Abstract

A 60-year-old man was referred to the interventional pulmonology clinic with a large right-sided intraparenchymal lung mass and a second, smaller lesion in the left lower lobe, accompanied by intermittent haemoptysis, fever, chills, productive cough of white phlegm as well as dizziness and weakness. He had presented previously and was being evaluated for the possibility of malignancy. Investigations had revealed ‘hooklets’ (protoscolices) of hydatid cysts, most likely representing the parasite Echinococcus. Successful surgical excision of the affected lobe, lung decortication, partial pleurectomy and pneumolysis of the adhesions was performed, along with long-term antiparasitic therapy. The initial differential diagnosis for this patient was challenging and required multimodal investigations. The patient made good recovery and continued to be followed by infectious disease specialists for management of antiparasitic therapy.

Keywords: infectious diseases, medical management, respiratory medicine

Background

Zoonotic diseases in the USA are at a lower prevalence than noted worldwide, including cystic echinococcosis (CE). CE, also known as hydatid disease, is caused by infection with the larval stage of Echinococcus granulosus, a tapeworm found in dogs and sheep, cattle, goats and pigs.1 Most commonly, working dogs involved in raising sheep serve as the definitive host and vector for human transmission, especially if allowed to eat the offal of the infected sheep, which allows the growth of the hydatid cysts. Diagnosis is based on imaging and confirmed by serology for patients typically presenting from an endemic area.2 Few cases in Northern America are documented, and even fewer have been noted without hepatic involvement. This case is focused on broadening the differential diagnosis based on CT and bronchoscopic ultrasound evaluation.

Case presentation

A 60-year-old previously healthy man with no tobacco use history, no previous records, or imaging, presented to the interventional pulmonary clinic with a several week history of intermittent haemoptysis, fevers and chills. At that time, he resided in Arizona, where he sometimes helped with the family business of herding sheep and was also in contact with sheepdogs on a seasonal basis only. The patient was initially evaluated in a nearby rural emergency department in New Mexico, where he was noted to have an approximately 6.7×5.9×4.8 cm right-sided intraparenchymal lung mass on imaging, with no prior chest imaging to compare to. The mass was noted to have locules of air with predominant fluid attenuation and a thick wall.

On examination, he was normotensive with a blood pressure of 127/71 mm Hg, afebrile with a temperature of 37.1°C and a heart rate of 85 bpm. Physical examination revealed tachypnoea and left rales present. All other systems were unremarkable. His initial laboratory panel and presentation were not reflective of an infectious aetiology with a white blood cell (WBC) of 10.7×109/L, lactate of 1.1 mmol/L and peripheral eosinophil count of 0.2×109/L.

Investigations

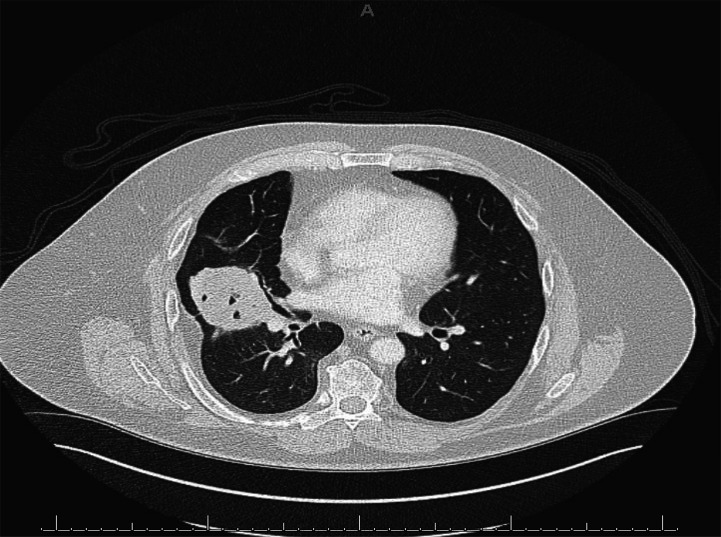

A repeated CT of the chest with contrast was performed 2 months following the initial examination with a concern for necrotic carcinoma, specifically squamous cell carcinoma. There was one other 1.2 cm nodule present in the left lower lobe of similar representation, but no other lesions, ground-glass opacities or consolidations were noted on imaging (figures 1 and 2). At that time, a bronchoscopy was performed. Airway inspection revealed Saber sheath pathology of the trachea with an abnormal endobronchial cystic/polypoid smooth mass found in the right middle lobe obstructing the lateral subsegment. The mass was biopsied with forceps and needle following the use of argon plasma coagulation to decrease the size of the mass (figure 3). Once the fibrous wall was biopsied, fluid extravasated from the cyst, which appeared serious and at times purulent. The mass was visualised on endobronchial ultrasound and did not appear hypervascular but was heterogeneously layered. The findings were consistent with necrotic, fibrous pulmonary plug usually seen with infection or certain malignancies. Pathology and cytology studies from the biopsies obtained revealed laminated cyst material consistent with hydatid cyst suggestive of Echinococcus. Additional CT imaging was then performed and ruled out liver or brain involvement.

Figure 1.

Right middle lobe mass noted on coronal CT without contrast.

Figure 2.

Right middle lobe mass noted on axial cut of CT without contrast.

Figure 3.

Flexible bronchoscopy imaging of cystic mass protruding from the lateral subsegment along with image following forceps biopsy.

Initial bronchoscopic laboratory evaluation returned as equivocal, with bronchoalveolar lavage showing no lymphocyte or eosinophilic predominance, and moderate WBCs with mixed upper respiratory flora. Not until pathologic review, did we come to realise that the mass was negative for fungal elements on a grocott methenamine silver (GMS) stain and in fact a triple-layer laminated cyst, confirmed to be a hydatid cyst with echinococcal hooklets (E. granulosus).

Differential diagnosis

The differential for haemoptysis with an intraparenchymal pulmonary lesion is broad and we focused on both infectious and malignant lesions prior to bronchoscopy. Our first inclination was a bacterial abscess, gas fluid cavity, which can often be found with presenting symptoms of fever, cough and haemoptysis possibly suggesting erosion into a bronchial vessel. Bacterial abscesses are generally round in shape and demonstrate a thick wall on imaging, not the thin triple layer observed in this case. Other infectious aetiologies include pulmonary mycetomas, which are not uncommon culprits for haemoptysis such as coccidioidomycosis, as the patient resided in the American Southwest, an endemic region for this dimorphic fungus. Pulmonary aspergillosis is a ubiquitous mould associated with hyphae and spores called conidia that are easily airborne and can present as a mass in immune-compromised patients, with imaging findings such as a ‘halo sign’ representing haemorrhage around the lesion.

Other infectious considerations were pulmonary actinomycosis, but the organism typically is seeded through the oropharynx, attributable to poor dentition with abscesses. This patient did not have any dental issues. Pulmonary nocardiosis is typically an isolated lesion as in this case, and an opportunistic infection affecting immune-compromised patients, unlike this patient. Pulmonary tuberculosis was a concern given haemoptysis, along with lung mass seen on CT imaging with small satellite lesions.

Malignancy such as squamous cell carcinoma secondary to its gas-forming nature of mass seen on imaging; along with cough, haemoptysis, surrounding lung parenchyma and its rounded size.

Postpneumonic pneumatocele appearance may vary but can be thin-walled cystic spaces within lung parenchyma. Pneumatoceles have little if any fluid content.

Treatment

The patient underwent successful right middle lobe lobectomy, right lung decortication, partial parietal pleurectomy, mediastinal lymph node dissection and pneumolysis of adhesions. Histopathological evaluation of the parenchymal tissue only showed florid chronic, acute and granulomatous inflammation with focal fibrosis and dystrophic calcification. It was presumed that drainage during the endobronchial biopsy cleared the organism, and repeated analysis of the initial biopsy by the pathologist confirmed this, showing scolices (the anterior ends of the tapeworm).

The respiratory therapy team was consulted for aggressive management and lung rehabilitation. Cefazolin intravenous was given preoperatively and postoperatively as standard surgical prophylaxis measures. Albendazole by mouth was resumed immediately after the surgery. The infectious diseases service was consulted for long-term antiparasitic therapy management and follow-up. It was recommended to continue albendazole 400 mg by mouth two times per day for a total duration of 6 months secondary to concern for cyst spillage during the initial bronchoscopy. On the fifth postoperative day, the patient was discharged home with ongoing support from his family.

Outcome and follow-up

At 3-month postresection, the patient was seen by the infectious diseases clinic. He reported feeling well and gradually regaining strength although with some ongoing nerve pain at the surgical incision site. The thoracotomy site looked well healed on physical examination. The plan is to continue albendazole for a minimum of 6 months. Given that there continues to be an additional left lower lobe subpleural nodule stable in size, which was present preoperatively, the plan is to repeat CT imaging in 3 months postend of treatment to ensure no new lesion development or need for extension of the treatment duration or additional surgical interventions. The patient will continue to follow with our infectious diseases clinic.

Discussion

The lung is the second most common site of involvement with E. granulosus in adults after the liver (up to 30% of cases), and the most common site in children.3

Cystic lung disease carries a varied differential and for the bronchoscopist, procuring an adequate tissue sample is important, as this will preclude an oftentime-complicated surgical biopsy. However, expanding the differential prior to intervention is of utmost importance. In our case, we were fortunate that following transbronchial forcep biopsy and fine-needle aspiration that the cystic contents did not result in anaphylaxis, which is a common complication of sac rupture. The WHO has outlined imaging criteria based on the parasite’s characteristic germinal capsule layer and a central ‘hydatid’ cavity. The outer layer of the hydatid cyst is acellular, and unless ruptured, the contents may not be appropriately evaluated histologically. This again does raise the risk of anaphylaxis. The WHO has recommended ultrasound as the primary imaging modality to aide in the diagnosis of E. granulosum.4 5 Given the rarity of disease in the USA, bronchoscopist may elect to perform fine-needle aspiration of the cystic contents if a multilayer mass is seen.

Patient’s perspective.

I was lucky to be seen right away when I started coughing up blood. I want to say that the procedures were scary but not painful, and that each doctor was able to explain to me what was going on. I am feeling well now and I am back to work thanks to the treatments.

Learning points.

This is a case of an uncommon parasitic infection in a non-endemic area. Echinococcus is most often transmitted to humans by exposure to sheep and/or sheepdogs through faecal oral route and acts as intermediate hosts.

The encapsulated organism may prevent a generalised systemic inflammatory response, such as peripheral eosinophilia, as in this case.

Imaging characteristics can key the provider into a diagnosis before pathological evaluation, including CT evidence of a well-rounded triple-layered cystic mass representing the pericyst, ectocyst and endocyst.

Multiple investigations were required to accurately diagnose this case given the unusual presentation. If there is a suspicion for parasitic lung infection, all efforts should be made not to disseminate contents into the airway given the anaphylaxis risk.

Duration of antiparasitic therapy is multifactorial. Guidelines provide an estimated total duration; however, other patient-specific factors may influence providers towards prolongation of treatment.4 6

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the University and our wonderful pulmonary diagnostics team.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors have read and approved the manuscript. WPD and NV contributed to patient care and manuscript preparation. WPD, NV and MGC took part in discussions about the patient and were involved in manuscript preparation and editing. WPD and MGC were involved in manuscript editing.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Center for Disease Control and Prevention Parasites – echinococcosis, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stojković M, Weber TF, Junghanss T. Clinical management of cystic echinococcosis: state of the art and perspectives. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2018;31:383–92. 10.1097/QCO.0000000000000485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gottstein B, Reichen J, disease Hlung. Hydatid lung disease (echinococcosis/hydatidosis). Clin Chest Med 2002;23:397–408. 10.1016/S0272-5231(02)00007-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brunetti E, Kern P, Vuitton DA, et al. Expert consensus for the diagnosis and treatment of cystic and alveolar echinococcosis in humans. Acta Trop 2010;114:1–16. 10.1016/j.actatropica.2009.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gru B, Schmidgerger J, Drews O, et al. Imaging in alveolar echinococcosis (AE): comparison of Echinococcus multilocularis classification for computed-tomography (EMUC-CT) and ultrasonography (EMUC-US). Radiol Infect Dis 2017;4:70–7. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jerray M, Benzarti M, Garrouche A, et al. Hydatid disease of the lungs. study of 386 cases. Am Rev Respir Dis 1992;146:185–9. . 10.1164/ajrccm/146.1.185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]