Abstract

Background Social determinants of health play an important role in the likelihood of readmission and therefore should be considered in care transition planning. Unfortunately, some social determinants that can be of value to care transition planners are missing in the electronic health record. Rather than trying to understand the value of data that are missing, decision makers often exclude these data. This exclusion can lead to failure to design appropriate care transition programs, leading to readmissions.

Objectives This article examines the value of missing social determinants data to emergency department (ED) revisits, and subsequent readmissions.

Methods A deidentified data set of 123,697 people (18+ years), with at least one ED visit in 2017 at the University of Alabama at Birmingham Medical Center was used. The dependent variable was all-cause 30-day revisits (yes/no), while the independent variables were missing/nonmissing status of the social determinants of health measures. Logistic regression was used to test the relationship between likelihood of revisits and social determinants of health variables. Moreover, relative weight analysis was used to identify relative importance of the independent variables.

Results Twelve social determinants were found to be most often missing. Of those 12, only “lives with” (alone or with family/friends) had higher odds of ED revisits. However, relative logistic weight analysis suggested that “pain score” and “activities of daily living” (ADL) accounted for almost 50% of the relevance for ED revisits when compared among all 12 variables.

Conclusion In the process of care transition planning, data that are documented are factored into the care transition plan. One of the most common challenges in health services practice is to understand the value of missing data in effective program planning. This study suggests that the data that are not documented (i.e., missing) could play an important role in care transition planning as a mechanism to reduce ED revisits and eventual readmission rates.

Keywords: care transitions, data missingness, social determinants

Background and Significance

Social determinants of health (SDH) are the social (as opposed to biological or genetic) contributors to one's health status. They include socioeconomic status, education, physical environment, employment, social support systems, and access to health care 1 as well as the downstream determinants that influence health, including health-related knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors. 2 In 2008, the World Health Organization's (WHO) Commission on Social Determinants of Health recommended that there be widespread measurement and understanding of the problem and that the results of SDH action be assessed. 3 Likewise, addressing SDH factors through research, practice, and policy was suggested as an important tool for improving health outcomes and reducing widespread health disparities. As a result, an increased number of initiatives, in both the health and nonhealth sectors, sought to address SDH to improve health across the care continuum, from wellness initiatives to hospital to home care transitions. Many studies throughout Europe, North America, and Asia have used models to explore the relationship between SDH and health conditions and mortality. 4 For example, housing policies (i.e., rental assistance) can help improve overall health and increase beneficial health behaviors. 5

In a hospital setting, the role of SDH in care transition planning has been studied as a potential predictor of 30-day readmission rates. 6 7 8 For example, Herrin et al found that higher hospital readmission rates were found in counties that had higher percentages of residents who never married and lower employment designations. 9 Patients who lived alone had an unmet functional needs, lacked self-management skills, and/or had limited education levels, and also were at increased risk of early readmission to hospitals. 10 Therefore, consistent with the work of Braveman et al and the WHO, 3 these were included in our expanded view of SDH. Furthermore, Barnett et al found an association between hospital admission and SDH variables such as gender, race/ethnicity, education level, employment status, and household income. 6 It is acknowledged, however, that the SDH variables included for data collection, contribution to care transitions, and research are likely to change over time.

Readmission rates are impacted by SDH. 11 Since half of hospital admissions originate in the emergency department (ED), 12 it is important to understand SDH factors proximally as a mitigating factor to ED visits, in particular repeated visits (revisits), and more distally as a mitigating factor to hospital readmissions. For example, patient-level factors, such as SDH; provider-level factors, like medical errors 13 ; and illness-related factors, such as the severity and type of illness 14 15 16 17 individually and collectively contribute to readmission rates.

While clinical data have historically been used in predictive models on ED revisits, the role of SDH data as the hook into those clinical data to provide greater insight into a care transition bridge has not been fully examined. 14 18 Even though studies suggest that collection of SDH improves continuity during care transitions, collection remains inconsistent. 18 19 For example, a study by Hewner et al suggests that until systematic collection of SDH was enacted, consistent collection was a challenge. 19 Some SDH data are only collected from the nationally representative Health and Retirement Study and can retrospectively be linked to patient data. However, this can result in up to 10% of the items of interest missing from the data. 6 Even with self-reported data, up to 25% of some SDH variables can be missing for some cohorts. 20 Widespread missing data may artificially create more variation in the revisit estimates. 21 To alleviate this problem during statistical analysis, many researchers exclude SDH variables with high levels of missingness, 6 20 21 use multiple imputation mechanisms, 8 22 or use other weighting procedures. 23 While these methods are sound, there is a need to gather a more relevant SDH history on patients to understand the significance of SDH across the care continuum, including transitioning to care at home. Health care delivery information systems often have limited resources and therefore must pay attention to collecting only the most critical data elements. Understanding whether a variable actually leads to better information about a patient, including their risk of an ED revisit or hospital readmission, is therefore critically important. There is an inherent value to these missing data as they may capture a more holistic picture of the most vulnerable patients and communities. Therefore, health systems must rationalize and be thoughtful about which data elements they should spend time collecting.

Objectives

The purpose of this exploratory study is to examine the role SDH variables play in predicting ED revisits. To that end, we examine the role that missing SDH data play in care transition planning as a means to decrease ED revisits, thereby decreasing readmissions, and seek to answer the following question: “Of the SDH data that are most often missing from the electronic health record (EHR), which variables are most predictive of revisits to the ED?” In answering this, we expect to have a set of SDH variables that are often not collected, but that if collected would provide care transition teams with relevant information to include in care transition planning.

Methods

Deidentified data were collected from the Cerner EHR at the University of Alabama at Birmingham Medical Center (UABMC) for the time period between January and December of 2017. Exclusion criteria were < 18 years of age, pregnancy, and death at hospital ( n = 3,403). The final analytic sample was 123,697 unique patients. SDH data collection occurs primarily at ED registration and then sporadically throughout the ED visit until discharge through discrete questions asked of the patient or family. The primary SDH categories are:

Activities of daily living (ADL).

Abuse.

Alcohol.

Employment/School.

Exercise.

Home environment.

Nutrition.

Sexual.

Substance abuse.

Tobacco.

The dependent variable was all-cause 30-day ED revisit. Since a patient could have multiple revisits to the ED in 2017, we isolated the first visit to use in the analyses. The independent variables were missing/nonmissing status of the SDH measures ( Table 1 ). We controlled for patients' demographic information. The area deprivation index (ADI) was used to control for community characteristics. ADI, originally developed by Singh, is a composite index of ZIP-code level neighborhood indicators such as poverty, education, and housing. 24

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of the sample ( N = 123,697) .

| Variables | Frequency | % | Variables | Frequency | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Revisits | Pain scores | ||||

| No | 104,947 | 84.84 | Low | 17,054 | 13.79 |

| Yes | 18,750 | 15.16 | Medium | 31,926 | 25.81 |

| Age | High | 15,203 | 12.29 | ||

| 18–44 | 61,542 | 49.75 | Missing | 59,514 | 48.11 |

| 45–64 | 38,779 | 31.35 | Body mass index | ||

| 65+ | 23,376 | 18.90 | Underweight | 2,933 | 2.37 |

| Gender | Normal weight | 33,373 | 26.98 | ||

| Female | 69,393 | 56.10 | Overweight | 34,167 | 27.62 |

| Male | 54,304 | 43.90 | Obese | 47,620 | 38.50 |

| Race | Missing | 5,604 | 4.53 | ||

| White | 59,887 | 48.41 | Education level | ||

| Black | 56,246 | 45.47 | Less than high school | 2,786 | 2.25 |

| Hispanic | 3,556 | 2.87 | High school/some college | 10,916 | 8.82 |

| Other | 4,008 | 3.24 | University/graduate | 2,994 | 2.42 |

| Marital status | Missing | 107,001 | 86.50 | ||

| Single | 60,558 | 48.96 | Employment status | ||

| Married | 44,567 | 36.03 | Disabled | 11,767 | 9.51 |

| Divorced/separated | 11,681 | 9.44 | Employed | 25,268 | 20.43 |

| Widowed | 6,891 | 5.57 | Retired | 13,045 | 10.55 |

| Insurance status | Unemployed | 13,345 | 10.79 | ||

| Self-pay | 28,145 | 22.75 | Missing | 60,272 | 48.73 |

| Medicaid | 17,214 | 13.92 | Problem at home | ||

| Medicare | 31,538 | 25.50 | No | 12,764 | 10.32 |

| Commercial | 43,326 | 35.03 | Yes | 7,781 | 6.29 |

| Tricare/Veterans Administration | 1,945 | 1.57 | Missing | 103,152 | 83.39 |

| Workers' comp | 1,529 | 1.24 | History of abuse | ||

| Location | No | 81,981 | 66.28 | ||

| Metropolitan | 107,173 | 86.64 | Low | 3,432 | 2.77 |

| Micropolitan | 9,549 | 7.72 | High | 1,080 | 0.87 |

| Small town | 4,674 | 3.78 | Missing | 37,204 | 30.08 |

| Rural area | 2,301 | 1.86 | Home equipment | ||

| ADI | No | 20,156 | 16.29 | ||

| Low | 32,936 | 26.63 | Yes | 15,135 | 12.24 |

| Medium | 65,583 | 53.02 | Missing | 88,406 | 71.47 |

| High | 25,178 | 20.35 | ADL | ||

| Comorbidities (count) | Independent | 27,829 | 22.50 | ||

| Low | 49,407 | 39.94 | Needs some help | 4,672 | 3.78 |

| Medium | 62,370 | 50.42 | Dependent | 1,979 | 1.6 |

| High | 11,920 | 9.64 | Missing | 89,217 | 72.13 |

| Mobility assistance | Substance abuse | ||||

| Independent | 11,589 | 9.37 | None | 90,367 | 73.06 |

| Partial assistance | 1,711 | 1.38 | Former | 7,201 | 5.82 |

| Total assistance | 473 | 0.38 | Current | 10,172 | 8.22 |

| Missing | 109,924 | 88.87 | Missing | 15,957 | 12.9 |

| Living situation | Tobacco use | ||||

| Home/independent | 48,970 | 39.59 | Never | 55,269 | 44.68 |

| SNF/assisted living | 1,017 | 0.82 | Former | 19,512 | 15.77 |

| Home with assistance | 4,471 | 3.61 | Light smoker | 8,529 | 6.90 |

| Homeless/shelter | 1,723 | 1.39 | Heavy smoker | 27,559 | 22.28 |

| Missing | 67,516 | 54.58 | Missing | 12,828 | 10.37 |

| Living with | Appetite | ||||

| Alone | 17,885 | 14.46 | Good | 26,712 | 21.59 |

| With family/friends | 58,386 | 47.20 | Fair | 7,313 | 5.91 |

| Missing | 47,426 | 38.34 | Poor | 4,374 | 3.54 |

| Alcohol use | Missing | 85,298 | 68.96 | ||

| None | 58,510 | 47.30 | Feeding ability | ||

| Rarely | 24,328 | 19.67 | Independent | 16,725 | 13.52 |

| Once a week | 10,742 | 8.68 | Minimal assistance | 954 | 0.77 |

| Several times a week | 8,799 | 7.11 | Total assistance | 301 | 0.24 |

| Several times a day | 799 | 0.65 | Missing | 105,717 | 85.46 |

| Missing | 20,519 | 16.59 |

Abbreviations: ADI, area deprivation index; ADL, activities of daily living; SNF, skilled nursing facility.

In terms of comorbidities, the number of comorbidities was categorized into three groups using the 25th and 75th percentiles of the comorbidity variable where the low comorbidity group had 1 to 2 health conditions (< 25th percentile), medium comorbidity group had 3 to 5 conditions, and the high comorbidity group had more than 5 conditions (> 75th percentile).

Logistic regression was used to test the relationship between the missing and nonmissing value in the likelihood of a return ED visit. Additionally, relative logistic weight analysis, as an adjunct to logistic regression, is particularly useful as a mechanism for further understanding the role of each SDH variable in predicting all-cause 30-day revisit rate. 25 Unlike traditional regression analyses that focus on statistical and practical significance, relative logistic weight analysis enables us to identify each predictor variable's relative contribution to the total predicted criterion variance—an index that involves the predictor variable's direct effect and its joint effect with other predictive variables. 25 We used the SDH variables that had at least 30% nonmissing data in logistic regression and relative weight analysis. We used a significance level of 0.05 in evaluating the statistical tests. Additionally, we conducted a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to determine statistical significance of data missingness between comorbidity groups. Lastly, we applied a Bonferroni post hoc test as a multiple comparison test to mitigate against falsely reported statistical significance. We used Stata 16 (StataCorp. 2019; Stata Statistical Software: Release 16; StataCorp LLC, College Station, Texas, United States:) and R ( http://www.R-project.org/ ) for data management and analyses.

Results

Results are presented first as the entire data set (data collected and missing), followed by results of the subset—those for whom SDH data are missing . There were 123,697 people (18+ years) who had at least one ED visit in 2017 at UABMC. The all-cause 30-day revisit rate was 15% ( n = 18,555) in our sample.

Half of the patients ( n = 61,542) were aged 18 to 44, while 19% ( n = 23,376) were over 65 years. Regarding the racial makeup of the patients, 45% ( n = 56,246) were black and 48% (59,887) white. This sample is representative of the age and racial composition of Jefferson County, the largest county in Alabama, 26 where UABMC is located. In this location, 55% of the population are between 18 and 64 years, 16% of the population are 65 years and over, 43.5% of the population are black, and 53% are white. 26 While it is representative of the state 26 regarding age, where 56% of the population are between 18 and 64 years and 17% of the population are 65 years and over, it is less representative of the state 26 regarding race, as 26.8% of the population are black and 69.1% are white. Almost half of the patients (49%, 60,558) were single. Almost one-fourth did not have any health insurance (23%, 28,145) and one-fifth (25,178) lived in high ADI communities. Two-thirds of patients (66%, 81,787) were either overweight or obese.

More common variables which are used in care transition planning and are considered SDH were collected without much variability in terms of missingness: age, gender, race, marital status, insurance status, comorbidities, body mass index, and ADI (calculated using the patient's ZIP code). The complete list of SDH variables with associated frequencies is shown in Table 1 .

Whereas Table 1 shows all SDH variables for which data are collected, our focus on the variables for which data are missing resulted in a natural cut point of 30% or greater for SDH variables with missing data. That is to say, that a more granular focus and analysis considered only SDH variables for which data were missing 30% of the time or greater. This cut point was selected as that is where there was a naturally occurring gap in the data. The SDH variables included for further analysis as to the value of these missing data are mobility assistance, education level, feeding ability, problem at home (nonspecific problems), ADL, home equipment, appetite, living situation, employment status, pain score (on a scale of 1–10 collected primarily by asking the patient), living with, and history of abuse. Table 2 shows these variables with frequencies in descending order and is provided to illuminate the subset of variables shown in Table 1 .

Table 2. Variables with missing data (30% cut point).

| Variable | Frequency | % |

|---|---|---|

| Mobility assistance | 109,924 | 88.87 |

| Education level | 107,001 | 86.50 |

| Feeding ability | 105,717 | 85.46 |

| Problem at home | 103,152 | 83.39 |

| ADL | 89,217 | 72.13 |

| Home equipment | 88,406 | 71.47 |

| Appetite | 85,298 | 68.96 |

| Living situation | 67,516 | 54.58 |

| Employment status | 60,272 | 48.73 |

| Pain score | 59,514 | 48.11 |

| Living with | 47,426 | 38.34 |

| History of abuse | 37,204 | 30.08 |

Abbreviation: ADL, activities of daily living.

Statistical Analysis

The remainder of the results focuses solely on the SDH variables shown in Table 2 as a way to focus in on the value of the missing data to care transition planning.

Logistic regression analysis of those with SDH values missing shows the variable of “living with” to be statistically significant (odds ratio = 1.127, p < 0.001) for higher odds of ED revisit ( Table 3 ).

Table 3. Logistic regression analysis of SDH missing variables.

| Variables | Odds ratio | p -Value | [95% CI] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain score | 0.497 a | < 0.05 | 0.478 | 0.517 |

| History of abuse | 0.813 a | < 0.05 | 0.772 | 0.857 |

| ADL | 0.667 a | < 0.05 | 0.639 | 0.695 |

| Education level | 0.902 a | < 0.05 | 0.862 | 0.944 |

| Employment status | 0.913 a | < 0.05 | 0.872 | 0.956 |

| Home equipment | 0.961 | 0.09 | 0.918 | 1.006 |

| Mobility assistance | 0.944 | 0.07 | 0.887 | 1.004 |

| Living situation | 0.801 a | < 0.05 | 0.765 | 0.839 |

| Living with | 1.127 a | < 0.05 | 1.072 | 1.184 |

| Appetite | 0.928 a | < 0.05 | 0.888 | 0.971 |

| Feeding ability | 0.888 a | < 0.05 | 0.843 | 0.936 |

| Problems at home | 0.756 a | < 0.05 | 0.716 | 0.798 |

Abbreviations: ADL, activities of daily living; CI, confidence interval; SDH, social determinants of health.

Note: Pseudo- R 2 = 0.07. Control variables: age, gender, race, marital status, insurance status, location, and area deprivation index.

Statistical significance < 0.05.

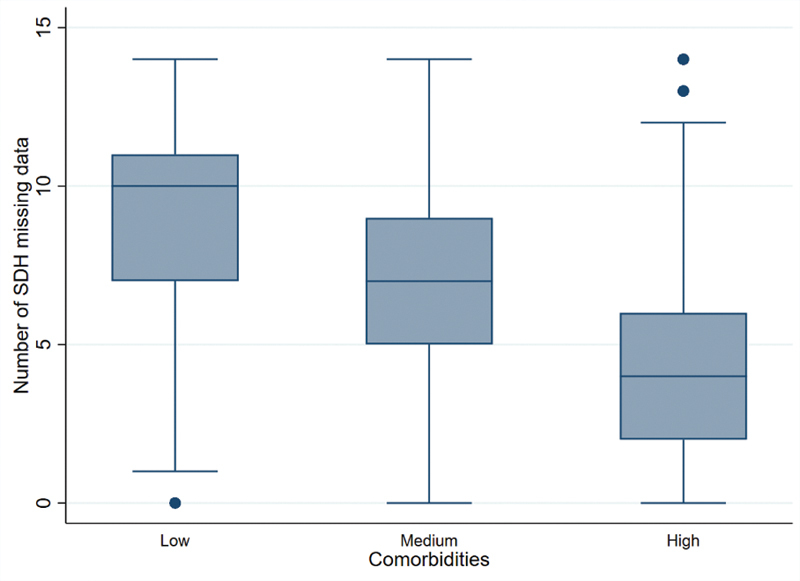

Looking at records in which SDH data were most likely to be missing, the one-way ANOVA analysis ( Fig. 1 ) showed a statistically significant difference in the overall missingness between comorbidity groups ( F [2, 123,694] = 15,660.43, p < 0.05). A Bonferroni post hoc test showed that the numbers of missing values were significantly lower in medium (6.8 ± 3.3, p < 0.001) and high (4.4 ± 2.9, p < 0.001) comorbidity groups, compared with the low comorbidity group (9.5 ± 3.2).

Fig. 1.

The number of social determinants of health (SDH) missing values across comorbidity groups ( N = 123,697).

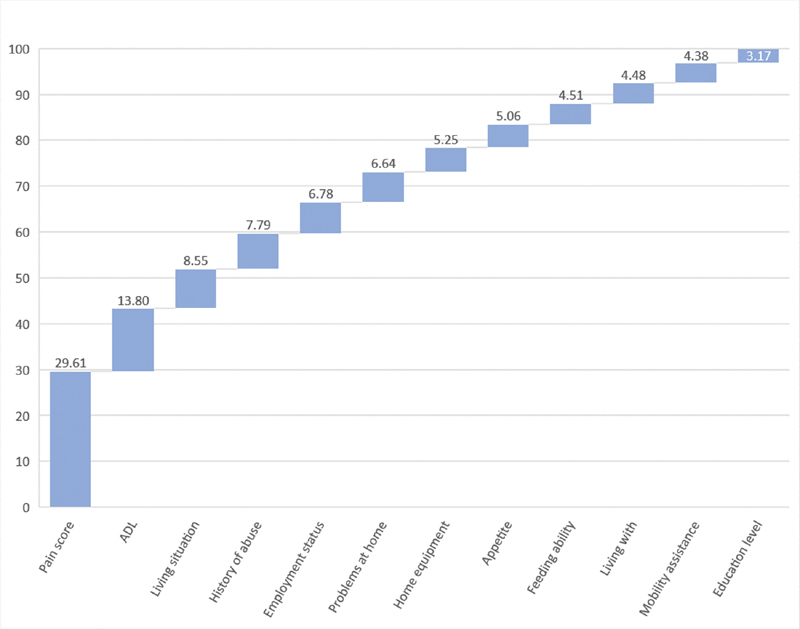

Next, we looked at the SDH variables at or above the cut point of 30% to understand the degree to which each variable independently and relatively contributed to the model. This relativity is on a 0 to 100 scale and is shown in decreasing relevance of each variable to the entire set of SDH variables ( Fig. 2 ). In comparing all of the SDH variables that were at or above the 30% cut point, the relative logistic weight analysis shows that pain score is the most important variable in predicting the likelihood of revisit (29.61/100), followed by ADLs (13.80/100). After pain score and ADL, which collectively account for almost 50% of the relevance (43.31/100), other SDH variables are all under 10% individually, with education level (3.17/100) having the least relevance when compared with the other variables.

Fig. 2.

Relative logistic weight analysis of missing data to revisit.

Discussion

In the process of care transition planning, data are documented and factored into the care transition plan. One of the most common challenges in health services practice and research is to work with missing data. While there are a variety of reasons that data are missing, it is generally agreed that missing data disrupt analysis and practice, and so missing values are often imputed or not factored in at all. 27 28 An ideal data set would be valid, reliable, complete, and relevant. 29 In this study, we examined the role played by these last two characteristics, completeness and relevance, in understanding the value of SDH variables and their relevant contribution during care transition planning to avoid readmission.

This study suggests that the data that are not documented (i.e., missing) could play an important role in care transition planning as a mechanism to reduce readmission rates. To illustrate that, this study examined the relationship between SDH values that were missing from the EHR and ED revisit rates as a method for understanding the relative importance and contribution of SDH variables in planning for care transitions. In our study, except for the variable “living with,” most missingness of SDH values was associated with lower revisit rates. In other words, if the data were missing, the patient was less likely to have revisited, except for knowing who the patient lives with. However, when we further examined the relative weight of each variable, 25 we saw that pain score and ADLs are valuable SDH variables. Additionally, we found that those with fewer comorbidities, and therefore assumed to be healthier, were less likely to have missing SDH data ( Supplementary Tables S1 and S2 , available in the online version). It is important to note that we examined associations and not causality.

This study had several limitations. The first limitation is that SDH data have really only been consistently collected in the EHR since approximately 2016. Even though UABMC has had the ability to collect all of these variables for over a decade, there was collection of only those thought to be “important.” To mitigate this limitation, the period of data collection was set to 2017. Our thinking was that this would increase the likelihood of fewer missing values. Since we did not analyze pre-2017 data, we do not know if this was actually the case. Another limitation of this study is attribution of “value” to data missingness. In terms of finding value to data that are missing, we employed several different analytical approaches to gain an understanding of the value, with a tolerance for results that are not statistically significant, but show relevance. Sensitivity of some variables can also be a barrier to collecting data. Some information such as the history of abuse and substance abuse are very sensitive; the providers may avoid asking those questions or patients may not be honest in responding. Additionally, a study by Feller et al suggests that combining unstructured free text and structured data together may provide a more comprehensive view of the SDH status of a patient, our use of only structured data represents a limitation. 30 The setting for this study was a large urban academic medical center with a large representation of minorities, high ADI, and high percentage of overweight patients. As such, generalizability beyond organizations with similar demographics may be limited. Lastly, EHR data may not be the most reliable indicator of ED revisits because we only know ED revisits to our hospital. Access to claims data for use in calculating the 30-day ED revisit rate could have captured unknown visits.

Conclusion

One of the unexpected findings of this study was that missingness was associated with fewer comorbidities. In other words, the less sick patients had more missing SDH data. There could be any number of reasons for this, including implicit bias, or it could have something to do with workflow. Regardless, this is an area for further study. We also concluded that missing SDH data have value. For example, the relevant contribution of pain and ADLs suggest an opportunity for better connections between care transition and home health teams. This one study cannot determine the compulsory nature with which the missing data should be collected, but this also deserves further study.

Clinical Relevance Statement

Because it is human nature to focus on the data that we see and trust 31 and disregard that which we do not see, this study has important clinical implications in determining SDH data that should be considered for collection. Including in care transition planning additional data elements shown to be most predictive to readmission, even if not statistically significant, could factor into lower readmission rates. For instance, knowing that an unmarried patient is more likely to end up in the ED within the next 30 days, the care transition team may need to spend more time educating him/her making sure that he/she takes her medications on time. While this will require additional staff time, it may be worth if it can reduce the revisits to the ED.

Multiple Choice Questions

1. When considering critical data for care transition planning, data that are usually missing would be of most value?

Mobility assistance, education level, and feeding ability.

History of abuse, lives with, and pain score.

Pain score, lives with, and ADL.

Problem at home, feeding ability, and appetite.

Correct Answer: The correct answer is c. Twelve social determinants were found to be most often missing. Of those 12, only “lives with” (along or with family/friends) was significant for higher odds of ED revisits. However, relative logistic weight analysis suggested that “pain score” and activities of daily living (“ADL”) accounted for almost 50% of the relevance for ED revisits when compared among all 12 variables.

2. SDH data can be helpful in care transition planning because:

All data play an important role in the care transition process.

All data are equally important and therefore should be collected.

Care transition teams rely on every data element to make care transition plans.

Certain SDH data can be more predictive of readmission.

Correct Answer: The correct answer is d. This study suggests that certain SDH data that are not documented (i.e., missing) could play an important role in care transition planning as a mechanism to reduce ED revisits and eventual readmission rates.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge that this manuscript was significantly strengthened through the careful and thoughtful comments of the reviewers. The authors further acknowledge the early work of Aizhan Karabukayeva in her contribution toward the initial literature review.

Funding Statement

Funding We would like to acknowledge funding support from the National Science Foundation's Center for Healthcare Organization and Transformation (CHOT) grant NSF1624690 as well as the Faculty Development Grant Program at UAB.

Conflict of Interest S.F. reports grants from UAB and NSF during the conduct of this study and reports no other conflicts of interest in the research. Authors D.G. and A.H. each report NSF funding.

Protection of Human and Animal Subjects

This study was conducted under the UAB Institutional Review Board IRB # 300001679.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Artiga S, Hinton E. Beyond health care: the role of social determinants in promoting health and health equity. Health. 2019;20(10):1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Braveman P, Egerter S, Williams D R. The social determinants of health: coming of age. Annu Rev Public Health. 2011;32:381–398. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031210-101218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marmot M, Friel S, Bell R, Houweling T A, Taylor S.Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health Lancet 2008372(9650):1661–1669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pedrana L, Pamponet M, Walker R, Costa F, Rasella D. Scoping review: national monitoring frameworks for social determinants of health and health equity. Glob Health Action. 2016;9(01):28831. doi: 10.3402/gha.v9.28831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bambra C, Gibson M, Sowden A, Wright K, Whitehead M, Petticrew M. Tackling the wider social determinants of health and health inequalities: evidence from systematic reviews. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2010;64(04):284–291. doi: 10.1136/jech.2008.082743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barnett M L, Hsu J, McWilliams J M. Patient characteristics and differences in hospital readmission rates. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(11):1803–1812. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.4660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hasan O, Meltzer D O, Shaykevich S A. Hospital readmission in general medicine patients: a prediction model. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(03):211–219. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1196-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Inacio M C, Kritz-Silverstein D, Raman R. The impact of pre-operative weight loss on incidence of surgical site infection and readmission rates after total joint arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(03):458–464. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2013.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herrin J, St Andre J, Kenward K, Joshi M S, Audet A MJ, Hines S C. Community factors and hospital readmission rates. Health Serv Res. 2015;50(01):20–39. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arbaje A I, Wolff J L, Yu Q, Powe N R, Anderson G F, Boult C. Postdischarge environmental and socioeconomic factors and the likelihood of early hospital readmission among community-dwelling Medicare beneficiaries. Gerontologist. 2008;48(04):495–504. doi: 10.1093/geront/48.4.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldstein J N, Hicks L S, Kolm P, Weintraub W S, Elliott D J. Is the care transitions measure associated with readmission risk? Analysis from a single academic center. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(07):732–738. doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3610-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pitts S R, Carrier E R, Rich E C, Kellermann A L. Where Americans get acute care: increasingly, it's not at their doctor's office. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010;29(09):1620–1629. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liaw S J, Bullard M J, Hu P M, Chen J-C, Liao H-C. Rates and causes of emergency department revisits within 72 hours. J Formos Med Assoc. 1999;98(06):422–425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hao S, Jin B, Shin A Y. Risk prediction of emergency department revisit 30 days post discharge: a prospective study. PLoS One. 2014;9(11):e112944. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0112944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martin-Gill C, Reiser R C. Risk factors for 72-hour admission to the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2004;22(06):448–453. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2004.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McCusker J, Cardin S, Bellavance F, Belzile E. Return to the emergency department among elders: patterns and predictors. Acad Emerg Med. 2000;7(03):249–259. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2000.tb01070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Doran K M, Raven M C, Rosenheck R A. What drives frequent emergency department use in an integrated health system? National data from the Veterans Health Administration. Ann Emerg Med. 2013;62(02):151–159. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2013.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zangerle C M. Population health: the importance of social determinants. Nurs Manage. 2016;47(02):17–18. doi: 10.1097/01.NUMA.0000479444.75643.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hewner S, Casucci S, Sullivan S. Integrating social determinants of health into primary care clinical and informational workflow during care transitions. EGEMS (Wash DC) 2017;5(02):2. doi: 10.13063/2327-9214.1282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lofters A K, Schuler A, Slater M. Using self-reported data on the social determinants of health in primary care to identify cancer screening disparities: opportunities and challenges. BMC Fam Pract. 2017;18(01):31. doi: 10.1186/s12875-017-0599-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bardach N S, Vittinghoff E, Asteria-Peñaloza R. Measuring hospital quality using pediatric readmission and revisit rates. Pediatrics. 2013;132(03):429–436. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-3527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gustafsson P E, San Sebastian M, Janlert U, Theorell T, Westerlund H, Hammarström A. Life-course accumulation of neighborhood disadvantage and allostatic load: empirical integration of three social determinants of health frameworks. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(05):904–910. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ahnquist J, Wamala S P, Lindstrom M. Social determinants of health--a question of social or economic capital? Interaction effects of socioeconomic factors on health outcomes. Soc Sci Med. 2012;74(06):930–939. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Singh G K. Area deprivation and widening inequalities in US mortality, 1969-1998. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(07):1137–1143. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.7.1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tonidandel S, LeBreton J M. Relative importance analysis: a useful supplement to regression analysis. J Bus Psychol. 2011;26(01):1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 26.US Census Bureau. Quick Facts United States. 2020. Available at:https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045219. Accessed August 9, 2020

- 27.Rubin D B. Inference and missing data. Biometrika. 1976;63(03):581–592. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin W-C, Tsai C-F. Missing value imputation: a review and analysis of the literature (2006–2017) Artif Intell Rev. 2020;53(02):1487–1509. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Columb M O, Haji-Michael P, Nightingale P. Data collection in the emergency setting. Emerg Med J. 2003;20(05):459–463. doi: 10.1136/emj.20.5.459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Feller D J, Bear Don't Walk Iv O J, Zucker J, Yin M T, Gordon P, Elhadad N. Detecting social and behavioral determinants of health with structured and free-text clinical data. Appl Clin Inform. 2020;11(01):172–181. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1702214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Le T D, Beuran R, Tan Y.2018: IEEE; 2018247–251.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.