Abstract

Progranulin (PGRN) is a secreted growth factor involved in pleiotropic functions, particularly angiogenesis. A distinctly different placental expression of PGRN has been reported between normal pregnancies and pregnancies with complications, such as pre-eclampsia or fetal growth restriction. However, the role of PGRN in placental vascular development remains to be elucidated. In the present study, PGRN-knockout mice (PGRN−/−) were used to investigate the role of PGRN in the development of placental blood vessels and placental formation. Placental weights and pup body weights were significantly lower in the PGRN−/− mice compared with the wild-type mice. Reduced labyrinthine layer areas and aberrant vascularization were also observed via hematoxylin and eosin staining of PGRN−/− mice at embryonic day 14.5 (E14.5) and E17.5. In addition, the morphological data obtained via immunohistochemistry, immunofluorescence staining and western blotting demonstrated decreased expression levels of the blood vessel markers α-smooth muscle actin and CD31 in PGRN−/− placentas. Furthermore, vasodilator endothelial nitric oxide synthase was reduced in the PGRN−/− placenta. These results indicated that PGRN serves an essential role in the normal angiogenesis of the placental labyrinth in mice.

Keywords: progranulin, angiogenesis, placenta, mice, vascularization

Introduction

The placenta is a vital organ that mediates maternal-fetal exchange of nutrients and waste (1). Placental development is accompanied by extensive angiogenesis, particularly in the labyrinth, the key site of fetomaternal interaction that contains both fetal and maternal blood vessels (2). In mice, the labyrinthine vasculature elongates and expands to meet the needs of the growing fetus from embryonic day (E)14.5 until the end of gestation (3,4). The initial stages of angiogenesis result in leaky, poorly perfused and easily ruptured vessels (5). The developing network is repeatedly pruned and remodeled via the fusion and regression of existing vessels, until an extensive and highly-branched vascular tree consisting of blood vessels of different diameters and functions is established (6,7). Additionally, capillary extension occurs, cell junctions are tightened and vascular perfusion becomes regulated (8,9).

Progranulin (PGRN) is a multifunctional growth factor predominantly expressed by endothelial cells (10). It serves a critical role in inflammatory processes (11,12) and angiogenesis (13). High levels of PGRN have been observed at the sites of wounds and the placenta, where angiogenesis occurs (10,14,15). In human breast cancer cells, PGRN is associated with the promotion of cell proliferation and invasion (16). Furthermore, it is involved in and mediates angiogenesis by directly stimulating vascular endothelial growth factor expression (17). An elevated expression of the PGRN gene has been detected in uterine glandular epithelial cells (18). It has also been detected in the original mesenchyme on the proliferating layer around the glands (18). The extensive expression of PGRN is detected in villous trophoblast cells, especially syncytiotrophoblast cells (19). PGRN can stimulate the cell proliferation of BeWo cells, indicating a growth-stimulating effect during the development of the placenta (19). Furthermore, PGRN is a key factor in blastocyst hatching, adhesion and outgrowth (20). The process of mouse blastocyst formation is delayed when PGRN expression is inhibited (21). Previous studies have suggested that dysregulated PGRN expression in human placentas is associated with pregnancy-related diseases, such as pre-eclampsia (PE) and fetal growth restriction (FGR) (22,23). Insufficient trophoblast invasion, abnormal uterine spiral artery remodeling and placental angiogenesis disorders are identified in the pathophysiology of PE (24,25). Proteomics studies have revealed an increasing trend of PGRN expression levels in maternal plasma from the first to the third trimester during pregnancy, but after delivery, it decreases to pre-pregnancy levels (26). This fluctuation may be associated with placental secretion (27). However, although PGRN has been linked to blastocyst formation in reproductive development and PE pathology in several studies (17,20–23), its specific role in the development of placental blood vessels, particularly in the placental labyrinth, remains to be elucidated.

In the present study, PGRN gene knockout mice (PGRN−/−) were used to examine the role of PGRN in placental blood vessel development. The observed indices included placental size, structure, vascularization biomarkers, such as the vascular smooth muscle cell marker α smooth muscle actin (SMA) (28), the vascular endothelial cell marker platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule, also known as CD31 (29), and endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) (30), as well as pup bodyweights.

Materials and methods

Mouse models

The animal experiments were approved by the Biomedical Ethics Committee of Chongqing Medical University and the Animal Care Committee of Chongqing Medical University (approval no. 2016-41; Chongqing, China). A total of 64 mice were used (ratio of male to female, ~0.23; weight, 19–24 g). The PGRN−/− mice (C57BL/6 background) were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory for Genomic Medicine by Dr Ju Cao at Chongqing Medical University (12,31). Sex- and age-matched C57BL/6 mice (C57) were purchased from the Laboratory Animal Center of Chongqing Medical University (Chongqing, China) and used as controls. Mice were kept in specific pathogen-free facilities in a 12-h light/dark cycle with free access to sterilized food and water. The indoor temperature was 20–26°C (daily temperature difference ≤4°C) and the relative humidity was 40–70%. The present study was conducted when the mice were 8–12 weeks old. After 4 days of acclimation, female mice in estrous were mated with males of the same strain (1–2 females:1 male; PGRN−/− mated with PGRN−/−; C57 mated with C57). The females were inspected the following morning. The day a copulatory plug was found was designated as E0.5. The female mice were sacrificed humanely under anesthesia on E6.5, E14.5 and E17.5. The placentas and embryos were removed, weighed and stored at −80°C or embedded in wax, according to the protocols described subsequently. It was ensured that animals were treated with kindness and with as little pain as possible. After the materials were collected, the mice were sacrificed by anesthesia with 1% pentobarbital sodium (30–45 mg/kg) and asphyxiation with 20–30% cage volume/min CO2 until the concentration of CO2 reached 99%. Euthanasia was confirmed by the observations that the mouse had no heartbeat, had stopped breathing and the pupil of the animal was dilated.

Histology and H&E staining

Placentas were dissected, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde overnight at 4°C and then washed with PBS. For the paraffin block preparation, washed tissues were serially dehydrated with 75, 85, 95, 100 and 100% ethanol, soaked in xylene and then embedded in preheated soft wax at 60°C and preheated paraffin at 80°C, respectively. Paraffin sections (5-µm thick) were de-waxed in xylene, rehydrated with 100, 100, 95, 85 and 75% ethanol series, and stained with H&E at room temperature. The sections were first stained with undiluted hematoxylin for 3–8 min, washed with tap water and then differentiated with 1% hydrochloric acid alcohol for 5–10 sec, washed with tap water and then returned the nucleus from red or pink to blue with 0.6% ammonia water and then rinsed with running water. Following nuclear staining, the sections were placed in eosin staining solution for 1–3 min for cytoplasmic staining. The central sections of the placentas were analyzed for all experiments. A total of 3 wild-type (WT) and 3 PGRN−/− placentas were examined at each of the collection points (E6.5, E14.5 and E17.5, respectively). Sections were observed using a Olympus IX81 upright light microscope, and images were catured with Olympus CellSens Standard Software (both Olympus Corporation) and analyzed via ImageJ software v 1.8.0 (National Institutes of Health).

Immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence

Paraffin sections (5-µm thick) were de-waxed with xylene and rehydrated with 100, 100, 95, 85 and 75% ethanol series, then microwaved in 92–98°C for 15 min for antigen retrieval. Following cooling, the sections were washed with PBS and blocked with 10% H2O2 for 10 min at room temperature, followed by 5% goat serum (cat. no. SP-9001/SP-9002; SPlink Detection kits, Biotin-Streptavidin HRP Detection Systems; OriGene Technologies, Inc.) for blocking at 37°C for 30 min. The sections were then incubated with PGRN (cat. no. ab187070; dilution, 1:200), CD31 (cat. no. ab9498; dilution, 1:500), eNOS (cat. no. ab76198; dilution, 1:500; all Abcam) antibodies, in 1% BSA (cat. no. ST023; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) overnight at 4°C. Subsequently, the sections were kept at room temperature for 30 min, washed with PBS and incubated with biotin-conjugated homologous secondary antibodies, namely non-diluted biotinylated goat anti-rabbit or anti-mouse IgG polymer working solution (cat. no. SP-9001/SP-9002; SPlink Detection kits, Biotin-Streptavidin HRP Detection Systems; OriGene Technologies, Inc.) at 37°C for 30 min. Following washing with PBS three times, the sections were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated streptavidin for 30 min at 37°C. Finally, the sections were washed three times with PBS and subjected to diaminobenzidine staining for the immunohistochemical tests of PGRN, CD31 and eNOS at room temperature. Images were captured using an Olympus IX81 upright light microscope, and analyzed via Olympus CellSens Standard Software (both Olympus Corporation).

In the SMA immunofluorescence assay, the steps before incubation with the primary antibody were the same as for immunohistochemistry and the subsequent immunofluorescence tests were performed in the dark. The sections were first washed three times with PBS following overnight primary antibody incubation in 4°C by anti-α smooth muscle actin (SMA; 1:200; cat. no. ab7817; Abcam) and were then incubated with the FITC-labeled goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (1:200; cat. no. IF-0051; Beijing Dingguo Changsheng Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) for 1 h at 37°C. The sections were then washed three times with PBS, followed by a 2-min incubation with DAPI (1 µg/µl in 1% BSA in PBS) at room temperature. Coverslips were mounted with the washed sections and anti-fluorescence quenching sealant was applied. Images were acquired using an Olympus IX81 upright fluorescence microscope and analyzed via Olympus CellSens Standard Software (Olympus Corporation).

Western blot analysis

A total of three mice from each group were used in this experiment. Mice placentas were homogenized and sonicated in 99% RIPA lysis buffer (cat. no. P0013B; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) and 1% phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride (cat. no. PMSF ST506; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) on ice and then centrifuged at 15,777 × g for 15 min at 4°C. Samples remained on ice and the protein concentrations were determined using a BCA protein assay kit (cat. no. P0010S; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). Next, 2 µg/µl tissue sample, loading buffer (cat. no. 1610747; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.) and lysis buffer (99% RIPA lysis buffer + 1% PMSF) were mixed in proportion and boiled for 10 min, followed by the addition of 10 µl dithiothreitol. Proteins were loaded (20 µg per lane) separated using 10 and 7% SDS-PAGE and transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane. The membrane was blocked with 5% skimmed milk/PBS for 1 h at room temperature, followed by incubation with the corresponding primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. Following three washes with PBS, the membranes were incubated with a specific horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-rabbit/mouse IgG secondary antibody (1:5,000; cat. no. SH-0031/0011; Beijing Dingguo Changsheng Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) for 1 h at room temperature, washed with PBS three times and then incubated with Immobilon Western Horseradish Peroxidase (Merck KGaA). Western blots/arrays were visualized at room temperature using enhanced chemiluminescence western blotting reagents (cat. no. RPN2109; Cytiva) and a Bio-Rad ChemiDoc MP Imaging system. Images were analyzed via Image Lab v4.0 (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.). The primary antibodies used were: PGRN (cat. no. ab187070; dilution, 1:200), CD31 (1:500; cat. no. ab9498), SMA (cat. no. ab7817; dilution, 1:200) and eNOS (cat. no. ab76198; dilution, 1:1,000; all from Abcam). Mouse monoclonal β-actin (Beijing Dingguo Changsheng Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) was used as an internal control.

Histomorphometric measurements

For histomorphometric measurements, three sections per placenta taken at 100-µm intervals from the central region near the site of umbilical cord attachment were analyzed. The areas and diameters were measured using ImageJ software v1.8.0 (National Institutes of Health).

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as the mean of ≥6 independent repeats. All data are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was calculated using an unpaired Student's t-test or Welch's t-test. Weight data were analyzed using a Mann-Whitney U test. GraphPad Prism v5.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc.) was used for all statistical analysis including the Kaplan-Meier plot of survival analysis using the log-rank (Mantel-Cox) and Gehan-Breslow-Wilcoxon tests. *P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Lower PGRN expression in PGRN−/− placentas

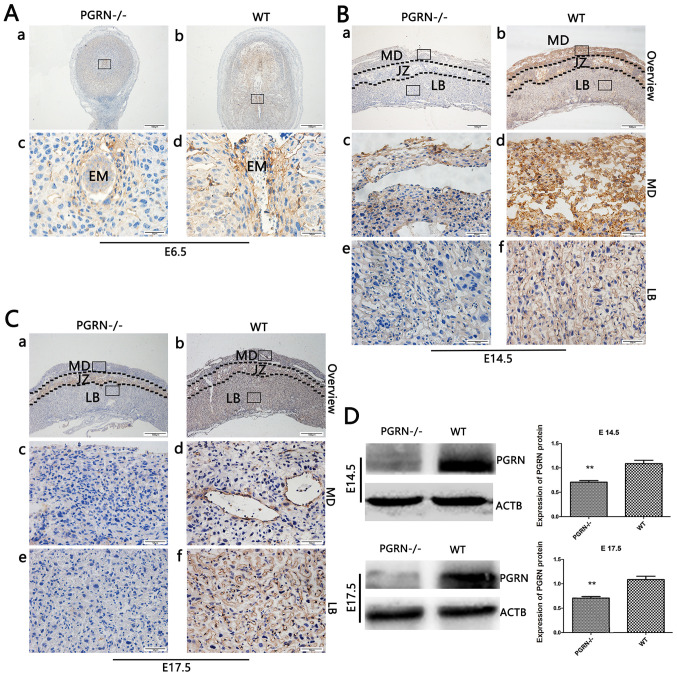

Immunoh istochemical analysis of mouse embryos at E6.5 (after implantation was completed) revealed that PGRN was present around the embryos (Fig. 1Ab and d) in WT mice. However, its expression was almost undetectable in PGRN−/− mice (Fig. 1Aa and c). Immunohistochemistry revealed high levels of PGRN on E14.5 in the WT mice compared with in the PGRN−/− mice, particularly in the maternal decidua and junctional zone, and partly in the labyrinthine layer, where the process of decidual transformation and fetal neovascularization is accompanied by extensive angiogenesis (32–35) (Fig. 1B). On E17.5, PGRN was most easily observed in the WT maternal decidua, followed by the labyrinthine layer (Fig. 1Cb, d and f), while it was less expressed in the PGRN−/− maternal decidua and labyrinthine layer (Fig. 1Ca, c and e). Additionally, western blot analysis demonstrated that PGRN expression was significantly lower in PGRN−/− placentas on E14.5 and E17.5 (Fig. 1D) when compared with the WT placentas.

Figure 1.

PGRN in developing embryos on E6.5 and placentas on E14.5 and E17.5. Immunohistochemistry was performed on sections of embryos on (A) E6.5, and placental tissues on (B) E14.5 and (C) E17.5. (A) Boxed areas in (a) and (b) are magnified in (c) and (d), respectively. (B and C) Boxed areas in (a) are magnified in (c) and (e). Boxed areas in (b) are magnified in (d) and (f). (D) Western blot analysis of placental tissue on E14.5 and E17.5. Scale bar, 500 µm; magnified scale bar, 50 µm. **P<0.01. PGRN, progranulin; E, embryonic day; -/-, PGRN−/− mice; +/+, WT mice; WT, wild-type; EM, embryo; MD, maternal decidua; JZ, junctional zone; LB, labyrinthine layer; ACTB, β-actin.

Smaller placentas in PGRN−/− mice

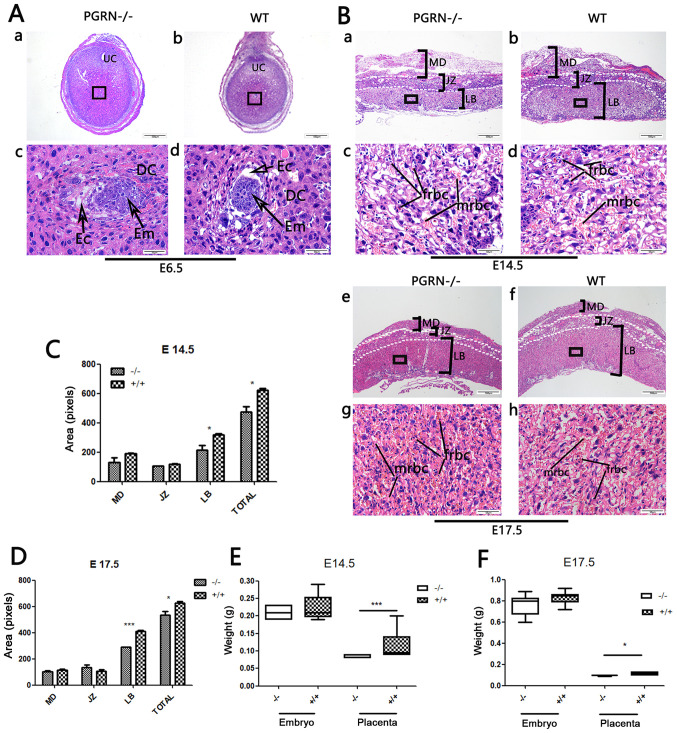

The embryos of PGRN−/− and WT C57 mice were visible, as were the decidual cells around them (Fig. 2A). PGRN−/− placentas exhibited normal structure of the three compartments (maternal decidua, junctional zone and labyrinthine layer). However, the total area of the PGRN−/− placentas was significantly smaller compared with that of the WT placentas, and the area of the labyrinth zone was reduced on E14.5 (Fig. 2Ba and b, and 2C) and E17.5 (Fig. 2Be and f, and 2D). The labyrinth appeared to be more compact, with more clusters of densely packed trophoblast cells in the PGRN−/− placenta on E14.5 and E17.5 (Fig. 2Bc and g), compared with the WT placenta (Fig. 2Bd and h). The fetal blood vessel spaces were decreased in the PGRN−/− mice compared with the WT placenta, and the embryonic erythrocytes, which were less frequently detected, appeared to be squeezed into the narrowed vessels (Fig. 2Bc and g). Furthermore, the weight of the PGRN−/− placentas was significantly lower compared with that of the WT placentas on E14.5 and E17.5 (Fig. 2E and F).

Figure 2.

Changes in PGRN−/− mouse placentas and embryos. (A) H&E staining of (a and c) PGRN−/− sections and (b and d) WT (C57) embryos on E6.5. (c and d) Higher magnifications of the boxed areas in (a) and (b) show the embryos. (B) H&E staining of PGRN−/− sections and WT (C57) placentas on (a-d) E14.5 and (e-h) E17.5. Higher magnifications of the boxed areas in (a), (b), (e) and (f) show the structure of the labyrinth and the red blood cells of PGRN−/− and WT placentas on the maternal and fetal sides on (c and d) E14.5 and (g and h) E17.5. (C) Morphometrical analysis of sections in (Ba and b) E14.5. (D) Morphometrical analysis of sections in (Be and f) E17.5. (E) Weights of placentas and embryos from WT and PGRN−/− mice on E14.5 were analyzed. (F) Weights of placentas and embryos from WT and PGRN−/− mice on E17.5 were analyzed. Scale bar, 500 µm; magnified scale bar, 50 µm. *P<0.05, ***P<0.001. PGRN, progranulin; H&E, hematoxylin and eosin; -/-, PGRN−/− mice; +/+, WT mice; WT, wild-type; E, embryonic day; Em, embryo; MD, maternal decidua; JZ, junctional zone; LB, labyrinthine layer; frbc, fetal red blood cells; mrbc, maternal red blood cells.

Abnormal placental vascularization in PGRN−/− mice

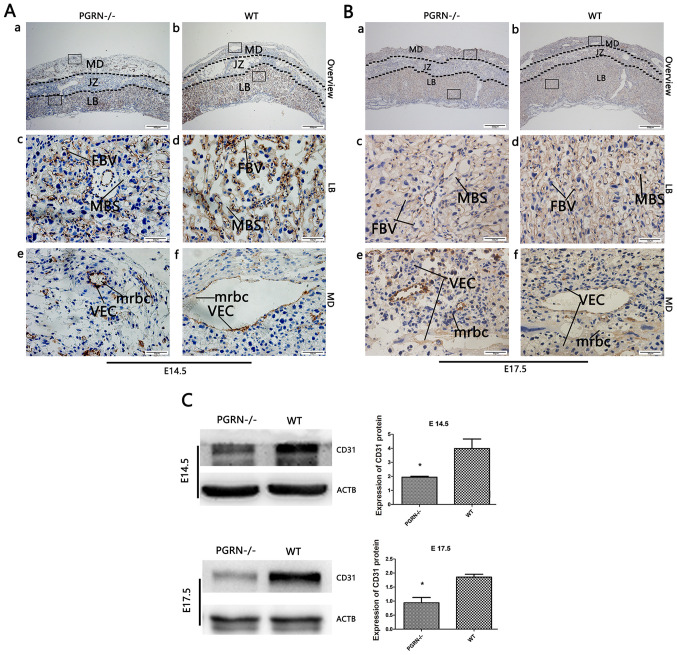

To further investigate the altered placental vascularization, western blot analysis and immunohistochemistry of CD31 expression were conducted. CD31 staining was observed in the vascular endothelial cells of WT mice, most of which resided in the labyrinth zone, while the rest was expressed in the maternal decidua on E14.5 (Fig. 3Ab) and E17.5 (Fig. 3Bb). A markedly lower amount of CD31 was observed in the labyrinthine layer of the PGRN−/− placentas on E14.5 (Fig. 3Aa and c). In addition, the blood vessels in the WT placental labyrinth aligned in a polar manner from the maternal to the fetal side, while there were fewer vessels in the PGRN−/− placental labyrinth, which were arrayed in a disorderly manner (Fig. 3Ac and d, and 3Bc and d). On E14.5, the labyrinthine layer of the PGRN−/− placentas exhibited a higher density and a considerably more disordered trophoblast cell distribution (Fig. 3Ac). Additionally, a higher-magnification examination of the maternal decidua revealed that the vascular endothelium was more compacted and blood vessel expansion appeared to be restricted, which led to a smaller vessel lumen in the PGRN−/− placenta (Fig. 3Ae) compared with the WT placenta (Fig. 3Af). Smaller terminal sinusoids were observed in the PGRN−/− placental labyrinth, compared with the WT placental labyrinth, accompanied by inordinate trophoblast cells on E14.5 (Fig. 3Ac and d). During the development of the normal placenta, as the chorioallantoic interface underwent more extensive branching, the trophoblast-lined sinusoid spaces became progressively smaller (Fig. 3Bd). However, the sinusoid spaces of the labyrinth in the PGRN−/− placentas on E17.5 were much larger compared with those in the WT placentas (Fig. 3Bc). CD31 was expressed at higher levels on E17.5 than on E14.5, in the PGRN−/− (Fig. 3Ba and c) and WT groups (Fig. 3Bb and d), especially in the labyrinthine layer. The difference in the staining density of CD31 between the two groups was more apparent on E17.5 than on E14.5. Western blot analysis revealed that CD31 expression in WT placentas was significantly higher compared with that in the PGRN−/− placentas on E14.5 and E17.5 (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3.

CD31 expression in developing placentas from PGRN−/− and WT mice on E14.5 and E17.5. Immunohistochemical detection of CD31 in the serial placental sections on (A) E14.5 and (B) E17.5. (A and B) Boxed areas in (a) are magnified in panels (c) and (e). Boxed areas in (b) are magnified in panels (d) and (f). (C) Western blot analysis and quantification of the results in placentas on E14.5 and E17.5. Scale bar, 500 µm; magnified scale bar, 50 µm. *P<0.05. CD31, cluster of differentiation 31; PGRN, progranulin; -/-, PGRN−/− mice; WT, wild-type; E, embryonic day; MD, maternal decidua; JZ, junctional zone; LB, labyrinthine layer; MBS, maternal blood sinus; FBV, fetal blood vessel; VEC, vascular endothelial cells; mrbc, maternal red blood cells; ACTB, β-actin.

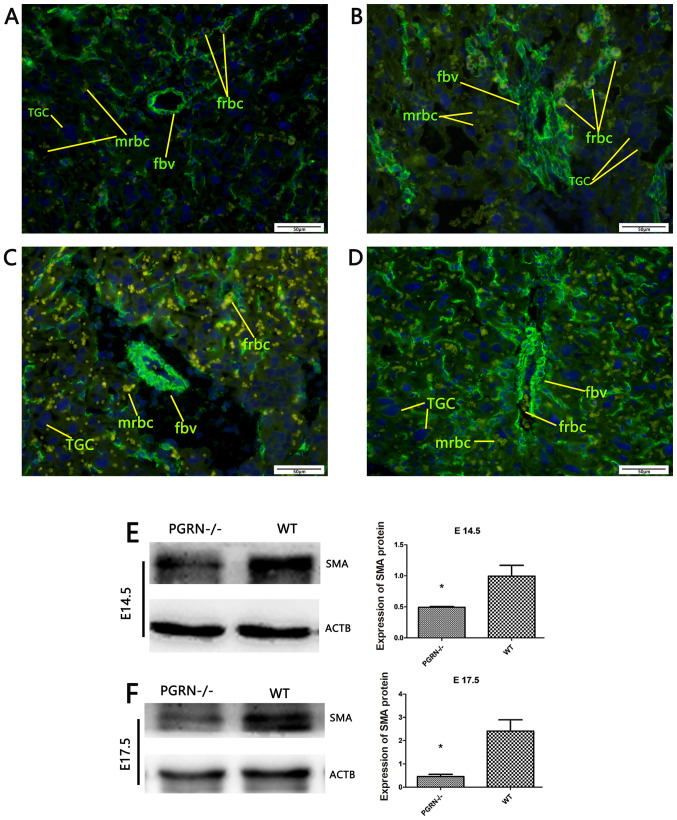

To gain a more detailed understanding, placental SMA was stained using immunofluorescence to examine the smooth muscles of the blood vessels. The SMA staining results demonstrated that the number of fetal red blood cells was lower in the PGRN−/− placenta labyrinthine layer (Fig. 4A and C) compared with the WT placentas (Fig. 4B and D). A higher-magnification examination on E14.5 revealed a smaller vascular diameter, as well as less vascular distribution and fetal red blood cells in the PGRN−/− placentas (Fig. 4A). In WT placentas, the fetal blood vessels were elongated and radiated uniformly from the chorionic plate to the labyrinthine layer (Fig. 4B). On E17.5, extensive branching of the fetal capillaries was observed in the WT placentas. In accordance with the observations on E14.5, the vascular smooth muscles of the WT placentas appeared elongated in long, straight segments and ran parallel to each other toward the decidua (Fig. 4D). By contrast, the vascular smooth muscles in the PGRN−/− placentas were randomly aligned, abnormally branched and irregular in diameter (Fig. 4C). Furthermore, it was observed that the fetal blood vessels were dilated, the smooth muscle cells were separated from the trophoblast and branching of the fetal capillaries was defective in the PGRN−/− placentas (Fig. 4C). Western blot analysis demonstrated that the WT placentas exhibited significantly higher protein expression levels of SMA compared with the PGRN−/− placentas on both E14.5 and E17.5 (Fig. 4E and F).

Figure 4.

SMA expression in developing placentas of PGRN−/− and WT mice on E14.5 and E17.5. Immunofluorescence evaluation of SMA in (A) the placentas of PGRN−/− mice on E14.5, (B) the placentas of WT mice on E14.5, (C) the placentas of PGRN−/− mice on E17.5 and (D) the placentas of WT mice on E17.5. Western blot analysis was performed on placental tissue on (E) E14.5 and (F) E17.5. Scale bar, 50 µm. *P<0.05. SMA, smooth muscle actin; -/-, PGRN−/− mice; PGRN, progranulin; WT, wild-type; E, embryonic day; TGC, trophoblast giant cells; fbv, fetal blood vessels; mrbc, maternal red blood cells; frbc, fetal red blood cells; ACTB, β-actin.

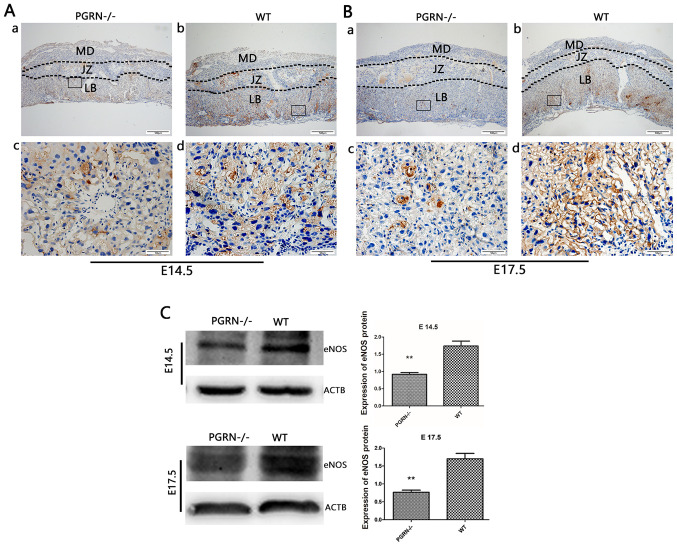

Decreased expression of vasodilation factors in PGRN−/− placentas

eNOS was detected in the labyrinthine layer of PGRN−/− and WT mice on both E14.5 and E17.5 (Fig. 5Aa and b, and Ba and b). However, it was only observed in the junctional zone on E14.5, but not on E17.5 (Fig. 5Aa and b, and Ba and b). The expression levels of eNOS in the labyrinthine layer were much higher in WT mice compared with in PGRN−/− mice on E14.5 and E17.5 (Fig. 5Ac and d, and Bc and d). Western blot analysis demonstrated that eNOS expression in the WT group was higher than that in the PGRN−/− group on E14.5 and E17.5 (Fig. 5C).

Figure 5.

eNOS expression in the developing placenta is lower in PGRN−/− than in WT placentas on both E14.5 and E17.5, particularly in the labyrinthine layer of the placenta. Immunohistochemistry was performed on serial placental sections from (A) E14.5 and (B) E17.5 to determine eNOS expression. (A and B) Boxed areas in (a) are magnified in (c). Boxed areas in (b) are magnified in (d). (C) Western blotting and relative gray analysis was performed on placentas on E14.5 and E17.5. Scale bar, 500 µm; magnified scale bar, 50 µm. **P<0.01. eNOS, endothelial nitric oxide synthase; -/-, PGRN−/− mice; PGRN, progranulin; WT, wild-type; E, embryonic day; MD, maternal decidua; JZ, junctional zone; LB, labyrinthine layer; ACTB, β-actin.

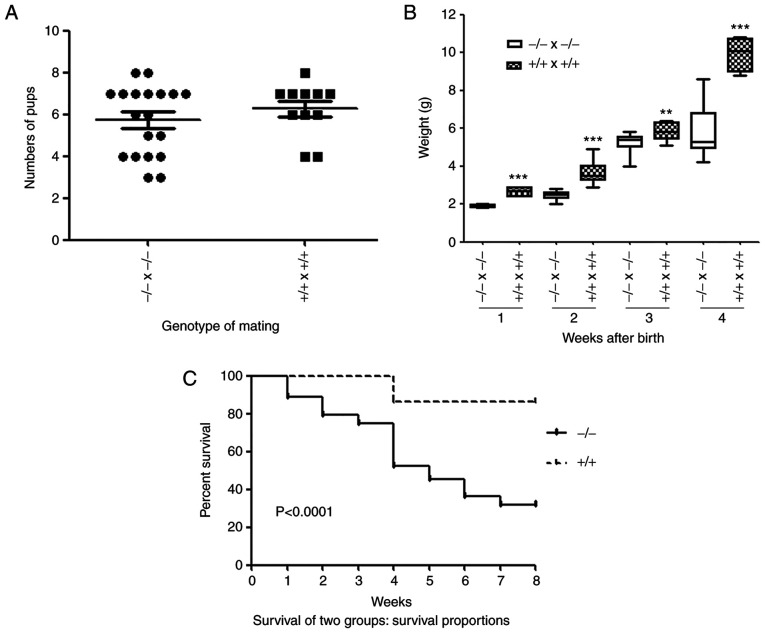

Growth retardation in newborn PGRN−/− pups

PGRN−/− mice were viable and fertile (Fig. 6A). The number of pups produced was not affected by the parental genotype (Fig. 6A). No significant difference was observed between the weights of the embryos of the two groups on E14.5 and E17.5 (Fig. 2E and F). However, the body weights of the newborn pups of the PGRN−/- mice were significantly lower compared with the WT pups (Fig. 6B). Furthermore, survival analysis demonstrated that the mortality of PGRN−/− pups was significantly higher than that of WT controls (Fig. 6C).

Figure 6.

Number, weight and survival rate of newborn pups born from WT and PGRN−/− parents. (A) Number of pups born from WT or PGRN−/− parents. (B) Body weight of WT and PGRN−/− pups following birth. The boxes indicate the 25th and 75th percentile, the bands within these boxes indicate the median values, and the ends of the bars indicate the maximum and minimum values. (C) Survival proportion between the two groups (−/- and +/+) of PGRN−/− and WT mice 2 months after birth. **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 vs. -/-x-/- weight in the same week. +/+, WT mice; WT, wild-type; -/-, PGRN−/− mice; PGRN, progranulin.

Discussion

Previous studies have demonstrated that PGRN serves a role in vascular development (36,37). Furthermore, studies have suggested that PGRN expression in the human placenta is closely associated with certain pregnancy-related diseases, such as PE and fetal FGR (22,23). The pathogenesis of PE and FGR is complex and cannot be explained by a single change, including the lack of trophoblast invasion and abnormal placental angiogenesis, as well as for several other reasons such as persistent placental hypoxia and the release of numerous mediators into the maternal circulation (24,25). The significant increase in serum PGRN levels in women with PE (22) suggests that the incidence of PE is uncertain, due to insufficient PGRN, which may be due to other reasons that lead to insufficient placental angiogenesis in PE and FGR. In order to promote angiogenesis, PGRN in the body is elevated but the angiogenesis outcome of PE and FGR cannot be completely rectified. The specific association and underlying mechanism require further research. In the present study, a PGRN knockout mouse model was used to determine whether PGRN served a role in the development of placental vasculature, particularly in the labyrinth.

Abnormal PGRN expression in endothelial cells influences angiogenesis in vivo (38). Studies have reported high levels of PGRN expression in the placenta of minks and mice (14,39). In adults, rapidly renewed epithelial cells, such as corneal or intestinal epithelial cells in deep crypts, express PGRN genes at high levels, while most epithelial cells in the resting state of mitosis, such as the epithelial cells of the lungs or renal tubules, have relatively low expression levels (18). Additionally, the findings of the present study demonstrated PGRN expression in the placentas of WT mice, which reflected the expression and distribution of PGRN in mouse placentas under normal conditions. It has been reported that PGRN can increase the capillary size and number when added to rodent dermal wounds (10). Another study reported that PGRN influences vasculogenesis by regulating vascular permeability in the brain (40). The data of the present study revealed that the knockout of the PGRN gene in a mouse model resulted in placental blood vessels of a smaller diameter and reduced distribution. A previous study demonstrated that PGRN affects angiogenic behavior in vitro and in vivo (41). Other studies examined the effect of PGRN in isolated superior rat mesenteric artery rings and revealed that it is involved in the regulation of vascular tone by regulating eNOS and smooth muscle (36,42). Another study suggested that eNOS contributes to changes in uterine placental blood vessels and increases in uterine artery blood flow during pregnancy (30). Furthermore, PGRN reportedly upregulates the Akt/eNOS phosphorylation level in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (37,43). The present study demonstrated that the expression of eNOS and SMA in PGRN−/− placentas was lower compared with that in WT placentas. In the experimental results of the present study, it could be observed under a high magnification that PGRN−/− genotype maternal decidual vascular endothelial cells were denser, blood vessel walls were thicker and the placental vascular lumen diameter was reduced compared with WT placental cells. These phenomena suggested that, when PGRN is knocked out, the defective expression of eNOS in the mouse placenta may cause vascular remodeling disorders. Therefore, the present findings, combined with those of previous studies, demonstrated that PGRN regulates placental angiogenesis.

The maternal-fetal interface is mainly made up of the maternal decidua, the junctional zone and the labyrinthine layer, which undergo extensive angiogenesis during pregnancy (35). The labyrinthine layer is a widely vascularized tissue and abnormal vascular formation can lead to aberrant placental development (32,35). Previous studies have demonstrated that follicle stimulating hormone receptor, TEK receptor tyrosine kinase, vascular cell adhesion molecule-1, ESX homeobox 1 (Esx1), connexin 45, platelet-derived growth factor B/β-receptor and aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator (ARNT) are important genes during vascular development, whose knockout results in a defective labyrinth (44–49). Additional studies have reported genes, such as the translocon-associated protein subunit γ, Esx1, ARNT and retinoid X receptors, to be associated with normal labyrinth development, and knocking out any one of them can lead to a narrowed labyrinth, abnormal placental development, fetal growth retardation or even fetal death (39,46,49,50). Additionally, a narrowed labyrinth and distributed dysplastic fetal capillaries in PGRN−/− mice were observed in the present study. These findings suggested that insufficient PGRN leads to abnormal blood vessel development and can result in a defective labyrinth and insufficient placental development. When comparing the placenta weights of PGRN−/− and WT mice on E14.5 and E17.5, the placenta weight of PGRN−/− mice was significantly lower compared with that of WT normal mouse placentas. This result demonstrated that the absence of PGRN expression in mice can delay placental development. The difference in chorionic artery branching between the normal and FGR placentas is caused by the different placenta sizes (51). FGR placentas show microvascular degeneration and extreme vascular deficiencies in the surrounding area, and these features are likely to limit the placental ability to meet fetal nutritional needs in late pregnancy (51). The data from the present study revealed that the weight of the PGRN−/− placentas and newborn pups, and the survival rate of PGRN−/− pups, were significantly lower compared with those of mice in the WT group. Therefore, insufficient PGRN may affect pup weight and survival rate as a result of the disordered labyrinth and abnormal placental function.

In the present study, it was revealed that knocking out PGRN led to a smaller diameter and less distribution of the blood vessels in the placenta and affected the body weight of the pups following their birth. This result suggested that the bodyweight of the pups was not directly affected by the underdeveloped placenta. However, the PGRN−/− pup body weight increased at a significantly slower rate compared with WT pups, which might be due to two possible reasons. First, that the underdeveloped placenta hindered the normal development of the pups (39,46,49,50) and second, that the PGRN−/- gene prevented the pups from normal postnatal growth due to problems associated with angiogenesis in key organs (40,52,53). Therefore, to what extent the underdeveloped placenta and the PGRN−/− gene that the pups carry affect the growth of the pups requires further investigation.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated that the absence of PGRN may lead to aberrant angiogenesis in the placental labyrinth, further disrupting the structure of the nutrient-waste exchange system, which may give rise to adverse pregnancy outcomes. Further analysis of PGRN knockout mice should be conducted to provide insights into the molecular mechanisms regulating the vasculature of the placenta. The results of the present study expanded the list of known growth factors regulating placental angiogenesis, by demonstrating that placental PGRN is essential for appropriate angiogenesis of the placenta, particularly in the labyrinth.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr Ju Cao at Chongqing Medical University, China, for kindly donating PGRN−/− mice (C57BL/6 background).

Funding

The present study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 81971406, 81771607, 81871185, 81961128004 and 81701477), The 111 Project [grant no. Yuwaizhuan (2016)32], The National Key Research and Development Program of Reproductive Health & Major Birth Defects Control and Prevention (grant no. 2016YFC1000407), Chongqing Health Commission (grant nos. 2017ZDXM008 and 2018ZDXM024) and Chongqing Science & Technology Commission (grant nos. cstc2017jcyjBX0060 and cstc2018jcyjAX0359).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

BX and XC designed and performed the experiments, conducted the statistical analysis of the data and drafted the manuscript. TL, HZ, YD and CC participated in the conception and experimental design of the project, provided the materials needed for the experiment and helped write the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The present study was reviewed and approved by the Experimental Animal Ethics Committee of Chongqing Medical University (approval no. 2016-41).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Sibley CP, Brownbill P, Glazier JD, Greenwood SL. Knowledge needed about the exchange physiology of the placenta. Placenta. 2018;64(Suppl 1):3482–S15. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2018.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Muntener M, Hsu YC. Development of trophoblast and placenta of the mouse. A reinvestigation with regard to the in vitro culture of mouse trophoblast and placenta. Acta Anat (Basel) 1977;98:241–252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adamson SL, Lu Y, Whiteley KJ, Holmyard D, Hemberger M, Pfarrer C, Cross JC. Interactions between trophoblast cells and the maternal and fetal circulation in the mouse placenta. Dev Biol. 2002;250:358–373. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Malassine A, Frendo JL, Evain-Brion D. A comparison of placental development and endocrine functions between the human and mouse model. Hum Reprod Update. 2003;9:531–539. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmg043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carmeliet P, Jain RK. Angiogenesis in cancer and other diseases. Nature. 2000;407:249–257. doi: 10.1038/35025220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carmeliet P, Collen D. Role of vascular endothelial growth factor and vascular endothelial growth factor receptors in vascular development. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1999;237:133–158. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-59953-8_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Risau W. Mechanisms of angiogenesis. Nature. 1997;386:671–674. doi: 10.1038/386671a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carmeliet P, Conway EM. Growing better blood vessels. Nat Biotechnol. 2001;19:1019–1020. doi: 10.1038/nbt1101-1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leach L, Lammiman MJ, Babawale MO, Hobson SA, Bromilou B, Lovat S, Simmonds MJ. Molecular organization of tight and adherens junctions in the human placental vascular tree. Placenta. 2000;21:547–557. doi: 10.1053/plac.2000.0541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.He Z, Ong CH, Halper J, Bateman A. Progranulin is a mediator of the wound response. Nat Med. 2003;9:225–229. doi: 10.1038/nm816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jian J, Konopka J, Liu C. Insights into the role of progranulin in immunity, infection, and inflammation. J Leukoc Biol. 2013;93:199–208. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0812429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yin F, Banerjee R, Thomas B, Zhou P, Qian L, Jia T, Ma X, Ma Y, Iadecola C, Beal MF, et al. Exaggerated inflammation, impaired host defense, and neuropathology in progranulin-deficient mice. J Exp Med. 2010;207:117–128. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eguchi R, Nakano T, Wakabayashi I. Progranulin and granulin-like protein as novel VEGF-independent angiogenic factors derived from human mesothelioma cells. Oncogene. 2017;36:714–722. doi: 10.1038/onc.2016.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Desmarais JA, Cao M, Bateman A, Murphy BD. Spatiotemporal expression pattern of progranulin in embryo implantation and placenta formation suggests a role in cell proliferation, remodeling, and angiogenesis. Reproduction. 2008;136:247–257. doi: 10.1530/REP-08-0044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Winther H, Leiser R, Pfarrer C, Dantzer V. Localization of micro- and intermediate filaments in non-pregnant uterus and placenta of the mink suggests involvement of maternal endothelial cells and periendothelial cells in blood flow regulation. Anat Embryol (Berl) 1999;200:253–263. doi: 10.1007/s004290050277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tangkeangsirisin W, Serrero G. PC cell-derived growth factor (PCDGF/GP88, progranulin) stimulates migration, invasiveness and VEGF expression in breast cancer cells. Carcinogenesis. 2004;25:1587–1592. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgh171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tangkeangsirisin W, Hayashi J, Serrero G. PC cell-derived growth factor mediates tamoxifen resistance and promotes tumor growth of human breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2004;64:1737–1743. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-2364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Daniel R, He Z, Carmichael KP, Halper J, Bateman A. Cellular localization of gene expression for progranulin. J Histochem Cytochem. 2000;48:999–1009. doi: 10.1177/002215540004800713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stubert J, Richter DU, Gerber B, Briese V. Expression pattern of progranulin in the human placenta and its effect on cell proliferation in the choriocarcinoma cell line BeWo. J Reprod Dev. 2011;57:229–235. doi: 10.1262/jrd.10-073K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Qin J, Diaz-Cueto L, Schwarze JE, Takahashi Y, Imai M, Isuzugawa K, Yamamoto S, Chang KT, Gerton GL, Imakawa K. Effects of progranulin on blastocyst hatching and subsequent adhesion and outgrowth in the mouse. Biol Reprod. 2005;73:434–442. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.105.040030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Díaz-Cueto L, Stein P, Jacobs A, Schultz RM, Gerton GL. Modulation of mouse preimplantation embryo development by acrogranin (epithelin/granulin precursor) Dev Biol. 2000;217:406–418. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Açıkgöz AS, Tüten A, Öncül M, Eskalen S, Dinçgez BC, Şimşek A, Yüksel MA, Guralp O. Evaluation of maternal serum progranulin levels in normotensive pregnancies, and pregnancies with early- and late-onset preeclampsia. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2016;29:2658–2664. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2015.1096338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stubert J, Schattenberg F, Richter DU, Dieterich M, Briese V. Trophoblastic progranulin expression is upregulated in cases of fetal growth restriction and preeclampsia. J Perinat Med. 2012;40:475–481. doi: 10.1515/jpm-2011-0277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kadyrov M, Kingdom JC, Huppertz B. Divergent trophoblast invasion and apoptosis in placental bed spiral arteries from pregnancies complicated by maternal anemia and early-onset preeclampsia/intrauterine growth restriction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194:557–563. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tal R. The role of hypoxia and hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha in preeclampsia pathogenesis. Biol Reprod. 2012;87:134. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.112.102723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aghaeepour N, Lehallier B, Baca Q, Ganio EA, Wong RJ, Ghaemi MS, Culos A, El-Sayed YY, Blumenfeld YJ, Druzin ML, et al. A proteomic clock of human pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;218:347.e1–347.e14. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2017.12.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stubert J, Szewczyk M, Spitschak A, Knoll S, Richter DU, Pützer BM. Adenoviral mediated expression of anti-inflammatory progranulin by placental explants modulates endothelial cell activation by decrease of ICAM-1 expression. Placenta. 2020;90:109–117. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2019.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Honma M, Koizumi F, Wakaki K, Ochiai H. Co-expression of fibroblastic, histiocytic and smooth muscle cell phenotypes on cultured adherent cells derived from human palatine tonsils: A morphological and immunocytochemical study. Pathol Int. 1995;45:903–913. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.1995.tb03415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jackson DE, Gully LM, Henshall TL, Mardell CE, Macardle PJ. Platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 (PECAM-1/CD31) is associated with a naive B-cell phenotype in human tonsils. Tissue Antigens. 2000;56:105–116. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0039.2000.560201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kulandavelu S, Whiteley KJ, Qu D, Mu J, Bainbridge SA, Adamson SL. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase deficiency reduces uterine blood flow, spiral artery elongation, and placental oxygenation in pregnant mice. Hypertension. 2012;60:231–238. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.187559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhixin S, Xuemei Z, Liping Z, Xu F, Tao X, Zhang H, Lin X, Kang L, Xiang Y, Lai X, et al. Progranulin plays a central role in host defense during sepsis by promoting macrophage recruitment. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;194:1219–1232. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201601-0056OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Portilho NA, Pelajo-Machado M. Mechanism of hematopoiesis and vasculogenesis in mouse placenta. Placenta. 2018;69:140–145. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2018.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Daniel R, Daniels E, He Z, Bateman A. Progranulin (acrogranin/PC cell-derived growth factor/granulin-epithelin precursor) is expressed in the placenta, epidermis, microvasculature, and brain during murine development. Dev Dyn. 2003;227:593–599. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Enders AC. A comparative study of the fine structure of the trophoblast in several hemochorial placentas. Am J Anat. 1965;116:29–67. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001160103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Walentin K, Hinze C, Schmidt-Ott KM. The basal chorionic trophoblast cell layer: An emerging coordinator of placenta development. Bioessays. 2016;38:254–265. doi: 10.1002/bies.201500087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Beltowski J. Role of progranulin in the regulation of vascular tone: (patho)physiological implications. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2017;219:706–708. doi: 10.1111/apha.12799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hwang HJ, Jung TW, Hong HC, Choi HY, Seo JA, Kim SG, Kim NH, Choi KM, Choi DS, Baik SH, Yoo HJ. Progranulin protects vascular endothelium against atherosclerotic inflammatory reaction via Akt/eNOS and nuclear factor-κB pathways. PLoS One. 2013;8:e76679. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Toh H, Cao M, Daniels E, Bateman A. Expression of the growth factor progranulin in endothelial cells influences growth and development of blood vessels: A novel mouse model. PLoS One. 2013;8:e64989. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yamaguchi YL, Tanaka SS, Oshima N, Kiyonari H, Asashima M, Nishinakamura R. Translocon-associated protein subunit Trap-γ/Ssr3 is required for vascular network formation in the mouse placenta. Dev Dyn. 2011;240:394–403. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kanazawa M, Kawamura K, Takahashi T, Miura M, Tanaka Y, Koyama M, Toriyabe M, Igarashi H, Nakada T, Nishihara M, et al. Multiple therapeutic effects of progranulin on experimental acute ischaemic stroke. Brain. 2015;138:1932–1948. doi: 10.1093/brain/awv079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Toh H, Daniels E, Bateman A. Methods to investigate the roles of progranulin in angiogenesis using in vitro strategies and transgenic mouse models. Methods Mol Biol. 2018;1806:329–360. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-8559-3_22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kazama K, Hoshino K, Kodama T, Okada M, Yamawaki H. Adipocytokine, progranulin, augments acetylcholine-induced nitric oxide-mediated relaxation through the increases of cGMP production in rat isolated mesenteric artery. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2017;219:781–789. doi: 10.1111/apha.12739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jiang F, Wang H, Bao S, Zhou H, Zhang Y, Yan Y, Lai Y, Teng W, Shan Z. Thyrotropin regulates eNOS expression in the endothelium by PGRN through Akt pathway. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2018;9:353. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2018.00353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stilley JAW, Segaloff DL. Deletion of fetoplacental Fshr inhibits fetal vessel angiogenesis in the mouse placenta. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2018;476:79–83. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2018.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kwee L, Baldwin HS, Shen HM, Stewart CL, Buck C, Buck CA, Labow MA. Defective development of the embryonic and extraembryonic circulatory systems in vascular cell adhesion molecule (VCAM-1) deficient mice. Development. 1995;121:489–503. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.2.489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li Y, Behringer RR. Esx1 is an X-chromosome-imprinted regulator of placental development and fetal growth. Nat Genet. 1998;20:309–311. doi: 10.1038/3129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Krüger O, Plum A, Kim JS, Winterhager E, Maxeiner S, Hallas G, Kirchhoff S, Traub O, Lamers WH, Willecke K. Defective vascular development in connexin 45-deficient mice. Development. 2000;127:4179–4193. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.19.4179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ohlsson R, Falck P, Hellström M, Lindahl P, Boström H, Franklin G, Ahrlund-Richter L, Pollard J, Soriano P, Betsholtz C. PDGFB regulates the development of the labyrinthine layer of the mouse fetal placenta. Dev Biol. 1999;212:124–136. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kozak KR, Abbott B, Hankinson O. ARNT-deficient mice and placental differentiation. Dev Biol. 1997;191:297–305. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1997.8758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wendling O, Chambon P, Mark M. Retinoid X receptors are essential for early mouse development and placentogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:547–551. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.2.547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Junaid TO, Brownbill P, Chalmers N, Johnstone ED, Aplin JD. Fetoplacental vascular alterations associated with fetal growth restriction. Placenta. 2014;35:808–815. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2014.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jackman K, Kahles T, Lane D, Garcia-Bonilla L, Abe T, Capone C, Hochrainer K, Voss H, Zhou P, Ding A, et al. Progranulin deficiency promotes post-ischemic blood-brain barrier disruption. J Neurosci. 2013;33:19579–19589. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4318-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fu Y, Sun Y, Zhou M, Wang X, Wang Z, Wei X, Zhang Y, Su Z, Liang K, Tang W, Yi F. Therapeutic potential of progranulin in hyperhomocysteinemia-induced cardiorenal dysfunction. Hypertension. 2017;69:259–266. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.116.08154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.