Abstract

Background:

Given the challenges of governments to deliver primary health care (PHC), engaging private sector in the form of public-private partnership (PPP) can be effective policy. The aim of present study is to review the experiences of implementing PPP policy in PHC.

Methods:

This scoping review study was conducted in 2019 using the framework proposed by Arkesy and O’Malley. Required data were collected through search the related keywords in databases, manual search of some journals, websites, and other sources of information and through references check, from January 2000 to May 2019. All studies, which focused on the results of PPP in PHC, and published in English or Persian were included in the study.

Results:

A total of 108 articles were included in the study. The studies were mostly conducted in low- and middle-income countries. The quantitative studies have demonstrated the success of this policy in improving PHC indicators. Based on the qualitative studies PPP in PHC has many benefits, including access improvement, economic benefits, and service quality enhancement.

Conclusions:

The present study provides useful information on the experiences of different countries in the field of PPP in PHC that can be used by experts and decision makers to decide whether to engage the private sector in the form of PPP model.

Keywords: public-private partnership, private sector, primary health care, scoping review

Introduction

The ultimate goal of health system in each country is to improve the health of people to be able to participate actively in economic and social activities while enjoying health.1 Undoubtedly, today primary health care (PHC) is the main strategy of countries for achieving this goal.2 In a 2008 report, the World Health Organization states, “There is no longer any doubt that by changing the previous practice (focusing solely on clinical services) and emphasizing the PHC, the cost-effectiveness of health services can be improved.”3 In fact, to achieve the values of PHC including equity, people-centeredness, and community participation, service delivery structure should be changed and the challenges of PHC, as the gateway for people to enter the health system, must be met.4

Till now, different approaches to address the health system’ challenges are used by countries, of which one of the most effective is public-private partnership (PPP), which as a bilateral partnership and win-win policy, makes use of the capacities of both public and private parties to achieve the goals.5-7 In general, PPP is a mechanism whereby the public sector (government and other governmental entities) in order to provide the infrastructure services (water and wastewater, transportation, health, education, etc) utilizes the capacity of the private sector (cooperatives, private companies, charities, and nongovernmental organizations [NGOs]), including knowledge, experience, and financial resources. In PPP, a contract would conclude between the public and private sector to share the risk, responsibility and benefits, and to synchronize resources and expertise of both sectors in providing infrastructure services.5 In PPP, the role of government changes from investor, implementer, and beneficiary of infrastructure projects to policy maker, regulator, and supervisor of the quality and quantity of provided services.8-10

The private sector considers the PPP as a viable solution and opportunity for market growth and profit making, which also provide adequate facilities and innovative management for the public sector.5,9 Governments use PPP as an efficient and cost-effective mechanism in implementing their goals and policies.11 If PPP plans are implemented, insurance companies can increase people’s satisfaction at a lower cost and also allow better and more accurate monitoring of the quality of service provision in the private sector. Under such conditions, people are expected to receive more diverse services with more coverage, higher quality, better access, and even lower costs, which will in turn improve their health and satisfaction.12

Given the importance of PHC to promote the health of the community and due to the problems and shortcomings in this area, the use of private sector capacities and capabilities, which can be realized in the form of PPP, can be effective and useful in this regard. That is why there is a need to examine the performance and achievements of PPP in the field of PHC worldwide to be used in policy making and designing proper structures and patterns in each country, especially in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). Therefore, the aim of the present study is to study the experiences of implementation PPP policy in PHC through scoping review.

Materials and Methods

In this study, Arkesy and O’Malley framework was used for scoping review, which include 6 steps of identification of the research question, identification of relevant studies, study selection, data charting, data analysis, and reporting the results and consultation exercise.13

Step 1: Identification of Relevant Studies

The main research question of the present study is “What are the results and achievements of PPP in the provision of PHC in different countries?” which specifically include following questions:

In which countries is PPP in the provision of PHC prevalent?

How is the time trend of using PPP in the provision of PHC worldwide?

In which settings (urban, rural, suburbs, etc) PPP in the provision of PHC is most prevalent?

Which models of PPP are used to provide PHC?

What are the role and responsibilities of the public and private sectors in the PPP in PHC plans?

What are the goals of using PPP in the provision of PHC in different countries?

For what tasks and services PPP has been applied in the provision of PHC?

What are the achievements of implementing PPP policy in the provision of PHC worldwide?

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

All articles and reports on using PPP in the PHC projects published in Persian or English between 2000 and 2019 were included. Studies written in English or Persian (which could be translated by a member of our team) were included. The articles and studies that report the experience of implementing PPP plans in other health sectors (other than PHC) were excluded.

Step 2: Identification of Relevant Studies

In this phase, required data were extracted from PubMed, Scopus, Science Direct, Web of Science, and Embase databases. The keywords were searched in different areas of primary health care, including primary health care, tuberculosis, vaccination, and so on. Persian equivalent of the above searches was performed in Persian databases like MagIran and SID. The time frame selected for searching the articles was January 2000 to May 2019 (Appendix 1 in the Supplementary Material). Table 1 shows the search strategy proposed for PubMed.

Table 1.

Search Strategy for the PubMed Database.

| Search number | Areas | Search string |

|---|---|---|

| #1 | private OR “public private partnership” OR “public private participation” OR “public-private mix” OR “public-private cooperation” OR “mixed system” OR privatiz* OR “public-private coordination” OR “public-private collaboration” OR “contract* out” OR outsource* OR “Servic* contract*” OR “management contract*” OR “lease* contract*” OR “Private Finance Initiative Contract*” OR “concession contract*” OR “divesture contract*”. | |

| #2 | Primary health care | “primary health care OR “primary health services” OR PHC OR “basic health care” OR “primary care” |

| #3 | Tuberculosis | TB OR tuberculosis |

| #4 | Vaccination | Immunization OR vaccination OR vaccine |

| #5 | Maternal and child care | maternity OR child* OR maternal OR mother* OR midwifery OR pregnancy |

| #6 | Screening | Screening |

| #7 | Case finding | “Case find*” OR “find* case” OR “case detection” OR “detect* case” |

| #8 | Health education | “Health education” OR “health training” OR “health teaching” OR “health promotion” |

| #9 | Mental health | “Mental health*” |

| #10 | Occupational health | “Occupational health*” OR “occupational hygiene” |

| #11 | Environmental health | “Environmental health*” OR “environmental hygiene” OR “water hygiene” OR “wastewater hygiene” OR “water health” OR “wastewater health” |

| #12 | Oral health | “Oral health*” OR “tooth health*” OR “dental health*” OR “oral hygiene” OR “tooth hygiene” OR “dental hygiene” |

| #13 | Congenital Anomalies | “Thalassemia*” OR “hemophilia*” |

| #14 | Family medicine | “Family physician” OR “family medicine” OR “family doctor” |

| #15 | Elderly health | “Elderly health*” OR “aging health*” OR “aged health*” OR “older health*” OR “elderly care” OR “aging care” OR “aged care” OR “older care” |

| #16 | School health | “School health” OR “student health” |

| #17 | Surveillance | “Surveillance” |

| #18 | Diabetes | Diabet* |

| #19 | Hypertension | “Blood pressure” OR “high blood pressure” OR hypertension |

| #20 | Asthma | “Asthma” |

| #21 | Cancer | “Cancer” |

| #22 | Noncommunicable diseases (general) | “Non-communicable diseases” OR “noncommunicable diseases” |

| #23 | HIV | “HIV” OR “AIDS” OR “Human immunodeficiency virus infection” OR “acquired immune deficiency syndrome” |

| #24 | Hepatitis | “Hepatitis” |

| #25 | STD | “Sexually transmit*” OR “STD” OR “STI” |

| #26 | Malaria | “Malaria” |

| #27 | Pediculosis | “Pediculosis” OR “lice” OR “phthiriasis” |

| #28 | Fecal-oral diseases | “Water and food borne” OR “fecal-oral” OR “diarrheal” OR “diarrhea” OR “food poisoning” OR “Water intoxication” OR parasite OR “Gastrointestinal” OR cholera |

| #29 | Influenza | “Influenza” OR “flu” |

| #30 | Communicable diseases (general) | “Communicable diseases” |

| #31 | Rabies | Rabies OR rabid |

| #32 | Malta fever | “Malta fever” OR brucellosis OR “brucella Infection” OR “brucella fever” |

| #33 | Anthrax | Anthrax |

| #34 | Ebola | Ebola |

| #35 | Neglected disease | “Neglected disease*” |

| #36 | #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5 OR #6 OR #7 OR #8 OR #9 OR #10 OR #11 OR #12 OR #13 OR #14 OR #15 OR #16 OR #17 OR #18 OR #19 OR #20 OR #21 OR #22 OR #23 OR #24 OR #25 OR #26 OR #27 OR #28 OR #29 OR #30 OR #31 OR #32 OR #33 OR #34 OR #35 | |

| #37 | #1 AND #36 |

To identify and cover of further published articles, after searching databases, selected journals and articles references were manually searched. In addition, Google Scholar, published organizational reports and government documents, websites, and other available information sources were also searched.

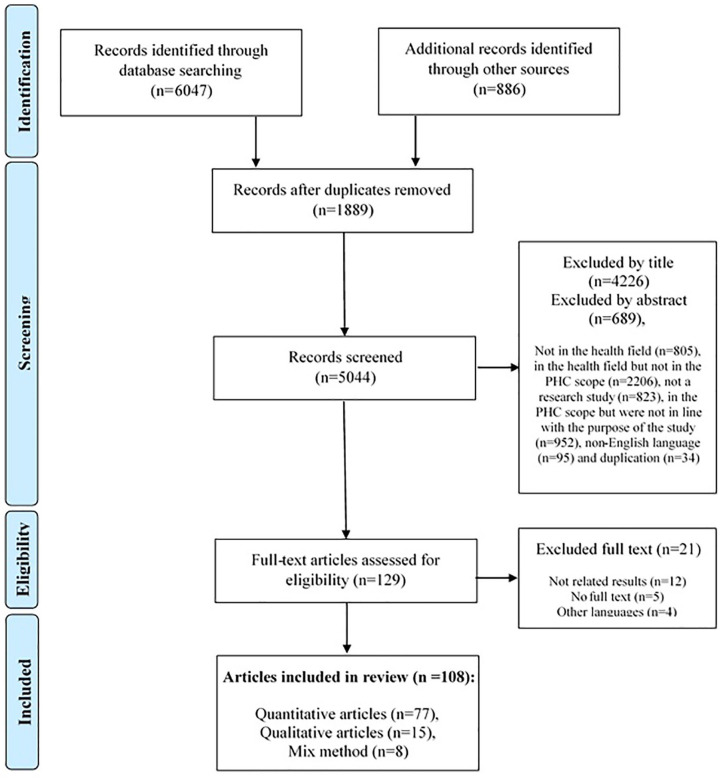

Step 3: Study Selection

The entire process of selection and screening of studies were performed independently by 2 members of the research team. Disagreements have been resolved through discussion in the first instance, otherwise were referred to a third party with more knowledge and experience. At first, the titles of all articles were reviewed, and those that were not consistent with the study objectives were excluded. Subsequently, abstracts and full texts of the articles were studied in order to identify and exclude studies that met exclusion criteria and had poor correlation with study objectives. Given that the structure of PHC delivery varies across countries, to determine whether the provided services are PHC, 2 researchers examined the information provided in each study and determined whether they were PHC or not. Thus, the types of services were determined based on the information provided and the agreement between the researchers. In case of disagreement, the agreement was reached through discussion between the 2 researchers. If no agreement was reached through discussion between the 2 researchers, cases were referred to a third party, who had higher expertise and experience in the field of PHC. Endnote X5 was used to organize and identify duplicates, as well as read the titles and abstracts. PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) flowchart14-16 was used to report the results of screening and selection process (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Selection of sources of evidence.

Step 4: Data Charting

To extract data from quantitative and qualitative studies, at first 2 data extraction forms were manually designed using the Microsoft Word 2010 software. At first, the data of 3 articles were extracted tentatively using these forms and the deficiencies and problems in the original form were solved. The information was extracted independently by 2 researchers and the ambiguities were resolved in consultation with other members of the research team. Information extractable using quantitative study form included: author, year of publication, country of study, study context (city, village, settlers, etc), aim of study, study design, participants (private and public sector), the subject of the study, the interval between the implementation of the PPP plan and the evaluation, the role of the public and private sector, the applied public-private partnership models, the studied indicators, the results, the overall outcome of implementation of PPP plan, and the conclusions. Data extractable using the qualitative studies form included the following: author and year of publication, country of study, aim of study, participants, method of data collection and results.

As defined by the Canadian Council for Public-Private Partnerships (2011),17 PPP models include design-build, design-build-maintain, design-build-operate, lease-operate-maintain, design-build-operate-maintain, build-own-operate-transfer, concession, and build-own-operate. Therefore, outsourcing is not part of PPP, but in some studies, it has been classified as part of PPP projects. Articles that categorized this method as one of the PPP models were reviewed by the research team and the data obtained showed that these studies met all PPP criteria, such as long-term contract, significant financial risk for private sector, and so on that provided by the World Bank for PPP projects,18 and consequently entered into the study as PPP plans based on the research team’s decision. On the other hand, in case of studies that did not directly refer to the PPP model used, 2 researchers determined the PPP model based on the information provided by the study. Cases where disagreement between the 2 researchers were not resolved through discussion were referred to the third person.

The results of the studies were reviewed by 2 researchers and categorized into 4 categories: positive/effective, somewhat positive/effective, neutral (no effect), and negative/bad effect. Disagreements were discussed between the 2 researchers and in cases where the dispute was not resolved it was referred to a third party.

In order to determine the study design, the information provided in each study were reviewed by 2 researchers and based on the agreement between the researchers, the type of study design determined. In case of disagreement, the disputes were referred to a third researcher with more experience and expertise.

Step 5: Data Analysis and Reporting the Results

After extracting the data by data extraction form, the extracted data were manually analyzed, summarized, and reported using the content-analysis method. Content analysis is a method for identifying, analyzing, and reporting patterns (themes) within the text and is widely used in qualitative data analysis.19-22 Data were coded independently by 2 researchers. The steps for analyzing and coding the data were: Familiarity with the text of articles (immersion in article results), identifying and extracting primary themes (identifying and extracting studies related to primary themes), placing articles in determined themes, reviewing and completing the results of each theme with the use of results of the articles, and ensure the reliability of the themes and the results extracted in each theme. In cases of disagreement between the 2 coders, the dispute was resolved through discussion and if an agreement was not obtained, the disagreement was referred to a third researcher.

Step 6: Consultation Exercise

After extracting the results, based on the results obtained and the opinions of the research team’s members, tips and suggestions were presented in the form of article discussion.

Results

Of the 6933 studies and experiences found through searching the databases and other information sources, 1889 studies were excluded in duplicate articles screening, and 4915 articles were excluded with regard to title and abstract screening. Also 21 studies were excluded due to lack of enough information. Finally, 108 articles (including 85 quantitative and 23 qualitative) were included in the study (Figure 1) (Appendix 2 in the Supplementary Material).

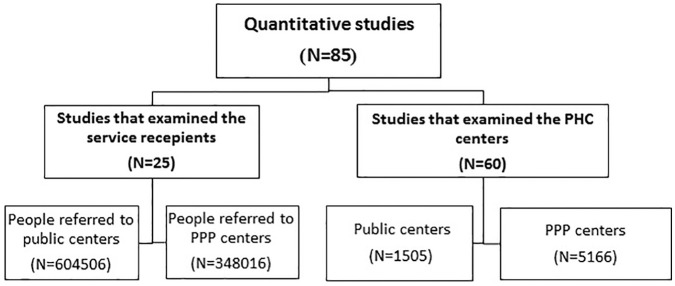

Sample Population of Included Studies

Based on the findings of present study from all quantitative articles found, most studies have examined PHC centers as study unit, of which mostly examining the performance of PPP centers exclusively (without comparing with the public centers). In the studies that surveyed individuals, the sample population was mostly selected from those who had referred to public centers to receive PHC services (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Sample population of studies on implementation of public-private partnerships in primary health care based on studied units.

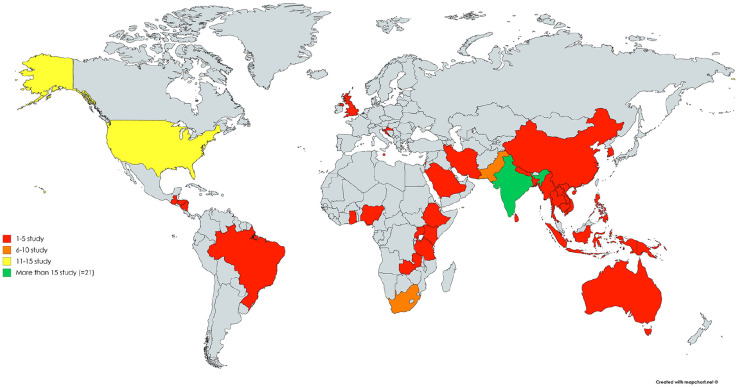

Geographical Distribution of Included Studies

In total, included studies have been conducted in 35 countries. Most studies have been conducted in India. Based on the latest World Bank Classification in 2019-2020,23 10 studies were conducted in low-income countries, 65 studies in lower-middle income countries, 15 studies in upper-middle income countries and 22 studies in high-income countries (Figure 3). It should be noted that the difference between the total number of studies in different countries and the total number of included studies is because of 2 studies were conducted in 3 countries.

Figure 3.

Geographical distribution of studies on implementation of public-private partnerships in primary health care by country.

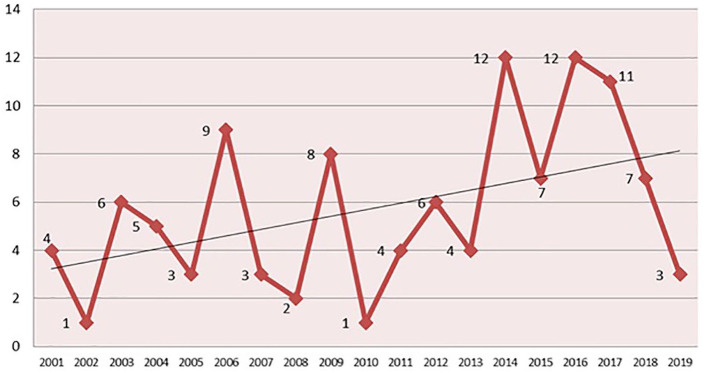

Time Trend of Included Studies

Included articles were conducted from 2001 to 2019. The results show that the trend of studies’ publication is incremental (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Time scattering of studies on implementation of public-private partnerships in primary health care by publication date.

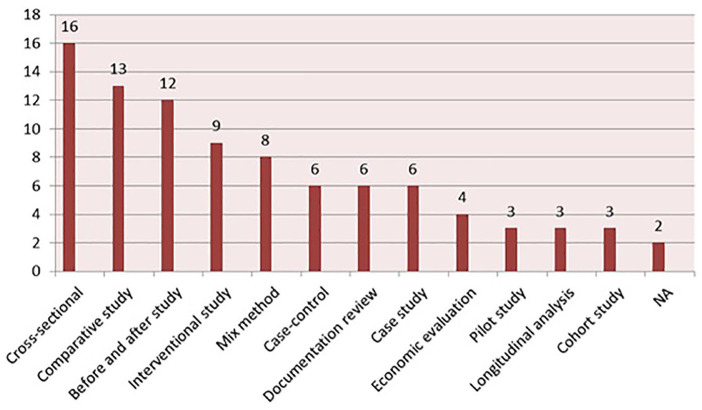

Study Design of Included Studies

Only 2 studies had not indicated the type of study design and also could not been determined based on the information provided in these studies. Most type of the studies design were cross-sectional and then comparative studies. The least type of study design found in the included studies was population-based longitudinal studies and cohort studies (Figure 5) (Appendix 3 in the Supplementary Material).

Figure 5.

Study design of studies on implementation of public-private partnerships in primary health care.

Study Context of Included Quantitative Studies

According to the information presented in the included studies, 13 studies were conducted in urban context, 16 in rural and 2 studies were implemented in both of urban and rural area. Other studies (54 studies) had not specified the study setting.

Duration of PPP Implementation

Based on the results, studies were conducted on average 26 months after the implementation of the PPP plan. The maximum time was 122 months and the shortest was 2 months after PPP implementation. In total, the time after initiation of PPP plans in included studies, was calculated 255 years and 11 months.

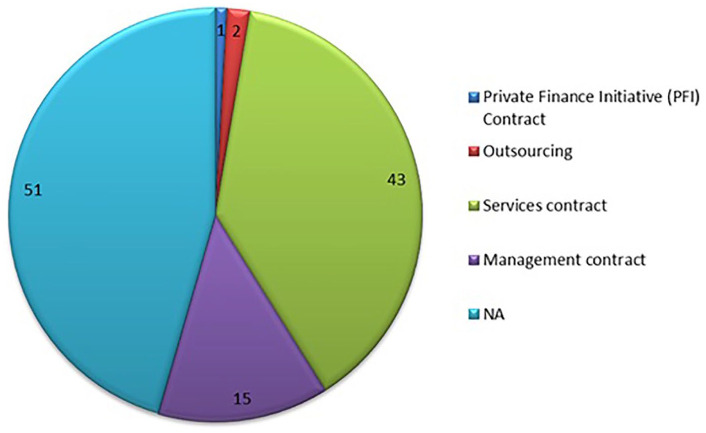

Public-Private Partnership Models in Included Studies

The results of the review of PPP models indicated that except 2 studies, the other studies had not highlighted the PPP model used in the plan. Furthermore, in most studies the type of used PPP model had not been identifiable based on the information provided. In most other studies, the PPP model used in the plan was service contract and management contract (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Type of public-private partnership (PPP) models that had been used in studies on implementation of PPP in primary health care.

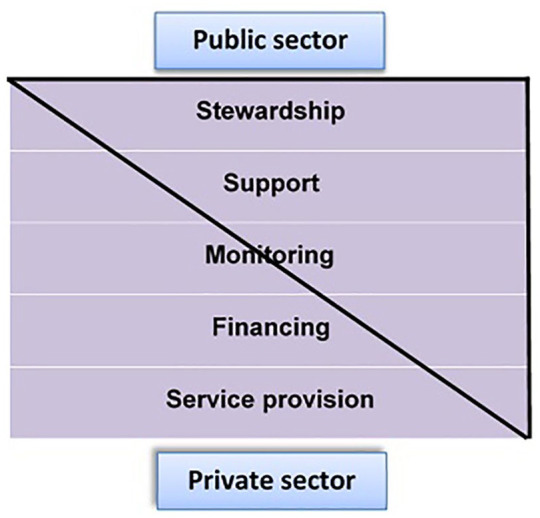

Role of Public and Private Sectors in PPP Plans

In the public sector, the highest frequency was related to supportive tasks and the least to stewardship tasks. Based on the information provided in the included articles, service provision with the most repetitive and financing and management with the least repetitive were among the tasks which had been assigned to the private sector. In 25 studies, public sector roles were not specified and in 19 studies, private sector roles were not mentioned (Table 2).

Table 2.

The Role of Public and Private Sectors in Public-Private Partnership Plans in Primary Health Care Based on Included Studies.

| Governmental | Number | Nongovernmental | Number |

|---|---|---|---|

| Supporting | 58a | Service provision | 110 |

| Monitoring | 45 | Support | 11 |

| Financing | 37 | Financing | 3 |

| Service provision | 31 | Management | 3 |

| Stewardship | 14 | Support | 5 |

| Not available | 25 | Not available | 19 |

Because of the multiple roles in a study, the number of roles exceeds the total number of included studies.

Supporting roles included activities such as organizing, training, licensing, providing drugs, providing some equipment, providing infrastructure, support, providing incentives, providing physical space, and providing human resources. The financing roles included tasks such as financing and reimbursement to the private sector. The service provision role also included activities such as drug and vaccine distribution, vaccination, giving feedback on each patient referred, diagnostic and treatment services, health education, referral of patients to higher levels, recording of patient information and diseases screening. On the other hand, the role of monitoring included activities such as monitoring and evaluation, control, treatment process monitoring, accreditation, quality assessment, and disease monitoring. The role of stewardship also included tasks such as policy making, providing treatment guidelines, providing programmatic assistance, managing of the research activities, and governing the project. Finally, the management role that had been played by the private sector involved organizing and managing a health services center.

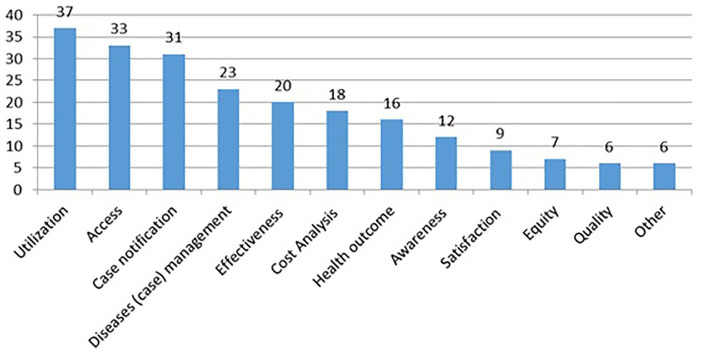

Distribution of Included Studies by Aim of the Study

The most common aim of the included studies was to measure the utilization improvement and the least was to measure the impact of PPP implementation on service quality (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Distribution of studies on implementation of public-private partnerships in primary health care by study aim.

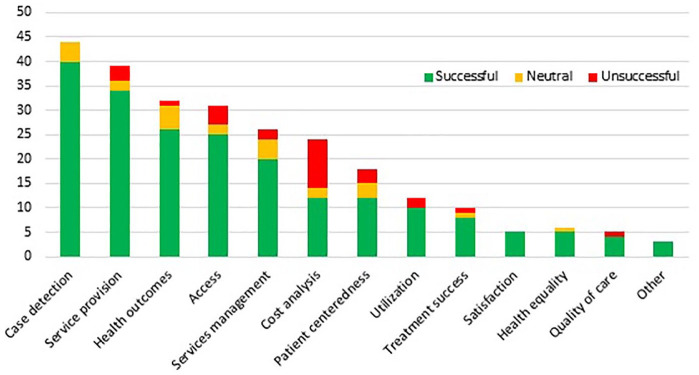

Indicators Examined to Determine the Project Success Rate

In the included studies, the case detection and service coverage, more than other indicators, had been used as criteria to measure the success of the PPP project. On the other hand, the least used indicators to measure PPP plans success were quality of care, equity, and satisfaction of service providers and service receivers (Figure 8) (Appendix 4 in the Supplementary Material).

Figure 8.

Indicators used to determine the success rate of public-private partnership in primary health care plans and their results.

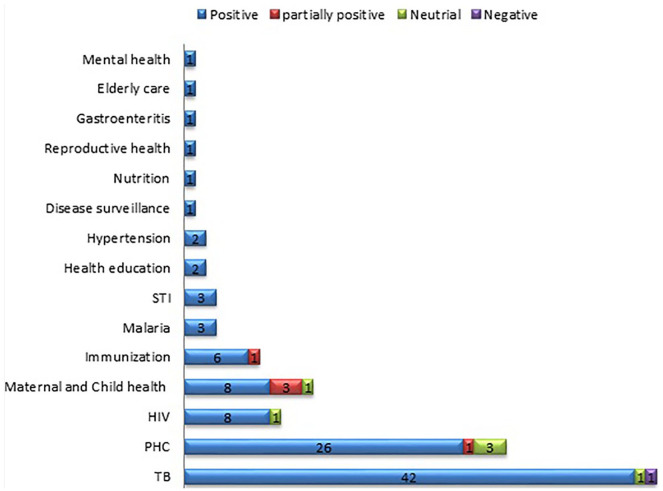

Results of Implementation of PPP in PHC by the Type of Assigned Services

Based on the results, in only one study the results of PPP implementation were negative. In most studies, the results of PPP implementation in PHC were evaluated as positive. The results in some studies were “somewhat positive” and in a few studies the project implementation evaluated as neutral (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Results of implementation of public-private partnership in primary health care by type of assigned services.

Results of Qualitative Studies

The results of qualitative studies are presented in 3 sections: advantages and disadvantages (from the experts’ perspective), achievements and failures (results from actual experiences/project implementation), and barriers and challenges (Table 3).

Table 3.

Results of Included Qualitative Studies on Implementation of Public-Private Partnership (PPP) in Primary Health Care (PHC).

| Main theme | Theme | Subtheme |

|---|---|---|

| Advantages/benefits/strengths (in the viewpoint of experts) |

Organizational/managerial | • Committed relationship over a long time • Closeness with community • Increase in department focus (core activities) • To develop innovative and more effective health programs and modes of service delivery (flexibility) • Diversity in partner expertise • High-quality monitoring and evaluation • Strong leadership • Understanding and agreeing with the national plan |

| Access | • Assurance of services access (improving access to diagnosis and treatment to many people, who could have been missed out, because of involvement of more service providers) less waiting time by patients at the facilities |

|

| Supply | PPP is better significantly in infrastructure, availability of essential medicines, basic medical appliances, mini-lab facilities and vehicles for referrals | |

| Economic | • Reducing costs to both government and private party • Governments could reinvest savings from reduced hospitalizations to strengthen publicly funded PHC. Sustainable investment |

|

| Social | • Social obligation • Community awareness Community involvement |

|

| Quality of care | • Preventing hospitalizations • Improving quality of care in general practitioner (GP) services through measures such as improved multidisciplinary coordinated care programs, training, increased nursing workforce capacity, new administrative tools or additional funding. • Improving punctuality of doctors Care coordination and continuity of care |

|

| Human resource | Learning and teaching opportunity for employees | |

| Disadvantages/weakens (in the viewpoint of experts) |

Organizational/managerial: | • More difficult accountability • Loss of control (less control, harder to control, and lack of information required for control) • Use of nonprofessional administrators |

| Quality of care | • Conflicts of interest • Negative impacts on quality of patient care |

|

| Successes/achievements (results of real experience/implemented plans) |

Health outcomes | • Improved health outcomes (in a very instance) • Iachieved targeted treatment outcomes (like more effective patient retention) |

| Quality of care | • Enhanced patient-provider relationships • Good or better continuity of care • Quality improvement • Strong health management information system (HMIS) • IRigorous follow-up |

|

| Economic | • Cost saving • IThere were gain in cost effectiveness, efficiency or revenue |

|

| Access | • Improving access to diagnosis and treatment • Providing access to training materials • ITo involve in new services |

|

| Equity | Increased access to services (including expanded hours, more service locations and improved access for vulnerable populations) | |

| Organizational/managerial | • Relief of overburdened public sector resources • Strong integration with national goals • Sufficient number of trained clinical staff • Securing commitment and ownership from all parties involved • Positive effect on the practice of health education • Better monitoring and evaluation • Increased professional opportunities • Improved risk management • IIncreased efficiency |

|

| Social | • Providing information skills training (to patients) in the community • Raised awareness • IStrong communication channels |

|

| Satisfaction | • More service receivers’ satisfaction • IPrivate practitioners’ confidence in the quality and sustainability of the public–private partnership |

|

| Supply | • having a positive experience with regard to support mechanism of the project • IAccess to specialized equipment |

|

| Failures (results of real experience/implemented plans) |

Supply | • Inefficient procurement • Failure to harmonize public-private health management information system • IIrregular resource provision (in terms of material resources) |

| Access | • Under-utilized treatment support services • IPoorer access to services |

|

| Organizational/managerial | • Weak communication channels at the district level • (Autonomy) inability of manager to determine the proportion of employees in enabler’s package • Weak evaluation • IIncreased level of administration |

|

| Equity | • Inequities in training opportunities • Inequities in higher facility utilization • IHigher out-of-pocket (driven by steeper transport costs and user charges for additional diagnostics) |

|

| Economic | • Funding challenges at the national program level • Irregular funding • Private sector is less affordable places • Increased monitoring cost • Increased administration cost because of increased level of administration • IHigher cost of provide some services privately (some director reported initial saving, but then increase in cost several years after privatization) |

|

| Quality of care | Loss of quality | |

| Barriers/limitations (before or after implementation of PPP plans) |

Organizational/managerial | • Lacking governance framework • Lacking capacity within the public sector • Uncertainty in roles and responsibilities • Bureaucratic processes • Limited representation from ministries of health in governance structure • Overburden because of extra work needed to implement the partnership activities • Shortage of expert staff within the public sector • To maintain the progress of the partnership, and to ensure joint ownership of decisions and collective responsibility for the direction and activities of the partnership. • High expectations of private providers • Unclear administrative procedures for providers • Poor relationship between GPs and hospital doctors • Differences between the primary care and hospital systems • A limited ability to negotiate prices |

| Organizational culture | • Difficulties of to bring a heterogeneous group under one umbrella • Perceived power inequities between partners |

|

| Access | • Physical distances • Limited time at clinic |

|

| Infrastructural | • Inadequate transport • Lack of equipment and medicines • Inefficiency of local officials • The shortage of trained human resources |

|

| Public culture | Low demand for facility-based care in nonemergency settings | |

| Service provider | The inability of GPs to cope with patients’ needs |

Discussion

Study results were categorized and reported under 12 main themes (sample population of included studies, geographical distribution, time scattering of included studies’ publication date, study design of included studies, study context of included quantitative studies, duration of PPP implementation, PPP models, role of public and private sector, distribution of included studies by aim of the study, indicators examined to determine the project success rate, results of implementation of PPP in PHC plans and results of qualitative studies).

Geographical Distribution of Included Studies

The results of the study showed that most studies have been conducted in low-income and lower-middle income countries. One of the possible reasons for this could be the economic situation of these countries, where the government utilize resources and the ability of the private sector to provide PHC services due to lack of financial resources. On the other hand, the inability of the government in providing quality services, providing trained human resources, expanding services in remote areas, and so on can be other reasons for using the private sector to cover the weaknesses in the public sector. Another possible reason is the lack of infrastructures and backgrounds to full privatization. Given the limited resources of the health system, especially in LMICs, the use of private sector resources seems inevitable. In the Lei et al study,24 which was a systematic review of PPP projects in the field of tuberculosis also most included studies were conducted in LMICs. The study also mostly included studies in South Asia and India.24 Unlike previous study, in the study by Grochtdreis et al,25 which conducted a systematic review study examining the cost-effectiveness of providing treatment services for depression disorders using PPPs, most studies were conducted in high-income countries. This may be due to the lack of access to cost information in low- and middle-income countries, whereas in developed countries this data may be available due to better information infrastructure.

Time Scattering of Included Studies

Since the present study was conducted in the fifth month of 2019, the number of included studies in 2018 and 2019 is lower than in previous years. Despite some fluctuations in the number of studies published in reviewed years, time scattering of included studies indicate that the publication trend of studies in the field of PPP implementation in PHC is incremental. One reason for this finding could be that the publication of articles on preliminary positive results has convinced governments that implementing PPP in PHC can be beneficial and promote this field, thereby governments have moved to implementing such plans. The findings of the study by Roehrich et al,26 which reviewed and analyzed about 1400 articles published during the past 2 decades, show that during this time, public sector policymakers have paid particular attention to the capabilities of the private sector in development, financing, and provision of services and infrastructure of the health system, so that, since 2006 there has been a significant jump in the number of articles published in the field of PPP. On the other hand, another reason for the increase in tendency to PPP may be the weakness of governments in providing services and the economic problems.

Study Design of Included Studies

According to the results, the most used study designs were cross-sectional, comparative, and before and after study. It seems, because of the nature of studies, which aimed at examining the results of PPP implementation, the above study designs are more appropriate. In the study by Roehrich et al,26 the case study approach was the main method of collecting data on PPP plans and comparing organizations. Meanwhile survey method was used in a small number of articles. Given the long-term nature of most PPP plans, it seems limited evidence of results in the form of longitudinal or time series studies have been published. In order to better reflect the success of PPP plans, it is recommended to use more longitudinal, process, and case-control studies.

Also, based on the results of the study, few economic evaluation studies have been conducted to assess the PPP success. As one of the drivers of PPP projects implementation is economic issues, the use of economic evaluation studies to determine the success of these types of projects can provide useful and effective information for researchers and executives. The number of mix method studies is also relatively low. Since mixed-method studies address different aspects of a subject and can better and more efficiently evaluate the success or failure of a project, it is better to use these studies to evaluate the success of PPP projects. On the other hand, the studies’ design was mostly cross-sectional and pre- and poststudy without control group, and few of studies were conducted as quasi-experimental (controlled). Since studies with controlled group are the best type of studies to accurately determine the impact of PPP implementation, it is recommended that researchers mostly use quasi-experimental (controlled) studies in future studies.

Duration of PPP Implementation

In some included studies, shortly after implementation of the PPP plan its success had been evaluated, which it is not possible to make a fair judgment about the success or failure of the plan after such short time period. When a PPP plan is implemented, a major change occurs in the system and adapting with new structure will take time. The public and private sectors need time to adjust and stabilize with new conditions, at such point, the actual performance can be measured. For this reason, it is better to make adequate time interval between project implementation and its evaluation. In the study of Grochtdreis et al (2015),25 the average time interval between implementation and evaluation the success of PPP projects, using the cost-effectiveness index, were ranged from 6 to 24 months.

Public-Private Partnership Models in Included Studies

One of the most important things that determine the assignment method, assigned functions, monitoring and evaluation method, how to pay to the private sector, and so on is the PPP model. Also, the used PPP model can be very helpful in conveying the experience gained from the plan and identifying its strengths and weaknesses. The results of present study showed that the model of PPP is less addressed in the included studies. One possible reason could be the authors’ purpose of writing the articles or reports, which may be to just provide a report of the results of an experience and therefore have paid less attention to detail. Another possible reason may be the lack of experience and technical knowledge of the authors in this field.

Role of Public and Private Sectors in Public-Private Partnership

The roles that the private sector can take on are varied and largely depend on the type of service that should be provided by this sector. In some cases, PPP plans are described based on roles that are assigned to the private sector. As expected, the results indicated that the role of private sector in implementation of PPP in PHC mostly is service provision. But the role of the public sector in service provision is still significant, and the main role of this sector, which is stewardship, has largely been ignored. Public sector need to reduce energy to provide services, and assign it to the private sector, and spend most of their time and energy on stewardship as its main task. In a review study by Dewan et al,27 which examines PPP plans implemented in India to control tuberculosis, stated that the role of government is to educate and supervise private companies providing tuberculosis-related care, while the role of the private sector is to provide services in accordance with public sector standards and criteria.27

The authors’ proposed pattern for implementing PPP plans in the health sector is that the government should focus more on governance tasks such as stewardship and supporting, and assign services provision to the private sector (Figure 10). According to this model, as we move from tasks such as service provision to governance tasks, such as stewardship, supporting and supervision, the role of the private sector becomes less and the role of the public sector becomes more prominent. In order for the government to perform its tasks properly, it must assign the lower-level duties to the private sector and spend most of its time and energy on stewardship and governance tasks. Also, under this model, some specific services can be provided by the public sector, which may decrease or increase depending on the capacity of the private sector and the existence of required infrastructures for providing these specific services in this sector, as well as the capacity of the public sector for monitoring and supporting. In some included studies, it is found that in implementation of PPP plans this pattern have not followed, which is not consistent with the nature of PPP.

Figure 10.

Pattern of responsibilities in public-private partnerships in health sector.

Distribution of Included Studies by Study Context and Aim of the Study

The most important achievements of PPP are improving the quality of service, service receivers’ satisfaction, access, utilization, and equity. Because it is expected that in areas such as the affluent and congested areas where the public sector lacks the willingness or ability for providing health services, through assigning this responsibility to the private sector access and utilization, and consequently, public satisfaction increased in these areas. Assigning health care provision in the areas of interest of private sector will increase the capacity and potential of the public sector to provide health services in deprived areas, which is a clear indication of equity in the health system. Likely, because governments, particularly in LMICs, have difficulties in providing services to urban marginalized areas and deprived and remote areas, health indicators are low in these areas, in implementation of PPP plans these areas have been mostly addressed, and may for this reason, indicators such as utilization, access and case detection were used to evaluate the success of PPP in PHC plans. On the other hand, these indicators are much easier to evaluate and manage, and more compatible with the nature of PHC. These indicators have also been widely used in various studies evaluating PPP in PHC plans.28-33 Therefore, it is suggested that researchers compare the rural and deprived areas with urban areas, or compare the status of these areas with the preplan conditions to evaluate the success rate of PPP plans.

Indicators Examined to Determine the Project Success Rate

Based on the results of this study, in most cases, the effect of project implementation on improvement of studied indicators was effective. As well, because the changes in primary health care could have significant impact on case detection rate and service delivery indicators, and because these indicators are easier and more objective to measure, these indicators are mostly used to monitor the PPP plans’ success. In the study of Lei et al,24 the indicators of DOTS utilization, case detection, treatment outcome, case management, costs, access and equity were used to measure the effectiveness of PPP plans, all of which were extracted in the present study. Also, in the study of Dewan et al27 in India, the case detection and treatment success rate has considered as the measures of effectiveness of provided services through PPP plan.

The impact of implementation of PPP plans on improving the cost analysis index is somewhat less than its impact on other indicators. This probably indicates that reviewed studies did not specify the costs of before implementation of plan precisely, and also the extraction of this information after implementation of the plan may has been erroneous. Another reason could be not choosing the right metrics to measure this indicator. It is also important how to collect data and calculate these indices. A study by Hatcher et al34 in Pakistan examined the unit cost of 2 rural primary health centers that had been assigned to a private company. The results of the study showed that the unit costs of these centers were higher than expected.34 It is suggested that accurate indicators that reflect changes in this sector be selected for accurate monitoring of health system performance, and the data on these indicators routinely collected, not just for research or cross-sectional review.

The results also show that indicators of service quality, satisfaction of service receivers and providers, and equity have less used to evaluate the success of PPP plans. Indicators of service quality and satisfaction are predictors of people’s utilization of PHC, which can lead to equity. Therefore, because these indicators are more in line with the nature of PHC, it is recommended that in the future these indicators be used more to evaluate the impact of PPP implementation.

Results of Implementation of PPP in PHC by the Type of Assigned Services

According to the results of the study, most of the PPP projects has implemented in the field of TB related services delivery, which has greatly led to improve these services. The lowest rates of PPP plan were implemented in the field of disease surveillance, nutrition, reproductive health, gastroenteritis, elderly care, and mental health, which should be given more attention due to the importance of these areas in PHC. One of the possible reasons for less implementation of PPP plans in these areas could be the inability or unwillingness of the private sector to participate in these areas, where the public sector required to provide the preconditions (such as incentive packages, private sector empowerment, precise monitoring and evaluation criteria, etc) for assigning these services. In the study of Lei et al,24 the success rate of PPP projects in the field of tuberculosis services was about 65%, which is lower than that obtained in the present study. One reason for this may be that in the mentioned study, tuberculosis-related services have been examined in all sectors of the health system (laboratories, inpatient services, imaging, etc), but in the present study services that provided in PHC have been examined.

As pointed out in the time scattering section, it seems that due to the positive results of implementation of PPP projects, the acceptance of these plans has increased. The results have also shown that most of these projects have had a significant positive impact on PHC services provision. The effectiveness of these plans in the field of maternal and child care and vaccination was less than in other areas, which may be due to the lack of public awareness or cultural barriers to receiving these services.

Results of Qualitative Studies

The results showed that PPP plans can have different benefits. To take advantage of these benefits, it is recommended that the executors of these plans make the necessary arrangements, such as studying the existing conditions and contexts, and providing the necessary infrastructure before the implementation. Notification and informing the public about these benefits can also get the support of the community and authorities. In a review study by Hernandez-Aguado and Zaragoza,35 the benefits and requisites of using PPP in health promotion have been examined and it has been concluded that PPP enhances the capacity and potential of health services provision, increases attention to health in all policies, increases self-control, and improves the quality of services.35 In included qualitative studies, disadvantages of the PPP plans were less than the benefits, which may indicate a positive outlook to such projects, which has resulted from the positive results of these plans in recent years.

The results of the present study showed that the achievements of PPP in PHC plans were also positively evaluated, but some failures were noted. In a qualitative study conducted by Gasparinene et al36 in Lithuania with the aim of examining the experts’ views on the factors influencing the use of outsourcing in public health services, and the factors affecting cost savings after outsourcing, the results showed that the main factors that lead to the selection of outsourcing in public health care are lower cost, access to new technologies, and better quality of service. The results also indicated that outsourcing could lead to a significant reduction in the cost of noncore activities and the cost of investing in resources and storage.36

One of the most important issues to consider in PPP plans, is the obstacles and challenges of implementing such plans. The results of present study illustrate different challenges in implementing PPP in PHC projects which one of the most important of them is organizational barriers. One possible reason for the organizational barriers is the lack of readiness in public sector to implement such plans. To eliminate these barriers, it is recommended that all aspects that influence the PPP implementation be considered before implementing these plans so that through proper planning barriers can be solved before or during the implementation of the plan. For example, the resources needed to execute the plan, including human resources, finance, physical space, experts training in the field of PPP plans, and son, should be provided before implementation. Also, one of the solutions to identifying and addressing challenges is to implement the project in a smaller, pilot scale, because doing so will help identify many of the challenges and barriers and take action to address them before the project is widely implemented. It seems that all sections of society and public organizations should be involved in the process of implementing PPP in PHC plans in order to remove the existing challenges such as cultural and infrastructural barriers.

Some of the qualitative results showed different and sometimes conflicting views on PPP plans. One of the possible reasons for this may be the implementation of these projects in different countries with different context. Therefore, after studying the experiences of different countries and regions, countries should design a PPP plan tailored to their national and local conditions.

Application in LMICs

The results of the present study show that the PPP policy in PHC is more considered in LMICs than in high-income countries. Therefore, the results of this study are inherently more applicable to LMICs. The present study provides a comprehensive overview of PPP experiences in PHC, and provides relatively comprehensive information, evidence, and information for health authorities and policymakers in LMICs. One of the challenges of PPP plans, especially in developing countries, is the lack of rich information to judge about the success of PPP plans. To overcome this, it is better to define some indexes for determining the success rate of the plan, and design the mechanisms to collect the relevant data, or even include it in the PPP contracts as one of the private sector’ duties. On the other hand, good design and implementation of a PPP plan does not ensure its success, but the success of such plans requires continuous monitoring and evaluation to identify possible barriers and challenges as well as facilitating factors. Because of political unsustainability that sometimes lies in developing countries, it seems that applying civil pressures is critical to prevent reforms from stopping. For applying civil pressures, attracting the support of people and stakeholders seems to be essential. Creating management capability in public sector for monitoring and evaluating the performance of private sector is one of the most important requirements for implementing PPP plans in developing countries. This requires development of proper indexes and objectives, establishment of a targeted and accurate monitoring and evaluation program, development of high-precision tools, and finally pay-for-performance based on the results of monitoring and evaluations. One of the necessary and useful tools in this area is implementation and use of information systems that can help improve the accuracy and precision of monitoring and evaluation, and payment based on it. Based on developing such a structure, specialized and independent private companies’ capacity can be applied to measure and improve quality.

It should be noted that PPP’s success in health sector is largely influenced by its design and the context in which it implemented. To overcome this, each country should design and implement its own PPP models which is adapted to country’s national and local conditions or context.

Recommendations

The results show that while PPP plans is regarded as an essential and effective way to provide social justice, implement family practice plan, and achieve universal health care, challenges such as political and financial unsustainability, delay in reimbursements, lack of stakeholder cooperation, and lack of continuous quality of services evaluation have had negative effect on the PPP plans. Overcoming challenges, more success and expanding this plan require accepting the private sector as one of the main sources of the health system, and require more support from authorities of health, national and local government. It is recommended that designers and executers of these plans adopt strategies in order to ensure adequate and timely funding. One of the solutions is attracting the cooperation of insurance companies. On the other hand, successful formulation and start-up of the plan does not guarantee its success, so a mechanism should be designed to monitor and modify the plan. The last proposal is to involve stakeholders in the process of managing and organizing the implementation of the plan, so that a common language create among all stakeholders.

Limitations

Overall, the information provided in the reviewed studies was incomplete. For example, many studies did not address the project implementation context (urban or rural), PPP model, role of the public and private sector, sample size, study design, and so on. It is better to refer to all aspects when conducting a study in the field of PPP plans (including setting (urban/rural/immigrant/suburb/etc), aim of study, study design, participants (governmental and nongovernmental), Period after implementation of PPP plan, Roles/task of parties (public and private), PPP model, Indicators have used to evaluate the success of PPP plan, data collection method), to better evaluate the validity of the results and the reasons for success or failure.

Since most included studies were not clear on the methodology of the study, there were 2 ways for the authors: either the methodology should not be reported or the method of study should be determined by the research team based on the information presented in the article. If these cases were not reported, the final report would be incomplete, so the research team inevitably reviewed the studies and determined the study design based on the provided information, which may have caused errors in some cases.

Conclusions

The results of the present study provide useful information on the experiences of different countries, and on the aspects and dimensions of PPP in the of PHC services provision. Given the significant achievements of PPP in PHC, limited access to countries’ experiences, increasing importance of PHC, as well as weaknesses of governments to provide these services, policy makers and authorities of health system in different countries, especially LMICs, could use this strategy as an appropriate approach to improve PHC performance.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, Annex_1 for Public-Private Partnership Policy in Primary Health Care: A Scoping Review by Jafar Sadegh Tabrizi, Saber Azami-aghdash and Hojatolah Gharaee in Journal of Primary Care & Community Health

Supplemental material, Annex_2 for Public-Private Partnership Policy in Primary Health Care: A Scoping Review by Jafar Sadegh Tabrizi, Saber Azami-aghdash and Hojatolah Gharaee in Journal of Primary Care & Community Health

Supplemental material, Annex_3 for Public-Private Partnership Policy in Primary Health Care: A Scoping Review by Jafar Sadegh Tabrizi, Saber Azami-aghdash and Hojatolah Gharaee in Journal of Primary Care & Community Health

Supplemental material, Annex_4 for Public-Private Partnership Policy in Primary Health Care: A Scoping Review by Jafar Sadegh Tabrizi, Saber Azami-aghdash and Hojatolah Gharaee in Journal of Primary Care & Community Health

Supplemental material, Biographic_sketch for Public-Private Partnership Policy in Primary Health Care: A Scoping Review by Jafar Sadegh Tabrizi, Saber Azami-aghdash and Hojatolah Gharaee in Journal of Primary Care & Community Health

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was part of PhD thesis funded and supported by Tabriz University of Medical Sciences and Tabriz Health Services Management Research Center under grant number (TBZMED.REC.1397.597).

ORCID iDs: Hojatolah Gharaee  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9354-4175

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9354-4175

Saber Azami-aghdash  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1244-359X

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1244-359X

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. Franken M, Koolman X. Health system goals: a discrete choice experiment to obtain societal valuations. Health Policy. 2013;112:28-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q. 2005;83:457-502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Papp R, Borbas I, Dobos E, et al. Perceptions of quality in primary health care: perspectives of patients and professionals based on focus group discussions. BMC Fam Pract. 2014;15:128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. World Health Organization. The World Health Report 2008: Primary Health Care (Now More Than Ever). World Health Organization; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Davies P. The Role of the Private Sector in the Context of Aid Effectiveness: Consultative Findings Document, Final Report. Organization for Cooperation and Development; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kraak VI, Harrigan PB, Lawrence M, Harrison PJ, Jackson MA, Swinburn B. Balancing the benefits and risks of public–private partnerships to address the global double burden of malnutrition. Public Health Nutr. 2012;15:503-517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gharaee H, Rezapour R, Derakhshani N, Ghojazadeh M, Azami-Aghdash S. Developing public-private partnership framework for managing adverse health effects of environmental disaster (a case study of lake Urmia, Iran). Published February 4, 2020. Accessed July 4, 2020 https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs-13130/v1

- 8. Zheng J, Roehrich JK, Lewis MA. The dynamics of contractual and relational governance: evidence from long-term public–private procurement arrangements. J Purchasing Supply Manag. 2008;14:43-54. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Vian T, McIntosh N, Grabowski A, Nkabane-Nkholongo EL, Jack BW. Hospital public–private partnerships in low resource settings: perceptions of how the Lesotho PPP transformed management systems and performance. Health Syst Reform. 2015;1:155-166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Azami-Aghdash S, Sadeghi-Bazargani H, Saadati M, Mohseni M, Gharaee H. Experts’ perspectives on the application of public-private partnership policy in prevention of road traffic injuries. Chin J Traumatol. 2020;23:152-158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Osborne S. Public-Private Partnerships: Theory and Practice in International Perspective. Routledge; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gharaee H, Tabrizi JS, Azami-Aghdash S, Farahbakhsh M, Karamouz M, Nosratnejad S. Analysis of public-private partnership in providing primary health care policy: an experience from Iran. J Prim Care Community Health. 2019;10:2150132719881507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Arksey H, O’’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8:19-32. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Int J Surg. 2010;8:336-341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA Statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:264-269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. PRISMA Group. Reprint—preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA Statement. Phys Ther. 2009;89:873-880. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Canadian Council for Public-Private Partnerships. Public-Private Partnerships. A Guide for Municipalities. Canadian Council for Public-Private Partnerships; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 18. The World Bank Group. Public-Private Partnership Reference Guide 3.0. World Bank Publications; 2017:238. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Campos CJ. Content analysis: a qualitative data analysis tool in health care [in Portuguese]. Rev Bras Enferm. 2004;57:611-614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Liamputtong P. Qualitative data analysis: conceptual and practical considerations. Health Promot J Austr. 2009;20:133-139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Seers K. Qualitative data analysis. Evid Based Nurs. 2012; 15:2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Smith J, Firth J. Qualitative data analysis: the framework approach. Nurse Res. 2011;18:52-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. The World Bank. World Bank Country and lending groups. Accessed July 4, 2020 https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519

- 24. Lei X, Liu Q, Escobar E, et al. Public-private mix for tuberculosis care and control: a systematic review. Int J Infect Dis. 2015;34:20-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Grochtdreis T, Brettschneider C, Wegener A, et al. Cost-effectiveness of collaborative care for the treatment of depressive disorders in primary care: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0123078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Roehrich J, Lewis M, George G. Are public-private partnerships a healthy option? A systematic review“”. Soc Sci Med. 2014;113:110-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dewan PK, Lal SS, Lonnroth K, et al. Improving tuberculosis control through public-private collaboration in India: literature review. BMJ. 2006;332:574-578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Al-Jazaeri A, Ghomraoui F, Al-Muhanna W, Saleem A, Jokhadar H, Aljurf T. The impact of healthcare privatization on access to surgical care: cholecystectomy as a model. World J Surg. 2017;41:394-401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Alkhamis AA. Critical analysis and review of the literature on healthcare privatization and its association with access to medical care in Saudi Arabia. J Infect Public Health. 2017;10:258-268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. De Costa A, Vora KS, Ryan K, Raman PS, Santacatterina M, Mavalankar D. The state-led large scale public private partnership “Chiranjeevi Program” to increase access to institutional delivery among poor women in Gujarat, India: how has it done? What can we learn? PLoS One. 2014;9:e95704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Dutta S, Lahiri K. Is provision of healthcare sufficient to ensure better access? An exploration of the scope for public-private partnership in India. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2015;4:467-474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Loevinsohn B, Ul Haq I, Couffinhal A, Pande A. Contracting-in management to strengthen publicly financed primary health services—the experience of Punjab, Pakistan. Health Policy. 2009;91:17-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gharaee H, Tabrizi JS, Azami-Aghdash S, Farahbakhsh M, Karamouz M, Nosratnejad S. Analysis of public-private partnership in primary health care: an experience from Iran. J Prim Care Community Health. 2019;10:215013271988150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hatcher P, Shaikh S, Fazli H, Zaidi S, Riaz A. Provider cost analysis supports results-based contracting out of maternal and newborn health services: an evidence-based policy perspective. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hernandez-Aguado I, Zaragoza G. Support of public–private partnerships in health promotion and conflicts of interest. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e009342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gaspareniene L, Remeikiene R, Startiene G. Outsourcing as a measure seeking for cost reduction in public health care sector: Lithuanian Case. Paper presented at: 8th International Scientific Conference “Business and Management 2014”; May 15-16, 2014; Vilnius, Lithuania. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, Annex_1 for Public-Private Partnership Policy in Primary Health Care: A Scoping Review by Jafar Sadegh Tabrizi, Saber Azami-aghdash and Hojatolah Gharaee in Journal of Primary Care & Community Health

Supplemental material, Annex_2 for Public-Private Partnership Policy in Primary Health Care: A Scoping Review by Jafar Sadegh Tabrizi, Saber Azami-aghdash and Hojatolah Gharaee in Journal of Primary Care & Community Health

Supplemental material, Annex_3 for Public-Private Partnership Policy in Primary Health Care: A Scoping Review by Jafar Sadegh Tabrizi, Saber Azami-aghdash and Hojatolah Gharaee in Journal of Primary Care & Community Health

Supplemental material, Annex_4 for Public-Private Partnership Policy in Primary Health Care: A Scoping Review by Jafar Sadegh Tabrizi, Saber Azami-aghdash and Hojatolah Gharaee in Journal of Primary Care & Community Health

Supplemental material, Biographic_sketch for Public-Private Partnership Policy in Primary Health Care: A Scoping Review by Jafar Sadegh Tabrizi, Saber Azami-aghdash and Hojatolah Gharaee in Journal of Primary Care & Community Health