Abstract

Drug-induced liver chemistry abnormalities, primarily transaminase elevations, are commonly observed in pazopanib-treated patients. This meta-analysis characterises liver chemistry abnormalities associated with pazopanib. Data of pazopanib-treated patients from nine prospective trials were integrated (N = 2080). Laboratory datasets were used to characterise the incidence, timing, recovery and patterns of liver events, and subsequent rechallenge with pazopanib. Severe cases of liver chemistry abnormalities were clinically reviewed. Multivariate analyses identified predisposing factors. Twenty percent of patients developed elevated alanine aminotransferase (ALT) >3×ULN. Incidence of peak ALT >3–5×ULN, >5–8×ULN, >8–20×ULN and >20×ULN was 8%, 5%, 5% and 1%, respectively. Median time to onset for all events was 42 days; 91% of events were observed within 18 weeks. Recovery rates based on peak ALT >3–5×ULN, >5–8×ULN, >8–20×ULN and >20×ULN were 91%, 90%, 90% and 64%, respectively. Median time from onset to recovery was 30 days, but longer in patients without dose interruption. Based on clinical review, no deaths were associated with drug-induced liver injury. Overall, 38% of rechallenged patients had ALT elevation recurrence, with 9-day median time to recurrence. Multivariate analysis showed that older age was associated with development of ALT >8×ULN. There was no correlation between hypertension and transaminitis. Our data support the current guidelines on regular liver chemistry tests after initiation of pazopanib, especially during the first 9 or 10 weeks, and also demonstrate the safety of rechallenge with pazopanib.

Keywords: Hepatotoxicity, Drug-induced liver injury, ALT elevation, Hyperbilirubinemia

1. Introduction

Pazopanib, a multi-targeted vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR) tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI), is an effective treatment for advanced renal cell carcinoma (RCC) and soft tissue sarcoma (STS) [1]. While hepatotoxicity is an adverse event (AE) associated with a majority of approved TKIs, it appears to be particularly significant for lapatinib, pazopanib, ponatinib, regorafenib and sunitinib, each requiring a boxed label warning [2]. The precise mechanism of liver injury with TKIs is poorly understood [3–5] and requires further investigation.

Hepatotoxicity associated with pazopanib treatment commonly presents as isolated transaminase or total bilirubin elevations. The observed incidence of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) elevations in pazopanib-treated patients ranged from 46% to 60% for all grades (NCICTCAE v3.0), 8–15% for grade 3 and <1–2% for grade 4; similar rates were observed for aspartate aminotransferase (AST) elevations [1,6–8]. Total bilirubin elevations associated with pazopanib treatment were primarily grade 1 or 2, isolated hyperbilirubinemia that was considered to be associated with pazopanib inhibition of uridine-diphosphoglucuronate glucuronosyltransferase 1A1 (UGT1A1) combined with polymorphism of the UGT1A1 gene, such as Gilbert’s syndrome [9,10]. Approximately 2% of pazopanib-treated patients versus ⩽1% of placebo-treated patients met laboratory criteria for Hy’s law [1,8].

Hy’s law cases, defined as concurrent ALT elevation of greater than 3 times the upper limit of normal (>3×ULN) and total bilirubin ⩾2×ULN with no evidence of biliary obstruction (i.e. without significant elevation of alkaline phosphatase [ALP]), and with other causes excluded, harbour significant risk of developing severe drug-induced liver injury (DILI) and have been associated with ~10% fatality rate [11–13].

Although some features of pazopanib-induced hepatotoxicity have been identified, such as early occurrence and reversibility [1], much remains to be elucidated, including mechanisms of induction, factors predictive of development, and other features. More detailed characterisation of the onset, recovery, and rechallenge of liver events based on severity categories are also needed to help clinicians optimise treatment management for patients. Our meta-analyses address these issues using integrated data from 2080 patients with advanced cancer who received pazopanib in clinical studies.

2. Methods

2.1. Data source

Nine prospective Phase II and III GlaxoSmithKlinesponsored clinical studies that evaluated efficacy and safety of pazopanib monotherapy in patients with advanced cancer were selected [6–8,14–16] (Supplementary Table A1); data were integrated for all patients who received ⩾1 pazopanib dose (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline demography, disease characteristics and pazopanib exposure by tumour type.

| Parameters | RCC population N = 1149 |

STS population N = 382 |

Ovarian population N = 549 |

Total N = 2080 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median age, years (range) | 60 (18–88) | 54 (18–83) | 55 (22–80) | 58 (18–88) |

| Age groups, n (%) | ||||

| <50 years | 172 (15) | 142 (37) | 165 (30) | 479 (23) |

| 50 to <60 years | 362 (32) | 102 (27) | 183 (33) | 647 (31) |

| 60 to <70 years | 377 (33) | 92 (24) | 154 (28) | 623 (30) |

| ⩾70 years | 238 (21) | 46 (12) | 47 (9) | 331 (16) |

| Gender | ||||

| Male, n (%) | 811 (71) | 168 (44) | 0 | 979 (47) |

| Race, n (%)a | ||||

| White | 846 (74) | 169 (70) | 367 (67) | 1382 (71) |

| Asian | 281 (24) | 57 (24) | 179 (33) | 517 (27) |

| Other | 21 (2) | 5 (2) | 3 (1) | 29 (1) |

| Baseline liver metastasis, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 212 (18) | 97 (25) | 17 (3) | 326 (16) |

| Baseline liver chemistry, n (%) | ||||

| ALT ⩽ULN/>ULN | 1058 (92)/87 (8) | 337 (88)/45 (12) | 512 (93)/35 (6) | 1907 (92)/167 (8) |

| Total bilirubin ⩽ULN/>ULN | 1099 (96)/49 (4) | 368 (96)/13 (3) | 538 (98)/10 (2) | 2005 (96)/72 (3) |

| ALP ⩽ULN/>ULN | 912 (79)/230 (20) | 264 (69)/116 (30) | 506 (92)/34 (6) | 1682 (81)/380 (18) |

| Baseline performance status, n (%) | ||||

| ECOG 0–1/2 | 585 (98)/10 (2) | NA | 547 (>99)/2 (<1) | 1132 (99)/12 (1) |

| KPS 100-90/80-70 | 411 (74)/137 (25) | NA | NA | 411 (74)/137 (25) |

| WHO 0–1/2 | NA | 381 (>99)/1 (<1) | NA | 381 (>99)/1 (<1) |

| Maximum duration of pazopanib treatment, n (%) | ||||

| <6 weeks | 115 (10) | 69 (18) | 108 (20) | 292 (14) |

| 6 to <12 weeks | 128 (11) | 60 (16) | 71 (13) | 259 (12) |

| 12 to <24 weeks | 205 (18) | 104 (27) | 58 (11) | 367 (18) |

| >24 weeks | 701 (61) | 149 (39) | 312 (57) | 1162 (56) |

Abbreviations: ALP, alkaline phosphatase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; KPS, Karnofsky performance score; NA, not available; RCC, renal cell carcinoma; STS, soft tissue sarcoma; ULN, upper limit of normal range; WHO, World Health Organization.

Race was not collected in STS study VEG20002 (n = 142).

2.2. Liver chemistry monitoring

Most studies had ALT/AST entry criteria of ⩽2.5×ULN and total bilirubin entry criteria of ⩽1.5×ULN. Routine liver chemistry panels included ALT, AST, ALP, and total bilirubin with bilirubin fractionation required when total bilirubin was >1.5×ULN or >2×ULN. Post-baseline liver chemistry tests were generally performed every 3 or 4 weeks. Earlier studies included Day 8 testing. For isolated ALT >3–8×ULN, study treatment could continue with liver chemistry monitored until normalisation or stabilisation; for isolated ALT >8ULN, dose would be interrupted and liver chemistry properly monitored, with rechallenge attempted only if clinical benefit had been observed. For concurrent ALT >3×ULN and total bilirubin ⩾2×ULN with >35% direct bilirubin or with hypersensitivity (i.e. potential Hy’s law cases), dosing was permanently discontinued and patients were further evaluated to exclude other causes.

2.3. Data analyses

2.3.1. Characterisation of liver chemistry abnormalities

Incidence of ALT, AST, total bilirubin and ALP elevations was based on peak values calculated as a multiple of ULN. Per FDA guidance on drug-induced liver injury, transaminases >3×ULN were considered events of clinical significance [17] and were further categorised based on peak values of >3–5×ULN, >5–8×ULN, >8–20×ULN and >20×ULN. Because ALT is considered hepatic specific, ALT was used instead of AST for characterisation of the liver events [18]. Patients with baseline ALT >2.5×ULN were excluded. Concurrent ALT >3×ULN and total bilirubin ⩾2×ULN was defined as total bilirubin ⩾2×ULN occurring at or within 28 days of ALT >3×ULN.

Time course of the first ALT >3×ULN events was characterised for time to onset, defined as time from first dose of pazopanib to onset of the event,and for time from onset to recovery, defined as time from event onset until ALT returned to ⩽2.5×ULN. The mean and median(with 5th and 95th percentile) times to onset and recovery were calculated. Cumulative incidence of ALT elevations over time was displayed in curves; weekly incidence of ALT elevations was displayed as bar graphs for studies with the same liver assessment schedules.

Outcome of the first ALT >3×ULN events was categorised as recovery, defined as ALT returned to ⩽2.5×ULN. Outcomes were further categorised as: recovery with dose interruption or without dose interruption; adaptation, a subgroup of patients who recovered to normalised (<ULN) ALT or baseline grade without dose interruption; no recovery, defined as no laboratory data documenting ALT return to ⩽2.5×ULN. For those who recovered, duration of pazopanib treatment since recovery was calculated. Outcomes of rechallenge with pazopanib included positive rechallenge (ALT >3×ULN recurred) or negative rechallenge (ALT >3×ULN did not recur). Time to recurrence and factors that might predict recurrence, such as baseline characteristics, onset timing, and severity of the first events, were evaluated.

Patterns of liver injury were categorised based on the calculated R ratio into hepatocellular (R ⩾ 5), cholestatic (R ⩽ 2) or mixed (R ⩾ 2 and R < 5) patterns, where R = (peak ALT in ULN)/(ALP in ULN from the same date) [19]. If ALP was missing for the peak ALT ×ULN, the highest ALT ×ULN with a non-missing ALP was used.

2.3.2. Multivariate analysis to identify potential predictive factors of ALT elevation

Nine baseline candidate factors including gender, age, race, ALT level, liver metastasis status, prior anticancer therapy, paracetamol/acetaminophen use, tumour type and performance status were identified and examined in stepwise logistic regression analysis to evaluate association with occurrence of ALT >3×ULN, >5×ULN and >8×ULN events, respectively. Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals were presented for all terms remaining in the model.

Correlation of onset of ALT >3×ULN and hypertension or use of paracetamol within the first 12 weeks was assessed using chi-squared tests. The association of clinical symptoms with ALT elevation was assessed by comparing the incidence of a group of selected AEs (including abdominal pain, abdominal pain upper, nausea, vomiting, decreased appetite/anorexia, jaundice, pyrexia, rash/pruritus) between week 2 and 12 in patients with or without ALT >3×ULN during this time frame.

2.3.3. Clinical review and adjudication for potential Hy’s law and cases with no recovery

Cases meeting laboratory criteria for Hy’s law were clinically evaluated by Dr. Kaplowitz (expert hepatologist) based on available clinical, laboratory and UGT1A1 genotyping data. Liver chemistry abnormalities were first adjudicated for potential association with pazopanib-induced liver injury based on the causality criteria by DILI Network [20,21]. Cases with DILI possibly, probably or likely associated with pazopanib treatment were further evaluated for confirming Hy’s law [13,22]. Input from Dr. Powles (medical oncologist) was obtained from clinical perspective for advanced cancer patients.

Cases with no laboratory data documenting ALT recovery were clinically reviewed to determine reasons for no recovery, such as death or lost/inadequate follow-up. Patients who died of liver failure or with liver chemistry abnormalities at the time of death were clinically adjudicated by two hepatologists, Dr. Kaplowitz and Dr. Norry, for potential association with pazopanib-induced liver injury.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline data

Baseline demographics, disease characteristics and maximum duration of pazopanib treatment at various time points were summarised for the integrated dataset and categorised by tumour types (Table 1). Major demographic differences were age and gender. The RCC and STS populations had higher incidences of baseline liver metastasis and abnormal ALP; the latter might reflect a high incidence of bone metastasis. The RCC population had a lower early treatment discontinuation rate.

3.2. Liver chemistry abnormalities

3.2.1. Incidence and severity

The total incidence of ALT >3×ULN events in pazopanib-treated patients was 20% (Table 2). ALT elevation based on peak values of >3–5×ULN, >5– 8×ULN, >8–20×ULN and >20×ULN occurred in 8%, 5%, 5% and 1% of patients, respectively. The overall incidence of total bilirubin ⩾2×ULN was 6%. Thirtysix patients (1.8%) had laboratory data showing concurrent ALT >3×ULN and total bilirubin ⩾2×ULN. These cases were clinically adjudicated for Hy’s law (see Section 3.4). Supplementary Table A2 shows the incidence of liver chemistry abnormalities in four randomised studies for comparative purposes.

Table 2.

Incidence of liver chemistry abnormalities in pazopanib-treated patients by tumour type, n (%).a

| Liver chemistry parameters based on peak values | RCC N = 1149 |

Sarcoma N = 382 |

Ovarian N = 549 |

Total N = 2080 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALT >3×ULNb | 259 (23) | 55 (15) | 94 (18) | 408 (20) |

| ALT >3–5×ULN | 100 (9) | 26 (7) | 40 (8) | 166 (8) |

| ALT >5–8×ULN | 63 (6) | 13 (3) | 26 (5) | 102 (5) |

| ALT >8–20×ULN | 76 (7) | 11 (3) | 24 (5) | 111 (5) |

| ALT >20×ULN | 20 (2) | 5 (1) | 4 (<1) | 29 (1) |

| AST >3×ULNb | 185 (16) | 45 (12) | 64 (12) | 294 (14) |

| AST >3–5×ULN | 74 (7) | 21 (6) | 38 (7) | 133 (7) |

| AST >5–8×ULN | 55 (5) | 9 (2) | 8 (2) | 72 (4) |

| AST >8–20×ULN | 44 (4) | 9 (2) | 15 (3) | 68 (3) |

| AST >20×ULN | 12 (1) | 6 (2) | 3 (<1) | 21 (1) |

| Total bilirubin ⩾2×ULN | 77 (7) | 29 (8) | 17 (4) | 123 (6) |

| Concurrent ALT >3×ULNb and total bilirubin ⩾2×ULN | 26 (2.3) | 7 (1.9) | 3 (0.6) | 36 (1.8) |

| ALP ⩾2×ULN | 137 (13) | 79 (21) | 20 (4) | 236 (11) |

| With baseline ALP >ULN | 75 (7) | 68 (18) | 6 (1) | 149 (7) |

Abbreviations: ALP, alkaline phosphatase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; RCC, renal cell carcinoma; ULN, upper limit of normal range.

Denominator used for calculating the incidence rate of each liver chemistry abnormality was patients who received at least one dose of pazopanib treatment and had at least one laboratory assessment for that parameter.

Rates were based on ALT or AST >3×ULN and baseline <2.5×ULN.

3.2.2. Time to onset of the first ALT >3×ULN events

Median time to onset for all events was 42 days (5th– 95th percentile: 20–182). Median time to onset for ALT >3–5×ULN, >5–8×ULN, >8–20×ULN and >20×ULN group was 45 days (5th–95th percentile: 20250), 40 days (5th–95th percentile: 20–179), 29 days (5th–95th percentile: 20–113) and 29 days (5th–95th percentile: 15–144), respectively; times were shorter in the more severe groups (Table 3).

Table 3.

Time course, outcome and pattern of the first ALT >3×ULN events in pazopanib-treated patients.

| The first ALT events based on peak ALT value |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALT >3–5×ULN N = 174 |

ALT >5–8×ULN N = 99 |

ALT >8–20×ULN N = 107 |

ALT >20×ULN N = 28 |

ALL ALT >3×ULN N = 408 |

|

| Time to onset, days | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 83.9 (130.05) | 58.3 (76.87) | 49.9 (70.37) | 42.8 (37.97) | 65.9 (101.26) |

| Median (5th–95th percentile) | 44.5 (20–250) | 40.0 (20–179) | 29.0 (20–113) | 29.0 (15–144) | 42.0 (20–182) |

| Outcome of the first elevation events | |||||

| Recovered, n (%) of total events in each category | 159 (91) | 89 (90) | 96 (90)a | 18 (64)a | 362 (89)a |

| Recovered with dose interruption, n* (%)b | 64 (40) | 50 (56) | 64 (67) | 12 (67) | 190 (52) |

| Recovered without dose interruption, n* (%)b | 84 (53) | 31 (35) | 12 (13) | 0 | 127 (36) |

| Onset after last dose of pazopanib, n* (%)b | 11 (7) | 8 (9) | 20 (21) | 6 (33) | 44 (12) |

| No recovery, n (%) of total events in each category | 15 (9) | 10 (10) | 11 (10) | 13 (36) | 46 (11) |

| Time from onset to recovery, days | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 49.9 (51.07) | 53.6 (49.76) | 38.6 (30.83) | 32.1 (16.19) | 47.1 (45.57) |

| Median (5th–95th percentile) | 30.0 (7–168) | 34.0 (8–169) | 29.0 (14–113) | 28.0 (19–85) | 30.0 (8–155) |

| Time from onset to recovery with dose interruption | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 34.6 (38.40) | 47.0 (52.97) | 39.5 (32.57) | 27.9 (9.01) | 39.3 (40.51) |

| Median (5th–95th percentile) | 22.0 (7–102) | 29.0 (8–196) | 30.0 (13–102) | 22.0 (19–43) | 29.0 (8–136) |

| Time from onset to recovery without dose interruption | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 65.2 (56.72) | 72.3 (43.58) | 58.2 (33.22) | – | 66.3 (51.81) |

| Median (5th–95th percentile) | 43.0 (9–181) | 64.0 (22–169) | 50.0 (14–115) | – | 45.0 (14–169) |

| Duration of pazopanib treatment after recovery | |||||

| All recovered with treatment continued | n = 134 | n = 71 | n = 57 | n = 7 | n = 269 |

| Median (5th–95th percentile), days | 236.5 (22–867) | 237 (13–900) | 110 (4–702) | 22 (6–385) | 195 (8–867) |

| Recovered with dose interruption | n = 52 | n = 43 | n = 45 | n = 7 | n = 147 |

| Median (5th–95th percentile), days | 261.5 (28–895) | 198 (13–952) | 89 (4–688) | 22 (6–385) | 186 (6–879) |

| Recovered without dose interruption | n = 82 | n = 28 | n = 12 | n = 0 | n = 122 |

| Median (5th–95th percentile), days | 192.5 (21–836) | 250.5 (60–790) | 118.5 (14–924) | – | 218.5 (21–843) |

| Pattern of the first ALT elevation events, n (%) | |||||

| Ratio = (ALT ×ULN)/ALP ×ULN) | |||||

| Hepatocellular (ratio ⩾5) | 71 (41) | 68 (69) | 83 (78) | 24 (86) | 246 (60) |

| Mixed (ratio >2 to <5) | 77 (44) | 25 (25) | 19 (18) | 3 (11) | 124 (30) |

| Cholestasis (ratio ⩽2) | 26 (15) | 6 (6) | 5 (5) | 1 (4) | 38 (9) |

Abbreviations: ALP, alkaline phosphatase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; SAE, serious adverse event; SD, standard deviation; ULN, upper limit of normal range.

Seven patients, three in the ALT >20×ULN group and 4 in the ALT >8–20×ULN group, demonstrated recovery based on laboratory data recorded in the SAE narratives rather than in the laboratory dataset. The time courses of onset and recovery were only based on data from laboratory datasets.

The n* (%) of recovery in each subcategory is from all recovered.

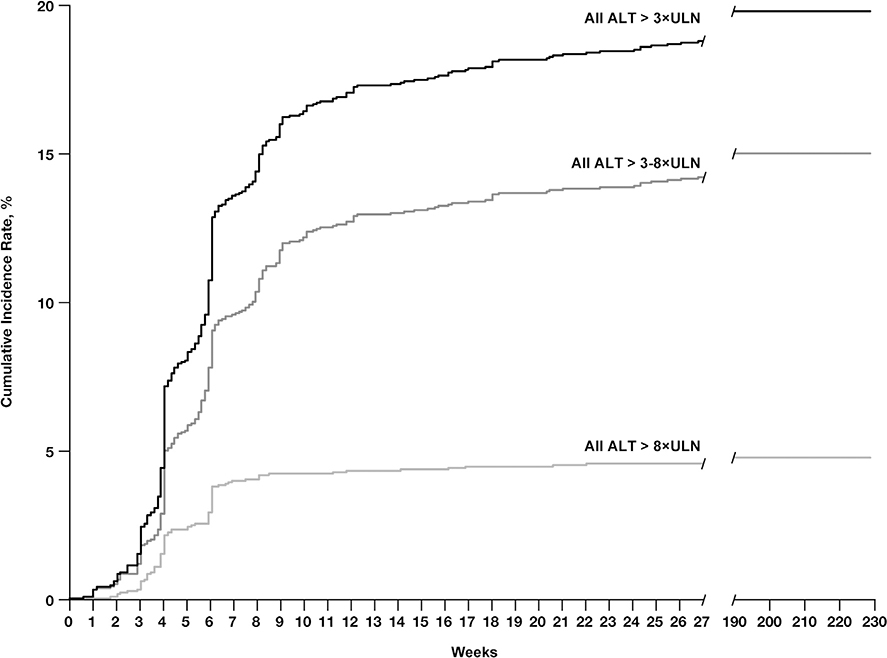

Fig. 1 shows the cumulative incidence of ALT elevations over time, with 81% and 91% of the events observed by the end of 9 and 18 weeks, respectively. The incidence rate of ALT >3×ULN at week 1 and week 2 was <1% and 1%, respectively (data not shown). Supplementary Fig. A1 shows the incidence of ALT elevations at specific time points in studies grouped based on the same liver chemistry test schedules.

Fig. 1.

Cumulative incidence rate of ALT elevations over time for all ALT >3×ULN events (black line), all ALT >8×ULN events (medium grey line), and all ALT >3–8×ULN events (light grey line) in pazopanib-treated patients from the integrated database (N = 2080). Abbreviations: ALT, alanine aminotransferase; ULN, upper limit of normal range.

3.2.3. Outcome of the first ALT >3ULN events

Of 408 patients with ALT >3ULN, 89% (n = 362) had subsequent laboratory data that demonstrated recovery of elevated ALT to <2.5×ULN (Table 3). Recovery rates based on peak ALT >3–5×ULN, >5–8×ULN, >8–20×ULN and >20×ULN were 91%, 90%, 90% and 64%, respectively. Among the 362 patients who recovered from ALT >3×ULN, 52% (n = 190) recovered with dose interruption, which included any interruptions due to any reasons; 36% (n = 127) recovered without dose interruption, including 96 patients (24% of all recovered) who demonstrated adaptation (defined in Section 2). More patients with less severe ALT elevation recovered without dose interruption. All patients in the ALT >20×ULN group had dose interruption or discontinuation.

Based on the laboratory dataset, 46 patients (11%) did not demonstrate recovery from ALT elevation. These cases were clinically reviewed for reasons of no recovery (see Section 3.5).

3.2.4. Time from onset to recovery and duration of pazopanib treatment after recovery

The median time from onset to recovery was 30 days (5th–95th percentile: 8–155) for all patients who recovered from the first ALT >3×ULN events (Table 3). There was no apparent difference between the four groups with peak ALT values. For patients with ALT >3×ULN, the median time to recovery was longer in those who recovered without dose interruption (median: 45 days; 5th–95th percentile: 14–169) than those who recovered with dose interruption (median: 29 days; 5th–95th percentile: 8–136). The median duration of pazopanib treatment following recovery was 195 days (5th–95th percentile: 8–867) for all recovered patients who continued treatment and 237 days for those groups with peak ALT values >3–5×ULN and >5–8×ULN.

3.2.5. Hepatic injury pattern and symptoms associated with first ALT >3×ULN events

AsshowninTable3and60%ofpatientsshowedapattern of hepatocellular injury (R ⩾ 5); 9% showed a pattern of cholestatic injury (R ⩽ 2); and 30% showed a mixed pattern of hepatocellular and cholestatic injury (R > 2 to R < 5). As these R values were calculated solely on liver chemistry without clinical evaluation for other causes, not all of these cases are due to DILI. It is worth noting that because this is an advanced cancer population, a substantial number of patients with post-baseline ALP ⩾2×ULN had baseline ALP >ULN (18% in STS, 7% in RCC; Table 1). Hence, some patients with baseline elevated ALP might be inappropriately categorised as having a mixed or cholestatic liver injury pattern if their ALP levels were not truly elevated from baseline.

Potential DILI-related symptoms were evaluated in patients with ALT elevations during the first 12 weeks versus those without. Results showed no apparent difference between the two groups, except that decreased appetite/anorexia was slightly higher in those with ALT elevation (Supplementary Table A3).

3.2.6. Rechallenge with pazopanib

Rechallenge with pazopanib was characterised for 103 patients who initially developed ALT >3×ULN and were rechallenged with pazopanib following ALT recovery to ⩽2.5×ULN. Of these 103 patients, 20 (19%) were rechallenged at the same dose as before ALT elevation and 83 (81%) were rechallenged at a reduced dose. Overall, 62 patients (60%) had negative rechallenge (i.e. no recurrence of ALT >3×ULN), 39 (38%) had positive rechallenge (ALT >3×ULN recurred), and 2 (2%) lacked follow-up data. Among the 39 patients with recurrence of ALT elevation, 8 (21%) recurred with ALT >8–20×ULN; none recurred with ALT >20×ULN. The median time to recurrence of ALT elevation was 9 days (5th–95th percentile: 5–248) after recommencing pazopanib. Of these 39 patients, 27 showed ALT fully recovered to ⩽ULN, seven recovered to >ULN but ⩽2.5×ULN, and five had last recorded ALT level of >2.5–5×ULN, including one patient who died due to hemoptysis associated with lung metastasis. There was no report of hepatic failure.

Comparison of the two groups with positive or negative rechallenge showed no significant differences in baseline characteristics (Table 4). However, patients with more severe first ALT level (ALT >8–20×ULN) may have higher risk of positive rechallenge.

Table 4.

Comparison of baseline characteristics and first ALT events between patients with positive or negative rechallenge.a

| ALT >3×ULN not recurred (negative rechallenge) n = 62 (60%) |

ALT >3×ULN recurred (positive rechallenge) n = 39 (38%) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | ||

| Mean (SD) | 59.1 (10.85) | 62.8 (9.42) |

| Median (min–max) | 59.5 (37–82) | 64.0 (36–82) |

| Gender, n (%) | ||

| Male | 35 (55) | 19 (49) |

| Race, n (%) | ||

| White | 42 (68) | 28 (74) |

| Asian | 18 (30) | 10 (26) |

| Other | 1 (2) | 0 |

| Peak category of the first ALT >3×ULN events, n (%) | ||

| ALT >3–5×ULN | 23 (36) | 10 (26) |

| ALT >5–8×ULN | 19 (30) | 9 (23) |

| ALT >8–20×ULN | 16 (25) | 18 (46) |

| ALT >20×ULN | 4 (6) | 2 (5) |

| Time to onset of the first ALT >3×ULN events, days | ||

| Mean (SD) | 55.5 (73.28) | 48.3 (36.92) |

| Median (min–max) | 42.0 (4–501) | 43.0 (15–225) |

| Time to recovery of the first ALT >3×ULN events, days | ||

| Mean (SD) | 23.3 (25.54) | 30.1 (28.91) |

| Median (min–max) | 19.5 (5–203) | 22.0 (4–152) |

| Rechallenged with reduced dose, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 47 (73) | 34 (87) |

| No | 15 (23) | 5 (13) |

| Time to recurrence of ALT >3×ULN following rechallenge | ||

| Median (5th–95th percentile) days | NA | 9.0 (5–248) |

Abbreviations: ALT, alanine aminotransferase; NA, not available; SD, standard deviation; ULN, upper limit of normal range.

Total of 103 patients were rechallenged: 62 without ALT >3×ULN recurrence, 39 with ALT >3×ULN recurrence; two lacked follow-up data after rechallenge.

3.3. Multivariate analysis to identify potential predictive factors of ALT elevation

Using logistic regression analysis, female gender, older age (⩾60), baseline ALT >ULN, no prior anticancer treatment (i.e. treatment-naive) and better baseline performance status were associated with a higher risk of developing ALT >3×ULN (Table 5). Only older age was retained as a predictive factor associated with a higher risk of developing ALT >8ULN.

Table 5.

Logistic regression analysis of variables associated with ALT elevations.

| All pazopanib-treated patients, N = 2080 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Covariate | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P value |

| First ALT >3×ULN | ||

| Gender: Female versus male | 1.3 (1.01–1.67) | 0.0456 |

| Age group: <60 versus ⩾60 years | 0.61 (0.49–0.77) | <0.001 |

| Baseline ALT: ⩽ULN versus >ULN | 0.53 (0.36–0.77) | <0.001 |

| Prior anticancer therapy: No versus Yes | 1.88 (1.45–2.43) | <0.001 |

| Baseline performance status: WHO/ECOG 0 or KPS 100-90 versus WHO/ECOG 1–2 or KPS <90 | 1.56 (1.22–2.00) | <0.001 |

| First ALT >5×ULN | ||

| Age group: <60 versus ⩾60 years | 0.61 (0.45–0.84) | 0.0024 |

| Baseline ALT: ⩽ULN versus >ULN | 0.6 (0.36–0.99) | 0.0476 |

| Prior anticancer therapy: No versus Yes | 1.45 (1.06–1.98) | 0.0188 |

| First ALT >8×ULN | ||

| Age group: <60 versus ⩾60 years | 0.56 (0.37–0.85) | 0.0072 |

Abbreviations: ALT, alanine aminotransferase; CI, confidence interval; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; KPS, Karnofsky performance score; ULN, upper limit of normal range; WHO, World Health Organization.

Correlation of ALT >3×ULN onset and use of paracetamol within the first 12 weeks was evaluated using chi-squared tests. Results showed a weak negative correlation between paracetamol use and onset of ALT elevation (Pearson chi-square P = 0.030, phi coefficient −0.048; Supplementary Table A4). Correlation of ALT elevation and occurrence of hypertension within the first 12 weeks was also evaluated by chi-squared tests, with no correlation demonstrated (Supplementary Table A5).

3.4. Clinical adjudication for cases with concurrent ALT and total bilirubin elevations

Thirty-seven patients were identified with concurrent ALT >3×ULN and total bilirubin ⩾2×ULN (36 identified from laboratory dataset in Table 2; one identified from laboratory data entered in serious AE narratives). Among these 37 cases, 25 were assessed as either possibly (n = 5), probably (n = 18) or highly likely (n = 2) to have pazopanib-related DILI. Nine of the 25 were assessed as meeting Hy’s law criteria, which was 0.4% of the integrated population. All 25 patients had ALT elevations recovered except for one patient whose last recorded ALT value was grade 2. Liver chemistry abnormalities in the remaining 12 cases were assessed as unlikely related to pazopanib treatment.

3.5. Clinical adjudication for cases with no recovery of the first ALT elevation

Forty-six patients (11%) had no laboratory data demonstrating recovery of ALT elevation (Table 3). Among these 46 patients, 9 died with elevated ALT (peak ALT >20×ULN, n = 6; peak ALT >8–20×ULN, n = 3). The causes of liver injury in these cases were assessed as unlikely associated with pazopanib, but were associated with multi-organ failures or ischaemic liver injuries related to end-stage progression of cancer. Therefore, the deaths were unlikely associated with pazopanib-related DILI.

Of the remaining 37 patients, 17 had laboratory data indicating ALT trending down to grade 2; the remaining 20 had no follow-up data available.

4. Discussion

This meta-analysis demonstrates that a majority of transaminase elevations in pazopanib-treated patients were isolated asymptomatic elevations that resolved with time. Events occurred irrespective of tumour type. The vast majority of events occurred 3–9 weeks after initiation of therapy (median 42 days). Overall, 6% of patients had ALT >8×ULN. The more severe ALT transaminitis occurred sooner after initiating pazopanib than less severe events.

The median time to normalisation of transaminitis occurred 30 days following onset, and the severity did not appear to affect the time to recovery. Treatment discontinuation accelerated recovery time and is recommended in more severe cases (>8×ULN); treatment can be continued with ALT <8×ULN but recovery time was 3–5 weeks longer than when treatment was interrupted. It is noteworthy that 36% of patients with pazopanib-associated transaminitis recovered to <2.5×ULN without dose interruptions, including a subgroup with normalised (<ULN) liver enzyme levels, a process called adaptation. This was particularly true in patients with mild transaminitis. This finding supports the guideline that dose interruption is required if transaminitis exceeds 8×ULN. The majority of patients with ALT <8×ULN continued pazopanib treatment after recovery from ALT elevation, with a median treatment duration of 237 days following recovery.

Analysis of 103 patients with transaminitis on pazopanib who were rechallenged after resolution of the event indicated that the majority of these patients (60%) were rechallenged successfully, underlining the apparent adaptation to therapy with time. If recurrence of the transaminitis did occur, it happened soon after reintroduction of treatment (median 9 days). There were no incidences of ALT >20×ULN and no cases of liver failure after rechallenge, underlining the safety of this approach; however, rechallenge should only be undertaken with close monitoring of liver chemistry. The likelihood of an ALT elevation >8×ULN after recovery and subsequent treatment is small, especially after longer periods of time, but it cannot be ruled out.

Multivariate analysis revealed specific subgroups of patients who were predisposed to develop transaminitis. Specifically, older age was associated with increased risk. Concomitant use of paracetamol did not show increased incidence of ALT elevation; however, paracetamol should still be used with caution because of its own risk of inducing liver injury. Finally, there was no correlation between hypertension and transaminitis, suggesting that transaminitis may be an off-target toxicity unrelated to the mechanism of action [23].

The incidence of Hy’s law cases was 0.4% by clinical review and adjudication, and no liver failure was identified as associated with pazopanib in this integrated dataset. Other cases with concurrent ALT and total bilirubin elevations were assessed as due to multi-organ failure or ischaemic liver injury related to end-stage cancer progression or UGT1A1 inhibition in patients with Gilbert’s syndrome rather than Hy’s law. Such diagnostic dilemmas in advanced cancer patients were also shared by others [2]; therefore, thorough clinical evaluation of such cases is warranted because, although rare, fatal liver failure has occurred with pazopanib [4].

Data from this meta-analysis support the current guidelines on regular liver chemistry tests after initiation of pazopanib, especially during the first 9–10 weeks, and also demonstrate that patients may be rechallenged with pazopanib with close monitoring of liver chemistries. An ongoing pharmacogenetic analysis may provide mechanistic insight into pazopanib-induced liver injury [24].

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the contributions of the following individuals from GlaxoSmithKline: Yan Wong, PharmD, for help with case narratives; Ellen Forman and Karrie Wang, PhD, for programming and data quality check. Medical editorial assistance for this manuscript was provided by Tamalette Loh, PhD, at ProEd Communications, Inc., Beachwood, Ohio.

Role of the funding source

GlaxoSmithKline Pharmaceuticals, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA, supported this study and provided funding for medical editorial assistance for the manuscript preparation. The academic authors (and coauthors Chen, Norry, Compton, Heise, Carpenter and Pandite who are employed by GlaxoSmithKline) participated in study design, data collection/analysis/interpretation and writing of the manuscript. Final decisions regarding the content of the manuscript and the decision to submit the manuscript for publication were made by the corresponding author in consultation with all coauthors.

Conflict of interest statement

Powles reports consulting/advisory roles with GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer, and Novartis; speakers’ bureau for GlaxoSmithKline; research funding from GlaxoSmithKline and Pfizer. Bracarda reports consulting/advisory roles for Aveo-Astellas, Bayer, Boehringer-Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer, and Sanofi-Aventis; honoraria from Janssen, Sanofi-Aventis, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, and Pfizer. Hutson reports honoraria from Pfizer, GlaxoSmithKline, Bayer, BioLon, Novartis, Astellas, Janssen, and Dendreon; consulting/advisory roles with Pfizer, GlaxoSmithKline, Bayer, Novartis, Janssen, and Astellas; speakers’ bureau for Pfizer, Bayer, GlaxoSmithKline, Astellas, Janssen, and Dendreon; research funding from Pfizer, Bayer, Jansen, Astellas, and GlaxoSmithKline. Kaplowitz reports consulting/ advisory roles with Five Prime Therapeutics, Biogen Idec, GlaxoSmithKline, Johnson & Johnson, Merck Sharp & Dohme Research Laboratories, ONO Pharma USA, Novo Nordisk, Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization, Geron Corporation, Pfizer, and Takeda Pharmaceuticals North America. Harter reports no potential conflicts of interest. Chen, Norry, Compton, Heise, Carpenter, and Pandite are GlaxoSmithKline employees and stockholders.

Footnotes

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2015.03.019.

References

- [1].GlaxoSmithKline. Votrient (pazopanib) tablets prescribing information. GlaxoSmithKline: Research Triangle Park, NC: Revised June 2014. Available at: <http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2012/022465s-010S-012lbl.pdf>; [accessed 27.10.14]. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Shah RR, Morganroth J, Shah DR. Hepatotoxicity of tyrosine kinase inhibitors: clinical and regulatory perspectives. Drug Saf 2013;36(7):491–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Petrucci D, Hu C, French K, Webster L, Skordos K, Brown R, et al. Preclinical investigations into potential mechanisms of pazopanib–induced hepatotoxicity in patients. Toxicol Sci 2012;126(Suppl. 1). Abstract 2262. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Klempner SJ, Choueiri TK, Yee E, Doyle LA, Schuppan D, Atkins MB. Severe pazopanib-induced hepatotoxicity: clinical and histologic course in two patients. J Clin Oncol 2012;30(27):e264–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Spraggs CF, Budde LR, Briley LP, Bing N, Cox CJ, King KS, et al. HLA-DQA1*02:01 is a major risk factor for lapatinibinduced hepatotoxicity in women with advanced breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2011;29(6):667–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Hutson TE, Davis ID, Machiels JP, De Souza PL, Rottey S, Hong BF, et al. Efficacy and safety of pazopanib in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2010;28(3):475–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, Cella D, Reeves J, Hawkins R, Guo J, et al. Pazopanib versus sunitinib in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2013;369(8):722–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Sternberg CN, Davis ID, Mardiak J, Szczylik C, Lee E, Wagstaff J, et al. Pazopanib in locally advanced or metastatic renal cell carcinoma: results of a randomized phase III trial. J Clin Oncol 2010;28(6):1061–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Motzer RJ, Johnson T, Choueiri TK, Deen KC, Xue Z, Pandite LN, et al. Hyperbilirubinemia in pazopanib- or sunitinib-treated patients in COMPARZ is associated with UGT1A1 polymorphisms. Ann Oncol 2013;24(11):2927–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Xu CF, Reck BH, Xue Z, Huang L, Baker KL, Chen M, et al. Pazopanib-induced hyperbilirubinemia is associated with Gilbert’s syndrome UGT1A1 polymorphism. Br J Cancer 2010;102(9):1371–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Aithal GP, Watkins PB, Andrade RJ, Larrey D, Molokhia M, Takikawa H, et al. Case definition and phenotype standardization in drug-induced liver injury. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2011;89(6):806–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Andrade RJ, Lucena MI, Fernandez MC, Pelaez G, Pachkoria K, Garcia-Ruiz E, et al. Drug-induced liver injury: an analysis of 461 incidences submitted to the Spanish registry over a 10-year period. Gastroenterology 2005;129(2):512–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Zimmerman HJ. Hepatotoxicity: the adverse effects of drugs and other chemicals on the liver. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Sleijfer S, Ray-Coquard I, Papai Z, Le Cesne A, Scurr M, Schoffski P, et al. Pazopanib, a multikinase angiogenesis inhibitor, in patients with relapsed or refractory advanced soft tissue sarcoma: a phase II study from the European organisation for research and treatment of cancer-soft tissue and bone sarcoma group (EORTC study 62043). J Clin Oncol 2009;27(19):3126–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].van der Graaf WT, Blay JY, Chawla SP, Kim DW, Bui-Nguyen B, Casali PG, et al. Pazopanib for metastatic soft-tissue sarcoma (PALETTE): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet 2012;379(9829):1879–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].du Bois A, Floquet A, Kim J-W, Rau J, del Campo JM, Friedlander M, et al. Incorporation of pazopanib in maintenance therapy of ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol 2014;32(30):3374–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Food US and Administration Drug. Guidance for Industry. Drug-Induced Liver Injury: Premarketing Clinical Evaluation. July 2009. Available at: <http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM174090.pdf>; [accessed 29.10.14]. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Green RM, Flamm S. AGA technical review on the evaluation of liver chemistry tests. Gastroenterology 2002;123(4):1367–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Danan G, Benichou C. Causality assessment of adverse reactions to drugs–I. A novel method based on the conclusions of international consensus meetings: application to drug-induced liver injuries. J Clin Epidemiol 1993;46(11):1323–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Fontana RJ, Seeff LB, Andrade RJ, Bjornsson E, Day CP, Serrano J, et al. Standardization of nomenclature and causality assessment in drug-induced liver injury: summary of a clinical research workshop. Hepatology 2010;52(2):730–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Fontana RJ, Watkins PB, Bonkovsky HL, Chalasani N, Davern T, Serrano J, et al. Drug-induced liver injury network (DILIN) prospective study: rationale, design and conduct. Drug Saf 2009;32(1):55–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Kaplowitz N, DeLeve LD. Drug-induced liver disease. 3rd ed. Waltham, MA: Academic Press (Elsevier); 2013. p. 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Rini BI, Cohen DP, Lu DR, Chen I, Hariharan S, Gore ME, et al. Hypertension as a biomarker of efficacy in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with sunitinib. J Natl Cancer Inst 2011;103(9):763–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Wang X, Xue Z, Carpenter C, Harter P, King K, Stinnett S, et al. Genome-wide association study (GWAS) for transaminase elevations in pazopanib-treated patients. Poster (abstract 3479S) presented at: ASHG 2014 Annual Meeting; October 18–22, 2014; San Diego, CA. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.