of the hour.

Altogether, these findings should be taken into serious consideration and effective plans drawn and implemented in case a second wave of the pandemic develops as lockdown restrictions are currently eased worldwide.

Learning points.

Several community and healthcare-system-related factors delay and decrease the presentation and intervention for time-dependent non-communicable diseases such as ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) in the era of COVID-19 crisis.

As a consequence of these delays, healthcare providers should be vigilant in encountering and managing devastating complications of non-revascularised STEMI, rarely encountered in the age of primary percutaneous coronary intervention.

We present two intriguing cases of delayed presentation of STEMI in the era of COVID-19 pandemic with arrhythmogenic and mechanical complications, with a prolonged and arduous clinical course.

This review focuses on several important patient and healthcare-system-related factors playing a vital role in this perplexing observation.

Several vital steps are postulated to halt this dangerous trend and assure the safety and well-being of general population in case a second wave of the pandemic develops.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the significant contribution from Dr Emad Dean Nukta, who provided us with valuable inputs regarding the interventional management of the patients. We are grateful to both our patients for giving us permission to write up their cases.

Footnotes

Twitter: @TahaAhmedMDCcf

Contributors: TA: designed the study, performed the literature review, drafted the manuscript, formulated the tables and reviewed the manuscript. SHL: performed the literature review, contributed to the discussion and suggested pertinent modifications. SK: contributed to the case presentation and discussion, revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content and gave final approval for the version published. GVS: managed the cases, contributed to the case presentation and did a critical review and supervision.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Pessoa-Amorim G, Camm CF, Gajendragadkar P, et al. Admission of patients with STEMI since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic: a survey by the European Society of cardiology. Eur Heart J Qual Care Clin Outcomes 2020;6:210–6. 10.1093/ehjqcco/qcaa046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moroni F, Gramegna M, Ajello S, et al. Collateral damage: medical care avoidance behavior amomg patients with myocardial infarction during the COVID-19 pandemic. JACC Case Rep 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ardati AK, Mena Lora AJ, Lora AJM. Be prepared. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2020;13:e006661. 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.120.006661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Exner R. How many hospital beds are near you? details by Ohio County, 2020. Available: https://www.cleveland.com/datacentral/2020/03/how-many-hospital-beds-are-near-you-details-by-ohio-county.html

- 5.Naquin T. Cuyahoga County reports most coronavirus deaths in the state, 2020. Available: https://fox8.com/news/coronavirus/cuyahoga-county-reports-most-coronavirus-deaths-in-the-state/

- 6.Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, et al. 2017 ESC guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation: the task force for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation of the European Society of cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2018;39:119–77. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rodriguez-Leor O, Cid-Alvarez B. Stemi care during COVID-19: losing sight of the forest for the trees. JACC Case Rep 2020. 10.1016/j.jaccas.2020.04.011. [Epub ahead of print: 23 Apr 2020]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rangé G, Hakim R, Motreff P. Where have the STEMIs gone during COVID-19 lockdown? Eur Heart J Qual Care Clin Outcomes 2020:qcaa034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Metzler B, Siostrzonek P, Binder RK, et al. Decline of acute coronary syndrome admissions in Austria since the outbreak of COVID-19: the pandemic response causes cardiac collateral damage. Eur Heart J 2020;41:1852–3. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rodríguez-Leor O, Alvarez BC, Ojeda S, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare activity in interventional cardiology in Spain. REC Interv Cardiol 2020;2:82–9. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Braiteh N, Rehman WU, Alom M, et al. Decrease in acute coronary syndrome presentations during the COVID-19 pandemic in upstate New York. Am Heart J 2020;226:147–51. 10.1016/j.ahj.2020.05.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zitelny E, Newman N, Zhao D. STEMI during the COVID-19 Pandemic - An Evaluation of Incidence. Cardiovasc Pathol 2020;48:107232. 10.1016/j.carpath.2020.107232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khot UN, Reimer AP, Brown A, et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on critical care transfers for ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction, stroke, and aortic emergencies. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2020:CIRCOUTCOMES120006938. 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.120.006938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garcia S, Albaghdadi MS, Meraj PM, et al. Reduction in ST-segment elevation cardiac catheterization laboratory activations in the United States during COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Coll Cardiol 2020;75:2871–2. 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tam C-CF, Cheung K-S, Lam S, et al. Impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak on ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction care in Hong Kong, China. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2020;13:e006631. 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.120.006631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Trabattoni D, Montorsi P, Merlino L. Late STEMI and NSTEMI patients' emergency calling in COVID-19 outbreak. Can J Cardiol 2020;36:1161.e7–1161.e8. 10.1016/j.cjca.2020.05.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ohio County profiles. Available: https://development.ohio.gov/files/research/C1019.pdf

- 18.Walsh MN, Sorgente A, Frischman DL, et al. The COVID-19 pandemic and cardiovascular complications what have we learned so far? JACC Case Rep 2020;2:1235–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gadella A, Sastre Miguel Ángel, Maicas C, et al. St-Segment elevation myocardial infarction in times of COVID-19: back to the last century? A call for attention. Rev Esp Cardiol 2020;73:582–3. 10.1016/j.rec.2020.04.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ullah W, Sattar Y, Saeed R, et al. As the COVID-19 pandemic drags on, where have all the STEMIs gone? Int J Cardiol Heart Vasc 2020;29:100550. 10.1016/j.ijcha.2020.100550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dash S, Dhuman AK, Pandey P, et al. Late presentation of acute coronary syndrome during COVID-19. Med J DY Patil Vidyapeeth 2020;13:269–73. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mitevska I, Bushljetikj O, Grueva E, et al. Delayed Presentation of Acute ST Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction Complicated with Heart Failure in the Period of COVID-19 Pandemic - Case Report. Clinical Case Rep 2020;3. [Google Scholar]

- 23.El Sakr FH, Marshall JJ. Delayed STEMI presentation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Available: https://www.acc.org/latest-in-cardiology/articles/2020/06/05/09/51/delayed-stemi-presentation-during-the-covid-19-pandemic

- 24.Joshi S, Kazmi FN, Sadiq I, et al. Post-Mi ventricular septal defect during the COVID-19 pandemic. JACC Case Rep 2020. 10.1016/j.jaccas.2020.06.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alsidawi S, Campbell A, Tamene A, et al. Ventricular septal rupture complicating delayed acute myocardial infarction presentation during the COVID-19 pandemic. JACC Case Rep 2020. 10.1016/j.jaccas.2020.05.049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Otero D, Singam NSV, Barry N, et al. Complication of late presenting STEMI due to avoidance of medical care during the COVID-19 pandemic. JACC Case Rep 2020. 10.1016/j.jaccas.2020.05.045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chieffo A, Stefanini GG, Price S, et al. EAPCI position statement on invasive management of acute coronary syndromes during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur Heart J 2020;41:1839–51. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ashraf S, Ilyas S, Alraies MC. Acute coronary syndrome in the time of the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur Heart J 2020;41:2089–91. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fear of COVID-19 keeping more than half of heart attack patients away from hospitals, 2020. Available: https://www.escardio.org/The-ESC/Press-Office/Press-releases/Fear-of-COVID-19-keeping-more-than-half-of-heart-attack-patients-away-from-hospitals

- 30.Coronavirus and your heart: don’t ignore heart symptoms. Available: https://www.cardiosmart.org/coronavirus/content/do-not-ignore-heart-symptoms

- 31.Kolata G. Amid the coronavirus crisis, heart and stroke patients go missing, 2020. Available: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/25/health/coronavirus-heart-stroke.html

- 32.Knocking down fears, myths and misinformation about calling 911 in the pandemic. Available: https://www.heart.org/en/coronavirus/coronavirus-covid-19-resources/knocking-down-fears-myths-and-misinformation-about-calling-911-in-the-pandemic

- 33.Wood S. Dire, unusual STEMI complications blamed on COVID-19 Hospital avoidance, 2020. Available: https://www.tctmd.com/news/dire-unusual-stemi-complications-blamed-covid-19-hospital-avoidance

- 34.Galante A. After man, 38, dies of heart attack, wife shares urgent message: Go to the ER. Today Health & Wellness, 2020. Available: https://www.today.com/health/heart-attack-covid-19-why-young-father-didn-t-go-t184278

- 35.Seek care for heart emergencies during COVID-19, 2020. Available: https://newsroom.clevelandclinic.org/2020/04/23/seek-care-for-heart-emergencies-during-covid-19/

- 36.Roffi M, Guagliumi G, Ibanez B. The obstacle course of reperfusion for ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction in the COVID-19 pandemic. Circulation 2020;141:1951–3. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.047523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Swain E. Telehealth strategy improves STEMI care in Latin America, 2020. Available: https://www.healio.com/news/cardiology/20200518/telehealth-strategy-improves-stemi-care-in-latin-america