Abstract

In the last decade, immunotherapies have revolutionised anticancer treatment. However, there is still a number of patients that do not respond or acquire resistance to these treatments. Despite several efforts to combine immunotherapy with other strategies like chemotherapy, or other immunotherapy, there is an ‘urgent’ need to better understand the immune landscape of the tumour microenvironment. New promising approaches, in addition to blocking co-inhibitory pathways, such those cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 and programmed cell death protein 1 mediated, consist of activating co-stimulatory pathways to enhance antitumour immune responses. Among several new targets, glucocorticoid-induced TNFR-related gene (GITR) activation can promote effector T-cell function and inhibit regulatory T-cell (Treg) function. Preclinical data on GITR-agonist monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) demonstrated antitumour activity in vitro and in vivo enhancing CD8+ and CD4+ effector T-cell activity and depleting tumour-infiltrating Tregs. Phase I clinical trials reported a manageable safety profile of GITR mAbs. However, monotherapy seems not to be effective, whereas responses have been reported in combination therapy, in particular adding PD-1 blockade. Several clinical studies are ongoing and results are awaited to further develop GITR-stimulating treatments.

Keywords: GITR, immunotherapy, cancer

Introduction

In the last decade, immunotherapies, mainly through antiprogrammed cell death protein 1 (anti-PD-1)/programmed death-ligand 1 and anticytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (anti-CTLA-4) monoclonal antibodies (mAbs), have revolutionised anticancer treatment. However, there is still a number of patients that do not respond or acquire resistance to these treatments. According to recent tumour classification by their immune infiltration, some types of cancer potentially respond to immune checkpoint inhibitors (highly immune-infiltrated or ‘hot tumour’), while in other tumours available immunotherapies appear not to be effective (non-immune-infiltrated or ‘cold tumour’). Despite several efforts to combine immunotherapy with other strategies like chemotherapy, radiotherapy or other immunotherapy aiming to convert ‘cold’ to ‘hot’ tumour, there is an ‘urgent’ need to better understand the immune landscape of the tumour microenvironment and to find alternative approaches to modulate immune function.1

New promising approaches, in addition to blocking co-inhibitory pathways, such those CTLA-4 and PD-1 mediated, consist of activating co-stimulatory pathways to enhance antitumour immune responses.2 One such strategy includes the development of agonist antibodies to target members of the tumour necrosis factor receptor superfamily (TNFRSF) with key role on immune activation and antitumour immune response, like 4-1BB, OX40, CD27 and glucocorticoid-induced TNFR-related gene (GITR).3 Several data demonstrate that GITR activation can promote effector T-cells function and inhibit regulatory T-cells (Treg) function.3 4

In this review, we focus on the GITR/GITR ligand (GITRL) axis.

Biological background

GITR and GITRL expression

GITR (TNFRSF18/CD357/AITR) is a type 1 transmembrane protein belonging to the TNFRSF including OX40, CD27, CD40 and 4-1BB. Human GITR is constitutively expressed at high level on CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ Tregs and at low levels on naïve and memory T-cells.4–7 On activation of CD8+ and CD4+ effector T-cells, GITR expression increases rapidly on both Tregs and effector T-cells, reaching the highest level on activated Tregs.4 5

GITR is also expressed on natural killer (NK) cells and at low levels on B cells, macrophages and dendritic cells, and can be upregulated by activation, especially on NK.8 9

GITRL is a type 2 transmembrane protein and is also a member of the TNFRSF. It is commonly identified as a trimer, although it can also be present as a monomer or assemble into others multimeric forms.10

GITRL is predominantly expressed by activated antigen-presenting cells, including macrophages, B cells, dendritic cells and endothelial cells.4 8 Notably, GITR and GITRL expression is not restricted to haematopoietic cells. GITR expression has been described on epidermal keratinocytes and osteoclast precursors and GITRL expression on endothelial cells, especially after type I interferon (IFN) exposure.6

Recently, another GITR endogenous ligand has been described: SECTM1A, which is expressed both as a transmembrane protein and as a secreted protein. In mouse, SECTM1A is able to activate both GITR and CD7, but its role is not yet defined.11

GITR signalling and function

GITR, as other molecules of the TNFRSF, can act as a co-stimulatory receptor, thus representing a potential target to enhance immunotherapy, in particular immune checkpoint inhibitors.

All TNFR are characterised by their ability to bind TNF ligand and activate the transcription nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) pathways via TNF receptor-associated factors (TRAFs), a family of six proteins that are recruited to further transduce signals within the cell. In particular, the activation of GITR signalling pathways, mediated by TRAF2/5-NF-κB, results in reduced T-cell apoptosis and promotes T-cell survival, at least in part by upregulating the expression of the Bcl-xL prosurvival molecule.12

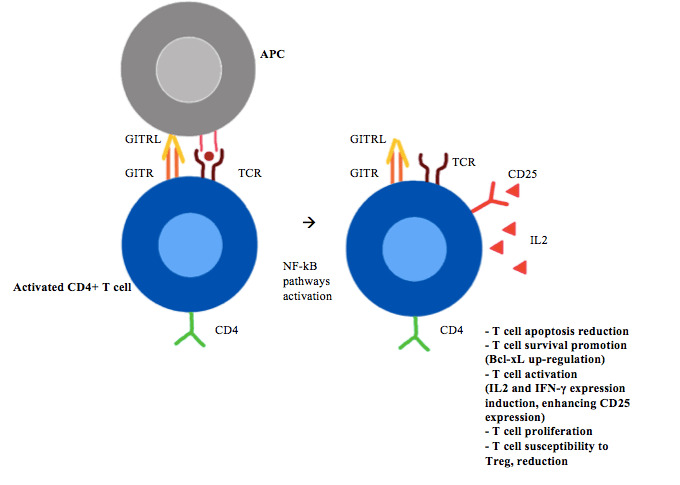

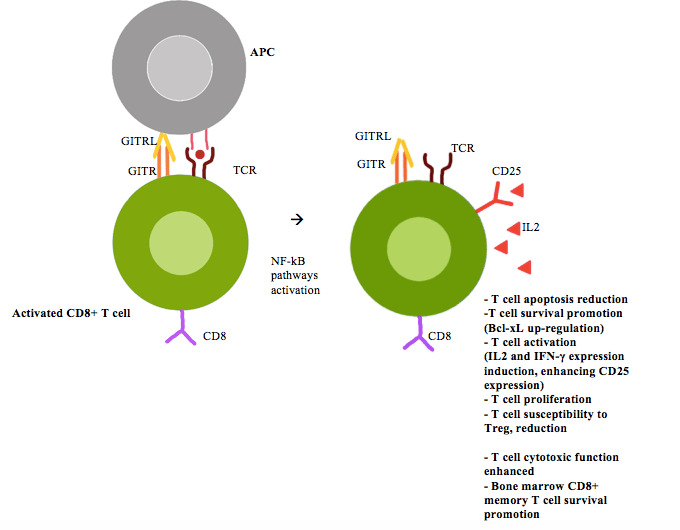

In the periphery, after T-cell receptor (TCR) stimulation, the GITRL or agonist antibodies on conventional T-cells increases T-cell activation by inducing interleukin (IL)-2 and IFN-γ expression, enhancing CD25 expression and stimulating cell proliferation (figure 1).12–14 Furthermore, GITR co-stimulation enhances CD8+ T-cell cytotoxic function, and promotes survival of bone marrow CD8+ memory T-cell (figure 2).15

Figure 1.

CD4+ T-cell GITR/GITRL activation. APCs, antigen-presenting cells; GITR, glucocorticoid-induced TNFR-related gene; GITRL, GITR ligand; IFN, interferon; IL, interleukin; NF-κB, nuclear factor-κB; TCR, T-cell receptor; Treg, regulatory T-cell.

Figure 2.

CD8+ T cell GITR/GITRL activation. APCs, antigen-presenting cells; GITR, glucocorticoid-induced TNFR-related gene; GITRL, GITR ligand; IFN, interferon; IL, interleukin; NF-κB, nuclear factor-κB; TCR, T-cell receptor; Treg, regulatory T-cell.

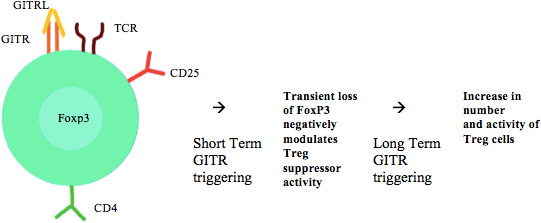

Although GITR is highly expressed in (CD4+CD25+FoxP3+) Treg cells, its function on these cells is more complex (figure 3).3

Figure 3.

Treg GITR/GITRL activation. GITR, glucocorticoid-induced TNFR-related gene; GITRL, GITR ligand; TCR, T-cell receptor; Treg, regulatory T-cell.

In vitro and in vivo, GITR signalling, especially mediated by agonist mAb, can inhibit Treg ability to suppress effector T-cells, either by rendering effector T-cells less susceptible to Treg immunosuppressive activities or by directly inhibiting Tregs.16 17 This last mechanism could be due to the transient loss of FoxP3 on Tregs, although it has been observed only in Tregs from tumour-bearing mice and not in Tregs from naïve mice.18

Interestingly, the GITR/GITRL axis effect on Treg seems to be inhibitory in the short-term, while the long-term over stimulation in vivo favours the expansion and the activity of Treg in mice.16

In addition, GITR co-triggering of conventional T-cells stimulates IL-10 production, favouring differentiation of conventional CD4+ T-cells into T-helper 2 and Treg cells, these findings sustain the role of GITR in the balancing between T-helper and Treg cells.19

Differently, the role of GITR in NK remains to be determined because of contradictory data as to whether GITR engagement increases8 or decreases NK cell activity.20

In summary, while commonly Treg cells antagonise effector T-cells, thereby limiting antitumour activity, GITR activation on effector T-cells increase effector function by limiting the sensitivity of these cells to Treg suppression.

Modulation of GITR in preclinical tumour models

Antitumour activity of GITR mAb

In recent years, GITR has been largely studied as a pharmacological target.

Co-activation of GITR by agonist mAbs can increase immune response, inflammation and thereby antitumour response.9 Differently, GITR inhibition, through antagonist mAbs could inhibit T-cell activation and immune response.6 Consequently, GITR agonist mAbs has been further developed as antitumour agents.

In tumour models, the antitumour activity of GITR mAbs is mainly based on the ability to enhance CD8+ and CD4+ effector T-cell activity and on the inhibition/depletion of tumour-infiltrating Tregs.21–24

Importantly, GITR is not expressed on the tumour itself, but it is expressed on tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) of several human cancer types including lung cancers, renal cell carcinoma, head and neck carcinoma and melanoma.25

The most widely used molecules to trigger GITR are agonist antibodies like DTA-1 (a rat IgG2b)5 or recombinant version of GITRL, like GITR-Fc.

The DTA-1 mAb has demonstrated in vivo antitumour activity in multiple syngeneic mouse tumour models (eg, melanoma,24 cervical26) enhancing CD8+ and CD4+ T-cell proliferation and cytokine induction. A recent study reported that GITR agonists can also increase cellular metabolism to support CD8+ T-cell effector function and proliferation.27

The intermediate role of CD8 + and CD4 + T-cells in tumour rejections seems to be crucial.

Regressing tumour-bearing mice, treated with DTA-1, were found infiltrated by a large number of CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells, including those secreting IFN-γ. However, the treatment resulted in tumour regression only in IFN-γ-intact mice but not IFN-γ-deficient mice.28 29 The effect of DTA-1 was lost/decreased in the absence of CD8+ T and NK cells.4

Moreover, GITR engagement by DTA-1 promoted the differentiation of IL-9-producing CD4+ T-helper cells, thus enhancing immune-mediated tumour response.30

The additional crucial concomitant mechanism to inhibit tumour growth, following DTA-1—GITR triggering is the reduction of Treg activity and number. Such a reduction can occur via Treg-specific and tumour-specific antibody-dependent cell cytotoxicity (ADCC): GITR+ Tregs specific for tumour antigens, through the Fc domain of anti-GITR mAbs, are recognised and killed by myeloid and NK cells present in the tumour.22 23

GITR has a higher expression in tumour infiltrating Treg compared with peritumoral region in several tumour like renal, colorectal and hepatocarcinoma.31–33

FoxP3+ Treg reduced accumulation in tumours has been also hypothesised as a result of reduced trafficking or loss of FoxP3 expression in intratumour Treg and their ‘conversion’ into activated T-cells.24

However, Mahne et al reported that mDTA-1 depletes rather than converts intratumour Tregs. In tumour-bearing mice, Treg depletion together with GITR triggering were necessary to revert intratumour CD8+ T-cell exhaustion, thus improving antitumour efficacy.34

Vence et al confirmed that tumours with high expression of CD8+ and CD4+, after GITR mAb treatment, have the better response, mainly lung cancer, renal cancer and melanoma.25

Moreover, preliminary results showed a better suppression of tumour growth with intratumour compared with intravenous injection. In fact, the intratumour injection was able to induce a systemic antitumour immune reaction, exerting its effect on injected and on un-injected tumours.35

Combination of GITR mAb with immune-modulating therapies

GITR, like other co-stimulating molecules, has a key role on T-cell activation and its activity can potentiate, in a synergic effect, other anticancer therapies.

Combined treatment with anti PD-1 and GITR-agonist mAbs was able to achieve long-term survival in mouse model of ovarian and breast cancer, stimulating IFN-γ producing conventional T-cells and inhibiting immunosuppressive Tregs and myeloid-derived suppressor cells.4 36 The treatment combination manages to rescue CD8+ T-cell dysfunction and to induce proliferation of precursor effector memory T-cell phenotype in a CD226-dependent manner.37 Durable responses were also reported adding cytotoxic chemotherapy or radiotherapy to anti-PD-1/GITR mAbs.36 38 39

Co-administration of GITR mAbs and anti-CTLA-4 resulted in an 80% tumour-response in CT26 (colon carcinoma) and CMS5a (fibrosarcoma) mice tumour models reducing intratumour Treg (via GITR) and stimulating CD8+ T-cells (via CTLA-4).37

Targeting GITR together with an OX40 agonist (OX40 ligand fusion protein), showed unexpectedly a synergistic antitumour effect on CT26 tumour-bearing mice, although the toxic profile of the combination could represent a limit to clinical development.40

The synergistic and complimentary antitumour effect obtained combining GITR mAbs and vaccines was reported13 in cervical cancer41 and in melanoma.42 Moreover, adding chemotherapy (gemcitabine) to the combination of vaccine and GITR mAb was able to decrease tumour-suppressive environment and to induce a long-lasting memory immune response.43

In conclusion, in preclinical tumour models co-activating GITR through agonist mAb was able to induce antitumour responses. In particular DTA-1 mAb demonstrated in vivo antitumour activity in multiple mouse tumour models, enhancing CD8+ and CD4+ T-cell proliferation/cytokine induction, and reducing Treg activity and number, especially via ADCC. Moreover, GITR agonist mAbs best antitumour responses were achieved in combination with other immune-modulating therapies.

Clinical trials with GITR monoclonal antibodies

MEDI1873, a GITR-ligand/IgG1 agonist fusion protein, was tested in a phase I trial reporting G3 treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs) in the 22.5% of patients and no G4-5 TRAEs (table 1). Pharmacodynamics analysis confirmed that MEDI1873 increased CD4+Ki67+ T-cells and induced a >25% decrease in GITR+/FoxP3+ T-cells in the evaluable patients. Stable disease (42.5%), durable in the 17.5% of patients, was the best response in this heavily pretreated population, supporting further clinical trials.44

Table 1.

Main characteristics of the agonist GITR mAb

| Compound | Phase | Treatment arm (no. of pts) | DLT, n | TRAEs any grade, n (%) |

TRAEs, any grade, in ≥5% pts | TRAEs G3-4, n (%) |

Serious TRAEs, n (%) |

Confirmed ORR, n (%) |

Confirmed DCR, n (%) |

| MEDI-187344 | I | Monotherapy (40) |

3 | 82.5%* | Headache, IRR† | G3: 22.5%* No G4-5 |

Not reported | 0 | 42.5%* |

| AMG-22845 | I | Monotherapy (30) | 0 | 18 (60%) | Fatigue (13%), IRR (7%), fever (7%), decreased appetite (7%), hypophosphataemia (7%) |

G3-4: 0 G5: 1 |

2 (7%) | 0 | 7 (23%) |

| BMS-98615646 | I–IIa | Monotherapy (34) |

0 | 20 (59%) | Fever (18%), nausea (15%), fatigue (12%), chills (9%), lipase increased (6%), arthralgia (6%), vomiting (6%), malaise (6%), IRR (6%), diarrhoea (6%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 (32%) |

| Combination therapy: BMS-986156+nivolumab (258) | 1‡ | 170 (66%) | Fatigue (15%), fever (11%), IRR (10%), nausea (8%), chills (8%), diarrhoea (6%), asthenia (5%), arthralgia (5%) | 24 (9.3%) | 7 (2.7%) | 21 (8%) | 105 (42%) | ||

| TRX-51847 | I | Monotherapy (43) | 0 | 16 (37%) | Fatigue (11.6%)† | Not reported | 0 | 0 | 4 (9%) |

| MK-416648 | I | Monotherapy (48) |

1 | Not reported | Fatigue, IRR, nausea, abdominal pain, pruritus† | 6 (5%) | Not reported | 4 (9%) | Not reported |

| Combination therapy: MK-4166+pembrolizumab (65)§ |

0 | 4/45 (9%)¶ 9/13 (69%)** |

Not reported |

*The number of pts is not reported.

†No other data available.

‡DLT occurred at the combination dose of BMS-986156 800 mg+nivolumab 240 mg.

§Of whom, 45 pts were in the dose escalation cohort and 20 pts were in an expansion cohort (treatment-naïve and pretreated melanoma).

¶ORR in the dose escalation cohort.

**ORR in the immune-checkpoint inhibitor-naïve pts with melanoma (13 pts).

DCR, disease control rate; DLT, dose-limiting toxicity; GITR, glucocorticoid-induced TNFR-related gene; IRR, infusion-related reaction; mAb, monoclonal antibody; ORR, overall response rate; pts, patients; TRAEs, treatment-related adverse events.

The phase I trial with AMG 228, an agonistic human IgG1 GITR-mAb, reported a favourable safety profile, but no evidence of T-cell activation or antitumour activity, at least as monotherapy.45

BMS-986156, a fully human IgG GITR-mAb, has been tested as monotherapy and in combination therapy with nivolumab in a phase I/IIa trial. None of the 34 patients in the monotherapy arm experienced a dose-limiting toxicity (DLT) or grade G3-5 TRAEs, a patient out of 258 had a DLT in combination with nivolumab 240 mg. No responses were seen with monotherapy, although an objective response rate (ORR) of 9% (18 out of 200 evaluable patients) across all tumour types was achieved in the combination arm.46

No responses were reported in the phase I trial with TRX518, a fully humanised Fc-dysfunctional aglycosylated IgG1κ GITR-mAb, in monotherapy. Pharmacodynamics data and subsequent in vitro and in vivo investigation highlighted the possible mechanisms of tumour resistance to anti-GITR monotherapy and its possible overcome combining anti PD-1/PD-L1 therapy. In a murine model, DTA-1 early treatment delayed tumour growth, preventing intratumour Treg accumulation and CD8+-not exhausted T-cell upregulation. Differently, in advanced tumours microenvironment, high Treg expression increases dysfunctional CD8+ T-cells that shows an exhausted profile and fail to upregulate markers of activation and cytotoxicity. Thus, adding PD-1 blockade was able to counteract CD8+ T-cells exhaustion, resulting in better tumour control.47 Preliminary evaluations of tumour response among the first patients enrolled in the phase I combinational trial were encouraging (NCT02628574).

MK-4166, a humanised IgG1 agonist GITR mAb, in combination with pembrolizumab, an anti PD-1 mAb, demonstrated a good safety profile and potential activity, in particular among patients with melanoma naïve to treatments.48

Others compounds under investigation (table 2) are ASP1951 (PTZ-522),49 a tetravalent monospecific (TM) anti-GITR agonist antibody (NCT03799003); INCAGN01876, a humanised IgG1 mAb (NCT03126110) and GWN323 (NCT02740270).

Table 2.

Ongoing clinical trials testing GITR-stimulating treatments

| ClinicalTrial.gov identifier | Tumour type | Setting (early or advanced disease, first, second or more lines if metastatic) | Phase | Treatment arms | Target accrual | Status (at submission date) |

|

NCT02437916: AMG228 |

Melanoma non-small cell Lung cancer squamous cell Carcinoma of the head and neck transitional cell Carinoma of bladder Colorectal cancer | Advanced tumour | I | AMG228 Part 1 and part 2 of the study will both be with single agent AMG228 in different selected tumour types |

30 | Terminated (business decision) |

|

NCT04225039: Anti-GITR Agonist INCAGN1876 |

Glioblastoma | Second line | II | A: INCAGN01876+INCMGA00012+rt stereotactic radiosurgery, not surgery B: INCAGN01876+INCMGA00012+rt stereotactic radiosurgery, followed by surgery |

32 | Not yet recruiting |

|

NCT03707457: Anti-GITR Monoclonal Antibody MK-4166 |

Glioblastoma | Second line | I | A: Nivolumab+anti-GITR monoclonal antibody MK-4166 B: Nivolumab+IDO1 inhibitor C: Nivolumab+ipilimumab |

30 | Recruiting |

|

NCT02132754: Anti-GITR Monoclonal Antibody MK-4166 |

Advanced malignancies | Second or more lines | I |

|

113 | Completed |

|

NCT04021043: Anti-GITR Agonistic Monoclonal Antibody BMS-986156 |

Advanced or metastatic Lung/chest or liver cancers | Advanced disease | I/II | I: Ipilimumab+BMS-986156+nivolumab II: Ipilimumab+BMS-986156+nivolumab+SBRT III: BMS-986156+nivolumab+SBRT |

60 | Recruiting |

|

NCT02598960: Anti-GITR Agonistic Monoclonal Antibody BMS-986156 |

Advanced solid tumours | Second or more lines | I/II |

|

331 | Active not recruiting |

|

NCT01239134: Anti-GITR mAb TRX518 |

Stage iii or Iv Malignant melanoma or other solid tumours | Second or more lines | I | Part A: a single ascending dose study of TRX518 Part B: a dose-escalation study of multidose TRX518 monotherapy Part C: an expansion cohort of multidose TRX518 monotherapy at the maximum tolerated dose |

10 | Completed |

|

NCT02628574: Anti-GITR mAb TRX518 |

Advanced solid tumours | Advanced disease | I |

|

146 | Active, not recruiting |

|

NCT03861403: Anti-GITR mAb TRX518 |

Advanced solid tumours | Second or more lines | Ib/IIa |

|

125 | Active, not recruiting |

|

NCT02740270: GWN323 (Anti-GITR) |

Advanced cancer or lymphomas | Advanced disease | I/Ib | A : Drug: GWN323 B: Drug: GWN323 Drug: PDR001 |

92 | Active, not recruiting |

|

NCT03295942: OMP-336B11 |

Locally advanced or metastatic solid tumours | Second or more lines | Ia | OMP-336B11 | 24 | Terminated (sponsor decision) |

|

NCT02583165: MEDI1873 |

Advanced solid tumours | Advanced disease | I | MEDI1873 | 40 | Completed |

|

NCT03799003: ASP1951 GITR Agonistic Antibody |

Advanced solid tumours | Second or more lines | Ib |

|

435 | Recruiting |

|

NCT02553499: MK-1248 |

Advanced solid tumour | Second or more lines | I |

|

37 | Terminated (enrolment prematurely discontinued due to programme prioritisation, not due to any safety concerns) |

|

NCT02697591: INCAGN01876 |

Advanced or metastatic solid tumours | Second or more lines | I/II | Initial cohort dose of INCAGN01876 monotherapy at the protocol-defined starting dose, with subsequent cohort escalations based on protocol-specific criteria | 100 | Active not recruiting |

|

NCT03277352: INCAGN01876 |

Advanced or metastatic malignancies | Second or more lines | I/II | INCAGN01876+pembrolizumab+epacadostat | 10 | Acrive not recruiting |

|

NCT03126110: INCAGN01876 |

Advanced or metastatic malignancies | Second or more lines | I/II |

|

285 | Recruiting |

GITR, glucocorticoid-induced TNFR-related gene.

Conclusions and future perspectives

GITR can act as a co-stimulatory receptor, representing a potential target to enhance immunotherapy efficacy. Preclinical data confirmed GITR triggering could increase CD8+ and CD4+ effector T-cell activity and reduce tumour-infiltrating Tregs. GITR mAbs have a manageable safety profile. However, they seem not to be effective as monotherapy, whether responses have been reported in phase I/II trials combination therapy with immune checkpoint inhibitors. In particular, adding PD-1 blockade may have a synergistic and complimentary antitumour effect, by converting CD8+ T-cells exhaustion.

Several clinical studies are ongoing, especially in combination with other treatments and results are awaited to further develop GITR-stimulating treatment.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors contributed on writing this review and provided critical feedback and final approval of the version to publish.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: LDM reports personal fees from Roche, personal fees from Pfizer, personal fees from Ipsen, personal fees from Eli Lilly, personal fees from Novartis, personal fees from Takeda, personal fees from MSD, personal fees from Genomic Health, personal fees from Celgene, personal fees from Seattle Genetics, outside the submitted work.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Galon J, Bruni D. Approaches to treat immune hot, altered and cold tumours with combination immunotherapies. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2019;18:197–218. 10.1038/s41573-018-0007-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Schaer DA, Hirschhorn-Cymerman D, Wolchok JD. Targeting tumor-necrosis factor receptor pathways for tumor immunotherapy. J Immunother Cancer 2014;2:7. 10.1186/2051-1426-2-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Knee DA, Hewes B, Brogdon JL. Rationale for anti-GITR cancer immunotherapy. Eur J Cancer 2016;67:1–10. 10.1016/j.ejca.2016.06.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Riccardi C, Ronchetti S, Nocentini G. Glucocorticoid-induced TNFR-related gene (GITR) as a therapeutic target for immunotherapy. Expert Opin Ther Targets 2018;22:783–97. 10.1080/14728222.2018.1512588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Shimizu J, Yamazaki S, Takahashi T, et al. Stimulation of CD25(+)CD4(+) regulatory T cells through GITR breaks immunological self-tolerance. Nat Immunol 2002;3:135–42. 10.1038/ni759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nocentini G, Riccardi C. GITR: a modulator of immune response and inflammation. Adv Exp Med Biol 2009;647:156–73. 10.1007/978-0-387-89520-8_11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. McHugh RS, Whitters MJ, Piccirillo CA, et al. CD4(+)CD25(+) immunoregulatory T cells: gene expression analysis reveals a functional role for the glucocorticoid-induced TNF receptor. Immunity 2002;16:311–23. 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00280-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hanabuchi S, Watanabe N, Wang Y-H, et al. Human plasmacytoid predendritic cells activate NK cells through glucocorticoid-induced tumor necrosis factor receptor-ligand (GITRL). Blood 2006;107:3617–23. 10.1182/blood-2005-08-3419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Clouthier DL, Watts TH. Cell-specific and context-dependent effects of GITR in cancer, autoimmunity, and infection. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 2014;25:91e106:91–106. 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2013.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zhou Z, Tone Y, Song X, et al. Structural basis for ligand-mediated mouse GITR activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008;105:641–5. 10.1073/pnas.0711206105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Howie D, Garcia Rueda H, Brown MH, et al. Secreted and transmembrane 1A is a novel co-stimulatory ligand. PLoS One 2013;8:e73610. 10.1371/journal.pone.0073610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Snell LM, McPherson AJ, Lin GHY, et al. Cd8 T cell-intrinsic GITR is required for T cell clonal expansion and mouse survival following severe influenza infection. J Immunol 2010;185:7223–34. 10.4049/jimmunol.1001912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cohen AD, Diab A, Perales M-A, et al. Agonist anti-GITR antibody enhances vaccine-induced CD8(+) T-cell responses and tumor immunity. Cancer Res 2006;66:4904–12. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nishikawa H, Kato T, Hirayama M, et al. Regulatory T cell-resistant CD8+ T cells induced by glucocorticoid-induced tumor necrosis factor receptor signaling. Cancer Res 2008;68:5948–54. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Snell LM, Lin GHY, Watts TH, et al. IL-15-dependent upregulation of GITR on CD8 memory phenotype T cells in the bone marrow relative to spleen and lymph node suggests the bone marrow as a site of superior bioavailability of IL-15. J Immunol 2012;188:5915–23. 10.4049/jimmunol.1103270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Petrillo MG, Ronchetti S, Ricci E, et al. GITR+ regulatory T cells in the treatment of autoimmune diseases. Autoimmun Rev 2015;14:117–26. 10.1016/j.autrev.2014.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Stephens GL, McHugh RS, Whitters MJ, et al. Engagement of glucocorticoid-induced TNFR family-related receptor on effector T cells by its ligand mediates resistance to suppression by CD4+CD25+ T cells. J Immunol 2004;173:5008–20. 10.4049/jimmunol.173.8.5008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Schaer DA, Budhu S, Liu C, et al. GITR pathway activation abrogates tumor immune suppression through loss of regulatory T cell lineage stability. Cancer Immunol Res 2013;1:320–31. 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-13-0086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Oja AE, Brasser G, Slot E, et al. GITR shapes humoral immunity by controlling the balance between follicular T helper cells and regulatory T follicular cells. Immunol Lett 2020;222:73–9. 10.1016/j.imlet.2020.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Baltz KM, Krusch M, Baessler T, et al. Neutralization of tumor-derived soluble glucocorticoid-induced TNFR-related protein ligand increases NK cell anti-tumor reactivity. Blood 2008;112:3735–43. 10.1182/blood-2008-03-143016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kim YH, Shin SM, Choi BK, et al. Authentic GITR signaling fails to induce tumor regression unless Foxp3+ regulatory T cells are depleted. J Immunol 2015;195:4721–9. 10.4049/jimmunol.1403076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Coe D, Begom S, Addey C, et al. Depletion of regulatory T cells by anti-GITR mAb as a novel mechanism for cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2010;59:1367–77. 10.1007/s00262-010-0866-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bulliard Y, Jolicoeur R, Windman M, et al. Activating Fc γ receptors contribute to the antitumor activities of immunoregulatory receptor-targeting antibodies. J Exp Med 2013;210:1685–93. 10.1084/jem.20130573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cohen AD, Schaer DA, Liu C, et al. Agonist anti-GITR monoclonal antibody induces melanoma tumor immunity in mice by altering regulatory T cell stability and intra-tumor accumulation. PLoS One 2010;5:e10436. 10.1371/journal.pone.0010436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Vence L, Bucktrout SL, Fernandez Curbelo I, et al. Characterization and comparison of GITR expression in solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res 2019;25:6501–10. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-0289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Loddenkemper C, Hoffmann C, Stanke J, et al. Regulatory (Foxp3+) T cells as target for immune therapy of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and cervical cancer. Cancer Sci 2009;100:1112–7. 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01153.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sabharwal SS, Rosen DB, Grein J, et al. GITR agonism enhances cellular metabolism to support CD8+ T-cell proliferation and effector cytokine production in a mouse tumor model. Cancer Immunol Res 2018;6:1199–211. 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-17-0632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ko K, Yamazaki S, Nakamura K, et al. Treatment of advanced tumors with agonistic anti-GITR mAb and its effects on tumor-infiltrating Foxp3+CD25+CD4+ regulatory T cells. J Exp Med 2012;209:423 10.1084/jem.200509402092c [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ramirez-Montagut T, Chow A, Hirschhorn-Cymerman D, et al. Glucocorticoid-induced TNF receptor family related gene activation overcomes tolerance/ignorance to melanoma differentiation antigens and enhances antitumor immunity. J Immunol 2006;176:6434–42. 10.4049/jimmunol.176.11.6434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kim I-K, Kim B-S, Koh C-H, et al. Glucocorticoid-induced tumor necrosis factor receptor–related protein co-stimulation facilitates tumor regression by inducing IL-9–producing helper T cells. Nat Med 2015;21:1010–7. 10.1038/nm.3922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Asma G, Amal G, Raja M, et al. Comparison of circulating and intratumoral regulatory T cells in patients with renal cell carcinoma. Tumour Biol 2015;36:3727–34. 10.1007/s13277-014-3012-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wu H, Chen P, Liao R, et al. Intratumoral regulatory T cells with higher prevalence and more suppressive activity in hepatocellular carcinoma patients. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013;28:1555–64. 10.1111/jgh.12202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pedroza-Gonzalez A, Verhoef C, Ijzermans JNM, et al. Activated tumor-infiltrating CD4+ regulatory T cells restrain antitumor immunity in patients with primary or metastatic liver cancer. Hepatology 2013;57:183–94. 10.1002/hep.26013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mahne AE, Mauze S, Joyce-Shaikh B, et al. Dual roles for regulatory T-cell depletion and costimulatory signaling in agonistic GITR targeting for tumor immunotherapy. Cancer Res 2017;77:1108–18. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-0797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Narumi K, Miyakawa R, Shibasaki C, et al. Local administration of GITR agonistic antibody induces a stronger antitumor immunity than systemic delivery. Sci Rep 2019;9:5562. 10.1038/s41598-019-41724-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lu L, Xu X, Zhang B, et al. Combined PD-1 blockade and GITR triggering induce a potent antitumor immunity in murine cancer models and synergizes with chemotherapeutic drugs. J Transl Med 2014;12:36. 10.1186/1479-5876-12-36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mitsui J, Nishikawa H, Muraoka D, et al. Two distinct mechanisms of augmented antitumor activity by modulation of immunostimulatory/inhibitory signals. Clin Cancer Res 2010;16:2781–91. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-3243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Schoenhals JE, Cushman TR, Barsoumian HB, et al. Anti-glucocorticoid-induced tumor necrosis factor-related protein (GITR) therapy overcomes radiation-induced Treg immunosuppression and drives Abscopal effects. Front Immunol 2018;9:2170. 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wang B, Zhang W, Jankovic V, et al. Combination cancer immunotherapy targeting PD-1 and GITR can rescue CD8+ T cell dysfunction and maintain memory phenotype. Sci Immunol 2018;3:eaat7061. 10.1126/sciimmunol.aat7061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Leyland R, Watkins A, Mulgrew KA, et al. A novel murine GITR ligand fusion protein induces antitumor activity as a monotherapy that is further enhanced in combination with an OX40 agonist. Clin Cancer Res 2017;23:3416–27. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hoffmann C, Stanke J, Kaufmann AM, et al. Combining T-cell vaccination and application of agonistic anti-GITR mAb (DTA-1) induces complete eradication of HPV oncogene expressing tumors in mice. J Immunother 2010;33:136–45. 10.1097/CJI.0b013e3181badc46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Avogadri F, Zappasodi R, Yang A, et al. Combination of alphavirus replicon particle-based vaccination with immunomodulatory antibodies: therapeutic activity in the B16 melanoma mouse model and immune correlates. Cancer Immunol Res 2014;2:448–58. 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-13-0220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ko H-J, Kim Y-J, Kim Y-S, HJ K, Kim YS, et al. A combination of chemoimmunotherapies can efficiently break self-tolerance and induce antitumor immunity in a tolerogenic murine tumor model. Cancer Res 2007;67:7477–86. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Denlinger CS, Infante JR, Aljumaily R, et al. A phase I study of MEDI1873, a novel GITR agonist, in advanced solid tumors. Ann Oncol 2018;29:viii411–41. 10.1093/annonc/mdy288.027 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Tran B, Carvajal RD, Marabelle A, et al. Dose escalation results from a first-in-human, phase 1 study of glucocorticoid-induced TNF receptor-related protein agonist AMG 228 in patients with advanced solid tumors. J Immunother Cancer 2018;6:93. 10.1186/s40425-018-0407-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Heinhuis KM, Carlino M, Joerger M, et al. Safety, tolerability, and potential clinical activity of a glucocorticoid-induced TNF receptor-related protein agonist alone or in combination with nivolumab for patients with advanced solid tumors: a phase 1/2A dose-escalation and cohort-expansion clinical trial. JAMA Oncol 2019;7:1–8. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.3848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Zappasodi R, Sirard C, Li Y, et al. Rational design of anti-GITR-based combination immunotherapy. Nat Med 2019;25:759–66. 10.1038/s41591-019-0420-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Papadopoulos KP, Autio KA, Golan T, et al. Phase 1 study of MK-4166, an anti-human glucocorticoid-induced tumor necrosis factor receptor (GITR) antibody, as monotherapy or with pembrolizumab (pembro) in patients (PTS) with advanced solid tumors. JCO 2019;37:9509 10.1200/JCO.2019.37.15_suppl.9509 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49. 33rd annual meeting & pre-conference programs of the society for immunotherapy of cancer (SITC 2018) : Washington, D.C., USA. 7-11 November 2018. J Immunother Cancer 2018;6:115. 10.1186/s40425-018-0423-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]