Abstract

In this article, we investigate the binding processes of a fragment of the coronavirus spike protein receptor binding domain (RBD), the hexapeptide YKYRYL on the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor, and its inhibitory effect on the binding and activation of the coronavirus-2 spike protein CoV-2 RBD at ACE2. In agreement with an experimental study, we find a high affinity of the hexapeptide to the binding interface between CoV-2 RBD and ACE2, which we investigate using 20 independent equilibrium molecular dynamics (MD) simulations over a total of 1 μs and a 200-ns enhanced correlation guided MD simulation. We then evaluate the effect of the hexapeptide on the assembly process of the CoV-2 RBD to ACE2 in long-time enhanced correlation guided MD simulations. In that set of simulations, we find that CoV-2 RBD does not bind to ACE2 with the binding motif shown in experiments, but it rotates because of an electrostatic repulsion and forms a hydrophobic interface with ACE2. Surprisingly, we observe that the hexapeptide binds to CoV-2 RBD, which has the effect that this protein only weakly attaches to ACE2 so that the activation of CoV-2 RBD might be inhibited in this case. Our results indicate that the hexapeptide might be a possible treatment option that prevents the viral activation through the inhibition of the interaction between ACE2 and CoV-2 RBD.

Significance

A novel coronavirus, CoV-19, and a later phenotype, CoV-2, were identified as the primary cause for a severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS CoV-2). The spike (S) protein of CoV-2 is one target for the development of a vaccine to prevent the viral entry into human cells. The inhibition of the direct interaction between angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 and the S-protein could provide a suitable strategy to prevent the membrane fusion of CoV-2 and the viral entry into target cells. Using molecular dynamics simulations, we investigate the assembly process of a coronavirus spike protein fragment, the hexapeptide YKYRYL on the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 receptor, and its inhibitory effect on the aggregation and activation of the CoV-2 spike receptor protein at the same receptor protein.

Introduction

In December 2019, a novel respiratory disease appeared in Wuhan, Hubei, China. Although it is still under debate, there are strong indications that a first cluster of infections occurred at the Huanan seafood market (1, 2, 3). A novel coronavirus, CoV-19, and a later phenotype, CoV-2, were identified as the primary cause for a severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) (4,5). Within a few days, the viral disease spread over all of China, and within the following weeks, the local epidemic grew to a global pandemic with an exponentially growing infection rate. At present, the number of infected humans reached 3,855,788 with a number of 265,862 deaths associated with SARS CoV-19 and CoV-2 (6). This global pandemic will have an unprecedented economic, sociological, and political impact, in contrast to prior outbreaks of CoV-related SARS epidemics (7). Although a huge number of trials are still ongoing to develop a successful vaccination strategy against CoV-2, a direct medication of infected patients can have the potential to save lives and to stabilize the situation. The spike (S) protein of CoV-2 is the major target for the development of a vaccine or a potential strategy to tackle the viral entry into human cells (8, 9, 10). The S-protein forms trimers at the protrusions of the virus and comprises two functional subunits: S1 and S2. In the cascade of the viral entry, the S1 unit of the spike (S) protein facilitates the attachment of the virus at the surface of the cell (11). The S2 subunit, responsible for membrane fusion, employs TMPRSS2 for the S-protein priming, whereas it uses angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) as an entry receptor for membrane fusion (12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17). One of the key factors for its infectious potential for humans is the high conservation of ACE2 in different mammalian organisms (18), which allows its transmission from animals to humans. The receptor binding domain (RBD) of the S1 subunit contains five antiparallel β-strands, whereas α-helical and loop motifs form the connecting entities between the β-sheets. Between two β-sheets, an extended insertion forms the receptor binding motif, which binds to ACE2 at its N-terminal helix (19, 20, 21). Among a large number of potential targets, the inhibition of the direct interaction between ACE2 and the S-protein (SARS CoV-S) provides a suitable strategy to prevent the membrane fusion of CoV-2 and the viral entry into human cells (22,23). In a combined experimental and theoretical study, a hexapeptide ((438)YKYRYL (443)) of the receptor domain of SARS CoV S has been identified as an efficient inhibitor of the interaction between the S-protein and ACE2 (24). In vitro infection of Vero E6 cells by SARS coronavirus (SARS CoV) was blocked by the hexapeptide. It also has been shown that the peptide inhibits the proliferation of CoV-NL63. Interestingly, the fragment (438)YKYRYL (443) carries the dominant binding epitope and binds to ACE2 with a high affinity of KD = 46 μM. Its binding mode was further characterized by saturation transfer difference, NMR spectroscopy, and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. Based on this information, the peptide can be used as lead structure to design potential entry inhibitors against SARS CoV and related viruses.

In this article, we present MD simulations to investigate the effect of the hexapeptide on the binding of the spike protein RBD of SARS CoV-2 (CoV-2 RBD) with ACE2 and quantify its affinity to the binding site shown by Struck et al. (24). Second, we applied enhanced correlation guided MD (CORE-MD) simulations to measure the free energy of binding of the hexapeptide to its preferential binding site at ACE2. In the third stage of the study, we investigated the effect of the hexapeptide on the interaction of CoV-2 RBD with ACE2. In our simulations, we observe that the hexapeptide binds to the N-terminal region of ACE2 with a high affinity to three clusters that are located at the interface at which CoV-2 RBD binds to the receptor as revealed in x-ray structures (19,20). In the enhanced MD simulations, we observe that CoV-2 RBD relaxes into an energy minimum that differs fundamentally from the x-ray structure; we find that CoV-2 RBD rotates and binds to ACE2 at the N-terminal region by a hydrophobic patch, which is between residues Thr351 and Leu535. Our simulations reveal that the energetic minimum does not favor a hydrophilic interaction as shown in x-ray crystallography. In the simulations of binding of CoV-2 RBD to ACE2 in the presence of the hexapeptide, the hexapeptide binds preferentially to CoV-2 RBD in the vicinity to the ACE2 binding segment. Surprisingly, we find that the binding of the hexapeptide changes the assembly process of CoV-2 RBD such that the activation of ACE2 is inhibited by the hexapeptide. Our simulations are in agreement with the experimental study and demonstrate the potential of the hexapeptide YKYRYL as a possible “new modality” treatment option (25), which prevents the viral entry into human cells. Because of a damping effect by the cleavage of the peptide by proteases, a chemical modification that hinders that cellular process might increase the therapeutic potential of this peptide (25, 26, 27).

Methods

CORE-MD

CORE-MD uses the path along the reduced action Li as function of the momenta pi and coordinates qi for an atom with the index i (28, 29, 30, 31, 32):

| (1) |

where a finite time summation is applied over the path over momenta and displacements along the trajectory. For the calculation of the momentum pi = mivi, we use a uniform atomic mass. A path-dependent correlation function Ci(t) is calculated as follows:

| (2) |

where denotes the time average, and is determined at a time with a probability :

| (3) |

at each time step. To define a correlation-dependent probability density, the space of the correlation function is discretized into a histogram ranging from −1 to +1, and a probability density ρi(t) is defined at the time t for the history-dependent number of states and the total number of states in this state of the correlation function Ci(t):

| (4) |

That definition allows for the discretization of the path-dependent correlation and the definition of a log likelihood function (see below). The correlation-dependent density ρi(t) as a function of the correlation function Ci(t) for an atom with index i is then defined by:

| (5) |

where σ defines the width of the Gaussian function (because of the fact that we apply a histogram over 102 bins, we apply σ = 2 × 10−2). Subsequently, a log pseudolikelihood function l of the correlation-dependent density is defined, which describes a form of a correlation-dependent potential:

| (6) |

which leads to the corresponding bias Ai with an additional parameter α with the units of an energy:

| (7) |

as the derivative along a unit vector with a unit length because of the dimensionality of the correlation function. As a consequence, the bias gradient evolves as the gradient of the potential of the history-dependent probability density ρi(t), which is described by the log functional in Eq. 6. That way, the correlation-dependent likelihood is maximized in analogy to the principle of maximal entropy (33).

As a second element of the CORE-MD algorithm, a factorization of the total gradient by a factor ri is introduced. The application of the bias gradient using only the bias derived from the path-dependent correlation requires the sufficient sampling of the correlation space. The correlation space of the path correlation is sampled along a first-order rate equation:

| (8) |

where k1 stands for the first-order rate constant. To reach a sufficient sampling efficiency of the correlation space, the resulting gradient is scaled by a correlation-dependent factor r to enhance the decay of the autocorrelation and to achieve a faster access of the conformation space. As a consequence of the factorization, the time-dependent behavior of the correlation function is then described by a second-order rate equation:

| (9) |

We define the factor ri(t) as:

| (10) |

where β stands for a second dimensionless constant. In the global picture, the log likelihood function converges to the global log likelihood of the total correlation-dependent density :

| (11) |

where is approximated as the probability function Pi of the path-dependent correlation:

| (12) |

The last expression shows that the CORE-MD algorithm samples the global free energy in the infinite time limit because of the definition of ΔFi = −kBTlog(Pi).

Simulation parameters and system setup

For all simulations, we used the structures of the CoV-2 RBD-ACE2 complex from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) structure PDB: 6M0J (chain A: ACE2, chain E: CoV-2 RBD) (19). For the first set of 20 independent NPT-MD simulations over 50 ns in explicit solvent, we centered the PDB structure of ACE2 (PDB: 6M0J, chain A) in a triclinic box with dimensions 7.419 × 8.361 × 8.614 nm3 and filled the box with 17.026 SPC/E waters. For the preparation of 20 starting structures, we placed the hexapeptide YKYRYL at 20 different initial positions in the vicinity to the potential binding site of ACE2 (see Fig. 1 b). In parts, we reduced the accessible conformation space by the placement of the 20 peptide conformations in the vicinity of the CoV-2 RBD-ACE2 interface in the PDB structure. For the selection of random orientations, larger simulation times and a larger number of starting structures would have to be applied. For the enhanced sampling simulation of the hexapeptide-ACE2 system in implicit solvent using CORE-MD enhanced sampling, we modeled one hexapeptide-ACE2 conformation to and simulated the system over 200 ns using the parameters α = 5.0 and β = 0.5 (Table 1). For a third and a fourth CORE-MD enhanced sampling simulation with and without the presence of the hexapeptide, we modeled a separated CoV-2 RBD-ACE2 system with an increased contact distance of ∼2.2 nm by which the two domains are separated from each other. For the separated ACE2-CoV2 RBD complex with the hexapeptide, we inserted the hexapeptide 1 nm away from ACE2. Both systems were centered in a triclinic box with dimensions 7.41900 × 9.13930 × 16.23050 nm3 (see Fig. 1, c and d).

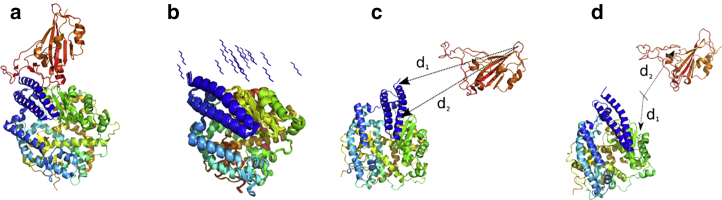

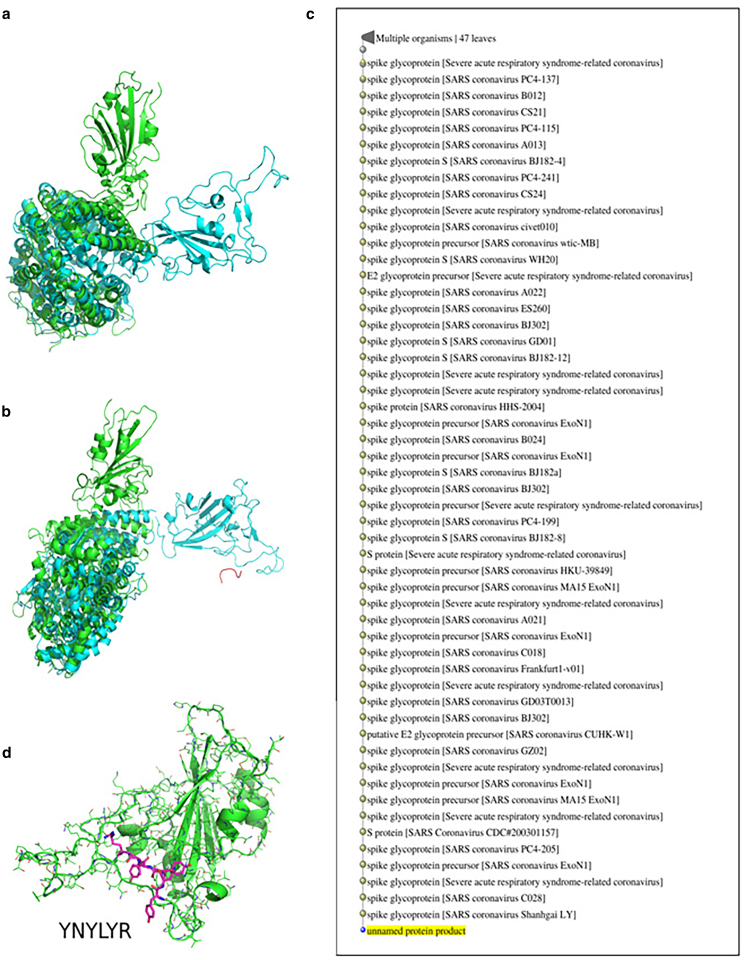

Figure 1.

(a) Crystal structure of the SARS CoV-2 spike protein CoV-2 RBD bound with ACE2 (PDB: 6M0J (19)). ACE2 is shown in blue, cyan, yellow, and green, and CoV-2 RBD is shown in orange. (b) 20 different hexapeptide (YKYRYL) conformations are used as initial starting models of independent 50-ns equilibrium MD simulations in explicit solvent. (c) Shown is the starting structure of the enhanced CORE-MD simulation of CoV-2 RBD to ACE2. (d) Shown is the starting structure of the enhanced CORE-MD simulation of the same system in the presence of the hexapeptide. The distances d1 and d2 used in the free energy projections (see Fig. 4) are indicated in (c) and (d). To see this figure in color, go online.

Table 1.

MD and CORE-MD enhanced sampling simulations that were performed in this study to investigate the effect of the hexapeptide on the binding process of CoV2-RBD with ACE2

| Simulation | Length | System |

|---|---|---|

| 20 independent simulations, NPT-MD | 50 ns | Hexapeptide-ACE2, explicit solvent (different starting positions) |

| 1 CORE-MD enhanced sampling | 200 ns | Hexapeptide-ACE2, implicit solvent |

| 1 CORE-MD enhanced sampling | 200 ns | CoV-2 RBD-ACE2, implicit solvent |

| 1 CORE-MD enhanced sampling | 200 ns | CoV-2 RBD-ACE2, hexapeptide, implicit solvent |

We used the AMBER99SB force field to describe the interactions (34). For the 20 independent MD simulations over a total of 1 μs, we used the stochastic velocity rescaling algorithm in combination with the Berendsen barostat to simulate the system at NPT conditions at 300 K and 1 bar using a time step of 1 fs (35). The enhanced sampling simulations of the hexapeptide-ACE2 complex and the separated CoV-2 RBD-ACE2 system with and without the hexapeptide have been performed in implicit solvent using the standard GBSA AMBER99SB parameters. We measured the affinity to a specific binding site using the number of counts N in which the hexapeptide resides below a contact threshold of the Cα atoms of 0.65 nm in relation to the total number of frames in the trajectory Nt. We define the relative affinity by the fraction of the affinity η divided by the maximal affinity ηmax measured for the specific system. The total affinity ɛ is given by the logarithm of the relative affinity:

| (13) |

We define the free energy ΔF by the probability P along two order parameters (i.e., the distances d1 and d2 between pairs of atoms):

| (14) |

where Pmin stands for the minimal probability by which the histogram is populated. We assessed the convergence of the 20 NPT-MD simulations and CORE-MD simulation of the hexapeptide-ACE2 system using the average root mean-square deviation of the individual distances dij and the final value:

| (15) |

over N distances. We used the GROMACS version 4.6 package for the equilibrium MD simulations and a modified GROMACS version 4.5.5 for the CORE-MD simulations (36). We identified the preferential binding site of the hexapeptide at ACE2 through a distance-based clustering. We then used the conformation of the hexapeptide at ACE2 for the calculation of protein interaction energies using the PRODIGY program (37). We modeled the individual hexapeptide conformers using the PyMOL modeling program (38).

Results and Discussion

Simulations of hexapeptide binding to ACE2

We tested the affinity of the hexapeptide to the ACE2 protein in 20 independent equilibrium MD simulations over a total simulation time of 50 ns. For this first set of simulations, we modeled 20 different starting conformations of the hexapeptide at an approximate distance of 1 nm away from the potential binding site between ACE2 and CoV-2 RBD. To examine the specific affinity of the hexapeptide for binding sites at ACE2, we determined the complete Cα-Cα distance matrix and averaged over all 20 trajectories. We find that the hexapeptide binds with 55% of the total affinity to the interface between the N-terminal helix and a β-sheet located at Glu329 and a lowered contact propensity of 43–50% to the residues Asn330 and Trp328 (see region (4) in Fig. 2, a and c). We observe another contact cluster at Asp382 and Met383, in which the affinity reaches values of 13 and 15%. A third contact cluster is located at Thr55, in which the affinity of the hexapeptide to ACE2 reaches a value of 21% (see Fig. 2, a and c).

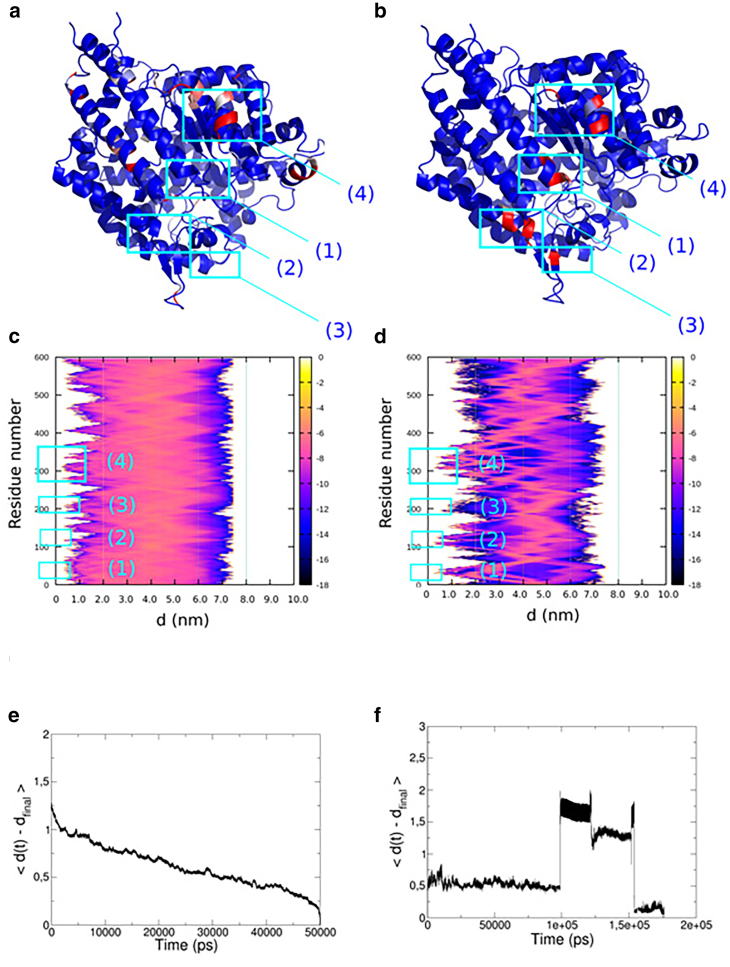

Figure 2.

(a and b) Result from 20 equilibrium MD simulations over 50 ns of the hexapeptide in the vicinity of ACE2. (a) Color-assigned structure of ACE2 with the affinity of the hexapeptide for regions at ACE2 was indexed with a color gradient ranging from 0 (blue) to 100% (red), corresponding to the highest affinity. (c) Shown is the log plot of the relative affinity ɛ averaged over the set of 20 MD simulations. The affinity expresses the propensity of finding the hexapeptide as a function of the residue number and the distance. (b and d) Shown is the result from the enhanced CORE-MD simulation over 200 ns of the hexapeptide in the vicinity of ACE2. (b) B-factor assigned structure of ACE2 with the affinity of the hexapeptide for regions at ACE2 was indexed with a color gradient ranging from 0 (blue) to 100% (red). (d) Shown is a log plot of the relative affinity ɛ of finding the hexapeptide as a function of the residue number and the distance averaged over the CORE-MD simulation. (e) Shown is the average root mean-square deviation of all measured distances (nm) of the hexapeptide and ACE2 as a function of time taken from the set of 20 independent NPT simulations. (f) Shown is the average root mean-square deviation of all pairwise distances (nm) in the CORE-MD simulation as a function of time. To see this figure in color, go online.

In an enhanced MD simulation, we simulated the binding of the hexapeptide to ACE2 in implicit solvent. We used this simulation to cross-validate our equilibrium MD simulations. In the enhanced MD simulation over 200 ns, we observe approximately identical binding patterns of the hexapeptide to the surface of ACE2. We observe a first cluster of contacts at Gly354 with an affinity of 27%. We find that a second contact cluster with a propensity ranging from 80 to 100% is located at Trp328 and Glu329 (see region (4) in Fig. 2, b and d). We observe another contact pattern at Gln325 with a propensity of 96%. A fourth contact cluster is located at Leu132 with a relative propensity equal to 56%. Finally, we observe a last cluster of contacts at the N-terminus of ACE2 between the residues Ser124 and Gly130 with affinities ranging from 1 to 71% (see regions (2) and (3) in Fig. 2, b and d). An additional minor contact formation with a propensity of 2% resides at Glu57 (see region (1) in Fig. 2, b and d). To assess the convergence of the simulations, we measured the average root mean-square deviation of the distances from their final value (see Fig. 2, e and f). In the set of 20 NPT-MD simulations, we observe that the average root mean-square deviation decreases to a value below 0.5 nm at ∼30 ns, which shows that the simulation length of 50 ns is sufficient for a convergent sampling (see Fig. 2 e). The CORE-MD simulation over 200 ns in implicit solvent shows that the hexapeptide accesses five different states (see Fig. 2 f).

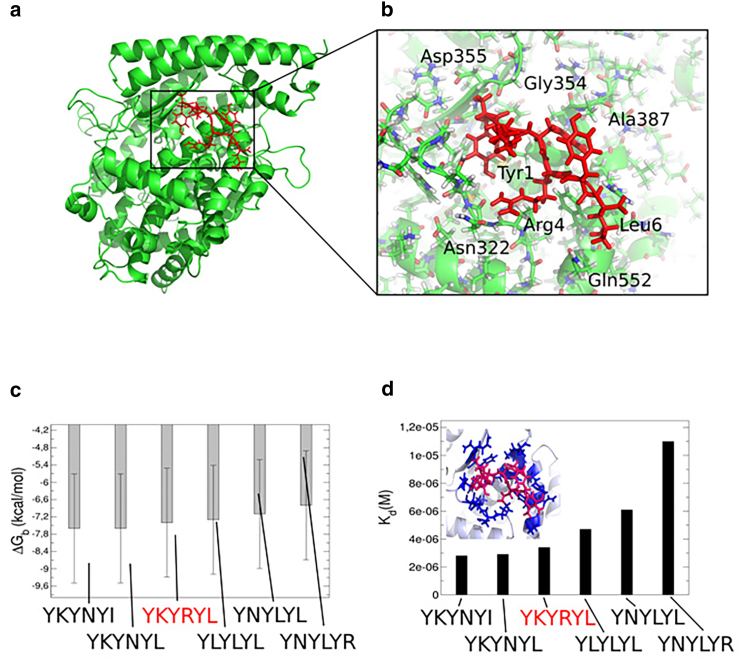

Our set of 20 equilibrium MD simulations agrees with the enhanced MD simulation on the general contact patterns of the hexapeptide at ACE2. In both sets of simulations, we find a major binding pattern in the vicinity of the N-terminal region of ACE2, where specifically Arg4 binds to Asn322, which is in agreement with the experimental study (24). The residues Tyr3 and Tyr5 are interacting with Ala387 in a hydrophobic binding mode (see Fig. 3, a and b). We conclude that the hexapeptide binds preferentially to the N-terminal helix and the helical interface close to the N-terminus, which indeed blocks the binding interface between CoV-2 RBD and ACE2 (19,20). Based on our findings, the hexapeptide shows a high affinity for the ACE2 binding region, which has the potential to inhibit CoV-2 RBD activation, membrane fusion, and the viral entry into the human cell (24). Subsequently, we used the conformation of the hexapeptide at ACE2 to model five further peptide variants and used a protein binding energy predictor (37) to determine the interaction strength of the models with ACE2 (see Fig. 3, c and d). We find that the hexapeptide YKYRYL binds with −7.4 kcal/mol and Kd = 3.4 × 10−6 M. A modification of the C-terminal residue to arginine and a hydrophobic modification at the position 4 to Leu leads to a lower interaction energy as we find for the models YNYLYL and YNYLYR (ΔG = −6.8 and −7.1 kcal/mol). A mutation at the position two to Leu has only a moderate effect and leads to an interaction energy equal to −7.3 kcal/mol. In contrast to the other variants, we found that Lys at position two should remain conserved, whereas a replacement of Arg at the position 4 with Asn increases the affinity of the hexapeptide to energies equal to −7.6 kcal/mol. The conformation with the lowest dissociation constant Kd is the variant YKYNYI, in which the C-terminal Ile stabilizes the interaction, leading to a value of Kd = 2.8 × 10−6 M. Finally, we state that the hexapeptide variants YKYNYI and YKYNYL contain potential alternative sequences for the binding to ACE2 and the inhibition of CoV-2 RBD activation.

Figure 3.

(a) Main conformation of the hexapeptide in complex with the N-terminal helical interface of ACE2 as revealed from equilibrium MD and enhanced sampling MD simulations. (b) Shown is the molecular view on the binding site of the hexapeptide at the interface with ACE2. (c) Shown are results from protein binding energy calculations ΔG (37) on the hexapeptide YKYRYL and five further variant models in the binding site at ACE2. The relative error to the experiment lies at 1.89 kcal/mol (37), as indicated by the error bars. (d) Shown is the dissociation constant from the protein binding energy calculations on the six peptide variants. To see this figure in color, go online.

Simulations of CoV-2 RBD ACE2 assembly formation

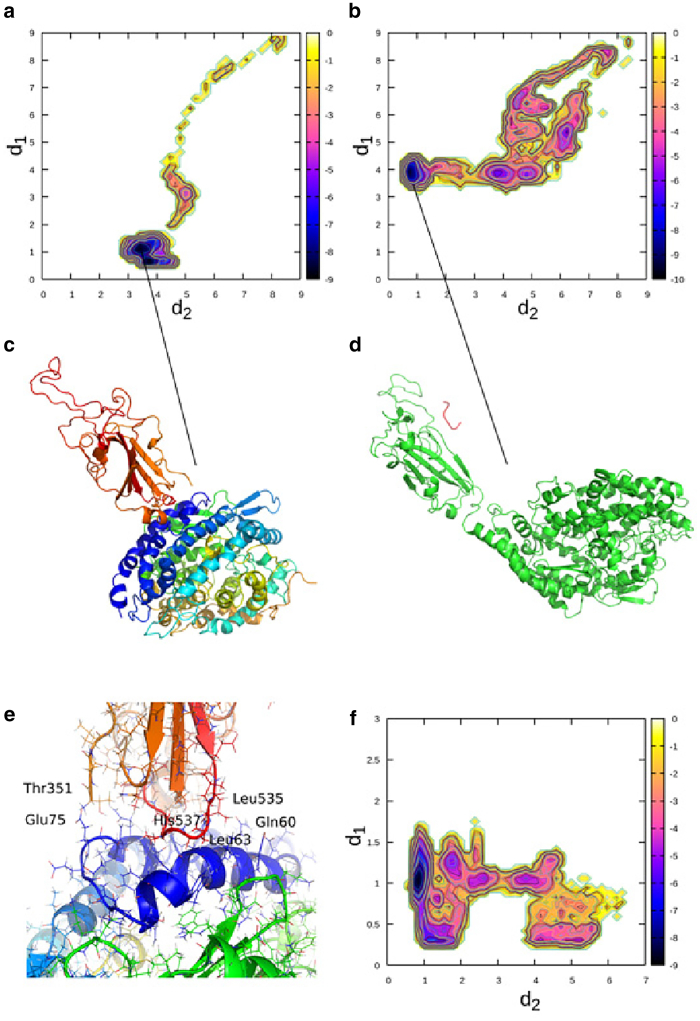

We tested the effect of the hexapeptide on the binding process of CoV-2 RBD on ACE2 (see Figs. 4 and 5). Therefore, we used a starting structure in which CoV-2 RBD is separated by a distance of 2.2 nm away from the surface of ACE2 (see Fig. 1, c and d). We simulated the system in and without the presence of the hexapeptide using CORE-MD enhanced sampling. In the simulation of binding of CoV-2 RBD to ACE2, the hydrophilic interface formed by the loop region between the β-sheets of CoV-2 RBD rotates away from the surface of ACE2, mainly because of an electrostatic repulsion. In a comparatively fast translatory process, CoV-2 RBD binds to the N-terminal helix (blue) of ACE2 (see Fig. 4, a and c). The interface between CoV-2 RBD and ACE2 is mainly stabilized by hydrophobic interactions between residues in the range between Leu535 and Thr351 (CoV-2 RBD) and Gln60 to Glu75. A hydrophobic interaction between Leu63 and His537 plays a major role in the stabilization of CoV-2 RBD at ACE2 (see Fig. 4 e). The relaxed final conformation of CoV-2 RBD at ACE2 is rotated by ∼90° in its attached orientation when we compare the structure in an overlay with the experimental x-ray structure (PDB: 6M0J (19)) (see Fig. 5 a). Additionally, the global contact pattern changed from a hydrophilic interface to a hydrophobic interaction at a different region of CoV-2 RBD, which is initialized by a rotatory motion in the beginning of the simulation that is induced by an electrostatic driving force.

Figure 4.

Results from enhanced sampling MD simulations of the binding process of CoV-2 RBD with ACE2 with and without the presence of the hexapeptide. (a) Free energy landscape is averaged over the trajectory of the CoV-2 RBD-ACE2 complex without the hexapeptide as function of the order parameters d1 and d2, given by the distances between the residues Ile21 CB (ACE2)-Val524 CB (CoV-2 RBD) (d1) and Ala65 CB (ACE2)-Leu390 CB (CoV-2 RBD) (d2). (b) Free energy landscape is averaged over the trajectory of CoV-2 RBD-ACE2 system in the presence of the hexapeptide as a function of the order parameters d1 and d2, given by the distances between the residues Ile21 CB (ACE2)-Val524 CB (CoV-2 RBD) (d1) and Ala65 CB (ACE2)-Leu390 CB (CoV-2 RBD) (d2) (see Fig. 1c, where the distances d1 and d2 are depicted). (c) Shown is the final converged state of CoV-2 RBD in complex with the N-terminus of ACE2 in the simulation without the hexapeptide. (d) Shown is the final converged state of CoV-2 RBD in the presence of the hexapeptide. (e) Shown is a molecular view of the interface of CoV-2 RBD at ACE2. (f) Shown is the free energy landscape as function of the order parameters d1 and d2, given by the distances between the residues Lys2 NZ (hexapeptide)-Glu465 OE1 (CoV-2 RBD) (d1) and Lys2 NZ (hexapeptide)-Lys335 (ACE2) (d2). The units in the color bar are given in kBT (see Fig. 1d, where the distances d1 and d2 are depicted). To see this figure in color, go online.

Figure 5.

Structural overlays of the PDB structure (PDB: 6M0J) of CoV-2 RBD in complex with ACE2 (green) and the two final structures from the enhanced MD simulations without (a) and in the presence of the hexapeptide (b) (cyan). (c) Shown is a list of SARS CoV viruses as a result from a Basic Local Alignment Search Tool search over the protein sequence space of all organisms. Surprisingly, the hexapeptide fragment preferentially occurs in SARS CoV viruses, which makes it suitable as a potential drug because of its dissimilarity with human proteins. (d) Shown is a hexapeptide fragment YNYLYR in SARS CoV-2 RBD (PDB: 6M0J, chain E), indicating that the tyrosine repeat at the positions 1, 3, and 5 might be important for the design strategy of a potential peptide mimetic for the treatment of SARS CoV-2 infections. To see this figure in color, go online.

In the simulation of CoV-2 RBD binding to ACE2 in the presence of the hexapeptide, we observe a fast binding process of the hexapeptide to CoV-2 RBD at Glu465 (CoV-2 RBD) and Lys2 (hexapeptide). We find a secondary contact between the hexapeptide and CoV-2 RBD between Ser349 (CoV-2 RBD) and Arg4 (hexapeptide) in the initial stage of the simulation. The hexapeptide then diffuses along the surface of CoV-2 RBD until it binds strongly to Glu465 (see Fig. 4, d and f). An initial rotatory process of CoV-2 RBD is highly analogous to the simulation without the hexapeptide, in which the binding motif of CoV-2 RBD rotates away from the surface of ACE2 because of an electrostatic driving force. In the implicit solvent environment, the formation of the contact interface is driven by the surface charge of CoV-2 RBD and ACE2. Therefore, the formation of a contact interface between polar residues as shown in the PDB structure is less probable. This behavior can potentially change at high salt concentrations. In contrast to the simulation without the hexapeptide, we find that CoV-2 RBD attaches only weakly at the peripheral region of the N-terminal helix 4 nm away from the conformation without the hexapeptide (see Figs. 4, b and d and 5 b). In this case, we again emphasize that the hexapeptide changes the electrostatic patterns, leading to a change in the structure of the assembly. The hexapeptide binds to CoV-2 RBD, leading to the weak attachment of CoV-2 RBD to ACE2. We anticipate that this conformation corresponds to an inhibited state, in which CoV-2 RBD does not become activated, and the process of membrane fusion might get inhibited because of the low affinity of CoV-2 RBD for ACE2. Because of thermal fluctuations and longer timescales, CoV-2 RBD might dissociate away from ACE2, which would inhibit CoV-2 activation.

We were surprised by the high specificity with which the hexapeptide bound to ACE2 and CoV-2 RBD. Because we observed that the hexapeptide inhibits the binding process of CoV-2 RBD, we performed a BLAST search over all organisms that contain the specific fragment in their protein sequences (39,40). Surprisingly, we found that 47 out of 50 hits in the sequence search returned SARS CoV organisms, whereas only three hits were contained in bacteria, which shows that the hexapeptide pattern preferentially occurs for SARS CoV but not in human proteins (see Fig. 5 c). That result shows that an a priori affinity for another function in the human organism can be excluded, which makes the hexapeptide a suitable candidate as a potential drug. When we analyzed the sequence of CoV-2 RBD, we find a hexapeptide sequence YNYLYR, which contains the same Tyr repeat at the positions 1, 3, and 5 but different residues at the positions 2, 4, and 6, which might be an indicator that Tyr at the positions 1, 3, and 5 is imminent for the specificity of CoV-2 RBD (see Fig. 5 d). However, we found that this hexapeptide sequence leads to the lowest interaction energy ΔG = −6.8 kcal/mol as we found in a modeling approach using the preferential hexapeptide ACE2 binding site as a structural model (see Fig. 3, c and d). We only can speculate that the amino acids at the positions 2, 4, and 6 are affecting the relative affinity of the fragment for the ACE2 receptor, whereas we find that Tyr at the positions 1, 3, and 5 is essential for the binding. We assume that Tyr at the positions 1, 3, and 5 has to be conserved for the design of a peptide mimetic used as a potential drug against SARS CoV-2, whereas the hexapeptide sequence YKYRYL inhibits the viral interaction with ACE2, as we have shown in this work. Finally, we conclude that binding of CoV-2 RBD to ACE2 is unexpectedly highly heterogeneous, which is also the case for the interaction of the hexapeptide with ACE2. We anticipate that the CoV-2 RBD-ACE2 interaction (as well as the hexapeptide-ACE2 complex) depends on the ionic strength. At high ionic strengths, a polar CoV-2 RBD-ACE2 binding interface as given in the experimental structure might be stabilized in a strong field of surrounding ions and water (19,41).

Conclusions

In this article, we investigated the binding process of a fragment of the SARS CoV spike protein receptor domain (CoV RBD), the hexapeptide YKYRYL on the ACE2 receptor, and its effect on the assembly formation and activation of CoV-2 RBD at ACE2. In agreement with an experimental study, we find a high affinity of the hexapeptide to the binding interface between CoV-2 RBD and ACE2, which we investigated using 20 independent equilibrium MD simulations over a total of 1 μs and a 200-ns enhanced MD simulation. We then evaluated the effect of the hexapeptide on the binding process of CoV-2 RBD to ACE2 in long-time enhanced MD simulations. In that set of simulations, we found that CoV-2 RBD does not bind to ACE2 with the binding motif shown in experiments, but it rotates because of an electrostatic repulsion and forms a hydrophobic interface with ACE2. Surprisingly, we observed that the hexapeptide binds to CoV-2 RBD, which has the effect that this protein only weakly attaches to ACE2 so that the activation of CoV-2 RBD might be inhibited in this case. Our results indicate that the hexapeptide might be a possible treatment option that prevents the viral activation through the inhibition of the interaction between ACE2 and CoV-2 RBD.

Editor: Margaret Cheung.

References

- 1.Zhou P., Yang X.-L., Shi Z.-L. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;579:270–273. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhu N., Zhang D., Tan W., China Novel Coronavirus Investigating and Research Team A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang C., Wang Y., Cao B. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coronaviridae Study Group of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses The species severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus: classifying 2019-nCoV and naming it SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Microbiol. 2020;5:536–544. doi: 10.1038/s41564-020-0695-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chan J.F., Yuan S., Yuen K.Y. A familial cluster of pneumonia associated with the 2019 novel coronavirus indicating person-to-person transmission: a study of a family cluster. Lancet. 2020;395:514–523. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30154-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization. May 9 . 2020. Coronavirusdisease (COVID-19) Situation Report–110.www.who.int [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Wit E., van Doremalen N., Munster V.J. SARS and MERS: recent insights into emerging coronaviruses. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2016;14:523–534. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2016.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Du L., He Y., Jiang S. The spike protein of SARS-CoV--a target for vaccine and therapeutic development. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2009;7:226–236. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gierer S., Bertram S., Pöhlmann S. The spike protein of the emerging betacoronavirus EMC uses a novel coronavirus receptor for entry, can be activated by TMPRSS2, and is targeted by neutralizing antibodies. J. Virol. 2013;87:5502–5511. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00128-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xia S., Liu M., Lu L. Inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 (previously 2019-nCoV) infection by a highly potent pan-coronavirus fusion inhibitor targeting its spike protein that harbors a high capacity to mediate membrane fusion. Cell Res. 2020;30:343–355. doi: 10.1038/s41422-020-0305-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Walls A.C., Park Y.-J., Veesler D. Structure, function, and antigenicity of the SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein. Cell. 2020;181:281–292.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li W., Moore M.J., Farzan M. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 is a functional receptor for the SARS coronavirus. Nature. 2003;426:450–454. doi: 10.1038/nature02145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heurich A., Hofmann-Winkler H., Pöhlmann S. TMPRSS2 and ADAM17 cleave ACE2 differentially and only proteolysis by TMPRSS2 augments entry driven by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus spike protein. J. Virol. 2014;88:1293–1307. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02202-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoffmann M., Kleine-Weber H., Pöhlmann S. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell. 2020;181:271–280.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ge X.Y., Li J.L., Shi Z.L. Isolation and characterization of a bat SARS-like coronavirus that uses the ACE2 receptor. Nature. 2013;503:535–538. doi: 10.1038/nature12711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Glowacka I., Bertram S., Pölmann S. Evidence that TMPRSS2 activates the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus spike protein for membrane fusion and reduces viral control by the humoral immune response. J. Virol. 2011;85:4122–4134. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02232-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuba K., Imai Y., Penninger J.M. A crucial role of angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) in SARS coronavirus-induced lung injury. Nat. Med. 2005;11:875–879. doi: 10.1038/nm1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holmes K.V. Structural biology. Adaptation of SARS coronavirus to humans. Science. 2005;309:1822–1823. doi: 10.1126/science.1118817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lan J., Ge J., Wang X. Structure of the SARS-CoV-2 spike receptor-binding domain bound to the ACE2 receptor. Nature. 2020;581:215–220. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2180-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li F., Li W., Harrison S.C. Structure of SARS coronavirus spike receptor-binding domain complexed with receptor. Science. 2005;309:1864–1868. doi: 10.1126/science.1116480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brielle E.S., Schneidmann-Duhovny D., Linial M. The SARS-CoV-2 exerts a distinctive strategy for interacting with the ACE2 human receptor. Viruses. 2020;12:497. doi: 10.3390/v12050497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kilianski A., Baker S.C. Cell-based antiviral screening against coronaviruses: developing virus-specific and broad-spectrum inhibitors. Antiviral Res. 2014;101:105–112. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2013.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adedeji A.O., Sarafianos S.G. Antiviral drugs specific for coronaviruses in preclinical development. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2014;8:45–53. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2014.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Struck A.-W., Axmann M., Meyer B. A hexapeptide of the receptor-binding domain of SARS corona virus spike protein blocks viral entry into host cells via the human receptor ACE2. Antiviral Res. 2012;94:288–296. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2011.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Valeur E., Guéret S.M., Plowright A.T. New modalities for challenging targets in drug discovery. Angew. Chem. Int.Engl. 2017;56:10294–10323. doi: 10.1002/anie.201611914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Axmann, M. 2007. Protein-ligand-wechselwirkungen im wirkstoffdesign: ligandbindung an membranständige proteine in lebenden zellen und die identifizierung einer leitstruktur als entry-inhibitor der SARS-CoV infektion. PhD thesis (University of Hamburg).

- 27.Srivastava V., editor. Peptide Therapeutics: Drug Discovery. The Royal Society of Chemistry; London, UK: 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kleinert H. World Scientific; Singapore: 2009. Path Integrals in Quantum Mechanics, Statistics, Polymer Physics, and Financial Markets, Fifth Edition. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Feynman R., Hibbs A.R., Styer D.F. Emended Edition; Courier Corporation: 2010. Quantum mechanics and path integrals. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peter E.K., Shea J.-E. An adaptive bias - hybrid MD/kMC algorithm for protein folding and aggregation. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017;19:17373–17382. doi: 10.1039/c7cp03035e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peter E.K. Adaptive enhanced sampling with a path-variable for the simulation of protein folding and aggregation. J. Chem. Phys. 2017;147:214902. doi: 10.1063/1.5000930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peter E.K., Černý J. A hybrid Hamiltonian for the accelerated sampling along experimental restraints. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20:370. doi: 10.3390/ijms20020370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mead L.R., Papanicolaou N. Maximum entropy in the problem of moments. J. Math. Phys. 1984;25:2404. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hornak V., Abel R., Simmerling C. Comparison of multiple Amber force fields and development of improved protein backbone parameters. Proteins. 2006;65:712–725. doi: 10.1002/prot.21123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bussi G., Donadio D., Parrinello M. Canonical sampling through velocity rescaling. J. Chem. Phys. 2007;126:014101. doi: 10.1063/1.2408420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hess B., Kutzner C., Lindahl E. GROMACS 4: algorithms for highly efficient, load-balanced, and scalable molecular simulation. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2008;4:435–447. doi: 10.1021/ct700301q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vangone A., Bonvin A.M.J.J. Contacts-based prediction of binding affinity in protein–protein complexes. eLife. 2015;4:e074054. doi: 10.7554/eLife.07454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schrödinger L.L.C. 2015. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 1.8. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Altschul S.F., Gish W., Lipman D.J. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gish W., States D.J. Identification of protein coding regions by database similarity search. Nat. Genet. 1993;3:266–272. doi: 10.1038/ng0393-266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kastritis P.L., Bonvin A.M.J.J. On the binding affinity of macromolecular interactions: daring to ask why proteins interact. J. R. Soc. Interface. 2012;10:20120835. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2012.0835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]