Abstract

By combining metal nodes with organic linkers we can potentially synthesize millions of possible metal–organic frameworks (MOFs). The fact that we have so many materials opens many exciting avenues but also create new challenges. We simply have too many materials to be processed using conventional, brute force, methods. In this review, we show that having so many materials allows us to use big-data methods as a powerful technique to study these materials and to discover complex correlations. The first part of the review gives an introduction to the principles of big-data science. We show how to select appropriate training sets, survey approaches that are used to represent these materials in feature space, and review different learning architectures, as well as evaluation and interpretation strategies. In the second part, we review how the different approaches of machine learning have been applied to porous materials. In particular, we discuss applications in the field of gas storage and separation, the stability of these materials, their electronic properties, and their synthesis. Given the increasing interest of the scientific community in machine learning, we expect this list to rapidly expand in the coming years.

1. Introduction

One of the fascinating aspects of metal–organic frameworks (MOFs) is that by combining linkers and metal nodes we can synthesize millions of different materials.1 Over the past decade, over 10,000 porous2,3 and 80,000 nonporous MOFs have been synthesized.4 In addition, one also has covalent organic frameworks (COFs), porous polymer networks (PPNs), zeolites, and related porous materials. Because of their potential in many applications, ranging from gas separation and storage, sensing, catalysis, etc., these materials have attracted a lot of attention. From a scientific point of view, these materials are interesting as their chemical tunability allows us to tailor-make materials with exactly the right properties. As one can only synthesize a tiny fraction of all possible materials, these experimental efforts are often combined with computational approaches, often referred to as materials genomics,5 to generate libraries of predicted or hypothetical MOFs, COFs, and other related porous materials. These libraries are subsequently computationally screened to identify the most promising material for a given application.

That we now have of the order of ten thousand synthesized porous crystals and over a hundred thousand predicted materials does create new challenges; we simply have too many structures and too much data. Issues related to having so many structures can be simple questions on how to manage so much data but also more profound on how to use the data to discover new science. Therefore, a logical next step in materials genomics is to apply the tools of big-data science and to exploit “the unreasonable effectiveness of data”.6 In this review, we discuss how machine learning (ML) has been applied to porous materials and review some aspects of the underlying techniques in each step. Before discussing the specific applications of ML to porous materials, we give an overview over the ML landscape to introduce some terminologies and also give a short overview over the technical terms we will use throughout this review in Table 1.

Table 1. Common Technical Terms Used in ML and Their Meanings.

| technical term | explanation |

|---|---|

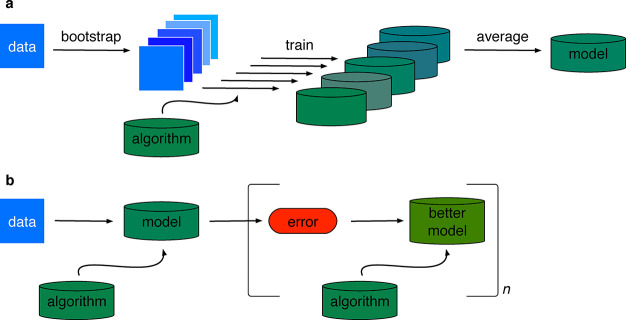

| bagging | acronym for bootstrap aggregating, ensemble technique in which models are fitted on bootstrapped samples from the data and then averaged |

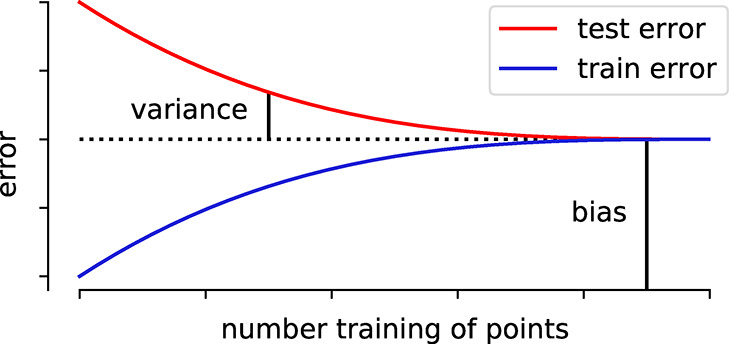

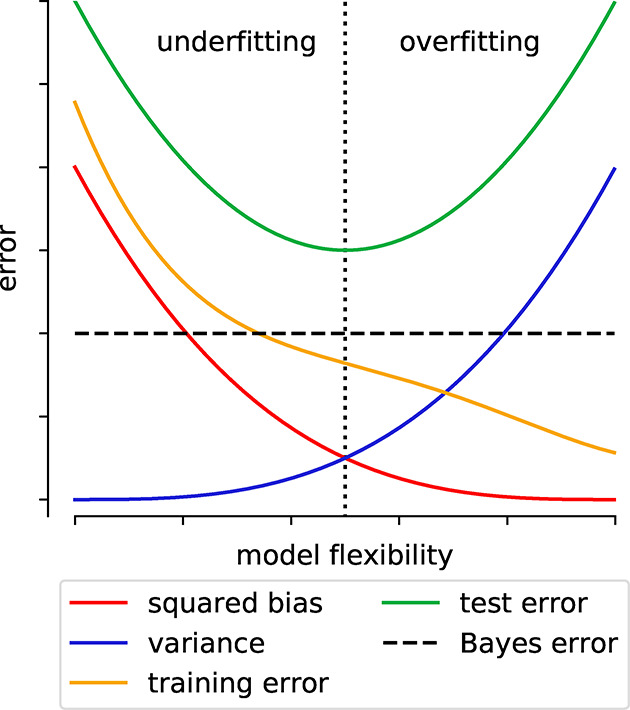

| bias | error that remains for infinite number of training examples, e.g., due to limited expressivity |

| boosting | ensemble technique in which weak learners are iteratively combined to build a stronger learner |

| bootstrapping | calculate statistics by randomly drawing samples with replacement |

| classification | process of assigning examples to a particular class |

| confidence interval | interval of confidence around predicted mean response |

| feature | vector with numeric encoding of a description of a material that the ML uses for learning |

| fidelity | measure of how close a model represents the real case |

| fitting | estimating parameters of some models with high accuracy |

| gradient descent | optimization by following the gradient, stochastic gradient descent approximates the gradient using a mini-batch of the available data |

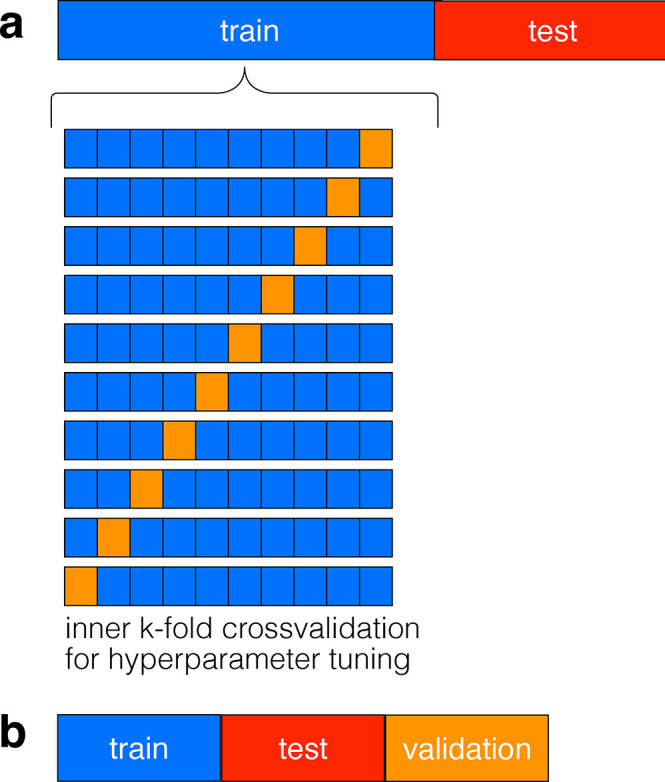

| hyperparameters | tuning parameters of the learner (like learning rate, regularization strength) which, in contrast to model parameters, are not learned during training and have to be specified before training |

| instance based learning | learning by heart, query data are compared to training examples to make a prediction |

| irreducible error | error that cannot be reduced (e.g., due to noise in the data), i.e., that is also there for a perfect model. Also known as Bayes error rate |

| label (target) | the property one wants to predict |

| objective function (cost function) | the function that a ML algorithm tries to minimize |

| one-hot encoding | method to represent categorical variables by creating a feature column for each category and using value of one to encode the presence and zero to encode the absence |

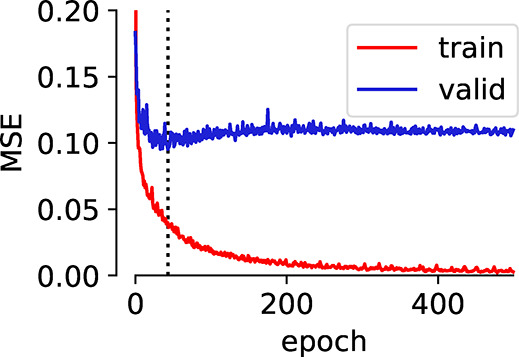

| overfitting | the gap between training and test error is large, i.e., the model solely “remembers” the training data but fails to predict on unseen examples |

| predicting | making predictions for future samples with high accuracy |

| prediction interval | interval of confidence around predicted sample response, always wider than confidence interval |

| regression | process of estimating the continuous relationship between a dependent variable and one or more independent variables |

| regularization | describes techniques that add terms or information to the model to avoid overfitting |

| stratification | data is divided in homogeneous subgroups (strata) such that sampling will not disturb the class distributions |

| structured data | data that is organized in tables with rows and columns, i.e., data that resides in relational databases |

| test set | collection of labels and feature vectors that is used for model evaluation and which must not overlap with the training set |

| training set | collection of labels and feature vectors that is used for training |

| transfer | use knowledge gained on one distribution to perform inference on another distribution |

| unstructured data | e.g., image, video, audio, text. i.e., data that is not organized in a tabular form |

| validation set | also known as development set, collection of labels and feature vectors that is used for hyperparameter tuning and which must not overlap with the test and training sets |

| variance | part of the error that is due to finite-size effects (e.g., fluctuations due to random split in training and test set) |

In this review, we focus on applications of ML in materials science and chemistry with a particular focus on porous materials. For a more general discussion on ML, we refer the reader to some excellent reviews.7,8

2. Machine Learning Landscape

Nowadays it is difficult, if not impossible, to avoid ML in science. Because of recent developments in technology, we now routinely store and analyze large amounts of data. The underlying idea of big-data science is that if one has large amounts of data, one might be able to discover statistically significant patterns that are correlated to some specific properties or events. Arthur Samuel was among the first to use the term “machine learning” for the algorithms he developed in 1959 to teach a computer to play the game of checkers.9 His ML algorithm let the computer look ahead a few moves. Initially, each possible move had the same weight and hence probability of being executed. By collecting more and more data from actual games, the computer could learn which move for a given board configuration would develop a winning strategy. One of the reasons why Arthur Samuel looked at checkers was that in the practical sense the game of checkers is not deterministic; there is no known algorithm that leads to winning the game and the complete evaluation of all 1040 possible moves is beyond the capacity of any computer.

There are some similarities between the game checkers and the science of discovering new materials. Making a new material is in practice equally nondeterministic. The number of possible ways we can combine atoms is simply too large to evaluate all possible materials. For a long time, materials discovery has been based on empirical knowledge. Significant advances were made, once some of this empirical knowledge was generalized in the form of theoretical frameworks. Combined with supercomputers these theoretical frameworks resulted in accurate predictions of the properties of materials. Yet, the number of atoms and possible materials is simply too large to predict all properties of all possible materials. Hence, there will be large parts of our material space that are, in practical terms, out of reach of the conventional paradigms of science. Some phenomena are simply too complex to be explicitly described with theory. Teaching the computer the concepts using big data might be an interesting route to study some of these problems. The emergence of off-the-shelf machine learning methods that can be used by domain experts10—not only specialized data scientists—in combination with big data is thought to spark the “fourth industrial revolution” and the “fourth paradigm of science” (cf. Figure 1).11,12 In this context, big data can add a new dimension to material discovery. One needs to realize that even though ML might appear as “black box” engineering in some instances, good predictions from a black box are indefinitely better than no prediction at all. This is to some extent similar to an engineer that can make things work without understanding all the underlying physics. And, as we will discuss below, there are many techniques to investigate the reliability and domain of applicability of a ML model as well as techniques that can help in understanding the predictions made by the model.

Material science and chemistry may not be the most obvious topics for big-data science. Experiments are labor-intensive and the amount of data about materials that have been collected in the last centuries is minute compared to what Google and the likes collect every single second. However, recently the field of materials genomics has changed the landscape.13 High-throughput density-functional theory (DFT) calculations14 and molecular simulations15 have become routine tools to study the properties of real and even hypothetical materials. In these studies, ML is becoming more popular and widely used as a filter in the computational funnel of high-throughput screenings16 but also to assist and guide simulations17−20 or experiments,21 or to even replace them,22,23 and to design new high-performing materials.24

Another important factor is the prominent role patterns played in chemistry. The most famous example is Mendeleev’s periodic table, but also Pauling’s rules,25 Pettifor’s maps,26 and many other structure–property relationships were guided by a combination of empirical knowledge and chemical intuition. What we hope to show in this review is that ML holds the promise to discover much more complex relationships from (big) data.

We continue this section with a broad overview of the main principles of ML. This section will be followed with a more detailed and technical discussion on the different subtopics introduced in this section.

2.1. Machine Learning Pipeline

2.1.1. Machine Learning Workflow

ML is no different from any other method in science. There are questions for which ML is an extremely powerful method to find an answer, but if one sees ML as the modern solution to any ill-posed problem, one is bound to be disappointed. In section 9, we will discuss the type of questions that have been successfully addressed using ML in the contexts of synthesis and applications of porous materials.

Independent of the learning algorithm or goal, the ML workflow from materials’ data to prediction and interpretation can be divided into the following blueprint of a workflow, which also this review follows:

-

1.

Understanding the problem: An understanding of the phenomena that need to be described is important. For example, if we are interested in methane storage in porous media, the key performance parameter is the deliverable capacity, which can be obtained directly for the experimental adsorption isotherms at a given temperature. In more general terms, an understanding of the phenomena helps us to guide the generation and transformation of the data (discussed in more detail in the next step).

In the case of the deliverable capacity we have a continuous variable and hence a regression problem, which can be more difficult to learn compared to classification problems (e.g., whether the channels in our porous material form a 1, 2, or 3-dimensional network or classify the deliverable capacity as “high” or “low”).

Importantly, the problem definition guides the choice of the strategies for model evaluation, selection, and interpretation (cf. section 7): In some classification cases, such as in a part of the high-throughput funnel, in which we are interested in finding the top-performing materials by down selecting materials, missing the highest-performing material is worse than doing an additional simulation for a mediocre material—this is something one should realize before building the model.

-

2.

Generating and exploring data: Machine learning needs data to learn from. In particular, one needs to ensure that we have suitable training data. Suitable, in the sense that the data are reliable and provide sufficient coverage of the design space we would like to explore. Sometimes, suitable training data must be generated or augmented. The process of exploring a suitable data set (known as exploratory data analysis (EDA)27) and its subsequent featurization can help to understand the problem better and inform the modeling process.

Once we have collected a data set, the next steps involve:

-

(a)

Data selection: If the goal is to predict materials properties, which is the focus of this review, it is crucial to ensure that the available labels y, i.e., the targets we want to predict, are consistent, and special care has to be taken when data from different sources are used. We discuss this step in more detail in section 3 and the outlook.

-

(b)

Featurization is the process in which the structures or raw data are mapped into feature (or design) matrices X, where one row in this matrix characterizes one material. Domain knowledge in the context of the problem we are addressing can be particularly useful in this step, for example, to select the relevant length scales (atomistic, coarse-grained, or global) or properties (electronic, geometric, or involved experimental properties). We give an overview of this process in section 4.

-

(c)

Sampling: Often, training data are randomly selected from a large database of training points. But this is not necessarily the best choice as most likely the materials are not uniformly distributed for all possible labels we are potentially interested in. For example, one class (often the low-performing structures) might constitute the majority of the training set and the algorithm will have problems in making predictions for the minority class (which are often the most interesting cases). Special methods, e.g., farthest point sampling (FPS), have been developed to sample the design space more uniformly. In section 3.2 we discuss ways to mitigate this problem and approaches to deal with little data.

-

(a)

-

3.

Learning and Prediction: In section 5 we examine several ways in which one can learn from data, and what one should consider when choosing a particular algorithm. We then describe different methods with which one can improve predictive performance and avoid overfitting (cf. section 6).

To guide the modeling and model selection, methods for performance evaluation are needed. In section 7 we describe best practices for model evaluation and comparison.

-

4.

Interpretation: Often it is interesting to understand what and how the model learned—e.g., to better grasp structure–property relationships or to debug ML models. ML is often seen as a black-box approach to predict numerical values with zero understanding—defeating the goal of science to understand and explain phenomena. Therefore, the need for causal models is seen as a step toward machines “that learn and think like people” (learning as model building instead of mere pattern recognition).28 In section 8 we present different approaches to look into black-box models, or how to avoid them in the first place.

It is important to remember that model development is an iterative process; the understanding gained from the first model evaluations can help to understand the model better and help in refining the data, the featurization, and the model architecture. For this, interpretable models can be particularly valuable.29

The scope of this review is to provide guidance along this path and to highlight the caveats, but also to point to more detailed resources and useful Python packages that can be used to implement a specific step.

An excellent general overview that digs deeper into the mathematical background than this review is the “High-Bias, Low Variance Introduction to Machine Learning for Physicists” by Mehta et al.;7 recent applications of ML to materials science are covered by Schmidt et al.30 But also many textbooks cover the fundamentals of machine learning; e.g., Tibshirani and Friedman,31 Shalev-Shwartz and Ben-David,32 as well as Bishop (from a more Bayesian point of view)33 focus more on the theoretical background of statistical learning, whereas Géron provides a “how-to” for the actual implementation, also of neural network (NN) architectures, using popular Python frameworks,34 which were recently reviewed by Rascka et al.35

2.1.2. Machine Learning Algorithms

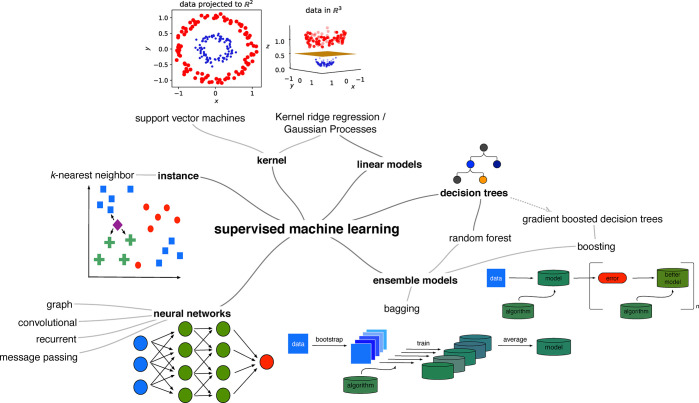

Step three of the workflow described in the previous section, learning and predictions, usually receives the most attention. Broadly, there are three classes, though with fuzzy boundaries, for this step, namely supervised, unsupervised, and reinforcement learning. We will focus only on supervised learning in this review, and only briefly describe possible applications of the other categories and highlight good starting points to help the reader orient in the field.

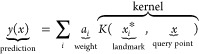

2.1.2.1. Supervised Learning: Feature Matrix and Labels Are Given

The most widely used flavor, which is also the focus of this review, is supervised learning. Here, one has access to features that describe a material and the corresponding labels (the property one wants to predict).

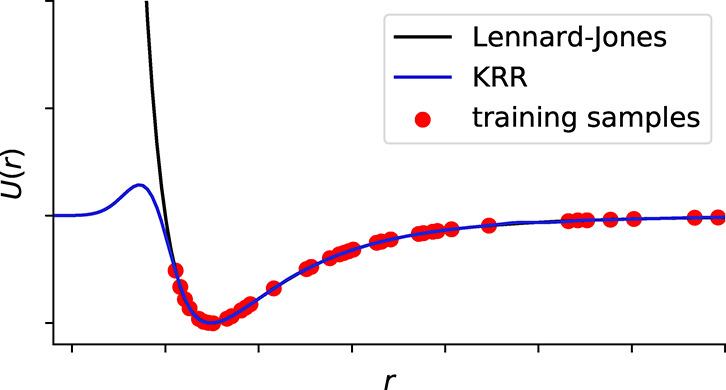

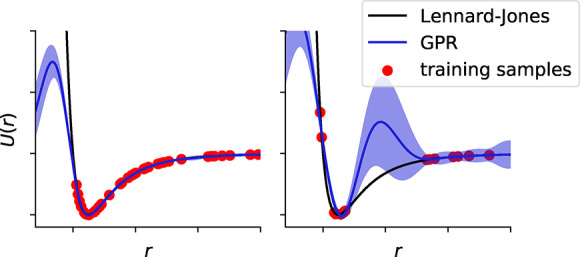

A common use case is to completely replace expensive calculations with the calculation of features that can be then fed into a model to make a prediction. A different use case can be to still perform molecular simulations—but to use ML to generate better potential energy surface (PES), e.g., using “machine learned” force fields. Another promising avenue is Δ-ML in which a model is trained to predict a correction to a coarser level of theory:36 One example would be to predict the correction to DFT energies to predict coupled-cluster energies.

Supervised learning can also be used as part of an active learning loop for self-driving laboratories and to efficiently optimize reaction conditions. In this review, we do not focus on this aspect—good starting points are reports from the groups around Alán Aspuru-Guzik37−40 and Lee Cronin.41−44

2.1.2.2. Unsupervised Learning: Using Only the Feature Matrix

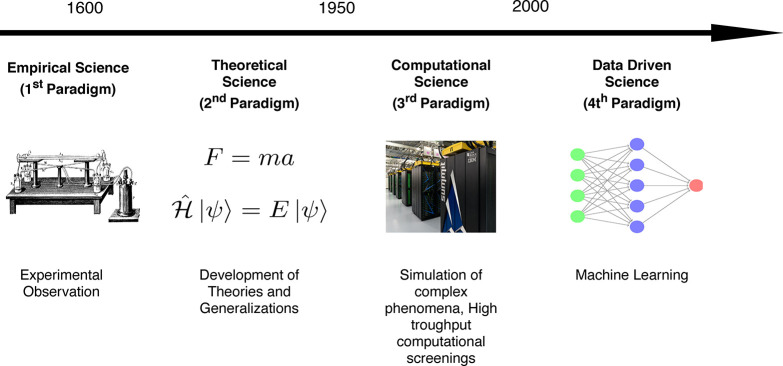

Figure 1.

Different approaches to science that evolved over time, starting from empirical observation, generalizations to theories, and simulation of different, complex, phenomena. The latest addition is the data-driven discovery (“fourth paradigm of science”). The supercomputer image was taken from the Oak Ridge National Laboratory.

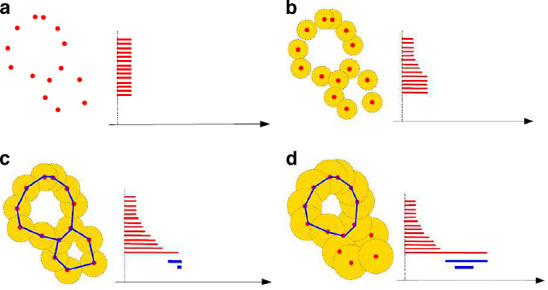

2.1.2.2.1. Dimensionality Reduction and Clustering

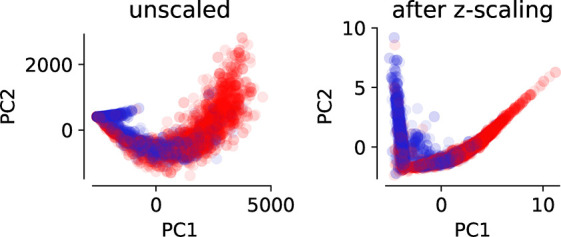

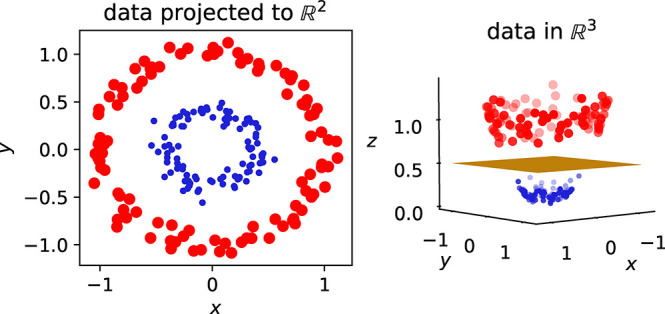

The importance of unsupervised methods becomes clear when dealing with high-dimensional data which are notoriously difficult to visualize and understand (cf. section 4.1.0.1). And in fact some of the earliest applications of these techniques were to analyze45−47 and then speed up molecular simulations.48,49 The challenge with molecular simulations is that we explore a 3N dimensional space, where N is the number of particles. For large N, as it is, for example, the case for the simulation of protein dynamics, it can be hard to identify low energy states.48 To accelerate the sampling, one can apply biasing potentials that help the simulation to move over barriers between metastable states. Typically, such potentials are constructed in terms of a small number of variables, known as collective variables—but it can be a challenge to identify what a good choice of the collective variables is when the dimensionality of the system is high. In this context, ML has been employed to lower the dimensionality of the system (cf. Figure 2 for an example of such a dimensionality reduction) and to express the collective variables in this low-dimensional space.

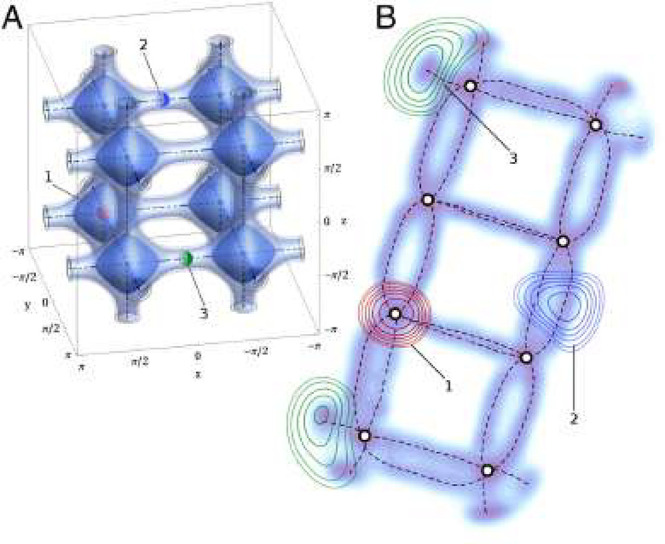

Figure 2.

(A) Three-dimensional energy landscape and (B) its two-dimensional projection using sketchmap, which is a dimensionality reduction technique. The biasing potentials can now be represented in terms of sketchmap coordinates. Figure reproduced from ref (48). Copyright 2012 National Academy of Sciences.

Dimensionality reduction techniques, like principal component analysis (PCA), ISOMAP, t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE), self-organizing maps,50,51 growing cell structures,52 or sketchmap,53,54 can be used to do so.48 But they can also be used for “materials cartography”,55 i.e., to present the high-dimensional space of material properties in two dimensions to help identify patterns in big and high-dimensional data.56 A book chapter by Samudrala et al.57 and a perspective by Ceriotti58 give an overview of applications in materials science.

Recently, unsupervised learning—in the form of word-embeddings, which are vectors in the multidimensional “vocabulary space” that are usually used for natural language processing (NLP)—has also been used to discover chemistry in form of structure–property relationships in chemical literature. This technique could also be used to make recommendations based on the distance of a word-embedding of a compound, to the vector of a concept such as thermoelectricity in the word-embedding space.59

2.1.2.2.2. Generative Models

One ultimate goal of ML is to design new materials (which recently has also been popularized as “inverse design”). Generative models, like generative adverserial networks (GANs) or variational autoencoderss (VAEs) hold the promise to do this.60 GANs and VAEs can create new molecules,61 or probability distributions,62 with the desired properties on the computer.18 One example for the success of generative techniques (in combination with reinforcement learning) is the discovery of inhibitors for a kinase target implicated in fibrosis, that were discovered in 21 days on the computer and also showed promising results in experiments.63 An excellent outline of the promises of generative models and their use for the design of new compounds is given by Sanchez24 and Elton.64

The interface between unsupervised and supervised learning is known as semisupervised learning. In this setting, only some labels are known, which is often the case when labeling is expensive. This was also the case in a recent study of the group around Ceder,65 where they attempted to classify synthesis descriptions in papers according to different categories like hydrothermal or solid-state synthesis. The initial labeling for a small subset was performed manually, but they could then use semisupervised techniques to leverage the full data sets, i.e., also the unlabeled parts.

2.1.2.3. Reinforcement Learning: Agents Maximizing Rewards

In reinforcement learning67 agents try to figure out the optimal sequence of actions (which is known as policy) in some environment to maximize a reward. An interesting application of this subfield of ML in chemistry is to find the optimal reaction conditions to maximize the yield or to create structures with desired properties (cf. Figure 3).66,68 Reinforcement learning has also been in the news for the superhuman performance achieved on some video games.69,70 Still, it tends to require a lot of training. AlphaGo Zero, for example, needed nearly 5 million matches, requiring millions of dollars of investment in hardware and computational time.71

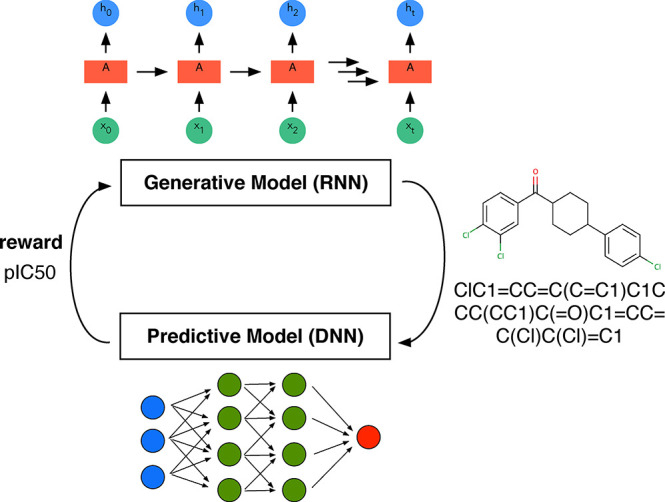

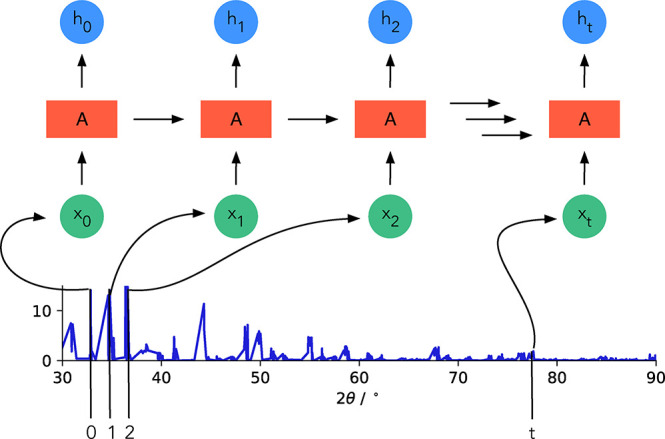

Figure 3.

Reinforcement learning scheme illustrated based on the approach chosen by Popova et al.66 for drug design. They use a recurrent neural network (RNN) (cf. section 5.1.1.5) for the generation of simplified molecular input line entry system (SMILES) strings and a deep NN for property prediction. In a first stage, both models are trained separately, and then they are used jointly to bias, using the target properties as the reward, the generation of new molecules. This example also nicely shows that the boundary between the different “flavors” of ML is fuzzy and that they are often used together.

2.2. Theory-Guided Data Science

We are at an age in which some argue that “the end of theory” is near,72 but throughout this review we will find that many successful ML models are guided by physics and physical insights.73−75 We will see that the symmetry of the systems guides the design of the descriptors and can guide the design of the models (e.g., by decomposing the problems into subproblems) or the choice of constraints. Sometimes, we will also encounter hybrid approaches where one component of the problem (often the local part, as locality is often an assumption for the ML models, cf. section 4.1.0.2) is solved using ML and that for example the electrostatic, long-range interaction, is added using well-known theory.

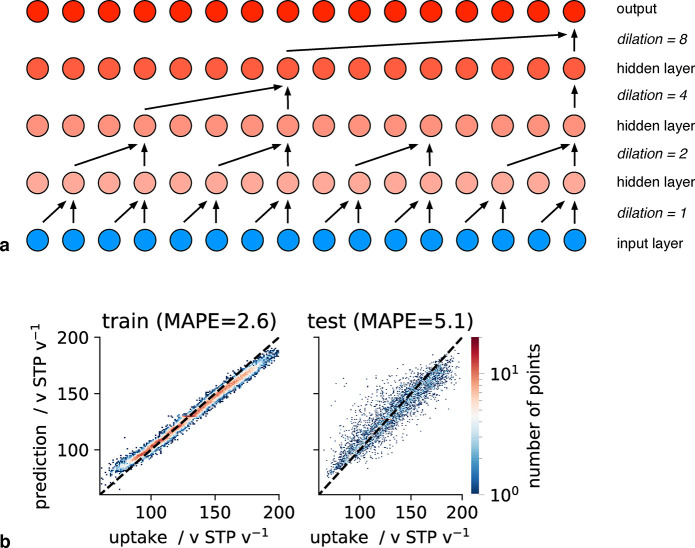

Generally, the decomposition of the problem can help to debug the model and make the model more interpretable and physical.76 For example, physics-guided breakdown of the target proved to be useful in the creation of a model for the equation of state of fluid methane.77

Physical insight can also be introduced using sparsity78 or physics-based functional forms.79 Constraints, introduced for example via Euler–Lagrange constrained minimization or coordinate scaling (stretching the coordinates should also stretch the density), have also proven to be successful in the development of ML learned density functionals.80,81

That physical insight can guide model development has been shown by Chmiele et al., who built a model of potential energy surfaces using forces instead of energies to respect energy conservation (also, the force is a quantity that is well-defined for atoms, whereas the energy is only defined for the full system).82,83

This paradigm of incorporating domain knowledge into the ML workflow is also known as theory-guided data science.84,85 Theory-guided data science can help to get the right answers for the right reasons, and we will revisit it in every chapter of this review.

2.3. Scientific Method in Machine Learning: Strong Inference and Multiple Models

Throughout this review we will encounter the method of strong inference,86,87 i.e., the need for alternative hypotheses, or more generally the integral role of critical thinking, at different places—mostly in the later stages of the ML pipeline when one analyzes a model. The idea here is to always pursue multiple alternative hypotheses that could explain the performance of a model: Is the improved performance really because of a more complex architecture or rather due to better hyperparameter optimization (cf. ablation testing in section 7.8.1) or does the model really learn sensible chemical relationships or could we achieve similar performance with random labels (cf. randomization tests as discussed in section 7.9(88,89))?

ML comes with many opportunities but also many pitfalls. In the following, we review the details of the supervised ML workflow to aid the use of ML for the progress of our field.

3. Selecting the Data: Dealing with Little, Imbalanced, and Nonrepresentative Data

The first, but most important step in ML is to generate good training data.90 This is also captured in the “garbage in garbage out” saying among ML practitioners. Data matters more than algorithms.6,91 In this section, we will mostly focus on the rows of the feature matrix, X, and discuss the columns of it, the descriptors, in the next section.

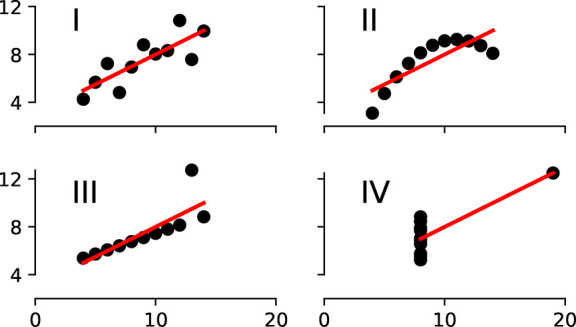

That the selection of suitable data can be far from trivial is illustrated with Anscombe’s quartet (cf. Figure 4).92 In this archetypal example four different distributions, with distinct graphs, have the same statistics, e.g., due to single high-leverage points. This example emphasizes the notion in ML that statistics can be deceiving, and why in ML so much emphasis is placed on the visualization of the data sets.

Figure 4.

Anscombe’s quartet shows the importance of visualization.92 The four data sets have the same mean (7.50), standard deviation (1.94), and regression line, but still look completely different.

3.1. Limitations of Hypothetical Databases

Hypothetical databases of COFs, MOFs, and zeolites have become popular and are frequently used as a training set for ML models—mostly because they are the largest self-consistent data sources that are available in this field. But due to the way in which the databases are constructed they can only cover a limited part of the design space (as one uses a finite, small, number of linkers and nodes)—which is also not necessarily representative of the “real world”.

The problem of idealized models and hypothetical structures is even more pronounced for materials with unconventional electronic properties. Many features that favor topological materials, which are materials with special shape of their electronic bands due to the symmetries of the atom positions, work against stability. For example, creating a topological insulator (which is insulating in the bulk, but conductive on the surface) involves moving electrons into antibonding orbitals, which weakens the lattice.93 Also, in the real world one often has to deal with defects and kinetic phenomena—real materials are often nonequilibrium structures93,94—while most databases assume ideal crystal structures.

3.2. Sampling to Improve Predictive Performance

A widespread technique in ML is to randomly split all the available data into a training and a test set. But this is not necessarily the best approach as random sampling might not sample some sparsely populated regions of the chemical space. A more reasonable sampling approach would cover as much of the chemical space as feasible to construct a maximally informed training set. This is especially important when one wants to minimize the number of training points. Limiting the number of training points can be reasonable or even essential when the featurization or labeling is expensive, e.g. when it involves experiment or ab initio calculations. But it can also be necessary for computational reasons as in the case of kernel methods (cf. section 5.2.2), for which the data needs to be kept in memory and for which the computational cost scales cubically with the number of training points.

3.2.1. Diverse Set Selection

3.2.1.1. (Greedy) Farthest Point Sampling

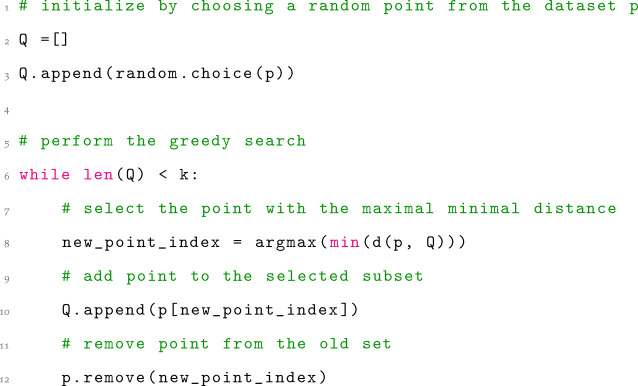

Instead of randomly selecting training points, one can try to create a maximally diverse data set to ensure a more uniform sampling of the design space and to avoid redundancy. Creating such as data set, in which the distances between the chosen data points are maximized, is known as the maximum diversity problem (MDP).95 Unfortunately, the MDP is of factorial computational cost and hence becomes computationally prohibitive for large data sets.96−98 Therefore, in practice, one usually uses a greedy algorithm to perform FPS. Those algorithms add points for which the minimum distance to the already chosen points is maximal (i.e., using the max-min criterion, this sampling approach is also known as Kennard–Stone sampling, cf. pseudocode in Chart 1).

Chart 1. Pseudocode for the Greedy Implementation of a FPS Schemea.

a The initialization could also be to choose a point that is maximally distant from the center or using the two most separated points, as in the original Kennard–Stone framework.

This FPS is also a key to the work by Moosavi et al.,21 in which they use a diverse set of initial reaction conditions, most of which will yield to failed reactions, to build their model for reaction condition prediction.

3.2.1.2. Design of Experiments

The efficient exploration is also the main goal of most design of experiment (DoE) methods,99,100 which in chemistry have been widely used for reaction condition or process optimization,101−104 where the task is to understand the relationship between input variables (temperature, reaction time, ...) and the reaction outcome in the least time and effort possible. But they also have been used in computer science to generate good initial guesses for computer codes.105,106

If our goal is to perform reaction condition prediction, the use of DoE techniques can be a good starting point to get an initial training set that covers the design space. Similarly, they can also be a good starting point if we want to build a model that correlates polymer building blocks with the properties of the polymer: since also in this case, we want to make sure that we sample all relevant combinations of building blocks efficiently. The most trivial approach in DoE is to use a full-factorial design in which the combination of all factors in all possible levels (e.g., all relevant temperatures and reaction times) is tested. But this can easily lead to a combinatorial problem. As we discussed in section 3.2.1.1, one could cover the design space using FPS. But the greedy FPS also has some properties that might not be desirable in all cases.107 For instance, it tends to preferentially select points that lie at the boundaries of design space. Also, one might prefer that the samples are equally spaced along the different dimensions.

Different classical DoE techniques can help to overcome these issues.107 In latin hypercube sampling (LHS) the range of each variable is binned in equally spaced intervals and the data is randomly sampled from each of these intervals—but in this way, some regions of space might remain unexplored. For this reason, the max-min-LHS has been developed in which evenly spread samples are selected from LHS samples using the max-min criterion.

3.2.1.3. Alternative Techniques

An alternative for the selection of a good set of training points can be the use of special matrix decompositions. CUR is a low-rank matrix decomposition into matrices of actual columns (C) and rows (R) of the original matrix, whose main advantage over other matrix decompositions, such as PCA, is that the decomposition is much more interpretable due to use of actual columns and rows of the original matrix.108 In the case of PCA, which builds linear combinations of features, one would have to analyze the loadings of the principal components to get an understanding. In contrast, the CUR algorithm selects the columns (features) and rows (structures) which have the highest influence on the low-rank fit of the matrix. And selecting structures with high statistical leverage is what we aim for in diverse set selection. Bernstein et al. found that the use of CUR to select the most relevant structures was the key for their self-guided learning of PES, in which a ML force-field is built in an automated fashion.109

Further, also D-optimal design algorithms have been put to use, in which samples are selected that maximize the ∥XTX∥ matrix, where X is the information matrix (in some references it is also called dispersion matrix) which contains the model coefficients in the columns and the different examples in the rows.110−112 Since it requires the model coefficients, it was mostly used with multivariate linear regression models in cheminformatics.

Moreover, other unsupervised learning approaches such as self-organizing maps,50k nearest neighbor (kNN),113 sphere exclusion,114 or hierarchical clustering115,116 have been used, though mostly for cheminformatics applications.117

3.2.1.4. Sampling Configurations

For fitting of models for potential energy surfaces, nonequilibrium configurations are needed. Here, it can be practical to avoid arbitrarily sampling from trajectories of molecular simulations as consecutive frames are usually highly correlated. To avoid this, normal mode sampling, where the atomic positions are displaced along randomly scaled normal modes, has been suggested to generate out-of-equilibrium chemical environments and has been successfully applied in the training of the ANI-1 potential.118 Similarly, binning procedures, where e.g. the amplitude of the force in images of a trajectory is binned, have been proposed. When generating the training data, one can then sample from all bins (like in LHS).83

Still, one needs to remember that the usage of rational sampling techniques does not necessarily improve the predictive performance on a brand-new data set which might have a different underlying distribution.119 For example, hypothetical databases of COFs contain mainly large pore structures, which are not as frequent in experimental structures. Training a model on a diverse set of hypothetical COFs will hence not guarantee that our model can predict properties of experimental structures, which might be largely nonporous.

An alternative to rationally chosen (e.g., using DoE techniques or FPS), and hence static, data sets is to let the model (actively) decide which data to use. We discuss this active learning technique next.

3.3. Active Learning

An alternative to using static training sets, which are assembled before training, is to let the machine decide which data are most effective to improve the model at its current state.120 This is known as active learning.121 And it is especially valuable in cases where the generation of training data is expensive, such as for experimental data or high-accuracy quantum chemical calculations where a simple “Edisonian” approach, in which we create a large library of reference data by brute force, might not be feasible.

Similar ideas, like adding quantum-mechanical data to a force field when needed, have already been used in molecular dynamics simulations before they became widespread among the ML practitioners in materials science and chemistry.122,123

One of the ways to determine where the current model is ambiguous, i.e., to decide when new data is useful, is to use an ensemble of models (which is also known as “query by committee”).124,125 The idea here is to train an ensemble of models, which are slightly different and hence will likely give different, wrong, answers if the model is used outside its domain of applicability (cf. section 7.6); but the answers will tend to agree mostly when the model is used within the domain of applicability.

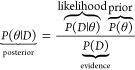

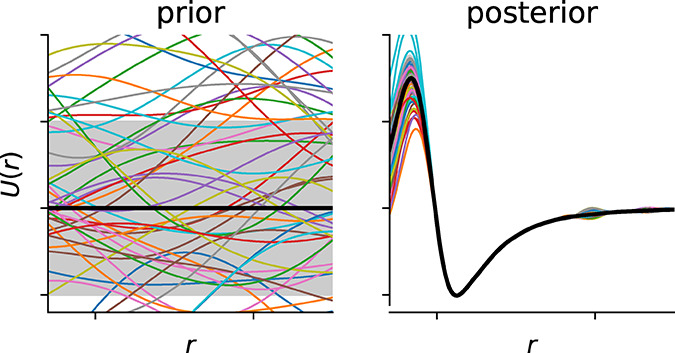

Another form of uncertainty sampling is to use a model that can directly output a probability estimate—like the width of the posterior (target) distribution of a Gaussian process (cf. section 5.2.3 for more details). One can then add training points to the space where the distribution is wide and the model is uncertain.126

Botu and Ramprasad reported a simpler strategy, which is related to the concept of the domain of applicability, which we will discuss below (cf. section 7.6). The decision if a configuration needs new training data is not made based on an uncertainty measure but merely by using the distance of the fingerprints to the already observed ones.127 Active learning is closely linked to Bayesian hyperparameter optimization (cf. section 6.1) and self-driving laboratories, as they have the goal to choose experiments in the most efficient way, where active learning tries to choose data in the most efficient way.128,129

3.4. Dealing with Little Data

Often, one can use tricks to artificially enlarge the data set to improve model performance. But these tricks generally require some domain knowledge to decide which transformations are applicable to the problem, i.e. which invariances exist. For example, if we train a force field for a porous crystal, one can use the symmetry of the crystal to generate configurations with equivalent energies (which would be a redundant operation when one uses descriptors that already respect this symmetry). For image data, like steel microstructures130 or 2D diffraction patterns,131 several techniques have been developed, which include to randomly rotate, flip, or mirror the image which is, for example, implemented in the ImageDataGenerator module of the keras Python package. Notably, there is also effort to automate the augmentation process, and promising results have been reported for images.132 However, data augmentation always relies on assumptions about the equivariances and invariances of the data, wherefore it is difficult to develop general rules for any type of data set.

Still, the addition of Gaussian noise is a method that can be applied on most data sets.133 This works effectively as data augmentation if the data is presented multiple times to the model (e.g., in NNs where one has multiple forward and backward passes of the data through the network). By the addition of random noise, the model will then see a slightly different example upon each pass of the data. The addition of noise also acts as “smoother”, which we will explore in more detail when we discuss regularization in section 6.2.1.

Oviedo et al. reported the impact data augmentation can have in materials science. Thin-film X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns are often distorted and shifted due to strain or lattice contraction or expansion. Also, the orientations of the grains are not randomized, as they are in a powder, and some reflexes will have an increased intensity depending on the orientation of the film. For this reason, conventional simulations cannot be used to form a training set for a ML model to predict the space group based on the diffraction pattern. To combat the data scarcity problem, the authors expanded the training set, generated by simulating diffraction patterns from a crystal structure database, by taking data from the training set and by scaling, deleting, or shifting of reflexes in the patterns. In this way, the authors generated new training data that correspond to the typically experimental distortions.134 A similar approach was also chosen by Wang et al., who built a convolutional neural network (CNN) to identify MOFs based on their X-ray powder diffraction (XRPD) patterns. Wang et al. predicted the patterns for MOFs in the Cambridge Structure Database (CSD) and then augmented their data set by creating new patterns by merging the main peaks of the predicted patterns with (shuffled) noise from pattern they measured in their own lab.135

Sometimes, data augmentation techniques have also been used to address nonuniqueness or invariance problems. The Chemception model is a CNN, inspired by models for image recognition, that is trained to predict chemical properties based on images of molecular drawings.136 The prediction should, of course, not depend on the relative orientation of the molecule in the drawing. For this reason, the authors introduced augmentation methods such as rotation. Interestingly, many image augmentation techniques also use cropping. However, the local information density in drawings of molecules is higher than in usual images and hence losing a part of the image would be a more significant problem.

Another issue is that not all data sets are unique. For example, if one uses (noncanonical) SMILES strings to describe molecules, one has to realize that they are not unique. Therefore, Bjerrum trained this model on all possible SMILES strings for a molecule and obtained a data set that was 130 times bigger than the original data set.137 This idea was also used for the Coulomb matrix, a popular descriptor that encodes the structure by capturing all pairwise Coulomb terms, based on the nuclear charges, in a matrix (cf. section 4.2.2.3). Without additional steps, this representation is not permutation invariant (swapping rows or columns does not change the molecule but would change the representation). Montavon used an augmented data set in which they mapped each molecule to a set of randomly sorted Coulomb matrices and could improve upon other techniques of enforcing permutation symmetry—likely due to the increased data set size.138

But also simple physical heuristics can help if there is only little data to learn from. Rhone et al. used ML to predict the outcome of reactions in heterogeneous catalysis, where only little curated data is available.139 Hence, they aided their model with a reaction tree and chose the prediction of the model that is closest to a point in the reaction tree (and hence a chemically meaningful reaction). Moreover, they also added heuristics like conservation rules and penalties for some transformations (e.g., based on the difference of heavy atoms in educts and products) to support the model.

Another promising avenue is multitask learning approaches where a model, like a deep neural networks (DNN), is trained to predict several properties. The intuition here is to capture the implicit information in the relationship between the multimodal variables.140,141 Closely related to this are transfer learning approaches (cf. section 10.3), which train a model on a large data set and then “refine” the weights of the model using a smaller data set.142 Again, this approach is a well-established practice in the “mainstream” ML community.

Given the importance of the data scarcity problem, there is a lot of ongoing effort in developing alternative solutions to combat this challenge, many of which build on encoding–decoding architectures. Generative models like GANs or VAE can be used to create new examples by learning how to generate an underlying distribution of the data.143

Some problems may also be suitable for so-called one-shot learning approaches.76,144,145 In the field of image recognition, the problem of correctly classifying an image after seeing only one training example for this class (e.g., correctly assigning names to images of persons after having seen only one image for each person) has received a lot of interest, supposedly because this is what humans are able to do—but machines are not, at least not in the “usual” classification setting.28

One- or few-shot learning is based on learning a so-called attention mechanism.146 Upon inference, the attention mechanism, which is distance measured to the memory, can be exploited to compare the new example to all training points and express the prediction as a linear combination of all labels in the support set.147 One approach to do this is Siamese learning, using an NN that takes two inputs and then learns an attention mechanism. This has also been used, in a refined formulation, by Pande and co-workers to classify the activity of small molecules on different assays for pharmaceutical activity.148 Such techniques are especially appealing for problems where only little data is available.

Still, one always should remember that there is no absolute number that defines what “little data” is. This number depends on the problem, the model, and the featurization. But it can be estimated using learning curves, in which one plots the error of the model against the number of training points (cf. section 7).

3.5. Dealing with Imbalanced Data Labels

Often, data is imbalanced, meaning that different classes which we attempt to predict (e.g., “stable” and “unstable” or “low performing” and “high performing”) do not have the same number of examples in our training set. Balachandran et al. faced this challenge when they tried to predict compounds that break spatial inversion symmetry and hence could be interesting for e.g. their piezoelectric properties.149 They found that one symmetry group was misclassified to 100% due to imbalanced data. To remedy this problem, they used an oversampling technique, which we will briefly discuss next.

Oversampling, which means adding points to the underrepresented class, is one of the most widely used approaches to deal with imbalanced data. The opposite approach is undersampling, in which instances of the majority class are removed. Since random oversampling can cause overfitting (due to replication of training points) and undersampling can lead to poorer predictive performance (as training points are eliminated), both strategies have been refined by means of interpolative procedures.150

The synthetic minority oversampling technique (SMOTE) for example, creates new (synthetic) data for the minority class by randomly selecting a point on the vector connecting a data point from the minority class with one of its nearest neighbors. In SMOTE, each point in the minority class is treated equally—which might not be ideal since one would expect that examples close to class boundaries are more likely to be misclassified. Borderline-SMOTE and (ADASYN) try to improve on this point. In a similar vein, it can also be easier to learn clear classification rules when so-called Tomek links151 are deleted. Tomek links are pairs of two points from different classes for which the distance to the example from the alternative class is smaller than to any other example from their class.

Still, care needs to be taken in the case of very imbalanced data in which algorithms can have difficulties to recognize class structures. In this case over- or undersampling can even deteriorate the performance.152

A useful Python package to address data imbalance problems is imbalanced-learn, which implements all the methods we mentioned and which are analyzed in more detail in a review by He and Garcia.150 There they also discuss cost-sensitive techniques. In these approaches, a cost matrix is used to describe a higher penalty for misclassifying examples from a certain class—which can be an alternative strategy to deal with imbalanced data.150 Importantly, oversampling techniques should only be applied—as all data transformations—after the split into training and test sets.

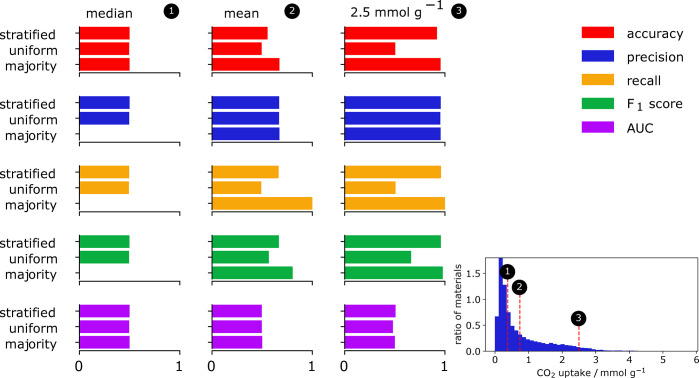

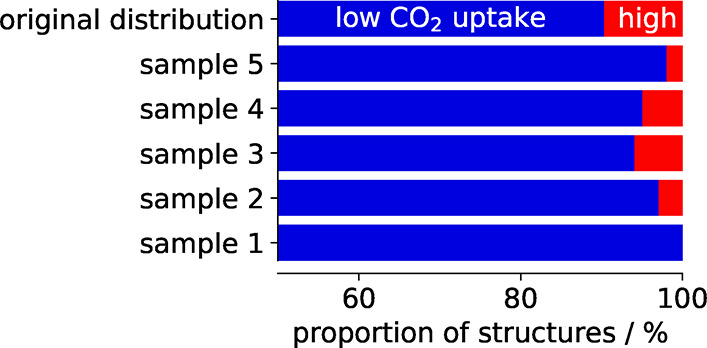

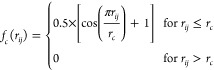

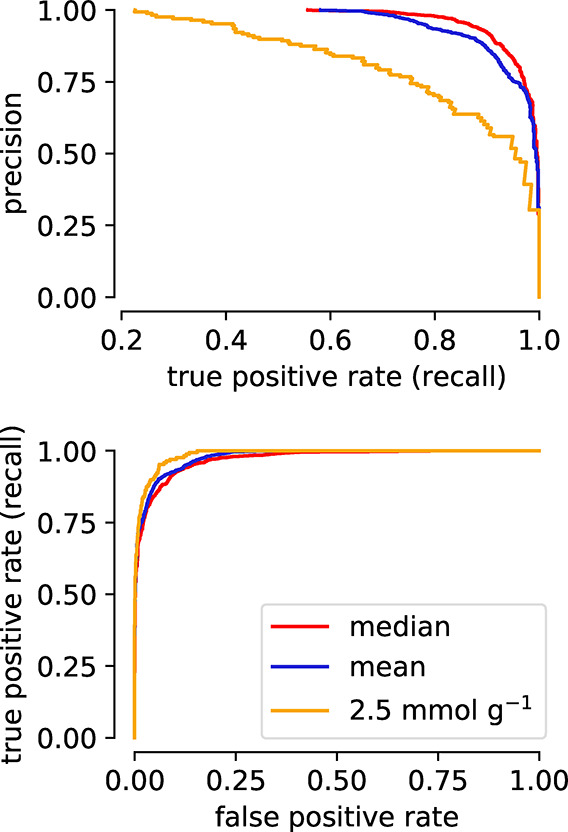

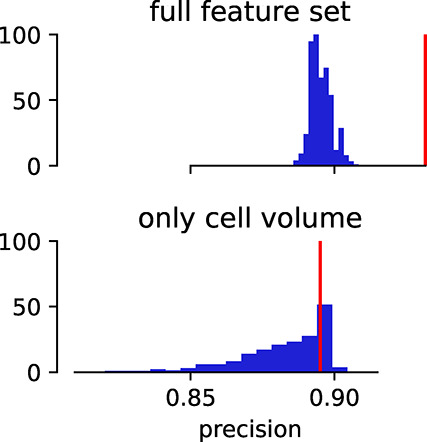

In any case, it is also advisible to use stratified sampling which ensures that the class proportions in the training set are equal to the ones in the test set. An example of the influence of stratified sampling is shown in Figure 5 where we contrast the random with the stratified splitting of structures from the database of Boyd et al.13

Figure 5.

Example for the importance of stratification. For this example, we use a threshold of 2.5 mmol CO2/g to group structures in low and high performing materials, which is slightly higher than the threshold chosen by Boyd et al.13 Then, we randomly draw 100 structures and can observe that the class distribution gets distorted—sometimes we do not have any high performing materials in our sample. Stratification can be used to remedy this effect.

4. What to Learn from: Translating Structures into Feature Vectors

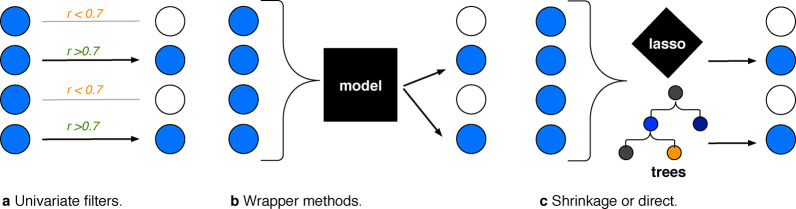

After having reviewed the rows of the feature matrix, we now focus on the columns and discuss ways to generate those columns (descriptors) and how to select the best ones (as more is not always better in the case of feature columns). The possibilities for structural descriptors are so vast that it is impossible to give a comprehensive overview, especially since there is no silver bullet and the performance of descriptors depends on the problem and the learning setting. In some cases, local fingerprints based on symmetry functions might be more appropriate, e.g., for potential energy surfaces, whereas in other cases, where structure–property insights are needed, higher-level features such as pore shapes and sizes can be more instructive.

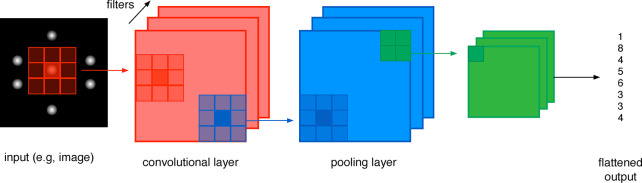

An important distinction of NNs compared to classical ML models, like kernel methods (cf. section 5.2.2), is that NNs can perform representation learning; that is, the need for highly engineered structural descriptors is less pronounced than for “classical” learners as NN can learn their own features from unstructured data. Therefore, one will find NN models that directly use the positions and the atomic charges whereas such an approach is deemed to fail with classical ML models, like kernel ridge regression (KRR), that rely on structured data. The representation learning of NNs can potentially leverage regularities in the data that cannot be described with classical descriptors—but it only works with large amounts of data. We will discuss this in more detail when we revisit special NN architectures in section 5.1.1.2.

The quest for good structural descriptors is not new. Cheminformatics researchers tried to devise strategies to describe structures, e.g., to determine whether a compound has already been deposited on the chemical abstract services (CAS) database, which led to the development of Morgan fingerprints.153 Also the demand for a quantitative structure activity relationship (QSAR) in drug development led to the development of a range of descriptors that are often highly optimized for a specific application (also because simple linear models have been used) as well as heuristics (e.g., Lipinkski’s rule of five154). But also fingerprints (e.g., Daylight fingerprints)—i.e., representations of the molecular graphs have been developed. We will not discuss them in detail in this review as most of them are not directly applicable to solid-state systems.155,156 Still, one needs to note that for the description of MOFs one needs to combine information about organic molecules (linkers), metal centers, and the framework topologies wherefore not all standard featurization approaches are ideally suited for MOFs. Therefore, molecular fingerprints can still be interesting to encode the chemistry of the linkers in MOFs, which can be important for electronic properties or more complex gas adsorption phenomena (e.g., involving CO2, H2O).

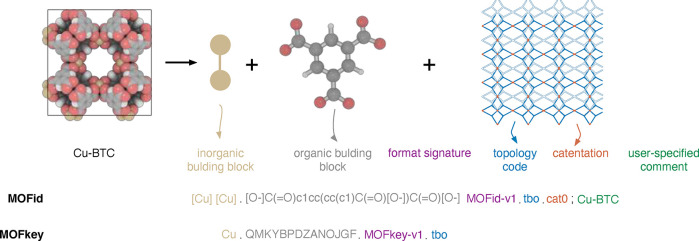

A decomposition of MOFs into the building blocks and encoding of the linker using SMILES was proposed in the MOFid scheme from Bucior et al. (cf. Figure 6).157 This scheme is especially interesting to generate unique names for MOFs and in this way to simplify data-mining efforts. For example, Park et al. had to use a six-step process to identify whether a string represents the name of a MOF in their text-mining effort,158 and then one still has to cope with nonuniqueness problems (e.g., Cu-BTC vs HKUST-1). One main problem of such fingerprinting approaches for MOFs is that they require the assignment of bonds and bond orders, which is not trivial for solid structures,159 and especially for experimental structures that might contain disorder or incorrect protonation.

Figure 6.

Building principle of the MOFid and MOFkey identifiers for HKUST-1. Bucior et al. use a SMILES derived format in the MOFid and whereas the MOFkey is inspired by the InChIkey format, which is a hashed version of the InChi fingerprint, which is more standardized than SMILES. Figure adopted from Bucior et al.157

The most popular fingerprints for molecular systems are implemented and documented in libraries like RDKit,160 PaDEL,161 or Mordred.162 For a more detailed introduction into descriptors for molecules we can recommend a review by Warr163 and the Deep Learning for the Life Sciences book,164 which details how to build ML systems for molecules.

4.1. Descriptors

There are several requirements that an ideal descriptor should fulfill to be suitable for ML:165,166

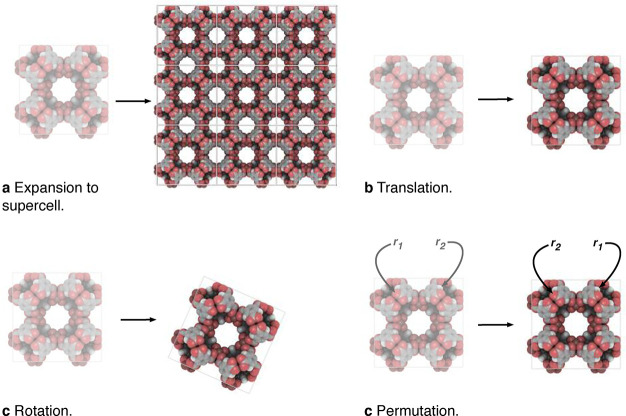

A descriptor should be invariant with respect to transformations that preserve the target property (cf. Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Illustration of transformations of crystal structures to which an ideal descriptor should be invariant. Structures drawn with iRASPA.167

For crystal structures, this means that the representations should respect periodicity, translational, rotational, and permutation symmetry (i.e., the numbering of the atoms in the fingerprint should not influence the prediction). Similarly, one would want equivariances to be conserved. Equivariant functions transform in the same way as their arguments, as is, for example, the case for the tensorial properties like the force (negative gradient of energy) or the dipole moment, which both translate the same way as the positions.168,169

Respecting those symmetries is important from a physics perspective as (continuous) symmetries are generally linked to a conserved property (cf. Noether’s theorem, e.g., rotational invariance corresponds to conservation of angular momentum). Conceptually, this is different from classical force field design where one usually focuses on correct asymptotic behavior. In ML, the intuition is to rather use symmetries to preclude completely nonphysical interactions.

As discussed above, one could in principle also attempt to include those symmetries using data augmentation techniques, but it is often more robust and efficient to “hard-code” them on the level of the descriptor. Notably, the introduction of the invariances on the descriptor level also removes alignment problems, when one would like to compare two systems.

A descriptor should be unique (i.e., nondegenerate). This means that each structure should be characterized by one unique descriptor and that different structures should not share the same descriptor. When this is not the case, the model will produce prediction errors that cannot be removed with the addition of data.170 Von Lilienfeld et al. nicely illustrate this in analogy to the proof of the first Hohenberg–Kohn theorem trough reductio ad absurdum.171 This uniqueness is automatically the case for invertible descriptors.

A descriptor should allow for (cross-element) generalization. Ideally, one does not want to be limited in system size or system composition. Fixed vector or matrix descriptors, like the Coulomb matrix (see section 4.2.2.3), can only represent systems smaller than or equal to the dimensionality of the descriptor. Also, one sometimes finds that the linker type172 or the monomer type is used as a feature. Obviously, such an approach does not allow for generalization to new linkers or monomer types.

The cross-element generalization is typically not possible if different atom types are encoded as being orthogonal (e.g., by using a separate NN for each atom type in a high-dimensional neural network potential (HDNNP) or by grouping interactions by the atomic numbers, e.g., bag of bonds (BoB), partial radial distribution function (RDF)). To introduce generalizability across atom types one needs to use descriptors that allow for a chemically reasonable measure of similarity between atom types (and trends in the periodic table). What an appropriate measure of similarity is depends on the task at hand, but an example for a descriptor that can be relevant for chemical reactivity or electronic properties is the electronegativity.

A descriptor should be efficient to calculate. The cardinal reason for using supervised ML is to make simulations more efficient or to avoid expensive experiments or calculations. If the descriptors are expensive to compute, ML no longer fulfills this objective and there is no reason to add a potential error source.

A descriptor should be continuous: For differentiability, which is needed to calculate, e.g., forces, and for some materials design applications61 it is desirable to have continuous descriptors. If one aims to use the force in the loss function (force-matching) of a gradient descent algorithm, at least second order differentiability is needed. This is not given for many of the descriptors which we will discuss below (like global features as statistics of elemental properties) and is one of the main distinctions of the symmetry functions from the other, often not localized, tabular descriptors which we will discuss.

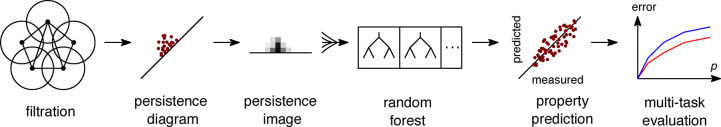

Before we discuss some examples in more detail, we will review some principles that we should keep in mind when designing the columns of the feature matrix.

4.1.0.1. Curse of Dimensionality

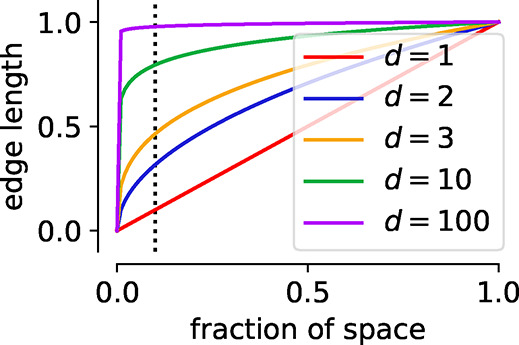

One of the main paradigms that guide the development of materials descriptors is the so-called curse of dimensionality, which describes that it is often hard to find decision boundaries in a high-dimensional space as the data often no longer covers the space. For example, in 100 dimensions nearly the full edge length is needed to capture 10% of the total volume of the 100-dimensional hypercube (cf. Figure 8). This is also known as empty space phenomenon and describes that similarity-based reasoning can fail in high dimensions given that also the nearest neighbors are no longer close in such high-dimensional spaces.90 Often, this is also discussed in terms of Occam’s razor: “Simpler solutions are more likely to be correct than complex ones.” This not only reflects that learning in high-dimensional space brings its own problems but also that simplicity, which might be another way of asking of explainability, for itself is a value (due to its aesthetics) we should strive for.173 More formally, this is related to the minimum descriptor length principle174 which views learning as a compression process and in which the best model is the smallest one in terms of itself and the data (this idea is rooted in Solomonoff’s general theory of inference175).176,177

Figure 8.

Illustration of the empty space phenomenon (the curse of dimensionality). For this illustration we consider the data to be uniformly distributed in a d dimensional unit cube. The edge length of a hypercube corresponding to a fraction q of the total volume is q1/d, which we plotted here for different d. The dotted line in the figure represents 10% of the volume, for which we would nearly need to consider the full edge length in 100-dimensional space. This means that locality is lost in high dimensions, which can be problematic for algorithms that use the local neighborhood for their reasoning.

4.1.0.2. Chemical Locality Assumption

Many descriptors that we discuss below are based on the assumption of chemical locality, meaning that the total property of a compound can be decomposed into a sum of contributions of local (atom-centered) environments:

| 1 |

This approximation (cf. eq 1) is often used in models describing the PES.

The locality approximation is usually justified based on the nearsightedness principle of electronic matter, which says that a perturbation at a distance has little influence on the local density.178 And this “nearsighted” approach also guided the development of many-body potentials like embedded atom methods, linear-scaling DFT methods, or other coarse-grained models in the past (also here the system is divided into subsystems).179,180

The division into subsystems can also be a feat for training of ML models, as one can learn on fragments to predict larger systems, as it has been done for example for a HDNNP for MOF-5.125 Also, this approach makes it easier to incorporate size extensivity, i.e., to ensure that the energy of a system composed of the subsystems A + B is indeed the sum of the energies of A and B.181

But such an approach might be less suited for cases like gas adsorption where both the local chemical environment (especially for chemisorption) but also the pore shape, size, and accessibility play a role—i.e., one wants pore-centered descriptors rather than atom-centered descriptors. For this case global, “farsighted”, descriptors of the pore size and shape, like pore limiting diameters, accessible surface areas,182−184 or persistent homology fingerprints,185 can be better suited. This is important to keep in mind as target similarity, i.e., how good we can approach the property of interest (e.g., the PES or the gas adsorption properties), is one of the main contributions to the error of ML models.186 Also, one should be aware that typically cutoffs of 6 Å around an atom are used to define the local chemical environments. In some systems, the physics of the phenomenon is, however, dominated by long-range behavior187 that cannot be described within the locality approximation. Correctly describing such long-range effects is one of the main challenges of ongoing research.188

Importantly, a model that assumes atom-centered descriptors is invariant to the order of the inputs (permutational invariance).189 Interestingly, classical force fields do not show this property. The interactions are defined on a bond graph, and the exchange of an atom pair can change the energy.168,190

4.2. Overview of the Descriptor Landscape

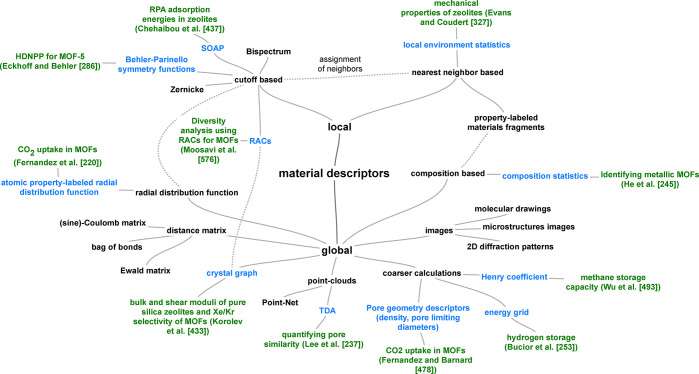

In Figure 9 we show an overview of the space of material descriptors. We will make distinct two main classes of descriptors: local ones, that only describe the local (chemical) environment, and global ones, which describe the full structures at once.

Figure 9.

Nonexhaustive overview over the landscape of descriptors for solids. In blue, we highlighted descriptors for which we are aware of an application in the field of porous materials, for which we give an example in green.

Nearly as vast as the descriptor landscape is the choice of tools that are available to calculate these descriptors. Some notable developments are the matminer package,191 which is written in Python, the DSCribe package, which has a Python interface, but where the computationally expensive routines are written in C/C++ and AMP, which also has a Python interface and where the expensive fingerprinting can be performed in Fortran.192 The von Lilienfeld group is currently also implementing efficient Fortran routines in their QML package.193 Other packages like CatLearn,194 which also has functionalities for surfaces, or QUIP,195 aenet,196 and simple-nn,197 ai4materials198 also contain functions for fingerprinting of solid systems. For the calculation of features based on elemental properties, i.e., statistics based on the chemical composition, the Magpie package is frequently used.199

4.2.0.1. General Theme of Local and Global Fingerprints

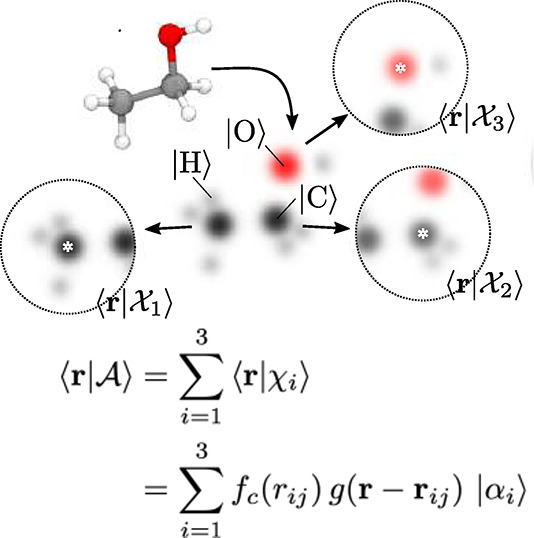

In the following, we will also see that many fingerprinting approaches are just a variation of the same theme, namely many-body correlation functions, which can be expressed in Dirac notation as

| 2 |

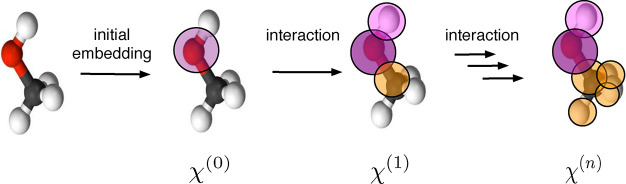

This shows that the abstract atomic configuration |χj(v)⟩, in terms of the (v + 1)-body correlation, can be described with a cross-correlation function (g(2) being equivalent to the radial distribution function) and information about the elemental identity of atom i, |αi⟩ (see Figure 10). And it also already indicates why the term “symmetry functions” is often used for functions of this type. Descriptors based on eq 2 are said to be symmetrized, e.g., invariant to translations of the entire structure (symmetrically equivalent positions will give rise to the same fingerprint).

Figure 10.

Illustration of the concept of featurization using symmetry functions. There are atom centered local environments that we can represent with abstract kets |χ⟩, expressed in the basis of Cartesian coordinates ⟨r|. The figure is a modified version of an illustration from Ceriotti and co-workers.200

Some fingerprints take into account higher orders of correlations (like triples in the bispectrum) but the idea behind most of them is the same—they are just projected onto a different basis (e.g., spherical harmonics, ⟨nlm|, instead of the Cartesian basis ⟨r|).200,201 Notably, it was recently shown that also three-body descriptors do not uniquely specify the environment of an atom, but Pozdnyakov et al. also showed that in combination with many neighbors, such degeneracies can often be lifted.202

Different flavors of correlation functions are used for both local and global descriptors, and the different flavors might converge differently with respect to the addition of terms in the many-body expansion (going from two-body to the inclusion of three-body interactions and so on).203 Local descriptors are usually derived by multiplying a version (projection onto some basis) of the many-body correlation function with a smooth cutoff function such as

|

3 |

where rcut is the cutoff radius which determines the set of i the summation in eq 2 runs over.

We will start our discussion with local descriptors that use such a cutoff function (cf. eq 3) and which are usually employed when atomic resolution is needed.

In some cases, especially when only the nearest neighbors should be considered, Voronoi tessellations are used to assign which atoms from the environment should be included in the calculation of the fingerprint. This approach is based on the nearest neighbor assignment method that was put forward by O’Keeffe.204

4.2.1. Local Descriptors

4.2.1.1. Instantaneous Correlation Functions via Cutoff Functions

For the training of models for PES, flavors of instantaneous correlation functions have become the most popular choices and are often used with kernel methods (cf. section 5.2.2) or HDNNP (cf. section 5.1.1.1).

The archetypal examples of this type are the atom-centered symmetry functions suggested by Behler and Parinello, where the two-body term has the following form

| 4 |

which is a sum of Gaussians, and the number of neighbors that are taken into account in the summation is determined by the cutoff function fc (cf. eq 3). Behler and Parinello also suggest a three-order term, which takes all the internal angles for triplets of atoms, θijk, into account. This featurization approach has been the driver of the development of many HDNNPs (cf. section 5.1.1.1).

One should note that these fingerprints contain a set of hyperparameters that should be optimized, like the shift Rs or the width of the Gaussian η, for which usually a set of different values is used to fingerprint the environment. Also, similar to molecular simulations, the cutoff rc is a parameter that should be carefully set to ensure that the results are converged.

Fingerprints of this type (cf. eq 2) are translational invariant, because they only depend on internal coordinates, and rotational invariant, because they only depend on internal angles (in the case of the v = 3 correlation). The permutation invariance is due to the summation (which does not depend on the order) over all neighbors i, in eq 4 (and also in the locality approximation itself, cf. eq 1).

An alternative approach for fingerprinting in terms of symmetry functions has been put forward by Csányi and co-workers.205 They started by proposing the bispectrum descriptor which is based on expanding the atomic density distribution (with Dirac delta functions for g in eq 2) in spherical harmonics. This allows, as advantage over the Behler–Parinello symmetry functions, for systematic improvements via the addition of spherical harmonics.

This corresponds to a projection of the atomic density onto a four-dimensional sphere and representing the location in terms of four-dimensional spherical harmonics.203,206 This descriptor was improved with the smooth overlap of atomic positions (SOAP) methodology, which is a smooth similarity measure of local environments (covariance kernel, which we will discuss in section 5.2.2) by writing g(r) in eq 2 using atom-centered Gaussians as expansions with sharp features (Dirac delta functions in the bispectrum) that are slowly converging.

Given that SOAP is a kernel, this descriptor found the most application in kernel-based learning (which we will discuss below in more detail, cf. section 5.2.2), as it directly defines a similarity measure between environments (overlap between the smooth densities), which has recently extended to tensorial properties.207 This enabled Wilkins et al. to create models for the polarizability of molecules.208

4.2.1.2. Voronoi Tessellation Based Assignment of Local Environments

In some cases the partitioning into Wigner–Seitz cells using Voronoi tessellation is used instead of a cutoff function. These Wigner–Seitz cells are regions which are closer to the central atom than to any other atom. The faces of these cells can then be used to assign the nearest neighbors and to determine coordination numbers.204 Ward et al. used this method of assigning neighbors to construct local descriptions of the environment that are not sensitive to small changes that might occur during a geometry relaxation.209 These local descriptors can be based on comparing elemental properties, like the electronegativity, of the central atom to its neighbors

| 5 |

where An is the surface area of the face of the Wigner–Seitz cell and pi and pn are the properties of central and neighboring atoms, respectively.

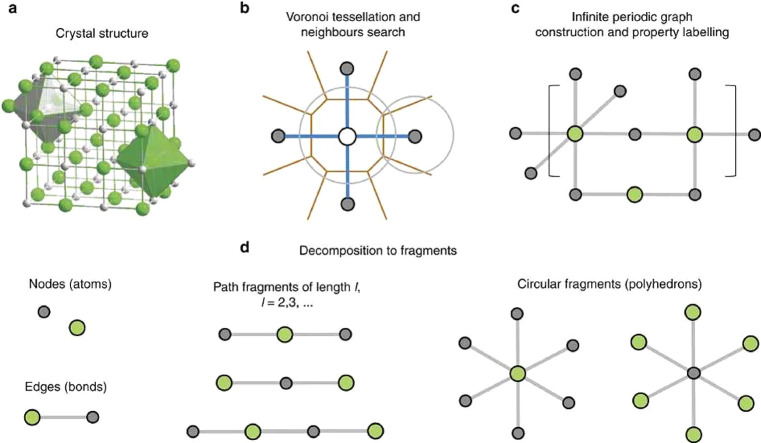

A similar approach was also used in the construction of PLMF which were proposed by Isayev et al.210 There, a crystal graph is constructed based on the nearest-neighbor assignment from the Voronoi tessellation, where the nodes represent atoms that are labeled with a variety of different (elemental) properties. Then, the graph is partitioned into subgraphs and the descriptors are calculated using differences in properties between the graph nodes (neighboring atoms) (cf. Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Schema illustrating the construction of property labeled materials fragments (PLMF). The concept behind this descriptor is that for crystal structure (a) the nearest neighbors are assigned using Voronoi tessellation (b) and then used to construct a crystal graph that can be colored with properties, which is then decomposed into subgraphs (d). Figure reprinted from Isayev et al.210

The Voronoi decomposition is also used to assign the environment in the calculation of the orbital field matrix descriptor, which is the weighted sum of the one-hot encoded vector of the electron configuration.211 One hot-encoding is a technique that is frequently used in language processing and that represents the feature vector of n possibilities with zeros (feature not present) and ones (feature present). In the original work, the sum and average of the local descriptors were used as descriptors for the entire structure and also suggested to gain insight into the importance of specific electronic configurations using a decision tree analysis.

Voronoi tesselation is the dual problem of Delaunay triangulation which attempts to assign points into tetrahedrons (in three dimensions, in two dimensions into triangles, etc.) which circumspheres contain no other point in its interiors. The Delaunay tesselation found use in the analysis of zeolites, where the geometrical properties of the tetrahedrons, like the tetrahedrality or the volume, have been used to build models that can classify zeolite framework types.212,213

Overall, we will see that a common approach to generate global, fixed length, descriptors is that one calculates statistics (like the mean, standard deviation, or maximum or minimum) of base descriptors, that can be based on elemental properties for each site.

4.2.2. Global Descriptors

4.2.2.1. Global Correlation Function

As already indicated, some properties are less amenable to decomposition into contributions of local environments and might be better described using the full, global correlation functions. These approaches can be seen, completely analogous to the local descriptors, as approximations to the many-body expansion, for example for the energy

| 6 |

As we discussed in the context of the symmetry functions for local environments, we can choose where we truncate this expansion (two-body pairwise distance terms, three-body angular terms, ...) to trade-off computational and data efficiency (more terms will need more training data) against uniqueness. Similar to the symmetry functions for local chemical environments, different projections of the information have been developed. For example, the BoB representation214 bags different off-diagonal elements of the Coulomb matrix into bags depending on the combination of nuclear charges and has then been extended to higher-order interactions in the bond-angles machine learning (BAML) representation.186 A main motivation behind this approach, which has been generalized in the many-body tensor representation (MBTR) framework,215 is to have a more natural notion of chemical similarity than the Coulomb repulsion terms. One problem with building bags is that they are not of fixed length and hence need to be padded with zeros to make them applicable for most ML algorithms.

An alternative method to record pairwise distances, that is familiar to chemists from XRD, is the RDF, g(2)(r). Here, pairwise distances are recorded in a binned fashion in histograms. This representation inspired Schuett et al. to build a ML model for the density of states (DOS).216 They use a matrix of partial RDFs, i.e., a separate RDF for each element pair—similar to how the element pairs were recorded in different bags in the BoB representation and quite similar to Valle’s crystal fingerprint217 in which modified RDFs for each element pair are concatenated.

Von Lilienfeld et al. took inspiration in the plane-wave basis sets of electronic structure calculations, which remove many problems that local (e.g., Gaussian) basis sets can cause, e.g., Pulay forces and basis set superposition errors, and created a descriptor that is a Fourier series of atomic RDFs. Most importantly, the Fourier transform removes the translational variance of local basis sets—which is one of the main requirements for a good descriptor.171 The Fourier transform of the RDF also is directly related to the XRD pattern which has found widespread use in ML models for the classification of crystal symmetries.131,218,219

For the prediction of gas adsorption properties property labeled RDFs have been introduced by Fernandez et al.220 The property labeled RDF is given by

| 7 |

where Pi and Pj are elemental properties of atom i and j in a spherical volume of radius R. B is a smoothing factor, and f is a scaling factor. It was designed based on the insight that for some type of adsorption processes, like CO2 adsorption, not only the geometry but also the chemistry is important. Hence, they expected that stronger emphasis on e.g. the electronegativity might help the ML model.

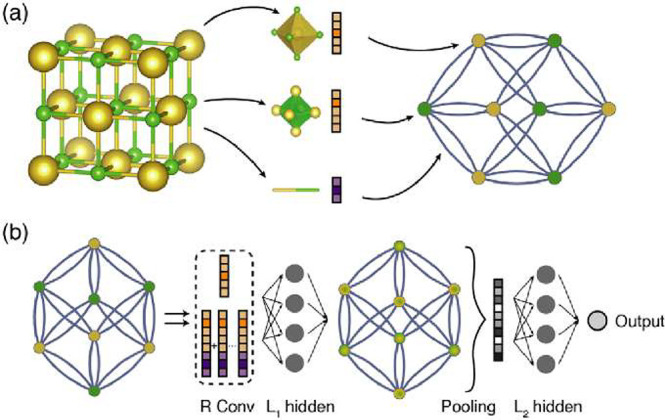

4.2.2.2. Structure Graphs