Abstract

Background

Dry eye syndrome is the most common complication of refractive surgery. Acupuncture is widely used for the treatment of ophthalmologic diseases, but to date, few have explored the effects of acupuncture for the treatment of this condition following refractive surgery. The objective of this study is to assess the feasibility of a study design for evaluating the effectiveness of acupuncture treatment along with usual care compared with usual care only for dry eye syndrome after refractive surgery.

Methods

A total of 18 patients with dry eye syndrome occurring after refractive surgery participated in this study. For 4 weeks, the acupuncture plus usual care and usual care only groups received treatment three times a week. A series of assessments, namely the ocular surface disease index (OSDI), visual analog scale for ocular discomfort, quality of life, tear film break-up time, Schirmer 1 test, and fluorescein-stained corneal-surface photography, along with other general assessments were carried out.

Results

Although preliminary, changes in OSDI from the baseline values were significantly different between the two groups at week 5 (p = 0.0003). There was a significant difference in the trends of OSDI changes between the acupuncture plus usual care and the usual care only groups (p = 0.0039). No serious adverse events were reported during the study.

Conclusion

Four weeks of acupuncture treatment in addition to usual care is a feasible treatment for dry eye syndrome after refractive surgery. A full-scale randomized controlled trial is needed to confirm the clinical effectiveness of acupuncture.

Keywords: Acupuncture, Dry eye syndromes, Refractive surgery, Clinical trial, Pilot study

1. Introduction

Refractive surgery using the excimer laser to correct myopia has been widely used for decades.1, 2, 3 Dry eye is one of the most common risks and complications after refractive surgery. During refractive surgery, the corneal nerves are damaged, contributing to a loss of corneal sensation.4, 5 This decrease in sensitivity can result in reduced tear secretion, a decrease in the number of conjunctival goblet cells, leading to a reduction in eye moisture.6 Patients who already had dry eye symptoms before LASIK are at a greater risk of postoperative dry eye syndrome.7 Approximately 10–20% of post-LASIK patients suffer from chronic dry eye symptoms with severe discomfort. A 12-year follow-up reported that 3% had dry eye after refractive surgery.8

Widely used treatments for dry eye syndrome include artificial tears and lifestyle modifications.5 Punctal occlusion is an alternate method to treat some chronic dry eye syndromes,9, 10 but its convenience and safety are currently unclear. Since dry eye syndrome is a multifactorial disease and is often associated with various psychological or neurological conditions, its treatment requires an approach from various perspectives.11

Acupuncture is widely used for the treatment of ophthalmologic diseases,12 and previous research on dry eye syndrome has shown that it can stimulate the autonomic nervous and immune systems, thereby increasing lacrimal secretion by stimulating the lacrimal gland function.13, 14 Many studies have demonstrated the validity, safety, and efficacy of acupuncture for treating dry eye syndrome,15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20 but to date, few have explored the effects of acupuncture for the treatment of this condition following refractive surgery.

With this pilot study, we attempt to evaluate the feasibility of acupuncture for the relief of chronic dry eye syndrome following refractive surgery.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Study design

To determine the supplementary effect of acupuncture to the usual treatment, a prospective, randomized, active-controlled, parallel-group designed trial was performed, as has been previously published,15 and it was registered with the Clinical Research Information Service (CRIS) at the Korean National Institute of Health (identifier: KCT0000727) before participant enrollment. This trial was conducted in a clinical research center at the Korean Medicine Hospital at Daejeon University, South Korea, from November 2012 to December 2013. The protocol was approved prior to study commencement by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the Korean Medicine Hospital at Daejeon University. Participants were recruited through advertisements in the university homepage, a local newspaper, distributed leaflets and posts on notice boards. Written informed consent was obtained from all of the participants prior to the study. The study protocol was previously published in a peer-reviewed journal.15

2.2. Study participants

Because this is an exploratory pilot study to evaluate the feasibility, sample size was not calculated according to the conventional power analysis method. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (a) adults aged 18 to 65 years; (b) patients who had symptoms of dry eye syndrome in one or both eye(s) following refractive surgery within the previous 24 months; (c) participants who met the diagnostic criteria of dry eye syndrome, which were a visual analog scale (VAS) score ≥40, tear film break-up time (TFBUT) ≤10 s and Schirmer-1 test ≤10 mm/5 min; and (d) were willing to join the study and provided written informed consent.

Patients were excluded if they had (a) dry eye symptoms due to eyelid or eyelash defects; (b) acute infection of the eyelid, eyeball, or periorbital area; (c) skin diseases such as Stevens-Johnson syndrome and/or pemphigoid; (d) vitamin A deficiency; (e) any external injury to the orbital or periorbital area; (f) a history of eye surgery within the previous six months (except refractive surgery); (g) impaired blinking due to facial palsy; (h) a history of punctal plug or punctal occlusion surgery; (i) lactation, pregnancy, or plans to conceive; and/or (j) were excluded at the investigator's discretion.

2.3. Randomization & allocation concealment methods

Participants were randomly assigned to either the acupuncture plus usual care group (acupuncture group) or the control group (usual care group) with a 1:1 ratio. Random numbers were generated through computerized block-randomization with the SAS package (SAS® Version 9.1, SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC) by an independent statistician. Opaque assignment envelopes with consecutive numbers indicating which treatment the subjects were assigned to were used for allocation concealment. To prevent researchers from influencing the outcome measures, the random sequence generator, practitioners, and assessors were supervised by different researchers. Thus, the researcher evaluating the outcome measures was blinded to the participants’ treatment allocations.

2.4. Interventions

The participants were randomly allocated to the usual care group (n = 9) or the acupuncture group (n = 9). Both groups maintained usual care, but the treatment group had acupuncture treatment added for us to evaluate its supplementary effect. All patients were permitted to use any supportive care for dry eye symptoms, such as artificial tear drops, drugs and supplements other than surgical treatments, such as punctual occlusion surgery or punctual plugs.

The acupuncture group (n = 9) received acupuncture treatment along with the usual treatment. Acupuncture treatment was performed three times per week (a total of 12 treatments). Each session of treatment included the use of 17 acupuncture points (bilateral BL2, TE23, GB14, GB20, Ex1, ST1, LI4, and LI11 and single GV23). A group of experts working on ophthalmologic practice of traditional Korean medicine or acupuncture research decided on acupuncture points based on textbooks and published references20, 21, 22. Korean medicine experts performed the treatments using 0.20 mm × 30 mm acupuncture needles (Dongbang Acupuncture Inc., Chungnam, Republic of Korea). The ‘de-qi’ sensation was induced by twisting acupuncture and the needles were retained for 20 min.

2.5. Outcome measures

Outcome measures based on questionnaires were assessed at week 1 (baseline), week 3, week 5 and week 13 by separate outcome assessors who did not provide acupuncture treatment. The primary outcome was the Ocular Surface Disease Index (OSDI) change. OSDI is a validated questionnaire for evaluating the character and severity of the dry eye symptoms.23 The OSDI scores ranged from 0 to 100: the higher the score, the more severe the dry eye symptoms.

The secondary outcomes included ocular discomfort on the 100 mm Visual Analog Scale (VAS) and the Measure Yourself Medical Outcome Profile-2 (MYMOP-2) QOL questionnaire. For the self-reported symptom of ocular discomfort, each patient marked the level of symptoms related to dry eye (e.g. foreign body sensation, ocular itching, burning, pain and dryness, blurred vision, the sensation of photophobia, ocular redness, and the sensation of tearing) on the standard 100 mm VAS scale. The QOL section of MYMOP-2 was adopted for assessing the effects of dry eye on the patients’ QOL. The subjects rated their overall quality of life related to dry eyes on a 7-point Likert scale (from zero as ‘excellent’ to six as ‘worst’).15

The overall assessment of dry eye syndrome-related symptoms was conducted by both practitioners and participants after the treatment period (week 5). Both practitioners and participants graded the symptoms as excellent, good, fair, no change, or aggravated.

Ophthalmological examinations such as TFBUT, the Schirmer 1 test, and fluorescein-stained corneal-surface photography (CSP) were evaluated by ophthalmologists at the screening visit and at the end of the study (week 13). The TFBUT test assesses tear film stability by measuring interval between an eye blink and the first appearance of a dry spot in the treat film after instilling sodium fluorescein into the lower fornix. A TFBUT below 10 s suggests dry eyes of at least moderate severity. The Schirmer 1 test was used to measure the basic quantity of tear secretion. A Schirmer test strip (Color Bar, Eagle Vision, USA) was placed over the lateral third of the lower eyelids for 5 min with closed eyes, after which the length of the wet portion was measured. Scores below 10 mm/5 min suggests dry eyes of at least moderate severity. Fluorescein-stained CSP was used to evaluate the corneal surface damage in dry eyes.15 The results were graded according to the Oxford scheme: from 0 (absent) to 5 (severe).16

To evaluate the treatment safety, we monitored adverse events whether related to acupuncture or not. To prevent bias, an expert panel of individuals not connected to the study evaluated the reports of adverse events.

2.6. The statistical analyses

All values are presented as the mean and 95% confidence interval (95% CI). SAS software was used for all of the statistical analyses. The significance level was set at 0.05. Missing values were imputed according to the last-observation-carried-forward method. The baseline data from the acupuncture treatment and usual care groups were compared using independent-sample t-tests. Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used to explore between-group differences in outcome measures (dependent variables: OSDI, TFBUT, Schirmer 1 test, QOL, and ocular discomfort on VAS) while also controlling for the potential effects of other variables (covariates and baseline scores). Repeated measures were used to explore the between-visit differences in the outcome measures. The Chi-squared test or Fisher's exact test was used to explore the between-group differences in the fluorescein-stained CSF. Correlation analysis was used to evaluate the relationships between the patients’ expectations of acupuncture treatment and the relief of dry eye symptoms in the acupuncture group.

3. Results

3.1. The baseline characteristics

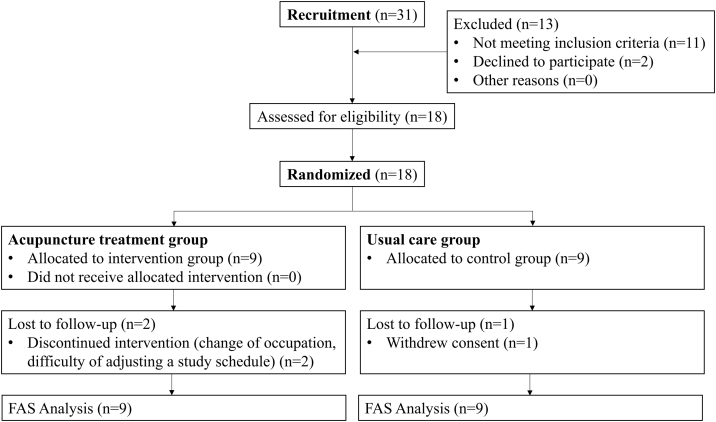

A flow diagram of the overall study is provided in Fig. 1. Among 31 volunteers, 18 participants were identified as eligible for the study. A total of 15 participants completed the study, 2 subjects from the acupuncture group and one subject from the usual care group dropped-out. The demographic data and baseline values for the main outcome variables are given in Table 1, in which no significant between-group differences were observed in the baseline characteristics or outcome measure values.

Fig. 1.

The flow diagram according to the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) statement.

Table 1.

The Baseline Characteristics of the Participants

| Characteristics | Acupuncture group (n = 9) | Usual care group (n = 9) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | 23.67 (20.06, 27.27) | 24.67 (19.98, 29.36) | 0.7019† |

| Sex (M/F) | 3 (33.3%)/6 (66.7%) | 1 (11.1%)/8 (88.9%) | 0.5765‡ |

| Duration of symptoms (month) | 6.33 (2.63, 10.04) | 8.78 (3.71, 13.84) | 0.3825† |

| Computer or TV use (hour/week) | 22.11 (8.58, 35.64) | 24.39 (9.07, 39.71) | 0.8005† |

| Smoking/Non-smoking | 2 (22.2%)/7 (77.8%) | 0 (0.0%)/9 (100.0%) | 0.4706‡ |

| Previous treatment (frequency) | |||

| Artificial tears use | 9 (100.0%) | 9 (100.0%) | 0.9999‡ |

| Other treatment use | 5 (55.6%) | 4 (44.4%) | 0.9999‡ |

| No-treatment | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.9999‡ |

| Past history related to dry eye (frequency) | |||

| Conjunctivitis | 1 (11.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.9999‡ |

| Usage frequency of the usual care items (within the last month) | |||

| Artificial tears use | 4 (44.4%) | 6 (66.7%) | 0.6372‡ |

| Other treatment use | 1 (11.1%) | 4 (44.4%) | 0.1312‡ |

| No-treatment | 4 (44.4%) | 1 (11.1%) | 0.2941‡ |

Data shown in mean (95% Confidence Interval or percentage).

Independent sample t-test.

Fisher's exact test.

To evaluate the supplementary effect of acupuncture along with the usual care, we did not strictly limit the type of usual treatment. However, all of the subjects’ choice of treatment was the use of artificial tears or nothing. Among all the subjects in each group, only 5 of them maintained their use of artificial tears, while 8 maintained their use of artificial tears in the usual care group.

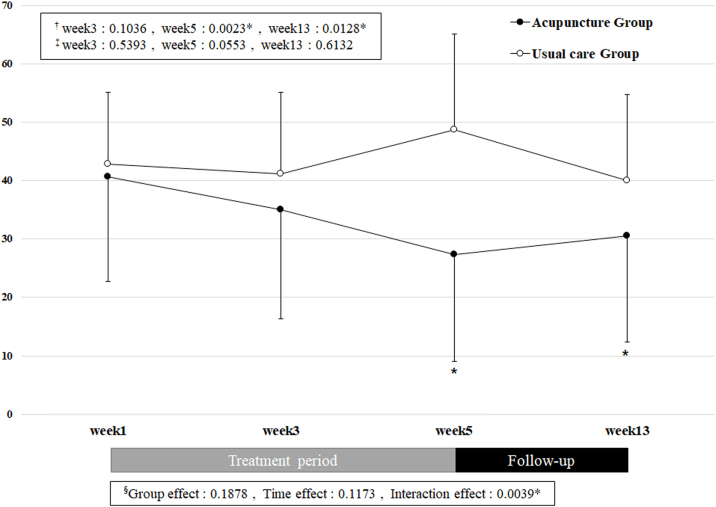

3.2. The primary outcome

In the trends of OSDI changes, significant between-group differences were observed (p = 0.0039, RM ANOVA; Supplementary Figure 1). In the acupuncture group, the OSDI score showed a decreasing tendency during the treatment period, while those in the usual care group rather increased. After 4 weeks of the acupuncture treatment, there was a significant difference between the treatment and the usual care groups (p = 0.0003, ANCOVA; Table 2). The adjusted difference in OSDI revealed a significant reduction at week 5 in the acupuncture group [19.24 (95% CI: 10.38–28.10)] compared to the usual care group.

Table 2.

Changes in Ocular Symptoms and Quality of Life.

| Acupuncture group (95% CI) | Usual care group (95% CI) | Adjusted differencea (95% CI) | Partial eta-square (η2) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OSDI | ||||

| Baseline (week 0) | 40.65 (31.20, 50.11) | 42.82 (29.10, 56.55) | ||

| Intervention (week 3) | 35.12 (24.35, 45.89) | 41.23 (26.78, 55.68) | −4.08 (−12.64, 4.49) | 0.06 |

| Intervention (week 5) | 27.38 (14.77, 39.98) | 48.76 (34.66, 62.85) | −19.24 (−28.10, −10.38)* | 0.58 |

| Follow-up (week 13) | 30.60 (19.18, 42.01) | 40.00 (26.01, 53.99) | −7.85 (−20.82, 5.11) | 0.10 |

| Ocular discomfort on VAS | ||||

| Baseline (week 0) | 67.67 (59.40, 75.94) | 62.67 (48.72, 76.61) | ||

| Intervention (week 3) | 58.67 (42.81, 74.53) | 53.00 (34.71, 71.29) | 0.59 (−16.63, 17.82) | 0.00 |

| Intervention (week 5) | 46.89 (28.25, 65.53) | 60.00 (39.90, 80.10) | −16.76 (−40.74, 7.23) | 0.13 |

| Follow-up (week 13) | 53.67 (38.18, 69.15) | 50.33 (34.80, 65.87) | −1.41 (−16.57, 13.74) | 0.00 |

| Quality of life | ||||

| Baseline (week 0) | 3.67 (3.00, 4.33) | 3.56 (2.53, 4.58) | ||

| Intervention (week 3) | 3.11 (2.51, 3.71) | 3.33 (2.32, 4.35) | −0.26 (−1.30, 0.77) | 0.02 |

| Intervention (week 5) | 2.67 (1.81, 3.53) | 3.78 (2.78, 4.78) | −1.15 (−2.34, 0.04) | 0.22 |

| Follow-up (week 13) | 3.00 (2.23, 3.77) | 3.33 (2.39, 4.27) | −0.36 (−1.49, 0.78) | 0.03 |

Analysis of Covariance (ANCOVA) was used for the statistical analysis of the OSDI, ocular discomfort, and QOL between-group changes from the baseline. All outcomes were adjusted for the baseline values. Negative values of the adjusted differences in OSDI, ocular discomfort, and QOL favor the acupuncture group; * p-value = 0.0003; CI, Confidence Interval; OSDI, Ocular Surface Disease Index; VAS, Visual Analog; QOL, Quality of Life

3.3. The secondary outcomes

The secondary outcomes: self-assessment score of ocular discomfort and the MYMOP-2 QOL questionnaire showed similar trends to OSDI. However, after using a regression model to adjust for differences, the between-group differences for the ocular symptom-related questionnaires were not significant at weeks 5 and 13 (Table 2). The results from the ophthalmologic tests also showed no significant differences between the groups (Table 3).

Table 3.

Changes in the Ophthalmologic Tests After 4 Weeks of Intervention and 8 Weeks Follow-up

| Acupuncture group (95% CI) | Usual care group (95% CI) | Adjusted differencea 95% CI) | Partial eta-square (η2) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TFBUT | |||||

| Left | Baseline (week 0) | 5.11 (3.46, 6.76) | 6.11 (4.70, 7.52) | ||

| Follow-up (week 13) | 6.44 (4.64, 8.25) | 6.56 (5.11, 8.00) | 0.70 (−0.77, 2.18) | 0.06 | |

| Right | Baseline (week 0) | 5.44 (4.05, 6.84) | 6.89 (5.48, 8.30) | ||

| Follow-up (week 13) | 7.00 (4.57, 9.43) | 7.11 (5.10, 9.12) | 1.41 (−1.03, 3.86) | 0.09 | |

| CSP | |||||

| Left | Baseline (week 0) | 1.78 (1.14, 2.42) | 1.33 (0.67, 2.00) | ||

| Follow-up (week 13) | 1.33 (0.67, 2.00) | 1.22 (0.58, 1.86) | −0.24 (−0.81, 0.34) | 0.05 | |

| Right | Baseline (week 0) | 1.67 (0.90, 2.44) | 1.33 (0.67, 2.00) | ||

| Follow-up (week 13) | 1.33 (0.67, 2.00) | 1.11 (0.51, 1.71) | −0.01 (−0.55, 0.53) | 0 | |

| Schirmer 1 test | |||||

| Left | Baseline (week 0) | 5.22 (2.86, 7.58) | 7.00 (4.26, 9.74) | ||

| Follow-up (week 13) | 5.44 (2.89, 8.00) | 6.33 (3.76, 8.91) | −0.54 (−4.07, 2.99) | 0.01 | |

| Right | Baseline (week 0) | 6.67 (3.00, 10.33) | 6.56 (4.88, 8.24) | ||

| Follow-up (week 13) | 4.78 (2.48, 7.08) | 6.44 (3.42, 9.47) | −1.73 (−4.61, 1.15) | 0.1 | |

Analysis of Covariance (ANCOVA) was used for the statistical analysis of the TFBUT, CSP, and Schirmer 1 test between-group changes from baseline. All outcomes were adjusted for baseline values. Negative values of the adjusted differences CSP and Schirmer values (positive difference in TFBUT) favor the acupuncture group. CI, Confidence Interval; TFBUT, Tear film break-up time; CSP, Corneal surface photography

3.4. The overall assessment results

Of the 7 patients in total in the acupuncture treatment group, 4 showed an improvement in their general outcomes, while 1 exhibited a poor one. However, no participant showed any aggravation of the symptoms. In the usual care group, 1 patient showed improved general outcomes, while 3 still maintained a poor general outcome. However, no significant differences between the groups were found using the Chi-squared test.

3.5. Adverse events

Three patients from the acupuncture group and 4 from the usual care group reported adverse events. Two patients from the acupuncture group experienced mild symptoms of upper respiratory tract infection and 1 patient had stomatitis after a 3rd molar extraction. However, all 3 cases were irrelevant to the acupuncture treatment. In the usual care group, 2 patients experienced upper respiratory tract infection, 1 reported vasculitis, and 1 experienced conjunctivitis.

4. Discussion

The current pilot study met our key objective to provide valuable information for the design of a full-scale trial to explore the effectiveness of acupuncture with usual care compared to usual care only for the treatment of dry eye syndrome after refractive surgery. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first pilot study for evaluating acupuncture plus usual care for the treatment of dry eye syndrome after refractive surgery. After 4 weeks of acupuncture treatment, our results show that acupuncture treatment along with usual care presented superior results compared to the usual care only group with regard to the OSDI score. However, the improvement did not last during the 8-week follow-up period. Although the results did not show statistically significant differences between the groups, the self-assessment of ocular discomfort and the QOL showed similar trends to OSDI. The study had 83.3% of adherence rate and completion rate.

There have been many clinical trials to evaluate acupuncture for the treatment of dry eye symptoms. However, none of the previous studies have classified dry eye syndrome according to the onset of dry eye and performed subgroup analysis. A meta-analysis study concluded that acupuncture is more effective than artificial tears for dry eye syndrome from the analysis of 7 clinical trials,19 although another systematic review on acupuncture for treating dry eye failed to draw conclusions because of limited evidence.20 A multicenter study comparing acupuncture with artificial teardrops in 150 patients reported that although 4 weeks of acupuncture treatment did not significantly benefit the symptoms of dry eye syndrome, acupuncture group showed that improvement of OSDI sustained until 8 weeks of follow-up period compared to the control group, indicating that acupuncture might have a long-term effect on treating dry eye syndrome.18 On the contrary, our study results showed significant improvement after the treatment period and the treatment effect did not persist for the 8-week observation period. Our previous clinical study for dry eye syndrome showed that there was no significant differences between acupuncture group and placebo acupuncture group as both groups had significantly improved OSDI scores.17 This is in line with current study that 4-week acupuncture treatment can significantly reduce OSDI scores but there was no significant difference in objective measures such as TFBUT, Schirmer and CSP. As our result showed that acupuncture treatment along with usual care may have a short-term treatment effect, the future study will require additional ophthalmic examination immediately after the treatment.

The mechanism of acupuncture treatment of dry eye has not been fully explained but many researchers believe that acupuncture has a curative effect on dry eye, and it is thought that acupuncture acts to reduce inflammation through the modulation of vagus nerve activity,24 resulting in increased immune protein synthesis and secretion from the lacrimal glands.25 Therefore, inflammation markers or clinical parameters related to autonomic nervous system should be assessed in the further studies.

This study had some weaknesses. Because it was impossible to maintain the acupuncture practitioners’ and participants’ blinding in the study design, the results might have been overestimated. However, we incorporated assessor blinding, which is likely to have been more important. Additional clinical trials should be conducted to include other types of control interventions, such as non-penetrating sham needles and conventional treatments such as artificial tear drops. In addition, outcome measures to explore the detailed physiological mechanisms, cost-effectiveness, and qualitative characteristics should also be evaluated to enhance our understanding of the benefits of acupuncture treatment for dry eye syndrome after refractive surgery.

In conclusion, the results from this study have shown that it is feasible to recruit subjects to receive acupuncture plus usual care and usual care only for the treatment of dry eye syndrome after refractive surgery, and the tentative findings support conducting a subsequent full-scale trial. The pilot data have enabled the estimation of the sample size required for a full-scale trial, as well as the expected recruitment rates. Future research is needed to determine the physiological effect of acupuncture on dry eye syndrome after refractive surgery.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: JHL and KH. Methodology: JHL and THK. Formal Analysis: KH, THK, and OK. Investigation: JHK, JEK, SL, MSS, SYJ and HJP. Writing Original Draft: JHL, KH and THK. Writing - Review & Editing: JHL, KH, THK, ARK, OK, JHK, JEK, SL, MSS, SYJ, HJP, and SL. Supervision: Sanghun Lee.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Funding

This work was supported by a Public Healthcare System for Citizens through Traditional Korean Medicine provided by Daejeon Technopark in 2012 (G12050) and Korean Institute of Oriental Medicine (K18121). As a government-funded research institute, Korean Institute of Oriental Medicine is responsible for the study design, data collection, analysis, data interpretation, and presentation of the result.

Ethical statement

This research has been approved by Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the Korean Medicine Hospital at Daejeon University.

Data availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.imr.2020.100456.

Supplementary material

The following are the supplementary material to this article:

Supplementary Figure 1.

Changes in ocular surface disease index (OSDI) score. † = repeated measures analysis of variance (RM ANOVA) for the acupuncture plus usual care; ‡ = repeated measures analysis of variance (RM ANOVA) for the usual care group; * = p-value <0.05; a the interaction effect between the acupuncture plus usual care and usual care only groups; and bp-value = 0.0002 in the post hoc testing at week 5.

References

- 1.Guerin M., O’Keeffe M. Informed consent in refractive eye surgery: learning from patients and the courts. Irish Med J. 2012;105:282–283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nettune G.R., Pflugfelder S.C. Post-LASIK tear dysfunction and dysesthesia. Ocular Surf. 2010;8:135–145. doi: 10.1016/s1542-0124(12)70224-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khan-Lim D., Craig J.P., McGhee C.N. Defining the content of patient questionnaires: reasons for seeking laser in situ keratomileusis for myopia. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2002;28:788–794. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(02)01234-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li X.M., Hu L., Hu J., Wang W. Investigation of dry eye disease and analysis of the pathogenic factors in patients after cataract surgery. Cornea. 2007;26(Suppl. 1):S16–S20. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e31812f67ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yu E.Y., Leung A., Rao S., Lam D.S. Effect of laser in situ keratomileusis on tear stability. Ophthalmology. 2000;107:2131–2135. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(00)00388-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Albietz J.M., Lenton L.M., McLennan S.G. Dry eye after LASIK: comparison of outcomes for Asian and Caucasian eyes. Clin Exp Optom. 2005;88:89–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1444-0938.2005.tb06673.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chao C., Golebiowski B., Stapleton F. The role of corneal innervation in LASIK-induced neuropathic dry eye. Ocular Surf. 2014;12:32–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2013.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rajan M.S., Jaycock P., O’Brart D., Nystrom H.H., Marshall J. A long-term study of photorefractive keratectomy; 12-year follow-up. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:1813–1824. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ervin A.M., Law A., Pucker A.D. Punctal occlusion for dry eye syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;6:Cd006775. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006775.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alfawaz A.M., Algehedan S., Jastaneiah S.S., Al-Mansouri S., Mousa A., Al-Assiri A. Efficacy of punctal occlusion in management of dry eyes after laser in situ keratomileusis for myopia. Curr Eye Res. 2014;39:257–262. doi: 10.3109/02713683.2013.841258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Han S.B., Yang H.K., Hyon J.Y., Wee W.R. Association of dry eye disease with psychiatric or neurological disorders in elderly patients. Clin Interv Aging. 2017;12:785–792. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S137580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gong L., Sun X., Chapin W.J. Clinical curative effect of acupuncture therapy on xerophthalmia. Am J Chin Med. 2010;38:651–659. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X10008123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Backer M., Grossman P., Schneider J., Michalsen A., Knoblauch N., Tan L. Acupuncture in migraine: investigation of autonomic effects. Clin J Pain. 2008;24:106–115. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e318159f95e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kavoussi B., Ross B.E. The neuroimmune basis of anti-inflammatory acupuncture. Integr Cancer Ther. 2007;6:251–257. doi: 10.1177/1534735407305892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jang H., Lee S., Kim T.H., Kim A.R., Lee M., Lee J.H. Acupuncture for dry eye syndrome after refractive surgery: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2013;14:351. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-14-351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bron A.J., Evans V.E., Smith J.A. Grading of corneal and conjunctival staining in the context of other dry eye tests. Cornea. 2003;22:640–650. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200310000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shin M.S., Kim J.I., Lee M.S., Kim K.H., Choi J.Y., Kang K.W. Acupuncture for treating dry eye: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Acta Ophthalmol. 2010;88:e328–e333. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.2010.02027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim T.H., Kang J.W., Kim K.H., Kang K.W., Shin M.S., Jung S.Y. Acupuncture for dry eye: a multicentre randomised controlled trial with active comparison intervention (artificial tear drop) using a mixed method approach protocol. Trials. 2010;11:107. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-11-107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang L., Yang Z., Yu H., Song H. Acupuncture therapy is more effective than artificial tears for dry eye syndrome: evidence based on a meta-analysis. Evid-based Complement Altern Med: eCAM. 2015;2015:143858. doi: 10.1155/2015/143858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee M.S., Shin B.C., Choi T.Y., Ernst E. Acupuncture for treating dry eye: a systematic review. Acta Ophthalmol. 2011;89:101–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.2009.01855.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim T.H., Kang J.W., Kim K.H., Kang K.W., Shin M.S., Jung S.Y. Acupuncture for the treatment of dry eye: a multicenter randomised controlled trial with active comparison intervention (artificial teardrops) PLOS ONE. 2012;7:e36638. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kwon D.-H., Kim Y.-S., Choi D.-Y. Book research into acupuncture treatment for dry eye. J Acupunct Res. 2000;17:10–24. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schiffman R.M., Christianson M.D., Jacobsen G., Hirsch J.D., Reis B.L. Reliability and validity of the ocular surface disease index. Arch Ophthalmol. 2000;118:615–621. doi: 10.1001/archopht.118.5.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oke S.L., Tracey K.J. The inflammatory reflex and the role of complementary and alternative medical therapies. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1172:172–180. doi: 10.1196/annals.1393.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu Q., Liu J., Ren C., Cai W., Wei Q., Song Y. Proteomic analysis of tears following acupuncture treatment for menopausal dry eye disease by two-dimensional nano-liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry. Int J Nanomed. 2017;12:1663–1671. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S126968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.