Abstract

Introduction

Despite the proven effectiveness of coordinated specialty care (CSC) programmes for first episode psychosis in the USA, CSC programmes often have low levels of engagement in family psychoeducation, and engagement of racial and ethnic minority family members is even lower than that for non-Latino white family members. The goal of this study is to develop and evaluate a culturally informed FAmily Motivational Engagement Strategy (FAMES) and implementation toolkit for CSC providers.

Methods and analysis

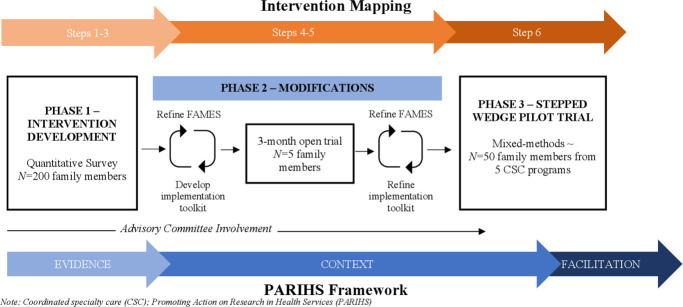

This protocol describes a mixed methods, multi-phase study that blends intervention mapping and the Promoting Action on Research in Health Services framework to develop, modify and pilot-test FAMES and an accompanying implementation toolkit. Phase 1 will convene a Stakeholder Advisory Committee to inform modifications based on findings from phases 1 and 2. During phase 1, we will also recruit approximately 200 family members to complete an online survey to assess barriers and motivation to engage in treatment. Phase 2 we will recruit five family members into a 3-month trial of the modified FAMES and implementation toolkit. Results will guide the advisory committee in refining the intervention and implementation toolkit. Phase 3 will involve a 16-month non-randomised, stepped-wedge trial with 50 family members from five CSC programmes in community-based mental health clinics to examine the acceptability, feasibility and initial impact of FAMES and the implementation toolkit.

Ethics and dissemination

This study received Institutional Review Board approval from Washington State University, protocol #17 812–001. Results will be disseminated via peer review publications, presentations at national and international conferences, and to local community mental health agencies and committees.

Trial registration number

ClinicalTrials.gov Registry (NCT04188366).

Keywords: mental health, schizophrenia & psychotic disorders, community child health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This pilot study will use an iterative mixed methods design to develop, implement and evaluate a culturally sensitive FAmily Motivational Engagement Strategy (FAMES) in coordinated specialty care programmes for first episode psychosis (FEP).

This protocol demonstrates the unique opportunity to blend intervention mapping and the Promoting Action on Research in Health Services framework.

Findings from a cross-sectional survey of family member experiences in phase 1 will be used by a Stakeholder Advisory Committee to inform FAMES and further modified using clinician and participant feedback from phase 2.

Phase 3 involves a non-randomised stepped-wedge trial with coordinated specialty care programmes to evaluate the acceptability and feasibility of FAMES.

As a pilot, this study has a sample size and limited to the context of coordinated specialty care programmes for FEP that limits generalisability.

Introduction

Coordinated specialty care (CSC) programmes in the USA ameliorate psychiatric symptoms and improve functioning and quality of life among youth and young adults experiencing first episode psychosis (FEP).1 CSC programmes feature evidence-based practices such as individual or multi-group family psychoeducation.2 There is considerable evidence demonstrating that family psychoeducation is associated with reduced relapse and rehospitalisation, and improved functional status and family management of psychosis.3–8 Family members have a key role in facilitating care and their participation in treatment is often associated with higher treatment engagement and quality of life of individuals with FEP, particularly among youth.9–16 Despite evidence for the effectiveness of CSC programmes and family psychoeducation, and the importance of family member involvement in mental health treatment, the implementation of family psychoeducation in CSC programmes has been low and is one the most challenging components of CSC according to providers.17 18 For instance, in a large clustered randomised trial of NAVIGATE, a CSC programme for FEP, 69% of family members did not participate in family psychoeducation and only 29% attended five or more appointments.19 20 These findings also revealed that racial/ethnic minority families engaged in treatment at lower rates than non-Hispanic whites.19 We need to better understand and systematically address factors and underlying mechanisms that affect the successful implementation of family-based interventions in mental health settings.

Previous studies suggest that low motivation and logistical, perceptual and cultural barriers hinder treatment engagement and subsequently limit successful implementation of family interventions like family psychoeducation.13 21–31 Logistical barriers include lack of financial resources, transportation problems and inadequate clinics operation hours.32–34 Perceptual and cognitive barriers include lack of interest due to religious beliefs, substantial burden and perceived lack of benefit.26 29 35 36 At the provider level, improving providers training in cultural competence and providing culturally sensitive care increases treatment engagement and retention, while also mitigating cultural and perceptual barriers.36 37 Although motivation has been identified as a mechanism for improving treatment engagement and retention among individuals with serious mental illnesses (eg, schizophrenia),38 39 research on engagement and family motivation has been limited. One study found that lower motivation was associated with greater perception of treatment barriers and lower engagement among family members of youth with conduct disorder.40

To address logistical, perceptual and cultural barriers to engagement, several strategies and interventions have successfully improved family engagement for individuals with conduct disorder,41 substance use disorders42–44 and those who access school programmes.45 Several of these studies have used techniques that enhance motivation and family engagement.41 46 For example, Nock and Kazdin developed the Participation Enhancement Intervention composed of three major components: (1) describing the importance of treatment engagement, (2) motivational statements about engagement and (3) addressing engagement barriers.41 In their randomised trial family members receiving the intervention showed greater motivation and engagement than family members in the control condition. Other strategies that have led to increased engagement are telephone-based interventions addressing treatment barriers47 48 and providing extrinsic motivators (incentives) for family involvement in mental healthcare.45

Study aims/objectives

The overarching purpose of this project is to assess the feasibility and acceptability of a brief provider-led FAmily Engagement Motivational Strategy (FAMES) and its accompanying implementation toolkit, and to examine its initial impact. This project has three phases: (1) survey family members regarding logistical, perceptual and cultural barriers, and motivators that influence engagement in CSC programmes for FEP to inform modifications; (2) refine FAMES and the implementation toolkit for use in CSC programmes for FEP using findings from aim 1 and with input from key stakeholders, such as clients with FEP and their family members, CSC providers and CSC organisational leaders and (3) examine the feasibility, acceptability and preliminary impact of FAMES in five CSC programmes using a stepped-wedge design.

Methods and analysis

Theoretical framework

This multi-site, mixed methods project will be completed in three phases: (1) intervention development, (2) intervention modification and (3) efficacy evaluation using a non-randomised stepped-wedge pilot trial design (figure 1). We will apply core components of intervention mapping (IM) and the Promoting Action on Research in Health Services (PARIHS) framework, a collaborative implementation framework (figure 1). IM is commonly used in implementation science to iteratively develop interventions and implementation strategies that are rooted in theory and incorporate stakeholder perspectives. IM is composed of six steps: (1) problem analysis (preliminary data), (2) review of theory-based methods and practical strategies, (3) development of the intervention, (4) modification of intervention methods and strategies, (5) development of the implementation plan and (6) evaluation.49 The PARIHS framework outlines factors necessary for the successful implementation of interventions into practice and has guided implementation. PARIHS is composed of three stages:50–54 (1) the evidence stage gathers information related on stakeholder experiences, needs and preferences to inform the intervention; (2) the context stage evaluates the acceptability, feasibility and sustainability of the intervention among stakeholders and (3) the facilitation stage is focused on the appropriateness of the intervention and provider skills.

Figure 1.

Study design: blend of intervention mapping and PARIHS framework. CSC, coordinated specialty care; FAMES, FAmily Engagement Motivational Strategy; PARIHS, Promoting Action on Research in Health Services.

Intervention components

FAMES will involve three distinct and revolving components—early, continuous and motivational contact—that incorporate motivational techniques previously used in other engagement interventions and constructs of the Self-Determination Theory (SDT).41 55 56 The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5th Edition (DSM-5) Cultural Formulation Interview (CFI) will be used to identify the unique needs of family members within the context of their culture, enhance the provider-family relationship and personalise treatment components of family psychoeducation.57–59

Early contact by email, phone or text message will occur 14, 7 and 2 days prior to the first scheduled orientation appointment for family members. To facilitate ongoing engagement, continuous contact between providers (eg, a licensed mental health counsellors, social workers or case managers) and family members will be made 12–16 days after each family appointment. During the early and continuous contacts, providers inquire about potential barriers participation in family appointments and other CSC appointments for their loved one. Providers will assess social support systems and remind family members of upcoming appointments. The motivational component will occur in person once per month and occurs in sync with established monthly family psychoeducation appointments. It is anticipated that the motivational component will last a duration of approximately 20 min at the start of the family psychoeducation appointment. Providers discuss the barriers that were identified during the early and continuous contacts, work with family members identify pragmatic and tangible solutions to these barriers (eg, extrinsic motivations), and develop a plan to overcome these barriers. Providers will prompt family members to create motivational statements (eg, intrinsic motivations) that are goal-driven, with an emphasis on overcoming these barriers and promoting continued engagement. During development and modification phases, we will identify and determine possible changes to the components and delivery of FAMES.

Implementation toolkit components

During phases 1 and 2, we will develop an implementation toolkit, designed to be a resource for providers to facilitate the uptake and implementation of FAMES.60 We anticipate that the FAMES implementation toolkit will use a combination of strategies (eg, implementation guides, fidelity checklist, audit and feedback, technical assistance, internal or external facilitators) that can be amendable to a specific CSC programme.61

Patient and public involvement

Patients, family members and other stakeholders were not involved to the research question, study design and outcomes measured. However, during these phases 1 and 2, a Stakeholder Advisory Committee will be convened, which will include two family members who have experience with CSC programmes for FEP, a CSC provider (eg, a licensed mental health counsellor, social worker or case manager), a former client who graduated from a CSC programme and a CSC administrator. An announcement for client and family member representatives will be disseminated through listserv and CSC programmes. Preference will be given to client and family representatives who identify as a racial/ethnic minority and the first author will select members who are interested and have time to dedicate to attending meetings. The Stakeholder Advisory Committee will meet via videoconference two to three times per year in phases 1 and phase 2 to aid in the modification of FAMES. Findings from all phases will be disseminated to community mental health agencies and patient and family advisory groups.

Phase 1: intervention development

Design

Based on previously collected and published data that informed IM step 1 (problem analysis),19 SDT was chosen as an overarching theoretical framework to ensure that the intervention’s underlining mechanism of motivation is targeted by incorporating specific components, such as motivational statements, an approach consistent with IM step 2 (review of theory-based methods and practical strategies).56 SDT focuses on three fundamental human needs: autonomy (choice), competence (self-efficacy) and relatedness (belonging). These are linked to a continuum of intrinsic motivations (internal drives to behave in a certain way such as core values and interests) and extrinsic motivations (external sources that result in external rewards such as awards).55

Aligned with the evidence stage of the PARIHS framework, approximately 200 family members of individuals with FEP will be recruited to complete a customised online Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) or paper survey instrument to identify family members’ needs and barriers to treatment and underlying proximal targets of change that may not have been previously identified. During IM steps 2 and 3, the Stakeholder Advisory Committee will meet several times throughout phase 1 to develop and discuss matrices of change objectives that are based on data from IM step 1 and are informed by survey findings. These meetings will build on the intervention components, previously described, to ensure that intervention components adequately address needs, barriers and proximal targets of change identified from survey findings in a feasible and practical way.

Inclusion criteria

Survey eligibility criteria are: (1) aged 18 years or older; (2) family member (eg, parent, guardian, aunt/uncle, spouse, grandparent, sibling, close friend) of an individual who has or had received services from an early intervention or CSC programme for FEP in the USA. Potential participants will be required to read an overview about the survey purpose and that participation is voluntary before being directed to survey questions.

Data collection

Surveys will be directly entered into REDCap through an online survey link. The survey link will be distributed through national and local listservs for family member support groups and CSC programmes and an emphasis will be placed on CSC providers to identify family members who have discontinued participation. Potential participants will be informed that the survey will take approximately 25 min to complete and a unique return code will be provided for participants who are unable to complete the entire survey in one sitting. A list of measures included in the survey are outlined in table 1.62

Table 1.

Outcomes and description of measures

| Outcome | Quantitative component—measure description | Qualitative component |

| Phase 1—intervention development | ||

| Barriers to Treatment Participation Scale,84 a 58-item semi-structured questionnaire that gathers information about five areas: stressors and obstacles that compete with treatment, treatment demands and issues, perceived relevance of treatment, relationship with the therapist and critical events. The Iowa Cultural Understanding Assessment (ICUA) is a 25-item measure to assess clients’ perception of cultural competence of the treatment agency and staff.85 To assess motivation about services, an adapted version of the 19-item Treatment Self-Regulation Questionnaire (TSRQ) will be used.71 The 26-item Youth Services Survey-Families (YSS-F) from the PhenX Toolkit will be used to assess satisfaction in the following domains: appropriateness, participation, cultural sensitivity, social connectedness and outcomes.86–88 Score >3.5 in each domain indicates positive experiences. Family members’ demographics will be captured. | ||

| Phase 2—modifications | ||

| Acceptability | Family member participants will complete the 8-item Client Satisfaction Questionnaire (CSQ-8) to rate overall satisfaction.89–91Possible total scores range from 8 to 32, with higher scores indicating greater satisfaction (>23 indicates satisfaction). | Semi-structured interviews |

| Practicality | Provider participants will complete a developed measure using a Likert Scale to evaluate the practicality to the extent that the intervention could be implemented with the resources, time and commitment available. The Organizational Readiness to Change Assessment (ORCA) tool consists of 77 items that will be used to assess evidence assessment, contextual readiness and facilitation needs.92 All items are scored on a Likert Scale from 1=strongly disagree to 5=strongly agree. | |

| Phase 3—Stepped-wedge pilot trial | ||

| Primary outcomes | ||

| Feasibility | Provider participants will rate the appropriateness of the intervention and implementation toolkit (eg, To what extent do you expect to be able to incorporate FAMES while working with family members? How useful were the components of the implementation toolkit?) Tracking the amount of external facilitator assistance needed to incorporate FAMES. | Semi-structured interviews |

| Acceptability | Family member participants will complete the CSQ-8, and the YSS-F will be used. Provider participants will rate satisfaction with toolkit and utility of individual items using a developed Likert Scale. | Semi-structured interviews |

| Secondary outcomes | ||

| Effectiveness | Engagement will be assessed as the total number of contact hours with family members by email, phone, text or in-person, and the total number of family psychoeducation appointments attended. Retention will be based on the percentage of families that drop out (family member declined or missed three consecutive appointments). | Semi-structured interviews |

| Motivation | Family member participants will complete the TSRQ. | |

| Family functioning | Family member participants will complete the 19-item Burden Assessment Scale.93 94 Total possible scores range from 10 to 171 (higher scores indicating greater burden). | |

| Cultural competence | Family member participants will complete the ICUA. | |

| Exploratory implementation outcomes | ||

| Readiness and facilitation | Provider participants will complete the ORCA to assess local adaptation needs and key components of PARIHS framework. | Semi-structured interviews |

| Fidelity | The percentage of all completed items on all required intervention checklists. | Audio/video-recordings |

| Sustainability/uptake | The total number of CSC programmes using all FAMES components and the number of programmes using one or more FAMES components. | |

CSC, coordinated specialty care; FAMES, FAmily Motivational Engagement Strategy; PARIHS, Promoting Action on Research in Health Services.

Data analysis

Descriptive analyses will be conducted to assess family members’ pathways to care, satisfaction with treatment, motivation for participation and suggested areas for improving CSC programmes. Regression analyses will be used to identify important components to services and to assess racial/ethnic group differences in treatment barriers, satisfaction and motivations.

Phase 2: modifications

Design

Aligned with the context stage (pre-evaluation) of the PARIHS, FAMES and the developed implementation toolkit will be studied across a 3-month time period among five family members from one CSC programme using a combined quantitative and qualitative mixed methods approach.63 Previous studies37 that have used IM have ranged in sample size from 2 to 10 between phase 2 will include the completion of IM step 4 (modification of intervention methods and strategies) and step 5 (development of the implementation plan) using an iterative process where the Stakeholder Advisory Committee will provide suggestions that will inform modifications to FAMES and development of the implementation toolkit. Regularly scheduled, audio-recorded Stakeholder Advisory Committee meetings will occur throughout this phase and include the review of quantitative and qualitative data summaries from the 3-month study. Suggested modifications identified from summaries will be compiled for the Stakeholder Advisory Committee to rate based on level of importance and feasibility and used to stimulate discussions on steps to refine intervention objectives and components. Similar to phase 1 steps to inform intervention components, the Stakeholder Advisory Committee meetings in phase 2 will also develop the learning objectives for the implementation toolkit and connect these objectives to a theory-based method and practical strategy that will be refined based on feedback from providers.

Setting

During phase 2, FAMES will be studied at one CSC programme within Washington State’s New Journeys network. New Journeys is a state-funded CSC programme for FEP with nine locations distributed in community mental health clinics in rural and urban settings throughout Washington State.64 Each New Journeys site employees four to eight mental health providers and currently serves a total of 300 clients with FEP. The New Journeys network serves approximately 55% racial/ethnic minorities; the average age of clients is 20 years; and 70% of clients reside with a family member or caregiver.

Inclusion criteria

Eligibility for inclusion for family member participants in phase 2 include: (1) aged 18 years or older; (2) one family member (eg, parent, guardian, grandparent, sibling) of an individual enrolled in a Washington State CSC programme and (3) has received no more than 3 months of services. Eligibility criteria for provider participants are (1) aged 18 years or older and (2) employed at a Washington State CSC programme for more than 2 months. Potential participants will be provided with a detailed explanation of the study purpose, the voluntary nature of participation and their right to withdraw from the study at any time. Research staff will obtain informed consent captured using REDCap e-consenting procedures.

Data collection and outcomes

To limit the burden on providers, self-reported measures for family member participants will be delivered directly to participants’ mobile devices and email accounts using mobile and text message enabled capabilities linked to a customised REDCap Database. Measures to assess acceptability and practicality will be collected at baseline and monthly throughout the 3-month study period. We will also measure the extent to which the intervention preliminarily impacts motivation. Measures to assess toolkit will be completed by provider participants at baseline that will inform the implementation process in real-time and after the 3-month study period that will be used by the Stakeholder Advisory Committee to improve the implementation toolkit. Separate qualitative interviews will be completed by family member and provider participants at months 1 and 3 using open-ended targeted questions to solicit opinions on what components may, or may not be working, suggestions for improvement and any lessons learnt. All Stakeholder Advisory Committee meetings will be audio-recorded to capture qualitative comments. Key concepts from quantitative and qualitative data will be presented during Stakeholder Advisory Committee meetings. Suggested improvements and action items will be rated by members on the Stakeholder Advisory Committee, based on feasibility and importance.65 These ratings will stimulate Stakeholder Advisory Committee meeting discussion points that will modify FAMES. These data will help us make improvements to the intervention delivery in real-time.

Quantitative data analysis

Descriptive analyses will be performed to assess satisfaction, motivation, practicality and implementation process. The mean score of ratings on practicality will be calculated and presented to the Stakeholder Advisory Committee.

Qualitative data analysis

All interview recordings will be transcribed verbatim and imported into NVivo V.11, a qualitative data management software. Due to its flexibility and ability to build on previous research identified in IM step 1 and phase 1, a directed content approach was selected for qualitative data analysis.66 67 Using a directed approach to content analysis satisfaction and areas for improvement will serve as initial pre-determined coding categories. Qualitative data gathered from family member and provider participants will be coded, summarised and presented to the Stakeholder Advisory Committee. The meeting recordings will be translated into actionable plans that will be re-presented to the Stakeholder Advisory Committee. To increase rigour, we will use member checks to confirm findings, keep detailed notes from each meeting and establish an audit trail.68 69

Phase 3: Stepped-wedge design pilot trial

Design

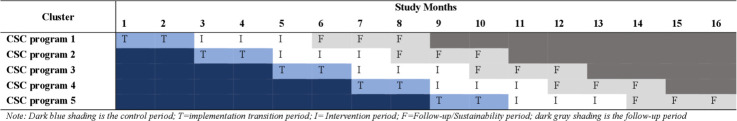

IM step 6 and the context (evaluation) and facilitation (appropriateness and skills) stage of the PARIHS informs phase 3. During this phase, we will conduct a non-randomised stepped-wedge pilot trial in five CSC programmes in Washington State using a combined quantitative and qualitative mixed methods approach.63 70 Each CSC programme will represent a cluster and serve as its own control (figure 2). A 2-month implementation transition period will occur at each CSC programme and during which providers will be introduced to the intervention using the implementation toolkits and trained to conduct FAMES. A 12-month open cohort design will be used to recruit approximately 50 family members during the study period.

Figure 2.

Modified stepped-wedge pilot trial of FAmily Motivational Engagement Strategy. CSC, coordinated specialty care.

Setting and inclusion criteria

In phase 3, FAMES will roll out sequentially in five CSC programmes in Washington State. Inclusion criteria and consent procedures for family members and provider participants in phase 3 will be with the same as details in phase 2.

Data collection and outcomes

The primary outcomes to be assessed are feasibility and acceptability of FAMES and the implementation toolkit. Primary outcome measures are described in detail in table 1. The secondary outcomes will include measures related to the preliminary impact of FAMES on family engagement. These secondary outcomes will include engagement and retention, to be obtained by providers and entered directly into the REDCap Database.71 Motivation, family functioning and cultural competence will also be captured using self-reported measures completed by family members. Primary and secondary outcome measures will be collected monthly during the control and intervention conditions. During the follow-up period for each programme, family members will complete measures related to treatment motivation and family functioning at 1 and 3 months post-intervention completion. Exploratory outcomes include implementation outcomes (eg, adherence, exposure, quality, differentiation, responsiveness) that will be tracked and assessed by external facilitators (ie, research staff) throughout the implementation phase and during the intervention condition using audio/video recordings to monitor the delivery of FAMES across all CSC programmes. At baseline and at 1 month follow-up provider participants will complete an organisational readiness measure that will assess key components of the PARIHS.54 Providers will also be asked to complete an online self-report intervention component checklist in REDCap after each contact and session.72

Sustainability and uptake will be tracked by research staff during the follow-up period at 1 and 3 months post-intervention completion. Qualitative interviews will be completed by family member and provider participants at two iteration points during the study. The first will occur 1 month post-implementation and the second during the follow-up period, 1 month post-intervention completion to assess acceptability (eg, satisfaction, influence of intervention on engagement), feasibility and key concepts of the PARIHS framework. Family members who discontinue study participation will be contacted and asked to complete an exit interview to assess acceptability (eg, reasons for discontinuation, burden of the intervention, barriers).73

Sample justification

The sample size (n=50) was chosen based on literature regarding sample sizes for pilot/feasibility studies while remaining feasible within the context of present study.74 While the trial is not designed to assess the effectiveness of FAMES the selected sample size will provide adequate power to preliminary analyses.75 Accounting for an incomplete stepped-wedge design project with five clusters (ie, community-based clinics) with an average recruitment of 10 family members per cluster, an intra cluster correlation of 0.10 and a significance level of 0.05, it is estimated that this will provide us with an estimated power of 0.84.

Quantitative data analysis

At the completion of the stepped-wedge trial in phase 3, analyses on the intent-to-treat sample will be performed (n=50). We will conduct descriptive analyses on the primary and secondary outcomes. We will also compare mean differences in satisfaction scores from control and intervention conditions, using independent sample t-tests. Generalised estimating equations will be used to assess differences in engagement by comparing the control and intervention conditions, while controlling for potential confounders (eg, time, site). To assess the mediation effect of motivation, cultural sensitivity and burden on the primary engagement and retention outcomes, we will path analytic modelling (eg, bootstrapped confidence intervals to evaluate indirect effects). If needed, we will use maximum likelihood, multiple imputation or other sensitivity analyses, including ‘missing not at random’ approaches, to account for missing data.76

Qualitative data analysis

The phase 3 qualitative analysis will also use key concepts derived from the SDT (eg, autonomy, competence, relatedness, extrinsic and intrinsic motivations). Areas related to acceptability (eg, satisfaction, intervention burden) will be used to develop and operationalise an initial coding scheme for data obtained from family member participants. Key concepts from the PARIHS framework such as organisational fit, relevance, range of flexibility and style will be used to develop and operationalise the initial coding scheme for data obtained from provider participants.77 Coding and analysis will be conducted independently by two coders through a series of iterative readings, noting text that corresponds to initial codes.69 78 79 A kappa of 0.8 will be required for coders to code independently and codes will be continuously refined.80 Notes will be used to develop a final codebook. To guard against biases of directive content analysis, an audit trail—documenting analytical decisions, analysing cases that did not fit our coding scheme, and generating new codes not present in initial codebooks—will be maintained.68

Mixed methods integration

A thematic matrix will integrate qualitative and quantitative data using a side-by-side comparison to examine feasibility, acceptability and implementation outcomes.81–83 We will answer questions such as: ‘will the qualitative data collected from family member participants match the quantitative data collected regarding satisfaction and engagement?’ Qualitative data collected from provider participants using the PARIHS framework will be used to explain quantitative data collected on fidelity measures. Barriers and facilitators identified by family members and providers will identify similarities and differences between these stakeholder groups that will be linked to provide further explanation and to help contextualise results.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical approval was granted by the Washington State University Institutional Review Board (#17761). In accordance with the funders’ policies, an independent Data and Safety Monitoring Board was established to assure safety of participants and data integrity. Findings from this study will be disseminated through publications in peer-reviewed academic journals and presented at local, national and international conferences. To disseminate results of the study across a wider audience, key findings will be communicated through social media and other media outlets.

Discussion

Despite previous research on engagement interventions in other populations and settings, little is known about strategies to engage family members in the context of CSC programmes. Research has also suggested inequities in utilisation of evidence-based interventions (eg, family psychoeducation) among racial/ethnic minorities that directly impacts successful implementation. We will use a mixed methods approach throughout the study to meld core components of IM and the PARIHS framework to develop, implement and evaluate the culturally informed FAMES and implementation toolkit to address these inequities; evaluation will focus on acceptability, feasibility and initial impact. Very little research has systematically used implementation science to address inequities in service utilisation related to race/ethnicity within community mental health clinics. The study protocol described will actively identify and modify strategies to address logistical and cultural barriers that contribute to these inequities at the family, provider and organisational levels. By using a rigorous mixed methods approach, this study will also provide a roadmap for implementation and local adaptation that may contribute important knowledge to the field of implementation science.

This study has several strengths, including the unique components of FAMES that will incorporate the DSM-5 CFI, which has only been previously focused on the assessment of individuals will now be tailored for families. This will allow providers to integrate culturally sensitive information to increase our understanding of family-related motivators related to treatment and that can then be incorporated into treatment planning for all racial/ethnic groups. The utilisation of a stepped-wedge design provides the opportunity to offer FAMES to all CSC programmes included in the study. It also presents an additional opportunity to assess whether FAMES has the potential to re-engage family members who over time have disengaged. In light of these strengths and potential impacts, family members’ participation may be limited for programmes that receive FAMES later in the trial. We will monitor family member participation during the control period with monthly programme check-ins. As a pilot study, it is important to note that overall findings are limited by sample size and generalisability. However, this pilot study includes six CSC programmes in rural and urban settings that will contribute to the iterative process of refining FAMES and its implementation various settings.

As the mental health field seeks to better understand motivations toward treatment in order to improve engagement and retention in CSC programmes, this study will explore how to effectively engage and motivate families from various racial/ethnic groups. If successful, our findings will influence the scale up of FAMES to other CSC programmes, while also potentially improving family engagement in other mental health services.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge and thank the following partners and advisors for their integral assistance in developing and implementing this study: Washington State Health Care Authority.

Footnotes

Contributors: OO developed the concept, study design and drafted the first version of the study protocol. DD, SMM, RLF, MTC, MGM and LJC contributed to the study design and revised subsequent versions of the study protocol. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This project is funded and supported by the National Institute of Mental Health K01MH117457 awarded to OO.

Disclaimer: The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agency.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Kane JM, Robinson DG, Schooler NR, et al. . Comprehensive versus usual community care for first-episode psychosis: 2-year outcomes from the NIMH raise early treatment program. Am J Psychiatry 2016;173:362–72. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15050632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wright A, Browne J, Mueser KT, et al. . Evidence-Based psychosocial treatment for individuals with early psychosis. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am 2020;29:211–23. 10.1016/j.chc.2019.08.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McFarlane WR, Lynch S, Melton R. Family psychoeducation in clinical high risk and first-episode psychosis. APS 2012;2:182–94. 10.2174/2210676611202020182 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Petrakis M, Oxley J, Bloom H. Carer psychoeducation in first-episode psychosis: evaluation outcomes from a structured group programme. Int J Soc Psychiatry 2013;59:391–7. 10.1177/0020764012438476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coldham EL, Addington J, Addington D. Medication adherence of individuals with a first episode of psychosis. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2002;106:286–90. 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2002.02437.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dixon L, Adams C, Lucksted A. Update on family psychoeducation for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 2000;26:5–20. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kreyenbuhl J, Nossel IR, Dixon LB. Disengagement from mental health treatment among individuals with schizophrenia and strategies for facilitating connections to care: a review of the literature. Schizophr Bull 2009;35:696–703. 10.1093/schbul/sbp046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dyck DG, Short RA, Hendryx MS, et al. . Management of negative symptoms among patients with schizophrenia attending multiple-family groups. Psychiatric Services 2000;51:513–9. 10.1176/appi.ps.51.4.513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Addington J, Collins A, McCleery A, et al. . The role of family work in early psychosis. Schizophr Res 2005;79:77–83. 10.1016/j.schres.2005.01.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marino L, Nossel I, Choi JC, et al. . The raise connection program for early psychosis: secondary outcomes and mediators and moderators of improvement. J Nerv Ment Dis 2015;203:365–71. 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Conus P, Lambert M, Cotton S, et al. . Rate and predictors of service disengagement in an epidemiological first-episode psychosis cohort. Schizophr Res 2010;118:256–63. 10.1016/j.schres.2010.01.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Haan L, Peters B, Dingemans P, et al. . Attitudes of patients toward the first psychotic episode and the start of treatment. Schizophr Bull 2002;28:431–42. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a006951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Compton MT. Barriers to initial outpatient treatment engagement following first hospitalization for a first episode of nonaffective psychosis: a descriptive case series. J Psychiatr Pract 2005;11:62–9. 10.1097/00131746-200501000-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Compton MT, Esterberg ML, Druss BG, et al. . A descriptive study of pathways to care among hospitalized urban African American first-episode schizophrenia-spectrum patients. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2006;41:566–73. 10.1007/s00127-006-0065-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oluwoye O, Cheng SC, Fraser E, et al. . Family experiences prior to the initiation of care for first-episode psychosis: a meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. J Child Fam Stud 2019:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oluwoye O, Kriegel L, Alcover KC, et al. . The impact of early family contact on quality of life among non-Hispanic blacks and whites in the RAISE-ETP trial. Schizophr Res 2020;216:523–5. 10.1016/j.schres.2019.12.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Addington J, Burnett P. Working with families in the early stages of psychosis In: Psychological interventions in early psychosis: a treatment Handbook, 2004: 99–116. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oluwoye O, Stokes B, Stiles B, et al. . Understanding differences in family engagement and provider outreach in Washington's new journeys first-episode psychosis program. Psychiatry Res 2020;113286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oluwoye O, Stiles B, Monroe-DeVita M, et al. . Racial-ethnic disparities in first-episode psychosis treatment outcomes from the RAISE-ETP study. Psychiatric Services 2018;69:1138–45. 10.1176/appi.ps.201800067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Glynn S, Gingerich S, Meyer-Kalos P, et al. . T255. who participated in family work in the US raise-etp first episode sample? Schizophr Bull 2018;44:S216–7. 10.1093/schbul/sby016.531 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Addington J, Heinssen RK, Robinson DG, et al. . Duration of untreated psychosis in community treatment settings in the United States. Psychiatric Services 2015;66:753–6. 10.1176/appi.ps.201400124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Loebel AD, Lieberman JA, Alvir JM, et al. . Duration of psychosis and outcome in first-episode schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1992;149:1183. 10.1176/ajp.149.9.1183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harrigan SM, McGorry PD, Krstev H. Does treatment delay in first-episode psychosis really matter? Psychol Med 2003;33:97–110. 10.1017/S003329170200675X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Black K, Peters L, Rui Q, et al. . Duration of untreated psychosis predicts treatment outcome in an early psychosis program. Schizophr Res 2001;47:215–22. 10.1016/S0920-9964(00)00144-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morgan C, Abdul-Al R, Lappin JM, et al. . Clinical and social determinants of duration of untreated psychosis in the ÆSOP first-episode psychosis study. Br J Psychiatry 2006;189:446–52. 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.021303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Compton MT, Goulding SM, Gordon TL, et al. . Family-Level predictors and correlates of the duration of untreated psychosis in African American first-episode patients. Schizophr Res 2009;115:338–45. 10.1016/j.schres.2009.09.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Commander MJ, Cochrane R, Sashidharan SP, et al. . Mental health care for Asian, black and white patients with non-affective psychoses: pathways to the psychiatric Hospital, in-patient and after-care. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1999;34:484–91. 10.1007/s001270050224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lucksted A, Essock SM, Stevenson J, et al. . Client views of engagement in the raise connection program for early psychosis recovery. Psychiatric Services 2015;66:699–704. 10.1176/appi.ps.201400475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dixon L, McFarlane WR, Lefley H, et al. . Evidence-Based practices for services to families of people with psychiatric disabilities. Psychiatr Serv 2001;52:903–10. 10.1176/appi.ps.52.7.903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McKay MM, Bannon WM. Engaging families in child mental health services. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am 2004;13:905–21. 10.1016/j.chc.2004.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barnett ML, Davis EM, Callejas LM, et al. . The development and evaluation of a natural helpers' training program to increase the engagement of urban, Latina/o families in parent-child interaction therapy. Child Youth Serv Rev 2016;65:17–25. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2016.03.016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Spoth R, Redmond C. Research on family engagement in preventive interventions: toward improved use of scientific findings in primary prevention practice. J Prim Prev 2000;21:267–84. 10.1023/A:1007039421026 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ofonedu ME, Belcher HME, Budhathoki C, et al. . Understanding barriers to initial treatment engagement among underserved families seeking mental health services. J Child Fam Stud 2017;26:863–76. 10.1007/s10826-016-0603-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scheppers E, et al. Potential barriers to the use of health services among ethnic minorities: a review. Fam Pract 2006;23:325–48. 10.1093/fampra/cmi113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Compton M, Kaslow NJ, Walker EF. Observations on parent/family factors that may influence the duration of untreated psychosis among African American first-episode schizophrenia-spectrum patients. Schizophr Res 2004;68:373–85. 10.1016/j.schres.2003.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fisher TL, Burnet DL, Huang ES, et al. . Cultural leverage: interventions using culture to narrow racial disparities in health care. Med Care Res Rev 2007;64:243S–82. 10.1177/1077558707305414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cabassa LJ, Druss B, Wang Y, et al. . Collaborative planning approach to inform the implementation of a healthcare manager intervention for Hispanics with serious mental illness: a study protocol. Implement Sci 2011;6:80. 10.1186/1748-5908-6-80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jochems EC, Duivenvoorden HJ, Dam A, et al. . Motivation, treatment engagement and psychosocial outcomes in outpatients with severe mental illness: a test of Self‐Determination theory. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 2017;26:e1537 10.1002/mpr.1537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jochems EC, Mulder CL, van Dam A, et al. . Motivation and treatment engagement intervention trial (MotivaTe-IT): the effects of motivation feedback to clinicians on treatment engagement in patients with severe mental illness. BMC Psychiatry 2012;12:209. 10.1186/1471-244X-12-209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nock MK, Ferriter C. Parent management of attendance and adherence in child and adolescent therapy: a conceptual and empirical review. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev 2005;8:149–66. 10.1007/s10567-005-4753-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nock MK, Kazdin AE. Randomized controlled trial of a brief intervention for increasing participation in parent management training. J Consult Clin Psychol 2005;73:872–9. 10.1037/0022-006X.73.5.872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mullins SM, Suarez M, Ondersma SJ, et al. . The impact of motivational interviewing on substance abuse treatment retention: a randomized control trial of women involved with child welfare. J Subst Abuse Treat 2004;27:51–8. 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Szapocznik J, Perez-Vidai A, Brickman AL, et al. . Engaging adolescent drug abusers and their families in treatment: a strategic structural systems approach. Annual Review of Addictions Research and Treatment 1991;1:331–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Santisteban DA, Szapocznik J, Perez-Vidal A, et al. . Efficacy of intervention for engaging youth and families into treatment and some variables that may contribute to differential effectiveness. Journal of Family Psychology 1996;10:35–44. 10.1037/0893-3200.10.1.35 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Heinrichs N. The effects of two different incentives on recruitment rates of families into a prevention program. J Prim Prev 2006;27:345–65. 10.1007/s10935-006-0038-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Grote NK, Swartz HA, Geibel SL, et al. . A randomized controlled trial of culturally relevant, brief interpersonal psychotherapy for perinatal depression. Psychiatric Services 2009;60:313–21. 10.1176/ps.2009.60.3.313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McKay MM, Hibbert R, Hoagwood K, et al. . Integrating Evidence-Based Engagement Interventions Into “Real World” Child Mental Health Settings. Brief Treat Crisis Interv 2004;4:177–86. 10.1093/brief-treatment/mhh014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McKay MM, McCadam K, Gonzales JJ. Addressing the barriers to mental health services for inner City children and their caretakers. Community Ment Health J 1996;32:353–61. 10.1007/BF02249453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bartholomew LK, Parcel GS, Kok G. Intervention mapping: a process for developing theory and evidence-based health education programs. Health Educ Behav 1998;25:545–63. 10.1177/109019819802500502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rycroft-Malone J. The PARIHS Framework—A framework for guiding the implementation of evidence-based practice. J Nurs Care Qual 2004;19:297–304. 10.1097/00001786-200410000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kitson AL, Rycroft-Malone J, Harvey G, et al. . Evaluating the successful implementation of evidence into practice using the PARiHS framework: theoretical and practical challenges. Implementation Science 2008;3:1 10.1186/1748-5908-3-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rycroft-Malone J, Bucknall T. Models and frameworks for implementing evidence-based practice: linking evidence to action. vol 2. John Wiley & Sons, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ullrich PM, Sahay A, Stetler CB. Use of implementation theory: a focus on PARIHS. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs 2014;11:26–34. 10.1111/wvn.12016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stetler CB, Damschroder LJ, Helfrich CD, et al. . A guide for applying a revised version of the PARIHS framework for implementation. Implementation Science 2011;6:99 10.1186/1748-5908-6-99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist 2000;55:68–78. 10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Deci EL, Ryan RM. Self-determination theory. Handbook of theories of social psychology 2011;2011:416–33. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lewis-Fernández R, Aggarwal NK, Lam PC, et al. . Feasibility, acceptability and clinical utility of the cultural formulation interview: mixed-methods results from the DSM-5 international field trial. Br J Psychiatry 2017;210:290–7. 10.1192/bjp.bp.116.193862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Aggarwal NK, Desilva R, Nicasio AV, et al. . Does the cultural formulation interview for the fifth revision of the diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5) affect medical communication? A qualitative exploratory study from the new York site. Ethn Health 2015;20:1–28. 10.1080/13557858.2013.857762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lewis-Fernández R, Aggarwal NK, Bäärnhielm S, et al. . Culture and Psychiatric Evaluation: Operationalizing Cultural Formulation for DSM-5. Psychiatry 2014;77:130–54. 10.1521/psyc.2014.77.2.130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hempel S, O’Hanlon C, Lim YW, et al. . Spread tools: a systematic review of components, uptake, and effectiveness of quality improvement toolkits. Implementation Science 2019;14:83 10.1186/s13012-019-0929-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Powell BJ, Beidas RS, Lewis CC, et al. . Methods to improve the selection and tailoring of implementation strategies. J Behav Health Serv Res 2017;44:177–94. 10.1007/s11414-015-9475-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. . Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009;42:377–81. 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Palinkas LA, Aarons GA, Horwitz S, et al. . Mixed method designs in implementation research. Adm Policy Ment Health 2011;38:44–53. 10.1007/s10488-010-0314-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Oluwoye O, Reneau H, Stokes B, et al. . Preliminary evaluation of washington state’s early intervention program for first-episode psychosis. Psychiatric Services 2019:201900199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Waltz TJ, Powell BJ, Matthieu MM, et al. . Use of concept mapping to characterize relationships among implementation strategies and assess their feasibility and importance: results from the expert recommendations for implementing change (ERIC) study. Implementation Science 2015;10:109 10.1186/s13012-015-0295-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Saldaña J. The coding manual for qualitative researchers. Sage, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res 2005;15:1277–88. 10.1177/1049732305276687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Padgett DK. Qualitative methods in social work research. vol 36. Sage Publications, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative data analysis: an expanded sourcebook. sage, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Proctor EK, Knudsen KJ, Fedoravicius N, et al. . Implementation of evidence-based practice in community behavioral health: agency director perspectives. Adm Policy Ment Health 2007;34:479–88. 10.1007/s10488-007-0129-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ryan RM, Plant RW, O'Malley S. Initial motivations for alcohol treatment: relations with patient characteristics, treatment involvement, and dropout. Addict Behav 1995;20:279–97. 10.1016/0306-4603(94)00072-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Feely M, Seay KD, Lanier P, et al. . Measuring fidelity in research studies: a field guide to developing a comprehensive fidelity measurement system. Child Adolesc Soc Work J 2018;35:139–52. 10.1007/s10560-017-0512-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sekhon M, Cartwright M, Francis JJ. Acceptability of healthcare interventions: an overview of reviews and development of a theoretical framework. BMC Health Serv Res 2017;17:88 10.1186/s12913-017-2031-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Billingham SAM, Whitehead AL, Julious SA. An audit of sample sizes for pilot and feasibility trials being undertaken in the United Kingdom registered in the United Kingdom clinical research network database. BMC Med Res Methodol 2013;13:104. 10.1186/1471-2288-13-104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hemming K, Taljaard M. Sample size calculations for stepped wedge and cluster randomised trials: a unified approach. J Clin Epidemiol 2016;69:137–46. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.08.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.McPherson S, Barbosa-Leiker C, Mamey MR, et al. . A ‘missing not at random’ (MNAR) and ‘missing at random’ (MAR) growth model comparison with a buprenorphine/naloxone clinical trial. Addiction 2015;110:51–8. 10.1111/add.12714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kitson A, Harvey G, McCormack B. Enabling the implementation of evidence based practice: a conceptual framework. Qual Health Care 1998;7:149–58. 10.1136/qshc.7.3.149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Emerson RM, Fretz RI, Shaw LL. Fieldnotes in ethnographic research (fragments de texte. University of Chicago Press, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ryan GW, Bernard HR. Data management and analysis methods, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Curry LA, Nembhard IM, Bradley EH. Qualitative and mixed methods provide unique contributions to outcomes research. Circulation 2009;119:1442–52. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.742775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Fereday J, Muir-Cochrane E. Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: a hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. Int J Qual Methods 2006;5:80–92. 10.1177/160940690600500107 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Crabtree BF, Miller WF. A template approach to text analysis: developing and using codebooks, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Creswell JW, Plano-‐clark VL. Designing and conducting mixed methods research, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kazdin AE, Holland L, Crowley M, et al. . Barriers to treatment participation scale: evaluation and validation in the context of child outpatient treatment. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1997;38:1051–62. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01621.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Improving cultural competence. Report No.: (SMA) 14-4849. ED. Rockville, MD: substance abuse and mental health services administration (US), 2014. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK82999/ [PubMed]

- 86.Brunk M, Koch J, McCall B. Report on parent satisfaction with services at community services boards. Virginia Department of Mental Health, Mental Retardation, and Substance Abuse Services 2008;8. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Riley SE, Stromberg AJ, Clark J. Assessing Parental Satisfaction with Children?s Mental Health Services with the Youth Services Survey for Families. J Child Fam Stud 2005;14:87–99. 10.1007/s10826-005-1124-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Shafer AB, Temple JM. Factor structure of the mental health statistics improvement program (MHSIP) family and youth satisfaction surveys. J Behav Health Serv Res 2013;40:306–16. 10.1007/s11414-013-9332-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Larsen DL, Attkisson CC, Hargreaves WA, et al. . Assessment of client/patient satisfaction: development of a general scale. Eval Program Plann 1979;2:197–207. 10.1016/0149-7189(79)90094-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Attkisson CC, Zwick R. The client satisfaction questionnaire. psychometric properties and correlations with service utilization and psychotherapy outcome. Eval Program Plann 1982;5:233–7. 10.1016/0149-7189(82)90074-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Nguyen TD, Attkisson CC, Stegner BL. Assessment of patient satisfaction: development and refinement of a service evaluation questionnaire. Eval Program Plann 1983;6:299–313. 10.1016/0149-7189(83)90010-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Helfrich CD, Li Y-F, Sharp ND, et al. . Organizational readiness to change assessment (orca): development of an instrument based on the promoting action on research in health services (PARIHS) framework. Implementation Science 2009;4:38 10.1186/1748-5908-4-38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Reinhard SC, Gubman GD, Horwitz AV, et al. . Burden assessment scale for families of the seriously mentally ill. Eval Program Plann 1994;17:261–9. 10.1016/0149-7189(94)90004-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Guada J, Land H, Han J. An exploratory factor analysis of the burden assessment scale with a sample of African-American families. Community Ment Health J 2011;47:233–42. 10.1007/s10597-010-9298-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.