Abstract

Invasive mechanical has been associated with high mortality in COVID-19. Alternative therapy of high flow nasal therapy (HFNT) has been greatly debated around the world for use in COVID-19 pandemic due to concern for increased healthcare worker transmission. This was a retrospective analysis of consecutive patients admitted to Temple University Hospital in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, from 10 March 2020 to 24 April 2020 with moderate-to-severe respiratory failure treated with HFNT. Primary outcome was prevention of intubation. Of the 445 patients with COVID-19, 104 met our inclusion criteria. The average age was 60.66 (+13.50) years, 49 (47.12 %) were female, 53 (50.96%) were African-American, 23 (22.12%) Hispanic. Forty-three patients (43.43%) were smokers. Saturation to fraction ratio and chest X-ray scores had a statistically significant improvement from day 1 to day 7. 67 of 104 (64.42%) were able to avoid invasive mechanical ventilation in our cohort. Incidence of hospital-associated/ventilator-associated pneumonia was 2.9%. Overall, mortality was 14.44% (n=15) in our cohort with 13 (34.4%) in the progressed to intubation group and 2 (2.9%) in the non-intubation group. Mortality and incidence of pneumonia was statistically higher in the progressed to intubation group.

Conclusion

HFNT use is associated with a reduction in the rate of invasive mechanical ventilation and overall mortality in patients with COVID-19 infection.

Keywords: viral infection, respiratory infection

Introduction

In December 2019, a cluster of acute respiratory illnesses occurred in Hubei province, China, now known to be caused by a novel coronavirus, also known as SARS-CoV-2. It has spread globally since with more than 2 million cases reported as of April 2020.1 2 Severe hypoxaemic respiratory failure is by far the most common reason for admission to intensive care units (ICUs) due to COVID-19. In a report from Lombardi, Italy, of 1591 critically ill patients with COVID-19, 99% required respiratory support of at least supplemental oxygen and 88% (or 1150 patients) required invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV).3 Another retrospective review of Wuhan hospitalised patients, including patients without COVID-19, showed 52% required respiratory support, of which 55% needed mechanical ventilation.4 Mortality of patients with COVID-19 on IMV has been reported to in the range of 61%–96% in Italy, China and New York.3–5

High flow nasal therapy (HFNT) is a non-invasive oxygen delivery system that allows for administration of humidified air-oxygen blends as high as 60 L/min and a titratable fraction of inspired oxygen as high as 100%. HFNT has shown effectiveness in other severe viral respiratory illnesses like influenza A and H1N1.6 Use of HFNT has led to lower progression to invasive ventilation compared with other forms of non-invasive oxygen therapy.7–9 By decreasing the incidence of invasive ventilation, HFNT has the potential advantage of theoretically decreasing the incidence of ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP), as well as reduction in hospital resources which can be critical during times of increasing strain on the healthcare system. When compared with non-invasive ventilation (NIV), the use of HFNT is associated with similar rates of reintubation due to postextubation respiratory failure.10 However, no short-term mortality benefit has been reported using HFNT to treat acute hypoxaemic respiratory failure.7 11 12

The Surviving Sepsis Guidelines for COVID-19 recommends using HFNT in patients with acute hypoxaemic respiratory failure due to COVID-19.13 However, others recommend against using HFNT fearing that it will create aerosolisation of the COVID-19 virus and increase transmission to healthcare providers.14–16 In the few case series that report HFNT use in patients with COVID-19, its usage has ranged from 4.8% to 63.5%.17–20 In a recent report of patients who succumbed to COVID-19 in China, 34.5% were placed on HFNT alone; the authors postulated that use of HFNT may have contributed to a delay in intubation thereby increasing mortality.21

Herein, we present a retrospective analysis of the outcomes of patients with COVID-19 with moderate-to-severe hypoxaemic respiratory failure receiving HFNT at our centre.

Methods

Patient and public involvement

Patients or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of our research.

Design

This was a retrospective analysis of consecutive patients admitted to Temple University Hospital in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, from 10 March 2020 to 24 April 2020, for moderate-to-severe hypoxaemia due to highly suspected or proven COVID-19 infection. Patients who presented to our hospital with fever or acute respiratory symptoms of unknown aetiology were screened for COVID-19 infection. Patients included in analysis were those that tested positive for COVID-19 using nasopharyngeal real-time reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) or patients with high clinical suspicion and findings suggestive of COVID-19 based on high-resolution CT of the chest (typical peripheral nodular or ground glass opacities without alternative cause22 23 with typical inflammatory biomarker profile).

Data including demographics, age, sex, comorbidities, body mass index (BMI), smoking status (current smoker, non-smoker), admission laboratory data including complete blood count with differential, ferritin, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), D-dimer and C reactive protein (CRP), treatments offered were collected for all of these patients. We also collected oxygen saturation to fraction of inspired oxygen ratio (SF ratio) on day of HFNT initiation, at day 7 after HFNT initiation or at discharge, whichever came earlier. SF was used as a surrogate for partial pressure of oxygen/fraction of inspired oxygen (PF ratio) as they have been correlated well in clinical trials.24

Radiology

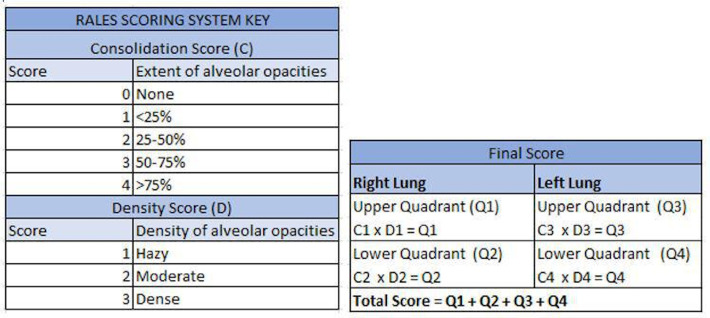

Chest X-rays (CXRs) were graded by senior pulmonary and critical care fellows according to the Radiographic Assessment of Lung Edema Score (RALES) grading system grading system (figure 1) previously studied in acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and organ donors.25 CXRs were graded on the day of initiation of HFNT and earlier of discharge day or day 7.

Figure 1.

Radiographic Assessment of Lung Edema Score (RALES) grading system for chest X-ray.

Respiratory therapy

All patients included in the analysis had moderate-to-severe hypoxaemic respiratory failure and were on oxygen delivery via HFNT during the hospital course. Moderate-to-severe hypoxaemic respiratory failure was defined as any patient requiring >15 L/min of oxygen via nasal cannula. Receipt of any other form of respiratory support initially was considered as exclusion criteria for the study. As an institutional policy, HFNT was preferred over NIV/IMV and was maintained indefinitely if oxygenation, ventilation and work of breathing parameters were acceptable. The decision to switch to NIV or IMV was at the discretion of the clinical care team. HFNT was provided with a humidified air-oxygen blend usually starting at 35 L/min with immediate titration to 20–60 L/min per patient comfort; the fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) was adjusted to maintain oxygen saturations>94%; further adjustments were made based on patients’ tolerance and goals of oxygenation. The initial temperature for the high flow setup was 37°C and was titrated between 34°C and 37°C for patient comfort. Data on initial oxygenation support were collected which included the flow of air-oxygen blend in litres per minute and fractional percentage of inspired oxygen.

Outcomes

Our primary outcome was the prevention of IMV (%) with use of HFNT. Our secondary outcomes were mortality, change in SF ratio, change in RALES of CXR, hospital length of stay (LOS) and hospital-acquired/ventilator-acquired pneumonia. Hospital-acquired and ventilator-acquired pneumonia was defined based on the presence of sputum positivity and treatment with antibiotics. Changes in SF ratio were calculated by difference between SF ratio at day 7 or discharge (whichever was earlier) versus day 1.

HFNT patients were divided into two groups: 1) progression to IMV (ie, intubation group) and 2) continued HFNT support (ie, non-intubation group). Patients who required NIV are reported in the non-intubation group. Comparison was made between demographics, baseline laboratory values and outcomes within the two groups. Improvements/worsening in oxygenation at day 7 and change in clinical parameters of heart rate and respiratory rate were also analysed.

We constructed a prediction model for intubation for our cohort. All comorbidities, demographics, clinical and laboratory data were used to investigate parameters that could predict need for intubation. A cumulative comorbidity score (1 point allocated for each of the five comorbidities reported) and cumulative inflammatory laboratory marker score (1 point for each abnormal lab) were tested as predictors of intubation.

Statistical methods

Continuous variables are presented as means (±SD), and categorical variables as numbers and frequency (percentages). Continuous variables were compared with the use of the two-sample t-test or paired t-test for categorical variables with the use of the Pearson’s χ2 test. Laboratory data were non-parametric and compared using Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Kaplan-Meier analysis was estimated for survival and compared by log-rank test.

To build a predictive model of the intubation, multivariable logistic regression was performed to determine the adjusted associations of the variables with intubation. The initial model included all the variables associated with intubation in univariate analyses for p<0.1. The final model that optimised the balance of the fewest variables with good predictive performance. Assessment of model performance was based on discrimination and calibration. Discrimination was evaluated using the C-statistic, which represents the area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve, where higher values represent better discrimination. Calibration was assessed by the Hosmer-Lemeshow test, where a p value >0.05 indicates adequate calibration.

All statistical tests were two-tailed, and p values <0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance. All statistical analyses were performed with the use of Stata V.14.0 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA).

Results

Patient population

Eight hundred ninety-four patients admitted to Temple University Hospital between 10 March 2020 and 24 April 2020 who had suspected COVID-19 infection were retrospectively screened for our study. Four hundred forty-five patients had tested positive for COVID-19 by nasopharyngeal RT-PCR or were treated for high clinical suspicion based on typical CT imaging and inflammatory biomarker profile.

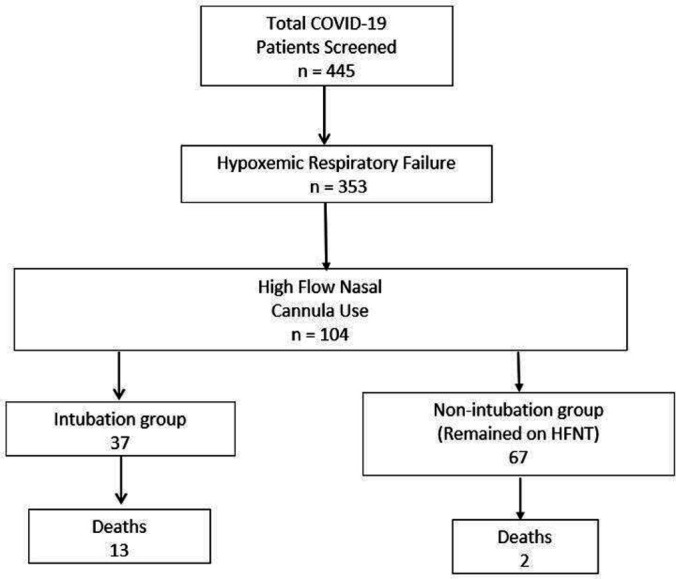

Of the 445 patients, 353 patients had hypoxaemic respiratory failure requiring some form of oxygen therapy. The level of oxygen ranged from 2 L/min of oxygen via simple nasal cannula to requiring IMV and 100% oxygen. One hundred four (23.3% of all COVID-19-positive patients) met our inclusion criteria of having moderate-to-severe COVID-19-related hypoxaemic respiratory failure and were treated with HFNT (figure 2). The reported hypoxaemia was moderate-to-severe with mean SF ratio of 121.9 (range 79–225). Higher CXR RALES were associated with more severe SF ratios.

Figure 2.

Flow chart demonstrating screening for our patients. HFNT, high flow nasal therapy.

The average age was 60.66 (±13.50) years, 49 (47.12 %) were female, 53 (50.96%) were African-American, 23 (22.12%) Hispanic. Forty-three patients (43.43%) were smokers. The major comorbidities reported (in descending incidence) were hypertension, diabetes, lung disease, heart disease and chronic kidney disease (CKD) (table 1). Nine (9.78%) patients were also on haemodialysis. Baseline SF ratios were severely low at 121.9, corresponding to a PF ratio of ~100. Elevated inflammatory markers (ie, ferritin, CRP, D-dimer, fibrinogen, LDH, interleukin (IL)-6), creatinine along with transaminitis and lymphopenia were observed in all patients. In terms of treatments, azithromycin (57.2%) and steroids (64.71%) were the most frequently used therapies. Immunomodulators like sarilumab, anakinra, intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) and tocilizumab were the next most used therapies.

Table 1.

Demographics data including laboratory and clinical parameters

| Demographics | n=104 |

| Age (years, mean±SD) | 60.66 (±13.50) |

| Sex (F) n (%) | 49 (47.12 %) |

| BMI* kg/m2 (mean±SD) | 32.14 (±7.80) |

| Comorbidities n (%) | |

| Hypertension | 46 (45.10%) |

| Diabetes | 35 (34.65%) |

| Lung Dx | 31 (30.69%) |

| Heart Dx | 23 (22.55%) |

| CKD | 15 (16.3%), 9 (9.78%) on HD |

| Race | |

| African-American | 53 (50.96%) |

| Hispanic | 23 (22.12%) |

| Caucasian | 9 (8.65%) |

| Other | 4 (3.85%) |

| Unknown | 15 (14.42%) |

| Smoking n (%) | |

| No | 51 (51.52%) |

| Yes | 43 (43.43%) |

| Initial vitals | |

| Heart rate (mean±SD) bpm | 98.0 (±20.17) |

| Respiratory rate (mean±SD) bts/min | 22.03 (±5.47) |

| Temperature (mean±SD) °F | 99.4 (±2.18) |

| Pulse oximetry (mean±SD) % | 89.9 (±10.09) |

| Laboratory abnormalities mean (±SD) | |

| Ferritin (ng/mL) | 1216.0 (±2790.6) |

| CRP* (mg/dL) | 11.77 (±8.38) |

| LDH* (U/L) | 452.06 (±292.36) |

| D-dimer (ng/mL) | 5659.6 (±17267.49) |

| Fibrinogen (mg/dL) | 490.23 (±178.44) |

| Lymphocyte count (K/mm3) | 1.02 (±0.54) |

| IL-6 (pg/mL) | 82.5 (±149.54) |

| AST (U/L) | 56.8 (±74.90) |

| ALT (U/L) | 38.6 (±31.93) |

| Platelets (K/mm3) | 221.7 (±106.19) |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 186.7 (±253.78) |

| BUN (mg/dL) | 28.4 (±24.07) |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 2.61 (±3.95) |

| Treatments | |

| Remdesivir | 9 (9.68%) |

| Sarilumab | 40 (39.22%) |

| Anakinra | 12 (11.76%) |

| Tocilizumab | 6 (5.88%) |

| Etoposide | 1 (0.97%) |

| IVIG | 19 (18.63%) |

| Pulse steroids | 66 (64.71%) |

| Hydroxychloroquine | 22 (21.57%) |

| Azithromycin | 59 (57.2%) |

| Antibiotics | 76 (73.08%) |

ALT, alanine transaminase; AST, aspartate transaminase; bpm, beats per min; bts/min, breaths per min; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; CKD, chronic kidney disease; CRP, C reactive protein; Dx, diagnosis; F, Fahrenheit; HD, haemodialysis; IL-6, interleukin 6; IVIG, intravenous immunoglobulin; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase.

HFNT details

One hundred four (23.3%) of 445 COVID-19-positive patients required HFNT support. Initial HFNT settings were 31.8 (±9.17) L/min of flow, while fractional of inspired oxygen (FiO2) was 90% (±16.7, range: 30%–100%). The average use of HFNT for our population was 4.58 days (±3.28). The minimum settings on HFNT were 10 L flow and FiO2 of 30%, while the maximum settings were 60 L and FiO2 of 100%. Forty-five (43.2%) of patients receiving HFNT progressed to IMV or NIV. The incidence of hospital-associated pneumonia on HFNT was 2.94%. Two patients were excluded from analysis due to short follow-up.

Use of high flow for liberation from mechanical ventilation (IMV+NIV)

Eleven of the IMV patients were successfully extubated to high flow with no re-intubations in this subgroup. Six of the eight patients on NIV were successfully liberated from NIV with the use of HFNT.

Outcomes

The SF ratio significantly improved from 123.5 (±42.25) to 234.5 (±120.79) from day 1 to day 7. CXR score improved from 18.17 (±7.87) to 16.13 (±8.79) (p=0.033), heart rate decreased from 88.2 (±17.13) to 75.7 (±23.13) (p=0.0004) and respiratory rate improved from 29.71 (±18.99) to 26.38 (±16.93) (p=0.0001) (table 2). Sixty seven of 104 (64.42%) were able to avoid IMV in our cohort. Overall, 45 patients required mechanical ventilation, of which 37 (35.58%) required IMV and 8 patients (7.69 %) required NIV.

Table 2.

Outcomes of patients treated with HFNT

| Outcomes | Total (n=104) | P value | |

| Prevention of intubation | 67 (64.42%) | ||

| Intubation rate | 37 (35.58%) | ||

| Mortality | 14.44% (n=15) | ||

| Hospital LOS | 10.96 days (±6.04) | ||

| ICU LOS | 6.55 days (±5.31) | ||

| HAP/VAP incidence | 3 (2.94%) | ||

| Day 0 | Day 7–10 | ||

| SF ratio | 123.5 (±42.25) | 234.5 (±120.79) | <0.0001 |

| CXR RALES | 18.17 (±7.87) | 16.13 (±8.79) | 0.033 |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 88.2 (±17.13) | 75.7 (±23.13) | 0.0004 |

| Respiratory rate (breaths/min) | 29.71 (±18.99) | 26.38 (±16.93) | 0.0001 |

CXR, chest X-ray; HAP, hospital-associated pneumonia; ICU, intensive care unit; LOS, length of stay; RALES, Radiographic Assessment of Lung Edema Score; SF ratio, saturation to fraction ratio; VAP, ventilator-associated pneumonia.

Overall, mortality was 14.44% (n=15) in our cohort with 13 (34.4%) in the intubation group and 2 (2.9%) in the non-intubation group. Both the deaths in the non-intubation group were patients transitioned to comfort-directed care. Lastly, 10 of the 13 deaths were related to non-pulmonary organ failure and complications.

As of this writing, 48 patients from the HFNT group were discharged from the hospital with LOS 10.9 days (±6.04). ICU LOS for the 38 patients discharged from ICU was 6.55 days (±5.31). ICU LOS was higher for the intubation group (10.45 days±6.12 vs 4.05 ± 2.64 days, p=0.0008).

Intubation versus non-intubation (continued HFNT) group

The average duration of high flow use was higher in the non-intubation group (5.38±3.31 days vs 3.11±2.70 days, p=0.0023). There were no statistically significant differences between the intubation and non-intubation groups in terms of demographics (age, sex, BMI, most comorbidities, smoking). Hypertension and smoking prevalence were higher in the intubation group. Among laboratory markers, ferritin, LDH and fibrinogen was higher in the non-intubation group while triglycerides, IL-6, aspartate transaminase, D-dimer blood urea nitrogen and creatinine were higher in the intubation group (table 3). SF ratios were significantly different between the two groups at baseline, with the intubation group having much lower SF ratios compared with those who remained on HFNT (111.03±34.09 vs 127.9+43.47, p=004). There was greater improvement in SF ratio and CXR score (figure 3) in the non-intubation group (table 4). Patients in the intubation group had higher tocilizumab use, whereas anakinra, IVIG and antibiotics were more common in the non-intubation group.

Table 3.

Comparing demographics data between intubation and non-progression groups

| Demographics | Intubation (n=37) | Non-intubation (n=67) | P value |

| Age (years, mean±SD) | 63.9 (±11.67) | 58.9 (±14.17) | 0.06 |

| Sex (F) n (%) | 16 (43.24 %) | 33 (49.25 %) | 0.55 |

| BMI kg/m2 (mean±SD) | 31.0 (±6.74) | 32.8 (±8.33) | 0.27 |

| Comorbidities n (%) | |||

| Diabetes | 12 (33.33%) | 23 (35.38%) | 0.84 |

| Hypertension | 21 (56.76%) | 25 (38.46%) | 0.07 |

| Lung Dx | 14 (38.89%) | 17 (26.15%) | 0.18 |

| Heart Dx | 10 (27.03%) | 13 (20.00%) | 0.41 |

| CKD | 7 (21.21%) | 8 (13.56%) | 0.34 |

| Chronic haemodialysis | 4 (12.12%) | 5 (8.47%) | 0.57 |

| Race | |||

| African-American | 18 (48.65%) | 35 (52.24%) | 0.192 |

| Hispanic | 8 (21.62%) | 15 (22.62%) | |

| Caucasian | 6 (16.22%) | 3 (4.48%) | |

| Other | 0 | 4 (5.97%) | |

| Unknown | 5 (13.51%) | 10 (14.93%) | |

| Smoking* n (%) | |||

| No | 15 (41.67%) | 36 (57.14%) | 0.19 |

| Yes | 18 (50.00%) | 25 (39.68%) | |

| Initial vitals | |||

| HR (mean±SD) | 97.32 (±21.98) | 98.3 (±19.24) | 0.80 |

| RR (mean±SD) | 21.49 (±6.11) | 22.3 (±5.09) | 0.45 |

| Temperature (mean±SD) | 99.2 (±2.54) | 99.6 (±1.95) | 0.36 |

| Pulse oximetry (mean±SD) | 89.2 (±12.30) | 90.4 (±8.67) | 0.58 |

| Laboratory abnormalities | |||

| Mean (±SD) | |||

| Ferritin (ng/mL) | 1078.2 (±1720.37) | 1290.5 (±3236.69) | 0.59 |

| CRP (mg/dL) | 12.51 (±10.02) | 11.35 (±7.38) | 0.90 |

| LDH (U/L) | 444.51 (±322.57) | 463.4 (±244.33) | 0.58 |

| D-dimer (ng/mL) | 9241.76 (±24519.18) | 3604.36 (±10938.11) | 0.36 |

| Fibrinogen (mg/dL) | 430.9 (±205.05) | 523.64 (±153.66) | 0.009 |

| Abs Lymph Ct (K/mm3)* | 1.05 (±0.43) | 1.00 (±0.50) | 0.39 |

| IL-6 (pg/mL) | 130.9 (±210.15) | 42.6 (±48.07) | 0.12 |

| AST (U/L) | 69.2 (±112.06) | 48.6 (±32.45) | 0.90 |

| ALT (U/L) | 39.78 (±43.54) | 37.85 (±22.89) | 0.51 |

| Platelets (K/mm3) | 215.2 (±115.74) | 225.5 (±101.02) | 0.60 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 293.96 (±454.58) | 145.26 (±75.86) | 0.52 |

| BUN (mg/dL) | 31.95 (±21.86) | 26.32 (±25.24) | 0.08 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 2.88 (±3.58) | 2.46 (±4.15) | 0.09 |

| Treatments | 5 (13.89%) | 4 (7.02%) | 0.27 |

| Remdesivir trial* | 12 (33.33%) | 28 (42.42%) | 0.36 |

| Sarilumab trial† | 0 | 12 (18.18%) | 0.006 |

| Anakinra | 5 (13.89%%) | 1 (1.52%) | 0.011 |

| Tocilizumab | 1 (2.70%) | 0 | 0.18 |

| Etoposide | 11 (30.56%) | 8 (12.12%) | 0.02 |

| IVIG | 26 (72.22%) | 40 (60.61%) | 0.24 |

| Pulse steroids | 6 (16.67%) | 16 (24.24%) | 0.37 |

| Hydroxychloroquine | 12 (41.38%) | 22 (61.1%) | 0.30 |

| Azithromycin | 24 (64.86%) | 15 (22.39%) | 0.16 |

| Antibiotics |

*Smoking—current vs former/non-smokers. NCT04292899 and NCT04292899.

Abs Lymph Ct, absolute lymphocyte count; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; BMI, body mass index; BUN, blood urea Nitrogen; CKD, chronic kidney disease; CRP, C reactive protein; Dx, diagnosis; HD, haemodialysis; IL-6, interleukin 6; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase.

Figure 3.

Progression of chest imaging for patients on high flow nasal therapy (HFNT). (A) Worsening bilateral infiltrates in intubation group. (B) Non-intubation group, improved infiltrates.

Table 4.

Comparing outcomes between intubation and non-intubation groups

| Outcomes | Intubation | Non-intubation | P value |

| Mortality | 13 (35.1%) | 2 (2.9%) | 0.0018 |

| Hospital LOS (days) |

13.67 (±7.97) | 9.7 (±4.6) | 0.03 |

| ICU LOS (days) |

10.45 (±6.12) | 4.05 (±2.64) | 0.0008 |

| HAP/VAP incidence | 3 (8.57%) | 0 | 0.017 |

| Change in SF ratio | 40.5 (±67.90) | 141.4 (±117.14) | 0.0001 |

| Change in CXR RALES | −0.13 (±11.18) | −3.2 (±8.50) | 0.09 |

| Change in HR (beats/min) | −7.65 (±20.69) | −7.95 (±19.19) | 0.94 |

| Change in RR (breaths/min) | −2.32 (±9.32) | −4.4 (±8.39) | 0.27 |

HAP/VAP incidence was defined as number of patients with positive sputum cultures (expectorated or aspirate) that required treatment. Change in SF ratio=SF ratio at day 7–10–SF ratio at day 0.

CXR, chest X-ray; HAP, hospital-acquired pneumonia; HR, heart rate; ICU, intensive care unit; LOS, length of stay; RALES, Radiographic Assessment of Lung Edema Score; RR, respiratory rate; SF ratio, saturation to fraction ratio; VAP, ventilator-associated pneumonia.

Mortality and incidence of ventilator-associated pneumonia/hospital-acquired pneumonia was statistically higher in the intubation groups. Figure 4 shows better survival for the non-intubation group compared with the intubation group.

Figure 4.

Kaplan-Meier estimate of survival of high flow nasal therapy (HFNT) patients, comparing intubation with non-intubation (continued HFNT) groups.

Prediction model

In the univariate analysis, history of hypertension, CKD or having a composite comorbidity score of 1 or greater was predictive of progression to intubation. In terms of laboratory markers, elevated triglycerides (>300 mg/dL) and lower fibrinogen (≤450) were predictive in univariate analysis. SF ratio <100 (OR=2.3) was also a significant predictor in univariate analysis. In the multivariate analysis, only SF ratio (<100), history of CKD and fibrinogen (<450 mg/dL) were predictive of intubation (table 5). Figure 5 shows the ROC curve for our prediction model (ROC=0.7229).

Table 5.

Demographic, clinical and laboratory predictors of intubation using multivariable logistic regression

| Univariate analysis (OR) |

P value | Multivariate analysis (OR) | P value | |

| Age (years) | ||||

| ≤65 | 1 | 0.31 | ||

| >65 | 1.5 | |||

| BMI | ||||

| ≤30 | 0.57 | |||

| >30 | 0.79 | |||

| Smoking | ||||

| No | 1 | 0.32 | ||

| Yes | 1.52 | |||

| Race | ||||

| Non-black | 1 | 0.72 | ||

| Black | 0.87 | |||

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Heart disease | 1.48 | 0.41 | 2.59 | 0.047 |

| Lung disease | 1.79 | 0.19 | ||

| Diabetes | 0.91 | 0.83 | ||

| HTN | 2.1 | 0.07 | ||

| CKD | 2.91 | 0.01 | ||

| Haemodialysis | 1.49 | 0.57 | ||

| No comorbidity | 1 | 2.7 | 0.11 | |

| Any comorbidity | 3.51 | 0.03 | ||

| Laboratory markers | ||||

| Ferritin <400 | 1 | 0.79 | ||

| (ng/mL) ≥400 | 0.89 | |||

| D-dimer <1000 | 1 | 0.37 | ||

| (ng/mL) ≥1000 | 1.47 | |||

| AST <105 | 1 | 0.53 | ||

| (U/L) ≥105 | 1.6 | |||

| AST <180 | 1 | 0.26 | ||

| (U/L) ≥180 | 0.29 | |||

| Triglycerides <300 | 1 | 0.07 | ||

| (mg/dL) ≥300 | 4.81 | |||

| Fibrinogen >450 | 1 | 0.007 | 3.02 | 0.027 |

| (mg/dL) ≤450 | 3.53 | |||

| Abs Lymph Ct ≥1 | 1 | 0.26 | ||

| (K/mm3) <1 | 0.62 | |||

| LDH ≤350 | 1 | 0.18 | ||

| (U/L) >350 | 1.85 | |||

| CRP <6 | 1 | 0.22 | ||

| (mg/dL) ≥6 | 0.58 | |||

| Cumulative laboratory score (1 point per abnormality) | ||||

| <3 | 1 | 0.36 | ||

| ≥3 | 1.5 | |||

| SF ratio | ||||

| ≥100 | 1 | 0.05 | 2.61 | 0.04 |

| <100 | 2.3 | |||

Abs Lymph Ct, absolute lymphocyte count; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate transaminase; BMI, body mass index; CKD, chronic kidney disease; CRP, C reactive protein; HTN, hypertension; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; SF ratio, saturation to fraction ratio.

Figure 5.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve of the predictive model for intubation.

Discussion

In this retrospective review of patients with COVID-19 and acute hypoxaemic respiratory failure, we found that 104 patients (23.3%) were treated initially with HFNT, of which 64.4% remained on HFNT and were able to avoid escalation to non-invasive and IMV. The 67 non-intubation patients (continued HFNT therapy) had a significant improvement in oxygenation and reduction in incidence of hospital-acquired pneumonia compared with those who progressed to intubation. While the survival advantage cannot be attributed to HFNT based on our study’s retrospective design, use of HFNT did not result in worsened outcomes either. The majority of the patient mortality was attributed to the high burden of comorbidities (metastatic cancer, underlying renal and cardiac conditions, obesity, smoking and bacteraemia), rather than progression of respiratory failure on HFNT (table 5).

In similar patients in Italy and China, the intubation rate has been reported between 70% and 90%.3 20 In addition, our group also had a very high burden of comorbid disease, including underlying lung disease and tobacco use. Among our cohort of patients, 30.69% of patients had underlying lung disease and 43.43% were current smokers. In comparison, early case series reports from China only describe 1.1%–3.1% of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD),1 4 22 whereas case series from the Lombardy region of Italy reports 4% of patients with COPD.3 Bhatraju et al reported only one patient with COPD in their recent case series of 21 patients from the Seattle region.23 The rate of smokers in these studies was also low compared with our group’s prevalence of 43.43%. There was no statistically significant difference in our group between those with and without underlying lung disease with regard to progression to IMV. In addition, hypertension and CKD were also shown to be predictive of intubation in our univariate analysis, with CKD also a predictor in multivariate analysis. Chronic uraemia in presence of hypertension leads to chronic left ventricular hypertrophy and other structural changes to the myocardium leaving the patients vulnerable to very small amounts of fluid shifts, subsequently leading to pulmonary oedema.24 CKD has also previously been shown to have worse outcomes including mortality in patients diagnosed with pneumonia.25 A fibrinogen level of <450 mg/dL was found to be predictive of intubation in both univariate and multivariate analysis. Fibrinogen is an acute phase reactant and it is possible that patients who present with a fibrinogen <450 mg/dL may be presenting in a later stage of disease and less amenable to antiviral or anti-inflammatory therapies during support with HFNT.

Prevention of avoidable IMV with HFNT is significant as by nature it avoids incidence of ventilator-associated pneumonia, reduces the need to use medications such as sedatives in which shortages are being reported in the current public health crisis.26 27 The reported mortality in patients requiring IMV in COVID-19 is 90%.3 4 20 Our study shows mortality to be much lower when IMV can be avoided. In addition, HFNT can also decrease utilisation of ventilators, sedatives in the setting of a global pandemic; thus, representing a viable alternative to IMV.

Gattinoni et al have previously reported high respiratory compliance despite a large shunt fraction,28 proposing that patients with COVID-19 fall into two groups. The ‘type L’ or ‘non-ARDS type 1’ phenotype have low elastance/high compliance and possible loss of hypoxic vasoconstriction mechanisms and often present with profound hypoxaemia due to ventilation/perfusion mismatch. The ‘type H’ or ‘ARDS type 2’ phenotype has increased pulmonary oedema and progression to consolidation and requires traditional management strategies of higher positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) and lower tidal volumes.29 We have experienced similar patient subgroups in our practice. As HFNT only provides a modest PEEP effect (ie, 3–5 cmH2O at flow rates of 30–50 L/min with mouth closed),30 patients with predominant type L physiology who do not require the higher positive pressure benefit from the oxygenation support that HFNC can provide non-invasively. HFNT can lead to a high oxygen reservoir by reducing anatomical dead space in the nasopharynx.31 Furthermore, IMV using high tidal volume (which is often employed in type L patients) has shown to have inflammatory cytokine release in patients with ARDS, including IL-6, both in critically ill humans32 33 and murine models34 35; IL-6 in particular is one of the pathological mechanisms for lung injury in COVID-19.36 37 Lastly, patient self-induced lung injury (P-SILI) has been cited as a theoretical contraindication to non-invasive methods of oxygenation. To date, however, P-SILI remains a conceptual model concept compared with Ventilator induced Lung injury (VILI).38 39 Thus, use of HFNT should be a priority in patients with severe COVID-19 respiratory failure.

We elected to use SF ratio than traditional PF ratios in this study for several reasons. SF ratios have been well correlated to standard PF ratios in adult and paediatric populations.40 41 SF ratios <235 predict moderate-to-severe respiratory failure with 85% specificity.41 Our cohort overall showed moderate-to-severe hypoxaemic respiratory failure (mean SF ratio 123 overall), but nonetheless ~64.4% of our cohort could still be supported with high flow oxygen alone. In contrast, Wang et al showed only 37% of patients with COVID-19 did not progress on HFNT when the PF ratio was <200.42 Additionally, lab draws, and arterial blood gases were limited during a pandemic to minimise staff exposure when possible. Hence, ABGs were not routinely collected as part of standard clinical practice at our institution.

There has been debate worldwide about the use of HFNT or other methods of NIV out of concerns for increased disease transmission. During the 2003 SARS outbreak, hospital workers had development of SARS in only 8% of HFNT patients.43 Studies have not shown that bacterial environmental contamination was increased in the setting of HFNT use.13 14 44 An in vitro study mimicking clinical scenarios including HFNT with mannequins only revealed proximal dispersion of secretions to the face and nasal cannula itself.45 46 A recent study with healthy volunteers wearing high flow nasal cannulas at both 30 and 60 L/min of gas flow did not report variable aerosolisation of particles between 10 and 10 000 nm, regardless of coughing, when compared with patients on room air or oxygen via regular nasal cannula.47 In our department of 80 members which included advanced nurse practitioners, attending faculty and fellows, we had only two members who developed COVID-19 infection during the pandemic.

This study has several limitations. First, it was retrospective in nature as developing a prospective trial on the initial management of acute hypoxaemic respiratory failure in the face of an evolving public health crisis is difficult. Second, we could not reasonably analyse a control arm as our end point was prevention of mechanical ventilation. Developing a prospective study during a pandemic situation is impractical without first determining clinical equipoise. Third, we do not report on arterial pH or partial pressure of carbon dioxide (PaCO2) as many patients did not have baseline or follow-up arterial blood gas measurements prior to initiation of HFNT. We recognise that in many clinical trials an elevated PaCO2 was an exclusion criterion for enrolment.7 10 Fourth, our data on hospital LOS was limited since several patients were still hospitalised at the time data were collected.

Institutions around the world have been sceptical about the use of HFNT in patients with COVID-19. However, based on our findings, we conclude that there is a role for HFNT in patients with COVID-19-related severe respiratory failure especially the L-phenotype. Use of HFNT can reduce intubation rates and has the potential to reduce mortality and morbidity associated with it.

Footnotes

Collaborators: Temple University COVID-19 Research Group: Aaron Mishkin, Infectious Disease; Abbas Abbas, Thoracic Medicine and Surgery (TMS); Abhijit S Pathak, Surgery; Abhinav Rastogi, Admin; Adam Diamond, Pharmacy; Aditi Satti, TMS; Adria Simon, Emergency Medicine; Ahmed Soliman, TMS; Alan Braveman, TMS; Albert J Mamary, TMS; Aloknath Pandya, TMS; Amy Goldberg, Surgery; Amy Kambo, TMS;Andrew Gangemi, TMS; Anjali Vaidya, Cardiology; Ann Davison, TMS; Anuj Basil, Cardiology; Bakhos, Charles T, TMS; Bill Cornwell, TMS; Brianna Sanguily, TMS; Brittany Corso, Internal Medicine; Carla Grabianowski, TMS; Carly Sedlock, Infectious Disease; Catherine Myers, TMS; Catherine Myers, TMS; Charles Bakhos, TMS; Chenna Kesava Reddy Mandapati, TMS; Cherie Erkmen, TMS; Chethan Gangireddy, Cardiology; Chih-ru Lin, TMS; Christopher T Burks, Lab Administration; Claire Raab, Internal Medicine; Crabbe, Deborah, Cardiology; Crystal Chen, Internal Medicine; Daniel Edmundowicz, Cardiology; Daniel Sacher, TMS; Daniel Salerno, TMS; Daniele Simon, Emergency Medicine; David Ambrose, TMS; David Ciccolella, TMS; Debra Gillman, TMS; Dolores Fehrle, TMS; Dominic Morano, TMS; Donnalynn Bassler, TMS; Edmund Cronin, Cardiology; Eduardo Dominguez, TMS; Ekam Randhawa, TMS; Ekamjeet Randhawa, TMS; Eman Hamad, Cardiology; Eneida Male, TMS; Erin Narewski, TMS; Francis Cordova, TMS; Frederic Jaffe, TMS; Frederich Kueppers, TMS; Fusun Dikengil, TMS; Galli, Jonathan, TMS; Gangemi, Andrew, TMS; Garfield, Jamie, TMS; Gayle Jones, TMS; Gennaro Calendo, TMS; Gerard Criner, TMS; Gilbert D'Alonzo, TMS; Ginny Marmolejos, TMS; Gordon, Matthew, TMS; Gregory Millio, Internal Medicine; Gupta, Rohit, TMS; Gustavo Fernandez, TMS; Hannah Simborio, TMS; Harwood Scott, TMS; Heidi Shore-Brown, TMS; Hernan Alvarado, Respiratory Care; Ho-Man Yeung, Internal Medicine; Ibraheem Yousef, TMS; Ifeoma Oriaku, TMS; Iris Jung-won Lee, Nephrology; Isaac Whitman, Cardiology; James Brown, TMS; Jamie L. Garfield, TMS; Janpreet Mokha, TMS; Jason Gallagher, School of Pharmacy; Jeffrey Stewart, TMS; Jenna Murray, TMS; Jessica Tang, TMS; Jeyssa Gonzalez, TMS; Jichuan Wu, TMS; Jiji Thomas, TMS; Jim Murrett, Ultrasound Fellow; Joanna Beros, TMS; John M. Travaline, TMS; Jolly Varghese, TMS; Jordan Senchak, Internal Medicine; Joseph Lambert, TMS; Joseph Ramzy, TMS; Joshua Cooper, Cardiology; Jun Song, Medical Student; Junad Chowdhury, TMS; Kaitlin Kennedy, TMS; Karim B Ahmed, TMS; Karim Loukmane, TMS; Karthik Shenoy, TMS; Kathleen Brennan, TMS; Keith Johnson, TMS; Kevin Carney, TMS; Kraftin Schreyer, Emergency Medicine; Kristin Criner, Endo; Kumaran, Maruti, Radiology; Lauren Miller, TMS; Laurie Jameson, TMS; Laurie Johnson, TMS; Laurie Kilpatrick, TMS; Lii-Yoong Criner, TMS; Lily Zhang, TMS; Lindsay K Mcgann, Hospitalist; Llera A Samuels, TMS; Marc Diamond, TMS; Margaret Kerper, TMS; Maria Vega Sanchez, TMS; Mariola Marcinkienwicz, TMS; Maritza Pedlar, TMS; Mark Aksoy, TMS; Mark Weir, TMS; Marla R. Wolfson, TMS; Marla Wolfson, TMS; Marron, Robert, TMS; Martin Keane, Cardiology; Massa Zantah, TMS; Mathew Zheng, TMS; Matthew Delfiner, Internal Medicine; Matthew Gordon, TMS; Maulin Patel, TMS; Megan Healy, Emergency Medicine; Melinda Darnell, TMS; Melinda Darnell, TMS; Melissa Navaro, TMS; Meredith A. Brisco-Bacik, Cardiology; Michael Bromberg, Hematology; Michael Gannon, Cardiology; Michael Jacobs, TMS; Mira Mandal, TMS; Nanzhou Gou, TMS; Narewski, Erin, TMS; Nathaniel Marchetti, TMS; Nathaniel Xander, TMS; Navjot Kaur, TMS; Neil Nadpara, Internal Medicine; Nicole Desai, Internal Medicine; Nicole Mills, TMS; Norihisa Shigemura, Surgery; Ohoud Rehbini, TMS; Oisin O'Corragain, TMS; Oisin O'Corragain, TMS; Omar Sheriff, TMS; Oneida Arosarena, Otolaryngology; Osheen Abramian, TMS; Paige Stanley, TMS; Parag Desai, TMS; Parth Rali, TMS; Patrick Mulhall, Pulm; Pravin Patil, Cardiology; Priju Varghese, Internal Medicine; Puja Dubal, TMS; Puja Patel, TMS; Rachael Blair, TMS; Rajagopalan Rengan, TMS; Rami Alashram, TMS; Randol Hooper, TMS; Rebecca A Armbruster, Chief Medical Officer; Regina Sheriden, TMS; Robert Marron, TMS; Roberto Caricchio, Rheumatology; Rogers Thomas, TMS; Rohit Gupta, TMS; Rohit Soans, Surgery; Roman Petrov, TMS; Roman Prosniak, TMS; Romulo Fajardo, Surgery; Ruchi Bhutani, TMS; Ryan Townsend, TMS; Sabrina Islam, Cardiology; Samantha Pettigrew, Internal Medicine; Samantha Wallace, TMS; Sameep Sehgal, TMS; Samuel Krachman, TMS; Santosh Dhungana, TMS; Sarah Hoang, TMS; Sean Duffy, TMS; Seema Rani, TMS; Shapiro William, TMS; Sheila Weaver, TMS; Shelu Benny, TMS; Sheril George, TMS; Shuang Sun, TMS; Shubhra Srivastava-Malhotra, TMS; Stephanie Brictson, TMS; Stephanie Spivack, Infectious Disease; Stephanie Tittaferrante, Internal Medicine; Stephanie Yerkes, TMS; Stephen Priest, Internal Medicine; Steve Codella, TMS; Steven G Kelsen, TMS; Steven Houser, Research; Steven Verga, TMS; Sudhir Bolla, TMS; Sudhir Kotnala, TMS; Sunil Karhadkar, Surgery; Sylvia Johnson, TMS; Tahseen Shariff, TMS; Tammy Jacobs, TMS; Thomas Hooper, TMS; Tom Rogers, TMS; Tony S. Reed, Chief Medical Officer; Tse-Shuen Ku, TMS; Uma Sajjan, TMS; Victor Kim, TMS; Whitney Cabey, Emergency Medicine; Wissam Chatila, TMS; Wuyan Li, TMS; Zach Dorey-Stein, TMS; Zachariah Dorey-Stein, TMS; Zachary D Repanshek, Emergency Medicine.

Contributors: MP and GC formulated the overall study design. HZ, NP, DF, MP, AG, RM, JC, NM, LT and JT assisted in data collection, consolidation and analysis. MP, AG, RM, JC, IY, MZ, RG, MG, PR and GD'A drafted the manuscript. GC revised and reviewed the manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the Temple University Institutional Review Board (TUIRB protocol number: 27051). A waiver of consent was granted due to the acknowledged minimal risk to the patients.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: All data will be available upon request

References

- 1.Guan W-jie, Ni Z-yi, Hu Y, et al. . Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med Overseas Ed 2020;382:1708–20. 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center COVID-19 MAP; 2020.

- 3.Grasselli G, Zangrillo A, Zanella A, et al. . Baseline characteristics and outcomes of 1591 patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 admitted to ICUs of the Lombardy region, Italy. JAMA 2020. 10.1001/jama.2020.5394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, et al. . Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet 2020;395:1054–62. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Richardson S, Hirsch JS, Narasimhan M, et al. . Presenting characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes among 5700 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the new York City area. JAMA 2020. 10.1001/jama.2020.6775. [Epub ahead of print: 22 Apr 2020]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rello J, Pérez M, Roca O, et al. . High-Flow nasal therapy in adults with severe acute respiratory infection: a cohort study in patients with 2009 influenza A/H1N1v. J Crit Care 2012;27:434–9. 10.1016/j.jcrc.2012.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frat J-P, Thille AW, Mercat A, et al. . High-Flow oxygen through nasal cannula in acute hypoxemic respiratory failure. N Engl J Med 2015;372:2185–96. 10.1056/NEJMoa1503326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ou X, Hua Y, Liu J, et al. . Effect of high-flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy in adults with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. CMAJ 2017;189:E260–7. 10.1503/cmaj.160570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rochwerg B, Granton D, Wang DX, et al. . High flow nasal cannula compared with conventional oxygen therapy for acute hypoxemic respiratory failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med 2019;45:563–72. 10.1007/s00134-019-05590-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hernández G, Vaquero C, Colinas L, et al. . Effect of Postextubation high-flow nasal cannula vs noninvasive ventilation on Reintubation and Postextubation respiratory failure in high-risk patients: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2016;316:1565–74. 10.1001/jama.2016.14194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Azoulay E, Lemiale V, Mokart D, et al. . Effect of high-flow nasal oxygen vs standard oxygen on 28-day mortality in immunocompromised patients with acute respiratory failure: the high randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2018;320:2099–107. 10.1001/jama.2018.14282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Azoulay E, Pickkers P, Soares M, et al. . Acute hypoxemic respiratory failure in immunocompromised patients: the Efraim multinational prospective cohort study. Intensive Care Med 2017;43:1808–19. 10.1007/s00134-017-4947-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alhazzani W, Møller MH, Arabi YM, et al. . Surviving sepsis campaign: guidelines on the management of critically ill adults with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Crit Care Med 2020;48:e440–69. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ñamendys-Silva SA. Respiratory support for patients with COVID-19 infection. Lancet Respir Med 2020;8:e18. 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30110-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu C. Correspondence. Br J Surg 2019;106:949. 10.1002/bjs.11197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kluge S, Janssens U, Welte T, et al. . German recommendations for critically ill patients with COVID‑19. Med Klin Intensivmed Notfmed 2020;2 10.1007/s00063-020-00689-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grein J, Ohmagari N, Shin D, et al. . Compassionate use of Remdesivir for patients with severe Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arentz M, Yim E, Klaff L, et al. . Characteristics and outcomes of 21 critically ill patients with COVID-19 in Washington state. JAMA 2020. 10.1001/jama.2020.4326. [Epub ahead of print: 19 Mar 2020]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu C, Chen X, Cai Y, et al. . Risk factors associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome and death in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA Intern Med 2020. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0994. [Epub ahead of print: 13 Mar 2020]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang X, Yu Y, Xu J, et al. . Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a single-centered, retrospective, observational study. Lancet Respir Med 2020;8:475–81. 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30079-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xie J, Tong Z, Guan X, et al. . Clinical characteristics of patients who died of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3:e205619. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.5619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xu X, Yu C, Qu J, et al. . Imaging and clinical features of patients with 2019 novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2020;47:1275–80. 10.1007/s00259-020-04735-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bhatraju PK, Ghassemieh BJ, Nichols M, et al. . Covid-19 in Critically Ill Patients in the Seattle Region - Case Series. N Engl J Med 2020;382:2012–22. 10.1056/NEJMoa2004500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kooman JP, Leunissen KM. Cardiovascular aspects in renal disease. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 1993;2:791–7. 10.1097/00041552-199309000-00013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Viasus D, Garcia-Vidal C, Cruzado JM, et al. . Epidemiology, clinical features and outcomes of pneumonia in patients with chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2011;26:2899–906. 10.1093/ndt/gfq798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.A new Covid-19 problem: shortages of medicines needed for placing patients on ventilators kneecap our medical system 2020.

- 27.Choo EK, Rajkumar SV. Medication shortages during the COVID-19 crisis: what we must do. Mayo Clin Proc 2020;95:1112–5. 10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.04.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gattinoni L, Coppola S, Cressoni M, et al. . COVID-19 Does Not Lead to a "Typical" Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2020;201:1299–300. 10.1164/rccm.202003-0817LE [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gattinoni L, Chiumello D, Caironi P, et al. . COVID-19 pneumonia: different respiratory treatments for different phenotypes? Intensive Care Med 2020;46:1099–102. 10.1007/s00134-020-06033-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Parke RL, McGuinness SP. Pressures delivered by nasal high flow oxygen during all phases of the respiratory cycle. Respir Care 2013;58:1621–4. 10.4187/respcare.02358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spence CJT, Buchmann NA, Jermy MC. Unsteady flow in the nasal cavity with high flow therapy measured by stereoscopic Piv. Exp Fluids 2012;52:569–79. 10.1007/s00348-011-1044-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Network, Brower RG, Matthay MA, et al. . Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with traditional tidal volumes for acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 2000;342:1301–8. 10.1056/NEJM200005043421801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wrigge H, Zinserling J, Stüber F, et al. . Effects of mechanical ventilation on release of cytokines into systemic circulation in patients with normal pulmonary function. Anesthesiology 2000;93:1413–7. 10.1097/00000542-200012000-00012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chiumello D, Valente Barbas CS, Pelosi P. Pathophysiology of ARDS : Lucangelo U, Pelosi P, Zin WA, et al., Respiratory system and artificial ventilation. Milano: Springer Milan, 2008: p. 101–117. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tremblay LN, Slutsky AS. Ventilator-induced lung injury: from the bench to the bedside : Pinsky MR, Brochard L, Mancebo J, Applied physiology in intensive care medicine. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2006: p. 357–366. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. . Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. The Lancet 2020;395:497–506. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fu B, Xu X, Wei H. Why tocilizumab could be an effective treatment for severe COVID-19? J Transl Med 2020;18:164. 10.1186/s12967-020-02339-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marini JJ, Gattinoni L. Management of COVID-19 respiratory distress. JAMA 2020;323:2329–30. 10.1001/jama.2020.6825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tobin MJ, Laghi F, Jubran A. Caution about early intubation and mechanical ventilation in COVID-19. Ann Intensive Care 2020;10:78. 10.1186/s13613-020-00692-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nava S, Schreiber A, Domenighetti G. Noninvasive ventilation for patients with acute lung injury or acute respiratory distress syndrome. Respir Care 2011;56:1583–8. 10.4187/respcare.01209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rice TW, Wheeler AP, Bernard GR, et al. . Comparison of the SpO2/FIO2 ratio and the PaO2/FIO2 ratio in patients with acute lung injury or ARDS. Chest 2007;132:410–7. 10.1378/chest.07-0617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang K, Zhao W, Li J, et al. . The experience of high-flow nasal cannula in hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in two hospitals of Chongqing, China. Ann Intensive Care 2020;10:37. 10.1186/s13613-020-00653-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Raboud J, Shigayeva A, McGeer A, et al. . Risk factors for SARS transmission from patients requiring intubation: a multicentre investigation in Toronto, Canada. PLoS One 2010;5:e10717. 10.1371/journal.pone.0010717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Leung CCH, Joynt GM, Gomersall CD, et al. . Comparison of high-flow nasal cannula versus oxygen face mask for environmental bacterial contamination in critically ill pneumonia patients: a randomized controlled crossover trial. J Hosp Infect 2019;101:84–7. 10.1016/j.jhin.2018.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kotoda M, Hishiyama S, Mitsui K, et al. . Assessment of the potential for pathogen dispersal during high-flow nasal therapy. J Hosp Infect 2020;104:534–7. 10.1016/j.jhin.2019.11.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li J, Fink JB, Ehrmann S. High-Flow nasal cannula for COVID-19 patients: low risk of bio-aerosol dispersion. Eur Respir J 2020;55. 10.1183/13993003.00892-2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Iwashyna TJ, Boehman A, Capelcelatro J, et al. . Variation in aerosol production across oxygen delivery devices in spontaneously breathing human subjects. medRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar]