Abstract

Since the past several decades, poor water solubility of existing and new drugs in the pipeline have remained a challenging issue for the pharmaceutical industry. Literature describes several approaches to improve the overall solubility, dissolution rate, and bioavailability of drugs with poor water solubility. Moreover, the development of amorphous solid dispersion (SD) using suitable polymers and methods have gained considerable importance in the recent past. In the present review, we attempt to discuss the important and industrially scalable thermal strategies for the development of amorphous SD. These include both solvent (spray drying and fluid bed processing) and fusion (hot melt extrusion and KinetiSol®) based techniques. The current review also provides insights into the thermodynamic properties of drugs, their polymer miscibility and solubility, and their molecular dynamics to develop stable and more efficient amorphous SD.

Keywords: Amorphous solid dispersion, Hot melt extrusion, KinetiSol® technology, Spray drying, Fluid bed technology

1. Introduction

Combinatorial chemistry and high-throughput screening constitute important components of drug discovery. Studies in these areas have revealed that more than 50% of the active pharmaceutical ingredients suffer from poor aqueous solubility, a major factor responsible for their low bioavailability. Several methods have been devised to improve the solubility of active pharmaceutical ingredients, including particle size reduction, complexation, salt formation, and drug dispersion into carrier matrices, such as solid dispersion (SD) and solid solution [1].

Several drug-processing technologies have been employed to synthesize amorphous SDs, such as hot melt extrusion (HME), Kinetisol®, spray drying, supercritical fluid technology, and electrostatic spinning [2–5]. The selection of these methods depends on the nature of the end product. For example, HME has recently emerged as the method of choice for the development of SDs, owing to its several advantages over other techniques. Poorly water-soluble drugs can be formulated through the HME technology as one of the advantages of this technique is that it can eliminate the use of solvents. But as compounds must be thermally stable to be used in the HME process, Kinetisol® on the other hand has been specifically developed for compounds that are thermal sensitive. Supercritical technology and electrostatic spinning methods are still to be established as robust, reproducible, and scalable techniques. Spray drying can be considered the method of choice for both the in discovery and the developmental stages as the process can work both on the bench top mode and on a commercial production scale [6].

The main objective of the present review is to discuss several thermal-based pharmaceutical techniques used to synthesize amorphous SDs (ASDs). For selection of a suitable processing technique, the physicochemical properties of the API and its suitability for an ASD are first evaluated. This is followed by assessing how the carrier would stabilize the amorphous API during storage as well as during the drug dissolution and absorption in the gastrointestinal tract. In addition, other steps, such as screening and selection of the polymer matrix and optimization of percentage drug loading, are evaluated for the development of ASDs. Challenges faced during the evaluation of in-vitro and in-vivo correlations for enhancing bioavailability of the product should also be considered and suitable changes in the applied approach should be introduced from the discovery to the developmental stage to generate an efficient product.

Physical stability of the system to tolerate adverse conditions such as high humidity and temperature depends on good miscibility and strong molecular interactions between the drug and the polymer. Solubility can be described as an equilibrium thermodynamic parameter, characterized by a state wherein the chemical potential of the solute matches that of the liquid (solution) phase.

Some of the traditional methods used to determine the drug–polymer solubility and miscibility are the Fox–Gordon equation and the Flory–Huggins (F–H) theory [7–9]. However, recent improvements in the field of molecular dynamics have proven to be efficient predictors of solubility and miscibility of the drug and the polymer. These methods along with their applications will be briefly discussed in this section [10]. The F–H interaction, a well-known, lattice-based theory, is obtained by the following equation:

| (1) |

where, Ф drug is the volume fraction of the drug, mdrug is the ratio of the volume of the drug to the lattice site, Фpolymer is the volume fraction of the polymer, mpolymer is the ratio of the volume of the polymer to the lattice site, and χ is the F–H interaction parameter, representing the difference between the drug–polymer, the drug–drug, and the polymer–polymer interactions. When the drug–polymer interaction is greater than the sum of drug–drug and polymer–polymer interactions, the value of χ will be negative, indicating mixing between the drug and the polymer.

Fox and Gordon–Taylor equations have also been used in determining the glass transition temperature (Tg) of SDs, with small positive or negative deviations due to drug–polymer interactions.

Experimentally determining the solubility of a drug in a polymer is considerably challenging. However, drug–polymer miscibility can be qualitatively estimated using the solubility parameter approach. The solubility parameter is equal to the square root of the cohesive energy density (CED) and is defined by the following equation:

| (2) |

where, δ is the Fedor solubility parameter, CED is the cohesive energy density, ΔEv is the energy of vaporization, and Vm is the molar volume. Hoftyzer and Van Krevelen methods have been used for better predictions of interactions and are depicted by the following equations:

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

where, δd, δp, and δh are the contributions from the dispersive forces, polar forces, and hydrogen bonding, respectively, d is the total solubility parameter, Fdi is the molar attraction constant due to dispersive component, Fpi is the molar attraction constant due to polar component, Ehi is the hydrogen bonding energy, and V is the molar volume. Systems with δd < 7.0 MPa1/2 are found to be miscible, whereas those with δd > 10.0 MPa1/2 are likely to be immiscible. A limitation of this method is that it can yield erroneous results if drug–polymer mixtures form H-bond interactions. Hydrogen bonds are suitable for those drug–polymer systems that are primarily characterized by van der Waals interactions (dipole–dipole and dispersion forces) [11–13].

The solubility of a drug in a polymer can be extrapolated from the plot of enthalpy versus drug–polymer concentrations. This can be experimentally measured using the hyper Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) analysis technique to calculate the melting enthalpy of a crystalline drug in a polymeric matrix. It is based on the concept that only the fraction of drug that is undissolved in the polymer will result in a melting endotherm, with the fraction dissolving in the polymer making no contribution to the endotherm. The solubility of the drug in selected polymers could be estimated from the plot of the melting enthalpies of a series of drug concentrations in different drug–polymer mixtures and extrapolating the drug concentrations to zero enthalpy [14].

1.1. In-silico methods

With recent developments in the field of computational science, molecular dynamics has increasingly gained importance. Molecular dynamics simulation studies can provide a deeper understanding of the mechanisms and the intermolecular energy contributions, thereby accelerating the development of more stable amorphous formulations.

The solubility parameters for the drug and the polymer can be estimated from group contribution methods. These methods have been included in some commercial prediction tools such as the MemFis® software to allow for in-silico polymer screening. However, the accuracy of such prediction tools needs to be experimentally verified, especially in cases where other interactions can exist such as API-polymer interactions which are stronger than the Van der Waals forces.

With recent computational advances in atomistic and molecular simulations, these have proved to be powerful tools to probe the molecular dynamics of different systems to predict the thermodynamic behavior of amorphous SDs that have not been well characterized experimentally. In-silico predictive tools, such as GROMACS all-atom field package, Monte Carlo simulations, SYBYL/MMFF94 force field measurement, and Gaussian 09 software using density functional theory have been successfully used in polymeric amorphous solid dispersion systems (PASDs) to understand glass transition, crystallization tendency, and drug–polymer interaction and stability. These simulation tools in combination with the F–H theory have also been utilized to predict the solubility of a drug in a lipid carrier. In addition, condensed-phase optimized molecular potentials for atomistic simulation studies (COMPASS) force field can predict the solubility parameter for drug–polymer systems. Moreover, the density functional theory using B3LYP exchange correlation function efficiently predicts drug–polymer interactions. Literature reports in-silico-based molecular modeling to be a powerful preformulation tool that has allowed formulation scientists to rationally select polymers for developing PASDs [15–18].

Pajula et al. [19] applied the F–H theory along with computational methods to small molecule mixtures to observe their phase stability. The authors used the Materials Studio Blends module (Accelrys Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) along with COMPASS force field to determine the F–H interaction parameters. The energy of mixing was calculated using the following equation:

| (7) |

where, Z is a coordination number, E is the binding energy, and s and b are the base and screen molecules, respectively. The energy of mixing is used to determine the interaction parameter. The phase stability diagram demonstrated that a phase separation would occur, and the binary mixture would be unstable in the inner portion of the curves as compared to the exterior portion. To verify the results obtained from the computational method, hot stage and polarized light microscopy experiments were performed. The authors concluded that the F–H interaction parameter could predict the stability of small molecule mixtures. Moreover, it could select possible stabilizers required to formulate a stable amorphous binary mixture.

Table 1 lists the solubility parameters of some of the commonly used drugs and polymers that are calculated using the Van Krevelen method [8,20–24].

Table 1.

Solubility parameter values of commonly explored polymers and few APIs calculated using the Van Krevelen/Hoftyzer Equation (Eqn. (3)) [8,20–24].

| Polymer | Solubility Parameter (MPa1/2) |

| Eudragit EPO | 19.6 |

| Eudragit L100 | 22.75 |

| Eudragit L100–55 | 21.65 |

| PEG 8 | 21.6 |

| PEG 10 | 21.5 |

| PEG 1500 | 21.4 |

| PEG 8000 | 21.7 |

| PVP 12 | 22.4 |

| PVP 30 | 22.4 |

| PVP K90 | 21.3 |

| PVP/VA | 21.5 |

| PVA | 31.7 |

| Kollidon 12 PF | 19.4 |

| Kollidon 17 PF | 19.4 |

| Kollidon 30 | 19.4 |

| Kollidon 90 F | 19.4 |

| Kollidon SR | 20.2 |

| Kollidon VA 64 | 19.7 |

| Kollicoat IR | 32.5 |

| Kollicoat MAE 100 P | 21.4 |

| Kollicoat Protect | 34 |

| Kolliphor P188 | 20.3 |

| Kolliphor P407 | 20.1 |

| HPC | 31.5 |

| HPMC E5 | 28.1 |

| HPMCAS | 29.17 |

| HPMCAS LF | 29.1 |

| HPMCAS MF | 29.1 |

| Pharmacoat 603 | 23.7 |

| Soluplus | 19.4 |

| Drug | Solubility Parameter (MPa1/2) |

| Azithromycin | 21.31 |

| Carbamazepine | 27 |

| Curcumin | 19.2 |

| Diphenhydramine HCl | 17.75 |

| Fenofibrate | 21.4 |

| Griseofulvin | 24.5 |

| Indomethacin | 22.3 |

| Itraconazole | 22.6 |

| Lacidipine | 20.1 |

| Propranolol HCl | 21.94 |

2. Strategies to develop amorphous solid dispersion

Several techniques are currently employed to generate SDs and these are based on different mechanisms. The quality of the final product is influenced by various factors, such as the basic principle involved in the technology, suitability of the technology, types of formulations, processing window, and practical problems involved in the process. Processes, such as HME, involve elevated thermal conditions. On the other hand, KinetiSol® utilizes mechanical shear to achieve the required heat energy for the process, whereas spray drying and fluid bed processing involve the evaporation of solvent from the liquid solution or dispersion. Thus, every process has its unique advantages and limitations based on which the process for a formulation is selected. This selection is one of the critical issues to be considered before starting any process. In the present review, we have attempted to discuss important thermal strategies involved in developing ASDs.

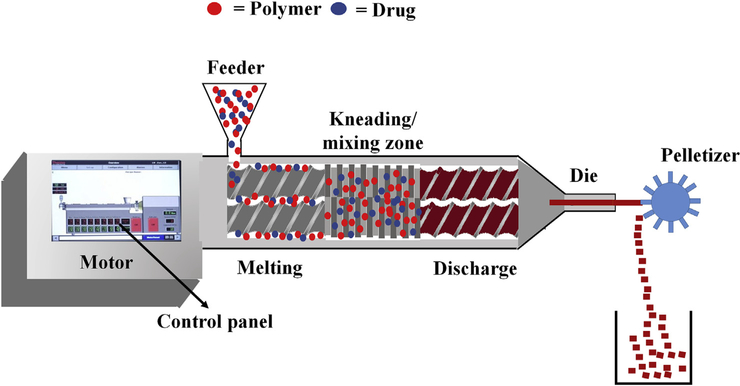

2.1. Hot melt extrusion

Hot melt extrusion is one of the most efficient technologies to synthesize SDs. In this process, the API and the polymer matrix are blended together to generate a physical mixture that can be extruded under certain specific conditions [25,26]. Processing parameters, such as feed rate, shear force, temperature, die geometry, barrel design, and screw speed, should be considered while employing this method, as these contribute significantly to the quality of the final product. HME offers several advantages over other conventional methods, such as, it is a one-step, solvent-free, continuous operation with fewer processing steps. Moreover, it requires no compression and can improve the bioavailability by dispersing the drug at the molecular level. However, certain limitations that could restrict its use in the pharmaceutical industry include the requirement of a higher energy input as compared to other techniques and possible exclusion of some thermo-labile compounds due to high-processing temperatures involved [27,28]. Nevertheless, this technology has gained popularity, which is evident from an increasing number of patents issued, commercial pharmaceutical products, and available research articles. It has been successfully employed to synthesize several pharmaceutical drug delivery systems, such as pellets [29], granules [30], immediate and modified release tablets [31], taste-masked oral fast dissolving systems [32], transdermal and topical delivery systems [33,34], transbuccal and transungual delivery systems [35,36], solid lipid nanoparticle systems [37,38], nanocrystals [39,40], and floating drug delivery systems [41,42]. The schematic illustration of HME process is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

The schematic illustration of Hot Melt Extrusion process.

2.1.1. Hot melt extruder

An extruder consists of a feeder, barrel with screws or ram, control panel, torque sensors, and a heating/cooling device with dies. On-line and in-line quality control analyses using near-infrared probe and other well-known analyses, such as Raman, ultrasonic, and dielectric spectroscopy, can be easily adapted with the HME process [43]. Pharmaceutical screw extruders are designed based on the regulatory guidelines to produce desired extrudates. There are mainly three types of extruders: single-screw extruder, twin-screw extruder, and multiple screw extruder. Among these, twin-screw extruders have been widely used in pharmaceutical research and industry. There are two types of twin screw extruders: one is a high-speed energy input twin-screw extruder that is mainly used for compounding, reactive processing, and/or de-volatilization. The second one is a low-speed, late fusion twin-screw extruder that is designed to mix at low shear conditions and pump at uniform pressures. Twin-screw extruders have several advantages over the single-screw extruders including overcoming formulation mixing problems and providing complete mixing of the components. The two screws can be oriented in several configurations depending on the desired level of shear and speed of operation. These configuration settings can play a significant role in addressing formulation-related issues. Morott et al. [44] reported screw configurations to be a dependent parameter that influences the efficiency and stability of some taste-masked formulations. Using a specific screw configuration, the group demonstrated that crystallinity of sildenafil citrate could be preserved with successfully processed formulations. In addition, Teixeira et al. [45] investigated algorithmic tools that are effective and employed by the pharmaceutical industry. They also determined appropriate screw configurations for specific purposes. Depending on the required intensity of mixing, the two screws can be designed to rotate in the same direction (co-rotating) or in the opposite direction (counter-rotating). The counter-rotating designs are utilized when very high shear regions are required as they expose materials to very high shear forces. However, co-rotating screws are mainly used in the pharmaceutical manufacturing [27].

2.1.2. Downstream processing

Several formulations can be processed using melt extrusion technology. Scientists may opt for a variety of die shapes and sizes. For example, flat dies are used for the production of films [33,46,47] and patches [48], whereas circular dies are used for pelletization and spheronization [29,49,50]. The molten drug–polymer mixture can also be filled into molds using injection molding. For instance, these molds can be formed to yield the tablet, capsule shapes, ear inserts, or pediatric formulations [26,51]. Some of the dosage forms that have been previously studied include rods, films [33], spherical pellets [29,50], punched and injection molded tablets [52–54], and granules [54,55].

2.1.3. Hot melt extrusion processing parameters

The HME process can be theoretically divided into five steps: i) feeding, ii) melting and plasticizing, iii) conveying and mixing, iv) venting, and v) stripping and downstream processing. Each step may affect the characteristic properties of the final extrudate, and these properties could create problems during the process, which would have to be taken care of during the optimization stage. The material to be extruded is introduced into the feeder section of the extruder via a hopper. It is essential that the angle of the feed hopper always exceeds the angle of repose of the feed material to ensure a good flow of the feedstock else the material tends to form a solid bridge at the neck of the hopper, resulting in changeable flow. However, to address this issue, a force-feeding device, such as a mass flow feeder or side stuffer, could be used to run the feedstock onto the rotating screw. Mixing is a potential factor affecting the HME process and is classified as distributive mixing and dispersive mixing. In addition, the screw speed and the feed rate are also related to shear stress, shear rate, and mean residence time which affects the dissolution rate and stability of the final product [27,49,55].

2.1.4. Screw design and configuration

The screw design and configuration significantly impact the process of the SD formulation. Thus, these are usually optimized to meet specific requirements, such as high or low shear. Screws are designed with several sections, whose function range from feeding to metering. To improve the melting process and mass flow through the extruder, screw design is sometimes modulated [44]. The efficiency of the melting process is highly affected by the polymer properties and the extruder design. However, limited literature is available on the effects of screw design and configuration on HME processing. Nakamichi et al. [56] demonstrated that kneading paddle elements played an important role in changing the crystallinity and dissolution properties of a kneaded nifedipine–hydroxypropyl methylcellulose phthalate mixture. Similarly, Verhoeven et al. [57] described that the distribution homogeneity and release rate of metoprolol tartrate in ethyl cellulose mini-matrices were not significantly affected by the number of kneading mixing zones or their positions along the extruder barrel and that at least one kneading zone was required for homogenous distribution of the components within the formulation. Liu et al. [58] studied the effects of screw configuration on the dissolution behavior of indomethacin in Eudragit EPO melt extrudates. They identified that the kneading blocks accelerated the complete dissolution of indomethacin into the polymer melt. Thus, it is evident from these studies that the HME processing parameters play an important role in determining the properties of extrudates.

2.1.5. Process analytical technology and scale-up issues

Process analytical technology (PAT) is a useful analytical tool to monitor and characterize melt extrusion and chemical composition of the products in-line to ensure the final product displays the desired attributes. It can determine flow properties, polymer structures, drug-polymer interactions, and concentrations of drugs and additives immediately downstream of the extrusion process [43]. Scaling up in HME like other manufacturing technologies is an important subject of discussion. To scale up, the aspect of autogenous extrusion is crucial since the ratio of surface to volume becomes more unfavorable with increasing extruder size, especially if the process has not been developed to run autogenously on a small scale. Increasing the size of the extruder is associated with variation in the ratio of surface to volume which can be a problem. Since the extruder is deliberated to be a closed system such as a pipe, with force being conveyed by the extruder screw, the mean residence time can be as short as less than 30 s. The impact of process parameters on the residence time and torque for each formulation should be known to the respective extruder. This would allow for a better comparison and understanding of the correlation [59].

2.1.6. Co-extrusion process

Co-extrusion refers to the extrusion of two or more materials through a single die with two or more orifices arranged so that extrudates merge and join into a laminar structure before the chilling. The process solves the issues related with material that is impaired by an individual extruded polymer layer. The physical mixture is fed through the hopper into the extruder (separately); however, the orifices are arranged in a manner that the material would be extruded through a common die, thus creating a bilayer [60] or a multilayer product [61,62]. For example, Iosio et al. [60] prepared a bilayer product that composed of microcrystalline cellulose, lactose, and water wetted with the self-emulsifying system. A multilayer product would consist of the final product in the form of a laminar structure with multiple layers. The principle of co-extrusion appears as a promising strategy for several novel dosage forms, including oral and transdermal drug delivery systems and implants [49,63–68].

2.1.7. Use of plasticizers as processing aids

The addition of a plasticizer into formulations aids in improving the processing conditions during the manufacturing. It may also improve the physical and mechanical properties of the final product. Some examples of commonly used plasticizers are triacetin, citrate esters, D-α-tocopheryl, and surfactants. The injection of pressurized CO2 while processing showed a reduction in processing temperatures of a variety of polymers. In addition, pressurized CO2 acts as a foaming agent [69]. It has also been shown that CO2 acts as a plasticizer for polyvinyl pyrrolidone (PVP)-VA-64, Eudragit® E100, and Ethocel™ (EC) 20 cps [70]. Additionally, several drugs have been reported to function as plasticizers in melt extruded dosage forms. For example, Repka et al. [33] studied the effect of chlorpheniramine maleate and hydrocortisone as plasticizers for hydroxypropyl cellulose films. These two APIs (1% w/w) exhibited a plasticizing property on the specific polymer. In addition, they provided mechanical stability to the films. Ibuprofen has also been used in HME as a plasticizer in some formulations [71]. Surfactant such as vitamin E D-α-tocopheryl polyethylene glycol 1000 succinate (TPGS) has been utilized as an excellent processing aid in developing plasticized matrices [72]. Employing this technique gave a broader flexibility to films.

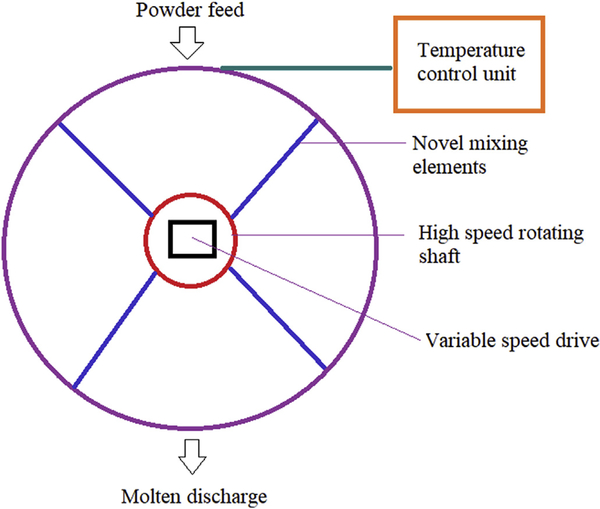

2.2. KinetiSol® technology

KinetiSol® is a novel, high shear technology adapted from the plastic industry that operates on the fusion principle to prepare ASDs. This technique involves a novel combinatory principle of shear force and friction for rapid transformation of the blend into a molten state to produce a homogenous SD [73]. Fig. 2 depicts the schematic representation of KinetiSol® technology. The collective mechanical force involved in the technology causes a rapid increase in temperature to produce a molten mass that would be quenched for further processing. The collective mechanical force comes from the thermal process in which heat is generated by a series of paddles rotating in a cylindrical chamber and shaft with mixing blades rotating at a high speed that will eventually produce a great amount of frictional energy through the impact made with the particles [74]. The rise in temperature occurs without any external application of heat energy. The entire process takes less than 30 s [75]. This additive effect of shear force with friction and without any external heat makes this technology feasible to viscous polymers (such as PVP K30, PVP K90, and HPMC K15 M) and drugs with a high melting point (a high melting point will require higher thermal energy which may result in a higher degradation potential of the formulation), suitable for APIs with low solubility in organic solvents, eliminate plasticizers, and reduce the danger of prolonged exposure to elevated temperatures [76].

Fig. 2.

The schematic representation of process in KinetiSol® technology.

This technology can be applied to batches ranging from small scale research and development (R&D) in a batch mode operation to commercial scale in a semi-continuous mode operation [77]. Moreover, it is a fast process in which temperature increase is achieved within seconds and the material is ejected when the target temperature is reached. Less exposure time means less exposure of the material to a lower range of thermal stress, which is the most important factor with respect to stability of the product. Another advantage of the KinetiSol® technique is that it allows for a high drug/polymer loading without high torque loads and offers least possible degradation in comparison to other thermal processes [73]. Hughey et al. [76] processed itraconazole with Methocel E50LV at a 1:1 to 1:9 drug/polymer ratio and at a temperature range below the melting point of itraconazole, without the use of much shear. These conditions restored the chemical nature of the polymer and maintained assay uniformity, suggesting the consistency of this process. Moreover, this technique allows the thermal processing of methacrylic acid-derived polymers, such as Eudragit L100–55 without the aid of a plasticizer. Tg of the solid dispersion of itraconazole and Eudragit L100–55 (at 1:2 ratio) was 101 °C, which was higher than the dispersion developed using other thermal techniques, indicating an increased shelf life. Short processing time (less than 10 s), a temperature well below the degradation temperature of Eudragit L100–55 (155 °C), and ease of processing without the use of high torque prove this technique to be highly efficient [73].

Another edge that the KinetiSol® technology has over other techniques is it allows processing at the lowest possible temperature and with minimum residence time. This helps to preserve the stability of the formulations. An example of this is a hydrocortisone dispersion with hydroxypropyl methyl cellulose (HPMC) E3 and PVP VA64, wherein the process was performed at 160 °C and for less than 30 s, thereby preserving its assay in comparison to processing the mixture at higher temperatures [78]. LaFountaine et al. [77] demonstrated good processing capability of this technique in terms of torque and dispersion in griseofulvin SDs without any signs of crystallinity and rise in impurity levels after exposure to open conditions at 40 °C and 43% relative humidity (RH) for 6 months.

Although the processing time of this technique is considerably less as compared to other thermal techniques, the formulator should carefully consider the processing parameters to obtain a stable product. Hughey et al. [76] formulated an ASD of meloxicam with Soluplus® using the KinetiSol® technique where in a design of the experiment study was conducted to observe the effect of process variables on the drug’s stability. The process was performed at a temperature range of 110–140 °C and at different processing speeds ranging from 2250 to 3000 rpm. The results obtained revealed a relation between the process speed, ejection temperature, and the residence time. Residence time was inversely related to process speed; the residence time reduced from 22 s to less than 3 s when the process speed was increased from 2250 to 3000 rpm. As the required temperature was attained, the material was ejected out, facilitating minimum exposure to higher temperatures. No definite relation was observed between the processing speed and degradation of the API. However, temperature of ejection and degradation were found to be related. The samples ejected at 110 °C and 118 °C showed an assay value above 95%; however, it dropped to below 90% when ejection temperature was raised above 125 °C and further decreased to 79% when the ejection temperature was raised to 140 °C. These results confirmed that the degradation started between 118 °C and 125 °C, indicating that bracketing the safe processing conditions is crucial for the stability of formulations. The SDs prepared exhibited a significant improvement in dissolution (~7 folds) in 0.1 N HCl and deionized water. LaFountaine et al. [75] reported different effects of processing conditions on the stability of ritonavir SDs that were prepared using PVA 4–88 and PVP VA64. The process was performed at different processing speeds of 1000, 1500, and 2000 rpm. With additional input of the mechanical energy (processing speed), the process time was reduced but the impurity content increased, suggesting that the mechanical energy above a certain limit led to degradation of the drug. Even though the ejection temperature ranged from 80 to 100 °C, which was considerably lower than the degradation temperature (160 °C), the API degradation was observed at a higher process speed of 2000 rpm. The placebo batch was also processed to confirm that the degraded product was the API. This emphasizes the importance of processing conditions, as the mechanical energy supplied along with the increase in temperature might be degrading the API or a combination of the API and the polymer which would suggest that the process needs to be monitored carefully based on the type of material used to develop a stable product.

Above case studies emphasize the potential of KinetiSol® in producing ASDs with suitable monitoring of processing conditions. However, large-scale operations of this technology still need to be established in the pharmaceutical industry.

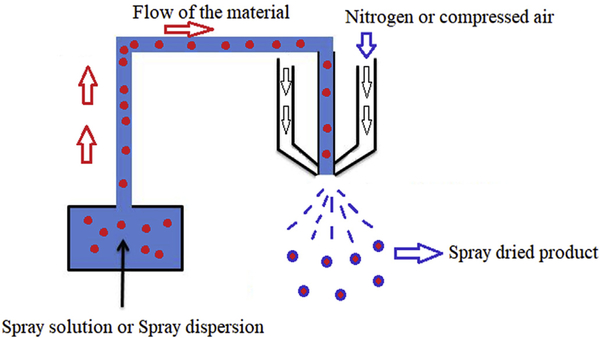

2.3. Spray drying

Spray drying is a well-focused technology in the pharmaceutical industry and is utilized in several operations ranging from simple drying to encapsulation processing bulk APIs and excipients and developing ASDs of poorly soluble drugs [79].

Literature reports spray drying to comprise four fundamental stages:

Atomization of liquid

Interaction between liquid and drying gas

Evaporation of liquid from the mixture

Isolation of dried particles from drying gas

Other factors that affect the spray pattern are the density of the drying gas, the amount of solid content in the liquid spray (which would affect the viscosity of the liquid), and the surface tension of the liquid [3]. The schematic representation of basic spray drying process is shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

The diagram depicting basic processing steps in spray drying process.

2.3.1. Factors affecting spray drying process

2.3.1.1. Role of solvent system

The role of the solvent system is to solubilize the ingredients to be sprayed, thereby enhancing spray drying. The selection of an appropriate solvent system is significant as it could affect the precipitation of ingredients from the solvent, physical and chemical characteristics, process of formation of the SD, and drug release pattern.

Some of the major criteria in selecting an efficient solvent system are good solubility of API and polymer, non-combustibility, low toxicity and viscosity, chemical compatibility with feed components, and ease of evaporation [80].

While selecting a solvent, its physicochemical properties, along with the feed ingredients it would carry, are crucial. The Kamlet–Taft parameter provides an estimate of the probable strength of H-bonding in the feed solution along with H-bond donor and acceptor pairs. Solvents with greater H-bond donor activity form stronger bonds with H-bond acceptor groups of the polymer or the drug and vice versa [81].

The solubility of an API in the selected solvent system plays an important role because poor/partial solubility of the API may lead to its non-homogenous distribution in the SD. This, in turn, could affect the drug release pattern from the dosage form since the improper distribution will not be the exact representation of the molecular level dispersion between the API and the polymer [82]. Kadota et al. [83] studied the effect of the solvent system on the composite particles of hydrophilic and hydrophobic drugs using highly branched cyclodextrins (HBCDs). The solvent system consisted of a mixture of water and ethanol. When the ethanol content was above 35%, HBCD precipitated, causing nucleation and crystal growth. The solubility of the polymer in a certain solvent system and the difference in aqueous solubility of APIs affected the drug–polymer interactions, which was reflected in the particle size and drug content of the SD.

Peclet number (Pe) could provide an idea about the formation of the particle and its distribution and is depicted by the following equation:

where, K is the evaporation rate and Di is the diffusion coefficient of the solute.

The distribution and nature of dispersion formed highly depend on the type of solvent selected, distribution coefficient of the solutes in the solvents, the process variable, and the rate of evaporation [84].

Agrawal et al. [3] formulated SDs of compound X with PVP VA64 using HME and spray drying technique. The two types of dispersion exhibited no difference in the crystallization as they both had a single Tg value. The DSC results were supported by those obtained from X-ray diffraction (XRD), indicating an amorphous nature of the dispersion. The scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis demonstrated that the spray-dried particles (50–300 μm) had a smooth surface in comparison to the HME dispersion particles (60–240 μm), which were irregular with angular surfaces. A 3-month stability study at 50 °C and 51% RH showed signs of crystal growth in the spray-dried product, whereas stability of the HME product could be attributed to the higher surface area of spray-dried particles (22 folds).

2.3.1.2. Components of feed solution

Feed solution comprises ingredients such as API, polymer, and other additives required to form a SD. Components with lower solubility will dry at a faster rate than those having a good solubility, which would cause precipitation on the droplet surfaces [85,86]. Higher viscosity of the feed solution would cause sticking of the droplets on the inside of the drying chamber, which would affect the feasibility of the process, thereby resulting in low yield values [87]. An example of this was the yield results obtained due to spray-drying a high viscosity maltodextrin solution formulated by Tonon et al. [88].

2.3.1.3. Effect of drying

The morphology and physical nature of the spray-dried particle are also affected by the mode of drying. Rapid evaporation of solvent from the droplet leads to recrystallization of the ingredients (“Rush hour effect” or rapid mixing of ingredients in the droplet without providing them sufficient time to reorganize themselves into a proper structure. In the Rush hour phenomenon, if the film formed after drying is permeable, it forms a porous particle. If the polymeric layer formed is impermeable, it entraps the solvent, resulting in a hollow particle. The “Tetris effect” is the phenomenon that occurs at a slower rate of evaporation, providing enough time for molecular rearrangement, causing phase separation, and sometimes initiating crystallization as well. In this phenomenon, the particle formed may be homogenous or affected by the phase separation based on the strength of the drug-polymer interactions [89].

Inlet and outlet temperatures are vital factors in the spray drying process because the process temperature ranges are directly related to the thermal properties of the drug/polymer. Selection of the temperature inputs should be based on the physical and chemical stability of the ingredients. In preparation of cefditoren pivoxil SDs, products were prepared at high and low inlet temperatures. The product processed at a lower Tg recrystallized and displayed affinity for moisture, whereas the product processed at a higher Tg exhibited lower moisture uptake at elevated RH conditions [90].

2.3.1.4. Critical formulation factors

The nature of the polymer and the drug also affect the physical state of the final product and its dissolution. The morphology of the spray-dried particle and its release profile are directly related to the degree of crystallinity of the drug in dispersion, native pore size, entrapment efficiency of the polymer, and the porous nature of channels in the final product. For example, in ibuprofen co-spray dried products of mesoporous silica carriers (at 1:1 ratio of w/w) formulated by Shen et al. [91], it is evident that the drug release is not only dependent on the morphology of the polymer, but also on the extent of the amorphous conversion of drug entrapped inside the polymer. Spray-dried dispersion of ibuprofen was prepared using MCM-41 (surface functionalized mesoporous silica), SBA-15 (carboxy-modified mesoporous silica; pore size < 10 nm), and SBA-15-LP (pore size > 20 nm). The SEM images confirmed the drug to be completely entrapped inside the polymer in case of MCM-41 and SBA-15 dispersion, whereas both crystalline and amorphous forms of the API were present in the SBA-15-LP dispersion. These results were also supported by those obtained from XRD. The dissolution achieved in the case of MCM-41 and SBA-15 dispersion was 95 and 88%, respectively. This could be explained by the larger pore size of SBA-15 (6 nm) than that of MCM-41 (2.3 nm). However, despite having a pore size greater than that of both other carriers, SBA-15-LP displayed only 76% drug release. This could be attributed to the crystalline form of the drug present in the SBA-15-LP dispersion, which was the sole critical factor over the pore size and channel length.

Spray drying technology can also be extended to polymers selected for the HME process. The mode of interaction between the polymer, drug and different solvents also affect the quality and characteristics of the process. Garekani et al. [92] prepared spray-dried dispersion of theophylline with Eudragit RS (in the ratios of 1:1 to 1:3 of drug and polymer) in the presence of aqueous and organic phases (SPD aq. and SPD org.). The polymer used for the aqueous dispersion was Eudragit RS30 and that used for the organic dispersion was a solution of Eudragit RSPO in ethanol. DSC studies demonstrated that the drug preserved its crystalline form and remained stable in all dispersions prepared. The SEM images revealed the morphology of SPD aq. to consist of drug particles distributed on the outer surface of the polymer, whereas the SPD org. exhibited complete miscibility of the polymer with the drug. This results from variations seen in the interactions between the drug and the polymer in the presence of the solvent, which differed in its solubility for the polymer. This effect was evident in the dissolution results, where the SPD aq. was less efficient in sustaining the drug release in the aqueous medium as compared to the drug from the SPD org. product.

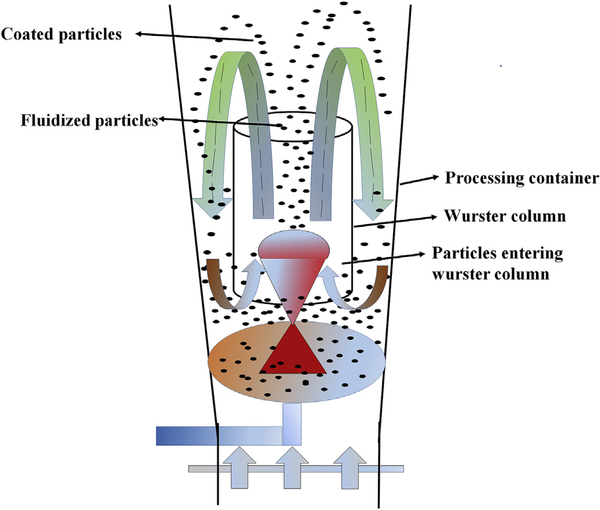

2.4. Fluid bed technology

Fluid bed technology is based on the principle of air suspension, where hot air is passed at a high pressure through the air distribution plate/bottom of a container onto the beds of the solid particles, thereby suspending these in an air stream, also known as a fluidized state. Taking into account the efficient contact present between the solid and gas phases in this process, this technology is widely used in the chemical industry, food industry, pharmaceutical industry, and thermal power generators [93–95]. Fluid bed technology is applied in several ways in the pharmaceutical industry for different manufacturing purposes, such as granulation (fluidized bed granulator), coating (fluidized bed coater), drying (fluidized bed dryer), cooling, agglomeration, and layering of particulate matter [96–98]. The fluidization process in this fluid bed technology is depicted in Fig. 4. Depending on the position of the nozzle, these are classified into four different types, namely top spray, bottom spray, Wurster type, and rotor with side spray (tangential spray) [99].

Fig. 4.

Illustration of fluidization process in fluid bed technology.

Several techniques have been reported for synthesizing ASDs; however, only a few methods are suitable for large/industrial scale processes. HME and spray drying are the most suitable strategies for manufacturing on an industrial scale, whereas the fluid bed layering process has limited use owing to certain disadvantages, such as poor/partial and slow rates of conversion. Despite the drawbacks, a few marketed products are still manufactured using the fluid bed process [100]. Typical applications of this process include granulation and taste masking (to improve flow and modify the release of the drug respectively), production of multiunit particulate systems, and layering of drugs onto a core material for synthesizing ASDs [101].

2.4.1. Types of fluid bed processes

Based on the configuration, fluid beds are either i) top spray, ii) bottom spray, or iii) tangential spray (rotor or centrifugal spray) [101]. The top spray process consists of a perforated distributor plate with a wired mesh at the bottom, through which the air is supplied onto the bed with the spray nozzle present at the top. In the fluid bed granulation process, agglomeration is achieved by spraying the binder solution. With the agitation forces ensuring continuous collision of the particles, agglomerates are formed. (drying can be achieved by agitating the bed with hot air without the addition of any binder solution). The sudden rise in the outlet temperature and an equalization of dew in the inlet and outlet air is an indication of the end of the drying process. This process can also be used for coating; however, it would be a lengthy process owing to the random movement of particles and the varying distance between the particles and the spraying devices in the bed. Bottom spray or concurrent fluid bed processes differ from the top spray process, in terms of position of the spray devices that are directed upward and positioned on the distributor plate. Therefore, the direction of spray and air distribution is the same. In this process, the distance between the spray devices and cores is short, and the movement of the particles is well controlled. In contrast, the tangential spray process has a rotating distributor plate and an air flow. The distance between the cores and spray device is short with well-defined movement with this type of spray process. The drying air and the spray liquid follow the same direction. Uniform coating can be achieved with the bottom and tangential spray which are also less sensitive to the changes in pressure, thereby making them more suitable for scale up processes [101].

2.4.2. Typical process parameters in fluid bed process

Air velocities and properties of the particles, such as the size and density of particles, determine the fluidization velocity required to obtain a homogenous bed. Parameters that affect the quality of the fluid bed product are formulation parameters (particle size distribution, material, binder/coating solution concentration, the solvents used in the coating/granulation process), process parameters (fluidization temperature, velocity and humidity, spray rate and nozzle type, spray angle, batch size and size of the droplet) and apparatus parameters (spray type (top/bottom/Wurster), fluid bed vessel dimensions, height and position of nozzle dimensions of air distribution plate [102,103]. Particle size significantly affects the fluidization process. Geldart [104] classified the particles based on their particle size and fluidization behavior. Powders with mean particle size distribution (dp) less than 100 μm are cohesive and difficult to fluidize, whereas those in 100–1000 μm fluidize well. Larger particles (> 1000 μm) are difficult to fluidize; hence, these require special fluid beds that can provide high air flow for fluidization.

2.4.3. Factors influencing the quality of applied layers

Some of the general fluid bed processing considerations that can significantly affect the quality or property of the applied layers are listed below:

Heat and mass transfer

Substrate flow

Droplet size

Liquid properties

Droplet size is regulated by several factors including solvent properties, such as viscosity and surface tension, atomizing air pressure and volume, and liquid spray rate. High atomizing air pressure and volume can be used to achieve smaller droplet size, which, in turn, is required for coating smaller particles to avoid or minimize agglomeration. Liquid properties, such as viscosity and surface tension, impact the product performance. A liquid with low surface tension value can be atomized at low atomizing air pressure and volume. In contrast, liquids with viscosity values up to 250 cp require pneumatic nozzles to be atomized. However, liquids with very high viscosity values have drawbacks such as spreadability and poor quality of the film coating [101].

2.4.4. Solid dispersion production using fluid bed layering

Beside granulation and coating, fluid bed layering is used in synthesizing SDs and multiple unit particulate systems (MUPS) [105]. Although, SD is one of the widely used formulation techniques to improve solubility and achieve fast release rates of poorly soluble drugs. SDs suffer from stability issues such as phase separation and crystallization. Ayenew et al. [106] reported the phase separation during the compression of naproxen - PVP SD powder. Coating SDs onto inert cores is one alternative to prevent additional downstream processing steps [106,107]. Moreover, coated pellets have other benefits compared to the tablets, such as even distribution in the gastrointestinal tract, a smaller number of variations in gastric emptying rates, reduced risk of dose dumping, and additional functional coating that improves the stability of the amorphous material [107,108]. In this method, the API/polymer solutions are sprayed onto the excipients or sugar spheres in a fluid bed granulator/coater such that solvent removal and deposition of SDs occur simultaneously [109].

Beten et al. [110] successfully prepared controlled release pellets and co-evaporates of dipyridamole using the bottom spray fluid bed processing unit. To achieve controlled release, enteric acrylic polymers, such as Eudragit® L100–55, L, and S, were dispersed at different proportions in an organic solvent mixture (ethanol/dichloromethane in a 1:1 ratio) and sprayed onto the neutral pellets. The drug, which is present in an amorphous state within the pellets, was released at a controlled rate from the pellets as well as the co-evaporates. In addition, the release rate was influenced by the particle size of the pellet and the co-evaporate. Ho et al. [111] prepared SDs of nifedipine in HPMC on sugar spheres using the fluid bed coating system. Acetone: water mixture in 7:3 ratios was selected as a spraying solvent. HPMC and nifedipine SDs were prepared in a 1:1 and 1:3 ratios, respectively. It was concluded that the 1:3 ratio led to an improvement in the solubility. Sun et al. [112] demonstrated the application of fluid bed coating for preparing SDs of silymarin with PVP using a single-step, fluid bed technique. Silymarin and PVP were dissolved in ethyl alcohol and then sprayed onto non-pareil cores in a dry air flow Mini-Glatt fluid bed system. The drug to polymer ratio and the coating weight gain exerted a significant effect on the dissolution rate with a 10-fold increase compared to the pure drug and physical mixture at PVP/SM ratio of 4:1 and coating weight gain of 100%. Similarly, Zhang et al. [113] prepared SDs of lansoprazole (LSP)/PVP using fluid bed coating technique at a controlled processing temperature of less than 30 °C (considering stability of LSP). The LSP and PVP were dissolved in acetone/ethanol (20:80) and sprayed onto non-pareil cores using a Mini-Glatt fluid bed system. The SDs of lansoprazole/PVP contained amorphous LSP and displayed a dramatic increase in the solubility. Fluid bed technique was also used for generating wax-based floating SD pellets [114] and dispersion pellets of protocatechuic acid exhibiting a sustained release. The pellets were coated with drug/ethyl cellulose using a single-step, fluid bed coating method. Solid state characterization revealed the drug to be dispersed in an amorphous molecular form. Moreover, the prepared formulation had excellent floating properties and sustained the drug release for 12 h. Dereymaker et al. [115] studied the influence of formulation parameters and provided an insight into complex coated systems using chemometric methods for use in drug delivery system with a controlled release layered indomethacin glass solution. A 10% (w/v) ethanolic indomethacin-PVP (70:30) glass solution was coated onto sucrose beads. The dried spheres were coated with a rate-controlling layer consisting of either Eudragit RL (ERL), EC, or ERL/EC with PVP. PVP acted as a pore former and exhibited significant effect on the drug release. ERL, being more hydrophilic, displayed higher diffusion rates and a faster drug release compared to EC.

Fluid bed layering has also been used for preparing a drug–cyclodextrin complex to improve the bioavailability of poorly soluble drugs. For example, Lu et al. [116] successfully prepared a meloxicam-β-cyclodextrin complex by solvent removal and simultaneous deposition onto non-pareil cores using fluid bed layering. The synthesized pellets contained meloxicam in the amorphous form with a dramatic increase in the dissolution in a phosphate buffer at pH 7.4. These reports revealed the application of fluid bed technology in the production of ASDs along with conventional applications. A summary of above-discussed strategies is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of Hot Melt Extrusion, Kinetisol®, Spray drying, and Fluidized bed Technology processes to formulate amorphous solid dispersions [49,51,88,117–127].

| Technology | Principle | Applicability | Limitations | Commercial feasibility | Commercial products | Factors affecting yield of final product |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hot melt extrusion | Co-dispersion of API and polymer with aid of shear stress and thermal energy | Continuous process for production of amorphous dispersions Multiple applications including solubility improvement |

Applicability to thermo liable, shear sensitive compounds and high melting point APIs | Commercially scalable, continuous and solvent free process | Kaletra®, Norvir®, Viekira XR™, Mavyret™ and Venclexta™ (AbbVie). Intelence® (Janssen), Certican and Zortress® (Novartis). | Number of mixing zones, shear, drug load, and plasticizer concentrations and type, batch size |

| Kinetisol® | Combination of collective mechanical forces leading to the increase of temperature forming a molten mixture | Specifically, applicable to drugs with high melting points and low solubility in organic solvents | Commercial scalability | Yet to be proved for continuous fullscale commercial manufacturing | No marketed amorphous solid dispersion products are available. | Processing speed, discharge temperature, lubricant levels, processing times |

| Spray drying | Formation of solid dispersion by rapid evaporation of the solvent from the fluidized drug carrier mixture leads to kinetic entrapment of drug in carrier matrix. | Encapsulation and formation of complexes in various drug delivery systems | Solvent based technique; cost effectiveness | Commercially scalable | Incivek™, Kalydeco®, Orkambi®, Symdeko and Delstrigo (Vertex) Harvoni® and Epclusa® (Gilead Sciences), Zepatier® (Merck). | Outlet and inlet temperatures, atomization gas flow rate and pressure, batch size, feed rate, total feed concentration and viscosity, carrier concentrations and grades |

| Fluidized bed Technology | Distribution of the dosage form on multiple particles which comprise a single unit | Applicability in different delivery systems and avoidance of dose dumping | High production cost Compaction problems in tablets and applicability to high doses |

Commercially scalable | Sporanox® (Janssen Pharmaceuticals), Nimotop®(Bayer) Prograf® (Astellas PharmaInc.) | Inlet air temperature, feed flow rate, atomization rate and pressure, binary nozzle air pressure and position, batch size |

3. Conclusion

Literature reports several thermal strategies that have been widely employed for developing ASDs. Each of these has garnered enormous interest in the pharmaceutical industry, owing to its specific advantages and characteristics. For instance, HME, an eco-friendly process, has been attracting the attention of researchers owing to its ability as a continuous manufacturing process. However, spray drying has its own importance in the industry for developing SDs of materials that cannot be processed by HME. In fact, HME may not be useful for polymers with high thermal processing temperatures and for thermolabile drugs, a shortcoming that can be easily overcome by use of plasticizers. Another technology which was also investigated for ASDs dispersion is the fluid bed technology. A novel alternative thermal processing technology termed as the Kinetisol® dispersing technology operates on the combinatorial principle of shear force and friction for the rapid transformation of the physical blend into a molten state to produce a homogenous SD. These findings suggest that the selection of an appropriate strategy for synthesizing ASDs is based on the physicochemical properties of the drug and polymers that aid the production of a thermally and physically stable product.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a grant (Grant Number P20GM104932) from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences and the Biopharmaceutics-Clinical and Translational Core E of the COBRE, a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Footnotes

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jddst.2019.101459.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- [1].Zi P, Zhang C, Ju C, Su Z, Bao Y, Gao J, Sun J, Lu J, Zhang C, Solubility and bioavailability enhancement study of lopinavir solid dispersion matrixed with a polymeric surfactant-Soluplus, Eur. J. Pharm. Sci 134 (2019) 233–245, 10.1016/j.ejps.2019.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Almutairi M, Almutairy B, Sarabu S, Almotairy A, Ashour E, Bandari S, Batra A, Tewari D, Durig T, Repka MA, Processability of AquaSolve™ LG polymer by hot-melt extrusion: effects of pressurized CO2 on physicomechanical properties and API stability, J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol 52 (2019) 165–176, 10.1016/j.jddst.2019.04.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Dedroog S, Huygens C, Van den Mooter G, Chemically identical but physically different: a comparison of spray drying, hot melt extrusion and cryo-milling for the formulation of high drug loaded amorphous solid dispersions of naproxen, Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm 135 (2019) 1–12, 10.1016/j.ejps.2019.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Pozzoli M, Traini D, Young PM, Sukkar MB, Sonvico F, Development of a Soluplus budesonide freeze-dried powder for nasal drug delivery, Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm 43 (2017) 1510–1518, 10.1080/03639045.2017.1321659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Jermain SV, Miller D, Spangenberg A, Lu X, Moon C, Su Y, Williams RO, Homogeneity of amorphous solid dispersions–an example with KinetiSol®, Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm 24 (2019) 1–12, 10.1080/03639045.2019.1569037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Vasconcelos T, Marques S, Das Neves J, Sarmento B, Amorphous solid dispersions: rational selection of a manufacturing process, Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev 100 (2016) 85–101, 10.1016/j.addr.2016.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Skrdla PJ, Floyd PD, Dell’Orco PC, Predicted amorphous solubility and dissolution rate advantages following moisture sorption: case studies of indomethacin and felodipine, Int. J. Pharm 555 (2019) 100–108, 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2018.11.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Mori Y, Motoyama K, Ishida M, Onodera R, Higashi T, Arima H, Theoretical and practical evaluation of lowly hydrolyzed polyvinyl alcohol as a potential carrier for hot-melt extrusion, Int. J. Pharm 555 (2019) 124–134, 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2018.11.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Ma X, Huang S, Lowinger MB, Liu X, Lu X, Su Y, Williams III RO, Influence of mechanical and thermal energy on nifedipine amorphous solid dispersions prepared by hot melt extrusion: preparation and physical stability, Int. J. Pharm 561 (2019) 324–334, 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2019.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Hossain S, Kabedev A, Parrow A, Bergström C, Larsson P, Molecular simulation as a computational pharmaceutics tool to predict drug solubility, solubilization processes and partitioning, Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm 137 (2019) 46–55, 10.1016/j.ejpb.2019.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Mohammad MA, Alhalaweh A, Velaga SP, Hansen solubility parameter as a tool to predict cocrystal formation, Int. J. Pharm 407 (2011) 63–71, 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2011.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Liu J, Cao F, Zhang C, Ping Q, Use of polymer combinations in the preparation of solid dispersions of a thermally unstable drug by hot-melt extrusion, Acta Pharm. Sin. B 3 (2013) 263–272, 10.1016/j.apsb.2013.06.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Zhao Y, Inbar P, Chokshi HP, Malick AW, Choi DS, Prediction of the thermal phase diagram of amorphous solid dispersions by Flory–Huggins theory, J. Pharm. Sci 100 (2011) 3196–3207, 10.1002/jps.22541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Amharar Y, Curtin V, Gallagher KH, Healy AM, Solubility of crystalline organic compounds in high and low molecular weight amorphous matrices above and below the glass transition by zero enthalpy extrapolation, Int. J. Pharm 472 (2014) 241–247, 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2014.06.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Ouyang D, Investigating the molecular structures of solid dispersions by the simulated annealing method, Chem. Phys. Lett 554 (2012) 177–184, 10.1016/j.cplett.2012.10.056. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Ahmad S, Johnston BF, Mackay SP, Schatzlein AG, Gellert P, Sengupta D, Uchegbu IF, In Silico modelling of drug–polymer interactions for pharmaceutical formulations, J. R. Soc. Interface 7 (2010) S423–S433, 10.1098/rsif.2010.0190.focus. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Persson LC, Porter CJ, Charman WN, Bergström CA, Computational prediction of drug solubility in lipid based formulation excipients, Pharm. Res 30 (2013) 3225–3237, 10.1007/s11095-013-1083-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Gupta J, Nunes C, Vyas S, Jonnalagadda S, Prediction of solubility parameters and miscibility of pharmaceutical compounds by molecular dynamics simulations, J. Phys. Chem. B 115 (2011) 2014–2023, 10.1021/jp108540n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Pajula K, Taskinen M, Lehto VP, Ketolainen J, Korhonen O, Predicting the formation and stability of amorphous small molecule binary mixtures from computationally determined Flory− Huggins interaction parameter and phase diagram, Mol. Pharm 7 (2010) 795–804, 10.1021/mp900304p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Jaiswar DR, Jha D, Amin PD, Preparation and characterizations of stable amorphous solid solution of azithromycin by hot melt extrusion, J. Pharm. Investig 46 (2016) 655–668, 10.1007/s40005-016-0248-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Kolter H, Karl M, Grycke A, Hot-melt Extrusion with BASF Polymers: Extrusion Compendium, BASF Corp., Germany, 2012, pp. 113–116. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Maniruzzaman M, Morgan DJ, Mendham AP, Pang J, Snowden MJ, Douroumis D, Drug–polymer intermolecular interactions in hot-melt extruded solid dispersions, Int. J. Pharm 443 (2013) 199–208, 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2012.11.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Sarode AL, Sandhu H, Shah N, Malick W, Zia H, Hot melt extrusion (HME) for amorphous solid dispersions: predictive tools for processing and impact of drug–polymer interactions on supersaturation, Eur. J. Pharm. Sci 48 (2013) 371–384, 10.1016/j.ejps.2012.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Chan SY, Qi S, Craig DQ, An investigation into the influence of drug–polymer interactions on the miscibility, processability and structure of poly-vinylpyrrolidone-based hot melt extrusion formulations, Int. J. Pharm 496 (2015) 95–106, 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2015.09.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Shah S, Maddineni S, Lu J, Repka MA, Melt extrusion with poorly soluble drugs, Int. J. Pharm 453 (2013) 233–252, 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2012.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Patil H, Tiwari RV, Repka MA, Hot-Melt extrusion: from theory to application in pharmaceutical formulation, AAPS PharmSciTech 17 (2015) 20–42, 10.1208/s12249-015-0360-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Crowley MM, Zhang F, Repka MA, Thumma S, Upadhye SB, Kumar Battu S, McGinity JW, Martin C, Pharmaceutical applications of hot-melt extrusion: part I, Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm 33 (2007) 909–926, 10.1080/03639040701498759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Repka MA, Battu SK, Upadhye SB, Thumma S, Crowley MM, Zhang F, Martin C, McGinity JW, Pharmaceutical applications of hot-melt extrusion: Part II, Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm 33 (2007) 1043–1057, 10.1080/03639040701525627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Dumpa NR, Sarabu S, Bandari S, Zhang F, Repka MA, Chronotherapeutic drug delivery of ketoprofen and ibuprofen for improved treatment of early morning stiffness in arthritis using hot-melt extrusion technology, AAPS PharmSciTech 19 (2018) 2700–2709, 10.1208/s12249-018-1095-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Kallakunta VR, Tiwari R, Sarabu S, Bandari S, Repka MA, Effect of formulation and process variables on lipid based sustained release tablets via continuous twin screw granulation: a comparative study, Eur. J. Pharm. Sci 121 (2018) 126–138, 10.1016/j.ejps.2018.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Patil H, Tiwari RV, Upadhye SB, Vladyka RS, Repka MA, Formulation and development of pH-independent/dependent sustained release matrix tablets of ondansetron HCl by a continuous twin-screw melt granulation process, Int. J. Pharm 496 (2015) 33–41, 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2015.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Alshehri SM, Park J, Alsulays BB, Tiwari RV, Almutairy B, Alshetailli AS, Morott J, Shah S, Kulkarni V, Majumdar S, Martin ST, Mishra S, Wang L, Repka MA, Mefenamic acid taste-masked oral disintegrating tablets with enhanced solubility via molecular interaction produced by hot melt extrusion technology, J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol 27 (2015) 18–27, 10.1016/j.jddst.2015.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Mendonsa NS, Pradhan A, Sharma P, Prado RM, Murthy SN, Kundu S, Repka MA, A quality by design approach to develop topical creams via hot-melt extrusion technology, Eur. J. Pharm. Sci 136 (2019) 104948, 10.1016/j.ejps.2019.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Mendonsa NS, Murthy SN, Hashemnejad SM, Kundu S, Zhang F, Repka MA, Development of poloxamer gel formulations, via hot-melt extrusion technology, Int. J. Pharm 537 (2017) 122–131, 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2017.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Mendonsa NS, Thipsay P, Kim DW, Martin ST, Repka MA, Bioadhesive drug delivery system for enhancing the permeability of a bcs class iii drug via hot-melt extrusion technology, AAPS PharmSciTech 18 (2017) 2639–2647, 10.1208/s12249-017-0728-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Mididoddi PK, Repka MA, Characterization of hot-melt extruded drug delivery systems for onychomycosis, Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm 66 (2007) 95–105, 10.1016/j.ejpb.2006.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Patil H, Kulkarni V, Majumdar S, Repka MA, Continuous manufacturing of solid lipid nanoparticles by hot melt extrusion, Int. J. Pharm 471 (2014) 153–156, 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2014.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Patil H, Feng X, Ye X, Majumdar S, Repka MA, Continuous production of fenofibrate solid lipid nanoparticles by hot-melt extrusion technology: a Systematic Study Based on Quality by Design Approach, AAPS J. 17 (2014) 194–205, 10.1208/s12248-014-9674-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Ye X, Patil H, Feng X, Tiwari RV, Lu J, Gryczke A, Kolter K, Langley N, Majumdar S, Neupane D, Mishra SR, Repka MA, Conjugation of hot-melt extrusion with high-pressure homogenization: a novel method of continuously preparing nanocrystal solid dispersions, AAPS PharmSciTech 17 (2015) 78–88, 10.1208/s12249-015-0389-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Khinast J, Baumgartner R, Roblegg E, Nano-extrusion: a one-step process for manufacturing of solid nanoparticle formulations directly from the liquid phase, AAPS PharmSciTech 14 (2013) 2, 10.1208/s12249-013-9946-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Simons FJ, Wagner KG, Modeling, design and manufacture of innovative floating gastroretentive drug delivery systems based on hot-melt extruded tubes, Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm 137 (2019) 196–208, 10.1016/j.ejpb.2019.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Almutairy BK, Alshetaili AS, Ashour EA, Patil H, Tiwari RV, Alshehri SM, Repka MA, Development of floating drug delivery system with superior buoyancy in gastric fluid using hot-melt extrusion coupled with pressurized CO2, Pharmazie 71 (2016) 128–133, 10.1691/ph.2016.5105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Alig I, Fischer D, Lellinger D, Steinhoff B, Combination of NIR, Raman, ultrasonic and dielectric spectroscopy for in-line monitoring of the extrusion process, Macromol. Symp (2005) 51–58, 10.1002/masy.200551141 WILEY‐VCH Verlag. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Morott JT, Pimparade M, Park JB, Worley CP, Majumdar S, Lian Z, Pinto E, Bi Y, Durig T, Repka MA, The effects of screw configuration and polymeric carriers on hot-melt extruded taste-masked formulations incorporated into orally disintegrating tablets, J. Pharm. Sci 104 (2015) 124–134, 10.1002/jps.24262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Teixeira C, Covas JA, Stützle T, Gaspar Cunha A, Multi-objective ant colony optimization for the twin-screw configuration problem, Eng. Optim 44 (2012) 351–371, 10.1080/0305215X.2011.639370. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Repka MA, Prodduturi S, Stodghill SP, Production and characterization of hot-melt extruded films containing clotrimazole, Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm 29 (2003) 757–765, 10.1081/DDC-120021775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Trey SM, Wicks DA, Mididoddi PK, Repka MA, Delivery of itraconazole from extruded HPC films, Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm 33 (2007) 727–735, 10.1080/03639040701199225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Palem CR, Battu SK, Maddineni S, Gannu R, Repka MA, Yamsani MR, Oral transmucosal delivery of domperidone from immediate release films produced via hot-melt extrusion technology, Pharm. Dev. Technol 18 (2013) 186–195, 10.3109/10837450.2012.693505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Tiwari RV, Patil H, Repka MA, Contribution of hot-melt extrusion technology to advance drug delivery in the 21st century, Expert Opin. Drug Deliv 13 (2016) 451–464, 10.1517/17425247.2016.1126246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Young CR, Koleng JJ, McGinity JW, Production of spherical pellets by a hot-melt extrusion and spheronization process, Int. J. Pharm 242 (2002) 87–92, 10.1016/S0378-5173(02)00152-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Repka MA, Shah S, Lu J, Maddineni S, Morott J, Patwardhan K, Mohammed NN, Melt extrusion: process to product, Expert Opin. Drug Deliv 9 (2012) 105–125, 10.1517/17425247.2012.642365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Andrews GP, Jones DS, Diak OA, McCoy CP, Watts AB, McGinity JW, The manufacture and characterisation of hot-melt extruded enteric tablets, Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm 69 (2008) 264–273, 10.1016/j.ejpb.2007.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Verreck G, Decorte A, Heymans K, Adriaensen J, Cleeren D, Jacobs A, Liu D, Tomasko D, Arien A, Peeters J, Rombaut P, Van de Mooter G, Brewster ME, The effect of pressurized carbon dioxide as a temporary plasticizer and foaming agent on the hot stage extrusion process and extrudate properties of solid dispersions of itraconazole with PVP-VA 64, Eur. J. Pharm. Sci 26 (2005) 349–358, 10.1016/j.ejps.2005.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Quinten T, Gonnissen Y, Adriaens E, De Beer T, Cnudde V, Masschaele B, Hoorebeke LV, Siepmann J, Remon JP, Vervaet C, Development of injection moulded matrix tablets based on mixtures of ethylcellulose and low-substituted hydroxypropylcellulose, Eur. J. Pharm. Sci 37 (2009) 207–216, 10.1016/j.ejps.2009.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Mishra M, Overview of encapsulation and controlled release, Handb. Encapsulation control. Release, 2016, pp. 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- [56].Nakamichi K, Nakano T, Yasuura H, Izumi S, Kawashima Y, The role of the kneading paddle and the effects of screw revolution speed and water content on the preparation of solid dispersions using a twin-screw extruder, Int. J. Pharm 241 (2002) 203–211, 10.1016/S0378-5173(02)00134-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Verhoeven E, De Beer TRM, Van den Mooter G, Remon JP, Vervaet C, Influence of formulation and process parameters on the release characteristics of ethylcellulose sustained-release mini-matrices produced by hot-melt extrusion, Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm 69 (2008) 312–319, 10.1016/j.ejpb.2007.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Liu H, Wang P, Zhang X, Shen F, Gogos CG, Effects of extrusion process parameters on the dissolution behavior of indomethacin in Eudragit® E PO solid dispersions, Int. J. Pharm 383 (2010) 161–169, 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2009.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Maniruzzaman M, Nokhodchi A, Continuous manufacturing via hot-melt extrusion and scale up: regulatory matters, Drug Discov. Today Elsevier Ltd 22 (2017) 340–351, 10.1016/j.drudis.2016.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Iosio T, Voinovich D, Grassi M, Pinto JF, Perissutti B, Zacchigna M, Quintavalle U, Serdoz F, Bi-layered self-emulsifying pellets prepared by co-extrusion and spheronization: influence of formulation variables and preliminary study on the in vivo absorption, Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm 69 (2008) 686–697, 10.1016/j.ejpb.2007.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Mofidfar M, Wang J, Long L, Hager CL, Vareechon C, Pearlman E, Baer E, Ghannoum M, Wnek GE, Polymeric nanofiber/antifungal formulations using a novel Co-extrusion approach, AAPS PharmSciTech 18 (2017) 1917–1924, 10.1208/s12249-016-0664-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Wang J, Langhe D, Ponting M, Wnek GE, Korley LT, Baer E, Manufacturing of polymer continuous nanofibers using a novel co-extrusion and multiplication technique, Polymer (Guildf) 55 (2014) 673–685, 10.1016/j.polymer.2013.12.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Vynckier AK, Dierickx L, Voorspoels J, Gonnissen Y, remon JP, Vervaet C, Hot-melt co-extrusion: requirements, challenges and opportunities for pharmaceutical applications, J. Pharm. Pharmacol 66 (2014) 167–179, 10.1111/jphp.12091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Quintavalle U, Voinovich D, Perissutti B, Serdoz F, Grassi M, Theoretical and experimental characterization of stearic acid-based sustained release devices obtained by hot melt co-extrusion, J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol 17 (2007) 415–420, 10.1016/S1773-2247(07)50082-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Vynckier AK, Voorspoels J, Remon JP, Vervaet C, Co-extrusion as a processing technique to manufacture a dual sustained release fixed-dose combination product, J. Pharm. Pharmacol 68 (2016) 721–727, 10.1111/jphp.12521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Dierickx L, Van Snick B, Monteyne T, De Beer T, Remon JP, Vervaet C, Coextruded solid solutions as immediate release fixed-dose combinations, Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm 88 (2014) 502–509, 10.1016/j.ejpb.2014.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Quintavalle U, Voinovich D, Perissutti B, Serdoz F, Grassi G, Dal Col A, Grassi M, Preparation of sustained release co-extrudates by hot-melt extrusion and mathematical modelling of in vitro/in vivo drug release profiles, Eur. J. Pharm. Sci 33 (2008) 282–293, 10.1016/j.ejps.2007.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Dierickx L, Saerens L, Almeida A, De Beer T, Remon JP, Vervaet C, Co-extrusion as manufacturing technique for fixed-dose combination mini-matrices, Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm 81 (2012) 683–689, 10.1016/j.ejpb.2012.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Ashour EA, Kulkarni V, Almutairy B, Park JB, Shah SP, Majumdar S, Lian Z, Pinto E, Bi V, Durig T, Martin ST, Repka MA, Influence of pressurized carbon dioxide on ketoprofen-incorporated hot-melt extruded low molecular weight hydroxypropylcellulose, Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm 42 (2016) 123–130, 10.3109/03639045.2015.1035282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Verreck G, Decorte A, Li H, Tomasko D, Arien A, Peeters J, Rombaut P, Van den Mooter G, Brewster ME, The effect of pressurized carbon dioxide as a plasticizer and foaming agent on the hot melt extrusion process and extrudate properties of pharmaceutical polymers, J. Supercrit. Fluids 38 (2006) 383–391, 10.1016/j.supflu.2005.11.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [71].De Brabander C, Van Den Mooter G, Vervaet C, Remon JP, Characterization of ibuprofen as a non-traditional plasticizer of ethyl cellulose, J. Pharm. Sci 91 (2002) 1678–1685, 10.1002/jps.10159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Repka MA, McGinity JW, Influence of Vitamin E TPGS on the properties of hydrophilic films produced by hot-melt extrusion, Int. J. Pharm 202 (2000) 63–70, 10.1016/S0378-5173(00)00418-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Ellenberger DJ, Miller DA, Williams RO, Expanding the application and formulation space of amorphous solid dispersions with KinetiSol®: a review, AAPS PharmSciTech 19 (2018) 1933–1956, 10.1208/s12249-018-1007-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Keen JM, McGinity JW, Williams III RO, Enhancing bioavailability through thermal processing, Int. J. Pharm 450 (2013) 185–196, 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2013.04.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].LaFountaine JS, Jermain SV, Prasad LK, Brough C, Miller DA, Lubda D, McGinity JW, Williams RO III, Enabling thermal processing of ritonavir–polyvinyl alcohol amorphous solid dispersions by KinetiSol® Dispersing, Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm 101 (2016) 72–81, 10.1016/j.ejpb.2016.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Hughey JR, Keen JM, Miller DA, Brough C, McGinity JW, Preparation and characterization of fusion processed solid dispersion containing a viscous thermally labile polymeric carrier, Int. J. Pharm 438 (2012) 11–19, 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2012.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].LaFountaine JS, Prasad LK, Brough C, Miller DA, McGinity JW, Williams RO III, Thermal processing of PVP-and HPMC-based amorphous solid dispersion, AAPS PharmSciTech 17 (2016) 120–132, 10.1208/s12249-015-0417-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].DiNunzio JC, Brough C, Hughey JR, Miller DA, Williams III RO, McGinity JW, Fusion production of solid dispersion containing a heat-sensitive active ingredient by hot melt extrusion and Kinetisol® dispersing, Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm 74 (2010) 340–351, 10.1016/j.ejpb.2009.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Lu W, Rades T, Rantanen J, Yang M, Inhalable co-amorphous budesonide-arginine dry powders prepared by spray drying, Int. J. Pharm 565 (2019) 1–8, 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2019.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Miller DA, Gill M, Spray-drying technology, in: Williams RO III Watts AB, Miller DA, Gill M (Eds.), Formulating Poorly Water-Soluble Drugs, Springer, New York, 2012, pp. 363–442. [Google Scholar]

- [81].Kamlet MJ, Abboud JLM, Abraham MH, Taft RW, Linear solvation energy relationships. 23. A comprehensive collection of the solvatochromicparameters,.pi.*,. alpha., and. beta., and some methods for simplifying the generalized solvatochromic equation, J. Org. Chem 48 (1983) 2877–2887, 10.1021/jo00165a018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]