Highlights

-

•

472 COVID-19 cases and 70 deaths per 100,000 UK population as of 12th Aug 2020.

-

•

Majority of deaths from COVID-19 were amongst people aged ≥60 years.

-

•

COVID-19 mortality was higher in Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) groups.

-

•

Emergency department attendance and patient referrals have declined.

-

•

Emergency ambulance and non-urgent (NHS111) calls have increased.

Keywords: United Kingdom, COVID-19, Epidemiology, Health system impact, Economic impact, Technological response

Abstract

Objectives

To describe epidemiological data on cases of COVID-19 and the spread of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 in the United Kingdom (UK), and the subsequent policy and technological response to the pandemic, including impact on healthcare, business and the economy.

Methods

Epidemiological, business and economic data were extracted from official government sources covering the period 31st January to 13th August 2020; healthcare system data up to end of June 2019.

Results

UK-wide COVID-19 cases and deaths were 313,798 and 46,706 respectively (472 cases and 70 deaths per 100,000 population) by 12th August. There were regional variations in England, with London and North West (756 and 666 cases per 100,000 population respectively) disproportionately affected compared with other regions. As of 11th August, 13,618,470 tests had been conducted in the UK. Increased risk of mortality was associated with age (≥60 years), gender (male) and BAME groups. Since onset of the pandemic, emergency department attendance, primary care utilisation and cancer referrals and inpatient/outpatient referrals have declined; emergency ambulance and NHS111 calls increased. Business sectors most impacted are the arts, entertainment and recreation, followed by accommodation and food services. Government interventions aimed at curtailing the business and economic impact have been implemented, but applications for state benefits have increased.

Conclusions

The impact of COVID-19 on the UK population, health system and economy has been profound. More data are needed to implement the optimal policy and technological responses to preventing further spikes in COVID-19 cases, and to inform strategic planning to manage future pandemics.

Introduction

The first identified cases of COVID-19, caused by the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), in the United Kingdom (UK) were reported in late January 2020, with person-to-person transmission within the country confirmed by late February. COVID-19 cases subsequently increased exponentially, and a host of measures have been rapidly implemented to decelerate the spread of SARS-CoV-2 (‘flattening the curve’) to reduce the impact on the healthcare system, including social distancing, self-isolation and lockdown strategies. Financial interventions were rapidly introduced to protect the UK economy. In this report, we aim to describe the epidemiological data on COVID-19 observed in the UK population and the policy response to the pandemic, including impact on the healthcare system, business and economic activity.

Section 1.1 presents a sociodemographic profile of the UK (population figures, population density, life expectancy and household composition). Section 1.2 describes key health indicators in the UK (health behaviours and socio-demographic factors, and mental health as important contextual information to help with evaluating the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on individuals and the health care system). Data definitions and data sources used in subsequent sections of the paper are described in Section 2. Section 3 reports on epidemiological data for COVID-19 to highlight trends in the spread of SARS-CoV-2 across the UK: lab-confirmed cases of COVID-19 and deaths (Section 3.1), testing data for COVID-19 (Section 3.2), and daily hospitalisation, type of admission, treatment modality and recovery rates (Section 3.3). Characteristics of COVID-19 related deaths are presented in Section 4. In Section 5, we present a timeline and description of the policies and technologies introduced by the UK government in response to the pandemic. Available data on the impact of COVID-19 on health care utilisation are then presented in Section 6, followed by the impact on business and economic activity in Section 7. Other spillover effects of the pandemic on the environment, crime rates, and the sale and consumption of alcohol are also discussed in Section 7. The data for this paper focuses on the period 31st January up to 13th August 2020 (where data are available), with healthcare system data up to end June 2019.

Sociodemographic profile of the UK

With a population of 67.8 million, the UK is the third largest country in Europe, and 21st largest worldwide [1]. Population projections indicate that the UK population will surpass 70 million by 2029 and will reach approximately 73 million by 2041 [2]. Migration, and an ageing population are major contributors to UK population growth [2]. The UK is one of the most densely populated countries in Europe, and the 32nd most densely populated worldwide, with 281 individuals per km2 [1]. Population density is expected to increase in proportion with projections for population growth.

The life expectancy at birth, when both sexes are combined, is 81.8 years (83.3 years for females and 80.2 years for males). Currently, approximately 18% of the UK population are aged ≥ 65. In 2019 there were 8.2 million people in the UK living alone, 2.9 million lone parent families and 19.2 million families (i.e. cohabiting couples with or without children residing at the same address) [3]. Approximately 4% of peole aged over 65 years live in care homes, which increases to 18% for people aged over 85 years [4].

Health indicators in the UK

It is important to present information on key health indicators of the UK population as the World Health Organization (WHO) highlighted that non-communicable diseases are high-risk factors for a poor prognosis after contracting SARS-CoV-2 [5].

Health behaviours (dietary excess and sub-optimal nutrition, excessive alcohol intake and physical inactivity) and socio-demographic factors such as deprivation, contribute to 63% of the UK population being either overweight (body mass index [BMI] 25–29.9) or obese (BMI ≥30), with the highest rates of morbid obesity (BMI ≥40) recorded in more deprived groups in the UK [6]. Obesity, and associated increased risk of long-term health conditions have been identified as risk factors for a poor prognosis from COVID-19 [5], [6], [7], including type 2 diabetes (UK prevalence 3.9 million) [8], heart and circulatory disease (UK prevalence 7.2 million) [9], hypertension (12.5 million) and cancer [10], including a strong link with mental health conditions [11].

Based on data from Cancer Research UK, 15% of UK adults smoke cigarettes, which equates to an estimated 7.2 million individuals [12]. A 2019 report indicated that 489,000 hospital admissions in the previous year were attributable to smoking, with 78,000 attributable deaths [13]. The equivalent figures related to alcohol use were 358,000 hospital admissions, and 5698 alcohol-specific deaths [14]. Physical inactivity is increasing in prevalence. The UK is 20% less active than in the 1960s and if this trend continues, will be 35% less active by 2030 [15]. Physical inactivity is estimated to be responsible for one in six UK deaths at a cost of £0.9 billion to the NHS annually [16].

A further consideration is the existing prevalence of mental health conditions amongst the UK population. There are few UK-level epidemiological data on mental health. In England, the economic and social cost of mental health is £105 billion per year (£34 billion on mental health support and services), with 1 in 4 people experiencing a mental health issue each year; with 9 out of 10 managed exclusively in primary care [17]. The majority (1 in 6 adults aged ≥ 16 years) report symptoms consistent with a common mental health disorder (CMHD) that include a range of anxiety and depressive disorders [18]. Prevalence of CMHDs is greater in females than males across all age categories (maximal gender disparity in those aged 16 to 24 years); people identifying as Black or Black British; and those who are unemployed/economically inactive [19].

Overview of the healthcare system in the UK

The UK healthcare system consists of both public and private providers, with 13% of UK consumers also paying for private medical insurance [20]. All permanent residents of the UK are entitled to free health care by the National Health Service (NHS), which is paid for through direct taxation. The NHS in the UK is composed of four separate systems, serving each devolved country that constitutes the UK: England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. Although there is policy divergence between these health systems, we do not draw any links between data trends for COVID-19 and the way in which care is delivered in each devolved country.

Data on health care expenditure available from the Office of National Statistics (2017) show that total expenditure across the four individual healthcare systems in the UK was £197.4 billion, equating to £2,989 per person (9.6% of gross domestic product [GDP]) [21]. Spending by the NHS and other public providers accounts for 79% of total health care expenditure, with the remainder financed through a mix of private insurance, charitable financing, enterprise financing and out-of-pocket expenditure [22]. The UK presents an interesting case study of the financial and performance impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on a health care service, given the large percentage of the population that is reliant on publicly funded healthcare provided by the NHS.

Methods

Data definitions

The case definition of COVID-19 in the UK is people who require admission to hospital and have clinical or radiological evidence of pneumonia, acute reparatory distress syndrome or display influenza-like symptoms. People with symptoms of a new continuous cough and/or high temperature [22] were advised to self-isolate. This was later updated on 18th May to include anosmia (loss of taste or smell) based on a study reported in Nature Medicine [23]. The phased testing programme in the UK consists of the following 4 pillars – Box 1:

There are differences in registration of dates of deaths to actual deaths across the devolved countries in the UK [25] – these are summarised in Table 1 . The National Records of Scotland, Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency, and Office of National Statistics (for England and Wales) have provided information on the number of community-based COVID-19 deaths by reporting registrations of COVID-19 on death certificates or respiratory infection deaths.

Table 1.

Criteria for registering COVID-19 deaths across the UK [25].

| England | Scotland | Wales | Northern Ireland |

|---|---|---|---|

| People who are confirmed positive with COVID-19 by date of death (no cut-off date). This was amended on 12th Aug to people who died within 28 days of their first positive test result Prior to 29th April, deaths were reported by NHS England and only included those in NHS-commissioned services of patients who have tested positively for COVID-19. After 29th April, this included deaths in care homes and in the community. |

People who died within 28 days of their first positive test result |

People who died within 28 days of their first positive test result |

People who died within 28 days of their first positive test result |

In order to obtain an overview on the spread of SARS-CoV-2 in the UK, we report on the trends of lab-confirmed cases of COVID-19 and deaths at per 100,000 population level, as well as a function of gender, age and comorbidities, where data are available.

Data for England were the most comprehensive with data available on emergency department (ED) attendances, hospital admission from ED, emergency medical service calls, and urgent care telephone support (named NHS111), including primary care activity up to the end of June 2020. Data were also available for cancer referrals up to the end of May 2020. NHS111 is an urgent care telephone number that the public were instructed to contact in the first instance if they were experiencing symptoms, rather than contacting their general practitioner. Comparable data were not available for Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales for this same time period.

Data sources

Information relating to COVID-19 in the UK is collected and distributed by several government agencies: The National Health Service (NHS), Office for National Statistics, Department of Health and Social Care, and the New and Emerging Respiratory Virus Threats Advisory Group. The daily number of lab-confirmed cases of COVID-19, testing information and COVID-19 linked hospital deaths are released by the UK Government [26] to the public via a dedicated webpage, media releases and social media. This information is collated by the UK government from the devolved countries of England, Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales.

Data were manually collected from the UK, Scotland and Wales COVID-19 dashboards [27], [28], [29], as well as the Office of National Statistics and media releases from the chief medical officer of the respective administrations. For Northern Ireland [30], COVID-19 epidemiology and linked information was provided through situation reports until the 19th of April before converting to media releases and subsequently to a dashboard.

Across all the devolved countries in the UK the data released varies, likely a result of reporting lags, the number of agencies involved in collating the information, and the result of resourcing and technology challenges – see Table 2 . In addition, due to reporting errors in the pillar 2 cases for England, on 2nd July Public Health England removed the duplicate confirmed cases from England's confirmed statistics [27]. From 2nd July, the number of pillar 2 cases are not accounted for in the national totals for England, Northern Ireland and Scotland [27]. It is because of this adjustment that the number of confirmed cases drops on 2nd July.

Table 2.

Data recorded for COVID-19 cases across the UK.

| England | Scotland | Wales | Northern Ireland |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of people in hospital with COVID-19 Gender and age of COVID-19 related hospital deaths Wider data on the English health system were obtained from publicly reported NHS data [31] |

Number of people in hospital with COVID-19 | Number of people in hospital with COVID-19 Gender and age of people with COVID-19 |

Number of people in hospital with COVID-19 |

A categorisation system for the policy, technological and other interventions in response to the COVID-19 pandemic by the UK government was developed by Moy et al. [32]. This was used to design a graphical roadmap to show the timeline for the implementation of different categories of responses to the pandemic in the UK.

Information published on the Gov.uk website was used to inform the summaries of the UK government's financial interventions. Data from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) Business Impact of Coronavirus Survey (BICS) were used to describe impact on businesses, trading (import and exports), interest rates and GDP. Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) data were used to report numbers of people applying for state benefits (Universal Credit).

COVID-19 trends

Daily trends in lab-confirmed cases of COVID-19 and deaths

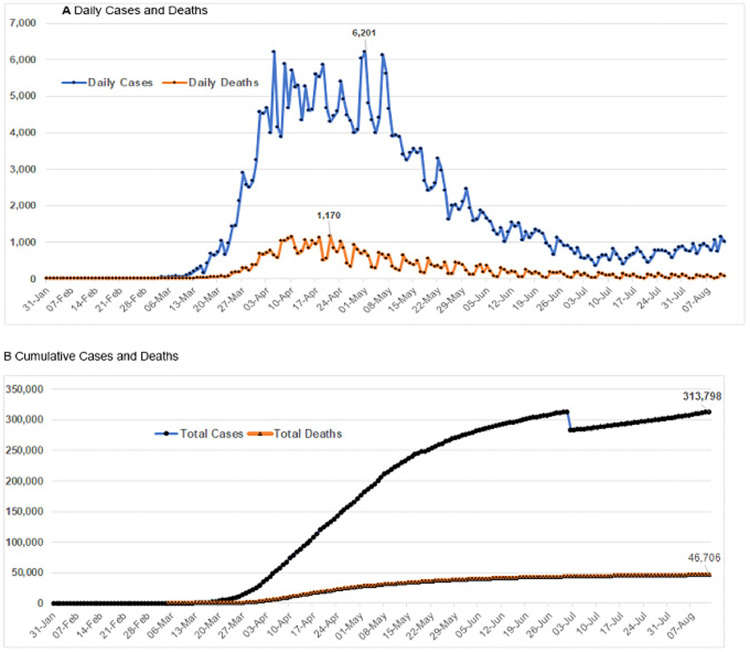

Absolute numbers of daily and cumulative lab-confirmed cases and deaths over time in the UK are shown in Fig. 1 .

Fig. 1.

Time series graphs of daily and cumulative lab-confirmed cases of COVID-19 and deaths.

The number of daily cases exceeded three figures at 21st March, which peaked on 1st May (with the peak in deaths occurring on 21st April). UK-wide COVID-19 cases were 313,798 by 12th August, and overall deaths were 46,706. The proportion of deaths-to-cases for the UK (deaths / lab-confirmed cases) up to 12th August was 15%.

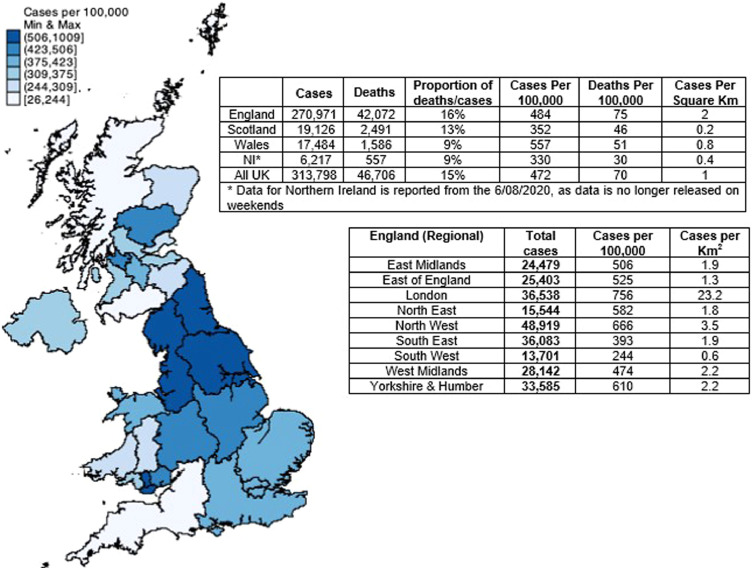

Population data on the spread of lab-confirmed cases and deaths across the UK (devolved countries) and regions in England are shown in Fig. 2 . Up to 12th August there were 472 cases and 70 deaths per 100,000 population in the UK. The number of cases was maximal in England, although cases per 100,000 population was highest in Wales. The proportion of deaths-to-cases of COVID-19 is most pronounced in England (16%) with 75 deaths per 100,000 population, followed in descending order by Scotland (13%) with 352 deaths per 100,000 population. Wales and Northern Ireland both reported a proportion of deaths-to-cases of 9%; although Wales had more deaths per 100,000 population than Scotland [27]. Between 10th April to 7th August June 10th, 14,120 deaths in England were reported in care homes [33].

Fig. 2.

COVID-19 cases and deaths (up to 12th August 2020) across the UK and regions in England

Regional data for England shows that lab-confirmed cases are maximal in the north west, followed by London and the south east. However, in terms of case density per 100,000 population and cases per Km2, London and the north west had been disproportionately affected by COVID-19.

There are limited data available on symptomatic cases in the community. The advice given to those with suspected mild symptoms of COVID-19 (new continuous cough, fever or anosmia) was for individuals and all members of their households to self-isolate for 7 days and 14 days respectively, and call NHS111 if required. Those with persistent and severe symptoms were advised to contact their general practitioner (GP) or call emergency services (see Section 6). On the 18th May the NHS Testing and Tracing Service was launched, whereby anyone in the UK with symptoms can request an antigen test via a dedicated website [35]. The aspiration was for the NHS COVID-19 App to be part of the NHS Testing and Tracing Service, but it had not been implemented at the time of writing.

The COVID Symptom Tracker (developed by the health science company ZOE Global Ltd and endorsed by the Welsh Government, NHS Wales, the Scottish Government and NHS Scotland) since March 29th has reported modelled data on symptomatic cases of COVID-19 in the UK. Data are collected on a voluntary basis from the general public via an App (users take 1-min to report their health daily, even if they are well) and is analysed by King's College London & ZOE research teams to predict and track COVID-19 infections across the UK [36]) It indicated that the peak of symptomatic cases in the UK occurred on the 1st April (~2.2 million / 67.8 million = 3.24% of the total UK population) that dropped to 22,683 on 12th August.

Testing for COVID-19

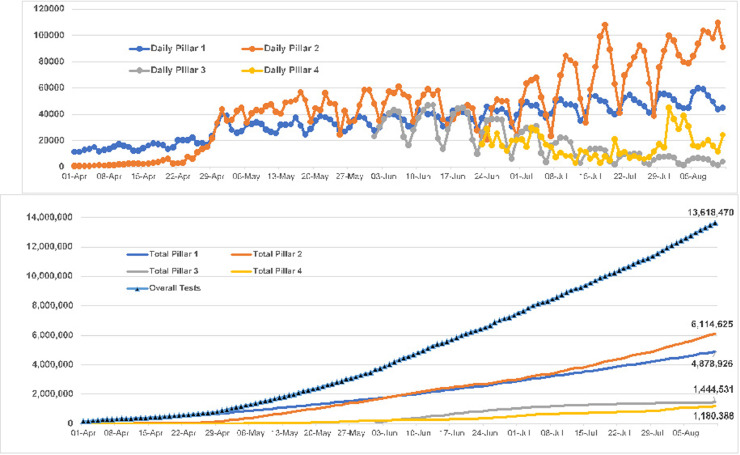

Absolute numbers of daily testing (Pillars 1, 2, 3 and 4) in the UK over time are shown in Fig. 3 . As of 11th August 2020, 13,618,470 tests had been conducted in the UK.

Fig. 3.

Daily and total number of tests in the UK.

Testing (Pillar 1 - NHS swab testing for those with a medical need and, where possible, the most critical key workers) steadily increased from ~10,000 per day in early April to approximately 20,000 per day at the end of April. During May to June they fluctuated between 30,000 and 50,000 per day – culminating in 4,878,926 on 11th August.

Reporting of mass-swab testing by commercial partners for the wider population, as defined by the government as additional key workers such as NHS community workers, was slow to gain pace (between 28th March and 8th April daily tests were below 1000), which increased to over 10,000 per day on the 27th April. Thereafter, there was an exponential increase (with some periodic declines) up to a peak of 109,488 on 10th August. On the 11th August 6,114,625 Pillar 2 tests had been conducted.

Starting in early June, mass-antibody testing to help determine if people have immunity to coronavirus commenced, with day on day increases from 2nd June to 7th June. Thereafter, day on day numbers declined successfully over 7-day periods, dropping to 1,720 on the 20th July. Overall, on the 11th August, 1,444,531 Pillar 3 tests had been undertaken.

Pillar 4 (surveillance testing to help develop new tests and treatments) commenced being recorded in early April 2020 and daily tests per day increased up to 4th July 29th April, followed by a decline up to 19th July and a subsequent increase during the remainder of July (and a decline in early Aug). On the 11th August 1,180,388 Pillar 4 tests had been undertaken.

Daily hospitalisation, type of admission, treatment modality and recovery rates

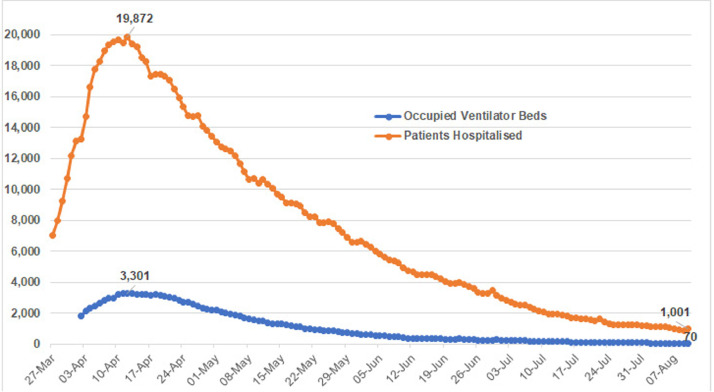

The numbers of patients in hospital with COVID-19 and occupying ventilator beds were both maximal on the 13th April (19,872 and 3,301 respectively) with a steady decline thereafter across the remainder of April and May, culminating in 1,001 and 70 respectively on the 10th Aug 2020 (Fig. 4 ).

Fig. 4.

Number of hospitalisations and ventilator bed occupation in the UK.

Up to 4pm on the 23rd July 2020, the Intensive Care National Audit and Research Centre (ICNARC) Case Mix Programme Database [6] had data on 10,557 patients within 24 h of critical care with confirmed COVID-19 in England, Wales and Northern Ireland (critical care units in Scotland do not contribute to ICNARC case mix programme). Out of 10,271 patients, 6,037 (58.8%) were mechanically ventilated within the first 24 h of admission.

Out of 10,228 patients with outcomes, 6,150 (60.1%) survived and were discharged. There were 7355 (72.2%) patients who received advanced respiratory support (invasive ventilation, Bilevel Positive Airway Pressure via trans-laryngeal tube or tracheostomy, continuous positive airway pressure via trans-laryngeal tube, extracorporeal respiratory support). Approximately a third (n = 3,054, 30%) received advanced cardiovascular support (multiple IV/rhythm controlling drugs [at least one vasoactive], continuous observation of cardiac output, intra-aortic balloon pump, temporary cardiac pacemaker). Approximately a quarter (n = 2,707, 26.6%) received renal support (acute renal replacement therapy, renal replacement therapy for chronic renal failure where other organ support is received). Relatively few (n = 104, 1%) received liver support (management of coagulopathy and/or portal hypertension for acute on chronic hepatocellular failure or primary acute hepatocellular failure). Finally, 899 (8.9%) received neurological support (central nervous system depression sufficient to prejudice airway, invasive neurological monitoring, continuous IV medication to control seizures, therapeutic hypothermia).

Characteristics of COVID-19 related deaths

Combined UK figures were not available at the time of writing. Figures reported by the four devolved countries in the UK showed that highest proportions of deaths were amongst older adults. As of 13th August 2020, in England ~91% of deaths in hospital from COVID-19 were amongst people aged ≥60 years [37] (Table 3 ). In Scotland, as of 12th August 2020, ~76% of deaths were in people aged ≥75 [38] (Table 4 ). In Northern Ireland, as of 31st July 2020, ~80% of deaths were observed in people aged ≥75 years [39] (Table 5 ). In Wales, as of 31st July 2020, ~90% of deaths associated with COVID-19 were observed in those over the age of 65 [29] (Table 6 ).

Table 3.

Covid-19 deaths in England according to age group.

| Age groups (Years) | Number of deaths | Percentage of total deaths |

|---|---|---|

| 0–19 | 20 | 0.07 |

| 20–39 | 212 | 0.72 |

| 40–59 | 2,288 | 7.77 |

| 60–79 | 11,194 | 38.02 |

| 80+ | 15,730 | 53.42 |

| Total | 29,444 | 100 |

Table 4.

Covid-19 deaths in Scotland according to age group.

| Age groups (Years) | Number of deaths | Percentage of total deaths |

|---|---|---|

| <1 | 0 | 0.00 |

| 1–14 | 0 | 0.00 |

| 15–44 | 28 | 0.66 |

| 45–64 | 348 | 8.26 |

| 65–74 | 602 | 14.29 |

| 75–84 | 1,411 | 33.49 |

| 85+ | 1,824 | 43.29 |

| Total | 4,213 | 100 |

Table 5.

Covid-19 deaths in Northern Ireland according to age group.

| Age groups (Years) | Number of deaths | Percentage of total deaths |

|---|---|---|

| <15 | 0 | 0.00 |

| 15–44 | 7 | 0.82 |

| 45–64 | 53 | 6.21 |

| 65–74 | 110 | 12.88 |

| 75–84 | 285 | 33.37 |

| 85+ | 399 | 46.72 |

| Total | 854 | 100 |

Table 6.

Covid-19 deaths in Wales according to age group.

| Age groups (Years) | Number of deaths | Percentage of total deaths |

|---|---|---|

| <15 | 0 | 0 |

| 15–44 | 24 | 0.96 |

| 45–64 | 222 | 8.85 |

| 65–74 | 396 | 15.79 |

| 75–84 | 796 | 31.74 |

| 85+ | 1,070 | 42.66 |

| Total | 2,508 | 100 |

In England and Wales, males had a significantly higher mortality involving COVID-19 (age standardised estimates in England = 99 deaths per 100,000 population; Wales = 59 deaths per 100,000 population) than females (47 and 35 deaths per 100,000 population in England and Wales respectively) [37]. In England alone, as of 13th May 2020, males (74 per 100,000) had twice the risk of COVID-19 deaths compared to that of females (38 per 100,000) [40]. As of 13th August 2020, in England the proportion of deaths involving COVID-19 was 39.2% in females and 60.8% in males [37]. In Northern Ireland, as of 31st July 2020, similar proportion of deaths that involved COVID-19 was observed in males (49.9%) and females (50.1%) [39]. As of 13th August 2020, Scotland also observed similar proportion of deaths in males (49.6%) and females (50.4%), however analysis of data for April 2020 showed that age standardised death rates in males (716 per 100,000) were approaching double that of females (479 per 100,000) [38]. Furthermore, analysis of 16,649 COVID-19 cases (between February and April 2020) in 166 UK hospitals (adjusted for age, comorbidities and obesity), showed that females had 20% lower risk of COVID-19 death compared with males [41].

Differences in mortality for ethnic groups have also been reported for England (Table 7 ). As of 13th August 2020, around 73% of deaths involving COVID-19 were recorded in white-British (including Irish), and 7% of deaths from people of Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi or any other Asian descent. People of Caribbean or African descent accounted for ~4% of deaths. Furthermore, as of 9th May 2020, analysis of deaths in COVID-19 cases (adjusted for sex, age, deprivation and region) in England suggested that people of Bangladeshi ethnicity had around twice the risk of death compared with people of White British ethnicity [41]. Other ethnic groups (Chinese, Indian, Pakistani, other Asian, Caribbean and Other Black ethnicity) also had higher risk of death (10% to 50%) compared with White British [41]. In Scotland, adjusted analysis (adjusted for age, sex, deprivation and urban-rural classification) of data between 12th March to 14th June 2020 suggested that people of South-Asian descent are twice as likely to have deaths involving COVID-19 [38].

Table 7.

Covid-19 deaths in England according to ethnicity.

| Ethnic groups | Number of deaths | Percentage of total deaths |

|---|---|---|

| British White | 21,500 | 73.2 |

| Irish | 256 | 0.9 |

| Any other White background | 909 | 3.1 |

| White and Black Caribbean | 47 | 0.2 |

| White and Black African | 16 | 0.1 |

| White and Asian | 35 | 0.1 |

| Any other Mixed background | 69 | 0.2 |

| Indian | 792 | 2.7 |

| Pakistani | 523 | 1.8 |

| Bangladeshi | 175 | 0.6 |

| Any other Asian background | 429 | 1.5 |

| Caribbean | 647 | 2.2 |

| African | 435 | 1.5 |

| Any other Black background | 225 | 0.8 |

| Chinese | 83 | 0.3 |

| Any other ethnic group | 641 | 2.2 |

| Not stated | 2,388 | 8.1 |

| No match | 274 | 0.9 |

Data released for England and Wales showed that 3,563 (91%) of the 3912 deaths that occurred in March 2020 were people with at least one pre-existing condition, whereas only 349 (9%) of people who died in the same time period had none [40]. Ischaemic heart disease, which was present in 14% of all COVID-19 deaths, was the most common pre-existing condition. Pneumonia, dementia and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease were amongst the top five most common pre-existing conditions [40]. An analysis carried out by Public Health England [41] showed that between 21st March to 1st May 2020 in England alone, 44.5% COVID-19 deaths included cardiovascular disease as a pre-existing condition on death certificates, followed by dementia (25.7%), diabetes (21.1%), hypertensive diseases (19.6%), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (11.5%) and chronic kidney disease (10.8%). The proportion of deaths in people with diabetes was largest in males aged 60–69, and was higher in all Black, Asian and Ethnic Minority groups compared with the White-British group [41].

COVID-19 mortality rates also varied according to the index of deprivation. As of 9th May 2020, in England, both males and females in the most deprived areas had twice the COVID-19 mortality rates compared with the least deprived areas [41]. Furthermore, adjusted analysis (adjusted for age, sex, ethnicity and region) showed that chances of survival in COVID-19 cases from the most deprived areas were lower, with people of working age (20–64 years) half as likely to survive compared with working age people from the least deprived areas [41]. On the 20th April 2020, reports emerged on the number of health and social care workers, including other key workers reported to have died from COVID-19. Based on ONS statistics [42] released on the 11th May, there were 237 COVID-19 related deaths of health and social care workers between the 9th March and 20th April.

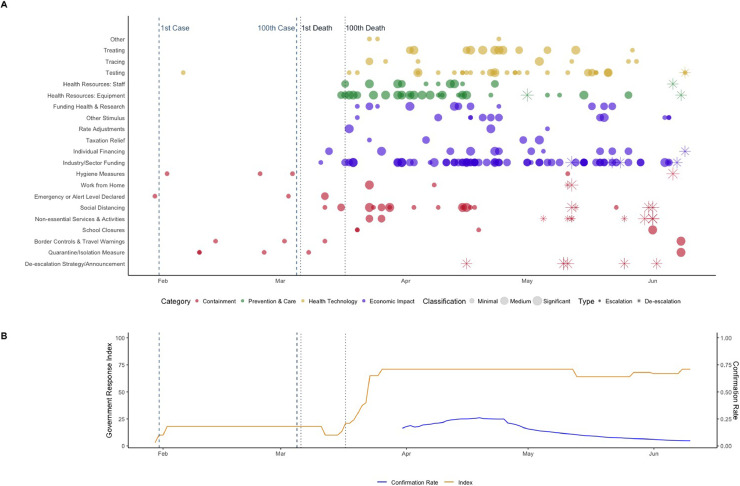

Policy and technology road map

Since the initial notification of the SARS-CoV-2 virus to the World Health Organisation at the end of December 2019, a minimum of 143 actions and interventions have occurred in the UK to contain and mitigate the spread of the virus. To examine these interventions, we followed the categorisation process proposed by Moy et al. [32] and the Oxford stringency index developed by Hale et al. [43] (presented in Fig. 5 ). The policy categorisation proposes several classifications for COVID-19 interventions, that escalate in severity and then de-escalate as governments wind-down response measures. These classifications relate to policies that contain and mitigate COVID-19 - preventing the severity of the impact on health and increasing care. The categorisation also classifies economic and health technology interventions. Data from the 10th of June are not shown as the devolved administrations in the UK adopted a decentralised approach to adjusting policies aimed at preventing the spread of SARS-CoV-2. For example, England allowed pubs and restaurants to open from July 4th, whilst this did not occur until July 15th in Scotland. Indoor restaurants and pubs could open from 3rd August in Wales, and Northern Ireland indoor restaurants and pubs serving food could open from July 3rd.

Fig. 5.

Sample Policy and Technology Roadmap in the UK

Panel A [top] is the Categorisation process, [32]; Panel B [bottom] is the Oxford Stringency Index. [44]

Note: Tracing only refers to NHS Testing and Tracing Service, whereby anyone in the UK with symptoms can request an antigen test via a dedicated website.

During the initial stages of the pandemic, the government focused on the prevention and mitigation of the spread of the virus, implementing a series of TV, radio and social media campaigns and recommendations for behaviour change in the general public. As seen in Fig. 5A, most of the measures related to containment policies until the 100th death from COVID-19. Thereafter the number of measures increased, and the stringency of containment measures escalated (see Fig. 5B), with the introduction of social distancing measures and fines, increased measures were directed towards economic stimulus and health care resourcing. The most significant restriction was the closure of non-essential services on the 16th March, followed by a lockdown on the 23rd of March. This lockdown required all individuals to stay at home and work from home where possible, with only an hour of exercise, trips for food shopping and medication allowed per day, and a social distancing measure of 2 m. Nevertheless, cases continued to rise in the UK before stabilising as the number of daily cases steadily dropped, as demonstrated by the confirmation rate (positive cases/number of tests) reducing in Fig. 5B. The daily peak in modelled symptomatic and lab-confirmed cases occurred after the lockdown on the 1st April and 1st May respectively (see Section 3.1 and Fig. 1A). It is after the peak of cases (and the number of confirmed cases continued to drop) that the severity of policies was reduced or de-escalated.

Health care system response data

In 2019 the curative hospital bed capacity in the UK was 127,225 beds available in acute hospitals, maternity centres and units specialising in the care of patients with mental health conditions and learning disabilities [45]. This is the lowest availability of beds since records began in 1987/88. Over the same period (1987/88 to 2019), the number of patients being treated by the NHS has increased significantly, highlighting a system facing significant resource pressures. Indeed, over this period, there has been a 34% reduction in the availability of beds for general and acute care, with the largest reductions in bed numbers occurring for severe mental illness and learning disability beds, including a reduction in beds for the long-term care of the elderly [46]. Based on data from 2019, across hospital, community and primary care settings there were ~150,000 NHS doctors, and approximately 320,000 NHS nurses and midwives. These numbers constitute approximately one third of the overall NHS workforce, with large numbers also working as health care scientists, allied health professionals, and as employees of NHS trusts providing ambulance, mental health and community and hospital services [47].

On the 13th March, in response to COVID-19 pandemic, the government announced the building of temporary critical care NHS Nightingale hospitals across England. Seven were rapidly constructed across England, which increased critical bed capacity by more than 3,600 [48].

In England, mean daily emergency department (ED) attendances reduced year-on-year for the months of March (69,921/day to 49,390/day; 39.4%), April (70,406/day to 30,553/day; 56.6%), May (70,065/day to 40,704/day; 41.9%) and June (70,266/day to 47,043/day; Table 8 ) [49]. Whilst the total number of hospital admissions decreased year-on-year, the proportion of emergency attendances increased year-on-year across the months of March (25.6% to 27.9%), April (25.3% to 35.6%), May (25.2% to 31.6%) and June (25.1% to 31.0%). Together, the large reductions in ED attendance in England suggest that patients were avoiding EDs in response to COVID-19 and remained so in the short term even when infection rates reduced following the lockdown on the 23rd March.

Table 8.

Unscheduled emergency and urgent care usage in England for financial year 2019/20.

| Month (number of days) | Emergency Department |

Ambulance Services |

NHS 111 |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attendances* (mean / day) | Emergency admissions (% of attendances) | Calls received (mean / day) | Calls answered (% of calls received) | Number of incidents (mean / day) | Transport to ED (% of incidents) | Transport not to ED (% of incidents) | Calls received (mean / day) | Calls answered (% of calls received) | Ambulances dispatched (% of calls answered) | Recommended to attend ED (% of calls answered) | Recommended to attend primary care (% of calls answered) | |

| March 2019 (31) | 2167,551 (69,921) | 555,457 (25.6) | 991,116 (31,971) | 738,407 (74.5) | 729,977 (23,548) | 429,213 (58.8) | 40,021 (5.5) | 1,447,126 (46,681) | 1,319,251 (91.2) | 154,599 (11.7) | 103,455 (7.8) | 683,747 (51.8) |

| April 2019 (30) | 2112,184 (70,406) | 535,226 (25.3) | 978,082 (32,603) | 720,039 (73.6) | 711,247 (23,708) | 417,673 (58.7) | 37,953 (5.3) | 1,452,444 (48,415) | 1,323,527 (91.1) | 151,523 (11.4) | 101,331 (7.7) | 683,747 (52.0) |

| May 2019 (31) | 2172,022 (70,065) | 547,382 (25.2) | 999,613 (32,246) | 734,735 (73.5) | 726,120 (23,423) | 425,001 (58.5) | 39,190 (5.4) | 1,452,371 (46,851) | 1,310,281 (90.2) | 150,681 (11.5) | 105,079 (8.0) | 687,746 (50.7) |

| June 2019 (30) | 2107,985 (70,266) | 528,801 (25.1) | 999,675 (33,323) | 741,519 (74.2) | 703,277 (23,443) | 410,196 (58.3) | 36,893 (5.2) | 1,369,638 (45,655) | 1,223,326 (89.3) | 146,078 (11.9) | 101,540 (8.3) | 664,085 (49.2) |

| July 2019 (31) | 2265,050 (73,066) | 554,069 (24.5) | 1,063,085 (34,293) | 799,052 (75.2) | 736,659 (23,763) | 423,931 (57.5) | 39,308 (5.3) | 1,425,320 (45,978) | 1,240,552 (87.0) | 146,506 (11.8) | 105,710 (8.5) | 601,620 (48.4) |

| August 2019 (31) | 2125,444 (68,563) | 529,231 (24.9) | 1,005,111 (32,423) | 749,582 (74.6) | 718,456 (23,176) | 413,168 (57.5) | 40,197 (5.6) | 1,412,600 (45,568) | 1,250,808 (88.5) | 143,804 (11.5) | 104,698 (8.4) | 600,914 (50.2) |

| September 2019 (30) | 2123,558 (70,785) | 529,903 (25.0) | 987,727 (32,924) | 739,073 (74.8) | 699,517 (23,317) | 404,338 (57.8) | 39,502 (5.6) | 1,315,344 (43,845) | 1,153,993 (87.7) | 140,784 (12.2) | 99,933 (8.7) | 628,445 (49.6) |

| October 2019 (31) | 2170,510 (70,016) | 563,079 (25.9) | 1,053,232 (33,975) | 796,646 (75.6) | 740,459 (23,886) | 430,687 (58.2) | 42,296 (5.7) | 1,404,399 (45,303) | 1,231,442 (87.7) | 155,106 (12.6) | 102,000 (8.3) | 572,004 (49.2) |

| November 2019 (30) | 2143,336 (71,455) | 559,556 (26.1) | 1,074,899 (35,830) | 803,518 (74.8) | 743,824 (24,794) | 430,684 (57.9) | 41,239 (5.5) | 1,588,137 (52,938) | 1,338,361 (84.3) | 163,284 (12.2) | 105,819 (7.9) | 605,962 (48.3) |

| December 2019 (31) | 2181,024 (70,365) | 560,801 (25.7) | 1,153,662 (37,215) | 853,532 (74.0) | 790,294 (25,493) | 448,886 (56.8) | 42,216 (5.3) | 1,844,804 (59,510) | 1,577,276 (85.5) | 187,089 (11.9) | 121,182 (7.7) | 646,646 (51.7) |

| January 2020 (31) | 2114,623 (68,214) | 559,058 (26.4) | 1,000,827 (32,285) | 724,594 (72.4) | 750,238 (24,201) | 432,951 (57.7) | 41,727 (5.6) | 1,503,318 (48,494) | 1,329,760 (88.5) | 159,866 (12.0) | 114,211 (8.6) | 815,917 (50.8) |

| February 2020 (29) | 1969,691 (67,920) | 510,811 (25.9) | 963,143 (33,212) | 700,325 (72.7) | 695,791 (23,993) | 397,097 (57.1) | 38,114 (5.5) | 1625,240 (56,043) | 1362,402 (86.9) | 150,008 (11.0) | 108,399 (8.0) | 675,202 (49.8) |

| March 2020 (31) | 1531,100 (49,390) | 427,921 (27.9) | 1,127,570 (36,373) | 866,575 (76.9) | 764,726 (24,669) | 368,557 (48.2) | 33,968 (4.4) | 2,962,751 (95,573) | 1,388,916 (46.9) | 133,860 (9.6) | 74,135 (5.3) | 678,319 (43.2) |

| April 2020 (30) | 916,581 (30,553) | 326,581 (35.6) | 879,477 (29,316) | 626,424 (71.2) | 683,732 (22,791) | 298,094 (43.6) | 35,449 (5.2) | 1,655,146 (55,172) | 1,254,667 (75.8) | 137,419 (11.0) | 92,939 (7.4) | 599,443 (44.4) |

| May 2020 (31) | 1261,836 (40,704) | 398,407 (31.6) | 835,402 (26,948) | 573,375 (68.6) | 682,244 (22,008) | 345,046 (50.6) | 37,592 (5.5) | 1,620,102 (52,261) | 1,410,028 (87.0) | 149,373 (10.6) | 130,751 (9.3) | 559,745 (46.6) |

| June 2020 (30) | 1411,312 (47,043) | 437,535 (31.0) | 843,628 (28,121) | 583,011 (69.1) | 677,285 (22,576) | 359,656 (53.1) | 39,237 (5.8) | 1,449,576 (48,319) | 1,298,076 (89.5) | 145,981 (11.2) | 134,554 (10.4) | 576,615 (44.4) |

* Includes unplanned attendances at all accident & emergency unit types, including urgent care centres. For full definitions see [49].

The mean number of emergency (999) calls to ambulance services in England increased year-on-year by 4,402/day (13.8%) in March, but then decreased by 3,287 (10.1%) in April, 5,298 (16.4%) in May and 5,202 (15.6%) in June. Urgent care calls to NHS111 in England increased by 48,892 calls/day (104.7%) year-on-year in March. Unlike emergency calls, NHS111 experienced year-on-year increased demand of 6,757 calls/day (14.0%) in April; 5,410 calls/day (11.5%) in May; and 2,665 (5.8%) in June.

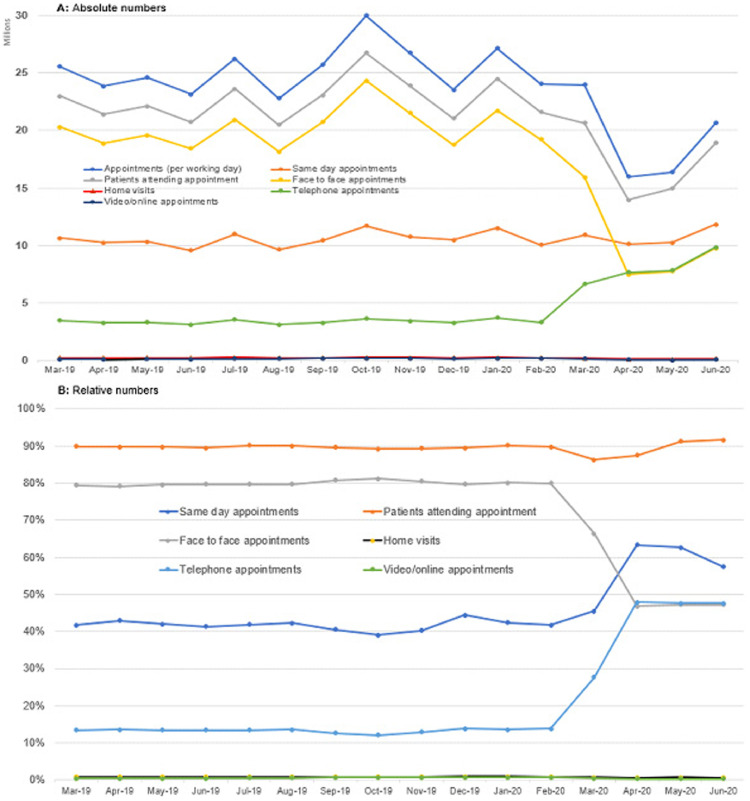

Primary care utilisation also changed in England during the COVID-19 pandemic, with a year-on-year reduction in the overall number of appointments per working day in April (393,663; 33.0%), May (310,305; 26.5%) and June (218,475; 18.9%) (Table 9 , Fig. 6 ) [50]. This reduction was associated with improved access to appointments, as measured by the proportion of same day appointments, with year-on-year increases in March (41.7% to 45.5%), April (43.0% to 63.3%), May (42.0% to 62.6%) and June (41.4% to 57.4%). The mode of appointment delivery also changed, with a year-on-year reduction in face-to-face appointments in March (79.4% to 66.4%), April (79.2% to 46.8%), May (79.5% to 47.2%) and June (79.7% to 47.3%). Instead there were large year-on-year increases in the number of telephone appointments in March (13.5% to 27.7%), April (13.6% to 47.9%), May (13.5% to 47.7%) and June (13.4% to 47.7%). Notably there was a change in trend of using online or video appointments, with year-on-year decreases in April (0.4% to 0.3%), May (0.5% to 0.3%) and June (0.5% to 0.3%).

Table 9.

Primary care usage in England. Data retrieved from [50].

| Month (working days) | Appointments (per working day) | Same day appointments (%) | Patients attending appointment (%) | Face to face appointments (%) | Home visits (%) | Telephone appointments (%) | Video/online appointments (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| March 2019 (21) | 25,551,347 (1216,731) | 10,644,172 (41.7) | 22,976,176 (89.9) | 20,280,140 (79.4) | 233,888 (0.9) | 3,450,232 (13.5) | 117,719 (0.5) |

| April 2019 (20) | 23,842,026 (1192,101) | 10,246,379 (43.0) | 21,388,211 (89.7) | 18,879,469 (79.2) | 225,474 (0.9) | 3,252,514 (13.6) | 106,188 (0.4) |

| May 2019 (21) | 24,625,282 (1172,632) | 10,334,358 (42.0) | 22,116,962 (89.8) | 19,586,147 (79.5) | 227,541 (0.9) | 3,328,022 (13.5) | 119,845 (0.5) |

| June 2019 (20) | 23,133,483 (1156,674) | 9570,084 (41.4) | 20,713,725 (89.5) | 18,441,483 (79.7) | 211,526 (0.9) | 3,106,915 (13.4) | 120,668 (0.5) |

| July 2019 (23) | 26,235,492 (1140,674) | 10,983,897 (41.9) | 23,637,793 (90.1) | 20,915,751 (79.7) | 244,072 (0.9) | 3,542,546 (13.5) | 160,441 (0.6) |

| August 2019 (21) | 22,783,314 (1084,920) | 9,632,555 (42.3) | 20,512,733 (90.0) | 18,152,198 (79.7) | 213,481 (0.9) | 3,103,708 (13.6) | 145,700 (0.6) |

| September 2019 (21) | 25,721,636 (1224,840) | 10,455,788 (40.6) | 23,048,053 (89.6) | 20,747,434 (80.7) | 228,780 (0.9) | 3,277,807 (12.7) | 172,593 (0.7) |

| October 2019 (23) | 29,980,935 (1303,519) | 11,710,931 (39.1) | 26,736,947 (89.2) | 24,344,901 (81.2) | 271,405 (0.9) | 3,624,208 (12.1) | 195,524 (0.7) |

| November 2019 (21) | 26,737,065 (1273,194) | 10,765,794 (40.3) | 23,879,947 (89.3) | 21,531,910 (80.5) | 251,106 (0.9) | 3,444,334 (12.9) | 176,057 (0.7) |

| December 2019 (20) | 23,542,556 (1177,128) | 10,463,465 (44.4) | 21,066,467 (89.5) | 18,770,999 (79.7) | 237,332 (1.0) | 3,252,172 (13.8) | 157,579 (0.7) |

| January 2020 (22) | 27,127,359 (1233,062) | 11,511,107 (42.4) | 24,477,156 (90.2) | 21,733,392 (80.1) | 266,942 (1.0) | 3,701,774 (13.6) | 194,206 (0.7) |

| February 2020 (20) | 24,039,140 (1201,957) | 10,031,679 (41.7) | 21,584,790 (89.8) | 19,230,573 (80.0) | 227,935 (0.9) | 3,322,241 (13.8) | 172,638 (0.7) |

| March 2020 (22) | 23,988,047 (1090,366) | 10,917,167 (45.5) | 20,666,474 (86.2) | 15,921,842 (66.4) | 172,773 (0.7) | 6,637,654 (27.7) | 127,228 (0.5) |

| April 2020 (20) | 15,968,758 (798,438) | 10,114,996 (63.3) | 13,949,365 (87.4) | 7,480,876 (46.8) | 100,655 (0.6) | 7,651,779 (47.9) | 44,146 (0.3) |

| May 2020 (19) | 16,384,210 (862,327) | 10,255,098 (62.6) | 14,934,567 (91.2) | 7,729,847 (47.2) | 112,011 (0.7) | 7,813,720 (47.7) | 41,560 (0.3) |

| June 2020 (22) | 20,640,372 (938,199) | 11,840,329 (57.4) | 18,900,207 (91.6) | 9,763,062 (47.3) | 133,789 (0.6) | 9,847,469 (47.7) | 58,990 (0.3) |

* Not all primary care practices are included due to reporting limitations, although mean monthly patient coverage is 97.1% (range 96.2% to 97.4%) and mean monthly practice coverage is 96.1% (range 95.1% to 96.4%) for covered time period. Later statistical releases may have more accurate data.

Fig. 6.

Time series graphs of primary care usage (absolute and relative numbers) in England.

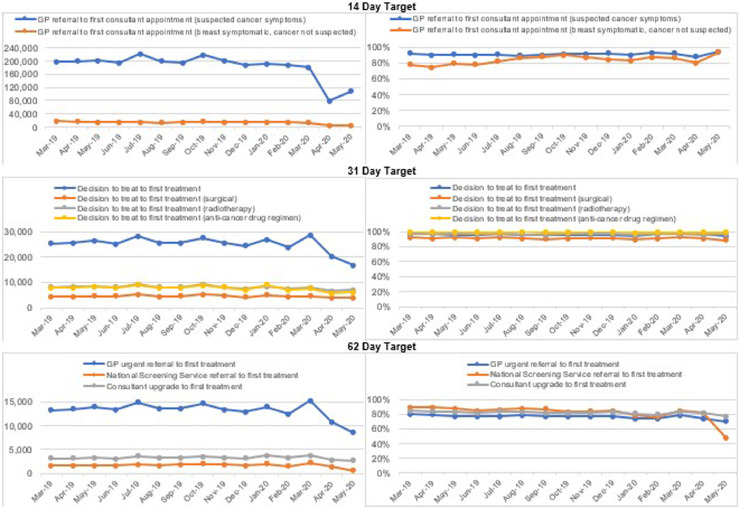

Cancer referrals, which are measured based on 14-day, 31-day and 62-day targets (Table 10 , Fig. 7 ) suggest that the COVID-19 pandemic has affected access to cancer referrals and treatment, particularly during the months of April and May for which latest data are available. Referrals across all targets reduced by between 10.1% (62-day consultant upgrade to first treatment; April) and 77.6% (GP referral to first consultant appointment for breast symptoms where cancer is not suspected; April) [51]. For the key 14-day target of GP referral to first consultant appointment for symptomatic cases, there was a relatively small year-on-year decrease in March of 16,545 (8.3%). However, in April the number of referrals decreased 119,644 (60.1%), and in May decreased by 94,261 (46.9%).

Table 10.

Cancer care targets in England based on provider data. Data retrieved from [51].

| Month | 14-day target |

31-day target |

62-day target |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GP referral to first consultant appointment (suspected cancer symptoms) | GP referral to first consultant appointment (breast symptomatic, cancer not suspected) | Decision to treat to first treatment | Decision to treat to first treatment (surgical) | Decision to treat to first treatment (radiotherapy) | Decision to treat to first treatment (anti-cancer drug regimen) | GP urgent referral to first treatment | National Screening Service referral to first treatment | Consultant upgrade to first treatment | |

| Total (% within target) | Total (% within target) | Total (% within target) | Total (% within target) | Total (% within target) | Total (% within target) | Total (% within target) | Total (% within target) | Total (% within target) | |

| March 2019 | 198,418 (91.8) | 17,137 (78.1) | 25,210 (96.5) | 4,473 (92.3) | 8,146 (97.1) | 7,923 (99.3) | 13,276 (79.7) | 1,607 (89.5) | 3,192 (85.1) |

| April 2019 | 199,217 (89.8) | 16,753 (74.9) | 25,608 (96.4) | 4,383 (91.2) | 8,530 (96.6) | 7,776 (98.9) | 13,519 (79.4) | 1,798 (89.7) | 3,172 (84.0) |

| May 2019 | 200,796 (90.8) | 15,949 (78.9) | 26,326 (96.0) | 4,605 (92.0) | 8,305 (96.3) | 8,359 (99.3) | 13,998 (77.6) | 1,803 (87.5) | 3,253 (83.2) |

| June 2019 | 194,047 (90.1) | 14,885 (78.0) | 25,091 (96.0) | 4,640 (91.2) | 8,024 (96.6) | 7,873 (99.2) | 13,324 (76.8) | 1,713 (85.1) | 3,005 (81.3) |

| July 2019 | 221,805 (90.9) | 15,824 (82.5) | 28,246 (96.5) | 5,106 (92.3) | 9,407 (97.2) | 8,865 (99.2) | 14,930 (77.8) | 1,890 (85.8) | 3,641 (83.7) |

| August 2019 | 200,317 (89.4) | 13,220 (86.0) | 25,767 (96.1) | 4,343 (91.4) | 8,052 (96.2) | 7,761 (99.4) | 13,651 (78.7) | 1,775 (87.9) | 3,297 (83.4) |

| September 2019 | 195,196 (90.1) | 13,475 (88.1) | 25,611 (95.5) | 4,640 (90.3) | 8,186 (95.1) | 7,906 (99.1) | 13,581 (77.0) | 1,864 (87.0) | 3,283 (81.3) |

| October 2019 | 218,790 (91.4) | 16,121 (89.9) | 27,437 (96.2) | 5,204 (91.1) | 9,182 (96.6) | 8,727 (99.2) | 14,591 (77.1) | 1,994 (83.0) | 3,493 (82.1) |

| November 2019 | 201,395 (91.3) | 15,370 (87.5) | 25,551 (95.9) | 4,762 (91.7) | 8,057 (96.9) | 8,086 (99.4) | 13,432 (77.4) | 1,866 (83.8) | 3,313 (81.8) |

| December 2019 | 187,789 (91.8) | 14,773 (84.3) | 24,321 (96.0) | 4,121 (91.6) | 7,381 (96.6) | 7,190 (99.3) | 12,865 (78.0) | 1,785 (85.2) | 3,151 (82.9) |

| January 2020 | 191,704 (90.1) | 14,335 (83.6) | 26,971 (94.5) | 4,971 (89.2) | 8,470 (94.8) | 8,908 (98.0) | 13,954 (73.6) | 2,034 (78.9) | 3,778 (80.8) |

| February 2020 | 188,740 (92.7) | 13,602 (87.3) | 23,693 (96.3) | 4,328 (91.2) | 7,520 (96.8) | 7,113 (99.0) | 12,433 (73.8) | 1,583 (76.1) | 3,281 (79.6) |

| March 2020 | 181,873 (92.0) | 12,411 (86.1) | 28,557 (96.8) | 4,596 (92.6) | 7,812 (96.6) | 7,650 (99.2) | 15,363 (78.9) | 2,292 (85.1) | 3,726 (83.0) |

| April 2020 | 79,573 (88.0) | 3,759 (80.8) | 20,137 (96.3) | 3,814 (90.9) | 6,532 (95.3) | 5,568 (99.0) | 10,792 (74.3) | 1,361 (81.2) | 2,852 (81.2) |

| May 2020 | 106,535 (94.2) | 5,371 (93.7) | 16,678 (93.9) | 3,891 (88.5) | 7,040 (96.3) | 6,286 (99.0) | 8564 (69.9) | 551 (47.9) | 2,658 (78.1) |

Fig. 7.

Time series graphs of cancer care targets in England based on provider data.

Consultant-led referral to treatment waiting times were also impacted by COVID-19 (Table 11 ) [52]. There was no major year-on-year change in the number of patients waiting for treatment to begin up to March 2020, although there was a decrease of 8.3% in April 2020 and 12.6% in May 2020. Overall waiting times, however, were impacted to a greater extent, with a year-on-year rise in median waiting times in March of 2.0 weeks (30%), 5.0 weeks (68.8%) in April and 7.6 weeks (98.7%) in May. The number of new outpatients decreased year-on-year in March by 117,029 (10.7%), in April by 519,915 (40.7%) and in May by 597,268 (54.2%). Outpatient waiting times increased marginally year-on-year in March by 0.2 weeks (2.8%) and by 1.8 weeks (27.7%) and 2.4 weeks (38.1%) in April and May respectively. The number of new inpatients waiting for treatment reduced year-on-year by 97,602 (32.0%) in March, by 239,088 (85.3%) in April and 241,331 (81.6%) in May. However unlike for outpatients, there was a corresponding reduction in waiting times of 1.9 weeks (17.8%) in March, 6.2 weeks (62%) in April and 6.2 weeks (60.2%) in May.

Table 11.

Referral to treatment waiting times in England. Data retrieved from [52].

| Month | Total patients waiting for treatment (% within 18 weeks) | Median waiting time, weeks | New inpatients waiting for treatment | Inpatient median waiting time, weeks | New outpatients waiting for treatment | Outpatient Median waiting time, weeks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| March 2019 | 4,233,414 (86.7) | 6.9 | 305,356 | 10.3 | 1,095,701 | 5.6 |

| April 2019 | 4,297,571 (86.5) | 7.2 | 280,209 | 10.0 | 1,046,015 | 5.8 |

| May 2019 | 4,385,693 (86.9) | 7.7 | 295,881 | 10.3 | 1,102,958 | 6.3 |

| June 2019 | 4,395,246 (86.3) | 7.5 | 289,203 | 10.6 | 1,064,501 | 6.2 |

| July 2019 | 4,372,568 (85.8) | 7.3 | 314,280 | 10.2 | 1,179,146 | 6.1 |

| August 2019 | 4,407,964 (85.0) | 8.0 | 275,267 | 10.0 | 1,006,145 | 6.1 |

| September 2019 | 4,416,883 (84.8) | 8.0 | 288,230 | 10.7 | 1,080,810 | 6.8 |

| October 2019 | 4,446,299 (84.7) | 7.6 | 317,992 | 10.8 | 1,201,901 | 6.5 |

| November 2019 | 4,415,207 (84.4) | 7.7 | 303,193 | 10.4 | 1,125,754 | 6.4 |

| December 2019 | 4,416,584 (83.7) | 8.3 | 253,318 | 9.6 | 971,532 | 6.0 |

| January 2020 | 4,417,420 (83.5) | 8.4 | 304,888 | 11.1 | 1,165,019 | 7.2 |

| February 2020 | 4,425,306 (83.2) | 7.5 | 285,819 | 11.2 | 1,059,832 | 6.4 |

| March 2020 | 4,235,970 (79.7) | 8.9 | 207,754 | 8.4 | 978,672 | 5.8 |

| April 2020 | 3,942,748 (71.3) | 12.2 | 41,121 | 3.8 | 526,100 | 7.4 |

| May 2020 | 3,834,571 (62.2) | 15.3 | 54,550 | 4.1 | 505,690 | 8.7 |

Business and economy

The full magnitude of the impact of COVID-19 on the UK economy will not be clear for some time. In the short-term, the government has announced several schemes aimed at supporting businesses and their employees during the pandemic [53], [54], [55], [56], [57]. These are summarised in Table 12 , although official figures are unavailable for a number of these initiatives.

Table 12.

| Scheme | Summary | Country | Online Publication Date | Latest statistics available | Numbers accessing scheme | Costs of scheme (£) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme | Allows employers who are unable to maintain their workforce to ‘furlough’ employees; i.e. retain them while they are unable to work and claim 80% of employee's wages (up to a maximum of £2500 per month) as well as employer National Insurance and pension contributions. This scheme is set to close on October 31st 2020. This was later updated to include a further initiative - the Job Retention Bonus provides a one-off payment of £1000 to employers for every employee continuously employed until the end of January 2021. | UK-wide | 20th April 2020 | 9th August 2020 | 9.6 million employees from 1.2 million employers | 34.7 billion worth of claims made |

| Statutory Sick Pay Rebate Scheme | Will replay employers who paid employees for periods of sickness for up to two weeks starting on 13th March 2020 | UK-wide | 3rd April 2020 | No statistics identified | ||

| Deferral of VAT payments | Some tax payments have been postponed, with businesses being given the option to defer VAT (Value Added Tax) payments due between 20th March and 30th June 2020. | UK-wide | 26th March 2020 | 7th June 2020 | 140,000 payments due by 7th April, 243,000 due by 7th May and 113,000 due by 7th June deferred. | 27.5 billion (cumulative VAT deferred) |

| Deferral of Self-Assessment tax payments | For the self-employed, a July 2020 payment deadline was extended until January 2021 | UK-wide | Not stated | No statistics identified | ||

| Business rates relief for retail, hospitality or leisure businesses | Businesses from the retail, hospitality and leisure sectors were granted a ‘business rate holiday’ for the 2020–2021 tax year | England | 18th March 2020 | No statistics available | ||

| Business rates relief for nurseries | Similar to the above; ‘business rate holidays’ given to some nurseries | England | 22nd March 2020 | No statistics available | ||

| Small business grant fund | Provision of grants of up to £10,000 to small businesses from their local council | England | 1st April 2020 | 9th August 2020 | 886,180 business properties | 10.87 billion |

| Retail, Hospitality and Leisure Grant | A grant of up to £25,000 to businesses working in the retail, hospitality and leisure industries from their local council | England | 1st April 2020 | Included in above figures | ||

| Local Authority Discretionary Grants Fund | Grants of £25,000, £10,000 or under allocated by local councils for small and micro businesses with fixed property costs who are not eligible for the above two schemes. | England | 29th May 2020 | No statistics identified | ||

| Self-employment Income Support Scheme | Self-employed workers can claim a taxable grant of 80% of their trading profits (up to £2500 per month), initially available for 3 months but subsequently extended to cover a further 3 months at 70% of trading profits (up to £6570) | UK wide | 26th March 2020 | 19th July | 2.7 m claims made | 7.8 billion |

| Business Interruption Loan Scheme | Small and medium sized businesses can access government backed (guaranteed up to 80%) loans of up to £5 million and the interest and lender-fees for the first 12 months will be paid by the government in the form of a Business Interruption Payment | UK wide | 23rd March 2020 | 9th August 2020 | 59, 520 facilities | 13.41 billion |

| Coronavirus Future Fund | Companies which rely on equity investment, may be eligible for the Coronavirus Future Fund under which the government will provide loans of £125,000 to £5 million if these will be matched by private investors | UK wide | 20th April 2020 | 9th August 2020 | 565 convertible loans approved | 562.3 million |

| Bounce Back Loans | Aimed at small to medium-sized businesses; allowing them to borrow between £2000 and £50,000 (up to 25% of their turnover). The loan is guaranteed by the government and has no fees or interest for the first 12 months (2.5% thereafter) | UK wide | 27th April 2020 | 9th August 2020 | 1157,296 facilities | 34.96 billion |

| Coronavirus Large Business Interruption Loan Scheme | Support for larger businesses in the form of the government guaranteeing lenders 80% of loan values up to £200 million | UK wide | 21st April 2020 | 9th August 2020 | 497 facilities | 3.40 billion |

| COVID-19 Corporate Financing Facility (CCFF) | This will see the Bank of England buying short-term debt from large companies | UK wide | 20th March 2020 | 12th August 2020 | 203 businesses approved for CCFF issuance | 17,550 million (less repayments) |

| Eat Out to Help Out Scheme | This scheme allows eating establishments to discount food and non-alcoholic drinks by 50% from Monday to Friday between 3 and 31st August 2020 (up to £10 per diner) and claim the money back from the government. | UK wide | 9th July | 9th August | 10.5 million | 53.7million |

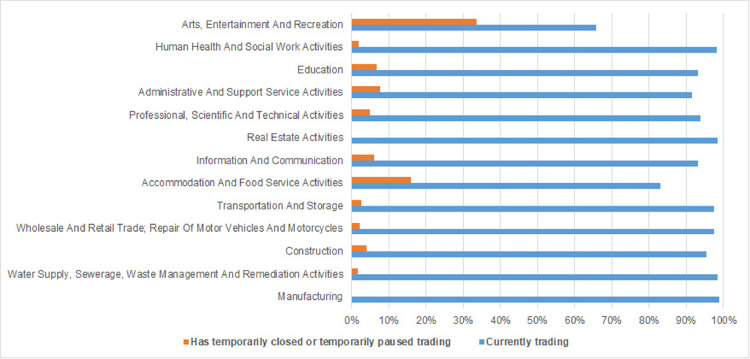

The Office for National Statistics (ONS) reports on the Business Impact of Coronavirus Survey (BICS) - a 2-weekly survey of UK businesses [58]. Between 13th and 26th July, out of 5,733 businesses completing the survey, 5.7% reported temporary closure or a pause in trading. The remaining businesses continuing to trade reported that their financial performance was outside their normal range, with 53.6% of these reporting a lower turnover. Sectors have not been affected uniformly with 15.9% of respondents from the Accommodation and Food Services sector and 33.7% of those from the Arts Entertainment and Recreation sector reporting a temporary pause in trading. In contrast, less than 2% of Human Health and Social Work and Professional Scientific and Technical sectors reported a pause in trading (Fig. 8 ).

Fig. 8.

Trading status of business by sector (N = 5,733)

Business Impact of Coronavirus Survey (data from the period 13th and 26th July).

The number of people claiming Universal Credit, a payment available to individuals in the UK who are unemployed or have a low-income, was 5.6 million on July 9th 2020, while this represents an increase of 2% since June 2020, between March and April 2020 the number of people on Universal Credit increased by 40% [59]. Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is a key indicator of the economic performance of a country. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) outlines a range of factors likely to impact GDP: a reduction in labour supply; quarantines; lockdowns; social distancing reducing mobility; and the closure of workplaces. These factors all reduce productivity and disrupt supply chains, which when coupled with job losses and reduced income (along with fear and uncertainty) lead to reduced public spending [60]. The ONS reported a 2.2% fall in GDP in Q1 2020 and a 20.4% fall in Q2 [61]. Rolling 3-month data reported by the ONS indicated that, ahead of the 20.4% drop in GDP in the 3 months to June 2020, there was a fall of 18.7% in the 3 months prior to May 2020, while monthly data showed a 2.4% increase in GDP in May 2020 and an 8.7% rise in June 2020 [62].

The IMF has forecasted a fall in the UK economy by 6.5% in 2020, but emphasised uncertainty in these assumptions due to how long the pandemic will last and the magnitude and duration of the effects on economic activity, and financial markets [60]. Imports and exports to the UK both decreased in the three months to May 2020 [63]. Total trade (i.e. goods and services) exports, excluding precious metals, fell by £26.7 billion and imports fell by £35.2 billion. As a result, the total trade surplus widened by £8.6 billion to 8.6 billion in Q2. The Bank of England base-rate that aims to maintain the government-set inflation target of 2% had been set at 0.75% in August 2018; this interest rate dropped to 0.25% on 11th March 2020 and fell to 0.1% on 19th March 2020 [64].

Other spillover effects

In addition to the direct impact on the UK health care service and economy, there have been several other spillover effects of the pandemic on the environment, crime rates, and on the sale and consumption of alcohol. Within the UK parliament, the Environmental Audit Committee has been tasked with exploring the environmental implications of the COVID-19 pandemic. The UK has seen a significant reduction in air pollution, driven primarily by the dramatic impact of the pandemic on travel and industry [65], including a reduction in pollution in the form of nitrogen dioxide (NO2) emissions, which are released upon the burning of fossil fuels in cars, airplanes and other engines. Data from the Air Quality Index showed that compared with 2019, emission levels were pointedly lower throughout the UK in April 2020 [66]. The greatest reductions were seen in more densely populated, and more industrialised regions of the UK. Several studies have identified associations of NO2 with mortality and disease incidence [67], [68]; highlighting the potential environmental and health benefits of the lockdown period.

The pandemic and resulting lockdown have also impacted on the UK crime rate. Provisional data released by 43 territorial police forces in England and Wales at the end of May 2020 (covering a four-week period) showed a reduction in recorded crime of 25% during the lockdown period, compared with the same period in 2019 [69]. With the public being urged to stay at home during lockdown, residential burglaries, vehicle crime, assaults, robbery of individuals, rape and shoplifting were all less prevalent than the same period in 2019. In contrast, a 4% increase in domestic abuse incidents was recorded.

The pandemic has also influenced alcohol consumption levels. At the onset of the pandemic, sales data from licensed premises indicated that the sale of alcohol rose rapidly as lockdown began [70]. Alcohol Change UK carried out a survey with a representative sample of over 2,000 adults to understand the impact of the lockdown on peoples’ drinking habits [70]. They reported drinking behaviours had changed: on the one hand, approximately 33% of people had either stopped drinking or reduced how often they drink since the onset of lockdown, with 6% being completely abstinent. However, 21% of respondents indicated that they were drinking more frequently, which equates to approximately 8.6 million UK adults. In terms of the amount consumed on a typical drinking day, 15% of respondents indicated that they had been drinking more per session since the onset of lockdown. These figures are of concern when considering the health-related implications of lockdown, particularly the association between excessive drinking and mental health problems [71], as well as physical health problems such as liver disease.

Concluding remarks

The COVID-19 pandemic in the UK is having a profound impact on the population. As of 12th August 2020, 46,706 people had lost their lives to COVID-19, which combined with the social distancing and lock-down measures imposed (unable to attend hospital during visiting hours and restrictions placed on funerals) had an incalculable emotional impact on their families. It is important to recognise that the pandemic is affecting groups in the population differently. Healthcare workers, social care workers, care home residents and those reliant on health and social care in the community, including other key workers (bus drivers, delivery personnel and retail staff) are at increased risk. Males in these groups, and males in the general public with ‘high-risk’ comorbidities aged over 60 years appear to be at highest risk of mortality from COVID-19. Other countries (USA, Spain, Netherlands, Italy and Germany) also have higher rates of death from COVID-19 in males than females [72]

COVID-19 survivors will have pressing mental and physical health needs. Many may have been living with an anxiety and depressive disorder prior to hospitalisation (1 in 6 adults each year will experience a common mental health disorder such as an anxiety or depressive disorder [18]), which will be exacerbated by the trauma of being diagnosed with COVID-19 and admitted to a respiratory ward or intensive care unit for ventilation. Those without pre-existing mental health conditions are at increased risk of developing an anxiety and/or depressive disorder associated with post-intensive care syndrome (PICS) [73]. At home they will face further isolation (denying them much needed ‘contact’ from family and friends). The prevalence of ICU-acquired weakness (ICUAW) is also likely to be high in COVID-19 survivors [75], which combined with the impact of PICS, may necessitate support with activities of daily living. These complex and inter-related psychological and physical health issues faced by COVID-19 survivors and their relatives/carers are salient barriers to mental health and physical health recovery.

The health system had unprecedented demands on intensive care unit space and equipment. Notwithstanding the importance of addressing the needs of COVID-19 survivors (which may contribute to an increased burden of disease and disability in the UK) there is likely to be increased mortality and morbidity over the short to medium term amongst people who are not directly affected by COVID-19 due to avoidance of help-seeking. Emergency care attendance has decreased, and social distancing / lockdown is likely to exacerbate and increase the prevalence of common mental health disorders (adults and children) and physical health conditions associated with high risk of death from COVID-19. The WHO have reported concerns about lockdown having a significant effect on obesity with restrictions on access to specific foods and levels of inactivity [5], which has implications for healthcare systems and technological solutions such as telemedicine that has been rapidly implemented across the primary and secondary care system.

The business and economic consequences have been catastrophic. UK policies such as the Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme and business interruption loans are available to employers; nevertheless, there have been a historically large number of people making applications for state benefits (Universal Credit). Invariably this will have an impact on health, potentially widening health inequalities [74]. Deprivation is symbiotically linked to health, and those at higher risk as a result of the pandemic (older people and low socioeconomic groups) have lower rates of access to the internet and highest prevalence of digital literacy, including reliance on state benefits. Lower socioeconomic and BAME groups have been disproportionally affected by COVID-19. The pandemic, and resulting lockdown, have also resulted in spill-over effects on the environment, crime rates and alcohol consumption. The impact on industry and travel has led to reductions in air pollution, and a fall in the crime rate. However, whether these effects are sustained after the lockdown period remains to be seen.

It is challenging to accurately quantify the economic and quality-of-life impacts of the pandemic. Recent research has been conducted to explore the costs and benefits associated with lockdown policies related to COVID-19 in the UK. In a paper published in August 2020, Miles et al. [75] carried out a cost-benefit analysis, focusing on the number of life-years saved, and the cost implications of the lockdown. Using data from June 2020, the authors estimated that the effects of the lockdown resulted in 440,000 net lives saved (at the high end of the estimate) to 20,000 net lives saved (at the low end of the estimate). The higher figure is based on the projected number of deaths without mitigation measures, proposed by Professor Ferguson's group at Imperial College [76], as well as the estimate of excess UK deaths at the time these data were captured. On the cost side, these authors estimated that the lockdown resulted in a GDP loss of between 9 and 25%, which in monetary terms is between £200-£550 billion. In order to compare the monetary costs of the lockdown with the benefits in terms of life-years saved, the authors multiplied the NICE-recommended willingness-to-pay threshold for a quality-adjusted life-year (£30,000) by the estimated number of lives saved, and the duration of those lives, and compared the overall costs. In all scenarios assessed, the authors reported that the economic costs of lockdown likely exceeded the benefits. It should be noted however, that there are several limitations to this modelling. By focusing on excess deaths at a specific point in time, the modelling considers only the known change in short-term mortality due to COVID-19 (and does not consider longer-term morbidity and the resulting impact on quality-of-life and life expectancy). Additionally, by focusing on GDP, and the range of costs related to COVID 19, morbidity are not considered. Further research is warranted to consider these limitations and more robust calculations will be possible once additional evidence becomes available.

At the time of writing, several key data were not available, or their recording was paused for irresolute reasons. Moreover, historic testing and death data were in the process of being revised. As outlined, several different policy and technology measures have been introduced in the UK since onset of the pandemic to prevent the spread of SARS-CoV-2, minimise the impact on health, and ameliorate long-term impact on the economy. Given that our paper includes data up to 12th August 2020 (and that the impact of policies / measures may take more time to partially or fully manifest), it is premature in our view to provide any recommendations on which policy (or policies in combination) have worked or not worked. Future research, informed by the findings of our paper, using for example, carefully designed interrupted time series analyses and health economic modelling is necessitated to explore relative impacts of policy/technological measures on a range of outcomes over the long-term. These studies will be best placed to understand the direct and indirect impact of COVID-19 on the health of the UK population, health system and economy, in order to implement the optimal policy and technological response to the current crisis and inform strategic planning to prevent future pandemics. It will be important for future epidemiological research to monitor these data across all four countries to better understand how different sections of society are affected by the pandemic and the subsequent easing of social distancing and lockdown measures that commenced in mid-June 2020, particularly as the four UK countries are doing so at different magnitudes and with different public health messaging.

Author Statements

Funding

None

Declaration of Competing Interest

None declared

Ethical approval

Not required

Acknowledgements

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and not necessarily those of their respective institutions.

| Box 1 – Phased Testing Programme in the UK [24] |

| Pillar 1: Swab testing in Public Health England (PHE) labs and NHS hospitals for those with a clinical need, and health and care workers. |

| Pillar 2: Swab testing for the wider population, as set out in government guidance (originally restricted to additional key workers before being extended). |

| Pillar 3: Serology testing to show if people have antibodies from having had COVID-19. |

| Pillar 4: Serology and swab testing for national surveillance supported by Public Health England, Office for National Statistics, Biobank, universities and other partners to learn more about the prevalence and spread of the virus and for other testing research purposes, for example on the accuracy and ease of use of home testing. |

| The number of tests is not equivalent to the number of people tested. Consequently, the number of tests is |

| higher than the number of people tested. For more information see [24] |

References

- 1.Worldometer. U.K. population (LIVE) [Internet]. 2020; [Updated daily]. Available fromhttps://www.worldometers.info/world-population/uk-population/.

- 2.Office for National Statistics. Overview of the UK population:august 2019. United Kingdom, 2019. [Last updated 23 August 2019]. Available fromhttps://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/populationestimates/articles/overviewoftheukpopulation/august2019.

- 3.Office for National Statistics. Families and households in the UK:2019. United Kingdom, 2019. Available fromhttps://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/families/bulletins/familiesandhouseholds/2019.

- 4.MHA. Facts & Stats[Internet]. 2020. Available fromhttps://www.mha.org.uk/news/policy-influencing/facts-stats/.

- 5.World Health Organisation. Information note on COVID-19 and noncommunicable diseases. 2020. Available fromhttps://www.who.int/internal-publications-detail/covid-19-and-ncds.

- 6.Intensive Care National Audit and Research Centre ICNARC Case Mix Programme Database. 24 July 2020 doi: 10.1186/cc6141. https://www.icnarc.org/Our-Audit/Audits/Cmp/Reports Available from. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Istituto Superiore di Sanità. Characteristics of COVID-19 patients dying in Italy. Italy. 2020. Available fromhttps://www.epicentro.iss.it/coronavirus/bollettino/Report-COVID-2019_20_marzo_eng.pdf.

- 8.Diabetes UK. Diabetes Facts and Stats: 2015[Online]. United Kingdom, 2015. [cited 29 April 2020] Accessed from Diabetes Facts and Stats: 2015.

- 9.NHS Digital. Health Survey for England 2017 [Internet]. United Kingdom, 2018. [cited April 2020]. Available fromhttps://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/health-survey-for-england/2017.

- 10.Bhaskaran K. Body-mass index and risk of 22 specific cancers: a population-based cohort study of 5·24 million UK Adults. Lancet. 2014;384:755–765. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60892-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Public Health England. Obesity and disability: adults. London: UK, 2013.

- 12.Cancer Research UK. Tobacco Statistics. United Kingdom2020. Available fromhttps://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/risk/tobacco#heading-One.

- 13.National Health Service England. Statistics on smoking, England -2019. England, 2019. Available fromhttps://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/statistics-on-smoking/statistics-on-smoking-england-2019.

- 14.National Health Service England. Statistics on Alcohol, England2020. England, 2020. Available fromhttps://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/statistics-on-alcohol/2020.

- 15.UK Chief Medical Officer. Annual report of the Chief Medical Officer, 2018 health 2040 – better health within reach. [Online]. United Kingdom, 2018. [cited 28 April 2020]. Accessed fromhttps://www.gov.uk/government/publications/chief-medical-officer-annual-report-2018-better-health-within-reach.

- 16.Public Health England. Physical activity: applying All Our Health. England, 2019. Available fromhttps://www.gov.uk/government/publications/physical-activity-applying-all-our-health/physical-activity-applying-all-our-health.

- 17.Mental Health Taskforce NE. The five year forward view for mental health. 2016[cited 2017 May 23]; Available from england.nhs.uk.

- 18.McManus S., Bebbington P., Jenkins R., Brugha T. Mental health and wellbeing in England: adult psychiatric morbidity survey 2014 [Internet] Leeds. 2016 Available from content.digital.nhs.uk. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baker C. House of Commons Briefing Paper; Jan 2020. Mental health statistics: prevalence, services and funding in England.https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/sn06988/ Number 6999, 23rd. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Finder. Health Insurance Statistics. [Internet]United Kingdom. https://www.finder.com/uk/health-insurance-statistics.

- 21.Office for National Statistics Healthcare expenditure. UK Health Accounts: 2017 https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/healthcaresystem/bulletins/ukhealthaccounts/2017 2019. Available from. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Public Health England. COVID-19: investigation and initial clinical management of possible cases [Internet]. England, 2020. [Accessed 27 April 2020] Available fromhttps://www.gov.uk/government/publications/wuhan-novel-coronavirus-initial-investigation-of-possible-cases/investigation-and-initial-clinical-management-of-possible-cases-of-wuhan-novel-coronavirus-wn-cov-infection#criteria.

- 23.Menni C., Valdes A.M., Freidin M.B., Sudre C.H., Nguyen L.H., Drew D.A., Ganesh S., Varsavsky T., Cardoso M.J., Moustafa J.S., Visconti A. Real-time tracking of self-reported symptoms to predict potential COVID-19. Nat Med. 2020;11:1–4. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0916-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Department of Health and Social Care. Guidance, COVID-19 testing data: methodology note. United Kingdom, 2020. [cited 2 June 2020]. Available fromhttps://www.gov.uk/government/publications/coronavirus-covid-19-testing-data-methodology/covid-19-testing-data-methodology-note.

- 25.Loke Y.K., Heneghan C. Centre for evidence-based medicine. University of Oxford; 2020. Why no-one can ever recover from COVID-19 in England – a statistical anomaly [Internet]https://www.cebm.net/covid-19/why-no-one-can-ever-recover-from-covid-19-in-england-a-statistical-anomaly/ [cited on 19 July 2020]. Available from. [Google Scholar]

- 26.UK Government. Number of coronavirus (COVID-19) cases and risk in the UK [Internet]. England, 2020. Available fromhttps://www.gov.uk/guidance/coronavirus-covid-19-information-for-the-public.

- 27.UK Government. Coronavirus (COVID-19) in the UK [Internet]. England, 2020. Available fromhttps://www.coronavirus.data.gov.uk.

- 28.Scottish Government. Total Scotland COVID-19 Cases [Internet]. Scotland, 2020. Available fromhttps://www.arcgis.com/apps/opsdashboard/index.html#/658feae0ab1d432f9fdb53aa082e4130.

- 29.Welsh Government Public health wales health protection – profile [Internet] Wales. 2020 https://public.tableau.com/profile/public.health.wales.health.protection#!/vizhome/RapidCOVID-19virology-Public/Headlinesummary Available from. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Department of Health, Northern Ireland. COVID-19 Daily dashboard updates. [Internet]. Available fromhttps://www.health-ni.gov.uk/articles/covid-19-daily-dashboard-updates.