Abstract

Objective

The objective of this study was to evaluate causes of death in a contemporary inception cohort of ANCA-associated vasculitis patients, stratifying the analysis according to ANCA type.

Methods

We identified a consecutive inception cohort of patients newly diagnosed with ANCA-associated vasculitis from 2002 to 2017 in the Partners HealthCare System and determined vital status through the National Death Index. We determined cumulative mortality incidence and standardized mortality ratios (SMRs) compared with the general population. We compared MPO- and PR3-ANCA+ cases using Cox regression models.

Results

The cohort included 484 patients with a mean diagnosis age of 58 years; 40% were male, 65% were MPO-ANCA+, and 65% had renal involvement. During 3385 person-years (PY) of follow-up, 130 patients died, yielding a mortality rate of 38.4/1000 PY and a SMR of 2.3 (95% CI: 1.9, 2.8). The most common causes of death were cardiovascular disease (CVD; cumulative incidence 7.1%), malignancy (5.9%) and infection (4.1%). The SMR for infection was greatest for both MPO- and PR3-ANCA+ patients (16.4 and 6.5). MPO-ANCA+ patients had an elevated SMR for CVD (3.0), respiratory disease (2.4) and renal disease (4.5). PR3- and MPO-ANCA+ patients had an elevated SMR for malignancy (3.7 and 2.7). Compared with PR3-ANCA+ patients, MPO-ANCA+ patients had a higher risk of CVD death [hazard ratio 5.0 (95% CI: 1.2, 21.2]; P = 0.03].

Conclusion

Premature ANCA-associated vasculitis mortality is explained by CVD, infection, malignancy, and renal death. CVD is the most common cause of death, but the largest excess mortality risk in PR3- and MPO-ANCA+ patients is associated with infection. MPO-ANCA+ patients are at higher risk of CVD death than PR3-ANCA+ patients.

Keywords: ANCA-associated vasculitis, mortality, cardiovascular disease, cause of death

Rheumatology key messages

In a contemporary ANCA-associated vasculitis (AAV) cohort, cardiovascular disease (CVD) was the most common cause of death.

Differences in mortality between AAV patients and the general population were largely due to infection.

Compared with PR3-ANCA+, MPO-ANCA+ patients were at a 5-fold higher risk of CVD death.

Introduction

ANCA-associated vasculitis (AAV) is a small-vessel vasculitis associated with excess morbidity and premature death. Poor outcomes are attributable both to the effects of treatment as well as the underlying disease. Previous studies have found that mortality is approximately 3-fold higher among AAV subjects compared with the general population [1]. However, contemporary data regarding cause of death in AAV remain scarce, and although growing appreciation of differences between patients with different ANCA types exists, no analysis has evaluated causes of death among patients with ANCA directed against MPO (i.e. MPO-ANCA) as opposed to PR3 (PR3-ANCA).

Previous studies evaluating cause of death were limited by the inclusion of only granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) patients identified in claims databases [2–5] or subjects who participated in clinical trials [6]; the absence of data pertaining to ANCA testing [2, 3, 7]; a lack of comprehensive death certificate data [2–4, 6, 8]; and small sample size [7–10]. Understanding cause of death in a contemporary inception AAV cohort stratified by ANCA type may inform personalized patient care, with the goal of improving overall survival [5].

Most AAV patients are PR3- or MPO-ANCA positive at some point in their disease course [11]. ANCAs contribute substantially to disease pathophysiology, but the triggering mechanisms for the loss of tolerance leading to the production of these autoantibodies remain poorly understood [12, 13]. Classifications of AAV patients based on ANCA type are increasingly preferred to categorizations of patients according to clinicopathologic diagnoses, e.g. GPA vs microscopic polyangiitis (MPA) [14]. PR3- and MPO-ANCA+ patients are distinguished by their genetics [15], organ manifestations [16], and responses to treatment [17], each of which may contribute to differences in all-cause and cause-specific mortality according to ANCA type. Identifying differences in cause of death between PR3- and MPO-ANCA+ patients can therefore expand our understanding of their role in AAV and its complications, in addition to informing personalized management according to ANCA type to improve cause-specific mortality.

We evaluated causes of death in a contemporary inception cohort of AAV patients, stratifying the analysis according to ANCA type.

Methods

Data source

The Partners AAV (PAAV) Cohort is an inception cohort that includes AAV patients evaluated and managed in Partners HealthCare, a large healthcare system that includes tertiary care and community hospitals as well as primary care and specialty outpatient clinics, providing healthcare for more than half of the greater Boston area population. Incident cases diagnosed between 1 January 2002 and 31 December 2017 were identified using a validated algorithm [18]. This algorithm identifies patients with at least one billing code associated with AAV, a free-text reference to AAV-related keywords using natural language processing, and a positive PR3- or MPO-ANCA. In a validation study, this algorithm had a positive predictive value of 95% diagnosis for identification of AAV cases. For each case included herein, the diagnosis of AAV was systematically validated by manual chart review using a previously described approach [19]. We excluded 13 patients with eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis from this study, as well as 18 patients with incomplete baseline information. This study was approved by the Partners HealthCare Institutional Review Board. Informed consent was waived because of the retrospective nature of the study.

Assessment of exposure and covariates

Demographics and disease-specific features, including PR3- and MPO-ANCA specificity and baseline manifestations to determine the BVAS/granulomatosis with polyangiitis (BVAS/WG) were extracted from the electronic medical record. Baseline renal involvement was assessed by the presence of BVAS/WG renal domain items. Date of treatment initiation was determined based on the prescription of immunosuppression for a diagnosis of AAV.

Assessment of outcomes

Outcomes of interest were all-cause and cause-specific mortality. Death certificates were obtained based on name, date of birth, sex, and social security number from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Death Index [20–22]. For each death certificate, the underlying cause of death (the disease or injury that initiated the series of morbid events leading directly to death) was extracted. Cause of death was organized using a validated schema that clusters diagnoses into clinically meaningful categories [23], such as cardiovascular disease (CVD; includes acute myocardial infarction, coronary atherosclerosis, conduction abnormalities, cardiac dysrhythmias, cardiac arrest, and congestive heart failure), infection, malignancy, renal disease, and non-infectious respiratory disease based on International Statistical Classification of Diseases (ICD)-9 or ICD-10 codes.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are reported as mean (s.d.) or median and interquartile range (IQR), where appropriate. Categorical variables are reported as number (%). Person-years (PY) at risk were calculated for each person as time from the date of treatment initiation through the earlier of either their date of death or 31 December 2017. We estimated the cumulative incidence of all-cause and cause-specific mortality according to ANCA type, using age as the time scale [24] and present mortality rates per 1000 PY with 95% CI.

Standardized mortality ratios (SMRs) were estimated for overall mortality and cause-specific mortality in reference to the general New England population during the same time period [25] for the overall cohort and according to ANCA type. We chose New England because this is where nearly the entire (91%) Partners AAV (PAAV) Cohort lived. The expected number of deaths was determined using CDC WONDER data standardized by age (5-year age groups) and sex. SMRs were defined as the ratio of the observed to the expected number of deaths. For SMR analyses, PAAV cohort subjects only contributed time between the ages of 15 and 85 years, because expected numbers of deaths were not available in the CDC WONDER database outside of this age range.

We calculated mortality hazard ratios (HRs) to compare mortality according to ANCA type among all PAAV patients, using Cox proportional hazards models with age as the time scale [24]. Sex was included as a covariate in adjusted analyses. In cause-specific death analyses, we accounted for the competing risk of death due to other causes [26]. In the presence of competing risks, the effects of exposures and other covariates on the cause-specific hazard function can be modelled to describe the instantaneous rate of occurrence of the event of interest. Baseline disease features were not included in Cox proportional models because they are consequences of the disease rather than confounders. The proportional hazards assumption was tested using the Kolmogorov-type supremum test. There was no evidence of violation of the proportionality assumption (P-value > 0.05) except for the association between MPO- and PR3-ANCA+ AAV with the risk of cardiovascular-associated mortality, so we used a weighted Cox regression model for that analysis [27].

A two-sided P-value of <0.05 was considered significant in all analyses. We used SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA), and R, version 3.5.0, for all statistical analyses.

Results

Characteristics of study population

Of the 484 patients, the mean (s.d.) age at treatment initiation was 58 (±17) years, and 196 (41%) were male (Table 1). The majority (65%) were MPO-ANCA+. The mean age of PR3-ANCA+ patients was younger than that of MPO-ANCA+ patients [52 (±18) years vs 62 (±16) years, P < 0.01]. PR3-ANCA+ patients had a higher median baseline BVAS/WG than MPO-ANCA+ patients [5.0 (3.0, 7.0) vs 4.0 (3.0, 5.0); P < 0.001]. Renal involvement was present in 311 (64%) patients at baseline, with a similar frequency of renal involvement between the MPO-ANCA+ and PR3-ANCA+ patients (67% vs 60%, respectively; P = 0.2). During follow-up, 82 (17%) patients developed end-stage renal disease.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the Partners ANCA-associated vasculitis cohort

| Overall | MPO-ANCA+ | PR3-ANCA+ | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 484 | 313 | 171 |

| Demographics | |||

| Age, mean (s.d.), years | 58.2 (17.3) | 61.9 (15.8) | 51.5 (18.1) |

| Male (N, %) | 196 (40.5) | 120 (38.3) | 76 (44.4) |

| White | 395 (81.6) | 251 (80.2) | 144 (84.2) |

| Baseline disease featuresa | |||

| BVAS/WG (median, IQR) | 4.0 (3.0, 6.0) | 4.0 (3.0, 5.0) | 5.0 (3.0, 7.0) |

| HEENT involvement | 223 (46.1) | 111 (35.5) | 112 (65.5) |

| Pulmonary involvement | 198 (40.9) | 113 (36.1) | 85 (49.7) |

| Renal involvement | 311 (64.3) | 208 (66.5) | 103 (60.2) |

| End-stage renal disease (at any time) | 82 (16.9) | 59 (18.9) | 23 (13.5) |

| Initial treatmentb | |||

| Cyclophosphamide | 223 (46.1) | 145 (46.3) | 78 (45.6) |

| Rituximab | 189 (39.1) | 127 (40.6) | 62 (36.3) |

| Other | 72 (14.9) | 41 (13.1) | 31 (18.1) |

As these are a consequence of the disease, they were not treated as confounders in our analysis.

All patients received glucocorticoids as part of their initial treatment.

IQR: interquartile range; HEENT: head and neck.

All-cause and cause-specific mortality

The mean and total follow-up time was 7.0 (±4.1) years with 3385 person-years (PY). During the follow-up, there were 130 deaths such that the all-cause mortality rate was 38.4 (95% CI: 31.8, 45.0) per 1000 PY. During the first year following treatment initiation, the cumulative incidence of death was highest for death attributed to infection and CVD [0.8% (95% CI: 0.3, 2.0) and 0.8% (95% CI: 0.3, 2.0), respectively]. However, the cumulative incidence of death due to CVD became higher than other causes by 5 and 10 years following treatment initiation [3.4% (95% CI: 2.0, 5.4) and 7.1% (95% CI: 4.5, 10.4), respectively]. At 10 years, malignancy was the second most common cause of death, with a cumulative incidence of 5.9% (95% CI: 3.6, 9.0), followed by infection [4.1% (95% CI: 2.2, 6.8)], respiratory causes [2.6% (95% 1.2, 4.9)] and renal disease [1.9% (95% CI: 0.7, 4.2)].

Compared with the general population (Table 2), the SMR for all-cause mortality was 2.3 (95% CI: 1.9, 2.8). We observed significant elevations in the SMR due to specific causes of death, including infection [13.9 (95% CI: 7.9, 24.5)], renal disease [4.3 (95% CI: 1.6, 11.3)], malignancy [2.7 (95% CI: 1.8, 4.2)] and CVD [2.3 (95% CI: 1.5, 3.6)].

Table 2.

Standardized mortality rates in the Partners ANCA-associated vasculitis cohorta

| Overall | MPO-ANCA+ | PR3-ANCA+ | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 429 | 269 | 160 |

| Total patient-years (PY) | 3010 | 1759 | 1252 |

| All-cause mortality | |||

| Observed/expected deaths | 104/45 | 80/31 | 24/24 |

| Observed mortality rate (95% CI) | 34.6 (27.9, 41.2) | 45.5 (35.5, 55.4) | 19.2 (11.5, 26.8) |

| Standardized mortality ratio | 2.3 (1.9, 2.8) | 2.6 (2.1, 3.2) | 1.8 (1.2, 2.7) |

| Cardiovascular mortality | |||

| Observed/expected deaths | 19/8 | 17/6 | 2/2 |

| Observed mortality rate (95% CI) | 6.3 (3.5, 9.2) | 9.7 (5.1, 14.3) | 1.6 (0, 3.8) |

| Standardized mortality ratio | 2.3 (1.5, 3.6) | 3.0 (1.8, 4.8) | 1.7 (0.4, 8.1) |

| Infection mortality | |||

| Observed/expected deaths | 12/1 | 10/1 | 2/0 |

| Observed mortality rate (95% CI) | 4.0 (1.7, 6.2) | 5.7 (2.2, 9.2) | 1.6 (0, 3.8) |

| Standardized mortality ratio | 13.9 (7.9, 24.5) | 16.4 (8.8, 30.6) | 6.5 (1.6, 26.3) |

| Cancer mortalityb | |||

| Observed/expected deaths | 20/7 | 14/5 | 6/2 |

| Observed mortality rate (95% CI) | 6.6 (3.7, 9.6) | 8.0 (3.8, 12.1) | 4.8 (1.0, 8.6) |

| Standardized mortality ratio | 2.7 (1.8, 4.2) | 2.7 (1.6, 4.6) | 3.7 (1.5, 9.5) |

| Respiratory mortality | |||

| Observed/expected deaths | 7/4 | 6/3 | 1/1 |

| Observed mortality rate (95% CI) | 2.3 (0.6, 4.0) | 3.4 (0.7, 6.1) | 0.8 (0, 2.4) |

| Standardized mortality ratio | 2.0 (0.9, 4.2) | 2.4 (1.1, 5.4) | 0.9 (0.1, 6.4) |

| Renal mortality | |||

| Observed/expected deaths | 4/1 | 3/1 | 1/0 |

| Observed mortality rate (95% CI) | 1.3 (0, 2.6) | 1.7 (0, 3.6) | 0.8 (0, 2.4) |

| Standardized mortality ratio | 4.3 (1.6, 11.3) | 4.5 (1.4, 13.9) | 2.5 (0.3, 17.6) |

Restricted to ages 15–85 years old to estimate expected deaths.

Most common cancers included bronchus/lung cancer (n = 9) and gastrointestinal cancer (n = 6).

Cause-specific mortality according to ANCA type

Of the common causes of death in the PAAV cohort, the SMR for death due to infection was greatest for both MPO- and PR3-ANCA+ patients [16.4 (95% CI: 8.8, 30.6) and 6.5 (95% CI: 1.6, 26.3), respectively]. MPO-ANCA+ patients had a significantly elevated SMR for death due to CVD [3.0 (95% CI: 1.8, 4.8)], respiratory disease [2.4 (95% CI: 1.1, 5.4)], and renal disease [4.5 (95% CI: 1.4, 13.9)]; however, these causes were not significant among PR3-ANCA+ patients [1.7 (95% CI: 0.4, 8.1), 0.9 (95% CI: 0.1, 6.4) and 2.5 (95% CI: 0.3, 17.6), respectively]. In contrast, PR3-ANCA+ patients had a greater SMR for malignancy-associated mortality than MPO-ANCA+ patients [3.7 (95% CI: 1.5, 9.5) vs 2.7 (95% CI: 1.6, 4.6)].

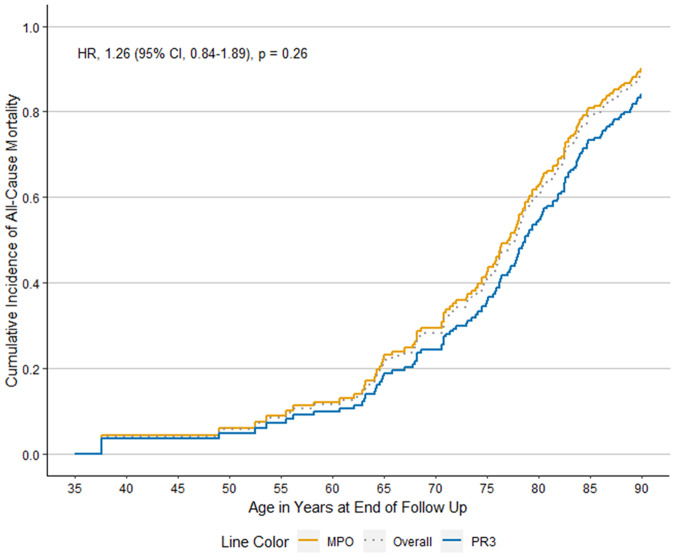

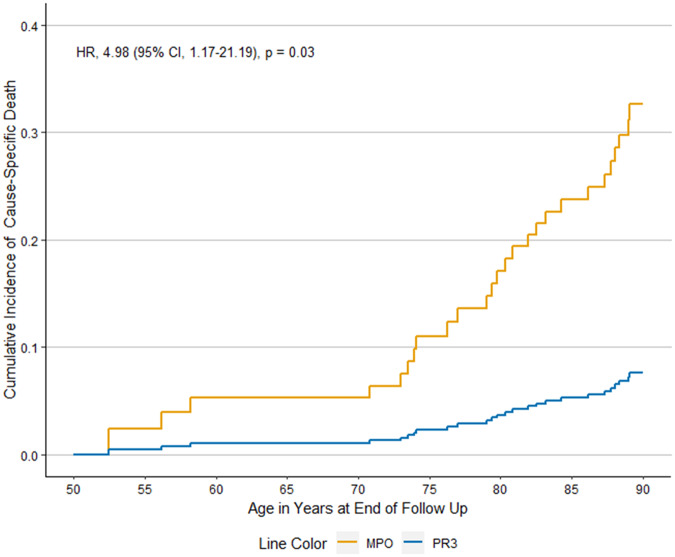

When we evaluated differences according to ANCA type in all patients in the PAAV cohort, MPO- and PR3-ANCA+ patients had similar risk of all-cause mortality in analyses that used age as the time-scale and adjusted for sex [Fig. 1; adjusted Hazard Ratio 1.3 (95% CI: 0.8, 1.9), P = 0.3]. Compared with PR3-ANCA+ patients, MPO-ANCA+ patients were at higher risk for death attributed to CVD after accounting for competing risk in analyses that used age as the time-scale and adjusted for sex [Fig. 2; aHR 5.0 (95% CI: 1.2, 21.2), P = 0.03]. We did not observe statistical significance in other potential differences in the causes of death between MPO- and PR3-ANCA+ patients (Table 3).

Fig. 1.

All-cause mortality in the Partners ANCA-associated vasculitis cohort

Fig. 2.

Cumulative incidence of CVD-specific mortality in MPO- vs PR3-ANCA+ ANCA-associated vasculitis

Table 3.

Hazard ratios for cause-specific death in MPO- vs PR3-ANCA+–associated vasculitis (AAV) in the Partners AAV cohort

| Cause of deatha | MPO-ANCA+ | PR3-ANCA+ |

|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular mortality | 5.0 (1.2, 21.2)b | 1.0 (Ref) |

| Infection mortality | 1.0 (0.3, 3.1) | 1.0 (Ref) |

| Cancer mortality | 0.9 (0.4, 2.2) | 1.0 (Ref) |

| Respiratory mortality | 3.2 (0.4, 24.3) | 1.0 (Ref) |

| Renal mortality | 1.9 (0.3, 14.1) | 1.0 (Ref) |

The risk of cause-specific death was determined after accounting for the competing risk of death from other causes, using age as the time-scale, and adjusting for sex.

Hazard ratio (95% CI).

AAV: ANCA-associated vasculitis.

Discussion

Using a large inception AAV cohort with diverse manifestations, we found that CVD is the most common cause of death and that MPO-ANCA+ patients have a greater risk of death due to CVD compared with PR3-ANCA+ patients. Compared with the general population, however, infection-related death contributes most to the higher relative risk of death in AAV. Therefore, interventions to address CVD risk, especially for MPO-ANCA+ patients, and risk of infection in all AAV patients appear warranted. Malignancy, respiratory disease, and renal disease also contribute to the excess risk of death in AAV.

Recent studies suggest that dichotomizing AAV subjects based on ANCA type rather than pathologic phenotype (e.g. GPA vs MPA) is more relevant to studying this condition and providing care [17, 28]. To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate cause-specific mortality according to ANCA type. We found a higher risk of CVD-specific mortality among MPO-ANCA+ compared with PR3-ANCA+ patients. These findings expand upon a prior study that reported an association between MPO-ANCA type and an increased risk of fatal and non-fatal CVD events [29]. That prior study had limited generalizability because the study subjects were those enrolled in clinical trials, with the majority with severe renal disease, diagnosed prior to 2002. To that end, our findings provide contemporary, more generalizable benchmarks to guide interventions specific to addressing the increased risk of CVD mortality, particularly in MPO-ANCA+ cases. Additional studies are necessary to understand why MPO-ANCA+ patients might be at higher risk for CVD-associated death than PR3-ANCA+ patients and whether this might be mediated by differences in pathogenesis (e.g. fibrosis), subclinical cardiac involvement, renal involvement, disease control, or other risk factors [28]. While additional studies are pursued, it is likely prudent to routinely assess CVD risk using available risk calculators and consider having a lower threshold for addressing CVD risk factors (e.g. dyslipidaemia, obesity, hypertension) in patients with MPO-ANCA+ disease [30, 31].

Malignancy was a common cause of death in both MPO- and PR3-ANCA+ patients. A recent general population-based study of GPA patients did not find excess mortality due to malignancy in comparison with controls [2], despite finding a malignancy-associated mortality rate that was similar to ours. This discrepancy may be explained by several factors. First, our study was not limited to patients with GPA. Second, CYC and rituximab were used more often in our study than in that general population study (85% vs 54%). This may indicate that patients in the general population study may have had less severe disease and less exposure to potential carcinogens (i.e. CYC). Additional studies should further clarify factors responsible for the excess risk of death due to malignancy.

In contrast to the other US-based AAV mortality study [8], we found that both MPO- and PR3-ANCA+ patients, rather than only MPO-ANCA+ patients, had an elevated SMR compared with the general population. The small sample sized included in the prior study—only 17 patients were PR3-ANCA+—likely limited their ability to detect an elevated SMR in PR3-ANCA+ patients. Previous studies have found that GPA patients, the majority of whom are PR3-ANCA+, also have an increased risk of death compared with the general population [2–5].

Similarities between our results and those of previous studies support the external validity of the PAAV cohort. The overall mortality rate in our study (38.4/1000 PY) was similar to that described in other cohorts, including ones from Canada (41.9/1000 PY) [2] and the UK (35.7/1000 PY) [5]. Moreover, the observed overall SMR of 2.3 in our study is similar to that reported in a recent meta-analysis (2.7) [1]. Though previous studies have suggested that CVD and infection are common causes of death in AAV [2, 3, 6, 32], our approach expands upon these findings. We clarify the difference between CVD as the most common cause of death, but infection as the most important driver of the excess risk of death compared with the general population.

Prior mortality and cause of death studies had limited generalizability because they enrolled only GPA patients [2–4], were performed using clinical trial cohorts [6], were of limited size [7–10], or relied on incomplete cause-of-death data [2–4, 6]. In contrast, we included PR3- and MPO-ANCA+ patients diagnosed after 2002 in a variety of clinical settings (e.g. rheumatology, nephrology, pulmonary) for their AAV care. We systematically collected cause-of-death data from a national database frequently used to conduct cause-of-death analyses across specialties [20–22]. Moreover, we used an external reference population (New England general population), compared MPO- vs PR3-ANCA+ patients, and utilized robust methods to account for competing risk of death.

Despite these strengths, our study has certain limitations. First, the generalizability of our findings may be limited because our cohort was assembled from the Partners HealthCare System, which includes two tertiary care facilities. The Partners HealthCare system also includes a specialty nephrology clinic in which many patients with AAV are evaluated and managed. However, the Partners HealthCare System also includes primary care clinics and community hospitals. Because of the complexities of AAV management, many patients receive care across the spectrum of healthcare settings. Moreover, as discussed above, our mortality estimates were similar to those reported in general population studies, which speaks to the generalizability of our results [2–4, 6]. Second, our cohort only includes AAV patients who were ANCA positive, thereby drawing a distinction between our cohort and the small population of AAV patients who are ANCA negative [11]. ANCA tesing has evolved over recent decades. As such, assays varied across institutions included in this study and over the study period, which could have influenced the detection of cases. However, all patients in this study were ANCA positive by ELISA testing at the time of treatment initiation. Third, despite our sample size of 484 patients and 130 observed deaths, there were fewer deaths in the PR3- than in the MPO-ANCA+ patients, which may have limited our ability to detect differences in cause-specific mortality other than CVD death. Additional studies are necessary using larger cohorts with additional deaths to evaluate the impact of potentially relevant baseline comorbidities on cause-specific mortality.

In conclusion, in this large inception cohort of consecutive AAV patients, we found that the risk of premature mortality in AAV is explained by CVD, infection, malignancy, and renal death. Though CVD is the most common cause of death, the largest excess mortality risk in AAV is due to infection. Further studies are necessary to understand why cause of death, especially due to CVD, differs between MPO- and PR3-ANCA+ patients.

Funding: Z.S.W. is funded by NIH/NIAMS [K23AR073334 and L30 AR070520] and the Rheumatology Research Foundation [Scientist Development Award]. This work was funded by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases at the National Institutes of Health [K23AR073334 to Z.S.W.].

Disclosure statement: The authors have declared that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. Tan JA, Dehghan N, Chen W. et al. Mortality in ANCA-associated vasculitis: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:1566–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tan JA, Choi HK, Xie H. et al. All-cause and cause-specific mortality in granulomatosis with polyangiitis: a population-based study. Arthritis Care Res 2019;71:155–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Luqmani R, Suppiah R, Edwards CJ. et al. Mortality in Wegener’s granulomatosis: a bimodal pattern. Rheumatology 2011;50:697–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Holle JU, Gross WL, Latza U. et al. Improved outcome in 445 patients with Wegener’s granulomatosis in a German vasculitis center over four decades. Arthritis Rheum 2011;63:257–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wallace ZS, Lu N, Unizony S, Stone JH, Choi HK.. Improved survival in granulomatosis with polyangiitis: a general population-based study. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2016;45:483–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Flossmann O, Berden A, de Groot K. et al. Long-term patient survival in ANCA-associated vasculitis. Ann Rheum Dis 2011;70:488–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Heijl C, Mohammad AJ, Westman K, Hoglund P.. Long-term patient survival in a Swedish population-based cohort of patients with ANCA-associated vasculitis. RMD Open 2017;3:e000435.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Berti A, Cornec D, Crowson CS, Specks U, Matteson EL.. The epidemiology of ANCA associated vasculitis in Olmsted County, Minnesota (USA). A 20 year population-based study. Arthritis Rheumatol 2017;69:2338–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mohammad AJ, Jacobsson LT, Westman KW, Sturfelt G, Segelmark M.. Incidence and survival rates in Wegener’s granulomatosis, microscopic polyangiitis, Churg–Strauss and polyarteritis nodosa. Rheumatology 2009;48:1560–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Eriksson P, Jacobsson L, Lindell A, Nilsson JA, Skogh T.. Improved outcome in Wegener’s granulomatosis and microscopic polyangiitis? A retrospective analysis of 9 cases in two cohorts. J Intern Med 2009;265:496–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Finkielman JD, Lee AS, Hummel AM. et al. ANCA are detectable in nearly all patients with active severe Wegener’s granulomatosis. Am J Med 2007;120:643.e9–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bosch X, Guilabert A, Font J.. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies. Lancet 2006;368:404–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Halbwachs L, Lesavre P.. Endothelium–neutrophil interactions in ANCA-associated diseases. J Am Soc Nephrol 2012;23:1449–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pagnoux C, Springer J.. Editorial: classifying antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)–associated vasculitides according to ANCA type or phenotypic diagnosis: salt or pepper? Arthritis Rheumatol 2016;68:2837–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rahmattulla C, Mooyaart AL, van Hooven D. et al. Genetic variants in ANCA-associated vasculitis: a meta-analysis. Ann Rheum Dis 2016;75:1687–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hilhorst M, van Paassen P, Tervaert JWC; Limburg Renal Registry . Proteinase 3-ANCA vasculitis versus myeloperoxidase-ANCA vasculitis. J Am Soc Nephrol 2015;26:2314–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Unizony S, Villarreal M, Miloslavsky EM. et al. Clinical outcomes of treatment of anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitis based on ANCA type. Ann Rheum Dis 2016;75:1166–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wallace ZS, Stone JH, Choi HK.. Identifying ANCA-associated vasculitis cases in electronic health records using natural language processing [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol 2018;70 (Suppl. 10). [Google Scholar]

- 19. Watts R, Lane S, Hanslik T. et al. Development and validation of a consensus methodology for the classification of the ANCA-associated vasculitides and polyarteritis nodosa for epidemiological studies. Ann Rheum Dis 2006;66:222–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cowper DC, Kubal JD, Maynard C, Hynes DM.. A primer and comparative review of major US mortality databases. Ann Epidemiol 2002;12:462–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Berrington de Gonzalez A, Hartge P, Cerhan JR. et al. Body-mass index and mortality among 1.46 million white adults. N Engl J Med 2010;363:2211–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Amin J, Law MG, Bartlett M, Kaldor JM, Dore GJ.. Causes of death after diagnosis of hepatitis B or hepatitis C infection: a large community-based linkage study. Lancet 2006;368:938–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). HCUP CCS Fact Sheet Rockville, MD. 2012. www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs/ccsfactsheet.jsp (2 October 2019, date last accessed).

- 24. Cologne J, Hsu WL, Abbott RD. et al. Proportional hazards regression in epidemiologic follow-up studies: an intuitive consideration of primary time scale. Epidemiology 2012;23:565–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). CDC WONDER [Website]. 2018. https://wonder.cdc.gov/ (2 October 2019, date last accessed).

- 26. Fine JP, Gray RJ.. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc 1999;94:496–509. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lin DY, Wei LJ, Ying Z.. Checking the Cox model with cumulative sums of martingale-based residuals. Biometrika 1993;80:557–72. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cornec D, Cornec-Le Gall E, Fervenza FC, Specks U.. ANCA-associated vasculitis – clinical utility of using ANCA specificity to classify patients. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2016;12:570–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Suppiah R, Judge A, Batra R. et al. A model to predict cardiovascular events in patients with newly diagnosed Wegener's granulomatosis and microscopic polyangiitis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2011;63:588–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Yates M, Watts RA, Bajema IM, Cid MC. et al. EULAR/ERA-EDTA recommendations for the management of ANCA-associated vasculitis. Ann Rheum Dis 2016;75:1583–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ntatsaki E, Carruthers D, Chakravarty K. et al. BSR and BHPR guideline for the management of adults with ANCA-associated vasculitis. Rheumatology 2014;53:2306–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Jardel S, Puechal X, Le Quellec A. et al. Mortality in systemic necrotizing vasculitides: a retrospective analysis of the French Vasculitis Study Group registry. Autoimmun Rev 2018;17:653–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]