Abstract

Despite increased research on bullying over the past few decades, researchers still have little understanding of how bullying differentially affects racial and ethnic minority and immigrant youth. To facilitate efforts to better evaluate the impact of bullying among racial and ethnic minority youth and improve interventions, we integrated research from multiple disciplines and conducted a systematic search to review relevant cross-cultural research on the prevalence of bullying, risk and protective factors, and differences in behaviors and outcomes associated with bullying in these populations. Studies measuring differences in bullying prevalence by racial and ethnic groups are inconclusive, and discrepancies in findings may be explained by differences in how bullying is measured and the impact of school and social environments. Racial and ethnic minorities and immigrants are disproportionately affected by contextual-level risk factors associated with bullying (e.g., adverse community, home, and school environments), which may moderate the effects of individual-level predictors of bullying victimization or perpetration (e.g., depressive symptoms, empathy, hostility, etc.) on involvement and outcomes. Minority youth may be more likely to perpetrate bullying, and are at much higher risk for poor health and behavioral outcomes as a result of bias-based bullying. At the same time, racial and ethnic minorities and immigrants may be protected against bullying involvement and its negative consequences as a result of strong ethnic identity, positive cultural and family values, and other resilience factors. Considering these findings, we evaluate existing bullying interventions and prevention programs and propose directions for future research.

Keywords: bullying, race, ethnicity, immigration, bias, multiculturalism, interventions

Bullying involvement in youth is associated with increased risk for negative mental health and behavioral outcomes throughout the lifespan, including anxiety, depression, suicidal ideation and attempts, substance use, criminality, and involvement in other forms of interpersonal violence, such as child abuse and intimate partner violence (Klomek, Marrocco, Kleinman, Schonfeld, & Gould, 2007; Mills, Guerin, Lynch, Daly, & Fitzpatrick, 2004; Forero, McLellan, Rissel, & Bauman, 1999; Olweus, 2011; Renda, Vassallo, & Edwards, 2011; Corvo, 2011; Ttofi, Farrington, Lösel, & Loeber, 2011; Falb et al., 2011). Bullying is of particular concern for racial and ethnic minority youth, who may face greater harm as a consequence of bias-based victimization, in which youth are targeted due to a socially stigmatized identity or appearance, such as gender or sexual identity, race, ethnicity, or immigrant status (Russell, Sinclair, Poteat, & Koenig, 2012). Yet while many aspects of bullying are well-studied among racial and ethnic majority populations, they are under-studied among minority populations.

Existing review papers present important findings on specific racial or ethnic groups (e.g. Albdour & Krouse, 2014; Hong et al., 2014; Patton et al., 2013), prevalence of bullying (e.g. Vitoroulis & Vaillancourt, 2015; Vitoroulis & Vaillancourt, 2018), and bias-based bullying (e.g. Earnshaw et al., 2018). However, to our knowledge, no published review comprehensively integrates current knowledge on how race, ethnicity, and immigration background across cultural contexts more broadly affects bullying involvement and its consequences. As a result, inconsistencies in the literature proliferate and lead to barriers to progress. To address this gap and call attention to the need for more bullying research focused on minority youth, specifically, the present review seeks to integrate recent empirical knowledge and theories into a cohesive understanding of the social, cultural, and psychological forces that affect bullying victimization and perpetration among racial and ethnic minority youth. To do so, we first summarize findings on prevalence rates of bullying involvement among racial and ethnic minorities, discussing the many inconsistencies in findings. Second, we review risk and protective factors uniquely affecting minorities, organizing these factors within a social-ecological framework. Third, we discuss how minorities are differentially affected by bullying victimization and how they perpetrate bullying differently than majority students. We conclude the review by discussing the efficacy of interventions for diverse populations and offering insights and suggestions for future research directions in bullying research.

Bullying Definitions and Scope of Current Review

Bullying occurs when a person “...is exposed, repeatedly and over time, to negative actions on the part of one or more other persons” (Olweus, 1993, p. 9). Bullying also involves an intent to harm and a power imbalance between the perpetrator (the bully or a group of bullies) and the victim (the target of bullying). This definition of bullying behavior is widely but not universally accepted, and many negative behaviors overlap with bullying. Some studies cited measure aggression or harassment but not bullying specifically; these studies were included because aggression and harassment are related to bullying and are incorporated into some definitions of bullying (Volk, Dane, & Marini, 2014). However, aggression or harassment does not always imply repeated negative behavior towards a targeted individual.

In this review, we use the term “bullying involvement” to indicate bullying victimization or perpetration, or both. Youth involved in bullying may be identified as pure bullies, pure victims, or bully-victims, a third category of youth who are simultaneously perpetrators and victims of bullying (Menesini & Salmivalli, 2017). Bullying can be direct or indirect, and can take many forms, including physical (e.g. hitting, shoving, spitting, damaging or stealing property), verbal (e.g. name-calling, threats, teasing, sexual comments), and relational (e.g. social exclusion, spreading rumors) bullying (Monks & Smith, 2006). With advances in technology, cyberbullying has become another serious concern (Smith et al., 2008; Patchin & Hinduja, 2006).

In the present review, we also draw distinctions between race and ethnicity. The construct of race divides people into groups by physical characteristics, while ethnicity is more concerned with shared cultural or national identity (see Betancourt & López, 1993 and Barr, 2008). Race and ethnicity often interact in multifaceted ways, and can be further complicated by factors such as immigration status, class, gender, gender identity, and sexuality. The present review strives to examine racial and ethnic differences in bullying from an intersectional perspective, but findings may be limited by the relative dearth of research on the cumulative effects of multiple stigmatized identities. Immigration background was another major topic in this review. Children who are themselves immigrants (first generation) and children of immigrants (second generation) may experience stressors that native-born minority children may not. Furthermore, different parts of the world may be characterized by political and economic factors that affect immigrants and racial and ethnic minorities (e.g., attitudes toward immigration, differential socioeconomic status among immigrant populations within the same country or region). The current review does not provide extensive context for these differing political and economic ecosystems, and we caution against making direct comparisons between populations. At the same time, we conduct this study with the understanding that migration, race, ethnicity, and class are intricately tied together, and many of the difficulties and strengths associated with belonging to the racial and ethnic minority are shared cross-culturally, regardless of geographic region or local politics.

Methods

The current paper is an integrative, critical review of empirical research concerning the differential effects of race, ethnicity, and immigrant background on bullying involvement and its consequences. Although we conducted a systematic search to guide our process, the broad scope of the review combined with the gaps in the literature made a formal meta-analysis or systematic review both unhelpful and unfeasible. The primary purpose of the systematic search was not to locate and review every relevant paper, but to reduce bias and to uniformly and accurately represent the major findings of the field.

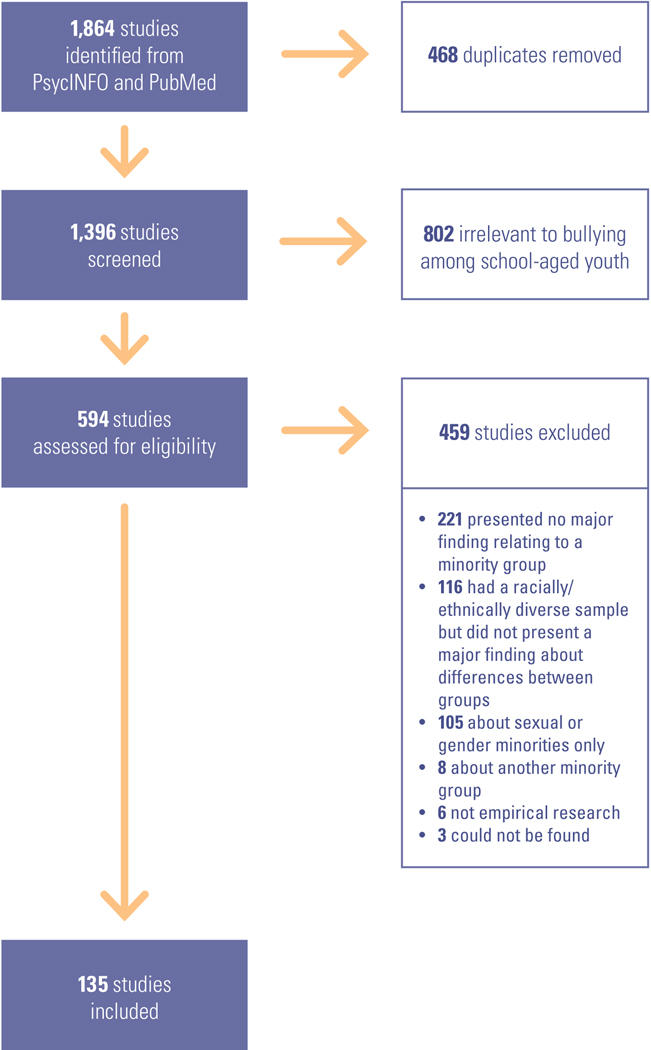

We conducted searches on PubMed and PsycInfo in July of 2019 using search terms relevant to four general areas: bullying (bully* OR OR perpetrat* OR victimiz* OR aggress* OR harass*), diverse populations (racial OR ethnic* OR divers* OR minority OR immigra* OR race), and child or adolescent population (youth OR adolesc* OR child* OR teen* OR student*). These search terms returned 1864 studies, 468 of which were duplicates. The remaining 1,396 studies went through two rounds of screening.

The first round of screening eliminated papers that were not about school-age children or adolescents and that took place outside of an academic or school setting (i.e. workplace harassment, violence among college students or young adults, aggression in inpatient or hospital settings and residential facilities, etc.). We also excluded papers about violence or aggression that did not meet the definition of bullying (i.e. dating violence, parental maltreatment, sexual violence outside of the context of bullying, physical fights and use of weapons, delinquency or criminality, etc.). Papers that were not specifically about bullying, but involved harassment or aggression among peers in a school setting moved on to the second screening. Studies that operationalized aggression as a generalized trait, as opposed to behaviors relating to peer relationships, were not included. A number of other papers were medical papers about physical ailments or treatments (e.g., aggressive periodontitis), or about non-human animals. In total, 802 papers were eliminated in the first screening.

The second screening excluded studies that did not present hypotheses or major findings about racial, ethnic, or cultural group differences. Studies were also excluded if abstracts did not mention major findings relating to immigrant or minority youth, or if the study utilized a diverse sample but did not include a hypothesis contrasting minority youth with majority youth. In total, 459 papers were excluded in the second screening. Three hundred and thirty-seven studies were excluded because they did not present major findings about race, ethnicity, immigrant status, or any kind of minority group, though of these, 116 studies utilized a diverse sample; 105 studies were excluded because they were about gender and sexual minorities but did not include findings about racial or ethnic minorities; and eight studies were about another minority group (e.g., subcultures like goths, disability, weight or body shape, etc.). Six studies were excluded because they were not empirical studies (e.g., summary articles or opinion pieces), and we were unable to locate three papers. The remaining 135 papers are included in the current review.

Articles may also have been identified from citations in papers or reference books returned from search results, or through prior knowledge and recommendation from colleagues. Research from any country was included, though the numerical majority of papers were from the United States, and we made a particular effort to examine race and ethnicity in many differing social contexts. We also reviewed sources that provide context for bullying among racial and ethnic minorities (e.g., theoretical papers and sociological texts).

Prevalence of Bullying Involvement Among Racial and Ethnic Minorities

Studies measuring the prevalence of bullying by race, ethnicity, and immigrant status have yielded mixed results. For this part of the current review, we included papers whose primary purpose was to investigate differences in rates of bullying involvement among racial or ethnic groups and immigrants, as well as papers that indicate major findings about this topic in their abstracts. For this reason, studies reporting no significant differences between groups may be underrepresented due to publication bias and our methodology of screening by abstract.

We found cross-cultural evidence for both higher and lower rates of bullying victimization among racial and ethnic minority and immigrant youth compared to majority groups, as well as no significant differences in victimization rates among racial and ethnic groups (see Table 1). Interestingly, racial or ethnic minorities may face greater risk for bullying victimization from both out-group and in-group peers: in Hungary, both Roma and non-Roma students bullied peers they perceived as Roma more often than peers not identified as Roma (Kisfalusi, Pál, & Boda, 2018). Though some findings suggest less bullying perpetration among racial and ethnic minority groups and immigrants, and a 2018 meta-analysis found small effect sizes between groups (Vitoroulis & Vaillancourt, 2018), researchers more frequently found that minorities perpetrated bullying at higher rates than majority group youth (see Table 1). Importantly, some ethnic minority groups may experience more bullying involvement than majority groups, while others experience less. Despite the lack of consensus on prevalence of general bullying involvement among racial and ethnic minorities, the field has produced more consistent evidence that racial and ethnic minority youth and immigrants are more likely than majority and native-born youth to experience bias-based bullying. Refer to Table 1 for relevant major findings of included papers.

Table 1.

Summary of Studies on Prevalence of Bullying Involvement Among Racial/Ethnic Groups

| Study | Sample | Bullying measures | Major relevant findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| PREVALENCE OF BULLYING VICTIMIZATION | |||

| Greater prevalence of bullying victimization among minority youth | |||

| Berkowitz, De Pedro, & Gilreat (2015) | N = 418,483 middle and high school students in California, U.S. | Behavior-based self-report questionnaires of verbal, physical, and sexual victimization | African Americans (OR = 1.27) were more likely to be classified into the “frequent verbal, physical, and sexual victimization” class compared to White and Latino (OR = 0.82) students, out of four defined latent classes (occasional verbal and physical, verbal and sexual, and no victimization) |

| Bjereld, Daneback, & Petzold (2015) | N = 7,107 7- to 13-year-old children in Nordic countries | Parent-report single-item survey asking “has your child been bullied?” that was coded dichotomously | Immigrant children had higher odds of being bullied than native children in Norway, Sweden, and all Nordic countries surveyed. In Sweden, 8.6% of native children and 27.8% of immigrant children were bullied. |

| Carlyle & Steinman (2007) | N = 79,492 6th-12th grade students in large metropolitan area in the U.S. | Behavior-based self-report of bullying vict. & perp. | 27.5% of Native Americans were victims of bullying, which were higher rates than that endorsed by White, African American, Hispanic, or Asian students (ranging from 16.5%−19.6%) |

| Goldweber, Waasdorp, & Bradshaw (2013) | N = 10,254 middle school youth in the U.S. | Behavior-based self-report of bullying vict. & perp. | Compared to White and Hispanic youth, African American Black youth were more likely to be in the victim (probability of 46%) or bully-victim (45%) classes than in the low-involvement class (7%). |

| Jansen et al. (2016) | N = 8,523 children in Rotterdam, the Netherlands | Behavior-based teacher reports of bullying vict. & perp. | Children with a non-Dutch background were more likely to be victims (AOR = 1.41) or bully-victims (AOR = 1.41) than children of Dutch origin. |

| Malta et al. (2014) | N = 109,104 adolescents from the National Adolescent School-based Health Survey in Brazil | Behavior-based self-report of bullying vict. & perp. | Black (OR = 1.15) and Indigenous (OR = 1.16) adolescents had greater likelihood of experiencing bullying victimization than White, mulatto, and Asian students. |

| Maynard, Vaughn, Salas-Wright, & Vaughn (2016) | N = 12,098 school-aged children in the U.S. | Behavior-based self-report of bullying victimization that provides definition of bullying and refers to behavior as bullying | Non-Hispanic White immigrant youth (OR = 1.96) and Non-Hispanic Black immigrant youth (OR = 2.39) were more likely to be bullied than native-born youth. |

| Mouttapa, Valente, Gallaher, Rohrbach, & Unger (2004) | N = 1,368 6th graders in southern California, U.S. | Behavior-based self-report of bullying vict. & perp. | Asian youth (AOR = 1.57) were more likely to be victimized compared to Hispanic (AOR = 1.41) youth. |

| Pottie, Dahal, Georgiades, Premji, & Hassan (2015) | Systematic review including 18 studies from the U.S., the Netherlands, Israel, and France | Across cultures, first-generation immigrants experience peer victimization at higher rates than third-generation and native-born youth. | |

| Strohmeier, Kärnä, & Salmivalli (2011) | N = 4,957 9- to 12-year-old children in Finland | Behavior-based self-report of victimization prefaced by a definition of bullying & behavior-based peernomination | First- (M = 0.36) and second-generation (M = 0.36) immigrant youth scored higher on a 0- to 1-point bullying victimization scale than native youth (M = 0.25) by both self- and peer-report. Physical, racist, and sexual victimization were more common in both immigrant groups than in the native group. |

| Sulkowski, Bauman, Wright, Nixon, & Davis (2014) | N = 2,929 youth who endorsed victimization two times a month or more in the U.S. | Behavior-based self-report of peer victimization | More immigrant youth (33%) reported experiencing physical aggression than non-immigrant youth (22%), and they were also more likely to be victimized because of their race, religion, or family income. |

| von Grünigen, Perren, Nägele, & Alsaker (2010) | N = 1,090 kindergarten-age children in German-speaking Switzerland | Definition-based teacher report of bullying victimization, preceded by a workshop about bullying | Having an immigrant mother predicted more frequent bullying victimization than native Swiss parents (B = 0.62). |

| Kisfalusi, Pál, & Boda (2018) | N = 347 students in Hungary across 4 schools | Nominations of which peers participants bullied based on questions about behavior | Both Roma (β= 0.42) and non-Roma students (β = 0.53) reported bullying peers they perceived as Roma more often than peers not perceived as Roma. |

| Greater prevalence of bullying victimization among majority youth | |||

| Blake, Zhou, Kwok, & Benz (2016) | N = 2,870 adolescents with disabilities in the U.S. | Single-item definition-based self-report of bullying vict. & perp. | White students were more likely to be bully-victims than Black (OR = 0.14), Hispanic (OR = 0.06) or other race (OR = 0.12) students, and also more likely to be victims than Black students (OR = 0.13). |

| Feinstein, Turner, Beach, Korpak, & Phillips (2019) | N = 18,515 bisexual youth in the U.S. | Definition-based self-report of bullying victimization | White youth reported bullying at higher rates (40.7% reported in-person bullying; 31.4% reported electronic bullying) than African American (21.8%; 18%) and Hispanic (25.2%; 21.7%) bisexual youth. |

| Fisher, Middleton, Ricks, Malone, Briggs, & Barnes (2015) | N = 4,581 middle school U.S. White and African American students | Behavior-based self-report of bullying victimization | White students were bullied at significantly higher rates than African American students (β = .28) |

| Kawabata & Crick, 2013 | N = 232 4th grade White and Asian American students in the U.S. | Behavior-based peer nomination of bullying perpetration of peer physical and verbal aggression | Association between ethnicity and nominations for experiencing peer victimization was stronger for Asian American students (β = 0.21) than White students (β = 0.35) such that Asian American students were less often identified as victims. |

| Mehari & Farrell (2015) | N = 4,593 sixth grade students in the U.S. | Behavior-based self-report of overt and relational victimization | White students (R2 = −0.08) reported lower frequency of overt victimization than African American students (reference group), but not for relational victimization. Hispanic students reported victimization at similar rates as African American students. |

| Strohmeier & Spiel (2003) | N = 568 native and immigrant children in Austria | Definition-based peer nomination of bullying vict. & perp. | 9.0% of native Austrian children, 5.1% of the Turkish/Kurdish children, and 1.6% of the former Yugoslavian children were nominated as bullying victims. |

| Tippett, Wolke, & Platt (2013) | N = 4,668 10- to 15-year-old youth in the U.K. | Self-report of bullying vict. & perp. that identifies certain behaviors as “bullying” | Indian (OR = 0.53), Bangladeshi (OR = 0.40), and African youth (OR = 0.27) were more likely to be bullied than White youth while there were no significant differences for Pakistani, other Asian, and Caribbean youth (though all groups still reported less bullying victimization than White youth). |

| Wang, Iannotti, & Nansel (2009) | N = 7,182 6th through 10h grade U.S. adolescents | Definition-based self-report of bullying vict. & perp. | African American adolescents were less likely to be victims of verbal (OR = 0.77) and relational bullying (OR = 0.70), but not physical or cyber bullying, than White adolescents. |

| No significant difference in bullying victimization between ethnic groups or mixed rates between groups | |||

| Connell, Sayed, Gonzalez, & Schell-Busey (2015) | N = 3,965 middle school students in northeastern U.S. | Behavior-based self-report of bullying vict. & perp. | No substantial differences in bullying victimization rates were reported between White (71%), African American (75%), Latino (70%), and Asian (66%) students. |

| Hanish & Guerra (2000) | N = 1, 956 elementary-age children in the U.S. followed up after 2 years | Peer nomination based on two questions: who gets picked on and who gets pushed and hit | Hispanic students (M = 0.20) were less likely to be victimized than White (M = 0.24) and African American (M = 0.24) students. |

| Kljakovic, Hunt, & Jose (2015) | N = 2,174 adolescents from 78 schools across northern New Zealand | Definition-based self-report of bullying vict. & perp. | Bullying victimization rates were relatively similar across ethnic groups, but Maōri adolescents were more likely to experience victimization via text message (but not in-school, outside of school, or internet victimization) than New Zealand European and other ethnicity groups.* |

| Llorent, Ortega-Ruiz, & Zych (2016) | N = 2,139 adolescents in secondary schools in the south of Spain | Behavior-based self-report of bullying vict. & perp. | No significant differences in bullying victimization rates between racial minority and majority groups. |

| Mueller, James, Abrutyn, & Levin (2015) | N = 75,344 U.S. adolescents, of whom 5,541 self-reported as lesbian, gay, or bisexual | Single-item definition-based self-report of bullying victimization | While White and Hispanic sexual minority youth were bullied more frequently than White heterosexual youth, Black sexual minority youth were bullied at the same rates as White heterosexual youth. Furthermore, Black and Hispanic heterosexual youth were bullied less than White heterosexual youth.* |

| Rhee, Lee, & Jung (2017) | N = 2,799 adolescents in California, U.S. | Single-item behavior-based bullying victimization (operationalized as threatening to hurt) | African American youth reported the highest rates of bullying victimization (24%) and Asian American youth the lowest (6.5%) compared to White (17.5%) and Latino (15.2%) adolescents. |

| Seals & Young, 2003 | N = 454 7th and 8th grade students in the U.S. | Definition-based self-report of bullying with examples of bullying scenarios | No significant difference in involvement based on ethnicity. |

| Vitoroulis & Vaillancourt, 2015 | Meta-analysis of 105 international studies from 1990 to 2011 | Analyses revealed small effect sizes for the impact of ethnic group membership on rates of bullying victimization (range d = ±0.02 to ±0.08) | |

| Wang, Iannotti, Luk, & Nansel (2010) | N = 7,475 6th through 10th grade U.S. adolescents | Definition-based self-report of bullying vict. & perp. | No significant differences in latent class membership (all types victims, verbal/relationship victims, or not victims) based on race/ethnicity. |

| PREVALENCE OF BULLYING PERPETRATION | |||

| Greater prevalence of bullying perpetration among minority youth | |||

| Carlyle & Steinman (2007) | N = 79,492 6th-12th grade students in large metropolitan area in the U.S. | Behavior-based self-report of bullying vict. & perp. | 27.7% of African Americans and 30.9% of Native Americans endorsed repeated bullying perpetration behaviors, which were higher rates than that endorsed by White (15.5%), Hispanic (17.4%), and Asian (11.6%) students. |

| Connell, Sayed, Gonzalez, & Schell-Busey (2015) | N = 3,965 middle school students in northeastern U.S. | Behavior-based self-report of bullying vict. & perp. | Prevalence of bullying perpetration among African Americans (56%) was highest compared to White (44%), Latino (47%), and Asian (41%) students. |

| Espelage, Hong, Kim, & Nan, 2018 | N = 310 6th and 7th grade students in midwestern U.S. | Behavior-based self-report of peer victimization perpetration | Non-White students were more likely to perpetrate non-physical bullying (B = 0.31) compared to White students. |

| Fandrem, Ertesvåg, Strohmeier, & Roland, 2010 | N = 156 native and immigrant secondary school students in an urban schools in Oslo, Norway | Definition-based self-report of bullying vict. & perp. | Immigrant boys were more often in the bullying group than in the non-bullying, and nearly all immigrant boys were bullies. Immigrant girls were underrepresented in the bullying group and overrepresented in the non-bullying group.* |

| Fandrem, Strohmeier, & Roland, 2009 | N = 3,127 native and immigrant 8th, 9th, and 10th grade students in Norway | Definition-based self-report of bullying vict. & perp. | Compared to native children in Norway (M = 0.36), immigrant children (M = 0.46) were significantly more likely to be bullying perpetrators. |

| Jansen et al. (2016) | N = 8,523 children in Rotterdam, the Netherlands | Definition-based teacher-report of bullying vict. & perp. with concrete examples. | Children with a non-Dutch background were more likely to be bullies (AOR = 1.38) or bully-victims (AOR = 1.38) than children of Dutch origin. |

| Kisfalusi, Pál, & Boda (2018) | N = 347 students in Hungary across 4 schools | Behavior-based self-report and peer nominations of bullying perpetration | Roma students self-reported being bullies (M = 1.99) and were nominated for being bullies by peers (M = 1.37) at higher rates than non-Roma students (M = 1.60 self-report; M = 0.97 peer nomination). |

| Kljakovic, Hunt, & Jose (2015) | N = 2,174 adolescents from 78 schools across northern New Zealand | Definition-based self-report of bullying vict. & perp. | Bullying perpetration rates were significantly different across ethnic groups, with Mari adōlescents more likely to perpetrate bullying in person at school and via text message (but not outside of school or internet bullying) than New Zealand European and other ethnicity groups.* |

| Llorent, Ortega-Ruiz, & Zych (2016) | N = 2,139 adolescents in 22 secondary schools in the south of Spain | Behavior-based self-report of bullying vict. & perp. | Ethno-cultural minority students (M = 2.83) were more involved in bullying perpetration than majority students (M = 2.26), but not cyber bullying. |

| Sykes, Piquero, & Giovanio (2017) | Weighted N = 16,837, 733 U.S. adolescents | Single-item parent report | Hispanic and African American students are more likely than White peers to be bullies.* |

| Tippett, Wolke, & Platt (2013) | N = 4,668 10- to 15-year-old youth in the U.K. | Self-report of bullying vict. & perp. that identifies certain behaviors as “bullying” | Pakistani (OR = 3.32) and Caribbean youth (OR = 2.74) were more likely to be bullies than White youth while there were no significant differences for Indian, Bangladeshi, other Asian, and African youth (though all groups except other Asian still reported greater bullying perpetration than White youth). |

| Wang, Iannotti, & Nansel (2009) | N = 7,182 6th to 10th grade U.S. adolescents | Definition-based self-report of bullying vict. & perp. | African American adolescents were more likely to perpetrate physical (OR = 1.60), verbal (OR = 1.52), and cyber bullying (OR = 1.74), than White adolescents. Hispanic adolescents were more likely to perpetrate physical bullying (OR = 1.39) and be cyber bully-victims (OR = 1.56). |

| Greater prevalence of bullying perpetration among majority youth or no significant differences | |||

| Almeida, Johnson, McNamara, & Gupta (2011) | N = 1,348 high school students in Boston, U.S. | One- to two-item behavior-based self-reports of physical, relational, and verbal/emotional aggression/violence toward peers | Recent immigrant youth (19%) had a significantly lower prevalence of peer violence perpetration than third-generation (43%), second-generation (39%), or immigrant youth who had lived in the U.S. for over four years (42%). No significant differences in relational or verbal/emotional peer aggression. |

| Kawabata & Crick, 2013 | N = 232 4th grade White and Asian American students in the U.S. | Behavior-based peer nomination of bullying perpetration of peer physical and verbal aggression | Association between ethnicity and nominations for perpetrating peer victimization was stronger for Asian American students (β = 0.29) than White students (β = 0.06) such that Asian American students were less often identified as aggressors. |

| Strohmeier & Spiel (2003) | N = 568 native and immigrant children in Austria | Definition-based peer nomination of bullying vict. & perp. | 11.8% of native Austrian children, 7.2% of the former Yugoslavian children, and 3.8% of the Turkish/Kurdish children were nominated as bullies. |

| Vitoroulis & Vaillancourt, 2018 | Meta-analysis of 53 studies | Meta-analysis found small, non-significant differences in bullying perpetration rates between immigrant and non-immigrant youth, and between visible minority and majority students. | |

| PREVALENCE OF BIAS-BASED BULLYING | |||

| Boulton, 1995 | N = 156 children in the U.K. | Peer nomination based on definition of bullying. Smaller sample asked to specify type of bullying and race of bully. | While ethnic majority and minority students experienced roughly equal rates of bullying victimization, Asian students reported being teased about their race or color more often than White students.* |

| Cooc & Gee (2014) | N = 5,000 12- to 18-year old U.S. adolescents, approximately, every other year from 2001 to 2011 | Self-report on bullying and race- or ethnic-based victimization, definition-based and behavior-based | Asian Americans were less likely to report experiencing bullying, but more likely to report race-based victimization (9%) compared to White students (4%). |

| Durkin, Hunter, Levin, Bergin, Heim, & Howe (2012) | N = 925 8- to 12-year-olds in Britain | Behavior-based self-report of experiencing peer aggression and discriminatory aggression | Overall, minority children (16%) experienced

greater discriminatory aggression than majority children (7%). However,

while minority children experienced greater discriminatory aggression

when ethnic minorities were less than half the school population, but

when the school concentration of minorities exceeded 81%, majority

students experienced greater discriminatory aggression. |

| Fisher, Middleton, Ricks, Malone, Briggs, & Barnes (2015) | N = 4,581 middle school U.S. White and African American students | One-item self-report about teasing due to race/ethnicity or skin color | White students reported greater rates of race-based bullying victimization than African American students (β = 1.25) when controlling for gender and school ethnic composition. White students reported greater rates of race-based bullying when they were numerical minority than when African American students did when they were the minority, while African American students reported rates of race-based bullying when they were the numerical majority than White students did when they were the majority (β = −0.02). |

| Moran, Smith, Thompson, & Whitney (1993) | N = 66 White and Asian children in the U.K. | Definition-based self-report of bullying vict. & perp. | While Asian (36.4%) and White children (39.4%) reported similar rates of bullying victimization in general, 50% of Asian children reported race-based bullying (racist name-calling), while no White children reported racist bullying. |

| Verkuyten & Thijs (2002) | N = 2,851 primary school students in the Netherlands | Behavior-based self-report of experiencing racist victimization | 33–42% of Turkish, Moroccan, and Surinamese elementary age students reported racist name-calling and 26–30% of them reported ethnic exclusion. These rates were significantly higher than 21% of Dutch students who reported racist name-calling and 19% who reported ethnic exclusion. |

All statistics reported are significant at the p < 0.05 level or lower where relevant. OR comparison groups are White, racial or ethnic majority, or native-born youth unless specified.

Behavior-based surveys of bullying involvement include a list of behaviors (i.e. “I was pushed or shoved; ” “I was teased or called names”) that participants endorse or do not endorse individually, usually by indicating the frequency. They do not name the behaviors as “bullying,” unless otherwise noted. Definition-based surveys present a definition of bullying and participants endorse bullying victimization and/or perpetration based on this description. They may be single-item surveys or may include a list of behaviors or contexts.

Statistics omitted due to space restraints. See original paper for more accurate reports.

Factors contributing to mixed reports of bullying.

Inconsistencies in study reports of bullying prevalence among racial and ethnic minority groups suggest that race and ethnicity alone may not be adequate predictors of bullying involvement, and other factors such as socioeconomic status might have more predictive power. These inconsistencies may also be explained by a number of considerations, including measures of bullying behavior, differing cultural values affecting reporting, density of ethnoracial minority populations in schools, and differing political and economic contexts across countries and regions. We discuss the first two in this section and the latter three in the section of the current review dedicated to risk and protective factors in the school environment.

Measuring bullying behaviors poses a unique challenge, especially when working with diverse populations. Immigrants and racial and ethnic minorities may report bullying at differential rates compared to the bullying behaviors they actually experienced. A 2018 study found that minority and male students report bullying victimization at lower rates than White and female students on a definition-based measurement of bullying, despite reporting experiencing bullying at similar rates as White and female students on a behavioral measurement that does not use the word “bullying” (Lai & Kao, 2018). In a study of 24,345 students from 107 Maryland public schools, the prevalence of bullying differed based on how it was assessed. African-American boys and girls and Asian-American boys were more likely than White youth to underreport victimization when they were answering a one-question, definition-based survey as opposed to questions about specific behaviors associated with bullying (Sawyer, Bradshaw, & O’Brannon, 2008). In another study, African American adolescents reported similar levels of victimization to a school counseling center as Hispanic and Asian American/Pacific Islander students, but were less likely to report experiencing bullying (Lewis et al., 2015). Though the study did not explicitly investigate students’ understanding of the word “bullying,” some racial and ethnic minorities may be less willing to identify with the label.

For minority students, cultural differences and social norms may inform how they perceive and identify with the label “bullying,” resulting in rates of reporting that are not commensurate to the amount of bullying they actually experience. Triandis (1976) theorized that different ethnic groups may interpret cultural values and norms in differing ways. Minority groups may feel pressure to appear invulnerable or experience stronger stigma against bullying and may be less willing to link their own experiences and behaviors to the word (Phelps, Meara, Davis, & Patton, 1991; Sawyer et al., 2008). As such, it is imperative that researchers consider these cultural differences and select or construct measurement methods that are sensitive to norms and beliefs among ethnic minority cultures. A few measures of bullying perpetration and victimization have been designed and validated for cross-cultural use. The Self-Report of Victimization and Exclusion (SVEX), validated with Latino and White youth, is a measure of overt and relational bullying that includes an expanded set of exclusion behaviors that may be relevant for developmental and cross-cultural use (Buhs, McGinley, & Toland, 2010). The European Bullying Intervention Project Questionnaire–Ethnic-Cultural Discrimination Version (EBIPQ–ECD) is a measure of discriminatory bullying victimization and aggression, validated in a sample of 27,367 Spanish adolescents (Rodríguez-Hidalgo, Calmaestra, Casas, & Ortega-Ruiz, 2019). Bullying researchers should consider using such validated and psychometrically sound measures, adapt and validate existing measures for cross-cultural use, or design new ones to gather more accurate data across different racial, ethnic, and cultural groups.

Risk and Protective Factors for Bullying Involvement in Racial and Ethnic Minorities

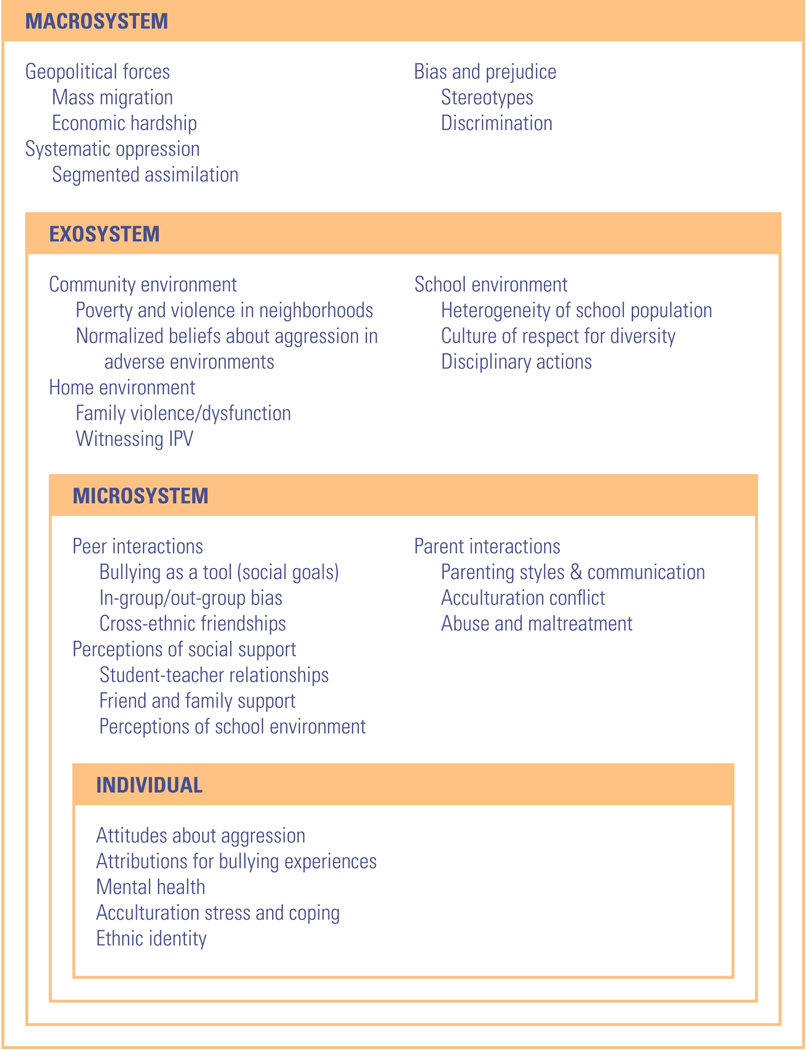

In this section, we organize knowledge about factors that increase risk for, or protect against, bullying involvement in minority youth within a social-ecological framework, a systems approach to development that emphasizes the interaction of distal and proximal factors that influence youth behavior and development (Bronfenbrenner, 1979). Adapted to theoretical explanations of bullying involvement by previous research (e.g. Earnshaw et al., 2018; Hong & Espelage, 2012), this model suggests that children are nested within multiple systems that interact to influence their development.

The two most distal layers that we focus on are the macrosystem and exosystem layers, which encompass broad societal and cultural influences (macrosystem) and the settings (exosystem) minority youth grow up in – settings that are themselves influenced by such macrosystem factors as cultural ideologies and institutionalized racism. The more proximal layers are the microsystem, which includes factors related to the daily interpersonal interactions of minority youth, and the individual layer, describing certain within-person factors that research suggests play a role in bullying involvement. In the process of examining these distal and proximal minority-specific risk and protective factors, we integrate empirical research findings with critical theories to confer a deeper understanding of the social and psychological forces that influence bullying behavior in minority youth. See Figure 2 for an overview of risk and protective factors organized into an ecological framework.

Figure 2.

Summary of risk and protective factors organized within an ecological framework

Macrosystem and Exosystem Influences: Oppression, Neighborhoods, and Violence

Critical race theory recognizes that racism is pervasive in the dominant culture and institutionalized racism perpetuates the marginalization of people of color. That is, racial and ethnic minorities must often contend with macrosystem influences such as historical legacies and current structures of oppression that have legal and economic ramifications. The effects of these macrosystem forces are contextual factors such as poverty and socioeconomic status, and they trickle down to the exosystem level, creating adverse environments for minorities, including violence in neighborhoods, family conflict, intergenerational transmission of trauma, etc. (Haynie, Silver, & Teasdale, 2006; Lareau, 2011; Lauritsen & White, 2001; Widom, 1989). In turn, negative behaviors and outcomes associated with poverty and trauma reinforce discrimination and social stigma (Delgado & Stefancic, 2012). Given that racial and ethnic minorities disproportionately live in high-risk neighborhoods, they also face greater health and behavior risks associated with these adverse environments, including bullying involvement (Cook et al., 2010).

Community environments.

A 2013 study found that being African American (vs. White) significantly predicted gang involvement and carrying guns to school. Bullies and bully-victims (vs. non-bullies) also had higher odds of being involved with gangs and carrying guns to school, indicating overlaps in risk factors between African American and bully groups (Bradshaw, Waasdorp, Goldweber, & Johnson, 2013). Living in environments where violence is common and encouraged or accepted may put immigrant and minority youth at risk for behaving aggressively. Chronic exposure to violence and perceived neighborhood threats are associated with the belief that aggressive behavior is a viable way to resolve conflict, with endorsing such behavior, and with acting aggressively (Coie & Dodge, 1996; Colder, Mott, Levy, & Flay, 2000). For example, in the United States, African American youth were more likely than White youth to endorse beliefs that support fighting (Farrell et al., 2012), and they were more likely to be perceived as aggressive compared to their White peers (Graham, Bellmore, & Mize, 2006). Perception of certain groups as more aggressive may lead to the completion of a self-fulfilling prophecy: others may behave in ways that elicit aggressive behaviors from those they stereotype as aggressive (e.g., Rist, 1970; Zimmerman, Khoury, Vega, Gil, & Warheit, 1995).

Importantly, research suggests that poverty in neighborhoods, rather than concentration of minorities or immigrants in those neighborhoods, is the primary cause of greater behavioral risks like poor adjustment and friendship with deviant peers (Chung & Steinberg, 2006; Haynie et al., 2006; Leventhal & Brooks-Gunn, 2000; Nishina and Bellmore, 2018). Disadvantages associated with poor neighborhood quality and poverty may cause poor psychosocial adjustment in addition to self-fulfilling negative stereotypes and beliefs that aggression is acceptable. A 2017 study in the U.S. found that non-White youth lived in more disadvantaged neighborhoods than their White peers, non-White youth were more likely to be bullies than their White peers, and that bullies on average experienced a greater number of disadvantages (e.g. neighborhood quality and disorder, lack of social cohesion, parental incarceration, witnessing IPV, and other adverse childhood experiences) than non-bullies (Sykes, Piquero, & Giovanio, 2017). These findings illustrate the cumulative and cascading effects of community environment on bullying involvement.

School context.

Adverse community environments also impact school environments. For example, African American students attending large, urban schools serving students of a lower socioeconomic status—i.e., those living in low-income areas—were more likely to be exposed to high aggression in classrooms (Thomas, Bierman, & CPPRG, 2006). Community and school contexts may interact to put racial and ethnic minorities at higher risk for bullying involvement.

Concentration of immigrants and racial and ethnic minority students can affect bullying involvement. A high (versus low) density of minority students and immigrants may be protective against bullying victimization for racial and ethnic minorities and immigrants. In a study of 1,449 5th-through-8th-grade students in Canada, immigrants and children of immigrants were victimized significantly less often in schools with high (versus low) concentrations of immigrants (Vitoroulis & Georgiades, 2017). Additionally, White students at predominantly non-White schools were at significantly higher risk for victimization than White students at majority-White schools in the U.S. (Fisher et al., 2015; Hanish & Guerra, 2000). Similarly, a study in the U.K. found that ethnic minority students experienced greater levels of discriminatory aggression until the school’s minority concentration exceeded 81%, after which White students experienced more discriminatory aggression (Durkin et al., 2012). Such findings suggest that racial and ethnic representation in schools affects who may experience bullying victimization (Schumann, Craig, & Rosu, 2013).

At the same time, increased heterogeneity in school environments may also increase violence and conflict overall, depending on school-wide attitudes about diversity. Conflict may increase as student populations become more diverse if schools do not foster a culture of respect for differences; bullying is more common in more heterogeneous schools for all students. In ethnically heterogenous classrooms, bullying victimization was more common, and ethnic minorities were also more likely to bully than they were in homogenous classrooms (Vervoort, Schulte, & Overbeek, 2010). Similarly, peer victimization was less frequent in Greek schools with high or low minority density compared to schools with moderate minority density, defined as having 26–75% ethnic minority students (Serdari, Gkouliama, Tripsianis, Proios, & Samakouri, 2018). Ethnic harassment was also more likely to occur in classrooms with greater ethnic diversity among students in Sweden (Bayram Özdemir, Sun, Korol, Özdemir, & Stattin, 2018). This evidence suggests that heterogeneity of schools causes more inter-group conflict, leading to increased bullying involvement.

However, concentration of immigrants and racial and ethnic minorities in schools explain only some of the variance in bullying involvement prevalence. The social environment in classrooms and schools can be equally or more important. Walsh et al. (2016) found that higher concentration of immigrant students in schools was linked to greater rates of bullying perpetration (among both immigrants and non-immigrants) but lower rates of victimization in immigrant youth. However, they also found classroom support strengthened or weakened those relationships, such that it was a greater influence on school violence than immigrant concentration. To this end, respect for diversity and for differences between students is associated with decreased reports of bullying (Gage, Prykanowski, & Larson, 2014). Maintaining a balance of diverse representation in a student population, while promoting a culture of respect, can be protective against bullying. Congruently, negative perceptions and expectations about minority or immigrant students may have harmful effects on bullying and school culture.

Home environment.

Studies have linked family violence and witnessing intimate partner violence (IPV) with concurrent bullying perpetration in children (Grant, Merrin, King, & Espelage, 2018; Baldry, 2003; Voisin & Hong, 2012). A study of 1,050 children in South Africa found that witnessing IPV was a primary risk factor for aggressive behavior and bullying peers, even after controlling for factors such as food insecurity and orphanhood status (Cluver, Bowes, & Gardner, 2010). Another study following a large cohort of youth in the U.K. over two years confirmed the predictive strength of witnessing IPV on bullying behavior, even above socioeconomic status (Bowes et al., 2009). In particular, witnessing IPV may be most predictive of physical forms of bullying perpetration (Bauer et al., 2006).

One theoretical explanation for the link between witnessing violence at home and bullying perpetration in children is social learning theory, which posits that children model behavior from others, particularly authority figures like adults and parents (Bandura & Walters, 1977; Low & Espelage, 2013). Parental and authority figures are important models for healthy development in youth. Those growing up in economically disadvantaged communities where family conflict, violence, and other risk factors are common—which are disproportionately racial and ethnic minorities—may be socialized to accept and even model these behaviors in their relationships outside of the home, as well.

Bias and prejudice.

Various racial and ethnic groups may experience bullying victimization at similar rates, but minority groups tend to experience more racist or bias-based bullying (Wang, Wang, Zheng, & Atwal, 2016; Boulton, 1995; Mooney, Creeser, & Blatchford, 1991). Youth may use identifiers such as race, language, and cultural norms to divide themselves into social groups that then experience inter-group conflict (Tajfel, 1978; Tajfel & Turner, 1979; Vitoroullis & Valliancourt, 2015). Qualitative studies on ethnic-based harassment and bullying among ethnic minority youth in Northern Island (Connolly & Keenan, 2002) and Arab Americans (Albdour, Lewin, Kavanaugh, Hong, & Wilson, 2017) may provide further context for what bias-based bullying might look like. First- and second-generation Asian students in the United States cite language barriers, different appearance, and immigrant status as common reasons for being bullied (Qin, Ray, & Rana, 2008). Sikh students also reported that they experienced peer victimization because they were perceived to be foreigners and because they wore head coverings (Atwal & Wang, 2019). That is, being seen as a foreigner or outsider, regardless of nativity, can be associated with higher risks of bullying victimization.

Minority students who do not conform to their group’s stereotypes are at higher risk of victimization. For example, African American youth who are not athletic or Asian Americans who do not excel academically may be bullied more than those who do conform to these stereotypes (Peguero & Williams, 2013; Wang et al., 2016). Asian American students, who are stereotyped to be less aggressive than their peers, were more likely than their White peers to be victimized by peers if they were aggressive (Menzer, Oh, McDonald, Rubin, & Dashiell-Aje, 2010). From an opportunity theory perspective, Peguero, Popp, and Koo (2015) suggest that racial and ethnic minority students are at greater risk for victimization at school than majority students when they conform to the standards of the majority through academic or athletic success (i.e., “acting White”). Indeed, African American, Latino American, and Asian American students were more likely to be victimized at school if they were more involved in academic extracurricular activities, while there was no effect for White students. Furthermore, Asian American and Latino American students were more likely to be victimized if they were involved in athletic extracurricular activities, while African American and White students were less likely to be victimized (Peguero, Popp, & Koo, 2015). Peguero and Jiang (2016) replicated these findings, reporting African American and Latino American students were more likely to be victimized if they were more academically successful or involved, and if they were friends with White students.

Bullying does not occur only between individuals belonging to different social groups, or between minority and majority groups. Intra-cultural pressure and conflict can be particularly painful for racial and ethnic minorities. For example, Black girls accusing other Black girls of “acting White” can be seen as a form of bullying victimization that is associated with significant social anxiety (Davis, Stadulis, & Neal-Barnett, 2018). Additionally, a qualitative study found that Mexican American students consistently bullied Mexican immigrants, and that the bullying was associated with perceived superiority and language barriers (Mendez, Bauman, & Guillory, 2012). In the U.K., children of ethnic minority groups were more likely to be bullied by members of other ethnic minority groups than by White peers: Hindus were most frequently bullied by Pakistanis, while Indian Muslims and Pakistanis were most frequently bullied by Hindus. Furthermore, the content of the bullying behaviors were tied to religious beliefs and cultural practices, e.g., which God was worshipped, clothing, etc. (Eslea & Mukhtar, 2000).

The unique socioeconomic backgrounds of immigrants and children of immigrants may contribute to differential rates of bullying involvement. For example, findings from a 2009 study suggest that third-generation Latino students tend to be bullied more than first- or second-generation Latino students. Meanwhile, first- and second-generation Asian children are more likely to be victimized than third-generation Asian Americans. First-generation immigrants (both Asian and Latino) are more likely to be afraid at school than are native-born White Americans (Peguero, 2009). This complex pattern of victimization and fear among immigrant groups might be explained by segmented assimilation theory, which posits that differing social, economic, and political contexts lead to three differing levels of social and economic success among immigrants and their descendants. One group is defined by acculturation and integration into the White middle class, another remains in a cycle of poverty and downward assimilation, while a third quickly advances economically while deliberately retaining culture of origin values and community (Zhou, 1997). Membership to one of these three general classes, as well as generational level of assimilation, may predict how immigrant children and children of immigrants are perceived and treated, leading to differing levels of bullying involvement. Latino American children of immigrants may experience greater levels of adjustment difficulties and stigmatization associated with downward assimilation, while Asian Americans benefit from the “model minority” stereotype (though this stereotype is also harmful in its other ways), leading to differential rates of bullying involvement.

Microsystem & Individual Levels: Social and Cognitive Predictors of Bullying Involvement

Peer interactions.

As discussed earlier in this review, the challenges faced in the adverse environments created by macrosystem-level influences may shape beliefs in minority youth that aggression is a viable or permissible way to deal with conflict (Coie & Dodge, 1996; Graham & Echols, 2018), and this belief may extend to peer contexts. Indeed, aggressive behaviors were associated with increased perceived popularity and leadership in urban, high-risk environments (Waasdorp, Baker, Paskewich, & Leff, 2013). Aggression is also positively correlated with popularity in Black-majority classrooms in the United States (Rodkin, Farmer, Pearl & van Acker, 2000). Although popularity has been linked with both prosocial behavior and aggression (Luthar & McMahon, 1996; Kornbluh & Neal, 2016), popular White boys were more likely to be prosocial while popular African-American boys were more likely to be “tough,” or aggressive, as perceived and rated by peers (Rodkin et al., 2000). Popularity associated with aggression can act as a reward for such behavior, exacerbating bullying in classrooms, and concordantly, aggression can be used by bullies as a tool to achieve social goals such as social acceptance and popularity (Salmivalli, 2010).

In addition, research on friendships among children and adolescents provide evidence for in-group bias theory. Race and ethnicity are common identifiers used to determine social groups and form friendships (Aboud, Mendelson, & Purdy, 2003), and youth are more likely to become friends with or accept other youth who belong to the same racial or ethnic group and reject those who belong to a different one (Bellmore, Nishina, Witkow, & Juvonen, 2007). Furthermore, immigrant adolescents might be more likely to associate with peers within their own ethnic community due to acculturation-related factors (Titzmann, 2014). Classroom-level acceptance or rejection of individual students has also been found to be affected by racial demographics of the classroom, with Black peers more accepted in classrooms with a higher concentration of Black students (Jackson, Barth, Powell, & Lochman, 2006). Social identity theory provides a framework through which to view racist or bias-based bullying among children, who may link perceived threat to their in-group with their self-esteem, and have negative associations or behavior toward out-group members (Tajfel, 1978; Tajfel & Turner, 1979; Vitoroullis & Valliancourt, 2015). As threats or perceived threats arise (e.g., racial dynamics in classrooms, political opinions expressed by parents and media, etc.), youth may identify themselves more strongly to the status of their in-group, and they may seek a boost to their self-esteem by acting negatively toward out-group members. For example, a study of British children found that discriminatory aggression increased as concentrations of minority students in schools increased (Durkin et al., 2012). Furthermore, individual aggression among children and adolescents are affected by socio-political events and exposure to violence in the media. To illustrate, a study found that among Israeli and Palestinian youth, exposure to ethno-political violence predicts greater aggression two years later. The relationship was mediated by changes in normative beliefs about aggression, aggressive social scripts, and emotional distress due to exposure (Huesmann et al., 2017). Race, ethnicity, and immigration status may be strong dividing factors in school and classroom environments, causing segmentation in the student body that deepens as perceived threats rise and social relationships form as a result of bullying behaviors.

Being part of the majority group may have certain disadvantages as well. Belonging to the numerical majority in Californian schools with a Latino or Asian majority population made students vulnerable to greater victimization if their friends were victimized more over the course of an academic year (Echols & Graham, 2016). The authors of the study suggest this may be because belonging to the majority group increases status and visibility, so when majority students associate with low-status individuals, they are more likely to be victimized because they stand out more. Alternatively, majority youth may suffer greater consequences because they cannot attribute victimization to prejudice and believe that they were at fault for their own victimization (Echols & Graham, 2016; Graham, Bellmore, Nishina, & Juvonen, 2009).

At the same time, cross-ethnic friendships and respect for diversity are strong protective factors against bullying involvement. Friendships between members of different racial or ethnic groups uniquely predicted decreases in relational victimization. Furthermore, in classrooms that were more ethnically diverse, cross-racial/ethnic friendships were associated with decreased physical victimization and increased social support (Kawabata & Crick, 2011).

Perceptions of social support.

Research has indicated that compared to White students, Black and Hispanic students in the United States reported poorer relationships with adults, lower connectedness with their schools, fewer participation opportunities, and greater fear of in-school victimization (Voight, Hanson, O’Malley, & & Adekanye, 2015; Baker & Mednick, 1990). Arab American students facing bias-based bullying reported feeling supported by family and friends, but found little support among school administrators or teachers (Albdour, Lewin, Kavanaugh, Hong, & Wilson, 2017). These negative perceptions may have profound effects on student academic and health outcomes.

A positive school environment, defined as greater disciplinary structure, teacher support, and academic expectations, had positive effects in decreasing bullying perpetration and victimization across racial groups (Konold, Cornell, Shukla, & Huang, 2017). Schools that were supportive and had greater teacher diversity saw decreases in race-based bullying (Larochette, Murphy, & Craig, 2010; Wright & Wachs, 2019). Furthermore, respect for differences between students as well as greater exposure to racial and ethnic diversity is associated with decreased reports of bullying (Gage, Prykanowski, & Larson, 2014; Lanza, Eschols, & Graham, 2018).

Interactions with parents.

Although the connection between home environment and bullying involvement is widely studied, in comparison, few studies have also explored how these factors differentially affect racial and ethnic minorities.

Certain family interactions are universally harmful for bullying involvement across racial and ethnic groups. Studies comparing different effects of poor parent communication, high family violence, low parental monitoring, low parental support, and low family satisfaction found little variance across racial and ethnic groups (Hong, Ryou, & Piquero, 2017; Low & Espelage, 2013; Spriggs, Iannotti, Nansel, & Haynie, 2007). Despite the strength of these universal parent-related risk and protective factors, the aforementioned studies and others report subtle differences between groups. For example, mother’s parental monitoring was protective against bullying perpetration and victimization across racial groups, but father’s parental monitoring was protective for White Americans only and not African Americans (Hong, Ryou, & Piquero, 2017). Similarly, negative maternal parenting styles (Brown, Arnold, Dobbs, & Doctoroff, 2007) and living with only one parent (Spriggs, Iannotti, Nansel, & Haynie, 2007) were associated with increased bullying perpetration and relational aggression, respectively, but only for White youth and not for Black and Hispanic youth. At the same time, parental criticism was associated with experiencing indirect peer victimization for Hispanic children, but not for White children (Boel-Studt & Renner, 2014). In another study, the relationship between parental monitoring and physical aggression was significant for African American, but not Hispanic adolescents; however, family cohesion was more strongly negatively linked to physical aggression for Hispanic than for African American youth (Henneberger, Varga, Moudy, & Tolan, 2016). These findings suggest that how children are raised and their relationships with parents might be universal protective or risk factors for bullying involvement across racial and ethnic divides, but certain aspects of family life are moderated by unique sociocultural contexts specific to minority groups.

For immigrants and children of immigrants, the stress of acculturation can contribute to family conflict associated with greater levels of child aggression. A 2006 study investigated familial and cultural correlates of youth aggression among Latino families in the United States. The study found that perceived discrimination and parent-adolescent conflict predicted aggression in Latino adolescents, whereas familism (or positive and cohesive family relationships) and engagement with culture of origin protected against it. Acculturation conflicts were also related to parent-adolescent conflicts (Smokowski & Bacallao, 2006; Smokowski, Rose, & Bacallao, 2009). While negative family and parent relationships are significant risk factors for bullying involvement across racial, ethnic, and cultural groups, cultural discord can make those relationships more challenging.

Child maltreatment.

Physical or sexual abuse may be linked to higher risk for both bullying victimization and perpetration in children and adolescents (Shields & Cicchetti, 2010; Duncan, 1999). Co-occurrence of multiple forms of maltreatment, including physical or sexual abuse and peer victimization, can cause more severe trauma to youth (Finkelhor, Ormrod, Turner, 2007). Research findings show higher rates of child maltreatment among racial and ethnic minorities (Scher, Forde, McQuaid, & Stein, 2004; Hussey, Chang, & Kotch, 2006), but correlations weaken substantively after controlling for socioeconomic status (Hussey et al., 2006).

Individual-level cognition and mental health.

Low and Espelage (2013) found that compared to their White peers, African American boys scored higher on symptom scales measuring hostility and depression and lower on an empathy scale. Hostility was a stronger predictor of nonphysical bullying in White boys than White girls, African American boys, and African American girls, while depressive symptoms predicted nonphysical bullying in African American boys only (Low & Espelage, 2013). They argue that these cognitive differences may have developed due to maladaptive family environments and contribute to racial and ethnic minorities’ greater perpetration of nonphysical bullying and cyberbullying. The interplay between cognitive mediators of minority status in relation to bullying involvement is not well documented. However, research on intimate partner violence suggests that compared to racial or ethnic majority youth, minority youth exposed to IPV may develop more internalizing behavior (Graham-Bermann & Hughes, 2003; Hazen, Connelley, Kelleher, Barth, & Landsverk 2006) or externalizing behavior (Ehrensaft, Cohen, Brown, Smailes, Chen, & Johnson, 2003; Morrel, Dubowitz, Kerr, & Black, 2003; Voisin & Hong, 2012). In turn, internalizing behavior is related to bullying victimization and externalizing behavior to bullying perpetration; bully-victims tend to display both internalizing and externalizing problems (Cook, Williams, Guerra, Kim, & Sade, 2010). These studies imply that adversity, through its impact on, cognition may affect bullying in minority youth.

Acculturation stress and coping.

Youth struggling with acculturation, culture difference (i.e. difficulty with language, different values, etc.), stigma and prejudice, or social exclusion due to racial or ethnic group membership may be at higher risk of bullying involvement. Problems associated with racial or ethnic minority group membership and immigrant status may be in themselves the core reason for conflict with peers. For example, in the United States, Hispanic children who experienced greater acculturation stress were more likely to be bullied, and bullying victimization was a significant mediator between acculturation stress and depression (Forster et al., 2013). For German and Russian immigrant youth in Israel, the greater risk for being a bullying victim was particularly pronounced within the first 3–5 years of residence in Israel, with risk evening out to be similar to that of native-born youth after this critical time period (Jugert & Titzmann, 2017). A 2010 study compared universal vs. migration-specific factors predicting physical aggression and emotional problems in children of immigrants from Hong Kong, mainland China, and the Philippines in Canada. Universal factors such as parental depression and family dysfunction were related to both physical aggression and emotional problems, but migration-specific factors such as acculturation stress and perceived prejudice were also predictive of physical aggression (Beiser et al., 2010).

In addition to increasing risk for bullying victimization, stressors uniquely relating to minority or immigrant status are related to bullying perpetration. Messinger, Nieri, Tanya, Villar, and Luengo (2012) found that acculturation stress increases odds of being a bully-victim (but not a pure bully or pure victim) among immigrant children in Spain. Similarly, a 2019 study found that the more immigrant youth in Sweden experienced harassment due to their ethnic identity, the greater their engagement in violent behaviors over time. This association was significantly moderated by ethnic identity, such that ethnic harassment predicted engagement in violent behaviors only when youth had high levels of separated identity, or high acculturation (Bayram Özdemir, Özdemir, & Stattin 2019). Aggression and externalizing behavior may be maladaptive responses to acculturative stress, and are common responses to experiencing victimization (Reijntjes et al., 2011). Experiencing victimization because of something one cannot change may be a particularly painful experience that begets greater psychological dysfunction and externalizing behavior.

Furthermore, bullying and aggression are often proactive means to achieve social goals, including status, acceptance, and belonging, which could be more difficult for racial and ethnic minorities and immigrant youth. Indeed, extensive research has shown that bullying is a social process tied to a need to belong and can be a social bonding agent (Salmivalli, Lagerspetz, Björkqvist, Österman, & Kaukiainen, 1996; Underwood & Ehrenreich, 2014; Hoover & Milner, 1998). Bullying is largely a peer-group behavior, especially for pure bullies, as bullies require an audience to give them what motivates them to bully others in the first place: status, acceptance, and belonging (Salmivalli, 2010). Students who reported more bullying perpetration behaviors also reported feeling less left out (Barboza et al., 2009). In a sample of majority Latino and Asian students in California, having friends who participate in aggressive behavior predicted bullying perpetration among both pure bullies and bully-victims. Friendship with aggressive peers was negatively associated with being a victim (Mouttapa, Valente, Gallaher, Rohrbach, & Unger, 2004). Among immigrant students (but not among non-immigrants) in Norway and Austria, the need for peer acceptance and affiliation significantly predicted bullying perpetration and aggression (Strohmeier, Fandrem, & Spiel, 2012), and this effect was stronger for first generation immigrants than for second generation and native-born students (Strohmeier, Fandrem, Stefanek, & Spiel, 2012). Though this has not been explicitly examined in any study to our knowledge, youth who may feel like an outsider or excluded due to their race, ethnicity, or immigration background might bully others to create social bonds with peers. Further, bullying and aggressive behavior may be initiated to deal with stigma, prejudice, and bullying that minority youth might face due to their social identities. For example, the African American lesbian gang, Dykes Take Over, has responded to homophobic bullying by sexually harassing same-sex heterosexual peers and re-establishing a power-dynamic using lesbian/bisexual threat (Johnson, 2008). Similarly, immigrants from the former Soviet Union in Israel formed organized, hierarchical gangs in which they bullied others, possibly due to an absence of reliable parental figures or to regain control in an unfamiliar environment (Tartakovsky & Mirsky, 2001). Youth may turn to perpetrating bullying in a maladaptive way of coping with pressures and stressors unique to their marginalized identities and social contexts. Future research should examine nuanced relationships between known bullying involvement risk and protective factors and race and ethnicity as moderators.

Ethnic identity.

Ethnic identity may protect against bullying involvement. Interestingly, self-esteem may be personal in nature as well as associated specifically with ethnic identity. In a sample of Turkish children living in the Netherlands, personal self-esteem predicted peer victimization based on personal traits but not ethnic victimization, whereas ethnic self-esteem predicted ethnic victimization but not personal victimization (Verkuyten & Thijs, 2001). Research has found that strong ethnic identity is negatively correlated with loneliness and depression (Roberts et al., 1999), as well as aggression (Arbona, Jackson, McCoy, & Blakely, 1999; Jagers & Mock, 1993; Smokowski et al., 2017). A study of African-American youth found that ethnic identity and global self-worth, in combination, predicted better coping strategies, fewer endorsements of aggression, and less aggressive behavior (McMahon & Watts, 2002). Among Naskapi youths from Kawawachikamach, Québec, greater identity with Native culture predicted less perceived aggression from peers (Flanagan, 2011). Immigrants and children of immigrants from the former Soviet Union in Israel were less likely to be aggressive against peers if they had high ethnic identity, and ethnic identity also predicted less future aggression (Benish-Weisman, 2016). Thus, racial and ethnic minority status may be associated with protective factors, as well, providing a sense of belonging and prosocial bonds with family and peers, which reduce risk for bullying involvement (Ttofi, Bowes, Farrington, & Lösel, 2014).

Differing Bullying Behaviors and Consequences of Bullying Involvement

Differential bullying behaviors among minority and immigrant youth.

Bullying may take different forms (e.g. physical, verbal, relational, cyber, etc.) among different racial and ethnic groups. Racial and ethnic minority students in the United States report being perpetrators of different forms of bullying than majority students, though results vary across studies. For example, Wang, Iannotti, and Luk (2012) found that African American, Hispanic, and “other race” youth are more likely than their White peers to engage in “all types” bullying perpetration. However, while African American youth were also more likely to engage in social and/or verbal-only bullying than their White peers, Hispanic and “other race” youth were less likely to do so. However, an earlier study found somewhat contrary evidence: in a 2009 study, African American students perpetrated physical, verbal, and cyberbullying—but not relational bullying—more often than White Americans. Compared to White students, Hispanic students were more likely to be physical bullies (Wang, Iannotti, & Nansel, 2009). A third study indicated minority youth reported more physical bullying and less cyberbullying than majority youth (Barlett & Wright, 2018). In a longitudinal study in Germany, teens with a migrant background reported higher consumption of violent media at baseline, and more physical but less relational aggression than German peers two years later (Möller, Krahé, & Busching, 2013). In a sample of U.S. high school students in Hawaii, White, Filipino American, and Samoan students (who make up a numerical minority of the student population and who were more recent immigrants compared to native Hawaiians and Japanese Americans) perpetrated social exclusion at higher rates than the former two groups, but there were no significant differences between groups in levels of physical violence perpetration or teasing (Hishinuma et al., 2015). Based on these findings, it is hard to draw concrete conclusions about different forms of bullying behaviors among minority and immigrant youth. Theory should guide future research focused on replicating these studies and clarifying discrepancies.

Differing rates of physical, verbal, and relational bullying may stem from unique sociocultural backgrounds. Minorities who grow up in adverse environments may be more likely to endorse aggressive behavior and engage in more overt rather than relational bullying, due to forming positive beliefs about aggressive behavior in the more adverse environment (Coie & Dodge, 1996; Colder et al., 2000). In addition, value orientation may moderate types of bullying behavior. In individualistic societies, youth tend to enact direct or physical aggression, while in collectivist societies, bullying may be more indirect and less physical (Forbes, Collinsworth, Zhao, Kohlman, & LeClaire, 2011). Furthermore, Western societies may be more willing to endorse and support aggression (Bowker, Rubin, Buskirk-Cohen, Rose-Krasnor, & Booth-LaForce, 2010; Prinstein & Cillessen, 2003; Rodkin et al., 2000), while in collectivist cultures aggression is less accepted (Li, Xie, & Shi, 2012). Some countries or regions may be influenced by both collectivism and individualism, leading to differences in behavior between racial, ethnic, or cultural groups. For example, in Trinidad, Afro-Trinidadians reported perpetrating higher levels of physical, indirect, and verbal aggression compared to Mixed and Indo-Trinidadians, which may be because Trinidadians of African descent had to adjust to Western individualist culture when they were transported to Trinidad and enslaved by White colonists, while Indo-Trinidadians retained a more collectivist culture (Descartes & Maharaj, 2016). These cultural contexts can change how bullying behaviors manifest in different countries, and immigrants may retain values from their countries of origin, even as they acclimate to a new environment.

Differential consequences of bullying involvement.

Some research suggests that racial and ethnic minority and immigrant youth involved in bullying may incur greater health and educational consequences in some respects than majority youth. In a nationally representative sample of Canadian adolescents, harassment at school was associated with greater mental health problems, especially for immigrant (versus non-immigrant) students (Abada, Hou, & Ram, 2008). Similarly, African American and Latino (versus White) students were more likely to drop out of school as a consequence of peer victimization (Peguero, 2011). Latino students who felt little connection to either Latin or U.S. culture were more likely than Latinos who did have cultural connections to perceive high levels of discrimination and have fewer positive experiences. Latino adolescents who reported high discrimination and bullying victimization, as well as fewer positive experiences, experienced greater risk of depressive symptoms and cigarette use (Lorenzo-Blanco, Unger, Oshri, Baezconde-Garbanati, & Soto, 2016).