Abstract

Purpose:

Electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes) could have a multifaceted effect on public health by changing the likelihood that: (a) non-smokers and non-users of marijuana subsequently transition to cigarette and marijuana use, respectively, and/or: (b) cigarette smokers subsequently quit smoking. We analyzed data from a longitudinal study of Hispanic young adults in Los Angeles, California to determine whether e-cigarette use is associated with subsequent cigarette or marijuana use over a one-year period.

Methods:

Survey data were collected from 1332 Hispanic young adults (59% female, mean age = 22.7 years, SD = 0.39 years) in 2014 and 2015. Logistic regression analyses examined the association between e-cigarette use in 2014 and cigarette/marijuana use in 2015, controlling for age, sex, and other substance use.

Results:

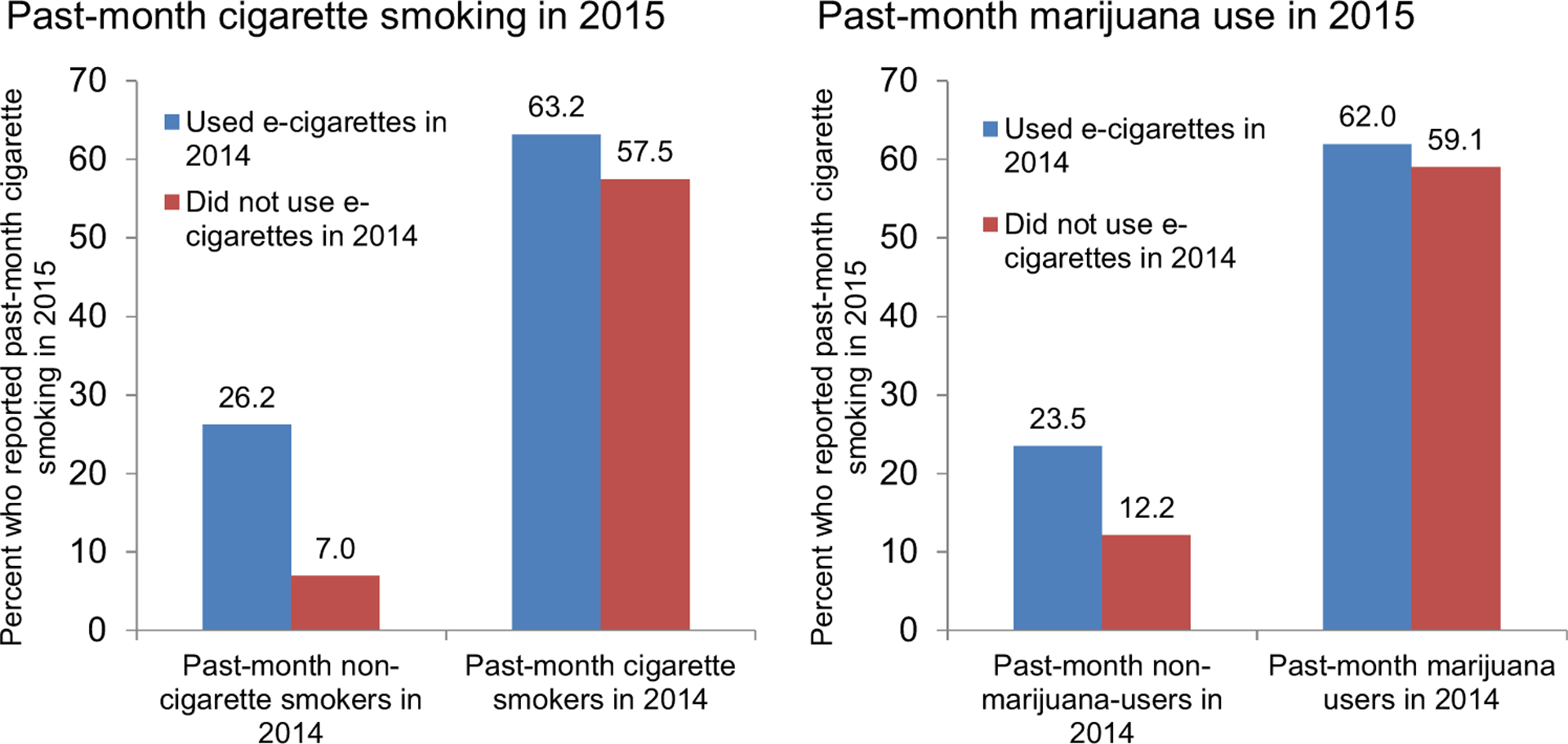

In 2014, prevalence of past-month use was 9% for e-cigarettes, 21% for cigarettes, and 23% for marijuana. Among past-month cigarette nonsmokers in 2014, those who were past-month e-cigarette users in 2014 were over 3 times more likely to be past-month cigarette smokers in 2015, compared with those who did not report past-month e-cigarette use in 2014 (26% vs. 7%; OR = 3.32, 95% CI = 1.55, 7.10). Among past-month marijuana non-users in 2014, those who were past-month e-cigarette users in 2014 were nearly 2 times more likely to be past-month marijuana users in 2015 (24% vs. 12%;OR = 1.97, 95% CI = 1.01, 3.86). Among past-month cigarette and marijuana users in 2014, e-cigarette use in 2014 was not associated with a change cigarette and marijuana use, respectively, in 2015.

Conclusions:

Among Hispanic young adults, e-cigarettes could increase the likelihood of transitioning from non-user to user of cigarettes or marijuana and was not associated with smoking cessation.

Keywords: Electronic cigarettes, Marijuana, Hispanic, Young adults

1. Introduction

Although electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes) have been promoted as a safer alternative to combustible cigarettes (McNeill et al., 2015), they could adversely affect public health if they increase the likelihood that nonsmokers will begin using cigarettes or other drugs (Alawsi et al., 2015). E-cigarettes are more socially acceptable than combustible cigarettes and could therefore be attractive to people who would ordinarily be deterred by social norms from using combustible cigarettes (Leventhal et al., 2015). Adolescents with a genetic and/or environmental liability to experiment with substance use might begin with e-cigarettes and thereby obtain access to peer groups and social environments that encourage substance use, ultimately leading to experimentation with other substances with more adverse health effects (Vanyukov et al., 2012). Once users experience physiological and social reinforcement from e-cigarette use, they might be more likely to transition to combustible cigarettes (Schneider and Diehl, 2015). Studies of adolescents and young adults have found that cigarette nonsmokers who have used e-cigarettes are at increased risk for progressing to cigarette smoking, relative to those who have not used e-cigarettes (Cardenas et al., 2016; Gmel et al., 2016; Leventhal et al., 2015; Primack et al., 2015; Wills et al., 2016).

Among current cigarette smokers, switching to e-cigarettes could reduce harm if it leads to sustained cessation or reduction of cigarette use. The field has not yet achieved consensus about whether e-cigarettes are effective for combustible cigarette cessation; some studies have shown cessation effects, but others have not (Orr and Asal, 2014). Few studies have examined long-term cessation effects-whether cigarette smokers who switch to e-cigarettes continue to use only e-cigarettes, or whether they become dual users of both combustible cigarettes and e-cigarettes.

It is also possible that e-cigarettes increase the likelihood of using other drugs that can be inhaled or vaped, such as marijuana. Experimentation with e-cigarettes can provide an opportunity to purchase and learn how to use vaping equipment (e.g., box mods, batteries, chargers, and flavored e-juices), which could facilitate the transition from vaping nicotine to vaping other drugs such as marijuana (Giroud et al., 2015). Vaping nicotine could also introduce people to the pro-vaping culture through vape shops, vaping websites, and social media, which typically are supportive of both nicotine vaping and marijuana vaping (Budney et al., 2015; Gostin and Glasner, 2014). The nicotine in e-cigarettes also might prime brain responses to other drugs (Kandel and Kandel, 2014) (Fig.1).

Fig. 1.

2015 Substance use among 2014 e-cigarette users and non-users.

It is especially important to investigate the impact of e-cigarettes on vulnerable populations including young adults-who currently report the highest prevalence of e-cigarette use (McMillen et al., 2015), and ethnic minorities-who have historically suffered tobacco-related health disparities and are disproportionately exposed to tobacco product marketing (Fagan et al., 2007). Although e-cigarettes were initially most popular among non-Hispanic Whites (King et al., 2013), e-cigarette use among Hispanic adolescents and young adults has increased in recent years (Saddleson et al., 2015) and in some samples has surpassed the rate among Whites (Bostean et al., 2015; Leventhal et al., 2015). If e-cigarettes facilitate progression to habitual cigarette and/or marijuana use, they could exacerbate health disparities among Hispanics.

We analyzed data from a longitudinal study of Hispanic young adults in Los Angeles, California to examine the effects of e-cigarette use on cigarette and marijuana use one year later. We hypothesized that (1) among past-month cigarette nonsmokers, those who used e-cigarettes would be at increased risk of progressing to past-month cigarette smoking in the next year (consistent with the common liability model); (2) among past-month cigarette smokers, those who used e-cigarettes would be less likely to be smoking combustible cigarettes one year later (consistent with the notion that e-cigarettes facilitate smoking cessation). We also examined whether these patterns existed for marijuana use, hypothesizing that (3) among past-month marijuana non-users, those who used e-cigarettes would be at increased risk of becoming past-month marijuana users in the next year (Table 1).

Table 1.

Odds ratios for being a past-month cigarette smoker or marijuana user in 2015.

| Odds ratios for being a past-month cigarette smoker in 2015 | Odds ratios for being a past-month marijuana user in 2015 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cigarette nonsmokers in 2014 (N = 1056) | Cigarette smokers in 2014 (N = 276) | Marijuana nonusers in 2014 (N = 1028) | Marijuana users in 2014 (N = 304) | |||||

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| Age (years) | 1.18 | 0.65, 2.17 | 1.07 | 0.58,2.00 | 1.23 | 0.78, 1.97 | 0.79 | 0.44, 1.42 |

| Female (vs. male) | 0.33 | 0.20, 0.52 | 0.50 | 0.30, 0.82 | 1.14 | 0.77, 1.69 | 0.61 | 0.38, 0.98 |

| Past-month alcohol use in 20141 | 2.33 | 0.91,5.96 | 1.52 | 0.42, 5.60 | 1.71 | 0.91,3.20 | 0.25 | 0.05,1.20 |

| Past-month cigar use in 20141 | 1.92 | 0.30,12.39 | 0.68 | 0.34,1.36 | 1.91 | 0.72, 5.03 | 0.63 | 0.21,1.89 |

| Past-month little cigar use in 20141 | 1.09 | 0.19,6.35 | 1.17 | 0.62,2.23 | 0.82 | 0.30, 2.25 | 1.52 | 0.64,3.61 |

| Past-month hookah use in 20141 | 1.88 | 0.69,5.08 | 0.80 | 0.43,1.48 | 1.09 | 0.51,2.34 | 1.00 | 0.43,2.29 |

| Past-month smokeless tobacco use in 20141 | 3.44 | 0.52,22.69 | 1.13 | 0.31,4.18 | 0.67 | 0.08,5.55 | 0.84 | 0.17,4.19 |

| Past-month e-cigarette/marijuana use in 20141 | 3.32 | 1.55, 7.10 | 1.31 | 0.73, 2.36 | 1.97 | 1.01,3.86 | 1.05 | 0.54, 2.01 |

1 = yes, 0 = no.

2. Material and methods

Survey data were obtained from 1332 Hispanic young adults who participated in Project RED, a longitudinal study of cultural factors and substance use. Participants were originally recruited when they were 9th-grade students attending Los Angeles area high schools in 2005 and were followed approximately annually through 2015. The data reported in this article is from the 2014 and 2015 surveys, when Project RED added questions about e-cigarette use. Details about the initial recruitment and follow-up are described by Unger (2014). The Project RED young adult panel includes 1445 Hispanic young adults who originally participated in the high school survey. Participants were contacted by email, text message, phone, and/or social media in 2014 and 2015 and invited to complete online surveys. The sample for this analysis included all participants who completed surveys in both 2014 and 2015 (N = 1332, 92% of the young adult panel).

2.1. Measures

Participants’ use of combustible cigarettes, e-cigarettes, and marijuana were classified based on their use in the past month (yes/no). Covariates included age, sex, and past-month use of alcohol and other tobacco products (hookah, cigars, little cigars, smokeless tobacco).

2.2. Statistical analysis

The sample was stratified into two groups according to 2014 combustible cigarette use: past-month cigarette nonsmokers and past-month cigarette smokers. Within each group, a logistic regression analysis was conducted to determine the likelihood of being a past-month cigarette smoker in 2015. The main predictor variable was past-month e-cigarette use in 2014. Similarly, the sample was stratified into two groups according to 2014 past-month marijuana use: past-month marijuana users and past-month marijuana nonusers. Within each group, a logistic regression analysis was conducted to determine the likelihood of being a past-month marijuana user in 2015, with past-month e-cigarette use in 2014 as the main predictor.

3. Results

The participants’ mean age in 2014 was 22.7 years (SD = 0.39 years). All participants identified as Hispanic, and 59% were female.

3.1. Is e-cigarette use associated with subsequent cigarette use among cigarette nonsmokers?

Among the participants who were past-month cigarette nonsmokers in 2014, (N = 1056, 79% of the sample), 42 (4%) reported past-month e-cigarette use in 2014. Among cigarette nonsmokers who used e-cigarettes in 2014, 26% had become past-month cigarette smokers in 2015. Among those who had not used e-cigarettes in 2014, only 7% had become past-month cigarette smokers in 2015. After adjusting for covariates, those who used e-cigarettes in 2014 were over 3 times more likely to be past-month cigarette smokers in 2015 (OR = 3.32, 95% CI = 1.55, 7.10).

3.2. Is e-cigarette use associated with subsequent marijuana use among marijuana non-users?

Among the participants who were past-month marijuana non-users in 2014 (N = 1028, 77% of the sample), 68 (7%) reported past-month e-cigarette use in 2014. Among those who reported past-month e-cigarette use in 2014, 24% reported past-month marijuana use in 2015, compared with only 12% of those who did not report e-cigarette use in 2014. After adjusting for covariates, those who had used e-cigarettes in 2014 were nearly twice as likely to be past-month marijuana users in 2015 (OR = 1.97, 95% CI = 1.01, 3.86).

3.3. Is e-cigarette use associated with subsequent cessation of cigarettes and marijuana use among cigarette smokers and marijuana users, respectively?

Among participants who were past-month cigarette smokers in 2014 (N = 276, 21% of the sample), 76 (28%) reported past-month e-cigarette use in 2014. Among those who reported past-month e-cigarette use in 2014, 63% were still past-month cigarette smokers in 2015. Among those who did not report past-month e-cigarette use in 2014, 58% were still past-month cigarette smokers in 2015. After adjusting for covariates, cigarette smokers who used e-cigarettes in 2014 were not significantly more or less likely to remain cigarette smokers in 2015 (OR = 1.31, 95% CI = 0.73, 2.36). Among 2014 marijuana users, 2014 e-cigarette use was not associated with 2015 marijuana use.

4. Discussion

In this longitudinal study of Hispanic young adults, past-month cigarette nonsmokers who used e-cigarettes were more likely to have become past-month cigarette smokers one year later. This is consistent with results from previous studies of adolescents (Leventhal et al., 2015; Wills et al., 2016), which raise concerns about young people transitioning from use of e-cigarettes to combustible cigarette use. Young adults who have been deterred from cigarette smoking by negative social norms and tobacco control messages may remain vulnerable to experimenting with e-cigarettes, which have more favorable social norms (Schneider and Diehl, 2015). This initial experience with nicotine, if it is perceived as positive, could increase willingness to try other nicotine products, ultimately leading to nicotine dependence and habitual use of combustible cigarettes. However, it is encouraging that only 4% of the cigarette nonsmokers used e-cigarettes. Continued surveillance of recreational e-cigarette use among non-smokers is warranted for gauging the overall public impact of e-cigarette-to-cigarette transitions.

Past-month marijuana non-users who used e-cigarettes were more likely to have become past-month marijuana users one year later. Experimentation with e-cigarettes could lead to familiarity with vaping equipment, curiosity about the subjective effects of other drugs, and entry into a “vaping culture”-all of which could increase the risk of marijuana use through marijuana vaping or use of marijuana via smoking or other methods of administration. This could add to the potential adverse population-level public health effects of e-cigarettes.

If e-cigarettes facilitated smoking cessation, one would expect that cigarette smokers who also used e-cigarettes would be more likely to quit combustible cigarettes, relative to those who did not use e-cigarettes. However, our findings did not support this hypothesis. Current cigarette smokers who also used e-cigarettes were not any more likely to be cigarette nonsmokers one year later. Instead, they were likely to have remained dual users of both products one year later or to have returned to exclusive cigarette smoking. Of course, it is possible that the participants who were initially using both cigarettes and e-cigarettes were more nicotine dependent than those who were using only one product. Further research is needed to determine whether use of multiple tobacco products is a cause or a consequence of higher nicotine dependence, or both, and if cessation-enhancing effects of e-cigarette use are seen among certain subgroups of the population of young adult smokers (e.g., those motivated to quit).

4.1. Limitations

This quasi-experimental study does not permit causal inferences. In the absence of experimental studies, the current findings are consistent with the hypothesis that e-cigarettes increase the likelihood of combustible cigarette and marijuana use, and that e-cigarette use does not produce sustained cessation of combustible cigarettes. These findings are based on a small number of participants who initiated cigarette or marijuana use during a one-year period; therefore they should be interpreted cautiously. The Project RED emerging adult panel includes individuals who self-reported as Hispanic, attended one of 8 Los Angeles high schools in 2005–2007, and agreed to participate in annual surveys in young adulthood, which impacts generalizability. Self-reports were not validated biochemically. Unfortunately, we did not assess frequency or amount of cigarette, e-cigarette, or marijuana use within the past month, so it is possible that our findings reflect one-time or occasional use rather than habitual use. Also, the substance that the e-cigarette users were vaping was not recorded nor was the method of marijuana administration, leaving unclear the relative roles of the substance and vehicle (e.g. vaping vs. smoking) in the associations reported herin. The survey did not include personality factors such as impulsivity, rebelliousness, or sensation seeking, which could have confounded the associations between e-cigarette use and other substance use.

4.2. Conclusions

Despite these limitations, these findings raise concerns that the widespread availability and positive social norms that may be increasing the popularity of e-cigarettes could ultimately encourage cigarette smoking among cigarette nonsmokers and encourage marijuana use among marijuana non-users. For vulnerable populations such as Hispanic young adults, this trend could increase the burden of tobacco-related disease and encourage experimentation with other drugs. Future analyses of the public health impact of e-cigarettes should take these effects into account. Even if e-cigarettes are safer than combustible cigarettes, their public health advantage will be mitigated if they play a role in the uptake of tobacco and other substance use.

Role of funding source

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant 5R01DA016310).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- Alawsi F, Nour R, Prabhu S, 2015. Are e-cigarettes a gateway to smoking or a pathway to quitting? Br. Dent. J 219, 111–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bostean G, Trinidad DR, McCarthy WJ, 2015. E-cigarette use among never-smoking California students. Am. J. Public Health 105, 2423–2425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budney AJ, Sargent JD, Lee DC, 2015. Vaping cannabis (marijuana): parallel concerns to e-cigs? Addiction 110, 1699–1704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardenas VM, Evans VL, Balamurugan A, Faramawi MF, Delongchamp RR, Wheeler JG, 2016. Use of electronic nicotine delivery systems and recent initiation of smoking among US youth. Int. J. Public Health, in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagan P, Moolchan ET, Lawrence D, Fernander A, Ponder PK, 2007. Identifying health disparities across the tobacco continuum. Addiction 102 (Suppl. 2), 5–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giroud C, de Cesare M, Berthet A, Varlet V, Concha-Lozano N, Favrat B, 2015. E-cigarettes: a review of new trends in cannabis use. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 12, 9988–10008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gmel G, Baggio S, Mohler-Kuo M, Daeppen JB, Studer J, 2016. E-cigarette use in young Swiss men: is vaping an effective way of reducing or quitting smoking? Swiss Med. Wkly 146, 14271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gostin LO, Glasner AY, 2014. E-cigarettes, vaping, and youth. JAMA 312, 595–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandel DB, Kandel ER, 2014. A molecular basis for nicotine as a gateway drug. N. Engl. J. Med 371, 2038–2039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King BA, Alam S, Promoff G, Arrazola R, Dube SR, 2013. Awareness and ever-use of electronic cigarettes among U.S. adults 2010–2011. Nicotine Tob. Res 15, 1623–1627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal AM, Strong DR, Kirkpatrick MG, Unger JB, Sussman S, Riggs NR, Stone MD, Khoddam R, Samet JM, Audrain-McGovern J, 2015. Association of electronic cigarette use with initiation of combustible tobacco product smoking in early adolescence. JAMA 314, 700–707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMillen RC, Gottlieb MA, Shaefer RM, Winickoff JP, Klein JD, 2015. Trends in electronic cigarette use among u.s. adults: use is increasing in both smokers and nonsmokers. Nicotine Tob. Res 17, 1195–1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeill A, Brose LA, Calder R, Hitchman SC, Hajek P, McRobbie H, 2015. E-Cigarettes: An Evidence Update. Public Health England, London. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orr KK, Asal NJ, 2014. Efficacy of electronic cigarettes for smoking cessation. Ann. Pharmacother 48, 1502–1506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Primack BA, Soneji S, Stoolmiller M, Fine MJ, Sargent JD, 2015. Progression to traditional cigarette smoking after electronic cigarette use among US adolescents and young adults. JAMA Pediatr. 169, 1018–1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saddleson ML, Kozlowski LT, Giovino GA, Hawk LW, Murphy JM, MacLean MG, Goniewicz ML, Homish GG, Wrotniak BH, Mahoney MC, 2015. Risky behaviors, e-cigarette use and susceptibility of use among college students. Drug Alcohol Depend. 149, 25–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider S, Diehl K, 2015. Vaping as a catalyst for smoking? An initial model on the initiation of electronic cigarette use and the transition to tobacco smoking among adolescents. Nicotine Tob. Res (in press). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unger JB, 2014. cultural influences on substance use among Hispanic adolescents and young adults: findings from Project RED. Child Dev. Perspect 8, 48–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanyukov MM, Tarter RE, Kirillova GP, Kirisci L, Reynolds MD, Kreek JJ, Conway KP, Maher BS, Iacono WG, Bierut L, Neale MC, Clark DB, Ridenour TA, 2012. Common liability to addiction and gateway hypothesis: theoretical empirical, and evolutionary perspective. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1235, S3–S17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Knight R, Sargent JD, Gibbons FX, Pagano I, Williams RJ, 2016. Longitudinal study of e-cigarette use and onset of cigarette smoking among high school students in Hawaii. Tob. Control (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]