Abstract

Purpose

The non-arteritic form of anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (AION) is the most common acute optic neuropathy among individuals over the age of fifty, yet little is known about how the disorder affects color vision. We tested the hypothesis that color vision correlates with visual acuity in patients with non-arteritic AION. We also evaluated the patterns of visual field loss in a subgroup of patients who manifested relative sparing of color vision.

Observations

Records of forty-five patients with non-arteritic AION who had been evaluated at Duke University over a consecutive four-year period were reviewed retrospectively. Statistical analysis of the relationship between color vision and visual acuity was carried out using a linear regression model. Color vision tended to correlate with acuity with respect to visual acuities between 20/16 and 20/63. However, nine patients were identified in whom color vision was relatively spared in comparison with acuity. Most of the affected eyes in this subgroup had a distinctive pattern of visual field loss consisting of a dense, steep-walled cecocentral defect centered below the horizontal meridian.

Conclusions and importance

In patients with non-arteritic AION, color vision tends to correlate with visual acuity for acuities better than 20/70. Sparing of color vision relative to acuity, a heretofore unreported finding in AION, occurs in approximately 15% of cases. Sparing of color vision reflects damage to foveal projections coupled with preservation of extrafoveal macular projections. The results of color vision testing in patients with non-arteritic AION help to differentiate this condition from other optic neuropathies such as optic neuritis.

Keywords: Color vision, Anterior ischemic optic neuropathy, Optic nerve disease, Dyschromatopsia, Visual sensory testing, Neuro-ophthalmologic evaluation

1. Introduction

Non-arteritic AION is the most common acute optic neuropathy among individuals over the age of fifty. The clinical presentation, demographic profile and natural history of the disorder are well established. However, with respect to visual compromise, nearly all published descriptions have focused on visual field defects and reduced visual acuity. Comparatively little attention has been paid to the associated deficits of color vision, despite the fact that: a) dyschromatopsia is a sensitive indicator of optic nerve dysfunction, and b) assessment of color vision is a standard part of the neuro-ophthalmic examination. We undertook this study to review the results of color vision testing in patients with non-arteritic AION and to evaluate the relationship between color vision and visual acuity.

2. Methods

We identified all patients with a diagnosis of non-arteritic AION who had been evaluated at the Duke University Eye Center by a single physician (S.C.P.) over a four-year interval. A retrospective review of patient records confirmed that each patient had a history of acute painless loss of vision, a neuropathic pattern of field loss, an afferent pupillary defect (in unilateral cases), and either acute optic disc swelling or reliable documentation of previous swelling at the onset of symptoms. At the time of each consultation, color vision was evaluated using Hardy-Rand-Rittler (HRR) pseudoisochromatic plates 1 through 10. The test distance was approximately 14 inches, with some variation based on patient preference and physician technique. Near correction was employed whenever appropriate. Levels of ambient illumination were not standardized, though all examinations were performed in lanes with identical ceiling light sources. A given response was counted as correct if the patient identified either: a) the shape of the symbol, or b) both the color and location of the symbol. For plates with two symbols, each symbol was counted as one-half. Refraction was performed using a phoropter, a projector and a mirror to determine best-corrected Snellen acuity at an effective distance of 20 feet. Corrected near acuity was obtained using a standard near card. In each case, the visual sensory evaluation was carried out by the neuro-ophthalmology attending, a neuro-ophthalmology fellow, or a resident on the Neuro-Ophthalmology Service.

Conversion of Snellen acuities to LogMAR was based on the following equation: LogMAR = log10 (Snellen denominator/Snellen numerator). Equivalent Snellen acuities for counting fingers, hand motion and light perception at two feet were identical to those used for the Ischemic Optic Neuropathy Decompression Trial. Snellen equivalents for counting fingers at distances greater than two feet were obtained by extrapolation.

A scatterplot of color vision as a function of LogMAR visual acuity was generated (Fig. 1). For the limited range of LogMAR visual acuity 0 to 0.5 (Snellen 20/20 to 20/63), and for patients without relative sparing of color vision, the relationship between LogMAR visual acuity and number of HRR plates was assessed using linear regression. Visual acuity was the only predictor in the model.

Fig. 1.

Scatterplot of color vision as a function of LogMAR visual acuity. The relationship tends to be linear with respect to LogMAR acuities between –0.10 and +0.50 (between Snellen acuities of 20/16 and 20/63). Nine eyes, represented in green, exhibited sparing of color vision relative to acuity.

3. Results

45 patient records were reviewed. 30 cases were unilateral and 15 cases were bilateral, yielding a total of 60 affected eyes. Mean patient age was 64. The ratio of female to male patients was 5:4. All of the patients were Caucasian.

With respect to acuities between LogMAR –0.10 and +0.50 (20/16 to 20/63), and for patients without relative sparing of color vision, the slope of the regression line was significantly different from zero (p = 0.004, r2 = 0.353), indicating that for every unit decrease in LogMAR visual acuity, the number of HRR plates decreases by 18.31. Accordingly, normal acuity was associated with normal or nearly-normal color vision, while reductions in acuity tended to be accompanied by commensurate color deficits. By contrast, acuities of 20/70 or worse were generally associated with an inability to identify any of the first ten HRR test plates.

Nine patients were identified in whom color vision was relatively spared in comparison with acuity. The demographic profile of this subgroup was similar to that of the study group as a whole except for a male preponderance (78%). Seven of the patients had unilateral AION, while two patients with bilateral involvement had relative sparing of color vision limited to just one eye. The nine affected eyes, accounting for 15% of the total, are represented by green data points in Fig. 1.

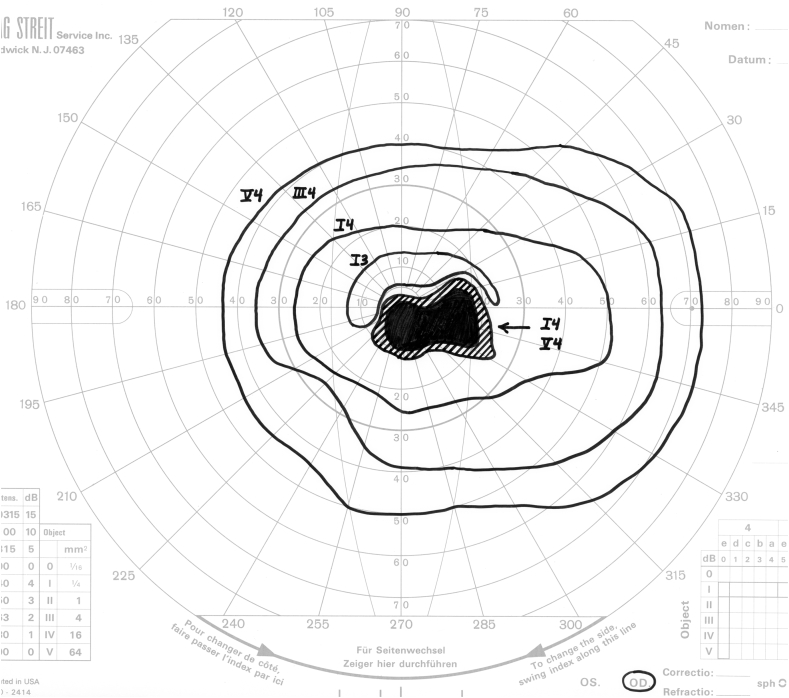

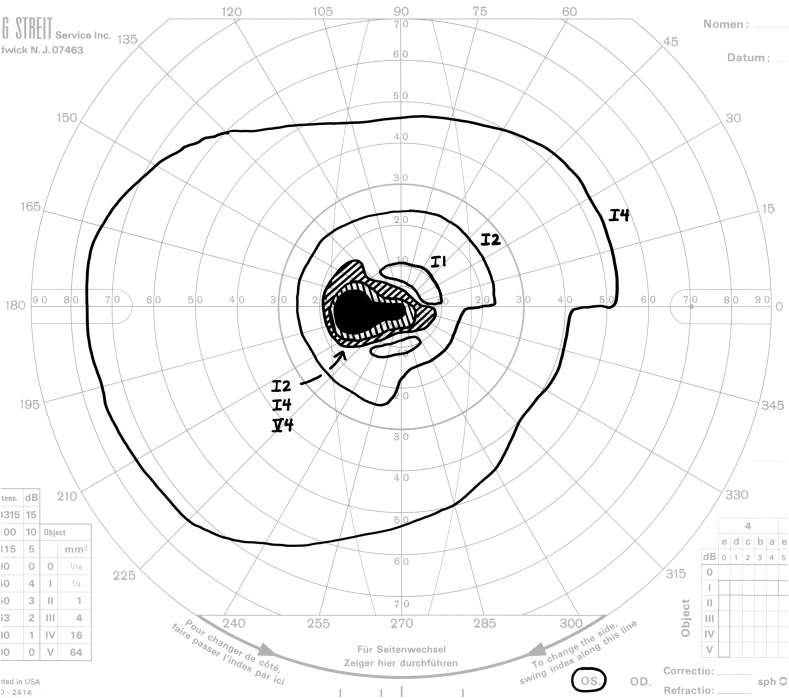

A distinctive pattern of visual field loss (Fig. 2) was present in seven of the nine eyes in which color vision was relatively spared. Each defect consisted of a dense, steep-walled cecocentral defect centered below the horizontal meridian. We refer to this as an off-axis cecocentral scotoma. The steep boundaries impart a strikingly discrete character to these defects. As a result, profound loss of sensitivity involving fixation is associated with preservation of essentially normal sensitivity 3–5° above fixation.

Fig. 2.

Four examples of off-axis cecocentral scotomata. Note that in each case, the defect is dense, steep-walled, and centered below the horizontal meridian.

The two remaining patients with relative sparing of color vision had inferior altitudinal defects that bowed upward centrally and overlapped fixation by several degrees.

4. Discussion

Impaired color perception is a sensitive sign of optic nerve dysfunction and is nearly always present in patients with optic nerve disease. The relationship between color vision and visual acuity is of particular diagnostic importance. When compared to other categories of disease (e.g. maculopathies, amblyopia, etc.), optic neuropathies affect color vision to a more significant degree at any given level of acuity.1 Optic neuritis has been studied most extensively in this regard.2 It is generally accepted that in the acute phase of optic neuritis, the degree of dyschromatopsia tends to be out of proportion to the loss of acuity.3 By contrast, relatively little is known about the impact of non-arteritic AION on color vision. Carlow and Huaman4 studied visual sensory deficits in 65 eyes of patients with non-arteritic AION and concluded that color vision remained normal until visual acuity dropped to 20/70. Over the last thirty years, that conclusion has gradually given way to the view that loss of color vision tends to parallel loss of visual acuity in patients with AION,5,6 though this hypothesis has not been formally investigated. Our study confirms that color loss tends to correlate with acuity loss in a generally linear fashion, at least for acuities in the range of 20/16 to 20/63. When acuity is normal, color perception remains intact or nearly so. When acuity is decreased, color vision is also affected, and the degree of dyschromatopsia tends to be commensurate with the reduction in acuity.

Acuities of 20/70 or below were generally associated with an inability to identify the first ten HRR test plates. However, our data does not support the conclusion that acuities of 20/70 or below are associated with a complete absence of color vision. The hues that comprise the first ten HRR plates are the least saturated of the set. Accordingly, they are the most sensitive for detection of early and/or subtle defects. Among patients who are unable to identify any of the initial ten plates, many retain some degree of residual color perception. Had testing included all of the HRR plates, it is possible that the relationship established for acuities between 20/16 and 20/63 would have extended to acuities of 20/70 and below.

An unexpected outcome of our study was the identification of a subgroup of nine patients in whom color vision was relatively preserved. In each of these cases, significant reductions in visual acuity were not accompanied by commensurate reductions in color vision. This finding represents an inversion of the usual relationship between acuity and color in the context of optic nerve disease, and it may be unique to AION. The study by Traustason et al.7 is relevant in this regard. Although the primary purpose of that study was to classify visual field defects in non-arteritic AION using automated perimetry, the clinical report includes detailed visual sensory data for each of the 47 study eyes. Our review of that data revealed that 7 eyes (15%) exhibited relative sparing of color vision. This percentage is identical to that identified in our study.

In patients with non-arteritic AION and preservation of color perception relative to acuity, the reduction in acuity would appear to indicate that foveal projections have been damaged at the level of the optic nerve head. At the same time, retention of relatively good color vision suggests that a substantial population of extra-foveal macular fibers has been spared and thus remains functional. These assumptions are compatible with an ischemic mechanism of nerve injury since ischemic events often produce tissue damage in sharply-delimited vascular territories, with zones of infarction situated adjacent to normally-functioning tissue.

As noted above, seven of nine eyes with relative sparing of color vision manifested a distinctive pattern of field loss consisting of a steep-walled cecocentral defect centered below the horizontal meridian. The highly discrete boundaries of these defects are consistent with a vascular mechanism of neural injury. In addition, each defect overlaps fixation but spares a substantial portion of the central field above the horizontal meridian, lending further support to the hypothesis that relative sparing of color vision is due to selective loss of foveal projections in combination with sparing of extra-foveal macular fibers. The documentation of essentially normal sensitivity in the central field beginning 3–5° above fixation indicates that, in each case, the preserved macular fibers are those originating in the inferior half of the macula outside of the fovea.

Off-axis cecocentral defects in the setting of non-arteritic AION have been reported previously. Boghen and Glaser's classic paper8 includes an example of such a defect in Table III under the heading “Central Scotoma.” More recently, in their thorough review of visual field abnormalities in 312 eyes with non-arteritic AION, Hayreh and Zimmerman9 identify twenty-two major categories of defects. Among these are “cecocentral scotoma” and “central scotoma involving mainly inferior central region.” The latter category is further described as a central scotoma that includes fixation but has most of its area situated inferiorly. These two categories are not mutually exclusive. The authors point out that most of the eyes in their study had more than a single type of defect, i.e., most eyes had defects that fell into more than one of the twenty-two major categories. It therefore seems likely that at least some of the eyes in Hayreh and Zimmerman's study had cecocentral defects that were centered below the horizontal meridian.

The two most common acute optic neuropathies in adults are non-arteritic AION and optic neuritis (ON). In most cases, the distinction between these two entities can easily be made on clinical grounds. However, the well-documented overlap in clinical profiles10 can sometimes make differentiation a challenge. One might reasonably ask if the existence of cecocentral defects in a subgroup of AION patients represents yet another overlapping clinical manifestation. While we cannot state with assurance that the pattern of field loss described in this report never occurs in patients with ON, we can point out that: a) cecocentral defects in ON typically exhibit gradually sloping borders; b) cecocentral defects in ON tend to straddle the horizontal meridian, with equal areas above and below the horizontal; and c) to our knowledge, relative sparing of color vision is not a feature of ON.

This report reflects the limitations of a retrospective case series. First, only a single measure was used to assess color vision. Had this been a prospective study, we could have incorporated at least one additional method of measurement. A second issue pertaining to methodology relates to the timing of evaluations. Some patients were referred for evaluation in the acute phase of AION while others were referred for evaluation in the late phase, i.e., after resolution of optic disc swelling. Given that the results of visual sensory testing in patients with non-arteritic AION are not consistently stable but can improve or worsen over a period of months, it is possible that our data would have been somewhat different if all patient evaluations had taken place at a defined interval from the onset of symptoms.

5. Conclusions

Our study helps to fill a longstanding gap in the clinical picture of non-arteritic AION, confirming for the first time that color vision tends to correlate with visual acuity, at least for acuities better than 20/70. In addition, the study identifies a subgroup of patients with AION who manifest relative sparing of color vision, a finding that may be unique to AION. The pattern of field loss that most commonly accompanies spared color vision ― a steep-walled off-axis cecocentral scotoma ― supports the contention that relative sparing of color vision is due to selective loss of foveal projections in combination with sparing of extra-foveal macular fibers. Finally, this study demonstrates that the results of color vision testing in patients with non-arteritic AION help to differentiate this condition from other optic neuropathies.

Patient consent

Consent to publish each case in the series was not obtained. This report does not contain any personal information that could lead to the identification of any of the patients. The manuscript is in compliance with HIPAA regulations.

Funding

No funding or grant support was received for this study.

Authorship

All authors attest that they meet the current ICJME criteria for Authorship.

Declaration of competing interest

Neither author has any financial disclosures, and neither has any conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Dr. Sandra Stinnett, Associate Professor of Biostatistics and Bioinformatics at Duke University, for her assistance with the statistical analysis.

References

- 1.Almog Y., Nemet A. The correlation between visual acuity and color vision as an indicator of the cause of visual loss. Am J Ophthalmol. 2010;149:1000–1004. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2010.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schneck M.E., Haegerstrom-Portnoy G. Color vision defect type and spacial vision in the Optic Neuritis Treatment Trial. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1997;38:2278–2289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Foroozan R., Buono L.M., Savino P.J., Sergott R.C. Acute demyelinating optic neuritis. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2002;13(6):375–380. doi: 10.1097/00055735-200212000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carlow T.J., Huaman A. NANOS scientific platform presentation and abstract; 1989. Anterior Ischemic Optic Neuropathy (AION): Color Vision and Visual Evoked Potential Patterns. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arnold A.C. Ischemic optic neuropathy. In: Miller N.R., Newman N.J., editors. Sixth ed. Vol. 1. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia: 2005. pp. 349–384. (Walsh & Hoyt’s Clinical Neuro-Ophthalmology). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kerr N.M., Chew S.S.S.L., Danesh-Meyer H.V. Non-arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy: a review and update. J Clin Neurosci. 2009;16:994–1000. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2009.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Traustason O.I., Feldon S.E., Leemaster J.E., Weiner J.M. Anterior ischemic optic neuropathy: classification of field defects by OctopusTM automated static perimetry. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1988;226:206–212. doi: 10.1007/BF02181182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boghen D.R., Glaser J.S. Ischemic optic neuropathy. The clinical profile and history. Brain. 1975;98(4):689–708. doi: 10.1093/brain/98.4.689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hayreh S.S., Zimmerman B. Visual field abnormalities in nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123:1554–1562. doi: 10.1001/archopht.123.11.1554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rizzo J.F., Lessell S. Optic neuritis and ischemic optic neuropathy. Overlapping clinical profiles. Arch Ophthalmol. 1991;109:1668–1672. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1991.01080120052024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]