Abstract

The Experiences in Close Relationship Scale (ECR) is one of the most commonly used self-report instruments of adult attachment and has been widely adopted in psychotherapy research. Composed of two subscales, namely Attachment Avoidance and Anxiety, the ECR was recently shortened to a 12-items version, called the ECR-12. Given the importance of extending knowledge on its applicability in understudied populations, our aim was to validate the ECR-12 in a large sample of Italian native-speakers. A total of 1197 participants (73.2% females; mean age=28.53±11.37 years) completed the ECR-12. Each participant also completed other measures of attachment, psychopathology, interpersonal distress, coping strategies, and well-being. An Exploratory Structural Equation Modeling analysis showed an excellent fit of the data, providing support for the two-dimensional orthogonal structure of the ECR-12. In addition, the measurement model was invariant across genders. Both attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance subscales demonstrated good internal reliability, with McDonald’s Omegas and Cronbach’s Alphas above the suggested 0.8 cut-off. Finally, the Italian version of ECR-12 showed adequate convergent, concurrent, and divergent validity. Highly anxious individuals reported the highest levels of maladaptive interpersonal functioning and coping strategies, resulting in lower well-being. Interestingly, both attachment insecurity dimensions predicted higher levels of psychopathology, even after controlling for demographic variables and levels of self-reported relational difficulties. Given the good psychometric properties of the ECR-12, researchers and practitioners in Italy are encouraged to adopt the ECR-12 in their future research on adult attachment in psychotherapy.

Key words: Attachment anxiety, Attachment avoidance, ECR- 12, Psychological distress, Coping styles

Introduction

Attachment theory provides one of the most ecological and scientifically sound frameworks for understanding normal human and psychopathological development (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2016). According to the attachment theory, newborns have an innate predisposition to interact and form an emotional bond with primary caregivers, which support them during environmental exploration and provide comfort during potentially stressful or threatening situations (Bowlby, 1969). These interactions with caregivers, combined with genetic factors, influence the quality of the so-called internal working models (IWM) of attachment of the individual (Bowlby, 1980) and ultimately lead to the development of a secure or an insecure attachment (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2016). IWMs are cognitive-affective schemas that are relatively stable throughout life span (Chris Fraley, 2002; Waters, Merrick, Treboux, Crowell, & Albersheim, 2000) and are used to interpret the present, appraise and guide behavior during new situations, and plan future actions (Bretherton, 1985). Thus, IWMs influence self-concept, the way individuals will cope with stressors and regulate emotions, their expectations about future attachment relationships, and how they will relate with romantic partners, especially in stressful/threatening situations (Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters, & Wall, 1978; Mikulincer & Shaver, 2016; Simpson & Rholes, 2017; Wedding & Eisenman, 2006).

Individuals who experienced consistent and sensitive parenting during their childhood will develop a secure attachment style, characterized by good internal working models both of the self and their attachment figures, and by a positive sense of self-worth and self-competence (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2016). In addition, an individual with a secure attachment will be able to establish intimate, caring relationships with others (Bartholomew & Horowitz, 1991; Simpson & Rholes, 2018). Conversely, individuals who experienced repeated damaging interactions with inconsistent and/or unresponsive caregivers will develop an insecure attachment, characterized by negative internal working models of the self and others.

Attachment insecurity is classified into two main dimensions, namely attachment avoidance and attachment anxiety (Bartholomew & Horowitz, 1991; Brennan, Clark, & Shaver, 1998). Highly avoidant individuals are characterized by a fear of intimacy and discomfort with closeness (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2016). These individuals tend to establish and maintain independence, control, and autonomy, as well as deactivate emotions and limit emotional experiences during their everyday life and in romantic relationships (Cassidy & Kobak, 1988; Simpson & Rholes, 2018). When exposed to stress, those with an avoidant attachment maintain their autonomy, adopting distancing/deactivating coping strategies aimed at suppressing negative thoughts/emotions and attachment needs (Pascuzzo, Cyr, & Moss, 2013; Simpson & Rholes, 2018). On the contrary, highly anxious individuals have difficulty trusting others (with frequent fears of abandonment or rejection) and regulating their negative emotions (Mikulincer, 1995). They are anxiously entangled in their relationships: scared of being abandoned, they strongly desire to become emotionally closer to their partners in order to feel more secure (Simpson & Rholes, 2018). Furthermore, they usually respond to stressful events adopting emotion-focused or hyper-activating coping strategies, which sustain or escalate their worries and keep their attachment systems activated (Pascuzzo et al., 2013; Simpson & Rholes, 2018).

Due to its deep implications for self-identity, intimate relationships, and vulnerability to psychopathology, adult attachment has been extensively investigated over the past few decades (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2012). For example, research suggests that both insecure attachment dimensions are associated with psychological and marital distress, poor mental health and well-being, maladaptive coping strategies, dysregulated physiological responses to stress, risky health behaviours, and an increased susceptibility to physical illness (DiFilippo & Overholser, 2000; Donarelli, Kivlighan, Allegra, & Lo Coco, 2016; Feeney & Fitzgerald, 2018; Karreman & Vingerhoets, 2012; Mikulincer & Shaver, 2012; Pietromonaco & Beck, 2018; Rosenstein & Horowitz, 1996; Simpson & Rholes, 2018). Further, both insecure attachment dimensions are also associated with dyadic adjustment, parenting self-esteem (Calvo & Bianco, 2015), and caregiving styles (De Carli, Tagini, Sarracino, Santona, & Parolin, 2016). It is also worth noting that attachment theory has influenced several areas of psychotherapy research and clinical practice. From a theoretical perspective, a responsive therapist provides a secure base for exploration, helping patients develop a greater self-understanding through which to explore painful memories and emotions and to revise both MOIs of self and others (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2016). Secure therapists are less likely to react defensively and/or with negative countertransference, which is more efficacious for treating highly impaired and distressed clients than high functioning clients (Strauss & Petrowski, 2017). Moreover, therapists’ internalized relational models can directly or indirectly affect the quality of the therapeutic relationship, with insecurely attached therapists experiencing more problems in the therapy and weaker alliances compared to the securely attached therapists (Steel, Macdonald, & Schroder, 2018). Finally, there is growing research which suggests that attachment security may increase following therapy, whereas attachment anxiety decreases following therapy (Taylor, Rietzschel, Danquah, & Berry, 2015).

In response, researchers have developed several selfreport questionnaires to evaluate the conscious aspects of adult attachment (Ravitz, Maunder, Hunter, Sthankiya, & Lancee, 2010). For example, the Attachment Style Questionnaire (ASQ; Feeney, Noller, & Hanrahan, 1994) and the Experiences in Close Relationships (ECR; Brennan et al., 1998) are two of the most commonly-used instruments in research and clinical settings. The ASQ is a 40-item questionnaire composed of five subscales, namely Confidence (in self and others), Discomfort with Closeness, Need for Approval and Confirmation by Others, Preoccupation with Relationships, and Viewing Relationships as Secondary (Feeney et al., 1994). The ECR is a 36-item self-report measure of attachment dimensions in romantic relationships, which was originally developed by Brennan, Clark, and Shaver in 1998 following a factorial analysis of 323 attachment items (from 60 self-report measures of attachment) administered to a large sample of university students (Ravitz et al., 2010). Authors identified two relatively orthogonal dimensions, namely attachment Anxiety (concerning rejection or abandonment), and attachment Avoidance (of intimacy and interdependence in close relationships; (Brennan et al., 1998). Among the original 323 items, Brennan et al. (1998) retained 18 items with the highest loadings on each factor. Due to its utility across various clinical and non-clinical settings, as well as its good psychometric properties, the ECR reached a global consensus (Ravitz et al., 2010): it is considered one of the most methodologically-sound instruments to evaluate adult attachment. As a result, the scale was successfully translated and validated into multiple languages, including Italian (Picardi, Bitetti, Puddu, & Pasquini, 2000), French (Lafontaine & Lussier, 2003) and Spanish (Alonso-Arbiol, Balluerka, & Shaver, 2007). Later, Fraley, Waller, and Brennan (2000) revised the questionnaire using item-response theory (IRT) to develop the ECR-R (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2016). The attachment dimensions of ECR-R are strongly related to each other, compared to those of the original ECR (Cameron, Finnegan, & Morry, 2012).

The length of the original 36-item ECR can be problematic in some research areas and clinical settings. As such, there is a strong desire among researchers for a shorter, yet highly reliable version based on the best discriminating items. Indeed, short-forms have the advantage of increasing participants’ motivation to respond to the questionnaire, reducing fatigue and boredom (Lafontaine et al., 2016). Furthermore, short-forms are very useful in large-sample survey research, reducing the total number of items a participant has to complete, thus increasing research compliance rates. A recent, methodologically-sound short form of the ECR is the ECR-12 (Lafontaine et al., 2016), which was developed via IRT analyses on the original 36- item questionnaire. The IRT method used item-level information to select the most informative items, which allowed the resulting short-form to maintain good content validity (Embretson & Steven, 2000). In addition, IRT selected items based on their ability to discriminate well between people, and to assess the various levels of the constructs (Embretson & Steven, 2000). The ECR-12 retains the two original (and orthogonal) dimensions, namely Attachment Anxiety and Attachment Avoidance, each composed of 6 items. The questionnaire has been validated with different clinical and non-clinical English-speaking samples (Lafontaine et al., 2016; Tasca et al., 2018). For example, Tasca et al. (2018) evaluated the construct validity and the invariance of ECR-12 across five Eating Disorder diagnostic groups, with results supporting the original two-factor structure. However, due to its recent development, validation in other languages is still lacking.

As suggested by Messick (1989), factorial structures and reliability of psychometric tests cannot be generalized to other populations, such as those with a different language and socio-economic status. Therefore, the current study aimed to provide some evidence of the cross-cultural generalizability of the psychometric properties of the ECR-12 in a large non-clinical sample of Italian-speaking adults. Specifically, we hypothesized that the Italian version of ECR-12 will i) demonstrate adequate construct validity, such that its two-factor structure and item-factor loadings will fit the data well. Accordingly, we examined the two-factor structure of the ECR-12 through Confirmatory Factorial Analysis (CFA) and Exploratory Structural Equation Modelling (ESEM), as recommended by Marsh et al. (2009). We also hypothesized that the ERC- 12 subscales will have ii) good internal consistency reliability, iii) adequate convergent validity, demonstrated through moderately positive correlations with other measures of attachment, and iv) will demonstrate concurrent and divergent validity, being negatively associated with well-being and positively associated with the level of selfreported interpersonal problems and coping styles. In addition, we hypothesized that v) both ECR-12 attachment dimensions will be associated with the presence of significant levels of psychological distress, over and above the demographic characteristics of the sample and the levels of self-reported interpersonal problems.

Methods

Participants

A total of 1197 native Italian adults (876 [73.2%] females; mean age=28.53±11.37 years, range 19-66 years) volunteered for the study. Participants were university students (52.8%) recruited from two undergraduate courses at the University of Bergamo (Italy), or self-referred (39.3%) from the general population through a snowball procedure. Among the participants, 23.6% completed University, and 72.3% completed high school; 59.7% were married or in a relationship (mean relationship length=5.68±9.55 years; range: 0-50), and 35.5% were single; 26.8% were currently in psychotherapy (median treatment length=14 months), whilst 12.4% were thinking of starting treatment in the next few months. Inclusion criteria included the following: i) at least 18 years of age; ii) provided consent to participate; iii) understanding of spoken and written Italian. This study was conducted in accordance with ethical standards for the treatment of human experimental volunteers (World Medical Association, 2013). Participants provided written consent prior to participation.

Procedure

In this study, we adopted the Italian version of ECR which was translated from English by Picardi et al. (2000) through a multi-stage procedure.

Cross-sectional data were collected online from March to September 2018. The survey link was distributed via email to university students at Bergamo University. Each student forwarded the e-mail to a minimum of one and maximum of five individuals in his or her mailing list. A total of 300 students contributed to the data collection.

To ensure that no individuals completed the battery more than once, we collected personal information (e.g., IP addresses), which was anonymized once data completion was complete. Participants were recruited on a voluntary basis. Those who agreed to participate (i.e., provided online written consent) were subsequently redirected to a webpage, which detailed the overall aims of the study. Participants were subsequently directed to a demographic survey and a battery of questionnaires. Completion time was approximately 40 minutes. The first group of participants (n=989) was recruited in the period between March and June 2018 and was asked to complete the ECR-12, CERQ-short, PGWB-S, OQ45, and IIP-32. Due to the length of the original battery, we obtained further data on the validity of ECR-12 administering the original 36-item version of ECR, together with ASQ and RQ (see section Measures for a definition of all acronyms) to a second cohort of participants (n=208; recruited in September 2018). Samples were merged for the analyses. Italian versions of all measures were used in this study.

Measures

Attachment dimensions

The Experiences in Close Relationships – 12 (ECR- 12; Lafontaine et al., 2016) scale is a 12-item self-report measure of attachment to romantic partners. Derived from the original 36-item questionnaire (Brennan et al., 1998), the ECR-12 measures two dimensions of attachment to romantic partners, namely attachment avoidance (6 items) and attachment anxiety (6 items). Items are scored on a 7- point Likert scale (1=strongly disagree; 7=strongly agree), with higher scores indicating greater attachment avoidance and attachment anxiety with romantic partners. Respondents are asked to rate how they feel in emotionally intimate relationships. The ECR demonstrated good construct validity and internal reliability (Brennan et al., 1998). In the current study, Cronbach’s alphas of the 36-items version’s subscales were good (.91 for both subscales).

The Attachment Style Questionnaire (ASQ; Feeney et al., 1994; Fossati et al., 2003) is a 40-item self-report measure of attachment dimensions in general (i.e., nonromantic) relationships. The ASQ contains five subscales: Confidence in Self and Others (8 items), Need for Approval (7 items), Preoccupation with Relationships (8 items), Discomfort with Closeness (10 items), and Relationships as Secondary (7 items). Items are scored on a 6- point Likert scale (1=totally disagree; 6=totally agree). Higher scores on the Preoccupation with Relationships and Need for Approval scales are associated with greater attachment anxiety, while higher scores on the Discomfort with Closeness and Relationships as Secondary scales are associated with greater attachment avoidance. Finally, higher scores on the Confidence in Self and Others scale indicate greater attachment security. The ASQ evidenced good construct validity and internal reliability (Feeney et al., 1994; Fossati et al., 2003). In the present study, Cronbach alphas of the subscales were moderate to good (ranging .73 - .84).

The Relationship Questionnaire (RQ; Bartholomew & Horowitz, 1991, 1995) is a measure of attachment patterns, conceptualized within a two-dimensional model. The RQ consists of four paragraphs that describe the Secure, Dismissing, Preoccupied, and Fearful attachment styles. First, participants select which of the four paragraphs is most like them. Then, participants rate their similarity to each of the four profiles on a 7-points Likert-scale (1=not at all like me; 7=very much like me). The RQ evidenced good construct, convergent, and divergent validity (Bartholomew & Horowitz, 1991).

Interpersonal problems

The Inventory of Interpersonal Problems – 32 (Horowitz, Alden, Wiggins, & Pincus, 2000) is a 32-item self-report measure of interpersonal problems and distress. The IIP-32 includes 8 subscales (each composed of 4 items): Domineering, Vindictive, Cold, Socially Inhibited, Non-assertive, Exploitable, Overly-nurturant, and Intrusive. Participants rate items on a 5-point Likert-type scale (0=not at all; 4=extremely). Total scores for the subscales range from 0 to 16, with higher scores indicating greater interpersonal problems in that octant or domain. The IIP evidenced good construct validity and internal reliability (Horowitz et al., 2000; Lo Coco et al., 2018). In the present study, the Italian version of the IIP-32 was adopted (Lo Coco et al., 2018) and the Cronbach’s alphas of its subscales were moderate to good (ranging from .68-.85).

Psychological distress

The Outcome Questionnaire-45 (OQ45.2; Lambert, Hansen, & Finch, 2001) is a 45-item self-report measure of psychological and interpersonal distress. Items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale (0=never; 4=always). The OQ-45 consists of three subscales, namely Symptom Distress (SD; 25 items), Interpersonal Relations (IR; 11 items), and Social Role (SR; 9 items). Total scores range from 0 to 180, with higher scores indicating greater distress. Scores above the cut-off of 66 suggest the presence of significant levels of psychological and interpersonal difficulties in Italian samples (Chiappelli, Lo Coco, Gullo, Bensi, & Prestano, 2008). The Italian version of the OQ45.2 demonstrated good construct validity and internal reliability (Lambert et al., 2001; Lo Coco et al., 2008). Cronbach’s alpha for the total score was good (.93).

Well-being

The Psychosocial General Well-Being Index - short (PGWB-S; Grossi et al., 2006) is a 6-item self-report questionnaire that evaluates psychological well-being during a 4-week period. Each item is rated on a 6-point Likert scale (1 to 6). Total score range from 0 to 16, with higher scores indicating greater well-being. The PGWB-S evidenced good construct validity and internal reliability (Grossi et al., 2006). In the present study, the Cronbach’s alpha was good (.89).

Coping strategies

The Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire – short (CERQ-short; Garnefski & Kraaij, 2006; Potthoff et al., 2016) is an 18-item self-report measure of cognitive strategies of emotion regulation used in response threatening or stressful life events. The CERQ-short includes 9 subscales (each composed of 2 items), namely Self-blame, Other-blame, Rumination, Catastrophizing, Putting into Perspective, Positive Refocusing, Positive Reappraisal, Acceptance, and Planning. Items are rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale (1=(almost) never; 5=(almost) always). Total scores for the subscales range from 1 to 10. The higher the subscale score, the more a specific cognitive strategy is used. The CERQ-short evidenced good construct validity and internal reliability (Garnefski & Kraaij, 2006). In the present study, Cronbach alphas of the subscales were poor to good (ranges .54-.83).

Statistical analyses

We assessed the measurement model through a Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA), followed by an Exploratory Structural Equation Modeling (ESEM) method. ESEM is a recently-developed technique that provides goodness-of-fit statistics while allowing cross-loadings, and is preferred to the more restricted CFA in clinical psychology research (Marsh, Morin, Parker, & Kaur, 2014; Toth-Kiraly, Bothe, Rigo, & Orosz, 2017). In a typical CFA, items only load onto their respective factors (i.e., there are no cross-loadings). In ESEM, after an initial oblique rotation, the items still load mainly onto their main factors, but cross-loadings are only targeted and not forced, to be as close to zero as possible (Toth-Kiraly et al., 2017). Therefore, ESEM shows improved model fits and provides a more realistic representation of the data when compared to CFAs (Toth-Kiraly et al., 2017). Additionally, we tested the measurement invariance of the ECR-12 across the two genders, adopting a procedure defined in Muthen and Muthen (i.e., imposing varying degrees of invariance on the model parameters; Muthen & Muthen, 2017). In all analyses, parameters were estimated using a robust maximum likelihood (MLR) approach. Modification indices were examined for possible improvement to the fit of the original model: according to a previous study (Tasca et al., 2018), we expected at least a pair of error variances to be correlated, given the wording of the items. Criteria for optimal model fit were: a normed chi-squared of 3 or less, a root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) of 0.06 or less, an upper RMSEA’s 90% confidence interval bound of 0.08 or less, a comparative fit index (CFI) and a Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) of 0.95 or more, and a standardized root mean squared residual (SRMR) of 0.05 or less (Hu & Bentler, 1999). Finally, the magnitude of the factor loadings was interpreted according to the guidelines (Comrey & Lee, 2013).

We measured internal consistency via Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for both ECR-12 subscales. In addition, we reported the McDonald’s model-based composite reliability coefficients (i.e., McDonald’s Omega, McDonald, 1970) which are considered more reliable measures of internal consistency than Cronbach’s alpha (Sijtsma, 2009). Coefficients of at least 0.8 is suggestive of an optimal internal consistency (Connelly, 2011). Finally, we examined the correlations between ECR-12 and the 36- item ECR, to ensure that the short version performed similarly to the full version of ECR.

We evaluated convergent validity through Pearson’s r correlations between ECR-12 scores, and the ASQ, and RQ subscale scores (n=208). In addition, we conducted a MANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc comparisons, to examine whether levels of Attachment Avoidance and Attachment Anxiety differed among the four attachment styles (Secure, Fearful, Preoccupied, and Dismissing) provided by the RQ. We examined concurrent and divergent validity in two steps (n=989). First, we correlated ECR- 12 subscale scores with PGWB-s, CERQ-short, and IIP- 32 total and subscale scores. Second, we tested the hypothesis that ECR-12 subscale scores will be significantly associated with distress (computed from OQ45.2) through a hierarchical logistic analysis. We entered age, gender, and levels of interpersonal distress (evaluated using IIP-32) in the first block and entered the ECR-12 subscale scores in the second block. Interpersonal problems are a well-known cause of psychopathology (Horowitz et al., 2000), and are strongly associated with attachment insecurity (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2016), suggesting their use as a covariate in the analyses. Finally, a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis was performed to assess the diagnostic accuracy of the ECR-12 to detect psychological distress, and to determine a cutoff score.

All effect sizes (r, d, and η2) were computed and interpreted according to guidelines (Cohen, 1988). Analyses were performed using MPLUS version 7.0 and Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 25.0. All statistical tests were two-tailed, and a P-value≤.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Preliminary analyses

We evaluated the presence of univariate outliers using standardized scores, and the presence of multivariate outliers through Mahalanobis distance (P<.001; Tabachnick & Fidell, 2007). Analyses did not reveal any univariate outliers; however, 32 cases were identified as multivariate outliers and were subsequently removed from the analyses (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2007). Univariate and multivariate normality were assessed through box-plots, stem and leaf plots, probability plots, histograms, and skewness and kurtosis values. ECR items 8, 18, and 24 were slightly negatively skewed; items 9, 15, 27 and 29 were moderately positively skewed; and items 25 and 31 were severely positively skewed: a square-root, a log10, and reflect and inverse transformations corrected the violation of the assumption, respectively (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2007). The resulting variables were used in CFA and ESEM.

We found a significant negative correlation between age and ECR-12 anxiety subscale scores (n=1197; r=-.27, P≤0.001), with small effects, suggesting that older participants had lower levels of attachment anxiety compared to younger ones. However, the association between age and attachment avoidance was not significant (n=1197; r=-.02, P=0.562). We further correlated relationship length (expressed in years) with attachment dimensions. We found a negative, significant relationship with attachment anxiety (n=1189; r=-.27, P<0.001), with small effects, while the association with attachment avoidance was not significant (n=1189; r=-.05, P=0.088). Results suggested that those who were engaged in lengthier relationships had lower levels of attachment anxiety.

Additionally, we compared the levels of attachment anxiety and avoidance between i) males and females, ii) those who were engaged\married vs those who were single/ divorced, and iii) those who were in treatment vs those who were not, through independent sample t-tests. Males showed significantly lower levels of attachment anxiety, compared to females (t=-3.336, df=1195, P=0.001, d=0.22) with small effects. However, the levels of attachment avoidance were similar across the two groups, t=1.806, df=1195, P=0.071, d=0.12. Those who were married or engaged reported significantly lower levels of both attachment anxiety and avoidance, compared to those who were single or divorced (attachment anxiety: t=7.786, df=1191, P<0.001, d=0.47, with medium effects; attachment avoidance=t=10.830, df=1191, P<0.001, d=0.63, with medium effects). Finally, participants in treatment had significantly higher levels of attachment anxiety compared to those not in treatment, t=-3.486, df=1195, P<0.001, d=0.23, with small effects. However, the levels of attachment avoidance were similar across the two groups, t=-1.233, df=1195, P=0.218, d=0.08. Means and standard deviations for all the aforementioned groups are reported in Supplementary Table S1 (Appendix).

Construct validity and internal consistency

We evaluated the model fit of the Italian version of ECR-12 through a Confirmatory Factor Analysis and an Exploratory Structural Equation Modeling method. Initially, the CFA performed on the sample (n=1165) indicated a poor fit of the data: normed χ2 (53)=10.2; RMSEA=0.088 (90% CI: 0.08-0.09); CFI=0.91; TLI=0.89; SRMR=0.07. However, the ESEM showed a better fit: normed χ2 (43)=7.2; RMSEA=0.072 (90% CI: 0.07-0.08); CFI=0.95; TLI=0.92; SRMR=0.03. Some indexes were above or below their optimal cut-off criteria, thus we used Modification Indices (MI) to identify any specific sources of model misspecification. Accordingly, we modified the original ESEM model allowing the error terms of items 18 and 24 to correlate. MI indicated that the pair of error terms shared additional covariance, which may be because the items are similarly worded or reverse-worded (Byrne, 2016; Tasca et al., 2018). The resulting unconstrained model had an excellent fit: normed χ2 (42)=4.60; RMSEA=0.056 [90% CI: 0.05–0.06]; CFI=0.97; TLI=0.96; RMSR=0.024. The χ2 difference test was significant, suggesting that the modified model had a better fit of the data compared to the original one. ESEM model had poor (<0.32; Comrey & Lee, 2013) and mostly trivial loadings of both factors on the items of the opposite factor. All standardized factor loadings between-factors and betweenerror covariances are reported in Table 1. We also tested the measurement invariance of ECR-12 across the two genders: the Satorra-Bentler scaled χ2 Difference Test (Muthen & Muthen, 2017) showed non-significant improvements in model fit from an unconstrained to a progressively constrained model (i.e., starting from the imposition of equality constraints on the intercepts, then on factor loading matrices, on factor variances, and finally on factor covariances), suggesting that ECR-12 performed similarly across the two genders (model fit and factor loadings are shown in Supplementary Table S2 in the Appendix).

he Italian version of ECR-12 demonstrated good internal consistency (Clark & Watson, 1995), with a Cronbach’s alpha of .85 for Anxiety and .86 for Avoidance, and with a McDonald’s omega of .84 for Anxiety and .88 for Avoidance. Further, ECR-12 subscales were significantly and positively correlated with the original 36-items ECR subscales (n=208; r=.94, P<0.001 for Anxiety and r=.86, P<0.001 for Avoidance, with large effects), suggesting that ECR-12 performed similarly to the full version of ECR.

Concurrent and divergent validity

Means, SD, and significant correlations between psychological questionnaires and ECR-12 subscale scores are reported in Table 2.

Significant positive relationships were found between ECR-12 and ASQ Need for Approval and Preoccupation with Relationships scales (both measures of attachment anxiety; Feeney et al., 1994). Effect sizes were moderate to large. Moreover, ECR-12 Attachment Avoidance was significantly, positively associated with ASQ Discomfort with Closeness and Relationships as Secondary scales (both measures of attachment avoidance; Feeney et al., 1994), with moderate effects. Finally, both scales were negatively associated with ASQ Confidence, a measure of attachment security (Feeney et al., 1994), with moderate effects. Few other correlations were significant, and effects were small. Of note, all ASQ subscales were significantly correlated between them (data not shown). With regards to correlations between the ECR-12 subscales and RQ’s questions on the four profiles, we found that ECR- 12 Attachment Anxiety was negatively correlated with RQ Secure and Dismissing, and positively correlated with Fearful and Preoccupied. In both cases, effects were small to medium. With regards to ECR-12 Attachment Avoidance, the scale was negatively correlated with RQ Secure, and positively related to Fearful and Preoccupied, with small effects. Taken together, these findings suggest that ECR-12 has adequate convergent validity when assessed against two commonly used measures of attachment dimensions (ASQ and RQ).

We performed a multivariate analysis of variance to investigate the effect of the four attachment styles provided by RQ on ECR-12 subscale scores (Table 3). Results showed a statistically significant effect of attachment styles on the linear combination of the dependent variables, Wilks λ=0.763, F(6,406)=9.790, P<.001, η2=.126, with large effects. Tukey’s post hoc test for ECR-12 Attachment Anxiety scale indicated that those who self-reported a Secure and a Dismissing attachment style had lower levels of attachment anxiety compared to Fearful and Preoccupied ones. Regarding ECR-12 Attachment Avoidance, Tukey’s post hoc test indicated that those with a self-reported Secure attachment style had lower levels of attachment avoidance compared to Fearful ones. All other comparisons were not significant. Results suggest that self-reported attachment styles are associated with different levels of attachment anxiety and avoidance.

Divergent and concurrent validity was assessed through correlations between ECR-12 and PGWB-s, IIP- 32, OQ45.2, and CERQ-short subscale scores (Table 2). We found significant, negative relationships between both ECR-12 subscales and PGWB-s, suggesting that those with higher levels of attachment anxiety and avoidance have lower perceived well-being. The effect size was medium for attachment anxiety and small with avoidance. Higher attachment insecurity was also associated with increased levels of psychological distress, specific interpersonal problems, and with IIP-32 total score, and the effects were small to medium. Interestingly, attachment anxiety was the only subscale positively and significantly related to Intrusiveness. As regards the CERQ-s, we found that both attachment dimensions were positively correlated with higher levels of dysfunctional cognitive coping strategies (such as Self-blame and Catastrophizing) and with lower levels of positive strategies (such as Positive Refocusing to other pleasant topics instead of the actual event). Attachment anxiety was also significantly and positively associated with negative regulation strategies (Rumination and Other-blame) and negatively related to positive regulation strategies (Acceptance of the event, Putting into perspective the event, and Positive Reappraisal of stressful events in term of personal growth). All effects were small to medium.

Table 1.

Standardized parameter estimates for the Confirmatory Factorial Analysis (CFA) and Exploratory Structural Equation Modelling (ESEM) solutions of the Italian version of Experience in Close Relationship Scale 12 (ECR-12) (N=1165).

| Items | CFA | ESEM | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety | Avoidance | Anxiety | Avoidance | |

| (λ) | (λ) | (λ) | (λ) | |

| Attachment Anxiety factor | ||||

| 2. I worry about being abandoned [Ho paura di essere lasciato/a] |

.831* | \ | .863* | .004 |

| 8. I worry a fair amount about losing my partner [Mi preoccupo molto di perdere il mio partner] |

.751* | \ | .783* | .116* |

| 18. I need a lot of reassurance that I am loved by my partner [Ho bisogno di molte rassicurazioni sul fatto di essere amato/a dal mio partner] |

.763* | \ | .730* | .103* |

| 14. I worry about being alone [Ho paura di restare solo/a] |

.658* | \ | .657* | .014 |

| 24. If I can’t get my partner to show interest in me, I get upset or angry [Se non riesco ad ottenere che il partner mi dimostri interesse, ne sono turbato/a o mi arrabbio] |

.620* | \ | .544* | .023 |

| 6. I worry that romantic partners won’t care about me as much as I care about them [Temo che il partner non tenga a me quanto io tengo a lui/lei] |

.575* | \ | .554* | .224* |

| Attachment Avoidance factor | ||||

| 9. I don’t feel comfortable opening up to romantic partners [Ho difficoltà ad aprirmi con il partner] |

\ | .859* | .042* | .860* |

| 25. I tell my partner just about everything [Al mio partner dico quasi tutto] |

\ | .741* | .030 | .745* |

| 15. I feel comfortable sharing my private thoughts and feelings with my partner [Mi sento a mio agio nel condividere con il partner i miei più intimi pensieri e sentimenti] |

\ | .732* | .038 | .743* |

| 27. I usually discuss my problems and concerns with my partner [Di solito parlo con il mio partner dei miei problemi e delle mie preoccupazioni] |

\ | .727* | .152* | .712* |

| 29. I feel comfortable depending on romantic partners [Mi sento a mio agio ad affidarmi al partner] |

\ | .692* | .028 | .690* |

| 31. I don’t mind asking romantic partners for comfort, advice, or help [Non mi crea problemi chiedere conforto, consiglio o aiuto al partner] |

\ | .675* | .041 | .678* |

| Correlation between Factors | .113* | .133* | ||

| Correlation between ECR18 and ECR24 items | \ | .384* | ||

Values in italics indicate standardized factor loadings whose magnitude is interpreted as “fair” (i.e., ≥ 0.45; Comrey & Lee, 2013). λ, standardized factor loadings. *indicates significant estimates (P<0.001).

Table 2.

Means, standard deviation and Zero-order correlations between psychological questionnaires and Experience in Close Relationship Scale 12 subscale scores.

| Variables | M (SD) | ECR-12 Anxiety | ECR-12 Avoidance |

|---|---|---|---|

| ECR-12 Anxiety | 25.54 (8.60) | \ | 0.12** |

| ECR-12 Avoidance | 14.72 (7.07) | 0.12** | \ |

| ASQ C | 3.83 (0.68) | -.319** | -.332** |

| ASQ DC | 3.69 (0.82) | .183** | .318** |

| ASQ NA | 2.93 (0.92) | .489** | 198** |

| ASQ PR | 3.45 (0.84) | .602** | .176* |

| ASQ RS | 2.19 (0.71) | .126 | .370** |

| RQ Secure | 3.94 (1.94) | -.180** | -.209** |

| RQ Fearful | 3.18 (2.05) | .403** | .242** |

| RQ Preoccupied | 2.62 (1.69) | .283** | .151* |

| RQ Dismissing | 3.11 (1.93) | -.296** | .047 |

| PGWB-s | 17.49 (5.43) | -.386** | -.264** |

| OQ-45.2 Symptom Distress | 35.75 (14.41) | .442** | .320** |

| OQ-45.2 Interpersonal Relations | 15.64 (5.78) | .410** | .469** |

| OQ-45.2 Social Role | 11.89 (4.38) | .250** | .236** |

| OQ-45.2 Total Score | 63.27 (21.98) | .447** | .380** |

| IIP-32 Domineering | 3.29 (2.99) | .226** | .143** |

| IIP-32 Vindictive | 2.94 (2.74) | .115** | .187** |

| IIP-32 Cold | 3.47 (3.1) | .177** | .374** |

| IIP-32 Socially Inhibited | 4.9 (3.86) | .215** | .154** |

| IIP-32 Non-assertive | 5.56 (3.12) | .236** | .159** |

| IIP-32 Exploitable | 6.74 (3.02) | .238** | .132** |

| IIP-32 Overly-nurturant | 6.13 (3.21) | .275** | .126** |

| IIP-32 Intrusive | 4.45 (3.38) | .269** | 0.03 |

| IIP-32 Total | 37.48 (14.65) | .384** | .280** |

| CERQ-s Self-blame | 5.33 (2.03) | .195** | .137** |

| CERQ-s Other-blame | 3.85 (1.42) | .083** | 0.03 |

| CERQ-s Rumination | 6.63 (2.01) | .262** | 0.02 |

| CERQ-s Catastrophizing | 4.7 (2.1) | .327** | .101** |

| CERQ-s Putting into Perspective | 5.58 (2.09) | -.155** | -0.03 |

| CERQ-s Positive Refocusing | 7.18 (2.01) | -.125** | -.124** |

| CERQ-s Positive Reappraisal | 4.2 (1.83) | -.077* | 0.02 |

| CERQ-s Acceptance | 6.3 (1.97) | -.074* | 0.04 |

| CERQ-s Planning | 6.68 (1.8) | -0.052 | -0.04 |

M, means; SD, standard deviation; ECR, Experiences in Close Relationships; ASQ, Attachment Style Questionnaire (C, Confidence; DC, Discomfort with Closeness; NA, Need for Approval; PR, Preoccupation with Relationships; RS, Relationships as Secondary); RQ, Relationship Questionnaire; OQ45.2, Outcome Questionnaire-45; PGWB-s, Psychosocial General Well-Being Index - short; CERQ-s, Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire – short. N for ASQ and RQ=208. N for other questionnaires=989.

*P≤0.05 (2-tailed)

**P≤0.01 (2-tailed).

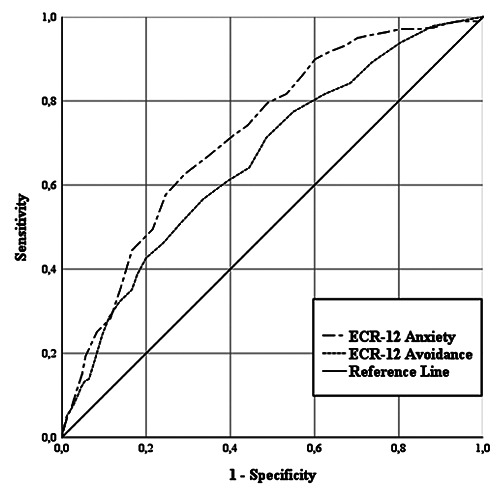

We performed a multiple hierarchical logistic regression to evaluate the association between ECR-12 subscale scores and the presence of significant psychological distress (exceeded OQ45.2 cut-off criteria vs did not exceed), while controlling for demographic information and levels of interpersonal problems. A total of 279 participants (28.2%) had a total score equal to or higher than the cutoff criteria (mean score for those above the cut-off: 84.65±14.92; mean score for those who did not exceed the cut-off criteria: 54.87±18.32). The final logistic regression model (i.e., Block 2) was statistically significant, χ2 (5)=428.38, P<0.001, Nagelkerke R2=.51 (R2 change=5.3%), and correctly classified 81.1% of cases. Both ECR-12 Attachment scales were a significant predictor of psychological distress (OR 1.1 in both cases). Thus, for every one unit increase in the ECR-12 Attachment Anxiety and Avoidance scales, the participants were 10% more likely to exceed the cut-off criteria for significant levels of psychopathology, while controlling for demographic variables and interpersonal problems (Table 4). Finally, ROC analyses showed that only the ECR-12 Anxiety subscale accurately discriminated individuals with significant levels of psychopathology from healthy controls (Anxiety subscale: area under the curve=0.72%, cut-off 29.5 points, sensitivity=63%, specificity=71%; Avoidance subscale: area under the curve=0.66%, cut-off 15.5 points; sensitivity=57%, specificity=67%; Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Receiver Operating Characteristics (ROC) curve with Experience in Close Relationship Scale 12 (ECR-12) Anxiety and Avoidance subscale scores as predictor variables, and OQ-45.2 scores (above or below the cut-off) as state variable (N=987).

Table 3.

Means, standard deviation and results of the MANOVA for Experience in Close Relationship Scale 12 Anxiety and Avoidance scores across the four attachment styles (Secure, Fearful, Preoccupied and Dismissing) provided by the Relationship Questionnaire.

| Secure | Fearful | Preoccupied | Dismissing | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N=96) | (N=43) | (N=25) | (N=44) | |

| ECR-12 Anxiety (SD) | 20.79 (7.77)b, c | 28.51 (7.16)a, d | 28.00 (9.14)a, d | 18.20 (7.95)b, c |

| ECR-12 Avoidance (SD) | 12.46 (5.33)b | 16.16 (7.26)a | 14.28 (7.21) | 14.20 (6.26) |

ECR-12, Experience in Close Relationship Scale 12; SD, standard deviation. N=208. Superscripts refer to significant comparisons (a Secure; b Fearful; c Preoccupied; d Dismissing).

Table 4.

Hierarchical logistic regression of demographic variables and Inventory of Interpersonal Problems 32 total scores predicting the threshold for significant psychopathological levels (i.e., OQ45.2 cut-off scores).

| B | S.E. | Wald | P-value | OR | 95% CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Block 1 | Age | -.287 | .042 | 47.094 | <.001 | .751 | .69–.82 |

| Females | .561 | .211 | 7.070 | .008 | 1.752 | 1.16–2.65 | |

| Males | -.561 | .211 | 7.070 | .008 | .571 | .377–.863 | |

| IIP32 Total | .060 | .008 | 63.460 | <.001 | 1.062 | 1.05–1.08 | |

| Block 2 | ECR-12 Anxiety | .063 | .013 | 22.846 | <.001 | 1.065 | 1.04–1.09 |

| ECR-12 Avoidance | .072 | .013 | 31.135 | <.001 | 1.075 | 1.05–1.10 |

N=987. IIP-32, Inventory of Interpersonal Problems 32; ECR-12, Experience in Close Relationship 12.

Discussion

The current study evaluated the psychometric properties of the ECR-12 in a large sample of native Italian adults. Results supported the good factorial structure and reliability of the Italian version of the ECR-12 and provided further support for its convergent and divergent validity with several under-investigated psychological dimensions.

The ECR-12 showed good construct validity. The final ESEM model had an excellent fit to the data and suggested the presence of two orthogonal constructs, namely attachment Anxiety and Avoidance, in line with the original observations (Brennan et al., 1998; Lafontaine et al., 2016; Cameron et al., 2012). The Italian version of the ECR-12 also demonstrated good internal consistency, thus providing evidence on the unidimensionality of the two subscales (Connelly, 2011). These findings are in line with those reported by Lafontaine et al. (2016), and by Tasca et al. (2018) in their mixed samples of English-speaking participants (e.g., individuals from general population, and treatment-seeking patients). Finally, the large correlations between the shortened and the original subscales of the ECR suggested that the Italian version of ECR-12 performed similarly to its full version.

We identified several sociodemographic correlates of adult attachment dimensions. Consistent with existing literature (see for example Chopik, Edelstein, & Fraley, 2013; Del Giudice, 2011; Mikulincer & Shaver, 2016; Petrowski, Schurig, Schmutzer, Brahler, & Stobel- Richter, 2015), males, longer relationships, not being in treatment, and older age were associated with lower levels of attachment anxiety, while being married or engaged was associated with lower levels of attachment insecurity. Chopik et al. (2013) suggested that older adults experience strong changes in their social roles, which in turn affects their personality development, leading to lower levels of attachment insecurity. Gender differences were also consistent with the integrative model of sex differences in romantic attachment proposed by Del Giudice (2011). The model posits that attachment anxiety is a female- biased strategy designed to maximize closeness with kin and investment from both kin and partners, thus being structurally higher among women compared to men (for more details, see Del Giudice, 2011). We also found that those who were more secure were more likely to form, consolidate, and maintain lasting and satisfying couple relationships, which is in accordance with attachment theory (Chopik et al., 2013; Mikulincer & Shaver, 2016). Finally, those currently enrolled in treatment reported higher levels of attachment anxiety: it is worth noting that those who are more anxious in their attachments present themselves as dependent and needy, face more difficulties regulating their emotions, and experience high levels of psychological distress (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2016). As a result, they are probably more prone to seek help from an attachment figure (i.e., a therapist) compared both to securely attached and avoidantly attached individuals.

In our study we administered two other valid measures of attachment dimensions, namely ASQ and RQ. Pearson’s r correlational analyses evidenced moderate and significant associations between ECR-12 Anxiety subscale and ASQ Need for Approval and Preoccupation with Relationships scales (measures of attachment anxiety). On the contrary, the ECR-12 Avoidance subscale was significantly correlated with the ASQ Discomfort with Closeness and Relationships as Secondary scales (both measures of attachment avoidance), with moderate effects. As expected, both ECR- 12 subscales had significant, negative correlations with the ASQ Confidence subscale, a measure of attachment security. Taken together, our findings provide evidence on the convergent validity of the scale. In regards to the convergent validity with the RQ, it’s worth noting that this instrument forces individuals to i) choose the specific attachment category (among Secure, Dismissing, Preoccupied, and Fearful) that best represents them, and subsequently ii) rate their similarity to each of the four profiles (Bartholomew & Horowitz, 1991). The RQ was designed to assess adult attachment within Bartholomew’s four-category, two-dimensional model (Bartholomew & Horowitz, 1991): within this framework, a specific combination of avoidant and anxious axes lead to one of the four attachment patterns (Bartholomew & Horowitz, 1991). For example, people with a secure attachment are characterized by lower levels of both attachment anxiety and avoidance, while those with a Dismissing style score high in avoidance and low in anxiety (Bartholomew & Horowitz, 1991). In our study, we examined differences in self-reported levels of attachment insecurity between the four patterns provided by the RQ, as well as correlations between the attachment dimensions and the self-rated similarities with each profile (Tables 2 and 4). Our results were partly in accordance with the Bartholomew’s model (1991), thus providing evidence of good convergent validity. Specifically, the MANOVA demonstrated that those with a Secure and a Dismissing style reported the lowest levels of attachment anxiety compared to those with a Fearful and Preoccupied style, and that those with a Fearful style reported the highest levels of attachment avoidance.

In terms of divergent and concurrent validity, we found that attachment insecurity was significantly and negatively associated with lower levels of perceived wellbeing (measured through PGWB-S), and that this association was stronger with attachment anxiety. This is in line with a view of attachment as a core aspect of the individual’s subjective well-being (see for example Karreman & Vingerhoets, 2012), and suggests that the ability to build positive and fulfilling personal relationships with others (which are strongly based on IWMs) contributes significantly to the individual’s quality of life (Wei, Liao, Ku, & Shaffer, 2011). Our findings were similar to those reported by previous studies, which demonstrated that insecure attachment dimensions were negatively correlated with subjective or eudemonic well-being (Kafetsios & Sideridis, 2006; Karreman & Vingerhoets, 2012; Wei et al., 2011).

As expected, attachment anxiety and avoidance were significantly and positively associated with interpersonal problems (measured through IIP-32), suggesting that higher levels of attachment insecurity are related to worse relational problems. It is well known that insecure adults experience poor interpersonal relations, which can lead to low relationship satisfaction, loneliness, and social isolation (for a review, see Mikulincer & Shaver, 2012). In our study, attachment anxiety was associated with a higher level of interpersonal problems compared to attachment avoidance, which was in accordance with previous findings (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2012, 2016). Interestingly, attachment anxiety was the only subscale positively and significantly correlated with Intrusiveness, an IIP-32 scale that describes problems with friendly dominance (Horowitz et al., 2000). Individuals with high levels of intrusiveness have a need to feel engaged with other people, imposing their presence onto others. In addition, they find it difficult to spend time alone (Horowitz et al., 2000). Recall that highly avoidant individuals are characterized by a fear of intimacy and discomfort with closeness: as such, Intrusiveness is not a typical characteristic of this attachment dimension, thus explaining our findings.

In terms of the associations with specific cognitive strategies used to manage uncomfortable emotions during or after the experience of stressful events (measured through CERQ-Short), both attachment dimensions were correlated with poor coping skills. Highly anxious individuals made less use of adaptive strategies (such as Acceptance, Positive Reappraisal, Putting things into prospective and Positive Refocusing), and largely adopted inadequate cognitive emotion regulation strategies (such as Rumination, Catastrophizing, Self- and Other-blame). These findings were in accordance with previous works (Pascuzzo et al., 2013; Simpson & Rholes, 2018) and support the idea that those with attachment anxiety have poor emotion regulation competencies (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2016). Thus, during stressful events, they tend to use dysfunctional coping strategies that sustain or escalate their worries, keeping their attachment systems activated and consolidating their feelings of distress (Pascuzzo et al., 2013; Simpson & Rholes, 2018). It is worth noting that effective emotion regulation is essential in determining the healthy functioning of an individual, and his or her personal and social life (Garnefski, Kraaij, & Spinhoven, 2001). As such, we suppose that the lower levels of wellbeing, and higher levels of interpersonal problems and distress, are putatively explained by a wider use of dysfunctional coping strategies among those with attachment anxiety (Pascuzzo et al., 2013). However, the correlational nature of our data does not allow us to establish causal links.

Finally, our results also indicated that participants with higher levels of attachment anxiety or avoidance were more likely to experience significant levels of psychological distress (evaluated through OQ45.2), even after controlling for age, gender, and level of interpersonal problems. These findings support the idea that attachment insecurity constitutes a general risk factor for the development of psychological disorders (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2016), over and above the self-reported levels of relational difficulties. Mikulincer and Shaver (2012) suggested that attachment insecurity probably reduces both the resilience to stressors and the psychosocial resources of the individual, acting as a catalyst of other pathogenic processes for the development of psychiatric disorders (for a review, see Mikulincer & Shaver, 2016). Of note, the ROC analysis indicated that the ECR-12 Anxiety was the only subscale able to discriminate participants with significant levels of psychological distress from healthy controls. Future researchers and practitioners could adopt the provided cut-off score (≥ 29.5 points) to identify those individuals with psychopathological levels of attachment anxiety. Taken together, these results support the validity of the Italian version of ECR-12; specifically, its ability to accurately assess dimensions of attachment insecurity and its potential utility in clinical settings.

This study has some limitations. First, test-retest reliability was not examined, even if previous studies reported good stability of ECR-12 subscale scores across a relatively long period of time (Lafontaine et al., 2016; Tasca et al., 2018). Future research should investigate testretest correlations of the Italian version of the ECR-12. Second, the cross-sectional nature of our data does not allow us to draw inferences regarding causality. Third, our sample was composed mainly of women (73.2%) and university students (52.8%); thus, no data from clinical samples has been collected to date. However, (i) the measurement model was invariant across genders, suggesting that - even if the sample was unbalanced - there were no gender differences in the factorial structure of the questionnaire, and (ii) we were largely interested in evaluating the factorial structure of ECR-12 in the general population and not a clinical sample. Finally, cut-off criteria from the OQ45.2 suggested that one third of our participants had significant levels of psychological distress, and the mean total scores among those who met the cutoff were comparable to mean scores reported by an Italian psychiatric sample (Chiappelli et al., 2008), increasing the validity of our findings.

Conclusions

In summary, the present study suggests that the Italian version of the ECR-12 is a methodologically sound measure of adult attachment dimensions. Compared to other commonly used instruments such as the ASQ and RQ, the ECR- 12 stands out for its good internal consistency and two-dimensional, orthogonal structure, in accordance with other studies (Lafontaine et al., 2016; Tasca et al., 2018). Given its good psychometric properties, researchers and practitioners are encouraged to adopt the ECR-12 in Italy for their future research on adult attachment. For example, due to the moderating role of attachment in treatment outcomes, therapists could adopt this short questionnaire to investigate patients’ attachment dimensions before administering therapy, matching them to a treatment type that is best suited to their specific attachment attributes (e.g., a psychodynamic group interpersonal treatment for those with high levels of attachment anxiety; Tasca et al., 2006). Practitioners could also use the ECR-12 to examine and test for longitudinal changes in attachment dimensions among patients after a therapeutic intervention (Daniel, 2006).

References

- Ainsworth M., Blehar M., Waters E., Wall S. (1978). Patterns of attachment. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Alonso-Arbiol I., Balluerka N., Shaver P. R. (2007). A Spanish version of the Experiences in Close Relationships (ECR) adult attachment questionnaire. Personal Relations, 14(1), 45-63. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6811.2006.00141.x [Google Scholar]

- Bartholomew K., Horowitz L. M. (1991). Attachment styles among young adults: a test of a four-category model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61(2), 226-244. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.61.2.226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartholomew K., Horowitz L. M. (1995). Stili di attaccamento fra giovani adulti: analisi di un modello a quattro categorie. Carli L. (Ed.), Attaccamento e rapporto di coppia (pp. 229-273). Milan, Italy: Cortina Editore. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. (1969). Attachment and loss: Vol. 1. Attachment. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. (1980). Attachment and loss: Vol. 3. Loss, Sadness and Depression. New York, NY: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Brennan K. A., Clark C. L., Shaver P. R. (1998). Self-report measurement of adult attachment: An integrative overview. Simpson J. A., Rholes W. S. (Eds.), Attachment theory and close relationships (pp. 46-76). New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bretherton I. (1985). Attachment theory: Retrospect and prospect (Vol. 50). New York: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne B. M. (2016). Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Calvo V., Bianco F. (2015). Influence of adult attachment insecurities on parenting self-esteem: the mediating role of dyadic adjustment. Frontiers in Psychology, 6(1461). doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron J. J., Finnegan H., Morry M. M. (2012). Orthogonal dreams in an oblique world: A meta-analysis of the association between attachment anxiety and avoidance. Journal of Research in Personality, 46(5), 472-476. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2012.05.001 [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy J., Kobak R. R. (1988). Avoidance and its relation to other defensive processes. Belsky J. (Ed.), Clinical implications of attachment (Vol. 1, pp. 300-323). New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Chiappelli M., Lo Coco G., Gullo S., Bensi L., Prestano C. (2008). [The outcome questionnaire 45.2. Italian validation of an instrument for the assessment of psychological treatments]. Epidemiology and Psichiatric Sciences, 17(2), 152-161. doi: 10.1017/S1121189X00002852 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chopik W. J., Edelstein R. S., Fraley R. C. (2013). From the cradle to the grave: age differences in attachment from early adulthood to old age. Journal of Personality, 81(2), 171-183. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2012.00793.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chris Fraley R. (2002). Attachment stability from infancy to adulthood: Meta-analysis and dynamic modeling of developmental mechanisms. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 6(2), 123-151. doi: 10.1207/S15327957PSPR0602_03 [Google Scholar]

- Clark L. A., Watson D. (1995). Constructing validity: Basic issues in objective scale development. Psychological Assessment, 7(3), 309-319. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.7.3.309 [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Comrey A. L., Lee H. B. (2013). A first course in factor analysis. New York, NY: Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Connelly L. M. (2011). Cronbach’s alpha. Medsurg Nursing, 20(1), 44-45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel S. I. (2006). Adult attachment patterns and individual psychotherapy: a review. Clinical Psychology Review, 26(8), 968-984. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Carli P., Tagini A., Sarracino D., Santona A., Parolin L. (2016). Implicit attitude toward caregiving: the moderating role of adult attachment styles. Frontiers in Psychology, 6(1906). doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Giudice M. (2011). Sex differences in romantic attachment: a meta-analysis. Personality and Society Psychology Bullettin, 37(2), 193-214. doi: 10.1177/0146167210392789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Filippo J. M., Overholser J. C. (2000). Suicidal ideation in adolescent psychiatric inpatients as associated with depression and attachment relationships. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 29(2), 155-166. doi: 10.1207/S15374424jccp2902_2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donarelli Z., Kivlighan D. M., Allegra A., Lo Coco G. (2016). How do individual attachment patterns of both members of couples affect their perceived infertility stress? An actor–partner interdependence analysis. Personality and Individual Differences, 92, 63-68. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2015. 12.023 [Google Scholar]

- Embretson S. E., Steven P. (2000). Item response theory for psychologists. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Feeney J., Fitzgerald J. (2018). Attachment, conflict and relationship quality: laboratory-based and clinical insights. Current Opinion in Psychology, 25, 127-131. doi: 10.1016/j. copsyc.2018.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feeney J. A., Noller P., Hanrahan M. (1994). Assessing adult attachment. Attachment in adults: Clinical and developmental perspectives (pp. 128-152). New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fossati A., Feeney J. A., Donati D., Donini M., Novella L., Bagnato M., Maffei C. (2003). On the dimensionality of the attachment style questionnaire in italian clinical and nonclinical participants. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 20(1), 55-79. doi: 10.1177/02654075030201003 [Google Scholar]

- Fraley R. C., Waller N. G., Brennan K. A. (2000). An item response theory analysis of self-report measures of adult attachment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78(2), 350-365. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.78.2.350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garnefski N., Kraaij V. (2006). Cognitive emotion regulation questionnaire – development of a short 18-item version (CERQ-short). Personality and Individual Differences, 41(6), 1045-1053. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2006.04.010 [Google Scholar]

- Garnefski N., Kraaij V., Spinhoven P. (2001). Negative life events, cognitive emotion regulation and emotional problems. Personality and Individual Differences, 30(8), 1311-1327. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(00)00113-6 [Google Scholar]

- Grossi E., Groth N., Mosconi P., Cerutti R., Pace F., Compare A., Apolone G. (2006). Development and validation of the short version of the Psychological General Well-Being Index (PGWB-S). Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 4(1), 88. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-4-88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz L. M., Alden L. E., Wiggins J. S., Pincus A. L. (2000). IIP-64/IIP-32 professional manual. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Hu L. t., Bentler P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1-55. doi: 10.1080/ 1070551990954 0118 [Google Scholar]

- Kafetsios K., Sideridis G. D. (2006). Attachment, social support and well-being in young and older adults. Journal of Health Psychology, 11(6), 863-875. doi: 10.1177/135910530 6069084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karreman A., Vingerhoets A. J. J. M. (2012). Attachment and well-being: The mediating role of emotion regulation and resilience. Personality and Individual Differences, 53(7), 821-826. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2012.06.014 [Google Scholar]

- Lafontaine M.-F., Brassard A., Lussier Y., Valois P., Shaver P. R., Johnson S. M. (2016). Selecting the best items for a Short-Form of the Experiences in Close Relationships Questionnaire. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 32(2), 140-154. doi: 10.1027/1015-5759/a000243 [Google Scholar]

- Lafontaine M.-F., Lussier Y. (2003). Structure bidimensionnelle de l’attachement amoureux: Anxiete face a l’abandon et evitement de l’intimite. [Bidimensional structure of attachment in love: Anxiety over abandonment and avoidance of intimacy.]. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science/Revue canadienne des sciences du comportement, 35(1), 56-60. doi: 10.1037/h0087187 [Google Scholar]

- Lambert M. J., Hansen N. B., Finch A. E. (2001). Patientfocused research: Using patient outcome data to enhance treatment effects. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 69(2), 159-172. doi: 10.1037//0022-006X.69.2.159 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo Coco G., Chiappelli M., Bensi L., Gullo S., Prestano C., Lambert M. J. (2008). The factorial structure of the outcome questionnaire-45: a study with an Italian sample. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 15(6), 418-423. doi: 10.1002/cpp.601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo Coco G., Mannino G., Salerno L., Oieni V., Di Fratello C., Profita G., Gullo S. (2018). The Italian version of the Inventory of Interpersonal Problems (IIP-32): Psychometric properties and factor structure in clinical and non-clinical groups. Frontiers in Psychology, 9(341). doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh H. W., Morin A. J. S., Parker P. D., Kaur G. (2014). Exploratory structural equation modeling: an integration of the best features of exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis. Annual Review Of Clinical Psychology, 10(1), 85-110. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032813-153700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh H. W., Muthen B., Asparouhov T., Ludtke O., Robitzsch A., Morin A. J. S., Trautwein U. (2009). Exploratory Structural equation modeling, integrating CFA and EFA: application to students’ evaluations of university teaching. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 16(3), 439-476. doi: 10.1080/1070551090 3008220 [Google Scholar]

- McDonald R. P. (1970). The Theoretical foundations of principal factor analysis, canonical factor analysis, and alpha factor analysis. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology, 23(1), 1-21. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8317.1970. tb00432.x [Google Scholar]

- Messick S. (1989). Validity. Linn R. L. (Ed.), Educational Measurement (3rd ed., pp. 13-103). New York, NY: Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer M. (1995). Attachment style and the mental representation of the self. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(6), 1203-1215. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.69.6.1203 [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer M., Shaver P. R. (2012). An attachment perspective on psychopathology. World Psychiatry, 11(1), 11-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer M., Shaver P. R. (2016). Attachment in adulthood: Structure, dynamics, and change (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Muthen L. K., Muthen B. O. (2017). Mplus User’s Guide. Muthen & Muthen. Los Angeles, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Pascuzzo K., Cyr C., Moss E. (2013). Longitudinal association between adolescent attachment, adult romantic attachment, and emotion regulation strategies. Attachment & Human Development, 15(1), 83-103. doi: 10.1080/14616734.2013.745713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrowski K., Schurig S., Schmutzer G., Brahler E., Stobel- Richter Y. (2015). Is it attachment style or socio-demography: singlehood in a representative sample. Frontiers in Psychology, 6(1738). doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picardi A., Bitetti D., Puddu P., Pasquini P. (2000). La scala “Experiences in close relationships” (ECL), un nuovo strumento per la valutazione dell’attaccamento negli adulti: Traduzione, adattamento e validazione della versione italiana. [Development and validation of an Italian version of the questionnaire “Experiences in Close Relationships,” a new self-report measure of adult attachment.]. Rivista di Psichiatria, 35(3), 114-120. [Google Scholar]

- Pietromonaco P. R., Beck L. A. (2018). Adult attachment and physical health. Current Opinion in Psychology, 25, 115-120. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2018.04.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potthoff S., Garnefski N., Miklosi M., Ubbiali A., Dominguez-Sanchez F. J., Martins E. C., Kraaij V. (2016). Cognitive emotion regulation and psychopathology across cultures: A comparison between six European countries. Personality and Individual Differences, 98, 218-224. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2016.04.022 [Google Scholar]

- Ravitz P., Maunder R., Hunter J., Sthankiya B., Lancee W. (2010). Adult attachment measures: A 25-year review. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 69(4), 419-432. doi: 10.1016/j.psychores.2009.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenstein D. S., Horowitz H. A. (1996). Adolescent attachment and psychopathology. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 64(2), 244-253. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.64. 2.244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sijtsma K. (2009). On the use, the misuse, and the very limited usefulness of Cronbach’s Alpha. Psychometrika, 74(1), 107-120. doi: 10.1007/s11336-008-9101-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson J. A., Rholes W. S. (2017). Adult attachment, stress, and romantic relationships. Current Opinion in Psychology, 13, 19-24. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson J. A., Rholes W. S. (2018). Adult attachment orientations and well-being during the transition to parenthood. Current Opinion in Psychology, 25, 47-52. doi: 10.1016/j.c opsyc.2018.02.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steel C., Macdonald J., Schroder T. (2018). A systematic review of the effect of therapists’ internalized models of relationships on the quality of the therapeutic relationship. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 74(1), 5-42. doi: 10.1002/ jclp.22484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss B., Petrowski K. (2017). The role of therapists’ attachment in the process and outcome of psychotherapy. Castonguay L. G., Hill C. E. (Eds.), How and why are some therapists better than others? Understanding therapist effects (pp. 117-138). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick B. G., Fidell L. S. (2007). Using multivariate statistics (5th ed ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson Education, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Tasca G. A., Brugnera A., Baldwin D., Carlucci S., Compare A., Balfour L., Lafontaine M.-F. (2018). Reliability and validity of the Experiences in Close Relationships Scale-12: Attachment dimensions in a clinical sample with eating disorders. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 51(1), 18-27. doi: 10.1002/eat.22807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tasca G. A., Ritchie K., Conrad G., Balfour L., Gayton J., Lybanon V., Bissada H. (2006). Attachment scales predict outcome in a randomized controlled trial of two group therapies for binge eating disorder: An aptitude by treatment interaction. Psychotherapy Research, 16(1), 106-121. doi: 10.1080/10503300500090928 [Google Scholar]

- Taylor P., Rietzschel J., Danquah A., Berry K. (2015). Changes in attachment representations during psychological therapy. Psychotherapy Research, 25(2), 222-238. doi: 10.1080/10503307.2014.886791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toth-Kiraly I., Bothe B., Rigo A., Orosz G. (2017). An illustration of the Exploratory Structural Equation Modeling (ESEM) framework on the Passion Scale. Frontiers in Psychology, 8(1968). doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters E., Merrick S., Treboux D., Crowell J., Albersheim L. (2000). Attachment security in infancy and early adulthood: a twenty-year longitudinal study. Child Development, 71(3), 684-689. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wedding D., Eisenman R. (2006). Attachment and romantic relationships. PsycCRITIQUES, 51(40). doi: 10.1037/ a0003966 [Google Scholar]

- Wei M., Liao K. Y., Ku T. Y., Shaffer P. A. (2011). Attachment, self-compassion, empathy, and subjective well-being among college students and community adults. Journal of Personality, 79(1), 191-221. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2010. 00677.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Medical Association (2013). World medical association declaration of helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA, 310(20), 2191-2194. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]