Key Points

Question

Are there common characteristics among female surgical chairs that are associated with their professional success?

Findings

In this qualitative study including 20 female surgical chairs, strong leadership personality traits combined with adaptability enabled this minority to reach the highest strata of achievement in academic surgery despite challenging external factors.

Meaning

The findings of this study suggest that future attention toward encouraging intrinsic strengths, fostering environments that bolster career development, emphasizing adaptability, and work-system redesign may support increasing diversity in surgical leadership roles.

Abstract

Importance

Only 7% of US surgical department chairs are occupied by women. While the proportion of women in the surgical workforce continues to increase, women remain significantly underrepresented across leadership roles within surgery.

Objective

To identify commonality among female surgical chairs with attention toward moderators that appear to have contributed to their professional success.

Design, Setting, and Participants

A grounded theory qualitative study was conducted in academic surgical departments within the US. Participants included current and emeritus female chairs of American academic surgical departments. The study was conducted between December 1, 2018, and March 31, 2019. An eligible cohort of 26 women was identified.

Interventions and Exposures

Participants completed semistructured telephone interviews conducted with an interview guide.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Common themes associated with career success.

Results

Of the eligible cohort of 26 women, 20 individuals (77%) participated. Sixteen participants were serving as active department chairs and 4 were former department chairs. Mean (SD) length of time served in the chair position, either active or former, was calculated at 5.6 (2.6) years. Two major themes were identified. First, internal factors emerged prominently. Personality traits, including confidence, resilience, and selflessness, were shared among participants. Adaptability was described as a major facilitator to career success. Second, participants described 2 subtypes of external factors, overt and subtle, each of which included barriers and bolsters to career development. Overt support from mentors of both sexes was described as contributing to success. Subtle factors, such as gender norms, on institutional and cultural levels, affected behavior by creating environments that supported or detracted from career advancement.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this study, participants described both internal and external factors that have been associated with their advancement into leadership roles. Future attention toward encouraging intrinsic strengths, fostering environments that bolster career development, and emphasizing adaptability, along with work-system redesign, may be key components to career success and advancing diversity in surgical leadership roles.

This quality improvement study examines the common factors associated with the success of women serving as surgical department chairs.

Introduction

A persistent gender gap remains among leadership positions in US academic surgical departments despite increasing equality in trainee gender demographics. In 2017, 50.7% of first-year medical students were women—a historic majority1—and women comprised 40%2 of general surgical residency positions. Contemporary data describe the percentage of female faculty surgeons at US academic medical institutions as 26%,3 with proportions decreasing as academic ranking increased (29% of assistant professors, 21% of associate professors, and 12% of full professors).3 Currently, 28 of 354 chairs of academic surgical departments across the US are held by women.4,5 In general surgery, gender parity, especially in leadership roles, has yet to be achieved.3,6,7,8,9

Barriers to the professional advancement of female surgeons include lack of adequate mentorship and sponsorship, stress related to work-life balance, gender bias, sexual harassment, structural challenges, and job dissatisfaction.10,11,12,13 These factors have additionally been associated with increased risk of professional burnout in female surgeons.12,14,15 While factors supportive of female professional advancement have been described in the business realm, there is a lack of investigation into factors associated with success in the careers of female surgeons.16

To identify factors supporting advancement and achievement in female surgeons, we examined common themes among the professional ascension of female surgical department chairs. Through qualitative analysis of interviews with this group of surgeons, we studied factors possibly affecting their career trajectories, with particular attention toward positive moderators.

Methods

Design

We used a purposive criterion-based sampling technique to identify past or present female chairs of academic surgical departments.17 The Association of Women Surgeons’ website maintains an up-to-date listing of past and present female surgical academic department chairs that was used for reference in cohort development.7 Eligible participants were recruited via email with a single reminder email if there was no initial response. If candidates remained unresponsive, no further contact was attempted. Informed consent was obtained verbally at the commencement of each interview encounter. Consent included permission to use the quotations in publication. Participants did not receive financial compensation. The study was approved by the Partners Institutional Review Board. This study followed the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) reporting guideline.

We designed a semistructured interview template of 11 open-ended questions based on literature review and research team consensus (eTable 1 in the Supplement). Participants were asked about their early career decision-making, positive and negative factors in their own career success, and perceptions of gender differences in career advancement within the field of surgery. While the interview template was designed to guide conversation, flow of discussion was not exclusively limited or restricted by these topics. Throughout the data-gathering phase, questions were refined in accordance with group consensus as concurrent iterative analysis was conducted. Interviews were conducted between December 1, 2018, and March 31, 2019, via telephone in a one-on-one format by a single research team member (A.B.C.). All interviews were audio recorded on a secure device and were transcribed verbatim. Field notes and memos were recorded by hand by the interviewer during and after each interview and were incorporated as data for analysis.

Following preliminary data analysis, study participants were asked to participate in a member-checking process to establish credibility of the findings (eTable 2 in the Supplement). An email containing emergent themes was sent to all participants. Participants were asked to indicate their agreement with the findings and were offered the opportunity to comment in writing. Member-checking results were incorporated into our final analysis.

Researchers

Our research team is composed of public health researchers at varying levels of training affiliated with either Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts, or with the University of Massachusetts Memorial Hospital in Worcester, Massachusetts. Two of us are attending surgeons (J.S.D. and N.M.) and 4 are surgical residents (A.B.C., P.W.L., S.S.H., and A.C.F.). The backgrounds of our research team’s members were disclosed to each participant before the interviews for the purpose of transparency.

Data Analysis

Three members of our research team (A.B.C., P.W.L., and S.S.H.) inductively coded all transcripts. Each research team member first independently reviewed the transcripts, inductively identifying prominent codes. A preliminary codebook was then developed on group discussion. Codes were iteratively applied to transcripts with interim reconciliation of coding with modification and addition of codes reconciled through consensus. This process was repeated until thematic saturation was reached and a final codebook was developed. Initial transcripts were reviewed and recoded in accordance with the final codebook. Interviews were continued until thematic saturation was reached. Coded data were entered into software for data management (Atlas.ti, version 8.0 [Atlas.ti]) and were analyzed within and across interview transcripts to identify emergent themes.

Results

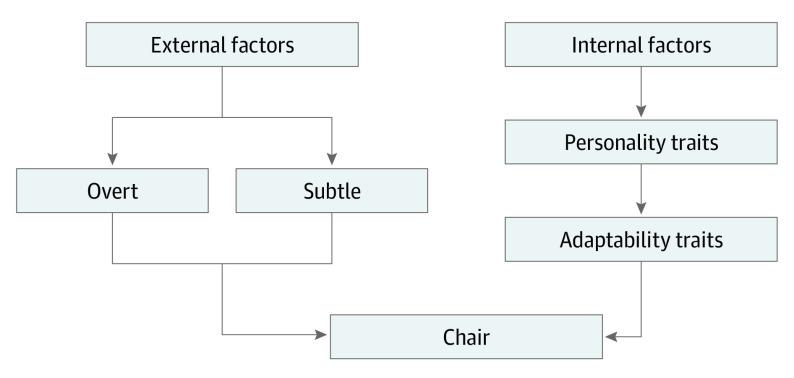

Of an eligible cohort of 26 women, 20 surgical chairs (77%) participated in this study. Of the 6 eligible surgeons who did not participate, responses were not received from 5 surgeons and 1 surgeon declined participation for unspecified reasons. At the time of study enrollment, 16 participants were serving as active department chairs and 4 were former department chairs. Mean (SD) length of time served in the chair position, either active or former, was calculated at 5.6 (2.6) years. Interview length ranged from 22 to 67 minutes. Eleven of 20 participants (55%) responded to the member-checking survey. Our analysis allowed for the emergence of 2 major thematic categories that were described as being associated with participants’ professional success: internal factors and external factors (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Factors in Female Chair’s Careers.

Overt internal factors included gender-based discrimination and stereotyping. Subtle internal factors included culturally pervasive unconscious biases. Internal personality trait factors included confidence, resilience, and selflessness.

Internal Factors

Participants consistently described fundamental personality traits that positively contributed to their professional successes (Table 1). These participants cited traits such as confidence, determination, perseverance, and resilience as shaping their ability to thrive. Participants also voiced dedication to the advancement and well-being of those with whose leadership they are charged. This theme of servant leadership emerged as a prominent source of motivation. “If I am an excellent chairwoman, it’s because I am curious, I am driven, and I want the best for the people who I serve,” said participant 7. “I am always learning, reading, listening, and am curious about how things work and am trying to make sure that they do work well so that I can do the work of making things better for others.”

Table 1. Internal Factors in the Career Trajectories of Female Surgical Chairs.

| Personality trait | Example quotation |

|---|---|

| Confidence | “Confidence, I think, is key. I have confidence that, if I put my effort in, I will get there and I will achieve my goal.” Participant 8 |

| “I believe in myself even if others do not.” Participant 9 | |

| Determination | “I was determined to make a difference in my environment. I had my mind set on it.” Participant 3 |

| Perseverance | “I believe in perseverance. I don’t take no for an answer.” Participant 9 |

| Resilience | “There are things that happen that are discouraging, you know, that happens in every person’s life and past, but I don’t dwell on those things. It might upset me for day or two, but then I put it out of my mind and it’s gone.” Participant 15 |

| Servant leadership | “I get great joy out of helping people. I really do. I want to fix things for other people. I want to support other people’s careers, to give them the support and mentorship that they need. It is just incredibly gratifying being able to develop new clinical programs to impact.” Participant 13 |

The cohort described a high degree of personal adaptability throughout their careers (Table 2). This ability to adjust and persevere through adversity was cited as a positive factor in career advancement. Participants described minor behavior modifications that never compromised their values to gain professional edge. Participant 3: “So I went the extra step of dressing up and people finally recognized me as a doctor. So is it fair that my male co-resident could just wear scrubs? No, it’s not fair. But I needed to focus on my goal.” Participants furthermore discussed an ability to efficiently prioritize and remain focused on task completion without becoming hindered by distraction. This attitude was cited as a source of positive recognition. Participant 4: “And so sometimes what happens is when other people cannot get it done, or if they flat-out fail, you are the last person in the room. The duty falls to you to fix whatever is not right and so you do it. People notice this.”

Table 2. Adaptability in Female Surgical Chairs.

| Adaptability subtheme | Example quotation |

|---|---|

| General adaptability | “You roll up your sleeves and you do it. If you do that enough, people then start tapping you to go into these other roles.” Participant 4 |

| Workaround strategies | “I don’t think that I ever tackled that head on. It did not seem worth my time. I just found a work-around and found another avenue to rise to the top.” Participant 19 |

| “I delegate. I knew I needed to surround myself with those who knew things that I did not so that I could supplement my knowledge.” Participant 18 | |

| “Ask for help. Outsource. You need to be able to spend time on the priorities of your life and not time on the things that don’t matter. Establishing those priorities and deciding where you want to spend your time is very critical for people in surgery, and particularly for women who oftentimes have more demands outside of the hospital.” Participant 11 |

Participants described themselves as holding several responsibilities, including those pertaining to administrative, clinical, and personal tasks. Difficulties were acknowledged within each realm of responsibility and also in regard to fulfilling tasks across responsibility types with limited available time. The cohort spoke of a strong aptitude for creativity, delegation, and prioritization in their daily lives. These work-around strategies allowed for simultaneous jobs to be completed and for participants’ energy to be focused productively. “Adversity? Sure I’ve encountered it,” mused participant 19. “But I just worked around it. I think we’re all masters of workaround. I do not waste my time on pursuits that are unfruitful.” An association between the concept of work-around strategies and discussion regarding pregnancy and childbearing further emerged. Participant 1: “Women surgeons, both trainees and faculty, are frequently pregnant and we work around it. In training, a woman who was a year behind me was told that if she got pregnant, she would be fired. Training policies do not adequately account for the needs of surgeons in their childbearing years. I’ve helped to create all kinds of schedules for my surgeons so that they could do what they needed to.”

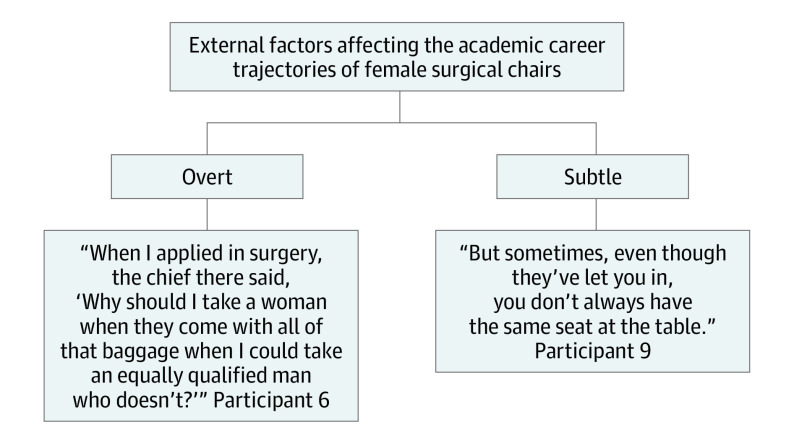

External Factors

Two major forms of external and environmental factors were described as being meaningful: those that were overt and those that were subtle or less explicit (Figure 2). Publicly discussed support and, conversely, discouragement, were noted as pronounced factors in the participants’ professional experience.

Figure 2. External Factors in the Career Trajectories of Female Surgical Chairs.

Overt internal factors included gender-based discrimination and stereotyping. Subtle internal factors included culturally pervasive unconscious biases.

Many interviewees discussed early encouragement in the home or school setting as helping to foster their personal confidence. “My grandfather looked at me and actually told me, ‘they are going to tell you that you cannot do stuff, and you should tell them that you can,’” recalled participant 12.

The importance of professional mentorship and sponsorship emerged prominently. The relative lack of clear female role models through our cohort’s training and early career development was described. “Literally from the time I had started medical school until my third year as a surgical resident, I never saw a female role model, ” said participant 2. While same-gender mentorship was discussed as favorable, it was generally acknowledged that the gender of strong mentors did not affect our cohort as much as did the presence of consistent and public support. “He did not care if I was White or Black or a boy or a girl,” said participant 4 as she described her male mentor. “What he cared about was that I could do the work and whether I could take care of the patients. He told others about me and promoted me because he felt that I deserved it.”

Experiences with overt gender-based discrimination and stereotyping were also reported along the entirety of the interviewees’ career trajectories. “One of the programs that I was applying to for residency told me that they didn’t accept women, so I needn’t apply, ” said participant 1. Participant 18 recalled her experience of seeking a chair-level position: “I had a guy offer me a chair job, only to take back a few weeks later because he said, ‘I don’t think I could support it.’ Those were major institutions and everyone knew.” The cohort was inspired and motivated when senior surgeons publicly voiced intolerance of such overt bias. Participant 10: “When he spoke out against what that man had done, I was in shock. I thought, he just made the right decision. It’s possible to do the right thing and to make hard decisions and support the people who you should be supporting. He inspired my bravery.”

Environmental factors that tended to be comparatively indirect, although culturally pervasive, were also described as affecting the interviewees. Underlying cultural encouragement of workforce diversity was described as fostering confidence. “It’s not about the number of women that you have in a department,” participant 16 said. “It’s about whether or not women are empowered to succeed.”

Implicit gender biases were commonly described. “Along this journey, it has struck me that the overt stuff may be going away, but there is still a lot of inherent bias and kind of covert things that happen that make it hard,” said participant 11. “I find that unsettling. Women are hired for what they have done. Men are hired for their potential. It only adds up from there. I see people become so frustrated and discouraged.” “I think that there is a lot of discrimination, though most people don’t even know that they are doing it,” said participant 18. “You know, it’s that microaggression. People don’t even know that they have these biases. There is tremendous jealousy and competition for these amazing positions, and some people blink and think, ‘I don’t like her for that,’ but they don’t even know why.”

Discussion

This cohort of women surgeons described common factors supporting their career advancement. Internal factors, or personality traits, were discussed as being fundamental components to this cohort’s professional success. The cohort also expressed a strong degree of personal adaptability, which allowed for adjustment and positive response to their surrounding environments. In turn, external factors were described as either being encouraging or discouraging. The participants discussed overt external factors, particularly negative, as becoming increasingly less common. Subtle external factors, sometimes pertaining to unconscious biases, were noted as culturally pervasive and were believed to be pertinent barriers to the professional advancement of female surgeons.

While each theme is independently rich, thematic interplay likely affected the success of this cohort. These women exhibited personality traits that appear to be associated with effective leadership profiles.18,19 While there is likely an innate component, it is notable that the cohort described encouragement of these traits stemming from childhood—a pattern described as promotional to leadership success.19,20 The adaptability described by this cohort, combined with their personality traits, appeared to render them well equipped to overcome external adversity. Despite overt and pervasive discord, this cohort of surgeons was driven by their skillsets and personality traits toward the highest leadership positions.

The findings of this work support ongoing discussions fostered by prominent governing bodies in the surgical field. In 2018, the American College of Surgeons Governors Survey, conducted in a male-dominant cohort, revealed that while nearly one-third of those surveyed believed that gender inequality was not an issue in surgical practice, another third of participants perceived fellow surgeons to be propagators of gender inequity.21 Our results suggest that gender bias within the surgical community, perhaps more unconscious than conscious, remains a barrier to the success for female surgical leaders.

In addition to echoing the call to action for enhanced research on the topic of gender inequity in the surgical field, improved bias training, objective oversight, transparency in salary modeling, and design of personal and family support systems in the workplace issued by both the American College of Surgeons and the American Surgical Association in response to the 2018 survey’s results, the cohort vocalized a need for careful intentionality and crafted attention to culture building as a means of counteracting gender bias.21,22,23 The cohort discussed the employment of work-around strategies as contributory to their success. By definition, a work-around strategy allows for bypass of a greater system issue for task completion to be achieved.24,25 Ultimately, the need for work-around strategies is suggestive of an existing system’s inability to accommodate the complexity of the tasks that it is intended to service.24,25 In this context, these results call for systems-level restructuring to attend to the needs of a diverse workforce on whom demands are increasingly multifactorial. As participant 16 pointed out, “there must be intentionality toward these issues. I think that it’s important that we are inclusive and that we show that we are family friendly, all gender friendly, and that we are all racial, ethnic, and religious group friendly. We need greater inclusivity, the more people that stand up and show that they are fantastic surgeons and leaders that look different. What do they all have in common? They are excellent and they are surgeons and they are leaders.” It is perhaps with such intentionality and systemic change that we will not only close the gender gap, but also enhance the overall cultural diversity of the surgical field. “I think that we are moving in the right direction but it is going to take the work of all of us to continue.”

Strengths and Limitations

Strengths of this study include its qualitative methods, which allowed us to explore the experiences of the cohort in an in-depth, descriptive manner. Through this information, we were able to unravel complex interplay of both internal and external factors leading to leadership and achievement. In addition, to our knowledge, this is the first study that has had access to such a unique cohort of surgeons. We aimed to establish a high degree of trustworthiness through achievement of thematic saturation, consensus coding throughout to ensure shared thematic impressions, and triangulation of results through member checking.

This work also has limitations. The study may be limited by inclusion of only female academic general surgeons. Excluding male chairs allowed for exploration of a key minority perspective; future direction for this work may include comparison with a male perspective of career progress. Expansion to surgeons working primarily in the community setting and within different surgical subspecialties might have produced different results. While our research team is composed of staff at various levels of surgical training, personal experiences with surgical culture may have introduced some degree of bias into the interview and analysis phases of this work. However, shared experiences within the surgical field experienced by the cohort and research team may also have allowed for a unique degree of open dialogue.

Conclusions

Our work suggests that strong leadership personality traits combined with adaptability enabled this cohort of women to reach the highest strata of achievement in academic surgery despite sometimes challenging external factors. Enhanced intentionality toward fostering a global culture of increased inclusivity, curricula toward cultivating personality traits, speaking-out behavior, resilience, bias reduction, and improved work-system design may help to support the career pathways of not only female, but a more demographically and culturally diverse body, of surgeons and leadership.

eTable 1. Semi-Structured Interview Template

eTable 2. Member Checking Survey

References

- 1.American Association of Medical Colleges More women than men enrolled in US medical schools in 2017. 2017, Published December 17, 2017. Accessed November 29, 2019. https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/press-releases/more-women-men-enrolled-us-medical-schools-2017

- 2.American Association of Medical Colleges ACGME residents and fellows by sex and specialty, 2017. Published x. Accessed November 29, 2019. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/interactive-data/acgme-residents-and-fellows-sex-and-specialty-2017.

- 3.American Association of Medical Colleges Table 13: US medical school faculty by sex, rank, and department, 2019. Updated 2020. Accessed April 8, 2020. https://www.aamc.org/system/files/2020-01/2019Table13.pdf

- 4.American Association of Medical Colleges Table C: department chairs by department, sex, and race/ethnicity, 2019. Updated 2020. Accessed April 8, 2020. https://www.aamc.org/system/files/2020-01/2019%20Supplemental%20Table%20C.pdf

- 5.American College of Surgeons Society of Surgical Chairs Membership Directory. Accessed January 2, 2020. https://web4.facs.org/ebusiness/ssc/Default.aspx

- 6.Blumenthal DM, Bergmark RW, Raol N, Bohnen JD, Eloy JA, Gray ST. Sex differences in faculty rank among academic surgeons in the United States in 2014. Ann Surg. 2018;268(2):193-200. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Association of Women Surgeons Female chairs of departments of surgery. Updated 2019. Accessed November 29, 2019. https://www.womensurgeons.org/page/FemaleSurgeryChairs

- 8.Epstein NE. Discrimination against female surgeons is still alive: where are the full professorships and chairs of departments? Surg Neurol Int. 2017;8:93. doi: 10.4103/sni.sni_90_17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bruce AN, Battista A, Plankey MW, Johnson LB, Marshall MB. Perceptions of gender-based discrimination during surgical training and practice. Med Educ Online. 2015;20:25923. doi: 10.3402/meo.v20.25923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scully R, Davids J, Melnitchouk N. Maternity leave is associated with greater financial pressure and career dissatisfaction among female physicians in procedural specialties. J Am Coll Surg. 2016;223(4)(suppl 1):S112. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2016.06.231 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scully RE, Davids JS, Melnitchouk N. Impact of procedural specialty on maternity leave and career satisfaction among female physicians. Ann Surg. 2017;266(2):210-217. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dahlke AR, Johnson JK, Greenberg CC, et al. Gender differences in ulilization of duty-hour regulations, aspcects of burnout, and psychological well-being among general surgery residents in the United States. Ann Surg. 2018;268(2):204-211. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Furnas HJ, Garza RM, Li AYJ, et al. Gender differences in the professional and personal lives of plastic surgeons. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2018;142(1):252-264. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000004478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kuerer HM, Eberlein TJ, Pollock RE, et al. Career satisfaction, practice patterns and burnout among surgical oncologists: report on the quality of life of members of the Society of Surgical Oncology. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14(11):3043-3053. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9579-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Satele D, Sloan J, Freischlag J. Relationship between work-home conflicts and burnout among American surgeons: a comparison by sex. Arch Surg. 2011;146(2):211-217. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2010.310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Knörr H. Factors that contribute to women’s career development in organizations: a review of the literature. Published 2005. Accessed December 4, 2019. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED492334.pdf

- 17.Palinkas LA, Horwitz SM, Green CA, Wisdom JP, Duan N, Hoagwood K. Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2015;42(5):533-544. doi: 10.1007/s10488-013-0528-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Giles S. The most important leadership competencies, according to leaders around the world. Harvard Business Review. Published March 15, 2016. Accessed December 29. 2019. https://hbr.org/2016/03/the-most-important-leadership-competencies-according-to-leaders-around-the-world

- 19.Stevenson JE, Orr E We interviewed 57 female CEOs to find out how more women can get on top. Harvard Business Review. Published November 8, 2017. Accessed December 29. 2019. https://hbr.org/2017/11/we-interviewed-57-female-ceos-to-find-out-how-more-women-can-get-to-the-top

- 20.Chamorro-Premuzic T. What science tells us about leadership potential. Harvard Business Review. Published September 21, 2016. Accessed December 29. 2019. https://hbr.org/2016/09/what-science-tells-us-about-leadership-potential

- 21.Aziz HA, Ducoin C, Welsh DJ, et al. 2018 ACS Governors survey: gender inequality and harassment remain a challenge in surgery. American College of Surgeons. Published 2018. Accessed December 29. 2019. 2019. https://bulletin.facs.org/2019/09/2018-acs-governors-survey-gender-inequality-and-harassment-remain-a-challenge-in-surgery/

- 22.Schneidman D. Women at the helm of the ACS: charting a course to gender equity. Published September 1, 2018. Accessed December 29, 2019.. https://bulletin.facs.org/2018/09/women-at-the-helm-of-the-acs-charting-a-course-to-gender-equity/

- 23.West MA, Hwang S, Maier RV, et al. Ensuring equity, diversity, and inclusion in academic surgery: an American Surgical Association white paper. Ann Surg. 2018;268(3):403-407. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Debono DS, Greenfield D, Travaglia JF, et al. Nurses’ workarounds in acute healthcare settings: a scoping review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13(175):175. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-13-175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alter S. Theory of workarounds. Communications of the Association for Information Systems. Published 2014. Accessed December 29. 2019. https://aisel.aisnet.org/cais/vol34/iss1/55/

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Semi-Structured Interview Template

eTable 2. Member Checking Survey