Abstract

The papain-like protease (PLpro) is vital for the replication of coronaviruses (CoVs), as well as for escaping innate-immune responses of the host. Hence, it has emerged as an attractive antiviral drug-target. In this study, computational approaches were employed, mainly the structure-based virtual screening coupled with all-atom molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to computationally identify specific inhibitors of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) PLpro, which can be further developed as potential pan-PLpro based broad-spectrum antiviral drugs. The sequence, structure, and functional conserveness of most deadly human CoVs PLpro were explored, and it was revealed that functionally important catalytic triad residues are well conserved among SARS-CoV, SARS-CoV-2, and middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV). The subsequent screening of a focused protease inhibitors database composed of ∼7,000 compounds resulted in the identification of three candidate compounds, ADM_13083841, LMG_15521745, and SYN_15517940. These three compounds established conserved interactions which were further explored through MD simulations, free energy calculations, and residual energy contribution estimated by MM-PB(GB)SA method. All these compounds showed stable conformation and interacted well with the active residues of SARS-CoV-2 PLpro, and showed consistent interaction profile with SARS-CoV PLpro and MERS-CoV PLpro as well. Conclusively, the reported SARS-CoV-2 PLpro specific compounds could serve as seeds for developing potent pan-PLpro based broad-spectrum antiviral drugs against deadly human coronaviruses. Moreover, the presented information related to binding site residual energy contribution could lead to further optimization of these compounds.

Keywords: COVID-19, MERS-CoV, Molecular dynamic simulation, Pan-inhibitors, Papain-like protease, SARS-CoV, SARS-CoV-2, Virtual screening

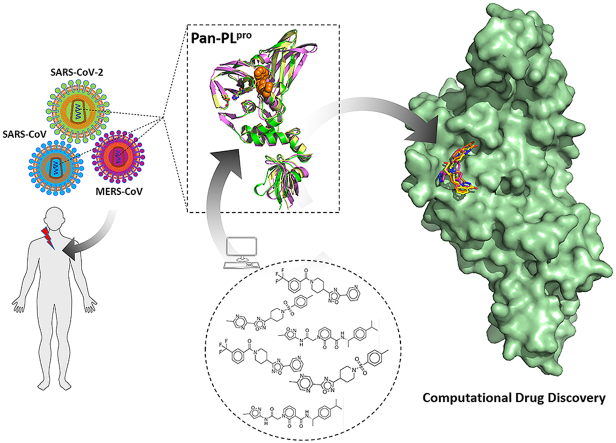

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

An integrated structure-based computational approach identified potential inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 PLpro.

-

•

Inhibitors’ binding and molecular interaction profiles were elucidated through MD simulation and energy decomposition analysis.

-

•

The screened inhibitors may lead to develop pan-PLpro based broad spectrum antiviral agents against the continuedly evolving Coronaviruses.

1. Introduction

Coronaviruses (CoVs) are enveloped RNA viruses covered with a non-segmented positive-sense RNA genome of 28–30 kb, known since the mid-1960s [1]. These viruses can infect a variety of hosts and can cause different respiratory, enteric, liver, and systemic diseases [1,2]. CoVs have the potential to transmit among animals and humans [3,4], which is evident from previous CoVs outbreaks. The severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) surfaced in 2002/2003 and resulted in 800 deaths [5]. Soon after the rise of this new viral infection, several new CoVs were uncovered [6]. In 2012, Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) was identified with the potential of human-to-human transmission [7,8]. The mortality rate of SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV was estimated to be around 15% for SARS-CoV [9] and 35% for MERS-CoV [10]. The currently emerged SARS-CoV-2 spread globally and turned into the pandemic of life threatening coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) [11]. To date, various potential SARS-CoV-2 drug-targets have been reported, and various efforts have been made to identify potential therapeutics as presented in recent reviews [[11], [12], [13], [14], [15]].

SARS-CoV-2 belongs to beta-CoVs, and is based on 800-kDa polypeptide, which is cleaved into structural and non-structural proteins upon translation [16,17]. 3-chymotrypsin-like protease (3CLpro) and papain-like protease (PLpro) are active partners in mediating this proteolytic processing. CoVs PLpro is grouped in the peptidase clan CA (family C16). The active site of PLpro consists of a typical catalytic triad, comprising Cys111–His272–Asp286 residues. CoVs PLpro is extensively studied, well-aligned, functional, and situated at the border of the thumb and palm sub-domains [18]. PLpro performs its proteolytic functions through its catalytic cysteine-protease cycle, in which Cys111 functions as a nucleophile, His272 acts as a general acid/base and Asp286 is linked with the histidine assisting it to align and help deprotonation of Cys111 [19]. CoVs 3CLpro and PLpro mainly process the viral polyprotein. However, PLpro has an extra role of extracting ISG15 and ubiquitin from the proteins of host-cell to help CoVs in the dodging of host-innate immune responses [19,20]. The C-terminal of ubiquitin molecule is suggested to accommodate a cleft in close proximity to the functional catalytic triad which consists of the conserved ubiquitin-specific protease residue, Asp 164, and two hydrophobic subsites S3 and S4. Targeting this pocket is preferable for the development of non-covalent SARS-CoV agents as it could allosterically block the active site by inducing loop closure [21]. Therefore, PLpro is a significant target for anti-CoVs drug designing [22]. PLpro based antiviral drugs may not only inhibit the CoVs replication cycle; they may also have an advantage in impeding the dysregulation of signalling cascades in CoVs infected cells, further leading to the death of un-infected neighbouring cells [19].

Up to date, there is no clinically approved drug or vaccine available to protect against recent COVID-19 [23,24]. For treating COVID-19 pneumonia, health officials are currently testing and evaluating existing anti-pneumonia treatments. Existing antivirals, including protease inhibitors (indinavir, saquinavir, and lopinavir/ritonavir), as well as RNA polymerase inhibitors, including remdesivir [[25], [26], [27]], are being tested against SARS-CoV-2. Recently, the in vitro antiviral competence analyses of a few FDA-approved as well as experimental drugs against clinical isolates of SARS-CoV-2, such as chloroquine and remdesivir, showed promising results [26]. However, to tackle the current COVID-19 pandemic, the development of wide-spectrum inhibitors against CoVs is a crucial strategy.

In recent years, the use of computational approaches for the discovery of small molecules has achieved importance in drug development [[28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33]]. Among various approaches, molecular docking has been extensively used for investigating the binding interactions of small molecules with the active sites of the target protein [[34], [35], [36], [37], [38]]. In antiviral drug discovery, hierarchical virtual screening approaches have already identified promising antiviral compounds against a broad range of viruses including influenza [39], Ebola [[40], [41], [42]], Dengue [[43], [44], [45], [46], [47], [48]], Zika Virus [[48], [49], [50]] and recently against CoVs [22,[51], [52], [53]], while others display the significance of molecular dynamics (MD) simulations in search for possible anti-viral [44,[54], [55], [56], [57], [58], [59], [60], [61]] and investigated drug resistance mechanisms [54,58,[62], [63], [64]]. PLpro is a highly conserved protease across CoVs [65] and considered as a potential target for SARS-CoV inhibitors with broad-spectrum antiviral activity [19]. In this contribution, a combined virtual screening approach and all-atom MD simulations were employed to investigate potential pan-PLpro inhibitors that could be further developed into broad-spectrum anti-COVID-19 drugs.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Proteins sequence and structure alignment

The functional evolutionary conserved residues of SARS-CoV, SARS-CoV-2 and MERS-CoV were recognized through sequence and structure alignments that could provide a structural motif for inhibitor design towards the discovery of pan-PLpro based broad spectrum anti-COVID-19 hits. Sequence and 3D structures of SARS-CoV-2 PLpro (Protein Data Bank (PDB): 6W9C), SARS-CoV PLpro (PDB: 3MJ5), and MERS-CoV PLpro (PDB: 4R3D) were retrieved from PDB [66]. Clustal Omega was used to align the PLpro sequences [67]. Structure alignment analysis was performed using PyMOL 1.3. tool [68].

2.2. Chemical libraries preparation

The Asinex protease inhibitor library composed of 6,968 compounds in three-dimensional (3D) representation and structural data format (SDF) was downloaded from the Asinex platform (https://www.asinex.com/protease/). The compounds were imported, and energy minimized using MMFF94 force field implemented in Open Babel [69]. Then compounds were prepared for screening using Autodock Tools [70] by adding the polar hydrogens and computing the gasteiger charges. All the optimized compounds were then saved as PDBQT files format for further molecular docking studies.

2.3. Structure-based virtual screening and molecular docking

The x-ray structure of SARS-CoV-2 PLpro in a resolution of 2.7 Å (PDB: 6W9C) was used for the docking purpose. Initially, the co-crystalized inhibitors and unwanted water molecules were removed by the Discovery Studio Visualizer [71]. The protein structure was prepared from PDB files into PDBQT using Autodock Tools. The polar-hydrogen atoms were included, and gasteiger charges were processed before docking. The structure-based virtual screening was carried out using Autodock-vina in PyRx 0.8 virtual screening tool [72]. Due to the high degree of sequence identity, the structure of SARS-CoV PLpro (PDB: 3MJ5) bound to GRL-0667S, a non-covalent inhibitor, was used to determine the target site within SARS-CoV-2 PLpro. The docking target site was determined by 3D structural alignment of SARS-CoV-2 PLpro (PDB: 6W9C) with SARS-CoV PLpro (PDB: 3MJ5). Hence, the grid box was generated by confining the essential residues lining this binding cavity. The three top hits were then re-docked individually using Autodock-Vina 1.1.2 to predict their binding modes and mechanism of interactions. The docking parameters were initially validated by redocking of native ligand GRL-0667S into the active site of SARS-CoV PLpro (PDB: 3MJ5). Also, these hits were docked against SARS-CoV PLpro (PDB: 3MJ5) and MERS-CoV PLpro (PDB: 4R3D) using the same method. Discovery Studio Visualizer 4.5 [73] and PyMOL 1.3 [68] programs were used for data and interaction analyses.

2.4. In silico drug-likeness analysis and ADMET profiling

The available bioinformatics tool SwissADME (available online: http://www.swissadme.ch/index.php) [74] was used for finding the drug-likeness properties. Based on the Lipinski’s rule of five [75], the properties that have been considered were molecular mass (MW), H-bond donor (HBD), H-bond acceptor (HBA), lipophilicity (log P), aqueous solubility and rotatable bonds (QP log S). PreADMET (https://preadmet.bmdrc.kr/) and pkCSM (http://biosig.unimelb.edu.au/pkcsm/) [76] servers were used to determine the ADMET (absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity) parameters of candidate compounds.

2.5. MD simulation

All atoms MD simulation of SARS-CoV-2 PLpro-inhibitor complexes and apo-protein were performed at 50 ns using GROMACS 2018 package [77]. The simulation was carried out using previously reported protocol [53,78]. Briefly, UCSF Chimera 1.14 was used to prepare the crystal structure of apo-SARS-CoV-2 PLpro and in complex with the top pose of docked-compounds for MD simulation [79]. The topology and parameters of compounds were obtained using SwissParam (http://www.swissparam.ch/). The simulation was conducted by applying OPLS-AA/L force-field to the systems in a 3D cubic box of TIP3P model of water molecules. Next, the simulated systems were equilibrated, and energy minimized by steepest-decent algorithm, followed by equilibration using Canonical (NVT) as well as (isothermal/isobaric) NPT ensembles. The MD simulation was analyzed for the root-mean square deviation (RMSD), root-mean square fluctuations (RMSF), potential binding energy, a radius of gyration (Rg), H-bond interaction analysis, solvent accessible surface area (SASA) and principal component analysis (PCA).

2.6. Binding free-energy calculations

The binding free-energies (ΔGbind) of the candidates were computed using the MM-PBSA algorithm [80], employed in AMBER 18, as previously described [81,82]. The molecular mechanics (MM) force fields were utilized to calculate the energy contributions of the receptor, ligand, and complex in a gaseous phase. The total binding free-energy (ΔGtotal) is determined as a total energy released from the ligand/protein complex which is contributed by molecular mechanics binding energy (ΔEMM) and solvation free energy (ΔGsol) using the following equations:

| ΔEMM = ΔEint + ΔEele + ΔEvdw |

| ΔGsol = ΔGpl + ΔGnp |

| ΔGtotal = ΔEMM + ΔGsol |

| ΔGbind (MM-PB(GB)SA) = ΔEMM + ΔGsol – TΔS |

In which, ΔEMM is divided into internal energy (ΔEint), electrostatic energy (ΔEele), and van der Waals energy (ΔEvdw), and the polar (ΔGp) and non-polar (ΔGnp) energy components contributed to total solvation free energy (ΔGsol). ΔGbind is the free energy of binding evaluated after entropic calculations (-TΔS), for both MM-GBSA and MM-PBSA methods. In order to estimate the decisive role of interacting residues towards ligand’s binding, per-residue energy decomposition analysis was performed using the MM-GBSA method, and binding energy was calculated as ΔGresidue using the following equation.

| ΔGresidue = ΔEMM + ΔGsol |

The ΔGresidue includes the total energy obtained from sidechain and backbone energy decomposition. These methods have been well demonstrated in binding free energy calculations [83] for antiviral inhibitors [84,85].

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Sequence, structural and functional analysis of PLpro for conserveness among coronaviruses

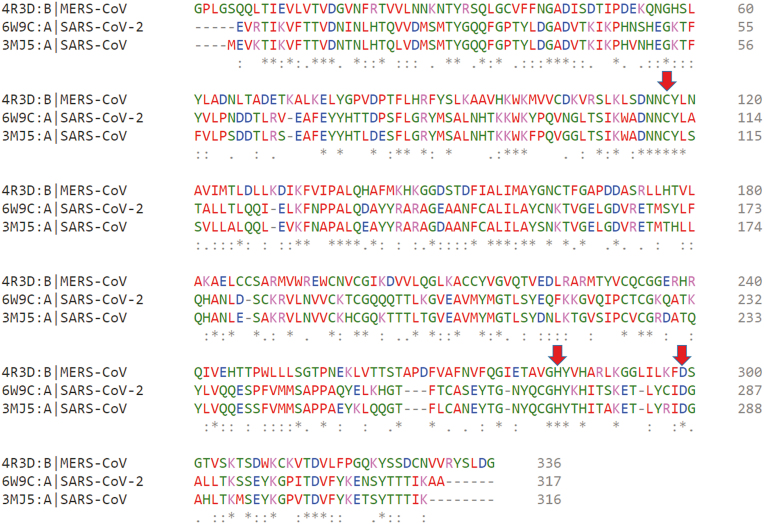

The sequence alignment of SARS-CoV-2 PLpro displayed an identity of 82.80% and only 30.00% with SARS-CoV PLpro and MERS-CoV PLpro, respectively (Fig. 1). However, the sequence alignment revealed that PLpro crucial catalytic triad residues of CoVs PLpro were well conserved amongst SARS-CoV-2 (Cys111-His272-Asp286), SARS-CoV (Cys112-His273-Asp287) and MERS-CoV (Cys112-His275-Asp294).

Fig. 1.

Multiple sequence alignments of SARS-CoV-2 PLpro with SRAS-CoV PLpro and MERS-CoV PLpro. The conserved catalytic triad residues (Cys111-His272-Asp286) within SARS-CoV-2, (Cys112-His273-Asp287) within SARS-CoV, and (Cys112-His275-Asp294) within MERS-CoV are highlighted with red color arrows.

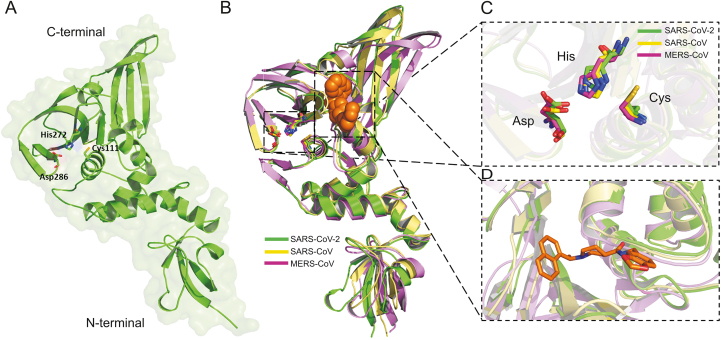

In consistence with this, the structural alignment/superposition of all three human CoVs PLpro revealed that the PLpro of SARS-CoV-2 (Fig. 2A) adapted the same folding pattern as the PLpro of SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV (Fig. 2B). Interestingly, the functionally well-conserved catalytic triad residues within the catalytic pockets of PLpro among SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV, and MERS-CoV present at the identical place in the catalytic sites with RMSD 1.342 Å as presented in Figs. 2B and C. To determine the targetable binding site within the SARS-CoV-2 PLpro, the crystal structure of SARS-CoV PLpro in complex with a potent non-covalent inhibitor, GRL-0667S, was used for structural alignment. The binding site appeared as an allosteric site close to the active catalytic site (Figs. 2B and D).

Fig. 2.

(A) The 3D structures of SARS-CoV-2 PLpro enzymes. The catalytic triad residues Cys111-His272-Asp286 were shown green sticks. (B) The overlapping of the 3D structures of PLpro enzymes of SARS-CoV-2 (green) (PDB: 6W9C), SRAR-CoV (yellow) (PDB: 3MJ5) and MERS-CoV (purple) (PDB: 4R3D). The conserved catalytic triad residues with each structure were shown in sticks. GRL-0667S within the binding site of SRAS-CoV PLpro was shown in orange spheres. (C) The overlapping of the catalytic triad residues of PLpro within the active sites of SARS-CoV-2 (green sticks), SRAR-CoV (cyan sticks), and MERS-CoV (pink sticks). (D) Close view to the targetable binding pocket within PLpro enzyme based on the binding mode of GRL-0667S with SARS-CoV PLpro.

3.2. Virtual screening of protease inhibitor library

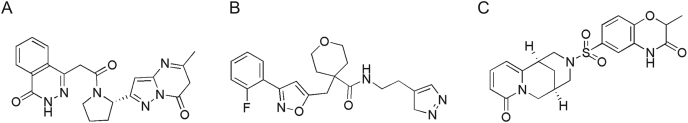

The integrated computational method comprising virtual high throughput screening, molecular docking, and MD simulation is a significant approach for the exploration of potential inhibitors against a target protein [22,28,78,86]. In order to find out potential pan-PLpro based anti-SARS-CoV-2 inhibitors, the structure-based screening was carried out against a virtual library of ∼7,000 protease inhibitors. By applying a docking score cutoff of lower than −8.5 kcal/mol, three potential hits (Fig. 3) were selected with maximum scores, which were found to interact well with the active site residues. These include ADM_13083841 ((S)-4-(2-(2-(5-methyl-7-oxo-6,7-dihydropyrazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidin-2-yl)pyrrolidin-1-yl)-2-oxoethyl)phthalazin-1(2H)-one), AEM_16392818LMG_15521745 (N-(2-(3H-pyrazol-4-yl)ethyl)-4-((3-(2-fluorophenyl)isoxazol-5-yl)methyl)tetrahydro-2H-pyran-4-carboxamide) and SYN_15517940 ((R)-2-methyl-6-(((1R,5R)-8-oxo-1,5,6,8-tetrahydro-2H-1,5-methanopyrido[1,2-a] [1,5]diazocin-3(4H)-yl)sulfonyl)-2H-benzo[b] [1,4]oxazin-3(4H)-one), with binding energy score of −8.9, −8.7, −8.7 kcal/mol, respectively, and considered as potential inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 PLpro (Table 1). These three hit compounds were used to further evaluate the physiochemical and ADMET properties.

Fig. 3.

Chemical structures of screened hits; (A) ADM_13083841, (B) LMG_15521745 and (C) SYN_15517940.

Table 1.

Properties profile of candidate compounds.

| Name (ID) | Binding score (kcal/mol) | Hydrogen bond interaction | Hydrophobic interaction |

|---|---|---|---|

| ADM_13083841 | −8.9 | Lys157, Tyr264, Thr301 | Leu162, Met208 |

| LMG_15521745 | −8.7 | Lys157, Tyr264, Thr301 | Leu162, Pro248 |

| SYN_15517940 | −8.7 | Arg166, Thr264, Thr301 | Leu162, Met208, Pro248 |

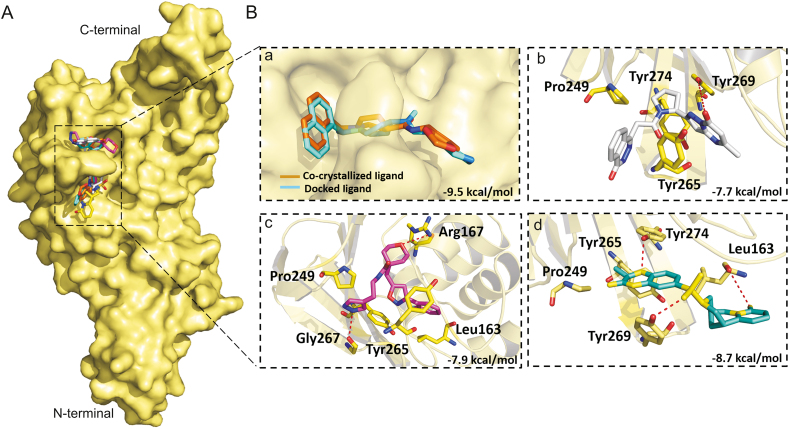

3.3. Analysis of screened inhibitor interaction

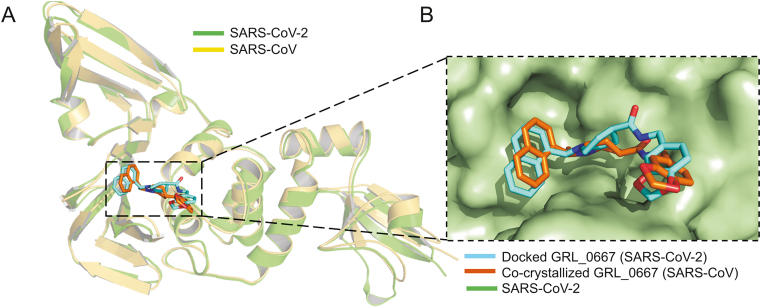

In order to understand the binding mode and mechanism of interaction of these compounds with SARS-CoV-2 PLpro, an unbiased flexible docking of these compounds into the active site of the SARS-CoV-2 PLpro enzyme was performed. The docking and scoring functions had been validated before the docking was carried out. Since SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 shared significant sequence similarity and similar 3D structure, the validation was achieved by docking the GRL-0667S, a potent SARS CoV PLpro inhibitor with an IC50 value of 0.32 ± 0.01 μM, into the same site within SARS-CoV-2 [87]. The latter approach was made to evaluate the ability of the docking protocol to predict the biologically active conformation. Moreover, as shown in Fig. 4, both the docked conformation within SARS-CoV-2 and co-crystal ligand within SARS-CoV adapted a similar binding mode within the target site, validating the robustness of the docking protocol.

Fig. 4.

Validation of the docking protocol. (A) Ribbon representation for superimposition of docked GRL-0667S (cyan) into SARS-CoV-2 PLpro (green) (PDB: 6W9C), and co-crystalized structure (orange) of GRL-0667S within the active site of SARS CoV PLpro (yellow) (PDB: 3MJ5). (B) Superimposition of co-crystallized (orange) and best-docked pose (cyan) of inhibitor GRL-0667S in the active site of SARS-CoV-2 PLpro (PDB ID: 6W9C, green molecular surface).

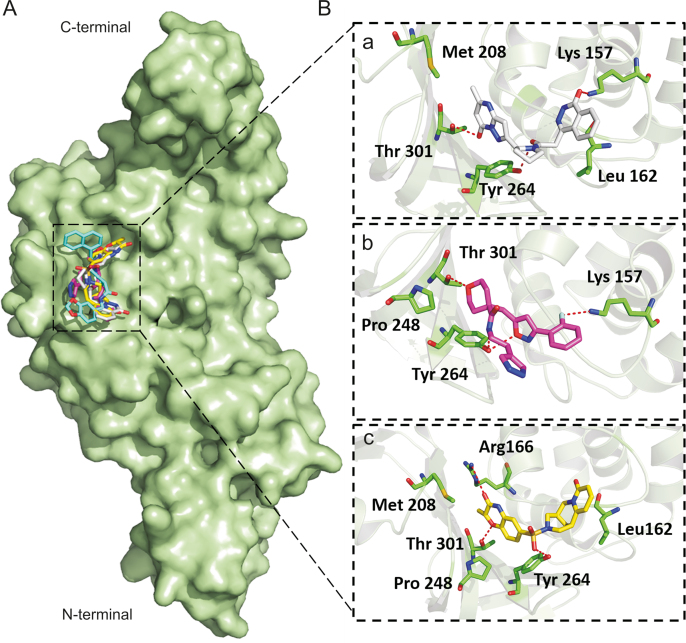

Flexible docking revealed that the three compounds adopted the same binding mode within the binding pocket and interacted through H-bonds as shown in Fig. 5. Among the conserved H-bonds interactions, the terminal pyrimidin-4-one of ADM_13083841, central oxane moiety of LMG_15521745 and terminal benzoxazines moiety of SYN_15517940 established one H-bond each with the side chain oxygen atom of Thr301. The second conserved H-bond was established between the side chain oxygen of Tyr264 and the central pyrrolidine moiety of ADM_13083841, oxazole moiety of LMG_15521745, and sulfonamide moiety of SYN_15517940. Apart from these, ADM_13083841 and LMG_15521745 also established conserved interactions with the side-chain nitrogen (N) of Lys157, while SYN_15517940 established H-bond with the side-chain N of Arg166. Moreover, these compounds also formed a conserved network of hydrophobic interactions with the surrounding residues, including Leu162, Asp164, Met208, Pro247, Pro248, and Tyr268. The molecular interaction analyses were found in agreement with the co-crystallized inhibitors of SARS-CoV-PLpro (PDB ID: 3E9S and 3MJ5) [87] (Table 1).

Fig. 5.

Binding modes and molecular interactions of screened compounds with SARS-CoV-2 PLpro (PDB: 6W9C). (A) Surface representation of the binding mode of GRL-0667S (cyan), ADM_13083841 (white), LMG_15521745 (pink) and SYN_15517940 (yellow) to SARS-CoV-2 PLpro (green). (B) The mechanism of molecular interactions of (a) ADM_13083841 (white), (b) LMG_15521745 (pink) and (c) SYN_15517940 (yellow) to SARS-CoV-2 PLpro (green).

3.4. ADMET screening and drug-ability results

ADMET-based drug scan tool at the SwissADME server was used to evaluate the drug-likeness of the proposed SARS-CoV-2 PLpro inhibitors [74]. ADM_13083841 (C21H20N6O3) is a phthalazinone derivative with the log P value of 2.04 and molecular weight of 404.42 g/mol. The compound has six hydrogen-bond acceptor (HBA) and one hydrogen-bond donor (HBD) atoms. Another oxazole based compound selected from the docked molecules is LMG_15521745 (C21H23FN4O3) with the log P value of 3.02 and molecular weight of 398.43 g/mol. It contains seven HBA atoms and one HBD. SYN_15517940 (C20H21N3O5S) has a log P value of 2.30 and a molecular weight of 415.46 g/mol, together with six HBA atoms and one HBD (Table 2).

Table 2.

Drug-likeness properties of identified compounds.

| Name | MW (g/mol) | HBD | HBA | Log P | RB | Log S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADM_13083841 | 404.42 | 1 | 6 | 2.04 | 4 | −2.84 Soluble |

| LMG_15521745 | 398.43 | 1 | 7 | 3.02 | 8 | −3.54 Soluble |

| SYN_15517940 | 415.46 | 1 | 6 | 2.30 | 2 | −2.62 Soluble |

MW: molecular weight.

For further validation of the drug likeliness capability of target compounds, all these compounds were subjected to the PreADMET and pkCSM servers, which have five main parameters (absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity) for assessment. These five parameters were then assessed according to the number of thresholds. All the three compounds successfully passed the criteria of drug-ability (Table 3).

Table 3.

ADMET profiling for absorption, metabolism and toxicity parameters of identified compounds.

| Model | ADM_13083841 | LMG_15521745 | SYN_15517940 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Absorption and distribution | |||

| Blood-brain barrier | No | No | No |

| Human intestinal absorption | High | High | High |

| Caco-2 permeability | Yes | Yes | No |

| P-glycoprotein inhibitor | Substrate/inhibitor | Non-substrate/inhibitor | Non-substrate/non-inhibitor |

| Organic cation transporter 2 (OTC2) | Non-inhibitor | Non-inhibitor | Non-inhibitor |

| Metabolism | |||

| CYP450 2C9 | Non-inhibitor | Inhibitor | Non-inhibitor |

| CYP450 2D6 | Non-substrate/non-inhibitor | Non-substrate/non-inhibitor | Non-substrate/non-inhibitor |

| CYP450 3A4 | Substrate/non-inhibitor | Substrate/inhibitor | Substrate/non-inhibitor |

| CYP450 1A2 | Non-inhibitor | Non-inhibitor | Non-inhibitor |

| CYP450 2C19 | Inhibitor | Inhibitor | Non-inhibitor |

| Toxicity | |||

| Acute algae toxicity | 0.0264273 | 0.0621567 | 0.158197 |

| Ames test | Mutagen | Mutagen | Non-mutagen |

| Carcinogenicity (Mouse) | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| Carcinogenicity (Rat) | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| Acute daphina toxicity | 0.12599 | 0.364329 | 0.661198 |

| In vitro hERG inhibition | High risk | High risk | Medium risk |

| Acute fish toxicity (medaka) | 0.0354928 | 0.227324 | 0.836634 |

| Acute fish toxicity (minnow) | 0.0544461 | 0.248798 | 0.94807 |

| Ames TA100 (+S9) | Positive | Negative | Negative |

| Ames TA100 (-S9) | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| Ames TA1535 (+S9) | Negative | Positive | Negative |

| Ames TA1535 (-S9) | Negative | Positive | Negative |

3.5. MD simulation

MD simulation is a widely used computational method to analyze the dynamic behavior and stability of a ligand/protein complex under different conditions [30,53,88,89]. All atoms MD simulations were carried out on the initial conformation of the hit compounds-PLpro complexes obtained after the docking in the solvated states at 50 ns.

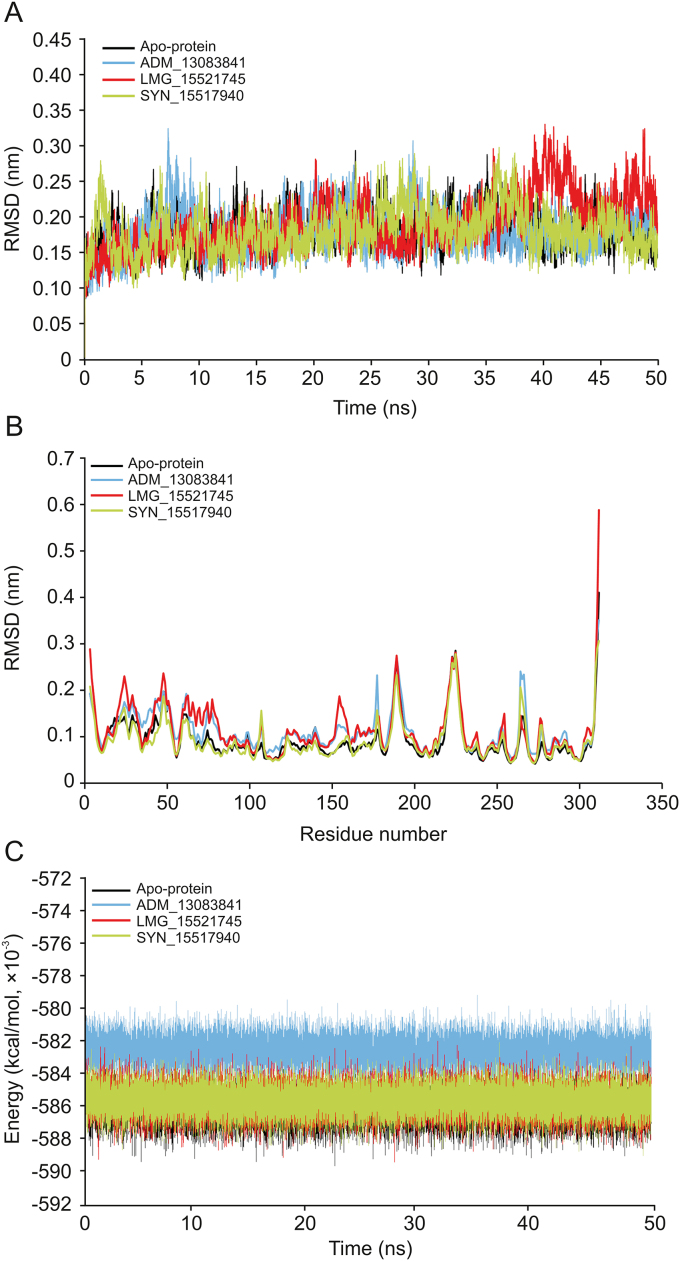

3.5.1. RMSD, RMSF and potential binding energy

The RMSD computes the direct changes in the atoms of superimposed proteins and is an acceptable approach to assess the stability of protein/ligand complexes [[90], [91], [92], [93]]. The RMSD values of the Cα-backbone atoms of SARS-CoV-2 PLpro in complex to the three PLpro potential inhibitors were calculated with respect to the initial structure and compared with apo-protein in an unbound form. The RMSD values steadily increased in the beginning and remained converged throughout the simulation period, especially for ADM_13083841 and LMG_15521745 complexes. Similarly, the RMSD values of apo-protein reached an equilibrium after an initial increase within the first 5 ns and converged between 0.12 and 0.3 nm throughout the simulation course. The average RMSD values for the last 45 ns for apo-protein, ADM_13083841, LMG_15521745, and SYN_15517940 complexes were 0.18 ± 0.03, 0.18 ± 0.03, 0.19 ± 0.04 and 0.18 ± 0.03 nm, respectively (Fig. 6A).

Fig. 6.

(A) The root mean square deviation (RMSD) of C–Cα–N backbone vs. simulation time for solvated SARS-CoV-2 PLpro in apo-state and in complex with the three candidate compounds over the time of 50 ns MD simulation. (B) The root mean square fluctuation (RMSF) of SARS-CoV-2 PLpro in apo-state and in complex with the three candidate compounds. (C) The potential energy for SARS-CoV-2 PLpro in apo-state and in complex with the candidate compounds over the time of 50 ns MD simulation.

The RMSF measured the local protein flexibility and proved to be an excellent parameter to investigate the protein’s residual flexibility over the simulation period [90,92]. The time average of protein backbone RMSF values of the 315 amino acids of SARS-CoV-2 PLpro protein with and without the three candidate compounds was calculated over the 50 ns simulation period. Normal fluctuations in the constituent residues of SARS-CoV-2 PLpro were observed for apo-protein and all three complexes, PLpro- ADM_13083841, PLpro- LMG_15521745 and PLpro- SYN_15517940, and were plotted to compare the residual flexibility. As shown in Fig. 6B, major fluctuations were observed mainly in the loop regions (residue nos. 185–200 and 220–230), located away from the binding pocket. The average RMSF values were calculated as 0.09 ± 0.05, 0.11 ± 0.05, 0.11 ± 0.06 and 0.09 ± 0.04 nm for apo-protein, ADM_13083841, LMG_15521745 and SYN_15517940, respectively.

Furthermore, the potential energy over the simulation time for the three complexes and apo-protein was calculated. The results indicated that the three complexes remained in a stable pattern throughout the 50 ns simulations, as shown in Fig. 6C. These RMSD, RMSF, and potential energy MD simulation results confirmed the stability of all selected compounds at the catalytic-site of SARS-CoV-2 PLpro.

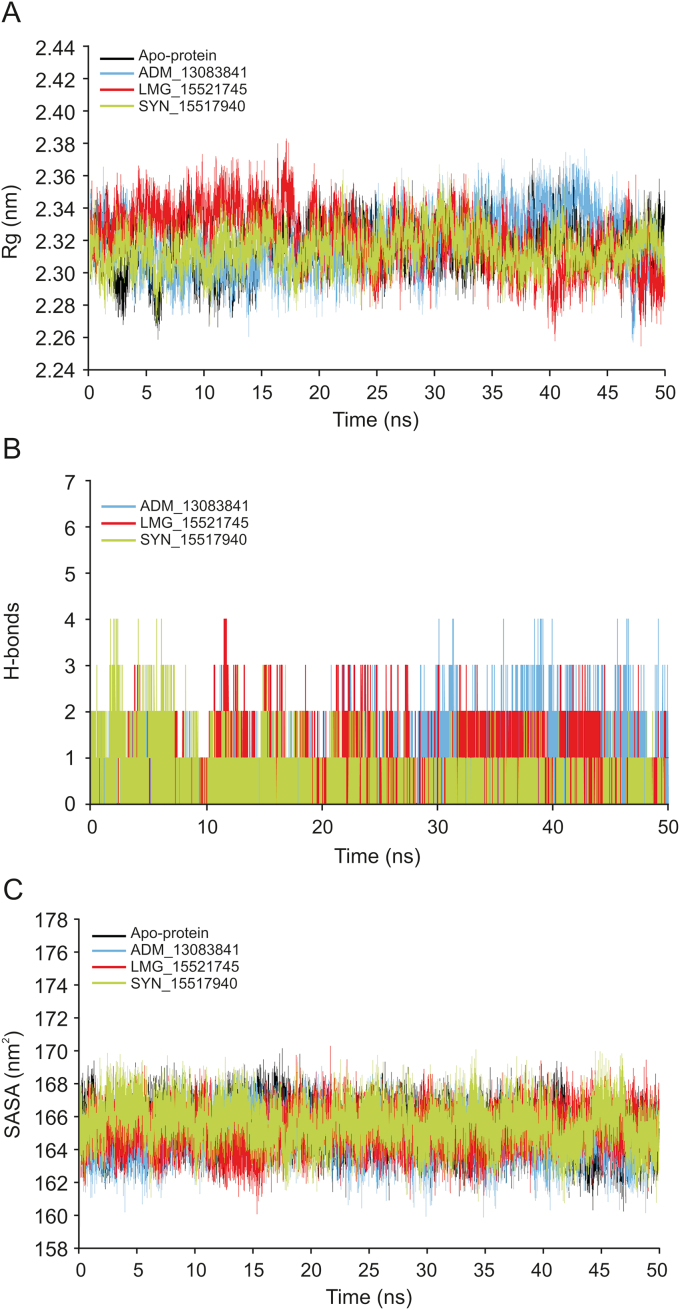

3.5.2. Rg, hydrogen bond interaction and SASA analysis

The Rg is a parameter for evaluating the behavior and stability of the biological systems during the MD trajectories by measuring the compactness of biomacromolecules’ structures [94,95]. The Rg can also be used as an indicator of whether the complex will maintain folded conformation after the MD simulation. The Rg values of the three complexes and apo-protein were stabilized after the initial increase at 5 ns, supporting the RMSD results that systems had reached the equilibrium state (Fig. 7A). The average Rg values for the three complexes and apo-protein remained relatively consistent for the last 45 ns, indicating a stably folded structure with an average value of 2.32 ± 0.01, 2.32 ± 0.02, 2.32 ± 0.02 and 2.31 ± 0.01 nm for apo-protein, ADM_13083841, LMG_15521745, and SYN_15517940, respectively.

Fig. 7.

(A) The radius of gyration (Rg) of SARS-CoV-2 PLpro in apo-state and in complex with the three candidate compounds during 50 ns MD simulation. (B) Plot of number of hydrogen bond within the SARS-CoV-2 PLpro in complex with the three candidate compounds during 50 ns MD simulation. (C) Plot of solvent accessible surface area (SASA) of SARS-CoV-2 PLpro in apo-state and in complex with the three candidate compounds over the time of 50 ns MD simulation.

Hydrogen bonds play a crucial role as stabilizing forces for a ligand-protein complex [[90], [91], [92]]. The total number of hydrogen bonds formed between the three candidate compounds and SARS-CoV-2 PLpro is shown in Fig. 7B. All candidate compounds can make up to four stable hydrogen bonds with SARS-CoV-2 PLpro throughout the simulation period supporting the docking results. These bonding parameters represented that all candidate compounds may bind effectively and tightly to the SARS-CoV-2 PLpro.

The SASA is a tool to measure the water accessible proportion of the biomolecule surface [96]. The calculation of SASA value is a useful tool to predict the degree of the conformational changes which resulted due to complex interaction. The calculated average SASA values for the last 45 ns simulation time were 165.27 ± 1.22, 164.78 ± 1.21, 165.18 ± 1.18, and 165.51 ± 1.27 nm2, respectively (Fig. 7C). These results suggested there were no observed changes in the accessibility area of all three systems over the 50 ns simulation time. Thus, in terms of SASA analysis, the relative stability of our protein-ligand complexes has been concluded.

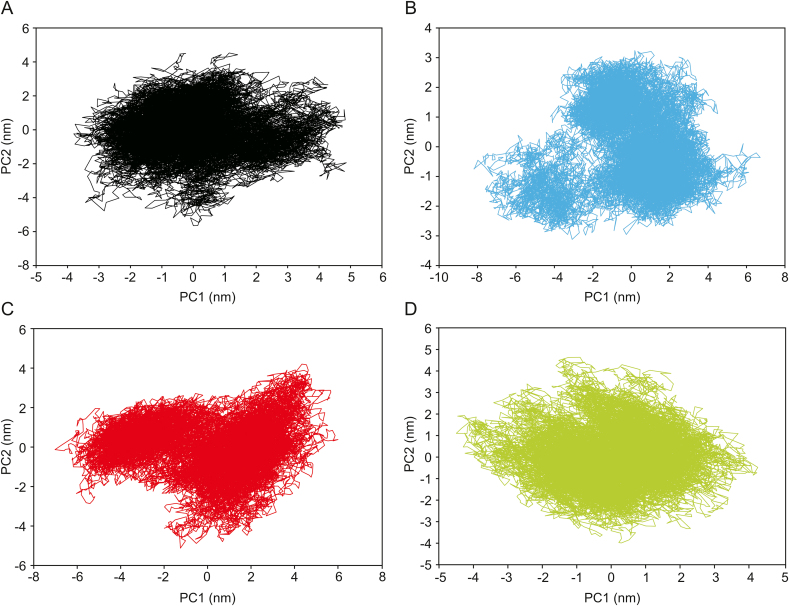

3.5.3. PCA

The PCA analysis was performed to identify conformational changes that accompanied the ligands binding within different protein/ligand complexes. In the current study, the first two principal components (PC1 and PC2) were selected for predicting the protein motions. The projection of two eigenvectors for apo-protein as well as all three complexes, PLpro-ADM_13083841, PLpro-LMG_15521745, and PLpro-SYN_15517940 is shown (Fig. 8). Generally, the complex that occupies a more phase-space with a non-stable cluster and complex that occupies less phase-space with a stable cluster represented a less stable complex and a more stable complex, respectively. From the graphs, the apo-protein, as well as the three complexes, occupied less phase-space. The clusters shifting were from −4 to 5 nm in case of apo-protein, −8 to 6 nm in case of ADM_13083841. In contrast, the clusters shifting were from −6 to 6 and −4 to 4 in cases of LMG_15521745 and SYN_15517940, respectively. With respect to apo-protein values, all complexes showed a very stable complex.

Fig. 8.

Two-dimensional principle component analysis (PCA) projections of trajectories obtained from 50 ns MD simulations. (A) Apo-protein, (B) ADM_13083841, (C) LMG_15521745, and (D) SYN_15517940.

3.6. Predicted binding free energy calculations

The MM/GBSA and MM/PBSA are both end-point methods and present more physically meaningful information than docking scoring functions. These methods have been extensively utilized in the identification of potential antiviral inhibitors [83,84,97,98]. The absolute energy of binding (ΔGbind) of all three hit compounds together with co-crystallized PLpro inhibitor, GRL-0667S [87], was predicted through mechanics/Poisson–Boltzmann (generalized born) surface area (MM/PB(GB)SA) method on 50 snapshots extracted from the last 20 ns of the simulation period. It is important to note that we also incorporated entropic contributions (-TΔS) in ligand binding, which are computationally expensive in the MMPBSA method and give better accuracy [99]. Moreover, entropy effects play an essential role in protein-ligand interactions [100]. The calculations are tabulated in Table 4.

Table 4.

ΔGbind values of ADM_13083841, LMG_15521745 and SYN_15517940 in complex with SARS-CoV-2 PLpro calculated by the MM/PB(GB)SA method.

| Energy component | ADM_13083841 | LMG_15521745 | SYN_15517940 | GRL-0667S |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MM (gas term) | ||||

| ΔEvdw | −46.12 | −41.3 | −39.88 | −43.7 |

| ΔEele | −14.1 | −16.24 | −15.3 | −12.39 |

| ΔEMM | −60.22 | −57.54 | −55.18 | −56.09 |

| (−)TΔS | 24.3 | 21.22 | 21.9 | 20.91 |

| PBSA (solvation term) | ||||

| ΔGp(PBSA) | 35.9 | 37.26 | 31.27 | 34.76 |

| ΔGnp(PBSA) | −5.07 | −5.11 | −5.1 | −5.39 |

| ΔGsol(PBSA) | 30.83 | 32.15 | 26.17 | 29.37 |

| GBSA (solvation term) | ||||

| ΔGp(GBSA) | 29.45 | 31.37 | 27.23 | 31.38 |

| ΔGnp(GBSA) | −5.42 | −5.89 | −6.91 | −6.02 |

| ΔGsol(GBSA) | 24.03 | 25.48 | 20.32 | 25.36 |

| Binding free energy | ||||

| ΔGbind(MM/PBSA) | −5.09 | −4.17 | −7.11 | −5.81 |

| ΔGbind(MM/GBSA) | −11.89 | −10.84 | −12.96 | −9.82 |

Note: The co-crystalized complex GRL-0667S/SARS-CoV-2 PLpro (PDB: 3MJ5) was used as positive control. ΔGbind is the sum of molecular mechanics energy (ΔEMM) which is the gas term, and solvation free energy (ΔGsol). Both ΔEMM and ΔGsol are further divided into internal energy (ΔEint), electrostatic energy (ΔEele), and van der Waals (ΔEvdw) energy, and polar (ΔGp) and non-polar (ΔGnp) contributions to the solvation free energy. Solvation term were included from both MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA methods. These calculations were executed with the incorporation of entropic term (TΔS) by the following equation: ΔGbind (MM-PB(GB)SA) = ΔEMM + ΔGsol – TΔS.

According to the MM/PB(GB)SA calculations, van der Waals (ΔEvdW) interaction was the main driving force in complex stabilization with ADM_13083841 (ΔEvdW = −46.12 kcal/mol), LMG_15521745 (ΔEvdW = −41.3 kcal/mol) and SYN_15517940 (ΔEvdW = −39.88 kcal/mol), and was about 1–2 fold stronger than electrostatic attraction energy (ΔEele) predicted to be −14.1, −16.24, and 15.3 kcal/mol, respectively. Therefore, it was found that compounds interacted mainly through van der Waals interactions and these findings are in agreement with the co-crystalized GRL-0667S (ΔEvdW = −43.7 and ΔEMM = −12.39) [87]. Together with the solvation effect in ADM_13083841 (ΔGsol(PBSA) = 30.83; ΔGsol(GBSA) = 24.03 kcal/mol), LMG_15521745 (ΔGsol(PBSA) = 32.15; ΔGsol(GBSA) = 25.48 kcal/mol) and SYN_15517940 (ΔGsol(PBSA) = 26.17; ΔGsol(GBSA) = 20.32 kcal/mol) complexed with SARS-COV-2 PLpro and incorporation of entropic terms, the absolute ΔGbind accounted for −5.09 (ADM_13083841), −4.17 (LMG_15521745) and −7.11 kcal/mol (SYN_15517940) as per MM-PBSA (ΔGbind(MM/PBSA)) approach and values of 11.89 (ADM_13083841), −10.84 (LMG_15521745) and −12.96 kcal/mol (SYN_15517940) were taken from the MM-PBSA (ΔGbind(MM/PBSA)) approach. The obtained ΔGbind values of all three compounds were in agreement with the co-crystalized GRL-0667S, which revealed relatively similar values by MM/PBSA (−5.81 kcal/mol) and MM/GBSA (−9.82 kcal/mol) methods.

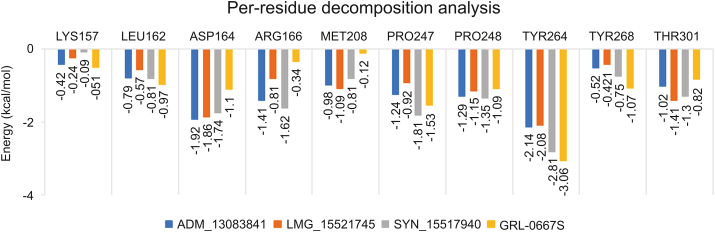

3.6.1. Per-residue decomposition analysis

In order to evaluate the binding role of key interacting residues of the active site, (ΔGresidue) calculations were performed using the MMGBSA method. The total energy decomposition values associated with ligand binding is presented in Fig. 9. We highlight here only the significant energy contributing residues in ligand binding. Briefly, the obtained results revealed that residues, including Asp164, Met208, Pro247, Pro248, Tyr264 and Thr301 located in the active site of SARS-COV-2 PLpro, were found important for interactions with ADM_13083841, LMG_15521745, and SYN_15517940. Among these, the residual decomposition analysis revealed the favorable contributions (<−1.7 kcal/mol) of Asp164, which exhibited ΔGresidue of −1.92, −1.86, and −1.74 kcal/mol, Tyr264 which exhibited ΔGresidue of −2.14, −2.08, and −2.81 kcal/mol with ADM_13083841, LMG_15521745 and SYN_15517940, respectively. Moreover, Tyr264 was also found interacting through H-bonds in all three complexes (Fig. 5).

Fig. 9.

Per-residue decomposition analysis using MM-GBSA methods and highly interacting binding site residues are displayed together with ΔGresidue derived from last 20 ns of MD simulations.

In comparison, the ΔGresidue values of co-crystallized GRL-0667S showed a relatively similar trend. Hence, ΔGresidue energies of highly interacting residues suggested that the molecular structures of all three compounds fitted well inside the active-site of SARS-COV-2 PLpro. Moreover, the obtained results after residual decomposition analysis were in accordance with the complex stability analysis through MD simulation, where the stable RMSD was achieved due to these pairwise interactions throughout the simulation period. Hence, we hypothesized that these critically important active site residues might be crucial in inhibitor recognition for the development of SARS-COV-2 PLpro inhibitors and could lead to further optimization of these compounds.

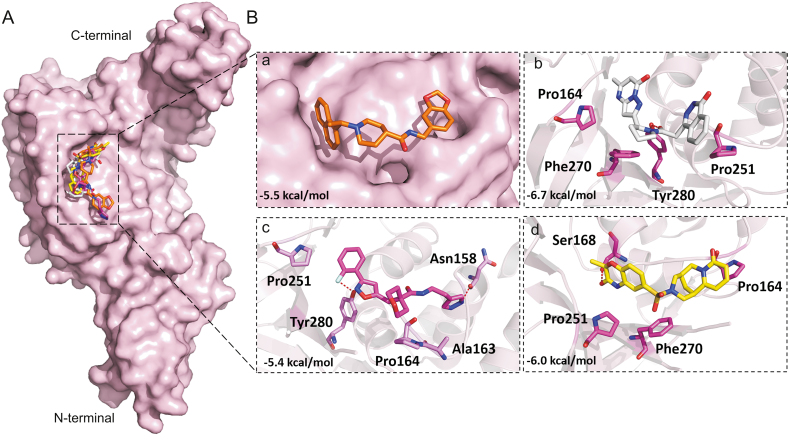

3.7. Molecular docking of screened hits with SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV PLpros

Disulfiram is an FDA approved drug used to treat chronic alcoholism. Previous research reported that disulfiram can inhibit SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV PLpros as an allosteric, competitive or mixed inhibitor [101]. Disulfiram has also been proposed for the treatment of SARS-CoV-2 [[102], [103], [104]]. Similarly, previous studies reported that lopinavir showed promising results against MERS-CoV [[105], [106], [107], [108]] and SARS-CoV [[109], [110], [111]], and currently it is under clinical trials for COVID-19 treatment [11,[112], [113], [114]]. Lopinavir is an FDA approved serine protease inhibitor used to treat HIV-1 infection [115]. Therefore, to test the hypothesis and validate the possibility of pan-PLpro based broad-spectrum inhibitors, next we determined the ability of the selected compounds to bind to the SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV PLpros, by the validated flexible docking approach into the same target site. Interestingly, these compounds showed high binding affinity toward SARS-CoV PLpro with binding energy scores ranged from −8.7 to −7.9 kcal/mol (Fig. 10). However, the binding energy scores of these compounds were low in the case of MERS-CoV, ranging from −5.9 to −6.7 kcal/mol, indicating that their activity toward SARS-CoV might be greater than the activity against MERS-CoV (Fig. 11). This could be due to the structural difference of MERS-CoV blocking loop 2 [116].

Fig. 10.

Binding modes and molecular interactions of screened compounds with SARS-CoV PLpro (PDB: 3MJ5). (A) Surface representation of the binding mode of co-crystalized GRL-0667S (cyan), docked GRL-0667S (orange), ADM_13083841 (white), LMG_15521745 (pink) and SYN_15517940 (green) to SARS-CoV PLpro (yellow). (B) The mechanism of molecular interactions of compounds to SARS-CoV PLpro. Close view to the binding mode of (a) co-crystalized GRL-0667S (cyan) and docked GRL-0667S (orange) to SARS-CoV PLpro, (b) ADM_13083841 (white), (c) LMG_15521745 (pink) and (d) SYN_15517940 (green) to SARS-CoV-2 PLpro.

Fig. 11.

Binding modes and molecular interactions of screened compounds with MERS-CoV PLpro (PDB: 4R3D). (A) Surface representation of the binding mode of docked GRL-0667S (orange), ADM_13083841 (white), LMG_15521745 (pink) and SYN_15517940 (yellow) to MERS-CoV PLpro (pink). (B) The mechanism of molecular interactions of compounds to MERS-CoV PLpro. Close view to the binding mode of (a) docked GRL-0667S (orange), (b) ADM_13083841 (white), (c) LMG_15521745 (pink) and (d) SYN_15517940 (green) to MERS-CoV PLpro.

Our effort to target the deadliest human CoVs (SARS-CoV, SARS-CoV-2 and MERS-CoV) PLpro concurrently by investigating their conservation (structural and functional) produced significant results. The present study identified three small-molecule protease inhibitors with great capability of drug leads, capable of inhibiting PLpro of SARS-CoV-2. These set of compounds could function as broad-spectrum pan-PLpro inhibitors against deadly human CoVs infections. This is critically important against constantly evolving CoVs. The benefits of treatment strategies involving pan-inhibitors have already been reported in the case of Dengue virus [28,117], HCV [[118], [119], [120], [121]], and HIV [122]. The screened inhibitors in the present study may lead towards a medicinal solution against the variety of constantly evolving CoVs by effectively targeting/hindering the proteolytic role of their PLpros. Therefore, our findings warrant further experimental work on screened pan-PLpro inhibitors for further drug optimization.

4. Conclusions

This comprehensive study offers an integrated computational approach towards the discovery of three novel hit compounds, screened from a focused library of ∼7,000 compounds having a diverse scaffold that can specifically target SARS-COV-2 PLpro, which permits in vitro evaluations. These three compounds, ADM_13083841, LMG_15521745, and SYN_15517940, were selected for further computational studies to gain a deep insight into their binding mode, mechanism of molecular interaction, and ADMET analysis. The in-depth structural exploitation of key residues of the active site together with the dynamic scaffolds of hit compounds adopted after 50 ns MD simulations offered the way to design broad-spectrum inhibitors against deadly human CoVs. The structural/functional conservation of SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV, and SARS-CoV-2 revealed strikingly similar conformations of active site residues. Altogether, the identification of highly contributing residues towards overall ligand binding energy might provide an excellent platform to further enhance the inhibitor recognition potential of SARS-COV-2 PLpro. Although the present study lacks in silico binding mode validation, the structural evidence obtained from this computational study has surfaced the way in the designing of pan-PLpro based inhibitors as broad-spectrum antiviral agents to combat SARS-CoV-2 and other pathogenic human coronaviruses.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Starting Research Grant for High-level Talents from Guangxi University and the Postdoctoral Project from Guangxi University. Authors would like to thank Guangxi University, Prince Sattam Bin Abdulaziz University and University of Leuven for providing necessary facilities to conduct this research.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Xi'an Jiaotong University.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpha.2020.08.012.

Contributor Information

Mubarak A. Alamri, Email: m.alamri@psau.edu.sa.

Ling-Ling Chen, Email: llchen@mail.hzau.edu.cn.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Lu G., Wang Q., Gao G.F. Bat-to-human: spike features determining ‘host jump’of coronaviruses SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV, and beyond. Trends Microbiol. 2015;23:468–478. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2015.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahmed T., Noman M., Almatroudi A. Coronavirus disease 2019 assosiated pneumonia in China: current status and future prospects. Preprints. 2020 doi: 10.20944/preprints202002.0358.v3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang L.-F., Walker P.J., Poon L.L. Mass extinctions, biodiversity and mitochondrial function: are bats ‘special’as reservoirs for emerging viruses? Curr. Opin. Virol. 2011;1:649–657. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2011.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mackenzie J.S., Jeggo M. Reservoirs and vectors of emerging viruses. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2013;3:170–179. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2013.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization; 2003. Consensus document on the epidemiology of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS)https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/70863 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Woo P., Huang Y., Lau S. Coronavirus genomics and bioinformatics analysis. Viruses. 2010;2:1804–1820. doi: 10.3390/v2081803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raj V.S., Osterhaus A.D., Fouchier R.A. MERS: emergence of a novel human coronavirus. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2014;5:58–62. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2014.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Azhar E.I., El-Kafrawy S.A., Farraj S.A. Evidence for camel-to-human transmission of MERS coronavirus. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014;370:2499–2505. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1401505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vijayanand P., Wilkins E., Woodhead M. Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS): a review. Clin. Med. 2004;4:152–160. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.4-2-152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ramadan N., Shaib H. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV): a review. Germs. 2019;9:35–42. doi: 10.18683/germs.2019.1155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu C., Zhou Q., Li Y. Research and development on therapeutic agents and vaccines for COVID-19 and related human coronavirus diseases. ACS Cent. Sci. 2020;6:315–331. doi: 10.1021/acscentsci.0c00272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ahn D.-G., Shin H.-J., Kim M.-h. Current status of epidemiology, diagnosis, therapeutics, and vaccines for novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020;30:313–324. doi: 10.4014/jmb.2003.03011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosenbaum L. Facing Covid-19 in Italy—ethics, logistics, and therapeutics on the epidemic’s front line. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:1873–1875. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2005492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sanders J.M., Monogue M.L., Jodlowski T.Z. Pharmacologic treatments for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a review. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2020;323:1824–1836. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang L., Wang Y., Ye D. A review of the 2019 Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) based on current evidence. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2020;55:105948. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xu X., Chen P., Wang J. Evolution of the novel coronavirus from the ongoing Wuhan outbreak and modeling of its spike protein for risk of human transmission. Sci. China Life Sci. 2020;63:457–460. doi: 10.1007/s11427-020-1637-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhu N., Zhang D., Wang W. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ratia K., Saikatendu K.S., Santarsiero B.D. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus papain-like protease: structure of a viral deubiquitinating enzyme. PNAS USA. 2006;103:5717–5722. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510851103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Báez-Santos Y.M., John S.E.S., Mesecar A.D. The SARS-coronavirus papain-like protease: structure, function and inhibition by designed antiviral compounds. Antivir. Res. 2015;115:21–38. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2014.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mirza M.U., Ahmad S., Abdullah I. Identification of novel human USP2 inhibitor: might involve in SARS-CoV-2 papain-like (PLpro) protease deubiquitination activity. Preprints. 2020 doi: 10.20944/preprints202005.0136.v1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ratia K., Pegan S., Takayama J. A noncovalent class of papain-like protease/deubiquitinase inhibitors blocks SARS virus replication. PNAS USA. 2008;105:16119–16124. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805240105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu C., Liu Y., Yang Y. Analysis of therapeutic targets for SARS-CoV-2 and discovery of potential drugs by computational methods. Acta Pharm. Sin. B. 2020;10:766–788. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2020.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hui D.S., I Azhar E., Madani T.A. The continuing 2019-nCoV epidemic threat of novel coronaviruses to global health—the latest 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak in Wuhan, China. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020;91:264–266. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tahir ul Qamar M., Shahid F., Ashfaq U.A. Structural modeling and conserved epitopes prediction against SARS-COV-2 structural proteins for vaccine development. Research Square. 2020 doi: 10.21203/rs.2.23973/v1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paules C.I., Marston H.D., Fauci A.S. Coronavirus infections—more than just the common cold. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2020;323:707–708. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.0757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang M., Cao R., Zhang L. Remdesivir and chloroquine effectively inhibit the recently emerged novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in vitro. Cell Res. 2020;30:269–271. doi: 10.1038/s41422-020-0282-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu W., Morse J.S., Lalonde T. Learning from the past: possible urgent prevention and treatment options for severe acute respiratory infections caused by 2019-nCoV. Chembiochem. 2020;21:730–738. doi: 10.1002/cbic.202000047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tahir ul Qamar M., Maryam A., Muneer I. Computational screening of medicinal plant phytochemicals to discover potent pan-serotype inhibitors against dengue virus. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:1–16. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-38450-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tahir Ul Qamar M., Saleem S., Ashfaq U.A. Epitope-based peptide vaccine design and target site depiction against Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus: an immune-informatics study. J. Transl. Med. 2019;17:362. doi: 10.1186/s12967-019-2116-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mirza M.U., Froeyen M. Structural elucidation of SARS-CoV-2 vital proteins: computational methods reveal potential drug candidates against Main protease, Nsp12 RNA-dependent RNA polymerase and Nsp13 helicase. J. Pharm. Anal. 2020;10:320–328. doi: 10.1016/j.jpha.2020.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mirza M.U., Ikram N. Integrated computational approach for virtual hit identification against ebola viral proteins VP35 and VP40. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016;17:1748. doi: 10.3390/ijms17111748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Muneer I., Tahir Ul Qamar M., Tusleem K. Discovery of selective inhibitors for cyclic AMP response element-binding protein: a combined ligand and structure-based resources pipeline. Anti Canc. Drugs. 2019;30:363–373. doi: 10.1097/CAD.0000000000000727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Khalid H., Landry K.B., Ijaz B. Discovery of novel Hepatitis C virus inhibitor targeting multiple allosteric sites of NS5B polymerase. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2020;84:104371. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2020.104371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saleh N.A. The QSAR and docking calculations of fullerene derivatives as HIV-1 protease inhibitors, Spectrochim. Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy. 2015;136:1523–1529. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2014.10.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mirza M.U., Vanmeert M., Ali A. Perspectives towards antiviral drug discovery against Ebola virus. J. Med. Virol. 2019;91:2029–2048. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mirza M.U., Vanmeert M., Froeyen M. In silico structural elucidation of RNA-dependent RNA polymerase towards the identification of potential Crimean-Congo Hemorrhagic Fever Virus inhibitors. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:1–18. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-43129-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Durdagi S., ul Qamar M.T., Salmas R.E. Investigating the molecular mechanism of staphylococcal DNA gyrase inhibitors: a combined ligand-based and structure-based resources pipeline. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 2018;85:122–129. doi: 10.1016/j.jmgm.2018.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tahir ul Qamar M., Ashfaq U.A., Tusleem K. In-silico identification and evaluation of plant flavonoids as dengue NS2B/NS3 protease inhibitors using molecular docking and simulation approach. Pak. J. Pharm. Sci. 2017;30:2119–2137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Du J., Cross T.A., Zhou H.-X. Recent progress in structure-based anti-influenza drug design. Drug Discov. Today. 2012;17:1111–1120. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2012.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Madrid P.B., Chopra S., Manger I.D. A systematic screen of FDA-approved drugs for inhibitors of biological threat agents. PloS One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mirza M.U., Ikram N. Integrated computational approach for virtual hit identification against ebola viral proteins VP35 and VP40. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016;17 doi: 10.3390/ijms17111748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shurtleff A.C., Nguyen T.L., Kingery D.A. Therapeutics for filovirus infection: traditional approaches and progress towards in silico drug design. Expet Opin. Drug Discov. 2012;7:935–954. doi: 10.1517/17460441.2012.714364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Leela S.L., Srisawat C., Sreekanth G.P. Drug repurposing of minocycline against dengue virus infection. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2016;478:410–416. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Luzhkov V., Decroly E., Canard B. Evaluation of adamantane derivatives as inhibitors of dengue virus mRNA cap methyltransferase by docking and molecular dynamics simulations. Mol. Inform. 2013;32:155–164. doi: 10.1002/minf.201200107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang Q.Y., Patel S.J., Vangrevelinghe E. A small-molecule dengue virus entry inhibitor. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2009;53:1823–1831. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01148-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhou Z., Khaliq M., Suk J.-E. Antiviral compounds discovered by virtual screening of Small− molecule libraries against dengue virus E protein. ACS Chem. Biol. 2008;3:765–775. doi: 10.1021/cb800176t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Parida P., Nainwal L.M., Das A. Potential of plant alkaloids as dengue ns3 protease inhibitors: molecular docking and simulation approach. Bangladesh J. Pharmacol. 2014;9:262–267. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tahir ul Qamar M., Kiran S., Ashfaq U.A. Discovery of novel dengue NS2B/NS3 protease inhibitors using pharmacophore modeling and molecular docking based virtual screening of the zinc database. Int. J. Pharmacol. 2016;12:621–632. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nitsche C. Springer; 2018. Strategies towards Protease Inhibitors for Emerging Flaviviruses, Dengue and Zika: Control and Antiviral Treatment Strategies; pp. 175–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pattnaik A., Palermo N., Sahoo B.R. Discovery of a non-nucleoside RNA polymerase inhibitor for blocking Zika virus replication through in silico screening. Antivir. Res. 2018;151:78–86. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2017.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ramajayam R., Tan K.-P., Liu H.-G. Synthesis, docking studies, and evaluation of pyrimidines as inhibitors of SARS-CoV 3CL protease. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010;20:3569–3572. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.04.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang L., Bao B.-B., Song G.-Q. Discovery of unsymmetrical aromatic disulfides as novel inhibitors of SARS-CoV main protease: chemical synthesis, biological evaluation, molecular docking and 3D-QSAR study. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2017;137:450–461. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2017.05.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tahir ul Qamar M., Alqahtani S.M., Alamri M.A. Structural basis of SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro and anti-COVID-19 drug discovery from medicinal plants. J. Pharm. Anal. 2020;10:313–319. doi: 10.1016/j.jpha.2020.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hou T., Yu R. Molecular dynamics and free energy studies on the wild-type and double mutant HIV-1 protease complexed with amprenavir and two amprenavir-related inhibitors: mechanism for binding and drug resistance. J. Med. Chem. 2007;50:1177–1188. doi: 10.1021/jm0609162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tu J., Li J.J., Shan Z.J. Exploring the binding mechanism of Heteroaryldihydropyrimidines and Hepatitis B Virus capsid combined 3D-QSAR and molecular dynamics. Antivir. Res. 2017;137:151–164. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2016.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Anusuya S., Gromiha M.M. Quercetin derivatives as non-nucleoside inhibitors for dengue polymerase: molecular docking, molecular dynamics simulation, and binding free energy calculation. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2017;35:2895–2909. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2016.1234416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Guan S., Wang T., Kuai Z. Exploration of binding and inhibition mechanism of a small molecule inhibitor of influenza virus H1N1 hemagglutinin by molecular dynamics simulation. Sci. Rep. 2017;7 doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-03719-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bhakat S., Martin A.J., Soliman M.E. An integrated molecular dynamics, principal component analysis and residue interaction network approach reveals the impact of M184V mutation on HIV reverse transcriptase resistance to lamivudine. Mol. Biosyst. 2014;10:2215–2228. doi: 10.1039/c4mb00253a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Speelman B., Brooks B.R., Post C.B. Molecular dynamics simulations of human rhinovirus and an antiviral compound. Biophys. J. 2001;80:121–129. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)75999-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mottin M., Braga R.C., da Silva R.A. Molecular dynamics simulations of Zika virus NS3 helicase: insights into RNA binding site activity. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2017;492:643–651. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.03.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhang C., Feng T., Cheng J. Structure of the NS5 methyltransferase from Zika virus and implications in inhibitor design. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2017;492:624–630. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.11.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pan D., Niu Y., Xue W. Computational study on the drug resistance mechanism of hepatitis C virus NS5B RNA-dependent RNA polymerase mutants to BMS-791325 by molecular dynamics simulation and binding free energy calculations. Chemometr. Intell. Lab. Syst. 2016;154:185–193. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Leonis G., Steinbrecher T., Papadopoulos M.G. A contribution to the drug resistance mechanism of Darunavir, Amprenavir, Indinavir, and Saquinavir complexes with HIV-1 protease due to flap mutation I50V: a systematic MM–PBSA and thermodynamic integration study. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2013;53:2141–2153. doi: 10.1021/ci4002102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pan P., Li L., Li Y. Insights into susceptibility of antiviral drugs against the E119G mutant of 2009 influenza A (H1N1) neuraminidase by molecular dynamics simulations and free energy calculations. Antivir. Res. 2013;100:356–364. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2013.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.McInnes C. Virtual screening strategies in drug discovery. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2007;11:494–502. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2007.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Berman H.M., Bourne P.E., Westbrook J. CRC Press; 2003. The Protein Data Bank, Protein Structure; pp. 394–410. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sievers F., Wilm A., Dineen D. Fast, scalable generation of high-quality protein multiple sequence alignments using Clustal Omega. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2011;7 doi: 10.1038/msb.2011.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.DeLano W.L. Pymol: an open-source molecular graphics tool. CCP4 Newslett. Protein Crystallogr. 2002;40:82–92. [Google Scholar]

- 69.O’Boyle N.M., Banck M., James C.A. Open Babel: an open chemical toolbox. J. Cheminf. 2011;3:33. doi: 10.1186/1758-2946-3-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Forli S., Huey R., Pique M.E. Computational protein–ligand docking and virtual drug screening with the AutoDock suite. Nat. Protoc. 2016;11:905–919. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2016.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Systèmes D. Dassault Systèmes Biovia; San Diego, CA, USA: 2016. BIOVIA, Discovery Studio Modeling Environment. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dallakyan S., Olson A.J. Small-Molecule Library Screening by Docking with PyRx. In: Hempel J., Williams C., Hong C., editors. Vol. 1263. Humana Press; New York: 2015. (Chemical Biology, Methods in Molecular Biology). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wang Q., He J., Wu D. Interaction of α-cyperone with human serum albumin: determination of the binding site by using Discovery Studio and via spectroscopic methods. J. Lumin. 2015;164:81–85. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Daina A., Michielin O., Zoete V. SwissADME: a free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:42717. doi: 10.1038/srep42717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gimenez B., Santos M., Ferrarini M. Evaluation of blockbuster drugs under the rule-of-five. Pharmazie-Int. J. Pharm. Sci. 2010;65:148–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Pires D.E.V., Blundell T.L., Ascher D.B. pkCSM: predicting small-molecule pharmacokinetic and toxicity properties using graph-based signatures. J. Med. Chem. 2015;58:4066–4072. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hess B., Kutzner C., Van Der Spoel D. Gromacs 4: algorithms for highly efficient, load-balanced, and scalable molecular simulation. J. Chem. Theor. Comput. 2008;4:435–447. doi: 10.1021/ct700301q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Alamri M.A. Pharmacoinformatics and molecular dynamic simulation studies to identify potential small-molecule inhibitors of WNK-SPAK/OSR1 signaling that mimic the RFQV motifs of WNK kinases. Arabian J. Chem. 2020;13:5107–5117. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Meng E.C., Pettersen E.F., Couch G.S. Tools for integrated sequence-structure analysis with UCSF Chimera. BMC Bioinf. 2006;7:339. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Miller B.R., Iii, McGee T.D., Jr., Swails J.M. MMPBSA. py: an efficient program for end-state free energy calculations. J. Chem. Theor. Comput. 2012;8:3314–3321. doi: 10.1021/ct300418h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ikram N., Mirza M.U., Vanmeert M. Inhibition of oncogenic kinases: an in vitro validated computational approach identified potential multi-target anticancer compounds. Biomolecules. 2019;9:124. doi: 10.3390/biom9040124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Iman K., Mirza M.U., Mazhar N. In silico structure-based identification of novel acetylcholinesterase inhibitors against alzheimer’s disease. CNS Neurol. Disord. Drug Targets. 2018;17:54–68. doi: 10.2174/1871527317666180115162422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hou T., Wang J., Li Y. Assessing the performance of the MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA methods. 1. The accuracy of binding free energy calculations based on molecular dynamics simulations. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2011;51:69–82. doi: 10.1021/ci100275a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Srivastava H.K., Sastry G.N. Molecular dynamics investigation on a series of HIV protease inhibitors: assessing the performance of MM-PBSA and MM-GBSA approaches. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2012;52:3088–3098. doi: 10.1021/ci300385h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Tan J.J., Zu Chen W., Wang C.X. Investigating interactions between HIV-1 gp41 and inhibitors by molecular dynamics simulation and MM–PBSA/GBSA calculations. J. Mol. Struct.: THEOCHEM. 2006;766:77–82. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Chan J.F., Chan K.-H., Kao R.Y. Broad-spectrum antivirals for the emerging Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. J. Infect. 2013;67:606–616. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2013.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ghosh A.K., Takayama J., Rao K.V. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus papain-like novel protease inhibitors: design, synthesis, protein− ligand X-ray structure and biological evaluation. J. Med. Chem. 2010;53:4968–4979. doi: 10.1021/jm1004489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Tahir ul Qamar M., Shokat Z., Muneer I. Multiepitope-based subunit vaccine design and evaluation against respiratory syncytial virus using reverse vaccinology approach. Vaccines. 2020;8 doi: 10.3390/vaccines8020288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Alamri M.A., Tahir ul Qamar M., Mirza M.U. Pharmacoinformatics and molecular dynamics simulation studies reveal potential covalent and FDA-approved inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 main protease 3CLpro. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2020:1–13. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2020.1782768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.El Hage K., Mondal P., Meuwly M. Free energy simulations for protein ligand binding and stability. Mol. Simulat. 2018;44:1044–1061. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Liu K., Kokubo H. Exploring the stability of ligand binding modes to proteins by molecular dynamics simulations: a cross-docking study. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2017;57:2514–2522. doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.7b00412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Liu K., Watanabe E., Kokubo H. Exploring the stability of ligand binding modes to proteins by molecular dynamics simulations. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 2017;31:201–211. doi: 10.1007/s10822-016-0005-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wieder M., Perricone U., Boresch S. Evaluating the stability of pharmacophore features using molecular dynamics simulations. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2016;470:685–689. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.01.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.McGillewie L., Soliman M.E. The binding landscape of plasmepsin V and the implications for flap dynamics. Mol. Biosyst. 2016;12:1457–1467. doi: 10.1039/c6mb00077k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Sindhu T., Srinivasan P. Exploring the binding properties of agonists interacting with human TGR5 using structural modeling, molecular docking and dynamics simulations. RSC Adv. 2015;5:14202–14213. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Richmond T.J. Solvent accessible surface area and excluded volume in proteins: analytical equations for overlapping spheres and implications for the hydrophobic effect. J. Mol. Biol. 1984;178:63–89. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(84)90231-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Chen F., Liu H., Sun H. Assessing the performance of the MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA methods. 6. Capability to predict protein–protein binding free energies and re-rank binding poses generated by protein–protein docking. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2016;18:22129–22139. doi: 10.1039/c6cp03670h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Sirin S., Kumar R., Martinez C. A computational approach to enzyme design: predicting ω-aminotransferase catalytic activity using docking and MM-GBSA scoring. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2014;54:2334–2346. doi: 10.1021/ci5002185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Hou T., Wang J., Li Y. Assessing the performance of the MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA methods. 1. The accuracy of binding free energy calculations based on molecular dynamics simulations. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2011;51:69–82. doi: 10.1021/ci100275a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Sun H., Duan L., Chen F. Assessing the performance of MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA methods. 7. Entropy effects on the performance of end-point binding free energy calculation approaches. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2018;20:14450–14460. doi: 10.1039/c7cp07623a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Lin M.-H., Moses D.C., Hsieh C.-H. Disulfiram can inhibit mers and sars coronavirus papain-like proteases via different modes. Antivir. Res. 2018;150:155–163. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2017.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Li G., De Clercq E. Therapeutic options for the 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2020;19:149–150. doi: 10.1038/d41573-020-00016-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Bobrowski T., Alves V., Melo-Filho C.C. Computational models identify several FDA approved or experimental drugs as putative agents against SARS-CoV-2. ChemRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.26434/chemrxiv.12153594.v1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Hu F., Jiang J., Yin P. arXiv preprint; 2020. Prediction of Potential Commercially Inhibitors against SARS-CoV-2 by Multi-Task Deep Model.https://arxiv.org/abs/2003.00728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Chan J.F., Chan K.-H., Kao R.Y. Broad-spectrum antivirals for the emerging Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. J. Infect. 2013;67:606–616. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2013.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Chan J.F.-W., Yao Y., Yeung M.-L. Treatment with lopinavir/ritonavir or interferon-β1b improves outcome of MERS-CoV infection in a nonhuman primate model of common marmoset. J. Infect. Dis. 2015;212:1904–1913. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Arabi Y.M., Alothman A., Balkhy H.H. Treatment of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome with a combination of lopinavir-ritonavir and interferon-β1b (MIRACLE trial): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2018;19:81. doi: 10.1186/s13063-017-2427-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Sheahan T.P., Sims A.C., Leist S.R. Comparative therapeutic efficacy of remdesivir and combination lopinavir, ritonavir, and interferon beta against MERS-CoV. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:1–14. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-13940-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Chu C., Cheng V., Hung I. Role of lopinavir/ritonavir in the treatment of SARS: initial virological and clinical findings. Thorax. 2004;59:252–256. doi: 10.1136/thorax.2003.012658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Nukoolkarn V., Lee V.S., Malaisree M. Molecular dynamic simulations analysis of ritronavir and lopinavir as SARS-CoV 3CLpro inhibitors. J. Theor. Biol. 2008;254:861–867. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2008.07.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Stockman L.J., Bellamy R., Garner P. SARS: systematic review of treatment effects. PLoS Med. 2006;3 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Yao T.T., Qian J.D., Zhu W.Y. A systematic review of lopinavir therapy for SARS coronavirus and MERS coronavirus–A possible reference for coronavirus disease-19 treatment option. J. Med. Virol. 2020;92:556–563. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Hung I.F.-N., Lung K.-C., Tso E.Y.-K. Triple combination of interferon beta-1b, lopinavir–ritonavir, and ribavirin in the treatment of patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19: an open-label, randomised, phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2020;395:1695–1704. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31042-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Moro S., Bolcato G., Bissaro M. Targeting the Coronavirus SARS-CoV-2: computational insights into the mechanism of action of the protease inhibitors Lopinavir, Ritonavir, and Nelfinavir. Research Square. 2020 doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-20948/v1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Hurst M., Faulds D. Lopinavir, Drugs. 2000;60:1371–1379. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200060060-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Lee H., Lei H., Santarsiero B.D. Inhibitor recognition specificity of MERS-CoV papain-like protease may differ from that of SARS-CoV. ACS Chem. Biol. 2015;10:1456–1465. doi: 10.1021/cb500917m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Cregar-Hernandez L., Jiao G.-S., Johnson A.T. Small molecule pan-dengue and West Nile virus NS3 protease inhibitors. Antiviral Chem. Chemother. 2011;21:209–217. doi: 10.3851/IMP1767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Lin B., He S., Yim H.J. Evaluation of antiviral drug synergy in an infectious HCV system. Antivir. Ther. 2016;21:595–603. doi: 10.3851/IMP3044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.DeGoey D.A., Randolph J.T., Liu D. Discovery of ABT-267, a pan-genotypic inhibitor of HCV NS5A. J. Med. Chem. 2014;57:2047–2057. doi: 10.1021/jm401398x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Lam A.M., Murakami E., Espiritu C. PSI-7851, a pronucleotide of β-D-2′-deoxy-2′-fluoro-2′-C-methyluridine monophosphate, is a potent and pan-genotype inhibitor of hepatitis C virus replication. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2010;54:3187–3196. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00399-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Belema M., Meanwell N.A. Discovery of daclatasvir, a pan-genotypic hepatitis C virus NS5A replication complex inhibitor with potent clinical effect. J. Med. Chem. 2014;57:5057–5071. doi: 10.1021/jm500335h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Nakata H., Steinberg S.M., Koh Y. Potent synergistic anti-human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) effects using combinations of the CCR5 inhibitor aplaviroc with other anti-HIV drugs. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2008;52:2111–2119. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01299-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.