Abstract

Given the unprecedented challenges imposed on the aviation industry by the COVID-19 pandemic, this paper proposes a new perspective on airport user experience as a field of study to unlock its potential as a basis for strategic roadmapping. Through an integrative literature review, this study points out a dominant focus, in practice and research, on customer experience and service quality, as opposed to user experience, to help airports gain a competitive edge in an increasingly commoditized industry. The review highlights several issues with this understanding of experience, as users other than passengers, such as employees, working for the airport and its myriad stakeholders, as well as visitors, are largely omitted from study. Given the complexity of the system, operationally, passengers are generally reduced to smooth flows of a passive mass, which this study argues is both a missed opportunity and a vulnerability exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Major events apart from COVID-19 are used to show the negative effects this simplification of user experience has had. Based on solutions and models proposed in previous studies, a conceptual model has been developed to illustrate the postulated potential of a deeper and more holistic study of airport user experience to make airport systems generally more agile, flexible and future-proof. As such, the paper advocates to utilize the user experience as a basis for strategic planning to equip airports with the know-how to manage not just daily operations more effectively but also the aftermath of and recovery from major events like the COVID-19 pandemic. Moreover, with the user experience at the center of the strategic roadmap, airports can plan ahead to mitigate the impact of future scenarios. The importance of future research and the use of existing research are discussed.

Keywords: Aviation, Airport systems, User behaviour, Passenger experience, VUCA, Product-service system, Coronavirus pandemic

Highlights

-

•

Airport user experience has been proposed as a key strategic planning tool for post-COVID Aviation.

-

•

Volatility, Uncertainty, Complexity, Ambiguity environments require systemic focus.

-

•

Study highlights ‘passenger experience’ dominated the discourse in the past.

-

•

A conceptual model has been developed to present the potential of the Airport User Experience.

-

•

Flexible and resilient systems planning must focus on airport as the 'experience providers’ for all users.

1. Introduction: COVID-19, VUCA, airports, and experience

The coronavirus pandemic has turned commercial aviation on its head and the experience at the world's airports has changed drastically. Newspaper articles and social media have been swarming with impressions of travelers, such as reports about long queues – potential disease transmission hotspots – at underprepared, and at times overcrowded, airports around the world. If figures for the reduction in flight movements and lost revenue form the quantitative basis, the experience is the qualitative measure to report on and capture this extraordinary situation. Amid all the uncertainty, grasping what is happening is key to planning ahead – early predictions have already been proven wrong. In early March 2020, for example, news reports still compared the potential COVID-19 impact on air travel to that of 9/11 (e.g. Smith, 2020; Taylor, 2020), but with the recent exponential growth of cases all over the world, the impact is already more severe. Recovery scenarios are being widely discussed, some implying severe damage, others being more optimistic (Smit et al., 2020). As of now, there is no consensus on the immediate future of the aviation sector; Delta Airlines, e.g., appears not to expect a full recovery within the next three years, while expecting an increased demand in premium service (Unnikrishnan, 2020). McKinsey & Company, conversely, argue for an increased demand in low-cost offerings during the recovery, illustrating the ambiguity of the current situation (Curley, 2020). Whether the recovery will take five years (see Ali, 2020), three, or six, we need to understand what is happening and what might happen in order to prepare our airports and airlines for the uncertain future in order to protect jobs and livelihoods; a PhocusWire headline in early April read: “There are no winners in all this, only survivors, say investors (Trew, 2020).”

We propose to view airports as experience providers and to use the experience of all airport users as a key factor for not just survival but mapping the way through the recovery and beyond. User Experience makes a great deal of items palpable: from inconvenient departure/arrival times due to slot allocation, to inadequate security planning, to poorly laid out terminals, to a stressful work environment for employees, etc. As such, the user experience connects most, if not all, elements of the system (build environment, technologies, operations, and services) and would thus be the perfect resource to tap into in order to understand the airport system and form a basis for strategic planning involving all stakeholders.

While the scale of this crisis for air travel is unprecedented, the elements of VUCA (Volatility, Uncertainty, Complexity, Ambiguity) have always been looming over the industry; the air transportation landscape has consistently proven itself to be a dynamic one; change has been a constant. Despite strong long-term growth, even record-breaking increases in passenger numbers in recent years (ICAO, 2018), the forecasting thereof has been noted to be rather unreliable (Odoni and de Neufville, 1992; de Neufville, 1995). The effects of the de-regulation of the industry and the evolution of low-cost carriers (De Neufville, 2008; Causon, 2011) in particular, have left their mark. Competition between airports as transfer points, as well as between airlines – along with consolidation, climate change, rising oil prices – have caused further uncertainty for future developments and rendered the market more volatile (de Neufville, 1995; Rothkopf and Wald, 2011). Add to that terrorism – it took almost three years for demand to bounce back to its peak prior to 9/11 (see Ito and Lee, 2005; Notis, 2005) – and natural disasters like the Eyjafjallajökull eruption (see Woolley-Meza et al., 2013; Oxley, 2016), and VUCA seems ever present. One can learn from the experience during these past examples and the current situation in order to improve airport user experience in general, manage the recovery from, and prepare for major events beyond COVID-19.

To advocate for a paradigm shift utilizing the full potential of user experience and a holistic understanding thereof as a tool for strategic planning, this study is based on an integrative literature review with three goals: to analyze the current understanding of experience in an airport context, to identify the underlying problems with regard to the issues the industry is facing, and to develop a conceptual model leading towards solutions to these problems in light of the current aviation crisis caused by COVID-19.

2. Experience in the airport context

2.1. Passenger satisfaction as a competitive advantage

Experience in an airport context is generally understood to mean passenger experience. This focus is by no means surprising; satisfied passengers give the airport a competitive advantage (see Fodness and Murray, 2007; Tsai et al., 2011). In an industry that nowadays could very well be considered commoditized (see Rothkopf and Wald, 2011; Pine and Gilmore, 2013), the experience is a measure to set one airport apart from competitors in their “catchment area” or from “alternative transfer hubs” (de Neufville, 1995; Jimenez et al., 2014). Airport managers too have pointed out the importance of passenger satisfaction for their business; satisfied passengers could be return customers and help attract more passengers – and through this more airline customers for airports (see Lehmann, 2019).

As such, a focus on airport experience and airports as service providers fits in with general developments in the services sector. In 1982, in an emerging service industry, G. Lynn Shostack highlighted the differences between products and services and first proposed blueprinting services. One of the examples given was for a shoe-shining service, in which the blueprint outlined the elements of service, failure points etc. (Shostack, 1982). This outlined the mechanics and strategic planning of a service; however, in a changing business landscape, the experience of the service gained importance. In 1999, Joseph Pine and James Gilmore expanded the shoe-shining service example in light of what they coined the “experience economy.” They wrote about “sensory stimulants that accompany an experience” and argued for the importance of catering to all senses – “scents and sounds that don't make the shoes any shinier but do make the experience more engaging” (Pine and Gilmore, 1999). Airports are part of this “experience economy; ” they can no longer just render services; they must focus on experience. Many airport-related studies, regardless of their individual specific points of focus, therefore choose to include ‘experience’ in their title (e.g. Sykes and Desai, 2009; Harrison et al., 2012; Jiang and Zhang, 2016; Wattanacharoensil et al., 2016; Rossi et al., 2018).

2.2. Assessing service quality

Passenger experience is closely related to the (perceived) quality of services provided and therefore most frequently studied through the domain of service quality – which was also found to be linked to service productivity (see also Parasuraman, 2010; Lehmann, 2019). Several measures exist for airports to assess their own respective service quality. Among the most prominent ones is the Airport Service Quality (ASQ) survey issued to its members by the Airports Council International (ACI), and ‘authored’ by market research firm DKMA (O'Doherty, 2017). The ASQ program is described by the ACI as “the world-renowned and globally established global benchmarking program measuring passengers' satisfaction whilst they are traveling through an airport” and as “the key to understanding how to increase passenger satisfaction and improve business performance. ASQ research is in place in airports that serve more than half the world's 7.1 billion annual passengers […] (ACI, 2020)” The survey seeks to address how passengers rate a specific airport, how the airport performs in the service quality field compared to other airports, passengers' priorities and how they change over time, etc. (ibid.) Similarly, the Skytrax World Airport Awards and corresponding survey (www.worldairportawards.com), along with the data from other online review platforms, can be used for service quality benchmarking (see Lee and Yu 2018; Straker and Wrigley, 2018; Martin-Domingo et al. 2019). Of course, airports also conduct their own internal assessment of service quality through feedback channels for complaints, e.g. Singapore Changi Airport's “Service Workforce Instant Feedback Transformation” (or SWIFT) system that lets passengers rate a specific aspect, such as toilet cleanliness, directly after use via touchscreen (Coutu, 2013; Lehmann, 2019).

Most academic studies of passengers' experiences at airports have also been conducted within the context of service quality. Since the early 2000s, when these studies began to emerge (e.g. Rhoades and Young, 2001; Chen, 2002; Yeh and Kuo, 2003, see Fodness and Murray, 2007), many researchers have followed in the footsteps of Parasuraman, Zeithaml, and Berry (Parasuraman et al., 1985) who pioneered the SERVQUAL method in 1985 – when service quality was not yet well understood. It offered insights into how service quality is made up of perceived quality and expectations and helped to analyze the gap between these. It has been extensively used until today, to study the discrepancies between passengers’ expectations, the actual service quality, and the perception thereof at airports (Fodness and Murray, 2007; Tsai et al., 2011; Yang et al., 2015; Jiang and Zhang, 2016; Gani et al., 2019).

While the research related to SERVQUAL takes a broader look at multiple factors, others have studied singular phenomena inside airport terminals that influence the satisfaction, service quality, and thus experience in greater detail. These include, among others, biometric security technology (Sasse, 2002), the security screening process as a whole (Gkritza et al., 2006), self-service check-in (Chang and Yang, 2008; Castillo-Manzano and López-Valpuesta, 2013), mobile technologies and solutions (Inversini, 2017; Rossi et al., 2018), as well as retail experience and passengers’ shopping motivations (Crawford, 2003; Lin and Chen, 2013). The modeling of airport choice and the factors that influence it has also been a direct subject of study (Başar and Bhat, 2004; Blackstone et al., 2006; de Luca, 2012; Wiltshire, 2018).

These topics and the results from the broader service quality research point to a variety of issues, e.g. dissatisfaction with airport parking, immigration, internet/Wi-Fi access, or baggage delivery at specific airports (e.g. Jiang and Zhang, 2016), or neglect on the part of the airport in caring for passengers with mobility issues or other disabilities (Sykes and Desai, 2009; Chang and Chen, 2012). Given this multiplicity of factors involved, newer methods have been proposed to assess airport service performance that can cover the entire passenger experience including all passenger activities, the importance and interlinkage of certain factors for the overall experience, as well as passenger and airport characteristics (Wiredja et al., 2019). The goal, however, is still largely the same: improving service quality, or individual factors influencing the passenger.

3. Shortcomings of the existing experience paradigm in a VUCA environment

3.1. Passenger experience vs. user experience

Service quality is not a simple field and the perception thereof is influenced by a plethora of factors, such as ambiance (see Fodness and Murray, 2007), themselves difficult to define. While this influences passenger experience, we are interested in user experience, which is a much broader concept. Airports have many users: passengers, visitors, meeter-greeters, bus, taxi, or private hire drivers, employees working for the airport company itself, or for the airlines, the shops, restaurants, government agencies, etc. Yet, with the exception of passengers, these users are largely ignored and studies focusing on all users are rare (see Appendix-1). Their experiences, however, are equally relevant, both in their own right, and for their direct or indirect effect on passenger experience. The experience of employees, for example, seems largely unexplored outside the field of airport security, unless there is a concrete issue, such as employee road traffic congesting airport access (Humphreys and Ison, 2005; Ison et al., 2007). However, to ensure the system operates effectively, the perspectives of all users and their dynamic interactions are valuable (Wales, O'Neill et al., 2002). In the case of passengers with disabilities, the employees' perception and understanding of these passengers are particularly insightful and crucial to the management of both parties' experience (see Chang and Chen, 2012).

Recent articles published by McKinsey & Company and the ACI have argued that the employee experience is of great importance, especially now (Coll, 2020, Diebner et al., 2020). Precedent from the VUCA environment of airports further backs this argument. After the SARS epidemic of 2003, five infection control professionals (ICPs) from Australia published their experiences at Sydney's Kingsford Smith, or Mascot, Airport [SYD/YSSY], detailing how screening nurses at the airport found themselves in roles not related to their usual jobs, and how Australian Quarantine and Inspection Service (AQIS) staff with almost no experience with health issues of this scale needed to grapple with their own fear and learn to gain the confidence necessary to manage the situation (Smollen et al., 2003). Heightened anxiety caused a series of over-reactions whenever travelers sneezed or coughed, leading ultimately to scared passengers (Smollen et al., 2003). Similarly, in the context of COVID-19, a frontline employee is exposed to many more people than an individual passenger, increasing their likelihood to be infected as well as the chance that they will infect others. This affects the behaviour and experiences of both. In a more severe example, albeit one related to airlines not airports, following 9/11, a lack of understanding of the employee experience alienated deeply affected and vulnerable airline employees who felt their employer had not taken care of their emotional needs (North et al., 2013). Of course, even in day to day operations, airport employees face stressful situations, especially those responsible for security. However, this human and emotional component appears to be ignored in operational planning and design. Instead, the focus is placed on procedural planning, disregarding that employees are part of big social networks, rely on group decisions, and sometimes bend or break rules (Kirschenbaum, 2015).

3.2. Passive cogs and smooth flow

Employees are largely seen as “cogs” in the complex airport system (Kirschenbaum, 2015). Notwithstanding the more prominent role the passenger experience – or at least satisfaction –plays, passengers too appear to be seen as “passive cogs” from an operational perspective, owing to the process-oriented nature of airports as complex engineering and logistics systems (see Horonjeff, 2010; Kirschenbaum, 2015). Much of the focus is directed towards the notion of a smooth flow. In some cases, this “smooth flow” was found to be directly linked with “positive passenger experiences” (see Popovic et al., 2010). A guide to terminal architecture and planning offers the following view: “The needs of passengers should be paramount in the design of terminal facilities. Passenger and baggage flows should be as smooth, well marked and flexible as possible” (Edwards, 2005). While proper planning no doubt ideally results in a smooth flow that can make users happy, the link is not as simple and straightforward. In fact, the implied cog-like nature of passengers as inanimate objects in relating passenger flow to baggage flow can be rather problematic. Findings from British airports, e.g., show that passengers frequently felt “processed” and found their needs to come after those of the airport and airlines (Sykes and Desai, 2009). The operational reduction of passengers to a passive mass inevitably disregards important “softer factors which cannot easily be measured by typical performance indicators” and partially removes the important “feeling of personal control” (ibid.). The notion of the passive traveler is also prevalent in the planning of the built environment, which is often formulaic and has little regard for the reality of human behavior; spaces are often not adequately sized because planners simply assume that users will “disperse like a gas” to use the entire floor area equally, instead of congregating around points of interest, as they naturally do (see Odoni and de Neufville, 1992).

A flow of passive users also presupposes a routine, which as the current pandemic shows, is not in line with the VUCA nature of airports and air transport. Flows are frequently not smooth for myriad reasons, individual behaviour being one of those. Knox et al. noted that “matter becomes ‘charged’ with volatility and uncertainty. Sometimes a bag or a passenger will suddenly become a security alert, or a security threat might become a ‘customer’. […] Flow can very rapidly become sticky and congealed or ‘delaminated’, degenerating into flux instead of the ideal of fluidity and smooth transformation […]” (Knox, O'Doherty et al., 2008). Whether it is because of bomb threats, sudden COVID-19 related travel restrictions, or others, flow can at any time “suddenly [turn] into overflow […]” (Knox, O'Doherty et al., 2008). As passengers are not inanimate objects, cogs, or gases, the flowing mass imagery creates several issues. Wales et al. pointed towards the “operation system [as being] designed as a production system based on the assumption of the routine air travel event” (Wales, O'Neill et al., 2002). Therefore, operationally, everything is hinged on the expectation that passengers efficiently flow through the airport system and on-time departures are the norm; the participatory nature of services (see Shostack, 1982) is largely ignored (Wales, O'Neill et al., 2002). The airport and airline industry in general is trimmed for this efficiency, making it vulnerable when things do not go according to plan (see Woolley-Meza et al., 2013). The same notion of a standard scenario is commonly assumed for terminal design as well, largely ignoring the myriad scenarios that could happen (Odoni and de Neufville, 1992).

3.3. A complex net of stakeholders and disciplines

The simplification of employees to “cogs,” passengers to flows, narrowing the experience to service quality, and, ultimately, absence of holistic studies involving all airport users, are understandable given the convolution of airports systems. Airport companies themselves are complex organizations (see Knox, O'Doherty et al., 2008; O'Doherty, 2017) that have to work closely with other stakeholders such as airlines, baggage handling and ground service providers, retail and food services companies, and regulatory authorities such as government bodies (see Gourdin, 1988). Passengers and even employees are generally unaware of where the “specific responsibilities of ‘the airport’ start and finish, in comparison to those of an airline, a third party contractor, or a state agency (O'Doherty, 2017).” The airport environment has to cater to these entities, while at the same time satisfying the needs of all users: passengers, visitors, and employees of all companies involved. This is a balancing act, as the needs of stakeholders, e.g. strategic objectives of airlines and airports, are not always the same (Van Der Zwan, Santema et al. 2009), which can lead to a refusal to “share details and insights about their operations with parties whose commercial interests are not completely aligned (Lehmann, 2019).” In research too, many disciplines are involved. Moreover, research and analysis methods from the service industry at large may not always be easily applicable in the airport context (Lehmann, 2019) and form too narrow a perspective on user experience. As mentioned earlier, user experience is affected by the build environment, technology, operations and services, other users, and characteristics (see Desmet and Hekkert, 2007) of the user themself.

4. Unlocking the potential of the airport user experience

4.1. Learning from the VUCA world

As the user experience is connected to the entire airport environment, it offers the opportunity to exert influence on the individual components of the airport system, rather than be influenced by them. Fortunately, some non-airport-related studies already present approaches for solutions that use user experience holistically instead of providing “piecemeal approaches.” At the same time, they offer economic incentive, by showing that a fresh look at user experience can contribute to future-proofing companies in the face of VUCA. A design roadmapping concept (Kim et al., 2018), shows how grounding all planning in the design of the customer experience provides an agile and adaptive way to keep satisfied customers as a constant while other variables, such as technology, change (Millar et al., 2018). Tools like this help anticipate needs of customers in order to “stay ahead of surprises” (Millar et al., 2018). In times like these, for flexibility's sake, it is crucial to link strategic planning to the experience sought to be provided. “In a VUCA world, it will become increasingly critical for companies to anchor strategic planning in the customer experiences it seeks to create (Kim et al., 2018).” Even before COVID-19, it has been argued that “integrated approaches” need to be taken to put the customer and his/her experience at the center of the business development and management (Millar et al., 2018). As such, the experience has the potential to influence and contribute to every aspect of a business. It is our firm belief, however, that the latter requires extending this concept to include all users and not only customers.

4.2. Flexible, user-focused masterplanning

One aspect of the airport system that the experience as well as the VUCA elements touch upon besides services, operations, and technology is the built environment – flexibility naturally extends to terminals, other physical infrastructure, and the planning thereof. Here too, a variety of scenarios should be considered to be prepared and actively deal with new situations as they arise, resulting in flexibly planned systems (De Neufville and Scholtes, 2011). In uncertain times, where airports could either face growth without having space to grow, face growth and expand their infrastructure, or, as is the case right now, face a decline in passenger numbers, their masterplanning has been explored and assessed to offer flexibility (Magalhães et al., 2020). Designs could therefore be planned to be modular to react to these conditions and, for example, enable the airport to close off certain areas (De Neufville and Scholtes, 2011), as Changi Airport did when they announced the closure of Terminal 2 in April 2020 (Toh, 2020), and Terminal 4 in May (Eber, 2020). As mentioned, multiple scenarios need to be accounted for when planning airports (Odoni and de Neufville, 1992). On a smaller scale, flexibility within the built environment of the airport terminal can also allow for screening rooms or other isolation areas to deal with disease outbreaks, even though existing ones at Sydney, for example, have not been planned optimally (see Smollen et al., 2003). In addition, mobility of technology, the possibility to easily move technology where it is needed, can greatly increase flexibility in these cases.

The most promising way to anticipate a wide variety of situations is to plan from the perspective of the user – with the experience and expectations of all users as a guiding principle. The psychology and actual behaviour of users provide insights into what could play out in daily operations and should inform the design rather than the assumption of a passive mass of customers (see Odoni and de Neufville, 1992). As autonomous actors, travelers are naturally not products of an endless supply, thus focusing on them would incorporate an element of volatility, uncertainty, and ambiguity into the basis of planning. The volatility of the development of passenger numbers (see de Neufville, 1995), to name one example, would therefore need to be addressed. Rather than from intuition, the terminal design should be designed from a thorough understanding of its users. Based on this notion, albeit focusing on passengers as the users, Harrison et al. have proposed a conceptual model for terminal planning that has the experience at its core (Harrison et al., 2012). Owing to the complexity of the system, they take to different perspectives and their influence on the experience: the airport as the company that “stages” the experience (see also Pine and Gilmore, 1999), the passenger who expects and perceives it, and the public that aggregates several experiences into one. Approaching airport terminal design via such a conceptual model would take it beyond the cookie-cutter approach of architecturally dressing up a predefined system (see de Neufville, 1995), towards acknowledging passengers as intelligent actors that can have a say in the design of the system they use. However, as mentioned, employees (and others) also need to be considered as users; the built environment in all its facets has major implications on how they are able to do their job, even without extraordinary events taking place (see Bitner, 1992).

4.3. Modeling the airport user experience

Putting the passengers – or better yet, all users – at the center of such models for planning, perforce, likens the airport system to a product service system (PSS) (see Müller et al., 2009; Haase et al., 2017), designed with the user in mind. An understanding of and approaches to user-centric design and product-service system design could make valuable contributions to airport systems design, especially given the inherent flexibility of product-service systems (Müller and Blessing, 2007). The previously mentioned study by Wales et al. used to illustrate the problems within the airport context, is an early example of a promising interdisciplinary approach. It already offers a solution to mitigate them by looking at human-centered computing; they proposed to shift from the “production line” model to a “customer-as-participant perspective.” Using a “human-centered level of analysis,” the passenger is seen as an intelligent actor within the system as opposed to an object on a metaphorical conveyor belt. “Importantly, customers can affect the airline system immediately as they move through it, adapt to changes in situ, and negotiate new terms as changes occur, unlike in a marketing perspective, where customer requirements are predefined and static in a particular work system design at any point in time (Wales, O'Neill et al., 2002).” While the research objective here was primarily to determine ways to manage regular delays and improve operational reliability, the suggestions for solutions are quite pertinent, provided they are extended to all users.

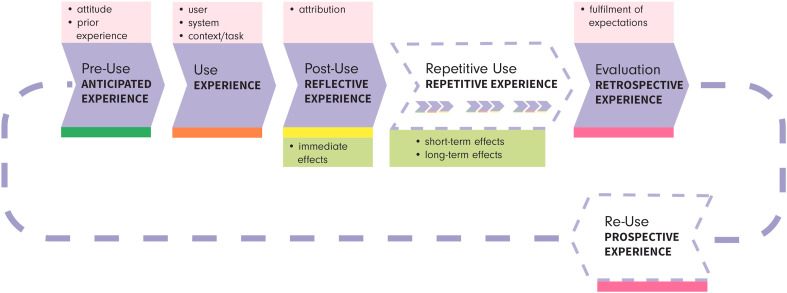

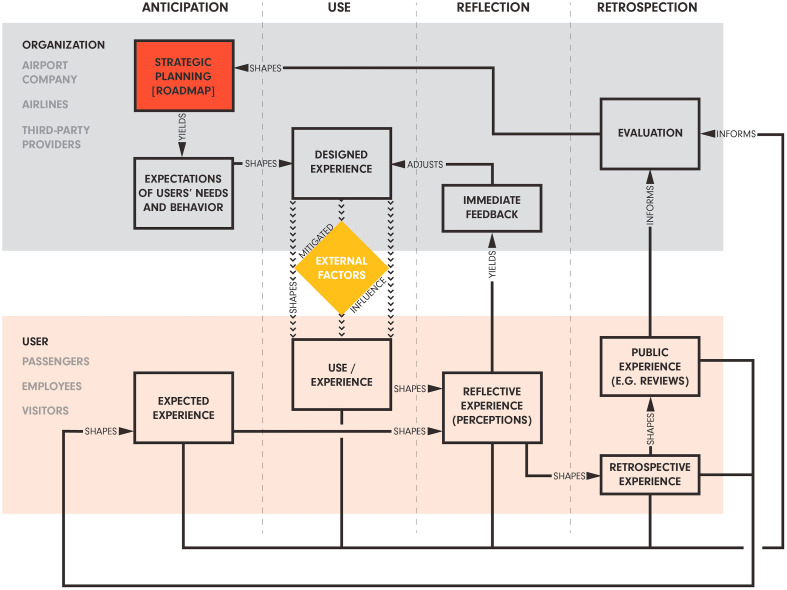

Outside the narrower airport context, there a re many approaches that can offer valuable insights. An experience-based model from outside the aviation realm, “ContinUE”, for example, goes beyond the expected and perceived experience and suggested a full temporal range of experiences (see Fig. 1 ): anticipated, use/experience, reflective experience, repetitive experience, and retrospective experience (Pohlmeyer et al., 2009). This model emphasizes that the experience is not merely a one-time occurrence. However, as models like this are not made for airports, they are never fully applicable. Models from within the airport context, on the other hand (e.g. Harrison et al., 2012; Wiredja et al., 2019) are aimed at just the passenger experience. Combining the notions of temporal range (Pohlmeyer et al., 2009), and expectations, perceptions, and perspectives (Harrison et al., 2012), we therefore developed a new conceptual model (see Fig. 2 ) to advocate for our proposed new perspective on airport user experience. It illustrates how studying the experience at all stages can inform the strategic planning to design the experience and mitigate the negative influence of external factors through proper roadmapping in iterative cycles through the following main features:

-

1

Two Perspectives: As an initial conceptual model, the information is simplified and condensed into to two perspective tiers, i.e. organization and user, so as not to deter from the main purpose: establishing user experience as a key factor in strategic planning for airports. At this initial stage, it would be presumptuous to break the organizational perspective up into more detailed sections without further research into the organizational structure. O'Doherty et al. have repeatedly pointed out the complexity of this subject matter (Knox, O'Doherty et al., 2008; O'Doherty, 2017). Likewise, accurately depicting all users and how their individual roles and characteristics influence the experience (Waltersdorfer et al., 2015), needs to be studied further in the airport context. Two perspectives are the simplest representation of who experiences, the users, and who “stages” (Pine and Gilmore, 2013) that experience, the organization. This does not imply a homogeneous mass but rather the need for a holistic approach. Data sharing, cooperation, and the alignment of strategic goals, as mentioned before, are key in the organization's tier, while the user tier must include all users for the strategic planning to be effective. As shown earlier, leaving out the knowledge that can be gained from the employee experience would not create a holistic understanding and in turn does not inform the strategic planning appropriately.

-

2

Temporal Segments: By acknowledging the temporal dimension of experiences as suggested by Pohlmeyer et al. the model illustrates that on the user side, expectations, use, and reflection form the actual perceived experience, while retrospection, other experiences and public opinion in turn shape the expectations, completing the cycle. At any point in time, information can be obtained to adjust the experience from the organizational perspective either through longer-term strategic planning or short-term interventions.

-

3

Iterative Model: The model links the temporal dimension with the organizational and user perspective and shows how the experience can be used to continuously shape the planning. The holistic and iterative nature of the model further carries with it an inherent continuous flexibility; there is no “new normal” for which this model forms a basis of understanding. Instead, it acknowledges constant changes in the face of VUCA – the external factors to be mitigated. As such, the changing experience repeatedly feeds back into both strategic planning for long-term adjustments, as well as into daily operations for immediate adjustments. The knowledge about today's COVID-19 experience, e.g., could be used to react immediately, as well as to plan ahead for the next pandemic via the strategic roadmap.

Fig. 1.

User experience lifecycle model ContinUE [Continuous user experience] (adopted from Pohlmeyer et al., 2009).

Fig. 2.

Conceptual model showing the potential influence of the experience on strategic planning.

5. Discussion and future direction

Volatility, Uncertainty, Complexity, and Ambiguity cannot be effectively managed with our current understanding of the airport experience and our productivity-oriented operations mindset. A conceptual model like the one proposed here, building on existing ones, suggests a new approach towards user experience. In addressing the shortcomings in our current understanding of airport user experience, it also capitalizes on the potential the experience offers. By developing a holistic understanding of the experience of all the airport users and putting this at the base of strategic roadmapping, along with the application of a combination of existing design concepts and methodologies, e.g. modularization, product-service systems, user-centered design, experiential design, etc., airport systems can be transformed into more flexible entities to counter the VUCA environment with inherent resilience. As the ‘Whether Man’ in Norton Juster's classic The Phantom Tollbooth put it: “Expect everything, I always say, and the unexpected never happens (Juster and Feiffer, 1961).” The current pandemic illustrates the need for this paradigm shift, which can be achieved by fully capitalizing on the user experience's inherent potential.

Conceptual models, however, are only starting points, not silver bullets. What is represented here is an illustration of potential and a way of thinking about the subject. This is initial conceptual model is merely a first step, an overarching concept, to inform the creation of more detailed ones; there is a need to combine the amassed knowledge into comprehensive, truly interdisciplinary models. Fortunately, plenty of research that has already been completed can be used to develop these. The passenger side already has a solid foundation in previous research, e.g. the work by Wiredja et al. However, these models also show just how complex even one part of the experience is. If we were to metaphorically zoom into the graphic, each field would reveal a net of numerous, potentially conflicting nodes – different and changing user needs, company goals, regulations, and contexts (technologies, built environment, procedures, services etc.). Ultimately, a lot more work needs to be done to capitalize on the potential – more research needs to go into the holistic modeling, the companies involved need to work together more closely, etc. Each field in the model represents a well of knowledge that needs to be attained to craft less conceptual and more detailed models that can be used to directly inform strategic planning.

It is important to note, that more research needs to be conducted, particularly with regard to the concrete implementation of these strategies. While there are many commonalities between the thousands of airports worldwide and their respective organizational ecosystems, the actual makeup of stakeholders, which aspects of the user experience they are directly and indirectly connected to, and the contracts outlining the responsibilities between them can be vastly different. Therefore, the parties involved in authoring the strategic roadmap for an airport, and thus incorporating the user experience into the process, may vary depending on how and by whom an airport is run. In the case of US airports, for example, where airlines play a considerable role in the running of terminals, the different types of contracts between airports and airlines and their impacts on the system have been researched (see Fuhr and Beckers, 2009; Hihara, 2012). Involving more stakeholders than just airport companies and airlines, the decision-making process in this complex environment has also been studied (e.g. Zografos and Madas, 2006). Along those lines, the strategic roadmapping from an experience point of view must be studied more thoroughly to involve different governance models. At this point in time, however, what can be said is that no matter the exact makeup of a specific airport's ecosystem, cooperation between all parties involved (see Zografos and Madas, 2006, Van Der Zwan, Santema et al. 2009) is crucial in achieving the paradigm shift advocated in the proposed conceptual model. Within the current makeup of airport companies, customer service departments are closest to dealing with user experience as we understand it. However, given that the current understanding and simple focus on “mere” passenger satisfaction has been deemed insufficient in this paper, their hierarchical positioning will likely not enable them to exact meaningful changes in the system (see Coutu, 2013). Whether an airport is fully government-owned or run by a private company, it may benefit from creating a managerial position to oversee user experience, as well as its translation into strategic planning and the resulting necessary coordination with corporate (and governmental) stakeholders. Overall, realizing the proposed model will require structural and strategic changes within the airport ecosystem to revamp the way experience has been delivered thus far.

For a truly holistic picture, further research also needs to aim towards uncovering the experience of hitherto ignored user groups. While publications concerning the system's vulnerabilities and previous major events help illustrate how passengers and certain employees are affected, other airport users, are almost entirely missing, even in the wider literature, apart from perhaps meeter-greeters (e.g. Budd, 2016),. This illustrates a lack of understanding of important users. Apart from counter staff, there are many other employees, albeit some less visible to passengers, who make vital contributions to the experience of everyone: cleaners perform functions especially vital during a pandemic. Baggage handlers at one airport can play a part in the experience at both their airport and another destination airport, if a bag goes missing. Furthermore, a bad airport experience for flight attendants, leaving them disgruntled, could potentially even translate to a bad flight experience for passengers. These are just a few examples of users that have not been adequately studied as such before. Not necessarily influencing other users' experiences, non-flying visitors also form a varied user group and are part of the larger airport context – which may include a business hub or a residential area. With developments such as Squaire in Frankfurt or Jewel at Changi Airport in Singapore, the non-passengers, become an important part of the airport ecosystem and, while they are not tied to operational vulnerabilities, they are essentially linked to an airport's economic performance. Despite the lack of mentions in literature, it is logical to assume that failure to understand these users' needs in times of a pandemic, such as the current one, can cost an airport valuable non-aviation revenue. A thorough understanding thereof may help maintain a local revenue stream, despite drastically reduced flight numbers.

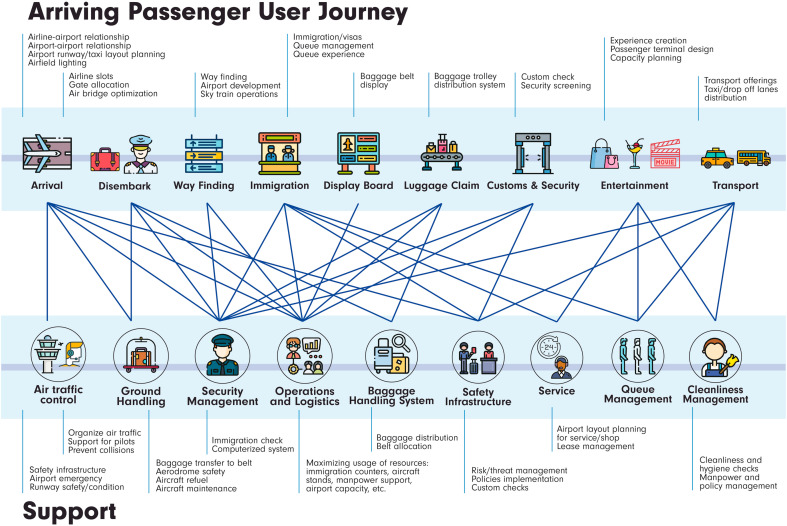

The experience weaves through the airport ecosystem and its stakeholders and users, connecting dots that traditionally may not have been seen as connected. The cleaning personnel, the ramp agent, the architect, the customs officer, the taxi driver, the meter-greeter, among other users may not interact directly, but they all experience the same airport system through its built environment, technologies, services, and procedures. All of them can therefore be connected to each other's experience (see Fig. 3 for an example of the connections to an arriving passenger's user journey). The same plethora of factors that makes the experience difficult to grasp and hard to study therefore makes it rewarding to do so. As such, a shift in approaching the subject can also help to connect existing and emerging research in new ways and lead to interdisciplinary solutions. While the study of technological, built environment and procedural solutions, as those mentioned earlier, are largely intended to improve passenger satisfaction, optimize the passenger flow in the airport, etc. they too offer the potential of connecting more dots in a holistic picture. Some of the previously proposed technologies could, for example, be used in times like these to relay information about queue times not to decrease waiting and increase spending, but to prevent the potential spread of a disease while queuing.

Fig. 3.

User journey for an arriving passenger and system connections.

Given the complexity of the airport system and the number of players involved, effectively using all knowledge, whether it has been acquired already or not, will not be an easy task. Nevertheless, the first step, as argued here, is changing the point of view from a top-down approach (from planning to airport user experience) to a bottom-up approach that shapes planning from a well-informed, holistic experience perspective.

6. Conclusion

The current COVID-19 pandemic has had unprecedented effects on the aviation sector. At the heart of it, the experience inside the airports has changed drastically. A closer look at our understanding of airport experience has shown that it is traditionally linked to passenger satisfaction and service quality to boost airport's competitiveness. Apart from several psychological studies, the employee or other users' perspectives are largely absent. While the majority of passengers may benefit from airports vying for their business through better amenities and the like, on an individual level, a significant proportion of them are, no doubt, also left out. Furthermore, narrowing down the experience to a smooth flow of satisfied passengers in operations and planning is a missed opportunity. In an industry that, depending on when you look at it, has to cope with massive growth, or can be turned upside down by terrorism, natural disasters, pandemics, and/or global recessions any time, a largely productivity-centered mindset means ignoring valuable insights that could help with prevention and mitigation of effects. The conceptual models discussed and the one proposed in this study show that there is great potential in the deeper and more holistic study of airport user experience. Airport systems can be made more agile, flexible, and resilient by embedding an understanding of what has happened, is happening, and what might happen in the day-to-day reality into strategic decisions for the future. While a holistic understanding of airport user experience is no deus ex machina to swoop in and magically save the world's airports in the face of major events – it will be hard work – it can, through proper planning, lead to resilient roadmaps to weather the VUCA elements.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Stefan Tuchen: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Mohit Arora: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Lucienne Blessing: Supervision, Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Validation, Writing - review & editing.

Declaration of competing interest

None.

Acknowledgement

This research was supported by the SUTD Growth Plan Grant for Aviation, Ministry of Education, Singapore. Authors would like to thank the reviewer(s) for constructive suggestions to improve the manuscript and SUTD undergraduate student Jesslyn Woo for help in improving the graphics.

Appendix 1. Previous studies related to airport user experience and their main user focus

| Author(s) (Year) | Title | Users in Focus |

|---|---|---|

| Theme 1: Airport Service Quality | ||

| Crotts and Erdmann (2000) | Does national culture influence consumers' evaluation of travel services? A test of Hofstede's model of cross-cultural differences | Passengers |

| Rhoades and Young (2001) | Developing a quality index for US airports | Passengers |

| Chen (2002) | Benchmarking and quality improvement: A quality benchmarking deployment approach | Passengers |

| Yeh and Kuo (2003) | Evaluating passenger services of Asia-Pacific international airports | Passengers |

| Fodness and Murray (2007) | Passengers' expectations of airport service quality | Passengers |

| Sykes and Desai (2009) | Understanding Airport Passenger Experience | Passengers |

| Tsai et al. (2011) | A gap analysis model for improving airport service quality | Passengers |

| Chang and Chen (2012) | Meeting the needs of disabled air passengers: Factors that facilitate help from airlines and airports | Passengers and Employees |

| Bezerra and Gomes (2015) | The effects of service quality dimensions and passenger characteristics on passenger's overall satisfaction with an airport | Passengers |

| Yang et al. (2015) | Passengers' Expectations of Airport Service Quality: A Case Study of Jeju International Airport | Passengers |

| Jiang and Zhang (2016) | An assessment of passenger experience at Melbourne Airport | Passengers |

| Kurniawan et al. (2017) | Passengers' Perspective toward Airport Service Quality (ASQ) (Case Study at Soekarno-Hatta International Airport) | Passengers |

| Gani et al. (2019) | Determining Priority Service of Yogyakarta Adisutjipto Airport Using Servqual Method and Kano Model | Passengers |

| Lehmann (2019) | Exploring service productivity: Studies in the German airport industry | Passengers (and Management) |

| Wiredja et al. (2019) | A passenger-centered model in assessing airport service performance | Passengers |

| Theme 2: Airport Choice | ||

| Başar and Bhat (2004) | A parameterized consideration set model for airport choice: An application to the San Francisco Bay Area | Passengers |

| Blackstone et al. (2006) | Determinants of airport choice in a multi-airport region | Passengers |

| de Luca (2012) | Modeling airport choice behaviour for direct flights, connecting flights and different travel plans | Passengers |

| Wiltshire (2018) | Airport competition: Reality or myth? | Passengers (and Airlines |

| Theme 3: Airport Security (Human Factors) | ||

| Gkritza et al. (2006) | Airport security screening and changing passenger satisfaction: An exploratory assessment | Passengers |

| Pütz (2012) | From non-places to non-events: The airport security checkpoint | Passengers and Employees |

| Kirschenbaum (2015) | The social foundations of airport security | Employees |

| Ghelfi-Waechter et al. (2019) | Towards unpredictability in airport security | Employees |

| Theme 4: Airport Technology | ||

| Sasse (2002) | Red-Eye Blink, Bendy Shuffle, and the Yuck Factor | Passengers |

| Castillo-Manzano and López-Valpuesta (2013) | Check-in services and passenger behaviour: Self service technologies in airport systems | Passengers |

| Inversini (2017) | Managing passengers' experience through mobile moments | Passengers |

| Rossi et al. (2018) | How to drive passenger airport experience: A decision support system based on user profile | Passengers |

| Theme 5: Delays | ||

| Wales et al. (2002) | Ethnography, Customers, and Negotiated Interactions at the Airport | Passengers and Employees |

| Baranishyn et al. (2010) | Customer service in the face of flight delays | Passengers |

| Theme 6: Shopping Motivations | ||

| Crawford (2003) | The importance of impulse purchasing behaviour in the international airport environment | Passengers |

| Lin and Chen (2013) | Passengers' shopping motivations and commercial activities at airports - The moderating effects of time pressure and impulse buying tendency | Passengers |

| Theme 7: Stress/Anxiety | ||

| McIntosh et al. (1998) | Anxiety and health problems related to air travel | Passengers |

| Bricker, 2005 | Development and evaluation of the air travel stress scale | Passengers |

| Bogicevic et al. (2016) | Traveler anxiety and enjoyment: The effect of airport environment on traveler's emotions | Passengers |

| Theme 8: Airport Access | ||

| Humphreys and Ison (2005) | Changing airport employee travel behaviour: The role of airport surface access strategies | Employees |

| Ison et al. (2007) | UK airport employee car parking: The role of a charge? | Employees |

| Budd (2016) | An exploratory examination of additional ground access trips generated by airport ‘meeter-greeters’ | Meeter-greeters |

References

- ACI . Airport Council International; 2020. Airport Service Quality (ASQ)https://aci.aero/customer-experience-asq/ [Google Scholar]

- Ali R. Skift; 2020. What Shape Would the Travel Industry Recovery Look like?https://skift.com/2020/04/12/what-shape-would-the-travel-industry-recovery-look-like/ [Google Scholar]

- Baranishyn M., Cudmore B.A., Fletcher T. Customer service in the face of flight delays. J. Vacat. Mark. 2010;16(3):201–215. [Google Scholar]

- Başar G., Bhat C. A parameterized consideration set model for airport choice: an application to the San Francisco Bay Area. Transp. Res. Part B Methodol. 2004;38(10):889–904. [Google Scholar]

- Bezerra G. C.L., Gomes C.F. The effects of service quality dimensions and passenger characteristics on passenger’s overall satisfaction with an airport. J. Air Transport. Manag. 2015;44-45:77–81. [Google Scholar]

- Bitner M.J. Servicescapes: the impact of physical surroundings on customers and employees. J. Market. 1992;56:57–71. [Google Scholar]

- Blackstone E.A., Buck A.J., Hakim S. Determinants of airport choice in a multi-airport region. Atl. Econ. J. 2006;34(3):313–326. [Google Scholar]

- Bogicevic V., Yang W., Cobanoglu C., Bilgihan A., Bujisic M. Traveler anxiety and enjoyment: The effect of airport environment on traveler’s emotions. J. Air Transport. Manag. 2016;57:122–129. [Google Scholar]

- Bricker Jonathan B. Development and evaluation of the Air Travel Stress Scale. J. Counsel. Psychol. 2005;52(4):615–628. [Google Scholar]

- Budd T. An exploratory examination of additional ground access trips generated by airport 'meeter-greeters. J. Air Transport. Manag. 2016;53:242–251. [Google Scholar]

- Castillo-Manzano J.I., López-Valpuesta L. Check-in services and passenger behaviour: self service technologies in airport systems. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2013;29(6):2431–2437. [Google Scholar]

- Causon J. Blue sky’ approach to customer service. Airports Int. 2011 https://airportsinternational.keypublishing.com/2011/06/16/blue-sky-approach-to-customer-service/ [Google Scholar]

- Chang H.L., Yang C.H. Do airline self-service check-in kiosks meet the needs of passengers? Tourism Manag. 2008;29(5):980–993. [Google Scholar]

- Chang Y.C., Chen C.F. Meeting the needs of disabled air passengers: factors that facilitate help from airlines and airports. Tourism Manag. 2012;33(3):529–536. [Google Scholar]

- Chen H.L. Benchmarking and quality improvement: a quality benchmarking deployment approach. Int. J. Qual. Reliab. Manag. 2002;19(6):757–773. [Google Scholar]

- Coll D. ACI Insights; 2020. COVID-19: Leveraging Airport Employee Experience in Period of Health Crisis.https://blog.aci.aero/covid-19-leveraging-airport-employee-experience-in-period-of-health-crisis/ [Google Scholar]

- Coutu P. Let us advocate a more meaningful, customer-centric approach. J. Airpt. Manag. 2013;7(1):4–7. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford G. The importance of impulse purchasing behaviour in the international airport environment. J. Consumer Behav. 2003;3(1):85–98. [Google Scholar]

- Crotts J.C., Erdmann R. Does national culture influence consumers’ evaluation of travel services? A test of Hofstede’s model of cross‐cultural differences. Manag. Serv. Qual. An. Int. J. 2000;10(6):410–419. [Google Scholar]

- Curley A.D., Alex, Krishnan Vik, Riedel Robin, Saxon Steve. McKinsey & Company; 2020. Coronavirus: Airlines Brace for Severe Turbulence. [Google Scholar]

- de Luca S. Modelling airport choice behaviour for direct flights, connecting flights and different travel plans. J. Transport Geogr. 2012;22:148–163. [Google Scholar]

- de Neufville R. Designing airport passenger buildings for the 21 St century. Proc. Inst. Civil Eng. Transport. 1995;111(2):97–104. [Google Scholar]

- De Neufville R. Low-cost airports for low-cost airlines: flexible design to manage the risks. Transport. Plann. Technol. 2008;31(1):35–68. [Google Scholar]

- De Neufville R., Scholtes S. MIT Press; Cambridge, Mass: 2011. Flexibility in Engineering Design. [Google Scholar]

- Desmet P., Hekkert P. Framework of product experience. Int. J. Des. 2007;1(1):57–66. [Google Scholar]

- Diebner R.S., Elizabeth, Ungerman Kelly, Vancauwenberghe Maxence. McKinsey & Company; 2020. Adapting Customer Experience in the Time of Coronavirus. [Google Scholar]

- Eber A. CNA; 2020. Changi Airport’s T4 to Be Closed from May 16, Second Terminal Shut in a Month.https://www.todayonline.com/singapore/changi-airports-t4-be-closed-may-16-second-terminal-shut-month [Google Scholar]

- Edwards B. Spon Press; London ; New York: 2005. The Modern Airport Terminal : New Approaches to Airport Architecture. [Google Scholar]

- Fodness D., Murray B. Passengers' expectations of airport service quality. J. Serv. Market. 2007;21(7):492–506. [Google Scholar]

- Fuhr J., Beckers T. Contract design, financing arrangements and public ownership-an assessment of the US airport governance model. Transport Rev. 2009;29(4):459–478. [Google Scholar]

- Gani M.G., Dewanti D., Irawan M.Z., Bastarianto F.F. Determining priority service of yogyakarta adisutjipto airport using servqual method and kano model. J. Civil Eng. Forum. 2019;5(3):211. 211. [Google Scholar]

- Ghelfi-Waechter S.M., Bearth A.F., Sophie C., Hofer F. Towards unpredictability in airport security. J. Airpt. Manag. 2019;13(2):110–121. [Google Scholar]

- Gkritza K., Niemeier D., Mannering F. Airport security screening and changing passenger satisfaction: an exploratory assessment. J. Air Transport. Manag. 2006;12(5):213–219. [Google Scholar]

- Gourdin K. Bringing quality back to commercial air travel. Transport. J. 1988;27(3) [Google Scholar]

- Haase R.P., Pigosso D.C.A., McAloone T.C. Product/service-system origins and trajectories: a systematic literature review of PSS definitions and their characteristics. Procedia CIRP. 2017;64:157–162. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison A., Popovic V., Kraal B.J., Kleinschmidt T. Proceedings of the Design Research Society. 2012. Challenges in passenger terminal design : a conceptual model of passenger experience; pp. 344–356. July 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hihara K. An analysis of an airport-airline relationship under a risk sharing contract. Transport. Res. E Logist. Transport. Rev. 2012;48(5):978–992. [Google Scholar]

- Horonjeff R.M., Francis X., Sproule William J., Young Seth B. McGraw-Hill; New York: 2010. Planning and Design of Airports. [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys I., Ison S. Changing airport employee travel behaviour: the role of airport surface access strategies. Transport Pol. 2005;12(1):1–9. [Google Scholar]

- ICAO . ICAO Newsroom; 2018. Continued Passenger Traffic Growth and Robust Air Cargo Demand in 2017.https://www.icao.int/Newsroom/Pages/Continued-passenger-traffic-growth-and-robust-air-cargo-demand-in-2017.aspx#:~:text=Continued%20passenger%20traffic%20growth%20and%20robust%20air%20cargo%20demand%20in%202017,-Page%20Image&text=The%20number%20of%20departures%20rose,approximately%207.7%20trillion%20RPKs%20performed [Google Scholar]

- Inversini A. Managing passengers' experience through mobile moments. J. Air Transport. Manag. 2017;62:78–81. [Google Scholar]

- Ison S., Humphreys I., Rye T. UK airport employee car parking: the role of a charge? J. Air Transport. Manag. 2007;13(3):163–165. [Google Scholar]

- Ito H., Lee D. Assessing the impact of the September 11 terrorist attacks on U.S. airline demand. J. Econ. Bus. 2005;57(1):75–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jeconbus.2004.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H., Zhang Y. An assessment of passenger experience at Melbourne Airport. J. Air Transport. Manag. 2016;54:88–92. [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez E., Claro J., Sousa J.P.d. The airport business in a competitive environment. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014;111:947–954. [Google Scholar]

- Juster N., Feiffer J. Epstein & Carroll; distributed by Random House; New York: 1961. The Phantom Tollbooth. [Google Scholar]

- Kim E., Beckman S.L., Agogino A. Design roadmapping in an uncertain world: implementing a customer-experience-focused strategy. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2018;61(1):43–70. [Google Scholar]

- Kirschenbaum A.A. The social foundations of airport security. J. Air Transport. Manag. 2015;48:34–41. [Google Scholar]

- Knox H., O'Doherty D., Vurdubakis T., Westrup C. Enacting airports: space, movement and modes of ordering. Organization. 2008;15(6):869–888. [Google Scholar]

- Kurniawan R., Sebhatu S.P., Davoudi S. Passengers’ perspective toward Airport Service Quality (ASQ) (Case Study at Soekarno-Hatta International Airport) J. Civ. Eng. Forum. 2017;3(1) [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann C. Springer Gabler; Wiesbaden: 2019. Exploring Service Productivity: Studies in the German Airport Industry. [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y.H., Chen C.F. Passengers' shopping motivations and commercial activities at airports - the moderating effects of time pressure and impulse buying tendency. Tourism Manag. 2013;36:426–434. [Google Scholar]

- Magalhães L., Reis V., Macário R. A new methodological framework for evaluating flexible options at airport passenger terminals. Case Stud. Trans. Pol. 2020;8(1):76–84. [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh Ian B., Swanson Vivien, Power Kevin G., Fiona Raeside, Craig Dempster. Anxiety and health problems related to air travel. J. Trav. Med. 1998;5(4):198–204. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8305.1998.tb00507.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millar C.C.J.M., Groth O., Mahon J.F. Management innovation in a VUCA world: challenges and recommendations. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2018;61(1):5–14. [Google Scholar]

- Müller P., Blessing L. Proceedings of ICED 2007, the 16th International Conference on Engineering Design DS. vol. 42. 2007. Development of product-service-systems - comparison of product and service development process models; pp. 1–12. August. [Google Scholar]

- Müller P., Kebir N., Stark R., Blessing L. 2009. PSS Layer Method - Application to Microenergy systems." Introduction to Product/Service-System Design; pp. 3–30. [Google Scholar]

- North C.S., Pollio D.E., Hong B.A., Surís A.M., Westerhaus E.T., Kienstra D.M., Smith R.P., Pfefferbaum B. Experience of the september 11 terrorist attacks by airline flight staff. J. Loss Trauma. 2013;18(4):322–341. [Google Scholar]

- Notis K. Bureau of Transportation Statistics; 2005. Airline Travel Since 9/11.https://www.bts.gov/archive/publications/special_reports_and_issue_briefs/issue_briefs/number_13/entire# [Google Scholar]

- O'Doherty D.P. Palgrave Macmillan; London: 2017. Reconstructing Organization: the Loungification of Society. [Google Scholar]

- Odoni A.R., de Neufville R. Passenger terminal design. Transport. Res. Part A. 1992;26(1):27–35. [Google Scholar]

- Oxley D. 2016. Estimating the Impact of Recent Terrorist Attacks in Western Europe Chart 2-A Longer-Term Perspective Icelandic Ashcloud; p. 2. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Parasuraman A. Service productivity, quality and innovation: implications for service-design practice and research. Int. J. Qual. Serv. Sci. 2010;2(3):277–286. [Google Scholar]

- Parasuraman A., Zeithaml V.A., Berry L.L. A conceptual model of service quality and its implications for future research. J. Market. 1985;49(4):41. 41. [Google Scholar]

- Pine B.J., Gilmore J.H. Harvard Business School Press; Boston: 1999. The Experience Economy : Work Is Theatre & Every Business a Stage. [Google Scholar]

- Pine B.J., Gilmore J.H. Handbook on the Experience Economy. 2013. The experience economy: past, present and future; pp. 21–44. [Google Scholar]

- Pohlmeyer A., Hecht M., Blessing L. Der Mensch im Mittepunkt; 2009. User Experience Lifecycle Model ContinUE [Continuous User Experience] pp. 314–317. [Google Scholar]

- Popovic V., Kraal B., Kirk P. Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Design and Emotion; Chicago , Illinois: 2010. Towards airport passenger experience models; pp. 1–11.https://eprints.qut.edu.au/38095/ [Google Scholar]

- Pütz O. From non-places to non-events: the airport security checkpoint. J. Contemp. Ethnogr. 2012;41(2):154–188. [Google Scholar]

- Rhoades D.L., Young S. Developing a quality index for US airports. Meas. Business Excellence. 2001;5(1):11–20. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi R., Gastaldi M., Orsini F. How to drive passenger airport experience: a decision support system based on user profile. IET Intell. Transp. Syst. 2018;12(4):301–308. [Google Scholar]

- Rothkopf M., Wald A. Innovation in commoditized services: a study in the passenger airline industry. Int. J. Innovat. Manag. 2011;15(4):731–753. [Google Scholar]

- Sasse M.A. Red-eye blink, bendy shuffle, and the yuck factor. IEEE Secur. Privacy. 2002;5(3):78–81. [Google Scholar]

- Shostack G.L. How to design a service. Eur. J. Market. 1982;16(1):49–63. [Google Scholar]

- Smit S., Martin H., Buehler Kevin, Lund Susan, Greenberg Ezra, Govindarajan Arvind. McKinsey & Company; 2020. Safeguarding Our Lives and Our Livelihoods: the Imperative of Our Time.https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/strategy-and-corporate-finance/our-insights/safeguarding-our-lives-and-our-livelihoods-the-imperative-of-our-time [Google Scholar]

- Smith C. Barron’s; 2020. Airline Demand during the Coronavirus Outbreak Looks a Lot like it Did after the 9/11 Attacks. Here’s Why.https://www.barrons.com/articles/airline-demand-coronavirus-outbreak-911-attacks-51583960866 [Google Scholar]

- Smollen P., Gallard J., Pontivivo G., Evans M., Roach M. 2003. Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) and Boarder Protection: A Report of the Sydney Airport Experience; pp. 120–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sykes W., Desai P. Department for Transport; London, UK: 2009. Understanding Airport Passenger Experience. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor C. CNBC; 2020. Coronavirus Impact on Airlines ‘has a 9/11 Feel,’ Analyst Says.https://www.cnbc.com/2020/03/06/coronavirus-impact-on-airlines-has-a-911-feel-analyst-says.html [Google Scholar]

- Toh W.W. Straits Times; 2020. Operations at Changi Airport T2 to Be Suspended for 18 Months from May.https://www.straitstimes.com/politics/operations-at-changi-airport-t2-to-be-suspended-for-18-months-amid-coronavirus-outbreak [Google Scholar]

- Trew M. PhocusWire; 2020. There Are No Winners in All This, Only Survivors, Say Investors.https://www.phocuswire.com/webintravel-wit-virtual-investors-advice-coronavirus [Google Scholar]

- Tsai W.H., Hsu W., Chou W.C. A gap analysis model for improving airport service quality. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excel. 2011;22(10):1025–1040. [Google Scholar]

- Unnikrishnan M. Delta CEO; Skift: 2020. Don’t Count on Airlines to Fully Recover for 3 Years.https://skift.com/2020/04/22/dont-count-on-airlines-to-fully-recover-for-3-years-delta-ceo/ [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Zwan F., Santema S., Curran R., Chou S.-Y., Trappey A., Pokojski J., Smith S. Springer; London: 2009. Creating Value by Measuring Collaboration Alignment of Strategic Business Processes; pp. 825–832. [Google Scholar]

- Wales R., O'Neill J., Mirmalek Z. Ethnography, customers, and negotiated interactions at the airport. IEEE Intell. Syst. 2002;17(5):15–23. [Google Scholar]

- Wales R., O’Neill J., Mirmalek Z. Ethnography, customers, and negotiated interactions at the airport. IEEE Intell. Syst. 2002;17(5):15–23. [Google Scholar]

- Waltersdorfer G., Gericke K., Blessing L. vol. 1. Smart Innovation, Systems and Technologies; 2015. pp. 341–351. ("ICoRD’15 – Research into Design across Boundaries Volume 1." ICoRD’15 – Research into Design across Boundaries). 34: [Google Scholar]

- Wattanacharoensil W., Schuckert M., Graham A. An airport experience framework from a tourism perspective. Transport Rev. 2016;36(3):318–340. [Google Scholar]

- Wiltshire J. Airport competition: reality or myth? J. Air Transport. Manag. 2018;67:241–248. [Google Scholar]

- Wiredja D., Popovic V., Blackler A. A passenger-centred model in assessing airport service performance. J. Model. Manag. 2019;14(2):492–520. [Google Scholar]

- Woolley-Meza O., Grady D., Thiemann C., Bagrow J.P., Brockmann D. Eyjafjallajökull and 9/11: the impact of large-scale disasters on worldwide mobility. PloS One. 2013;8(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J.-S., Park J.-W., Choi Y.-J. Passengers’ Expectations of Airport Service Quality: A Case Study of Jeju International Airport. 7th ed. 05. Int. J. Bus. Soc. Res. 2015 https://thejournalofbusiness.org/index.php/site/article/view/797/538 [Google Scholar]

- Yeh C.H., Kuo Y.L. Evaluating passenger services of Asia-Pacific international airports. Transport. Res. E Logist. Transport. Rev. 2003;39(1):35–48. [Google Scholar]

- Zografos K.G., Madas M.A. Development and demonstration of an integrated decision support system for airport performance analysis. Transport. Res. C Emerg. Technol. 2006;14(1):1–17. [Google Scholar]