Abstract

Intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) is a devastating clinical event, which results in a high rate of disability and death. At present no effective treatment is available for ICH. Accumulating evidence suggests that inflammatory responses contribute significantly to the ICH-induced secondary brain outcomes. During ICH inflammatory cells accumulate at the ICH site attracted by gradients of chemokines. This review summarizes recent progress in ICH studies and the chemoattractants that act during the injury, focuses on and introduces the basic biology of the chemokine monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP1) and its role in the progression of ICH. Better understanding of MCP1 signaling cascade and the compensation after its inhibition could shed light on the development of effective treatments for ICH.

1. Intracerebral Hemorrhage (ICH)

1.1. Introduction

ICH, caused by the rupture of weakened blood vessels and bleeding into the brain constitutes 15–20% of all strokes. It affects between 0.12 and 2 million people each year in the United States and worldwide, respectively [1–3]. Due to the aging of populations, these numbers are expected to grow. The primary causes of ICH are hypertensive arteriosclerosis and amyloid angiopathy [4, 5]. In addition, cerebrovascular malformations, neoplasia, coagulation disorders, and thrombolysis treatment also contribute to the incidence of ICH [4, 5]. The prognosis of ICH is poor: the one-year survival rate is only 38% [6] and about 90% of the survivors experience long-term physical and mental disability [7, 8].

1.2. Pathophysiology

At the onset of ICH, the initial bleeding leads to formation of hematoma and increase of intracranial pressure, which result in primary injury to the brain. A secondary injury is mainly caused by the subsequent inflammatory responses [9, 10]. The blood and its components at the injury site activate brain resident immune cells, microglia, which secrete inflammatory mediators [11, 12], which results in an amplification of the inflammatory response. Infiltrating peripheral polymorphonuclear leukocytes and monocytes as well as brain edema are evident [13–15]. In addition, cerebral mast cells have been shown to also contribute to the secondary injury after ICH [16, 17]. The migration into the CNS and the accumulation of the inflammatory cells results in the release of cytotoxic molecules that cause cell death in the peri-hematoma area. As the injury progresses, dead cells are cleared and eventually the hematoma can be resolved. These reparative processes, interestingly, are executed by the same cells that cause the secondary brain injuries (activated microglia and infiltrated leukocytes) [9, 18].

1.3. Animal Models of ICH and progression of pathology

There are several animal models of ICH, but two are the most widely used to mimic clinical symptoms and pathological changes of human ICH: the collagenase-induced ICH model and the whole-blood model. In the first model, collagenase, a bacterial enzyme, is injected to the brain (mostly in striatum), where it degrades collagen IV, a major component of blood vessel wall, causing rupture of the blood vessels and thus ICH [11, 12, 19]. This model is simple and replicates the blood vessel rupture pathology in ICH patients. Additionally, it is very reproducible. The size and location of hematoma reported by various laboratories are consistent [9, 20–22]. However, it should be noted that the collagenase induced ICH model has two major drawbacks. First, it does not replicate the vascular injury observed in human patients prior to ICH, such as hypertension/atherosclerosis induced vascular changes. Second, it introduces an exogenous enzyme, bacterial collagenase, into the brain. Although there is evidence suggesting that collagenase alone does not activate microglia or affect cell survival [11, 23, 24], it modifies the extracellular matrix around its delivery site, and may alter inflammatory or immune responses via other cell types or pathways and thus affect the progress of ICH. In the whole-blood model, blood either from the animal itself or a donor is injected into the brain (usually striatum). Such delivery replicates the pathology after rupture of blood vessels in human patients [25–29]. Like the collagenase induced ICH model, the whole-blood model also has some disadvantages: it lacks the pathologically injured vasculature, and does not cause rupture of blood vessels. The lesion size and location from this model is less reproducible compared to collagenase ICH. It has been reported that the whole blood model usually results in an umbrella-shaped narrower slit-like lesion [30], probably due to the rapid distribution of blood along corpus callosum or white matter tracts.

Both models have advantages and disadvantages. However, neither of them could mimic all the pathological changes of ICH in human patients. Recently, a spontaneous ICH model has been developed in rodents [31]. This new model induces ICH via acute hypertension, the most common etiology of hemorrhagic stroke. The pathophysiology and reproducibility of this new model needs further investigation.

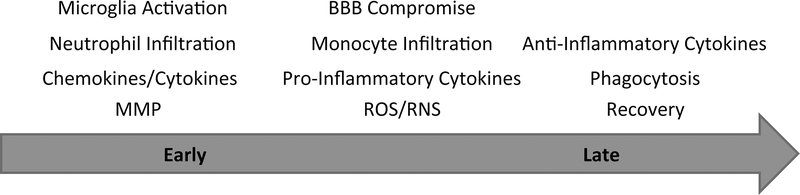

In all ICH models blood leaks into the brain parenchyma. Similarly to the human condition, the accumulation of blood in the brain increases the intracranial pressure, causing immediate primary injury. In the collagenase model within 30 minutes the entrance of blood components, cellular and molecular, such as red blood cells, leukocytes, proteases, hemoglobin, iron deposition into the brain leads to inflammatory responses, which initially involve the microglia, the brain resident immune cells [32]. Microglia change their morphology, alter gene expression profile, secrete inflammatory mediators, proliferate and migrate to site of injury [11, 12]. Other cell types, such as astrocytes, infiltrating macrophages, monocytes and neutrophils, are also activated and migrate to the hematoma site [9, 33, 34]. Early after ICH, these activated cells secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines/chemokines, including TNF-α, IL-1β, and MCP1/CCL2, recruit additional inflammatory cells to the injury site, and form a barrier preventing the spread of injury to other sites [9–11]. With the progression of disease, inflammatory cells, especially microglia and macrophages, transit from pro-inflammatory to anti-inflammatory states. They clear cell debris at the site of injury by phagocytosis, thus promoting recovery [9, 10, 35], which in the collagenase model takes place within 15–20 days after the induction of ICH. With the resolution of hematoma, those activated inflammatory cells become resting again [11, 22]. The time course schematic of ICH is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Time course of ICH.

Early after ICH, microglia become activated and migrate to the site of injury. Fast-responding neutrophils infiltrate into the brain and together with activated microglia, produce MMP and chemokines/cytokines. With the progression of disease, BBB is compromised and monocytes enter the brain. Activated microglia and infiltrated leukocytes generate pro-inflammatory cytokines, which together with ROS produced by lipid peroxidation induce cell death. At the later stage of ICH, the micro-environment changes from pro-inflammatory to anti-inflammatory. Activated microglia and infiltrated cells clear cell debris by phagocytosis, thus promoting recovery.

2. Chemokines

Chemokines are small basic proteins that activate and attract immune cells in response to insult [36–39]. Four types of chemokines are found based on the number and position of conserved cysteine on their primary sequences: C, CC, CXC, and CXXXC [40–42]. CXC chemokines recruit short-lived but fast responding neutrophils, whereas CC chemokines induce the migration of monocytes and cells of monocytic origin, like microglia [43]. Chemokines exert their functions via their high affinity receptors [44]. It has been shown that one receptor may have more than one ligands [9] and one ligand may interact with more than one receptors. This promiscuity makes the chemokine-receptor system very complex.

During ICH there have been many reports indicating that chemokines become upregulated [9, 45, 46], functioning to attract local and systemic immune cells into the CNS parenchyma. In a functional analysis study using human samples, many chemokines related to leukocyte extravasation, including CXCL8 (IL-8), CXCL2, CXCL5, CCL3, CCL4, and CCL20, have been found to be over-expressed in perihematomal areas [45]. In another study using human brain samples, besides the chemokines mentioned above, CCR1 and downstream effector molecules related to chemokine signaling were also reported to be activated [47]. These data suggest a pivotal role of chemokines and chemokine receptors on ICH.

2.1. MCP1

MCP1, a CC type chemokine (also called CCL2), is drastically upregulated and transiently expressed during injury or inflammation in the central nervous system (CNS), and acts on its receptor CCR2. Under physiological conditions, MCP1 is expressed at low levels by neurons, astrocytes and brain microvascular endothelial cells (BMEC) in the CNS [48–63]. Upon injury, however, the expression of MCP1 is dramatically increased. It is believed that, after it is released into the extracellular space, MCP1 forms a gradient to attract CCR2-expressing monocytes and microglia.

Microglia are the immune-competent cells in the brain. Under physiological conditions, they have a ramified morphology (smaller cell body surrounded by many long, thin, and highly dynamic processes). They extend and retract their processes continually to sense changes in the surrounding microenvironment [64]. When an injury occurs, microglia become activated. They change to an ameboid morphology, alter their gene expression profile, migrate to site of injury, and affect the outcome of injury [65–70].

Accumulation of monocytes and activated microglia has been found in many CNS injuries, such as ischemia, excitotoxicity and hemorrhage [70–77]. Lack of CCR2, however, abrogates the trafficking of microglia and leukocytes, indicating that MCP1-induced chemotaxis is dependent on CCR2 [78, 79]. In kainate-induced excitotoxicity model, we and others found that microglial migration/accumulation was attenuated in MCP1−/− mice and wild-type mice administered with MCP1 blocking antibody [76, 80]. Interestingly, similar results were found in mice lacking plasminogen (plg) or tissue plasminogen activator (tPA), which converts plg to active plasmin [81, 82]. These results suggest that MCP1-CCR2 axis may crosstalk to the plg activation system. Further studies in our lab showed that plasmin cleaved MCP1 at K104, generating a N-terminal fragment with a much higher chemotactic potency [76, 83]. In our rescue experiments, we found infusion of plasmin-cleaved-, but not full length (FL)-MCP1 into the CNS restored excitotoxicity-induced microglial activation/migration and subsequent neuronal death in plg−/− mice, suggesting plasmin-truncated MCP1 is the active form of MCP1. Further mechanistic studies revealed that plasmin-truncated MCP1 activated Rac1 and promoted the formation of lamellipodia more efficiently than FL-MCP1 [83].

MCP1 exerts its biological functions by binding to its high affinity receptor, CCR2, a G-protein-coupled receptor. Although MCP1 can only bind to CCR2, CCR2 has multiple ligands, including MCP1 (CCL2), MCP2 (CCL8), MCP3 (CCL7), MCP4 (CCL13) [84–86]. The relative contribution of each ligand to CCR2-mediated functions remains elusive [87, 88]. It should be noted that there is only CCR2 isoform in humans, whereas two CCR2 isoforms with different C-terminus are found in rodents [89], which may suggest different ways of regulation on MCP1 activity.

In the peripheral system, CCR2 is expressed in the so-called inflammatory cells, including monocytes, dendritic cells and memory Th1 cells [90–92]. In the CNS, CCR2 is expressed by various cell types, such as neurons, astrocytes, and microglia, and microvascular endothelial cells [14, 93–97]. Under physiological conditions, the CCR2 expression levels are very low. When an injury occurs, however, the expression of CCR2 is dramatically upregulated primarily in astrocytes and microglia [98–100].

Binding of MCP1 on microglial (or astrocytic) cell surface induces the internalization of CCR2, probably via endocytosis [13]. This mechanism has been suggested to regulate extracellular MCP1 levels [101–103] or facilitate the transcytosis of MCP1 across endothelial cells [97]. Many signaling molecules, including mitogen-activated protein kinases, protein kinase C, and Rho, are activated following MCP1-CCR2 interaction [14, 15, 104], suggesting that a variety of signaling pathways are involved.

2.2. MCP1 and ICH

Given that inflammation plays a crucial role in brain injury after ICH and that MCP1 is a potent chemoattractant for monocytes/microglia, we investigated the role of MCP1-CCR2 system in ICH. In collagenase ICH model, we found that mice deficient for MCP1 or CCR2 had smaller hematoma early after ICH. The size of hematoma at later stage, however, was bigger in the knockout mice [105], suggesting a delayed recovery. Consistent with the important role of MCP1 on microglial recruitment, the activation/accumulation of microglia was attenuated in the knockout mice early after injury. Surprisingly, 3 and 7 days post injury, more microglia were found in the knockout mice than in wt mice [105], suggesting activation of MCP1-CCR2 independent signaling events in the knockout mice. Besides, the infiltration of fast-responsive neutrophils and total leukocytes was decreased 1–3 and 7 days post injury, respectively, in both knockout mice. These data are consistent with our previous findings that MCP1−/− and/or CCR2−/− mice have a “tighter” BBB [13, 105]. Although not changed among different genotypes early after injury, the functional marker, inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) kept at high level 7 days post injury in the knockout mice, indicating a long-lasting activation of ROS in the knockout mice. In addition, brain edema and neuronal loss decreased overtime in wt mice but the opposite was found in both knockout mice. Neurological functions were mirrored by these pathological changes [105]. Together, these data suggest that early inhibition of MCP1-CCR2 axis after ICH could be therapeutic. It should be noted that long-term inhibition of MCP1-CCR2 may be detrimental because lack of MCP1 or CCR2 delays the recovery of ICH.

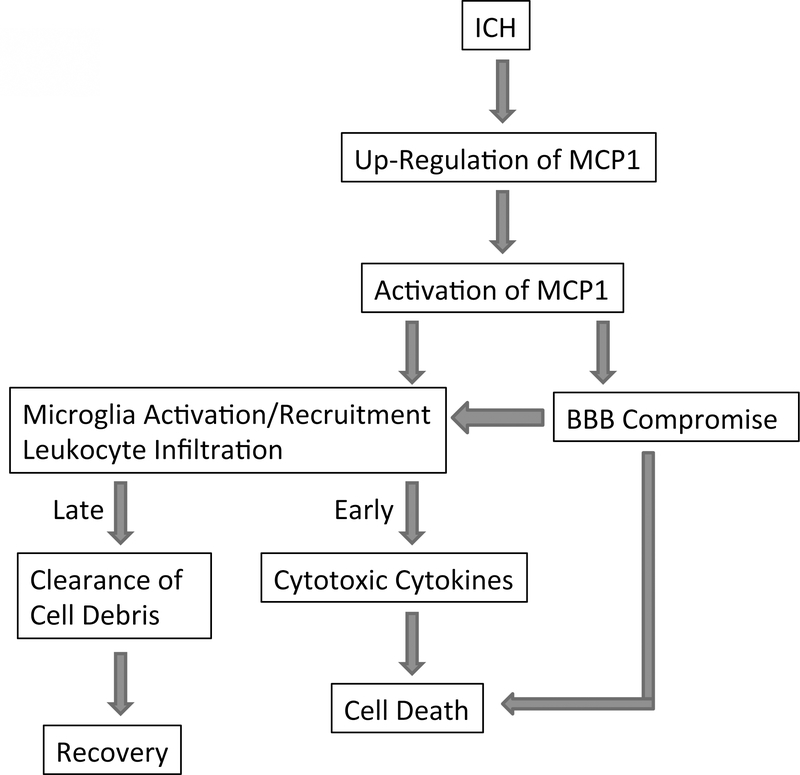

Since plasmin cleaves and activates MCP1 and it is the active MCP1 that compromises the integrity of BBB in mice, we asked whether plasmin-mediated activation of MCP1 is involved in ICH. Infusion of plasmin-truncated MCP1 and FL-MCP1 back to MCP1−/− mice significantly increased the injury volume 1 day post injury but speeded up the resolution of hematoma. Similarly, neutrophil (early after ICH) and leukocyte (later after ICH) infiltration was increased in these mice. Microglial activation/accumulation and iNOS expression increased early but decreased later after ICH. Brain edema, neuronal loss and neurological functions followed the same trend. It is worth noting that the changes are more significant in mice with plasmin-truncated MCP1 injection than that with FL-MCP1 injection. Infusion of plasmin-uncleavable MCP1, on the other hand, did not change the pathological patterns of MCP1−/− mice over time. Taken together, our data suggest that plasmin-mediated truncation of MCP1 does play a critical role in ICH in mice. The role of MCP1 after ICH is summarized in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Role of MCP1 in ICH.

ICH induces up-regulation of MCP1, which is further activated by plasmin in rodents (by other mechanisms in humans). The activated MCP1 then activates/recruits microglia and induces leukocyte infiltration. Additionally, activated MCP1 disrupts the integrity of BBB, promoting the infiltration of leukocytes into the brain and cell death. The infiltrated cells and activated microglia secrete cytotoxic cytokines early after ICH, and clear cell debris probably via phagocytosis at later stages.

Since human MCP1 does not contain the C-terminal tail found in mouse MCP1, which is removed by plasmin [105], plasmin-mediated activation of MCP1 does not work in humans. Whether human MCP1 needs to be activated and what is the mechanism remains elusive. Based on the fact that rodents have only one CCR2, whereas humans have two alternatively spliced forms of CCR2 (CCR2A and CCR2B) [89], we speculate that the various expression level of the CCR2 isoforms in different cells may be a way to regulate MCP1 activity in humans. It has been shown that CCR2B is the major isoform for monocytes and activated NK cells, whereas mononuclear cells and vascular smooth muscle cells predominately express CCR2A [106]. Additionally, human MCP1 activity may also be regulated at transcription level or protein level (turnover rate) or by post-translational modifications. These data suggest that MCP1 and/or CCR2 instead of plasmin should be targeted for the treatment of ICH in humans.

3. Targets for ICH Treatments

Currently the therapy for ICH is primary supportive care and control of medical risk factors, such as high intracranial pressure [107, 108]. There are no effective treatments to attenuate the consequences of ICH. Thus new effective treatments are necessary. Since inflammation plays an important role in the secondary injuries after ICH, anti-inflammatory therapies may be a path to pursue. In fact, many inflammatory targets, such as microglial activation, leukocyte infiltration, matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) activation, and reactive oxygen species (ROS) production are being explored.

3.1. Microglial Activation

Microglia are the first non-neuronal cell type that responds to ICH in the brain. They become activated within an hour after the onset of ICH [29, 109], their activation peaks at 3–7 days [11, 12, 105, 110], and return to normal by 3–4 weeks [111, 112]. Many studies suggest that activated microglia contribute to both ICH-induced early [9, 18, 113] and secondary brain injury [9, 10, 35]. Activated microglia may damage the brain by releasing cytotoxic factors, such as iNOS, cytokines, chemokines, prostaglandins, cyclooxygenase-2, ROS, and proteases [9, 10, 105, 109]. However, it should be noted that activated microglia may also play neuroprotective roles by secreting growth factors and phagocytosing cell debris. Which role they play is largely dependent on the time that has elapsed since the injury. Previous work in our lab showed that microglia/macrophage inhibitory factor (the tripeptide MIF/TKP) inhibited the activation of microglia, decreased hematoma volume, and improved neurological function when given 2 days before or 2 hours after in collagenase-induced ICH model [11, 12]. Consistently, inhibition of microglial activation with minocycline, a neuroprotectant that inhibits MMPs [114], played a beneficial role by reducing brain edema and maintaining BBB integrity, although neuronal death was not changed [115–118].

3.2. Leukocyte Infiltration

Accumulating evidence shows that leukocytes infiltrate into the brain and accumulate in the penumbra after ICH [9, 33, 109]. In both collagenase and whole-blood ICH models, neutrophils were reported to infiltrate into the brain in as early as 4 hours and peak around day 3 in mice and rats [34, 105, 109, 111, 119]. In human postmortem brains, leukocytes were found in or around hematoma and their infiltration correlated with cell death in the CNS [120, 121]. In addition, the number of leukocytes in peripheral blood positively correlates with hematoma volume and has been considered an independent predictor of early clinical worsening in primary ICH [122, 123]. Similar to activated microglia, neutrophils may exacerbate brain injury by secreting pro-inflammatory cytotoxic mediators [124], producing ROS, and compromising the BBB integrity [125]. It has been shown that lack of CD18, a surface molecule important for the infiltration of leukocytes, decreases brain neutrophil number, brain edema, and mortality in collagenase induced ICH model [126].

3.2.1. MMP Activation

During inflammation MMPs become activated and mediate extracellular remodeling. MMPs are expressed at low level and in an inactive state in normal brain. Upon injuries, however, MMPs are upregulated and activated by other MMPs, plasmin, or tPA. Studies in our lab showed that MMP-2 and MMP-9 activities were increased 1–3 days post ICH in mice [11, 34]. The increase of MMP-9 activity has been confirmed in other ICH models [28, 127–131]. Other MMPs, including MMP-3 and −12 have also been reported to increase after ICH [116, 132]. It has been shown that mice deficient for MMP-3, −9, and −12 show less brain injury after ICH [28, 132, 133]; on the other hand, Tang and colleagues reported that MMP-9−/− mice have enhanced hemorrhagic brain injury [19]. This discrepancy could be due to different experimental conditions. In addition to genetically modified mice, pharmacological inhibitors have also been used to block MMPs activities. It has been shown that the broad-spectrum MMP inhibitors BB-1101 and GM6001 reduce brain edema, decrease brain injury, and improve neurological functions after ICH [34, 127, 134]. Minocycline has been reported to reduce brain edema and improve functional recovery, although it does not reduce neuronal death [115, 135]. Minocycline, however, failed to promote functional recovery when given 3 hours after ICH [136]. This negative result could be due to different animal models or timing of drug administration. Studies using human samples mainly focused on MMP-9. Accumulating evidence showed that blood MMP-9 levels increased after acute spontaneous ICH and were associated with subsequent pathological changes [123, 137–139]. MMP-9 level has also been reported to associate with BBB integrity after stroke in humans [140]. Pathological studies using postmortem human brains (within 6 hours after death) revealed that MMP-9 was upregulated in neurons and reactive astrocytes in peri-hematoma area [20, 141]. Expression of MMP-9 was also increased in the ipsilateral hippocampus from 2 hours to 5 days post ICH, although it was also elevated in the contralateral hippocampus to a lesser extent [142].

3.3. ROS Production

After hemorrhagic injury, hemolysis of red blood cells leads to hemoglobin degradation and iron deposition in the brain [143]. Excess iron causes lipid peroxidation and the formation of free radicals [144, 145]. The ROS, released by activated microglia and infiltrating leukocytes [146, 147], contribute to brain injury after ICH [18, 148–151]. It has been shown that activation of Nrf2, a transcriptional factor that regulates the expression of antioxidant enzymes, improves stroke outcomes in rodents [152, 153]. Consistently, lack of Nrf2 leads to more severe brain damage in both permanent and transient stroke models [152, 154]. In both collagenase and whole-blood ICH models, Nrf2−/− mice showed increased ROS production, cytochrome c release and neurological deficit, suggesting a detrimental role of ROS in ICH [155, 156]. In accordance with these observations, deferoxamine, an iron chelator, was neuroprotective in whole-blood ICH model in rats and piglets [25, 27, 157–159], although one study showed that it was not beneficial in collagenase ICH model in rats [160]. In the collagenase-induced ICH model in mice, deferoxamine is neuroprotective, although it does not reduce lesion volume and brain edema [161]. 2, 2’-dipyridyl, a lipid-soluble iron chelator, has been shown to be beneficial in both ICH models in mice [162]. In addition, serum ferritin level associates with penumbra edema in patients 3–4 days post spontaneous ICH [163] and high serum ferritin level also indicates poor outcomes [164].

4. Future directions

Recent studies from our lab and others suggest that early inhibition of inflammatory responses (such as microglia/macrophage activation, leukocyte infiltration, inflammatory mediator release) may be beneficial but long-term inhibition delays the recovery. The early beneficial role of lack of MCP1/CCL2 is probably due to decreased cytokine & chemokine secretion, leading to attenuated neuronal death. The delayed recovery, however, may be caused by the dysregulation of inflammatory response. The activation of alternative chemokine signaling pathways and overactivation/accumulation of microglia/macrophages may prolong the detrimental phase of inflammation or prevent the transition from detrimental phase to beneficial phase. Thus, further investigations should focus on the time course of MCP1/CCL2-CCR2 activation, the compensation of inhibiting MCP1/CCL2-CCR2 activation, and the potential molecular mechanisms regulating its expression. To validate the data from genetic modified animals, the effect of pharmacological inhibition of MCP1-CCR2 axis on ICH should also be examined. In addition, given that little data about ICH are generated using human postmortem brains and inflammatory signaling events may be different in rodents and humans (rodent MCP1 needs to be activated by plasmin, whereas human MCP1 does not), ICH studies using human brain samples are in great need. Last but not least, combination treatments targeting multiple biological processes could be beneficial and should be investigated.

Acknowledgements

We thank members of the Tsirka lab for helpful questions and contributions. This work was supported by a SigmaXi grant-in-aid (to YY) and NIH R0142168 (to SET). The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Ribo M and Grotta JC, Latest advances in intracerebral hemorrhage. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep, 2006. 6(1): p. 17–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Qureshi AI, Mendelow AD, and Hanley DF, Intracerebral haemorrhage. Lancet, 2009. 373(9675): p. 1632–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Broderick JP, Adams HP Jr., Barsan W, Feinberg W, Feldmann E, Grotta J, Kase C, Krieger D, Mayberg M, Tilley B, Zabramski JM, and Zuccarello M, Guidelines for the management of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage: A statement for healthcare professionals from a special writing group of the Stroke Council, American Heart Association. Stroke, 1999. 30(4): p. 905–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mayer SA and Rincon F, Treatment of intracerebral haemorrhage. Lancet Neurol, 2005. 4(10): p. 662–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sutherland GR and Auer RN, Primary intracerebral hemorrhage. J Clin Neurosci, 2006. 13(5): p. 511–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Qureshi AI, Suri MF, Ling GS, Khan J, Guterman LR, and Hopkins LN, Absence of early proinflammatory cytokine expression in experimental intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurosurgery, 2001. 49(2): p. 416–20; discussion 421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taylor CL, Selman WR, and Ratcheson RA, Brain attack. The emergent management of hypertensive hemorrhage. Neurosurg Clin N Am, 1997. 8(2): p. 237–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang X, Li H, Hu S, Zhang L, Liu C, Zhu C, Liu R, and Li C, Brain edema after intracerebral hemorrhage in rats: the role of inflammation. Neurol India, 2006. 54(4): p. 402–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang J and Dore S, Inflammation after intracerebral hemorrhage. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab, 2007. 27(5): p. 894–908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang J and Tsirka SE, Contribution of extracellular proteolysis and microglia to intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurocrit Care, 2005. 3(1): p. 77–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang J, Rogove AD, Tsirka AE, and Tsirka SE, Protective role of tuftsin fragment 1–3 in an animal model of intracerebral hemorrhage. Ann Neurol, 2003. 54(5): p. 655–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang J and Tsirka SE, Tuftsin fragment 1–3 is beneficial when delivered after the induction of intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke, 2005. 36(3): p. 613–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yao Y and Tsirka SE, Truncation of monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 by plasmin promotes blood-brain barrier disruption. J Cell Sci, 2011. 124(Pt 9): p. 1486–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stamatovic SM, Shakui P, Keep RF, Moore BB, Kunkel SL, Van Rooijen N, and Andjelkovic AV, Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 regulation of blood-brain barrier permeability. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab, 2005. 25(5): p. 593–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stamatovic SM, Keep RF, Kunkel SL, and Andjelkovic AV, Potential role of MCP-1 in endothelial cell tight junction ‘opening’: signaling via Rho and Rho kinase. J Cell Sci, 2003. 116(Pt 22): p. 4615–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lindsberg PJ, Strbian D, and Karjalainen-Lindsberg ML, Mast cells as early responders in the regulation of acute blood-brain barrier changes after cerebral ischemia and hemorrhage. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab, 2010. 30(4): p. 689–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Strbian D, Tatlisumak T, Ramadan UA, and Lindsberg PJ, Mast cell blocking reduces brain edema and hematoma volume and improves outcome after experimental intracerebral hemorrhage. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab, 2007. 27(4): p. 795–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aronowski J and Hall CE, New horizons for primary intracerebral hemorrhage treatment: experience from preclinical studies. Neurol Res, 2005. 27(3): p. 268–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tang J, Liu J, Zhou C, Alexander JS, Nanda A, Granger DN, and Zhang JH, Mmp-9 deficiency enhances collagenase-induced intracerebral hemorrhage and brain injury in mutant mice. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab, 2004. 24(10): p. 1133–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tejima E, Zhao BQ, Tsuji K, Rosell A, van Leyen K, Gonzalez RG, Montaner J, Wang X, and Lo EH, Astrocytic induction of matrix metalloproteinase-9 and edema in brain hemorrhage. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab, 2007. 27(3): p. 460–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wagner KR, Modeling intracerebral hemorrhage: glutamate, nuclear factor-kappa B signaling and cytokines. Stroke, 2007. 38(2 Suppl): p. 753–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yao Y and Tsirka S, The CCL2-CCR2 system affects the progression and clearance of intracerebral hemorrhage. Glia, 2012. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chu K, Jeong SW, Jung KH, Han SY, Lee ST, Kim M, and Roh JK, Celecoxib induces functional recovery after intracerebral hemorrhage with reduction of brain edema and perihematomal cell death. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab, 2004. 24(8): p. 926–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matsushita K, Meng W, Wang X, Asahi M, Asahi K, Moskowitz MA, and Lo EH, Evidence for apoptosis after intercerebral hemorrhage in rat striatum. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab, 2000. 20(2): p. 396–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gu Y, Hua Y, Keep RF, Morgenstern LB, and Xi G, Deferoxamine reduces intracerebral hematoma-induced iron accumulation and neuronal death in piglets. Stroke, 2009. 40(6): p. 2241–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koeppen AH, Dickson AC, and Smith J, Heme oxygenase in experimental intracerebral hemorrhage: the benefit of tin-mesoporphyrin. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol, 2004. 63(6): p. 587–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Okauchi M, Hua Y, Keep RF, Morgenstern LB, and Xi G, Effects of deferoxamine on intracerebral hemorrhage-induced brain injury in aged rats. Stroke, 2009. 40(5): p. 1858–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xue M, Hollenberg MD, and Yong VW, Combination of thrombin and matrix metalloproteinase-9 exacerbates neurotoxicity in cell culture and intracerebral hemorrhage in mice. J Neurosci, 2006. 26(40): p. 10281–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhao X, Sun G, Zhang J, Strong R, Song W, Gonzales N, Grotta JC, and Aronowski J, Hematoma resolution as a target for intracerebral hemorrhage treatment: role for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma in microglia/macrophages. Ann Neurol, 2007. 61(4): p. 352–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.MacLellan CL, Silasi G, Auriat AM, and Colbourne F, Rodent models of intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke, 2010. 41(10 Suppl): p. S95–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wakisaka Y, Chu Y, Miller JD, Rosenberg GA, and Heistad DD, Spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage during acute and chronic hypertension in mice. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab, 2010. 30(1): p. 56–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van Rossum D and Hanisch UK, Microglia. Metab Brain Dis, 2004. 19(3–4): p. 393–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhao X, Zhang Y, Strong R, Grotta JC, and Aronowski J, 15d-Prostaglandin J2 activates peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma, promotes expression of catalase, and reduces inflammation, behavioral dysfunction, and neuronal loss after intracerebral hemorrhage in rats. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab, 2006. 26(6): p. 811–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang J and Tsirka SE, Neuroprotection by inhibition of matrix metalloproteinases in a mouse model of intracerebral haemorrhage. Brain, 2005. 128(Pt 7): p. 1622–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gao Z, Wang J, Thiex R, Rogove AD, Heppner FL, and Tsirka SE, Microglial activation and intracerebral hemorrhage. Acta Neurochir Suppl, 2008. 105: p. 51–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miller RJ and Meucci O, AIDS and the brain: is there a chemokine connection? Trends Neurosci, 1999. 22(10): p. 471–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lahrtz F, Piali L, Spanaus KS, Seebach J, and Fontana A, Chemokines and chemotaxis of leukocytes in infectious meningitis. J Neuroimmunol, 1998. 85(1): p. 33–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Glabinski AR, Balasingam V, Tani M, Kunkel SL, Strieter RM, Yong VW, and Ransohoff RM, Chemokine monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 is expressed by astrocytes after mechanical injury to the brain. J Immunol, 1996. 156(11): p. 4363–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hulkower K, Brosnan CF, Aquino DA, Cammer W, Kulshrestha S, Guida MP, Rapoport DA, and Berman JW, Expression of CSF-1, c-fms, and MCP-1 in the central nervous system of rats with experimental allergic encephalomyelitis. J Immunol, 1993. 150(6): p. 2525–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Murphy PM, The molecular biology of leukocyte chemoattractant receptors. Annu Rev Immunol, 1994. 12: p. 593–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rollins BJ, Chemokines. Blood, 1997. 90(3): p. 909–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yoshie O, Imai T, and Nomiyama H, Novel lymphocyte-specific CC chemokines and their receptors. J Leukoc Biol, 1997. 62(5): p. 634–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tran PB and Miller RJ, Chemokine receptors: signposts to brain development and disease. Nat Rev Neurosci, 2003. 4(6): p. 444–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ransohoff RM, The chemokine system in neuroinflammation: an update. J Infect Dis, 2002. 186 Suppl 2: p. S152–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rosell A, Vilalta A, García-Berrocoso T, Fernández-Cadenas I, Domingues-Montanari S, Cuadrado E, Delgado P, Ribó M, Martínez-Sáez E, Ortega-Aznar A, and Montaner J, Brain perihematoma genomic profile following spontaneous human intracerebral hemorrhage. PLoS One, 2011. 6(2): p. e16750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Keep R, Xiang J, Ennis S, Andjelkovic A, Hua Y, Xi G, and Hoff J, Blood-brain barrier function in intracerebral hemorrhage. Acta Neurochir Suppl, 2008. 105: p. 73–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Carmichael S, Vespa P, Saver J, Coppola G, Geschwind D, Starkman S, Miller C, Kidwell C, Liebeskind D, and Martin N, Genomic profiles of damage and protection in human intracerebral hemorrhage. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab, 2008. 28(11): p. 1860–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mennicken F, Maki R, de Souza EB, and Quirion R, Chemokines and chemokine receptors in the CNS: a possible role in neuroinflammation and patterning. Trends Pharmacol Sci, 1999. 20(2): p. 73–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mahad DJ and Ransohoff RM, The role of MCP-1 (CCL2) and CCR2 in multiple sclerosis and experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE). Semin Immunol, 2003. 15(1): p. 23–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ransohoff RM, Hamilton TA, Tani M, Stoler MH, Shick HE, Major JA, Estes ML, Thomas DM, and Tuohy VK, Astrocyte expression of mRNA encoding cytokines IP-10 and JE/MCP-1 in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. FASEB J, 1993. 7(6): p. 592–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Horuk R, Martin AW, Wang Z, Schweitzer L, Gerassimides A, Guo H, Lu Z, Hesselgesser J, Perez HD, Kim J, Parker J, Hadley TJ, and Peiper SC, Expression of chemokine receptors by subsets of neurons in the central nervous system. J Immunol, 1997. 158(6): p. 2882–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Boddeke EW, Meigel I, Frentzel S, Gourmala NG, Harrison JK, Buttini M, Spleiss O, and Gebicke-Harter P, Cultured rat microglia express functional beta-chemokine receptors. J Neuroimmunol, 1999. 98(2): p. 176–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Andjelkovic AV, Kerkovich D, Shanley J, Pulliam L, and Pachter JS, Expression of binding sites for beta chemokines on human astrocytes. Glia, 1999. 28(3): p. 225–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Andjelkovic AV and Pachter JS, Characterization of binding sites for chemokines MCP-1 and MIP-1alpha on human brain microvessels. J Neurochem, 2000. 75(5): p. 1898–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Andjelkovic AV, Spencer DD, and Pachter JS, Visualization of chemokine binding sites on human brain microvessels. J Cell Biol, 1999. 145(2): p. 403–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kalehua AN, Nagel JE, Whelchel LM, Gides JJ, Pyle RS, Smith RJ, Kusiak JW, and Taub DD, Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 and macrophage inflammatory protein-2 are involved in both excitotoxin-induced neurodegeneration and regeneration. Exp Cell Res, 2004. 297(1): p. 197–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Meeuwsen S, Bsibsi M, Persoon-Deen C, Ravid R, and van Noort JM, Cultured human adult microglia from different donors display stable cytokine, chemokine and growth factor gene profiles but respond differently to a pro-inflammatory stimulus. Neuroimmunomodulation, 2005. 12(4): p. 235–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mahajan SD, Schwartz SA, Aalinkeel R, Chawda RP, Sykes DE, and Nair MP, Morphine modulates chemokine gene regulation in normal human astrocytes. Clin Immunol, 2005. 115(3): p. 323–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zeng HY, Zhu XA, Zhang C, Yang LP, Wu LM, and Tso MO, Identification of sequential events and factors associated with microglial activation, migration, and cytotoxicity in retinal degeneration in rd mice. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, 2005. 46(8): p. 2992–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Banisadr G, Gosselin RD, Mechighel P, Kitabgi P, Rostene W, and Parsadaniantz SM, Highly regionalized neuronal expression of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1/CCL2) in rat brain: evidence for its colocalization with neurotransmitters and neuropeptides. J Comp Neurol, 2005. 489(3): p. 275–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dicou E, Vincent JP, and Mazella J, Neurotensin receptor-3/sortilin mediates neurotensin-induced cytokine/chemokine expression in a murine microglial cell line. J Neurosci Res, 2004. 78(1): p. 92–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Storer PD, Xu J, Chavis J, and Drew PD, Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma agonists inhibit the activation of microglia and astrocytes: implications for multiple sclerosis. J Neuroimmunol, 2005. 161(1–2): p. 113–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wittendorp MC, Boddeke HW, and Biber K, Adenosine A3 receptor-induced CCL2 synthesis in cultured mouse astrocytes. Glia, 2004. 46(4): p. 410–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nimmerjahn A, Kirchhoff F, and Helmchen F, Resting microglial cells are highly dynamic surveillants of brain parenchyma in vivo. Science, 2005. 308(5726): p. 1314–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Abromson-Leeman S, Hayashi M, Martin C, Sobel R, al-Sabbagh A, Weiner H, and Dorf ME, T cell responses to myelin basic protein in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis-resistant BALB/c mice. J Neuroimmunol, 1993. 45(1–2): p. 89–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ulvestad E, Williams K, Bjerkvig R, Tiekotter K, Antel J, and Matre R, Human microglial cells have phenotypic and functional characteristics in common with both macrophages and dendritic antigen-presenting cells. J Leukoc Biol, 1994. 56(6): p. 732–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Aloisi F, Immune function of microglia. Glia, 2001. 36(2): p. 165–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nakajima K and Kohsaka S, Microglia: neuroprotective and neurotrophic cells in the central nervous system. Curr Drug Targets Cardiovasc Haematol Disord, 2004. 4(1): p. 65–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kim SU and de Vellis J, Microglia in health and disease. J Neurosci Res, 2005. 81(3): p. 302–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hanisch UK and Kettenmann H, Microglia: active sensor and versatile effector cells in the normal and pathologic brain. Nat Neurosci, 2007. 10(11): p. 1387–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Frangogiannis NG, Dewald O, Xia Y, Ren G, Haudek S, Leucker T, Kraemer D, Taffet G, Rollins BJ, and Entman ML, Critical role of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1/CC chemokine ligand 2 in the pathogenesis of ischemic cardiomyopathy. Circulation, 2007. 115(5): p. 584–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dimitrijevic OB, Stamatovic SM, Keep RF, and Andjelkovic AV, Effects of the chemokine CCL2 on blood-brain barrier permeability during ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab, 2006. 26(6): p. 797–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yan YP, Sailor KA, Lang BT, Park SW, Vemuganti R, and Dempsey RJ, Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 plays a critical role in neuroblast migration after focal cerebral ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab, 2007. 27(6): p. 1213–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Morimoto H, Hirose M, Takahashi M, Kawaguchi M, Ise H, Kolattukudy PE, Yamada M, and Ikeda U, MCP-1 induces cardioprotection against ischaemia/reperfusion injury: role of reactive oxygen species. Cardiovasc Res, 2008. 78(3): p. 554–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kim GH, Kellner CP, Hahn DK, Desantis BM, Musabbir M, Starke RM, Rynkowski M, Komotar RJ, Otten ML, Sciacca R, Schmidt JM, Mayer SA, and Connolly ES Jr., Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 predicts outcome and vasospasm following aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurosurg, 2008. 109(1): p. 38–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sheehan JJ, Zhou C, Gravanis I, Rogove AD, Wu YP, Bogenhagen DF, and Tsirka SE, Proteolytic activation of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 by plasmin underlies excitotoxic neurodegeneration in mice. J Neurosci, 2007. 27(7): p. 1738–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Capoccia BJ, Gregory AD, and Link DC, Recruitment of the inflammatory subset of monocytes to sites of ischemia induces angiogenesis in a monocyte chemoattractant protein-1-dependent fashion. J Leukoc Biol, 2008. 84(3): p. 760–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.El Khoury J, Toft M, Hickman SE, Means TK, Terada K, Geula C, and Luster AD, Ccr2 deficiency impairs microglial accumulation and accelerates progression of Alzheimer-like disease. Nat Med, 2007. 13(4): p. 432–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Chen BP, Kuziel WA, and Lane TE, Lack of CCR2 results in increased mortality and impaired leukocyte activation and trafficking following infection of the central nervous system with a neurotropic coronavirus. J Immunol, 2001. 167(8): p. 4585–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Galasso JM, Liu Y, Szaflarski J, Warren JS, and Silverstein FS, Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 is a mediator of acute excitotoxic injury in neonatal rat brain. Neuroscience, 2000. 101(3): p. 737–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Tsirka SE, Rogove AD, Bugge TH, Degen JL, and Strickland S, An extracellular proteolytic cascade promotes neuronal degeneration in the mouse hippocampus. J Neurosci, 1997. 17(2): p. 543–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Tsirka SE, Gualandris A, Amaral DG, and Strickland S, Excitotoxin-induced neuronal degeneration and seizure are mediated by tissue plasminogen activator. Nature, 1995. 377(6547): p. 340–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yao Y and Tsirka SE, The C terminus of mouse monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP1) mediates MCP1 dimerization while blocking its chemotactic potency. J Biol Chem, 2010. 285(41): p. 31509–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Gong JH, Ratkay LG, Waterfield JD, and Clark-Lewis I, An antagonist of monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP-1) inhibits arthritis in the MRL-lpr mouse model. J Exp Med, 1997. 186(1): p. 131–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gouwy M, Struyf S, Catusse J, Proost P, and Van Damme J, Synergy between proinflammatory ligands of G protein-coupled receptors in neutrophil activation and migration. J Leukoc Biol, 2004. 76(1): p. 185–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wain JH, Kirby JA, and Ali S, Leucocyte chemotaxis: Examination of mitogen-activated protein kinase and phosphoinositide 3-kinase activation by Monocyte Chemoattractant Proteins-1, −2, −3 and −4. Clin Exp Immunol, 2002. 127(3): p. 436–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Gerard C and Rollins BJ, Chemokines and disease. Nat Immunol, 2001. 2(2): p. 108–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Charo IF and Ransohoff RM, The many roles of chemokines and chemokine receptors in inflammation. N Engl J Med, 2006. 354(6): p. 610–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Charo IF, Myers SJ, Herman A, Franci C, Connolly AJ, and Coughlin SR, Molecular cloning and functional expression of two monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 receptors reveals alternative splicing of the carboxyl-terminal tails. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 1994. 91(7): p. 2752–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Geissmann F, Jung S, and Littman DR, Blood monocytes consist of two principal subsets with distinct migratory properties. Immunity, 2003. 19(1): p. 71–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Sozzani S, Luini W, Borsatti A, Polentarutti N, Zhou D, Piemonti L, D’Amico G, Power CA, Wells TN, Gobbi M, Allavena P, and Mantovani A, Receptor expression and responsiveness of human dendritic cells to a defined set of CC and CXC chemokines. J Immunol, 1997. 159(4): p. 1993–2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Loetscher P, Seitz M, Baggiolini M, and Moser B, Interleukin-2 regulates CC chemokine receptor expression and chemotactic responsiveness in T lymphocytes. J Exp Med, 1996. 184(2): p. 569–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Banisadr G, Gosselin RD, Mechighel P, Rostene W, Kitabgi P, and Melik Parsadaniantz S, Constitutive neuronal expression of CCR2 chemokine receptor and its colocalization with neurotransmitters in normal rat brain: functional effect of MCP-1/CCL2 on calcium mobilization in primary cultured neurons. J Comp Neurol, 2005. 492(2): p. 178–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Banisadr G, Queraud-Lesaux F, Boutterin MC, Pelaprat D, Zalc B, Rostene W, Haour F, and Parsadaniantz SM, Distribution, cellular localization and functional role of CCR2 chemokine receptors in adult rat brain. J Neurochem, 2002. 81(2): p. 257–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Coughlan CM, McManus CM, Sharron M, Gao Z, Murphy D, Jaffer S, Choe W, Chen W, Hesselgesser J, Gaylord H, Kalyuzhny A, Lee VM, Wolf B, Doms RW, and Kolson DL, Expression of multiple functional chemokine receptors and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 in human neurons. Neuroscience, 2000. 97(3): p. 591–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Gourmala NG, Buttini M, Limonta S, Sauter A, and Boddeke HW, Differential and time-dependent expression of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 mRNA by astrocytes and macrophages in rat brain: effects of ischemia and peripheral lipopolysaccharide administration. J Neuroimmunol, 1997. 74(1–2): p. 35–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ge S, Song L, Serwanski DR, Kuziel WA, and Pachter JS, Transcellular transport of CCL2 across brain microvascular endothelial cells. J Neurochem, 2008. 104(5): p. 1219–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Andjelkovic AV, Song L, Dzenko KA, Cong H, and Pachter JS, Functional expression of CCR2 by human fetal astrocytes. J Neurosci Res, 2002. 70(2): p. 219–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Croitoru-Lamoury J, Guillemin GJ, Boussin FD, Mognetti B, Gigout LI, Cheret A, Vaslin B, Le Grand R, Brew BJ, and Dormont D, Expression of chemokines and their receptors in human and simian astrocytes: evidence for a central role of TNF alpha and IFN gamma in CXCR4 and CCR5 modulation. Glia, 2003. 41(4): p. 354–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.White FA, Sun J, Waters SM, Ma C, Ren D, Ripsch M, Steflik J, Cortright DN, Lamotte RH, and Miller RJ, Excitatory monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 signaling is up-regulated in sensory neurons after chronic compression of the dorsal root ganglion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2005. 102(39): p. 14092–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Mahad D, Callahan MK, Williams KA, Ubogu EE, Kivisakk P, Tucky B, Kidd G, Kingsbury GA, Chang A, Fox RJ, Mack M, Sniderman MB, Ravid R, Staugaitis SM, Stins MF, and Ransohoff RM, Modulating CCR2 and CCL2 at the blood-brain barrier: relevance for multiple sclerosis pathogenesis. Brain, 2006. 129(Pt 1): p. 212–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Tylaska LA, Boring L, Weng W, Aiello R, Charo IF, Rollins BJ, and Gladue RP, Ccr2 regulates the level of MCP-1/CCL2 in vitro and at inflammatory sites and controls T cell activation in response to alloantigen. Cytokine, 2002. 18(4): p. 184–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Zhang Y and Rollins BJ, A dominant negative inhibitor indicates that monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 functions as a dimer. Mol Cell Biol, 1995. 15(9): p. 4851–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Stamatovic SM, Dimitrijevic OB, Keep RF, and Andjelkovic AV, Protein kinase Calpha-RhoA cross-talk in CCL2-induced alterations in brain endothelial permeability. J Biol Chem, 2006. 281(13): p. 8379–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Yao Y and Tsirka SE, Mouse MCP1 C-terminus inhibits human MCP1-induced chemotaxis and BBB compromise. J Neurochem, 2011. 118(2): p. 215–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Bartoli C, Civatte M, Pellissier JF, and Figarella-Branger D, CCR2A and CCR2B, the two isoforms of the monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 receptor are up-regulated and expressed by different cell subsets in idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. Acta Neuropathol, 2001. 102(4): p. 385–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Broderick J, Connolly S, Feldmann E, Hanley D, Kase C, Krieger D, Mayberg M, Morgenstern L, Ogilvy CS, Vespa P, and Zuccarello M, Guidelines for the management of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage in adults: 2007 update: a guideline from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Stroke Council, High Blood Pressure Research Council, and the Quality of Care and Outcomes in Research Interdisciplinary Working Group. Stroke, 2007. 38(6): p. 2001–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Morgenstern LB, Frankowski RF, Shedden P, Pasteur W, and Grotta JC, Surgical treatment for intracerebral hemorrhage (STICH): a single-center, randomized clinical trial. Neurology, 1998. 51(5): p. 1359–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Wang J and Dore S, Heme oxygenase-1 exacerbates early brain injury after intracerebral haemorrhage. Brain, 2007. 130(Pt 6): p. 1643–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Wang J and Dore S, Heme oxygenase 2 deficiency increases brain swelling and inflammation after intracerebral hemorrhage. Neuroscience, 2008. 155(4): p. 1133–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Xue M and Del Bigio MR, Intracerebral injection of autologous whole blood in rats: time course of inflammation and cell death. Neurosci Lett, 2000. 283(3): p. 230–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Gong C, Hoff JT, and Keep RF, Acute inflammatory reaction following experimental intracerebral hemorrhage in rat. Brain Res, 2000. 871(1): p. 57–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Keep RF, Xi G, Hua Y, and Hoff JT, The deleterious or beneficial effects of different agents in intracerebral hemorrhage: think big, think small, or is hematoma size important? Stroke, 2005. 36(7): p. 1594–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Yong VW, Wells J, Giuliani F, Casha S, Power C, and Metz LM, The promise of minocycline in neurology. Lancet Neurol, 2004. 3(12): p. 744–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Wasserman JK and Schlichter LC, Minocycline protects the blood-brain barrier and reduces edema following intracerebral hemorrhage in the rat. Exp Neurol, 2007. 207(2): p. 227–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Power C, Henry S, Del Bigio MR, Larsen PH, Corbett D, Imai Y, Yong VW, and Peeling J, Intracerebral hemorrhage induces macrophage activation and matrix metalloproteinases. Ann Neurol, 2003. 53(6): p. 731–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Wu J, Yang S, Xi G, Fu G, Keep RF, and Hua Y, Minocycline reduces intracerebral hemorrhage-induced brain injury. Neurol Res, 2009. 31(2): p. 183–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Xue M, Mikliaeva EI, Casha S, Zygun D, Demchuk A, and Yong VW, Improving outcomes of neuroprotection by minocycline: guides from cell culture and intracerebral hemorrhage in mice. Am J Pathol, 2010. 176(3): p. 1193–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Peeling J, Yan HJ, Corbett D, Xue M, and Del Bigio MR, Effect of FK-506 on inflammation and behavioral outcome following intracerebral hemorrhage in rat. Exp Neurol, 2001. 167(2): p. 341–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Mackenzie JM and Clayton JA, Early cellular events in the penumbra of human spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis, 1999. 8(1): p. 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Guo FQ, Li XJ, Chen LY, Yang H, Dai HY, Wei YS, Huang YL, Yang YS, Sun HB, Xu YC, and Yang ZL, [Study of relationship between inflammatory response and apoptosis in perihematoma region in patients with intracerebral hemorrhage]. Zhongguo Wei Zhong Bing Ji Jiu Yi Xue, 2006. 18(5): p. 290–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Leira R, Davalos A, Silva Y, Gil-Peralta A, Tejada J, Garcia M, and Castillo J, Early neurologic deterioration in intracerebral hemorrhage: predictors and associated factors. Neurology, 2004. 63(3): p. 461–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Silva Y, Leira R, Tejada J, Lainez JM, Castillo J, and Davalos A, Molecular signatures of vascular injury are associated with early growth of intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke, 2005. 36(1): p. 86–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Nguyen HX, O’Barr TJ, and Anderson AJ, Polymorphonuclear leukocytes promote neurotoxicity through release of matrix metalloproteinases, reactive oxygen species, and TNF-alpha. J Neurochem, 2007. 102(3): p. 900–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Joice SL, Mydeen F, Couraud PO, Weksler BB, Romero IA, Fraser PA, and Easton AS, Modulation of blood-brain barrier permeability by neutrophils: in vitro and in vivo studies. Brain Res, 2009. 1298: p. 13–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Titova E, Ostrowski RP, Kevil CG, Tong W, Rojas H, Sowers LC, Zhang JH, and Tang J, Reduced brain injury in CD18-deficient mice after experimental intracerebral hemorrhage. J Neurosci Res, 2008. 86(14): p. 3240–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Rosenberg GA and Navratil M, Metalloproteinase inhibition blocks edema in intracerebral hemorrhage in the rat. Neurology, 1997. 48(4): p. 921–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Lee JM, Yin KJ, Hsin I, Chen S, Fryer JD, Holtzman DM, Hsu CY, and Xu J, Matrix metalloproteinase-9 and spontaneous hemorrhage in an animal model of cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Ann Neurol, 2003. 54(3): p. 379–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Lu A, Tang Y, Ran R, Ardizzone TL, Wagner KR, and Sharp FR, Brain genomics of intracerebral hemorrhage. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab, 2006. 26(2): p. 230–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Mun-Bryce S, Wilkerson A, Pacheco B, Zhang T, Rai S, Wang Y, and Okada Y, Depressed cortical excitability and elevated matrix metalloproteinases in remote brain regions following intracerebral hemorrhage. Brain Res, 2004. 1026(2): p. 227–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Wu H, Zhang Z, Li Y, Zhao R, Li H, Song Y, Qi J, and Wang J, Time course of upregulation of inflammatory mediators in the hemorrhagic brain in rats: correlation with brain edema. Neurochem Int, 2010. 57(3): p. 248–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Wells JE, Biernaskie J, Szymanska A, Larsen PH, Yong VW, and Corbett D, Matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-12 expression has a negative impact on sensorimotor function following intracerebral haemorrhage in mice. Eur J Neurosci, 2005. 21(1): p. 187–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Xue M, Fan Y, Liu S, Zygun DA, Demchuk A, and Yong VW, Contributions of multiple proteases to neurotoxicity in a mouse model of intracerebral haemorrhage. Brain, 2009. 132(Pt 1): p. 26–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Xue M, Hollenberg MD, Demchuk A, and Yong VW, Relative importance of proteinase-activated receptor-1 versus matrix metalloproteinases in intracerebral hemorrhage-mediated neurotoxicity in mice. Stroke, 2009. 40(6): p. 2199–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Wasserman JK and Schlichter LC, Neuron death and inflammation in a rat model of intracerebral hemorrhage: effects of delayed minocycline treatment. Brain Res, 2007. 1136(1): p. 208–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Szymanska A, Biernaskie J, Laidley D, Granter-Button S, and Corbett D, Minocycline and intracerebral hemorrhage: influence of injury severity and delay to treatment. Exp Neurol, 2006. 197(1): p. 189–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Abilleira S, Montaner J, Molina CA, Monasterio J, Castillo J, and Alvarez-Sabin J, Matrix metalloproteinase-9 concentration after spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. J Neurosurg, 2003. 99(1): p. 65–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Alvarez-Sabin J, Delgado P, Abilleira S, Molina CA, Arenillas J, Ribo M, Santamarina E, Quintana M, Monasterio J, and Montaner J, Temporal profile of matrix metalloproteinases and their inhibitors after spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage: relationship to clinical and radiological outcome. Stroke, 2004. 35(6): p. 1316–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Castellazzi M, Tamborino C, De Santis G, Garofano F, Lupato A, Ramponi V, Trentini A, Casetta I, Bellini T, and Fainardi E, Timing of serum active MMP-9 and MMP-2 levels in acute and subacute phases after spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. Acta Neurochir Suppl, 2010. 106: p. 137–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Barr TL, Latour LL, Lee KY, Schaewe TJ, Luby M, Chang GS, El-Zammar Z, Alam S, Hallenbeck JM, Kidwell CS, and Warach S, Blood-brain barrier disruption in humans is independently associated with increased matrix metalloproteinase-9. Stroke, 2010. 41(3): p. e123–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Rosell A, Ortega-Aznar A, Alvarez-Sabin J, Fernandez-Cadenas I, Ribo M, Molina CA, Lo EH, and Montaner J, Increased brain expression of matrix metalloproteinase-9 after ischemic and hemorrhagic human stroke. Stroke, 2006. 37(6): p. 1399–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Wu H, Zhang Z, Hu X, Zhao R, Song Y, Ban X, Qi J, and Wang J, Dynamic changes of inflammatory markers in brain after hemorrhagic stroke in humans: a postmortem study. Brain Res, 2010. 1342: p. 111–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Wu J, Hua Y, Keep RF, Nakamura T, Hoff JT, and Xi G, Iron and iron-handling proteins in the brain after intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke, 2003. 34(12): p. 2964–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Gutteridge JM, Hydroxyl radicals, iron, oxidative stress, and neurodegeneration. Ann N Y Acad Sci, 1994. 738: p. 201–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Zecca L, Youdim MB, Riederer P, Connor JR, and Crichton RR, Iron, brain ageing and neurodegenerative disorders. Nat Rev Neurosci, 2004. 5(11): p. 863–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Facchinetti F, Dawson VL, and Dawson TM, Free radicals as mediators of neuronal injury. Cell Mol Neurobiol, 1998. 18(6): p. 667–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Weiss SJ, Tissue destruction by neutrophils. N Engl J Med, 1989. 320(6): p. 365–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Green AR and Ashwood T, Free radical trapping as a therapeutic approach to neuroprotection in stroke: experimental and clinical studies with NXY-059 and free radical scavengers. Curr Drug Targets CNS Neurol Disord, 2005. 4(2): p. 109–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Wagner KR, Sharp FR, Ardizzone TD, Lu A, and Clark JF, Heme and iron metabolism: role in cerebral hemorrhage. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab, 2003. 23(6): p. 629–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Xi G, Keep RF, and Hoff JT, Mechanisms of brain injury after intracerebral haemorrhage. Lancet Neurol, 2006. 5(1): p. 53–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Hua Y, Keep RF, Hoff JT, and Xi G, Brain injury after intracerebral hemorrhage: the role of thrombin and iron. Stroke, 2007. 38(2 Suppl): p. 759–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Shih AY, Li P, and Murphy TH, A small-molecule-inducible Nrf2-mediated antioxidant response provides effective prophylaxis against cerebral ischemia in vivo. J Neurosci, 2005. 25(44): p. 10321–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Zhao J, Kobori N, Aronowski J, and Dash PK, Sulforaphane reduces infarct volume following focal cerebral ischemia in rodents. Neurosci Lett, 2006. 393(2–3): p. 108–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Shah ZA, Li RC, Thimmulappa RK, Kensler TW, Yamamoto M, Biswal S, and Dore S, Role of reactive oxygen species in modulation of Nrf2 following ischemic reperfusion injury. Neuroscience, 2007. 147(1): p. 53–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Wang J, Fields J, Zhao C, Langer J, Thimmulappa RK, Kensler TW, Yamamoto M, Biswal S, and Dore S, Role of Nrf2 in protection against intracerebral hemorrhage injury in mice. Free Radic Biol Med, 2007. 43(3): p. 408–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Zhao X, Sun G, Zhang J, Strong R, Dash PK, Kan YW, Grotta JC, and Aronowski J, Transcription factor Nrf2 protects the brain from damage produced by intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke, 2007. 38(12): p. 3280–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Hua Y, Nakamura T, Keep RF, Wu J, Schallert T, Hoff JT, and Xi G, Long-term effects of experimental intracerebral hemorrhage: the role of iron. J Neurosurg, 2006. 104(2): p. 305–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Nakamura T, Keep RF, Hua Y, Schallert T, Hoff JT, and Xi G, Deferoxamine-induced attenuation of brain edema and neurological deficits in a rat model of intracerebral hemorrhage. J Neurosurg, 2004. 100(4): p. 672–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Song S, Hua Y, Keep RF, Hoff JT, and Xi G, A new hippocampal model for examining intracerebral hemorrhage-related neuronal death: effects of deferoxamine on hemoglobin-induced neuronal death. Stroke, 2007. 38(10): p. 2861–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Warkentin LM, Auriat AM, Wowk S, and Colbourne F, Failure of deferoxamine, an iron chelator, to improve outcome after collagenase-induced intracerebral hemorrhage in rats. Brain Res, 2010. 1309: p. 95–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Wu H, Wu T, Xu X, Wang J, and Wang J, Iron toxicity in mice with collagenase-induced intracerebral hemorrhage. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab, 2011. 31(5): p. 1243–1250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Wu H, Wu T, Li M, and Wang J, Efficacy of the lipid-soluble iron chelator 2,2’-dipyridyl against hemorrhagic brain injury. Neurobiol Dis, 2012. 45(1): p. 388–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Mehdiratta M, Kumar S, Hackney D, Schlaug G, and Selim M, Association between serum ferritin level and perihematoma edema volume in patients with spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke, 2008. 39(4): p. 1165–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Perez de la Ossa N, Sobrino T, Silva Y, Blanco M, Millan M, Gomis M, Agulla J, Araya P, Reverte S, Serena J, and Davalos A, Iron-related brain damage in patients with intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke, 2010. 41(4): p. 810–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]