Abstract

Congenital Disorders of Glycosylation (CDG) are scarcely reported from Latin America. We here report on a Mexican mestizo with a multi-systemic syndrome including neurological involvement and a type I transferrin (Tf) isoelectric focusing (IEF) pattern. Clinical exome sequencing (CES) showed known compound missense variants in PMM2 c.422G > A (p.R141H) and c.395 T > C (p.I132T), coding for the phosphomanomutase 2 (PMM2). PMM2 catalyzes the conversion of mannose-6-P to mannose-1-P required for the synthesis of GDP-Man and Dol-P-Man, donor substrates for glycosylation reactions. This is the third reported Mexican CDG patient and the first with PMM2-CDG. PMM2 has been recently identified as one of the top 10 genes carrying pathogenic variants in a Mexican population cohort.

Keywords: CDG, Glycosylation, Metabolism, PMM2

1. Introduction

Congenital Disorders of Glycosylation (CDG) are a heterogenous group of nearly 140 genetic diseases due to defective glycoprotein and glycolipid glycan synthesis and attachment [1]. Glycoprotein glycosylation defects can be divided in N-glycosylation defects and O-glycosylation defects [2]. Screening for N-glycosylation defects mostly occurs by serum transferrin (Tf) isoelectric focusing (IEF). Defects in glycan assembly in the cytosol and ER show a type I pattern (CDG—I) while defects in glycan remodeling in the Golgi show a type 2 pattern (CDG-II) [2]. The most frequent N-glycosylation disorder is PMM2-CDG, a CDG-I [2]. We here report on the first Mexican mestizo with PMM2-CDG.

2. Clinical report

This 7-year-old boy from Poza Rica, Veracruz (México), was born to unrelated parents after a normal full-term pregnancy. Birth weight was 2700 g and length of 50 cm, Apgar score was 5/8. He presented with breathing difficulty in the first hours of life, remaining hospitalized for four days and was managed with an O2 helmet. Mild jaundice did not require treatment. Since birth, he presented generalized hypotonia and feeding difficulties. There were two seizures at four months.

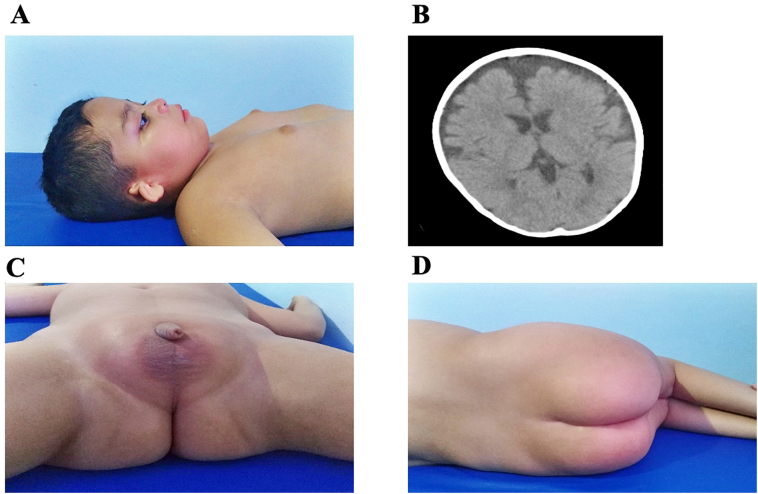

Since the age of three he suffered from generalized seizures, learning difficulties and dependence on several activities of daily life, with psychomotor and developmental delay, inability to walk and hearing loss. No ataxia or cerebellar syndrome was observed. Dysmorphic features included bushy eyebrows and eyelashes, convergent strabismus, slightly wide nasal bridge, normal lips, bilateral microtia with atresia of the external auditory canal and pectum excavatum (Fig. 1A). Additionally, gluteal and pubic fat deposits were observed (Fig. 1C-D) as were dental caries. Mammary glands were enlarged without galactorrhea, hyperprolactinemia was detected (42 ng/mL); normal range extremities did not present malformations, but decreased strength, slightly increased reflexes, low muscular tone and discrete distal laxity were observed with contractures at the level of the hips, knees and ankles. Normal percentiles of height, weight and head circumference. The ophthalmological analysis showed retinal pigment epithelium dystrophy. The EEG showed generalized paroxysmal epileptiform crises with predominantly left frontotemporal epilepsy. Brain CT revealed significant generalized subcortical atrophy, an enlarged fourth ventricle and no cerebellar abnormalities (Fig. 1B). Karyotype was normal 46, XY.

Fig. 1.

A, microtia (bilateral), pectus excavatum and enlargement of mammary glands. B, Brain CT showed frontotemporal atrophy with a predominance of the left side. C and D, Abnormal accumulation of pubic periscrotal and gluteal fat deposits.

3. Materials and methods

3.1. Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from both parents to perform skin biopsy, fibroblast cultures and all required research to obtain a molecular diagnosis, and to publish other data on the patient.

3.2. Transferrin isoelectric focusing (IEF)

Serum from the patient (100 μL) was iron saturated at room temperature for 1 h with 5 μL of 0.5 M NaHCO3 and 5 μL of 20 mM FeCl3. One microliter of 10-fold-diluted serum was spotted on polyacrylamide gels (T = 5%, C = 3%) containing 5.7% ampholytes (pH 5–7). After electrophoresis, the gel was covered with 100 μL of rabit anti-transferrin serum (made in house) for 30 min at 4 °C. The gel was washed overnight with physiological saline, fixed, stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250, destained, dried, and photographed.

3.3. Cell culture

From a skin biopsy obtained from the patient a primary culture of fibroblasts was obtained in D-MEM / F-12 medium (Gibco® by life technologies ™) supplemented with 20% Bovine Fetal Serum (FBS Gibco® by life technologies ™) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin antibiotic. Fibroblast cultures were maintained at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. Fibroblasts were further processed to obtain genetic material.

3.4. Clinical exome sequencing (CES)

Genomic DNA (gDNA) was extracted from fibroblasts using TRIzol reagent (Life Technologies, Rockville, MD, USA). CES sequencing was performed using the sequencing reagents provided in the Clinical Exome sequencing panel kit, version 2 (Sophia Genetics SA, Saint Sulpice, Switzerland). Library preparation and sequencing were performed according to the manufacturer's protocol on MiSeq Instrument (illumina San Diego, CA). The sequencing data was analyzed and variants were annotated with the Sophia DDM® software version 5.7.2.1 (Sophia Genetics SA, Saint Sulpice, Switzerland). A bioinformatic filter was constructed including all the genes previously reported to be related with CDG.

3.5. Sanger sequencing

The cDNA-based polymerase chain reaction (PCR) product corresponding to the coding sequence of PMM2 was obtained using forward primer PMM2s 5′-TGCCAACGTGTCTTGTAAGG-3′ and reverse primer PMM2as 5′-GGAAGTTTCTGGCACTGGAG-3′ [3]. The PCR product corresponding to exon 5 of PMM2 was amplified from gDNA using forward primer PMM2-E5F 5′-GAAACATTGACCACACTAGCC-3′ and reverse primer PMM2-E5R 5′-GTGTTGGGATTACAGGCATG-3′ [4]. Direct sequencing of PCR products was carried out using an ABI Prism 3130xl autoanalyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA).

4. Results

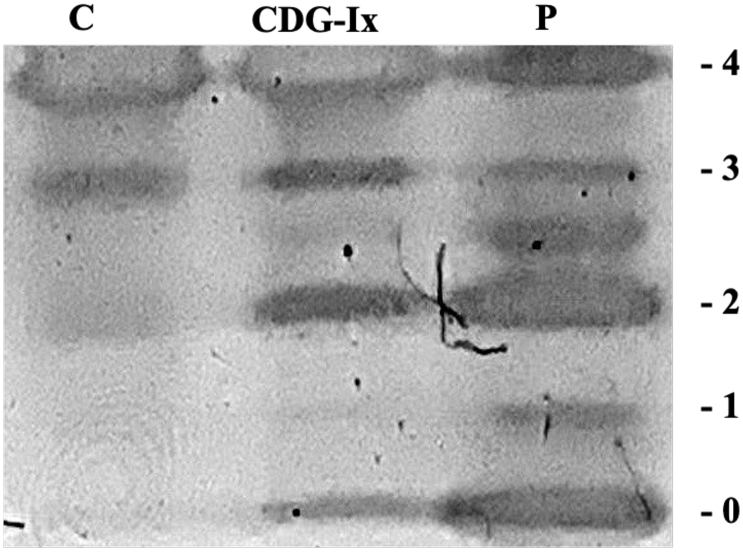

Serum Tf IEF showed a type I pattern (decreased tetrasialo Tf and increased di- and asialo Tf) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Serum transferrin (Tf) isoelectric focusing (IEF) showing an abnormal type I profile. C, control sample; CDG-I control sample; P, patient sample. Numbers in the edge correspond to the number of sialic acids in the transferrin isoforms.

The next step was CES showing two known variants in PMM2. Both are missense point mutations in exon 5 (c.422G > A (p.R141H), and c.395 T > C (p.I132T)). Sanger sequencing of the cDNA PCR of the PMM2 coding sequence of the patient confirmed these mutations and no others were found. Sanger sequencing of parental gDNA showed the c.422G > A (p.R141H) was paternally inherited, while the c.395 T > C (p.I132T) mutation was maternally inherited (see Fig. 3A-B).

Fig. 3.

Sanger sequencing chromatograms showing PMM2 mutations. A, patient and mother showing the heterozygous mutation in c.395 T > C (p.I132T) in gDNA. B, patient and father showing the heterozygous mutation c.422G > A (p.R141H). Control = healthy individual.

5. Discussion

Only two Mexican CDG patients have been reported; both showed ATP6V0A2-CDG [5]. Here we report the first Mexican mestizo with PMM2-CDG (OMIM 212065). Two known variants were involved: c.422G > A (p.R141H) and c.395C > T (p.I132T). The compound heterozygosity for the p.R141H / p.I132T mutations has been reported to decrease the enzyme activity of PMM2 to 23–41% [6]. Our patient showed the typical PMM2-CDG phenotype except that there were no inverted nipples and no cerebellar hyopoplasia. The latter symptoms are absent in a small minority of patients with this CDG.

A number of missense mutations higher than expected for a gene associated with a recessive disease is observed in PMM2 [7]. According to the professional version of Human Gene Mutation Database, 127 disease-causing mutations have been described in PMM2 (as of July 2020, professional version 2020.2). Most of them (100) are missense variants (78.74%), therefore compound heterozygotes for two different missense pathogenic variants are frequently found in these patients.

Eleven PMM2-CDG individuals carrying the p.R141H / p.I132T heterozygous compound combination have been reported in the literature, but none from Latino ethnic origin [4,6,[8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13]]. The p.R141H mutation found in this individual has been found in all ethnic groups with the lower frequency ranging in East Asia (1/7536) and the higher in Europe (non-Finnish) (1 in 121) (from gnomAD ExomesVersion: 2.1.1, as of July 2020). It has also been reported in about 1/70 Northern Europeans, implying a selective advantage of the carrier state [14]. Interestingly, the homozygosity of the p.R141H mutation has not been reported as it is probably lethal [4,15].

PMM2-CDG as most CDG is probably underdiagnosed, reason why it is important to report cases to increase clinical awareness and promote laboratory diagnosis in every country, particularly in the developing world where CDG have been scarcely reported. This not only includes diagnosis in patients, but also carrier screening in couples with infertility or miscarriage issues. In Latin America, few PMM2-CDG cases have been reported, mainly in Argentina and Brazil [16,17].

Increased awareness of CDG and particularly of PMM2-CDG should be raised in view of the significant prevalence of pathogenic variants knows for this gene and evidenced in a cohort of 805 Mexican individuals [18]. The most common mutation found in this group was (c.422G > A, p.R141H), followed by (c.470 T > C, p.F157S), (c.255+ 1G > A), (c.442G > A, p.D148N) and (c.367C > T, p.R123X) (C. Hernández-Nieto, personal communication).

Management of PMM2-CDG requires a multidisciplinary approach and international management guidelines have been published [19]. No curative treatment has been developed. A recent trial with acetazolamide, a long-known diuretic, showed a significant improvement of the motor cerebellar syndrome in PMM2-CDG [20]. This is a nice example of drug repositioning.

6. Summary

In conclusion, exome sequencing is an increasingly important tool for the diagnosis of CDG, also in developing countries.

Credit author statement

González-Domínguez CA: molecular biology, methodology and original draft preparation Raya-Trigueros A: clinical diagnosis Manrique-Hernández S: skin biopsy and fibroblast culture González-Jaimes A and Salinas-Marín R: Transferrin IEF Molina-Garay C, Carrillo-Sánchez K, Flores-Lagunes LL, Jiménez-Olivares M, Dehesa-Caballero C, Alaez-Versón C: Exome sequencing and database analysis. Martínez-Duncker I: conceptualization, writing, reviewing and editing.

Acknowledgements

We thank Hudson Freeze and Bobby Ng for their important comments in improving this work and their support in training personnel in Tf IEF. We thank Carlos Hernández-Nieto for information on pathogenic variants. IMD and CAGD were supported by grants 293399 Red Temática Glicociencia en Salud – CONACyT and the Sociedad Latinoamericana de Glicobiología, A.C. CAGD is recipient of scholarship 957250 from CONACYT.

References

- 1.Varki A., Cummings R.D., Esko J.D., Stanley P., Hart G.W., Aebi M., Seeberger P.H. Vol. 823. 2017. Essentials of glycobiology, third edition. – Cold Spring Harbor (NY): Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chang I.J., He M., Lam C.T. Congenital disorders of glycosylation. Ann. Transl. Med. 2018;6(24):477. doi: 10.21037/atm.2018.10.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schollen E., Keldermans L., Foulquier F., Briones P., Chabas A., Sánchez-Valverde F.…Matthijs G. Characterization of two unusual truncating PMM2 mutations in two CDG-Ia patients. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2007;90(4):408–413. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matthijs G., Schollen E., Van Schaftingen E., Cassiman J.J., Jaeken J. Lack of homozygotes for the most frequent disease allele in carbohydrate-deficient glycoprotein syndrome type 1A. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1998;62(3):542–550. doi: 10.1086/301763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bahena-Bahena D., López-Valdez J., Raymond K., Salinas-Marín R., Ortega-García A., Ng B.G.…Martínez-Duncker I. ATP6V0A2 mutations present in two Mexican mestizo children with an autosomal recessive cutis laxa syndrome type IIA. Mol. Genet. Metab. Rep. 2014;1(1):203–212. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgmr.2014.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vuillaumier-Barrot S., Seta N., Hetet G., Barnier A., Dupré T., Cuer M.…Grandchamp B. Identification of four novel PMM2 mutations in congenital disorders of glycosylation (CDG) Ia French patients. J. Med. Genet. 2000;37(8):579–580. doi: 10.1136/jmg.37.8.579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Citro V., Cimmaruta C., Monticelli M., Riccio G., Hay Mele B., Cubellis M.V., Andreotti G. The analysis of variants in the general population reveals that PMM2 is extremely tolerant to Missense mutations and that diagnosis of PMM2-CDG can benefit from the identification of modifiers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018;19(8):2218. doi: 10.3390/ijms1908221813. Van Schaftingen, E., & Jaeken, J. (1995). Phosphomannomutase deficiency is a cause of carbohydrate-deficient glycoprotein syndrome type I. FEBS Letters, 377(3), 318–320. 10.1016/0014-5793(95)01357-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Le Bizec C., Vuillaumier-Barrot S., Barnier A., Dupré T., Durand G., Seta N. A new insight into PMM2 mutations in the French population. Hum. Mutat. 2005;25(5):504–505. doi: 10.1002/humu.9336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barone R., Carrozzi M., Parini R., Battini R., Martinelli D., Elia M.…Fiumara A. A nationwide survey of PMM2-CDG in Italy: high frequency of a mild neurological variant associated with the L32R mutation. J. Neurol. 2015;262(1):154–164. doi: 10.1007/s00415-014-7549-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Lonlay P., Seta N., Barrot S. A broad spectrum of clinical presentations in congenital disorders of glycosylation I: a series of 26 cases. J. Med. Genet. 2001;38(1):14–19. doi: 10.1136/jmg.38.1.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Monin M.L., Mignot C., De Lonlay P., Héron B., Masurel A., Mathieu-Dramard M., Lenaerts C., Thauvin C., Gérard M., Roze E., Jacquette A., Charles P., de Baracé C., Drouin-Garraud V., Khau Van Kien P., Cormier-Daire V., Mayer M., Ogier H., Brice A., Seta N.…Héron D. 29 French adult patients with PMM2-congenital disorder of glycosylation: outcome of the classical pediatric phenotype and depiction of a late-onset phenotype. Orphanet journal of rare diseases. 2014;9:207. doi: 10.1186/s13023-014-0207-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grünewald S., Schollen E., Van Schaftingen E., Jaeken J., Matthijs G. High residual activity of PMM2 in patients' fibroblasts: possible pitfall in the diagnosis of CDG-Ia (phosphomannomutase deficiency) Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2001;68(2):347–354. doi: 10.1086/318199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yıldız Y., Arslan M., Çelik G. Genotypes and estimated prevalence of phosphomannomutase 2 deficiency in Turkey differ significantly from those in Europe. Am J Med Genet Part A. 2020:705–712. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.61488. 182A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Freeze H.H., Westphal V. Balancing N-linked glycosylation to avoid disease. Biochimie. 2001;83(8):791–799. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(01)01292-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carchon H., Van Schaftingen E., Matthijs G., Jaeken J. Carbohydrate-deficient glycoprotein syndrome type IA (phosphomannomutase-deficiency) Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. basis Dis. 1999;1455(2–3):155–165. doi: 10.1016/S0925-4439(99)00073-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Magalhães A.P.P.S., Burin M.G., Souza C.F.M. Transferrin isoelectric focusing for the investigation of congenital disorders of glycosylation: analysis of a ten-year experience in a Brazilian center [published online ahead of print, 2019 Oct 31] J. Pediatr. 2019 doi: 10.1016/j.jped.2019.05.008. S0021-7557(19) 30617–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Asteggiano C.G., Papazoglu M., Bistué Millón M.B. Ten years of screening for congenital disorders of glycosylation in Argentina: case studies and pitfalls. Pediatr. Res. 2018;84(6):837–841. doi: 10.1038/s41390-018-0206-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hernandez-Nieto C., Alkon-Meadows T., Lee J., Cacchione T., Iyune-Cojab E., Garza-Galvan M.…Sandler B. Expanded carrier screening for preconception reproductive risk assessment: prevalence of carrier status in a Mexican population. Prenat. Diagn. 2020;40(5):635–643. doi: 10.1002/pd.5656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Altassan R., Péanne R., Jaeken J. International clinical guidelines for the management of phosphomannomutase 2-congenital disorders of glycosylation: diagnosis, treatment and follow up [published correction appears in J. Inherit. Metab. Dis.2019 May;42(3):577] J Inherit Metab Dis. 2019;42(1):5–28. doi: 10.1002/jimd.12024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martínez-Monseny A.F., Bolasell M., Callejón-Póo L., Cuadras D., Freniche V., Itzep D.C.…Conde-Lorenzo N. AZATAX: acetazolamide safety and efficacy in cerebellar syndrome in PMM2 congenital disorder of glycosylation (PMM2-CDG) Ann. Neurol. 2019;85(5):740–751. doi: 10.1002/ana.25457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]