Abstract

Introduction:

Incomplete head and neck cancer resection occurs in up to 85% of cases, leading to increased odds of local recurrence and regional metastases; thus, image-guided surgical tools for accurate, in situ and fast detection of positive margins during head and neck cancer resection surgery are urgently needed. Oral epithelial dysplasia and cancer development is accompanied by morphological, biochemical, and metabolic tissue and cellular alterations that can modulate the autofluorescence properties of the oral epithelial tissue.

Objective:

This study aimed to test the hypothesis that autofluorescence biomarkers of oral precancer and cancer can be clinically imaged and quantified by means of multispectral fluorescence lifetime imaging (FLIM) endoscopy.

Methods:

Multispectral autofluorescence lifetime images of precancerous and cancerous lesions from 39 patients were imaged in vivo using a novel multispectral FLIM endoscope and processed to generate widefield maps of biochemical and metabolic autofluorescence biomarkers of oral precancer and cancer.

Results:

Statistical analyses applied to the quantified multispectral FLIM endoscopy based autofluorescence biomarkers indicated their potential to provide contrast between precancerous/cancerous vs. healthy oral epithelial tissue.

Conclusion:

To the best of our knowledge, this study represents the first demonstration of label-free biochemical and metabolic clinical imaging of precancerous and cancerous oral lesions by means of widefield multispectral autofluorescence lifetime endoscopy. Future studies will focus on demonstrating the capabilities of endogenous multispectral FLIM endoscopy as an image-guided surgical tool for positive margin detection during head and neck cancer resection surgery.

Keywords: Oral Cancer and Dysplasia, Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging (FLIM), Autofluorescence Biomarkers, Statistical Analysis

1. Introduction

About 53,000 new cases of cancer of the oral cavity and pharynx will be diagnosed in the US in 2019, and an estimate of 10,860 people will die of these cancers during the same year [1]. The current standard treatments for oral cancer are surgical resection with or without radiation or chemotherapy [1 2]. During tumor surgical resection, however, surgeons typically rely on visual inspection and palpation to demarcate the subtle interface at the margin between malignant and normal oral tissue [3]. As a result, incomplete tumor resections occur in up to 85% of cases [4 5], leading to increased odds of local recurrences and regional neck metastases, as well as lower survival rates [6]. The standard technique to overcome this limitation is intraoperative histopathological evaluation of frozen sections from random tissue biopsies, which is not only labor-intensive and time-consuming, but also prone to sampling error and has limited specificity [7 8].

The human oral mucosa consists of two major layers: Stratified squamous epithelium and lamina propria or connective tissue. The development of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) causes morphological, functional, and biochemical alterations within these tissue layers, which can modulate the autofluorescence properties of the oral epithelial tissue. Specifically, the levels of two metabolic cofactors and endogenous fluorophores, the reduced-form nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH) and flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD), can change as oral cancer develops [9–11]. The optical redox ratio, typically defined as the ratio of fluorescence intensity of NADH to FAD, is sensitive to changes in the cellular metabolic rate [12–15]. Increased cellular metabolic activity, a hallmark of neoplastic cell transformation, is usually attributed to a decrease in the optical redox ratio [16]. In addition, the fluorescence lifetimes of these metabolic cofactors are sensitive to protein binding, thus to cellular metabolic pathways involving NADH and FAD [17]. As a result, carcinogenesis process has been shown to cause changes in both NADH and FAD fluorescence lifetimes [18]. Finally, oral cancer development also leads to extracellular matrix remodeling occurring within the lamina propria, which together with concurring epithelium thickening, result in a decrease in connective tissue autofluorescence that can be measured [19]. Therefore, interrogation of NADH, FAD and collagen autofluorescence could provide optical biomarkers of oral epithelial cancer.

Several studies have explored the use of autofluorescence spectroscopy and imaging to identify biomarkers of oral SCC. Gillenwater et al. observed increased epithelial autofluorescence and decreased connective tissue autofluorescence in dysplastic vs. normal oral tissue upon ultraviolet excitation [20]. Rosin et al. used fluorescence visualization (FV) in an in vivo study in 20 patients with oral SCC and carcinoma in situ (CIS) to collect the autofluorescence at an >475 nm emission spectral band, and found that all SCC and CIS tumors showed FV loss relative to normal tissue; moreover, in 19 cases the loss in autofluorescence signal extended 4–25 mm in at least one direction beyond the clinically visible tumor [21]. In an in vivo study, Huang et al., using a two-channel autofluorescence device targeting NADH and FAD autofluorescence, reported discrimination of precancerous and cancerous lesions vs. healthy oral mucosa with levels of sensitivity and specificity of ~92% and ~75%, respectively [22].

Time-resolved fluorescence spectroscopy (TRFS) and fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy (FLIM), which allows measuring the fluorescence lifetime of samples, can provide additional sample characterization. Singaravelu et al. performed an ex vivo TRFS study in 15 premalignant and 15 normal oral tissue samples from patients, and reported a significantly shorter lifetime associated to free NADH in premalignant vs. normal oral tissue [23]. In an ex vivo multiphoton FLIM study using human oral tissue samples, Skala et al. reported shorter NADH and FAD average fluorescence lifetimes, and a lower redox ratio in SCC relative to normal oral tissue [24]. Farwell et al. performed an in vivo TRFS study in nine patients with suspected HNSCC and found lower fluorescence intensity across all wavelengths between 360 nm and 610 nm and a shorter lifetime at the 440–470 nm band in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) vs. normal [25]. In an in vivo FLIM study performed in 10 patients with HNSCC, Marcu et al. reported lower fluorescence intensity and shorter average lifetime associated to NADH in HNSCC compared to healthy oral tissue [2].

Encouraged by these pioneering studies and taking advantage of novel multispectral FLIM endoscopy systems recently developed for imaging the oral mucosa [26], we demonstrate in this in vivo human study the capabilities of endogenous wide-field multispectral FLIM endoscopy in differentiating oral SCC/epithelial dysplasia from normal oral tissue; and provide the basis for using autofluorescence biomarkers in the future for rapid and accurate determination of margin involvement in the operation room.

2. Materials and Methods

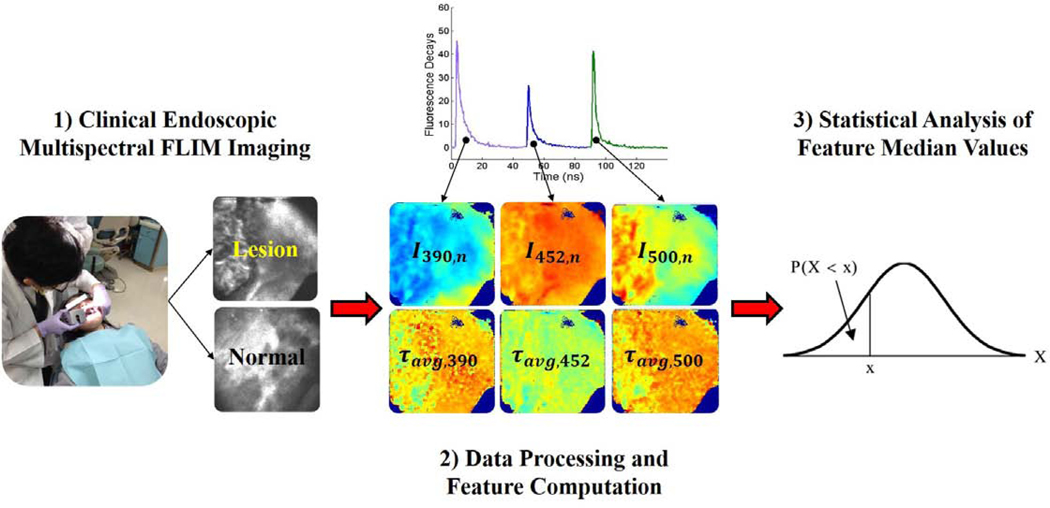

A schematic summarizing the methodology used in this study is presented in Fig. 1 and described in the following sections.

Fig. 1.

Schematic depicting the methodology of this study. First, multispectral FLIM endoscopic imaging of oral lesions is performed in a clinical setting. Second, the data is processed yielding multi-parametric FLIM feature images. Finally, statistical analysis is performed on the feature image median value to assess difference in their distributions between precancerous/cancerous and normal groups.

2.1. Clinical endoscopic multispectral FLIM imaging of oral lesions

In vivo clinical endogenous multispectral FLIM images of dysplastic and cancerous oral lesions were acquired following an imaging protocol approved by the Institutional Review Board at Texas A&M University. For this study, 39 patients, scheduled for tissue biopsy examination of suspicious oral epithelial precancerous or cancerous lesions, were recruited. Following clinical examination of the patient’s oral cavity by an experienced oral pathologist (Y.S.C., J.W.), endogenous FLIM images were acquired from the suspicious oral lesion and a clinically normal-appearing area in the corresponding contralateral anatomical side, using a FLIM endoscope prototype previously reported [26]. With this multispectral FLIM endoscope prototype, tissue autofluorescence excited with a pulsed laser (355 nm, 1 ns pulse width, ~1μJ/pulse at the tissue) was imaged at the emission spectral bands of 390 ± 20 nm, 452 ± 22.5 nm, and > 500 nm, which were selected to preferentially measure collagen, NADH, and FAD autofluorescence, respectively [26]. In order to perform in vivo imaging in a safe manner, the total energy deposited into the patient’s oral mucosa was set to at least an order of magnitude lower than the maximum permissible exposure provided by the American National Standards Institute (ANSI) [27]. The time-resolved autofluorescence signal at each pixel of the FLIM images were acquired with a temporal resolution of 160 ps (sampling rate of 6.25 GS/s). Endoscopic multispectral FLIM images were acquired with a circular field-of-view (FOV) of 10 mm in diameter, lateral resolution of ~100 μm, and acquisition time of <3 s (total acquisition time for the three emission spectral bands). After acquiring all the multispectral FLIM images from the patient’s oral cavity, the tissue biopsy examination procedure was performed following standard clinical protocols. Each imaged lesion was annotated based on its tissue biopsy histopathological diagnosis. The distribution of the 40 imaged oral lesions, based in both anatomical location and histopathological diagnosis, is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Distribution of the 40 imaged oral lesions based in both anatomical location and histopathological diagnosis (MOD-DYS:Moderate Dysplasia; HG-DYS:High-Grade Dysplasia; SCC:Squamous Cell Carcinoma)

| Lesion Location | MOD-DYS | Histopathology Diagnosis HG-DYS | SCC | Total Number |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HG-DYS | ||||

| Buccal Mucosa | 2 | 1 | 11 | 14 |

| Tongue | 1 | 0 | 12 | 13 |

| Gingiva | 0 | 1 | 7 | 8 |

| Lip | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Mandible | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Maxilla | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Floor of Mouth | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Total Number | 3 | 2 | 35 | 40 |

2.2. Data Processing and Feature Computation

The multispectral FLIM data is composed of fluorescence intensity temporal decay signals, yλ(x,y,t), measured at each emission spectral band (λ) and each spatial location or image pixel (x,y). Multispectral absolute and normalized fluorescence intensity values were first computed for each pixel as follows. The multispectral absolute fluorescence intensity Iλ(x,y) was simply computed by numerically integrating the fluorescence intensity temporal decay signal:

| (1) |

The multispectral normalized fluorescence intensity Iλ,n(x,y) was computed from the multispectral absolute fluorescence intensities Iλ(x,y) as follows:

| (2) |

In addition, the multispectral fluorescence intensity values enable estimating a parameter related to the tissue metabolic redox-ratio similar to the one originally proposed by Chance [15]:

| (3) |

In the context of time-domain FLIM data analysis, the fluorescence decay yλ(x,y,t) measured at each spatial location (x,y) can be modeled as the convolution of the fluorescence impulse response (FIR) hλ(x,y) of the sample and the measured instrument response function (IRF) uλ(t):

| (4) |

Therefore, to estimate the sample FIR hλ(x,y,t), the measured IRF uλ(t) needs to be temporally deconvolved from the measured fluorescence decay yλ(x,y,t). In this work, temporal deconvolution was performed using a nonlinear least squares iterative reconvolution algorithm [28], in which the FIR was modeled as a bi-exponential function:

| (5) |

Here, and represent the time-constant (lifetime) of the fast and slow decay components, respectively; while and represent the relative contribution of the fast and slow decay components, respectively. The model order (number of exponential components) was determined based on the model-fitting mean squares error (MSE); since the addition of a third component did not reduce the MSE, a model order of two was selected. Finally, the average fluorescence lifetime for each pixel and emission spectral band were estimated from the FIR hλ(x,y,t) as follows [28]:

| (6) |

In summary, a total of 16 FLIM-derived features were computed per pixel as summarized in Table 2, thus enabling the generation of multi-parametric FLIM feature maps.

Table 2.

Summary of FLIM-derived features computed per pixel for each spectral channel.

| 390 ± 20 nm | 452 ± 22.5 nm | > 500 nm |

|---|---|---|

| I390,n(X,Y) | I452,n(X,Y) | I500,n(X,Y) |

| τa,v,g,390(X,Y) | τa,v,g,452(X,Y) | τa,v,g,500(X,Y) |

| τfast,390(X,Y) | τfast,452(X,Y) | τfast,500(X,Y) |

| τslow,390(X,Y) | τslow,452(X,Y) | τslow,500(X,Y) |

| αfast,390(X,Y) | αfast,452(X,Y) | αfast,500(X,Y) |

| Redox-Ratio(X,Y): I452(X,Y)/I500(X,Y) | ||

2.3. Statistical Analysis

As summarized in Table 1, the 40 imaged oral lesions corresponded to 5 precancerous (3 MOD-DYS, 2 HG-DYS) and 35 cancerous (SCC) lesions, and each imaged oral lesion region was paired with a corresponding clinically healthy or normal oral tissue region. In order to identify statistical differences in the distribution of image median values of each of the 16 FLIM features from normal (healthy) vs. precancerous or cancerous oral tissue, the following statistical analysis was performed. For each imaged oral tissue region, multi-parametric FLIM maps were generated, in which the 16 FLIM features were computed at each image pixel (as in Fig. 4). Then, for each FLIM feature map, the median feature value from all pixels was computed; thus, each imaged oral tissue region was represented by a single feature vector composed of the median values of each of the 16 FLIM feature maps. Finally, a two-tailed paired Student’s t-test was applied to the paired precancerous/cancerous vs. normal median values of each of the 16 FLIM features, with a type-1 error probability of p<0.05 for all tests.

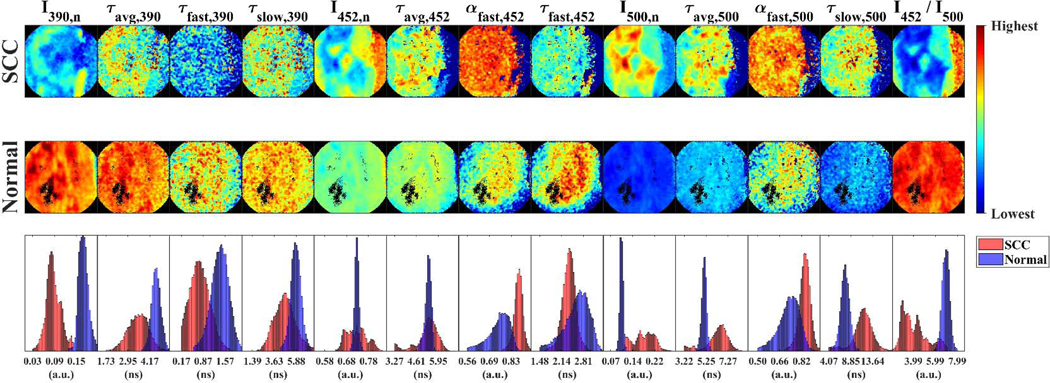

Fig. 4.

Multispectral FLIM feature images or maps of SCC (top panels) and normal (middle panels) tongue tissue from the same patient. Pixel distributions of normal and SCC maps for each feature are also compared (bottom panels). The trends observed in this representative case are consistent with the statistical findings on the feature image median value distributions from precancerous/cancerous vs. normal oral tissue.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Autofluorescence Intensity and Lifetime Trends in Moderate/High-Grade Dysplasia and SCC vs. Normal

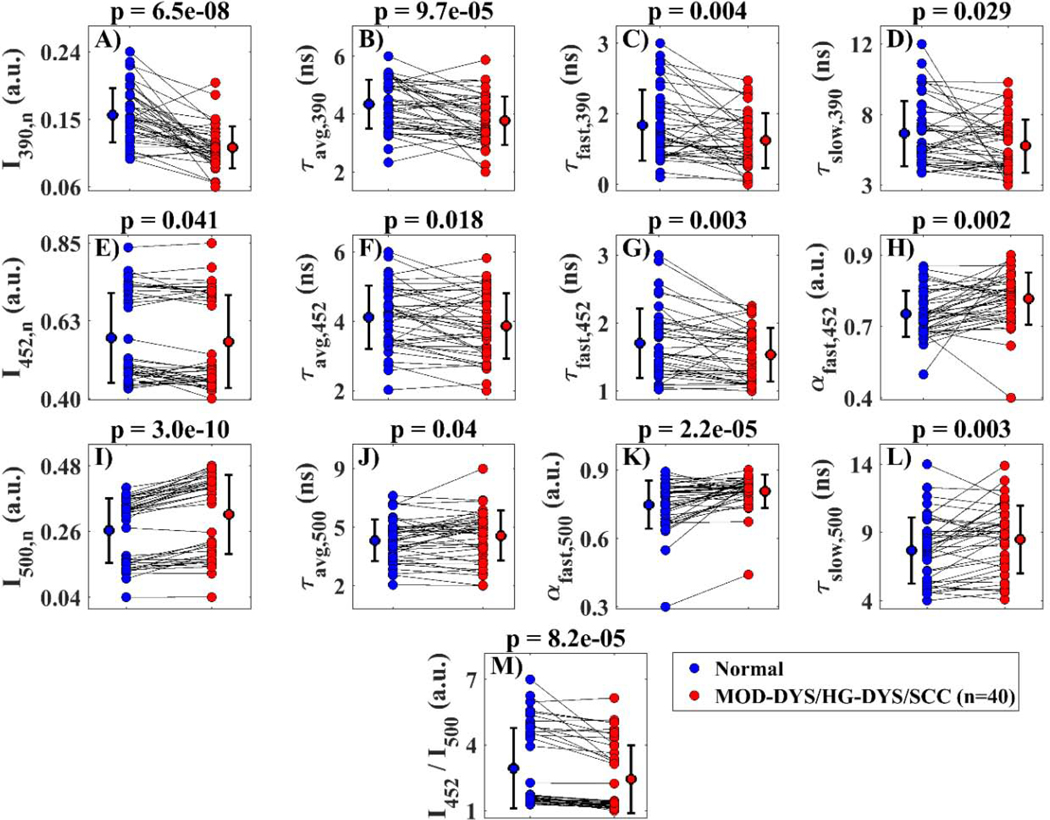

The statistical analysis comparing the feature image median values in MOD-DYS/HG-DYS/SCC vs. the corresponding contralateral normal tissue indicated that 13 FLIM-derived features showed statistically different distributions between the precancerous/cancerous vs. normal oral tissue groups (P < 0.05). Scatter plots of the feature image median value distributions for each oral tissue group are shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Scatter plots of multispectral FLIM feature image median values of moderate dysplastic (MOD-DYS), high grade dysplastic (HG-DYS), and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) oral lesions (n=40; red points) and their paired contralateral normal tissue (blue points). Mean and standard deviation of the distribution of median values for each population are also shown. P-values resulting from two-tailed paired t-tests are shown on top of each plot.

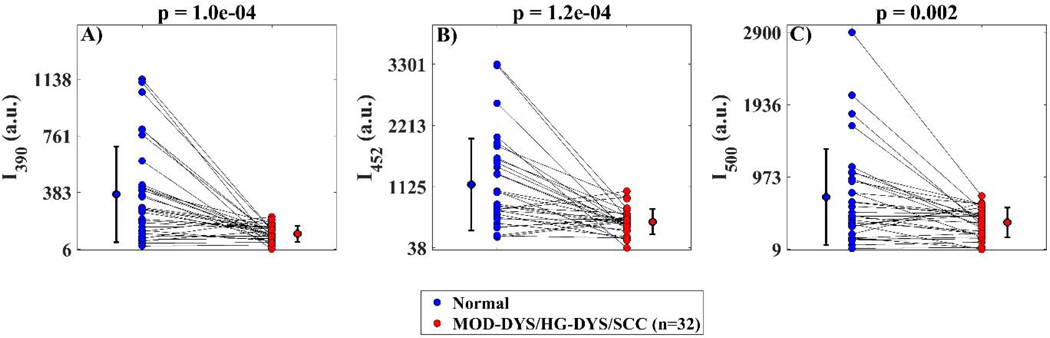

For a subset of oral lesion samples (n = 32) for which the gain of the photodetector was known, statistical analysis was also performed on the absolute intensity values for each of the three spectral channels comparing MOD-DYS/HG-DYS/SCC vs. normal. Results from these analyses are shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Scatter plots of image median value distributions of absolute fluorescence intensity values for each emission spectral band comparing moderate dysplastic (MOD-DYS), high grade dysplastic (HG-DYS), and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) oral lesions (n=32; red points) to their paired normal references (blue points). A statistically significant loss in autofluorescence was observed in precancerous/cancerous oral lesions relative to normal in all channels. P-values resulting from two-tailed paired t-tests are shown on top of each plot.

Multispectral FLIM feature images from a representative lesion corresponding to a SCC of the tongue and its corresponding contralateral normal looking area from the same patient are presented in Fig. 4. The pixel distributions of each paired FLIM feature map reflected the statistical differences in the image median distribution of each FLIM feature from precancerous/cancerous vs. normal oral tissue.

3.2. Discussion

Using a novel multispectral FLIM endoscope [26], it was possible to image the oral cavity of 39 patients presenting precancerous or cancerous oral lesions. The relatively large field-of-view (~80 mm2) and short acquisition time (<3 s per multispectral image) offered by our multispectral FLIM endoscopy system enabled quick and easy in-vivo imaging of oral lesions at the dental clinic. The multispectral FLIM endoscopic images were processed to generate widefield maps of biochemical and metabolic autofluorescence biomarkers of oral precancer and cancer. To the best of our knowledge, this study represents the first demonstration of label-free biochemical and metabolic clinical imaging of precancerous and cancerous oral lesions by means of widefield multispectral autofluorescence lifetime endoscopy.

Processing of the multispectral FLIM images acquired with our endoscope resulted in widefield maps of different autofluorescence spectral and lifetime features. The statistical analysis applied to each of these autofluorescence features identified several ones (Fig. 2 and Fig. 3) that displayed statistically significant differences between precancerous/cancerous vs. healthy oral tissue. In Table 3, the statistical trends of the autofluorescence spectral and lifetime features observed in this study are summarized and compared with previously reported observations.

Table 3.

Summary of statistical trends of FLIM-derived features in Moderate and High-Grade Dysplasia/SCC vs. Normal. TRFS:Time-Resolved Fluorescence Spectroscopy; FLIM:Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging; MPM-FLIM:Multiphoton FLIM; AFS:Autofluorescence Spectroscopy; CFM:Confocal Fluorescence Microscopy; SLS:Synchronous Luminescence Spectroscopy

| Emission Channel | Associated Fluorophore | FLIM-Derived Autofluorescence Features | Moderate and High-Grade Dysplasia / SCC vs. Normal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observed Trend | Previous Studies [Ref.] | |||

| ↓ In Vivo AFS: Hamsters [33] | ||||

| I390 | ↓ | ↓ Ex Vivo CFM: Patients [20] | ||

| I390,n | ↓ | ↓ Ex Vivo SLS: Patients [31] | ||

| ↓ In Vivo FLIM: Hamsters [32] | ||||

| 390 ± 20 nm | Collagen | ↓ In Vivo TRFS: Patients [25] | ||

| τa,v,g,390 | ↓ | Not Reported | ||

| αfast,390 | No Change | Not Reported | ||

| τfast,390 | ↓ | Not Reported | ||

| τslow,390 | ↓ | Not Reported | ||

| ↓ In Vivo FLIM: Patients [2] | ||||

| I452 | ↓ | ↓ In Vivo AFS: Hamsters [33] | ||

| I452,n | ↓ | ↓ Ex Vivo SLS: Patients [31] | ||

| 452 ± 22.5 nm | NADH | τa,v,g,452 | ↓ | ↓ In Vivo TRFS: Patients [25] |

| ↓ In Vivo FLIM: Patients [2] | ||||

| ↓ In Vivo FLIM: Hamsters [32] | ||||

| ↓ Ex Vivo FLIM: Patients [24] | ||||

| ↓ In Vivo TRFS: Patients [25] | ||||

| αfast,452 | ↑ | Not Reported | ||

| τfast,452 | ↓ | ↓ In Vivo MPM-FLIM: Hamsters [18] | ||

| ↓ Ex Vivo TRFS: Patients [23] | ||||

| τslow,452 | No Change | ↓ In Vivo MPM-FLIM: Hamsters [18] | ||

| ↑ In Vivo AFS: Hamsters [33] | ||||

| I500 | ↓ | ↑ Ex Vivo CFM: Patients [20] | ||

| I500,n | ↑ | ↑ Ex Vivo SLS: Patients [31] | ||

| ↑ In Vivo TRFS: Patients [25] | ||||

| > 500 nm | FAD | τavg,500 | ↑ | ↓ Ex Vivo FLIM: Patients [24] |

| αfast,500 | ↑ | ↓ In Vivo MPM-FLIM: Hamsters [18] | ||

| τfast,500 | No Change | ↑ In Vivo MPM-FLIM: Hamsters [18] | ||

| τslow,500 | ↑ | Not Reported | ||

| 452 / 500 nm | Redox-Ratio = NADH / FAD | I452/I500 | ↓ | ↓ In Vivo AFS: Hamsters [33] |

| ↓ Ex Vivo FLIM: Patients [24] | ||||

The autofluorescence in oral mucosa induced by an excitation wavelength of 355 nm and measured at the emission spectral band of 390 ± 20 nm is expected to be predominantly originated from collagen in the lamina propria. Our findings indicated a significant decrease in the normalized autofluorescence intensity at this spectral band in cancerous and precancerous oral lesions relative to healthy oral tissue (I390,n, Fig. 2A), which can be attributed to the breakdown of collagen crosslinks in the connective tissue [19 29] and the increase in both epithelial thickness and tissue optical scattering accompanying dysplastic or cancerous change [30] and is very much in agreement with previous observations from animal and human studies [20 25 31–33].

Moreover, our findings indicated significantly shorter average (τavg,390, Fig. 2B.), fast-component τfast,390, Fig. 2C), and slow-component τslow,390, Fig. 2D) lifetimes at the 390 ± 20 nm emission spectral band in cancerous and precancerous oral lesions compared to healthy oral tissue. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first observation of a faster autofluorescence temporal response at the collagen emission spectral peak in cancerous and precancerous oral lesions. This observation is likely due to the overlap in the emission spectra of collagen and NADH at this spectral band, as a decrease in the slower-decaying collagen signal in precancerous and cancerous epithelial tissue would result in overall faster tissue autofluorescence temporal response; however, further studies are needed to understand these observations.

The oral epithelial tissue autofluorescence induced with an excitation wavelength of 355 nm and measured at the emission spectral band of 452 ± 22.5 nm is expected to be predominantly originated from NADH within oral epithelial cells. Our findings indicated a significant decrease in the normalized autofluorescence intensity at this spectral band in cancerous and precancerous oral lesions relative to healthy oral tissue (I390,n, Fig. 2E), consistent with previous observations [2 25 31 33]. Because of the overlap in the emission spectra of collagen and NADH at the 452 ± 22.5 nm spectral band, this observation is likely attributed to decreased signals in both NADH in epithelial cells and collagen in lamina propria.

Our findings also indicated significantly shorter average lifetime at the 452 ± 22.5 nm emission spectral band in cancerous and precancerous oral lesions compared to healthy oral tissue (τavg,452, Fig. 2F), consistent with previous observations [2 24 25 32]. This observation is likely caused by the overlap in the emission spectra of collagen and NADH at the 452 ± 22.5 nm emission spectral band, as a decrease in the slower-decaying collagen signal in precancerous and cancerous epithelial tissue would result in overall faster tissue autofluorescence temporal response.

Previous studies on animal models of oral cancer using multiphoton FLIM microscopy at ~800 nm two-photon excitation have linked the fast and slow component lifetimes of the epithelial tissue autofluorescence at ~450 nm to intracellular free and bound NADH, respectively [18]. Fast (τfast,452) and slow (τslow,452) component lifetimes of the tissue autofluorescence at ~450 nm were also quantified from our widefield FLIM endoscopy images; however, due to the lack of axial resolution of the FLIM endoscope, it is more likely that they reflect epithelial NADH (τfast,452) and connective tissue collagen (τslow,452) instead of free/bound NADH. The observed significantly shorter lifetime (τfast,452, Fig. 2G) in cancerous and precancerous oral lesions compared to healthy oral tissue might be explained by the increased use of glycolysis in addition to oxidative phosphorylation as complementary metabolic pathways in neoplastic cells [34], as glycolysis requires the reduction of NAD+ into NADH, resulting in increased NADH/NAD+ ratio and quenched NADH fluorescence [35]. The observed significantly larger relative contribution of the fast-component (αfast,452, Fig. 2H) is likely caused by the decrease in collagen fluorescence associated to the slow component (τslow,452).

The oral epithelial tissue autofluorescence induced with an excitation wavelength of 355 nm and measured at the emission spectral band > 500 nm is expected to be predominantly originated from FAD within oral epithelial cells. Our findings indicated a significant increase in the normalized autofluorescence intensity at this spectral band (I500,n, Fig. 2I) in cancerous and precancerous oral lesions relative to healthy oral tissue, consistent with previous observations [20 25 31 33]. Oxidative phosphorylation, the most efficient cellular metabolic pathway, requires the oxidation of FADH2 into FAD; thus, the higher metabolic rate of malignant cells would result in higher concentration of mitochondrial FAD, which might explain this observation [35].

Previous studies using multiphoton FLIM microscopy at ~900 nm two-photon excitation have linked the average lifetime of oral tissue autofluorescence imaged at ~500–600 nm to the lifetime of oral epithelial FAD autofluorescence [24], and the fast and slow component lifetimes of oral tissue autofluorescence imaged at a similar emission band to the lifetimes of oral intracellular bound and free FAD autofluorescence, respectively [18]. Average (τavg,500), fast-component (τavg,500) and slow-component (τslow,452) lifetimes of oral tissue autofluorescence at > 500 nm were also quantified from our widefield FLIM endoscopy images. Due to the single-photon 355 nm excitation and broad emission spectral band used in the FLIM endoscope, it is quite possible that the tissue autofluorescence imaged at the > 500 nm spectral band could come not only from FAD but also from NADH and/or porphyrin; thus, it is unlikely that τavg,500, τfast,500 and τslow,500 would only reflect total or free/bound FAD. Nevertheless, although further studies are needed to understand the observed longer αfast,500 (Fig. 2J), larger τslow,500 (Fig. 2K) and slower τslow,500 (Fig. 2L) in cancerous and precancerous oral lesions relative to healthy oral tissue, these results suggest that these endoscopic FLIM features could potentially represent novel autofluorescence biomarkers of oral epithelial dysplasia and cancer.

Since the oral epithelial tissue autofluorescence induced with 355 nm excitation and measured at the emission spectral bands of 452 ± 22.5 nm and > 500 nm are expected to be predominantly originated from epithelial NADH and FAD, respectively, the autofluorescence intensity ratio I452/I500 can be associated to the optical redox-ratio [15]. Our findings indicated a significant decrease in I452/I500 in cancerous and precancerous oral lesions relative to healthy oral tissue (Fig. 2M), consistent with previous observations [24 33]. Oxidative phosphorylation requires the oxidation of both NADH and FADH2 molecules, resulting in decreased NADH/FAD redox-ratio [35]. Thus, the observed decreased I452/I500 in cancerous and precancerous oral lesions could reflect increased cellular metabolic activity, a hallmark of epithelial cell malignant transformation [16]. Finally, our findings also indicated significantly reduced absolute autofluorescence intensities at all three spectral bands in cancerous and precancerous oral lesions relative to healthy oral tissue (I390, I452, I500, Fig. 3), also consistent with previous observations [2 20 25 32 33].

Study Limitations

Although this study demonstrates the capabilities of endogenous multispectral FLIM endoscopy to enable label-free biochemical and metabolic clinical imaging of precancerous and cancerous oral lesions, some important limitations of the study warrant discussion. The multispectral FLIM endoscope used in this study was designed to preferentially interrogate the contributions of collagen, NADH and FAD in the oral tissue autofluorescence; however, it did not enable their specific interrogation due to the use of a single excitation wavelength and relatively broad emission spectral bands. In addition, the limited lateral resolution and lack of optical axial sectioning capabilities of the multispectral FLIM endoscope did not allow cellular resolution imaging of the epithelial layer independently from the submucosa. Current efforts by our group to further develop the multispectral FLIM endoscopy design include: the use of dual wavelength excitation and narrower emission spectral bands to enable more specific interrogation of collagen, NADH, FAD and porphyrin autofluorescence; the adoption of a novel frequency-domain FLIM implementation to significantly reduce endoscopy instrumentation complexity and cost [36]; and the addition of structured illumination based optical sectioning to enable more specific epithelial interrogation [37]. The statistical analyses applied to the quantified multispectral FLIM endoscopy based autofluorescence biomarkers showed their promising potential to differentiate between precancerous/cancerous from healthy oral epithelial tissue. However, these encouraging preliminary results need to be further validated. Current efforts by our group aim to thoroughly assess the capabilities of endogenous multispectral FLIM endoscopy as an image-guided surgical tool for detecting positive margins during head and neck cancer resection surgery.

4. Conclusion

This study represents, to the best of our knowledge, the first demonstration of label-free biochemical and metabolic clinical imaging of precancerous and cancerous oral lesions by means of widefield multispectral autofluorescence lifetime endoscopy. Moreover, a number of both established and potentially new autofluorescence biochemical and metabolic biomarkers of oral epithelial dysplasia and SCC were successfully imaged and quantified. This first-of-a-kind study has demonstrated the capabilities of endogenous multispectral FLIM endoscopy in differentiating precancerous/cancerous oral lesions from healthy oral tissue. Future studies will assess the capabilities of endogenous multispectral FLIM endoscopy as an image-guided surgical tool for rapidly and accurately determining margin involvement during head and neck cancer resection surgery.

Supplementary Material

Autofluorescence lifetime imaging (FLIM) endoscopy of oral lesions was demonstrated

FLIM endoscopy enables label-free biochemical and metabolic imaging of oral lesions

Autofluorescence biomarkers provided contrast in cancerous vs. normal oral tissue

5. Acknowledgments

This project was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH grants R01CA138653, R01CA218739). This work was also made possible by the grant NPRP8-1606-3-322 from the Qatar National Research Fund (a member of Qatar Foundation). The statements made herein are solely the responsibility of the authors.

Role of the funding source: Funding for the development of the FLIM endoscope and for the imaging protocol was provided by grants R01CA138653 (PI: K. Maitland) and NPRP8-1606-3-322 (PI: J.A. Jo). Funding for the data analysis and interpretation was provided by grant R01CA218739 (PI: J.A. Jo).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: All authors have read and approved the manuscript and have declared that they do not have any conflict of interest that could be perceived as prejudicing the impartiality of the research reported.

Conflict of Interest Statement

All authors have read and approved the manuscript and have declared that they do not have any conflict of interest that could be perceived as prejudicing the impartiality of the research reported.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

6 References

- 1.Society AC. American Cancer Society: Cancer Facts and Figures 2019: American Cancer Society; Atlanta, GA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sun Y, Phipps JE, Meier J, et al. Endoscopic fluorescence lifetime imaging for in vivo intraoperative diagnosis of oral carcinoma. Microsc Microanal 2013;19(4):791–8 doi: 10.1017/S1431927613001530[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kain JJ, Birkeland AC, Udayakumar N, et al. Surgical margins in oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma: Current practices and future directions. The Laryngoscope 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smits RW, Koljenović S, Hardillo JA, et al. Resection margins in oral cancer surgery: room for improvement. Head & neck 2016;38(S1):E2197–E203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Slooter MD, Handgraaf HJ, Boonstra MC, et al. Detecting tumour-positive resection margins after oral cancer surgery by spraying a fluorescent tracer activated by gamma-glutamyltranspeptidase. Oral oncology 2018;78:1–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hinni ML, Ferlito A, Brandwein-Gensler MS, et al. Surgical margins in head and neck cancer: a contemporary review. Head & neck 2013;35(9):1362–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mair M, Nair D, Nair S, et al. Intraoperative gross examination vs frozen section for achievement of adequate margin in oral cancer surgery. Oral surgery, oral medicine, oral pathology and oral radiology 2017;123(5):544–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DiNardo LJ, Lin J, Karageorge LS, Powers CN. Accuracy, utility, and cost of frozen section margins in head and neck cancer surgery. The Laryngoscope 2000;110(10):1773–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Müller MG, Valdez TA, Georgakoudi I, et al. Spectroscopic detection and evaluation of morphologic and biochemical changes in early human oral carcinoma. Cancer: Interdisciplinary International Journal of the American Cancer Society 2003;97(7):1681–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shah AT, Beckler MD, Walsh AJ, Jones WP, Pohlmann PR, Skala MC. Optical metabolic imaging of treatment response in human head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. PloS one 2014;9(3):e90746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jo JA, Applegate BE, Park J, et al. In vivo simultaneous morphological and biochemical optical imaging of oral epithelial cancer. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering 2010;57(10):2596–99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gulledge C, Dewhirst M. Tumor oxygenation: a matter of supply and demand. Anticancer research 1996;16(2):741–49 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Drezek R, Brookner C, Pavlova I, et al. Autofluorescence Microscopy of Fresh Cervical-Tissue Sections Reveals Alterations in Tissue Biochemistry with Dysplasia¶. Photochemistry and photobiology 2001;73(6):636–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ramanujam N, Richards-Kortum R, Thomsen S, Mahadevan-Jansen A, Follen M, Chance B. Low temperature fluorescence imaging of freeze-trapped human cervical tissues. Optics Express 2001;8(6):335–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chance B, Schoener B, Oshino R, Itshak F, Nakase Y. Oxidation-reduction ratio studies of mitochondria in freeze-trapped samples. NADH and flavoprotein fluorescence signals. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1979;254(11):476471. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang Z, Blessington D, Li H, et al. Redox ratio of mitochondria as an indicator for the response of photodynamic therapy. Journal of biomedical optics 2004;9(4):772–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shah AT, Heaster TM, Skala MC. Metabolic imaging of head and neck cancer organoids. PloS one 2017;12(1):e0170415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Skala MC, Riching KM, Gendron-Fitzpatrick A, et al. In vivo multiphoton microscopy of NADH and FAD redox states, fluorescence lifetimes, and cellular morphology in precancerous epithelia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2007;104(49):19494–99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pavlova I, Sokolov K, Drezek R, Malpica A, Follen M, Richards-Kortum R. Microanatomical and Biochemical Origins of Normal and Precancerous Cervical Autofluorescence Using Laser-scanning Fluorescence Confocal Microscopy¶. Photochemistry and photobiology 2003;77(5):550–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pavlova I, Williams M, El-Naggar A, Richards-Kortum R, Gillenwater A. Understanding the biological basis of autofluorescence imaging for oral cancer detection: high-resolution fluorescence microscopy in viable tissue. Clin Cancer Res 2008;14(8):2396–404 doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1609[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Poh CF, Zhang L, Anderson DW, et al. Fluorescence visualization detection of field alterations in tumor margins of oral cancer patients. Clinical Cancer Research 2006;12(22):6716–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang T-T, Chen K-C, Wong T-Y, et al. Two-channel autofluorescence analysis for oral cancer. Journal of biomedical optics 2018;24(5):051402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kanniyappan U, Prakasarao A, Dornadula K, Singaravelu G. An in vitro diagnosis of oral premalignant lesion using time-resolved fluorescence spectroscopy under UV excitation—a pilot study. Photodiagnosis and photodynamic therapy 2016;14:18–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ex vivo label-free microscopy of head and neck cancer patient tissues Multiphoton Microscopy in the Biomedical Sciences XV; 2015. International Society for Optics and Photonics. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meier JD, Xie H, Sun Y, et al. Time-resolved laser-induced fluorescence spectroscopy as a diagnostic instrument in head and neck carcinoma. Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery 2010;142(6):838–44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cheng S, Cuenca RM, Liu B, et al. Handheld multispectral fluorescence lifetime imaging system for in vivo applications. Biomedical optics express 2014;5(3):921–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Safe Use of Lasers, ANSI Z136.1–2007. In: America LIo, ed.: American National Standards Institute, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lakowicz JR. Principles of Fluorescence Spectroscopy: Springer US, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lu P, Weaver VM, Werb Z. The extracellular matrix: a dynamic niche in cancer progression. J Cell Biol 2012;196(4):395–406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Drezek RA, Sokolov KV, Utzinger U, et al. Understanding the contributions of NADH and collagen to cervical tissue fluorescence spectra: modeling, measurements, and implications. Journal of biomedical optics 2001;6(4):385–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gnanatheepam E, Kanniyappan U, Dornadula K, Prakasarao A, Singaravelu G. Synchronous luminescence spectroscopy as a tool in the discrimination and characterization of Oral Cancer tissue. Journal of fluorescence 2019;29(2):361–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sun Y, Phipps J, Elson DS, et al. Fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy: in vivo application to diagnosis of oral carcinoma. Optics letters 2009;34(13):2081–83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sethupathi R, Gurushankar K, Krishnakumar N. Optical redox ratio differentiates early tissue transformations in DMBA-induced hamster oral carcinogenesis based on autofluorescence spectroscopy coupled with multivariate analysis. Laser Physics 2016;26(11):116202 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vander Heiden MG, Cantley LC, Thompson CB. Understanding the Warburg effect: the metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. science 2009;324(5930):1029–33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kolenc OI, Quinn KP. Evaluating cell metabolism through autofluorescence imaging of NAD (P) H and FAD. Antioxidants & redox signaling 2019;30(6):875–89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Serafino MJ, Walton BL, Buja M, Adame J, Applegate BE, Jo JA. Cost-effective optical-reference-free frequency domain fluorescence lifetime imaging (FLIM) implementation using field programmable gate arrays (FPGAs) for real time acquisition and processing. SPIE Photonics West 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hinsdale T, Olsovsky C, Rico-Jimenez JJ, Maitland KC, Jo JA, Malik BH. Optically sectioned wide-field fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy enabled by structured illumination. Biomedical optics express 2017;8(3):1455–65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.