Abstract

Background

Restoration of spinopelvic balance during spinal surgery is very important to ensure a good outcome. Many studies have been conducted to define the normal ranges, examining the correlation between these individual parameters and their relation with spinal parameters of thoracic kyphosis and lumbar lordosis. The ranges, specific to individual ethnicities, is very essential to restore the sagittal balance in patients suffering from spinal degenerative conditions. Hence this study aims to define the average ranges of relevant spinopelvic parameters in the adult population of Indian origin.

Methods

A observational cross sectional study was conducted in 130 healthy volunteers in Mumbai without having any spine, hip or pelvis pathology. Spinopelvic parameters like Pelvic Incidence(PI), Sacral Slope(SS) and Pelvic Tilt(PT) were studied and compared between various other similar studies with patients of different ethnicities. The correlation of those parameters with each other was also evaluated.

Results

The mean value of PI was 51.50(±6.85°), that of SS was 39.17° (±6.26°) and for PT it was 12.32°(±5.41°). These values were statistically significant between both sexes for PI and PT. The strongest positive correlation among the parameters was between pelvic incidence and sacral slope, with a r-value of 0.668. Comparison of our study with similar studies within the country (Chennai, Delhi and Surat) showed statistically significant differences in PT and SS of all three studies while PI was not significant when compared with the Surat study.

Conclusion

There appears to be considerable variation of the values of the spinopelvic parameters as determined by various studies due to ethnic variations. Further studies should be done with larger samples and directed towards early detection of individuals at risk of developing degenerative spinal disorders with sagittal imbalance, so that interventions can be made at an earlier stage.

Keywords: Spinopelvic parameters, Pelvic incidence, Sacral slope, Pelvic tilt, Indian

1. Introduction

The importance of spinopelvic parameters in the pathogenesis of spinal degenerative disorders is well known.1 Restoration of spinopelvic balance during spinal surgery is very important to ensure a good outcome. The key spinopelvic parameters, namely, Pelvic incidence, Sacral slope and Pelvic tilt, first proposed by Legaye, Duval-Beaupère et al.2 have been accepted as the principle measures representing the state of spinopelvic sagittal balance. it is now recognized that spinopelvic alignment is important to maintain an energy-efficient posture in normal and disease states. The pelvic incidence, with sacral slope and pelvic tilt, determines the conditions of the principle of biomechanical economy.

Spino-pelvic balance in the sagittal plane can be considered as an open linear chain linking the head to the pelvis where the shape and orientation of each successive anatomic segment are closely related and influence the adjacent segment. Many studies have been conducted examining the correlation between these individual parameters and their relation with spinal parameters of thoracic kyphosis and lumbar lordosis.2,3 A number of studies defining the normal ranges of these parameters have also been conducted, but these have usually been done in white populations. In 2012, Baron Zarate-Kalfopulos4 did a study to compare values of the spinopelvic parameters found in Mexican population with values of the same parameters found in previous studies done in Caucasian and Asian populations. He found statistically significant differences between the populations of different ethnicities. Very few studies, however have been done to calculate the baseline in asymptomatic Indian adults. These studies have shown differences in the values of these parameters in different ethnic groups within the Indian population. These differences can be attributed to the anthropometric differences among the different ethnicities.

The aim of our study was to define the normal ranges of the spinopelvic parameters in healthy Indian adults and to see if they differ from values of these parameters in other ethnicities. If they do differ, is this difference statistically significant? We also studied whether these values were significantly different within male and female sex in our study population.

2. Materials and methods

Our study was conducted in a tertiary care center in Mumbai, with a sample size of 130 volunteers. Volunteers were enlisted for the study over a period of one year after obtaining approval from the institutional ethics committee. Healthy volunteers were chosen for the study from among those attending the outpatient and inpatient department of this institute for ailments other than those affecting the spine, pelvis or hips. All volunteers were of Indian origin, however, details regarding ethnic subgroups was not collected. Adults between the ages of 18–50 were included, both men and women with normal LS spine, pelvic and hip anatomy. Spinal and pelvic development is complete by the late teen years, thus spinopelvic parameters become fixed by this age and do not vary with further aging. We excluded persons beyond age 50 to exclude those with possible degenerative spinal pathologies that can disturb spinal sagittal balance and give us deranged values of the spinopelvic parameters. Persons with any history of infectious/traumatic/degenerative/inflammatory/neoplastic or any other pathology affecting the spine, pelvis or hips were excluded from the study.

For each volunteer we obtained a standing lateral radiograph of the lumbosacral spine with both hips. The x-rays were done on ST S1012004 Varian Medical System. (Mfg. date: September 2014, Housing model no. B1304 Varian tube A 292, Insert serial no.7669743). The X-ray was taken with the volunteer standing erect, looking forward, both hips and knees extended and arms crossed over the chest. Extent of the x-ray was from just proximal to the L1 vertebra above, up to distal to the femur heads below. An X-ray was considered acceptable when the femur heads overlapped in such a way that the centers of the femur heads were no more than 2 mm apart (Fig. 1). If the femoral heads were not perfectly superimposed, then the middle of the segment between the two head centers was considered to be the center of the femoral heads (midpoint of the bicoxofemoral axis). All radiographs were taken by the same technician in exactly the same manner to avoid any error. X-rays were analyzed using Horos 2.0.2 software.

Fig. 1.

X-ray showing overlapped femoral heads.

The parameters studied were defined as follows:

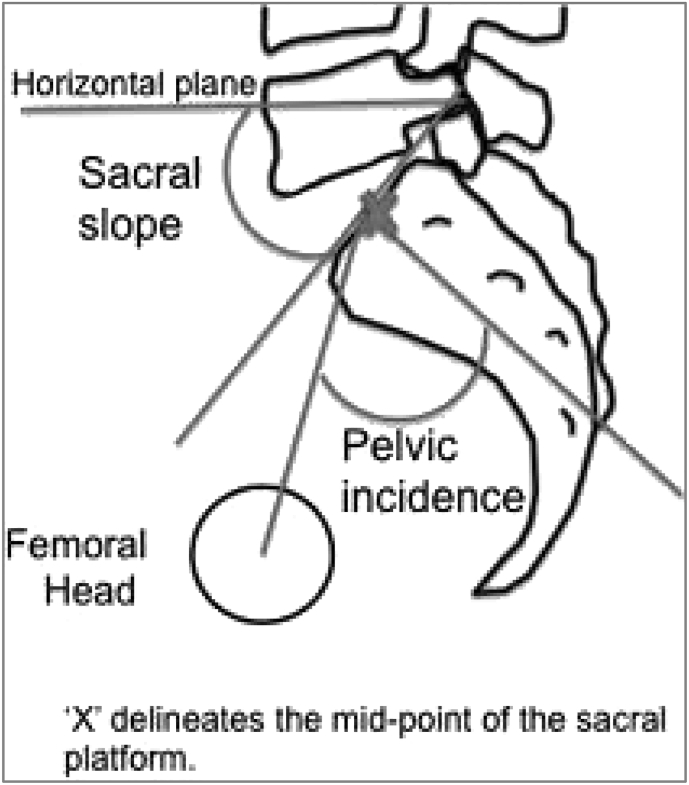

Pelvic incidence: It is the angle subtended by a line which is drawn from the center of the femoral heads to the midpoint of the sacral endplate and a line perpendicular to the center of the sacral endplate (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

X-ray showing Pelvic Incidence.

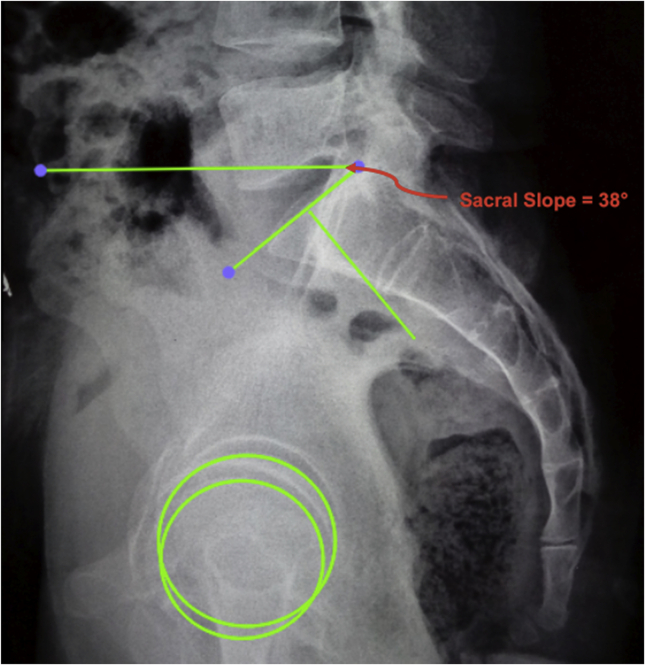

Sacral slope: It is the angle between the superior sacral endplate and a horizontal reference line. Sacral slope determines the position of lumbar spine, since the sacral plateau forms the base of the spine (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

X-ray showing Sacral Slope.

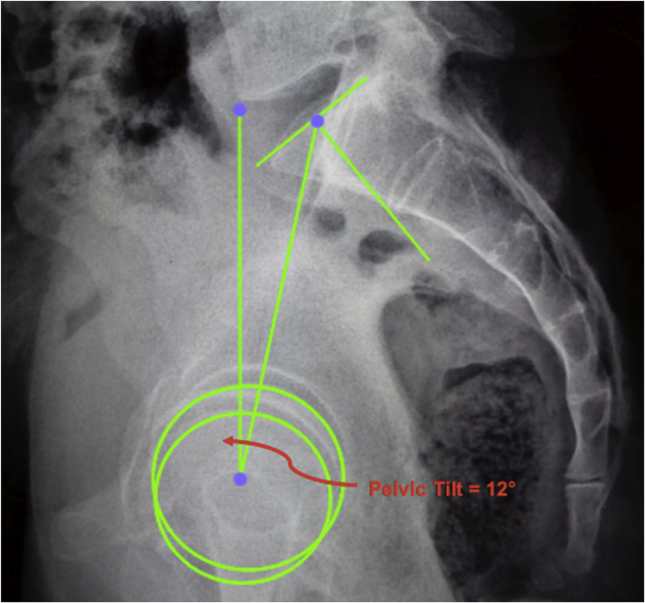

Pelvic tilt: It is the angle between the line connecting the midpoint of the superior sacral plate to the center axis of the femoral heads and a vertical reference line. It denotes the spatial orientation of the pelvis (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

X-ray showing pelvic tilt.

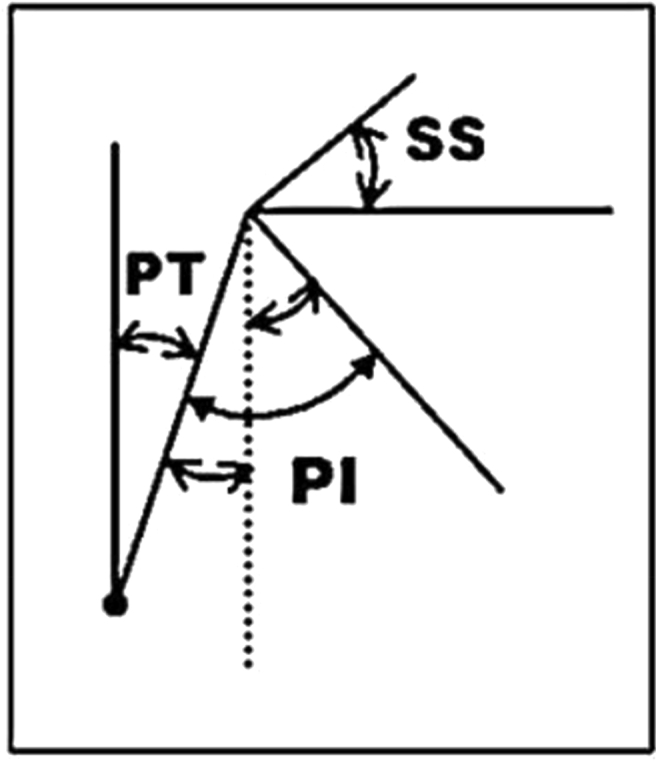

A simple geometrical construction based on the properties of right-angled triangles shows the incidence (PI) to be the sum of the pelvic tilt (PT) and the sacral slope (SS).2 The latter two parameters are positional angles and vary inversely to one another (Fig. 5).

| PI = PT + SS |

Fig. 5.

Pelvic incidence (PI) is a sum of Pelvic Tilt (PT) and Sacral slope (SS).

Since the value of the incidence is fixed for a given patient, the sum of the pelvic tilt and the sacral slope is inversely related, and as one increases, the other necessarily decreases (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Since the value of the incidence is fixed for a given patient, the sum of the pelvic tilt and the sacral slope is inversely related, and as one increases, the other necessarily decreases.

3. Results

The spinopelvic parameters studied were the pelvic incidence angle (PI), sacral slope angle (SS), and pelvic tilt angle (PT). The mean value of PI was 51.50° (±6.85°), ranging from 36° to 66°. The mean value of SS was 39.17° (±6.26°) ranging from 20° to 54°. The mean value of PT was 12.32° (±5.41°), ranging from 1° to 26° (Table 1).

Table 1.

Spinopelvic parameters measured.

| Parameters | Age | PI | SS | PT |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 34.49 | 51.50 | 39.17 | 12.32 |

| Median | 35.00 | 52.00 | 40.00 | 11.00 |

| Std. Deviation | 8.53 | 6.85 | 6.26 | 5.41 |

| Minimum | 19.00 | 36.00 | 20.00 | 1.00 |

| Maximum | 50.00 | 66.00 | 54.00 | 26.00 |

The spinopelvic parameters for male and female sex in the study population were calculated separately and compared. We found a statistically significant difference between males and females for pelvic incidence and pelvic tilt, with p-values of 0.019 and 0.007 respectively. However, the difference between the sexes for sacral slope was not statistically significant (p-value = 0.822). (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of spinopelvic parameters between males and females.

| Variables | Gender | N | Mean | SD | Mean diff. | p- value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PI | F | 65 | 50.12 | 6.68 | −2.79 | 0.019 |

| M | 65 | 52.91 | 6.79 | |||

| SS | F | 65 | 39.05 | 6.29 | −0.25 | 0.822 |

| M | 65 | 39.29 | 6.27 | |||

| PT | F | 65 | 11.08 | 4.76 | −2.51 | 0.007 |

| M | 65 | 13.59 | 5.76 |

We performed Pearson's correlation analysis to find the degree of correlation between the various parameters, mainly our fixed parameter of pelvic incidence and the variable parameters of sacral slope and pelvic tilt. The strongest positive correlation was between pelvic incidence and sacral slope, with a r-value of 0.668. (Table 3).

Table 3.

Pearson's correlation analysis.

Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

We compared the values of our study with values of similar studies conducted in other parts of the country. A considerable difference was found between the measured values in our study and those of other similar studies in the same country. Table 4 shows the comparison made between various similar studies regarding the normal spinopelvic parameters. Pelvic incidence in the South Indian study6 was 58.4 ( ±12.59), compared to 55.48 ( ±5.31) in North Indian study5 and 49.04 ( ±7.6) in the Surat study.7 Our study on the other hand revealed pelvic incidence to be 50.12 ( ±6.85). This showed a statistically significant difference for pelvic incidence between our values and the values of north and south Indian studies with p-values <0.01. However, values of the Surat study did not differ significantly from ours (p-value = 0.85).

Table 4.

Comparison of our study with various similar studies within the country.

| Parameter | Our study |

South Indian study |

North Indian study |

Surat study |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ganesan Ram Ganesan et al.6 |

G. Sudhir et al.5 |

Shiblee S. Siddiqui et al.7 |

||||||

| (n = 130) |

(n = 120) |

(n = 101) |

(n = 84) |

|||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Pelvic Incidence | 50.12 | 6.85 | 58.64 | 12.59 | 55.48 | 5.311 | 49.04 | 7.6 |

| Sacral Slope | 39.05 | 6.26 | 41.3 | 11.01 | 35.99 | 7.531 | 37.4 | 6.6 |

| Pelvic Tilt | 11.08 | 5.41 | 14.2 | 7.32 | 17.97 | 7.167 | 13.9 | 5.8 |

| p- value (PI,SS,PT) | (p < 0.01, 0.02, <0.01) | (p < 0.01, <0.01, <0.01) | (p-0.85, 0.96, 0.024) | |||||

Sacral slope measured 39.05 ( ±6.26) in our study, was compared to values of 41.3 ( ±11.01) in the South study,6 37.4 ( ±6.6) in the Surat study,7 and 35.999 ( ±7.53) in the North study.5 The sacral slope was statistically different between our study and the north and south studies with p-values of <0.01 and 0.02 respectively. Once again, values of the Surat study did not differ significantly (p-value = 0.96). Finally, pelvic tilt showed a considerably wide variation with a value of 11.08 ( ±5.41) in our study, as compared to 14.20 ( ±7.32) in the South, 17.97 ( ±7.16) in the North and 13.9 ( ±5.8) in the Surat study. The difference was significant across all the studies with p-values of <0.01, <0.01 and 0.024 for the north, south and Surat studies respectively.

Thus, considerable differences also exist between the calculated values in our study and similar studies conducted in tertiary care centers in Delhi,5 Chennai6 and Surat.7 However, the correlation between the individual spinopelvic parameters appear to be similar across studies, although the precise strength of association, as indicated by the values of the regression co-efficients, do vary.

Finally, a comparison of the values of our study with those of studies in Brazil (Raphael de Rezende Pratali et al.8), France (G. Vaz et al.9) and Korea (Lee CS et al.10) is given below. The present study indicates that spinopelvic parameters in normal, asymptomatic Indian persons appear to be similar to those found in their Caucasian counterparts, but differ from those in Brazil and Korea (Table 5).

Table 5.

Comparison of our study with similar studies among various countries.

| Parameters | India Our study (n = 130) |

Brazil Raphael de Rezende Pratali et al.8 (n = 50) |

France G. Vaz et al.9 (n = 100) |

Korea Lee CS et al.10 (n = 86) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average | SD | Average | SD | Average | SD | Average | SD | |

| Pelvic Incidence (°) | 50.12 | ±6.85 | 48.7 | ±9.6 | 51.7 | 11.5 | 47.8 | ±9.5 |

| Sacral Slope (°) | 39.05 | ±6.26 | 38 | ±8.4 | 39.4 | 9.3 | 36.3 | ±8.6 |

| Pelvic Tilt (°) | 11.08 | ±5.41 | 12.15 | ±6.2 | 12.3 | 5.9 | 11.5 | ±5.4 |

Summary of the Results: (Table 6):

-

1.

The mean value of PI was 51.50° (±6.85°), ranging from 36° to 66°.

-

2.

The mean value of SS was 39.17° (±6.26°) ranging from 20° to 54°.

-

3.

The mean value of PT was 12.32° (±5.41°), ranging from 1° to 26°.

-

4.

The mean value of PI in women was 52.91° (±6.79°), whereas in men it was 50.12° (±6.68°). The difference between the sexes was thus statistically significant with a p-ˇvalue of 0.019.

-

5.

The mean value of SS in women was 39.05° (±6.29°), whereas in men it was 39.29° (±6.27°). The difference between the sexes was insignificant (p-ˇvalue of 0.822).

-

6.

The mean value of PT in women was 11.08° (±4.76°), whereas in men it was 13.59° (±5.76°). The difference between the sexes was thus statistically significant with a p-ˇvalue of 0.007.

-

7.

There was a positive correlation between PI and SS with r-ˇvalue of 0.668.

-

8.

There was a positive correlation between PI and PT with r-ˇvalue of 0.499.

-

9.

There was a negative correlation between SS and PT with r-ˇvalue of −0.298.

Table 6.

Mean and Range for PI/ SS/ PT.

| Mean value | women | men | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PI | 51.50° (±6.85°), ranging from 36° to 66°. | 52.91° (±6.79°), | 50.12° (±6.68°) | 0.019 |

| SS | 39.17° (±6.26°) ranging from 20° to 54°. | 39.05° (±6.29°), | 39.29° (±6.27°). | 0.822 |

| PT | 12.32° (±5.41°), ranging from 1° to 26°. | 11.08° (±4.76°) | 13.59° (±5.76°) | 0.007 |

4. Discussion

Pelvic incidence is a fixed anatomic parameter. It is unique to each individual, independent of the orientation of the pelvis. It is independent of age once growth is complete. On the other hand, sacral slope and pelvic tilt are variable parameters, determined by the orientation of the pelvis. They are variable to a limit predetermined by a person's unique pelvic incidence. Pelvic incidence is the algebraic sum of sacral slope and pelvic tilt.

In pathological states, there is loss of the normal sagittal curves of the thoracic and lumbar spine, resulting in a straighter profile which is not biomechanically efficient.11 The center of gravity is shifted anteriorly, producing a tendency to stoop forwards which interferes with forward gaze. In an attempt to correct this, the pelvis is tilted backwards thus decreasing the sacral slope. However, the pelvis can only tilt backwards up to the point when the sacral slope becomes zero. Thus, it follows that patients with a large pelvic incidence have a greater capacity to alter pelvic orientation in order to restore sagittal balance. Those with a smaller pelvic incidence will use up their compensatory capacity early, and thereafter will manifest with a sagittal plane imbalance. Furthermore, the use of these compensations leads to a less efficient posture. Tilting the pelvis backwards requires extension at the hips, flexion at the knees and dorsiflexion at the ankles to maintain balance. This uses a good deal of energy and is an inefficient posture causing fatigue and muscle pain.

A review article by Jean-Charles Le Huec et al.12 studied the relationship between sagittal balance and clinical outcomes in surgical treatment of degenerative spinal diseases. They emphasized that the theoretical pelvic tilt and sacral slope values for a given pelvic incidence value must be known before the intervention in order to perioperatively restore the appropriate lumbar lordosis value. Only lumbar lordosis restoration will allow the pelvis to rotate forward to return to the normal theoretical pelvic tilt and sacral slope values, because pelvic incidence is a constant anatomical parameter. Restoring lordosis proportional to the pelvic incidence value is essential.

In 2011, a review article by Vivek A. Mehta et al.13 highlighted the role of abnormal pelvic incidence and other spinopelvic parameters in isthmic spondylolysis, spondylolisthesis, degenerative spondylolisthesis, spinal deformity, fixed sagittal imbalance (FSI) and adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (AIS). The authors stated that there is an acceptable range of values of lumbar lordosis for a given pelvic incidence to preserve sagittal balance. In an imbalanced state, compensatory mechanisms may occur at the spine and pelvis, in an attempt to maintain alignment. Most commonly, pelvic retroversion occurs manifested by an increased pelvic tilt. The important point to note is that these maladaptive mechanisms are a part of the disease process itself. Hence, elevated pelvic tilt or reduced lumbar lordosis is associated with pain, poorer outcomes after surgery, and sagittal imbalance. Thus, in surgical intervention for any spinal pathology, it is important to maintain or provide adequate lumbar lordosis for the given pelvic parameters. For example, patients with increased pelvic incidence require increased lumbar lordosis, and vice versa.

The clinical relevance of our study is defining population specific ranges of normal values of spino-pelvic parameters. Our goal when treating any perturbations of sagittal balance is to restore an adequate lumbar lordosis and thoracic kyphosis (which are also complementary to each other), such that the patient does not have to tilt the pelvis in order to maintain sagittal balance. Restoration of sacral slope and pelvic tilt should thus be the goal intra-operatively. Knowledge of the normal values of these parameters is thus necessary when planning surgery, since these parameters are grossly deranged in pathological states. Pelvic incidence is a constant, as mentioned above. Knowing the correlation between pelvic incidence and sacral slope, we can estimate the sacral slope we need to restore based on the patient's specific pelvic incidence. Knowing an individual's pelvic incidence also gives us an idea of the compensatory capacity present. Persons with a low pelvic incidence are predisposed to sagittal imbalance, and also will become symptomatic earlier, even before sagittal imbalance develops.

5. Conclusion

There appears to be considerable variation in the values of the spinopelvic parameters as determined by various studies. These differences can be attributed in large part to ethnic variations. We have determined the normal ranges of the spinopelvic parameters in healthy adults. This study presents the results of analysis of a small sample of healthy Indian adults. The Indian population is a heterogeneous one. One of the limitations of our study is that it is a single center study. However, persons visiting our medical center in Mumbai, belong to several different ethnicities and are from a variety of places from within the country. Hence these results have a pan- India application. This may explain the difference between the results of our study with that of other studies in India itself. This highlights the need to carry out studies specific to individuals of different ethnicities within the country and carry out studies with larger sample sizes. A multi-centric study covering different states in India with a larger sample size will further validate our findings.

Further studies should also be directed towards early detection of individuals at risk of developing disorders of sagittal imbalance, so that interventions can be made at an earlier stage. In further studies, it will be possible to compare this normal population with pathologic populations and to check the variations of shape and balance in spinal disorders. Given the importance of the spinopelvic parameters, the need to describe the parameters differentially in relation to the ethnicity of the studied individual cannot be overemphasized.

Conflicts of interest

There is no conflict of interest to be declared.

Funding

No sources of funding to be declared.

Acknowledgements

Nil.

Contributor Information

Sunil Bhosale, Email: drsunilbhosle09@gmail.com.

Deepika Pinto, Email: deepupinto@gmail.com.

Sudhir Srivastava, Email: ortho.hod.sks@gmail.com.

Shaligram Purohit, Email: shaligrampurohit@gmail.com.

Sai Gautham, Email: saigautham90@gmail.com.

Nandan Marathe, Email: nandanmarathe88@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Le Huec Jean-Charles, Faundez Antonio, Dominguez Dennis, Hoffmeyer Pierre, Aunoble Stéphane. Evidence showing the relationship between sagittal balance and clinical outcomes in surgical treatment of degenerative spinal diseases: a literature review. Int Orthop. 2015;39:87–95. doi: 10.1007/s00264-014-2516-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Legaye J., Duval-Beaupe`re G., Hecquet J. Pelvic incidence: a fundamental pelvic parameter for three-dimensional regulation of spinal sagittal curves. Eur Spine J. 1998;7:99–103. doi: 10.1007/s005860050038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mac-Thiong J.M., Roussouly P., Berthonnaud E., Guigui P. Sagittal parameters of global spinal balance: normative values from a prospective cohort of seven hundred nine Caucasian asymptomatic adults. Spine. 2010;35(22):E1193–E1198. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181e50808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zárate-kalfópulos Barón, Romero-Vargas Samuel, Otero-Cámara Aduardo, Correa Correa Victor, Reyes-Sánchez Alejandro. Differences in pelvic parameters among Mexican, Caucasian, and Asian populations. J Neurosurg Spine. 2012;16:516–519. doi: 10.3171/2012.2.SPINE11755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sudhir G., Acharya Shankar, Kalra K.L., Chahal Rupinder. Radiographic analysis of the sacropelvic parameters of the spine and their correlation in normal asymptomatic subjects. Glob Spine J. 2016;6:169–175. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1558652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ganesan G.R., Sundarapandian R.J., Kannan K.K., Ahmed F., Varthi V.P. Does pelvic incidence vary between different ethnicity? An Indian perspective. J Spinal Surg. 2014;1(4):151–153. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siddiqui Shiblee S., Joshi Johny, Patel Ravish, Patel Manish, Lakhani Dhairya. Evaluation of spinopelvic parameters in asymptomatic Indian population. J Evol Med Dent Sci. 2015;4(13):2186–2191. doi: 10.14260/jemds/2015/314. February 12. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Rezende Pratali Raphael, de Oliveira Luz Charlles, Gonçales Barsotti Carlos Eduardo, Eugenio do s Santos Francisco Prado, Algaves Soares de Oliveira Carlos Eduardo. vol. 13. 2014. pp. 108–111. (Analysis of Sagittal Balance and Spinopelvic Parameters in a Brazilian Population Samplecoluna/columna). 2. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vaz G., Roussouly P., Berthonnaud E., Dimnet J. Sagittal morphology and equilibrium of pelvis and spine. Eur Spine J. 2002;11:80–87. doi: 10.1007/s005860000224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee C.S., Chung S.S., Kang K.C., Park S.J., Shin S.K. 2011. Normal Patterns of Sagittal Alignment of the Spine in Young Adults Radiological Analysis in a Korean Population. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) pp. E1648–E1654. 36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roussouly Pierre, Nnadi Colin. Sagittal plane deformity: an overview of interpretation and management. Eur Spine J. 2010;19:1824–1836. doi: 10.1007/s00586-010-1476-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Le Huec J.C., Aunoble S., Philippe Leijssen, Nicolas Pellet. Pelvic parameters: origin and significance. Eur Spine J. 2011;20(Suppl 5):S564–S571. doi: 10.1007/s00586-011-1940-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mehta V.A., Amin A., Omeis I., Gokaslan Z.L., Gottfried O.N. Implications of spinopelvic alignment for the spine surgeon. Neurosurgery. 2012;70:707–721. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0b013e31823262ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]