Abstract

The significance of adding new oral anticoagulants (NOACs) to antiplatelet therapy in patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) is unclear. We conducted a meta-analysis to assess the safety and efficacy of adding NOACs (apixaban, rivaroxaban, and dabigatran) to single antiplatelet agent (SAP) or dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) in patients with ACS. Seven randomized controlled trials were selected using PubMed or MEDLINE, Scopus, and Cochrane library (inception to August 2017). The summary measure was random effects hazard ratio (HR) with 95% confidence interval (CI). The primary safety outcome was clinically significant bleeding. The secondary efficacy outcome was major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE; composite of myocardial infarction, stroke, and all-cause mortality). In 31,574 patients, addition of NOAC to SAP did not increase the risk of clinically significant bleeding (HR 0.82, 95% CI 0.56 to 1.20, p = 0.31); however, the risk of clinically significant bleeding was significantly increased with NOAC plus DAPT (HR 2.24, 95% CI 1.75 to 2.87, p < 0.001). NOACs had no statistically beneficial effect on MACE when used with SAP (HR 0.82, 95% CI 0.66 to 1.04, p = 0.10); however, a modest reduction in MACE was observed when NOACs were combined with DAPT (HR 0.86, 95% CI 0.78 to 0.93, p < 0.001). In conclusion, in patients with ACS, the addition of NOAC to DAPT resulted in increased risk of clinically significant bleeding, whereas only a modest reduction in MACE was achieved. The addition of NOACs to SAP did not result in significant reduction of MACE or increase in clinically significant bleeding.

Despite the adherence to recommended dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) in acute coronary syndrome (ACS), the patients continue to face the risk of recurrent ischemic events.1 The risk of recurrent ischemia is considered highest during the first few months after ACS because of elevated thrombin levels, and approximately 10% patients suffer major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) during this time period.2,3 This has generated interest in optimizing the antithrombotic therapy in addition to the standard antiplatelet therapy. Warfarin both as monotherapy and in combination with antiplatelet therapy has shown to reduce MACE, but at the cost of excessive bleeding.4,5 In the modern practice, the new oral anticoagulants (NOACs) have partially replaced warfarin because of their predictable pharmacodynamics, no laboratory monitoring, minimal drug and dietary interactions, and a wide therapeutic window. These drugs have demonstrated promising results for stroke prophylaxis compared with warfarin in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation along with comparatively improved bleeding outcomes.6–10 However, there is a paucity of data regarding their potential as the antithrombotic therapy after ACS. To fill this knowledge gap, we performed a meta-analysis, focusing on relevant NOACs (rivaroxaban, apixaban, and dabigatran) to investigate the relative safety and efficacy of NOAC when added to single antiplatelet agent (SAP) and DAPT in patients with recent ACS.

Methods

The present meta-analysis is conducted according to Cochrane Collaboration guidelines and reported according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses report.11,12 The following inclusion criteria were set: (1) randomized clinical trials (phase II and III) investigating commonly prescribed NOACs (apixaban, rivaroxaban, and dabigatran) in patients with ACS, (2) included studies had to report outcomes of interest (see below) in adult population (aged ≥18 years), and (3) full-text articles. Two authors (AA and FN) independently conducted the search using PubMed or MEDLINE, Scopus, and Cochrane library (inception to August 2017). Search was restricted to humans and clinical trials. The following search algorithm was used in PubMed: (anti[All Fields] AND (“thrombin”[MeSH Terms] OR “thrombin”[All Fields])) OR ((“factor xa”[MeSH Terms] OR (“factor”[All Fields] AND “xa”[All Fields]) OR “factor xa”[All Fields]) AND inhibitor[All Fields]) OR (“apixaban”[Supplementary Concept] OR “apixaban”[All Fields]) OR (“rivaroxaban”[MeSH Terms] OR “rivaroxaban”[All Fields]) OR (“dabigatran”[MeSH Terms] OR “dabigatran”[All Fields]) OR (“acute coronary syndrome”[MeSH Terms] OR (“acute”[All Fields] AND “coronary”[All Fields] AND “syndrome”[All Fields]) OR “acute coronary syndrome”[All Fields]) OR (“myocardial infarction”[MeSH Terms] OR (“myocardial”[All Fields] AND “infarction”[All Fields]) OR “myocardial infarction”[All Fields]) AND (Clinical Trial[ptyp] AND “loattrfree full text”[sb]). Two authors (AA and FN) screened the search results based on text, title, and abstracts. The drugs that are not used in the current practice (ximelgatran, darexaban, letaxaban, and otamixaban) were excluded. The whole process was supervised by a third author (SUK), and discrepancies were resolved with mutual discussion. The initial search of electronic data base yielded 591 articles. A total of 444 articles were duplicates, 108 had different study designs (nonrandomized studies, systematic reviews, meta-analyses), 23 were abstracts, and 4 trials assessed undesired NOACs (ximelgatran, darexaban, letaxaban, and otamixaban). After diligent exclusion process, 7 articles were included in the final analysis. Figure 1 illustrates the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses-based selection process of included studies.

Figure 1.

PRISMA diagram showing selection process of the studies.

Data extraction was done independently by 2 authors (AA and FN) using a prespecified collection form incorporating baseline characteristics of the participants, inclusion and exclusion criteria of the trials, number of events, sample size, crude point estimates, follow-up duration, and definition of desired outcomes. When available, we preferred adjusted estimates from intention-to-treat cohorts. The data adjudication was done by third-party review (SUK), and any discrepancies were resolved with consensus. The assessment of risk was done at study level, and quality assessment was done by Cochrane bias risk assessment tool (Supplementary Table S1).13 The PIONEER AF (Open-Label, Randomized, Controlled, Multicenter Study Exploring Two Treatment Strategies of Rivaroxaban and a Dose-Adjusted Oral Vitamin K Antagonist Treatment Strategy in Subjects with Atrial Fibrillation who Undergo Percutaneous Coronary Intervention [PCI]) and RE DUAL PCI (Randomized Evaluation of Dual Antithrombotic Therapy with Dabigatran versus Triple Therapy with Warfarin in Patients with Non-valvular Atrial Fibrillation Undergoing PCI) were open-label trials and were affected by performance bias; however, because the blinding of the outcome adjudicators was appropriate, a low risk of detection bias was considered.9,10 Overall, all the studies were prospective randomized controlled trials and had a low risk of selection, attrition, and reporting bias.

The primary safety focus was clinically significant bleeding. The secondary efficacy end point was MACE (composite of myocardial infarction [MI], stroke and all-cause mortality). There was a noticeable heterogeneity in the definition of clinically significant bleeding across the trials. All the trials of apixaban except APPRAISE 2 (Apixaban for prevention of acute ischemic and safety events) and dabigatran mainly defined bleeding events as per the International Society of Thrombosis and Hemostasis (ISTH) definition.14,15 Conversely, the rivaroxaban trials assessed the bleeding according to Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) definitions.16 We preferred ISTH criteria in this review, and TIMI criteria were used only if ISTH criteria were not available. Based on ISTH criteria, the clinically significant bleeding was defined as the composite of major bleeding and clinically relevant minor bleeding, whereas as per TIMI criteria, a clinically significant bleeding was a composite of TIMI major bleeding, minor bleeding, or bleeding requiring medical attention.

Outcomes were combined using generic invariance method, and both fixed and random effects models were generated.17 Heterogeneity was assessed using Q statistics with I2 > 50% being consistent with a high degree of heterogeneity.18 There was significant heterogeneity in the studies (I2 = 78, p < 0.001, Q-value =54.7), so final estimates were reported as random effects hazard ratio (HR) with 95% confidence interval (CI). All tests were performed at a 5% significance level. Subgroup analyses to assess the effects of individual NOACs were also constructed. The risk of publication bias was assessed using funnel plot and Egger’s test, involving all the treatment arms and the primary safety and secondary efficacy outcomes (supplementary Figures S1 and S2).19 Comprehensive meta-analysis software version 3.0 (Biostat, Englewood, NJ) was used for all the analyses.

Results

In the selected trials, APPRAISE, APPRAISE-2, ATLAS ACS-TIMI 46 (Anti-Xa Therapy to Lower cardiovascular events in addition to Aspirin with or without thienopyridine therapy in Subjects with Acute Coronary Syndrome-Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction trial 46), ATLAS ACSTIMI 51, and REDEEM (Dabigatran vs placebo in patients with ACS on DAPT: a randomized, double-blind, phase II trial) investigated the effects of NOACs in patients with recent ACS, whereas both PIONEER AF and RE DUAL PCI primarily assessed the safety of rivaroxaban and dabigatran, respectively, in patients who underwent PCI and had concomitant atrial fibrillation.9,10,15,20–23 Following the similar approach used in previous meta-analysis, we avoided the assessment of dosages that had posed extreme bleeding risk in the literature and, subsequently, were not further evaluated in follow-up trials.24 Based on this criterion, this study enrolled 70% patients from APPRAISE, 99% from APPRAISE 2, 57% from ATLAS ACS-TIMI 46, 98% from ATLAS ACS-TIMI 51, 99% from REDEEM, and 100% from PIONEER AF. The RE DUAL PCI enrolled only 50% patients with ACS, and the rest of the participants had elective PCI for non-ACS. The RE DUAL PCI was excluded from secondary efficacy outcome as the study defined MACE differently (composite of MI, stroke, and thromboembolism). Aspirin was used by 94% patients, 41% used clopidogrel, 1.2% used ticagrelor, and 0.3% patients were on prasugrel. The characteristics of the trials are summarized in Table 1. Figures 2 and 3 represent forest plots for clinically significant bleeding and MACE, respectively. Table 2 shows subgroup analysis based on individual NOACs.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the studies

| Study | Arms | Sample Size | Single/dual antiplatelet therapy | Age (years) | Male | Prior Myocardial infarction | Diabetes | Percutaneous Coronary Intervention |

Follow up duration (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| APPRAISE20 | Apixaban/Placebo | 1210 | 24/76 (%) | 60 | 78 (%) | 5.5 (%) | 22.6 (%) | 66.4 (%) | 6 |

| APPRAISE 215 | Apixaban/Placebo | 7315 | 19/81 (%) | 67 | 78 (%) | 26.2 (%) | 47.8 (%) | 44.6 (%) | 8 |

| ATLAS ACS TIMI 4621 | Rivaroxaban/Placebo | 1997 | 25/75 (%) | 57 | 77 (%) | 21.2 (%) | 19.1 (%) | 63.7 (%) | 6 |

| ATLAS ACS TIMI 5122 | Rivaroxaban/Placebo | 15342 | 7/93 (%) | 62 | 75 (%) | 26.9 (%) | 31.9 (%) | 60.4 (%) | 13 |

| PIONEER AF9 | Rivaroxaban/Warfarin | 2124 | 50/50 (%) | 70 | 74 (%) | NR | NR | 100 (%) | 12 |

| REDEEEM23 | Dabigatran/Placebo | 1861 | 2/98 (%) | 62 | 76 (%) | 28.9 (%) | 31.2 (%) | 54.5 (%) | 6 |

| RE DUAL PCI10 | Dabigatran/Warfarin | 1743 | 100/0 (%) | 70 | 76 (%) | 26.1 (%) | 37.1 (%) | 100 (%) | 14 |

NR = not reported.

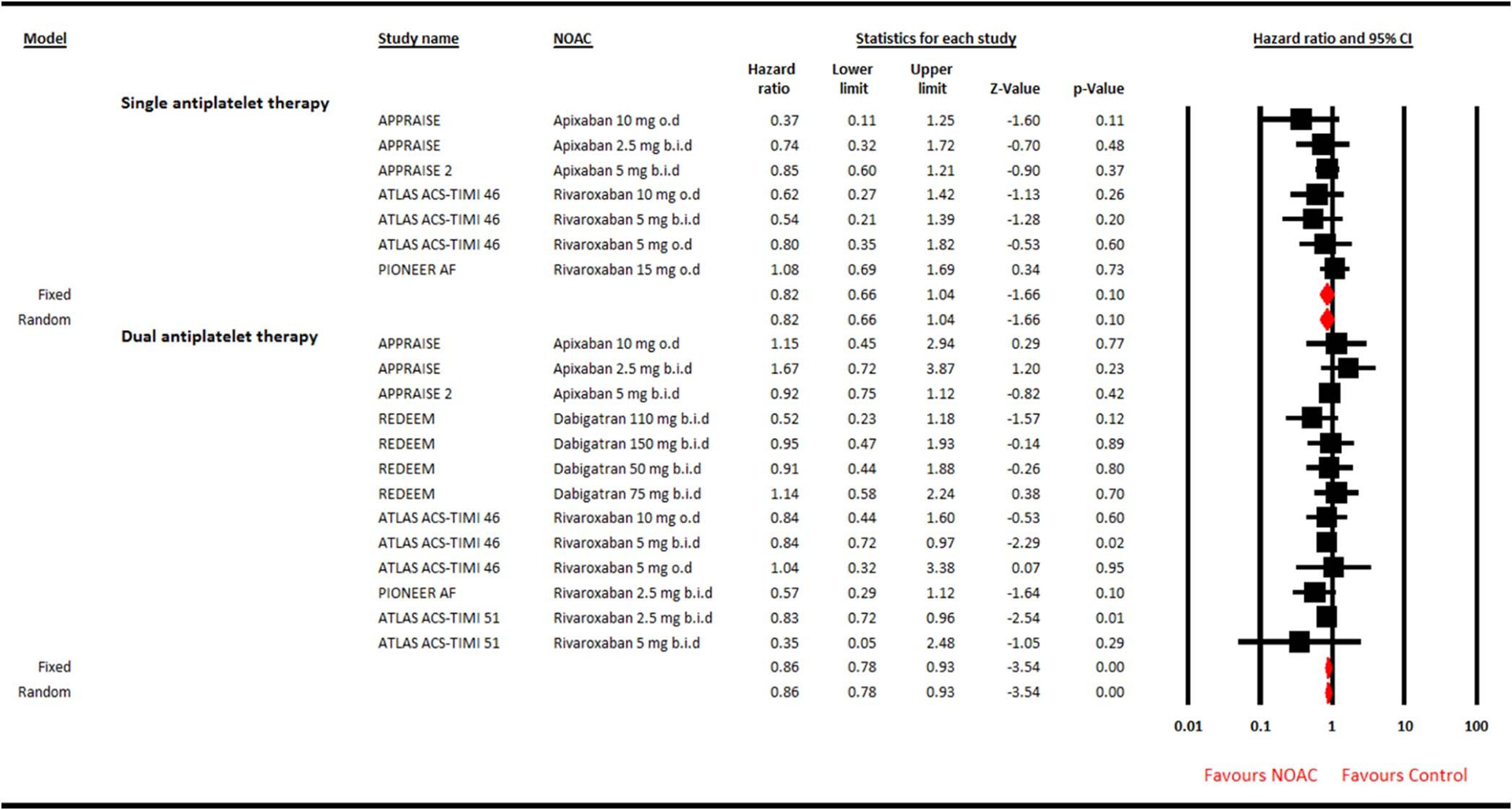

Figure 2.

Forest plot showing effect of adding new oral anticoagulant agent to single versus dual antiplatelet therapy on clinically significant bleeding events. Summary estimate is hazard ratio (HR) with 95% confidence interval (CI).

Figure 3.

Forest plot showing effect of adding new oral anticoagulant agent to single versus dual antiplatelet therapy on major adverse cardiovascular events. Summary estimate is hazard ratio (HR) with 95% confidence interval (CI).

Table 2.

Subgroup analysis based on individual new oral anticoagulants

| Clinically significant bleeding | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single antiplatelet therapy | Dual antiplatelet therapy | |||

| Drugs | HR (95 % CI) | P-value | HR (95 % CI) | P-value |

| Apixaban | 1.81 (0.66–4.93) | 0.25 | 2.56 (1.92–3.43) | <0.001 |

| Rivaroxaban | 1.35 (0.42–4.37) | 0.62 | 1.95 (1.36–2.79) | <0.001 |

| Dabigatran | 0.51 (0.42–0.61) | <0.001 | 2.94 (1.91–4.54) | <0.001 |

| Major adverse cardiovascular events | ||||

| HR (95 % CI) | P-value | HR (95 % CI) | P-value | |

| Apixaban | 0.79 (0.57–1.08) | 0.14 | 0.96(0.79–1.16) | 0.66 |

| Rivaroxaban | 0.86 (0.62–1.20) | 0.77 | 0.83 (0.75–0.91) | <0.001 |

| Dabigatran | – | – | 0.88 (0.61–1.26) | 0.49 |

HR = hazard ratio; 95% CI = confidence interval.

In 31,574 patients, addition of NOAC to SAP did not increase the risk of clinically significant bleeding (HR 0.82, 95% CI 0.56 to 1.20, p = 0.31) and also lacked the beneficial effect on MACE (HR 0.82, 95% CI 0.66 to 1.04, p = 0.10). Conversely, a modest reduction in MACE was achieved when NOAC was combined with DAPT (HR 0.86, 95% CI 0.78 to 0.93, p < 0.001); however, this strategy more than doubled the risk of bleeding (HR 2.24, 95% CI 1.75 to 2.87, p < 0.001). Egger test did not highlight publication bias for clinically significant bleeding (2-tailed p = 0.75) or MACE (2-tailed p = 0.50). In the subgroup analyses, dabigatran plus SAP was a safer approach compared with control (HR 0.51, 95% CI 0.42 to 0.61, p < 0.001), and only rivaroxaban plus DAPT showed significant 17% reduction in MACE. All the individual NOACs increased the bleeding risk significantly when added to DAPT without achieving meaningful MACE benefit.

Discussion

The cardiologists should continue to engage in efforts to encounter the risk of recurrent ischemia in patients with ACS. The professional guidelines are clear about the parenteral anticoagulants during the acute care of ACS; however, their role is not clearly defined after hospital discharge. In the recent times, there is an ongoing effort to assess the effects of NOACs in this regard. We have combined all the phase II and III clinical trials of commonly used NOACs, which have investigated their role in patients with ACS. This meta-analysis comprising 31,574 recent patients with ACS reports that the addition of NOAC to SAP did not result in significant reduction in MACE, whereas the NOAC plus DAPT reduced the risk of MACE by 14% only. NOAC plus SAP was a safer approach with regard to clinically significant bleeding, whereas addition of NOAC to DAPT significantly increased the bleeding risk. These findings are novel and have not been demonstrated in previous meta-analysis.

A previous meta-analysis based on similar approach has assessed the effects of NOACs in management after ACS; however, this study was confounded by major limitations.24 First, this former meta-analysis included drugs that are no longer therapeutic options. Ximelgatran was withdrawn from the market because of hepatotoxicity, and the manufacturing of darexaban was discontinued owing to disappointing results shown in RUBY 1 (a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of the safety and tolerability of the novel oral factor Xa inhibitor darexaban [YM150] following ACS) trial.25,26 Second, this study was published before the contemporary PIONEER AF and RE DUAL PCI trials and, thus lacked these data sets.9,10 Our report has attempted to address these limitations by providing a more current and comprehensive meta-analysis on this issue.

The use of oral anticoagulant agent with SAP has emerged as a new therapeutic approach. This strategy was first endorsed in What is the Optimal Antiplatelet & Anticoagulant Therapy in Patients with Oral Anticoagulation and Coronary Stenting trial, which proved clopidogrel, as compared with DAPT, to be safer and equally effective in patients with ACS already taking warfarin.27 This approach was extrapolated to the NOACs in PIONEER AF and RE DUAL PCI, and has shown impressive safety outcomes.9,10 The main concern regarding this strategy is its predominant focus on safety outcomes and its tendency to possibly compromise the efficacy. In the previous meta-analysis, when NOAC was added to SAP, there was a 30% risk reduction in MACE but at the cost of 79% increase in clinically significant bleeding. On the other hand, the combination of NOAC plus DAPT yielded a mere 13% risk reduction in MACE, and more than doubled the bleeding risk (HR 2.34, 95% CI 2.06 to 2.66).24 Our review refutes the efficacy superiority when NOACs are added to SAP. This lack of congruence can be explained by certain reasons. Wallentin et al included the Oral ximelagatran for secondary prophylaxis after myocardial infarction trial, which showed 24% risk reduction in MACE with ximelgatran plus aspirin, without causing significant bleeding events, which had likely directed the effects in the favor of NOAC plus SAP.25 Furthermore, the new data regarding rivaroxaban and dabigatran endorse for a better safety profile of NOACs plus SAP without showing additional efficacy advantage, which was missing from previous meta-analysis.9,10

The European Society of Cardiology lists rivaroxaban (2.5 mg b.i.d.) as an option for NSTEMI in addition to aspirin and clopidogrel only in patients with high ischemic burden and low bleeding risk (class II b).28 These recommendations stem from the outcomes of the ATLAS ACS TIMI 51 trial. In the ATLASACS TIMI 51 trial, at a mean duration of 13 months, compared with placebo, rivaroxaban 2.5 mg reduced the risk of the primary efficacy end point (cardiovascular death, MI, or stroke) by 16% (HR 0.84, 95% CI 0.72 to 0.97, p = 0.02) and 15% with rivaroxaban 5 mg (HR 0.85, 95% CI 0.73 to 0.98, p = 0.03). The risk of TIMI non-coronary artery bypass graft major bleeds occurred in 1.8% with 2.5 mg and 2.4% with 5 mg rivaroxaban, compared with 0.6% with placebo (p = 0.001).22 Based on these results, the European Medicinal Agency approved the use of rivaroxaban in ACS; on the other hand, the US Food and Drug Administration declined the approval of rivaroxaban for ACS in May 2012, citing higher rates of incomplete follow-up (12%), uncounted death, and concerns regarding informative censoring noticed in this trial. Our report supports the MACE benefit with rivaroxaban, but at the expense of significant bleeding risk. These findings are consistent with previous randomized studies and the recent Cardiovascular Outcomes for People Using Anticoagulation Strategies trial, which provides further evidence that use of rivaroxaban plus aspirin can reduce the risk of thrombotic events, even in patients with stable coronary artery disease, but at the cost of increased bleeding risk.21,22,29

This meta-analysis has certain shortcomings. First, because the event rates were exceedingly low for the individual outcomes, therefore, we could not assess the important individual clinical end points such as stent thrombosis or risk of cardiovascular mortality. Second, there was a substantial heterogeneity in the definition of bleeding outcome, a common limitation cited in previous meta-analysis as well as owing to variations in bleeding definition across all the trials. Third, the included trials have assessed the drugs with highly variable dosing, and because of a limited number of available studies, a subgroup analysis based on drug dosages was not feasible. Similarly, because of limited data, a subgroup analysis of ACS presentations, that is, STEMI, NSTEMI, and unstable angina, was not possible. Fourth, as the presentation of ticagrelor and prasugrel is extremely low, this review mainly generates the evidence for aspirin and clopidogrel as the background therapy. Finally, the majority of these studies were not powered to assess MACE, thus, efficacy outcomes should be interpreted cautiously.

In conclusion, in patients with recent ACS, the addition of NOAC to SAP does not result in excessive bleeding events or reduction in MACE. The addition of NOAC to DAPT resulted in a modest MACE reduction but led to excessive bleeding risk. In NOACs, only rivaroxaban plus DAPT was found to reduce the risk of MACE, whereas dabigatran plus SAP was the safest approach. This review focuses on patients who are taking aspirin and clopidogrel as background antiplatelet therapy. Whether the addition of NOAC to ticagrelor or prasugrel would maximize the cardiovascular benefits, and what would be the bleeding tendency with these agents, this notion requires further exploration. Until the fog clears from this active investigative domain of antithrombotic therapy, the practitioner should carefully weigh the thrombotic and bleeding risk before suggesting an antithrombotic regimen to the individual patient. This discussion should include dosing and duration of the drugs and the required monitoring of the possible adverse events.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Disclosures

Dr. Kaluski is a speaker and consultant for Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pfizer, Janssen, and Daiichi-Saknyo. The authors have not received any funding for this project.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2017.10.035.

References

- 1.Paravattil B, Elewa H. Strategies to optimize dual antiplatelet therapy after coronary artery stenting in acute coronary syndrome. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther 2017;22:347–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Libby P Mechanisms of acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med 2013;369:883–884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Monroe DM, Hoffman M, Roberts HR. Platelets and thrombin generation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2002;22:1381–1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hurlen M, Abdelnoor M, Smith P, Erikssen J, Arnesen H. Warfarin, aspirin, or both after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 2002;347:969–974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Es RF, Jonker JJ, Verheugt FW, Deckers JW, Grobbee DE. Aspirin and coumadin after acute coronary syndromes (the ASPECT-2 study): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2002;360:109–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Connolly SJ, Ezekowitz MD, Yusuf S, Eikelboom J, Oldgren J, Parekh A, Pogue J, Reilly PA, Themeles E, Varrone J, Wang S, Alings M, Xavier D, Zhu J, Diaz R, Lewis BS, Darius H, Diener HC, Joyner CD, Wallentin L. Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2009;361:1139–1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patel MR, Mahaffey KW, Garg J, Pan G, Singer DE, Hacke W, Breithardt G, Halperin JL, Hankey GJ, Piccini JP, Becker RC, Nessel CC, Paolini JF, Berkowitz SD, Fox KA, Califf RM. Rivaroxaban versus warfarin in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2011;365:883–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Granger CB, Alexander JH, McMurray JJ, Lopes RD, Hylek EM, Hanna M, Al-Khalidi HR, Ansell J, Atar D, Avezum A, Bahit MC, Diaz R, Easton JD, Ezekowitz JA, Flaker G, Garcia D, Geraldes M, Gersh BJ, Golitsyn S, Goto S, Hermosillo AG, Hohnloser SH, Horowitz J, Mohan P, Jansky P, Lewis BS, Lopez-Sendon JL, Pais P, Parkhomenko A, Verheugt FW, Zhu J, Wallentin L. Apixaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2011;365:981–992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gibson CM, Mehran R, Bode C, Halperin J, Verheugt FW, Wildgoose P, Birmingham M, Ianus J, Burton P, van Eickels M, Korjian S, Daaboul Y, Lip GY, Cohen M, Husted S, Peterson ED, Fox KA. Prevention of bleeding in patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing PCI. N Engl J Med 2016;375:2423–2434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cannon CP, Bhatt DL, Oldgren J, Lip GYH, Ellis SG, Kimura T, Maeng M, Merkely B, Zeymer U, Gropper S, Nordaby M, Kleine E, Harper R, Manassie J, Januzzi JL, Ten Berg JM, Steg PG, Hohnloser SH. Dual antithrombotic therapy with dabigatran after PCI in atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2017;377:1513–1524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Tulder M, Furlan A, Bombardier C, Bouter L. Updated method guidelines for systematic reviews in the Cochrane Collaboration back review group. Spine 2003;28:1290–1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA Statement. BMJ 2009;339. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Jüni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, Savović J, Schulz KF, Weeks L, Sterne JAC. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2011;343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schulman S, Kearon C. Definition of major bleeding in clinical investigations of antihemostatic medicinal products in non-surgical patients. J Thromb Haemost 2005;3:692–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alexander JH, Lopes RD, James S, Kilaru R, He Y, Mohan P, Bhatt DL, Goodman S, Verheugt FW, Flather M, Huber K, Liaw D, Husted SE, Lopez-Sendon J, De Caterina R, Jansky P, Darius H, Vinereanu D, Cornel JH, Cools F, Atar D, Leiva-Pons JL, Keltai M, Ogawa H, Pais P, Parkhomenko A, Ruzyllo W, Diaz R, White H, Ruda M, Geraldes M, Lawrence J, Harrington RA, Wallentin L. Apixaban with antiplatelet therapy after acute coronary syndrome. N Engl J Med 2011;365:699–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mehran R, Rao SV, Bhatt DL, Gibson CM, Caixeta A, Eikelboom J, Kaul S, Wiviott SD, Menon V, Nikolsky E, Serebruany V, Valgimigli M, Vranckx P, Taggart D, Sabik JF, Cutlip DE, Krucoff MW, Ohman EM, Steg PG, White H. Standardized bleeding definitions for cardiovascular clinical trials: a consensus report from the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium. Circulation 2011;123:2736–2747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.DerSimonian R, Kacker R. Random-effects model for meta-analysis of clinical trials: an update. Contemp Clin Trials 2007;28:105–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. Br Med J 2003;327:557–560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997;315:629–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alexander JH, Becker RC, Bhatt DL, Cools F, Crea F, Dellborg M, Fox KA, Goodman SG, Harrington RA, Huber K, Husted S, Lewis BS, Lopez-Sendon J, Mohan P, Montalescot G, Ruda M, Ruzyllo W, Verheugt F, Wallentin L. Apixaban, an oral, direct, selective factor Xa inhibitor, in combination with antiplatelet therapy after acute coronary syndrome: results of the Apixaban for Prevention of Acute Ischemic and Safety Events (APPRAISE) trial. Circulation 2009;119:2877–2885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mega JL, Braunwald E, Mohanavelu S, Burton P, Poulter R, Misselwitz F, Hricak V, Barnathan ES, Bordes P, Witkowski A, Markov V, Oppenheimer L, Gibson CM. Rivaroxaban versus placebo in patients with acute coronary syndromes (ATLAS ACS-TIMI 46): a randomised, double-blind, phase II trial. Lancet 2009;374:29–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mega JL, Braunwald E, Wiviott SD, Bassand JP, Bhatt DL, Bode C, Burton P, Cohen M, Cook-Bruns N, Fox KA, Goto S, Murphy SA, Plotnikov AN, Schneider D, Sun X, Verheugt FW, Gibson CM. Rivaroxaban in patients with a recent acute coronary syndrome. N Engl J Med 2012;366:9–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oldgren J, Budaj A, Granger CB, Khder Y, Roberts J, Siegbahn A, Tijssen JG, Van de Werf F, Wallentin L. Dabigatran vs. placebo in patients with acute coronary syndromes on dual antiplatelet therapy: a randomized, double-blind, phase II trial. Eur Heart J 2011;32:2781–2789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oldgren J, Wallentin L, Alexander JH, James S, Jonelid B, Steg G, Sundstrom J. New oral anticoagulants in addition to single or dual antiplatelet therapy after an acute coronary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Heart J 2013;34:1670–1680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wallentin L, Wilcox RG, Weaver WD, Emanuelsson H, Goodvin A, Nystrom P, Bylock A. Oral ximelagatran for secondary prophylaxis after myocardial infarction: the ESTEEM randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2003;362:789–797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Steg PG, Mehta SR, Jukema JW, Lip GY, Gibson CM, Kovar F, Kala P, Garcia-Hernandez A, Renfurm RW, Granger CB. RUBY-1: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of the safety and tolerability of the novel oral factor Xa inhibitor darexaban (YM150) following acute coronary syndrome. Eur Heart J 2011;32:2541–2554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dewilde WJ, Oirbans T, Verheugt FW, Kelder JC, De Smet BJ, Herrman JP, Adriaenssens T, Vrolix M, Heestermans AA, Vis MM, Tijsen JG, van’t Hof AW, ten Berg JM. Use of clopidogrel with or without aspirin in patients taking oral anticoagulant therapy and undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: an open-label, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet 2013;381:1107–1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roffi M, Patrono C, Collet JP, Mueller C, Valgimigli M, Andreotti F, Bax JJ, Borger MA, Brotons C, Chew DP, Gencer B, Hasenfuss G, Kjeldsen K, Lancellotti P, Landmesser U, Mehilli J, Mukherjee D, Storey RF, Windecker S, Baumgartner H, Gaemperli O, Achenbach S, Agewall S, Badimon L, Baigent C, Bueno H, Bugiardini R, Carerj S, Casselman F, Cuisset T, Erol C, Fitzsimons D, Halle M, Hamm C, Hildick-Smith D, Huber K, Iliodromitis E, James S, Lewis BS, Lip GY, Piepoli MF, Richter D, Rosemann T, Sechtem U, Steg PG, Vrints C, Luis Zamorano J. 2015 ESC guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation: Task Force for the Management of Acute Coronary Syndromes in Patients Presenting without Persistent ST-Segment Elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2016;37:267–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eikelboom JW, Connolly SJ, Bosch J, Dagenais GR, Hart RG, Shestakovska O, Diaz R, Alings M, Lonn EM, Anand SS, Widimsky P, Hori M, Avezum A, Piegas LS, Branch KRH, Probstfield J, Bhatt DL, Zhu J, Liang Y, Maggioni AP, Lopez-Jaramillo P, O’Donnell M, Kakkar AK, Fox KAA, Parkhomenko AN, Ertl G, Störk S, Keltai M, Ryden L, Pogosova N, Dans AL, Lanas F, Commerford PJ, Torp-Pedersen C, Guzik TJ, Verhamme PB, Vinereanu D, Kim J-H, Tonkin AM, Lewis BS, Felix C, Yusoff K, Steg PG, Metsarinne KP, Cook Bruns N, Misselwitz F, Chen E, Leong D, Yusuf S. Rivaroxaban with or without aspirin in stable cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med 2017;377:1319–1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.