Abstract

Malaria is a parasitic infectious disease and was responsible for 400.000 deaths in 2018. Plasmodium falciparum represents the species that causes most human deaths due to severe malaria. In addition, studies prove the resistance of P. falciparum to drugs used to treat malaria, making the search for new drugs with antiplasmodial potential necessary. In this context, the literature describes snake venoms as a rich source of molecules with microbicidal potential, including phospholipases A2 (PLA2s). In this sense, the present study aimed to isolate basic PLA2s from Paraguayan Bothrops diporus venom and evaluate their antiplasmodial potential. Basic PLA2s were obtained using two chromatographic steps. Initially, B. diporus venom was subjected to ion exchange chromatography (IEC). The electrophoretic profile of the fractions from the IEC permitted the selection of 3 basic fractions, which were subjected to reverse phase chromatography, resulting in the isolation of the PLA2s. The toxins were tested for enzymatic activity using a chromogenic substrate and finally, the antiplasmodial, cytotoxic potential and hemolytic activity of the isolated toxins were evaluated. The electrophoretic profile of the fractions from the IEC permitted the selection of 3 basic fractions, which were subjected to reverse phase chromatography, resulting in the isolation of the two enzymatically active PLA2s, BdTX-I and BdTX-II and the PLA2 homologue BdTX-III. The antiplasmodial potential was evaluated and the toxins showed IC50 values of: 2.44, 0.0153 and 0.59 μg/mL respectively, presenting PLA2 selectivity according to the selectivity index results (SI) calculated against HepG2 cells. The results show that the 3 basic phospholipases isolated in this study have a potent antiparasitic effect against the W2 strain of P. falciparum. In view of the results obtained in this work, further research are necessary to determine the mechanism of action by which these toxins cause cell death in parasites.

Keywords: Snake venom, Bothrops diporus, Phospholipases A2, Antiparasitic activity, Plasmodium falciparum

Highlights

-

•

Three basic PLA2s from the venom of Paraguayan Bothrops diporus have been isolated.

-

•

In vitro Antimalarial activity of PLA2s against intra-erythrocytic forms of Plasmodium falciparum were evaluated.

-

•

Cytotoxicity on HepG2 cells, hemolytic activity and Selectivity Index of PLA2s were analyzed.

1. Introduction

Malaria is an infectious parasitic disease with vector transmission involving a diversity of parasites in different ecological environments. Endemicity occurs in tropical and subtropical regions, mainly in Sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America and Southeast Asia. In 2018, the World Health Organization (WHO) reported 228 million cases of malaria, with an estimated 405,000 deaths; children under the age of 5 represent the most vulnerable group for this endemic disease. Despite decades of efforts, this disease remains a leading cause of death worldwide (WHO, 2020).

The species capable of infection in humans are: Plasmodium falciparum, P. vivax, P. malariae, P. ovale and P. knowlesi (Cox, 2010). Among these, P. falciparum has a higher proportion of cases in the following regions: Africa (99.7%), Southeast Asia (50%), Eastern Mediterranean (71%) and Western Pacific Region (65%), while P. vivax appears in 53% of cases in Southeast Asia and the Americas. These are species with the highest epidemiological prevalence (WHO, 2020).

Regarding clinical presentation, the species P. falciparum is responsible for the severest form of malaria and, consequently, causes the majority of deaths. Another factor that makes P. falciparum an important focus of study is the capacity of resistance development by the parasite to antimalarials, especially for the standard scheme treatment. Initially, cases of Chloroquine resistance were recorded in Southwest Asia and then in South America (Nevin and Croft, 2016; Wongsrichanalai et al., 2002). Due this fact, since 2001, combined therapy with artemisinin (ATC) has been used in the treatment of malaria (Su and Miller, 2015); however, failed treatments with ATC have been reported in strains of P. falciparum on the Thailand-Cambodia and Myanmar border, reaffirming the need for studies of new molecules with antiplasmodial potential (Ashley et al., 2014; Bhumiratana et al., 2013; Mathenge et al., 2020).

Given this scenario, the application of drugs with different chemical properties, the improvement of available pharmaceuticals and the development of new drugs, present new alternatives that may delay the evolution of parasitic resistance against antimalarials (Okombo and Chibale, 2016).

Regarding the identification of agents with biotechnological potential, biodiversity is very important as a source for the discovery of new molecules (Harvey et al., 2015; Newman and Cragg, 2016). In this sense, molecules of animal origin have stood out in the scientific literature for presenting microbicidal properties and within this group, snake venoms have been the target of numerous studies (Harvey et al., 1998; Koh et al., 2006). Snake venoms are characterized by the complex constitution of molecules, mainly of a protein nature, which are related to a wide spectrum of pharmacological effects (Lomonte et al., 2014; Simoes-Silva et al., 2018).

One group of molecules present in these secretions are Phospholipases A2 (PLA2, EC 3.1.1.4), enzymes dependent on the calcium ion that catalyze hydrolysis in the sn-2 position of phospholipids, triggering the release of fatty acids and lysophospholipids (Dennis et al., 2011; Gutiérrez and Lomonte, 2013). Snake venom PLA2s (svPLA2) are widely studied proteins and are related to several clinical manifestations of snakebite envenoming, such as myotoxicity, neurotoxicity, cardiotoxicity, inhibition of platelet aggregation, and edema, among others (Gutiérrez and Lomonte, 2013; Kini, 2003; Lomonte and Gutiérrez, 2011).

An interesting characteristic of bothropic venoms is the presence of PLA2 isoforms. In addition to enzymatically active PLA2s, which have an aspartic acid residue at position 49 (Asp49-PLA2), the presence of PLA2s with no catalytic properties has been reported, called PLA2-homologues or Lys49-PLA2, due to the presence of a lysine residue at position 49 (Gutiérrez and Lomonte, 2013; Kini, 2003). Within the group of homologous PLA2s, variants have been described such as Ser49-PLA2 (Krizaj et al., 1970), Arg49- PLA2 (Mebs et al., 2006) and Gln49-PLA2 (Bao et al., 2005). It should be noted that, PLA2-homologues are devoid of enzymatic activity, and are responsible for various pharmacological effects (Lomonte et al., 2003).

In recent decades, another aspect of svPLA2 under investigation are their potential biotechnological applications and in this context, several authors have reported the antitumor potential (Araya and Lomonte, 2007), antiviral (Cecilio et al., 2013)and antiparasitic activity of svPLA2s (Grabner et al., 2017), which makes this group of proteins promising targets of study. In view of the above, the present study describes the isolation of basic PLA2s from the venom of Paraguayan Bothrops diporus with the objective of evaluating their antiparasitic potential on intra-erythrocytic forms of Plasmodium falciparum.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Venom and authorization

Bothrops diporus snake venom was obtained from specimens kept in captivity at the Catholic University of Asuncion bioterium in Paraguay. This study was authorized by the Secretariat of the Environment, SEAM-Paraguay, Authorization N° 01/14 and pooled venom was kept refrigerated (8 °C) in the Bank of Amazon Venoms at the Center of Biomolecules Studies Applied to Health, CEBio-UNIR-FIOCRUZ-RO (Authorization: CGEN/CNPq 010627/2011-1; IBAMA 27131-2 and CEBio UNIR-FIOCRUZ-RO (register CGEN A4D12CB and IBAMA/SISBIO 64385-1).

2.2. Isolation of phospholipases A2 from B. diporus venom

Fifty milligrams of B. diporus venom was solubilized in 1 mL of buffer A (Ammonium Bicarbonate, 50 mM, pH 8) and centrifuged at 8000×g for 10 min. The supernatant was fractionated in cation exchange chromatography, using a CM-Sepharose GE® (1 × 30 cm) column, previously equilibrated with buffer A. Fractionation was performed by applying a linear gradient of 0–100% of Buffer B (Ammonium Bicarbonate, 500 mM, pH 8), at a flow of 1 mL/min. This procedure was monitored at 280 nm, using an Akta purifier (GE®) chromatographic system. Finally, the manually collected fractions were lyophilized and stored at −20 °C.

Determination of the relative molecular masses of the proteins present in the eluted fractions was performed by 12.5% SDS-PAGE, following the methodology described by Laemmli (1970). Ten μg of the lyophilized fractions was mixed with 4% SDS (m/v), 0.2% Bromophenol Blue (m/v), 20% glycerol (v/v) 0.2 M Dithiothreitol (DTT) in 100 mM Tris pH 6.8 and heated for 5 min at 90 °C. Subsequently, the gel was incubated in a fixative solution (50% ethanol and 12% acetic acid) for 30 min, and then stained with a PhastGel™ Blue R solution (GE Healthcare) for 30 min. Finally, the gel was placed in a solution with 4% ethyl alcohol and 7% acetic acid to remove the excess stain. In order to obtain and document images of the gel, ImageScanner III (GE Lifescience Health Care) was used.

For the following step, fractions 5, 6 and 7 from the ion exchange chromatography were selected for having molecular masses compatible with phospholipases A2. Fractions were solubilized in 0.1% aqueous trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) solution and subjected to RPC in a C18 column (Discovery-Sigma-Aldrich) using 0.1% trifluoracetic acid (TFA) as solution A and 0.1% trifluoracetic acid (TFA) and 99.9% acetonitrile as solution B at a 0–70% gradient with a flow of 1 mL/min. The elution was monitored at 280 nm using an Akta purifier (GE®) chromatographic system. Samples were manually collected, dried in speed vac (Labconco®) and stored at −20 °C. Subsequently, the eluted toxins were subjected to SDS-PAGE, 12.5% and the procedure was carried out following the steps mentioned above.

Protein quantitation was performed with DC Protein Assay kit (BIORAD®), following the manufacture's specifications.

2.3. Phospholipase activity

The phospholipase activity assay was performed according to the protocol described by Holzer and Mackessy (1996), with some modifications. Phospholipase activity of purified toxins by RPC was determined using 4-nitro- 3-(octyloxy) benzoic acid (4N3OBA) as a colorimetric reagent. Initially, 200 μg of reagent was solubilized in 2 mL of a solution with 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 100 mM NaCl and 10 mM CaCl2. The toxins were diluted in Milli-Q water obtaining a concentration of 1 μg/μL. After adding the toxins, 200 μL of the mixture was incubated in 96-well plates for 30 min at 37 °C. Absorbance was determined at 425 nm using an Eon (Biotek) microplate spectrophotometer, at 3-min intervals. A Lys49-PLA2 (BtTX-I) and an Asp49-PLA2 (BthTX-II) from B. jararacussu snake venom were used as the negative and positive controls.

2.4. In vitro antimalarial assays against P. falciparum

Chloroquine-resistant and mefloquine-sensitive (W2) P. falciparum clones of the Indochina III/CDC strain were used for the antimalarial activity assays. Parasite cultures were grown in human red blood cells under conditions established by Trager and Jensen (1976), with modifications. Cultures were prepared in TPP bottles with 2% hematocrit, diluted in RPMI 1640 medium culture (supplemented with 25 mM HEPES, 21 mM sodium bicarbonate, 11 mM glucose, 40 μg/mL gentamicin, and 0,5% (w/v) Albumax). The cultures were maintained in desiccators at 37 °C in a standard gas mixture consisting of 5% O2, 5% CO2 and 90% N2. Culture media were changed daily and parasitemia was monitored in blood smears, fixed with methanol, stained with fast panoptic segmentation and visualized under an optical microscope with an immersion objective lens (1000×).

2.4.1. Synchronization of parasites for in vitro tests

Cultures with a predominance of ring forms were obtained through synchronization with sorbitol as described by Lambros and Vanderberg (1979). The culture medium was removed from the bottles and 10 mL of 5% sorbitol and 0.5% glucose were added to the red blood cells containing the parasites. The volume was then transferred to a 15 mL Falcon® tube, incubated at 37 °C for 10 min and centrifuged for 5 min, 70×g at room temperature. The supernatant was removed, and the pellet resuspended in complete RPMI 1640 medium. Hematocrit and parasitemia were adjusted to 2% and 0.5%, respectively.

2.4.2. In vitro assay against P. falciparum

Parasite cultures were distributed in 96-well microplates with 180 μL/well of RPMI 1640 medium containing: 0.5% parasitemia and 2% hematocrit for the SYBR Green I test (Sigma-Aldrich®). Prior to adding the parasite suspension, 20 μL of the samples, previously diluted in PBS 1X, were added to the test plate in serial concentrations from 10 to 0.00488 μg/mL. Artemisinin (0.05 μg/mL) was used as a positive control, infected red cells were used as the negative control, and non-infected red blood cells (blank) as the experimental control. The plates were incubated at 37 °C for 48 h.

After the incubation period, a fluorescence test was performed according to Smilkstein et al. (2004). Briefly, the supernatant was removed and 100 μL of phosphate buffered saline (PBS) 1X was added to each well, and then centrifuged at 700×g for 10 min in order to wash the red blood cells. Afterwards, the supernatant was discarded and 100 μL of lysis buffer (20 mM Tris, pH 7.5; 5 mM EDTA; 0.008%; w/v saponin; w/v saponin; 0.08%, Triton X-100 v/v) with SYBR Green I was added and the solution was transferred to 96-well microplates with 100 μL of 1X PBS, after which a reading was performed. After incubation for 30 min at room temperature, fluorescence was measured using a spectrophotometer (Synergy HT-BioTek) with an excitation of 485 nm and an emission of 590 nm.

2.5. In vitro cytotoxicity assays against HepG2 and selectivity index

Cytotoxicity was evaluated against HepG2 cells, in 96-well plates. The samples were tested in serial concentrations from 10 to 0.00488 μg/mL for BdTX-II and 100 to 0.00159 μg/mL for BdTX-I and BdTX-III, with a treatment period of 48 h. Concomitantly, the negative control consisted of untreated cells, while the positive control was cells treated with lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, 5 mM EDTA, 0.08% Triton X-100, 0.008% saponin in 1X PBS, at pH 7.5) and complete RPMI 1640 medium (control).

Cytotoxicity was determined using the MTT colorimetric method (3-[4,5- dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide-Sigma-Aldrich). After the treatment period, 20 μL of MTT was added at a concentration of 5 mg/mL in PBS 1x (w/v) to wells and incubated for 4 h at 37 °C with CO2 (Mosmann, 1983); after the incubation period, the supernatant was discarded and 100 μL of DMSO (Sigma-Aldrich) was added to the wells to dissolve the formazan crystals. Optical reading was performed on a plate spectrophotometer (Biochrom model: Expert plus) at wavelengths of 570 nm. Cell viability was determined according to the equation below:

Viability (%) = (Test absorbance – Blank absorbance) X 100

(Control absorbance – Blank absorbance)

The selectivity index (SI) was calculated using the ratios between the CC50 and IC50 values of the respective samples. Samples with SI values greater than 10 were considered to be selective/non-toxic, while compounds with SI values less than 10 were considered non-selective/toxic (Nava-Zuazo et al., 2010).

2.6. In vitro hemolytic activity

The hemolysis assay was performed with a suspension of 1% human erythrocytes in 180 μL of incomplete RPMI 1640 medium, distributed in a 96-well microplate with “U” bottom (Kasvi). 20 μL of samples, in serial concentrations from 10 to 0.00488 μg/mL, were deposited in the microplates and then incubated for 30 min at 37 °C, with shaking every 5 min (Wang et al., 2010). The absorbances were read on a spectrophotometer (Biochrom model: Expert plus) at wavelengths of 540 nm. 0.05% saponin (Sigma Aldrich®) was used as the positive control for hemolysis and non-lysed red blood cells cultured in incomplete RPMI 1640 medium were used as the negative control.

2.7. Quality control -Z’ - factor

The results of the antimalarial, cytotoxicity and hemolysis tests were subjected to a quality control parameter. The parameter used was the Z′-factor (Zhang et al., 1999), a statistical factor that indicates the reliability of the results based on the degree of difference between positive and negative controls. The Z′-factor values were calculated based on the following formula:

where: dpN = negative control standard deviation, dpP = positive control standard deviation, MN = negative control mean, MP = positive control mean.

2.8. Statistical analyses

The analyses were performed with the aid of GraphPad Prism version 6.0 and Origin version 9.1. The results were expressed as mean ± SD of three independent experiments carried out in triplicate. The analysis of growth inhibition of 50% of the parasites (IC50) and cytotoxic concentration for 50% of the cells (CC50) were calculated using dose-response curves as a function of non-linear regression, applying the formula y = A1+(A2-A1)/(1 + 10^((LOGx0-x)*p)). ANOVA followed by the Tukey multiple comparison test were used to analyze phospholipase activity and hemolysis assays. The differences were considered significant when the p value showed a significance level <0.05.

3. Results

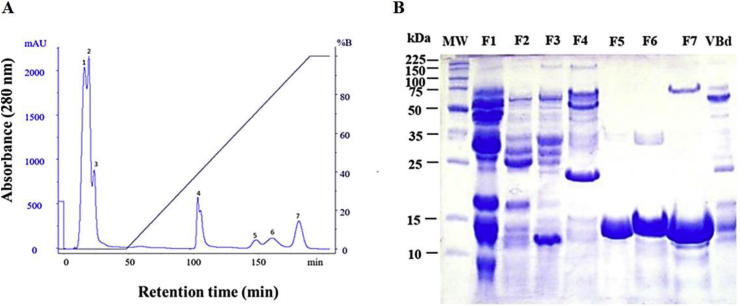

3.1. Isolation of PLA2s

The result for IEC was 7 main fractions (Fig. 1A), numbered 1–7, respectively. The initial fractions 1–3, which eluted before applying the gradient, correspond to acidic proteins, while the last four fractions 4–7 correspond to basic proteins, with fraction 4 being obtained with approximately 30% buffer B and fractions 5, 6 and 7 eluted after approximately 65% buffer B. SDS-PAGE 12.5% was performed in order to determine the apparent molecular masses of putative PLA2s, as well as of the molecules present in the eluted fractions (Fig. 1B). The electrophoretic profile suggests the presence of a variety of proteins with different molecular masses, which is characteristic of bothropic venoms.

Fig. 1.

Chromatographic and electrophoretic profiles of B. diporus venom. (A) This procedure allowed us to obtain seven fractions. The samples were eluted with a 0–100% gradient of buffer B, with a flow rate of 1 mL/min. Elution was monitored at 280 nm. (B) Electrophoretic profile of B. diporus venom (VBd) and seven fractions (F1–F7) eluted in IEC. It can be observed that F5, F6 and F7 fractions present protein bands with molecular mass ≈13 kDa, compatible with that of svPLA2s.

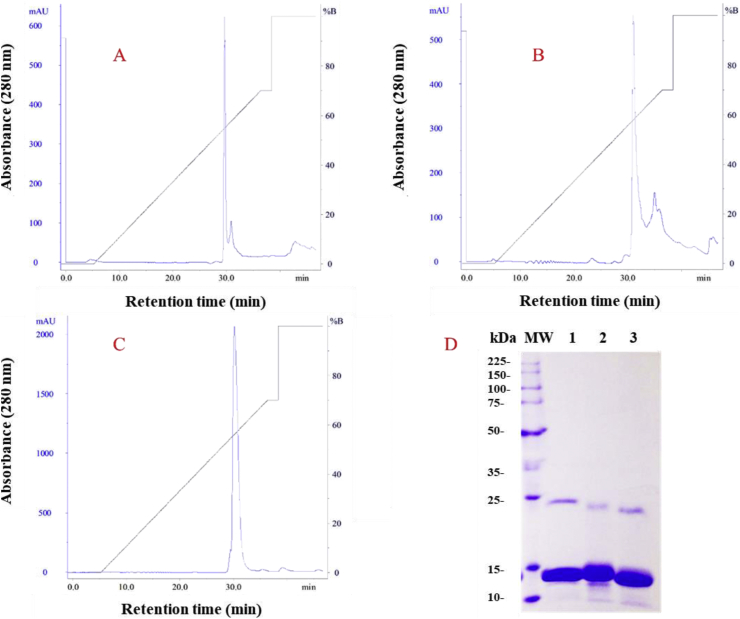

Based on the chromatographic and electrophoretic profiles (Fig. 1), the basic fractions F5, F6 and F7 were submitted to RPC. Fig. 2A–C shows the elution profile for the three isolated molecules. The electrophoretic profile allows for the visualization of main bands at approximately 13 kDa for each isolated toxins, putative PLA2s, which were named BdTX-I, BdTX-II and BdTX-III, respectively. It is possible to observe bands with proteins at approximately 25 kDa, corresponding to aggregates of PLA2s in dimeric forms.

Fig. 2.

Chromatographic profile in RPC of F4-6 IEC fractions from B. diporus venom. Fig. 2A–C shows the RPC elution profile of the three isolated basic PLA2s: BdTX-I (A), BdTX-II (B) and BdTX-III (C), respectively. The electrophoretic profile (D) demonstrates the presence of main bands with proteins ≈13 kDa, compatible with the molecular weight of svPLA2s. Lanes: 1- BdTX-I, 2- BdTX-II and 3- BdTX-III.

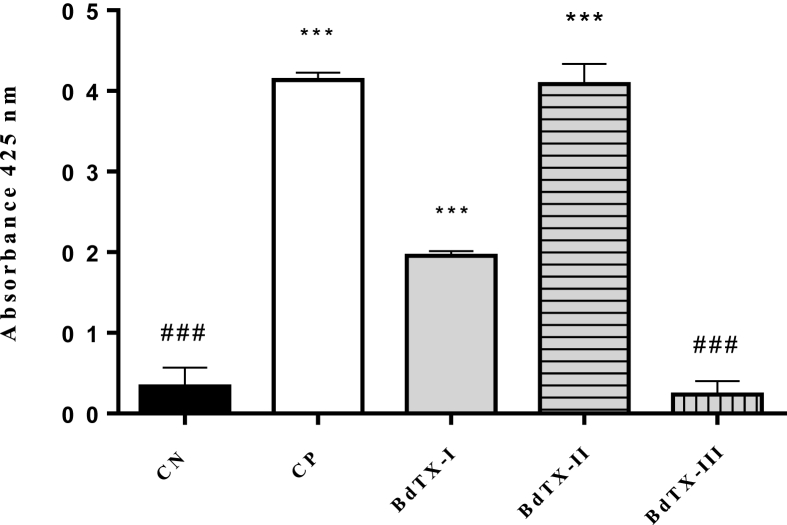

Phospholipase activity was evaluated using the chromogenic substrate 4N3OBA. In this step, it was demonstrated that BdTX-I showed enzymatic activity; however, the activity of BdTX-II was even more intense (Fig. 3). The enzymatic activity of these toxins was compared with the positive control (CP) BthTX-II (Asp49-PLA2). BdTX-III showed no activity on the substrate, comparable to the negative control (CN) (BthTX-I, a Lys49-PLA2-homologue). Both controls correspond to toxins isolated from B. jararacussu venom.

Fig. 3.

Phospholipase activity of toxins isolated from B. diporus venom using the substrate 4N3OBA. CN: Negative control BthTX-I, CP: Positive control BthTx-II. Columns marked with * differ statistically from CN and columns marked with # differ statistically from CP based on ANOVA (***/###p < 0.0001), followed by the Tukey post-test.

The PLA2s isolated from fractions 5, 6 and 7 tested in vitro against strains of P. falciparum, showed IC50 values of 2.44 μg/mL, 0.0153 μg/mL and 0.59 μg/mL, respectively. Cytotoxicity assays on HepG2 cells indicated that the PLA2s were not toxic at the concentrations tested, with CC50 ≥ 10 and 100 μg/mL for both. The exact Selectivity Index (SI) cannot be calculated; however, with these results, the fractions were selective and non-toxic, showing SI ≥ 41, ≥653.6 and ≥169.5, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1.

Bioactivity of PLA2s from B. diporus venom against P. falciparum.

| PLA2 | IC50 (μg/mL) P. falciparum | Standard deviation (±) | CC50 (μg/mL) HepG2 | SI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BdTX-I | 2.44 | 0.15 | ≥100 | ≥41 |

| BdTX-II | 0.0153 | 0.005 | ≥10 | ≥653.6 |

| BdTX-III | 0.59 | 0.03 | ≥100 | ≥169.5 |

| Artemisinin | 0.0125 | 0.3 | ≥1000 | ≥80.000 |

IC50 = half maximal inhibitory concentration.

CC50 = half maximal cytotoxic concentration.

SI= Selectivity Index.

Regarding the hemolytic capacity of these PLA2s, as a result, proteins did not show hemolytic action at the tested concentrations (10–0.0048 μg/mL). This result demonstrates that the PLA2s are selective against the parasite and do not cause damage to erythrocytes.

4. Discussion

The diversity of proteins found in snake venoms explains the motivation of research groups who seek to develop studies aimed at elucidating the physical, chemical, structural and biological characteristics of the molecules that make up these venom and the relationship that these molecules have with the pathophysiology of snake envenoming and biotechnological applications (Kini and Fox, 2013; Simoes-Silva et al., 2018). Thus, the aim of this study was to evaluate the antiparasitic potential of basic isoforms of PLA2s isolated from B. diporus venom.

Several authors have reported the purification of svPLA2s through the application of different chromatographic techniques (Stábeli et al., 2012). In the present study, we chose to use cation exchange chromatography as the first fractionation step, a procedure from which 7 fractions were eluted (Fig. 1A), which were subjected to 12.5% SDS-PAGE. The electrophoretic profile presents the relative molecular masses of the proteins present in the seven eluted fractions (Fig. 1B).

Both the characteristic elution profile of fractions 5, 6 and 7 corresponding to basic proteins, as well as the relative molecular masses of the proteins observed in the aforementioned fractions, suggest that the molecules eluted in the last three fractions correspond to basic PLA2s present in B. diporus venom. Cation exchange chromatography has already been reported by several authors as an efficient step for the fractionation and isolation of the proteins that make up these venoms (Andrião-Escarso et al., 2000; Soares et al., 1998, 2000a, 2000b).

Subsequently, basic fractions compatible with svPLA2 molecular weights were subjected to reverse phase chromatography (Fig. 2A–C). The combination of IEC followed by RPC has already been reported by several authors, who mention that these steps contribute considerably to the isolation of basic PLA2s from bothropic venoms, guaranteeing the purification of the molecules of interest with a high degree of purity (Alfonso et al., 2019; Grabner et al., 2017; Nunes et al., 2013). The electrophoretic profile of the isolated toxins can be seen in Fig. 2D. The eluted molecules were named BdTX-I, BdTX-II and BdTX-III, and for each of them, a main band of approximately 13 kDa can be observed, compatible with svPLA2 molecular masses.

The test performed to evaluate the enzymatic activity of these toxins (Fig. 3) revealed that both BdTX-I and BdTX-II exert enzymatic activity, which indicates that these enzymes belong to the group of Asp49-PLA2s. On the other hand, considering that BdTX-III did not show catalytic properties, it is suggested that this protein is a homologous PLA2, with a lysine residue at position 49 (Maraganore et al., 1984; Ownby et al., 1999).

In this study, protein quantification suggests that the isolated proteins correspond to approximately 15% of the B. diporus venom. The literature describes PLA2s as representing approximately 24% of the B. diporus venom proteome, with approximately 65% of PLA2s corresponding to the Asp49-PLA2 group (Gay et al., 2015). Recently, Teixera and coworkers (2018) reported the isolation of a Lys49-PLA2 homologue from B. diporus named BdpTX-I. The authors describe this toxin as having pharmacological effects such as myotoxicity and edema induction.

Subsequently, from the venom of the same species, Bustillo and coworkers (2019) describe the isolation of PLA2-I (Asp49) and PLA2-II (Lys49), reporting myonecrotic, cytotoxic action and suggesting that proteins have a synergistic effect that can potentiate their pharmacological effects.

As previously described, svPLA2s present in B. diporus venom are responsible for different pharmacological effects. While the literature reports the antiparasitic activity of this group of proteins (Alfonso et al., 2019; Grabner et al., 2017; Nunes et al., 2013; Stábeli et al., 2006), this study aimed to evaluate the cytotoxic capacity of PLA2s against the intra-erythrocytic forms of P. falciparum, becoming the first report in scientific literature to perform antiplasmodial assays of toxins isolated from Paraguayan B. diporus.

Some authors have demonstrated that antiplasmodial action is more pronounced in enzymatically active PLA2s than inactive ones. However, BmajPLA2-II (a Lys49-PLA2-homologue), isolated by Grabner and coworkers (2017) presents an IC50 value comparable to that of the enzymatically active PLA2s obtained in this study.

Previously, Zieler and coworkers investigated the antiplasmodial activity of a phospholipase isolated from Crotalus adamanteus; the authors describe that a concentration of 1 μmol.L−1 of PLA2 is effective to block the in vitro development of ookinetes, intestinal forms of P. falciparum found in the mosquito (Zieler et al., 2001). In this context, Guillaume et al. also report antimalarial effects against intra-erythrocytic forms of P. falciparum of seven PLA2s, with IC50 values between 512.4 and 0.1 nM, including the snakes Agkistrodon halys, Naja mossambica mossambica, Notechis scutatus scutatus and Vipera ammodytes (Guillaume et al., 2004).

Upon analysis of the activities presented by different bothropic venoms, it is noted that the PLA2s of these venoms are relevant in terms of their antiprotozoal action and antiplasmodial potential as shown in the present study.

The cytotoxicity assessment of the PLA2s BdTX-I, BdTX-II and BdTX-III was performed against HepG2 cells. This cell line was chosen because hepatocytes are cells that naturally metabolize drugs and where Plasmodium replicates during a phase of its cycle in the vertebrate host (Thieleke-Matos et al., 2016). The CC50 values observed for the three PLA2s was ≥10 and 100 μg/mL; with this result the exact SI cannot be calculated; however, the fractions can be considered potentially safe regarding cytotoxicity parameters, since the SI results were greater than 10 (Bézivin et al., 2003; Katsuno et al., 2015).

The cytotoxic profile obtained in this study agrees with results previously obtained (Castillo et al., 2012). These authors tested an Asp49-PLA2 purified from the venom of B. asper, which presented a CC50 of 26.98 μg/mL against PBMC and an SI of 19 against P. falciparum. In this context, Grabner et al. reported that BmajPLA2-II has a CC50 of 53.07 μg/mL and an SI of 8.28. It is noted that homologous PLA2s tend to have lower SI than enzymatically active PLA2s; however, in the present study the three protein isoforms presented CC50 and SI values characterizing them as selective and non-toxic (Grabner et al., 2017).

In order to observe that the antiplasmodial activity of PLA2s is not due to hemolytic action, an in vitro hemolysis assay was performed, using the same concentrations tested in the antiplasmodial assay. BdTX-I, BdTX-II and BdTX-III did not present hemolysis. The correlation of these results shows that the antiplasmodial activity of these PLA2s may occur directly on the intra-erythrocytic forms of P. falciparum and not cause destabilization or lysis of the red blood cell membrane.

5. Conclusion

Natural animal and plant products can provide compounds that have therapeutic biotechnological potential in the face of biological tests; among these include snake venoms, which have been successful in obtaining new drugs. Bothropic venoms are biochemically complex, consisting mostly of protein components, such as metalloproteases, serinoproteases, type C lectins, L-amino acid oxidases (LAAO), myotoxins, disintegrins and phospholipases A2 (PLA2).

The results presented herein show that PLA2s isolated from B. diporus have applicable biotechnological potential regarding their antiplasmodial activity. New studies should be carried out in order to understand the mechanism of death of the parasite in the presence of these proteins.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Keila A. Vitorino: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology. Jorge J. Alfonso: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing, Visualization. Ana F. Gómez: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Writing - original draft, Visualization. Ana Paula A. Santos: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing, Visualization. Ygor R. Antunes: Methodology, Validation. Cleópatra A. da S. Caldeira: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology. Celeste V. Gómez: Visualization, Supervision. Carolina B.G. Teles: Conceptualization, Validation, Writing - original draft, Funding acquisition. Andreimar M. Soares: Writing - original draft, Project administration, Funding acquisition. Leonardo A. Calderon: Project administration, Funding acquisition.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the Catholic University of Asuncion, Paraguay for collecting the venom and making it available to the Plataforma de Bioensaios de Malária e Leishmaniose (PBML) of the Oswaldo Cruz-Rondônia Foundation (FIOCRUZ-RO) for carrying out the in vitro tests. The authors express their gratitude to the Conselho de Gestão do Patrimônio Genético (CGEN/MMA) and the Programa de Desenvolvimento Tecnológico em Ferramentas para a Saúde, PDTIS-FIOCRUZ.

Contributor Information

Jorge J. Alfonso, Email: jorwish@gmail.com.

Ana Paula A. Santos, Email: paulaazevedo.2011@gmail.com.

Abbreviations

- PLA2

phospholipase

- A2; svPLA2

snake venom phospholipase A2

- IEC

Ionic Exchange Chromatography

- SDS-PAGE

Poly-Acrylamide Gel Electrophoresis in the presence of Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate

- RPC

Reverse Phase Chromatography

- TFA

trifluoroacetic acid

- ACN

Acetonitrile

- 4N3OBA

4-nitro- 3-(octyloxy) benzoic acid

- RPMI-1640

Roswell Park Memorial Institute

- MTT

3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide

- DMSO

Dimethyl sulfoxide

- IC50

half maximal inhibitory concentration

- CC50

half maximal cytotoxic concentration

- SI

Selectivity Index

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Funding

The authors express their gratitude to the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq/MCTIC), Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES/MEC), Fundação Rondônia de Amparo ao Desenvolvimento das Ações Científicas e Tecnológicas de Pesquisa do Estado de Rondônia (FAPERO), Instituto Nacional de Epidemiologia da Amazônia Ocidental (EpiAmO), and the National Research Incentive Program (PRONII-229/2011) of the National Council for Science and Technology (CONACYT) for financial support.

Authors’ contributions

KAV, JJA, AFG, YRA, AMS, LAC performed the isolation and biochemical characterization. KAV, APAS, CBGT carried out the plasmonicidal assays. KAV, JJA, AFG, YRA, AMS, LAC, CVG, APAS, CBGT analyzed the results. KAV, JJA, AFG, YRA, CASC, CVG, APAS, CBGT, AMS and LAC participated in the discussion of the results, carried out a critical review of the work and assisted in drafting and structuring the manuscript. JJA, AFG, LAC, CBTG, CVG and AMS were responsible for the conception of the study and supervised the experimental work. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethical statement

All experimental venom collection procedures were approved by the Secretariat of the Environment, SEAM-Paraguay, Authorization No. 01/14.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

References

- Alfonso J.J., Kayano A.M., Garay A.F.G., Simões-Silva R., Sobrinho J.C., Vourliotis S., Soares A.M., Calderon L.A., Gómez M.C.V. Isolation, biochemical characterization and antiparasitic activity of BmatTX-IV, A basic Lys49-phospholipase A2 from the venom of Bothrops mattogrossensis from Paraguay. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2019;19:2041–2048. doi: 10.2174/1568026619666190723154756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrião-Escarso S.H., Soares A.M., Rodrigues V.M., Angulo Y., Díaz C., Lomonte B., Gutiérrez J.M., Giglio J.R. Myotoxic phospholipases A2 in Bothrops snake venoms: effect of chemical modifications on the enzymatic and pharmacological properties of bothropstoxins from Bothrops jararacussu. Biochimie. 2000;82:755–763. doi: 10.1016/S0300-9084(00)01150-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araya C., Lomonte B. Antitumor effects of cationic synthetic peptides derived from Lys49 phospholipase A2 homologues of snake venoms. Cell Biol. Int. 2007;31:263–268. doi: 10.1016/j.cellbi.2006.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashley E.A., Dhorda M., Fairhurst R.M., Amaratunga C., Lim P., Suon S., Sreng S., Anderson J.M., Mao S., Sam B., Sopha C., Chuor C.M., Nguon C., Sovannaroth S., Pukrittayakamee S., Jittamala P., Chotivanich K., Chutasmit K., Suchatsoonthorn C. Spread of artemisinin resistance in Plasmodium falciparum malaria. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014;371:411–423. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1314981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao Y., Bu P., Jin L., Hongxia W., Yang Q., An L. Purification, characterization and gene cloning of a novel phospholipase A2 from the venom of Agkistrodon blomhoffii ussurensis. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2005;37:558–565. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2004.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bézivin C., Tomasi S., Lohezic-Le Devehat F., Boustie J. Cytotoxic activity of some lichen extracts on murine and human cancer cell lines. Phytomedicine. 2003;10:499–503. doi: 10.1078/094471103322331458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhumiratana A., Intarapuk A., Sorosjinda-Nunthawarasilp P., Maneekan P., Koyadun S. Border malaria associated with multidrug resistance on Thailand-Myanmar and Thailand-Cambodia borders: transmission dynamic, vulnerability, and surveillance. BioMed Res. Int. 2013;(13) doi: 10.1155/2013/363417. 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bustillo S., Fernández J., Chaves-Araya S., Angulo Y., Leiva L.C., Lomonte B. Isolation of two basic phospholipases A2 from Bothrops diporus snake venom: comparative characterization and synergism between Asp49 and Lys49 variants. Toxicon. 2019;168:113–121. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2019.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castillo J.C.Q., Vargas L.J., Segura C., Gutiérrez J.M., Pérez J.C.A. In vitro antiplasmodial activity of phospholipases A2 and a phospholipase homologue isolated from the venom of the snake Bothrops asper. Toxins. 2012;4:1500–1516. doi: 10.3390/toxins4121500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cecilio A.B., Caldas S., De Oliveira R.A., Santos A.S.B., Richardson M., Naumann G.B., Schneider F.S., Alvarenga V.G., Estevão-Costa M.I., Fuly A.L., Eble J.A., Sanchez E.F. Molecular characterization of Lys49 and Asp49 phospholipases A2 from snake venom and their antiviral activities against Dengue virus. Toxins. 2013;5:1780–1798. doi: 10.3390/toxins5101780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox F. History of the discovery of the malaria parasites and their vectors. Parasites Vectors. 2010;3:1–9. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-3-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis E.A., Cao J., Hsu Y.-H., Magrioti V., Kokotos G. Phospholipase A2 enzymes: physical structure, biological function, disease implication, chemical inhibition, and therapeutic intervention. Chem. Rev. 2011;111:6130–6185. doi: 10.1021/cr200085w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gay C., Sanz L., Calvete J.J., Pla D. Snake venomics and antivenomics of Bothrops diporus, a medically important pitviper in northeastern Argentina. Toxins. 2015;8:1–13. doi: 10.3390/toxins8010009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabner A.N., Alfonso J., Kayano A.M., Moreira-Dill L.S., dos Santos A.P.D.A., Caldeira C.A.S., Sobrinho J.C., Gómez A., Grabner F.P., Cardoso F.F., Zuliani J.P., Fontes M.R.M., Pimenta D.C., Gómez C.V., Teles C.B.G., Soares A.M., Calderon L.A. BmajPLA2-II, a basic Lys49-phospholipase A2 homologue from Bothrops marajoensis snake venom with parasiticidal potential. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017;102 doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillaume C., Deregnaucourt C., Clavey V., Schrével J. Anti-Plasmodium properties of group IA, IB, IIA and III secreted phospholipases A2 are serum-dependent. Toxicon. 2004;43:311–318. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2004.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez J.M., Lomonte B. Phospholipases A2: unveiling the secrets of a functionally versatile group of snake venom toxins. Toxicon: Off. J. Int. Soc. Toxinol. 2013;62:27–39. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2012.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey A.L., Bradley K.N., Cochran S.A., Rowan E.G., Pratt J.A., Quillfeldt J.A., Jerusalinsky D.A. What can toxins tell us for drug discovery? Toxicon. 1998;36:1635–1640. doi: 10.1016/S0041-0101(98)00156-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey A.L., Edrada-Ebel R., Quinn R.J. The re-emergence of natural products for drug discovery in the genomics era. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2015;14:111–129. doi: 10.1038/nrd4510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holzer M., Mackessy S.P. An aqueous endpoint assay of snake venom phospholipase A2. Toxicon. 1996;34:1149–1155. doi: 10.1016/0041-0101(96)00057-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsuno K., Burrows J.N., Duncan K., Van Huijsduijnen R.H., Kaneko T., Kita K., Mowbray C.E., Schmatz D., Warner P., Slingsby B.T. Hit and lead criteria in drug discovery for infectious diseases of the developing world. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2015 doi: 10.1038/nrd4683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kini R.M. Excitement ahead: structure, function and mechanism of snake venom phospholipase A2 enzymes. Toxicon: Off. J. Int. Soc. Toxinol. 2003;42:827–840. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2003.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kini R.M., Fox J.W. Milestones and future prospects in snake venom research. Toxicon. 2013;62:1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2012.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh D., Armugam A., Jeyaseelan K. Snake venom components and their applications in biomedicine. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2006;63:3030–3041. doi: 10.1007/s00018-006-6315-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krizaj L., Bieber A.L., Anka R., Franc G. The primary structure of ammodytin L, a myotoxic phospholipase A2 homologue from Vipera ammodytes venom. Biochem. Soc. Symp. 1970;30:29–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1991.tb16485.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli U.K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambros C., Vanderberg J.P. Synchronization of Plasmodium falciparum erythrocytic stages in culture. J. Parasitol. 1979;65:418–420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomonte B., Angulo Y., Calderón L. An overview of lysine-49 phospholipase A2 myotoxins from crotalid snake venoms and their structural determinants of myotoxic action. Toxicon. 2003 doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2003.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomonte B., Fernández J., Sanz L., Angulo Y., Sasa M., Gutiérrez J.M., Calvete J.J. Venomous snakes of Costa Rica: biological and medical implications of their venom proteomic profiles analyzed through the strategy of snake venomics. Journal of Proteomics. 2014. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lomonte B., Gutiérrez J.M. Phospholipases A2 from viperidae snake venoms: how do they induce skeletal muscle damage? Acta Chim. Slov. 2011;58:647–659. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maraganore J.M., Merutka G., Cho W., Welches W., Kézdy F.J., Heinrikson R.L. A new class of phospholipases A2 with lysine in place of aspartate 49. Functional consequences for calcium and substrate binding. J. Biol. Chem. 1984;259:13839–13843. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathenge P.G., Low S.K., Vuong N.L., Mohamed M.Y.F., Faraj H.A., Alieldin G.I., Al khudari R., Yahia N.A., Khan A., Diab O.M., Mohamed Y.M., Zayan A.H., Tawfik G.M., Huy N.T., Hirayama K. Efficacy and resistance of different artemisinin-based combination therapies: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Parasitol. Int. 2020;74 doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2019.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mebs D., Kuch U., Coronas F.I.V., Batista C.V.F., Gumprecht A., Possani L.D. Biochemical and biological activities of the venom of the Chinese pitviper Zhaoermia mangshanensis, with the complete amino acid sequence and phylogenetic analysis of a novel Arg49 phospholipase A2 myotoxin. Toxicon: Off. J. Int. Soc. Toxinol. 2006;47:797–811. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2006.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosmann T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J. Immunol. Methods. 1983;65:55–63. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nava-Zuazo C., Estrada-Soto S., Guerrero-Álvarez J., León-Rivera I., Molina-Salinas G.M., Said-Fernández S., Chan-Bacab M.J., Cedillo-Rivera R., Moo-Puc R., Mirón-López G., Navarrete-Vazquez G. Design, synthesis, and in vitro antiprotozoal, antimycobacterial activities of N-{2-[(7-chloroquinolin-4-yl)amino]ethyl}ureas. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2010;18:6398–6403. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2010.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nevin R.L., Croft A.M. Psychiatric effects of malaria and anti-malarial drugs: historical and modern perspectives. Malar. J. 2016 doi: 10.1186/s12936-016-1391-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman D.J., Cragg G.M. Natural products as sources of new drugs from 1981 to 2014. J. Nat. Prod. 2016 doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.5b01055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunes D.C., Figueira M.M., Lopes D., De Souza D., Al E. BnSP-7 toxin, a basic phospholipase A2 from Bothrops pauloensis snake venom, interferes with proliferation, ultrastructure and infectivity of Leishmania (Leishmania) amazonensis. Parasitology. 2013;140:44–54. doi: 10.1017/S0031182013000012. Nunes DC, Figueira MM, Lopes DS, DE Souza DL, et al. Parasitology 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okombo J., Chibale K. Antiplasmodial drug targets: a patent review (2000-2013) Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2016;26:107–130. doi: 10.1517/13543776.2016.1113258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Organization, W.H World malaria report [WWW Document] 2020. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/malaria URL.

- Ownby C.L., Selistre de Araujo H.S., White S.P., Fletcher J.E. Lysine 49 phospholipase A2 proteins. Toxicon. Off. J. Int. Soc. Toxinol. 1999;37:411–445. doi: 10.1016/s0041-0101(98)00188-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simoes-Silva R., Alfonso J., Gomez A., Holanda R.J., Sobrinho J.C., Zaqueo K.D., Moreira-Dill L.S., Kayano A.M., Grabner F.P., da Silva S.L., Almeida J.R., Stabeli R.G., Zuliani J.P., Soares A.M. Snake venom, A natural library of new potential therapeutic molecules: challenges and current perspectives. Curr. Pharmaceut. Biotechnol. 2018;19:308–335. doi: 10.2174/1389201019666180620111025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smilkstein M., Sriwilaijaroen N., Kelly J.X., Wilairat P., Riscoe M. Simple and inexpensive fluorescence-based technique for high-throughput antimalarial drug screening. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2004;48:1803–1806. doi: 10.1128/aac.48.5.1803-1806.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soares A.M., Andrião-Escarso S.H., Angulo Y., Lomonte B., Gutiérrez J.M., Marangoni S., Toyama M.H., Arni R.K., Giglio J.R. Structural and functional characterization of myotoxin I, a Lys49 phospholipase A2 homologue from Bothrops moojeni (Caissaca) snake venom. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2000;373:7–15. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1999.1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soares A.M., Guerra-Sá R., Borja-Oliveira C.R., Rodrigues V.M., Rodrigues-Simioni L., Rodrigues V.M., Fontes M.R., Lomonte B., Gutiérrez J.M., Giglio J.R. Structural and functional characterization of BnSP-7, a Lys49 myotoxic phospholipase A2 homologue from Bothrops neuwiedi pauloensis venom. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2000;378:201–209. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2000.1790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soares A.M., Rodrigues V.M., Homsi-Brandeburgo M.I., Toyama M.H., Lombardi F.R., Arni R.K., Giglio J.R. A rapid procedure for the isolation of the LYS-49 myotoxin II from Bothrops moojeni (caissaca) venom: biochemical characterization, crystallization, myotoxic and edematogenic activity. Toxicon. 1998;36:503–514. doi: 10.1016/s0041-0101(97)00133-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stábeli R.G., Amui S.F., Sant'Ana C.D., Pires M.G., Nomizo A., Monteiro M.C., Romão P.R.T., Guerra-Sá R., Vieira C.a., Giglio J.R., Fontes M.R.M., Soares A.M. Bothrops moojeni myotoxin-II, a Lys49-phospholipase A2 homologue: an example of function versatility of snake venom proteins. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2006;142:371–381. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpc.2005.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stábeli R.G., Simoes-Silva R., Kayano A.M., Gimenez G.S., Moura A.A., Caldeira C.A. da S., Coutinho-Neto A., Zaqueo K.D., Zuliani J.P., Soares A.M., Calderon L.A. Purification of phospholipases A2 from American snake venoms. In: Calderon Leonardo de Azevedo., editor. Chromatography - the Most Versatile Method of Chemical Analysis. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Su X.Z., Miller L.H. The discovery of artemisinin and the nobel prize in physiology or medicine. Science China. Life Sci. 2015;58:1175–1179. doi: 10.1007/s11427-015-4948-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teixera L.F., de Carvalho L.H., de Castro O.B., Bastos J.S.F., Néry N.M., Oliveira G.A., Kayano A.M., Soares A.M., Zuliani J.P. Local and systemic effects of BdipTX-I, a Lys-49 phospholipase A2 isolated from Bothrops diporus snake venom. Toxicon. 2018;141:55–64. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2017.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thieleke-Matos C., Lopes da Silva M., Cabrita-Santos L., Portal M.D., Rodrigues I.P., Zuzarte-Luis V., Ramalho J.S., Futter C.E., Mota M.M., Barral D.C., Seabra M.C. Host cell autophagy contributes to Plasmodium liver development. Cell Microbiol. 2016;18:437–450. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trager W., Jensen J.B. Human malaria parasites in continuous culture. Science. 1976;193:673–675. doi: 10.1126/science.781840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C., Qin X., Huang B., He F., Zeng C. Hemolysis of human erythrocytes induced by melamine-cyanurate complex. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2010;402:773–777. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.10.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wongsrichanalai C., Pickard A.L., Wernsdorfer W.H., Meshnick S.R. Epidemiology of drug-resistant malaria. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2002 doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(02)00239-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J.-H., Chung T.D.Y., Oldenburg K.R. A simple statistical parameter for use in evaluation and validation of high throughput screening assays. J. Biomol. Screen. 1999;4:67–73. doi: 10.1177/108705719900400206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zieler H., Keister D.B., Dvorak J.A., Ribeiro J.M.C. A snake venom phospholipase A2 blocks malaria parasite development in the mosquito midgut by inhibiting ookinete association with the midgut surface. J. Exp. Biol. 2001;204:4157–4167. doi: 10.1242/jeb.204.23.4157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.