Abstract

Objectives

This study examined the extent, range and nature of the published literature, prison policies and technical guidance relating to the ethical conduct of health research in prisons in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).

Study design

Scoping Review.

Methods

We adhered to the five stages of the scoping review iterative process: identifying the research question, identifying relevant studies, study selection, charting the data, and collating, summarizing and content analysis of polices. Disagreements around allocation of content were resolved through team discussion. We also appraised the quality of the included articles.

Results

We included nine records that examined the ethical aspects of the conduct of health research in prisons in LMICs; eight of these were peer-reviewed publications, and one was a toolkit. Despite the unique vulnerabilities of this group, we could find no comprehensive guidelines on the ethical conduct of health research in prisons in LMICs.

Conclusions

The majority of the world's imprisoned populations are in LMICs, and they have considerable health needs. Research plays an important role in addressing these needs and in so doing, will contribute to the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals. With regards to health research, imprisoned people in LMICs are ‘left behind’; there is a lack of clear, prison-focused guidance and oversight to ensure high quality ethical health research so necessary in LMICs. There is an urgent need for prison health experts to work with health research ethics experts and custodial practitioners for procedural issues in the development of prison-specific ethical guidance for health research in LMICs aligned with international standards.

Keywords: Prison, Health research, Ethics, LMICs

Background

The health of people in prison and inequities in health research across the world are two distinct but linked issues of international public health importance. The global prison population continues to enlarge with approximately 11 million people in prison at any given time and an estimated 30 million people cycling through the system each year.1 Those in contact with the criminal justice and prison systems are likely to be the most marginalized and poorest members of society, and when imprisoned, may have their basic health needs neglected.2 Tackling health inequalities by addressing the health needs of these vulnerable populations is an essential component of contributing to the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), specifically to “reduce inequality within and among countries” and “leaving no one behind”. However, effective health care delivery in prisons, an important aspect of prison life, is particularly challenging, in part because of the huge burden of disease in this population, and insufficient government resource allocation to prison healthcare. People in prison have higher rates of substance abuse and dependence, psychiatric illness, infectious and non-communicable diseases, and experience of violence compared to the general population, and poorer pregnancy outcomes in women are observed.2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 Despite their many health concerns, people in prison remain significantly under-represented in health research, and this inequity mirrors global inequities in health research more broadly.9 , 10 Compared to high income countries such as Australia, Canada, the United Kingdom and the United States of America, there are few studies from countries in low and middle-income countries (LMICs) despite the fact that the prison population in LMICs is estimated to be 7.58 million, that is, 71% of the global prison population estimate.1 This deficit is important because research into the health of people in prison is crucial to improving this population's health, reducing health inequalities, creating a better understanding of their complex health needs, and in a gender and culturally sensitive manner, empowering and advocating for people in prison, and ultimately informing the development of prison health and social care policies and services, and wider prison reform and procedural changes.9 It is important to address this inequity and initiatives such as the WorldwidE Prison Health Research and Engagement Network (www.wephren.org) have been established with the specific aim of reducing global inequities in prison health research and building capacity in LMICs to do this.9 As initiatives to develop health research in prison in LMICs gain momentum in the coming years, and more LMIC academics are interested to engage in such research, it will be essential to ensure that any health research conducted is carried out to the highest standards and done so within a robust ethical framework.

Prison health research however has a controversial history, and it has been well documented that prisoners have been used unethically as populations of convenience.11 The ethical conduct of research in prisons is an important issue; as prisons are essentially a coercive environment, with power differentials and structural obstacles to voluntariness, pressures on people in prison as vulnerable populations to participate in research must be considered very carefully.12, 13, 14 There are international guidelines that govern the conduct of health research, such as The Declaration of Helsinki15 and the International Ethical Guidelines for Biomedical Research involving Human Subjects16 and the CIOMS guidelines for epidemiological studies.17 However, despite the growing body of literature regarding people in prison, few publications have provided guidance regarding the specific ethical complexities, challenges and strategies of conducting health research in prisons and other closed settings.11 , 18, 19, 20, 21, 22 There is broad acknowledgement that ‘All vulnerable groups and individuals should receive specifically considered protection’.15 Hence, principles of informed consent, autonomy, balancing the potential for direct benefit with the risk for harm, confidentiality and voluntary participation must be fundamental ingredients of ethical research in prisons.

Prison health research applications certainly undergo increased scrutiny from university ethics review and correctional services review boards in many countries in the world.23, 24, 25, 26 In high income countries, there has been a considerable increase in research in prisons, but this has not been mirrored in LMICs, creating yet another inequity in health research outputs between rich and poor countries. For example in the UK, where health research is closely regulated and there has been a significant increase in health research conducted in prison in recent decades, there are guidelines that must be adhered to and approvals sought from both health and prison service authorities prior to the conduct of any health research in prison. However, it is not clear what regulations are in place in LMICs where little prison health research has been conducted and where regulatory frameworks may not be so robust. There have been a number of initiatives to increase research and research capacity in LMICs (for example the Worldwide Prison Health Research and Engagement Network www.wephren.org).

Therefore, this study aims to examine the extent, range and nature of the published literature, prison policies and technical guidance relating to the ethical conduct of health research in prisons in LMICs. Our rationale for undertaking the review was that there is a huge gap in the evidence to inform effective health care and health promotion in prisons in LMICs. In parallel with efforts to increase research, it is important to ensure that any research conducted in prisons conforms to the highest ethical standards in this vulnerable population. We sought to establish what existing guidelines there were to inform good practice in LMICs. Frameworks and guidelines are key to monitoring ethical research practice within prisons, and these are very important in informing the development of standard operating guidelines for researchers’ practice, and ensuring researcher and gatekeeper accountability.

Methods

Scoping reviews are a form of research synthesis that maps and describes literature on a particular topic or research area and are increasingly used within health research to identify key concepts; types and sources of evidence to inform practice, policy-making and research, including gaps in research.27, 28, 29 We adhered to the five stages of the scoping review iterative process.29 This consisted of (1) identifying the research question, (2) identifying relevant studies, (3) study selection, (4) charting the data, and (5) collating, summarizing and content analysis of policies.

We established an author team with expertise in public health, prison health, research and health rights in LMICs. The research question for this scoping exercise was; ‘What is known in the literature about prison policies and applicable technical guidance around ethical health research conducted in contemporary prisons in LMICs?’ The term ‘prison’ was adopted as representing detention facilities housing both on-remand and convicted people. These settings included prisons, police holding cells, pretrial detention, closed youth institutions, and camps where drug users are forced into mandatory labour as means of rehabilitation.

We searched electronic databases and the websites of relevant organizationss, namely the World Health Organization (WHO), the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), the World Bank, the United Nations International Children Emergency Fund (UNICEF), the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) and the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC). We also searched the reference list of included articles.

The general search strategy for electronic databases using Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) terms is illustrated in Table 1 . These searches were conducted on 10 databases accessed through the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM) library and the University of Zimbabwe Library catalogs. The databases were EBSCO, EMBASE, Medline, CINAHL Plus, Global Health, PubMed, Cochrane, PsycINFO, PsychExtra and ScienceDirect. Publications of interest were restricted to the time period between 1999 and 2019.

Table 1.

Search concepts and synonym terms.

| Search Concepts | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethical Guidance |

Health Research |

Prisons |

Low- and middle-income countries |

||||

| Keywords | Subject Heading | Keywords | Subject Heading | Keywords | Subject Heading | Keywords | Subject Heading |

| Ethic∗OR OR Ethical conduct∗ |

exp Ethics/ | Health research∗ OR Medical research∗ OR Biomedical research∗ |

Biomedical Research/ OR Health Services Research/ |

Prisons∗OR Penitentiary∗ OR Detention∗ OR Corrections Facilities∗ OR Reinsertion∗ |

Prisons/ OR Penitentiary/ OR Detention/ OR Reinsertion/ |

(low∗adj3 Middle adj3 Countr∗). ti, ab OR Indonesia.ti, ab OR China.ti, ab. OR (list of every LMIC) |

Low- and Middle-income countries |

All articles examining any aspect of ethical conduct or guidance for health research in prisons in LMICs were included; these comprised editorials, commentaries, case reports and studies presenting empirical evidence. We included all age groups of people in prison, from juveniles to adults. There were no limits on language.

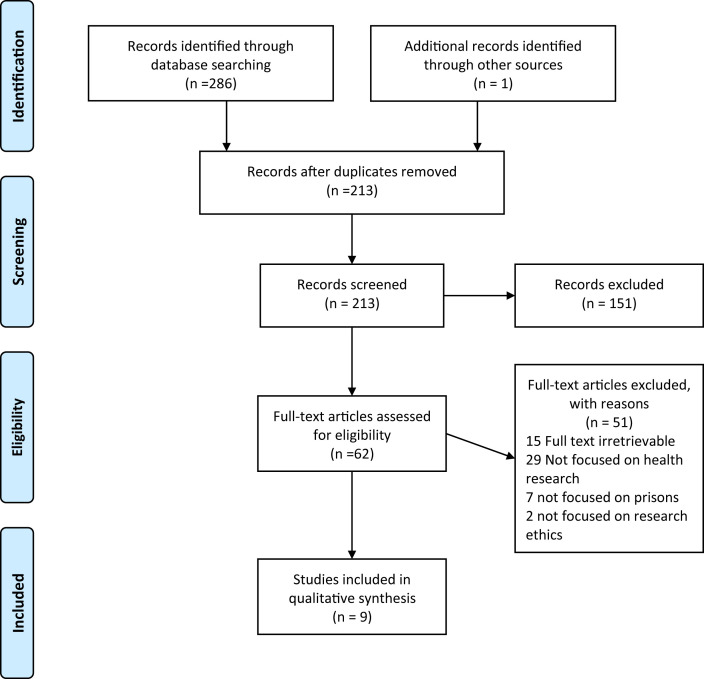

All records were managed using EndNote. The title and abstract of each record were initially screened by the second author, with all authors independently reviewing a portion of included and excluded records to determine inclusion status. All records warranting assessment of inclusion by the team were obtained for full text review. Where required, records were translated into English. A second screen of the full-text of each record was conducted in consultation. Studies were excluded at this stage if found not to meet the eligibility criteria. Fig. 1 summarizes this process.

Fig. 1.

Prisma flow diagram.

Included papers were charted, summarized and with the prison health research policy content analyzed, as per scoping review protocols. This involved the creation of a charting spreadsheet. Charting involved collecting and sorting key pieces of information from each record. The team conducted a trial charting exercise of five records as recommended by Levac and colleagues28 in order to maintain alignment with the scoping preview parameters. Disagreements around allocation of content were resolved through team discussion.

We also appraised the quality of the included articles. Given the diversity in the type of publications, different appraisal tools were used. The majority of included articles were expert opinion commentaries and we used Burrows & Walker's appraisal tool for these studies.30

Findings

Our search revealed nine records that examine in some way the ethical aspects of the conduct of health research in prisons in LMICs; eight of these were peer-reviewed publications31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38 and one being

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) toolkit.39 Despite the unique vulnerabilities of this group, we could find no comprehensive guidelines on the ethical conduct of health research in prisons in LMICs. The included articles largely comprised historical or contemporary case studies and commentaries (Table 2 ) of generally high quality (Table 3 ).

Table 2.

Summary of Included Records.

| Publication details | Aim | Location | Method of Study | Findings /Ethical Considerations | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peer Reviewed Journal Papers | |||||

| Patricia Arcega, Chiara Cabantac, Ronald Cruz31 Trends in health research ethics in the Philippines during the American Colonial Period (1898–1946) Developing World Bioeth. 2019; 00:1–6. |

To explore trends in health research ethics in the Philippines during the American colonial period (1898-1946). | Philippines | Review of research protocols and clinical trials involving vulnerable human subjects in the Philippines within the American colonization period (1898–1946). Quantitative and qualitative analysis of documents retrieved. |

The authors identified 288 documents and 36 of these related to research in prison. These prison studies documented the use of people in prison to test vaccines and to harvest tissues from for medical research. From 1898 to 1946, very few studies mentioned the observance of ethical guidelines or of the informed consent process. |

The authors attribute the fact that the consent process is not emphasised in studies and is mostly verbal, and the lack of clearly stated ethical guideline observance to the fact that the Nuremberg Code was not drafted until 1947, after the American colonization period in the Philippines had ended and the study period. |

| Virginia Dube32 Navigating the Libido Dominandi: Intricate Realities of Forensic Psychiatry Research Ethics in Zimbabwe J Psychiatry 2015, 18:1 |

To present the inherent ethical issues experienced in conducting forensic psychiatry research in special institutions Zimbabwe. | Zimbabwe | Case study. By examining a particular research study involving forensic psychiatric patients in a maximum-security prison, the author outlines an ethical ‘conundrum’ and considers in detail the ethical issues raised. |

Both general psychiatry and forensic psychiatry are driven by the Zimbabwe Mental Health Act of 1996, Zimbabwe Mental Health Regulations of 1999 and the Zimbabwe Mental Health Policy of 2004. Part 3 of the Act addresses forensic psychiatric patients with provisions of a port of entry for the rehabilitation as functional members of society and are admitted in what are called Special Institutions. These institutions are hospitals located within a maximum-security prison where they are subject to the Zimbabwe Prison Act and the Zimbabwe Prison (General) Regulations of 1996. This paper lays bare the many contradictions in such a system and highlights the near impossibility of conducting ethical research in such an environment: ‘The environment is such that the researcher can only congregate with a forensic psychiatric patient for interview provided the researcher has violated all the provisions of the Belmont Report of 1979 … This scenario then calls for collaboration as academia, practice, professional organizations and regulatory bodies to untangle this intricate ethical web.’ |

The conduct of ethical research into the health of forensic psychiatric patients is very difficult; in Zimbabwe such people are housed in the prison system. The conflicting priorities of the health and custodial systems create tensions and potentially insurmountable difficulties in the conduct of ethical research. |

| Charles E. Gessert & Catherine McCarty33 Research in Prisons: An Eye for Equity, Ophthalmic Epidemiology 2013, 20:1, 1-3 |

To consider the issues raised by a study on people in prison published by the journal (Tousignant B, Brian G, Venn B, et al. Optic neuropathy among a prison population in Papua New Guinea) | Papua New Guinea/ worldwide | Editorial/commentary The authors comment on a study on optic neuropathy in people in prison in Papua New Guinea |

Epidemiological research is important in documenting health problems, especially in underserved populations. It is particularly important in prisons where those imprisoned are ‘largely invisible’, hidden from the public eye, ‘not only by the walls and barbed wire, but by legal and administrative barriers.’ In some cases, governments do not want additional scrutiny of what occurs in prisons. However, it is important that research is conducted in these settings which have been neglected; people in prison should benefit from research. There must also be adequate protections to ensure they are not being exploited in the process. This is possible and Tousignant’s study is an example of good practice in prison research. | There are two competing concerns with research on people in prison:

|

| Lyons B34 History, Ethics and the Presidential Commission on Research in Guatemala Public Health Ethics 2014; 7(3) 211–224. |

To critique the historical enquiries of the Presidential Commission for the Study of Bioethical Issues which examined research carried out by the US Public Health Service in Guatemala between 1946 and 1948 | Guatemala | Commentary The author examines the findings of the ‘Guatemala Commission’, focusing on the prevailing culture of that time. |

Between 1945 & 1948, experiments were conducted for national security purposes, and therefore, it was believed by many scientists at that time that the conventional standards of medical ethics could be waived. There was a great public health need for such experiments because the prevalence of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) was such that the balance of risk and benefit justified the effort, however much it might compromise individual rights. At the time, understanding of the moral norms for research by scientists and others was evolving, and rules and principles were just beginning to be codified. The American Medical Association (AMA) Judicial Council had sided in 1946, with what would soon be the Nuremberg view that voluntary consent to participation in research is essential. Numerous international codes defined ethical standards for human experimentation, most notably the Nuremberg Code, did not command much attention and received very little press coverage. American researchers and physicians apparently found Nuremberg irrelevant to their own work. Key aspects of unethical practice in the studies in Guatemala on people in prison and other vulnerable groups included the lack of consent to participation and overriding utilitarian ethos (sending some men to be killed so that others may live). |

The Guatemala Commission ‘seems to have been deficient in its defining of standards, its review of historical data and in its analysis, or at least in its publication of this matter.’ It is important to understand historical misdemeanours/abuses in medical research in context. |

| Salaam AO & Brown J35 Ethical Dilemmas in Psychological Research with Vulnerable Groups in Africa. Ethics & Behavior 2013; 23:3, 167-178 |

The aim of the article is to identify key problems and offer a sensible way to conduct ethically sound applied psychological research among vulnerable or marginalized groups in Africa. | Nigeria | Case study The authors examine two research studies, identifying the key ethical challenges in their conduct, discussing these and how they were managed. |

Ethical clearance to conduct the study was obtained. Permission was sought from the National Drug Law Enforcement Agencies (NDLEA) in Nigeria in order to gain interview access to drug offenders in their custody. Voluntary participation & informed consent: During the questionnaire distribution, the participants were informed that their participation was voluntary and anonymous. The researcher explained the research’s purpose and aims and ensured that potential participants understood the study had no bearing on the outcome of their cases. Voluntary participation was stressed. In addition, they were told that they could get more information about the study at any time during the data collection; ask questions about the study even after they had completed and returned the questionnaires; leave out questions on the questionnaire they did not feel comfortable completing and the return of a completed questionnaire was their way of consenting to participation in the study, as is common practice elsewhere Risk: Exclusion criteria used included Inmates who might be unfit for an interview due to mental illness, high risk inmates such as those considered to be potentially violent or dangerous, or had previous records of planning/preparing/attempting to abscond or escape, and those deemed ineligible for other reasons at the discretion of the gaoler Anonymity, was ensured through ensuring that no names or other, marks likely to identify the participant appeared on the self-administered questionnaire. A high number of prison inmates who participated in the study were awaiting trial and were reluctant to sign the consent form because of the fear that it would be used to implicate them in their trial Reimbursement: payment or reimbursement in money or in kind is not a problem per se. However, if participants are from financially disadvantaged groups, this could be potentially construed as a form of coercive consent because of their monetary needs: is consent “freely given” if payment is involved? Ethical standards for participation in research demand that the participants should not be coerced and/or unduly influenced by financial, psychological, or other pressures. |

Contexts and cultures differ in terms of application of consent seeking procedures and use of rewards as a coercion tool in inducing participation in research more so when carrying out study with vulnerable institutions such as prisons. The challenges should not put researchers off, rather they should think through all aspects carefully. The authors state, ‘it is important to strike a balance between the safety of individuals (both of the researcher and the researched), cultural sensitivities, the socioeconomic realities, and optimal research designs.’ |

| Taborda J & Arboleda-Florez J36 Forensic psychiatry ethics: expert and clinical practices and research on prisoners Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2006;28(Supl II): S86-92 |

To review the most relevant ethical issues of the tripartite aspects on which forensic psychiatry is based: expert activity, treatment of the mentally ill in prisons, and research on prisoner subjects. | Brazil | Commentary | Relating to the ethical aspects of research conduct in prisons: Historically, there have been numerous historical abuses involving people in prison in the conduct of profoundly unethical research. This resulted in research in this environment stopping in the 1970s to prevent further abuses. This situation has now improved – people in prison should have the benefits of research. However, there should be ‘the strict observance of universal ethical principles in order to avoid imposing on this highly vulnerable population an onus greater than their sentence’. It is possible to achieve a balance between the need to conduct research in prison settings and the protection of the rights of imprisoned people, particularly if: -Incentives to participate are avoided. -Therapeutic research is distinguished from no-therapeutic research. -Pro-active role of ethics in research committees. The prison setting is unique but there is no prison specific guidance. This is problematic as ‘Merely invoking traditional variables, such as mental competence and the absence of coercion, is insufficient.’ Compensation for study participation which in the community might be regarded as minimal, can, in the prison setting be tantamount to the “buying” of subject compliance, for example the ‘unimaginably minimal recompense’ of better nutrition or transfer to another cell block. Argues for the need for the Ethical Research Committee (ERC) to be pro-active in monitoring study conduct, going beyond reviewing periodic study progress reports to making unannounced onsite inspections. |

Bearing in mind the vulnerability of prisoners, deprived of a portion of their autonomy and free will, as well as the fact that they live in an environment that fosters abuse, the ERC should carefully evaluate the following aspects:

|

| Tangwa GB37 Research with vulnerable human beings Acta Tropica 2009; 112S S16–S20 |

To stimulate practical reflection on the possible vulnerabilities of potential research subjects that researchers or investigators need to avoid exploiting rather than on an adequate theoretical treatment of the issue. | LMICs | Commentary | There has been an increase in HIC research on human beings in LMICs, particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). Many biomedical research studies in LMICs and particularly in SSA ‘have not been able convincingly to fulfil some of the requirements for ethical conduct of research on human beings, such as the informed consent condition, but have gone ahead, nevertheless.’ Describes the ‘Triple vulnerability’ of many in LMICs - vulnerable as members of economically disadvantaged groups; vulnerable as members of medically disadvantaged groups, bearing a heavy burden of neglected diseases; and vulnerable as members of specific groups such as people in prison. There are particular issues when conducting research in LMICs. For example: -the human rights structures which are central pillars of HIC societies are still to take firm roots in many LMICs.

|

‘Vulnerability in itself does not imply that no research whatsoever should be carried out with such categories of humans but only that it should be carried out only under very special conditions.’ |

| Zenilman J.39 The Guatemala Sexually Transmitted Disease Studies: What Happened Sexually Transmitted Disease. 2014;40(4):277-9 |

1. Provide a context for the Guatemala studies’ scientific rationale; 2. Provide a brief overview of the studies that were performed and the populations that were involved; 3. Review the correspondence between key individuals |

Guatemala | Commentary The author examines the archives of the study records and data of the USPHS studies on sexually transmitted infections in Guatemala in the 1940s. |

Examines the syphilis and other sexually transmitted disease studies conducted in 1946 to 1948 by the US Public Health Service in Guatemala. This data was revealed in 2010 after being hidden for more than 60 years. The studies used many groups who are considered to be vulnerable populations: people in prison, people with mental illness, people with limited literacy and cognition, and commercial sex workers. The key ethical principles that were flouted in these studies include:

|

The vulnerability of groups such as people in prison was not acknowledged by researchers at the time. Many ethical principles now accepted as key in the conduct of research were not adhered to. |

| International Guidance on conducting Research in Prisons | |||||

| UNODC HIV in prisons situation and needs assessment toolkit46 |

To provide information and guidance on conducting situation and needs assessments for the prevention and treatment of HIV infection and tuberculosis (TB) in prisons | Global | Guidance | Provides guidance on the conduct of ethical research in prisons relating to the management of blood borne viruses and TB infection:

|

Although not specific to SSA the presence of UNODC in some SSA country prisons and its focus on HIV&AIDS and TB prevention, treatment care and support including commissioning and funding research in these conditions dictate that all researchers have to abide by these principles when conducting research in prisons |

Table 3.

Summary of Quality.

| Study | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Checklist |

Dube32 Navigating the Libido Dominandi: Intricate Realities of Forensic Psychiatry Research Ethics in Zimbabwe) |

Gessert33 Research in Prisons: An Eye for Equity |

Lyons34 History, Ethics and the Presidential Commission on Research in Guatemala |

Salaam35 Ethical Dilemmas in Psychological Research with Vulnerable Groups in Africa |

Taborda36 Forensic psychiatry ethics: expert and clinical practices and research on prisoners |

Tangwa37 Research with vulnerable human beings |

Zenilman38 The Guatemala Sexually Transmitted Disease Studies: What Happened |

| Is the author an expert? | + | − | + | + | + | + | + |

| Is the opinion published within a credible source? | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Is their opinion evidence-based? | + | + | + | + | + | − | + |

| Are the authors personal statements clearly presented as such? | + | + | + | + | + | + | − |

| Is the opinion in response to a practical concern? | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Does the author provide arguments for and against the position? | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Does the author identify limitations of their statement? | + | + | + | + | + | − | − |

They outlined the many historical human rights breaches and abuses in prison research where the most fundamental of ethical guidelines were not respected. A number of authors also highlighted the fact that the subsequent institutional reaction to these abuses – that health research was no longer conducted in prisons – was also damaging, preventing people in prison from benefitting from research. Authors argued for ‘balance’ to ensure that people in prison are not excluded from participation in research that may be beneficial to them or their peers but are also protected from exploitation during the research process. Salaam and Brown identify how difficult this balance can be with prisons, a unique environment demanding careful consideration of each aspect of ethical research practice not a wholesale importation of practices seen in the community.35 They write, ‘it is important to strike a balance between the safety of individuals (both of the researcher and the researched), cultural sensitivities, the socio-economic realities, and optimal research designs.’ They reflect on such aspects of research practice as the use of incentives/compensation in research in prison, arguing that this needs to be considered very carefully because, given the unique prison environment, what might seem a small recompense in the community might be a huge incentive in prison. They question whether voluntary informed consent is ever truly possible in prison which is essentially a coercive environment.

Research in prisons in LMICs throws up further serious issues: Tangwa describes the ‘Triple vulnerability’ of many in LMICs - vulnerable because they are economically disadvantaged; vulnerable as members of medically disadvantaged groups, bearing a heavy burden of disease; and vulnerable because they are imprisoned.37 Taborda et al. suggest that ethical review committees need to consider these issues carefully along with the suitability of the specific researchers (their experience, qualifications, conflicts of interest) and proactively monitor studies in the prison environment, making a case for unannounced visits in prisons by ethical committee representatives.36 They argue cogently for prison-specific guidance for the conduct of ethical research: this unique environment with its vulnerable participants merits a different approach.

Further to this, there are ethical dilemmas pertaining to the control of prison authorities over research findings, whereby inadvertent coercion takes place, and those partaking are selected specifically and prepped on what to say to researchers on the day of data collection. Often this is followed by instances whereby findings not reflecting positively on the prison system are blocked from publication and dissemination by authorities. Actual findings are impeded from communication to those who have the ability to intervene and improve conditions, stifles the voices of people in prison, and ultimately disincentivises LMIC academics from attempting to conduct prison health research.

Discussion

Successful prison research is underpinned by a collaborative approach and strict adherence to rigorous research standards,24 , 40 regarding people in prison as a vulnerable group.17 Given the distinct sociocultural aspects, the often ‘triple’ vulnerabilities of imprisoned people in many LMICs (poor, heavy burden of ill health, incarcerated, women/minority grouping) and the prioritization of punishment as the dominant discourse in many LMICs, we sought to investigate what existing guidelines there were to inform good research practice. The scoping study represents a unique and first step toward gathering and mapping available literature on prison policies and technical guidance around ethical health research conducted in prisons in LMICs. It is disappointing to find that despite the many vulnerabilities of this group, we could find no comprehensive guidelines on the ethical conduct of health research in prisons in LMICs.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first comprehensive review which has examined the extent, range and nature of the published literature, prison policies and technical guidance relating to the ethical conduct of health research in prisons in LMICs. The review was thorough in terms of adhering to the scoping review method,27, 28, 29 and its multilayered strategies to locate information but yielded a small number of records (n = 9) which examined the ethical considerations, protocols and polices for oversight for conducting ethical prison health research in these countries. When charted thematically, the historical dimension was included, and illustrates the progression in frameworks and regulations governing the use of human subjects in research including prisons. Several of these records (n = 4) took a historical perspective, detailing the misdemeanors of the past, many of which had profound adverse consequences for vulnerable groups who were subjected to unethical research practices. These studies serve to reinforce the importance of robust frameworks which are clearly regulated and universally applied. The included studies scored well with respect to quality according to Burrows and Walker's criteria.30 However, it should be noted that most were case studies/commentaries/editorials, generally considered to provide a poor level of evidence. Furthermore, the included studies examined issues in-depth in six countries only (Brazil, Guatemala, Nigeria, Papua New Guinea, Philippines and Zimbabwe) although authors did consider issues relating to LMICs more generally. We note that aside of development status (for example in historic periods when the USA was in power in the Philippines/Guatemala), the cultural and contextual sensitivities around prison research remain in LMICs, and underscore the need to understand the context, the political dimensions, and the need for clear, prison-focused guidance and oversight to ensure high quality ethical health research and protection of participants so necessary in LMICs. Notwithstanding this diversity in discipline, and publication type, the overall finding remains the same, that there is a lack of clear, prison-focused guidance and oversight to ensure high quality ethical health research so necessary in LMICs.

Despite our rigorous search approach, only eight peer-reviewed publications (five commentaries, two case studies, and one review) and one toolkit emerged. We analyzed these thematically as per the scoping review method,27, 28, 29 and we recognize that the included records represent a broad and diverse range of different disciplines, and publication type (review, case study, commentary, toolkit). Many of the included documents, whether taking a historical or contemporary perspective, emphasized the importance of access based on ethical clearance, permission with the relevant and senior correctional authorities, exclusion criteria where inmates might be considered high risk, ethical premises based on full explanation of the research aims, benefits and risks to participants, assurances around voluntary and anonymous participation with no bearing on the outcome of pending cases, and inmate ability to ask questions throughout and after the study. Health research should be conducted in an ethical manner, respecting the dignity, safety and rights of participants, recognizingthe safety, security and responsibilities of researchers, and the importance of ensuring that the basic human rights of individuals are not violated in the course of the research, and that no false expectations are raised. The documents highlighted the importance of voluntary participation but referred to the complexities around perceived coercion pertaining to selection of suitable participants, and the coercion of academics engaged in this research. This may be because the autonomy of imprisoned people is limited in many ways but it is important for them to understand that their participation in research is a decision they can make freely. This was also highlighted in the 2009 International Ethical Guidelines for Epidemiological Studies which specifically but briefly mentioned the lack of autonomy of prisoners.17 However, the included documents also considered the issues raised by payment for participation of this marginalized and vulnerable group.

Hence, our scoping review underscores the justification for contextually appropriate ethical frameworks in LMICs distinct from that of a non-LMIC country. Prison health research is traditionally low priority and there is a lack of engagement in routine prison health enquiry and academic prison health research in many LMICs, due in part due to the focus in these countries on security and punishment, prejudices and the devaluation of prisoners as citizens, the lack of political commitment and domestic resources to improve health standards and the presence of significant barriers to access to those outside the system seeking to investigate.10 There are potentially a myriad of substantial ethical concerns in terms of prison officials influencing research data, structural obstacles to voluntariness, lack of voluntariness and the coercion of imprisoned people and prison staff, and embargoing of academic publications at country levels. This creates a dearth of published literature which directly addresses the assurance of health rights of both imprisoned people (and prison staff) coupled with a distinct lack of clear prison focused guidance and oversight in line with international standards to ensure ethical and robust prison health research.

Growth of prison health research activity in LMICs is therefore dependent upon an adequate, culturally sensitive and contextually appropriate ethical framework to protect imprisoned people and prison staff as research participants. Research efforts underpinned by robust ethical guidelines and frameworks are an imperative to generate evidence to inform rights-based programming and policy formulation to improve imprisoned people's welfare in LMICs. Ethical guidelines appropriate to the LMIC context, and aligned with international guidelines will safeguard the rights of research participants in prisons. Health research in these prisons is important to inform the development of appropriate and effective evidence based health education and promotion interventions, healthcare services both within prison settings, and also connecting to the continuum of care for those on release.41 , 42 It is clear that people transitioning from prison to the community are at particularly high risk for adverse health outcomes.43, 44, 45 However, if research interest and activity is to expand here, it is important to establish what ethical safeguards should be in place to protect this vulnerable population, and support those academics engaging in this challenging form of health research. The review whilst yielding a low number of records, underscores that health-related research with prison populations in LMICs is important but that health-related research in these settings is scant; growth of health-related research is dependent upon an adequate ethical framework to protect prisoners as research participants, and encourage greater academic interest in this neglected health environment. There is little published literature or grey literature that directly addresses prisoner protections in health research and that these protections need to be put into place. Ethics bodies in different LMICs do exist to regulate research in the respective countries and researchers within these respective countries wishing to undertake research in correctional facilities (prisons and other closed settings) would follow the ethical requirements as stipulated by the ethical review bodies. We assume that health researchers would obtain relevant institutional ethical clearance prior to gaining access to prisons and potential participants. It is vital for prisons and correctional services and other relevant bodies adhere to ethical protocols, based on international guidelines of ethical research conduct. Countries need to address this deficit by developing a regulatory framework for the ethical conduct of research involving imprisoned persons in line with international guidelines as prerequisite for permission of such research. Further investigation of prison policies is warranted in each country to ensure standards are met, and in approving research access to prison populations.

Lastly, the ‘bridge of prison health and public health’ cannot be underestimated. Prisons by their nature have long been associated with rapid transmission of disease, become high risk breeding environments of transmission, vehicles and bridge of onward transmission in the general population. Often the connectivity between prison and community occurs via the prison staff, their families, visitors to the prisons and the revolving door of incarceration. Those imprisoned generally suffer high burden of disease, great health disparity and poor health outcomes. It is through research underpinned by ethical guidelines and frameworks that evidence can be generated in LMICs to protect researchers, and research participants, inform interventions, encourage positive prison health reform, gender sensitive programming, and robust contagious and infectious disease prevention, ultimately resulting in protection of public health. This is now an imperative given the COVID-19 crisis, and also the impact of Multi-drug resistant tuberculosis (MDRTB)/Extensively drug resistant tuberculosis (EDRTB). Continued neglect of prison health research in the absence of robust contextually appropriate ethical frameworks for health research in prisons therefore has huge implications on mortality, morbidity, and disease prevention, the right to health of imprisoned people and right to a safe healthy working environment for those who work in prisons, and overall impact on general population health. Further, clear ethical principles and greater academic activity within prisons in LMICs can incur great impact in raising awareness, political sensitization and human rights advocacy.

Conclusion

The majority of the world's imprisoned population, almost eight million people, are in LMICs. Prison populations have considerable unmet health needs and ethical health research can play an important role in addressing these needs and in so doing, countries will be contributing to the achievement of the SDGs. However, it is clear that with regards to health research, people in prison in LMICs are ‘left behind’ and there remains a need for high quality, ethical and robust health research. Ensuring that people in prison have similar access to participate in research as those in the community should be regarded as an ethical imperative by health researchers, practitioners, and policymakers.11 Tangwa's assertion of the ‘triple vulnerability’ of people in prison, emphasizes the need for such research to be conducted to the highest ethical standards.37 Our study highlights that currently there is a lack of clear, prison-focused guidance and oversight to ensure this in LMICs and underscores the urgent need for prison health experts to work with health research ethics experts and custodial practitioners for procedural issues in the development of prison-specific ethical guidance for health research in LMICs aligned with international standards. This will encourage greater academic interest, engagement and commitment to conducting health search in prison environments, and in so doing inform policy and practice reform, and the improvement of health standards for people in prison.

Author statements

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was not required as this is a scoping review of extant literature.

Funding

RMG and MCVH were funded by the Medical Research Council Grant Ref: MC_PC_MR/R024278/1.

Competing interests

We have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Walmsley R. 12th ed. Institute for Criminal Policy Research, Birkbeck, University of London; 2019. (World prison population list). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Penal Reform International . Penal Reform International; London: 2018. Global prison trends 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fazel S., Seewald K. Severe mental illness in 33,588 prisoners worldwide: systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2012;200(5):364–373. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.096370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fazel S., Yoon I.A., Hayes A.J. Substance use disorders in prisoners: an updated systematic review and meta-regression analysis in recently incarcerated men and women. Addiction. 2017;112(10):1725–1739. doi: 10.1111/add.13877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dolan K., Wirtz A.L., Moazen B., Ndeffo-Mbah M., Galvani A., Kinner S.A., et al. Global burden of HIV, viral hepatitis, and tuberculosis in prisoners and detainees. Lancet. 2016;388(10049):1089–1102. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30466-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spaulding A.C., Eldridge G.D., Chico C.E., Morisseau N., Drobeniuc A., Fils-Aime R., et al. Smoking in correctional settings worldwide: prevalence, bans, and interventions. Epidemiol Rev. 2018 Jun 1;40(1):82–95. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxy005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Herbert K., Plugge E., Foster C., Doll H. Prevalence of risk factors for non-communicable diseases in prison populations worldwide: a systematic review. Lancet. 2012;379(9830):1975–1982. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60319-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bard E., Knight M., Plugge E. Perinatal health care services for imprisoned pregnant women and associated outcomes: a systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16(1):285. doi: 10.1186/s12884-016-1080-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Plugge E., Stürup-Toft S., O'Moore É J., Møller L. WEPHREN: a global prison health research network. Int J Prison Health. 2017 Jun 12;13(2):65–67. doi: 10.1108/IJPH-03-2017-0014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mhlanga-Gunda R., Motsomi-Moshoeshoe N., Plugge E., Van Hout M.C. Challenges in ensuring robust research and reporting of health outcomes in sub-Saharan African prisons. Lancet Glob Health. 2020 Jan;8(1):e25–e26. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30455-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ahalt C., Haney C., Kinner S., Williams B. Balancing the rights to protection and participation: a call for expanded access to ethically conducted correctional health research. J Gen Intern Med. 2018 May;33(5):764–768. doi: 10.1007/s11606-018-4318-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McDermott B.E. Coercion in research: are prisoners the only vulnerable population? J Am Acad Psych Law. 2013;41(1):8–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dalen K., Øen Jones L. Ethical monitoring: conducting research in a prison setting. Res Ethics. 2010;6(1):10–16. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moser D.J., Arndt S., Kanz J.E., Benjamin M.L., Bayless J.D., Reese R.L., et al. Coercion and informed consent in research involving prisoners. Compr Psychiatr. 2004 Jan-Feb;45(1):1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2003.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Medical Association . WMA; 2018. Declaration of Helsinki - ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Council for International Organizations of Medical. Sciences (CIOMS) 4th ed. CIOMS; Geneva: 2016. (International ethical guidelines for health-related research involving humans). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS) CIOMS; Geneva: 2009. International ethical guidelines for epidemiological studies. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Byrne M.W. Conducting research as a visiting scientist in a women's prison. J Prof Nurs. 2005 Jul-Aug;21(4):223–230. doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fox K., Zambrana K., Lane J. Multivariate comparison of male and female adolescent substance abusers with accompanying legal problems. J Crim Justice Educ JCJE. 2011;22(2):304–327. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2011.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Innes C.A., Everett R.S. Factors and conditions influencing the use of research by the criminal justice system. Western Criminology. 2008;9(1):49–58. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Quina K., Garis A.V., Stevenson J., Garrido M., Brown J., Richman R., et al. Through the bullet-proof glass: conducting research in prison settings. J Trauma & Dissociation. 2007;8(2):123–139. doi: 10.1300/J229v08n02_08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wakai S., Shelton D., Trestman R.L., Kesten K. Conducting research in corrections: challenges and solutions. Behav Sci Law. 2009;27(5):742–752. doi: 10.1002/bsl.894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hammett T.M., Nevelow Dubler N. Clinical and epidemiologic research on HIV infection and AIDS among correctional inmates: regulations, ethics, and procedures clinical and epidemiologic research on HIV infection and AIDS among correctional inmates. Eval Rev. 2016;14(5):482–501. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shaw D.M., Wangmo T., Elger B.S. Conducting ethics research in prison: why, who, and what? J bioeth Inq. 2014;11(3):275–278. doi: 10.1007/s11673-014-9559-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pont J. Ethics in research involving prisoners. Int J Prison Health. 2008;4(4):184–197. doi: 10.1080/17449200802473107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eldridge G.D., Johnson M.E., Brems C., Corey S. Ethical challenges in conducting psychiatric or mental health research in correctional settings. AJOB Primary Research. 2011;2(4):42–51. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Daudt H.M.L., van Mossel C., Scott S.J. Enhancing the scoping study methodology: a large, inter-professional team's experience with Arksey and O'Malley's framework. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013;13:48. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-13-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Levac D., Colquhoun H., O'Brien K.K. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5:69. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arksey H., O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Burrows E.W.S. Developing a critiquing tool for expert opinion. Working Papers in Health Sciences. 2013;1(3):1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arcega P., Cabantac C., Cruz R. Trends in health research ethics in the Philippines during the American Colonial Period (1898-1946) Develop World Bioeth. 2019;19:1–6. doi: 10.1111/dewb.12227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dube V. Navigating the libido dominandi: intricate realities of forensic psychiatry research ethics in Zimbabwe. J Psychiatry.18(1):209-215.

- 33.Gessert C., McCarty C. Research in prisons: an eye for equity. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2013;20(1) doi: 10.3109/09286586.2012.742553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lyons B. History, ethics and the presidential commission on research in Guatemala. Publ Health Ethics. 2014;7(3):211–224. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Salaam A., Brown J. Ethical dilemmas in psychological research with vulnerable groups in africa. Ethics Behav. 2013;23(3):167–178. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Taborda J., Arboleda-Flórez J. Forensic psychiatry ethics: expert and clinical practices and research on prisoners. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2006;28:S86–S92. doi: 10.1590/s1516-44462006000600007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tangwa G.B. Research with vulnerable human beings. Acta Trop. 2009;112s:S16–S20. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2009.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zenilman J. The Guatemala sexually transmitted disease studies: what happened. Sex Transm Dis. 2014;40(4):277–279. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31828abc1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) UNODC; Vienna: 2010. HIV in prisons Situation and needs assessment toolkit. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cisloa A. Challenges and solutions for conducting research in correctional settings: the U.S. experience. Int J Law Psychiatr. 2013;36:304–310. doi: 10.1016/j.ijlp.2013.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Van Hout M.C., Mhlanga-Gunda R. Contemporary women prisoners health experiences, unique prison health care needs and health care outcomes in sub Saharan Africa: a scoping review of extant literature. BMC Int Health Hum Right. 2018;18(1):31. doi: 10.1186/s12914-018-0170-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Van Hout M.C., Mhlanga-Gunda R. 'Mankind owes to the child the best that it has to give': prison conditions and the health situation and rights of children incarcerated with their mothers in sub-Saharan African prisons. BMC Int Health Hum Right. 2019 Mar 5;19(1):13. doi: 10.1186/s12914-019-0194-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Crowley D., Van Hout M.C., Lambert J.S., Kelly E., Murphy C., Cullen W. Barriers and facilitators to hepatitis C (HCV) screening and treatment-a description of prisoners' perspective. Harm Reduct J. 2018;15(1):62. doi: 10.1186/s12954-018-0269-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Baillargeon J., Penn J.V., Knight K., Harzke A.J., Baillargeon G., Becker E.A. Risk of reincarceration among prisoners with co-occurring severe mental illness and substance use disorders. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2010;37(4):367–374. doi: 10.1007/s10488-009-0252-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fox A.D., Anderson M.R., Bartlett G., Valverde J., Starrels J.L., Cunningham C.O. Health outcomes and retention in care following release from prison for patients of an urban post-incarceration transitions clinic. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2014;25(3):1139–1152. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2014.0139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/frontpage/2010/July/unodclaunches-toolkit-forhiv-assessment-inprisons.html.