Abstract

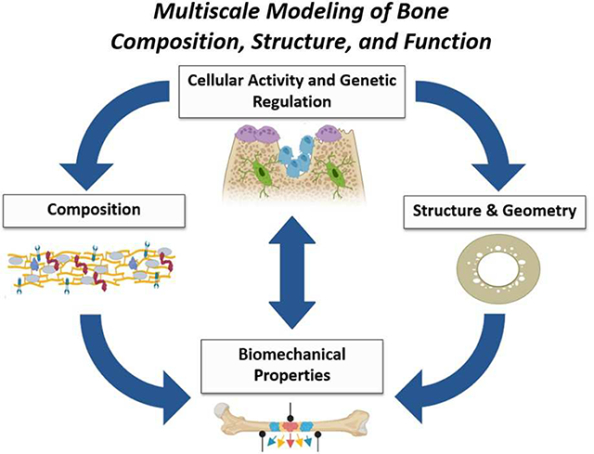

Advancements in imaging, computing, microscopy, chromatography, spectroscopy and biological manipulations of animal models, have allowed for a more thorough examination of the hierarchical structure and composition of the skeleton. The ability to map cellular and molecular changes to nano-scale chemical composition changes (mineral, collagen cross-links) and structural changes (porosity, lacuno-canalicular network) to whole bone mechanics is at the forefront of an exciting era of discovery. In addition, there is increasing ability to genetically mimic phenotypes of human disease in animal models to study these structural and compositional changes. Combined, these recent developments have increased the ability to understand perturbations at multiple length scales to better realize the structure-function relationship in bone and inform biomechanical models. The intent of this review is to describe the multiple scales at which bone can characterized, highlighting new techniques such that structural, compositional, and biological changes can be incorporated into biomechanical modeling.

Keywords: Biomechanics, Mineral, Collagen, Bone microstructure

Graphical Abstract

1.1. Introduction

The hierarchical nature of bone necessitates that structure-function relationships be defined across multiple length scales. The skeleton is constantly adapting to maintain mechanical function through structural and compositional changes triggered by biological signaling. Historically, modeling of structure-function relationships has been based on continuum mechanics, with less focus on physiologically-relevant nanostructural and compositional features. Advances in the ability to genetically or biochemically perturb bone composition as well as imaging modalities to visualize nano-scale architecture, embrace the potential to understand the relationship between bone biology, structure, composition and mechanics.

The foundation of bone mechanics is based on traditional mechanical testing procedures. However, most mechanical testing of bone assumes mechanical properties can be measured by modeling bone as an idealized geometry with homogenous, isotropic properties (i.e., three or four -point bending, torsion, fatigue) [1]. For example, fracture toughness of a rodent whole bone can be calculated by modeling the bone as a cylindrical tube, allowing for standard beam bending assumptions to be made [2]. As a biologic material, bone is not static, but constantly remodeling, changing dimensions, and altering material properties due to endogenous and exogenous influences. Therefore, it is critical for modeling of bone biomechanics to incorporate a hierarchical approach - taking into account how bones adapt to altered functional demands via changes in shape (length scale of mm), internal architecture (length scale of μm) and mineral or collagen changes (length scale of nm).

Biological influence is an added complexity to the structure-function analysis rubric, as genetic alterations manifest themselves throughout the hierarchy of bone composition and structure. Advancements in genetic manipulation of animal models allow researchers to investigate how changes in cellular behavior (osteoblast, osteocyte, osteoclast activity), propagate to changes in, composition (collagen, mineral, proteins, growth factors) and structure (porosity, lacuno-canalicular network), and ultimately to changes in mechanical function. The purpose of this review is to describe the multiple scales at which bone can be understood and characterized, highlighting new state-of-the-art techniques such that structural, compositional, and biological changes can be incorporated into biomechanical modeling.

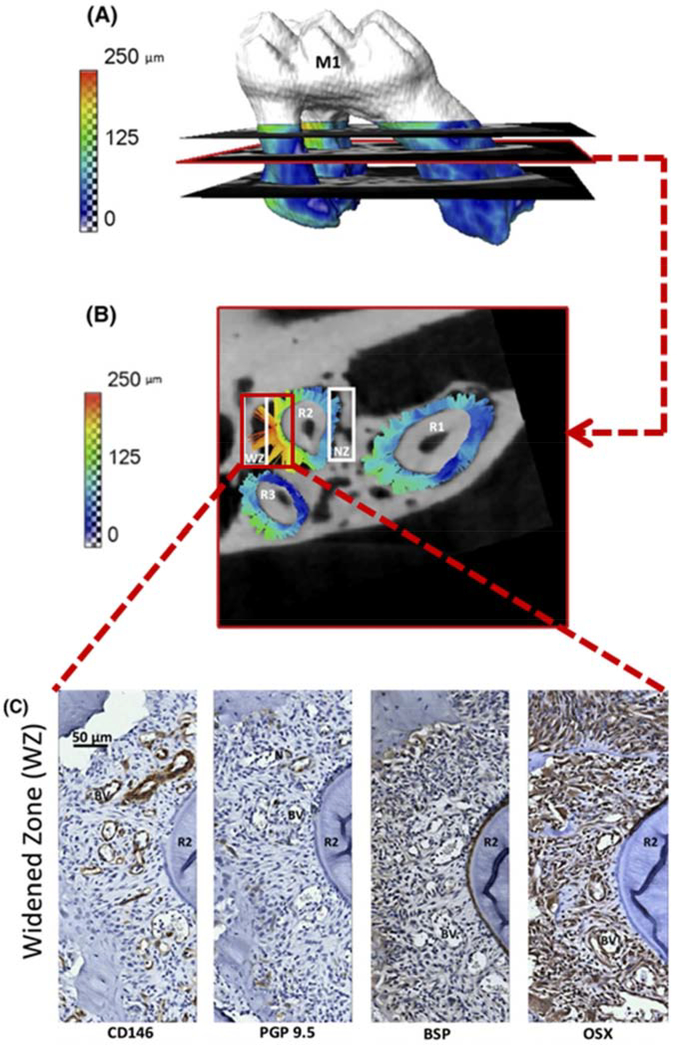

2.1. Whole Bone Level

Understanding bone function on a bulk, mechanical scale has been limited by simplifying assumptions about the geometric shape and the resolution at which the tissue can be modeled and analyzed. Advanced computing and imaging technologies such as high-resolution peripheral quantitative computed tomography (HR-pQCT) and high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), now allow for solid body objects to be created from scans of numerous skeletal tissues and used as input into multidimensional models to simulate physiologic loads. Such models are predictive of direct mechanical measures such as bone strength, but are less predictive of post-yield mechanics [3]. With the advent of imaging such as HR-pQCT and MRI, actual bone in-situ geometries and loading schemes can be studied, something not possible using traditional mechanical testing methods (samples trimmed to standard beams for mechanical testing). Enhanced in situ modeling lends itself to more accurate depictions of in vivo loading and understanding of biomechanical processes. More accurate modeling of complex geometries such as the bone/periodontal ligament/tooth unit [4], human vertebrae [5], the atlantoaxial joint [6] is now possible. Smaller scale features such as microcracks in trabecular struts and vasculature [7] can also be incorporated into whole bone mechanical models. For example, in the dentoalveolar joint, the forces modeled coupled with histological stains for vascular, neuronal, and osteoblastic tissues, allow for attribution of mechanical forces and tooth movement to bone resorption processes (Figure 1). Coupling of advanced imaging techniques of bone with local measures of cellular activity (ie. histology or gene expression) and mapping into whole bone mechanics [4] will increase understanding of how local structural and matrix changes impact whole bone mechanics and function.

Figure 1:

Three-dimensional model of tooth and periodontal ligament movement (A), isolated to a two dimensional map (B), histological staining at the same region (C). Modeling of forces and tissue movement experienced under loading of complex geometries such as the dentoalveolar joint has been made possible by increases in nano-scale resolution of imaging and high powered computer processing. These modeled forces can then be correlated to biological drivers by more traditional means such as histology and staining of proteins related to neurovasculature and osteoblasts (Adapted from [4], with permission).

3.1. Structure & Geometry

To initially gain understanding of structure-function relationships in bone, morphological measures, such as external diameter [8], moment of inertia and trabecular network [9], were critical. Increasing resolution of imaging systems has allowed for the study of intracortical features such as porosity and the canalicular networks, leading to enhanced understanding of structural influences on mechanical properties.

3.2. Porosity

Advances in methods such as micro/nano-computed tomography have allowed for the nano-scale quantification of mineralized tissues [10] and rendering of 3D models of these tissue for finite element modeling [11,12]. A significant aspect of this approach is that a biological process such as modeling/remodeling of bone with age can be captured by quantifiable size and density changes in pore geometry. This pore information can be applied to multivariate models to predict whole bone strength [13] or employed in a computational model to determine correlations between porosity and strain energy density [11]. The use of nano-CT has allowed for increased resolution and definition of cortical pores and highlighted the regulation of human bone strength with age in phenotypic subsets of the population [13]. Therefore, porosity is an important factor to consider in overall structure of cortical tissues of long bones, and may be of interest in other bone sites.

3.3. Osteocytes and the Lacuno-Canalicular Network

Osteocytes are embedded in the mineralized matrix of bone and form a complex network between the lacunae they reside in and their interconnecting canaliculi. This fluid-filled network senses mechanical loads and transduces the mechanical signal to a biochemical signal that triggers bone turnover and adaptation. The surrounding mineralized matrix and nano-scale features of the osteocyte network make it difficult to study and image in three dimensions. However, recent advancements allow for more thorough visualization of the osteocyte lacuno-canalicular network (LCN). Two dimensional visualization can be accomplished by resin casting of bone sections [14] or acid etching of embedded samples [15]. One method to visualize the three dimensional structure of the LCN is by staining bone sections with rhodamine, which will infiltrate internal network surfaces, including blood vessels, lacunae, and canaliculi. Confocal imaging, z-stacking and subsequent image processing allows for a resolution of 250–300 nm [16,17]. Use of third-harmonic generation imaging to visualize rhodamine infiltrated sections has had similar success [18,19]. Synchrotron nano computed tomography (SR-nanoCT) also been able to image the 3D network of the LCN after rigorous segmentation and reconstruction methods [20]. Ptychographic X-ray CT (PXCT) relies on diffraction and subsequent retrieval algorithms, and provides three dimensional images of the LCN and lacunae shape [21]. Three-dimensional images of the osteocyte LCN, like those obtained by SR-nanoCT, can also be used to model the mechanical loads put upon the network and better understand fluid shear and mechanosensing [22].

The complex geometry of the LCN output from two dimensional stacked, or three dimensional images can be difficult to subsequently characterize. Key parameters of the LCN include lacunar density, total number of osteocyte connections, lacuno-canalicular fraction or network parameters likes edge density, node degree, and centrality measures [23,24]. Future work should focus on determining which measures of the osteocyte LCN are most relevant to bone mechanosensing, composition, and mechanics. Being able to probe the properties of the LCN has promising implications for understanding how disease, age, and other physiologies influence loading adaptations.

4.1. Composition

Just as bone is often simplified into a beam or cylinder shape for mechanical testing, the composition of bone is often simplified as a two-phase composite, comprised of a stiff mineral component imbedded in a tensile polymeric or collagen matrix. Technological advances have allowed for better characterization of the mineral, collagen, interactions between the mineral and collagen, and cellular components of bone. Accounting for the ultrastructural features of mineral, collagen and other proteins advance the ability to link functional relevance of bone composition to disease.

4.2. Enzymatic Cross-Links

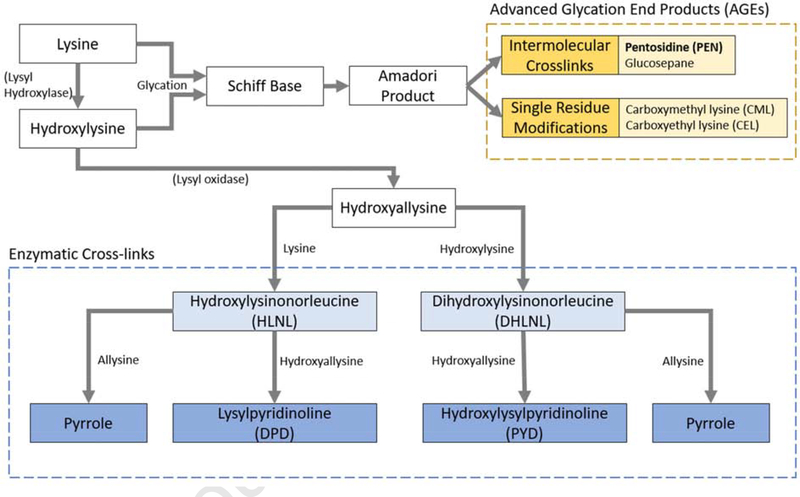

Collagen is a bio-polymer, which is assembled in type I collagen as fibrils and acquires posttranslational, covalent modifications via the family of enzymes: lysyl hydroxylases (LH), lysyl oxidase (LOX), or via the formation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs such as pentosidine (PEN)) (Figure 2). These enzymes control tissue-specific patterning of the enzymatic cross-links. In bone, the predominant immature cross-links are the divalent cross-links, dihydroxylysinonorleucine (DHLNL), hydroxylysinonorleucine (HLNL). The predominant mature cross-links form spontaneously from either the DHLNL or HLNL with an available allysine or hydroxyallisine group (from which the immature cross-links form as well). These mature cross-links are the hydroxylysylpyridinoline (PYD), lysylpyridinoline (DPD), and pyrroles. The non-enzymatic AGEs form from an available lysine or hydroxylysine group via glycation or oxidative stress.

Figure 2:

Simplified collagen cross-linking pathways for both enzymatic cross-link and advanced glycation end product (AGE) formation. Immature divalent enzymatic cross-links are simplified to their sodium borohydride reduced forms hydroxylysinonorleucine (HLNL) and dihydroxylysinonorleucine (DHLNL) (Adapted from [63], with permission)

Intermolecular, lysyl-oxidase mediated, collagen cross-links stabilize type I collagen and contribute to mechanical properties of bone. Techniques to measure cross-links directly have relied on high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), with a reverse phase ion-pairing column chemistry and fluorescent detection. Naturally fluorescing cross-links (PYD, DPD, PEN) can be easily detected, however, non-fluorescent species (DHLNL, HLNL) require derivatization by ninhydrin or o-pthalaldehyde for fluorescent detection [25]. This LC methodology has been translated to electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) [26], which allows for comprehensive quantification of the enzymatic collagen crosslinks without subsequent derivatization steps. Recently, a methodology was developed using a silica hydride column and ESI-MS friendly solvents that allowed for detection of reduced immature cross-links HLNL, DHLNL, and mature cross-link, PYD [27]. DPD, in addition to PYD, was measured with a similar methodology [28]. Coupling of mass spectrometry detection with LC methods allows for precise quantification of additional species (ie. proteins) in parallel with the enzymatic collagen cross-links, such as other AGEs besides PEN. Beyond LC, it may be possible to quantify proteins in situ using matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-imaging mass spectrometry (MALDI-IMS) [29].

These methodologies outlined above allow for characterization of the entire collagen cross-link profile with age, disease, or other physiological conditions to elucidate the relationship between composition and mechanics, which can subsequently be applied experimentally or to in silico predictive models of mechanics. For example, in a mouse model of lathyrism in which LOX is inhibited, bone fracture toughness, strength, and pyridinoline cross link content are reduced [25]. Ratios reflecting relative cross link maturity are positive regressors of fracture toughness, whereas quantities of mature pyridinoline cross links are significant positive regressors of strength. Subjecting these mice to exercise promotes pyridinoline cross-linking, and the resulting increase in total mature cross-linking is sufficient to counteract the mechanical effects of cross-link inhibition [30].

In silico modeling of the collagen network in bone has been conducted using full atomistic simulations and finite element simulations. This approach is useful for controlled manipulations of theoretical conformations of collagen that can be confirmed experimentally. Recently, the use of 3D coarse-grained models simulated the mechanical behavior of collagen fibrils with enzymatic collagen cross-links [31]. This model was applied to collagen cross-links in human adult and child bone samples to predict fibril mechanical properties and found the increased number of immature enzymatic crosslinks (HLNL, DHLNL) in young bone (5–16 years), was responsible for the increased elastic modulus and elastic work in bones from young vs. old individuals [32]. Being able to model how differing collagen cross-links affect the deformation of collagen fibrils is a step towards modeling how composition dictates bone mechanics. However, to advance such modeling even further, mineral, AGEs, and their interaction should also be considered.

4.3. Non-Enzymatic Cross-links & Advanced Glycation End Products (AGEs)

Characterization of non-enzymatic collagen cross-links or advanced glycation end products (AGEs) relies on fluorescent detection of pentosidine as a surrogate marker for total AGE content or in a non-specific fluorometric assay [33]. To date, no complete profile of AGEs in bone has been done. Computational techniques using atomistic models of collagen fibrils have tried to identify other AGEs that may form in bone. Candidates identified include glucosepane and imidazolium cross-links [34,35]. Modeling the relative mechanical contribution of these candidate AGEs showed a theoretical increase in moduli at low strains with variations between glucosepane and imidazolium cross-links depending on site [36]. Experimental confirmation of the results of these computational studies with established screening methodologies for AGEs [37] would advance understanding of the AGE profile in bone, relative abundance and contribution of AGEs to bone strength and toughness, especially in regards to pathologies which accumulate AGEs [33].

4.4. Mineral

Bone mineral is comprised of hydroxyapatite crystals with varying size, crystallinity and stoichiometry, depending on location, age, and disease. Characterization of bone mineral scales from bulk or regional bone mineral density measured using techniques such as microCT and dual x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA), to molecular composition at a micro-scale resolution using techniques such as Raman spectroscopy, Fourier transformation infrared technology (FTIR), quantitative backscattered electron microscopy (qBEI), as well as a combination of these technologies [38]. Combinations of techniques allow for a more comprehensive understanding of bone mineral at multiple structural scales.

Carbonation of hydroxyapatite is the primary compositional modification of bone mineral, and changes in percent carbonation are associated with changes in tissue location, age, maturity, and disease [39]. In addition to compositional changes, altered mineral orientation and crystallinity dictate mechanical properties [39–41], especially ductility [42]. Crystallinity is influenced by multiple factors including collagen (the scaffold in and around which crystallites form) and non-collagenous proteins (which provide nucleation sites for crystallite formation) [39]. Crystallinity, as measured via Raman spectroscopy, can be defined as the inverse of full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the 960 cm−1 phosphate (v1) peak, indicating more stoichiometric hydroxyapatite, or less carbonate substitutions with an increase in crystallinity. The phosphate peak can be compared to the carbonate peak at 1070 cm−1 to give a direct carbonate-to-phosphate ratio [43]. Additionally, crystallinity measured via FTIR can be described as the ratio of the 1020/1030 cm−1 bands and indicates crystal size, perfection, and maturation [44]. On a smaller scale than Raman or FTIR, qBEI can assess mineral nano-structure and distribution of spatial changes in mineral [45–47].

Understanding the crystalline phase of bone, including structure, composition, size, and orientation, is important for understanding mechanical function as well as cellular function. Cellular control of bone crystallinity is regulated by non-collagenous proteins such as biglycan [40] or fibrillin [48], or by upstream mechanical means, such as exercise [40,49,50]. Mechanical function measured by nanoindentation can be colocalized with compositional techniques such as Raman [51], or FT-IR. Nanoindentation has utility for measuring site-specific mechanical properties (hardness and Young’s modulus) of bone as well as teeth [52] and can be performed on hydrated or dehydrated specimens and also coupled with fluorescence microscopy [30,53,54]. Atomic force microscopy (AFM) can be coupled with infrared spectroscopy (AFM-IR) to provide nanometer scale resolution in collagen topography and composition, mineral composition and ratios of mineral to collagen [55]. Sequential analysis of mineral composition and tissue level mechanical properties [56] allows for non-destructive mechanical and compositional measures at micron scales across bone or skeletal locations. Combining techniques such as these to investigate effects of genetic alterations on bone composition and mechanics will advance understanding of the local cellular influence on composition and, structure, and ultimately function.

5.1. Genetic Manipulations of Bone Composition and Structure

Identifying the cellular and genetic drivers for compositional and structural changes is crucial to understand why bone mechanics are altered in different pathologies. Technological advances in biology, most notably, Clustered Regularly Interspaced Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR)/CRISPR-associated protein (Cas) pathway (CRISPR/Cas9) [57] and transgenic Cre lines [58] allow for precise genetic manipulation. When coupled with compositional, structural, and mechanical characterization, researchers would have the tools to model skeletal phenotype from genotypic information. Using these technologies to generate mouse or other animal models which mirror human mutations opens the door to investigating specific skeletal phenotypes present in a clinical setting [59].

Mechanical phenotyping the skeleton of genetic knockouts allows for unbiased screening to identify new drivers or confirm those previously found. Databases like the Origins of Bone and Cartilage Disease collaboration project (OBCD, http://www.boneandcartilage.com) correlate genetic regulation to bulk bone mechanical properties and mineralization information. This approach identified genetic mutations that had strong influence over mechanical properties [60]. This work has also highlighted dimorphisms in bone volume, size and weight by both sex and site [61]. Further investigating these skeletal phenotypes at a compositional and structural level may provide insight into how bone mechanics is impacted by specific mutations. For example, an analysis of a Smad3 (a mediator of TGF-beta signalling in bone) knockout was conducted using several compositional (Raman, X-ray tomography), structural, and mechanical (nanoindentation, three-point bending) techniques. With these methods, mineral content, cortical thickness and fracture toughness were most controlled by the Smad3 gene [62]. Often, genetic animal models investigate only bulk mechanics or mineralization, but do not attribute how the genetic regulators are affecting compositional changes. By using techniques to dissect the compositional changes in bone, including recently developed techniques highlighted in this review, it may be possible to model how specific genes are regulate the structure-function relationships in bone.

6.1. Summary

Biomechanics is at an exciting interface between classic mechanics, state of the art technology to characterize bone structure and composition at the micro- and nano-scales, and molecular tools to generate knockouts of virtually any gene. Future compositional analysis should be directed so that mineral, collagen, and structural parameters can be incorporated into simulated models of bone function. With technological advances, the ability to determine the biological drivers of structural and functional changes in bone becomes possible. Translation of clinical phenotypes to relevant animal models to better understand pathologies in human populations is a critical goal. Likewise, technologies used to characterize quality of bone should be pushed towards clinical translation with minimally invasive measures of bone architecture, mineral quantity, and tissue quality, that when combined with simulated models of bone mechanics, can be used to predict function and identify subjects at increased risk for fragility fractures.

7.1. Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health T32 DE007057–43, F30 DE028167–01A1, R01 AR065424. The authors have no declarations of interest.

Footnotes

Declarations of interest:none.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Morgan W Bolger, Biomedical Engineering, College of Engineering, University of Michigan, MI, USA.

Genevieve E Romanowicz, Department of Biologic and Materials Sciences, School of Dentistry, University of Michigan, MI, USA.

David H Kohn, Department of Biologic and Materials Sciences, School of Dentistry, University of Michigan, MI, USA; Biomedical Engineering, College of Engineering, University of Michigan, MI, USA 1011 N. University Ave, Room 2213, Ann Arbor, MI, 48109-1078 USA.

References

- [1].Beaupied H, Lespessailles E, Benhamou C-L, Evaluation of macrostructural bone biomechanics, Joint Bone Spine. 74 (2007) 233–239. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2007.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Ritchie RO, Koester KJ, Ionova S, Yao W, Lane NE, Ager JW, Measurement of the toughness of bone: a tutorial with special reference to small animal studies, Bone. 43 (2008) 798–812. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2008.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Rajapakse CS, Kobe EA, Batzdorf AS, Hast MW, Wehrli FW, Accuracy of MRI-based finite element assessment of distal tibia compared to mechanical testing, Bone. 108 (2018) 71–78. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2017.12.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Yang L, Kang M, He R, Meng B, Pal A, Chen L, Jheon AH, Ho SP, Microanatomical changes and biomolecular expression at the PDL-entheses during experimental tooth movement, J. Periodontal Res 54 (2019) 251–258. doi: 10.1111/jre.12625.** This study was unique in that the authors correlated in situ forces experienced by a loaded tooth (molar) with biochemical changes as measured at the histological level. Thus correlating explicit forces to bone formation and resorption via gene expression.

- [5].Costa MC, Tozzi G, Cristofolini L, Danesi V, Viceconti M, Dall’Ara E, Micro Finite Element models of the vertebral body: Validation of local displacement predictions, PloS One. 12 (2017) e0180151. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0180151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Duan S, Zhang L, Lin C, Zhong H, Finite Element Modeling of Atlantoaxial Joint with the Vertebral Artery Based on CT Data, in: Atlantis Press, 2016. doi: 10.2991/meici-16.2016.101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Hammond MA, Wallace JM, Allen MR, Siegmund T, Mechanics of linear microcracking in trabecular bone, J. Biomech 83 (2019) 34–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2018.11.018.** Finite element analysis of single trabeculae or a scanned, cadaveric trabecular core demonstrated that tissue composition and anisotropy was a determinant in microcrack formation.

- [8].Parfitt AM, Mathews CH, Villanueva AR, Kleerekoper M, Frame B, Rao DS, Relationships between surface, volume, and thickness of iliac trabecular bone in aging and in osteoporosis. Implications for the microanatomic and cellular mechanisms of bone loss., J. Clin. Invest 72 (1983) 1396–1409. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC370424/ (accessed April 24, 2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Hahn M, Vogel M, Pompesius-Kempa M, Delling G, Trabecular bone pattern factor--a new parameter for simple quantification of bone microarchitecture, Bone. 13 (1992) 327–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Gregg CL, Recknagel AK, Butcher JT, Micro/nano-computed tomography technology for quantitative dynamic, multi-scale imaging of morphogenesis, Methods Mol. Biol. Clifton NJ 1189 (2015) 47–61. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-1164-6_4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Bakalova LP, Andreasen CM, Thomsen JS, Brüel A, Hauge E-M, Kiil BJ, Delaisse J-M, Andersen TL, Kersh ME, Intracortical Bone Mechanics Are Related to Pore Morphology and Remodeling in Human Bone, J. Bone Miner. Res 33 (2018) 2177–2185. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.3561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Campbell GM, Peña JA, Giravent S, Thomsen F, Damm T, Glüer C-C, Borggrefe J, Assessment of Bone Fragility in Patients With Multiple Myeloma Using QCT-Based Finite Element Modeling, J. Bone Miner. Res. Off. J. Am. Soc. Bone Miner. Res 32 (2017) 151–156. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Bigelow EM, Patton DM, Ward FS, Ciarelli A, Casden M, Clark A, Goulet RW, Morris MD, Schlecht SH, Mandair GS, Bredbenner TL, Kohn DH, Jepsen KJ, External Bone Size Is a Key Determinant of Strength-Decline Trajectories of Aging Male Radii, J. Bone Miner. Res 0 (n.d.) e3661. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.3661.** This study investigated structural differences among subsets of the human population that drive mechanical phenotypes as segregated by differences in external bone size. Also developed a technique to characterize porosity as a measure of pore size and distance to cross section centroid.

- [14].Pazzaglia UE, Congiu T, The cast imaging of the osteon lacunar-canalicular system and the implications with functional models of intracanalicular flow, J. Anat 222 (2013) 193–202. doi: 10.1111/joa.12004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Lampi T, Dekker H, Bruggenkate CMT, Schulten EAJM, Mikkonen JJW, Koistinen A, Kullaa AM, Acid-etching technique of non-decalcified bone samples for visualizing osteocyte-lacuno-canalicular network using scanning electron microscope, Ultrastruct. Pathol 42 (2018) 74–79. doi: 10.1080/01913123.2017.1384418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Kerschnitzki M, Wagermaier W, Roschger P, Seto J, Shahar R, Duda GN, Mundlos S, Fratzl P, The organization of the osteocyte network mirrors the extracellular matrix orientation in bone, J. Struct. Biol 173 (2011) 303–311. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2010.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Kerschnitzki M, Kollmannsberger P, Burghammer M, Duda GN, Weinkamer R, Wagermaier W, Fratzl P, Architecture of the osteocyte network correlates with bone material quality, J. Bone Miner. Res 28 (2013) 1837–1845. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Genthial R, Beaurepaire E, Schanne-Klein M-C, Peyrin F, Farlay D, Olivier C, Bala Y, Boivin G, Vial J-C, Débarre D, Gourrier A, Label-free imaging of bone multiscale porosity and interfaces using third-harmonic generation microscopy, Sci. Rep 7 (2017). doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-03548-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Genthial R, Gerbaix M, Farlay D, Vico L, Beaurepaire E, Débarre D, Gourrier A, Third harmonic generation imaging and analysis of the effect of low gravity on the lacuno-canalicular network of mouse bone, PLOS ONE. 14 (2019) e0209079. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0209079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Zuluaga MA, Orkisz M, Dong P, Pacureanu A, Gouttenoire P-J, Peyrin F, Bone canalicular network segmentation in 3D nano-CT images through geodesic voting and image tessellation, Phys. Med. Biol 59 (2014) 2155–2171. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/59/9/2155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Ciani A, Toumi H, Pallu S, Tsai EHR, Diaz A, Guizar-Sicairos M, Holler M, Lespessailles E, Kewish CM, Ptychographic X-ray CT characterization of the osteocyte lacuno-canalicular network in a male rat’s glucocorticoid induced osteoporosis model, Bone Rep. 9 (2018) 122–131. doi: 10.1016/j.bonr.2018.07.005.* Novel use of PXCT to non-destructively visualize the OLCN, and demonstrated alterations to the network and lacunae shape with osteoporosis.

- [22].Varga P, Hesse B, Langer M, Schrof S, Männicke N, Suhonen H, Pacureanu A, Pahr D, Peyrin F, Raum K, Synchrotron X-ray phase nano-tomography-based analysis of the lacunar–canalicular network morphology and its relation to the strains experienced by osteocytes in situ as predicted by case-specific finite element analysis, Biomech. Model. Mechanobiol 14 (2015) 267–282. doi: 10.1007/s10237-014-0601-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Buenzli PR, Sims NA, Quantifying the osteocyte network in the human skeleton, Bone. 75 (2015) 144–150. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2015.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Kollmannsberger P, Kerschnitzki M, Repp F, Wagermaier W, Weinkamer R, Fratzl P, The small world of osteocytes: connectomics of the lacuno-canalicular network in bone, New J. Phys 19 (2017) 073019. doi: 10.1088/1367-2630/aa764b.* Development of a framework to quantitatively characterize the architecture of the osteocyte lacuno-canalicular network, applying theory of complex networks to bone samples from mice and sheep.

- [25].McNerny EMB, Gong B, Morris MD, Kohn DH, Bone fracture toughness and strength correlate with collagen cross-link maturity in a dose-controlled lathyrism mouse model, J. Bone Miner. Res. Off. J. Am. Soc. Bone Miner. Res 30 (2015) 455–464. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Gineyts E, Borel O, Chapurlat R, Garnero P, Quantification of immature and mature collagen crosslinks by liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization mass spectrometry in connective tissues, J. Chromatogr. B Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life. Sci 878 (2010) 1449–1454. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2010.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Naffa R, Holmes G, Ahn M, Harding D, Norris G, Liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization mass spectrometry for the simultaneous quantitation of collagen and elastin crosslinks, J. Chromatogr. A 1478 (2016) 60–67. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2016.11.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Naffa R, Watanabe S, Zhang W, Maidment C, Singh P, Chamber P, Matyska MT, Pesek JJ, Rapid analysis of pyridinoline and deoxypyridinoline in biological samples by liquid chromatography with mass spectrometry and a silica hydride column, J. Sep. Sci 0 (n.d.). doi: 10.1002/jssc.201801292.* The authors, developed and verified a mass spectrometry friendly technique to rapidly detect mature enzymatic cross-links found in bone.

- [29].Fujino Y, Minamizaki T, Yoshioka H, Okada M, Yoshiko Y, Imaging and mapping of mouse bone using MALDI-imaging mass spectrometry, Bone Rep. 5 (2016) 280–285. doi: 10.1016/j.bonr.2016.09.004.** This study provides novel insight into imaging of proteins in situ using mass spectroscopy, as well as thorough detailing of the methods to obtain this information from bone. This technique had not been previously explored and has not been widely used by the field to date.

- [30].McNerny EMB, Gardinier JD, Kohn DH, Exercise increases pyridinoline cross-linking and counters the mechanical effects of concurrent lathyrogenic treatment, Bone. 81 (2015) 327–337. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2015.07.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Depalle B, Qin Z, Shefelbine SJ, Buehler MJ, Influence of cross-link structure, density and mechanical properties in the mesoscale deformation mechanisms of collagen fibrils, J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater 52 (2015) 1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2014.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Depalle B, Duarte AG, Fiedler IAK, Pujo-Menjouet L, Buehler MJ, Berteau J-P, The different distribution of enzymatic collagen cross-links found in adult and children bone result in different mechanical behavior of collagen, Bone. 110 (2018) 107–114. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2018.01.024.* This study applied experimentally measured enzymatic cross-link profile of human adult and children bones to model collagen fibrils under tension and showed that cross-link maturity, and total number of covalent bonds impacts elastic deformation.

- [33].Vashishth D, Advanced Glycation End-products and Bone Fractures, IBMS BoneKEy. 6 (2009) 268–278. doi: 10.1138/20090390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Collier TA, Nash A, Birch HL, de Leeuw NH, Intra-molecular lysine-arginine derived advanced glycation end-product cross-linking in Type I collagen: A molecular dynamics simulation study, Biophys. Chem 218 (2016) 42–46. doi: 10.1016/j.bpc.2016.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Gautieri A, Redaelli A, Buehler MJ, Vesentini S, Age- and diabetes-related nonenzymatic crosslinks in collagen fibrils: Candidate amino acids involved in Advanced Glycation End-products, Matrix Biol. 34 (2014) 89–95. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2013.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Collier TA, Nash A, Birch HL, de Leeuw NH, Effect on the mechanical properties of type I collagen of intra-molecular lysine-arginine derived advanced glycation end-product cross-linking, J. Biomech 67 (2018) 55–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2017.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Thornalley PJ, Battah S, Ahmed N, Karachalias N, Agalou S, Babaei-Jadidi R, Dawnay A, Quantitative screening of advanced glycation endproducts in cellular and extracellular proteins by tandem mass spectrometry, Biochem. J 375 (2003) 581–592. doi: 10.1042/BJ20030763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Hunt HB, Donnelly E, Bone quality assessment techniques: geometric, compositional, and mechanical characterization from macroscale to nanoscale, Clin. Rev. Bone Miner. Metab 14 (2016) 133–149. doi: 10.1007/s12018-016-9222-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Boskey Adele, Bone mineral crystal size, Osteoporos. Int. J. Establ. Result Coop. Eur. Found. Osteoporos. Natl. Osteoporos. Found. USA 14 Suppl 5 (2003) S16–20; discussion S20–21. doi: 10.1007/s00198-003-1468-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Wallace JM, Golcuk K, Morris MD, Kohn DH, Inbred strain-specific effects of exercise in wild type and biglycan deficient mice, Ann. Biomed. Eng 38 (2010) 1607–1617. doi: 10.1007/s10439-009-9881-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Wallace JM, Golcuk K, Morris MD, Kohn DH, Inbred strain-specific response to biglycan deficiency in the cortical bone of C57BL6/129 and C3H/He mice, J. Bone Miner. Res. Off. J. Am. Soc. Bone Miner. Res 24 (2009) 1002–1012. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.081259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Yerramshetty JS, Akkus O, The associations between mineral crystallinity and the mechanical properties of human cortical bone, Bone. 42 (2008) 476–482. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Morris MD, Mandair GS, Raman assessment of bone quality, Clin. Orthop 469 (2011) 2160–2169. doi: 10.1007/s11999-010-1692-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Paschalis EP, DiCarlo E, Betts F, Sherman P, Mendelsohn R, Boskey AL, FTIR microspectroscopic analysis of human osteonal bone, Calcif. Tissue Int 59 (1996) 480–487. doi: 10.1007/BF00369214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].He F, Chiou AE, Loh HC, Lynch M, Seo BR, Song YH, Lee MJ, Hoerth R, Bortel EL, Willie BM, Duda GN, Estroff LA, Masic A, Wagermaier W, Fratzl P, Fischbach C, Multiscale characterization of the mineral phase at skeletal sites of breast cancer metastasis, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 114 (2017) 10542–10547. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1708161114.** This study investigates local mineral compositional changes in the tibia which appears to “pre-destine” a site for cancer metastasis in their animal model of breast cancer.

- [46].Gardinier JD, Al-Omaishi S, Morris MD, Kohn DH, PTH signaling mediates perilacunar remodeling during exercise, Matrix Biol. J. Int. Soc. Matrix Biol 52–54 (2016) 162–175. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2016.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Gardinier JD, Al-Omaishi S, Rostami N, Morris MD, Kohn DH, Examining the influence of PTH(1–34) on tissue strength and composition, Bone. 117 (2018) 130–137. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2018.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Kavukcuoglu NB, Arteaga-Solis E, Lee-Arteaga S, Ramirez F, Mann AB, Nanomechanics and Raman spectroscopy of fibrillin 2 knock-out mouse bones, J. Mater. Sci 42 (2007) 8788–8794. doi: 10.1007/s10853-007-1918-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Hammond MA, Wallace JM, Exercise prevents β-aminopropionitrile-induced morphological changes to type I collagen in murine bone, BoneKEy Rep. 4 (2015) 645. doi: 10.1038/bonekey.2015.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Kohn DH, Sahar ND, Wallace JM, Golcuk K, Morris MD, Exercise Alters Mineral and Matrix Composition in the Absence of Adding New Bone, Cells Tissues Organs. 189 (2009) 33–37. doi: 10.1159/000151452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Raghavan M, Sahar ND, Kohn DH, Morris MD, Age-specific profiles of tissue-level composition and mechanical properties in murine cortical bone, Bone. 50 (2012) 942–953. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2011.12.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Sereda G, VanLaecken A, Turner JA, Monitoring demineralization and remineralization of human dentin by characterization of its structure with resonance-enhanced AFM-IR chemical mapping, nanoindentation, and SEM, Dent. Mater. 35 (2019) 617–626. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2019.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Sinder BP, Lloyd WR, Salemi JD, Marini JC, Caird MS, Morris MD, Kozloff KM, Effect of anti-sclerostin therapy and osteogenesis imperfecta on tissue-level properties in growing and adult mice while controlling for tissue age, Bone. 84 (2016) 222–229. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2016.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Blouin S, Fratzl-Zelman N, Roschger A, Cabral WA, Klaushofer K, Marini JC, Fratzl P, Roschger P, Cortical bone properties in the Brtl/+ mouse model of Osteogenesis imperfecta as evidenced by acoustic transmission microscopy, J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater 90 (2019) 125–132. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2018.10.010.* This study examined the mineral composition, collagen orientation, and used scanning acoustic microscopy to map and calculate Young’s modulus on a bone cross section.

- [55].Imbert L, Gourion-Arsiquaud S, Villarreal-Ramirez E, Spevak L, Taleb H, van der Meulen MCH, Mendelsohn R, Boskey AL, Dynamic structure and composition of bone investigated by nanoscale infrared spectroscopy, PloS One. 13 (2018) e0202833. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0202833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Bi X, Patil CA, Lynch CC, Pharr GM, Mahadevan-Jansen A, Nyman JS, Raman and mechanical properties correlate at whole bone- and tissue-levels in a genetic mouse model, J. Biomech 44 (2011) 297–303. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2010.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Williams BO, Warman ML, Perspective: CRISPR/Cas9 technologies, J. Bone Miner. Res. Off. J. Am. Soc. Bone Miner. Res 32 (2017) 883–888. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.3086.* This review thoroughly highlights the use of genetic manipulation of mouse models to study the effects in bone.

- [58].Dallas SL, Xie Y, Shiflett LA, Ueki Y, Mouse Cre Models for the Study of Bone Diseases, Curr. Osteoporos. Rep 16 (2018) 466–477. doi: 10.1007/s11914-018-0455-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Schrauwen I, Giese AP, Aziz A, Lafont DT, Chakchouk I, Santos-Cortez RLP, Lee K, Acharya A, Khan FS, Ullah A, Nickerson DA, Bamshad MJ, Ali G, Riazuddin S, Ansar M, Ahmad W, Ahmed ZM, Leal SM, FAM92A Underlies Nonsyndromic Postaxial Polydactyly in Humans and an Abnormal Limb and Digit Skeletal Phenotype in Mice, J. Bone Miner. Res. Off. J. Am. Soc. Bone Miner. Res 34 (2019) 375–386. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.3594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Bassett JHD, Gogakos A, White JK, Evans H, Jacques RM, van der Spek AH, Project SMG, Ramirez-Solis R, Ryder E, Sunter D, Boyde A, Campbell MJ, Croucher PI, Williams GR, Rapid-Throughput Skeletal Phenotyping of 100 Knockout Mice Identifies 9 New Genes That Determine Bone Strength, PLOS Genet. 8 (2012) e1002858. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Rowe DW, Adams DJ, Hong S-H, Zhang C, Shin D-G, Renata Rydzik C, Chen L, Wu Z, Garland G, Godfrey DA, Sundberg JP, Ackert-Bicknell C, Screening Gene Knockout Mice for Variation in Bone Mass: Analysis by μCT and Histomorphometry, Curr. Osteoporos. Rep 16 (2018) 77–94. doi: 10.1007/s11914-018-0421-4.* This study highlights the high-throughput screening of multiple genetic knockouts for detailed characterization of bone phenotype using microCT and bone turnover.

- [62].Balooch G, Balooch M, Nalla RK, Schilling S, Filvaroff EH, Marshall GW, Marshall SJ, Ritchie RO, Derynck R, Alliston T, TGF-beta regulates the mechanical properties and composition of bone matrix, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 102 (2005) 18813–18818. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507417102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Saito M, Marumo K, Collagen cross-links as a determinant of bone quality: a possible explanation for bone fragility in aging, osteoporosis, and diabetes mellitus, Osteoporos. Int. J. Establ. Result Coop. Eur. Found. Osteoporos. Natl. Osteoporos. Found. USA 21 (2010) 195–214. doi: 10.1007/s00198-009-1066-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]