Abstract

Objectives

The aim of the study was to identify key elements of whole system approaches to building healthy communities and putting communities at the heart of public health with a focus on public health practice to reduce health inequalities.

Design

A mixed-method qualitative study was undertaken. The primary method was semi-structured interviews with 17 public health leaders from 12 local areas. This was supplemented by a rapid review of literature, a survey of 342 members of the public via Public Health England’s (PHE) People’s Panel and a round-table discussion with 23 stakeholders.

Setting

Local government in England.

Results

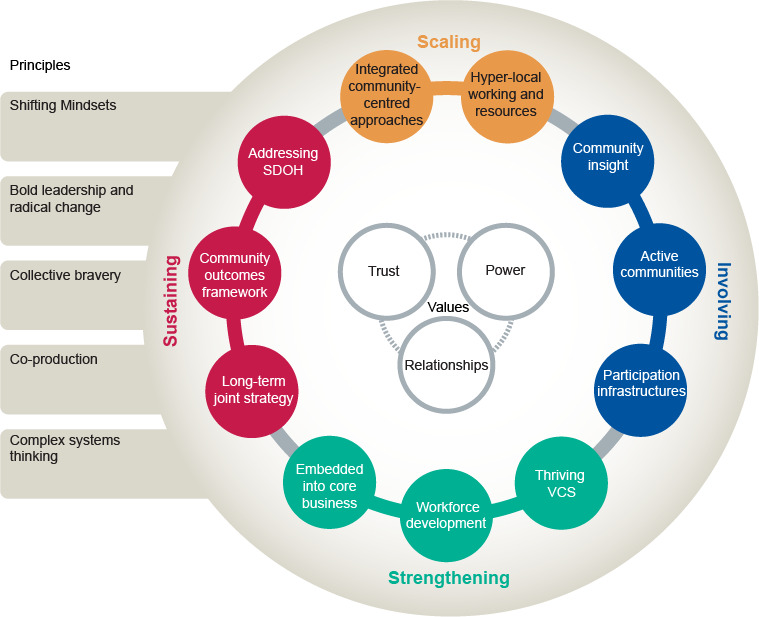

Eleven elements of community-centred public health practice that constitute taking a whole system approach were identified. These were grouped into the headings of involving, strengthening, scaling and sustaining. The elements were underpinned by a set of values and principles.

Conclusion

Local public health leaders are in a strong position to develop a whole system approach to reducing health inequalities that puts communities at its heart. The elements, values and principles summarise what a supportive infrastructure looks like and this could be further tested with other localities and communities as a framework for scaling community-centred public health.

Keywords: public health, health policy, preventive medicine

Strengths and limitations of this study.

It supports current policy interest and literature in reducing widening health inequalities through greater community engagement and empowerment.

There was high participation in all methods used in the study; responses from all invited interviewees and 74% of the public contacted (n=342).

Voices from disadvantaged communities were not directly collected in this study but limited to professional perspectives from community insight work.

The Framework Method of qualitative analysis was used effectively to distil learning drawn from different perspectives on public health practice.

The findings could be strengthened by conducting more interviews with other local areas, with leaders from other sectors, who are increasingly taking responsibility for reducing health inequalities, and with community members. There is potential for a further comparative implementation study.

Introduction

This study was part of a project to improve and increase the uptake of local whole system approaches to community-centred public health in Public Health England (PHE). It built on previous work to increase access to, and implementation of, evidence in community-centred approaches.1–3 It was developed in direct response to stakeholder requests for more information and support to scale up whole system approaches to shift community-centred ways of working from the margins to core public health practice. This paper describes the findings from research into local government areas (local authorities) that are already making this shift, and summarises the elements, values and principles of a whole system approach to community-centred public health.

Health inequalities in England continue to worsen4 5 and it is necessary to move on from traditional interventions that have not been working and to scale up those approaches which evidence has shown to be effective.5 6 Public health teams have been firmly established within the English local government system since 2013 and these teams are well-placed to make this happen.7 However, local authority capacity and resources have declined in recent years and deprived communities have borne the brunt of funding cuts and experienced rising need and inequalities.5

Community-centred approaches aim to reduce health inequalities through addressing marginalisation and powerlessness, and by creating more sustainable and effective interventions for and with those most in need.8–10 Empowerment, equity and social connectedness are recognised as three central concepts of evidence-based practice.1 Community-centred approaches differ from community-based interventions that merely engage ‘target’ populations as recipients of professionally-led activities.1 Many of the psychosocial factors and pathways that link wider conditions with health behaviours and outcomes exist at the community level and are addressed through community-centred approaches.2 11 12 Effective practice recognises and seeks to address determinants across the pathway, for example, wider factors, such as employment, housing or crime, alongside psychosocial factors of inclusion, belonging, cohesion and empowerment.11

In the English public health system despite good evidence, long-standing practice and clinical guidance that endorses community-centred approaches,13 there has been a dominance of interventions that focus on individual-level lifestyle behaviours rather than community-level determinants such as social connectedness, sense of belonging and participation in decision-making.1 6 Long-standing practice in community-centred approaches has been evident in most local authority areas but not at a reach and depth to affect persistent inequalities. Indeed, such approaches also have potential to further alienate or damage communities if reducing and challenging inequalities is not central to the approach or if they ignore systemic inequities.14–16 Box 1 outlines the principles of community-centred approaches, developed from evidence.1 2

Box 1. Principles of community-centred approaches.

Community-centred approaches are those that:

Promote health and well-being or reduce health inequalities in a community setting, using non-clinical methods.

Use participatory methods where community members are actively involved in design, delivery and evaluation.

Have measures in place to address barriers to engagement and enable people to play an active part.

Use and build on local community assets in developing and delivering the project.

Develop collaborations and partnerships with individuals and groups at most risk of poor health.

Have a focus on changing the conditions that drive poor health alongside individual factors.

Aim to increase people’s control over their health and lives.

Over the recent years, there has been increasing interest in applying ideas around complexity and systems thinking to public health and to care systems.6 17 18 PHE has begun to explore how whole system approaches can be used to improve health and reduce inequalities, with an initial focus on obesity,19 20 but community involvement elements are often underdeveloped or focus on engagement rather than co-production and empowerment. A whole system approach is defined as ‘responding to complexity’ through a ‘dynamic way of working’, bringing stakeholders, including communities, together to develop ‘a shared understanding of the challenge’ and integrate action to bring about sustainable, long-term systems change (p.17).21 Complex system thinking in public health can help understand and address the interconnectedness of distal and proximal determinants, including intermediary (or psychosocial) factors such as community-level determinants.

PHE’s Healthy Communities Team is seeking to build on this work, moving beyond commissioning community-centred approaches, to putting communities and community empowerment at the heart of all public health policy and practice and understanding how this can be scaled to a level that impacts on health inequalities.22 This is an ambition shared outside of England,19 such as in the community-centred health model advocated and scaled by the Prevention Institute in USA that recognises that community conditions are critical to health and community prevention strategies which foster health equity lead to lasting change.23 While England lacks similar scaled community-centred models, health-in-all-policies24 and place-based-working25 are other systems approaches that align to a community-centred approach and offer impact at scale.

Aim and objectives

The aim of the study was to identify key elements of whole system community-centred public health at a local authority level in England. It sought to build on the principles of community-centred approaches (box 1) by understanding how the public health system could become more community-centred and enable community connectedness and empowerment to be central to its role and functions.22

The objectives were:

To collate learning from local areas currently demonstrating leadership and best practice in reducing health inequalities through community-centred public health.

To engage stakeholders, including community members, in exploring and developing concepts, principles and steps to achieve scale and sustainability in community-centred public health.

Methods

The scope of the study focussed on public health practice to reduce health inequalities, which is led by local public health systems. A mixed-method study qualitative design was used to explore aspects of public health practice, taking account of different local contexts,26 and to develop pragmatic guidance for local systems. The design was informed by arguments for use of a systems approach to population health27 and for application of systems thinking in public health research.18 This informed the focus at local authority level and the mixed-method design drawing in a range of stakeholder perspectives. A project steering group provided oversight to the study and met at the beginning, middle and end to review methods and progress. It included staff from different parts of the organisation working on health inequalities, health improvement, whole system approaches, local authority delivery support, public engagement and voluntary and community sector (VCS) engagement, with the addition of an external adviser who acted as a critical friend. Other external stakeholders were consulted on an ad-hoc basis and as part of a stakeholder discussion (see below).

Patient and public involvement

No patient involved.

The primary method was: Semi-structured interviews with public health leaders from 12 local areas (key informant interviews). Between one and three representatives per area participated in a 60 to 90 min interview about their local practice. From a sample of 151 upper-tier local authority areas (who had public health responsibilities), a long list was generated of 29 who were demonstrating (1) strategic approaches, (2) cross-sector working, (3) leadership and (4) high-quality activity in community-centred approaches to reducing health inequalities. The list came from existing sources: PHE’s nine local centres across England and their networks with local authorities, examples from practice written for PHE’s online library (https://phelibrary.koha-ptfs.co.uk/practice-examples/caba/) and Local Government Association case studies (https://www.local.gov.uk/case-studies). The secondary criteria applied to the long list included achieving (1) geographical spread across the country, (2) diversity in approach and (3) demonstrable outcomes representing maturity of approach. This reduced the list to 12 areas who were approached for interview by email.

Five interviews were with Directors of Public Health, nine were with Consultants in Public Health or programme managers within the local authority, two were with a voluntary organisation that had been commissioned to provide strategic leadership and one interview was with a university researcher who was leading a collaborative project across several local authorities. Some of the interviewees had been involved in previous project work with PHE. Interviews were conducted by phone by either JSt or JSo, using an agreed schedule. Detailed notes were taken and then offered to interviewees for validation.

See box 2 for lines of inquiry.

Box 2. Lines of inquiry.

The definition and scope of whole system within this context.

The enabling conditions and prerequisites to community-centred public health, along with the barriers and detractors to progress.

The principles and components of whole system community-centred public health.

The value, advantages and disadvantages of adopting whole system community-centred public health.

The alignment of community-centred public health within local system priorities.

The key actions that local leaders can take to create a community-centred public health system.

Supplementary sources of evidence included:

A rapid review of literature28 was undertaken to gather published evidence that reported on whole system approaches in public health practice in order to supplement the primary data. Three groups of literature were explored:

International studies reporting on community engagement drawn from a recent systematic review on whole system approaches to public health.19

Additional publications focussed specifically on whole system community-centred public health, identified by a search conducted by PHE Knowledge and Library Services.

Key whole system frameworks and UK reports that are being used in the English public health system.29

A survey of members of the public: An online survey to PHE’s People’s Panel, which comprised 460 members of the public recruited from annual randomised household door-to-door public health Ipsos Mori market research. There were four demographic variables and five open questions (online supplementary file A). The first two questions helped to familiarise respondents with the issue. The survey was answered by 74% of the panel (n=342). More details on the sample in table 1.

Table 1.

People’s panel survey sample profile

| Frequency | Per cent | |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 101 | 29.5 |

| Female | 241 | 70.5 |

| Age, years | ||

| 16 to 24 | 1 | 0.3 |

| 25 to 34 | 14 | 4.1 |

| 35 to 44 | 34 | 9.9 |

| 45 to 54 | 58 | 17 |

| 55 to 64 | 103 | 30.1 |

| 65+ | 125 | 36.5 |

| Missing | 7 | 2 |

| Ethnic origin | ||

| Asian or Asian British | 12 | 3.5 |

| Black or Black British | 7 | 2 |

| Mixed | 3 | 0.9 |

| White British | 292 | 85.4 |

| White Other | 21 | 6.1 |

| Other | 1 | 0.3 |

| Missing | 6 | 1.8 |

| Region | ||

| East Midlands | 21 | 6.1 |

| East of England | 20 | 5.8 |

| London | 23 | 6.7 |

| North East | 37 | 10.8 |

| North West | 71 | 20.8 |

| South East | 64 | 18.7 |

| South West | 25 | 7.3 |

| West Midlands | 21 | 6.1 |

| Yorkshire and Humber | 56 | 16.4 |

| Missing | 4 | 1.2 |

bmjopen-2019-036044supp001.pdf (47.9KB, pdf)

Stakeholder round-table discussion: The findings from the three sources were tested with a group of 23 stakeholders at a round-table discussion. Stakeholders included the local area interviewees (n=8), representatives and experts from national bodies in VCS, health and social care sectors (n=10), and representatives from PHE programmes and areas of expertise (n=5). The first round of discussion involved the researchers presenting the findings and opening discussion on themes. The second round started with 4 to 5 participants giving formal and informal commentaries to provide different sector perspectives and stimulate thinking on the overall theme of whole system approaches to community-centred public health. A chairperson summarised key issues during and after each round. Discussion points were captured by two note-takers.

Analysis

Themes were developed iteratively, building from the interviews and corroborated by the literature and public survey.

A thematic analysis of the interview data was undertaken using the Framework Method.30 31 This method develops an analytical framework that structures data into categories to help summarise and reduce it and produce themes. A framework was developed based on six categories from the questions (local context, description of whole system community-centred approach, principles and components, outcomes, learning and transferable knowledge). Data from the first four interviews (cases) were summarised under each category and common concepts or themes (appearing more than once) were given a label (code). Data excerpts from the remaining cases were added into the framework and labelled with the codes or assigned a new one if a new concept or theme emerged. All the data were then re-checked to ensure that all common concepts were coded and had a distinct label. Themes were grouped into categories.

In the literature review, 10 papers, of the 65 included in the systematic review,13 reported links between effective community engagement and the success of the intervention. Further data extraction and synthesis was undertaken on these 10 papers to identify community engagement models and methods, barriers and facilitators and alignment to the public health system and goals. Following a search conducted by PHE Knowledge and Libraries and further screening, an additional 14 papers were included in the review and synthesis. These were from US (nine), Canada (two), Australia (two) and New Zealand (one). Details of these papers can be found in online supplementary file B.

bmjopen-2019-036044supp002.pdf (172.5KB, pdf)

Data from the public survey were inductively analysed by developing and using coding frameworks to produce salient thematic issues. The detail of these findings is reported elsewhere.32

The themes from the literature review and public survey were then added into the framework as additional data sources, mapping against the existing labels, adding strength or emphasis. This stage of analysis resulted in a complete framework of 26 themes.30 31 These were grouped into describing the context and starting points for the work, the elements that describe what was delivered to achieve a whole system approach to community-centred public health, the processes that describe how it was delivered and what the enablers and challenges were to the whole system approach (table 2).

Table 2.

Thematic framework

| Context | Elements of approach - what was delivered | Process for delivery - how | Enablers of whole system approach | Challenges |

| Health inequalities not reducing and the need for a radical approach or redesign across the system. | Community-centred prevention approaches as part of integrated commissioning alongside community-oriented services with NHS, Social care and (VCS) | Informed by in-depth insight (research) with communities | Having a strong case for change and overarching strategic ambition for the council and partners | The impact of cuts and austerity and importance of financial inclusion. |

| The need to reduce demand on services. | Building VCS capacity and valuing VCS contribution, including volunteering. | A comprehensive outcomes framework that includes community-determined outcomes and system indicators that demonstrate short-term, medium-term and long-term outcomes at system/ individual/ community levels through quantitative and qualitative data. | Leadership by the CEO and Director of Public Health - supported by strong belief or experience in community approaches. | The default position of traditional service provision, that requires shifting mindsets. |

| Strengthening communities’ capacity through community development approaches. | Neighbourhood level working that is hyper-local (walking distance). Place-based working linked to other agendas. | Centrality of local government elected members as community-centred enablers of change. | Balancing the differing goals of communities and services. Not losing sight of the importance of bottom-up community outcomes and sticking to these as key determinants/ protective factors for health. | |

| Community engagement and co-production - a new conversation (between public and agencies) and participative decision-making structures. | A high level shared narrative and commitment across all partners. | Access to finances - either start-up funding or through de-commissioning. | ||

| Action to address the social determinants of health within the locality for example, housing, employment, income/ debt, healthy place/ environment. | Recognition that a long-term approach is needed, supported by some initial freedom and flexibility to develop a community-informed approach. | A strategic level partnership across sectors demonstrating collective bravery and risk-taking. | ||

| Workforce development building core skills and knowledge in community-centred approaches. | Embedding community-centred approaches into all public health priorities and programmes. And an embedded approach to public health in all local government departments. and other partnerships, for example, Clinical Commissioning Groups. | Building on a history of active communities and community assets, including strong relationships and high levels of trust between communities and partners. | ||

| Community asset transfer that is timely and supported to meet community needs | Values driven by community empowerment and trusting relationships. | Social value commissioning |

NHS, National Health Service; VCS, voluntary and community sector.

Following presentation and discussion of the themes at the round-table meeting with stakeholders, they were grouped and regrouped into a practical framework focussing on the elements, principles and values of a whole system approach to community-centred public health which represented a good fit with the data. These findings are reported below. There was an additional output that covered descriptive themes on the suggested steps for those starting out on this journey (online supplementary file C).

bmjopen-2019-036044supp003.pdf (216.9KB, pdf)

Findings

Findings on the elements, principles and values for whole system community-centred public health are summarised in figure 1. In terms of findings on context, interviewees described two main starting points for this work. First, that health inequalities were getting worse within local areas and that leaders had consequently agreed that a radical approach was needed, aligned to redesign of services across the system. There was a recognition that what had been traditionally provided was not working. Second, interviewees reported the need to reduce demand on services due to diminishing resources and growing population need. An important context emerging from each evidence source was around austerity and the effect on people’s health, community strengths and vitality, and the impact of cuts to the services that were previously addressing these.

Figure 1.

Whole system approach to community-centred public health. (source: Public Health England, 2020, Community-centred public health: taking a whole system approach. Briefing of research findings https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/community-centred-public-health-taking-a-whole-system-approach). SDOH, social determinants of health; VCS, voluntary and community sector.

Elements of a whole system approach

Eleven elements, which were identified through analysis and are labelled (i) through to (xi), describe what needs to be delivered to achieve a whole system approach to community-centred public health—the core actions. These are grouped into four major themes—involving communities, strengthening capacity and capability, scaling practice and sustaining outcomes (figure 1).

Involving communities

Undertaking research with communities (especially the seldom heard) to gain insight from qualitative data to provide a rich understanding of people’s lives, public health needs and priorities (i. Community insight). This is often gathered by community researchers and has been the starting point for service or system redesign through providing compelling stories of people’s health and well-being. The literature also found that community involvement in research was an effective element.33–35

The existence of active communities was a key element of local systems, enabled where needed by community development, social action and support for grassroots approaches and community asset transfer (ii. Active communities).

Participation infrastructures are vital for ongoing engagement, co-production and participative decision-making, such as neighbourhood forums that bring agencies and community members together for developing joint action and long-term trusting relationships between and within communities, professionals and organisations (iii. Participation infrastructures). This was a strong theme in the literature; see for example.24 27–29

Strengthening capacity and capability

Strengthening capacity and capability included valuing the contribution of, and actively building the capacity of, the VCS through market development, facilitating collaboration and supporting volunteering (iv. Thriving VCS). The literature review also found that a capacity-building approach was effective, working with local community organisations, volunteers and community leaders.28 30–32

Workforce capability involved building the knowledge and skills of staff to create connected and empowered communities through community-centred ways of working (v. Workforce development) and embedding community-centred approaches into all public health, prevention and public service reform (vi. Embedded into core business). This included using levers such as commissioning for social value. One participant described:

taking a public health department approach so community-centred practice is part of everything we do. (Interviewee 11)

The literature specifically highlighted the tailoring of health education campaigns to community context and marginalised groups.30 33

Scaling practice

The scaling up of a range of community-centred prevention services and approaches as part of integrated commissioning between public health, social care and the National Health Service (NHS) (vii. Integrated community-centred approaches). Approaches commonly cited were social prescribing and community development, but these were aligned as part of a whole system way of working:

We’ve had a history of lots of initiatives that were community-oriented, but we’ve brought them together to make it whole system as part of transformational, co-productive, large-scale change. (Interviewee 3)

social prescribing as a system not an access route. (Interviewee 11)

Scale related to systematising approaches rather than applying a standard model everywhere. This often required a shift in investment as part of a redesign. Scale at a ‘hyper-local’ place level was important, through neighbourhood-based working and resources (viii. Hyper-local working and resources)—described as operating at walking distance for participants rather than on larger organisational footprints. The literature supports a focus on place with attention to cultural issues and addressing health inequalities.27 29 31 36

Sustaining outcomes

A whole system approach was sustained through having a strategic and long-term ambition for strengthening communities that was shared and communicated between agencies and communities (ix. Long-term joint strategy). This included social movement approaches and ways of forming new relationships between the public sector and the public. It also refers to aligning different agencies’ agendas where strengthening communities is central to their goals. The long-term nature of this work was recommended by all:

Don’t underestimate the time needed. Without this there is a tendency to revert to a service response rather than a change response. (Interviewee 8)

This was confirmed by the literature review which found developing a shared vision, community ownership and mobilisation as effective elements.37–40

Community insight informed a comprehensive outcomes framework based on the things that mattered to communities in the long term as well as the short-term and medium-term indicators of community-level determinants of health such as resilient, connected and empowered communities (x. Community outcomes framework). Relevant indicators were not always seen as included within current measurement or monitoring systems:

the PHOF [Public Health Outcomes Framework] is too disease focussed, not social capital. We need new measures of quality of life, not smoking anymore. (Interviewee 1).

It was difficult to set outcomes at the beginning as there was a tension between community interests and programme auditing. (Interviewee 12)

An essential element to the whole system approach was action to address the social determinants of health (SDOH), such as housing, poverty, employment, environment, crime and safety (xi. Addressing SDOH). These can be structural barriers or prerequisites for community resilience, participation and empowerment:

we need to change the environment at the same time—regeneration of place alongside regeneration of communities. (Interviewee 1).

Addressing the social determinants was also a priority from our public consultation32 as well as the literature.23 27 39

Values and principles

Attention to power ran throughout many of the 11 elements, referring to the centrality of power to inequalities, the differential power of partners and how these impact on empowerment. Alongside establishing trust and sustainable relationships, attention to power makes up the three values summarised at the centre of the framework (figure 1). These values were also supported by the literature35 37 41 42 and the supplementary evidence sources:

the power of a grassroots-driven strategy should not be considered ‘a challenge to authority’ but as a way to develop shared ownership of progress towards self-determined goals. (People’s survey finding).

there is often a reluctance to talk about where power lies, and this can only be done at a whole system level (round-table discussion).

The actions were underpinned by five principles for whole system working (box 3). These were commonly referred to as shifting from traditional ways of working. One interviewee referred to:

Box 3. Principles for achieving a whole system approach to community-centred public health.

Bold leadership to shift from traditional to radical approaches in order to reduce health inequalities. Leading an approach that is strategic, large-scale and creates transformational change.

Shifting mindsets and redesigning the system aligned to building healthy, resilient, active and inclusive communities.

Collective bravery for risk-taking action and a strong partnership approach across local government tiers and departments, communities, National Health Service and the voluntary and community sector, that gives attention to power and building trusting relationships with communities.

Co-production of solutions and different ways of working with communities, for example, social movements.

Recognising the complexity of the protective and risk factors at a community-level that affect people’s health and how these interact with the wider determinants of health.

going back to public health roots of community health development—we had been working at the wrong end. (Interviewee 1).

Another interviewee referred to the:

“need to understand and focus on the protective factors, recovery assets and resilience, not more on the risk factors, in order to understand what makes some people well while others living with the same levels of risk are ill.” (Interviewee 10).

Table 3 provides examples of how the elements and values are demonstrated in practice.

Table 3.

Examples of how the elements and values of whole system approaches to community-centred public health are demonstrated in practice.

| Element | Examples from practice (further information at https://phelibrary.koha-ptfs.co.uk/practice-examples/caba/wsa/) |

| Involving | Dudley Council’s community resilience journey started with gathering community stories for 6 months. This has shaped their whole system approach, including their strategic priorities and outcomes, social value measures and service commissioning frameworks. |

| Well-being Exeter is a robust partnership of public, VCS organisations working together, programme managed by Devon Community Foundation. It aims to support people on a journey from dependence on services, to increased involvement and interdependence within better connected, inclusive and more resilient communities. | |

| Get Oldham Growing is a community engagement programme focussed on improving social connections and action on the wider determinants of health. The aim is that ‘growing hubs’ in all six districts will be sustainable and community run, and this has already started through community interest companies and asset transfers. | |

| Strengthening | Small grassroots organisations in Bracknell Forest are given support to grow through seed funding, marketing and advice on diversity and inclusion. Public health staff have started working closely with community-led groups and doing community development to address social connectedness as an underlying cause of poor health. |

| Hull’s whole system community-centred approaches grew from initial ward-based work on smoking cessation to being central to their whole-public health approach, delivered through community-centred public health commissioning, strengthening of the VCS’ role and strategic alignment across the system, for example, a refreshed city plan committed to addressing inequality by achieving fair, inclusive economic growth. | |

| In Blackburn with Darwen, reductions in access to social support underpin widening health inequalities. Their approach was to build distributed leadership for public health across all departments, sectors and organisations, including neighbourhood-based working to build a social movement approach to public support and social action for change. | |

| Scaling | North Yorkshire re-designed their prevention service in partnership with the VCS, social care and primary care. It is now a more holistic community-oriented service, linking prevention to social work and living well coordinators in local doctor’s practices. |

| Tower Hamlets ‘communities driving change’ initiative is whole system working at the neighbourhood level, working with 12 small neighbourhoods (estates) and their residents to improve the availability of good and better things, resulting in more community-oriented local services and better addressing social determinants. | |

| Sustaining | A priority in East Sussex to develop a whole system approach to community resilience has led to partners working together on a ‘personal and community resilience programme’ with several shared objectives. Sustainability is being achieved through improving communities’ capacity to come together to tackle local issues that matter to them most, supporting business to deliver social value and increasing knowledge of community-centred ways of working. |

| Wirral is working to make everything more community-centred. Community connectors address the social determinants of health and residents are at the centre of work around the environment, licensing, housing conditions, environmental health and education, through a Wirral Together partnership. Efforts to improve the physical environment are happening at the same time as strengthening communities; ‘regeneration of place alongside regeneration of communities’. | |

| Values | Understanding power and empowerment is core to the Gateshead approach, as this is critical to reducing inequalities. Often, disadvantaged groups lack both a voice and confidence because they have been disempowered by the systems around them. Gateshead’s approach is to support people in the knowledge that they have a voice and a right to be listened to. Professional practice is shifting to a bottom-up approach, working with communities through community development approaches and ensuring that the resulting public health activity is owned by communities. |

VCS, voluntary and community sector.

Discussion

I’ve never found a single public health issue more powerful than community development to enable a system-wide approach. (Director of Public Health, Interviewee 2)

To reduce widening health inequalities, communities need to be at the heart of public health practice. Community control, neighbourhood belonging and social connectedness are determinants of health that are influenced by social conditions and can be addressed through local action.2 9 11 Those interviewed recognised the need for a whole system approach to do this and were actively working towards this. What they were doing and how is summarised in the 11 elements, 3 values and 5 principles (figure 1). The need to scale whole system approaches where communities are central to public health has been recognised elsewhere.21 23 43 Research in England has found fragmented local systems44 despite a pressing need to reshape service delivery through close partnership working with local organisations. Furthermore, people and communities experience outcomes that are influenced by the whole system around them.45 That a level of need requires a radical approach is also recognised,45 46 especially when inequalities have been widening.5 Research in Chicago turned the problem around: from asking how community organisations could be more involved in system approaches to population health, to concluding that health systems should be asking how they can be more involved in community-based approaches already underway.47

The depth of practice across the sites suggest that whole system working to build healthy communities is feasible and possible for wider adoption within other public health systems. Most interviewees were able to report outcomes and there was a range of approaches used or planned by all to evaluate impact. Community determinants of heath and community outcomes remain challenging factors to measure and this is an area where more work is needed. The elements that were strongest in all our evidence sources were the need to co-produce, identify needs and share decision-making with communities.

A focus on cultural issues was found in the literature34 38 48 but not highlighted in our findings, although could be understood by the need to work at a ‘hyper-local’ neighbourhood level (element viii). Approaches that address gender or race discrimination in North American contexts were effective in strengthening community networks and coalitions,35 42 which we did not explore. Community-based participatory research (CBPR) was also not as well developed in our English examples as in the international literature. Both CBPR and a whole system focus on discrimination could present areas for development.

At the round-table discussion, the value of describing the work as ‘whole system’ or ‘scaling’ was debated. Many of the elements could be seen as already part of a community-centred approach.2 The adoption of whole system and complex system approaches to address public health priorities is a growing area of research and practice.18 19 Recognising the importance of multiple inter-related determinants is an important feature. This was exemplified in the local work where community empowerment and capacity building were done alongside inclusive economic growth, housing improvement, regeneration of place, licensing, education improvement, poverty reduction and community safety. This study contributes an understanding of how to develop a community-centred approach to public health whole system working.

While the research focussed on whole systems, the interviews were limited to a public health focus. Further research with leaders from other sectors that are increasingly leading population health and prevention could strengthen the place-based approach and transferability of findings to other sectors. The inclusion of community voice was limited to the people’s panel and representatives of the VCS. Voices from disadvantaged communities was limited to professional perspectives drawing on their local insight working in those areas. The next stage of the work involves testing the findings with local sites, including community members. Appraisal of the perspectives, values, principles and language adopted will strengthen the findings and its transferability. The focus in this study on creating a supportive infrastructure for working with communities should be used alongside methods, such as CBPR, that develop deep, long-term work with communities dealing with power imbalances.

The English context for the research may limit transferability to other countries, although inclusion of international literature may strengthen this. Many of the results map to themes raised in other whole systems literature. What this study contributes is an understanding of the range of approaches used by local public health leaders to work with local communities.

The authors note their position in a national government agency limits their scope. The work is with intermediate stakeholders rather than local communities and, as such, the emphasis is on re-orienting ‘top-down’ ways of working to complement ‘bottom-up’ community empowerment efforts.12 This acknowledges that action needs to take place around organisational development and creating a supportive infrastructure as well as community development.13 41 The inclusion of public voice via the PHE People’s Panel is subject to bias and not likely to be representative of disadvantaged communities. Further in-depth research with communities experiencing disadvantage would be beneficial. An accessible community engagement system would support this. The context of wider national government approaches impacting on social conditions, such as austerity measures, may overshadow other efforts. Further research is needed to understand the impact and limits that a community-centred public health system has on health inequalities within a wider socioeconomic context.

Conclusion and recommendations

Local public health leaders are in a strong position to develop a whole system approach to reduce health inequalities that puts communities at its heart. The findings summarise current practice and provide a practical guide to taking a whole system approach to community-centred public health. While this is developed within North American literature, there is little UK research in this area.

The elements, values and principles (figure 1) could be applied by local areas to (1) improve the effectiveness and sustainability of action to build healthy communities, or (2) embed community-centred ways of working within whole systems action to improve population health. The findings could be tested as a framework for taking a whole-approach to community-centred public health.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank all participants in the study; the local staff who gave their time for interviews, the members of PHE’s people’s panel who completed the survey and the participants and partners who attended the round-table discussion. Thanks to Public Health England's (PHE) Knowledge and Libraries Services and PHE colleagues who were on the project steering group, and especially to our external adviser Dave Buck from the Kings Fund. Thanks to Jo Trigwell, Charlotte Freeman and James Woodall, Centre for Health Promotion Research, Leeds Beckett University, who undertook the initial analysis of the survey data.

Footnotes

Twitter: @JudeStansfield

Contributors: JSt and JSo designed the study, conducted interviews, and discussed and finalised the paper. JSt undertook the interview analysis and produced the first draft of the findings and paper. JSo reviewed the literature and supported the public survey data analysis. TM arranged the interviews, round-table discussion, and reviewed the findings and final paper.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: Ethical approval was submitted to the organisation but was not required for this study.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer-reviewed.

Data availability statement: No data are available. The interview and survey data are not available due to information governance restrictions. The practice examples are in the public domain at https://phelibrary.koha-ptfs.co.uk/practice-examples/caba/wsa/

References

- 1.South J, Bagnall A-M, Stansfield JA, et al. An evidence-based framework on community-centred approaches for health: England, UK. Health Promot Int 2019;34:356–66. 10.1093/heapro/dax083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Public Health England, NHS England . “A guide to community-centred approaches for health and wellbeing,”. London: Public Health England, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stansfield J, South J. A knowledge translation project on community-centred approaches in public health. J Public Health 2018;40:i57–63. 10.1093/pubmed/fdx147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iacobucci G. Life expectancy gap between rich and poor in England widens. BMJ 2019;364:l1492. 10.1136/bmj.l1492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marmot M, Allen J, Boyce T, et al. “Health equity in England: The Marmot Review 10 years on,”. London: Institute of Health Equity, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kriznik NM, Kinmonth AL, Ling T, et al. Moving beyond individual choice in policies to reduce health inequalities: the integration of dynamic with individual explanations. J Public Health 2018;40:764–75. 10.1093/pubmed/fdy045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Association LG “Public health transformation five years on: transformation in action.,”. London: LGA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization Community development in local health and sustainable development approaches and techniques. Europe, Geneva: WHO Regional Office, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 9.The Marmot Review “Fair Society Healthy Lives.,” The Marmot Review. London, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wallerstein N. Empowerment to reduce health disparities. Scand J Public Health Suppl 2002;59:72–7. 10.1177/14034948020300031201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stansfield J, Bell R. Applying a psychosocial pathways model to improving mental health and reducing health inequalities: practical approaches. Int J Soc Psychiatry 2019;65:107–13. 10.1177/0020764018823816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laverack G, Labonte R. A planning framework for community empowerment goals within health promotion. Health Policy Plan 2000;15:255–62. 10.1093/heapol/15.3.255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.NICE “Community engagement: improving health and wellbeing and reducing health inequalities NICE guideline NG44. London: NICE, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Friedli L. What we've tried, hasn't worked': the politics of assets based public health,”. Critical Public Health 2013;23:131–45. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rolfe S. Governance and governmentality in community participation: the shifting sands of power, responsibility and risk. Social Policy and Society 2018;17:579–98. 10.1017/S1474746417000410 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Douglas JA, Grills CT, Villanueva S, et al. Empowerment praxis: community organizing to Redress systemic health disparities. Am J Community Psychol 2016;58:488–98. 10.1002/ajcp.12101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.The Health Foundation “Evidence scan: complex adaptive systems”. The London Health Foundation, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rutter H, Savona N, Glonti K, et al. The need for a complex systems model of evidence for public health. Lancet 2017;390:2602–4. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31267-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bagnall A-M, Radley D, Jones R, et al. Whole systems approaches to obesity and other complex public health challenges: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 2019;19:8. 10.1186/s12889-018-6274-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Public Health England “A whole systems approach to obesity,”. London: Public Health England, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Buck D, Baylis A, Dougall D. A vision for population health: towards a healthier future. London: The Kings Fund, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 22.South J, Connolly AM, Stansfield JA, et al. Putting the public (back) into public health: leadership, evidence and action. J Public Health 2019;41:10–17. 10.1093/pubmed/fdy041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cohen L. Building a thriving nation: 21st-century vision and practice to advance health and equity. Health Educ Behav 2016;43:125–32. 10.1177/1090198116629424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.World Health Organization., Health in all policies Helsinki Statement. Framework for country action. 2014 World Health Organization, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Public Health England Place-based approaches for reducing health inequalities. London: Public Health England, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ritchie J, Lewis J. Qualitative research practice.A guide for social science students and researchers. London: Sage, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sims J, Aboelata MJ. A system of prevention: applying a systems approach to public health. Health Promot Pract 2019;20:476–82. 10.1177/1524839919849025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thomas J, Newman M, Oliver S. Rapid evidence assessments of research to inform social policy: taking stock and moving forward. Evid Policy 2013;9:5–27. 10.1332/174426413X662572 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.South J, Stansfield J, Wilkinson E, et al. Whole system community-centred public health: list of resources. London: Public Health England, 2020. https://phelibrary.koha-ptfs.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/27/2019/10/Supporting-WS-working-UK-tools-and-frameworks-v2.pdf, [Google Scholar]

- 30.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006;3:77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, et al. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol 2013;13:117. 10.1186/1471-2288-13-117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Trigwell J, Freeman C, Woodall J, et al. Analysis of the People’s Panel Healthy Communities Consultation.,” in Public Health England 2019 Conference, Warwick University, 11-12th September 2019. Warwick, 2019. http://eprints.leedsbeckett.ac.uk/6639/ [Google Scholar]

- 33.Amed S, Shea S, Pinkney S, et al. Wayfinding the live 5-2-1-0 Initiative-At the intersection between systems thinking and community-based childhood obesity prevention. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2016;13:ijerph13060614. 10.3390/ijerph13060614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schulz AJ, Zenk S, Odoms-Young A, et al. Healthy eating and exercising to reduce diabetes: exploring the potential of social determinants of health frameworks within the context of community-based participatory diabetes prevention. Am J Public Health 2005;95:645–51. 10.2105/AJPH.2004.048256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Khare MM, Núñez AE, James BF. Coalition for a healthier community: lessons learned and implications for future work. Eval Program Plann 2015;51:85–8. 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2015.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jones D, Louis C. State population health strategies that make a difference: project summary and findings. New York: Milbank Memorial Fund, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kegler MC, Painter JE, Twiss JM, et al. Evaluation findings on community participation in the California healthy cities and communities program. Health Promot Int 2009;24:300–10. 10.1093/heapro/dap036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mead EL, Gittelsohn J, Roache C, et al. A community-based, environmental chronic disease prevention intervention to improve healthy eating psychosocial factors and behaviors in Indigenous populations in the Canadian Arctic. Health Educ Behav 2013;40:592–602. 10.1177/1090198112467793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wagenaar AC, Gehan JP, Jones-Webb R, et al. Communities mobilizing for change on alcohol: lessons and results from a 15-community randomized trial. J Community Psychol 1999;27:315–26. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schwarte L, Samuels SE, Capitman J, et al. The central California regional obesity prevention program: changing nutrition and physical activity environments in California's heartland. Am J Public Health 2010;100:2124–8. 10.2105/AJPH.2010.203588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cheadle A, Hsu C, Schwartz PM, et al. Involving local health departments in community health partnerships: evaluation results from the partnership for the public's health Initiative. J Urban Health 2008;85:162–77. 10.1007/s11524-008-9260-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liao Y, Tsoh JY, Chen R, et al. Decreases in smoking prevalence in Asian communities served by the racial and ethnic approaches to community health (reach) project. Am J Public Health 2010;100:853–60. 10.2105/AJPH.2009.176834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Elwell-Sutton T, Tinson A, Greszczuk C, et al. “Creating healthy lives: A whole-government approach to long-term investment in the nation's health,”. London: The Health Foundation, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Locality “Powerful communities, strong economies.,” Locality. London, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Knight A, Lowe T, Brossard M. A whole new world: funding and commissioning in complexity. Newcastle: Collaborate CIC, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lent A, Studdert J. The community paradigm: why public services need radical change and how it can be achieved. London: New Local Government Network, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tung EL, Gunter KE, Bergeron NQ, et al. Cross-Sector collaboration in the High-Poverty setting: qualitative results from a community-based diabetes intervention. Health Serv Res 2018;53:3416–36. 10.1111/1475-6773.12824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Larson CO, Schlundt DG, Patel K, et al. Trends in smoking among African-Americans: a description of Nashville's reach 2010 initiative. J Community Health 2009;34:311–20. 10.1007/s10900-009-9154-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-036044supp001.pdf (47.9KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-036044supp002.pdf (172.5KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-036044supp003.pdf (216.9KB, pdf)