Abstract

Schema therapy (ST) is a relatively new, but promising, psychotherapy approach. Able to be implemented in both individual and group settings, research findings suggest that ST is a highly effective treatment for personality disorders. As in other treatments for personality disorders, some patients decide to drop out from treatment, feeling they did not benefit. To date, there has been no study in the literature that investigates the dropout rates across ST studies specifically. Consequently, this study systematically researched eight different ST studies in which dropout rates were reported. Together, these studies featured both individual and group therapy settings, inpatient and outpatient settings, and different personality disorder diagnoses. The weighted mean dropout rate was 23.3%, 95% CI (14.8-31.7%) across these studies. Although this finding is very similar to those meta-analyses that obtained their dropout rates from different orientations and diagnoses, namely psychotherapy in general, ST’s dropout rates might be significantly lower than studies that included personality disorders in particular.

Key words: Schema therapy, Dropout, Premature termination, Personality disorder

Introduction

Schema therapy (ST) is a form of psychotherapy originally developed by Young in 1990 as an individual therapy focusing particularly on personality disorders and chronic life problems. ST combines aspects of cognitive, behavioral, psychodynamic, attachment, and gestalt models and integrates cognitive, behavioral, and experiential techniques. Along with the innovative and strong integrative basis of ST, some specific approaches related to the therapeutic relationship also have a strong emphasis, namely limited reparenting and empathic confrontation. ST should not be considered as a technical eclecticism effort. It combines all of these features with a strong theoretical background and offers a firm tool for change. According to ST, there are 18 schemas which develop as a consequence of unfulfilled emotional needs especially in childhood or traumatic events (Young, Koloskoi & Weishaar, 2003). Recent developments related to ST theory suggest that we should put emphasis on schema modes which might represent different schemas, emotional and behavioral patterns at the same time (Arntz & Jacob, 2013). ST offers limited reparenting and empathic confrontation via cognitive, behavioral, and experiential techniques to meet unfulfilled needs underlying of these schemas and modes. Variety of schemas and modes contributes flexibility of the ST and makes easier to use it in challenging situations such as personality disorder treatments. Moreover, in patients with several schemas and modes as in personality disorders, it could be easier to work with these modes than schemas because mode approach offers explanations for reasons of the cognitive, behavioral, and emotional patterns as well as coping mechanisms of these patterns (Arntz & Jacob, 2013).

Although initially ST was designed as an individual psychotherapy approach, it has been modified for use in group therapy (Farrell, Shaw, & Webber, 2009). Both the individual and group forms of the ST approach show promising findings in their effectiveness (Bamelis, Evers, Spinhoven, & Arntz, 2014; Farrell, et al., 2009; Giesen- Bloo et al., 2006; Nadort et al., 2009; Schaap, Chakhssi, & Westerhof, 2016). For example, Bamelis et al. (2014) conducted a study and compared 50 sessions of ST with the clarification oriented psychotherapy (CAP) and treatment as usual (TAU) in patients with cluster C personality disorders (e.g. paranoid, histrionic or narcissistic personality disorders). According to results, there were significant differences in terms of outcome and dropout rates between the treatment conditions. Firstly, greater proportion of ST patients recovered compared to TAU and COP and secondly dropout rate was significantly lower in ST and COP treatment conditions compared to TAU. In a different study, ST was superior to transference-focused psychotherapy (TFP) in borderline personality disorder (BPD) patients (Giesen-Bloo et al., 2006). In this study, Giesen-Bloo et al. randomly assigned BPD patients into ST (n=44) and TFP (n=42) treatment conditions which longed three years. At the end of three years, there were significant improvements in both treatment conditions yet survival analysis established that significantly more ST patients recovered or showed reliable clinical improvement. Additionally, the dropout rate was significantly lower in ST patients. In Nadort et al.’s (2009) study, the authors added therapist telephone availability to standard ST implementation for BPD patients in regular mental healthcare setting to improve the effectiveness of psychotherapy and compared it with standard ST. In general, sixty-two patients treated in this study and ST intervention was effective but therapist telephone availability did not increase the effectiveness of standard ST intervention. After 1.5 years 42% of the patients were no longer met the diagnostic criteria of BPD and the dropout rate was 21%.

Additional to aforementioned studies which were included individual psychotherapy interventions, there were two other studies which tested the effectiveness of schema focused group psychotherapy in personality disorders. In Farrell et al.’s (2009) study, the authors did a randomized control trial to test effectiveness of group implementation of ST in outpatient setting for BPD patients. The treatment included thirty sessions of group ST added to TAU. Thirty-two patients randomly assigned to TAU or ST + TAU groups. The results showed that at the end of the treatments 94% of ST + TAU patients and 16% of TAU patients were no longer met BPD diagnostic criteria. Twenty-five percent of the TAU patients dropped out while all of the ST + TAU patients stayed at the treatment. In a recent study, Schaap et al. (2016) evaluate the group ST for patients with personality pathology (i.e. 21.4% were BPD and 42.9% were nonspecific personality disorder patients) in inpatient setting. There were 65 patient at the beginning of the study. The patients did not benefit to previous psychotherapy interventions for their conditions. The treatment included twice sessions in a week for about 12 months. Forty-two of the patients completed the treatment and the dropout rate was 35%. According to the results, there were significant improvements regarding to maladaptive schemas and coping styles, schema modes, mental well-being, and psychological distress.

As discussed above, the findings of these studies reveal that ST has been important alternative for treating personality disorders that are prevalent and challenging mental health conditions. According to Torgersen (2005), 10-14% of the general population suffers from personality disorders. That study found a variation among other studies of 3.9-22.7%. The prevalence of personality disorders across psychiatric patients reaches almost 31% (Zimmerman, Rothschild, & Chelminski, 2005). By their nature, personality disorders and, in general terms, personality pathologies may reduce an individual’s life quality and psychological well-being, as well as a community’s functionality (Ishak et al., 2013). Among personality pathologies, while BPD has received more attention due to the difficulty of its treatment, other personality disorders also have direct and extensive effects on human beings and communities as a result of persistent and pervasive behavioral and emotional patterns of these personality traits.

In contrast to early studies and related thinking on the limitations of psychotherapy treating patients with personality disorders because of intrapersonal and interpersonal dysfunction (Diguer, Barber, & Luborsky, 1993; Ishak et al., 2013), recent evidence has shown that psychotherapy can be effective and efficacious in treating these conditions (Dixon-Gordon, Turner, & Chapman, 2011). Despite the changes in view of the treatment of personality disorders, it might still be as a challenging endeavor. The clinical complexity of personality disorders can be burdensome for psychotherapists and can even cause burnout (Rossberg, Karterud, Pedersen, & Friis, 2008). Individuals with a personality disorder present a variety of challenging behaviors that can be difficult to handle (Dixon- Gordon et al., 2011).Along with those personality traits included in personality disorders, comorbidity is also a critical issue. Both Axis I disorders and other medical conditions can co-occur (Frankenburg & Zanarini, 2006), which makes treatment more difficult as a consequence of complex treatment targets, formulation and prioritization issues. The need to develop innovative psychotherapy approaches for treating personality disorders, and at the same time establish a flexible and satisfying therapeutic environment for the psychotherapists, has consequently been raised. Due to its firm theoretical background, flexible structure and therapy relationship; adaptation of broad cognitive, emotional, and behavioral techniques, ST can be considered a solution, having been shown to be an effective treatment for personality disorders in both individual and group psychotherapy (Bamelis et al., 2014; Farrell, et al., 2009; Giesen-Bloo et al., 2006; Nadort et al., 2009; Schaap et al., 2016).

Nevertheless, dropout is still a problem, even for highly effective psychotherapies. Despite the emerging positive findings related to psychotherapy for almost all psychiatric conditions, some patients may not benefit from psychotherapy as a consequence of dropout. Various diagnosis and treatment approaches have shown varied results concerning dropout rates. One of the earliest findings suggested dropout rates between 31 and 79% (Baekland & Lundwall, 1975). In Wierzbicki and Pekarik’s (1993) meta-analysis, this rate was almost 47%. In another meta-analysis study, which included patients with Axis I and Axis II disorders, the overall dropout rate was 35.3% (Sharf, 2008). In a more recent and rigorous study, Swift and Greenberg (2012) concluded the weighted mean dropout rate was about 19.7% in a metaanalysis that included 669 studies featuring 83,834 patients with various psychological conditions. According to Swift and Greenberg, the only moderators related to the dropout rate were diagnosis and patient age. In the case of personality disorders, this dropout rate increased to 25.6%. More specifically, Barnicot, Katsakou, Marougka, and Priebe (2011) conducted a meta-analysis of treatment completion of BPD psychotherapy. Although completion rates were differ between 36% and 100% in studies, the authors found that approximately 25% of the patients dropped out in short term treatments (<12 months) and 29% dropped out in long term treatments (>12 months). In McMurran, Huband, and Overton’s (2010) study, the median dropout rate was 37% for personality disorders and 40.8% in a recent study by Gamache, Savard, Lemelin, Cote, and Villeneuve (2018). As can be seen from these studies, personality disorders have a greater risk of dropout. Psychotherapy dropout can be labeled differently –such as premature termination, attrition, etc. – but however termed, the indicators are the same: not showing up to the last appointment, therapist judgement, attending fewer then the specified number of therapy sessions, not completing the treatment protocol, and leaving the therapy before a clinically significant change occurs (Swift & Greenberg, 2012). Regardless of the reason behind it, dropout is an important risk factor for patients, therapists, and societies: while therapists might lose time and face overwhelming sense of failure, institutions might lose time/sources and money.

Despite high prevalence and negative consequences, underlying factors in dropout are still controversial. Along with patient characteristics such as diagnosis and comorbidity, there were other variables discussed in the literature regarding the psychotherapy dropout. For instance, although some studies reported that therapists’ level of experience was related to dropout (Baekland & Lundwall, 1975), some others did not (Krauskopf, Baumoardner, & Mandracchia, 1981). Akin to patients the most consisted variable in the literature was social-economic status (SES, Swift & Greenberg, 2012; Wierzbicki & Pekarik, 1993). According to the consisted findings, lower SES can be a risk factor for dropout. More recent studies found that matching with the patients’ preferences (i.e., therapy setting and therapy modality) are related to lower dropout rates (Swift, Callahan, & Vollmer, 2011). Moreover, a line of research has investigated the relationship between dropout rates and therapeutic relationship. In Roos and Werbart’s (2013) review, some variables such as the quality of the therapeutic alliance and the ability to provide emotional support were found to be affecting the dropout rates.

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the dropout rates of patients with personality disorders undergoing ST treatment. Although there have been studies analyzing the weighted mean dropout rates for personality-disorder treatments, no study has yet calculated the overall dropout rate in ST specifically. By conducting a systematic review of the literature, a weighted mean dropout rate was calculated from other ST studies. The results of this evaluation might help to compare ST with other psychotherapy approaches for personality disorders and with the broader picture of psychotherapy dropouts.

Materials and Methods

Literature search

A systematic search of the current literature was conducted on ProQuest, PsychArticles, PsychInfo, MEDLINE, Scopus, and Web of Science, following no time restriction of publication. The systematic search was carried out using a combination of the following words: schema therapy, schema focused therapy, dropout, premature termination, and attrition. Further to the database search, available references were manually searched.

The research included in this study must have (i) included participants who have personality disorder(s) and/or personality disorder traits, (ii) used an adult sample, (iii) involved face-to-face individual and/or group psychotherapy, (iv) been an empirical study, (v) been mainly based on ST (primary intervention must be either individual or group ST), and (vi) been available in English. Case studies and systematic case studies were excluded. The reason to loosen the inclusion criteria was to obtain an extensive and general picture of dropout in ST. From the search, 360 articles were found. After excluding duplications and articles that did not meet the inclusion criteria, eight studies were included in the present study.

Considering that these studies were not identical and dropout rates could vary, a random effects model was used to calculate the weighted mean dropout rate. The analysis was conducted using the open source meta-analysis software, Open Meta[Analyst] (Wallace et al., 2012). Only therapy setting (inpatient & outpatient) treated as a potential moderator variable because there is insufficient information in studies.

Results

A summary of the eight studies included in the current study is presented in Table 1. Of the total 693 participants, 421 participants were treated with individual or group ST. Individual ST was implemented in four studies and group ST in three studies; one study implemented a combination of individual and group ST.

Table 1.

Summary of included studies.

| Author(s) | Year | Study Country | Treatment Details | Diagnosis | Diagnostic Criteria | Treatment Adherence | In/Outpatient | N | N in schema therapy (ST) Groups | Age, mean (SD) | Sex | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Farrell, Shaw, & Webber | 2009 | USA | TAU Individual + 8 months 30 session group SFT (90 min weekly group sessions) | BPD | the DIB-R + the BSI | No information | Outpatient | 32 | 16 | 35.3 (9.3) (for the ST group) | 32 F | 0/16 |

| Dickhaut & Arntz | 2014 | The Netherlands | Combination of weekly (90 min) Group ST & Individual ST (1 h) | BPD | SCID- I & II | No information | Outpatient | 18 | 18 | 28.5 (8.7) | 18 F | 7/18 |

| Doyle et al. | 2016 | The UK | SFT + TAU Each session was planned for 60 min on a weekly basis for a minimum of 18 months | BPD or ASPD | SCID-II | The STRS | Patients in high secure hospital | 63 | 29 | 41.8 (9.9) (for the ST group) | 63 M | 5/63 |

| Nadort et al. | 2009 | The Netherlands | 45-min sessions twice a week. With/without extra phone support | BPD | SCID + the BPDSI | Supervisions and the STACS for BPD | Outpatient | 62 | 32 ST with phone support, 30 ST without phone support | 31.8 (9.2), 32.1 (9.0) | 60 F + 2 M | (7+6)/62 |

| Schaap et al. | 2016 | The Netherlands | Group ST twice a week (1.25 hr per session) | 78.5% met any of BPD, AvoPD, DepPD, PD NOS criteria; 21.5% had clinically maladaptive personality traits | An unstructured interview to assess DSM–IV clinical and personality pathology by experienced clinical psychologists and the questionnaires completed by the patients used in the study | No information | Inpatient | 65 | 65 | 26.9 (4.4) | 47 F + 18 M | 23/65 |

| Giesen-Bloo et al. | 2006 | The Netherlands | Individual ST twice a week (50 m per session) | BPD | SCID- I & II + the BPDSI | Supervisions and the STACS for BPD | Outpatient | 88 | 44 | 31.7 (8.9) (for the ST group) | 40 F + 4 M | 12/44 |

| Bamelis et al. | 2014 | The Netherlands | Individual ST (40 sessions in the first year and 10 booster sessions in the second year) | Primary PD diagnoses in ST group AvoPD, DepPD, OCPD, PPD, NPD | SCID II | Independent blinded raters scored randomly selected audiotapes on a series of 7-point Likert scales, indicating the amount of time specific therapeutic interventions were heard | Outpatient | 323 | 147 (145 included the analysis) | 37.6 (9.7) (for the ST group) | From 145 ST, 79 F + 66 M | 38/145 |

| Videler et al. | 2014 | The Netherlands | SCBT-g of 20 sessions (18 sessions of 90 min weekly and 2 follow up sessions of 90 min, one and two months after termination of treatment respectively) | PD or PD features + with/without mood disorders | The DSM-IV diagnosis was based on a multidisciplinary consensus diagnosis | No information | Outpatient | 42 | 42 | Completers M=68, SD=4.6; Dropout M=67, SD=5.3 | 31 F + 11 M | 11/42 |

ASPD: Antisocial personality disorder, AvoPD: Avoidant personality disorder, BPD: Borderline personality disorder, BPDSI: Borderline personality disorder severity index, BSI: Borderline Syndrome Index, DepPD: Dependent personality disorder, DIB-R: Diagnostic Interview for Borderline Personality Disorders-Revised, NPD: Narcissistic personality disorder, OCPD: Obsessive compulsive personality disorder, PPD: Paranoid personality disorder, PD: Personality disorder, SCID: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM, SCBT-g: Short-term group schema cognitive behavior therapy, SFT: Schema focused therapy, ST: Schema therapy, STACS: Schema therapy adherence and competence scale, STRS: Schema therapy rating scale, TAU: Treatment as usual.

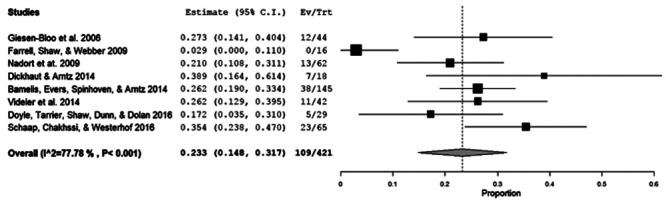

Among 421 participants who had individual and/or group ST, 109 participants dropped out. Across all the studies, the weighted mean dropout rate was 23.3%, 95% CI (14.8-31.7%). The analysis indicated a significant heterogeneity among the studies Q(7) = 31.5, p < .001, I2 >= 77.8. The forest plot is presented in Figure 1. A subgroup analysis conducted for therapy setting variable with applying a random effects model. The dropout rate of inpatient setting (27%, 95% CI: 9-44%, Q(1)=3.9 p=.048) was higher than the outpatient setting (22%, 95% CI: 12-32%, Q(5)=24.9, p<.001).

Figure 1.

Forest plot for dropout rates of schema therapy studies.

Discussion and Conclusions

The 23.3% weighted mean dropout rate of this study shows that almost one in four patients in ST treatment has the potential drop out. Although this dropout rate and its CI levels suggest that the ST-patient dropout rate may not significantly differ from patients in general psychotherapy (Swift and Greenberg, 2012) and BPD patients in some studies (see Barnicot et al., 2011), it is significantly lower when compared to the studies by Sharf (2008),McMurran et al. (2010) and Gamache et al. (2018). The dropout rates in these studies ranged between 35.3-40.8%. Although the current study’s dropout rate may look similar to Barnicot et al.’s (2011) results in patients with BPD (the completation rate was 71%, CI: 65-76%, for relatively long-term interventions), we can still speculate that the present study has more favorable dropout results in terms of rate and confidence interval.

Possible explanations for the differences between the current study and previous studies could be related to study sample characteristics, such as problem severity and age. Further, the included number of studies (eight) is relatively low. Additionally, some aspects of orientations might be significant moderators for dropout rates. For example, as suggested widely in the literature, therapeutic alliance is one of the most important and robust predictor of psychotherapy outcome as well as dropout (Horvath, Del Re, Flückiger, & Symonds, 2011; Sharf, 2008) and it is a vital element of ST (Weertman, 2012; Young et al., 2003). In Spinhoven, Giesen-Bloo, van Dyck, Kooiman, and Arntz's (2007) study, therapeutic alliance and other specific ST elements such as mode approach, interacted with each other to facilitate outcomes. In practice, a schema therapist might use mode approach that includes cognitive, behavioral, and experiential techniques, combining with limited reparenting and empathic confrontation to achieve better results via therapeutic relationship. To conclude, this lower mean dropout rate might be interpreted in favor of ST. Further studies could test this hypothesis by including therapeutic alliance as a moderating variable and compare ST with other specific treatment approaches. To be able to this, studies also should consider including and reporting results related to therapeutic alliance variable.

In the current study, the heterogeneity of the results may suggest that there could be moderator variables related to these dropout rates that need to be taken into consideration. Nevertheless, the number of the studies that included ST and personality disorders is limited and the information in them is not sufficient to conduct further analysis related to moderators of dropout rate. Accordingly, the studies could not manage to consider the possible moderator variables that were discussed in the literature such as SES, quality of therapeutic alliance, and therapists’ level of experience. This problem inevitably affects the current study. There were also problems relating to reporting the study design and results. It would be informative, and may thus provide a more comprehensive view, if researchers described the characteristics of the dropped-out groups. Only a few studies reported this information. Nevertheless, therapy setting analyzed as a categorical moderator variable. Similar to Swift and Greenberg’s (2012) results, outpatient setting had lower dropout rate than inpatient setting. Formal environment of inpatient settings may cause higher dropout rates by limiting clinicians to adapt ST practice to each patient’s unique characteristics and needs. However, the results should be evaluated cautiously because of the limited number of studies included. Further, this study did not aim at running a rigorous meta-analysis to obtain results for dropout rates in ST. Rather, the purpose of the study was to present a descriptive picture to understand ST’s position among other psychotherapy approaches in the context of personality-disorder treatment. In accordance with this, the inclusion and exclusion criteria were not robust.

Although the current study did not take into consideration the effectiveness of the treatments offered in the studies, the obtained information suggests that ST is an effective and promising treatment approach for the personality disorders in both individual and group formats. According to Lana and Fernandez-San Martin (2013), almost 40% of the BPD patients wishing to enter a specific treatment could not benefit from that treatment. Half never began treatment, while the other half did not respond to the treatment. Considering this as a starting point for attracting those who require treatment for personality disorders and for keeping patients in the treatment process and providing effective treatment, ST is a suitable option.

In spite of the promising results in this study in favor of ST, researchers and clinicians should also consider some limitations, such as the heterogeneity in the personality disorder diagnoses, the relatively small sample size, and the lack of a robust methodological design.

Funding Statement

Funding: none.

References

- Arntz A., Jacob G. (2013). Schema therapy in practice: An introductory guide to the schema mode approach. West Sussex, UK: Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Baekeland F., Lundwall L. (1975). Dropping out of treatment: A critical review. Psychological Bulletin, 82(5), 738-783. doi: 10.1037/h0077132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bamelis L.M., Evers S.M.A.A., Spinhoven P., Arntz A. (2014). Results of a multicenter randomized controlled trial of the clinical effectiveness of schema therapy for personality disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry, 171(3), 305-322. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.12040518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnicot K., Katsakou C., Marougka S., Priebe S. (2011). Treatment completion in psychotherapy for borderline personality disorder – a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 123(5), 327-338. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2010.01652.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickhaut V., Arntz An. (2014). Combined group and individual schema therapy for borderline personality disorder: A pilot study. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 45(2), 242-251. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2013.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diguer L., Barber J.P., Luborsky L. (1993). Three concomitants: Personality disorders, psychiatric severity, and outcome of dynamic psychotherapy of major depression. American Journal of Psychiatry, 150, 1246-1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon-Gordon K. L., Turner B. J., Chapman A. L. (2011). Psychotherapy for personality disorders. International Review of Psychiatry, 23(3), 282-302. doi: 10.3109/09540261.2011.586992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle M., Tarrier N., Shaw J., Dunn G., Dolan M. (2016). Exploratory trial of schema-focused therapy in a forensic personality disordered population. The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, 27(2), 232-247. doi: 10.1080/14789949.2015.1107119 [Google Scholar]

- Farrell J. M., Shaw I. A., Webber M. A. (2009). A schemafocused approach to group psychotherapy for outpatients with borderline personality disorder: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 40(2), 317-28. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2009.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankenburg F. R., Zanarini M. C. (2006). Personality disorders and medical comorbidity. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 19(4), 428-431. doi: 10.1097/01.yco.0000228766.33356.44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamache D., Savard C., Lemelin S., Cote A., Villeneuve E. (2018). Premature psychotherapy termination in an outpatient treatment program for personality disorders: A survival analysis. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 80, 14-23. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2017.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giesen-Bloo J., van Dyck R., Spinhoven P., van Tilburg W., Dirksen C., van Asselt T., ...Arntz A. (2006). Outpatient psychotherapy for borderline personality disorder: Randomized trial of schema-focused therapy vs transference-focused psychotherapy. Archives of General Psychiatry, 63(6), 649-658. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.6.649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath A.O., Del Re A.C., Flückiger C., Symonds D. (2011). Alliance in individual psychotherapy. Psychotherapy, 48(1), 9-16. doi: 10.1037/a0022186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IsHak W.W., Elbau I., Ismail A., Delaloye S., Ha K., Bolotaulo N.I., ...Wang C. (2013). Quality of Life in Borderline Personality Disorder. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 21(3), 138-150. doi: 10.1097/HRP.0b013e3182937116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lana F., Fernandez-San Martin M.I. (2013). To what extent are specific psychotherapies for borderline personality disorders efficacious? A systematic review of published randomized controlled trials. Actas Espanolas De Psiquiatria, 41(4), 242-252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krauskopf C.I., Baumoardner A., Mandracchia S. (1981). Return rate following intake revisited. Journal of Counselling Psychology, 28, 519-521. [Google Scholar]

- McMurran M., Huband N., Overton E. (2010). Non-completion of personality disorder treatments: A systematic review of correlates, consequences, and interventions. Clinical Psychology Reviews, 30(3), 277-287. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadort M., Arntz A., Smit J.H., Giesen-Bloo J., Eikelenboom M., Spinhoven P., ...van Dyck R. (2009). Implementation of outpatient schema therapy for borderline personality disorder with versus without crisis support by the therapist outside office hours: A randomized trial. Behavior Research and Therapy, 7(11), 961-973. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2009.07.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roos J., Werbart A. (2013). Therapist and relationship factors influencing dropout from individual psychotherapy: A literature review. Psychotherapy Research, 23(4), 394-418. doi: 10.1080/10503307.2013.775528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossberg J.L, Karterud S., Pedersen G., Friis S. (2008). Specific personality traits evoke different countertransference reactions: An empirical study. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 196(9), 702-708. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e318186de80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaap G., Chakhssi F., Westerhof G.J. (2016). Inpatient schema therapy for nonresponsive patient with personality pathology: Changes in symptomatic distress, schemas, schema modes, coping styles, experienced parenting styles, and mental well-being. Psychotherapy, 53(4), 402-412. doi: 10.1037/pst0000056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharf J. (2008). Psychotherapy dropout: A meta-analytic review of premature termination. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering, 68(9-B), 6336 [Google Scholar]

- Spinhoven P., Giesen-Bloo J., van Dyck R., Kooiman K., Arntz A. (2007). The therapeutic alliance in schema-focused therapy and transference- focused psychotherapy for borderline personality disorder. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology, 75(1), 104-115. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.1.104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swift J.K., Callahan J.L., Vollmer B.M. (2011). Preferences. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 67, 155-165. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swift J.K., Greenberg R.P. (2012). Premature discontinuation in adult psychotherapy: A meta-analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 80(4), 547-559. doi: 10.1037/a0028226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torgersen S. (2005). Epidemiology. Oldham J.M., Skodol A.E., Bender D.S. (Eds.), The American Psychiatric Publishing textbook of personality disorders (pp. 129-141). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Videler A.C., Rossi G., Schoevaars M., van der Feltz-Cornelis C. M., van Alphen P.J. (2014). Effects of schema group therapy in older outpatients: A proof of concept study. International Psychogeriatrics, 26(19), 1709-1717. doi: 10.1017/S1041610214001264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace B., Dahabreh I., Trikalinos T., Lau J., Trow P., Schmid C. (2012). Closing the Gap between Methodologists and End-Users: R as a Computational Back-End. Journal of Statistical Software, 49(5), 1-15. doi: 10.18637/jss.v049.i05 [Google Scholar]

- Weertman A. (2012). The use of experiential techniques for diagnostics. Vreeswijk M. Van, Iroersen J., Nadort M. (Eds.), The Wiley-Blackwell handbook of schema therapy: Theory, research and practice (pp.101-109). West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Wierzbicki M., Pekarik G. (1993). A meta-analysis of psychotherapy dropout. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 24(2), 190-195. doi: 10.1037/0735-7028.24.2.190 [Google Scholar]

- Young J.E. (1990). Cognitive therapy for personality disorders. Sarasota, FL: Professional Resources Press. [Google Scholar]

- Young J.E., Klosko J.S., Weishaar M.E. (2003). Schema therapy: A practitioner’s guide. New York, NY: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman M., Rothschild L., Chelminski I. (2005). The prevalence of DSM-IV personality disorders in psychiatric outpatients. American Journal of Psychiatry, 162, 1911-1918. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.10.1911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]