Abstract

Spain has been one of the most affected countries by the COVID-19 outbreak. After the high impact of the pandemic, a wide clinical spectrum of late complications associated with COVID-19 are being observed. We report a case of a severe Clostridium difficile colitis in a post-treatment and recovered COVID-19 patient. A 64-year-woman with a one-month hospital admission for severe bilateral pneumonia associated with COVID-19 and 10 days after discharge presented with diarrhoea and abdominal pain. Severe C. difficile-associated colitis is diagnosed according to clinical features and CT findings. An urgent pancolectomy was performed due to her bad response to conservative treatment. Later evolution slowly improved to recovery.

C. difficile-associated colitis is one of the most common hospital-acquired infections. Significant patient-related risk factors for C. difficile infection are antibiotic exposure, older age, and hospitalisation. Initial therapeutic recommendations in our country included administration broad-spectrum antibiotics to all patients with bilateral pneumonia associated with SARS-CoV-2. These antibiotics are strongly associated with C. difficile infection. Our patient developed a serious complication of C. difficile due to the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics.

The appearance of late digestive symptoms in patients diagnosed and treated for COVID-19 should alert clinicians to the possibility of C. difficile infection. The updated criteria for severe colitis and severe C. difficile infection should be considered to ensure an early effective treatment for the complication.

Keywords: 2019 Novel coronavirus disease, COVID-19, Spain, SARS-CoV-2, Respiratory diseases, Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, Colitis, Clostridium difficile infection, Toxic megacolon

Background

In December 2019, hospitals reported a cluster of cases with pneumonia of unknown cause in Wuhan, China, attracting great attention nationally and worldwide.1 In January 2020, researchers isolated a novel coronavirus, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), in patients with confirmed pneumonia. Real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and next-generation sequencing were used to characterise the virus.2 Spain is one of the countries most affected by the COVID-19 outbreak. As of 21 May 2020, the number of confirmed cases was 233,037, including 151,000 patients recovered, more than 11,454 admitted to intensive care, with 27,940 deaths, a global case fatality rate of 11.9%.3

Fever, cough, myalgia, and fatigue are the common symptoms of COVID-19, whereas expectoration, headache, haemoptysis and diarrhoea are relatively rare.4

Clostridium difficile-associated colitis is one of the most common hospital-acquired infections. Antibiotics do not directly affect SARS-CoV-2, but viral respiratory infections often lead to bacterial pneumonia. Although antimicrobial prophylaxis has not been recommended except in patients with a long course of disease,5 initial therapeutic recommendations in our country included administration broad-spectrum antibiotics for all patients with bilateral pneumonia. We report a case of a severe C. difficile colitis in a patient post-treatment and recovery from COVID-19.

Case history

A 64-year-woman with a seven-day history of fever up to 38.5C, cough and anosmia, was diagnosed with bilateral pneumonia and COVID-19 in a PCR test in March 2020. Her medical history included hypothyroidism, dyslipidaemia and obesity. The patient was treated following the Madrid experimental study, which included azithromycin, ceftriaxone, hydroxychloroquine, lopinavir/ritonavir and antithrombotic prophylaxis with enoxaparin. The patient received three-day dexamethasone bolus treatment and a single dose of tocilizumab. Owing to early poor respiratory evolution, the patient required orotracheal intubation for nine days. She was initially discharged in May with a negative PCR for COVID-19, after 35 days of admission in hospital.

Ten days after discharge from hospital, the patient was readmitted with diarrhoea and abdominal pain. Biochemistry indicated leucocytes 9.58 × 103c/μl (reference 4–11 × 103c/μl), D-dimer 3.3μg/ml (reference 0.1–0.5μg/ml), C-reactive protein 329mg/l (reference 0–5mg/l), procalcitonin 6.72ng/ml (reference 0–0.1ng/ml), lactate dehydrogenase 316u/l (reference 135–225u/l) and lactic acid 3.6mmol/l (reference 0.5–1mmol/l). C. difficile screening was positive; enzyme immunoassay of glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH-EIA) and toxin A enzyme immunoassay (EIA) were positive. Treatment with intravenous metronidazole and intrarectal vancomycin was started. A thoracic computed tomography (CT) angiography was performed and bilateral pulmonary thromboembolism was diagnosed. Therapeutic thrombotic enoxaparin was given.

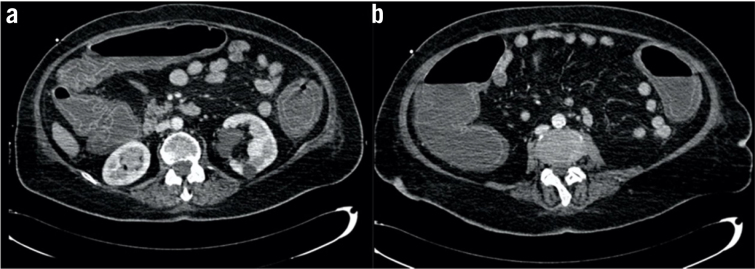

The response to treatment was refractory. The patient’s haemodynamic status worsened and she suffered sepsis, respiratory and renal failure. An abdominal CT showed marked pancolonic wall dilatation and thickening with no signs of perforation, compatible with toxic megacolon (Fig 1). In agreement with the intensive medicine department and infectious diseases service, an urgent surgical intervention was indicated, and pancolectomy was performed with a Brooke ileostomy and mucous fistula in the rectal stump. The surgical sample of the colon showed dilatation and thickening of the wall associated with ulcers and pseudomembranes in mucosa.

Figure 1. Computed tomography sagittal sections showing significant colon dilatation compatible with toxic megacolon.

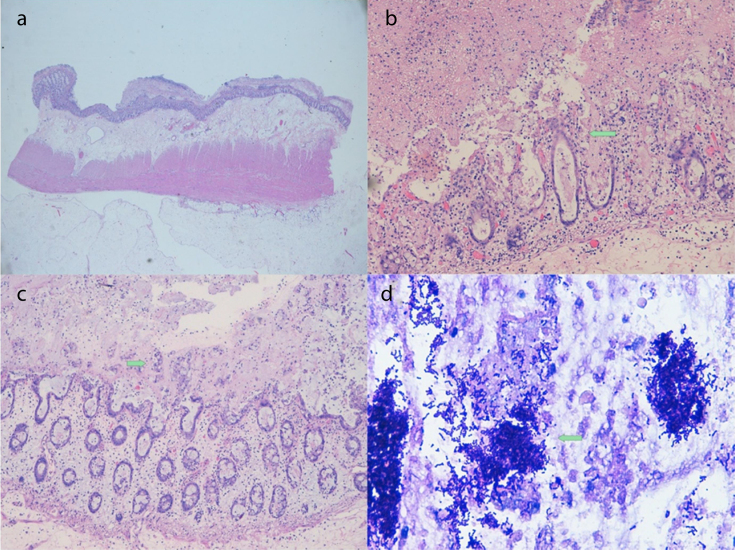

Histopathological findings revealed colonic mucosa presenting patched areas with material of a greyish membranous appearance attached to the mucosa. The colon wall showed significant oedema. Microscopic study identified areas of erosion and ulceration of the epithelium and markedly dilated crypts with abundant mucoid and fibrinonecrotic material that burst to the surface (like a volcanic eruption) in continuity of pseudomembranes. We observed abundant Gram-positive coccobacilli, Pas and Giemsa positive (Fig 2). Virus structures were not identified in the mucosa of the colon, and the only microorganisms that were observed were Clostridium bacteria. After the procedure and the maintenance of intensive medical treatment in hospital, our patient progressively improved to total recovery.

Figure 2. A. Panoramic view of the colonic wall showing significant oedema in submucosa and the presence of pseudomembranes. B. Erosion and ulceration of the epithelium and markedly dilated crypts. Eruption in continuity to pseudomembranes (arrow). C. Dilated crypts. Presence of abundant groups of goblet cells expelled to pseudomembranes (arrow). D. Groups of Gram-positive coccobacilli, Clostridium difficile (arrow).

Discussion

C. difficile is a Gram-positive, spore-forming, anaerobic bacillus that is widely distributed in the intestinal tract of humans and animals and in the environment.6 Spores of C. difficile are transmitted by the faecal–oral route and the pathogen is widely present in the environment. Potential reservoirs for C. difficile include asymptomatic carriers, infected patients, the contaminated environment and animal intestinal tracts (canine, feline, porcine, avian). Approximately 5% of adults and 15–70% of infants are colonised by C. difficile, and the colonisation prevalence is several times higher in hospitalised patients or nursing home residents.7

Until the 1970s, C. difficile was considered as a microorganism that is rarely present in normal intestinal microbiota. After the introduction of antibiotics, the role of C. difficile in the pathogenesis of large intestine diseases increased.8 Significant patient-related risk factors for C. difficile infection are antibiotic exposure, older age, and hospitalisation.6 The clinical symptoms associated with the infection range from mild, self-limiting diarrhoea to fulminant colitis, and can include pseudomembranous colitis, toxic megacolon (severe dilatation of the colon), bowel perforation and sepsis and/or multiple organ dysfunction syndrome.9 All antibiotic classes can be associated with C. difficile infection, but clindamycin, cephalosporins and fluoroquinolones are the most frequently cited.10

COVID-19, which is caused by infection with SARS-CoV-2 predominantly includes pulmonary symptoms; however, almost 10% of cases also include gastrointestinal events, including abdominal pain, diarrhoea and vomiting.11,12 Although antimicrobial prophylaxis is not recommended except in patients with a long course of disease,5 initial therapeutic recommendations in our country included administration broad-spectrum antibiotics for all patients with bilateral pneumonia.13,14 These antibiotics are strongly associated with C. difficile infection.15 A US clinical surveillance study screened patients with COVID-19 and observed a C. difficile infection rate of 3.6/10,000 patient-days.16 We could find no publications describing severe C. difficile infection colitis due to COVID-19 broad-spectrum antibiotic treatment.

C. difficile infection is a challenging disease, with a recurrence rate of 15%–20% and a mortality rate of 5%.17 Symptoms of C. difficile infection may be masked by concomitant COVID-19 infection, because both conditions can have similar features. In a study of 206 patients with COVID-19, 19.4% had diarrhoea as the first symptom.18

In our case, the patient developed a septic clinical status associated with diarrhoea and abdominal pain, 10 days after her hospital discharge for COVID-19 positive bilateral pneumonia diagnose. According to European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID) guidance, no single test is suitable as a stand-alone test confirming C. difficile infection. The best way to optimise the diagnosis of C. difficile infection is to combine two or three tests: detection of C. difficile products (cell culture cytoxicity assay, glutamate dehydrogenase and toxins A and/or B), toxigenic culture of C. difficile and nucleic acid amplification tests.19 Our patient was confirmed with GDH-EIA and toxin A EIA.

ESCMID updated its guidelines, and metronidazole, vancomycin and to a lesser extent fidaxomicin were considered to be the cornerstone of antibiotic treatment for CDI19; the criteria for severe colitis and severe C. difficile infection are also included in the guidance.19 Colectomy should be performed to treat C. difficile infection in perforation of the colon and/or not responding to antibiotic therapy systemic inflammation, with deteriorating condition.20

Conclusions

We generally know very little of the multifaceted biologic characteristics of COVID-19. To our knowledge, COVID-19 associated severe C. difficile infection has not been previously reported; clinicians may therefore have a low clinical suspicion for this disease. The appearance of late digestive symptoms in patients diagnosed with COVID-19 should alert clinicians to the possibility of a diagnosis of C. difficile infection.

References

- 1.Wang C, Horby PW, Hayden FG, Gao GF. A novel coronavirus outbreak of global health concern. Lancet 2020; : 470–473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in china, 2019. N Engl J Med 2020; : 727–733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 2020; : 497–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centro de Coordinación de Alertas y Emergencias Sanitarias Ministerio de Sanidad de España. Actualización no. 112. Enfermedad por el coronavirus (COVID-19). 2020. https://www.mscbs.gob.es/en/profesionales/saludPublica/ccayes/alertasActual/nCov-China/documentos/Actualizacion_112_COVID-19.pdf (cited June 2020).

- 5.Xu K, Cai H, Shen Y et al. [Management of COVID-19: the Zhejiang experience.] Zhejiang Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban 2020; : 147–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Czepiel J, Dróżdż M, Pituch H et al. Clostridium difficile infection: review. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2019; : 1211–1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leffler DA, Lamont JT. Clostridium difficile infection. N Engl J Med 2015; : 1539–1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tedesco FJ, Barton RW, Alpers DH. Clindamycin-associated colitis. Ann Intern Med 1974; : 429–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smits WK, Lyras D, Lacy DB et al. Clostridium difficile infection. Nat Rev Dis Primer 2016; : 16020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Slimings C, Riley TV. Antibiotics and hospital-acquired Clostridium difficile infection: update of systematic review and meta-analysis. J Antimicrob Chemother 2014; : 881–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet 2020; : 507–513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang D, Hu B, Hu C et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA 2020; : 1061–1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang X, Yu Y, Xu J et al. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a single-centered, retrospective, observational study. Lancet Respir Med 2020; : 475–481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen T, Wu D, Chen H et al. Clinical characteristics of 113 deceased patients with coronavirus disease 2019: retrospective study. BMJ 2020; : m1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown KA, Khanafer N, Daneman N, Fisman DN. Meta-Analysis of antibiotics and the risk of community-associated Clostridium difficile infection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2013; : 2326–2332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sandhu A, Tillotson G, Polistico J et al. Clostridioides difficile in COVID-19 patients, Detroit, Michigan, USA, March–April 2020. Emerg Infect Dis 2020. May 22 [Epub ahead of print.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guh AY, Mu Y, Winston LG et al. Trends in U.S. Burden of Clostridioides difficile infection and outcomes. N Engl J Med 2020; : 1320–1330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Han C, Duan C, Zhang S et al. Digestive symptoms in COVID-19 patients with mild disease severity: clinical presentation, stool viral RNA testing, and outcomes. Am J Gastroenterol 2020; : 916–923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Debast SB, Bauer MP, Kuijper EJ. European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases: update of the treatment guidance document for Clostridium difficile infection. Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2014; : 1–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bauer MP, Kuijper EJ, Dissel JT van. European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID): treatment guidance document for Clostridium difficile infection (CDI). Clin Microbiol Infect 2009; : 1067–1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]