Abstract

The Bangkok Metropolitan Area is an example of urban sprawl that has undergone rapid expansion and major changes in urban composition and building configuration. This city is now faced with the urban heat island phenomenon. Initial observations of land surface temperature (LST) in recent years have indicated that LST has tended to increase in both urban and suburban areas. The purposes of this study were to: (1) assess different land cover types and combinations of land cover composition along an LST gradient, and (2) investigate effect of building configuration types on the LST in densely urban areas. We analyzed the urban composition variation of 4,960 land cover samples using a 500 m × 500 m grid and configuration metrics in spatial patterns from Landsat 8 data and a high-resolution database of buildings obtained from GIS data of the Bangkok Metropolitan Area. The results indicated that the fraction of land cover composition was strongly related to LST. Our results suggested that LST can be effectively mitigated by using below green (shrubs, grasses, and yards), above green (trees, orchards, mangroves, and perennial plants) and water land cover. By increasing tree canopy to around 20%, water body to around 30% or green yard/shrub to around 40% of the built-up areas, it is possible to reduce LST significantly. Urban configurations (edge density, patch density, large patch, mean patch size, building height, compactness of building, building type, and building use) affecting on LST were studied. Increased edge density, patch density of buildings, and building height caused reductions in LST. Distribution of LST patterns can be significantly related with urban composition or land configuration features. The results of this study can increase understanding of the interaction between urban composition and configuration metrics. Moreover, our findings may be useful in the mitigation of the impact of LST in urban-sprawl cities.

Keywords: Bangkok, Land surface temperature (LST), Urban composition, Urban configuration, Urban heat island, Materials science, Environmental science, Earth sciences

Bangkok; Land surface temperature (LST); Urban composition; Urban configuration; Urban Heat Island; Materials Science; Environmental Science; Earth Sciences.

1. Introduction

Rapid urbanization causes land cover change, surface modification, and changes in radio solar reflectance, thermal emissivity, and heat capacity in built materials, subsequently leading to temperature increases in megacities such as Bangkok, Thailand (Srivanit and Kazunori, 2011). The difference in temperature between urban and suburban zones is called the urban heat island phenomenon (UHI), which is related directly to land use and indirectly to urban energy consumption (EPA, 2009). The land cover changes caused by urban expansion considerably affect the urban morphology, structure, and function of land cover composition and configuration. The surface alterations caused by urbanization include, for example, replacing bare soil and vegetation surfaces with impervious surfaces such as asphalt, concrete, and cement, or changing the urban morphology such as by constructing built-up areas of diverse heights and densities (Zhou et al., 2011). These alterations change urban surface characteristics such as heat capacity, albedo, and thermal conductivity over the land surface, which lead to warmer temperatures than in the surrounding rural areas (Srivanit and Kazunori, 2012). Researchers have investigated the aspects of UHI in several big cities, including its causes, impacts, and complexity (Mirzaei and Haghighat, 2010; Imhoff et al., 2010). Generally, UHI tends to increase heatwave intensities as was observed in Chicago, USA in 1995 (Sailor and Lu, 2004), Delhi, India in 2014 (Sharma and Joshi, 2014), Colombo, Sri Lanka in 2013 (Senanayake et al., 2013), and Shanghai and Beijing, China in 2014 (Chen et al., 2014). The basic characteristics of UHI can be categorized into land surface temperature (LST) and air temperatures (EPA, 2009). While several researchers have revealed that LST had a close relationship and similar spatial patterns with ambient air temperature (Ben-Dor and Saaroni, 1997; Nichol, 1994; Nichol et al., 2009; Schwarz et al., 2012), there are some cities in which no consistent relationship has been identified between the two (Arnfield, 2003). Generally, the difference in air temperature is stronger and shows greatest spatial variation at night, while in contrast, the difference in LST usually occurs during the daytime (Arnfield, 2003; Frey et al., 2010; Nichol et al., 2009; Zhou et al., 2011; EPA, 2009). Satellite image data has regularly been used to evaluate LST, especially at vast landscape scales. LST data have been recorded based on the radiative energy emitted from the ground surface, including building roofs, paved surfaces, vegetation, bare ground, and water bodies (Arnfield, 2003; Voogt and Oke, 2003; Chen et al., 2014).

Urban composition refers to the abundance and variety of land cover features without considering their spatial arrangement, whereas urban configuration refers to the spatial arrangement or distribution of land cover features (Zhou et al., 2011). The influence of LST directly varied with the alteration of the surface material properties of land cover. Land cover patterns may do so through their effects on the transfers and flows of energy and materials from an urban perspective (Arnfield, 2003; Gustafson, 1998; Forman, 1995; Turner, 2005; Zhou et al., 2011). Previous research primarily studied the effects of vegetation abundance on LST, using satellite image data to evaluate vegetation density and to assess the LST. It showed that land covered by vegetation significantly affected LST in an urban area. Moreover, the size and shape of vegetation patches also affected LST (Buyantuyev and Wu, 2010; Senanayake et al., 2013; Wu et al., 2014). Existing studies on the influence of the composition and configuration of the urban landscape in minimizing UHI effects have not been sufficient (Zhou et al., 2017). Previous studies focused on the relationship between LST and urban composition and configuration by investigating spatial patterns in several LST zones or zones with different types of land use; for example, Chen et al. (2014) proposed that variables of land cover may play an important role in the spatial patterns of LST. Nevertheless, some studies explored the quantitative relationship between LST and the configuration of different types of land cover features, particularly after adjusting for the effects of land cover composition (Zhou et al., 2011). However, there has been no study published on the magnitude of land cover or the combination of composition and building configuration type to reduce LST in urban areas.

The current study examined the effects of the magnitude of urban composition and urban configuration patterns on LST in the Bangkok Metropolitan Area, Thailand. The purposes of this study were to: (1) assess different land cover types and combinations of land cover composition along an LST gradient, and (2) investigate effect of building configuration types on LST in densely urban areas. The results of this study can provide understanding of the interaction between urban compositions and configuration patterns for a megacity such as Bangkok. Moreover, our findings may be benefit in the mitigation of the impact of LST in urban-sprawl cities.

2. Methods

2.1. Study site and conceptual framework

Bangkok is a large metropolitan city in Southeast Asia (1,576 km2). It is the capital of Thailand and has a population of over 10 million people. The climate is tropical with the average ambient air temperature in Bangkok being between 26 and 31 °C. The Bangkok Metropolitan Area can be classified into 5 zones according to characteristics of land use: conservation zone, economic zone, residence zone, western suburbs zone, and eastern suburbs zone (Figure 1 (a)) (Department of Provincial Administration, 2019). This study was conducted using the land cover classification and LST over all 50 districts of Bangkok during summer. The land cover was classified into 5 categories: built-up (buildings, impervious surfaces, pavement, and other constructions), bare soil (soil, and land left fallow without vegetation cover), below green (herbs, shrubs, grasses, yards, and paddy fields), above green (trees, orchards, mangroves, and perennial plants), and water bodies (canals, rivers, ponds, and shrimp or fish farms) (Liu. et al., 2020). The results of the land cover and LST features are summarized in Figure 1 (b). The land cover recorded for the study area consisted of 45.0% built-up surface, 17.1% below green, 15.8% bare soil, above green 13.8%, and 8.3% water bodies. The LST range was 34–45 °C.

Figure 1.

Map of Bangkok, Thailand: land use zone (A), land cover and LST (B), and example of data layer over a sample grid of 500 m × 500 m (C).

The conceptual framework is shown in Figure 2. Input data came from Landsat 8 OLI satellite and shapefile data (building database). LSTs were calculated from the input data. The relationships between the land composition (built-up percentage, bare soil percentage, below green percentage, above green percentage, and water body percentage) and land configuration (edge density of buildings (ED), patch density of buildings (PD), large patch of building (LP), mean patch size (PS), building height (BH), compactness of building (CB), building type (BT), and building use (BU) were investigated. The outcomes of this study will indicate the appropriate land composition and land configuration to manage LST in urban-sprawl city.

Figure 2.

Conceptual framework of this study.

2.2. Effects of land cover composition and building configuration features on LST

2.2.1. Land cover composition

For this research, the images taken for the land cover composition was derived from Landsat 8 OLI (Operational Land Imager) imagery taken in 2016, at medium resolution (30 m). Land cover recorded from the visible band was classified using a supervised classification method (minimum-distance algorithm). Five categories of land cover composition features were identified: (1) built-up surfaces (B); (2) bare soil surfaces (BS); (3) below green (BG); (4) above green (AG); and (5) water body (W). All land cover composition was checked for accuracy before being analyzed using Eq. (1).

| (1) |

All accuracy of land cover data was more than 96.00% while, producer's accuracy was >94.00% and the user's accuracy was >90.57 %. LST data were validated by comparing calculated LST and measured LST in field. Infrared temperature guns Mode 4470 Control Company were used to measure the surface temperature in the field at approximately 50 points per each land cover (B, BS, BG, AG and W). The effects of the proportions of different land covers on changes in LST were investigated using 5 ratios: built-up to bare soil (B:BS), built-up to below green (B:BG), built-up to above green (B:AG), and built-up to water body (B:W). The percentage of land cover in each category was varied from 10% to 90%. Grid samples (500 m × 500 m) were selected in the specified proportions shown in Table 1. The LSTs for each proportion were calculated. One-way ANOVA was used to examine the differences in LST between groups of land cover composition (p value = 0.05).

Table 1.

Details and description of urban composition variables.

| Description of urban composition (a) | Group | Composition ratio (%) (b) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B:BS | B:BG | B:AG | B:W | ||

|

1. Built-up (B) Percentage of built-up area (impervious surfaces with a cover of buildings, other constructions, and pavement) 2. Bare soil (BS) Percentage of bare soil (pervious surfaces that have a cover of soil, and land left fallow without vegetation cover). 3. Below green (BG) Percentage of below green (herbs, shrubs, grasses, yards, and paddy fields) 4. Above green (AG) Percentage of above green (trees, orchards, mangroves, and perennial plants) 5. Water body (W) Percentage of water bodies (canals, rivers, ponds, and shrimp or fish farms) |

1 | 90 : 10 | 90 : 10 | 90 : 10 | 90 : 10 |

| 2 | 80 : 20 | 80 : 20 | 80 : 20 | 80 : 20 | |

| 3 | 70 : 30 | 70 : 30 | 70 : 30 | 70 : 30 | |

| 4 | 60 : 40 | 60 : 40 | 60 : 40 | 60 : 40 | |

| 5 | 50 : 50 | 50 : 50 | 50 : 50 | 50 : 50 | |

| 6 | 40 : 60 | 40 : 60 | 40 : 60 | 40 : 60 | |

| 7 | 30 : 70 | 30 : 70 | 30 : 70 | 30 : 70 | |

| 8 | 20 : 80 | 20 : 80 | 20 : 80 | 20 : 80 | |

| 9 | 90 : 10 | 90 : 10 | 90 : 10 | 90 : 10 | |

|

Fix Built-up |

|

|

|

|

|

| Another composition | BS | BG | AG | W | |

2.2.2. Building configuration

Building configuration was divided into 8 configuration features: edge density of buildings (ED) (the total length of all building patches per square meter), patch density of buildings (PD) (the quantity of building plots per square meter), large patch of building (LP) (computed at class interval, equal to the largest building area within a grid sample (500 m × 500 m) divided by the grid area, multiplied by 100) according to Zhou et al. (2011), building height (BH) and size (SB) (calculated as the base height and stories of a building), building use (BU) (classified as one of four categories: residential, commercial, industrial, and mixed use), building type (BT) (house, townhouse, row-building (2–3 floors), row-room building (1 floor), office building, apartment, and condominium), and compactness of building (CB) (configuration forms of building geometry were classified from a land plot pattern within a grid sample as fragment blocks, linear blocks, and square blocks). Figure 3 provides details and descriptions of the urban configurations. The overall accuracy of the building categorization was >80 %. In addition, we conducted field investigations. One-way ANOVA was used for statistical analysis with p value = 0.05.

Figure 3.

Details and descriptions of urban configuration features.

2.3. Images and image pre-processing for LST

In this research, we used Landsat 8 OLI images from path 129 row 50 and path 129 row 51 in 2016. The data consisted of the thermal band (10.60–11.19 μm) at 100 m resolution to measure urban surface temperatures. The Landsat 8 OLI images were downloaded from the website of the United States Geological Survey (USGS; http://glovis.usgs.gov/). The images were chosen carefully to cover summer periods and were preferably cloud-free (cloud cover 0%). The LST was obtained from the thermal infrared sensor band. LST data were computed using the USGS equations (USGS, 2016). The digital image data were converted to radiance values, as shown in Eq. (2), which were subsequently converted to temperature, as shown in Eqs. (3) and (4).

Convert digital number (DN) to radiance value:

| Lλ = ML QCal + AL | (2) |

where Lλ = wave radiation value.

ML = radiance multi-band (10) = 3.3420E-04

QCal = quantized and calibrated standard product pixel value (DN)

AL = radiance add band (10) = 0.10000

1. Convert radiance value to temperature value:

| TB = K2 / ln ((K1/L) + 1) | (3) |

where TB = Kelvin surface temperature

K1 = 774.89

K2 = 1321.08

2. Kelvin surface temperature to Celsius temperature:

| TC = TK - 273 | (4) |

The LST was classified during the dry season in 2016 when the temperature was highest. A temperature class interval displayed in red was used to indicate areas where the highest LST had accumulated, while the lowest temperature was shown using blue to indicate water bodies and rivers.

2.4. Statistical analysis

We explored land composition and configuration from land cover and building features using statistical and spatial analysis (Zonal statistical model in GIS program). In order to examine the relationships associated with spatial variation of LST, land cover and building configuration factors, the following explanatory variation were selected: (1) B, (2) BG, (3) AG, and (4) W for land cover and five building configurations of (1) ED, (2) PD, (3) LP, (4) PS, and (5) BH in each grid (500 m × 500 m). A linear regression was developed with statistical significance set at the 95% confidence limit to predict the variation in LST. Then, One-way ANOVA was used to determine the significant difference between LST and land cover/building configurations with P value = 0.05. To examine LST differences in the proportions of four land covers categories (B:BS, B:BG, B:AG, and B:W), the Duncan multiple range test (DMRT) was performed as a post hoc test. The significant level (P value) was 0.05.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. LST validation

The results of LST interpretation from the satellite images were validated by comparing them with the results from field survey. Infrared temperature guns were used to measure the surface temperature in the field at approximately 50 points per land cover category. Ground surface temperature was measured between 10:00 am and 1:00 pm, which was the approximate time of data record satellites. The relationship between LST from the satellite images and ground measurement is represented in Figure 4. The R2 values in built-up (A), bare soil (B), above green (C), below green (D), and water (E) were 0.948, 0.965, 0.974, 0.954 and 0.962, respectively. The R2 closed to 1 implied the close relationship between LST calculated from satellite data and LST measured in the field.

Figure 4.

Relationships between LST from satellite images and ground measurement; built-up (A), bare soil (B), above green (C), below green (D), and water (E).

3.2. Pattern of land surface temperature in Bangkok Metropolitan Area

The spatial pattern of LST in Bangkok (Figure 5) indicated that the high-LST hot spots (>40 °C) were distributed in the downtown, northern, and eastern parts of Bangkok. Our field survey found that land was used for commercial buildings downtown, for an airport and residential areas in the north, and for agriculture in the east. The land cover and configurations in these three areas were also investigated. Downtown, the land cover was classified as built-up and the configurations were high-rise commercial and residential buildings. Some areas were crowded with old heritage buildings; thus, those areas had been classified as conservation areas. The land cover was also classified as built-up in the northern part of Bangkok, but the configuration was largely concrete pavement and low-rise residential buildings. In contrast, the land cover on the eastern side was mostly bare soil. In the summer, the agricultural lands were prepared for cropping in the rainy season. The configurations in this area were single houses, townhouses, and low-rise buildings. This observation was similar to the results reported for Akure city in southwest Nigeria and in Delhi, the capital city of India (Balogun and Daramola, 2019; Sharma and Joshi, 2014).

Figure 5.

Pattern of land surface temperatures in different areas of Bangkok.

3.3. Effect of land cover composition on LST in Bangkok Metropolitan Area

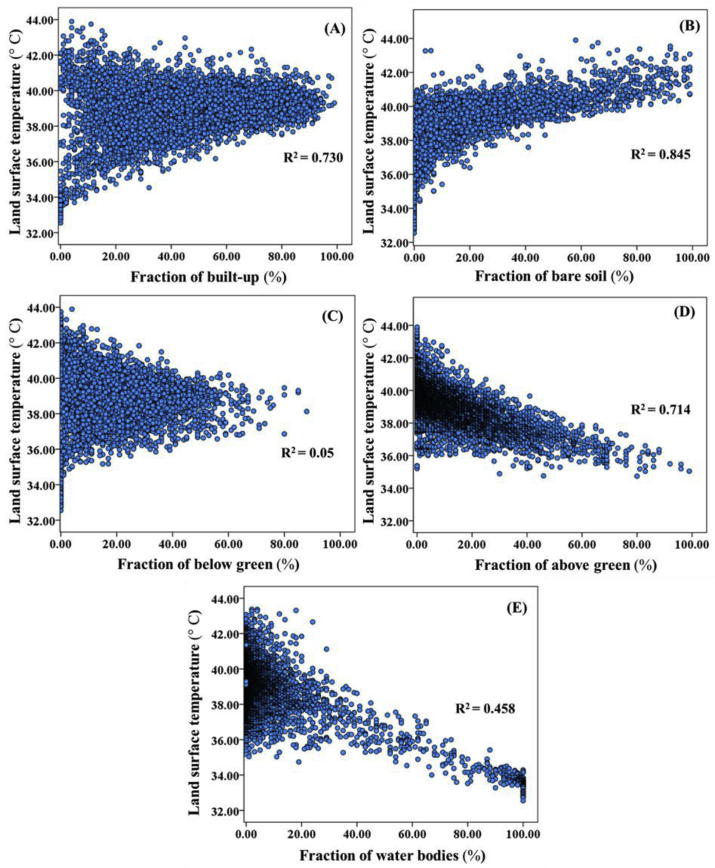

The relationships between each type of land cover and LST were investigated (Figure 6). The ratios of built-up and bare soil had positive relationship trends with LST, with the R2 value of built-up and LST and of bare soil and LST being 0.730 and 0.845, respectively. This suggested that the higher the proportion of built-up and bare soil in the area, the higher the LST. However, the ratios of above green and water body indicated a negative relationship with LST, with the R2 values of water body and above green at 0.458, and 0.714, respectively. The greater the ratios of above green and water body cover in an area, the lower the LST. The impact of urban composition on urban LST has been widely reported (Buyantuyev and Wu, 2010; Liang and Weng, 2008; Liu and Weng, 2009; Wu et al., 2008; Zhou et al., 2011, 2017). Our results corresponded with the results from previous study on the land cover composition influence on the LST of Bangkok (Srivanit and Kazunori, 2011). There are many factors affecting LST, for example the type of land cover, biophysical and meteorological factors, building materials, and surface color (Liu et al., 2017), but the type of land cover may have the most significant effect.

Figure 6.

Relationships between LST and land cover types: built-up (A), bare soil (B), below green (C), above green (D), and water bodies (E).

To manage the effect of LST in urban areas, suitable ratios of land cover should be considered in urban planning for new city developments. The ratios of built-up and other land covers (bare soil, above green, below green, and water body) were varied, and the LST for each ratio was investigated. The results are shown in Figure 7, which indicates there was a tendency of LST to increase when built-up cover in the grid area was changed into other types of land cover. Table 2 presents the average LST values for each ratio of land cover combination. Statistical analysis indicated significant differences (95% confidence level) of average LST in B:BS, B:BG, B:AG, and B:W. Replacing part of a 100% built-up grid with 20% of above green, 30 % of water body or 40 % of below green tended to lower LST, whereas substituting bare soil into the built-up grid did not significantly decrease LST.

Figure 7.

LST for different ratios between built-up and other land cover types: bare soil (A), above green (B), below green (C), and water bodies (D), hanging bare is LST maximum (top) and minimum (bottom), boxes up is 75th percentile, low fence is 25th percentile, and line in middle of box is 50th percentile, means with different letters (A, B, C, D, E or F) indicate significant differences (P value <0.05).

Table 2.

Variation of average LST in each ratio of land cover combination.

| Ratio % | Average LST (° C) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Built-up: Bare soil (B:BS) |

Built-up: Below green (B:BG) |

Built-up: Above green (B:AG) |

Built-up: Water body (B: W) |

|||||

| Mean ± Std.D. | Increase | Mean ± Std.D. | Decrease | Mean ± Std.D. | Decrease | Mean ± Std.D. | Decrease | |

| 100:00 | 39.14 ± 1.176 | - | 39.14 ± 1.176 | - | 39.14 ± 1.176 | - | 39.14 ± 1.176 | - |

| 90: 10 | 39.62 ± 0.355 | 0.48 | 39.00 ± 0.237 | -0.14 | 39.55 ± 0.394 | 0.41 | 38.45 ± 0.257 | -0.69 |

| 80: 20 | 39.84 ± 0.519 | 0.22 | 39.11 ± 0.299 | 0.11 | 38.69 ± 0.154 | -0.87 | 38.34 ± 0.665 | -0.11 |

| 70: 30 | 40.01 ± 0.542 | 0.17 | 39.18 ± 0.557 | 0.07 | 38.36 ± 0.148 | -0.32 | 37.63 ± 0.509 | -0.71 |

| 60: 40 | 40.41 ± 0.661 | 0.40 | 38.61 ± 0.472 | -0.57 | 37.79 ± 0.203 | -0.57 | 36.63 ± 0.342 | -1.00 |

| 50: 50 | 40.78 ± 0.534 | 0.37 | 38.62 ± 0.551 | 0.02 | 37.35 ± 0.141 | -0.44 | 36.29 ± 0.377 | -0.34 |

| 40: 60 | 41.02 ± 0.566 | 0.24 | 38.07 ± 0.345 | -0.56 | 37.33 ± 0.289 | -0.02 | 35.69 ± 0.484 | -0.61 |

| 30: 70 | 41.30 ± 0.190 | 0.28 | 38.15 ± 0.559 | 0.08 | 36.87 ± 0.069 | -0.46 | 35.52 ± 0.220 | -0.16 |

| 20: 80 | 41.38 ± 0.621 | 0.08 | 37.77 ± 0.578 | -0.38 | 35.93 ± 0.347 | -0.94 | 34.73 ± 0.337 | -0.80 |

| 10: 90 | 41.61 ± 0.797 | 0.23 | 37.01 ± 0.766 | -0.76 | 35.56 ± 0.214 | -0.37 | 34.15 ± 0.345 | -0.58 |

Increasing bare soil cover can change the LST significantly and thus cause an accumulation of excess heat in urban areas (Figure 7 (A)). The average LST in a 500 m × 500 m grid increased by 0.5–0.7 °C with each 10% of bare soil substituted into a built-up area. Bare soil has lower thermal capacity and thermal conductivity than built-up. The thermal capacity of bare soil is 837–910 J/(kg-K), whereas that of built-up (concrete) is 960 J/(kg-K) (Dupont et al., 2014; Hens, 2016; Integrated Environmental Solutions, 2011; Jayalakshmy and Philip, 2010). Therefore, heat on soil surfaces was able to be highly reflected as LST, leading to the LST average of built-up surfaces increasing. Particularly in the dry season, the characteristics of bare soil in Bangkok were land that had been left fallow, showing continuous large dark patches.

This fallow soil had no agricultural activity on it and was also without vegetation cover. Bare soil features were characterized and the results indicated that a high LST was found around post-harvested paddy fields. The highest LST recorded was 44.27 °C, and the average LST of bare soil was 39.69 °C. This probably occurred due to the direct absorption of heat by the soil, where the dark organic matter (OM) present may have led to more intense electromagnetic energy absorption (Sayão et al., 2018). Generally, OM in the paddy fields of Thailand is dark brown to black. Soil that is high in organic matter is often dark in color and dark soil has a high heat capacity, resulting in higher absorbed and lower reflected radiation. It also may contribute to soil temperature rise (Anongrak, 2010).

Moreover, field investigation found that burning straw and weed cover during land preparation for rice cultivation may play an important role in emitting heat and contributing to the elevation of LST in these areas. Our results were supported by Hamoodi et al. (2017) who reported on bare soil surface albedo, which was also linked to LST surface properties. Similar results were found in Delhi (India) by Sharma and Joshi (2014), Bunyantuyev and Wu (2010). They found that the highest LST values were located in land covered by land left fallow during the summer season. The exposed bare soil, with low heat capacity heated up easily. This heating up of bare soil is further supported by the high amount of incoming solar radiation during the season. In contrast, Srivanit and Kazunori (2011) found that the intensive LST in Bangkok was stronger in the urban zone than on the east side where there was more agricultural zone. Their results indicated that LST had the strongest relationship with urban morphology. Built-up had the most release of heat from urban infrastructure. Our results were consistent with those from previous studies in showing that built-up composition and built-up morphology features considerably influenced the magnitude of LST in Bangkok.

The above green component can lead to mitigation of LST as this includes trees, orchards, mangroves, and perennial plants that are spatially distributed outside of Bangkok and also in some green areas in the downtown zone. Our results in Figure 7 (B) also indicated that the average LST in a 500 m × 500 m grid decreased by 0.6–0.8 °C with each 10% of above green substituted into a built-up area. Vegetation has higher thermal capacity and thermal conductivity of 1,300–2,000 J/(kg-K) (Dupont et al., 2014; Hens, 2016; Integrated Environmental Solutions, 2011; Jayalakshmy and Philip, 2010). Therefore, heat on the trees was able to be highly reflected, leading to reduced average LST values in built-up surface grids. The trees are strongly reflected Near infrared (NIR), the wavelength range 700–1,100 nm by cell structures in green leaves because absorption of NIR can harm the plant tissues by overheating (Gates, 1980; Senanayake et al., 2013). In addition, the density of vegetation can reduce the heat of built-up surfaces via the shade provided, and also enhance energy flow and exchange between trees and their surrounding areas (Zhou et al., 2017). Our results corresponded with previous studies, including one conducted in Western Australia in the central Perth metropolitan area by Hamoodi et al. (2017). Vegetation cover has diversity in its heat capacity values, which essentially depends on the moisture content of leaves.

The single below green area distributed around the outside of Bangkok was the least significantly related to LST, but replacing built-up with below green cover reduced the average LST in sample grids by 0.1–0.6 °C (Figure 7 (C)). In our survey, below green was found on green-roofed buildings comprising approximately 600 building features or 20% of the downtown area. Generally, below green had higher surface albedo than above green. The mean surface albedo (±standard deviation) of below green was 0.281 ± 0.009, while that of above green was 0.152 ± 0.002 (Rajabi and Abu-Hijleh, 2014). Finally, we found that LST tended to reduce rapidly with an increasing proportion of water bodies (Figure 7 (D)). Water bodies in Bangkok included rivers, canals, ponds, and fish or shrimp farms. The presence of 40% water body composition in a built-up grid was able to reduce the average LST by around 1 °C. EPA (2009) reported that water surfaces can absorb the most heat intensity and also reflect less from the surface to the canopy during daytime.

3.4. Land configuration feature of Bangkok Metropolitan Area

Figure 8 shows the building configuration of Bangkok LST; edge density (Figure 8 (A)), patch density (Figure 8 (B)), large patch (Figure 8 (C)), mean patch size (Figure 8 (D)), building height (Figure 8 (E)), compactness of building (Figure 8 (F)), building types (Figure 8 (G)), and building use (Figure 8 (H)). Bangkok has an urban-configuration sprawl in both the inner and middle zones. The city center area is dense residential buildings having different heights, consisting of houses, townhouses, row-building, row-rooms, apartments, and condominiums. The urban configuration has been expanded on the outskirts of the city, like other cities in developing countries. The physical characteristics of the city in this way have resulted in similar patterns of LST. Therefore, the inner-city and the middle-city areas of Bangkok were the most suitable for the study of configuration and structures because they are densely proportioned and cover the entire area. Sample grids in this area were randomly chosen to study the building detail.

Figure 8.

Spatial distribution of building configuration of Bangkok: edge density (A), patch density (B), large patch (C), mean patch size (D), building height (E), compactness of building (F), building type (G), and building use (H).

The effects of building configuration on LST in Bangkok were investigated. The 500 m × 500 m grids with >90% built-up cover in different building configurations were chosen for this study. The relationship between LST and edge density, patch density, large patch, building height, mean patch size in Bangkok are shown in Figure 9. In Figure 9, building height, edge density and patch density of buildings were significantly related to reduced LST, with R2 values of 0.635, 0.347, and 0.254, respectively. In contrast, the higher the patch size and large patch, the higher the LST. These were positively related with an R2 value of 0.848 and 0.244 in this study.

Figure 9.

Scatterplots between LST and edge density (A), patch density (B), large patch (C), building height (D) and mean patch size (E).

The reason that the building configuration features significantly affected LST was probably because the spatial arrangements may influence the flow of energy or energy exchange between different building features (Zhou et al., 2011, 2017). They also reported that LST decreases with an increase in both the patch and edge densities of buildings, while the largest patch density of buildings increased with LST. These results indicated the complex thermal condition patterns of urban morphology. Consequently, the height of buildings was one of the important factors influencing LST. The average LST decreased in the sample grids with increasing building height. Our field investigation found that the average height of a building in downtown Bangkok was around 37 m, which was similar to the spatial distribution of LST in the metropolitan area of Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, where the effect of heat islands was considered significantly related to >7 m building height (Voogt and Oke, 2003). Furthermore, similar results were found in Phoenix, Arizona, USA, where the heat island was reported as being attributed to a variety of causes: the primary high thermal inertia of built-up areas, shading by tall buildings, and moisture differences between urban and desert areas (Peña, 2008; Bunyantuyev and Wu, 2010). The current results also showed the range in LST for the mean patch size of building was 37.08–40.00 °C. The bigger the mean patch size, the higher the LST. In addition, the effects of building uses, building type, and configuration form of the building on the distribution of LST were also investigated.

The results are shown in Figure 10. The building uses were classified as residential, commercial, industrial, and mixed use. The results showed that the range of LST for every type of building use was 38–41 °C. The building types were divided into house, townhouse, row-room, row-building, apartment, office, and condominium. The range of LST in every building type was 37.2–41.5 °C. Fragment, linear, and square block patterns were represented as the configuration forms of buildings in this study. The range of LST in every configuration form was 38–42 °C because Bangkok is an urban-sprawl city, so the configuration forms of buildings were not as clear as in other developed cities. In the current study, building uses, building types, and configuration forms of buildings did not affect on differences in LST. However, Alobaydi et al. (2016) found that a detached building pattern or fragment provided higher LST than a linear block or compact block during daytime in Baghdad, Iraq. This might have been because of the higher exposure of the surfaces to solar radiation, leading to an increase in the amount of reflected and diffused solar radiation as well as the emitted thermal radiation, which in turn raises the temperature. Similar results were found in the urban area of Mashhad, Iran (Soltanifard and Aliabadi, 2018). Therefore, optimizing the configurations of the buildings may be one of the strategies to mitigate the impact of UHI.

Figure 10.

LST distribution with different building uses (A), building types (B), and compactness of buildings (C).

4. Conclusion

LST is critically influenced by urbanization due to land cover change and building configuration. This research investigated the relationships of LST with both single composition and combinations of proportions of different land covers. To manage the effect of LST in cities, suitable ratios of types of land cover should be considered. City planning for new development areas should require a suitable proportion of below green, above green and water body. Our results suggested that LST can be effectively mitigated by using green space area and public parks. Moreover, by increasing tree canopy to around 20%, water body to around 30% or green yard/shrub to around 40% of the built-up areas, it would be possible to reduce LST significantly. In the agricultural areas outside downtown Bangkok, the land should follow the best management practice for plant cultivation. In addition, the configuration of building features is also important to manage LST in a city. Building edge density, patch density of buildings, and building height were significantly related to reduced LST. In contrast, the higher the large patch and patch size of a building, the higher the LST. Moreover, building uses, building types, and configuration forms of buildings were not significantly related to changes in LST. Thus, the impact of LST can be reduced not only by organizing appropriate ratios of different land cover types but also by optimizing the configurations of the buildings. Our results provide important information for urban management through urban experimental design using planning and performed knowledge that can be applied to develop and regenerate the Bangkok Metropolitan Area.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Tratrin Adulkongkaew: Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Tunlawit Satapanajaru: Conceived and designed the experiments; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data.

Sujittra Charoenhirunyingyos, Wichitra Singhirunnusorn: Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data.

Funding statement

This work was supported by the Thailand Energy Conservation Fund under the Energy Policy and Planning Office (EPPO), Ministry of Energy, Bangkok, Thailand.

Competing interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Acknowledgements

We also thank the Department of Environmental Technology and Management, Faculty of Environment, Kasetsart University, Bangkok, Thailand for providing the geographic information system program.

References

- Alobaydi D., Bakarman M.A., Obeidat B. The impact of urban form configuration on the urban heat island: the case study of Baghdad, Iraq. International Conference on Sustainable Design, Engineering and Construction. 2016;145:820–882. [Google Scholar]

- Anongrak N. Chiang Mai University; Chiang Mai: 2010. General Soil. [Google Scholar]

- Arnfield A.J. Review two decades of urban climate research: a review of turbulence, exchanges of energy and water, and the urban heat island. Int. J. Climatol. 2003;23:1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Balogun I.A., Daramola M.T. The outdoor thermal comfort assessment of different urban configurations within Akure City, Nigeria. Urban Climate. 2019;29:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Dor E., Saaroni H. Airborne video thermal radiometry as a tool for monitoring microscale structures of the urban heat island. Int. J. Rem. Sens. 1997;18(4):3039–3053. [Google Scholar]

- Buyantuyev A., Wu J. Urban heat islands and landscape heterogeneity: linking spatiotemporal variations in surface temperatures to land-cover and socioeconomic patterns. Landsc. Ecol. 2010;25:17–33. [Google Scholar]

- Chen A., Yao L., Sun R., Chen L. How many metrics are required to identify the effects of the landscape pattern on land surface temperature. Ecol. Indicat. 2014;45:424–433. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Provincial Administration . 2019. Thailand.https://www.dopa.go.th/main/web_index/ [Google Scholar]

- Dupont C., Chiriac R., Gauthier G., Toche F. Heat capacity measurements of various biomass types and pyrolysis residues. Fuel. 2014;115:644–651. [Google Scholar]

- EPA . 2009. Reducing Urban Heat Islands: Compendium of Strategies Urban Heat Island Basics, United States. [Google Scholar]

- Forman R.T.T. Cambridge University Press; NY: 1995. Land Mosaics: the Ecology of Landscape and Regions. [Google Scholar]

- Frey C.M., Parlow E., Vogt R., Harhash M., Wahab M.M.A. Flux measurements in Cairo. Part 1: in situ measurements and their applicability for comparison with satellite data. Int. J. Climatol. 2010;31:218–231. [Google Scholar]

- Gates D.M. Springer-Verlag; New York: 1980. Biophysical Ecology. [Google Scholar]

- Gustafson E.J. Quantifying landscape spatial pattern: what is the state of the art? Ecosystems. 1998;1:143–156. [Google Scholar]

- Hamoodi M.N., Corner R., Dewan A. Thermophysical behaviour of LULC surfaces and their effect on the urban thermal environment. Spatial Sci. 2017:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Hens H.S.L. Ernts and Sohn; Berlin: 2016. Applied Building Physics: Ambient Conditions, Building Performance and Material Properties. [Google Scholar]

- Imhoff M.L., Zhang P., Wolfe R.E., Bounoua L. Remote sensing of the urban heat island effect across biomes in the continental USA. Rem. Sens. Environ. 2010;114:504–513. [Google Scholar]

- Integrated Environmental Solutions . Integrated environmental solutions limited; 2011. Apache Tables User Guide - IES Virtual Environment 6.4. [Google Scholar]

- Jayalakshmy M.S., Philip J. Thermophysical properties of plant leaves and their influence on the environment temperature. Int. J. Thermophys. 2010;31(11-12):2295–2304. [Google Scholar]

- Liang B., Weng Q. Multi-scale analysis of census-based land surface temperature variations and determinants in Indianapolis, United States. Journal of Urban Planning D-ASCE. 2008;134(3):129–139. [Google Scholar]

- Liu H., Weng Q. Scaling up effect on the relationship between landscape pattern and land surface temperature. Photogramm. Eng. Rem. Sens. 2009;75(3):291–304. [Google Scholar]

- Liu S., Li X., Chen D., Duan Y., Ji H., Zhang L., Chai Q., Hu X. Understanding Land use/Land cover dynamics and impacts of human activities in the Mekong Delta over the last 40 years. Global Ecology and Conservation. 2020;22:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Liu W., Feddema J., Hu L., Zung A., Brunsell N. Seasonal and diurnal characteristics of land surface temperature and major explanatory factors in harris county, Texas. Sustainability. 2017;9:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Mirzaei P.A., Haghighat F. Approaches to study urban heat island abilities and limitations. Build. Environ. 2010;45:2192–2201. [Google Scholar]

- Nichol J.E. “A GIS-based approach to microclimate monitoring in Singapore’s high-rise housing estates”. Photogramm. Eng. Rem. Sens. 1994;60:1225–1232. [Google Scholar]

- Nichol J.E., Fung W.Y., Lam K., Wong M.S. “Urban heat island diagnosis using ASTER satellite images and ‘in situ’ air temperature”. Atmos. Res. 2009;94:276–284. [Google Scholar]

- Peña M.A. Relationships between remotely sensed surface parameters associated with the urban heat sink formation in Santiago, Chile. Int. J. Rem. Sens. 2008;29:4385–4404. [Google Scholar]

- Rajabi T., Abu-Hijleh B. World Sustainable Building Conference”, Barcelona. 2014. The study of vegetation effects on reduction of Urban Heat Island in Dubai; pp. 155–161. [Google Scholar]

- Sailor D.J., Lu L. “A top–down methodology for developing diurnal and seasonal anthropogenic heating profiles for urban areas”. Atmos. Environ. 2004;38:2737–2748. [Google Scholar]

- Sayão V.M., José A.M., Demattê, Bedin L.G., Nanni M.R. Satellite land surface temperature and reflectance related with soil attributes. Geoderma. 2018;325:125–140. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz N., Schlink U., Franck U., Großmann K. “Relationship of land surface and air temperatures and its implications for quantifying urban heat island indicators—an application for the city of Leipzig (Germany)”. Ecol. Indicat. 2012;18:693–704. [Google Scholar]

- Senanayake I.P., Welivitiya W.D.D.P., Nadeeka P.M. Remote sensing-based analysis of urban heat islands with vegetation cover in Colombo city, Sri Lanka using Landsat-7 ETM+ data. Urban Climate. 2013;5:19–35. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma R., Joshi P.K. “Identifying seasonal heat islands in urban settings of Delhi (India) using remotely sensed data – an anomaly based approach”. Urban Climate. 2014;9:19–34. [Google Scholar]

- Soltanifard H., Aliabadi K. Impact of urban spatial configuration on land surface temperature and urban heat islands: a case study of Mashhad, Iran. Theoretical and Applied Climatology. 2018;1–15 [Google Scholar]

- Srivanit M., Kazunori H. The influence of urban morphology indicators on summer diurnal range of urban climate in Bangkok metropolitan area, Thailand. Journal of Civil and Environmental Engineering IJCEE-IJENS. 2011;11(5):34–46. [Google Scholar]

- Srivanit M., Kazunori H. Thermal infrared remote sensing for urban climate and environmental studies: an application for the city of Bangkok, Thailand. Journal of JARS. 2012;9(1):83–100. [Google Scholar]

- Turner M.G. Landscape ecology: what is the state of the science? Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2005;6:319–344. [Google Scholar]

- USGS . U.S. Geological Survey.; 2016. Using the USGS Landsat 8 Product.http://glovis.usgs.gov/ [Google Scholar]

- Voogt J.A., Oke T.R. Thermal remote sensing of urban climates. Rem. Sens. Environ. 2003;86:370–384. [Google Scholar]

- Wu C., Xiao Q., McPherson E.G. A method for locating potential tree planting sites in urban areas: a case study of Los Angeles, USA. Urban For. Urban Green. 2008;7(2):65–76. [Google Scholar]

- Wu H., Ye L., Shi W., Clarke K.C. Assessing the effects of land use spatial structure on urban heat islands using HJ-1B remote sensing imagery in Wuhan, China. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2014;32:67–78. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou W., Huang G., Cadenasso M.L. Does spatial configuration matter? Understanding the effects of land cover pattern on land surface temperature in urban landscapes. Landsc. Urban Plann. 2011;102:54–63. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou W., Wang J., Cadenasso M.L. Effects of the spatial configuration of trees on urban heat mitigation: a comparative study. Rem. Sens. Environ. 2017;195:1–12. [Google Scholar]