Abstract

Neurokinin B (NKB) is critical for fertility in humans and stimulates GnRH/LH secretion in several species, including sheep. There is increasing evidence that NKB actions in the retrochiasmatic area (RCh) contribute to the induction of the preovulatory LH surge in sheep. In this study, we determined if there are sex differences in the response to RCh administration of senktide, an agonist to the NKB receptor (NK3R), and in NKB and NK3R expression in the RCh of sheep. To normalize endogenous hormone concentrations, animals were gonadectomized and given implants to mimic the pattern of ovarian steroids seen in the estrous cycle. In females, senktide microimplants in the RCh produced an increase in LH concentrations that lasted for at least 8 hrs after the start of treatment, while a much shorter increment (~2 hrs) was seen in males. We next collected tissue from gonadectomized lambs 18 hrs after insertion of estradiol implants that produce an LH surge in female, but not male, sheep for immunohistochemical analysis of NKB and NK3R expression. As expected, there were more NKB-containing neurons in the arcuate nucleus of females than males. Interestingly, there was a similar sexual dimorphism in NK3R-containing neurons in the RCh, NKB-containing close contacts onto these RCh NK3R neurons, and overall NKB-positive fibers in this region. These data demonstrate that there are both functional and morphological sex differences in NKB-NK3R signaling in the RCh and raise the possibility that this dimorphism contributes to the sex-dependent ability of estradiol to induce an LH surge in female sheep.

Keywords: GnRH, NK3R, NKB, sexual dimorphism, reproduction, hypothalamus

Article Summary:

This study tested the hypothesis that there is a sexual dimorphism in NKB-NK3R signaling in the retrochiasmatic area (RCh) of sheep. We observed that local administration of a NK3R agonist into the RCh produced a larger increase in LH secretion in female than male sheep and that there is less NK3R expression in and NKB input to the RCh in male than female sheep. These data raise the possibility that these sex differences may contribute to the inability of oestrogen to induce a LH surge in male sheep.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction:

The neuroendocrine pathways that control ovulation in females have been the subject of intense investigation over the last fifty years (1–5). It is now clear that high levels of estradiol (E2) produced by the maturing follicle(s) act to induce a GnRH surge that in turn elicits a corresponding surge of LH that then causes ovulation. However, the molecular and neural mechanisms that mediate the interplay between estrogen and GnRH are still not fully understood. Because GnRH neurons are devoid of estrogen receptor alpha (ERα) (6, 7), the receptor subtype whereby E2 exerts its feedback effects, intermediary neurons must participate in this process.

The role of kisspeptin in controlling GnRH secretion has been extensively examined since kisspeptin signaling was shown to be critical for fertility in humans (8, 9) and mice (8). Importantly, kisspeptin neurons express ERα in numerous species (10), including sheep (11). There is now convincing evidence that a population of kisspeptin neurons in the rostral periventricular area of the third ventricle (RP3V) mediate the positive feedback actions of E2 in female rodents (5, 12). In sheep, it appears that kisspeptin neurons in both the arcuate (ARC) and preoptic area (POA) participate in the positive feedback effects of estrogen (13–15). The ARC population of neurons co-express neurokinin B (NKB) and dynorphin (16) and were thus given the name “KNDy” neurons (17).

Like kisspeptin, mutations in NKB or its cognate receptor, neurokinin receptor-3 (NK3R), preclude pubertal development and lead to hypogonadotropic hypogonadism in humans (18). Most subsequent work has focused on the role of NKB in control of GnRH pulses (19–21), but we have recently obtained strong evidence that NKB actions participate in estrogen-positive feedback in sheep. Specifically, local administration of the NK3R agonist, senktide, to the retrochiasmatic area (RCh) (22, 23) and POA (23), but not the ARC (23), induced a surge-like increase in LH secretion. More importantly, disruption of NKB-NK3R signaling in the RCh reduced the amplitude of the LH surge by approximately 50% (23, 24). Moreover, pharmacological and anatomical data indicate that the NKB-sensitive neurons in the RCh project to KNDy neurons and that kisspeptin release from these KNDy neurons mediates the stimulatory actions of these projections during the LH surge (24, 25).

An important characteristic of the LH surge is that it is sexually dimorphic: it occurs in females, but not in normal males of many species, including rodents (26), sheep (27, 28), and humans (29). This lack of responsiveness to high levels of E2 in males is likely due to exposure to testosterone during critical developmental periods, leading to differentiation of neural systems necessary for the LH surge in rodents (30–32) and sheep (27, 33, 34). Thus, the existence of sexual dimorphism in specific neural systems has implied that they may contribute to the LH surge. For example, there are many more kisspeptin neurons in the RP3V of female than male rodents, due to perinatal exposure to androgens (31, 35). Similarly, adult rams have fewer kisspeptin neurons in both the POA and ARC compared to females (17). However, it is not clear if this sexual dimorphism is due to prenatal exposure that masculinizes the systems responsible for the LH surge because androgen treatment of ovine fetal ewes did not decrease kisspeptin cell numbers (17). This raises the possibility that sex differences in components of the NKB-NK3R signaling system could account, in part, for the inability of estrogen to induce an LH surge in male sheep.

This study was designed to test this possibility by determining: 1) if males are less responsive than females to local administration of senktide into the RCh, 2) if there is a sexual dimorphism in NK3R and/or NKB expression in the POA and/or RCh and 3) if sex-specific differences exist in NKB terminals onto NK3R-immunoreactive (ir) neurons in the RCh. We also examined sex differences in the number of KNDy neurons as a positive control for any anatomical differences observed. To minimize sex differences in endogenous steroid concentrations, all studies were carried out in gonadectomized lambs that were treated with E2 and progesterone implants to produce artificial luteal and/or follicular phases (36, 37). In our first set of experiments, we used wethers (males castrated within a few weeks birth) because they are readily available compared to post-pubertal gonadally-intact male rams. Because LH levels were not completely normalized by steroid treatments in wethers, subsequent work was done in acutely gonadectomized male and female sheep.

Material and Methods

Animals

Blackface ewe-lambs and wethers or gonadally-intact males (Exp. 3) born in February or March were moved from pasture to a quarantine area where they were fed cubed alfalfa hay for approximately 2 weeks. They were then moved indoors to acclimate to housing within the facility for at least one week before surgeries. Once indoors, sheep were allowed free access to water and mineral blocks and were fed cubed alfalfa hay twice daily. Animals were maintained in a light- and temperature-controlled facility with the internal lighting environment adjusted to mimic natural changes in day-length. Experiments were performed during the breeding season (December), when animals were 9 to 10 months of age.

General Methods

Surgeries

Ovariectomies (OVX) and castrations were performed under gas anesthesia using aseptic conditions. For OVX, the ovarian vasculature was ligated, and the ovaries removed via a mid-ventral incision. For castration (Exp. 3), the distal third of the scrotum was removed, the testicular vasculature visualized and ligated, and the testes were then removed. Neurosurgeries (Exp. 1) were performed on wethers and immediately after OVX of females, to implant 18-gauge stainless steel guide tubes into the RCh area under general anesthesia as previously described (38). Bilateral (2.5 mm from midline) guide tubes were lowered to a point just caudal to the optic chiasm and 1.5 mm dorsal to the target site, plugged with obturators, cemented in place, and protected with a plastic cap. Animals were treated pre- and post-operatively as described previously (39). Briefly, dexamethasone, analgesics (carprofen and gabapentin), and antibiotics (ampicillin and gentamicin) were given for neurosurgeries, and carprofen and ampicillin given to castrated and OVX lambs that did not undergo neurosurgeries. All pre- and post-operative drugs were acquired from Patterson Veterinary (Bessemer, AL) except gabapentin, which was compounded locally (McCracken Pharmacy, Waynesburg, PA). Animals were allowed to recover from surgery for at least 1 week before experiments were performed.

Steroid replacement and blood sampling procedures

We used the following well-described (36, 37, 39–41) steroid replacement model in both males and females to mimic patterns of ovarian hormones seen during the ovarian cycle: 1) luteal phase levels of E2 were produced by subcutaneous (sc) insertion of a single 1-cm long SILASTIC implant (inner diameter 0.34 cm, outer diameter 0.46 cm; Dow Corning Corp., Midland, MI, USA) containing E2; 2) follicular phase levels of E2 were approximated with four, 3-cm long SILASTIC E2 implants; and 3) luteal phase progesterone patterns were achieved by inserting 2 Controlled Internal Drug Release (CIDR) devices (Zoetis, Parsippany, NJ) sc and leaving these in place for 10–14 days. Previous studies demonstrated that sc CIDR implants resulted in equivalent progesterone concentrations in gonadectomized male and female sheep (36). Blood samples (3–4 ml) were collected by venipuncture, placed in heparinized tubes and plasma was stored at −20 °C until assayed for LH. All procedures were approved by the West Virginia University Animal Care and Use Committee and were performed in accordance with the National Institutes of Health guidelines for the care and use of research animals.

Animal experiments

Preliminary work:

We first determined the time course of E2 and progesterone negative feedback on LH secretion in wethers. On day 0, one small E2 implant and two CIDRs were inserted sc. Eight days later, blood samples were collected every 12 minutes for 4 hrs (P+E), after which CIDRs were removed and frequent blood samples collected the next day (E). Two days after CIDR removal, two new CIDRs were inserted and this process was repeated twice so that males were exposed to a total of three artificial luteal phases. Mean LH concentrations fell progressively from pretreatment values (24.1 ± 1.3 ng/mL) to the second luteal phase (P+E, 9.5 ± 2.0 ng/mL, E, 11.5 ± 2.0 ng/mL), but no further decline was observed in the third phase (P+E, 8.9 ± 1.2 ng/mL, E, 14.0 ± 1.2 ng/mL). Therefore, pre-treatment with at least two artificial luteal phases was chosen for subsequent studies using wethers.

Exp. 1: Comparison of the effect of senktide microimplants in the RCh on LH release in males and females

This experiment compared the effects of senktide administration within the RCh on LH secretion in young wethers (n = 7) and ewes (n = 6) using senktide treatments and frequent blood collections that were the same as those that previously demonstrated surge-like LH secretion in female adults (22, 23). The most effective treatments in adult females were done early in the follicular phase when progesterone concentrations are low and estradiol levels have not yet begun to rise substantially; therefore, we gave senktide in this experiment at a time in the artificial follicular phase before the estradiol rise was simulated with four 3-cm long estrogen implants. After one (ewes), or two (wethers), artificial luteal phases, CIDRs were removed and, the next day, blood samples were collected from 36 minutes before to 8 hours after bilateral insertion of empty (control)- or senktide-containing microimplants into the RCh. Microimplants consisted of sterile 22-gauge blunt-ended stainless steel hollow tubes that were cut to extend 1.5 mm beyond the 18-gauge guide tubes. The ends of the microimplant tubing were tamped at least 60 times in crystalline senktide (Tocris Bioscience; Ellisville, MO) and the exterior wiped clean with sterile gauze immediately before implantation, leaving the lumen tightly packed with senktide crystals. Senktide-containing or empty microimplants were inserted after three blood samples (36 minutes), left in place for 4 hrs, and then removed and replaced with obturators to occlude guide cannulas. Blood samples were collected every 12-min for the first 4 hrs and 36 min and every 30 min for the last 4 hrs as in previous work (22, 23). At the end of the sampling period, CIDRs were reinserted, and the protocol was repeated two weeks later using a cross-over design so that each animal received both treatments during the study. At the end of the study, all animals were euthanized, and tissue collected for assessment of guide cannula placement.

Exp. 2: Comparison of NK3R and NKB expression between steroid-treated wethers and OVX females

To determine whether differences exist between males and females in NK3R-containing cell populations and/or NKB-containing neurons, young male (n = 6) and female (n = 5) sheep at 9 to 10 months of age received two sequential artificial luteal phases as described above. Females were OVX two weeks before the start of steroid treatment to allow time for mean LH levels to rise to levels similar to those in the wethers. On the eighth day of the second artificial luteal phase, CIDRs were removed and the following day, four 3-cm long implants containing E2 were inserted. Blood was collected every 12 min for one hr just before CIDR removal (P+E) and just before insertion of the E2 implants (E) to assess mean tonic LH secretion. Approximately 18–20 hrs later, animals were euthanized and tissue blocks were obtained as described below. Blood samples were collected every 12 min for 2 hours just before tissue collection. The time of tissue collection was based on previous work using this model that examined sex differences in expression of NKB, NK3R, and kisspeptin (37, 42).

Exp. 3: Comparison of NK3R, NKB, and kisspeptin expression between steroid-treated castrated males and OVX females

Because the differences observed in Exp. 2 might reflect the chronic absence of steroids in wethers, we replicated Exp. 2 a year later using acutely gonadectomized male and female lambs. Male and female lambs were gonadectomized and immediately given a small E2 implant and 2 CIDRs. Eight days later the CIDRs were removed and four long E2 implants inserted 24 hrs later. Blood samples were collected every 2–4 hrs for the 36 hrs after insertion of E2 implants to confirm the sex difference in estrogen positive feedback. The four E2 implants were then removed, 2 new CIDRs inserted and the steroid treatment protocol replicated. Frequent blood samples were collected for 4 hrs just before CIDR removal (P+E), just before insertion of the E2 implants (E), and for 1 hr just before tissue collection 18–20 hrs after insertion of the four long E2 implants to assess LH secretion.

Tissue collection

Tissue was collected for immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis and for histological examination of guide cannula placements as previously described (39). Briefly, animals were treated with heparin (20,000 U) 10 minutes before and at the time of euthanasia, which was accomplished by an intravenous overdose of sodium pentobarbital (8 to 12 mL, Euthasol; Patterson Veterinary, Bessemer, AL). Once respiration stopped and there was no eye-blink reflex, the carotids were cut and the head rapidly removed and perfused via the carotid arteries with 4 L of a solution containing 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (PB) with 0.1% sodium nitrite. Tissue blocks containing the POA and hypothalamus were removed and stored overnight in the paraformaldehyde solution at 4°C. The following day, blocks were transferred to a solution containing 20% sucrose in 0.1M PB and stored at 4°C. A microtome with a freezing stage was used to section blocks in 45-μm increments. For Exp. 1, every fifth section through the RCh was stained with cresyl violet and examined for guide cannula placement. For neuroanatomical experiments, 10 parallel series of sections (450 μm apart) were stored in cryoprotectant (43) at −20°C.

Immunohistochemistry

Tissue from Exp. 2 and 3 was used to assess NK3R- and NKB-immunoreactivity (ir) in the POA and RCh. Dual-label IHC was performed on a complete series of free-floating hemi-sections throughout these areas from each animal. All washes were performed at room temperature under gentle agitation with phosphate buffered saline (PBS). Sections were rinsed 4 times for 5 min between incubations unless noted otherwise. On the first day, tissue sections were rinsed thoroughly 12 times for 15 min each time. After PBS washes, tissue sections were incubated in 1% H2O2 for 10 min, rinsed, and incubated in 4% normal goat serum (NGS, Jackson Immunoresearch, West Groove, PA) in PBS containing 0.4% triton X-100 (NGS-TX) before overnight incubation with rabbit anti-NKB (dilution 1:5,000 in 4% NGS-TX; Phoenix, Catalog #H-046–06, Lot 01297–2, RRID: AB_2716809). On the second day, sections were rinsed and then incubated in biotinylated goat anti-rabbit immunoglobin (1:500 in 4% NGS-TX; Vector BA-1000, Lot ZA0520) for 1 hr, followed by ABC-elite (1:500 in PBS; Vector Laboratory Burlingame, CA) for 1 hr. Sections were rinsed again and incubated for 10 min in biotinylated tyramine (TSA) (dilution 1:250; Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA) in PBS containing 3% H2O2 per 1 mL of solution. After rinsing, sections were incubated in DyLight green 488-conjugated to streptavidin (1:100 in PBS; Fisher Scientific) for 30 minutes, followed by rinses and incubation for 1 hour in 4% NGS-TX. Sections were then incubated overnight with rabbit anti-NK3R (dilution 1:1,000 in 4% NGS-TX; Novus, Catalog #NB300–102, Lot F, RRID: AB_10003270). On the third day, sections were rinsed and then incubated in Alexa555 goat anti‐rabbit (dilution 1:100 in 4% NGS; Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) for 30 min. Sections were rinsed again before being incubated with Neurotrace 640/600 Deep Red Fluorescent Nissl Stain (1:100 in PBS; Life Technologies; Lot N21483) for 20 min. Sections were then rinsed in phosphate buffer (PB), mounted on charged Superfrost slides (Fisher Scientific), cover-slipped using Gelvatol and stored in the dark at 4°C until analysis. For Exp. 2, IHC for NKB was performed on a complete series of sections through the ARC using the procedure described above with the omission of the steps needed for NK3R-ir. For Exp. 3, we used kisspeptin-ir as a marker for KNDy neurons, following the staining protocol for NKB, except using an antibody against kisspeptin (dilution 1:50,000 in 20% NGS-TX; Caraty: AC566, RRID:AB_2296529). The analysis of KNDy cell number in the ARC served as a positive control for any sex difference in the POA or RCh. Because tissue was collected from females and males given the same steroid treatments, the data on kisspeptin expression were also used to determine if the differences in kisspeptin expression previously observed between gonadally-intact male and female sheep (17) were due to differences in endogenous hormones in that study. Based on that analysis we subsequently processed POA sections from Exp. 3 for kisspeptin-ir with a procedure identical to that used with ARC tissue, except with a higher concentration of kisspeptin antibody (dilution 1:25,000 in 20% NGS-TX). Antibodies used to detect NK3R (44), NKB (45), and kisspeptin (16) have been validated and used extensively in sheep; contemporaneous controls included omission of primary antibodies which resulted in complete absence of staining.

Analysis of NK3R-ir cells in the POA and RCh, KNDy cells in the ARC, and kisspeptin cells in the POA

The total number of NK3R-ir cells in the POA and RCh, and the average number of NKB-ir (Exp. 2) or kisspeptin-ir cells/section in the ARC and POA (Exp. 3) were assessed using an upright fluorescent microscope (VS120; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) with a 20x objective. The total number of NK3R-ir cells represents the sum of cell numbers in three representative POA hemi-sections that included, or were just posterior to, the organum vasculosum of the lamina terminalis (37, 44). The area analyzed in the RCh extended in the lateral direction from the medial edge of the optic tract to the fornix, ventrally from the fornix to the base of the brain and approximately 1.4 mm (three hemi-sections) posterior to the optic chiasm (37, 44). KNDy cell numbers were averaged across 3 – 4 hemi-sections containing the middle to caudal ARC per animal (16). All cell counts were made by an observer blinded to treatment groups.

Analysis of NKB-ir fibers and NKB-ir close contacts on NK3R-ir neurons in the RCh

In order to assess NK3R fiber density in the RCh, 4 images were captured across at least two hemi-sections per animal using a Hamamatsu Orca Flash 4.0 monochrome cMOS image sensor on a Nikon A1R confocal microscope (Nikon Instruments Inc., Melville, NY) with a Plan Apochromat VC 20X DIC N2/ 0.8 WD (1 mm) objective. Confocal Z-stacks of optical sections were taken at 1 μm intervals throughout each section and the settings for each laser (488, 561, 640 nm) were identical across all images to allow for comparisons. NIS-Elements software was used for image processing by the ROI statistical tools to measure mean pixel intensity across a Z-stack; each image area measured 512 × 512 pixels. A threshold signal was established and applied to all images before the number of objects was determined by the ROI standard. To examine the number of NKB close-contacts onto NK3R-containing neurons in the RCh, images of 10 neurons were captured across at least 2 sections in the RCh for each animal using the confocal microscope with a 60X Oil/1.4 WD (130 μm) objective. Confocal Z-stacks of optical sections were taken at 1 μm intervals through each neuron. The number of close-contacts onto cell bodies was analyzed using the Nikon software and NIS Elements. A close-contact was defined as a terminal in direct apposition to either a cell body or dendrite, and orthogonal views were used to confirm that contacts were touching the cell in all planes.

Radioimunnoassay

Radioimmunoassays for LH were performed as previously described for ovine samples (46). Briefly, LH concentrations were measured in duplicate using 100 – 200 μL of plasma per sample via a double-antibody radioimmunoassay with reagents supplied by the National Hormone and Peptide Program (Torrance, CA, USA). The sensitivity of the assay averaged 0.06 ng/tube, and the intra- and interassay variability were 13.4% and 14.1%, respectively.

Statistical analyses

In Exp. 1, 4 of 6 females and 4 of 7 males had correct RCh placements of guide cannulas. Animals with misplaced cannulas were omitted from statistical analysis. The initial increase in LH concentration in response to senktide was defined as the first point that was 2 SD (based on assay variability) above the mean of pretreatment values and that was followed by continuously increasing values for at least 1 hr. This time was statistically compared between males and females using Student’s t-test. Comparison of LH concentrations in hourly blocks, starting at the time of treatments, between senktide and blank microimplants was done using two-way ANOVA with repeated measures (effects of time and treatment within sex) with Holm-Sidak post-hoc analysis used for pairwise multiple comparison. Because there was a marked sex difference in LH concentrations before senktide treatments, we calculated the senktide-induced increment in LH concentrations by subtracting the hourly mean LH concentrations for control treatments from mean LH concentrations in the corresponding time block from senktide-treated animals. These deltas were then used to directly compare the response of males and females using two-way ANOVA (main effects of time and sex) with repeated measures. Differences in LH concentrations between males and females were compared at the time of tissue collection (Exp. 2) or at the peak of the LH surge (females) and a comparable time in males (Exp. 3) by independent t-tests. Mean LH concentration during treatment with E+P or E alone in Exps. 2 and 3 were compared by two-way ANOVA (main effects of sex and steroid treatments) with repeated measures.

Data from Exps. 2 and 3 were analyzed separately because the IHC procedures were not done simultaneously. The total number of NK3R cells in the POA and RCh (Exps. 2 and 3), average number of KNDy cells/section in the ARC (Exps. 2 and 3), average number of POA kisspeptin-ir cells/section (Exp. 3), average number of NKB contacts onto NK3R-positive cells in the RCh, and NKB fiber density in the RCh were compared between sexes with independent t-tests. Data are reported as mean ± SEM. Differences were considered significant when P < 0.05.

Results

Are there sex differences in the response to senktide microimplants in the RCh?

Placements of guide cannulas is shown in Fig. 1A; incorrect placements were either rostral or caudal to the RCh. In female sheep with correct placements, senktide administration into the RCh resulted in sustained increases in LH secretion (Fig. 1B-C). In females, LH concentrations in response to senktide were significantly higher than pre-treatment values starting at 39.0 ± 5.7 min after drug administration and remained elevated for the rest of the experiment. Statistical comparison of LH concentrations in control and senktide-treated ewes, indicated that there was no significant effect of time (F = 1.99, P = 0.106, 7 DF) but a significant effect of sex (F = 12.51, P = 0.038, 1 DF) and a significant interaction of sex and time (F = 3.37, P = 0.014, 7 DF). Subsequent pairwise comparisons indicated there was no significant effect of senktide on LH secretion for the 0–1 hr time block (Fig. 2), but that mean LH concentration was significantly increased by senktide treatment in females for the other time blocks. In males, LH concentrations were transiently elevated for approximately 2 hrs, starting 69 ± 10.2 min after senktide administration (Fig. 1C); this time was significantly (P=0.043) later than the increase in females. There was a significant effect of time (F = 3.651, P = 0.010, 7 DF) and an interaction of sex and time (F = 3.81, P = 0.008, 7 DF), but the effect of treatment was not significant (F = 6.22, P = 0.088, 1 DF). Pairwise comparisons indicated that LH concentrations were higher from 2 to 5 hours post-implantation of senktide-containing microimplants than those following insertion of empty implants, but there was no difference before or after this time period (Fig. 2) . Direct comparison of the senktide-induced increments in LH concentrations between sexes indicated a significant main effect of time (F = 6.99, P < 0.001, 7 DF), but not sex (F = 0.008, P = 0.93, 1 DF). However, there was a significant interaction (F = 2.18, P = 0.046, 7 DF) indicating that the response to senktide differed between the sexes.

Figure 1.

Effect of microimplants containing senktide or blank (control) implants in the RCh on LH secretion during an artificial follicular phase in female and male sheep (n = 4/group). (A) Guide cannula placement in the RCh. Grey circles represent placements in males while white circles represent placements in females. (B) Individual LH profiles in a female and male sheep with either blank (closed circles) or senktide-containing (open circles) microimplants in the RCh. Microimplants were inserted at time 0. (C) Mean (± SEM) LH concentrations for control (closed circles) and senktide-treated (open circles) male and female sheep. *First sample that was significantly greater than controls following senktide treatment.

Figure 2.

Comparisons of the effects of control and senktide treatments in the RCh on LH secretion in female and male sheep. Mean (± SEM) LH concentrations in females (A) and males (B) during hourly time intervals after administration of empty (solid bars) or senktide-containing (open bars) microimplants into the RCh. *P< 0.05 vs controls by two way ANOVA with repeated measures.

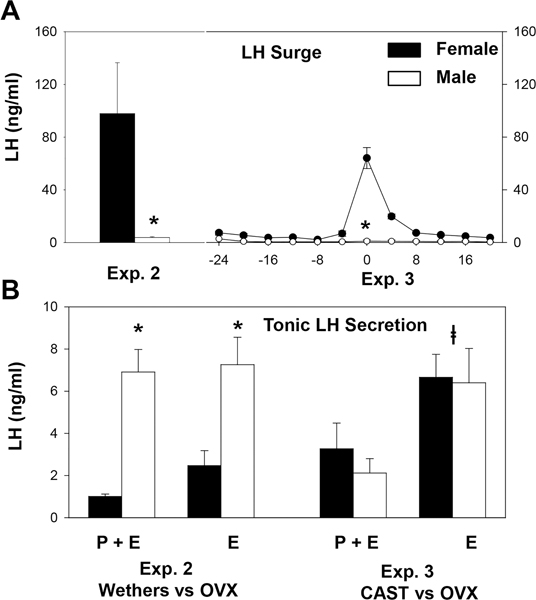

LH concentrations in Experiments 2 and 3

Tonic LH concentrations in the steroid-treated wethers (Exp. 2) were significantly higher than in OVX females during exposure to both luteal phase levels of progesterone and E2 (P+E) and low E2 levels (E) alone (Fig. 3B). In contrast, there was no sex difference in tonic LH concentrations when steroid treatments were started at the time of gonadectomy in Exp. 3. Not surprisingly, there was a clear sex difference in the LH surge in both models (Fig. 3A). In Exp. 2, this was evident in the LH concentrations at the time of tissue collection, and in Exp. 3 it was demonstrated by the time course of LH concentrations during the follicular portion of the first artificial cycle (Fig. 3A, right). LH concentrations at the time of tissue collection in Exp. 3 were also higher in females (16.1 ± 8.6 ng/mL) than males (2.2 ± 0.6 ng/mL), although this difference was not as dramatic as in Exp. 2, possibly because tissue was collected at the beginning of the surge in females.

Figure 3.

(A) LH surge secretion in steroid-treated wethers (Exp. 2), castrated males (Exp. 3), and OVX females (Exps. 2 and 3). Mean (± SEM) LH concentrations at the time of tissue collections for Exp. 2 and during the first artificial follicular phase for Exp. 3 are presented. (B) Comparison of tonic LH secretion in steroid-treated wethers and OVX females (Exp. 2) and gonadectomized males and females (Exp. 3). Bar graphs depict mean (± SEM) LH concentrations during exposure to luteal phase levels of progesterone and E2 (P+E) or low E2 levels (E) alone. *P<0.05 vs values in females by t test for LH surge and two way ANOVA with repeated measures for tonic LH secretion. The latter indicated that there was a significant effect of sex (F = 16.6, P = 0.003, 1 DF), but not of steroid (F= 3.75, P = 0.085, 1 DF), and no interaction (F = 1.39, P = 0.267, 1 DF). P<0.05 vs values during P+E treatment by two way ANOVA with repeated measures (F = 13.7, P = 0.001, 1 DF); there was no effect of sex (F = 0.026, P = 0.88, 1 DF), and no interaction (F = 0.43, P = 0.53, 1 DF).

Are NK3R-containing cell populations in the POA sexually dimorphic?

The morphology of NK3R-ir cell populations in the POA and RCh were the same as described in detail previously for female sheep (44), and there were no obvious differences between females and males. Regardless of sex or neuroanatomical area, NK3R-positive fibers were readily visualized and often appeared as punctate varicosities (Figs. 4,5). The number of NK3R-ir cells in the POA was significantly greater in OVX females than in wethers in Exp. 2, but not in tissue collected from acutely gonadectomized animals in Exp. 3 (Fig. 4E). Although there appeared to be differences in NK3R expression in females between Exps. 2 and 3, these data cannot be directly compared because IHC staining was not done at the same time.

Figure 4.

NK3R expression in the POA of female and male sheep. Panels A and B present low magnification images illustrating NK3R immunoreactivity (red) and NeuroTrace 640/660 fluorescent Nissl staining (blue) in the POA of a female and male sheep, respectively. Higher magnification images of areas identified by the dashed, white boxes are presented in Panels C (female sheep) and D (male sheep). Scale bars: A, B = 200 μm; C, D = 100 μm. (E) Bar graphs compare the total number (± SEM) of NK3R-ir neurons in the POA of wethers (open bars) and OVX females (solid bars) in Exp. 2 and gonadectomized males (open bars) and females (solid bars) in Exp. 3. *P<0.05 vs females value by t-test.

Figure 5.

Sexual dimorphism in expression of NKB and NK3R in the RCh of sheep. Photomicrographs of confocal images (1 μm thick optical section) illustrating NKB (green) and NK3R (red) in the RCh of a female (A) or male (B) sheep. Panels on the right are merged images of two other panels, with additional images of orthogonal projections. White arrowheads indicate NKB-ir close contacts on NK3R-containing cell. Scale bar = 50 μm. (C-D) Bar graphs comparing the total number (± SEM) of NK3R-ir neurons (C) and the number (± SEM) of NKB-ir inputs/NK3R cell (D) in the RCh of female (solid bars) and male sheep (open bars) in Exp. 2 and Exp. 3. P<0.05 vs female values by t-test.

Are NK3R-containing cells and NKB–ir projections to the RCh sexually dimorphic?

In contrast to the POA, there were significantly more RCh NK3R-ir cell bodies in females than males in both Exps. 2 and 3 (Fig 5C). The density of NKB-ir fibers in the RCh was significantly (P < 0.05) greater in OVX females (mean NKB staining: 5,831 ± 1,476 pixels/area) than in wethers (mean NKB staining: 1,480 ± 413 pixels/area) in Exp. 2 (Fig. 5A-B). There was a parallel difference in the number of NKB-ir inputs onto NK3R-containing neurons in the RCh with 4.59 ± 1.16 contacts/cell in females and 0.41 ± 0.32 contacts/cell in males (Fig. 5). Similar sex differences in both NKB-ir fibers and close contacts onto NK3R-ir cells in the RCh (3.67 ± 0.76 contacts/cell in females vs. 1.05 ± 0.19 contacts/cell in males; P = 0.02) were observed in Exp. 3 (Fig. 5D).

Are KNDy cells in the ARC and kisspeptin cells in the POA sexually dimorphic?

The average number of NKB neurons in the ARC was greater in steroid-treated OVX females (60.9 ± 4.2 cells) than in wethers given similar steroid treatments (24.3 ± 3.6 cells) which is in agreement with what was previously described in adults (17, 47, 48) and prenatal testosterone-treated females (17, 48). A similar sexual dimorphism in the number of kisspeptin-ir cell bodies in both the ARC and POA was evident in tissue from acutely gonadectomized steroid-treated animals (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Sexual dimorphism in kisspeptin expression in the ARC and POA of steroid-treated gonadectomized sheep. Photomicrographs illustrating kisspeptin immunoreactivity (green, panels A-B; red, panels C-D) in the ARC (A,B) and POA (C,D) of female (A,C) and male (B,D) sheep. ARC sections were also stained with NeuroTrace 640/660 fluorescent Nissl (blue). Scale bars: A,B = 100 μm; C,D = 200 μm. (E) The mean (± SEM) number of kisspeptin neurons/section in the ARC and POA of female (solid bars) and male (open bars) sheep. P < 0.05* vs female by t-test.

Discussion

This report provides evidence for differences within the RCh that may contribute to the sexual dimorphism of the estrogen-induced LH surge in sheep. Several studies have demonstrated the importance of NKB-NK3R signaling in the RCh (22–24) and the potential for this system to play a role in surge-like LH release by acting via KNDy neurons in the ARC of females (24, 25), but this system has not been examined in males. In the current study, we showed that senktide administration in the RCh resulted in prolonged, surge-like LH release in female, but not male, sheep. Moreover, we demonstrated that the number of NK3R-containing neurons in the RCh and the number of NKB inputs per NK3R cell in the RCh were greater for females than males when both were exposed to levels of E2 sufficient for surge generation in females. These results point to the RCh as one site of functional and morphological sex differences in NKB-NK3R signaling.

Although both males and females responded to RCh senktide administration, there were significant differences in the patterns of LH release. In agreement with previous findings (22, 23), LH release following administration of senktide in the RCh was elevated and prolonged in females. This pattern of LH secretion is more typical of an LH surge, which lasts approximately 12 hrs in sheep (49), than episodic LH secretion. In contrast, while increased LH release was evident in males, this elevation was transient, lasting only about 2 hours. In addition to prolonged LH release, the onset of the LH response to senktide occurred sooner in females compared to males. Direct comparison of the two sexes is complicated by the fact that baseline LH concentrations in wethers were much higher than females, but eliminating this statistical confounding factor by examining the increment in LH concentrations produced by senktide demonstrated a significant sex difference. However, this does not preclude the possibility that the apparent sex differences in response to senktide could simply reflect the higher LH levels in males because this agonist can have different effects when LH concentrations are low than when they are high (50). Nevertheless, these results are consistent with the possibility that sex differences in the responsiveness of NK3R-ir neurons in the RCh may contribute to the sexual dimorphism of the LH surge in sheep. They are also the first data implicating NKB-NK3R signaling in the control of LH secretion in rams, although there is evidence for this in other species (50), including humans (18). Although this system is not involved in estrogen positive feedback in rams, it could play a role in the mechanisms by which pheromones (51) or increased nutrition (52) stimulate LH release.

We observed that the total number of NK3R-containing cells in the POA was significantly lower in males than females when tissue from wethers and acutely OVX females was compared, but not when both males and females had been acutely gonadectomized. Thus, the former may reflect a chronic lack of exposure of the POA to androgens in wethers that could not be overcome with relatively short-term steroid treatments. Since, as expected, acutely castrated males failed to respond to the positive feedback actions of E2, the results are not consistent with the hypothesis that sexual dimorphism in NKB-NK3R signaling in the POA plays a role in the inability of males to respond to estrogen positive feedback. In contrast, males had lower expression of NK3R in the RCh than females in both Exp. 2 and Exp. 3, indicating that this sex difference was not affected by the prolonged absence of testosterone in the wethers. This contrasts to what is found in prenatal testosterone-treated females (37), in which no effect of testosterone treatment on the number of NK3R-containing cells was found in the RCh. These apparently contradictory results are not due to differences in hormonal milieu because tissue was collected during an “artificial follicular phase” in both studies. Instead they are most likely explained by differences in animal models because females born to testosterone-treated mothers still exhibit some aspects of female reproductive function, including a blunted LH surge, for at least two years after birth (33, 53). Thus, prenatally testosterone-treated females may represent an intermediate neuroanatomical state between normal males and females. This possibility is consistent with the report that prenatal testosterone treatment failed to reduce the number of kisspeptin-ir cells in the ARC to levels comparable to that seen in normal male brains (17).

The observations that sex differences in NK3R expression occur in the RCh, but not the POA, are consistent with pharmacological (23) and lesion (24) data that specifically implicate the former in estrogen positive feedback in ewes. These data, and other recent work in the ewe (13–15, 54, 55), have led to a more detailed model for the hypothalamic systems responsible for the GnRH surge in this species that is based on the conceptual model (56) that estrogen positive feedback occurs in three stages: activation, transmission, and secretion of GnRH and LH. This model (Fig. 7) proposes that high concentrations of E2 act at neurons containing somatostatin (SST) and neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS) in the ventromedial nucleus (VMN) (54, 55). These neurons quickly stimulate KNDy neurons so that both populations are responsible for activation of this system (13, 54). This is followed by the transmission phase during which the RCh NKB-responsive neurons play an important role (24) possibly by increasing kisspeptin expression in KNDy neurons. Finally, SST/nNOS, KNDy, and POA kisspeptin neurons act in concert to drive GnRH release during the secretory phase (14, 15, 54). Although this model is speculative it provides a useful framework for other neural elements that may be sexually dimorphic and points to key gaps in our understanding of this system.

Figure 7.

Model for the hypothalamic neural circuitry mediating estrogen positive feedback in sheep. The GnRH surge is initiated by E2 actions on VMN neurons containing SST andn NOS (orange), which immediately stimulate KNDy neurons (green/purple). This activation stage is then followed by a transmission phase (elevated E2 no longer needed), which involves input from RCh NK3R-containing neurons (grey) to KNDy cells. During the final secretory phase SST/nNOS and KNDy neurons are again activated and stimulate POA kisspeptin neurons (green) so that all three drive GnRH neurons (blue) during the GnRH/LH surge. The circuitry connecting neurons directly stimulated by E2 to those involved in the transmission phase (dashed lines) is not known, but presumably involves NKB cell bodies (purple) that have not been identified.

One of the elements that has both of these characteristics is the NKB input to the RCh. In this study, there were dramatic sex differences in the extent of NKB-ir fibers and NKB-containing inputs onto NK3R-ir cells in the RCh, both of which were approximately four times greater in females than in males in Exp. 2 and Exp. 3. This confirms and extends an earlier report of NKB-containing fibers in the RCh of female sheep (45), but the origin of these fibers is unknown. In sheep, nearly all hypothalamic NKB-ir cell bodies are located in the ARC (45, 48), and the vast majority of these neurons also contain kisspeptin (16). However, these KNDy neurons do not project to the RCh because few, if any, kisspeptin-ir fibers are seen in this region (10). There is evidence that some cells in the ARC project to the RCh, but these cells did not colocalize with kisspeptin (25). Thus, the source of the NKB inputs seen in the RCh could be the small population of NKB-ir neurons in the ARC that do not co-express kisspeptin (16), other NKB-producing cells in the hypothalamus that cannot be detected by IHC, or NKB-ir neurons in other areas of the brain. Further work characterizing NKB expression in the ovine brain, including the use of other approaches such as in situ hybridization are needed to distinguish between these possibilities.

There is strong evidence supporting key roles for both the VMN SST/nNOS and kisspeptin neurons in the ARC and POA in the mechanisms producing the GnRH surge in ewes, and some evidence suggesting that they may also be sexually dimorphic. There are no reports of sex differences in the number of VMN SST/nNOS neurons, but the percentage of VMN neurons containing Fos during the activation phase of estrogen positive feedback is higher in control females than in females treated prenatally with testosterone or males, and some of these contain SST (55). There are no reports of sex differences in activation of kisspeptin neurons, but there are fewer kisspeptin neurons in both the ARC and POA of gonadally-intact male than female sheep (17). Because this difference in expression was not produced by prenatal androgen treatment of females (17), the sex differences in gonadally-intact sheep might be due to differences in endogenous hormones between the sexes. However, since we observed a very similar sex difference when tissue was collected from gonadectomized males and females given the same steroid treatments, it seems most likely that the sexual dimorphism in kisspeptin expression in both the POA and ARC reflects earlier exposure to testicular hormones. These results confirm and extend previous evidence that kisspeptin-ir cell numbers are greater in OVX females than in wethers (47). The simplest explanation for the inability of prenatal androgen treatment of females to decrease kisspeptin cell numbers in earlier work is that the window for this organizational action of testosterone is longer than the prenatal treatment used in these studies. Perhaps the latter extends into the neonatal period during which steroid exposure is needed to fully masculinize the LH surge system in sheep (40).

The decreased NKB/NK3R signaling found in males in this study may underlie the sexual dimorphism in both the response to senktide and the failure of males to produce GnRH/LH surges. The decreased number of NK3R-containing neurons in the RCh of males provides a simple explanation for the attenuated LH response to local administration of senktide in this area. However, the ability of senktide to increase LH secretion in males indicates that a difference in NK3R expression cannot account, by itself, for the lack of an estrogen-induced LH surge. Thus, one can infer that the decrease in NKB input to this region in males likely contributes to the sexual dimorphism in estrogen positive feedback in sheep. These findings also support the hypothesis that the population of NK3R-containing cells in the RCh is necessary for full expression of the LH surge in females (23, 24). These cells are thought to increase GnRH/LH secretion during a surge by stimulating kisspeptin synthesis in KNDy cells in the ARC prior to the surge (24, 25), with KNDy neurons then activating POA kisspeptin neurons during GnRH release (Fig. 7). Thus, the lower number of kisspeptin cells in the ARC and POA of males could also contribute to the sexual dimorphism seen in the inability of males to generate an LH surge. It should be noted, however, that other systems contributing to the LH surge in sheep (57) must also be inactive in males because disruption of the RCh NKB-NK3R-KNDy circuitry does not completely block the LH surge in females (24, 58). One obvious possibility is the neural circuitry connecting the activation components of this system (i.e., SST/nNOS and KNDy neurons) to the NKB cell bodies that project to the RCh, but test of this possibility awaits the identification of these NKB cells.

In summary, we report morphological and functional evidence of sexual dimorphism in NKB-NK3R signaling in the ovine RCh. Senktide administration in the RCh resulted in prolonged, surge-like LH release in female, but not male, sheep. This finding is associated with fewer NK3R-positive cells and NKB contacts onto NK3R-containing cells in the RCh, and fewer KNDy cells in the ARC of males. Therefore, we propose that variations in NKB inputs to the RCh, the response to NKB in the RCh, and in the ability of KNDy neurons to respond to a stimulus from the RCh all contribute to the sex-dependent expression of the GnRH/LH surge in sheep.

Acknowledgements

We thank Miroslav Valent, Gail Sager, and John Connors for technical assistance with radioimmunoassay and animal surgeries. We also thank Drs. Margaret Minch and Jennifer Fridley for veterinary care, Heather Bungard for care of the sheep, and Dr. Al Parlow and the National Hormone and Peptide program for reagents used to measure LH.

Image capture and image analysis were performed in the West Virginia University (WVU) Microscope Imaging Facility, which has been supported by the NIH U54 GM104942. We thank Dr. Amanda Ammer for assistance in image analysis and processing.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grants R01-HD039916, R01-HD082135 to R.L.G. and M.N.L., and P20GM103434 to the West Virginia IDeA Network for Biomedical Research Excellence.

Grant support: NIH R01- HD039916, R01-HD082135, P20-GM103434

Footnotes

Disclosure statement: The authors have nothing to disclose

References

- 1.Goodman RL. Neuroendocrine control of gonadotropin secretion: Comparative Aspects In: Plant TM, Zeleznik AJ, editors. Knobil and Neill’s Physiology of Reproduction, Fourth Edition Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2015. p. 1537–68. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clarke IJ. The preovulatory LH surge A case of a neuroendocrine switch. Trends in endocrinology and metabolism: TEM. 1995. September;6(7):241–7. PubMed PMID: 18406707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levine JE. New concepts of the neuroendocrine regulation of gonadotropin surges in rats. Biology of reproduction. 1997. February;56(2):293–302. PubMed PMID: 9116124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Plant TM. A comparison of the neuroendocrine mechanisms underlying the initiation of the preovulatory LH surge in the human, Old World monkey and rodent. Frontiers in neuroendocrinology. 2012. April;33(2):160–8. PubMed PMID: 22410547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khan AR, Kauffman AS. The role of kisspeptin and RFamide-related peptide-3 neurones in the circadian-timed preovulatory luteinising hormone surge. Journal of neuroendocrinology. 2012. January;24(1):131–43. PubMed PMID: 21592236. Pubmed Central PMCID: 3384704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lehman MN, Karsch FJ. Do gonadotropin-releasing hormone, tyrosine hydroxylase-, and beta-endorphin-immunoreactive neurons contain estrogen receptors? A double-label immunocytochemical study in the Suffolk ewe. Endocrinology. 1993. August;133(2):887–95. PubMed PMID: 8102098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Herbison AE. Physiology of the adult gonadotropin-releasing hormone neuronal network In: Plant TM, Zeleznik AJ, editors. Knobil and Neill’s Physiology of Reproduction, Fourth Edition 1 Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2015. p. 399–467. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seminara SB, Messager S, Chatzidaki EE, Thresher RR, Acierno JS Jr., Shagoury JK, et al. The GPR54 gene as a regulator of puberty. The New England journal of medicine. 2003. October 23;349(17):1614–27. PubMed PMID: 14573733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Roux N, Genin E, Carel JC, Matsuda F, Chaussain JL, Milgrom E. Hypogonadotropic hypogonadism due to loss of function of the KiSS1-derived peptide receptor GPR54. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003. September 16;100(19):10972–6. PubMed PMID: 12944565. Pubmed Central PMCID: 196911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lehman MN, Hileman SM, Goodman RL. Neuroanatomy of the kisspeptin signaling system in mammals: comparative and developmental aspects. Advances in experimental medicine and biology. 2013;784:27–62. PubMed PMID: 23550001. Pubmed Central PMCID: 4059209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Franceschini I, Lomet D, Cateau M, Delsol G, Tillet Y, Caraty A. Kisspeptin immunoreactive cells of the ovine preoptic area and arcuate nucleus co-express estrogen receptor alpha. Neuroscience letters. 2006. July 3;401(3):225–30. PubMed PMID: 16621281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Herbison AE. Estrogen positive feedback to gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) neurons in the rodent: the case for the rostral periventricular area of the third ventricle (RP3V). Brain research reviews. 2008. March;57(2):277–87. PubMed PMID: 17604108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith JT, Li Q, Pereira A, Clarke IJ. Kisspeptin neurons in the ovine arcuate nucleus and preoptic area are involved in the preovulatory luteinizing hormone surge. Endocrinology. 2009. December;150(12):5530–8. PubMed PMID: 19819940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoffman GE, Le WW, Franceschini I, Caraty A, Advis JP. Expression of fos and in vivo median eminence release of LHRH identifies an active role for preoptic area kisspeptin neurons in synchronized surges of LH and LHRH in the ewe. Endocrinology. 2011. January;152(1):214–22. PubMed PMID: 21047947. Pubmed Central PMCID: 3219045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Merkley CM, Porter KL, Coolen LM, Hileman SM, Billings HJ, Drews S, et al. KNDy (kisspeptin/neurokinin B/dynorphin) neurons are activated during both pulsatile and surge secretion of LH in the ewe. Endocrinology. 2012. November;153(11):5406–14. PubMed PMID: 22989631. Pubmed Central PMCID: 3473209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goodman RL, Lehman MN, Smith JT, Coolen LM, de Oliveira CV, Jafarzadehshirazi MR, et al. Kisspeptin neurons in the arcuate nucleus of the ewe express both dynorphin A and neurokinin B. Endocrinology. 2007. December;148(12):5752–60. PubMed PMID: 17823266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheng G, Coolen LM, Padmanabhan V, Goodman RL, Lehman MN. The kisspeptin/neurokinin B/dynorphin (KNDy) cell population of the arcuate nucleus: sex differences and effects of prenatal testosterone in sheep. Endocrinology. 2010. January;151(1):301–11. PubMed PMID: 19880810. Pubmed Central PMCID: 2803147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Topaloglu AK, Reimann F, Guclu M, Yalin AS, Kotan LD, Porter KM, et al. TAC3 and TACR3 mutations in familial hypogonadotropic hypogonadism reveal a key role for Neurokinin B in the central control of reproduction. Nature genetics. 2009. March;41(3):354–8. PubMed PMID: 19079066. Pubmed Central PMCID: 4312696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Navarro VM, Gottsch ML, Chavkin C, Okamura H, Clifton DK, Steiner RA. Regulation of gonadotropin-releasing hormone secretion by kisspeptin/dynorphin/neurokinin B neurons in the arcuate nucleus of the mouse. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2009. September 23;29(38):11859–66. PubMed PMID: 19776272. Pubmed Central PMCID: 2793332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wakabayashi Y, Nakada T, Murata K, Ohkura S, Mogi K, Navarro VM, et al. Neurokinin B and dynorphin A in kisspeptin neurons of the arcuate nucleus participate in generation of periodic oscillation of neural activity driving pulsatile gonadotropin-releasing hormone secretion in the goat. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2010. February 24;30(8):3124–32. PubMed PMID: 20181609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goodman RL, Hileman SM, Nestor CC, Porter KL, Connors JM, Hardy SL, et al. Kisspeptin, neurokinin B, and dynorphin act in the arcuate nucleus to control activity of the GnRH pulse generator in ewes. Endocrinology. 2013. November;154(11):4259–69. PubMed PMID: 23959940. Pubmed Central PMCID: 3800763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Billings HJ, Connors JM, Altman SN, Hileman SM, Holaskova I, Lehman MN, et al. Neurokinin B acts via the neurokinin-3 receptor in the retrochiasmatic area to stimulate luteinizing hormone secretion in sheep. Endocrinology. 2010. August;151(8):3836–46. PubMed PMID: 20519368. Pubmed Central PMCID: 2940514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Porter KL, Hileman SM, Hardy SL, Nestor CC, Lehman MN, Goodman RL. Neurokinin-3 receptor activation in the retrochiasmatic area is essential for the full pre-ovulatory luteinising hormone surge in ewes. Journal of neuroendocrinology. 2014. November;26(11):776–84. PubMed PMID: 25040132. Pubmed Central PMCID: 4201879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goodman RL, He W, Lopez JA, Bedenbaugh MN, McCosh RB, Bowdridge EC, et al. Evidence That the LH Surge in Ewes Involves Both Neurokinin B-Dependent and -Independent Actions of Kisspeptin. Endocrinology. 2019. December 1;160(12):2990–3000. PubMed PMID: 31599937. Pubmed Central PMCID: 6857763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grachev P, Porter KL, Coolen LM, McCosh RB, Connors JM, Hileman SM, et al. Surge-Like Luteinising Hormone Secretion Induced by Retrochiasmatic Area NK3R Activation is Mediated Primarily by Arcuate Kisspeptin Neurones in the Ewe. Journal of neuroendocrinology. 2016. June;28(6). PubMed PMID: 27059932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pfieffer CA. Sexual differentiation of the hypophyses and their determination by the gonads. Am J Anat. 1936;58:195–225. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Herbosa CG, Dahl GE, Evans NP, Pelt J, Wood RI, Foster DL. Sexual differentiation of the surge mode of gonadotropin secretion: prenatal androgens abolish the gonadotropin-releasing hormone surge in the sheep. Journal of neuroendocrinology. 1996. August;8(8):627–33. PubMed PMID: 8866251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stormshak F, Estill CT, Resko JA, Roselli CE. Changes in LH secretion in response to an estradiol challenge in male- and female-oriented rams and in ewes. Reproduction. 2008. May;135(5):733–8. PubMed PMID: 18304985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Van Look PF, Hunter WM, Corker CS, Baird DT. Failure of positive feedback in normal men and subjects with testicular feminization. Clinical endocrinology. 1977. November;7(5):353–66. PubMed PMID: 589801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gorski RA. The neuroendocrinology of reproduction: an overview. Biology of reproduction. 1979. February;20(1):111–27. PubMed PMID: 378271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tsukamura H, Homma T, Tomikawa J, Uenoyama Y, Maeda K. Sexual differentiation of kisspeptin neurons responsible for sex difference in gonadotropin release in rats. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2010. July;1200:95–103. PubMed PMID: 20633137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Semaan SJ, Kauffman AS. Sexual differentiation and development of forebrain reproductive circuits. Current opinion in neurobiology. 2010. August;20(4):424–31. PubMed PMID: 20471241. Pubmed Central PMCID: 2937059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wood RI, Foster DL. Sexual differentiation of reproductive neuroendocrine function in sheep. Reviews of reproduction. 1998. May;3(2):130–40. PubMed PMID: 9685192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Foster DL, Padmanabhan V, Wood RI, Robinson JE. Sexual differentiation of the neuroendocrine control of gonadotrophin secretion: concepts derived from sheep models. Reproduction. 2002;59:83–99. PubMed PMID: 12698975. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kauffman AS, Gottsch ML, Roa J, Byquist AC, Crown A, Clifton DK, et al. Sexual differentiation of Kiss1 gene expression in the brain of the rat. Endocrinology. 2007. April;148(4):1774–83. PubMed PMID: 17204549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Robinson JE, Forsdike RA, Taylor JA. In utero exposure of female lambs to testosterone reduces the sensitivity of the gonadotropin-releasing hormone neuronal network to inhibition by progesterone. Endocrinology. 1999. December;140(12):5797–805. PubMed PMID: 10579346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ahn T, Fergani C, Coolen LM, Padmanabhan V, Lehman MN. Prenatal testosterone excess decreases neurokinin 3 receptor immunoreactivity within the arcuate nucleus KNDy cell population. Journal of neuroendocrinology. 2015. February;27(2):100–10. PubMed PMID: 25496429. Pubmed Central PMCID: 4412353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Anderson GM, Connors JM, Hardy SL, Valent M, Goodman RL. Oestradiol microimplants in the ventromedial preoptic area inhibit secretion of luteinizing hormone via dopamine neurones in anoestrous ewes. Journal of neuroendocrinology. 2001. December;13(12):1051–8. PubMed PMID: 11722701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McCosh RB, Szeligo BM, Bedenbaugh MN, Lopez JA, Hardy SL, Hileman SM, et al. Evidence That Endogenous Somatostatin Inhibits Episodic, but Not Surge, Secretion of LH in Female Sheep. Endocrinology. 2017. June 1;158(6):1827–37. PubMed PMID: 28379327. Pubmed Central PMCID: 5460938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jackson LM, Mytinger A, Roberts EK, Lee TM, Foster DL, Padmanabhan V, et al. Developmental programming: postnatal steroids complete prenatal steroid actions to differentially organize the GnRH surge mechanism and reproductive behavior in female sheep. Endocrinology. 2013. April;154(4):1612–23. PubMed PMID: 23417422. Pubmed Central PMCID: 3602628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Skinner DC, Harris TG, Evans NP. Duration and amplitude of the luteal phase progesterone increment times the estradiol-induced luteinizing hormone surge in ewes. Biology of reproduction. 2000. October;63(4):1135–42. PubMed PMID: 10993837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cernea M, Padmanabhan V, Goodman RL, Coolen LM, Lehman MN. Prenatal Testosterone Treatment Leads to Changes in the Morphology of KNDy Neurons, Their Inputs, and Projections to GnRH Cells in Female Sheep. Endocrinology. 2015. September;156(9):3277–91. PubMed PMID: 26061725. Pubmed Central PMCID: 4541615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Watson RE Jr., Wiegand SJ, Clough RW, Hoffman GE. Use of cryoprotectant to maintain long-term peptide immunoreactivity and tissue morphology. Peptides. 1986. Jan-Feb;7(1):155–9. PubMed PMID: 3520509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Amstalden M, Coolen LM, Hemmerle AM, Billings HJ, Connors JM, Goodman RL, et al. Neurokinin 3 receptor immunoreactivity in the septal region, preoptic area and hypothalamus of the female sheep: colocalisation in neurokinin B cells of the arcuate nucleus but not in gonadotrophin-releasing hormone neurones. Journal of neuroendocrinology. 2010. January;22(1):1–12. PubMed PMID: 19912479. Pubmed Central PMCID: 2821793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Foradori CD, Amstalden M, Goodman RL, Lehman MN. Colocalisation of dynorphin a and neurokinin B immunoreactivity in the arcuate nucleus and median eminence of the sheep. Journal of neuroendocrinology. 2006. July;18(7):534–41. PubMed PMID: 16774502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Goodman RL, Coolen LM, Anderson GM, Hardy SL, Valent M, Connors JM, et al. Evidence that dynorphin plays a major role in mediating progesterone negative feedback on gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons in sheep. Endocrinology. 2004. June;145(6):2959–67. PubMed PMID: 14988383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nestor CC, Briscoe AM, Davis SM, Valent M, Goodman RL, Hileman SM. Evidence of a role for kisspeptin and neurokinin B in puberty of female sheep. Endocrinology. 2012. June;153(6):2756–65. PubMed PMID: 22434087. Pubmed Central PMCID: 3359609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Goubillon ML, Forsdike RA, Robinson JE, Ciofi P, Caraty A, Herbison AE. Identification of neurokinin B-expressing neurons as an highly estrogen-receptive, sexually dimorphic cell group in the ovine arcuate nucleus. Endocrinology. 2000. November;141(11):4218–25. PubMed PMID: 11089556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Moenter SM, Caraty A, Karsch FJ. The estradiol-induced surge of gonadotropin-releasing hormone in the ewe. Endocrinology. 1990. September;127(3):1375–84. PubMed PMID: 2201536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fergani C, Navarro VM. Expanding the Role of Tachykinins in the Neuroendocrine Control of Reproduction. Reproduction. 2016. November 15;153(1):R1–R14. PubMed PMID: 27754872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gonzalez R, Orgeur P, Poindron P, Signoret JP. Female effect in sheep. I. The effects of sexual receptivity of females and the sexual experience of rams. Reproduction, nutrition, development. 1991;31(1):97–102. PubMed PMID: 2043264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rietema SE, Hawken PAR, Scott CJ, Lehman MN, Martin GB, Smith JT. Arcuate nucleus kisspeptin response to increased nutrition in rams. Reproduction, fertility, and development. 2019. September 12. PubMed PMID: 31511141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Birch RA, Padmanabhan V, Foster DL, Unsworth WP, Robinson JE. Prenatal programming of reproductive neuroendocrine function: fetal androgen exposure produces progressive disruption of reproductive cycles in sheep. Endocrinology. 2003. April;144(4):1426–34. PubMed PMID: 12639926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.McCosh RM, Lopez JA, Szeligo BM, Bedenbaugh M, Hileman S, Coolen LM, et al. Evidence that Nitric Oxide from Somatostatin-containing Neurons is Critical for the LH Surge in Sheep. Endocrinology. 2020;161:1–11 doi: 0.1210/endocr/bqaa010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Robinson JE, Grindrod J, Jeurissen S, Taylor JA, Unsworth WP. Prenatal exposure of the ovine fetus to androgens reduces the proportion of neurons in the ventromedial and arcuate nucleus that are activated by short-term exposure to estrogen. Biology of reproduction. 2010. January;82(1):163–70. PubMed PMID: 19741207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Evans NP, Richter TA, Skinner DC, Robinson JE. Neuroendocrine mechanisms underlying the effects of progesterone on the oestradiol-induced GnRH/LH surge. Reproduction. 2002;59:57–66. PubMed PMID: 12698973. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Goodman RL, Inskeep EK. Control of the ovarian cycle of the sheep In: Plant TM, Zeleznik AJ, editors. Knobil and Neill’s Physiology of Reproduction, Fourth Edition 2 Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2015. p. 1259–305. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Smith JT, Li Q, Yap KS, Shahab M, Roseweir AK, Millar RP, et al. Kisspeptin is essential for the full preovulatory LH surge and stimulates GnRH release from the isolated ovine median eminence. Endocrinology. 2011. March;152(3):1001–12. PubMed PMID: 21239443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]