This editorial refers to ‘Loss of life expectancy from air pollution compared to other risk factors: a worldwide perspective’, by J. Lelieveld et al., pp. 1910–1917.

‘We all inhabit this small planet. We all breathe the same air. We all cherish our children’s future. And we are all mortal’.

John F. Kennedy. Address to the American University advocating world peace, 10 June 1963.

Mortality is very much in our minds at present. At the time of writing (April 2020), the world faces the COVID-19 pandemic having affected millions of individuals and claimed hundreds of thousands of deaths.1 For most, the pandemic is unprecedented, resulting in the shutdown of cities, closures of businesses and schools, extremely limited air travel and, across the world, we face a dramatic departure from everyday life. For many, the daily routine now includes a check of their nation’s death toll, following the trajectory of the fateful line in the hope of seeing the plateau.

Yet viruses are not the only airborne ‘killers’. The last decade has seen an increasing realization of the persistent and growing burden on health caused by air pollution. Air pollution is a complex mix of chemical species, but it is the tiny particles that dominate associations with ill health. Particulate matter (PM) is measured worldwide by two size categories: PM10 and PM2.5 (PM with a diameter of 10 µm or less, and 2.5 µm or less, respectively). In reality though, PM is a mixture of particles of different composition and size. The smallest of these particles overlap the size range of viruses, allowing them to penetrate deep into the lung, and into the circulation,2 carrying a range of active chemicals into the body to induce inflammation and oxidative stress.3 Exposure to PM is now linked to diseases of almost all organs in the body.4,5 Consequently, it is also associated with mortality, especially from cardiovascular causes such as ischaemic heart disease and stroke which account for 40–60% of deaths attributed to air pollution.6–8 While the all-pervasive and insidious nature of air pollution does not trigger the same fear as a sudden infectious pandemic, the mortality attributed to air pollution is nothing short of staggering. Globally, air pollution is associated with several million excess (‘premature’) deaths every single year.7–9 In light of such statistics, it is not surprising that there is something of an obsession with mortality figures for air pollution. Air pollution per se is rarely regarded as the direct cause of death; instead, these figures are a population average derived from estimates of both the chronic (the slow eroding of normal physiology and acceleration of disease) and acute effects (e.g. the precipitation of these pathologies to trigger an atherothrombotic event) of air pollution. Nonetheless, these estimates of mortality have practical value in conveying the magnitude of the health effects of air pollution to the general public and to policy makers.

Lelieveld et al.,10 expand on their previous estimates8 of global mortality attributed to air pollution derived from cardiovascular and respiratory conditions. The investigators use the Global Exposure Mortality Model (GEMM), that makes use of contemporary (2015) data from 41 cohorts in 16 (primarily European and North American) countries, to assess the mortality linked to PM2.5 and ozone (a common gaseous air pollutant associated with health effects, albeit less consistently than PM). The model has the advantages of incorporating the age-structure of the populations and data from higher levels of air pollution in China to formulate dose–response functions, rather than extrapolation from data based on second-hand smoke exposure. The investigators conclude that ambient air pollution is responsible for 8.8 million excess deaths per year globally, with an average loss of life expectancy (LLE) of 2.9 years.

The new study has several features that build on the previous analyses. First, a ‘other non-communicable disease’ category has been added, which incorporates related conditions such as high blood pressure and diabetes, both of which are exacerbated by air pollution.11,12 These intermediate-risk factors play an important role in the burden of non-communicable disease and lie between exposure to air pollution and disease. Second, a detailed breakdown of the data is provided by region, with mortality from air pollution dominated by East and South Asia. The (health) risk estimates from the GEMM primarily originate from high-income nations and the assumption made is that these exposure–outcome risk estimates can be applied to low- and middle-income nations. Nonetheless, given the paucity of data from low-income nations, such an assumption is justifiable.13 Third, mortality is reported alongside estimates of years of life lost and LLE. Many studies evaluating the burden of air pollution have done so using exposure-related deaths as raw counts. This may give a distorting picture of the mortality burden, because it does not consider how long someone who died from exposure-related mortality might otherwise have been expected to live in a counterfactual scenario. Years life lost and loss of life expectancy is an useful metric to provide nuance to mortality estimates, as together a broader picture can be garnered between nations which have similar high levels of air pollution but differences in survival. For example, attributable mortality rate in South Asia is lower than Europe, whereas LLE is 50% greater in South Asia due to less advanced healthcare, higher child mortality, and an overall younger (and more economically active) population structure. Lastly, the study makes broad estimates of the burden arising from different sources of pollution by distinguishing natural and anthropological sources, in particular those from combustion of fossil fuels. This distinction provides an additional perspective as to how mortality metrics may vary between regions. For example, over the last few decades, the megacities of both China and India have vied in their rankings of extreme pollution, however, the current analysis highlights the greater mortality attributed to pollution from residential biofuel in India, whereas fossil-fuel combustion (e.g. small-scale coal combustion) exerts a greater influence on mortality in China.

The study investigators acknowledge a key limitation of the current study (and indeed most other air pollution epidemiological investigations) is that PM is treated as a single entity. Different sources of pollution produce PM with markedly different composition and, accordingly, different toxicity profiles. The authors should be praised for dissecting out the burden derived from fossil fuels compared to total PM2.5. However, at present, this is a simplistic categorization that is not derived from differences in toxicity per se. There is now a large body of research demonstrating that traffic, in particular, is a key pollutant in terms of health effects.5 For example, the particulates in diesel exhaust contain high proportions of nanoparticles that have the capacity to cause widespread cardiovascular dysfunction. The small size of these particles allows them to carry disproportionately large amounts of chemical species on their surface (compared to an equivalent mass of larger particles) and have the potential to cross into the blood to reach extrapulmonary locations, such as the heart, brain, and kidney.14 The ability to model the mortality specifically associated with traffic-derived air pollutants would be a valuable addition to burden estimates, especially together with differentiation of mortality from a broad range of diseases.

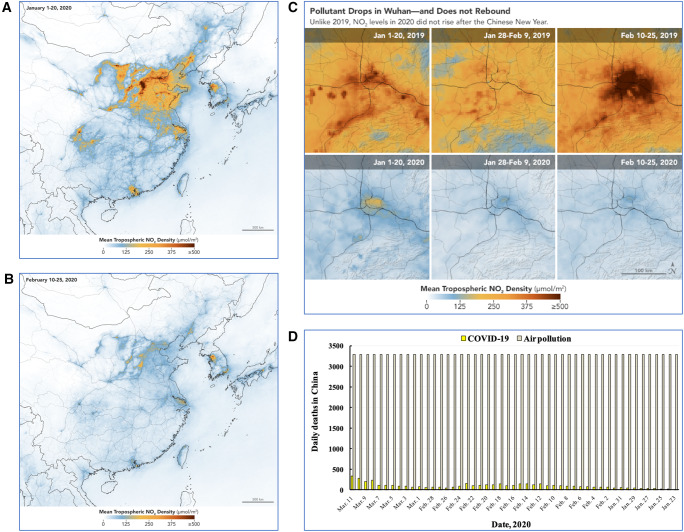

The contribution by Lelieveld et al. is invaluable and is a reminder that we cannot be complacent about air pollution. Indeed, one statistic in particular stands out: the loss of life expectancy from air pollution could be more than halved (reduced by 1.7 years) if all anthropogenic sources of pollution could be removed from our environments. Many countries are moving towards reducing combustion emissions from industry, domestic sources, and traffic. Widespread electrification of vehicles is now underway and there is a growing appreciation of the environmental and health benefits of active travel. The slow pace of political and behavioural change is still a concern: rightly or wrongly, we do not see the same sense of urgency for air pollution that we do for infectious pandemics. Nonetheless, as world order resumes following the COVID-19 pandemic, it will be interesting to explore the influence the pandemic has had on air pollution. The restrictions on human activity have had marked effects on air pollution in cities, with a 25–50% reduction in nitrogen dioxide and PM2.5 in major cities around the world. Early estimates of the mortality linked to COVID-19 vs. air pollution are emerging (e.g. Figure 115) and we eagerly await further assessments of the potential health consequences of this inadvertent pollution intervention. Maybe some uncomfortable positives can be drawn from the consequences of the pandemic. At the very least, such observations demonstrate the clear link between human activity and air pollutants and, hopefully to, they will strengthen the resolve to tackle the blight of air pollution on our lives.

Figure 1.

Reductions in air pollution due to the public quarantines in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Levels of tropospheric nitrogen dioxide in (A) China before the lockdown, (B) China after the lockdown, and (C) Wuhan province in China. (D) Estimates of daily mortality from COVID-19 and air pollution. Images (Sentinel-5p, NASA Earth Observatory and The Verge 2020) and data reproduced with permission from Ref.15

Funding

M.R.M. is supported by the British Heart Foundation (CH/09/002). A.S.V.S. is supported by a British Heart Foundation Intermediate Clinical Research Fellowship (FS/19/17/34172). D.E.N. is supported by the British Heart Foundation (CH/09/002, RG/10/9/28286, RE/18/5/34216) and is the recipient of a Wellcome Trust Senior Investigator Award (WT103782AIA).

Conflict of interest: the authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

The opinions expressed in this article are not necessarily those of the Editors of Cardiovascular Research or of the European Society of Cardiology.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Situation Report—77. 2020. (https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200406-sitrep-77-covid-19.pdf?sfvrsn=21d1e632_2 9 April 2020, date last accessed).

- 2. Miller MR, Raftis JB, Langrish JP, McLean SG, Samutrtai P, Connell SP, Wilson S, Vesey AT, Fokkens PHB, Boere AJF, Krystek P, Campbell CJ, Hadoke PWF, Donaldson K, Cassee FR, Newby DE, Duffin R, Mills NL.. Inhaled nanoparticles accumulate at sites of vascular disease. ACS Nano 2017;11:4542–4552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Miller MR. Oxidative stress and the cardiovascular effects of air pollution. Free Radic Biol Med 2020. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2020.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Schraufnagel DE, Balmes JR, Cowl CT, De Matteis S, Jung SH, Mortimer K, Perez-Padilla R, Rice MB, Riojas-Rodriguez H, Sood A, Thurston GD, To T, Vanker A, Wuebbles DJ.. Air pollution and noncommunicable diseases: a review by the forum of international respiratory societies’ environmental committee, part 1: the damaging effects of air pollution. Chest 2019;155:409–416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Miller MR, Newby DE.. Air pollution and cardiovascular disease: car sick. Cardiovasc Res 2020;116:279–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Burnett R, Chen H, Szyszkowicz M, Fann N, Hubbell B, Pope CA 3rd, Apte JS, Brauer M, Cohen A, Weichenthal S, Coggins J, Di Q, Brunekreef B, Frostad J, Lim SS, Kan H, Walker KD, Thurston GD, Hayes RB, Lim CC, Turner MC, Jerrett M, Krewski D, Gapstur SM, Diver WR, Ostro B, Goldberg D, Crouse DL, Martin RV, Peters P, Pinault L, Tjepkema M, van Donkelaar A, Villeneuve PJ, Miller AB, Yin P, Zhou M, Wang L, Janssen NAH, Marra M, Atkinson RW, Tsang H, Quoc Thach T, Cannon JB, Allen RT, Hart JE, Laden F, Cesaroni G, Forastiere F, Weinmayr G, Jaensch A, Nagel G, Concin H, Spadaro JV.. Global estimates of mortality associated with long-term exposure to outdoor fine particulate matter. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2018;115:9592–9597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cohen AJ, Brauer M, Burnett R, Anderson HR, Frostad J, Estep K, Balakrishnan K, Brunekreef B, Dandona L, Dandona R, Feigin V, Freedman G, Hubbell B, Jobling A, Kan H, Knibbs L, Liu Y, Martin R, Morawska L, Pope CA, 3rd Shin H, Straif K, Shaddick G, Thomas M, van Dingenen R, van Donkelaar A, Vos T, Murray CJL, Forouzanfar MH.. Estimates and 25-year trends of the global burden of disease attributable to ambient air pollution: an analysis of data from the Global Burden of Diseases Study 2015. Lancet 2017;389:1907–1918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lelieveld J, Klingmuller K, Pozzer A, Poschl U, Fnais M, Daiber A, Munzel T.. Cardiovascular disease burden from ambient air pollution in Europe reassessed using novel hazard ratio functions. Eur Heart J 2019;40:1590–1596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization. 7 million premature deaths annually linked to air pollution. 2014. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2014/air-pollution/en/(9 April 2020, date last accessed).

- 10. Lelieveld J, Pozzer A, Poschl U, Fnais M, Haines A, Munzel T.. Loss of life expectancy from air pollution compared to other risk factors: a worldwide perspective. Cardiovasc Res 2020;116:1910–1917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yang BY, Qian Z, Howard SW, Vaughn MG, Fan SJ, Liu KK, Dong GH.. Global association between ambient air pollution and blood pressure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ Pollut 2018;235:576–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Liu F, Chen G, Huo W, Wang C, Liu S, Li N, Mao S, Hou Y, Lu Y, Xiang H.. Associations between long-term exposure to ambient air pollution and risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ Pollut 2019;252:1235–1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lee KK, Miller MR, Shah A.. Air pollution and stroke. J Stroke 2018;20:2–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Raftis JB, Miller MR.. Nanoparticle translocation and multi-organ toxicity: a particularly small problem. Nanotoday 2019;26:8–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Isaifan RJ. The dramatic impact of Coronavirus outbreak on air quality: has it saved as much as it has killed so far? Global J Environ Sci Manag 2020;6:275–288. [Google Scholar]