Abstract

The characterization of polymer–polymer interfaces is of great interest to understand the diffusion process and chemical interactions in polymeric multiphase systems. This study investigated the formation of the interface layer between polyamide (PA) and polypropylene (PP) and its dependency on the maleic anhydride (MAH) content in PP. New insights with a very high level of details on the formation of the interfacial layer are obtained by employing a special technique of atomic force microscopy (AFM) combined with infrared (IR) for chemical imaging at nanoscale spatial resolution. This enables the determination of the interface thickness and even the observation and visualization of the diffusion gradient across the PA/PP interface layer. Combined with classical investigation methods such as interfacial energy and rheology, the method of nano-IR spectroscopy represents a very powerful tool to obtain more insights and a deeper understanding of the interfacial phenomenon in multiphase polymeric systems.

Introduction

Interface plays a crucial role in polymer multiphase systems due to its high impact on the structure formation and mechanical characteristics of the system. In most cases, polymers are thermodynamically not miscible and thus show weak interfacial adhesion. In the last decades, many efforts were made to investigate and to better understand the interface phenomena in immiscible multiphase polymer systems using different analytical methods. Among others, rheological investigations are often carried out, e.g., to clarify the rheology–microstructure relationship in polymer blend or to investigate the polymer interface.1−3 The phase morphology, driven by the interfacial tension and processing conditions, is often characterized and visualized by electron microscopy or atomic force microscopy (AFM).4,5 In addition, classical polymer analytical methods such as thermal analysis,6 infrared (IR) spectroscopy,7 X-ray scattering,8 etc. are also widely used to characterize multiphase polymer systems.

From the material system point of view, model systems comprising polyamide (PA) and polyolefins (polypropylene (PP), polyethylene (PE)) are very often used to investigate the interfacial phenomenon and its influence on the morphology formation of the polymer blends. This is on one hand due to the lack of chemical functional groups in polyolefins and on the other hand due to the relatively high interfacial energy between those polymers, which is thermodynamically unfavorable for interfacial diffusion and results in a weak adhesion. A common strategy to overcome this restriction is blend compatibilization using PP grafted with maleic anhydride (PP-g-MAH) or polyethylene grafted with maleic anhydride (PE-g-MAH).9−11

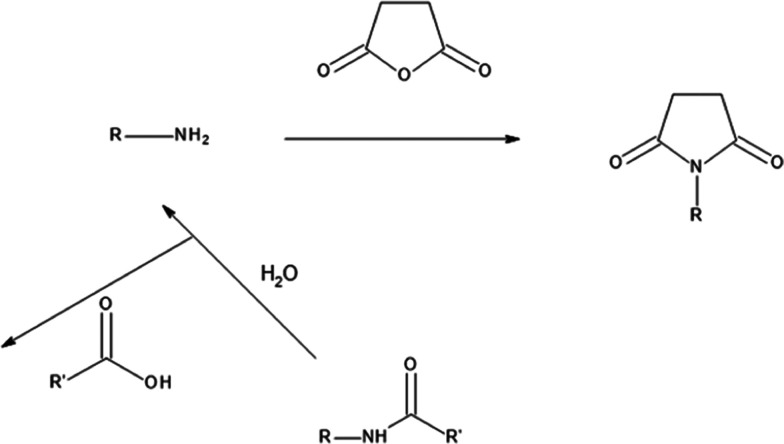

Widely accepted influencing factors for the adhesion in a modified PA/PP system are covalent interactions and interfacial diffusion. Covalent interaction occurs between the terminal amine of PA6 with the anhydride group of the functionalized PP as depicted in Scheme 1. The amino end group of PA reacts with the anhydride group, thus forming an imide bond. The amide group in the PA chain can also react if there is an excess of anhydride available, but likely only after hydrolysis by water to an amine and carboxylic acid, finally resulting in a chain scission of the PA and the formation of imide. The formation of these imide bonds was confirmed by infrared spectroscopic analysis.12 Microscopic analysis of PA/PP blends has demonstrated that the sharp interface disappears in the presence of PP-g-MAH.13,14 Findings from attenuated total reflectance–Fourier transform infrared (ATR–FTIR) mapping have confirmed that an interface layer is formed between the PA and PP phase in the presence of PP-g-MAH in the blend.15 According to these findings, the thickness of the interface layer should depend on the MAH content in the PP. However, this dependency is not yet investigated.

Scheme 1. Reaction Mechanism between Amino End Group in PA and MAH in Functionalized PP.

Although the theory of phase compatibilization is well accepted for decades, the characterization of the interface layer formation is still a big challenge, as most analytical techniques only give indirect information about the diffusion at the interface. Classical investigation of the interfaces is based on microscopic, mechanical, and rheological methods. The phase adhesion strength is often evaluated mechanically by simple peel tests.16 Microscopic and rheological characterizations provide information about phase adhesion and the particle size of the dispersed phase but do not deliver direct proofs about interfacial diffusion as a consequence of the modification. Methods analyzing diffusion dynamics, on the contrary, directly address the chemical composition of the interface layer. The disadvantage is that these methods are laborious and the chemical labeling of the polymer chains influences its diffusion dynamics.17 Chemical imaging by ATR–FTIR mapping is of high interest for the chemical investigation, as this technique provides information about the chemical composition of the polymers at the interface.15 However, the mapping with this method is limited to a relatively low resolution.

A more advanced chemical visualization technique is infrared (IR) technology at a nanoscale resolution (nano-IR) in combination with atomic force microscopy (AFM). Nano-IR technology has been shown to be a useful tool for characterization of multilayer laminates,18 polymer blends,19 composites,20−22 and cross sections of fibers.23 The basic principle of nano-IR technology is the combination of AFM and the detection of material-specific photothermal-induced resonance (PTIR). The usage of the AFM cantilever provides the possibility of chemical mapping of the sample surface at nanoscale resolution and overcomes the problem of the low resolution obtained by conventional IR spectroscopy.24,25 In this study, we have intentionally used the known model system PA/PP/PP-g-MAH for the investigation of the polymer interface with the objective to gain a better understanding of the formation of interface layer upon modification. The system was modified by varying the content of PP-g-MAH. Basic characterization was performed by evaluating the thermodynamic interfacial behavior based on the surface energy of the polymers and by rheological investigation of the melt-flow behavior. For the rheological investigation, a simplified two-layer system was used to restrict the influence of the morphology on the system. The dependency of the interface layer thickness on the PP-g-MAH content was chemically imaged using the nano-IR technique combined with AFM.

Experimental Section

Polyamide 6 (PA, Durethan B30S, Lanxess AG, Germany, Tm = 222 °C, Mw = 30 000 g/mol, Mn = 12 000 g/mol) film with a thickness of 120 μm was kindly provide by the Transfer Center for Kunststofftechnik (TCKT, Austria). Homo-polypropylene HC101BF (neat PP, Tm = 165 °C, Mw = 365 000 g/mol, Mn = 48 000 g/mol) and homo-polypropylene grafted with maleic anhydride BB127E (PP-g-MAH with 0.16 wt % MAH content, Tm = 165 °C, Mw = 215 000 g/mol, Mn = 25 000 g/mol) were provided by Borealis Polyolefine GmbH (Austria). Those PP grades show almost identical melt-flow behavior as determined by rheological characterization despite different molecular weights. To generate polypropylene grades with different MAH contents, neat PP and PP-g-MAH were melt blended in different weight ratios using the laboratory twin-screw extruder (Process 11 L/D 40, ThermoFisher, Germany) at 230 °C and a screw speed of 200 rpm. PP-g-MAH samples with a MAH content of 0, 0.01, 0.03, 0.13, and 0.16 wt %, respectively, were generated and pressed into films at 200 °C and 50 bar using a hot press (Polystat 200T, ServiTec GmbH, Germany). All polymer films were cleaned with 99.9% ethanol in advance to the investigations. Diiodomethane (Sigma-Aldrich, 99% purity) was used for surface tension measurement.

The surface tensions and interfacial energies were calculated from the contact angles (θ) of demineralized water and diiodomethane at 20 ± 2 °C on a Krüss Easy drop instrument equipped with a Teli CCD camera and onboard software. For the calculation of the surface energy, the Owens, Wendt, Rabel, and Kaelble (OWRK) model was used.26 The work of adhesion (Wa) between PA and the different PP grades were calculated using the Owens–Wendt–Dupré equation27

| 1 |

whereas σp is the polar part and σd is the disperse part of the polymer surface energy. Indexes 1 and 2 indicate PA and PP, respectively.

Frequency sweeps were performed using a rheometer (Modular Compact Rheometer MCR 302, Anton Paar GmbH, Austria) with a parallel-plate system at 240 °C with 5% stain and a gap of 0.1 mm between the plates. The angular frequency was set on a range from 0.1 to 600 rad/s. The laminates made of one layer of each polymer were prepared in the parallel-plate setting of the rheometer at 240 °C for 5 min prior to the measurement.

ATR–FTIR spectra were recorded on a Bruker Vector 22 instrument (Germany). The ATR unit was equipped with a diamond crystal. A total of 128 scans were collected for each spectrum from 500 to 4000 cm–1 at a resolution of 2 cm–1.

For the investigation of PA/PP-g-MAH laminates with AFM and nano-IR, three-layer laminates were pressed at 240 °C and 30 bar for 10 min to create PP/PA interfaces. A PA film was pressed between two PP sheets with a total thickness of approximately 2 mm. Cross sections of the laminates were prepared using an ultra cryo-microtome (EM UC7, Leica Microsystems GmbH, Germany) equipped with a diamond knife (cryo 45°, DiATOME AG, Switzerland) at −40 °C. Approximately 500 nm thick cross sections were placed on an IR inactive ZnS windows for further investigations. AFM and nano-IR investigations were performed in AFM contact mode (nanoIR2, Anasys Instruments Inc., Santa Barbara). The scan rate of the AFM was 0.5 Hz.

For nano-IR analysis, an infrared laser irradiates pulses having different wavelengths on the sample surface. The sample absorbs the IR light if the wavelength is in resonance with the vibrations of a molecular structure, leading to thermal expansion and a subsequent vibration of the cantilever. The deflection of the cantilever is detected by a four-quadrant detector. The amplitude of the deflection is proportional to the absorption of the IR pulse28 and its Fourier transformation is recorded.24 For the collection of nano-IR spectra, 10 ns infrared laser pulses with a rate of 1 kHz are generated. The IR spectra were recorded over a range from 1300 to 1800 cm–1 and from 2700 to 3600 cm–1. A total of 32 scans were collected for each spectrum at a resolution of 4 cm–1. The nano-IR imaging was performed at the wavenumber of 3300 cm–1.

Results and Discussion

The adhesion between PA and PP depends on the interfacial thermodynamics. As PA has relatively high surface energy, its interfacial energy with nonmodified PP is high (Table 1). Therefore, the adhesion and diffusion between the two phases are thermodynamically unfavorable. To enhance the phase adhesion, diffusion, and formation of an interface layer, the surface energy of the nonmodified PP is increased by the addition of PP-g-MAH. As shown in Table 1, the surface energy of PP-g-MAH depends on its MAH content. The more MAH is present in the PP, the higher is the surface energy of PP. Subsequently, PP-g-MAH grade with higher surface energy has lower interfacial energy to PA and as a result a higher work of adhesion to PA. In fact, the values only indicate tendencies, as the surface energies were determined from solid samples at room temperature. Nevertheless, the calculation supports that the adhesion and diffusion between PA and PP-g-MAH in the molten state are thermodynamically more favorable if more MAH is present in PP-g-MAH. Therefore, a larger interface layer between the two phases is expected by increasing the amount of MAH.

Table 1. Surface Energies of PA and Different PP-g-MAH Grades and the Corresponding Interfacial Energy and Work of Adhesion at the PP/PA Interfacea.

| sample | σp (mN/m) | σd (mN/m) | σtotal (mN/m) | σPA/PP (mN/m) | Wa,PA/PP (mN/m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PA | 8.99 | 43.54 | 52.52 | ||

| 0 wt % MAH | 0.02 | 31.40 | 31.42 | 9.14 | 74.80 |

| 0.01 wt % MAH | 0.14 | 31.49 | 31.64 | 7.87 | 76.29 |

| 0.03 wt % MAH | 0.16 | 33.79 | 33.96 | 7.34 | 79.14 |

| 0.13 wt % MAH | 0.22 | 34.12 | 34.34 | 6.96 | 79.90 |

| 0.16 wt % MAH | 0.69 | 33.78 | 34.48 | 5.30 | 81.70 |

The total surface energies are indicated with σtotal, and their polar and disperse portions as σp and σd, respectively. σPA/PP is the interfacial energy and Wa,PA/PP is the work of adhesion.

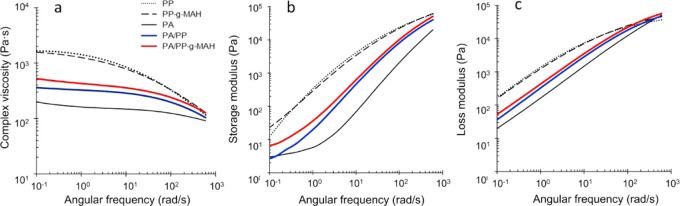

Another common technique for interfacial analysis in multiphase polymer systems is rheology, as the viscosity, storage, and loss modulus of multiphase systems depend not only on the neat polymers but also on the interface layer. Numerous studies have shown that compatibilization of immiscible polymer blends increases the melt shear moduli and viscosity.29−32 However, the morphology and the volume fractions of the dispersed and continuous phase of blends also influence the results.33 In our study, we simplified the multiphase system to a two-layer laminar morphology (Figure 1) to eliminate the dispersed phase morphology of blends.

Figure 1.

Effect of interfacial modification on a laminar structure. In a nonmodified PA/PP laminate, the interface between the two phases is sharp (a) and under shear stress, interfacial slippage may occur (b). In the PA/PP-g-MAH laminate, an interfacial layer is formed due to diffusion between the PA and PP-g-MAH phases (c). This strengthens the interface and stabilizes the system under shear deformation (d).

The laminates were prepared in the parallel-plate setting in the rheometer, 5 min in advance to the measurement, to allow interfacial diffusion to take place. The results obtained from frequency sweeps show that the complex viscosity, storage, and loss modulus values of the laminates lay between the ones of the neat polymers (Figure 2a–c). This shows that both polymers contribute to the flow behavior of the laminate. The values of PA/PP-g-MAH (0.16 wt % MAH) laminate are higher compared to that of the PA/neat PP (without MAH) laminate, demonstrating the interfacial strengthening effect in the modified systems. The similar strengthening effect observed by rheological investigation has also been reported in the literature for other polymer blend systems.30,32

Figure 2.

Effect of interface modification on the melt flow of PA/PP laminates. Complex viscosities (a), storage moduli (b), and loss moduli (c) of the neat polymers, PA/PP and PA/PP-g-MAH laminates.

It is thought that the higher viscosity and moduli of PA/PP-g-MAH system, compared to those of the nonmodified PA/PP system, indicate a better formation of an interface layer consisting of both PA and PP chain segments. As schematically illustrated in Figure 1, the shear stress of the molten laminate depends on all phases of the system: PA, PP, and the interface. As the melt-flow behavior of the neat polymers does not change after modification, change in the complex viscosity, storage, and loss modulus can be interpreted as a result of the formation of an interface layer. However, the effect appears to be small, as, during the shear of the laminar melt (Figure 2), the polymer chains are arranged in the direction of the shear34 and therefore hinder the different phases from diffusing into each other.

It is worth noting that both neat PP and PP-g-MAH show almost identical melt viscosity despite their different molecular weights. Hence, the formation of the interface layer observed by rheological measurement is less driven by the melt-flow behavior of PP-g-MAH and more by the existence of functional MAH groups in PP (expressed by the higher polar part of the surface energy of PP in Table 1), leading to the compatibilization effect between PP-g-MAH and PA, as postulated in Scheme 1.

To further investigate the formation of the interface layer depending on the MAH content, PA/PP-g-MAH laminates with different MAH content (0–0.16 wt %) were analyzed using the nano-IR technique.

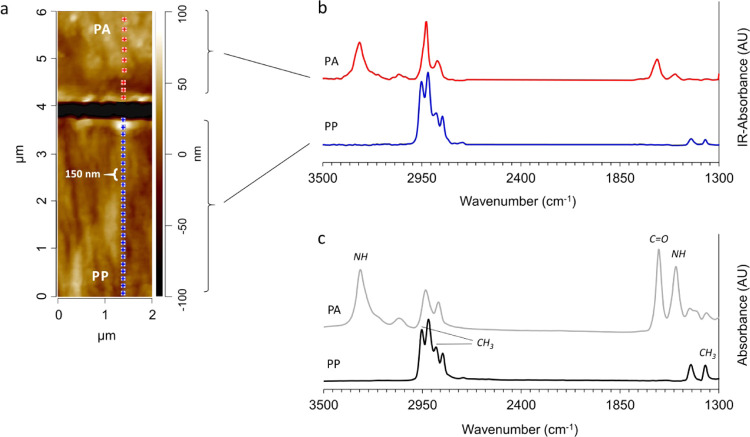

Figure 3a represents AFM image of the cross section of a laminate of PA with neat PP (0 wt % MAH). The colored spots in the AFM image with 150 nm spacing (blue in PP phase and red in PA phase) indicate where the nano-IR spectra are scanned. In the PP phase, all recorded spectra are identical. Also, all recorded spectra in the PA phase are identical. Thus, to simplify the graph, only two corresponding nano-IR spectra are plotted for each phase in Figure 3b.

Figure 3.

AFM height image (a) and IR spectra of PA and PP recorded by nano-IR (b) and conventional ATR–FTIR (c) of PA/PP laminate containing 0 wt % MAH. The dark area in the image is the ZnS glass due to delamination during the cryo-cutting procedure.

The comparison between the nano-IR technique (Figure 3b) and conventional ATR–FTIR (Figure 3c) validates the results of nano-IR measurements, as the spectra of PA and PP obtained with both methods are almost identical, except some varying intensity based on the detection technologies. Typical peaks derived from N–H stretching vibrations at 3300 cm–1, C=O stretching vibrations (amide I) at 1635 cm–1, and N–H stretching vibrations (amide II) at 1535 cm–1 were observed for PA, and those derived from CH3 stretching vibrations at 2870 cm–1 and for CH3 bending vibrations at 1373 cm–1 were observed for PP.35,36

Nano-IR spectra recorded at the interface of PA/neat PP laminate (Figure 3b) show neither PA-specific peaks found in the PP region nor PP-specific peaks in the PA region. These data explain the weak adhesion between PA and PP, as neither diffusion nor coupling reaction takes place at the interface, although the PA and PP were pressed in a molten state for 10 min at 240 °C. This laminate has a very weak interfacial adhesion so that delamination occurred during the cryo-cutting process at −40 °C. The low surface energy of neat PP and calculated work of adhesion (Table 1) support these findings.

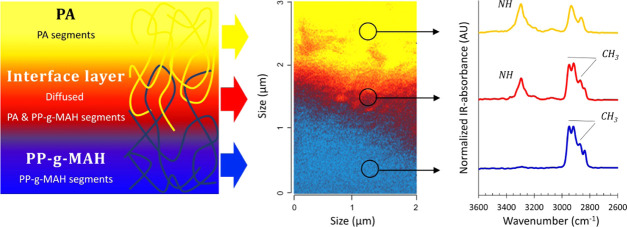

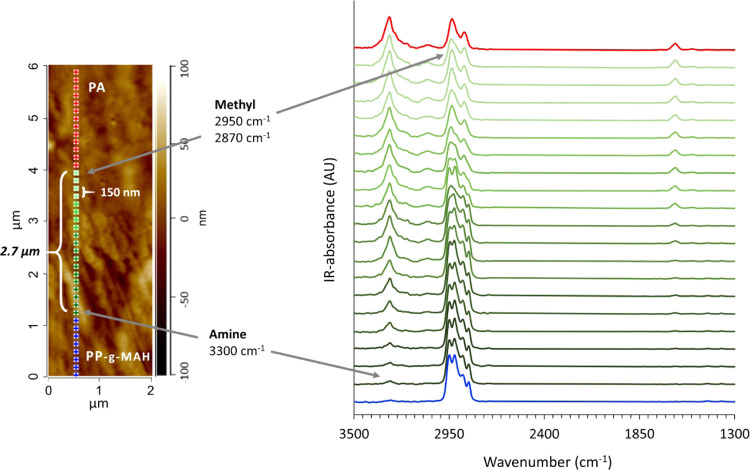

When modifying the PP phase with MAH, the situation changed remarkably. AFM image in Figure 4 shows that an interface layer is formed between PA and PP-g-MAH (0.16 wt % MAH), indicated by the green spots with the corresponding nano-IR spectra. The interface layer is defined as the area where both polymers can be detected, showing both PA-specific peaks at 3298, 1635, and 1535 cm–1 as well as PP-specific peaks at 2950, 2870, and 1373 cm–1. The interface layer ends toward the PA phase by the disappearance of the peaks derived from the CH3 stretching vibration of PP. The end of the interface layer toward the PP phase is determined by the lack of the peak at 3298 cm–1 assigned to the NH stretching of PA. According to recorded nano-IR spectra, an interface layer thickness of 2.7 μm is observed.

Figure 4.

AFM height image and IR spectra of PA/PP-g-MAH laminate containing 0.16 wt % MAH. The colored spots in the AFM image with 150 nm spacing indicate where the nano-IR spectra are recorded. PA is in red, PP in blue, and the interface layer in green; the color of the spots correspond to the color of the spectra.

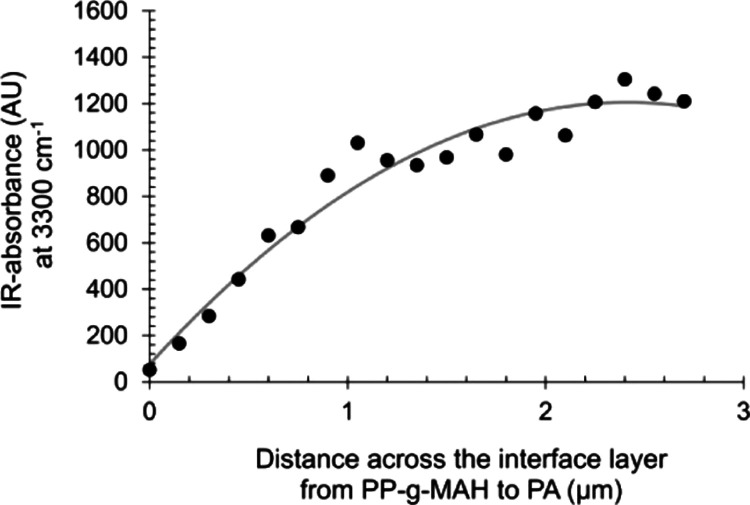

Considering the interface layer as a diffusion zone containing both polymer segments, the concentration gradient is identified by nano-IR scanning. The scans across the interface layer clearly show that there is a concentration gradient of the polymer segments. The normalized height of the NH peak at 3300 cm–1, for example, can be taken as a measure of the diffusion intensity of PA across the interface layer. This is graphically illustrated in Figure 5 for PA/PP laminate containing PP-g-MAH with 0.16 wt % MAH.

Figure 5.

Relative PA content across the PA/PP-g-MAH interface. The peak height, derived from the NH vibration at 3300 cm–1, was used for indicating the relative PA gradient across the interface layer of a laminate containing PP-g-MAH with 0.16 wt % MAH.

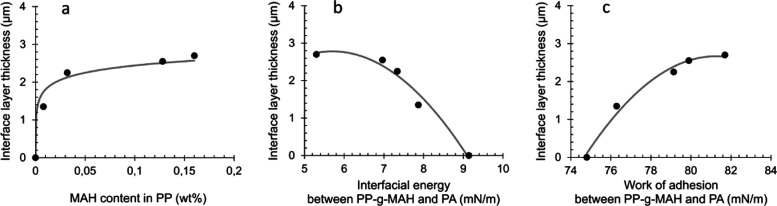

Applying the same approach, the interface layer thicknesses were also determined for PA/PP-g-MAH laminates with the MAH content of 0.1, 0.03, and 0.13 wt %, respectively (Figure 6a).

Figure 6.

Correlation between PA/PP-g-MAH interface thickness and MAH content (a), interfacial energy (b), and work of adhesion (c).

The nano-IR scanning of PA/PP-g-MAH laminates containing MAH has shown that at a low MAH content of 0.01 wt % already some diffusion occurs and an interface layer of 1.35 μm is formed. The higher MAH content present in the PP phase leads to an increased interface layer thickness (Figure 6a).

As PP-g-MAH has a lower molecular weight (Mw = 215 000 g/mol) compared to that of neat PP (Mw = 365 000 g/mol), the increased amount of PP-g-MAH in the PP phase contributes to a higher fraction of PP with lower molecular weight and thus shorter polymer chain length in the PP phase. According to the repetition model, the diffusion coefficient of a polymer in the molten stage depends on the molecular weight: the lower the molecular weight, the higher the coefficient.37 However, the results of rheological investigations showed that the melt viscosities of neat PP and PP-g-MAH are almost identical. Furthermore, the laminate with PP-g-MAH even exhibited higher melt viscosity (Figure 2a). Thus, the contribution of the lower-molecular-weight fraction to the increased thickness of the interface layer is believed to be much less pronounced compared to the contribution of the MAH functionalization of PP.

Thus, the reason behind the better diffusion between PA and PP can be expressed by the higher number of functional MAH groups. The C=O bonds enhance the surface energy of PP and subsequently the interfacial energy with PA becomes lower, which again is thermodynamically more favorable for interfacial diffusion (Figure 6b,c). Moreover, the diffusion is driven by in situ formation of PP-graft-PA polymer chains at the interface through coupling reactions between the MAH groups in PP-g-MAH and amino end groups of PA (Scheme 1). These findings prove that the increased adhesion between PA and PP, upon compatibilization with PP-g-MAH, is based on enhanced diffusion between the two phases. The evolution of the thickness of the interface layer as a function of the MAH content (Figure 6a) can be explained, that possible coupling reactions only take place at the interface with a limited number of MAH groups as the majority of MAH is present in the bulk of the PP phase. Very likely, the availability of MAH groups at the PP surface does not directly correlate to the increase of the total MAH content in the PP phase, although a calculation of the number of the MAH groups at the interface cannot be done properly and would require too many assumptions and speculations.

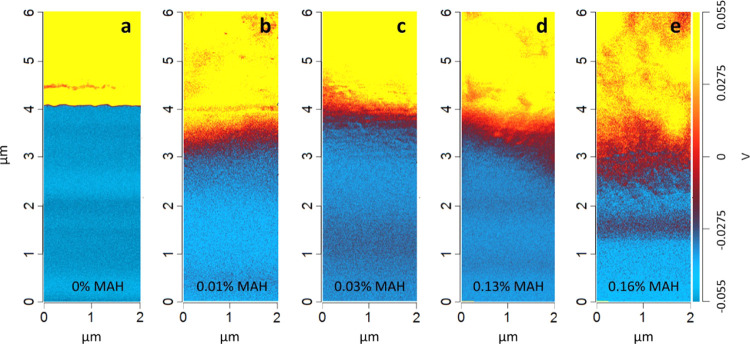

For the chemical visualization of the interface layers, the same cross sections of laminates were used for the nano-IR scanning. The sample area around the interface layer was scanned at the wavenumber of 3300 cm–1, which is specific for N–H stretching in PA.

Figure 7a represents the PA/PP laminate without MAH. In this case, the nano-IR image shows a sharp border between PA (indicated in yellow) and PP (indicated in blue), demonstrating that no diffusion has taken place due to the high interfacial energy and missing coupling reaction. With the presence of 0.01 wt % MAH in PP, the interfacial energy has slightly decreased and the diffusion zone (indicated in red) reaches a thickness of about 1 μm and up to 2.5 μm in case of 0.16 wt % MAH in PP (Figure 7b–e). As expected, the interface layer thickness increases with MAH content in PP. Moreover, the concentration gradient of PA across the interface layer, as described in Figure 5, is also visible in the nano-IR images. The intensity of the IR signal at 3300 cm–1 is highest in the PA area (yellow), where no PP-g-MAH is present. Across the interface layer, the intensity of the peak decreases, indicated by orange, red, and violet, and finally reaches the PP-g-MAH area (blue), where no PA is detected. Some red areas included in the PA phase are most likely artifacts of the measurement, as nano-IR imaging is very sensitive to the variation of the sample height and thickness. Compared to a similar study on compounded PA/PP blends using ATR–FTIR mapping in the literature,15 nano-IR imaging provided a much higher resolution and allows us to have a better insight into the interface region.

Figure 7.

Nano-IR images of PA/PP-g-MAH laminates scanned at 3300 cm–1. The MAH content in the PP varies from 0 to 0.16 wt %. The NH stretching at 3300 cm–1 is specific for PA. The higher the intensity (V), the more PA is present. PP is indicated in blue, PA in yellow and the interface layer in red. Note that the ZnS glass (see Figure 3a) does not give any signal at 3300 cm–1 and hence provides the same color as the PP phase in (a).

It can be concluded that IR imaging at nanoscale supports the findings obtained from the nano-IR scanning. The interdiffusion depends on interfacial energy. The presence of MAH grafted on PP increases the surface energy of PP, decreases the interfacial energy with PA, and enhances the work of adhesion with PA, leading to thermodynamically more favorable interdiffusion between PA and PP.

Conclusions

Using advanced chemical visualization by infrared spectroscopy at nanoscale resolution, the formation of the polymer interface by diffusion was examined. For the sake of simplification, the known system PA/PP and a simple experimental setup using laminates were chosen to bring new insights into a well-established research topic of the interface in multiphase polymer systems.

With a special focus on the analysis of the structure of the interface region, we could show and visualize, for the first time in a very high degree of resolution, that the well-discussed phase compatibilization effect in polymer blends is driven by the enhanced diffusion, leading to the thickening of the interface layer between the polymers. Furthermore, the increase in the thickness of the interface layer with an increased modification degree of PP (MAH content) could also be visualized, including the gradient of the polymer content across the interface layer.

Calculation of the surface energies has shown that the presence of MAH in PP decreases the interfacial energy with PA and enhances the work of adhesion. Thermodynamically, this favors the diffusion between the two phases. The enhanced interdiffusion between PA and PP segments in the presence of MAH is demonstrated by the increased melt viscosity and shear moduli of PA/PP-g-MAH laminates. Using the nano-IR technique, the diffusion at the interface was chemically and thermally mapped, providing new insights into the correlation between the interfacial energy and the diffusion at the interface. The formation of the interface layer depends on the MAH concentration. Increased MAH content lowers the interfacial energy between PA and PP and increases the interface layer thickness. A thorough investigation of diffusion kinetics, i.e., studies on the effects of time and temperature, is being undertaken in ongoing work.

Analysis by nano-IR scanning provides detailed chemical information about the diffusion gradient across the interface layer, while nano-IR imaging helps to visualize the formation of the interface layer. The results support the well-accepted theory of the in situ phase compatibilization through the reaction between the amino end groups in PA with MAH groups in functionalized PP.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge financial support from the Austrian Federal Ministry for Climate Action, Environment, Energy, Mobility, Innovation and Technology (BMK) to the Endowed Professorship Advanced Manufacturing FFG-846932, the Transfercenter für Kunststofftechnik GmbH (Wels, Austria) for PA film processing and Borealis Polyolefine GmbH (Austria, Linz) for PP film processing and providing granulates.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Salehiyan R.; Song H. Y.; Kim M.; Choi W. J.; Hyun K. Morphological Evaluation of PP/PS Blends Filled with Different Types of Clays by Nonlinear Rheological Analysis. Macromolecules 2016, 49, 3148–3160. 10.1021/acs.macromol.6b00268. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Salehiyan R.; Ray S. S.; Bandyopadhyay J.; Ojijo V. The Distribution of Nanoclay Particles at the Interface and Their Influence on the Microstructure Development and Rheological Properties of Reactively Processed Biodegradable Polylactide/Poly(Butylene Succinate) Blend Nanocomposites. Polymers 2017, 9, 350 10.3390/polym9080350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plattier J.; Benyahia L.; Dorget M.; Niepceron F.; Tassin J. F. Viscosity-Induced Filler Localisation in Immiscible Polymer Blends. Polymer 2015, 59, 260–269. 10.1016/j.polymer.2014.12.044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Salehiyan R.; Ray S. S.; Ojijo V. Processing-Driven Morphology Development and Crystallization Behavior of Immiscible Polylactide/Poly(Vinylidene Fluoride) Blends. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 2018, 303, 1800349 10.1002/mame.201800349. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Malwela T.; Ray S. S. Role of Organoclay in Controlling the Morphology and Crystal-Growth Behavior of Biodegradable Polymer-Blend Thin Films Studied Using Atomic Force Microscopy. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 2014, 299, 1106–1115. 10.1002/mame.201300408. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yousfi M.; Livi S.; Dumas A.; Crépin-Leblond J.; Greenhill-Hooper M.; Duchet-Rumeau J. Compatibilization of Polypropylene/Polyamide 6 Blends Using New Synthetic Nanosized Talc Fillers: Morphology, Thermal, and Mechanical Properties. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2014, 131, 1–12. 10.1002/app.40453. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ojijo V.; Ray S. S.; Sadiku R. Role of Specific Interfacial Area in Controlling Properties of Immiscible Blends of Biodegradable Polylactide and Poly[(Butylene Succinate)-Co-Adipate]. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2012, 4, 6690–6701. 10.1021/am301842e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotella C.; Tencé-Girault S.; Cloitre M.; Leibler L. Shear-Induced Orientation of Cocontinuous Nanostructured Polymer Blends. Macromolecules 2014, 47, 4805–4812. 10.1021/ma500653z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Datta R. K.; Polk M. B.; Kumar S. Reactive Compatibilization of Polypropylene and Nylon. Polym.-Plast. Technol. Eng. 1995, 34, 551–560. 10.1080/03602559508012204. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lamnawar K.; Maazouz A. Rheological Study of Multilayer Functionalized Polymers: Characterization of Interdiffusion and Reaction at Polymer/Polymer Interface. Rheol. Acta 2006, 45, 411–424. 10.1007/s00397-005-0062-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X.; Jiang G.; Wu H.; Guo S. Effect of the Temperature Gradient on the Interfacial Strength of Polyethylene/Polyamide 6 during the Sequential Injection Molding. High Perform. Polym. 2014, 26, 135–143. 10.1177/0954008313501531. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roeder J.; Oliveira R. V. B.; Gonçalves M. C.; Soldi V.; Pires A. T. N. Polypropylene/Polyamide-6 Blends: Influence of Compatibilizing Agent on Interface Domains. Polym. Test. 2002, 21, 815–821. 10.1016/S0142-9418(02)00016-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim B. K.; Park S. Y.; Park S. J. Morphological, Thermal and Rheological Properties of Blends: Polyethylene/Nylon-6, Polyethylene/Nylon-6/(Maleic Anhydride-g-Polyethylene) and (Maleic Anhydride-g-Polyethylene)/Nylon-6. Eur. Polym. J. 1991, 27, 349–354. 10.1016/0014-3057(91)90186-R. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ide F.; Hasegawa A. Studies on Polymer Blend of Nylon 6 and Polypropylene or Nylon 6 and Polystyrene Using the Reaction of Polymer. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1974, 18, 963–974. 10.1002/app.1974.070180402. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X.; Zhang P.; Jiang X.; Rao G. Influence of Maleic Anhydride Grafted Polypropylene on the Miscibility of Polypropylene/Polyamide-6 Blends Using ATR-FTIR Mapping. Vib. Spectrosc. 2009, 49, 17–21. 10.1016/j.vibspec.2008.04.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heinzmann C.; Weder C.; De Espinosa L. M. Supramolecular Polymer Adhesives: Advanced Materials Inspired by Nature. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016, 45, 342–358. 10.1039/C5CS00477B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fundamentals of Adhesion; Lee L.-H., Ed.; Springer Science & Business Media: New York, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Kelchtermans M.; Lo M.; Dillon E.; Kjoller K.; Marcott C. Characterization of a Polyethylene-Polyamide Multilayer Film Using Nanoscale Infrared Spectroscopy and Imaging. Vib. Spectrosc. 2016, 82, 10–15. 10.1016/j.vibspec.2015.11.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ye J.; Midorikawa H.; Awatani T.; Marcott C.; Lo M.; Kjoller K.; Shett R. Nanoscale Infrared Spectroscopy and AFM Imaging of a Polycarbonate/ Acrylonitrile-Styrene/Butadiene Blend. Microsc. Anal. 2012, 26, 24–27. [Google Scholar]

- Marcott C.; Lo M.; Hu Q.; Dillon E.; Kjoller K.; Prater C. B. Nanoscale Infrared Spectroscopy of Polymer Composite. Am. Lab. 2014, 46, 2–4. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh S.; Ramos L.; Remita S.; Dazzi A.; Deniset-Besseau A.; Beaunier P.; Goubard F.; Aubert P.; Remita H. Conducting Polymer Nanofibers with Controlled Diameters Synthesized in Hexagonal Mesophases. New J. Chem. 2015, 39, 8311–8320. 10.1039/C5NJ00826C. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tang F.; Bao P.; Su Z. Analysis of Nanodomain Composition in High-Impact Polypropylene by Atomic Force Microscopy-Infrared. Anal. Chem. 2016, 88, 4926–4930. 10.1021/acs.analchem.6b00798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rietzler B.; Bechtold T.; Pham T. Spatial Structure Investigation of Porous Shell Layer Formed by Swelling of PA66 Fibers in CaCl2/H2O/EtOH Mixtures. Langmuir 2019, 35, 4902–4908. 10.1021/acs.langmuir.8b03741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dazzi A.; Glotin F.; Carminati R. Theory of Infrared Nanospectroscopy by Photothermal Induced Resonance. J. Appl. Phys. 2010, 107, 124519 10.1063/1.3429214. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dazzi A.; Prater C. B.; Hu Q.; Chase D. B.; Rabolt J. F.; Marcott C. AFM-IR: Combining Atomic Force Microscopy and Infrared Spectroscopy for Nanoscale Chemical Characterization. Appl. Spectrosc. 2012, 66, 1365–1384. 10.1366/12-06804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens D. K.; Wendt R. C. Estimation of the Surface Free Energy of Polymers. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1969, 13, 1741–1747. 10.1002/app.1969.070130815. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Skrivanek T.Determination of the Surface Free Energy of Electronic Components; Krüss Application Report, 2003; pp 1–4.

- Dazzi A.; Prazeres R.; Glotin F.; Ortega J. M.; Al-Sawaftah M.; de Frutos M. Chemical Mapping of the Distribution of Viruses into Infected Bacteria with a Photothermal Method. Ultramicroscopy 2008, 108, 635–641. 10.1016/j.ultramic.2007.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow W. S.; Ishak Z. A. M.; Karger-Kocsis J. Morphological and Rheological Properties of Polyamide 6/Poly(Propylene)/ Organoclay Nanocomposites. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 2005, 290, 122–127. 10.1002/mame.200400269. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fu X.; Liu X.; Zhang C.; Liu H.; Hu Y.; Zhang X. Synthesis of Propylene-Co-Styrenic Monomer Copolymers via Arylation of Chlorinated PP and Their Compatibilization for PP/PS Blend. Polymers 2019, 11, 157 10.3390/polym11010157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Alamilla M.; Valadez-Gonzalez A. The Effect of Two Commercial Melt Strength Enhancer Additives on the Thermal, Rheological and Morphological Properties of Polylactide. J. Polym. Eng. 2016, 36, 31–41. 10.1515/polyeng-2014-0322. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kallel T.; Massardier-Nageotte V.; Jaziri M.; Gérard J. F.; Elleuch B. Compatibilization of PE/PS and PE/PP Blends. I. Effect of Processing Conditions and Formulation. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2003, 90, 2475–2484. 10.1002/app.12873. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hietaoja P. T.; Holsti-Miettinen R. M.; Seppälä J. V.; Ikkala O. T. The Effect of Viscosity Ratio on the Phase Inversion of Polyamide 66/Polypropylene Blends. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1994, 54, 1613–1623. 10.1002/app.1994.070541104. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lamnawar K.; Baudouin A.; Maazouz A. Interdiffusion/Reaction at the Polymer/Polymer Interface in Multilayer Systems Probed by Linear Viscoelasticity Coupled to FTIR and NMR Measurements. Eur. Polym. J. 2010, 46, 1604–1622. 10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2010.03.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Andreassen E.Infrared and Raman Spectroscopy of Polypropylene. In Polypropylene: An A-Z Reference; Karger-Kocsis J., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, Netherlands, 1999; Vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- de Carvalho A. P. A.; da Silva Sirqueira A. Effect of Compatibilization in Situ on PA/SEBS Blends. Polímeros 2016, 26, 123–128. 10.1590/0104-1428.2195. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kausch H. H.; Tirrell M. Polymer Interdiffusion. Annu. Rev. Mater. Sci. 1989, 19, 341–377. 10.1146/annurev.ms.19.080189.002013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]