Abstract

The quality of water supply is assessed by its physico-chemical and bacteriological properties. This study was carried-out with the aim of determining the contamination level of domestic water sources of Samaru community, Zaria, Northcentral Nigeria in order to observed the trend of change in quality of these water sources, if any. This was with a view to safeguard the public health of the riparian users against a possible outbreak of water borne diseases. Water samples were collected and analyzed for bacteriological and physicochemical quality using standard procedures. The results showed that the mean values recorded for physico-chemical parameters among the domestic water sources were within stipulated limits of WHO for safe drinking water except for chloride mean value of 314 ± 142.4 mg/L recorded in borehole water. The total heterotrophic bacterial counts recorded in tap, borehole, well, reservoir and river water samples (3.67 × 106 ± 1.25 × 106, 5.67 × 106 ± 8.49 × 105, 2.60 × 107 ± 6.09 × 106, 5.07 × 106 ± 1.59 × 106 and 6.02 × 107 ± 3.69 × 106) exceeded the WHO permissible limits for drinking water (<500 cfu/ml). High abundance of isolated bacteria genus such as Enterobacter, proteus, Escherichia, Salmonella and Shigella were recorded in well, river and reservoir water systems. There was a strong positive correlation between the total bacteria count and physico-chemical parameters, which suggested that the parameters influenced bacterial growth. The occurrence of these bacterial geniuses in the water sources are considered capable to cause potential health consequences for the consumers. Therefore, proper purification and treatment of domestic water sources of the Samaru community should be ensured before being used by the riparian users.

Keywords: Domestic water sources, Physico-chemical parameter, Bacteriological quality, Pathogen, Contamination and treatment

Domestic water sources; physico-chemical parameter; bacteriological quality; pathogen; contamination and treatment.

1. Introduction

The earth has an abundance of water but unfortunately, only about 0.3 % is usable by humans that comprise of freshwater and lakes (0.009%), inland seas (0.008%), soil moisture (0.005%), atmosphere (0.001%), rivers (0.0001%), groundwater (0.279%) and other composed of ocean (97.2%), glaciers and other ice (2.15%) (Bibi et al. 2016). Water is an essential part of human nutrition either directly as drinking water or indirectly as constituent of food and served in various other applications of our daily life. Rapid growth of industrialization, urbanization and increase in human population around the globe has led to high demand for good quality water for domestic, recreational, industrial activities and other purposes have continuously threatened value of this resource (Umeh et al. 2005). The vast majority of people living in undeveloped countries still rely on surface waters as their primary sources of water and simultaneously, as their means of waste disposal. A majority of this population depends on unprotected/or contaminated water sources as a means of drinking water which can cause outbreaks of waterborne diseases. A large percentage of the population in developing countries (majorly African countries) lack accessibility to potable water supply thus, they are compelled to use untreated water from other sources such as rivers, reservoir, springs, streams and groundwater for drinking and other domestic purposes (Welch et al. 2000; Jamielson et al. 2004).

The provision of clean drinking water, especially in developing countries like Nigeria, has always been a major challenge (Raji and Ibrahim, 2011). Based on an National Bureau of Statistics (2009) report, about 27 % of rural dwellers in Northcentral or far North of Nigeria, depend absolutely on springs, streams, ponds, rivers, dams and rainwater as main sources of water for their domestic uses due to lack of clean water (Shittu et al. 2008; Taiwo et al. 2012). Water is not only essential for life; it also remains one of the most important vehicles of transmitting disease in humans and an important cause of infant mortality in many developing countries (Ford, 1999). Water is contaminated by various pathogenic microorganisms such as bacteria, fungi, viral, protozoan and other biological organisms; these pathogenic agents have been implicated in various diseases that affect human health. The potential ability of water to transmit microbial pathogens to a great number of people causing subsequent illness is well document in many countries at all levels of economic development (Dufour et al. 2003). Research has shown high prevalence of waterborne diseases such as cholera, diarrhea, dysentery, hepatitis in these regions, claims the lives of at least a hundred thousand of children and adults per year (Raji and Ibrahim, 2011; Oguntoke et al. 2009). According to WHO about 80 % of diseases are cause by water borne due to drinking contaminated water in developing countries (Khan et al. 2013) and about 3.1% deaths occur due to the unhygienic and poor quality of water (Pawari and Gawande, 2015).

In recent years, the health concern because of poor water quality has gained public attention worldwide (Jean, 1999; Barrell et al. 2000; Jean et al. 2006). Most of the microbes that grow in drinking water are heterotrophs requiring essential inorganic nutrients such as phosphate, nitrate and other organic matter that aids their growth under a favorable environmental condition (Miettinen et al. 1996). The addition of nutrients to our drinking water greatly increases the growth of heterotrophic bacteria because this limiting nutrient such as phosphorous play a major ecological role in nature, it is an essential element for microbes growth and the least abundant element compared to carbon (Ward et al. 1982). Water quality is a complex subject, which determines the quality of water and comprises of physical, chemical, hydrological and biological characteristics of water by which the user assessing the acceptability of water" (Mauskar, 2008). The information concerning the water quality of particular waterbodies will provide a useful information for policy makers to formulate management strategy for control, abatement of water pollution and such reliable data can only be obtained through monitoring. Water quality monitoring is paramount especially in these parts of the country to safeguard the public health, to protect the water resources and fundamental tool necessary for the management of freshwater that are main sources of drinking water in the rural and some urban areas (Adah and Abok, 2013). However, water quality monitoring becomes essential for identifying problems and formulating measures to minimize deterioration of water quality. The objective of this research was to provide information on the physico-chemical and bacteriological quality of domestic water sources as well as to discuss its suitability for human consumption based on water quality standards.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. The study area

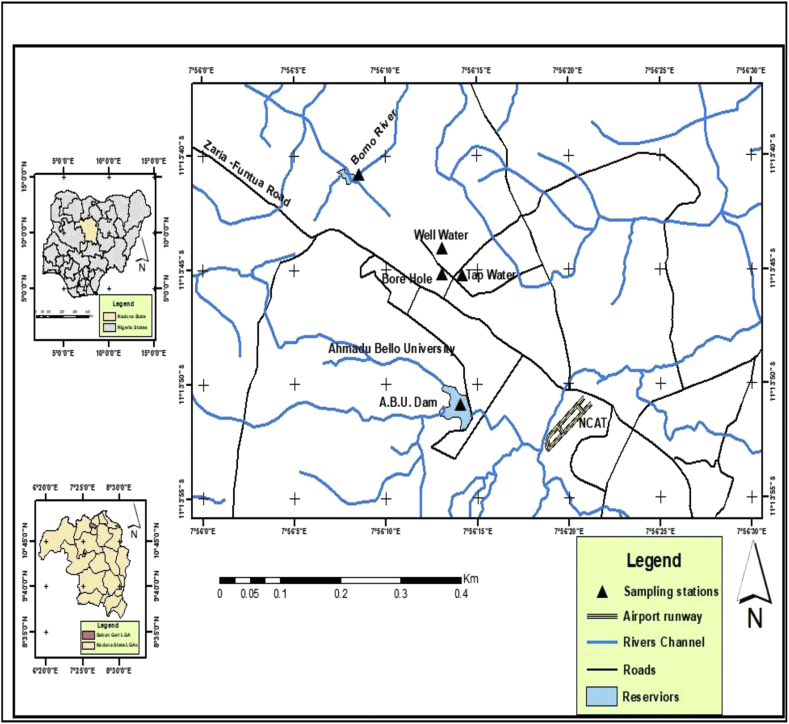

The study areas were located within Samaru, Zaria, Sabon Gari Local Government, Kaduna state, Nigeria. Samaru is located in the Northern Guinea Savannah zone of Nigeria falling within Longitude of 7° 37′ 60″ E and Latitude of 11° 10′00″ N with altitude of 763 m above sea level. It has a tropical climate with a well-defined rainy season, which occurs from May to October and the dry season from November to April. Mean monthly temperature ranges from 13.8 °C to 36.7 °C and annual rainfall of 1090 mm are characteristics of Zaria (Swanta et al. 2013). Samaru as a climate similar to that of Zaria a whole with distinct variation in rainy and dry season. Samaru is a neighborhood in Kaduna state and situated in Zaria a major city in the state. It is predominantly residential area and located in close proximity to the Ahmadu Bello University community and Zaria Aviation School. According to National Population Commission (1991), Samaru has 12, 978 people with 7,417 males and 5,561 females. Based on the 3.0 growth rate of the 1991 census, the population of Samaru was projected to about 18,039 by 2009. The resident of these area depend on water from the rivers, streams, ground waters and reservoirs as major domestic water sources due to lack of potable in this area. The map showing the different sampling location is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Map showing different domestic water sources location within Samaru community, Zaria.

2.2. Sample collection

A total number of five (5) sampling locations were randomly selected with the Global Positioning System (GPS) within Samaru and its environs namely: Hayin dogo (Tap water), Kubanni reservoir, also called ABU dam (Reservoir), Bomo River (River), ground water (Borehole and Well water) from Samaru market. Water samples were collected aseptically bi-monthly from five domestic water sources to covering both seasons. The samples were collected in sterilized plastic bottles of 1000 ml capacity for physico-chemical analysis while 100 ml sampling bottles were used for bacterial analysis. Water samples collected were properly labeled, stored in cooler containing an icebox to maintain stable temperature of 4 °C and immediately transported to the laboratory for further analysis. The water samples were analyzed with the holding time of the respective parameters using standard methods with adequate quality control measures.

Physico-chemical parameters (water temperature, pH and electrical conductivity) were measured in-situ using standard methods (APHA, 2001) with a mercury-in-glass bulb thermometer was used measured water temperature (°C). Hanna Instrument meter (Model H19813-6) previously calibrated with buffer solutions were used for measuring pH while conductivity was measured with a conductivity meter calibrated with potassium chloride solution. The water samples for the determination of dissolved oxygen (DO) were collected in a 250/125ml capacity glass reagent bottles, fixed in the field using Winkler's A (manganous sulphate solution) and Winkler's B (alkali-iodide) reagents and brought to the laboratory for further processing. In the Laboratory, conc. Sulphuric acid was added to free the fixed oxygen inside water sample and they were titrated with sodium thiosulphate solution. Samples for (Biochemical oxygen demand) BOD5 determination were equally collected in glass reagent bottle but were not fixed. BOD water samples were kept in a dark cupboard at room temperature (25 °C) for five days after which its oxygen content was determined by the Winkler methods as described by APHA (2001) was used to determine the amount of dissolved oxygen at the end of the incubation period. Nitrate was determined using Brucine sulphanlic acid method (Marczenko, 1986). Chloride was analyzed by mohr's titration method, spectrophotometric method was adopt in analyzed phosphate while total hardness was also determined by the tritimetic method using a dropper to add Ethylenediamine tetra-acetic acid (EDTA) solution to the water sample. Parameters obtained were compared with the limits set up by the World Health Organization (2011) and Standards Organization of Nigeria (SON, 2007) for drinking water.

2.3. Bacteriological analyses

The microbiological analysis included total heterotrophic bacterial count and total coliform using serial dilution method and pour plate techniques. Streaking method was used to obtained pure bacterial isolates by sub-culturing a previously incubated plate onto a freshly prepared sterile plate.

2.4. Isolation of Enterobacteriaceae using membrane filtration method

Phenol red indicator, purified by adsorption chromatography was incorporated into lauryl sulphate broth (LSB) used in the membrane filtration method for the detection of Escherichia coli and other coliform bacteria. Relative to LSB containing the impure dye or its major contaminant, the purified phenol red provided clear visualization of discrete yellow colonies observed against a white background. The colonies remained stable for at least 24 h at 25 degrees (ºC) under standard laboratory lighting conditions.

2.5. Pre-enrichment (non-selective enrichment)

Water samples (100 ml) were filtered through a sterile (0.45 μm) milipore membrane filter. The membrane filter was lifted with a blunt edge forceps and transferred into 90 ml of buffered peptone water and gently mixed then incubated for overnight at 37 °C.

2.6. Selective enrichment

A 1 ml volume of the pre-enrichment agar was transferred with a pipette into 10 ml Rappaport-Vassiliadis Soy Peptone (RVS) broth was incubated at 37 °C.

2.7. Serial dilution and selective plating

Serial dilution of 10−6 was prepared using normal saline and a loopful of culture was streaked on selective agar Salmonella-shigella agar (SSA) and incubated at 37 °C overnight. Colonies on the Salmonella-shigella agar were then counted and subjected to biochemical test.

2.8. Coliform determination

The multiple tube fermentation method was used according to the methodology described in APHA (2001) beginning with 250 mL flasks and using lactose broth for the presumptive test and brilliant green and EC (E. coli) broth for the confirmation tests. The most probable number (MPN) of total coliform counts was calculated using the Hoskins table (APHA, 2001). Aliquots of the positive tubes of brilliant green broth were collected and streaked onto MacConkey (MC) agar. Colonies with different morphotypes were collected and transferred into tubes containing tryptic soy agar (TSA) and incubated at 37 °C for 24–48 h for subsequent biochemical identification.

2.9. Biochemical identification

For biochemical identification, oxidase-negative bacteria were selected, and the colonies were subjected to biochemical tests using IMVIC characterization reaction from the nutrient slant used in completed test. The bacterial isolates were view microscopic or/macroscopic and characterized using colonial, morphological and biochemical identification methods that were further identified using Bergey's manual of Determinative Bacteriology.

2.10. Statistical analysis

Data collected were subjected to inferential statistical analysis and Analysis of variance (ANOVA) to determine the physico-chemial and bacteriological quality variations among the domestic water sources. Principal Component Analysis to compared relationship between physcio-chemical and bacteriological quality among domestic water sources by using SPSS 25, Past 3.0 software.

3. Results

3.1. Physico-chemical parameters in domestic water sources

The physico-chemical parameters of water samples collected from five different domestic water sources from Samaru community during the study period are shown in Tables 1 and 2. The water quality observed during this study were compared with World Health Organization (WHO, 2011) and Standard Organization of Nigeria (SON, 2007) acceptable levels in the guidelines for drinking water is reported. The highest pH mean concentration was recorded from river water sample (7.28 ± 0.16) compared with the reservoir water sample (6.35 ± 0.13) and there was significant difference (p < 0.05) among the surface water samples. The overall water temperature observed at the period of study ranged from 26.1 - 31.5 (°C) while the highest mean water temperature was recorded from river water sample (28.07 ± 1.22 °C) and lowest was observed in reservoir water sample (27.93 ± 1.03 °C). The conductivity and TDS concentration ranged widely from 102- 484 (μS/cm) and 51–242 mg/L was recorded in surface water samples. Significantly, the mean values of BOD observed between reservoir and river water sample differ greatly and the highest mean was recorded in river water sample. The highest DO and phosphate mean concentrations (3.67 ± 0.61 mg/L and 0.049 ± 0.005 mg/L) were obtained from water sample collected from reservoir while higher mean value of sulphate (0.218 ± 0.07 mg/L) was recorded from river water sample. The highest mean concentration of total hardness was recorded in river water sample (422.67 ± 23.79 CaCO3mg/L) and there was highly significant difference (p < 0.01) between the mean value of total hardness obtained from river and reservoir water sample. The lowest mean value of alkalinity was obtained from reservoir water sample (8.0 ± 1.49 CaCO3mg/L) while highest was observed from river water sample (26.33 ± 2.25 CaCO3mg/L) and there was significant difference among the surface water samples. The highest chloride mean concentration was recorded from reservoir water sample while higher mean value of nitrate was obtained from river water sample. The maximum mean values of 6.40 ± 0.11 and 27.57 ± 0.81 °C were recorded for pH and water temperature from borehole water sample. The TDS and conductivity values ranged of 79.0–546 mg/L and 40.0–256 μS/cm were observed from ground water and there is high significant different (p < 0.001) among the mean value of TDS and conductivity recorded from groundwater samples. The highest BOD mean value was recorded from well water sample (1.7 ± 0.39 mg/L) while the maximum DO mean concentration was observed from tap water sample and phosphate mean concentration was higher in borehole water sample. High mean sulphate concentration was recorded from borehole water (0.325 ± 0.010 mg/L) while lower mean value was obtained from well water (0.034 ± 0.002 mg/L) and there significant differences (p < 0.001) between different ground water sources. Significantly, the mean concentration of total hardness obtained from the groundwater samples differ greatly. Maximum mean alkalinity concentration was observed at well water sample and there was high significant differences (p < 0.001) between different groundwater sources. Lowest chloride mean value was recorded from tap water sample (19.33 ± 3.40 mg/L) while highest value was observed from borehole water sample (314 ± 142.4 mg/L) and there was significant different (p < 0.01) among the various groundwater sources. The ranged of 0.2–3.2 mg/L was recorded from underground water for nitrate during the period study while 0.3–5.32 mg/L and 1.1–7.32 mg/L were recorded from reservoir and river water samples.

Table 1.

Physico-chemical and bacteriological quality of Surface water samples.

| Parameter | Surface water |

Student t-test |

WHO (2011) | SON (2007) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reservoir |

River |

|||||||

| Min-Max | Mean ± Sem | Min-Max | Mean ± Sem | t | p | |||

| pH | 6.14–6.7 | 6.35 ± 0.13 | 7.02–7.73 | 7.29 ± 0.16 | 22.66 | 0.0031∗ | 6.5–8.5 | 6.5–8.5 |

| Water temperature (°C) | 26.1–30.8 | 27.93 ± 1.03 | 26.0–31.5 | 28.07 ± 1.22 | 0.006978 | 0.936 | - | 22–32 |

| Conductivity (μS/cm) | 102–484 | 235.33 ± 87.99 | 125–135 | 128.67 ± 2.25 | 1.468 | 0.271 | <1000 | 1000 |

| TDS (mg/L) | 51–242 | 117.67 ± 43.99 | 62.0–68.0 | 64.33 ± 1.31 | 1.468 | 0.271 | 600 | 500 |

| BOD (mg/L) | 0.9–2.7 | 1.37 ± 0.17 | 0.3–3.5 | 1.4 ± 0.04 | 30.58 | 0.002∗∗ | - | - |

| DO (mg/L) | 2.0–4.9 | 3.67 ± 0.61 | 1.6–5.9 | 2.17 ± 0.27 | 5.025 | 0.066 | <5 | 3–5 |

| Phosphate (mg/L) | 0.041–0.062 | 0.049 ± 0.005 | 0.026–0.047 | 0.037 ± 0.004 | 3.738 | 0.101 | <5 | 10 |

| Sulphate (mg/L) | 0.048–0.451 | 0.183 ± 0.09 | 0.1–0.431 | 0.218 ± 0.07 | 0.08674 | 0.778 | 250 | 250 |

| Total hardness (CaCO3mg/L) | 208–292 | 256 ± 17.66 | 376–488 | 422.67 ± 23.79 | 31.63 | 0.001∗∗ | 500 | 300 |

| Alkalinity (CaCO3mg/L) | 5.0–12.0 | 8.0 ± 1.47 | 21.0–32.0 | 26.33 ± 2.25 | 46.54 | 0.0005∗∗∗ | 120 | - |

| Chloride (mg/L) | 3.2–30 | 17.07 ± 5.48 | 5.0–18.0 | 11.9 ± 2.67 | 0.7184 | 0.4292 | 250 | 250 |

| Nitrate (mg/L) | 0.3–5.32 | 3.43 ± 1.11 | 1.1–7.32 | 4.77 ± 1.33 | 0.5989 | 0.4684 | <50 | 10 |

| THBC (cfu/ml) | 1.20 × 106-9.00 × 107 | 5.06 × 106 ± 1.59 × 106 | 5.30 × 107-7.10 × 107 | 6.20 × 107 ± 3.67 × 106 | 202.1 | 7.588 × 10−6∗∗∗ | <500 | - |

∗significant difference (p < 0.05).

∗∗ High significant difference (p < 0.01).

∗∗∗Very high significant difference (p < 0.001).

Table 2.

Physico-chemical and bacteriological quality of groundwater samples.

| Parameter | Ground water |

Anova |

WHO (2011) | SON (2007) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tap |

Borehole |

Well |

||||||||

| Min-Max | Mean ± Sem | Min-Max | Mean ± Sem | Min-Max | Mean ± Sem | F | P | |||

| pH | 6.0–6.45 | 6.17 ± 0.09 | 6.2–6.7 | 6.40 ± 0.11 | 6.24–6.4 | 6.31 ± 0.03 | 1.703 | 0.2359 | 6.5–8.5 | 6.5–8.5 |

| Water temperature (°C) | 26.2–29.1 | 27.38 ± 0.63 | 26.0–29.8 | 27.57 ± 0.81 | 26.2–29.7 | 27.5 ± 0.78 | 0.01606 | 0.9841 | - | 22–32 |

| Conductivity (μS/cm) | 79.0–95.0 | 85.33 ± 3.47 | 227–301 | 275 ± 16.99 | 449–546 | 486.67 ± 21.23 | 160.9 | 9.033 × 10−8∗∗∗ | <1000 | 1000 |

| TDS (mg/L) | 40.0–47.0 | 42.67 ± 1.55 | 113–150 | 137.33 ± 8.61 | 224–276 | 244 ± 11.43 | 147 | 1.343 × 10−7∗∗∗ | 600 | 500 |

| BOD (mg/L) | 1.0–2.0 | 1.5 ± 0.20 | 0.5–1.1 | 0.8 ± 0.12 | 0.6–2.4 | 1.7 ± 0.39 | 3.165 | 0.091 | - | - |

| DO (mg/L) | 3.0–4.3 | 3.57 ± 0.27 | 2.2–3.3 | 2.67 ± 0.23 | 2.7–3.65 | 3.18 ± 0.19 | 3.699 | 0.06721 | <5 | 3–5 |

| Phosphate (mg/L) | 0.035–0.078 | 0.060 ± 0.009 | 0.036–0.255 | 0.115 ± 0.049 | 0.032–0.079 | 0.053 ± 0.009 | 1.303 | 0.3185 | <5 | 10 |

| Sulphate (mg/L) | 0.046–0.056 | 0.051 ± 0.002 | 0.298–0341 | 0.325 ± 0.010 | 0.028–0.039 | 0.034 ± 0.002 | 775.8 | 8.399 × 10−11∗∗∗ | 250 | 250 |

| Total hardness (CaCO3mg/L) | 120–220 | 173.33 ± 20.548 | 144–240 | 186.67 ± 19.96 | 208–280 | 249.33 ± 15.17 | 4.702 | 0.0399∗ | 500 | 300 |

| Alkalinity (CaCO3mg/L) | 7.0–10.0 | 8.67 ± 0.62 | 23.0–44.0 | 36.67 ± 4.84 | 47.0–54.0 | 50.67 ± 1.44 | 53.11 | 1.04 × 10−5∗∗∗ | 120 | - |

| Chloride (mg/L) | 10.0–26.0 | 19.33 ± 3.40 | 70.0–219 | 314 ± 142.4 | 18.0–120 | 72.67 ± 20.98 | 9.613 | 0.005837∗∗ | 250 | 250 |

| Nitrate (mg/L) | 0.2–0.9 | 0.63 ± 0.15 | 0.4–2.0 | 1.3 ± 0.33 | 0.2–3.2 | 1.87 ± 0.62 | 2.18 | 0.169 | <50 | 10 |

| THBC (cfu/ml) | 1.0 × 106-7.0 × 106 | 3.67 × 106 ± 1.2 × 106 | 4.0 × 106-8.0 × 105 | 5.67 × 106 ± 8.49 × 103 | 1.50 × 107-4.30 × 107 | 2.60 × 107 ± 6096447 | 11.61 | 0.003214∗∗ | <500 | - |

∗significant difference (p < 0.05).

∗∗ High significant difference (p < 0.01).

∗∗∗Very high significant difference (p < 0.001).

Seasonally, the highest pH mean concentration were recorded during rainy season in all domestic water sources compared with dry season as presented in Table 3. The mean values recorded for water temperature were higher during the dry season than rainy season except for borehole water sample. Conductivity and TDS mean concentration were higher in the dry season among the surface and underground water samples but tap water sample was high in rainy season. The highest BOD mean values was recorded from underground water samples during rainy season while highest was recorded from surface water samples in dry season. The DO mean concentration was higher in rainy season among the various underground water samples while the highest was observed during rainy season for reservoir and in dry season for river water sample. High phosphate mean concentration was recorded among the domestic water samples during this study was higher in rainy season compared with dry season. The total hardness mean concentration recorded in underground water samples was higher in the dry season except for tap water while highest was recorded in the rainy season for reservoir water sample and during dry season in river water samples. Nitrate mean concentration was higher during rainy season among domestic water sample than dry season. The mean value of chloride was higher in all underground water samples during dry season but higher in surface water samples in rainy season.

Table 3.

Seasonal variation of bacteriological quality and physico-chemical parameters of domestic water samples.

| Parameters | Groundwater |

Surface water |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tap |

Borehole |

Well |

Reservoir |

River |

||||||

| Rainy season | Dry season | Rainy season | Dry season | Rainy season | Dry season | Rainy season | Dry season | Rainy season | Dry season | |

| Physico-chemical parameters | ||||||||||

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | |

| pH | 7.69 ± 1.02 | 6.37 ± 0.03 | 6.55 ± 1.09 | 5.02 ± 0.32 | 7.87 ± 1.29 | 6.19 ± 0.19 | 6.98 ± 1.14 | 6.24 ± 0.32 | 7.75 ± 0.82 | 6.70 ± 0.83 |

| Water temperature (°C) | 24.97 ± 1.44 | 27.677 ± 1.69 | 27.55 ± 1.30 | 28.10 ± 1.97 | 24.817 ± 1.51 | 27.81 ± 1.87 | 25.78 ± 1.39 | 28.06 ± 2.31 | 25.03 ± 1.28 | 28.39 ± 2.44 |

| Conductivity (μS/cm) | 100.73 ± 17.05 | 91.007 ± 9.24 | 160.03 ± 68.14 | 193.00 ± 122.58 | 230.2 ± 153.79 | 296.25 ± 243.96 | 133.87 ± 195.62 | 231.00 ± 162.99 | 121.70 ± 42.75 | 238.75 ± 26.21 |

| TDS (mg/L) | 66.20 ± 19.65 | 57.51 ± 4.04 | 82.07 ± 30.23 | 96.5 ± 61.27 | 139.43 ± 81.71 | 148.75 ± 122.89 | 88.77 ± 89.28 | 149.50 ± 8.35 | 86.27 ± 43.11 | 154.5 ± 13.18 |

| BOD (mg/L) | 0.77 ± 0.44 | 0.76 ± 0.29 | 0.83 ± 0.43 | 0.72 ± 0.63 | 1.153 ± 0.78 | 1.00 ± 0.37 | 1.98.±0.54 | 2.68 ± 0.24 | 1.01 ± 0.55 | 1.20 ± 0.78 |

| DO (mg/L) | 3.97 ± 0.46 | 1.66 ± 0.75 | 3.32 ± 0.84 | 2.28 ± 0.76 | 2.85 ± 0.49 | 2.54 ± 0.58 | 4.80 ± 0.79 | 2.08 ± 0.79 | 2.67 ± 0.56 | 2.73 ± 1.20 |

| Phosphate (mg/L) | 0.69 ± 0.47 | 0.057 ± 0.02 | 0.37 ± 0.48 | 0.12 ± 0.11 | 0.41 ± 0.45 | 0.05 ± 0.02 | 0.39 ± 0.47 | 0.05 ± 0.02 | 0.38 ± 0.48 | 0.04 ± 0.02 |

| Sulphate (mg/L) | 0.33 ± 0.42 | 0.057 ± 0.01 | 0.28 ± 0.31 | 0.18 ± 0.16 | 0.20 ± 0.33 | 0.04 ± 0.01 | 0.20 ± 0.33 | 0.15 ± 0.20 | 0.25 ± 0.34 | 0.08 ± 0.04 |

| Total hardness (CaCO3mg/L) | 193.67 ± 13.57 | 170.007 ± 57.74 | 159.33 ± 40.34 | 189.00 ± 53.20 | 194.67 ± 17.06 | 220.00 ± 71.18 | 226.00 ± 44.36 | 210 ± 70.54 | 264.00 ± 86.52 | 301.00 ± 163.21 |

| Alkalinity (CaCO3mg/L) | 19.57 ± 11.05 | 9.57 ± 0.58 | 25.28 ± 12.32 | 26.5 ± 19.64 | 42.95 ± 28.77 | 30.00 ± 23.85 | 16.12 ± 8.89 | 7.75 ± 2.22 | 24.62 ± 9.91 | 18.00 ± 10.80 |

| Chloride (mg/L) | 18.577 ± 2.22 | 37.10 ± 9.24 | 56.95 ± 89.37 | 281.25 ± 95.27 | 64.12 ± 47.63 | 143.50 ± 51.42 | 26.28 ± 5.86 | 14.3 ± 9.87 | 17.32 ± 4.92 | 14.75 ± 9.22 |

| Nitrate (mg/L) | 1.637 ± 0.76 | 0.55 ± 0.40 | 1.55 ± 0.55 | 0.88 ± 0.81 | 2.08 ± 1.03 | 1.13 ± 1.42 | 2.76 ± 1.59 | 1.68 ± 2.45 | 3.02 ± 1.94 | 2.38 ± 3.32 |

| Bacterial species | ||||||||||

| Enterobacter spp (cfu/ml) | 35 ± 47.258 | 77.5 ± 148.41 | 2.25 ± 3.304038 | 1.5 ± 2.38 | 1.07 × 107 ± 2.14 × 107 | 1.08 × 107 ± 2.14 × 107 | 3.00 × 106 ± 5.19 × 105 | 211.8 ± 441.08 | 1.02 × 105 ± 1.72 × 105 | 1.42 × 107 ± 3.17 × 107 |

| Proteus spp (cfu/ml) | 2.01 × 106 ± 3.36 × 106 | 7.60 × 106 ± 1.49 × 106 | 3.00 × 106 ± 3.82 × 106 | 1.25 × 106 ± 1.29 × 106 | 3.75 × 106 ± 7.50 × 106 | 5502.5 ± 9710.65 | 1.86 × 106 ± 3.99 × 106 | 1.02 × 106 ± 2.23 × 106 | 1.24 × 107 ± 2.77 × 107 | 1.32 × 104 ± 2.45 × 104 |

| Escherichai coli (cfu/ml) | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 | 33.75 ± 44.60 | 29.5 ± 47.19 | 37 ± 39.62 | 21 ± 20.12 | 1.06 × 107 ± 2.37 × 107 | 1308.6 ± 2337.582 |

| Salmonella typhi (cfu/ml) | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 | 55.25 ± 96.69 | 51.5 ± 99.02 | 37 ± 63.600 | 40 ± 62.45 | 201 ± 446.66 | 161 ± 304.31 |

| Shigella spp (cfu/ml) | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 | 3.25 ± 5.85 | 7.5 ± 9.57 | 12.4 ± 158.8 | 44.2 ± 87.26 | 0.2 ± 0.447 | 811 ± 1782.83 |

| THBC (cfu/ml) | 3.20 × 107 ± 2.94 × 106 | 2.00 × 106 ± 1.15 × 106 | 4.43 × 106 ± 3.08 × 106 | 4.25 × 107 ± 2.98 × 106 | 9.93 × 106 ± 7.87 × 106 | 1.55 × 107 ± 1.93 × 107 | 3.51 × 106 ± 3.53 × 106 | 4.50 × 106 ± 3.41 × 106 | 3.41 × 107 ± 3.67 × 107 | 3.42 × 107 ± 3.74 × 107 |

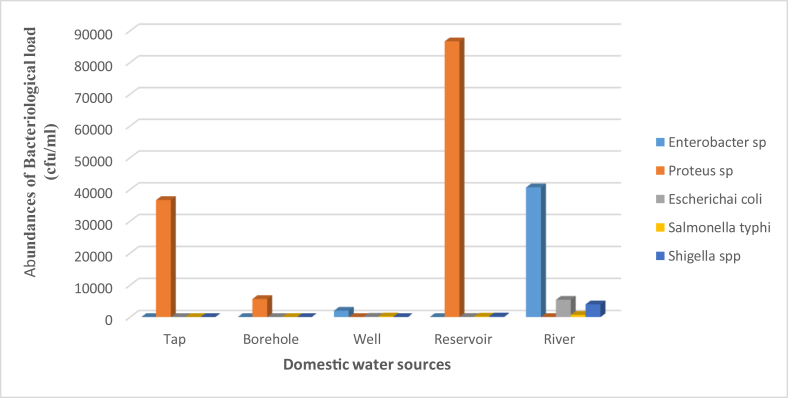

3.2. Bacteriological load in domestic water sources

The total heterotrophic bacteria counts recorded in this study varied widely from 1.2 × 107- 9.0 × 107 cfu/ml with a significant difference (p < 0.001) between the surface water samples. The total heterotrophic bacteria counts ranged from 1.0 × 106- 4.3 × 107 cfu/ml while the highest mean value of 2.6 × 107 ± 6.09 × 107 cfu/ml was recorded in well water sample which was highly significant differences (p < 0.001) between groundwater. The Enterobacter spp highest mean value was recorded in well and river water samples (1.08 × 107 ± 2.14 × 107 cfu/ml and 1.42 × 107 ± 3.17 × 107 cfu/ml) during the dry season while Proteus spp was observed in well and river water samples (3.75 × 106 ± 7.50 × 106 cfu/ml and 1.24 × 107 ± 2.77 × 107 cfu/ml) during rainy season (Table 3). The highest mean for Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhi was observed in well and river water samples (33.75 ± 44.60 cfu/ml and 55.25 ± 96.69 cfu/ml) (1.06 × 107 ± 2.37 × 107 cfu/ml and 201 ± 446.66 cfu/ml) during rainy season. Shigella spp was recorded in well and river water samples (75 ± 9.57 cfu/ml and 811 ± 1782.83 cfu/ml) during dry season (Table 3). The total heterotrophic bacteria counts mean values was higher during rainy season in all underground water samples but higher during dry season among the surface water samples (Table 3). Five types of bacteria were identified during the period of study including Enterobacter Spp, Escherichia coli, Salmonella typhi, Shigella spp and Proteus Spp. Enterobacter spp had the highest frequency in river water followed by well water and least frequency in the tap water and highest occurrence of Proteus spp was observed in reservoir water, followed by borehole water and least in well water but Shigella spp, Salmonella typhi and Escherichia coli were high in river water (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Abundances of bacterial counts observed from different domestic water.

3.3. Biochemical identification

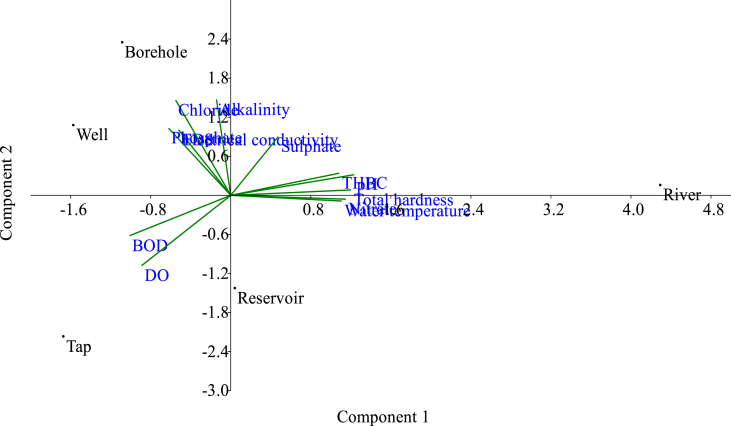

Urea, H2S, indole, motile, MR were positive (+) for Proteus spp (tap water), borehole, reservoir water and Shigella spp (Reservoir) except for VP which was negative. Citrate is positive for Proteus in tap and borehole waters but negative for Salmonella, Shigella and Escherichia in river, well and reservoir waters. H2S, motile and VP showed positive for Enterobacter spp, Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhi in well and river water while biochemical parameters like urea, motile and MR showed negative as shown in Table 4. There was a strong correlation between total heterotrophic bacteria counts and physico-chemical parameters (Table 5). The variable score plot shows variable that cluster within close range with each other when a higher percentage of variable in the data explained. In the factor score plot it shows that there are clear differences between the well, borehole, river, reservoir and tap. The 1st factor showed that there are close relationship between chloride, alkalinity, phosphate, TDS and electrical conductivity clustered in borehole and well water while 2nd factor showed that total heterotrophic bacteria counts, pH and sulphate are related in River water. 3rd factor showed that was association between water temperature, nitrate and total hardness in reservoir and 4th factor showed BOD and DO clustering in Tap water but 2nd factor are not seem to be good cluster when is compared with the 1st factor, 3rd factor and 4th factor. It showed that there is a close relationship between borehole and well water, tap water and reservoir but river water is differ from the rest of domestic water sources (Figure 3).

Table 4.

Biochemical Test Analysis of different Domestic Water Sources.

| Domestic water sources | Biochemical Test |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TSI | Urea | Citrate | H2S | Indole | Motile | MR | VP | Organism | |

| Tap | Alkali/Acid + Gas | + | + | + | + | + | + | - | Proteus spp |

| Borehole | Alkali/Acid + Gas | + | + | + | + | + | + | - | Proteus spp |

| Reservoir | Alkali/Acid + Gas | + | - | + | + | + | + | - | Proteus spp and Shigella spp |

| Well | Acid/Alkali + Gas | - | - | + | - | + | - | + | Enterobacter, salmonella spp |

| River | Acid/Alkali + Gas | - | - | + | - | + | - | + | Enterobacter, Escherichia coli, and Salmonella spp |

Source by Donalson (1980). + specie is present and − specie is absent.

Table 5.

Correlation matrix showing the relationship between bacteriological quality and physico-chemical parameters of domestic water samples.

| Bacteria | pH | Water temperature | phosphate | Sulphate | Chloride | Nitrate | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tap | |||||||

| Bacteria | 0.000 | ||||||

| pH | 0.165 | 0.000 | |||||

| Water temperature | 0.152 | 0.999∗∗∗ | 0.000 | ||||

| phosphate | 0.802∗ | 0.191 | 0.177 | 0.000 | |||

| Sulphate | 0.797∗ | 0.201 | 0.197 | 0.963∗∗∗ | 0.000 | ||

| Chloride | 0.881∗∗ | 0.176 | 0.154 | 0.963∗∗∗ | 0.882∗∗ | 0.000 | |

| Nitrate | 0.797∗ | 0.172 | 0.150 | 0.971∗∗∗ | 0.874∗∗ | 0.988∗∗∗ | 0.000 |

| Borehole | |||||||

| Bacteria | 0.000 | ||||||

| pH | 0.949∗∗ | 0.000 | |||||

| Water temperature | 0.995∗∗∗ | 0.920∗∗ | 0.000 | ||||

| phosphate | 0.762∗ | 0.541 | 0.728∗ | 0.000 | |||

| Sulphate | 0.993∗∗∗ | 0.906∗∗ | 0.998∗∗∗ | 0.701 | 0.000 | ||

| Chloride | 0.885∗∗ | 0.959∗∗∗ | 0.832∗∗ | 0.290 | 0.830∗ | 0.000 | |

| Nitrate | 0.842∗ | 0.915∗∗ | 0.781∗ | 0.180 | 0.786∗ | 0.992∗∗∗ | 0.000 |

| Well | |||||||

| Bacteria | 0.000 | ||||||

| pH | 0.857∗∗ | 0.000 | |||||

| Water temperature | 0.997∗∗∗ | 0.894∗∗ | 0.000 | ||||

| phosphate | 0.903∗∗ | 0.992∗∗∗ | 0.934∗∗ | 0.000 | |||

| Sulphate | 0.984∗∗∗ | 0.922∗∗ | 0.994∗∗∗ | 0.960∗∗ | 0.000 | ||

| Chloride | 0.753∗ | 0.364 | 0.706 | 0.422 | 0.624 | 0.000 | |

| Nitrate | 0.705 | 0.287 | 0.653 | 0.350 | 0.568 | 0.996∗∗∗ | 0.000 |

| Reservoir | |||||||

| Bacteria | 0.000 | ||||||

| pH | 0.784∗ | 0.000 | |||||

| Water temperature | 0.992∗∗∗ | 0.825∗ | 0.000 | ||||

| phosphate | 0.983∗∗∗ | 0.782∗ | 0.958∗∗∗ | 0.000 | |||

| Sulphate | 0.590 | 0.906∗∗ | 0.677 | 0.524 | 0.000 | ||

| Chloride | 0.812∗ | 0.348 | 0.734 | 0.854∗∗ | 0.013 | 0.000 | |

| Nitrate | 0.777∗ | 0.336 | 0.692 | 0.838∗ | -0.026 | 0.994∗∗∗ | 0.000 |

| River | |||||||

| Bacteria | 0.000 | ||||||

| pH | 0.994∗∗∗ | 0.000 | |||||

| Water temperature | 0.989∗∗∗ | 0.985∗∗∗ | 0.000 | ||||

| phosphate | 0.962∗∗∗ | 0.931∗∗ | 0.924∗∗ | 0.000 | |||

| Sulphate | 0.743 | 0.665 | 0.703 | 0.883∗∗ | 0.000 | ||

| Chloride | 0.753∗ | 0.761∗ | 0.653 | 0.806∗ | 0.584 | 0.000 | |

| Nitrate | 0.804∗ | 0.822∗ | 0.718 | 0.819∗ | 0.548 | 0.990∗∗∗ | 0.000 |

Figure 3.

Principal component analysis (PCA) showing relationship between bacteriological load and physico-chemical quality of domestic water sources.

4. Discussion

4.1. Physico-chemical parameters

The physico-chemical parameters and bacteriological analysis for different domestic water source are discussed in relation to WHO and SON guidelines for drinking water quality. The importance of hydrogen ion concentration (pH) of water is evident in the manner by which it affects the chemical reactions and biological activities that occur only within a narrow range (Kolawole et al. 2013). In this present study, the pH concentration trend observed in tap water is slightly acidic and pH range fell within standard acceptable range for drinking waters of 6.5–8.5 (WHO, 2011). This finding is in agreement with Shittu et al. (2008) who reported a similar range for pH of water used for drinking and swimming purposes in Abeokuta, Nigeria. The mean pH values recorded lower than 6.5 are considered to be too acidic for human consumption and can cause health concern such as acidosis infections; and the low pH has synergistic effects on heavy metal toxicity in waterbodies. The pH value ranged of 6.2–6.7 (6.40 ± 0.11) indicating that the borehole water is slightly acidic. However, it falls within the range of pH of 5.5–9.0 of natural waters (Hems, 1985). The pH value recorded for borehole water are similar with the results of Ogbonna et al. (2010) for various groundwater samples who reported that pH of groundwater could be determined by type of soil and free carbon (IV) oxide level in the water. The fluctuations in optimum pH ranges may result in increase or decrease in the toxicity of poisons in waterbodies (Okonko et al. 2008). Well water had pH values varying between 6.24-6.40 (6.31 ± 0.03) which fell within stipulated permissible limit of WHO and SON for drinking water. This could be due to fluctuations in the carbon oxide/bicarbonate/carbonate equilibrium and consequently affect the bacterial counts. Brady (1998) reports that similar quality of water is mostly govern by function of the mineralogical and geochemical characteristics of the rocks underlying of that area. Most minerals in rocks are soluble under appropriate geochemical condition and ground water flows screens out most bacteria's through different types of soil layers. Many unseen dissolved minerals and organic constituents are present in ground water in various concentrations. Most are harmless or even beneficial while others are harmful and a few may be highly toxic. Sojobi et al. (2014) attributed the acidic nature to the geological formation of the area. The pH range of 6.24–6.40 and 7.02 to 7.73 observed for reservoir and river water sample in this present study was within the range reported for some Nigerian rivers such as the River Asa (6.8–8.9) (Otobo, 1995) and the River Kaduna (6.4–7.2) (Samuel et al. 2015). Similarly, the observed pH values fell within the range of Class II (Acceptable Quality) as classified by Prati et al. (1971). The pH values were slightly acidic and alkaline. The variation of pH ranged observed in the reservoir can be explainable in terms of vegetation decay and higher influx into the basin (Ikhile, 2004; Tyokumbur et al. 2002) (Awba stream and Reservoir); Ikomi et al. (2003 (River Adofi). However, pH values obtained in surface waterbody could be linked to the predominant soil type in the area or possibly to the built-up of organic material from runoff. As organic substances decay, carbon dioxide is released and combines with water to produce weak acid “carbonic” acid.

Temperature is one of the major physico-chemical parameters used to assess quality of water for human consumption and control many activities in waterbody such as the rate of chemical reactions, reduction in solubility of gases and amplifications of tastes and colours of water have to be considered (Olajire and Imeppeoria, 2001). The water temperature ranged from 26.0-29.1 °C, 26.0–29.8 °C and 26.2–29.7 °C (tap water, borehole and well) were recorded for underground water sources. Higher water temperature was recorded in borehole water might be as a result of factors such as climatic condition, geographical soil type, and depth of the ground water which may affect the biochemical and physiological activities of organisms found in the water sources (Ekhaise and Anyansi, 2005). The mean water temperature observed during the period of study were within the standard permissible limit of WHO (2008) and SON (2007). This is similar to Oparaocha et al. (2010) who reported the maximum water temperature of 28 °C from different water source in Nigeria but higher than the study conducted in Bahir Dar town (15–20 °C) (Milkiyas et al. 2011). The water temperatures recorded in various underground waters were above the WHO recommended level (<15 °C) and temperature optimal ranged for some aerobic mesophilic bacteria and fungi. This result obtained could be attributed to time of sampling and geographic location of the study area. It is desirable to have the temperature of drinking water not exceeding 15 °C as the palatability of water is enhanced by its coolness WHO (2003). The water temperature ranged obtained from surface water (reservoir and river) was similar to the report of Otobo (1995); Olobaniyi and Owoyemi (2004); Olobaniyi and Owoyemi (2006) who recorded water temperature ranged of 26–31 °C from surface waterbodies in Nigeria. Higher mean values of water temperature recorded in river could be attributed to high atmospheric temperature and exposed to direct solar radiation, low relative humidity and reduction in the amount of suspended particles which occurred as a result of high water transparency and heat from sunlight increasing the temperature of the surface water.

Electrical conductivity measures the degree of ions in water, which greatly affects taste and thus has a significant impact on the user's acceptance of the water. The mean value recorded for all underground water sample were within WHO permissible limit. Findings were related to report of Adetunde and Glover (2011). Electrical conductivity levels varied between 22 to 315 μS/cm from well water samples in Nigeria. The groundwater in this area is suitable for domestic, irrigation and other purposes. The ranged of electrical conductivity values recorded from surface water are generally lower than the permissible limit by WHO for drinking water. Low conductivity indicates that the water receives low amount of dissolved inorganic substances in ionized form from their surface catchments (Kidu et al., 2015). The reduction in conductivity observed in the study area could be attributed to the dilution effect of the increased water volume within waterbodies during the rainy season. Total dissolved solid (TDS) are measures of the general nature of water quality (Olajire and Imeppeoria, 2001). The TDS is total sum of cations and anions in water including carbonate, bicarbonate, chloride, sulphate, phosphate, nitrate, calcium, magnesium, sodium, organic ions and other ions. TDS affect the taste of drinking water if present at levels above the WHO recommended level. The mean values of TDS recorded from underground water were below the desirable limits set by WHO standards and the range of values could be considered tolerable. The results obtained in this study indicate that total dissolved solid (TDS) is between 40.0-47.0 mg/l, 113–1500 mg/l and 224–2760 mg/l from tap water, borehole and well water samples. The present study showed that total dissolved solid values observed from surface water were below the permissible limits of WHO (2011) for drinking water. The high value of TDS recorded from river and reservoir water might be due to agricultural runoff, other human activities like washing. According to Otobo (1995), the concentration and relative abundance of ions in waters is highly variable and depends mainly on the nature of the bedrock, precipitation and evaporation crystallization processes. Dissolved oxygen is one of the most important parameters of water quality that give direct and indirect information on nutrient availability, the level of pollution, metabolic activities of microorganisms, stratification, and photosynthesis in water body (Premlata, 2009). The DO values ranging between 3.0-4.3 mg/L, 2.2–3.3 mg/L and 2.7–3.65 mg/L for tap water, borehole and well water were compared with WHO acceptable standards for drinking water. Temperature of water influences the amount of dissolved oxygen with only lesser oxygen dissolved in warm water than cold water (Tenagne, 2009). Therefore, high temperature of the water sources could be one of the factors for low DO values recorded in the current study. Dissolved oxygen is of great significance to all living organisms; its presence in water bodies can result from direct diffusion from air or production by autotrophs through photosynthesis. The DO values observed during this study period from the surface water sources were within the WHO limits. Decreased in DO mean level observed in the river water samples may be indicative of too many bacteria that may use up the dissolved oxygen in it. Another likely reason for such decreased DO in this water sample may be fertilizer run offs from farmland and lawns. Nduka and Orish (2008) reported that DO oxidizes both organic and inorganic substances, thereby interfering with their capacity to constitute a nuisance to the consumer. Dissolved oxygen may not have a direct health hazard to humans, but it could have effects on other chemicals in the water (Olajire and Imeppeoria, 2001). Dissolved oxygen is an important water quality parameter and has special significance for aquatic organisms in natural waters (Willock et al., 1981). The BOD concentration recorded in underground water samples were within the range of 1.0–2.0 mg/L, 0.5–1.1 mg/L and 0.6–2.4 mg/L from tap water, borehole and well water. However, there ranged obtained from this study were below WHO guideline set for the maximum tolerable limit of BOD in drinking water, for fisheries and aquatic life. The BOD values recorded from surface water samples were within the recommended values of WHO (2008). With the high range of BOD obtained from both river and reservoir, water suggests that drinking water sources were highly polluted by organic matter such as fecal matter and improper disposal domestic waste materials finding their way into waterbody through runoffs. Similarly, other findings also showed that a high level of BOD causes to decrease the value of dissolved oxygen (WHO, 2008). BOD measures the amount of oxygen utilized by microorganisms such as bacterium oxidize organic matter available within the water (Willock et al. 1981; Aniyikaiya et al., 2019; Rachna and Disha, 2016). Detection of phosphate in various groundwater ranging from 0.0035-0.078 mg/L (tap water), 0.036–0.255 mg/L (borehole) and 0.032–0.079 mg/L (well) could be because of geology or topography of that sampling location which contribute to amount of phosphate in this ground water. The ranged of phosphate observed in this study is low due to no seepage from run offs or sewage discharges, because it is a major constituent of fertilizers and detergents. The mean values of phosphate recorded in surface water (river and reservoir) is within acceptable limit of WHO and this indicates contamination of the water sources by run-off from agricultural farms using inorganic fertilizers as most of the people in the study area were practicing farming. These observations indicate that the water from these sources could not be stored for long in open containers, as the presence of phosphate encourages the growth of algae and consequently cause adverse changes at least in colour and taste of the water sources (Taha and Younis, 2009; Agunwamba, 2000). However, the principal significance of high phosphate causes eutrophication, which is more common in lakes and sometimes rivers (Abolude et al. 2016). Hardness is an important parameter in reducing the harmful effect of poisonous elements. The deposition of calcium and magnesium salts in water increases the hardness and pollution of the waters (Bhatt et al. 1999). The soil composition of the sampling sites and lack of casting of the wall of well/or borehole may have contributed to the high total hardness mean recorded in well water sample. People with kidney diseases should avoid high content of calcium and magnesium in water. The value of total hardness recorded in ground water was similar to the reported by Ezeribe et al. (2012) but it is in consonance with the findings of Bello et al. (2013). Total hardness mean observed from surface water sources fell within the maximum permissible limit by WHO for drinking water thus, the water will not precipitate soap, deposit scale and crust accumulation in containers will be highly minimized. The hard water does not pose a health hazard, but constitute a nuisance concerning its use for other domestic activities such as washing and household cleaning. This agrees with the results of Oladimeji and Kolo, 2004 from Shiroro Lake and Ufodike et al. (2001) from Dokowa mine lake. The range of sulphate concentration recorded from ground water samples (0.046–0.056 mg/L in tap water, 0.298–0.341 mg/L in borehole and 0.028–0.039 mg/L in well water) were significantly low comparable to the WHO and SON permissible limit for drinking water of 250 mg/L. The low level of sulphate can be attribute to the geological profile of the soil and the mineral constituent of the source of water sample. Sulphate naturally occur in groundwater by the dissolution of sulphides such as pyrite from the interstratified materials by percolating water producing sulphate ions (Olobaniyi and Owoyemi, 2006). This study revealed a low mean sulphate values from surface water sources and were within the WHO and SON stipulated limits of 250 mg/L. The low concentration of sulphate could be due to the absence of anthropogenic activities that influence the concentration in waterbodies. The average nitrate concentrations recorded from tap water, borehole and well water sample (0.63 ± 0.15 mg/L, 1.3 ± 0.33 mg/L and 1.87 ± 20.62 mg/L) fall below the WHO standard limit for drinking water. The findings was similar to report of Adejuwon and Mbuk (2011); Reimann et al. (2003) who recorded high nitrate concentration of 50.6 mg/l in well water in Ikorodu. The nitrate levels ranging between 0.3-5.23 mg/L and 1.1–7.32 mg/L were recorded from surface water samples. The low variation recorded for nitrate concentration in this study may be due to differences in hydro-geological regimes and agricultural use of nitrates in organic and chemical fertilizers has been a major source of water pollution. Generally, farming remains responsible for over 50% of the total nitrogen discharge into surface waters. Lifetime exposure to nitrite and nitrate at levels above the maximum acceptable concentration could cause such problems as diuresis, increased starch deposits and hemorrhaging of the spleen (Reimann et al., 2003). Antibacterial properties of nitrate may play a key role in protecting the gastrointestinal tract against a variety of gastrointestinal pathogens. The level of chlorine in the ground water samples collected ranging from10.0-26.0 mg/L (19.33 ± 3.40 mg/L), 70.0–219 mg/L (314 ± 142.4 mg/L) and 18.0–120 mg/L (172.67 ± 20.98 mg/L) were recorded from tap water, borehole and well water. The average chloride concentration obtained from borehole water was above the WHO and SON standard limit for drinking water. High concentration of chloride from this study could be due to uses of chlorine as a disinfectant in water purification for human consumption. The level of chloride is due to the natural occurrence of chlorides in the geological strata of borehole and it widely distributed element in all types of rocks in one or the other form (Braide et al. 2004). The chloride range recorded from surface water sample were within stipulated limit by WHO for potable water. Although there were inputs of pollutants from municipal wastes into the river and reservoir but the level was not high, enough to have significantly increase chloride concentrations above the limit. The level of alkalinity values recorded from surface and underground water sources fell within the stipulated limit of 120 mg/L for portable water. The mean alkalinity agreed with the range documented by Moyle (2009) and Boyd (1981) for natural water. The low level of alkalinity indicates that the catchment geology as well as anthropogenic runoff are the main source of natural alkalinity, and probably contains low carbonate, bicarbonate, and hydroxide (Dhameja, 2012).

The mean of alkalinity agreed with the range documented by Moyle (2009) for natural waterbodies. The level of alkalinity ranged recorded reservoir and river water samples were within the stipulated limit of 120 mg/L for portable water (WHO). The low level of the alkalinity indicates that the catchment geology as well as anthropogenic runoff are the main source of natural alkalinity, and probably contains low carbonate, bicarbonate, and hydroxide (Dhameja, 2012). The seasonal fluctuation of physico-chemical parameters obtained in this study could depend on location of the sampling station as well as the activities that go on around the site. The mean values of pH, DO, and Alkalinity were higher in the rainy season maybe due to dilution of water while water temperature, conductivity and TDS were high during dry season. Seasonal variations showed that pH mean was low in the dry season and low pH is known to favour the solubility of ions associated with TDS. The high Electrical conductivity mean values was recorded in surface water sample during dry season when compared to the rainy season. High EC values are mostly associated with wastewater discharges from sewerage, agricultural runoff and industries.

4.2. Bacteriological quality

The mean total heterotrophic bacteria counts recorded in both reservoir and river were above WHO stipulated for drinking water. This study agrees with the report of Doughari et al. (2007) that extremely high total heterotrophic bacterial load in water suggested that the water has been contaminated by potentially dangerous microorganism and unfit for human consumption. Bacterial occasionally, find their way into ground water sometimes in dangerously high concentrations through runoffs or seepage. From this present study, it shows that borehole and well could be contaminated through floodwater forming after rainfall, depending on the depth of the groundwater or through broken underground pipes under this condition, the surrounding floodwater flows into the pipe through the cracks (Nwachukwu and Otokunefor, 2006). The major diseases that could arise from bacteriological contamination of the groundwater include typhoid, diarrhea and cholera. The deeper ground water contains little or no presence of bacteria could have been removed by extensive filtration as water percolates through the soil (Uzoigwe and Agwa, 2012). This was confirmed by the characterization of the isolates from the ground water samples from the sampling locations under study that were highly contaminated with one or more bacterial pathogens. The high bacterial load of genera like Enterobacter, Proteus, Escherichia, Salmonella and Shigella were isolated from well, borehole and tap water samples respectively. The high abundance of bacteria isolated in ground water sample as seen in this study indicate the presence of high feacal contamination and health risk for the human consumption due to high pathogens presence in the water sample (Franciska et al. 2005). According to WHO recommendations, there should no fecal coliforms in 100 ml drinking water and the reason for the gross contamination of ground waters by pathogens as observed in this study may be due to openness and shallowness of this ground water that allows easy entrance of particles from the surroundings. It may also be due to poor sanitary condition around the areas where such wells are located.

Shittu et al. (2008) and Abednego et al. (2013) recorded high number of total coliform count exceeded the WHO permissible limit from water sources in river Ogun. The bacterial species identified from the water samples might be as a result of farming activities practices occurring near the surface water by habitat of the community living around this waterbody, which could result in open defecation along the farmland and there is tendency that the runoffs from these farmlands may be washed into the River. Contamination of surface water maybe due to human activities like bathing, farming, washing, and human or/animal feces seepage run-offs enters the waterbodies and are capable of transmitting a large number of infectious diseases (Anyanwu and Okoli, 2012). The bacterial genus identified during this study can cause meningitis, pneumonia and urinary tract infections in consumers. The coliforms are the primary bacterial indicator for faecal pollution in water and they are most abundant bacteria in water responsible for waterborne diseases such as typhoid, dysentery, diarrhea and also been implicated in mortality across the world (WHO, 2011). The high abundance of bacteria such as Enterobacter, Escherichia, Salmonella and Shigella that were recorded in river and reservoir water in this study could be related to one or to a combination of sewage effluents, such as agricultural run-off and direct fecal contamination from natural fauna (Abulreesh, 2012). Surface water are particularly liable to pollution from animals and birds, and Salmonella spp. may be detected even when only a small number of indicator organisms are present, e.g. Escherichia coli. Additionally, some authors highlighted that the different rates of survival of Salmonella and E. coli in non-host environment suggest that E. coli may not be an appropriate indicator of Salmonella spp. contamination (Polo et al. 1999). Salmonella spp. is a recognized human pathogen and its waterborne transmission has been well-documented Polo et al. 1999). Presence of Salmonella spp. in waterways indicates the spread of the agent in the environment, highlighting the importance of fecal contamination of the water environment in the spread of salmonellosis (Polo et al. 1999; Cabral, 2010). There is a strong positive correlation between bacteriological and some physcio-chemical parameters such as nutrient compound, ions, pH and water temperature that indicate they have influence on the bacteria growth in water. The result obtained maybe caused due to abundance of these nutrients in soil composition or geology type of the sampling location anthropogenic going on around the area. Nutrients which support the growth of bacteria find the way into drinking water after disinfectant has been applied to it through the seepage and when the environmental condition favour their growth. Some disinfectant are selective in killing particular organisms while other survival or develop resistant towards it. Ward et al. (2006) reported that disinfection itself can be selective for a variety of bacteria has been demonstrated by the results of work of several researchers (Armstrong et al., 1982; LeClerc and Mizon, 1978; Murray et al. 1984 who have indicated that chlorination of water supplies select for survivors which are multiply antibiotic resistant such as Flavobacterium strain was more sensitive to monochloramine than to free chlorine. The results indicate that selective pressures of water treatment can produce microorganisms with resistance mechanisms favoring survival in an otherwise restrictive environment. LeChevallier et al. (1993) suggested that the regrowth of coliform bacteria in chlorinated water may be limited by assimilable organic carbon (AOC) levels of less than 50–100 mg/L but heterotrophic bacterial levels in non-chlorinated systems did not increase when assimilable organic carbon (AOC) levels were lower than 10 mg/L.

High bacteria counts mean was recorded among the various ground water samples during the rainy season could be due to runoff from the environment as result of rainfall which can increased the microbial load especially coliforms in water. The finding is similar to that obtained by Esharegoma et al. (2018) who reported high microbial counts during the raining season compared to dry season. This could be attributed to high runoff which increased microbial load washed in from the soil by rainfall, and more nutrients are brought in by the rain through leaching of the soil. In addition, decaying organic matter from the top soil is washed into the water body by the rain, thereby increasing the substrate for organisms. The high mean of microbial was observed in surface water samples during dry season could be attributed to increased nutrient level occasioned by concentration of water through evaporation during dry season (Ouma et al., 2016). This peculiar trend in the occurrence clearly shows that their proliferation is favoured by certain seasonal parameters in the tropics. The high microbial load could also be as a result of higher pH and increase biodegradable organics in the waterbody recorded during the dry season which favored an increase in the microbial population.

5. Conclusion

The findings of this study showed that physico-chemical properties of domestic water sources examined were within safe limits except for chloride concentration (borehole water) and total heterotrophic bacterial counts recorded in all water samples exceed WHO permissible limits for drinking water. All domestic water samples analyzed were contaminated with different types of Bacterial species such as Enterobacter, Escherichia, Salmonella, Shigella and Proteus indicated faecal pollution that can cause waterborne diseases.

6. Recommendation

The health concern of this community required serious attention since people use untreated water for a wide range of domestic purposes. Diseases related to contamination of drinking water constituent which are major burden on human health and intervention to improve the quality of drinking water provide significant benefits to humans health. Therefore, health authorities should make the public aware of potential danger in using untreated water as a source of drinking water and encourage in-house treatment of the raw water. In addition, continuous monitoring are highly recommended for the population before consumption of this domestic water to ensure maximum safety and a healthy living for all. It will be worthwhile to carry out further studies to determine the presence of other species of Enterobacteriacea in the study area.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Adesakin Taiwo: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Abayomi Oyewale: Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Precious Ahmed, Niima Abubakar, and Balkisu Barje: Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data.

Ndagi Mohammed, Umaru Bayero: Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data.

Adedeji Adwuo: Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

References

- Abednego M.M., Mbaruk A.S., John N.M., John M.M. Water-borne bacterial pathogens in surface waters of nairobi river and health implication to communities downstream athi river. World Appl. Sci. J. 2013;3(1) [Google Scholar]

- Abolude D.S., Edia-Asuke U.A., Aruta M., Ella E.E. Physicochemical and bacteriological quality of selected well water within Ahmadu Bello university community, Samaru, Zaria, Nigeria. Afr. J. Nat, Sci. 2016;19:1119-1104. [Google Scholar]

- Abulreesh H.H. Salmonellae in the environment. In: Annous B., Gurtler J.B., editors. Salmonella-Distribution, Adaptation, Control Measures and Molecular Technologies. InTech; 2012. pp. 19–50. [Google Scholar]

- Adah P.D., Abok G. Challenges of urban water management in Nigeria: the way forward. J. Env. Sci. Res. Manag. 2013;5(1):11–121. [Google Scholar]

- Adejuwon J.O., Mbuk C.J. Biological and physiochemical properties of shallow wells in Ikorodu town, Lagos, Nigeria. J. Geol. Min. Res. 2011;3:161–168. [Google Scholar]

- Adetunde L.A., Glover R.L.K. Evaluation of bacteriological quality of drinking water used by selected secondary schools in Navrongo in Kassena- Nankana district of upper east region of Ghana. Prime J. Microbiol. Res. 2011;1:47–51. [Google Scholar]

- Agunwamba J.C. second ed. Immaculate Publications Limited; Enugu: 2000. Water Engineering Systems; pp. 33–139. [Google Scholar]

- American Public Health Association (APHA) 2001. Standard Methods for Examination of 560 Water American Public Health Association (APHA), Standard Methods for Examination of Water, Washington, D.C. [Google Scholar]

- Anyanwu C.U., Okoli E.N. Evaluation of the bacteriological and physicochemical 674 quality of water supplies in Nsukka, Southeast, Nigeria. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2012;11(48):10868–10873. [Google Scholar]

- Aniyikaiya T.E., Oluseyi T., Odiyo J.O., Edokpayi J.N. Physico-chemical analysis of wastewater discharge from selected paint industries in Lagos, Nigeria. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 2019;16(7):1235. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16071235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong J.L., Calomiris J.J., Seidler R.J. Selection of antibiotic-resistant standard plate count bacteria during water treatment. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1982;44:308–316. doi: 10.1128/aem.44.2.308-316.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrell R.A., Hunter P.R., Nichols G. Community Diseases and Public Health; 2000. Microbiological standards for water and their relationship to health risk; pp. 8–13. 3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bello O.O., Osho A., Bankole S.A., Bello T.K. Bacteriological and physicochemical analyzes of borehole and well water sources in ijebu-ode, south western Nigeria. Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biological Research. 2013;8(2):18–25. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt L.R., Lacoul H.D., Lekhak H., Jha P.K. Physicochemical characteristics and phytoplankton of taudaha lake, kathmandu. Pollut. Res. 1999;18(4):353–358. [Google Scholar]

- Bibi S., Khan R.L., Nazir R. Heavy metals in drinking water of lakki marwat district, KPK, Pakistan. World Appl. Sci. J. 2016;34(1):15–19. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd C.E. Ine. Oplika; Alabama: 1981. Water Quality in Warm Water Fishponds. Auburn University, 359 Craftmaster Printers. [Google Scholar]

- Brady K.B.C. Natural groundwater quality from unmined areas as a mine drainage quality prediction tool. In: Brady K.B.C., Smith M.W., Schueck J., editors. Coal Mine Drainage Prediction and Pollution Prevention in Pennsylvania. PA DEP; Harrisburg, PA: 1998. pp. 10.1–10.11. [Google Scholar]

- Braide S.A., Izonfuo W.A.L., Adiukwu P.U., Chindah A.C., Obunwo C.C. Water quality of Miniweja stream, a swamp forest stream receiving non-point source waste discharges in Eastern Niger Delta, Nigeria. Scientia Africana. 2004;3:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Cabral J.P.S. Water microbiology. Bacterial pathogens and water. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 2010;7(10):3657–3703. doi: 10.3390/ijerph7103657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhameja S.K. Kataria and Sons Pub; 2012. Environmental Engineering and Management S.K; pp. 51–218. [Google Scholar]

- Donalson W.E. Trace element toxicity. In: Hodgson E., Guthrie F.E., editors. Introduction to Biochemical Toxicology. Elsevier; New York: 1980. pp. 330–340. [Google Scholar]

- Doughari J.H., Elmahmood A.M., Manzara S. Studies on the antibacterial activity of root extracts of Carica papaya L. Afr. J. Microbiol. Res. 2007:37–41. [Google Scholar]

- Dufour A., Snozzi M., Koster W., Bartram J., Ronchi E. Assessing microbial safety of drinking water improving approaches and methods. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2003;88:1065–1165. [Google Scholar]

- Ekhaise F.O., Anyansi C.C. Influence of brewery effluent discharge on the Microbiological and physicochemical quality of Ikpoba River, Nigeria. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2005;4(10):1062–1065. [Google Scholar]

- Esharegoma O.S., Awujo N.C., Jonathan I., Nkonye-asua I.P. Microbiological and physicochemical analysis of orogodo river, agbor, delta state, Nigeria. International Journal of Ecological Science and Environmental Engineering. 2018;5(2):34–42. [Google Scholar]

- Ezeribe A.I., Oshieke K.C., Jauro A. Physicochemical properties of well water 643 samples from some villages in Nigeria with cases of stained and mottled teeth. Sci. World J. 2012;1:7. [Google Scholar]

- Ford T.E. Microbiological safety of drinking water. United States and global perspectives. Environ. Health Perspect. 1999;107(1):191–206. doi: 10.1289/ehp.99107s1191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franciska M.S., Marcel D., Rinald L.H. Escherichia coli 0157: H7 in drinking water from private supplies. Journal of Netherlands Water Resource. 2005;39:4485–4493. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2005.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hems J.D. US Geological Survey Water Supply; 1985. Study and Interpretation of Chemical Characteristics of Natural Waters; pp. pp111–270. Paper 2254 http://www.ene.gov.on.ca/stdprodconsume/groups/lr/@ene/@resources/docu-ments/resource/std01-079707.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Ikhile C.I. Water chemistry of some streams in tropical rainforest area of edo state, Nigeria. In: Ibitoye A. Scientific., editor. Environmental Issues in Population, Environment and Sustainable Development in Nigeria. Department of Geography and Regional Planning, University of Ado-Ekiti Research Group; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ikomi R.B., Iloba K.I., Ekure M.A. The physical and chemical hydrology of River Adofi at utagba-uno, delta state, Nigeria. Zoologica. 2003;2(2):84–95. [Google Scholar]

- Jamielson R., Gordon R., Joy D., Lee H. Assessing Microbial Pollution of rural surface waters: a review of current watershed scale modeling approaches. Agric. Water Manag. 2004;70:1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Jean J.S. Outbreak of enteroviruses and ground water contamination in Taiwan: concept of biomedical hydrogeology. Hydrogeol. J. 1999;7:339–340. [Google Scholar]

- Jean J.S., Guo H.R., Chen S.H., Liu C.C., Chang W.T., Yang Y.J., Huang M.C. The association between rainfall rate and occurrence of an enterovirus epidemic due to a contaminated well. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2006;101:1224–1231. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2006.03025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan N., Hussain S.T., Saboor A. Physiochemical investigation of the drinking water sources from mardan, khyber pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. Int. J. Phys. Sci. 2013;8(33):1661–1671. [Google Scholar]

- Kidu M., Abraha G., Hadera A., Yirgaalem W. Assessment of physico-chemical parameters of tsaeda agam river in mekelle city, tigray, Ethiopia. Bull. Chem. Soc. Ethiop. 2015;29(3):377. [Google Scholar]

- Kolawole O.M., Alamu F.B., Olayemi A.B., Adetitun D.O. Bacteriological analysis and effects of water consumption on the hematological parameters in rats. International Journal of Plant, Animal and Environmental Sciences. 2013;3(2):125–131. [Google Scholar]

- LeChevallier M.W., Shaw N.E., Kaplan L.A., Bott T.L. Development of a rapid assimilable organic carbon method for water. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1993;pp59:1526–1531. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.5.1526-1531.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeClerc H., Mizon F. Eaux d'alimentationet bacte ries resistantes aux antibiotiques. Incidences sur les normes. Revision Epidemiological and Medical Society. Sante Publique. 1978;26:137–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marczenko Z. 2nd 563. E. Horwood; Chichester: 1986. Separation and Spectrophotometric Determination of Elements; p. 678. [Google Scholar]

- Mauskar J.M. 2008. Control of Urban Pollution Series: CUPS/69/2008 Performance of Sewage Treatment Plants-Coliform Reduction.www.cpcb.mc.in/divisionsofheadoffice/pams/pstp-coliform.pd [Google Scholar]

- Miettinen I.T., Vartiainen T., Martikainen P.J. Contamination of drinking water. Nature. 1996;381:654–655. doi: 10.1038/381654b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milkiyas T., Mulugeta K., Bayeh A. Bacteriological and physic-chemical quality of drinking water and hygiene-sanitation practices of the consumers in Bahir Dar city, Ethiopia. Ethiopia Journal of Health Science. 2011;22:19–26. doi: 10.4314/ejhs.v21i1.69040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyle J.B. Some indices of lake productivity. Trans. Am. Fish. Soc. 2009;76:322–334. [Google Scholar]

- Murray G.E., Tobin R.S., Junkins B., Kushner D.J. Effect of chlorination on antibiotic resistance profiles of sewage-related bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1984;48:73–77. doi: 10.1128/aem.48.1.73-77.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) 2009. Annual Abstract of Statistics, Federal Republic of Nigeria. [Google Scholar]

- National Population Commission (NPC) National Population Commission; Abuja: 1991. Population Census of the Federal Republic 557 of Nigeria: Analytical Report at the National Level. [Google Scholar]

- Nduka J.K., Orish E.O. Some physicochemical parameters of potable water supply in Warri, Niger Delta area of Nigeria. Sci. Res. Essays. 2008;3(11):547–551. [Google Scholar]

- Nwachukwu C.I., Otokunefor T.V. Bacteriological quality of drinking water supplies in the University of Port Harcourt, Nigeria. Nigeria Journal of Microbiology. 2006;20(3):1383–1388. [Google Scholar]

- Ogbonna C.E., Njoku H.O., Onyeagba R.A., Nwaugo V.O. Effects of seepage from drilling burrow pit wastes on orashi river, egbema, rivers state, Nigeria. Nigerian Journal of Microbiology. 2010;24(1):193–200. [Google Scholar]

- Oguntoke O., Abodemi O.J., Bankole A.M. Association of waterborne diseases morbidity pattern and water quality in parts of Ibadan City, Nigeria. Tanzan. J. Health Res. 2009;11(4):189–195. doi: 10.4314/thrb.v11i4.50174. ISSN: 182-6404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okonko I.O., Adejoye O.D., Ogunnusi T.A., Fajobi E.A., Shittu O.B. Microbiological and physicochemical analysis of different water samples used for domestic purposes in Abeokuta and Ojota, Lagos State, Nigeria. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2008;7(5):617–621. [Google Scholar]

- Oladimeji A.A., Kolo R.J. Water quality and some nutrient levels in Shiroro Lake Niger State. Nigeria. J. Aquat. Sci. 2004;19(2):99. [Google Scholar]

- Olajire A.A., Imeppeoria F.E. Water quality assessment of Osun River: studies on inorganic nutrients. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2001;69:17–28. doi: 10.1023/a:1010796410829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olobaniyi S.B., Owoyemi F.B. Quality of groundwater in the deltaic plain sand aquifer of warri and environs of delta state, Nigeria: water resource. Journal of the Nigeria, Association of Hydrogeologist. 2004;15:38–45. [Google Scholar]

- Olobaniyi S.B., Owoyemi F.B. Characterization by factor analysis of the chemical faces of groundwater in the deltaic plain sands aquifer of warri, western Niger delta, Nigeria. African Journal of Science and Technology (AJST), Science and Engineering Series. 2006;7(1):73–81. [Google Scholar]

- Oparaocha E.T., Iroegbu O.C., Obi R.K. Assessment of quality of drinking water sources in the federal university of technology, owerri, imo state, Nigeria. Journal of Applied Bioscience. 2010;32:1964–1976. [Google Scholar]

- Otobo A.J.T. University of Port Harcourt; 1995. The Ecology and Fishery of Them Pygmy Herring Sierratherissa Leonensis (Thys Van Dan Audenaerde, 1969) (Clupeidae) in the Nun River and Taylor 611 Creek of the Niger Delta; p. 221. Ph.D Thesis. [Google Scholar]

- Ouma S.O., Ngeranwa J.N., Juma K.K., Mburu D.N. Seasonal variation of the physicochemical and bacteriological quality of water from five rural catchment areas of lake victoria basin in Kenya. Journal of Environmental Analytical Chemistry. 2016;3:2–7. [Google Scholar]

- Pawari M.J., Gawande S. Ground water pollution and its consequence. International 536 Journal of Engineering Research and General Science. 2015;3(4):773–776. [Google Scholar]

- Polo F., Figueras M.J., Inza I., Sala J., Fleisher J.M., Guarro J. Prevalence of Salmonella serotypes in environmental waters and their relationships with indicator organisms. Antonie Leeuwenhoek. 1999;75(4):285–292. doi: 10.1023/a:1001817305779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prati L., Pavanello R., Pesarin F. Assessment of surface water quality by a single index of pollution. Water Res. 1971;5:741. [Google Scholar]

- Premlata V. Multivariant analysis of drinking water quality parameters of Lake Pichhola in Udaipur, India. Biological Forum. Int. J. 2009;1(2):97–102. [Google Scholar]

- Rachna B., Disha J. Water quality assessment of lake water: a review. Sustain. Water Resour. Manag. 2016;2:161–173. [Google Scholar]

- Raji M.I.O., Ibrahim Y.K.E. Prevalence of water-borne infections in North Western Nigeria: a retrospective study. J. Publ. Health Epidemiol. 2011;3(8) 382-512 385. [Google Scholar]

- Reimann C., Bjorvatn K., Frengstad B., Melaku Z., Teklehaimanot R., Siewers U. Drinking water quality in the Ethiopian section of the east African rift valley I-data and health aspects. Science and Total Environmental Journal. 2003;311:65–80. doi: 10.1016/S0048-9697(03)00137-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuel P.O., Adakole J.A., Suleiman B. Temporal spatial physico-chemical parameters of river galma, Zaria, Kaduna state, Nigeria. Research Environment. 2015;5(4):110–123. [Google Scholar]

- Shittu O.B., Olaitan J.O., Amusa T.S. Physico-chemical and bacteriological analyses of water used for drinking and swimming purposes in Abeokuta, Nigeria. Afr. J. Biomed. Res. 2008;11:285–290. [Google Scholar]

- Sojobi A.O., Owamah H.I., Dahunsi S.O. Comparative study of household water treatment in a rural community in Kwara State, Nigeria. Nigeria Journal of Technology. 2014;33(1):134–140. [Google Scholar]

- Standard Organization of Nigeria (SON) 2007. Nigerian Standard for Drinking Water Quality, SON, Abuja. Nigeria. [Google Scholar]

- Swanta A.A., Sonnie O., Mathias C. Domestic water quality assessment: microalgal and cyanobacterial contamination of stored water in plastic tanks of stored water in plastic tanks in Zaria, Nigeria. Eur. J. Sci. Res. 2013;110(4):501–510. [Google Scholar]

- Taha G.M., Younis M. Chemical and bacteriological evaluation of drinking water: a study case in wadi el saaida hamlets in aswan governorate, upper Egypt. Journal of International Applied Science. 2009;4:309–377. [Google Scholar]

- Taiwo A.M., Olujimi O.O., Bamgbose O., Arowolo T.A. In: Surface Water Quality Monitoring in Nigeria: Situational Analysis and Future Management Strategy, Water Quality Monitoring and Assessment. Voudoinis Dr., editor. InTech; 2012. Available from: http://www.intechopen-com/books/waterquailty-monitoring-and-assessment/surface-water-quailty-monitoring-in-nigeria-situation-analysis-and-futuremanagement-strategy. [Google Scholar]

- Tenagne A.W. Cornell University; New York, USA: 2009. The Impact of Urban Storm Water Runoff and Domestic Waste Effluent on Water Quality of Lake Tana and Local Groundwater Near the City of Bahir Dar, Ethiopia. M.Sc. thesis. [Google Scholar]

- Tyokumbur E.T., Okorie T.G., Ugumba O.A. Limnological assessment of the effects of effluents on macroinvertebrate fauna in Awba Stream and Reservoir, Ibadan, Nigeria. Zoologica. 2002;1(2):59–69. [Google Scholar]

- Ufodike E.B.C., Kwanasie A.S., Chude L.A. On-set of rain and its destabilizing effect on aquatic and physico-chemical parameters. J. Aquat. Sci. 2001;16(2):91–94. [Google Scholar]