Abstract

Many open and arthroscopic techniques have been described to treat posterior glenohumeral instability. Multifactorial features of posterior shoulder instability pathoanatomy and varied patient characteristics have challenged the understanding of this condition and have led to dissimilar results, without a strong consensus for the most adequate technique to treat it. We describe an arthroscopic anatomical metal-free posterior glenoid reconstruction technique, using a tricortical iliac crest allograft with 2 ultra-high strength sutures (FiberTape Cerclage System; Arthrex, Naples, FL) with concomitant posterior capsulolabral complex reconstruction procedure.

Posterior shoulder instability is an uncommon condition, accounting for 2% to 10% of all glenohumeral dislocations.1 However, in some demographics, such as military and sporting groups, this may be very much more frequent.1, 2, 3

Unlike anterior shoulder instability, some biomechanical features of posterior glenohumeral instability, such as a thinner posterior capsuloligamentous complex, increased glenoid retroversion, or glenoid hypoplasia, among others, have made diagnosis, classification, and treatment very difficult.4,5 In addition, because of the wide spectrum of clinical presentations and the voluntary or involuntary nature of this pathology, no consensus has been established on which surgical technique should be used; this has led to high failure rates.6

Moreover, its classification takes several variables into account. With regards to biomechanics, on one hand, structural and functional posterior instability must be distinguished, and on the other hand, its controllability (controllable or uncontrollable instability) also must be considered. Caution must be taken with voluntary and intentional dislocators, in whom all treatment procedures have poor results.7,8

Many surgical procedures have been developed and refined to treat this condition in recent decades.9,10 Nowadays, surgical treatment is focused on posterior soft-tissue lesions with capsulolabral reconstructions and, in cases of subsequent glenoid bone deficit (reverse bony Bankart, dysplasia, or erosion), the use of bone-grafting techniques. Even in the absence of glenoid bone defect, the use of bone blocks has been published by several authors.11 Arthroscopic techniques have gained popularity over open techniques due to the greater morbidity in the surgical approach, poor cosmetic results, difficulty of visualizing the labrum completely, the possibility of managing concomitant pathologies, partial deltoid muscle deficiency, and improvements in instrumentation and implant technology.5,11,12 In addition, to avoid complications related to screw position and length, Boileau et al.13 used suture anchors for bone block fixation and capsulolabral repair. However, bone resorption and residual pain are considered to be closely related to the absence of a sufficiently stable graft fixation and the presence of metal implants.14,15

In this Technical Note, we describe an arthroscopic anatomical metal-free bone block fixation technique with capsulolabral reconstruction for posterior shoulder instability. A similar technique has been recently published by our research group to treat anterior shoulder instability with glenoid bone loss.16 The advantages, disadvantages, and possible complications of this technique are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Advantages and Disadvantages of the Technique

Advantages

Disadvantages

|

Surgical Technique (With Video Illustration)

The surgical technique is demonstrated in Video 1.

Preoperative Assessment

All patients with multiple posterior dislocations or subluxation events are studied with 3-dimensional computed tomography with humeral head suppression, to assess posterior glenoid bone loss, glenoid retroversion and glenoid hypoplasia. Patient characteristics are also described (Table 2). This surgical technique is indicated in symptomatic structural posterior instability, symptomatic functional involuntary positional instability, as well as symptomatic functional voluntary demonstrable instability.

Table 2.

Evaluation of the Patient With Posterior Shoulder Instability

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

AP, anteroposterior; CT, computed tomography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; WOSI, Western Ontario Shoulder Instability Index.

Patient Position and Arthroscopic Diagnosis

The patient is positioned in the lateral decubitus position with 30° of posterior obliquity to ensure that the glenoid is parallel to the floor and posterior sacral, and interscapular stops are placed. The arm is placed in a traction foam sleeve (3-point Shoulder Distraction System; Arthrex, Naples, FL) to use 2 points of traction. The bony structures and arthroscopic portals are drawn.

Initial arthroscopic diagnosis is made through the standard posterior portal, looking for concomitant pathologies (SLAP lesions, anterior and posterior labrum lesions, rotator cuff tears, etc.). However, an anterosuperior portal is required to obtain optimal visualization of posterior structures, to assess glenoid bone loss and to accurately evaluate the posterior glenoid edge in preparation for the allograft fixation (Fig 1A).

Fig 1.

Right shoulder, lateral decubitus position. Arthroscopic view, anterosuperior portal. (A) Posteroinferior labral lesion as seen from the anterosuperior portal. (B) Release of the posterior capsulolabral complex and debridement of the posterior glenoid rim. (C, capsule; G, glenoid; HH, humeral head; L, posterior labrum.)

Glenoid Preparation

An anterior portal is placed through the rotator interval and an 8.25-mm cannula is placed (Arthrex). Camera vision is switched to an anterosuperior portal over and posterior to the long head of the biceps tendon insertion. Then, a new accessory posterior portal of 1.5 cm in diameter is made for drill guide and allograft insertion.

We start by debriding and releasing the posteroinferior capsulolabral tissue from 11 o’clock to 6 o’clock and the posterior glenoid bone abrasion to improve biological integration of the graft while looking through the anterosuperior portal (Fig 1B).

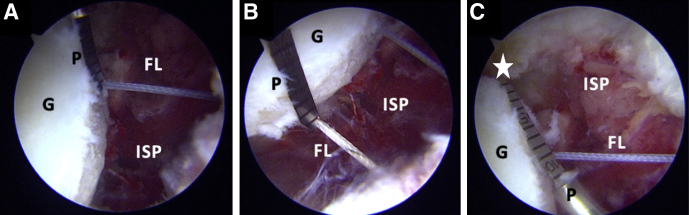

Through a posterolateral accessory portal, we place a polydioxanone suture (PDS) through the capsulolabral complex using a SutureLasso (Arthrex, Naples, FL), which facilitates suture manipulation and posterior glenoid defect visualization (Fig 2 A-C).

Fig 2.

Right shoulder, lateral decubitus position. Arthroscopic view, anterosuperior portal. (A) Posterior capsulolabral complex retraction with PDS. (B) Visualization of the infraspinatus muscle fibers. (C) Lateral decubitus, right shoulder, extra-articular view of the PDS suture fixation. (AP, accessory posterior portal; C, capsule; G, glenoid; HH, humeral head; P, posterior portal; PDS, polydioxanone suture; SSC, subscapularis.)

In situ sizing of the posterior glenoid is performed. An arthroscopic measurement probe (Arthroscopic Measurement probe, 220 mm, 60°; Arthrex) is used from the posterior portal to measure the superoinferior length of the posterior glenoid (Fig 3). We mark the glenoid edge at a margin distance of 10 mm proximal to the lower point of the longitudinal aspect of the glenoid previously measured, to determine precisely the optimal position where the posterior drill guide should be placed.

Fig 3.

Right shoulder, lateral decubitus position, Arthroscopic view, anterosuperior portal. Intraoperative measurement of the superoinferior length of the posterior glenoid. White Star: arthroscopic measurement probe, 220 mm, 60°; Arthrex). (C, capsule; G, glenoid; HH, humeral head; ISP, infraspinatus muscle fibers; P, posterior portal; PDS, polydioxanone suture; SSC, subscapularis.)

Posterior Glenoid Drilling

A specific arthroscopic posterior guide (Arthrex) is introduced through the accessory posterior portal. The anterior aspect of the guide is placed parallel to the glenoid, just above the previous glenoid mark, in the center of the debrided posterior glenoid. The drill guide-holes should be in contact with the posterior edge of the glenoid. The guide permits drilling of 2 holes with 2.4-mm cannulated drills through the glenoid 10mm apart. We measure the distance from the distal tunnel to inferior glenoid border and the distance from the articular surface to the tunnels. We must keep a 10-mm margin from the lower edge of the posterior glenoid (Fig 4 A and B). The central cores of the cannulated drills are extracted and 2 nitinol wires with loops—one for each tunnel—are passed, one with the loop facing posteriorly and the other anteriorly. The drills and drill guide are then removed (Fig 5 A-C).

Fig 4.

Right shoulder, lateral decubitus position. Arthroscopic view, anterosuperior portal. (A) Posterior placement of the drilling guide. (B) Lateral decubitus, extra-articular view of the posterior guide insertion. (G, posterior glenoid; P, posterior view of the right shoulder; PG, posterior drilling guide.)

Fig 5.

Right shoulder, lateral decubitus position. Arthroscopic view, anterosuperior portal. (A-B) Measure of the distance between articular margin and graft holes. (C) Measure of the distance between inferior graft hole and the distal margin of the glenoid. White star: Distal margin of the glenoid. (FL, FiberLink; G, glenoid; ISP, infraspinatus muscle fibers; P, arthroscopic probe.)

Allograft Preparation

Cuts with an oscillating saw are made according to the dimensions previously measured from the posterior edge of the glenoid. The graft’s width is determined by the iliac crest (usually 10 mm to 12 mm). The curved edge that best fits the glenoid rim is selected. Graft dimensions usually are 30 mm × 10 mm × 10 mm. The graft is marked on its cancellous bone face. The tricortical autograft tunnels are made with a 2.4mm drill from the cancellous to the cortical side. The lower tunnel is made first, 10mm from the proposed lower rim, after which the higher tunnel is made 10mm superior to the first one, imitating the dimensions of the glenoid drill guide (Fig 6 A-C).

Fig 6.

Iliac crest allograft preparation. (A) Allograft measurement and (B) cutting. (C) Allograft orientation. Black star: cortical side of the allograft. (G, glenoid face of the allograft; I, inferior aspect of the allograft; ICA, iliac crest allograft; IT, inferior tunnel; S, superior aspect of the allograft; ST, superior tunnel.)

Allograft Accommodation and Fixation

To facilitate suture passage through glenoid drilled holes, nitinol wires are replaced with 2 different looped sutures (FiberLink/TigerLink sutures; Arthrex) (Fig 7 A and B). One suture should have its loop on the posterior side and its free end on the anterior side. The other suture should have them in the opposite direction. Digital dilation of the posteroinferior portal is then performed for graft passage. Using the FiberLink posterior loop, 2 Ultra-High Strength Suture Tapes (FiberTape Cerclage System; Arthrex) are first passed from the cortical side to the cancellous side of the graft, then from the posterior to the anterior side of the glenoid and are subsequently retrieved through the anterior portal. The sutures are then inserted from the anterior side to the posterior side with the inferior FiberLink loop through the glenoid and passed through the inferior drill hole of the graft (Fig 8 A-F).

Fig 7.

Right shoulder, lateral decubitus position. Arthroscopic view, anterosuperior portal. (A) Nitinol loop retrieved from the cannulated drill through the anterior portal. (Black arrow pointing to the inferior nitinol loop). (B) Nitinol wires are replaced with 2 different-colored FiberLink sutures. (AL, anterior labrum; C, posterior capsule; FL, FiberLinks; G, posterior glenoid; HH, humeral head; SSC, subscapular.)

Fig 8.

Right shoulder, lateral decubitus position. Accommodation of the allograft. (A) Two bands of FiberTape cerclage sutures are passed through the superior allograft hole. (B-C) The FiberTapes are connected with posterior loop of the superior FiberLink and retrieved from the posterior to anterior side of the glenoid. (D-F) The FiberTape sutures are then retrieved from the anterior glenoid hole to the posterior end pulling the inferior FiberLink loop through the glenoid and passing through the inferior drill hole of the graft. (B, D, E) Arthroscopic view from the anterosuperior portal. (F) Intra-articular view. (A, cortical side of the allograft; AC, anterior capsule; FL, FiberLink; FT, FiberTape; G, glenoid; P, posteromedial portal).

The bone graft is inserted manually into the glenohumeral joint (Fig 9 A and B). Once the graft is inserted and well positioned, the FiberTape sutures are interconnected to create a continuous loop. The tails of the FiberTape sutures are loaded through the pre-tied racking hitch knot of the TigerTape, and vice versa. This allows the application of alternating traction on each suture limb to reduce the knots on the graft and achieve symmetrical tensioning of the construct (Fig 10 A and D).

Fig 9.

Insertion of the allograft into the joint. (A) Lateral decubitus, right shoulder. Extra-articular view of the construct previous insertion. (B) Arthroscopic view from anterosuperior portal. Insertion of allograft through posteromedial portal. (A, allograft; AP, accessory posterior portal; C, posterior capsule; FT, FiberTapes; G, glenoid; P, posterior portal.)

Fig 10.

Right shoulder, lateral decubitus position. (A-D) Extra-articular view of the FiberTape interconnection. (AP, accessory posterior portal; FTC, FiberTape cerclage; TTC, TigerTape cerclage.)

Once the stability of the graft is verified, the 2 knots are tensioned, one after the other, applying a mechanical force equal to 80N with a tensioner (FiberTape Cerclage Tensioner; Arthrex). Next, at least 3 alternating half-hitch knots are made for each strand. A strong and stable fixation is achieved (Fig 11 A-C).

Fig 11.

Fixation of the allograft bone block, right shoulder, lateral decubitus position. (A) Arthroscopic view from the anterosuperior portal and (B) extra-articular posterior view of the fixation of the allograft with the tensioner. (C) Arthroscopic view from the anterosuperior portal of the bone block fixation after knot tying. (A, allograft; CLC, capsulolabral complex; G, glenoid; K, knots; T, tensioner.)

Capsulolabral Repair

Finally, the posterior PDS suture is released from the capsulolabral complex, and 3 to 4 “all suture” FiberTak suture anchors (Arthrex) are placed at the native glenoid rim and introduced through our posterior percutaneous PDS suture traction portal. Other anchors are also placed inferiorly at 7 o’clock and 8 o’clock and superiorly at 10 o’clock and 11 o’clock, reattaching the capsulolabral complex and making the graft extra-articular (Fig 12 A and B).

Fig 12.

(A-B) Right shoulder, lateral decubitus position, arthroscopic view from the anterosuperior portal. Capsulolabral complex reconstruction to its native glenoid with FiberTak knotless 1.8 implants (Arthrex) (A, allograft; CLC, capsulolabral complex, G, glenoid; HH, humeral head; I, implant from the posterior percutaneous polydioxanone suture traction portal.)

Rehabilitation

Daily cryotherapy for 10 minutes of every 2 hours to manage postoperative pain is recommended. The shoulder is immobilized with a sling at 15° of abduction and in a neutral rotation position for 3 weeks, while simultaneously encouraging the patient to perform flexion of the elbow and the wrist joint starting from the first day after the surgical intervention. Pendulum exercises and passive assisted arm flexion, as well as isometric strengthening of the deltoid and the scapular muscles, are indicated.

Active-assisted exercises are indicated in the following weeks. At 3 to 4 weeks postoperatively, the patient can remove the sling and begin full passive and active range of motion movement. Capsular stretching and strengthening of the rotator cuff, along with deltoid exercises, with an elastic band can be practiced starting 5 to 6 weeks postoperatively. When a full range of motion is attained and muscular strength is equivalent to at least 90% of the muscular strength of the contralateral side, the patient is allowed to return to sports practice and activities, which is generally occurs at round 4to 5 months postoperatively.

Postoperative radiograph controls are done early, at 3 and 6 weeks of follow up, with anteroposterior and outlet views. The position of the bone block is assessed with an early postoperative computed tomography scan and later at 1 year of follow-up to assess the grade of remodeling.

Some tips and pitfalls of the actual technique are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Tips and Pitfalls of the Technique

Tips

Pitfalls

Limitations of the Technique

|

Discussion

It is a difficult task to characterize the posterior shoulder instability patient, even for the most experienced surgeons. While anterior instability mechanisms are usually well identified by the patient, posterior shoulder instability patients frequently have unspecific and vague symptoms.17,18

To guide the treatment of posterior instability, Moroder and Scheibel19 developed a classification based on the different pathomechanical types of instability—the ABC Classification. First, Group A classifies the first event of posterior instability into 2 types: A1, a subluxation event and A2, a dislocation event. Conservative treatment is generally possible for this group if no critical bony or soft tissue defect is discovered. In Group B (Dynamic Instability), posterior instability is associated with: B1 (Functional Dynamic Instability), Rotator cuff and Periscapular Muscle imbalances or B2 (Structural dynamic instability), which can be associated with structural damage (Bone loss, posterior Bankart lesions or critical reverse Hill–Sachs lesions). Finally, Group C (Static Instability), is divided into 2 subgroups. Subgroup C1, (Constitutional Static posterior Instability) for patients with constitutional force imbalances and scapular malpositioning that leads to eccentric contact of the joint and eventually progressive eccentric posterior glenoid wear and C2 (Acquired Static Posterior instability), with permanent subluxation or dislocation of the humeral head.

Recently, the same research group20 reinforced the concept of functional shoulder instabilities as pathologic muscle activation patterns, emphasizing 2 types of patients, ones presenting with an unwanted dislocation during movement (involuntary positional instability) and others with the ability to deliberately dislocate the shoulder (voluntary instability). Further distinction must be made in patients with voluntary instability who have the desire to dislocate their shoulder because of psychological or secondary gain issues (volitional instability) and patients who can deliberately dislocate their shoulders but have no actual desire to do so (demonstrable instability). In this recent study, a classification of functional shoulder instability was proposed based on the pathomechanism (positional and non-positional) and controllability (controllable and noncontrollable).

In addition, several authors have been able to identify specific risk factors in posterior shoulder instability, such as glenoid retroversion, rotator cuff and periscapular muscle imbalances, and glenoid hypoplasia.5,21,22

It is likely that the complexity of this pathology and its several edges have led to a large number of possible treatments; however, no unified criteria regarding clinical features, imaging nor arthroscopic findings, have led the way to a particular surgical treatment over another. Several reviews demonstrated good results with capsulolabral complex reconstructions only,23,24 but posterior bone block procedures have particularly been indicated for posterior bony Bankart lesions, posterior glenoid dysplasia, and glenoid erosion.25,26 Even in the absence of an osseous deficiency, posterior bone blocks have been perform with the intention of extending the glenoid surface.27 Despite some authors’ proposal that soft-tissue repair with bone loss greater than 20% remain unstable,28 the percentage of critical posterior glenoid bone loss is yet to be defined.29,30

The use of arthroscopic bone block techniques is being adopted more widely nowadays because of their potential benefits, the minimally invasive nature of arthroscopy procedures. and the association between graft osteolysis and glenohumeral osteoarthritis and metal implants.31, 32, 33 Moreover, although technically demanding, this technique has been shown to be reliable in restoring glenohumeral contact pressure and having very good clinical results.34,35

We present an arthroscopic anatomical metal-free bone block fixation technique (Fig 13 A and B) with capsule labral reconstruction for posterior shoulder instability. With this technique, we are able to eliminate problems related to the traditional bone fixation with screws or buttons, where bone remodeling can eventually lead to exposure of the metal implant and therefore result in a painful but stable shoulder. Careful must be taken not to damage surrounding neurovascular structures such as the suprascapular nerve, while introducing the posterior Guide. For that matter, a posterior accessory portal must be made flush with the posterior border if the glenoid. We believe this technique can be indicated for posterior shoulder instability of varying origins. It can also restore stability to the glenohumeral joint due to its strong 80 Newton fixation. In addition, double FiberTape cerclage fixation to its native glenoid and the extra-articular position of the bone block after capsulolabral complex reconstruction can be the answer to the concerns of metal implants and open procedure complications.

Fig 13.

(A-B) Graphical representation of the posterior bone block cerclage. (A, allograft; FT, FiberTape Cerclage System; G, glenoid.)

In conclusion, the all-arthroscopic posterior bone block cerclage technique—without the use of a metal implant—is a reproducible surgical intervention used for the treatment of posterior shoulder instability. We believe it potentially avoids the many known complications related to the usage of metal components, whilst still providing a strong fixation of the bone implant.

Footnotes

The authors report the following potential conflicts of interest or sources of funding: A-I.H. reports nonfinancial support from Arthrex, outside the submitted work, and a patent pending from Bone Block Cerclage. Full ICMJE author disclosure forms are available for this article online, as supplementary material.

Supplementary Data

This is a step-by-step video guide of our arthroscopic anatomical metal-free bone block fixation technique with capsulolabral reconstruction for posterior shoulder instability. The patient is a 23-year-old man who presented with chronic right shoulder discomfort, with no history of traumatic events or complete dislocations. However, he complained of multiple episodes of subluxation during activities of daily living, work, and sports. On physical examination, the patient had a positive posterior apprehension test as well as capsular hyperlaxity, a positive jerk test, and a positive posterior load and shift test. The patient was also able to reproduce posterior subluxation. No bone loss was seen on radiograph, computed tomography scan, or magnetic resonance imaging. We opted for surgical treatment, performing our posterior bone block cerclage technique. The patient is placed in a lateral decubitus position with his arm in a 3-point shoulder distraction system. Three classic portals are placed (posterior, anterior rotator interval, and superior long head of the biceps tendon). During diagnostic arthroscopy, capsular laxity and a posteroinferior labrum lesion were seen. We start by debriding and releasing the posteroinferior capsulolabral tissue from 11 to 6 o ‘clock and by preparing the posterior glenoid bone looking through a superior portal. Retraction of the capsulolabral complex with polydioxanone suture permits a perfect view of the posterior edge of the glenoid. We then proceed to measure the dimensions of the defect from superior to inferior and mark the center with an electrocoagulator. An arthroscopic fixed off-set posterior guide hook is placed parallel to the glenoid surface, at the previously marked center of the defect. Two 2-mm cannulated drills are inserted through the guide, 10 mm apart. With an arthroscopic rod, we find the drills anteriorly and then we make 2 holes with a coagulator in the anterior capsule between the subscapularis and the labrum. The distance from distal tunnel to inferior glenoid border is then measured as well as the distance from the articular surface to the tunnels. The graft is cut and shaped according to these measures. The core of the drills is next replaced with nitinol loops, with one loop facing posteriorly and the other facing anteriorly. The 2 nitinol loops are then replaced, through the anterior portal, with FiberLink sutures with the loops placed in the same way, this is done to avoid breakage with traction. Dilation of the posterior portal is then performed for graft passage through the incision with a gentle split of the infraspinatus muscle. Two FiberTape cerclage sutures are passed through the bone graft. In this case, the free end is connected to the superior FiberLink loop and shuttled through the glenoid from posterior to anterior portal. It is then retrieved and shuttled through the glenoid, from the anterior to the posterior portal, using the inferior FiberLink loop. The bone graft is inserted manually into the glenohumeral joint and placed on the defect. Next, the FiberTape cerclage suture ends are interconnected and tensioned with alternating manual traction, pushing the pretied knot towards the graft, avoiding loose sutures. Then, with a tensioner, the sutures are tightened up to 80 newtons. Three alternated half hitch knots are then made for each strand. Finally, capsulolabral reconstruction is achieved using 4 Arthrex 1.8-mm curved Knotless FiberTak Soft Anchors. Immediate postoperative radiograph results are presented, later repeated at 1-month of follow-up along with a computed tomography scan performed 3 months after surgery. Four months postoperatively, the allograft is integrated, and the patient is working and making his way back to sports.

References

- 1.Woodmass J.M., Lee J., Wu I.T. Incidence of posterior shoulder instability and trends in surgical reconstruction: A 22-year population-based study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2019;28:611–616. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2018.08.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Provencher M.T., Leclere L.E., King S. Posterior instability of the shoulder: Diagnosis and management. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39:874–886. doi: 10.1177/0363546510384232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chang E.S., Greco N.J., McClincy M.P., Bradley J.P. Posterior shoulder instability in overhead athletes. Orthop Clin North Am. 2016;47:179–187. doi: 10.1016/j.ocl.2015.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rouleau D.M., Hebert-Davies J., Robinson C.M. Acute traumatic posterior shoulder dislocation. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2014;22:145–152. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-22-03-145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frank R.M., Romeo A.A., Provencher M.T. Posterior glenohumeral instability: Evidence-based treatment. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2017;25:610–623. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-15-00631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clavert P., Furioli E., Andieu K. Clinical outcomes of posterior bone block procedures for posterior shoulder instability: Multicenter retrospective study of 66 cases. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2017;103:S193–S197. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2017.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Servien E., Walch G., Cortes Z.E., Edwards T.B., O’Connor D.P. Posterior bone block procedure for posterior shoulder instability. Knee Surg Sport Traumatol Arthrosc. 2007;15:1130–1136. doi: 10.1007/s00167-007-0316-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lafosse L., Franceschi G., Kordasiewicz B., Andrews W.J., Schwartz D. Arthroscopic posterior bone block: Surgical technique. Musculoskelet Surg. 2012;96:205–212. doi: 10.1007/s12306-012-0220-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DiMaria S., Bokshan S.L., Nacca C., Owens B. History of surgical stabilization for posterior shoulder instability. JSES Open Access. 2019;3:350–356. doi: 10.1016/j.jses.2019.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alepuz E.S., Pérez-Barquero J.A., Jorge N.J., García F.L., Baixauli V.C. Treatment of the posterior unstable shoulder. Open Orthop J. 2017;11:826–847. doi: 10.2174/1874325001711010826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wellmann M., Pastor M.F., Ettinger M., Koester K., Smith T. Arthroscopic posterior bone block stabilization-early results of an effective procedure for the recurrent posterior instability. Knee Surg Sport Traumatol Arthrosc. 2018;26:292–298. doi: 10.1007/s00167-017-4753-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barbier O., Ollat D., Marchaland J.P., Versier G. Iliac bone-block autograft for posterior shoulder instability. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2009;95:100–107. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2008.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boileau P., Hardy M.B., McClelland W.B., Thélu C.E., Schwartz D.G. Arthroscopic posterior bone block procedure: a new technique using suture anchor fixation. Arthrosc Tech. 2013;2:e473–e477. doi: 10.1016/j.eats.2013.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Waterman B.R., Chandler P.J., Teague E., Provencher M.T., Tokish J.M., Pallis M.P. Short-term outcomes of glenoid bone block augmentation for complex anterior shoulder instability in a high-risk population. Arthroscopy. 2016;32:1784–1790. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2016.01.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Magone K., Luckenbill D., Goswami T. Metal ions as inflammatory initiators of osteolysis. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2015;135:683–695. doi: 10.1007/s00402-015-2196-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hachem A.I., Del Carmen M., Verdalet I., Rius J. Arthroscopic bone block cerclage: A fixation method for glenoid bone loss reconstruction without metal implants. Arthrosc Tech. 2019;8:e1591–e1597. doi: 10.1016/j.eats.2019.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Forsythe B., Ghodadra N., Romeo A.A., Provencher M.T. Management of the failed posterior/multidirectional instability patient. Sports Med Arthrosc. 2010;18:149–161. doi: 10.1097/JSA.0b013e3181ec4397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beaulieu-Jones B.R., Peebles L.A., Golijanin P. Characterization of posterior glenoid bone loss morphology in patients with posterior shoulder instability. Arthroscopy. 2019;35:2777–2784. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2019.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moroder P., Scheibel M. ABC-Klassifikation der hinteren Schulterinstabilität. Obere Extrem. 2017;12:66–74. doi: 10.1007/s11678-017-0404-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moroder P., Danzinger V., Maziak N. Characteristics of functional shoulder instability. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2020;29:68–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2019.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Imhoff F.B., Camenzind R.S., Obopilwe E. Glenoid retroversion is an important factor for humeral head centration and the biomechanics of posterior shoulder stability. Knee Surg Sport Traumatol Arthrosc. 2019;27:3952–3961. doi: 10.1007/s00167-019-05573-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Owens B.D., Campbell S.E., Cameron K.L. Risk factors for posterior shoulder instability in young athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41:2645–2649. doi: 10.1177/0363546513501508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Delong J.M., Jiang K., Bradley J.P. Posterior instability of the shoulder: A systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical outcomes. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43:1805–1817. doi: 10.1177/0363546515577622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sanchez G., Kennedy N.I., Ferrari M.B., Mannava S., Frangiamore S.J., Provencher M.T. Arthroscopic labral repair in the setting of recurrent posterior shoulder instability. Arthrosc Tech. 2017;6:e1789–e1794. doi: 10.1016/j.eats.2017.06.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meuffels D.E., Schuit H., Van Biezen F.C., Reijman M., Verhaar J.A.N. The posterior bone block procedure in posterior shoulder instability: A long-term follow-up study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2010;92:651–655. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.92B5.23529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Castagna A., Conti M., Garofalo R. Soft tissue-based surgical techniques for treatment of posterior shoulder instability. Obere Extremität. 2017;12:82–89. doi: 10.1007/s11678-017-0413-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith T., Goede F., Struck M., Wellmann M. Arthroscopic posterior shoulder stabilization with an iliac bone graft and capsular repair: A novel technique. Arthrosc Tech. 2012;1:e181–e185. doi: 10.1016/j.eats.2012.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nacca C., Gil J.A., Badida R., Crisco J.J., Owens B.D. Critical glenoid bone loss in posterior shoulder instability. Am J Sports Med. 2018;46:1058–1063. doi: 10.1177/0363546518758015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hines A., Cook J.B., Shaha J.S. Glenoid bone loss in posterior shoulder instability: Prevalence and outcomes in arthroscopic treatment. Am J Sports Med. 2018;46:1053–1057. doi: 10.1177/0363546517750628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Longo U.G., Rizzello G., Locher J. Bone loss in patients with posterior gleno-humeral instability: a systematic review. Knee Surg Sport Traumatol Arthrosc. 2016;24:612–617. doi: 10.1007/s00167-014-3161-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cerciello S., Visonà E., Morris B.J., Corona K. Bone block procedures in posterior shoulder instability. Knee Surg Sport Traumatol Arthrosc. 2016;24:604–611. doi: 10.1007/s00167-015-3607-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schwartz D.G., Goebel S., Piper K., Kordasiewicz B., Boyle S., Lafosse L. Arthroscopic posterior bone block augmentation in posterior shoulder instability. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22:1092–1101. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2012.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Woodmass J.M., Lee J., Johnson N.R. Nonoperative management of posterior shoulder instability: An assessment of survival and predictors for conversion to surgery at 1 to 10 years after diagnosis. Arthroscopy. 2019;35:1964–1970. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2019.01.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Parada S.A., Shaw K.A. Graft transfer technique in arthroscopic posterior glenoid reconstruction with distal tibia allograft. Arthrosc Tech. 2017;6:e1891–e1895. doi: 10.1016/j.eats.2017.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Frank R.M., Shin J., Saccomanno M.F. Comparison of glenohumeral contact pressures and contact areas after posterior glenoid reconstruction with an iliac crest bone graft or distal tibial osteochondral allograft. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42:2574–2582. doi: 10.1177/0363546514545860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

This is a step-by-step video guide of our arthroscopic anatomical metal-free bone block fixation technique with capsulolabral reconstruction for posterior shoulder instability. The patient is a 23-year-old man who presented with chronic right shoulder discomfort, with no history of traumatic events or complete dislocations. However, he complained of multiple episodes of subluxation during activities of daily living, work, and sports. On physical examination, the patient had a positive posterior apprehension test as well as capsular hyperlaxity, a positive jerk test, and a positive posterior load and shift test. The patient was also able to reproduce posterior subluxation. No bone loss was seen on radiograph, computed tomography scan, or magnetic resonance imaging. We opted for surgical treatment, performing our posterior bone block cerclage technique. The patient is placed in a lateral decubitus position with his arm in a 3-point shoulder distraction system. Three classic portals are placed (posterior, anterior rotator interval, and superior long head of the biceps tendon). During diagnostic arthroscopy, capsular laxity and a posteroinferior labrum lesion were seen. We start by debriding and releasing the posteroinferior capsulolabral tissue from 11 to 6 o ‘clock and by preparing the posterior glenoid bone looking through a superior portal. Retraction of the capsulolabral complex with polydioxanone suture permits a perfect view of the posterior edge of the glenoid. We then proceed to measure the dimensions of the defect from superior to inferior and mark the center with an electrocoagulator. An arthroscopic fixed off-set posterior guide hook is placed parallel to the glenoid surface, at the previously marked center of the defect. Two 2-mm cannulated drills are inserted through the guide, 10 mm apart. With an arthroscopic rod, we find the drills anteriorly and then we make 2 holes with a coagulator in the anterior capsule between the subscapularis and the labrum. The distance from distal tunnel to inferior glenoid border is then measured as well as the distance from the articular surface to the tunnels. The graft is cut and shaped according to these measures. The core of the drills is next replaced with nitinol loops, with one loop facing posteriorly and the other facing anteriorly. The 2 nitinol loops are then replaced, through the anterior portal, with FiberLink sutures with the loops placed in the same way, this is done to avoid breakage with traction. Dilation of the posterior portal is then performed for graft passage through the incision with a gentle split of the infraspinatus muscle. Two FiberTape cerclage sutures are passed through the bone graft. In this case, the free end is connected to the superior FiberLink loop and shuttled through the glenoid from posterior to anterior portal. It is then retrieved and shuttled through the glenoid, from the anterior to the posterior portal, using the inferior FiberLink loop. The bone graft is inserted manually into the glenohumeral joint and placed on the defect. Next, the FiberTape cerclage suture ends are interconnected and tensioned with alternating manual traction, pushing the pretied knot towards the graft, avoiding loose sutures. Then, with a tensioner, the sutures are tightened up to 80 newtons. Three alternated half hitch knots are then made for each strand. Finally, capsulolabral reconstruction is achieved using 4 Arthrex 1.8-mm curved Knotless FiberTak Soft Anchors. Immediate postoperative radiograph results are presented, later repeated at 1-month of follow-up along with a computed tomography scan performed 3 months after surgery. Four months postoperatively, the allograft is integrated, and the patient is working and making his way back to sports.