Abstract

Jeremy Safran and his research group suggest that rupture-repair processes are important for the therapeutic change in patients with personality disorders. In this exploratory study, we describe alliance ruptures and resolutions on a session-by-session basis in a clinical sample of adolescents with Borderline Personality Pathology (BPP). Three research questions are addressed: i) Is there a typical trajectory of alliance ruptures over treatment time? ii) Which rupture and resolution markers occur frequently? iii) Which rupture markers are most significant for the therapeutic alliance? Ten patients who presented with identity diffusion and at least three Borderline Personality Disorder criteria were studied and treated with Adolescent Identity Treatment. Alliance ruptures and resolutions were coded in 187 therapy sessions according to the Rupture Resolution Rating System. Mixed-effect models were used for statistical analyses. Findings supported an inverted U-shaped trajectory of alliance ruptures across treatment time. The inspection of individual trajectories displayed that alliance ruptures emerge non-linearly with particular significant alliance ruptures appearing in phases or single peak sessions. Withdrawal rupture markers emerged more often compared to confrontation markers. However, confrontation markers inflicted a higher impact or strain on the immediate collaboration between patient and therapist compared to withdrawal markers. Clinicians should expect alliance ruptures to occur frequently in the treatment of adolescents with BPP. The findings support the theory of a dynamic therapeutic alliance characterised by a continuous negotiation between patients and therapists.

Key words: Alliance ruptures, Alliance development, Process research, Borderline personality disorders, Adolescents

Introduction

As in adult psychotherapy (Horvath, Del Re, Flückiger, & Symonds, 2011; Martin, Garske, & Davis, 2000), the therapeutic alliance is a robust predictor of treatment outcome in child and adolescent psychotherapy consistent across different developmental levels and diverse treatment approaches (Shirk & Karver, 2003). Nevertheless, the underlying mechanisms of the effectiveness of the therapeutic alliance remain unclear (Castonguay, Constantino, & Holtforth, 2006; Doran, 2016). Jeremy Safran and his research group notably stimulated the second generation of alliance research that investigates the underlying mechanisms of the therapeutic alliance, beyond its predictive validity. With their research programme of alliance ruptures and repairs, they focus on the ongoing, dynamic quality of the therapeutic alliance over the process of change (Safran, 1993; Safran & Muran, 1996). This change in paradigm from outcome to process research has especially been favoured by the interest in patients with Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) who chronically suffer from difficulties in interpersonal relationships with others or with the therapist (Lingiardi & Colli, 2015). In this article, we study alliance ruptures and repairs over the complete treatment course in a sample of adolescences with both full-syndrome and subthreshold BPD. To designate this population, the term Borderline Personality Pathology (BPP) is used.

BPD is a complex psychiatric syndrome characterised by a pervasive pattern of instability of interpersonal relationships, identity, affect and impulsivity (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). These core diagnostic features are similar in adolescents compared to adults (Becker, Grilo, Edell, & McGlashan, 2002). Reliability and validity of the BPD diagnosis are comparable between (late) adolescence and adulthood (Chanen, Sharp, Hoffman, & the Global Alliance for Prevention and Early Intervention for Borderline Personality Disorder, 2017; Fonagy et al., 2015), and according to the upcoming International Classification of Disease, Eleventh Revision (ICD-11), BPD can be described best using a life-course perspective (WHO, 2018). BPD in adolescence is associated with clinically significant impairments in social and occupational functioning (Kaess, Brunner, & Chanen, 2014; Miller, Muehlenkamp, & Jacobson, 2008). Only recently, experts in the field declared adolescents with BPD as a sensible clinical population highly in need of early prevention and specific interventions (Chanen et al., 2017). While there is still no generally accepted developmental psychopathological model of BPD, most etiological theories are in favor of a transactional diathesis-stress model (Sharp & Fonagy, 2015) that include interactions between genetic vulnerability and childhood adversities (Ensink, Biberdzic, Normandin, & Clarkin, 2015).

One of the most central tasks in normal adolescent development is the consolidation of the identity (Erikson, 1959). Identity diffusion is a theoretical construct that describes identity disturbance as observed in BPD and is the lack of integration of the concept of self and significant others (Clarkin & Kernberg, 2006). Current analyses show that there is a general factor of personality pathology where identity diffusion has the highest loading on this factor (Sharp et al., 2015). A basic assumption in contemporary object relation’s theory is that early experiences with caregivers, particularly those with intense affect states, lead to the development of internalized mental representations of self and a mental representation of the other (Fonagy, Gergely, Jurist, & Target, 2002; Kernberg, 1984). The concept of ego identity originally formulated by Erikson (1982) included in its definition the integration of the concept of the self; an object relations approach expands this definition with the corresponding integration of the concepts of significant others. In contrast, when this developmental stage of normal identity integration is not reached, the earlier developmental stage of dissociation or splitting between a positive or idealized and a negative or persecutory segment of experience persists. Under these conditions, multiple, nonintegrated representations of self are split into idealized and persecutory dyads, and multiple representations of significant others are split along similar lines, jointly constituting the syndrome of identity diffusion.

The development of an optimistic and trusting therapeutic relationship is regarded as the general principle of treatment of BPD (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, NICE, 2009). The therapeutic alliance with BPD patients is challenged by their interpersonal difficulties associated with impulsivity, affective dysregulation, rejection sensitivity and hypermentalization (Fonagy et al., 2015). Thus, therapists report strong countertransference reactions of anger, confusion, and anxiety in response to unpredictable patient behaviours (McMain, Boritz, & Leybman, 2015). Along with the BPD psychopathology, the level of involvement, treatment motivation and resistance pose a further challenge in the treatment of adolescents (Karver, Handelsman, Fields, & Bickman, 2006). Adolescents are often brought to treatment by their parents or public authorities and feel ambivalent in their awareness of problems and their intrinsic treatment motivation (Foelsch et al., 2014).

The framework of alliance ruptures and repairs provides an empirical and theoretical foundation to understand ongoing threats and difficulties in the therapeutic alliance also with adolescents with BPD. Alliance ruptures are characterised as momentary deteriorations in the quality of the therapeutic alliance that results from a lack of collaboration on therapy goals, tasks and/or strains in the affective bond (Bordin, 1979; Eubanks-Carter, Muran, & Safran, 2015). Two types of alliance ruptures have been observed – withdrawal and confrontation ruptures. A withdrawal rupture is characterised either by a patient’s movement away from the therapist and/or the work of therapy (e.g. minimal response, avoidant storytelling, selfcriticism/ hopelessness) or a patient’s movement towards the therapist and/or work of therapy in a dishonest, appeasing manner. A confrontation rupture is characterised by a patient’s movement against the therapist and/or work of therapy (e.g. complaints/concerns about the therapist or progress in therapy, the therapist’s intervention, efforts to control/pressure the therapist). Resolution strategies by the therapist are conceptualised as immediate repair strategies with the aim of providing a rationale for treatment, clarifying misunderstandings, changing tasks or goals, or providing validation for defensive behaviour; and as expressive repair strategies with the aim of exploring patients’ core relational themes (Muran, 2017). Importantly, the rupture-repair model hypothesises that alliance ruptures disclose a window to patients’ dysfunctional interpersonal schemes and core needs. Therefore, alliance ruptures can serve as indicators for critical points within a therapy session that need to be explored by therapists (Safran, 1993; Safran & Muran, 1996). The resolution of alliance ruptures can offer a corrective emotional experience of these core interpersonal schemes to foster therapeutic change (Safran, 1993; Safran & Kraus, 2014; Safran, Muran, & Eubanks-Carter, 2011).

Empirical evidence from observer-based assessments of alliance ruptures and resolutions over the treatment course is sparse. In general, only two studies were published that assessed alliance ruptures in a limited subset of therapy sessions over the treatment course (Coutinho, Ribeiro, Fernandes, Sousa, & Safran, 2014; Gersh et al., 2016); based on a literature search in the databases PubMed, PsycINFO and Web of Science, accessed 27 November 2018 with the key term alliance rupture. The study by Gersh et al. (2016) showed that the proportion of sessions with a high number of ruptures increased over the treatment course of adolescents with BPD. Coutinho, Ribeiro, Fernandes, Sousa and Safran (2014) found a small increase in the intensity of withdrawal ruptures over the treatment course for all patients, whereas the intensity of confrontation ruptures increased only for dropout patients, not for the completers. Focusing on the early treatment phase (session one to four) in the treatment of Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) for BPD, a study by Boritz, Barnhart, Eubanks, and McMain (2018) reported a higher frequency of withdrawal ruptures in unrecovered compared to recovered patients. The emergence of withdrawal ruptures in subsequent therapy sessions persisted in unrecovered patients despite the degree of resolutions. Whereas in recovered patients, the probability of withdrawal ruptures decreased with an increasing degree of resolution.

On the basis of self-report questionnaires, several studies investigated specific patterns of alliance development. Kivlighan and Shaughnessy (2000) detected a stable, linear growth and a quadratic alliance development pattern. The quadratic alliance pattern resembles a high therapeutic alliance at the beginning, tear and repair processes in the middle, and a high therapeutic alliance at the end of the treatment. This quadratic alliance development pattern was associated with greater treatment improvement. However, findings in the subsequent study of Stiles et al. (2004) failed to replicate such a quadratic alliance pattern. Instead, a subsample of patients reported brief V-shaped deflections of sudden drops and repairs which were associated with greater treatment improvement.

Theoretical considerations of a quadratic alliance development trace back to the short-term dynamic psychotherapy of Mann (1973). For good outcome treatments, Mann (1973) assumes a good therapeutic alliance at an early phase, with an engaging therapist focusing on building a trustworthy and collaborative relationship. This phase is followed by considerable disturbances in the therapeutic alliance in the middle of treatment with periods of frustration, ambivalence, and resistance. Whereas at the end phase of treatment, the therapeutic alliance is strengthened with positive and more realistic reactions towards the therapist and the treatment. Derived from the theory of Mann (1973), alliance ruptures are to be expected predominantly in the mid-phase of treatment.

Research questions

This article investigates the timing, the typology and the significance of alliance ruptures over the complete treatment course with the aim to enhance the understanding of the mechanisms of change of how the therapeutic alliance works. Only recently, the study of specific types of alliance ruptures and resolutions was encouraged (Muran, 2017; Zilcha-Mano & Errázuriz, 2017). On the basis of a session-by-session investigation in a clinical sample of adolescents with BPP, we addressed three research questions: 1) Is there a typical trajectory of alliance ruptures over treatment time? 2) Which rupture and resolution markers occur frequently? 3) Which rupture markers are most significant for the therapeutic alliance?

Derived from the theory of Mann (1973), we hypothesised that alliance ruptures emerge according to an inverted U-shaped trajectory over treatment time. Therefore, alliance ruptures are expected to be with lower significance in the early phase, with higher significance during the middle phase and with lower significance in the final treatment phase (research question 1). For research questions 2 and 3, we followed an exploratory approach and raised no specific hypotheses.

Methods

Participants

Participants were ten adolescent patients receiving Adolescent Identity Treatment (AIT; Foelsch et al., 2014). Patients were aged 14 to 18 (M=15.9, SD=1.1) at baseline, nine were white Caucasian and one Asian. Nine were female and one was male. Nine were of middle and one was of low socioeconomic status (assessed with parent profession and parent level of education). Patients were treated with five to 25 individual sessions (M=19.2, SD=8.13) and two to eight family sessions (M=4.1, SD=1.73). Patients were drawn consecutively from its parental process-outcome study Evaluation of AIT Study that compares AIT and DBT-A in a non-inferiority trial. Patients were recruited from an outpatient child and adolescent psychiatric hospital. Inclusion criteria of the parental study were an identity diffusion assessed with the Assessment of Identity Development in Adolescence (AIDA; T-Score ≥60), (Goth et al., 2012), and ≥ three BPD criteria assessed with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Disorders (SCID-II), (First, Gibbon, Spitzer, Williams, & Benjamin, 1997). Exclusion criteria were IQ<80, psychotic disorders, pervasive developmental disorders, severe somatic or neurological disorders, severe and persistent substance addiction, antisocial personality disorder and necessity for inpatient treatment (for details, Zimmermann et al., 2018). Patient demographics and baseline pathology are provided in Table 1.

Adolescent Identity Treatment

AIT (Foelsch et al., 2014) is a psychodynamic approach for the treatment of adolescents with personality disorders (PD). AIT integrates modified elements of transference- focused psychotherapy (TFP) (Clarkin, Kernberg, & Yeomans, 1999) with psychoeducation, behaviour-oriented home plans and systemic work with parents and institutions. The main techniques of AIT are clarification, confrontation, and interpretation. Therapists emphasis on affects in the here and now and focus on dominant object relationship dyads. In the present study, the AIT treatment consisted of 25 weekly individual therapy sessions and intermittent family sessions.

Five AIT therapists participated in this study. All AIT therapists had advanced training in AIT and came from medicine or psychology backgrounds. Four therapists treated two patients and one therapist treated three patients. Due to changes in personnel, therapists in the treatment of patient B changed at session 13. All AIT therapists received regularly expert supervision in AIT.

Procedure and data collection

The project was approved by the local ethics committee (Ethikkommission Nordwest- und Zentralschweiz). All participants gave their written consent for participation. Treatment outcome was measured with the Children’s Global Assessment Scale (CGAS) to assess the psychosocial functioning and with the Youth Outcome Questionnaire Self-Report (Y-OQ) to assess psychopathology. Treatment outcome was assessed at baseline, post-line and monthly during the treatment (Y-OQ). All individual therapy sessions were video recorded with two synchronised cameras directed at the patient and the therapist.

Coding of the recorded therapy sessions

Alliance rupture and resolution markers were identified by two independent coders in video recordings of therapy sessions according to the manual of the Rupture Resolution Rating System (3RS) (Eubanks-Carter et al., 2015). Coders’ training involved reading the 3RS manual, training with a 3RS experienced research team from the Millennium Institute for Research in Depression and Personality, and rating and discussing of exercise material. Coders were blind to the study hypotheses and patients’ diagnoses. The complete data collection of the video analysis is based on consensual coding according to a three-step qualitative procedure: i) Independent coding phase: each therapy session was rated independently by each coder; ii) Intersubjective consensus meeting: the two coders compared and re-evaluated their coding. If coders did not achieve agreement, an observed event was marked for supervision; iii) Supervisor meeting: data collection was supervised by the first author in monthly meetings in which unclear events were re-evaluated.

Coders indicated with start and stop markers the beginning and the end of rupture and resolution episodes and rated the observed rupture and resolution markers within these episodes. Following this procedure, coders observed episodes of only rupture markers, only resolution markers and mixed episodes with rupture and resolution markers. The observed time lengths of the respective episodes were for rupture episodes: Mean=55.8 seconds (s), Min.=2.16 s, Max.=483.84 s, for resolution episodes: Mean=74.34 s, Min.=6.20 s, Max.=213.28 s, and for mixed episodes: Mean=149.47 s, Min.=5.68, Max.=1140.48 s. In a second step, the significance was rated for each rupture episode with the rupture significance rating from the 3RS. To evaluate the significance of a rupture, the coders observe changes in the collaboration between patient and therapist after an observed rupture.

Table 1.

Patient demographics.

| Patient | Age | Gender | Primary Diagnosis | Level of Education | Study Status | N. of Individual Sessions | N. of Family Sessions | Medication | Baseline Score in Y-OQ | Baseline Score in CGAS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 16 | Female | BPD | Academic upper secondary school | Completer | 25 | 4 | SSRI | 96 | 55 |

| B | 16 | Female | BPD | Academic upper secondary school | Completer | 25 | 5 | None | 115 | 42 |

| C | 16 | Female | BPD | Lower secondary school | Completer | 25 | 2 | None | 92 | 50 |

| D | 15 | Female | Subthreshold BPD | Academic upper secondary school | Completer | 18 | 4 | None | 42 | 50 |

| E | 1 5 | Female | Subthreshold BPD | Academic upper secondary school | Completer | 24 | 3 | None | 88 | 53 |

| F | 18 | Female | Subthreshold BPD | Lower secondary school | Completer | 25 | 5 | SSRI | 94 | 41 |

| G | 17 | Female | BPD and Avoidant PD | Lower secondary school | Completer | 25 | 4 | SSRI, MPH | 100 | 45 |

| H | 16 | Female | BPD | Academic upper secondary school | Dropout | 14 | 8 | Melatonin, SSRI | 102 | 48 |

| I | 14 | Male | BPD and Schizotypal PD | Academic upper secondary school | Dropout | 5 | 2 | MPH | 155 | 35 |

| J | 16 | Female | BPD and Avoidant PD | Academic upper secondary school | Dropout | 6 | 4 | SSRI | 95 | 42 |

The lower secondary school refers to the Swiss school system Hauptschulabschluss. The academic upper secondary school refers to the Gymnasium, the Weiterbildungsschule or the Fachmaturitätsschule. Y-OQ, youth outcome questionnaire; CGAS, clinical global assessment scale; BPD, borderline personality disorder; PD, personality disorder; SSRI, serotonin-reuptake-inhibitors; MPH, methylphenidate.

Measures

Rupture and Resolution Rating System

The 3RS (Eubanks-Carter et al., 2015) is an observerbased reliable coding system to assess alliance rupture and resolution markers in psychotherapy. The 3RS differentiates between two types of ruptures; withdrawal and confrontation. It includes seven withdrawal markers, seven confrontation markers and ten resolution markers (a detailed description can be found in the manual; Eubanks- Carter et al., 2015). In addition, the 3RS provides a rupture significance rating using a five-point Likert scale ranging from no significance to high significance. It assesses the immediate impact that rupture markers inflict on the therapeutic alliance with respect to the impairment in collaboration regarding goals, tasks and the affective bond. The 3RS has demonstrated very good levels of interrater reliability (ICCs=.85 to .98; Eubanks, Lubitz, Muran, & Safran, 2018).

The following measures were derived from the coding with the 3RS; rupture significance on the session level (RSS), rupture significance on the marker level (RSM), and the frequency of rupture and resolution markers. To analyse research question 1, the RSS was aggregated from the within-session coding. It represents the cumulative sum of the significance rating (Table 2) of each rupture episode in a given therapy session. The RSS accounts for the different impact or strain on the therapeutic alliance of all alliance ruptures per session. The measure description of the RSS of the present sample was M=4.78, SD=5.69. To analyse research question 3, the RSM was derived from the significance rating (Table 2) of each specific rupture marker. The RSM represents the immediate impact or strain of a given rupture marker on the therapeutic alliance.

Children’s Global Assessment Scale

The CGAS (Shaffer et al., 1983) is a 100-point singleitem rating scale which reflects the overall psychosocial functioning in the major areas of functioning, i.e. at home with family, in school, with friends, and during leisure time. The CGAS demonstrated high interrater reliability and concurrent and discriminant validity (Bird, 1987).

Youth-Outcome Questionnaire

The Y-OQ®-SR 2.0 (Wells, Burlingame, & Rose, 2003) is a self-report questionnaire for adolescents aged 12 to 18 years designed to assess treatment progress. The Y-OQ consists of 64 items presented on a 5-point scale. It assesses a total distress score and six subscales for the following domains: intrapersonal problems, somatic complaints, interpersonal relation, social problems, behavioral dysfunction, and critical items. The Y-OQ demonstrated very good internal consistency and test-retest reliability, and moderate to good concurrent validity (Ridge, Warren, Burlingame, Wells, & Tumblin, 2009). For the present study, the total distress score was used.

Data analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the package lme4 (Bates, Mächler, Bolker, & Walker, 2015) in the statistical software R (R Core Team, 2017). Two linear mixed-effect models using glmer with the Poisson distribution were performed. For model 1, the dependent variable was rupture significance (RSS) with the fixed effect therapy session and the random effect subject intercept. For model 2, the dependent variable was RSS with the fixed effect of a second-order polynomial of therapy session (represents an inverted U-shaped trajectory) and the random effect subject intercept. Significance of effect was obtained by likelihood ratio tests comparing the two models with the use of Akaike’s Information Criterion (AIC) (Winter, 2013). Visual inspection of residual plots did not reveal major deviations from normality or homoscedasticity. For research questions 2 and 3, descriptive data and independent t-tests were used. A total of 187 therapy sessions were analysed. Five sessions were not recorded due to technical errors. For research question 1, patients I and J had to be excluded due to their early treatment dropout.

Table 2.

Descriptive of alliance rupture and resolution processes per session.

| Mean | SD | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency of rupture episodes | 2.05 | 2.13 | 0–11 |

| Frequency of withdrawal ruptures | 1.17 | 1.3 | 0–6 |

| Frequency of confrontation ruptures | .89 | 1.46 | 0–8 |

| Rupture significance | 4.78 | 5.69 | 0–36 |

| Frequency of resolution episodes | 1.12 | 1.51 | 0–10 |

SD, standard deviation.

Results

Preliminary analysis

All completers reported a reduction in psychopathology (Y-OQ) and an improvement in psychosocial functioning (CGAS). Mixed-effect model analysis with a fixed effect of time and a random intercept of patient showed a significant monthly reduction in psychopathology symptoms of −3.11±.96 (standard errors) (χ2(1)=9.16, P<.001). The mean improvement in psychosocial functioning of the sample was 21.43±5.74 SD.

Descriptive statistics of alliance ruptures and resolution processes of the complete sample are displayed in Table 2. In 72.2% of all therapy sessions, at least one rupture episode was observed. Coders observed on average two rupture episodes per session (M=2.05, SD=2.13). Of these, 57% were withdrawal rupture episodes (M=1.17, SD=1.3) and 43% were confrontation ruptures (M=.89, SD=1.46). Therapists responded with resolution attempts in 73.3% of sessions with alliance ruptures (M=1.12, SD=1.51).

Main analysis

Research question 1: trajectory of alliance ruptures over treatment time

In line with our hypothesis, the trajectory of the RSS over treatment time was better represented by model 2 with a second-order polynomial predictor of therapy session (inverted U-shaped trajectory) compared to model 1 with a linear predictor of therapy session. The model comparison with likelihood ratio tests was significant (χ2(1)=20.24, P<.001, AIC model 1=1209.6 vsAIC model 2=1191.3, Table 3).

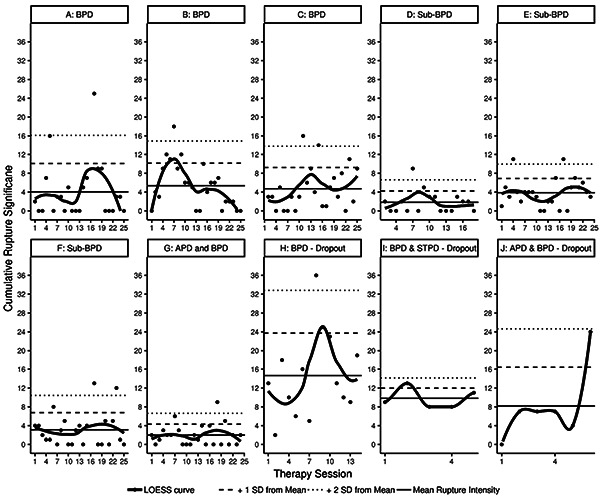

Second, we inspected individual trajectories using visual analysis (Figure 1). We applied a locally weighted scatter-plot smoother (Cleveland, 1979; Cleveland & Devlin, 1988) and methods derived from single case research designs (Blampied, 1999; Cooper, Heron, & Heward, 1987). Therapy sessions above the individual thresholds (>1 or 2 SD from mean) indicate salient and rupture intensive therapy sessions. The findings from Figure 1 are organised as within-patient and between-patient observations. Within patients, we observed a nonlinear trajectory of RSS over treatment time. For all patients, we observed alliance struggle phases or alliance struggle peaks. Alliance struggle phases are successive therapy sessions of impactful alliance ruptures, primarily over the individual’s threshold of RSS (>1 SD). For instance, a predominately high RSS with a peak at session seven was observed in patient B in therapy sessions five to nine. Alliance struggle peaks are single therapy sessions in which particularly impactful alliance ruptures emerged (>2 SD) with preceding and following therapy sessions of low RSS. For instance, two alliance struggle peaks accompanied by preceding and following low RSS sessions were observed in patient F in therapy sessions 17 and 23. Between patients, we observed salient differences in their mean level of RSS. Dropout patients presented with a higher mean level of RSS in the early treatment phase (sessions one to five) compared to the completers. Patients with fulfilled BPD (patients A, B, C, H, I, J) presented with predominantly higher mean levels of RSS compared to patients with subthreshold BPD (patients D, F). These findings are based on visual analyses and were not examined statistically due to the small sample size.

Table 3.

Parameter estimates of model 2.

| Fixed effects (intercept, slopes) | Estimate | SE | z-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 1.37 | .22 | 6.31 |

| First-order polynomial of session | − .01 | .56 | .99 |

| Second-order polynomial of session | −2.30 | .52 | -4.4* |

SE, standard error.

*P<.001.

Research question 2: predominant rupture and resolution markers

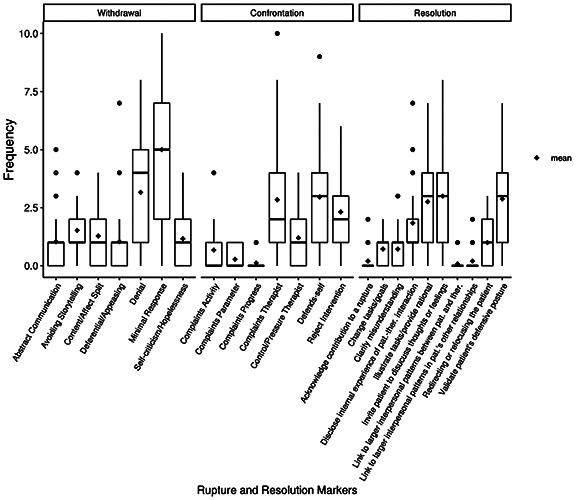

Figure 2 displays the frequency of specific rupture and resolution markers per session. The most frequent withdrawal rupture markers were minimal response, denial and avoidant storytelling. The most frequent confrontation rupture markers were patient defends self against therapist, complaints against therapist, followed by patient rejects therapist intervention. Therapists addressed alliance ruptures most often with the resolution strategies to invite the patient to discuss thoughts and feelings about the therapist or some aspect of therapy, to validate the patient’s defensive posture and to illustrate tasks or provide a rationale for treatment. Overall, rupture markers from the withdrawal type (M=2.03, SD=2.26) occurred more often than rupture markers from the confrontation type (M=1.49, SD=1.92), t (338.9)=2.42, P=.02.

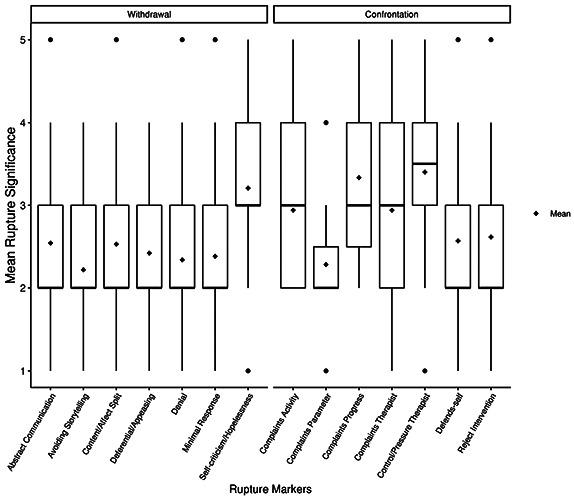

Research question 3: significance of specific rupture markers

Figure 3 displays the mean significance (RSM) of specific rupture markers based on the coders’ evaluation of their immediate impact on the collaboration between patient and therapist with respect to therapy goals, tasks, and the affective bond. The withdrawal rupture marker self-criticism or hopelessness and the confrontation rupture markers efforts to control or pressure therapist, complaints or concerns about progress in therapy, complaints or concerns about activities in therapy inflicted the highest impact on the therapeutic alliance. An independent-samples t-test was conducted to compare the significance of rupture markers from the withdrawal vs confrontation rupture type. Confrontation rupture markers (M=2.81, SD=1.00) were rated to inflict a significantly higher impact on the therapeutic alliance compared to withdrawal rupture markers (M=2.46, SD=0.99); t (534.5)=4.24, P>.001.

Discussion

The present study investigates the timing, the typology and the significance of alliance ruptures over the course of psychotherapy with adolescents with BPP. We raised the hypothesis that alliance ruptures emerge most intensively in the middle of treatment (according to an inverted U-shaped trajectory). This hypothesis was supported by the results of a mixed-effect model using a second-order polynomial predictor of therapy sessions. However, a critical investigation of individual trajectories revealed that alliance ruptures emerged not per se in the middle of the treatment but were observed intensively within single sessions (alliance struggle peaks) or within phases of successive sessions (alliance struggle phases).

The present study expands the research body on alliance development with the investigation of the timing of the ongoing, dynamic therapeutic alliance based on alliance ruptures and resolutions. Previous studies reported four major alliance patterns that were found based on self-report questionnaires: a linear growth pattern (increase or decrease over time); a stable pattern (initial level that remains over time); a quadratic pattern (U-shaped); and local rupture– repairs (downward shift that returns to the previous level in subsequent sessions) (Kivlighan & Shaughnessy, 2000; Stevens, Muran, Safran, Gorman, & Winston, 2007; Stiles et al., 2004). The present findings support a quadratic alliance development (according to an inverted U-shaped trajectory) with the presence of multiple local rupture–repairs throughout the treatment course. One previous study investigated the complete course of alliance ruptures in adolescents with BPD. In contrast to our findings, Gersh et al. (2016) reported an increasing proportion of sessions with a high number of ruptures over treatment time. This difference might be due to methodological dissimilarities between the two studies, including: the selection of coded therapy sessions (three selected sessions of an early, mid and late phase in the study by Gersh et al. (2016) vs complete assessment of all therapy sessions in our case); the treatment length (16 vs 25 sessions); or the clinical sample (patients with BPD vs patients with BPP).

Figure 1.

Individual trajectories of alliance ruptures across treatment time. The individuals’ thresholds in rupture significance (RSS) represent +1 and +2 SD from the individuals’ mean in RSS. The change in RSS is displayed with the locally weighted scatter-plot smoother (LOESS) regression curve. BPD, borderline personality disorder; APD, avoidant personality disorder; STPD, schizotypal personality disorder.

As the second finding, we found withdrawal rupture markers to occur more frequently compared to confrontation rupture markers. This observation is in line with findings on adult patients with primarily mood disorders (Eubanks et al., 2018), as well as on adolescents with BPD in early therapy sessions (Gersh et al., 2016). However, our finding contradicts to the study by Boritz et al. (2018) on adult patients with BPD in which more confrontation than withdrawal ruptures were observed in early therapy sessions. Future research needs to clarify if this finding is specific for adolescents who might possibly due to age and role differences to the therapist react in a more withdrawing than confrontational manner at the beginning of treatment.

The resolution strategy to invite thoughts and feelings was used most frequently by our therapists. We assume that this strategy does not only reflect a strategy to repair alliance ruptures but is also part of the most important AIT technique of clarification. Clarification is a specific technique in the treatment of identity diffusion seeking to facilitate the adolescent’s developing awareness of his or her own experience (Foelsch et al., 2014, p. 88). Clarification is also very predominant in the mentalization-based treatment for adolescents (MBT-A) aiming to enhance clients’ functioning of mentalization (Rossouw & Fonagy, 2012). The resolution strategy to invite thoughts and feelings might, therefore, play a particular role in the treatment of BPD patients with the core symptom of identity diffusion. As a further interesting finding, we found the markers to validate the patient defensive posture and to illustrate tasks/provide a rationale for treatment under the top three most provided resolution strategies. These strategies reflect two of the four fundamental factors in psychotherapy described by Frank and Frank (1991), namely: i) an emotional trusting relationship (i.e. validate the patients position), ii) a setting for healing, iii) a rationale that explains reasons for symptoms and interventions (i.e. illustrate tasks and provide a rationale for treatment), iv) a procedure/ritual with active participation of patient and therapist. This finding supports the stance that rupture-repair processes reflect important mechanisms of change of the therapeutic alliance.

Figure 2.

Frequency of specific rupture and resolution markers per session.

As the third finding, we found confrontation rupture markers (e.g., efforts to control or pressure therapist or complaints or concerns about progress in therapy) to inflict a higher immediate impact on the therapeutic alliance compared to withdrawal markers. Therapists might feel more personally pressured by confrontation than by withdrawal ruptures. In line with this reasoning, our data showed that the confrontation rupture marker efforts to control or pressure therapist had the highest impact on the therapeutic alliance. In line with our reasoning, Eubanks et al. (2018) found that the frequency of confrontation ruptures was negatively associated with the patients’ (r=−.32, P=.054) and therapists’ (r=−.50, P=.002) rated working alliance. For patients, the therapeutic discourse might trigger core interpersonal schemes that are associated with resistance, ambivalence and a confrontational defence. Especially in BPD patients, interpersonal problems are at the core of their psychopathology. In line with this reasoning, Sommerfeld, Orbach, Zim, and Mikulincer (2008) found alliance ruptures of the confrontation type, but not the withdrawal type, to be associated with the presence of patients’ dysfunctional interpersonal schemes.

Ruptures are regarded as strategies to deal with the tension between self-definition and relatedness to the other (Lingiardi, Holmqvist, & Safran, 2016). This conceptualisation of alliance ruptures highlights the intra- and interpersonal functioning which is significantly impaired in patients with BPD (Chanen, Jovev, & Jackson, 2007; Lazarus, Cheavens, Festa, & Zachary Rosenthal, 2014). Previous studies showed that patients with impairments in interpersonal functioning experience higher rupture intensity (Muran et al., 2009) and lower therapeutic alliance (Constantino & Smith-Hansen, 2008; Hersoug, Høglend, Havik, Lippe, & Monsen, 2009). Particularly in the treatment of adolescents with BPP, the identity diffusion is the core symptom of the disease which is characterised by an inability to integrate continuous and coherent aspects of the self (Becker et al., 2002; Goth et al., 2012). The therapeutic alliance plays a central role to overcome rigid and biased representations of self and others (Levy et al., 2006) and to enhance reflective functioning (Diamond, Stovall-McClough, Clarkin, & Levy, 2003). Safran (1993) and Safran and Muran (1996) suppose that alliance ruptures disclose a window into core interpersonal themes. Thus, the therapeutic alliance can serve as an interpersonal learning field in which representations of the self and others can be probed in the here and now of the secure therapeutic relationship. Within this interpersonal learning field, alliance ruptures and resolutions emerge inevitably and can be regarded as important events to coming to accept the self and others (Safran, Crocker, McMain, & Murray, 1990).

Figure 3.

Significance of specific rupture markers per session.

Future research

As a methodological aspect, future research should proceed with caution in selecting single therapy sessions for the coding of alliance ruptures. Due to the high between- session variability observed in the present sample, it is suggested to select multiple successive therapy sessions to characterise treatment phases. The coding of therapy sessions is of very high clinical significance but very time-consuming. Future projects should invest in developing innovative and automated methods to detect alliance ruptures as for example automated speaker diarization and voice analysis (Fürer et al., submitted for publication in 2019). As a further topic, we encourage to investigate the impact of patient characteristics on alliance rupture–repair processes. It is of interest to better understand the role of identity diffusion, severity in borderline pathology, depression, psychosocial functioning or treatment expectation in rupture–repair processes. Finally, it would be of interest to study the process of rupture-repair not only in AIT with techniques derived from TFP but also in other approaches such as DBT or MBT. Future projects with other therapeutic approaches and other clinical samples would be helpful to answer the question if our results are specific for the AIT treatment of adolescents with BPP or if they can be generalized to other approaches and other disorders in non-adolescent populations.

Strengths and limitations

A major strength of the present study is the complete observation of alliance ruptures and resolutions on a session- by-session basis. This observation enables a holistic assessment of alliance rupture processes over time. We investigated an understudied, sensible clinical sample in a natural treatment setting and offer a high ecological validity and clinical relevance. Due to the small sample size, intraindividual processes can be studied in depth which generates further empirical hypotheses. Although small samples are common in psychotherapy process research, potential biases and limitations of the study should be considered. The sample was small and imbalanced with respect to study status (seven completers, three dropouts), gender (nine females, one male) and diagnoses (four fulfilled BPD, three subthreshold BPD, three BPD with comorbid PD). This major limitation impedes the generalisation of the findings. Also, the change of therapists in the treatment of patient B might impact the alliance development and the emergence of ruptures over time. Lastly, we considered the frequency and significance of ruptures in our analyses without controlling for the length of rupture episodes. In post-hoc analyses, we observed a great in-session and between-patient variability in length of rupture episodes. For future research, it is of importance to further explore the impact of rupture duration.

Conclusions

The present findings suggest that clinicians should expect alliance ruptures to occur frequently in the treatment of adolescence with BPP. As this pattern was observed in seven good outcome patients, the study provides initial evidence for the beneficial effect of rupture–repair processes in adolescents with identity diffusion. The emergence of alliance ruptures is not per se an indicator for an impaired treatment course, but might constitute a normal process to foster identity integration in adolescents with BPP. The findings support the theory of the therapeutic alliance as a dynamic entity characterised by a continuous intersubjective negotiation between patients and therapists (Lingiardi et al., 2016; Safran, 1993; Safran & Muran, 2006). This negotiation process is, at times, more dysregulated, which manifests in single therapy sessions or phases of higher rupture significance, mainly in the middle of the treatment.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Pamela Foelsch and Andrés Borzutzky of the Schildkrut Institute in Santiago de Chile for their contributions.

Funding Statement

Funding: the study is funded by University of Basel and the Psychiatric University Hospital, Basel, Switzerland.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5®). Arlington, VA, US: American Psychiatric Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Bates D., Mächler M., Bolker B., Walker S. (2015). Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software, 67(1), 1-48. doi: 10.18637/jss.v067.i01 [Google Scholar]

- Becker D. F., Grilo C. M., Edell W. S., McGlashan T. H. (2002). Diagnostic efficiency of borderline personality disorder criteria in hospitalized adolescents: Comparison with hospitalized adults. American Journal of Psychiatry, 159(12), 2042-2047. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.12.2042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird H. R. (1987). Further measures of the psychometric properties of the children’s global assessment scale. Archives of General Psychiatry, 44(9), 821. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1987.01800210069011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blampied N. M. (1999). A legacy neglected: Restating the case for single-case research in cognitive-behaviour therapy. Behaviour Change, 16(02), 89-104. doi: 10.1375/bech.16.2.89 [Google Scholar]

- Bordin E. S. (1979). The generalizability of the psychoanalytic concept of the working alliance. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research & Practice, 16, 252.260. doi: 10.1037/h0085885 [Google Scholar]

- Boritz T., Barnhart R., Eubanks C. F., McMain S. (2018). Alliance rupture and resolution in dialectical behavior therapy for borderline personality disorder. Journal of Personality Disorders, 32(Supplement), 115-128. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2018.32.supp.115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castonguay L. G., Constantino M., Holtforth M. G. (2006). The working alliance: Where are we and where should we go? Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 43(3), 271-279. doi: 10.1037/0033-3204.43.3.271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chanen A. M., Jovev M., Jackson H. J. (2007). Adaptive functioning and psychiatric symptoms in adolescents with borderline personality disorder. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 68(2), 297-306. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v68n0217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chanen A. M., Sharp C., Hoffman P. The Global Alliance for Prevention and Early Intervention for Borderline Personality Disorder (2017). Prevention and early intervention for borderline personality disorder: a novel public health priority. World Psychiatry, 16(2), 215-216. doi: 10.1002/ wps.20429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarkin J. F., Kernberg O. F. (2006). Psychotherapy for borderline personality: Focusing on object relations. Arlington, VA, US: American Psychiatric Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Clarkin J. F., Kernberg O. F., Yeomans F. E. (1999). Transference- focused psychotherapy for borderline personality disorder patients. New York: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Cleveland W. S. (1979). Robust locally weighted regression and smoothing scatterplots. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 74(368), 829-836. doi: 10.2307/2286407 [Google Scholar]

- Cleveland W. S., Devlin S. J. (1988). Locally weighted regression: an approach to regression analysis by local fitting. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 83(403), 596-610. doi: 10.2307/2289282 [Google Scholar]

- Constantino M., Smith-Hansen L. (2008). Patient interpersonal factors and the therapeutic alliance in two treatments for bulimia nervosa. Psychotherapy Research, 18(6), 683-698. doi: 10.1080/10503300802183702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper J. O., Heron T. E., Heward W. L. (1987). Applied behavior analysis. Columbus, OH: Merrill. [Google Scholar]

- Coutinho J., Ribeiro E., Fernandes C., Sousa I., Safran J. D. (2014). The development of the therapeutic alliance and the emergence of alliance ruptures. Anales de Psicología/Annals of Psychology, 30(3), 985-994. doi: 10.6018/analesps.30.3.168911 [Google Scholar]

- Diamond D., Stovall-McClough C., Clarkin J. F., Levy K. N. (2003). Patient-therapist attachment in the treatment of borderline personality disorder. Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic, 67(3), 227-259. doi: 10.1521/bumc.67.3.227.23433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doran J. M. (2016). The working alliance: Where have we been, where are we going? Psychotherapy Research, 26(2), 146-163. doi: 10.1080/10503307.2014.954153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ensink K., Biberdzic M., Normandin L., Clarkin J. (2015). A developmental psychopathology and neurobiological model of borderline personality disorder in adolescence. Journal of Infant, Child, and Adolescent Psychotherapy, 14(1), 46-69. doi: 10.1080/15289168.2015.1007715 [Google Scholar]

- Erikson E. H. (1959). The theory of infantile sexuality. Erikson E. (Ed.), Childhood and society (pp. 42-92). New York: W. W. Norton. [Google Scholar]

- Erikson E. H. (1982). The life cycle completed: A review. New York: W.W. Norton. [Google Scholar]

- Eubanks C. F., Lubitz J., Muran J. C., Safran J. D. (2018). Rupture resolution rating system (3RS): Development and validation. Psychotherapy Research, 29(3), 1-14. doi: 10.1080/10503307.2018.1552034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eubanks-Carter C. F., Muran J. C., Safran J. D. (2015). Rupture resolution rating system (3RS): Manual. New York: Mount Sinai-Beth Israel Medical Center. Retrieved from: http://www.researchgate.net/profile/Catherine_Eubanks/publication/270581021_RUPTURE_RESOLUTION_RATING_SYSTEM_(3RS)_MANUAL/links/54aecb390cf2966 1a3d3ad4c.pdf [Google Scholar]

- First M. B., Gibbon M., Spitzer R. L., Williams J. B. W., Benjamin L. S. (1997). Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV axis II personality disorders (SCID-II). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press. [Google Scholar]

- Foelsch P. A., Schlüter-Müller S., Odom A. E., Arena H. T., Borzutzky H. A., Schmeck K. (2014). Adolescent identity treatment. Cham: Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Fonagy P., Gergely G., Jurist E. L., Target K. (2002). Affect regulation, mentalization, and the development of the self. New York: Other Press, LLC. [Google Scholar]

- Fonagy P., Speranza M., Luyten P., Kaess M., Hessels C., Bohus M. (2015). ESCAP Expert Article: Borderline personality disorder in adolescence: An expert research review with implications for clinical practice. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 24(11), 1307-1320. doi: 10.1007/ s00787-015-0751-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank J. D., Frank J. B. (1991). Persuasion and healing: A comparative study of psychotherapy. Baltimore: MD: John Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fürer L., Schenk N., Steppan M., Schlüter-Müller S., Koenig J., Kaess M., Zimmermann R. (2019). Supervised speaker diarization: A method to study the conversational structure of psychotherapy. Manuscript submitted for publication. [Google Scholar]

- Gersh E., Hulbert C. A., McKechnie B., Ramadan R., Worotniuk T., Chanen A. M. (2016). Alliance rupture and repair processes and therapeutic change in youth with borderline personality disorder. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 90(1), 84-104. doi: 10.1111/papt.12097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goth K., Foelsch P., Schlüter-Müller S., Birkhölzer M., Jung E., Pick O., Schmeck K. (2012). Assessment of identity development and identity diffusion in adolescence - Theoretical basis and psychometric properties of the self-report questionnaire AIDA. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 6(1), 27. doi: 10.1186/1753-2000-6-27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hersoug A. G., Høglend P., Havik O. E., Lippe A. von der, Monsen J. T. (2009). Pretreatment patient characteristics related to the level and development of working alliance in long-term psychotherapy. Psychotherapy Research, 19(2), 172–180. doi: 10.1080/10503300802657374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath A. O., Del Re A. C., Flückiger C., Symonds D. (2011). Alliance in individual psychotherapy. Psychotherapy, 48(1), 9-16. doi: 10.1037/a0022186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaess M., Brunner R., Chanen A. (2014). Borderline personality disorder in adolescence. Pediatrics, 134(4), 782-793. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-3677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karver M., Handelsman J., Fields S., Bickman L. (2006). Meta-analysis of therapeutic relationship variables in youth and family therapy: The evidence for different relationship variables in the child and adolescent treatment outcome literature. Clinical Psychology Review, 26(1), 50-65. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kernberg O. F. (1984). Severe personality disorders: Psychotherapeutic strategies. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kivlighan D. M. J., Shaughnessy P. (2000). Patterns of working alliance development: A typology of client’s working alliance ratings. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 47(3), 362-371. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus S. A., Cheavens J. S., Festa F., Zachary Rosenthal M. (2014). Interpersonal functioning in borderline personality disorder: A systematic review of behavioral and laboratory- based assessments. Clinical Psychology Review, 34(3), 193-205. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2014.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy K. N., Clarkin J. F., Yeomans F. E., Scott L. N., Wasserman R. H., Kernberg O. F. (2006). The mechanisms of change in the treatment of borderline personality disorder with transference focused psychotherapy. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 62(4), 481-501. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lingiardi V., Colli A. (2015). Therapeutic alliance and alliance ruptures and resolutions: theoretical definitions, assessment issues, and research findings. Gelo O. C. G., Pritz A., Rieken B. (Eds.), Psychotherapy research: Foundations, process, and outcome (pp. 311-329). Vienna, Austria: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Lingiardi V., Holmqvist R., Safran J. D. (2016). Relational turn and psychotherapy research. Contemporary Psychoanalysis, 52(2), 275-312. doi: 10.1080/00107530.2015. 1137177 [Google Scholar]

- Mann J. (1973). Time-limited psychotherapy. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Martin D. J., Garske J. P., Davis M. K. (2000). Relation of the therapeutic alliance with outcome and other variables: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting, 68(3), 438-450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMain S. F., Boritz T. Z., Leybman M. J. (2015). Common strategies for cultivating a positive therapy relationship in the treatment of borderline personality disorder. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 25(1), 20-29. doi: 10.1037/ a0038768 [Google Scholar]

- Miller A. L., Muehlenkamp J. J., Jacobson C. M. (2008). Fact or fiction: Diagnosing borderline personality disorder in adolescents. Clinical Psychology Review, 28(6), 969-981. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muran J. C. (2017). Confessions of a New York rupture researcher: An insider’s guide and critique. Psychotherapy Research, 29(1), 1-14. doi: 10.1080/10503307.2017.1413261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muran J. C., Safran J. D., Gorman B. S., Samstag L. W., Eubanks-Carter C., Winston A. (2009). The relationship of early alliance ruptures and their resolution to process and outcome in three time-limited psychotherapies for personality disorders. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 46(2), 233-248. doi: 10.1037/a0016085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. (2009). Borderline personality disorder: recognition and management (NICE guideline 78). Retrieved from https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg78 [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. (2017). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Retrieved from https://www.R-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- Ridge N. W., Warren J. S., Burlingame G. M., Wells M. G., Tumblin K. M. (2009). Reliability and validity of the youth outcome questionnaire self-report. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 65(10), 1115-1126. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossouw T. I., Fonagy P. (2012). Mentalization-based treatment for self-harm in adolescents: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 51(12), 1304-1313.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.09.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safran J. D. (1993). Breaches in the therapeutic alliance: An arena for negotiating authentic relatedness. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 30(1), 11-24. doi: 10.1037/0033-3204.30.1.11 [Google Scholar]

- Safran J. D., Crocker P., McMain S., Murray P. (1990). Therapeutic alliance rupture as a therapy event for empirical investigation. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 27(2), 154-165. doi: 10.1037/0033-3204.27.2.154 [Google Scholar]

- Safran J. D., Kraus J. (2014). Alliance ruptures, impasses, and enactments: A relational perspective. Psychotherapy, 51(3), 381-387. doi: 10.1037/a0036815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safran J. D., Muran J. C. (1996). The resolution of ruptures in the therapeutic alliance. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 64(3), 447-458. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.64.3.447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safran J. D., Muran J. C. (2006). Has the concept of the therapeutic alliance outlived its usefulness? Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 43(3), 286-291. doi: 10.1037/0033-3204.43.3.286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safran J. D., Muran J. C., Eubanks-Carter C. (2011). Repairing alliance ruptures. Psychotherapy, 48(1), 80-87. doi: 10.1037/a0022140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer D., Gould M. S., Brasic J., Ambrosini P., Fisher P., Bird H., Aluwahlia S. (1983). A children’s global assessment scale (CGAS). Archives of General Psychiatry, 40(11), 1228-1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp C., Fonagy P. (2015). Practitioner Review: Borderline personality disorder in adolescence - recent conceptualization, intervention, and implications for clinical practice. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 56(12), 1266-1288. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp C., Wright A. G. C., Fowler J. C., Frueh B. C., Allen J. G., Oldham J., Clark L. A. (2015). The structure of personality pathology: Both general (‘g’) and specific (‘s’) factors? Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 124(2), 387-398. doi: 10.1037/abn0000033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirk S. R., Karver M. (2003). Prediction of treatment outcome from relationship variables in child and adolescent therapy: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting, 71(3), 452-464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommerfeld E., Orbach I., Zim S., Mikulincer M. (2008). An in-session exploration of ruptures in working alliance and their associations with clients’ core conflictual relationship themes, alliance-related discourse, and clients’ postsession evaluations. Psychotherapy Research, 18(4), 377-388. doi: 10.1080/10503300701675873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens C., Muran C. J., Safran J., Gorman B. S., Winston A. (2007). Levels and patterns of the therapeutic alliance in brief psychotherapy. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 61(2), 109-129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stiles W. B., Glick M. J., Osatuke K., Hardy G. E., Shapiro D. A., Agnew-Davies R., Barkham M. (2004). Patterns of alliance development and the rupture-repair hypothesis: Are productive relationships U-Shaped or V-Shaped? Journal of Counseling Psychology, 51(1), 81-92. [Google Scholar]

- Wells M., Burlingame G., Rose P. (2003). Youth outcome questionnaire self report. Wilmington, DE: American Professional Credentialing Services. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. (2018). ICD-11 for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics (ICD-11 MMS) 2018 version. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; Retrieved from: https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en Accessed: October 25, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Winter B. (2013). Linear models and linear mixed effects models in R with linguistic applications. ArXiv:1308.5499 [Cs.CL]. Retrieved from http://arxiv.org/abs/1308.5499 [Google Scholar]

- Zilcha-Mano S., Errázuriz P. (2017). Early development of mechanisms of change as a predictor of subsequent change and treatment outcome: The case of working alliance. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 85(5), 508-520. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann R., Krause M., Weise S., Schenk N., Fürer L., Schrobildgen C., Schmeck K. (2018). A design for process-outcome psychotherapy research in adolescents with borderline personality pathology. Contemporary Clinical Trials Communications, 12, 182-191. doi: 10.1016/j.conctc.2018.10.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]