Abstract

Fluorescent small molecules are powerful tools for visualizing biological events, embodying an essential facet of chemical biology. Since the discovery of the first organic fluorophore, quinine, in 1845, both synthetic and theoretical efforts have endeavored to “modulate” fluorescent compounds. An advantage of synthetic dyes is the ability to employ modern organic chemistry strategies to tailor chemical structures and thereby rationally tune photophysical properties and functionality of the fluorophore. This review explores general factors affecting fluorophore excitation and emission spectra, molar absorption, Stokes shift, and quantum efficiency; and provides guidelines for chemist to create novel probes. Structure-property relationships concerning the substituents are discussed in detail with examples for several dye families. Then, we present a survey of functional probes based on PeT, FRET, and environmental or photo-sensitivity, focusing on representative recent work in each category. We believe that a full understanding of dyes with diverse chemical moieties enables the rational design of probes for the precise interrogation of biochemical and biological phenomena.

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Chemical biology is a rapidly-growing field that utilizes chemical strategies to decipher and manipulate natural biology with high precision.1–4 Interdisciplinary research at the chemistry/biology interface has generated revolutionary technologies to probe biological systems, innovated diagnostic platforms to improve human health, and allowed synthetic biology to benefit both medical and environmental needs. These advances often rely on fluorescence-based imaging techniques that can detect, visualize, and characterize morphological and dynamic phenomena of biology at the molecular level in multi-dimensional fashions.3, 4 Therefore, fluorescent probes have become indispensable tools for the field of molecular biology and medicine.4 Owing to their high sensitivity and rapid response, fluorescent probes offer diverse benefits in visualizing spatiotemporal changes in biological systems.3, 5 Though there are many fluorescent probes, including genetically engineered fluorescent proteins6 and quantum dots,7 this review is focused on synthetic fluorescent small molecules. Small molecule fluorophores present a highly attractive space for organic chemists as they hold several key advantages over other imaging systems, such as small size, ease of use, and chemical tunability.1, 8

Left: E. James Petersson was born in Connecticut, USA and completed his undergraduate education at Dartmouth College and his graduate study under Dennis Dougherty at the California Institute of Technology. After receiving his Ph.D. in 2005, he was an NIH Postdoctoral Fellow at Yale University with Alanna Schepartz. He joined the Department of Chemistry at the University of Pennsylvania in 2008 and the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biophysics in the Perelman School of Medicine in 2018. His research has been recognized by several awards, including the Searle Scholar, an NSF CAREER award, and a Sloan Fellowship.

Center: Joomyung (Vicky) Jun was born in South Korea and received her B.Sc. degree in chemical biology at U. C. Berkeley in 2012, performing undergraduate research with Kenneth Raymond. She then worked with Ronald Zuckermann at the Molecular Foundry in Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory until 2014. Her research (Ph.D. 2019) at University of Pennsylvania focused on the development of novel and underexplored fluorogenic small molecules. She was co-advised by Professors Chenoweth and Petersson. She is currently a postdoctoral scholar with Ronald T. Raines in the Department of Chemistry at Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Right: David M. Chenoweth was born in Indiana, USA and received his B.S. degree from Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis (IUPUI) in 1999. He worked at Dow AgroSciences and Eli Lilly before joining Peter Dervan’s group at the California Institute of Technology to pursue a Ph.D. After graduation in 2009, he was an NIH Postdoctoral Fellow with Timothy Swager at Massachusetts Institute of Technology. David was appointed Assistant Professor in the Department of Chemistry at the University of Pennsylvania in 2011 and was promoted to Associate Professor with tenure in 2017. He is also a member of the Biochemistry and Molecular Biophysics Graduate Group in the Perelman School of Medicine and the Bioengineering Graduate Group in the School of Engineering and Applied Science.

2. Brief History and Significance

The first well-defined small molecule fluorescent compound was the antimalarial drug quinine sulfate (ESI, Fig. S1). The fluorescence of quinine was discovered by Fredrick Herschel in 1845 when he noticed the visible emission from an aqueous quinine solution (tonic water).9 Later, in 1852, British scientist Sir George Stokes explained that this phenomenon of emission was due to absorption of light by quinine and coined the term ‘fluorescence.’10 However, fluorescent compounds did not receive much attention until the development of the fluorimeter and fluorescence microscopy in the 1950s.11 Since then, fluorophores have been widely used in bioanalytical techniques to stain tissues and bacteria, spurring many discoveries of other organic dyes. In the early 1990s, Roger Tsien and others developed a series of fluorescent probes by engineering green fluorescent protein (GFP) variants with different colors than wild type GFP as well as superior photophysical properties.6, 12 Tsien, as well as Osamu Shimomura and Martin Chalfie,13 received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2008 for the discovery and development of GFP.14 The extant collection of fluorescent probes has exponentially grown in conjunction with development of imaging instruments. In 2014, the Nobel Prize in Chemistry was awarded to William E. Moerner, Eric Betzig, and Stefan Hell for the development of super-resolution fluorescence microscopy, which overcomes the diffraction limits of conventional light microscopy.15 Today, synthetic fluorogenic probes are found in the vast majority of cell biological experiments, demonstrating diagnostic and even clinical utility.16–18

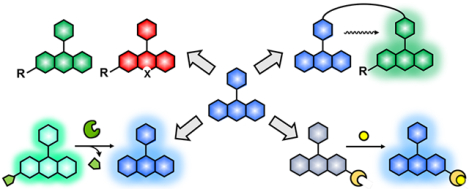

Fluorescent small molecules have utility in a wide variety of experiments, including cellular staining, detection of specific bioanalytes, and tracking biomolecules of interest (Fig. 1). These synthetic fluorophores are generally modified as fluorescent tags that can be appended to the target molecule either by chemical (e.g., biorthogonal click chemistry)19 or biological (e.g., self-labelling protein tag)20–22 means. The target molecules can be as small as inorganic bio-analytes (e.g., calcium, iron, copper), they can be intermediate size molecules like metabolites or lipids, and as big as macromolecules, such as proteins, DNA or RNA. A fluorescent probe commonly consists of a fluorophore, linker, and recognition motif (tag), which can be the site of attachment to the target (ESI, Fig. S2). The small size of synthetic fluorophore probes provides many benefits over fluorescent proteins, including minimal perturbation to the native functions of the target and high flexibility in molecular design and application. Beyond biological imaging, fluorescent materials enable many useful technologies, such as high-throughput screening, genome sequencing, and activity-based protein profiling (ESI, Fig. S3).23

Fig. 1.

General types of fluorescent probe for biological applications. A. Cellular stains with specific localization; B. Environmental indicators that activate fluorescence upon reacting with substrates (e.g., protonation, intracellular metals); C. Indicators for enzymatic activity (e.g., esterase cleaving off ester tag in fluorophore); D. Biorthogonal tags (e.g., azide-alkyne 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition, oxime/hydrazine formation from aldehyde/ketones, tetrazine ligation, and photo-crosslinking).

Successful development of a fluorescent small molecule for biological imaging can be achieved through a combination of the following approaches: 1) efficient synthetic strategies, 2) high throughput in vitro and in silico analytical methods, 3) sufficient imaging instrumentation for in cellulo and in vivo studies, and 4) background knowledge in a biological system.

The first key step is efficient chemical synthesis because all probe properties, including photophysical characteristics of the small molecule, can be tailored by changing chemical structure. In particular, employing advances in chemical synthesis and high-throughput analysis is essential for the discovery of optimized ‘functional’ fluorophores. A functional fluorophore changes fluorescence in response to some external stimuli such as interaction with target biomacromolecules, reactive chemical species, modifying enzymes, light, or environmental changes (Fig. 1).24–27 Such probes empower sophisticated bioassays and real-time imaging of biological systems. With recent revolutionary advances in imaging techniques, these functional fluorophores have been used for multi-color time-resolved imaging and super-resolution microscopy.

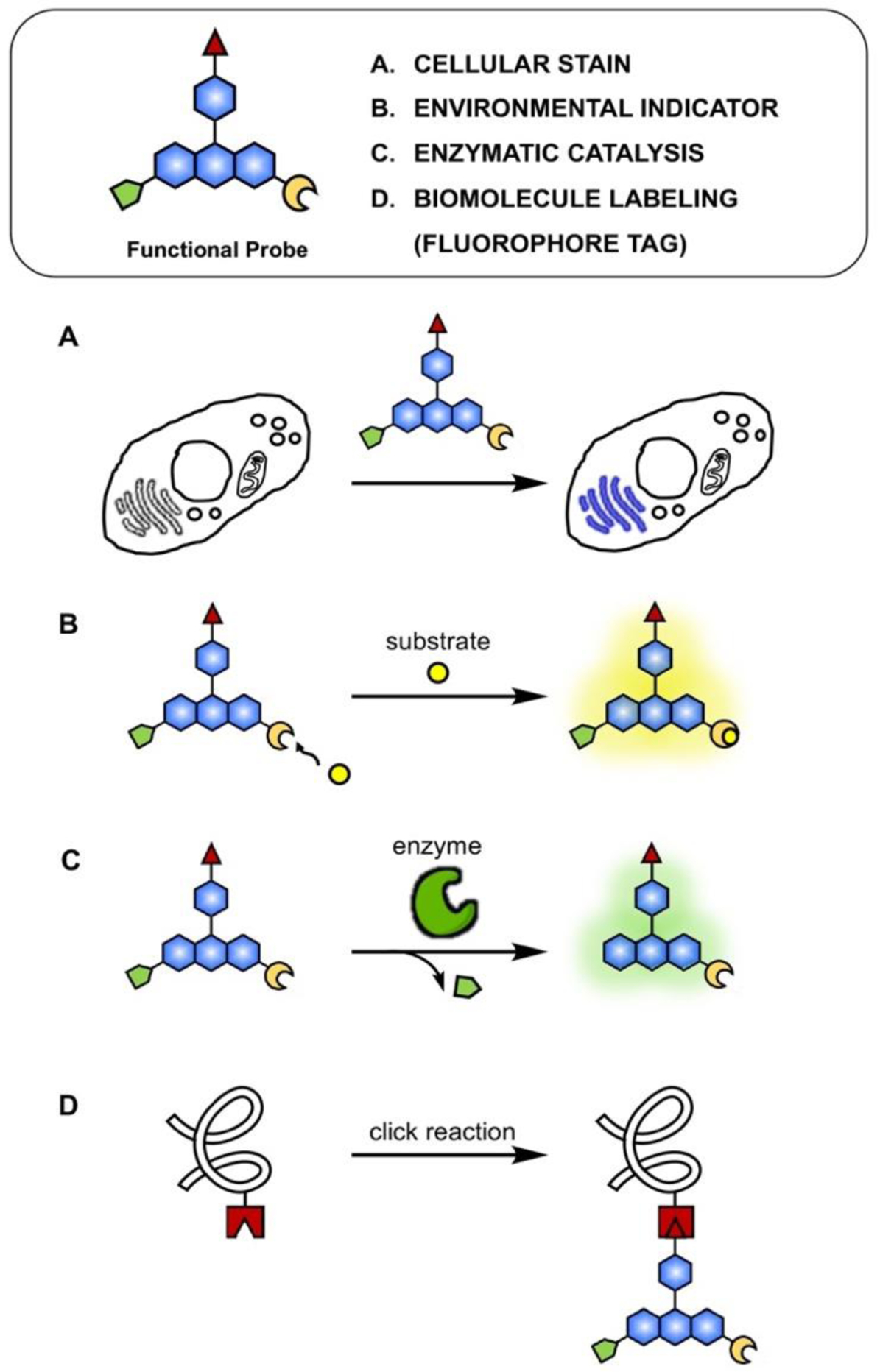

3. Principles of Fluorescence

Over several decades, myriad different fluorophores have been developed with various photophysical and chemical properties. The photophysical characteristics of fluorophores include the absorption maximum (λabs); the emission maximum (λem); the extinction coefficient (ε), typically reported at λabs; and the fluorescence quantum yield (Φ). The process of fluorescence is well described by a Jabłoński diagram (Fig. 2A–B).28, 29 Upon absorption of light at λabs, a molecule initially reaches a singlet excited state (S1, S2, etc.). Typically, an excited molecule will then rapidly lose energy due to solvent reorganization around the distorted dipole of the excited state and relax to the first singlet excited state (S1). From the S1 state, a molecule relaxes back to the ground state (S0) and emits a photon of wavelength λem in a process known as fluorescence emission. The difference between λabs and λem is termed the “Stokes shift” in homage to Sir George Stokes (Fig. 2C). Due to the energy loss stemming from relaxation to S1 and solvent reorganization, λem is generally longer than λabs. However, λabs > λem can occur during multiphoton excitation where two or more photons are simultaneously absorbed to yield the singlet excited state. Alternatively, intersystem crossing (ISC) to and from a triplet state (T1) can occur when the excited electron is no longer paired (parallel/same spin) with the ground state electron. This causes the excited molecule to relax and emit a photon through either radiative (phosphorescence) or nonradiative (quenched) means. Phosphorescent processes usually have significantly longer lifetimes and longer emission wavelengths than fluorescent ones. ISC can be commonly found in heavy-atom containing fluorophores (e.g., those containing iodine or bromine) or fluorophores in the presence of paramagnetic species in solution.

Fig. 2.

Photophysical processes and properties. A. Jabłoński diagram; B. Time scale of each process in order of fastest to slowest28; C. Fluorescence spectra (e.g., coumarin)29 with schematic view of Stokes shift, absorption maximum (λabs) and emission maximum (λem).

The sequence of events leading to fluorescence emission is consistent and thus allows one to analyze fluorescent properties in terms of structural motifs. The fluorescence lifetime (τ) is the average time between excitation and emission and allows the quantification of competing rates of fluorescence and nonradiative processes. This delay also enables fluorescence anisotropy/polarization measurements. The extinction coefficient ε, also known as molar absorptivity, measures the capacity of a dye to absorb photons. The quantum yield Φ measures the efficiency of the fluorescence process based on the ratio of the number of photons emitted to the number of photons absorbed. Taking these values into account, the relative brightness of fluorophores can be determined by multiplying the extinction coefficient and quantum yield (ε x Φ). Another important property is photostability or photobleaching, which demonstrates the robustness of the dye to continued irradiation. Lastly, important chemical characteristics of fluorophores include environmental sensitivities based on the pH or polarity of solvents, aggregation induced properties, solubility, and cell permeability.30

4. Photophysical and Chemical Properties

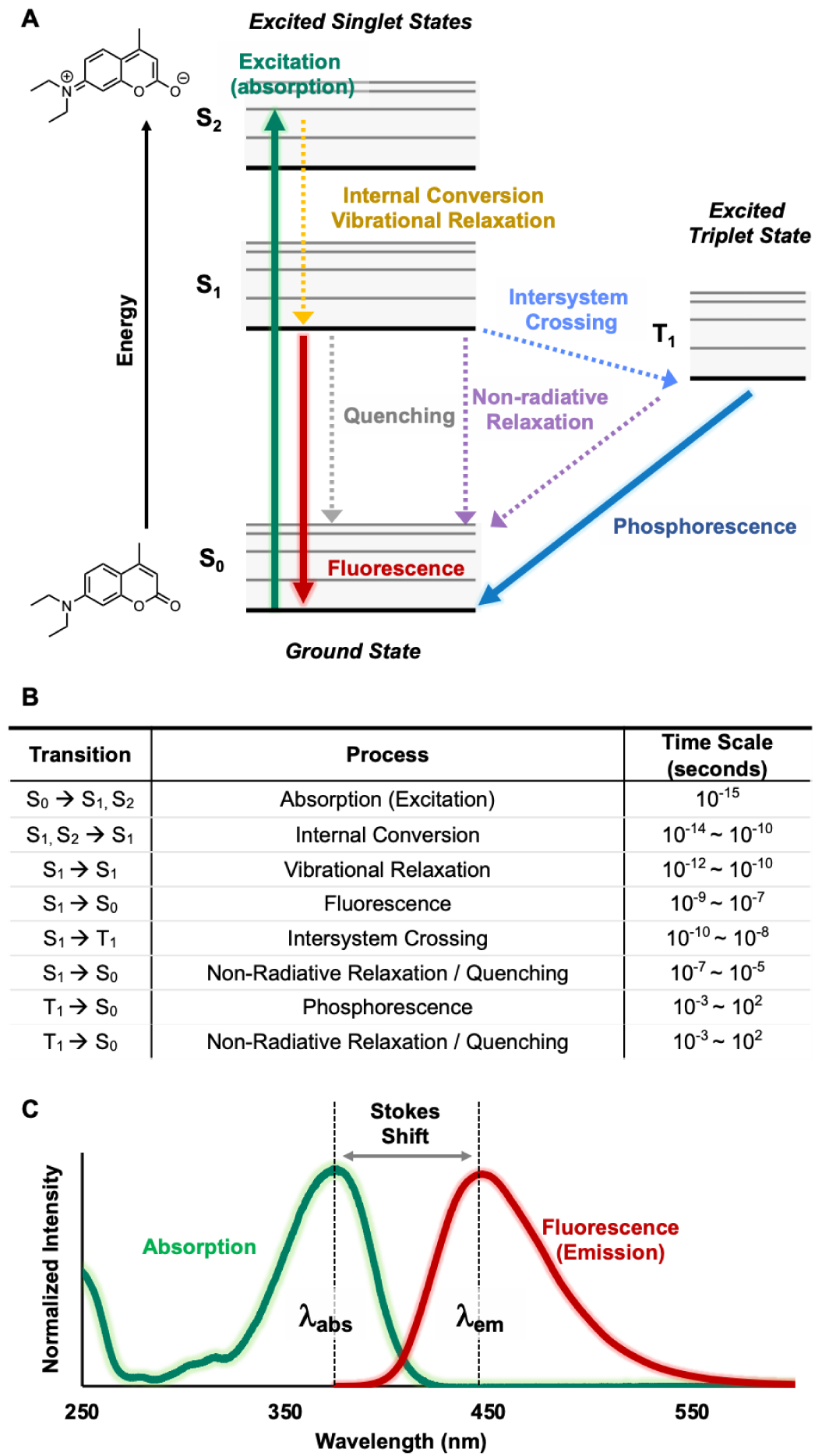

Combining classical strategies for the synthesis of fluorophores with recent advances in synthetic methods has allowed rapid growth in small molecule fluorescent probe development. A plethora of small molecule fluorophores have been synthesized, structurally tailored and applied for specific biological experiments with desired properties. However, the vast number of fluorophores are generated from a modest set of “core” scaffolds as reported in several reviews by Nagano, Raines and Lavis.1, 8, 31, 32 The structures of common fluorogenic cores used in current biological research are shown in Fig. 3. Each scaffold has been derivatized into dyes with improved photophysical and chemical properties. We have analysed the utility and popularity of each fluorogenic core by the number of publications based on the SciFinder database in the ESI (Fig. S4).33 Unsurprisingly, fluorescein was the most ubiquitous core as it was discovered in 1871 and is a Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved dye. Interestingly, quinoline was the least studied of these cores despite being the first well-defined fluorophore.34

Fig. 3.

Core fluorescent scaffolds. Common scaffolds listed in order of increasing absorption values. R groups indicate sites for common functionalization.

Studying the dye family based on each core allows us to understand the distinct structure-photophysical property relationships of each scaffold and to generate plans for the development of future probes (Table 1). For instance, boron dipyrromethene (BODIPY) dyes generally have high brightness, but suffer from self-quenching, due to a small Stokes shift. On the other hand, coumarins and quinolines usually have large Stokes shifts, but generally exhibit blue-shifted (shorter wavelength absorption relative to that of fluoresceins or rhodamines). Each fluorescent core can be paired with other fluorophores to exhibit Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET). Coumarin (e.g. methoxycoumarin) can be combined with xanthone derivatives like acridones.35 Fluorescein and rhodamine derivatives are a widely used FRET pair, as those are the most modular and versatile scaffolds, with precisely tunable photophysical properties that have been optimized for imaging or for single molecule FRET studies.8, 36

Table 1.

Properties of Common Fluorophore Coresa

| Core | Coumarin | Quinoline | Fluorescein | BODIPY | Rhodamine | Cyanine |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absorption λabs (nm) | 373 | 349 | 500 | 505 | 512 | 789 |

| Emission λem (nm) | 445 | 450 | 541 | 515 | 530 | 817 |

| Stokes Shift (nm) | 72 | 101 | 41 | 10 | 18 | 28 |

| Molar Absorptivity ε (x104 M−1 cm−1) | 2.35 | 2.27 | 9.23 | >8.0 | 8.57 | 19.4 |

| Quantum Yield (θ) | 0.50 | 0.55 | 0.97 | 0.94 | 0.86 | 0.05 |

| Brightness (ε x θ) | 1.18 | 1.24 | 8.95 | 7.52 | 7.37 | 0.97 |

| Modulator | FRET (w/ Tryptophan) |

Aggregation induced Emission | FRET (w/ Coumarin) |

Homo-FRET | FRET (w/ Fluorescein) |

Photoswitchable (w/ Thiol) |

| Properties in water | Soluble Photostable | Insoluble Low Brightness |

Soluble Photobleaching | Soluble High Brightness |

Soluble Photostable | Poor solubility Photobleaching |

| Environmental Sensitivity | pH insensitive | Metal sensitive | pH sensitive | pH insensitive | pH insensitive | pH insensitive |

Notes. Data collected from PhotochemCAD™ and The Molecular Handbook. Representative photophysical values are from 7-diethylamino-4-methylcoumarin, quinine sulfate, fluorescein, BODIPY505/515, rhodamine123, and indocyanine green,37–39 but these values are subject to change depending on the substituents (Figure 5).

Modification of these cores has generated numerous synthetic dyes with a variety of utilities; however, only a small number of them are compatible with in vivo studies. In fact, only two (fluorescein and indocyananine green) are FDA-approved contrast agents for optical imaging in human health studies (ESI, Fig. S4).40 This shows that there is still a great need for “ideal”in vivo or live cell probes that are non-cytotoxic, red-shifted (i.e., long wavelength), substantially bright, and highly selective to the target of interest. The major bottleneck in ideal in vivo probe development is that some properties (e.g., low cytotoxicity and high selectivity, sensitivity, and photostability) under physiological conditions cannot currently be rationally designed or computationally predicted from first principles. One of the formidable challenges for in vivo imaging is the requirement of highly red-shifted spectra. Longer excitation wavelengths are needed to penetrate deeper into tissue and to avoid eliciting cellular autofluorescence (>750 nm excitation) and photon scattering for high-resolution or two-photon imaging (>1400 nm excitation). Additionally, the necessary instrumentation to readily analyze these red-shifted probes, such as infrared lamps for microscopy, are also not widely available.41

Addressing both predictable and unpredictable properties of small molecule probes, we will discuss how dye chemistry has been developed by a rational design approach. We survey the development of fluorophores over the past 20 years and highlight the exemplary use of sophisticated, custom-made probes. Understanding the chemistry that underlies the fluorophore design and synthesis is essential to inspire the design and creation of new, high-precision tools.

5. Rational Design of Fluorophores

Each step in the fluorescence process can be modulated by organic synthesis. To accelerate rational and efficient probe development, many efforts to understand the mechanism of each fluorescence process by computational chemistry have been made in recent years. Here, we detail a curated collection of fluorophores and highlight both general strategies and unique approaches that are employed to control fluorescence through rational design. Three general guidelines are considered for the design of new dyes at the present time. First, absorption and emission spectra of a fluorophore can be modulated by attaching electronically diverse groups to the fluorescent core. Second, the brightness of the fluorophore can be modulated by controlling photoinduced electron transfer (PeT) and restricting bond rotation. Lastly, the fluorescence readout can be modulated by utilizing interchromophore FRET42 or PeT. Each modulation method will be further discussed below.

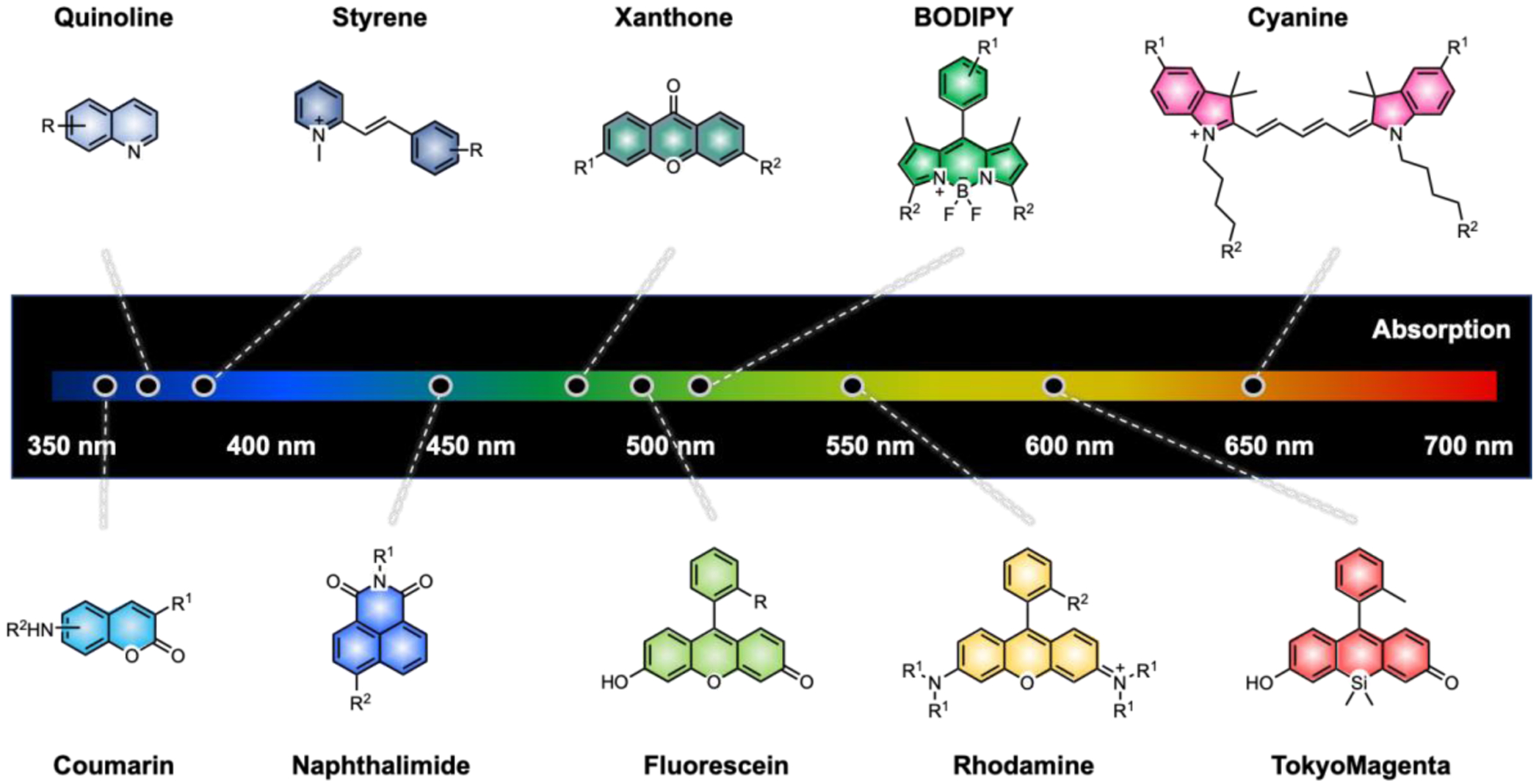

Intrinsic Properties (absorption/emission/ϕ/Stokes shift)

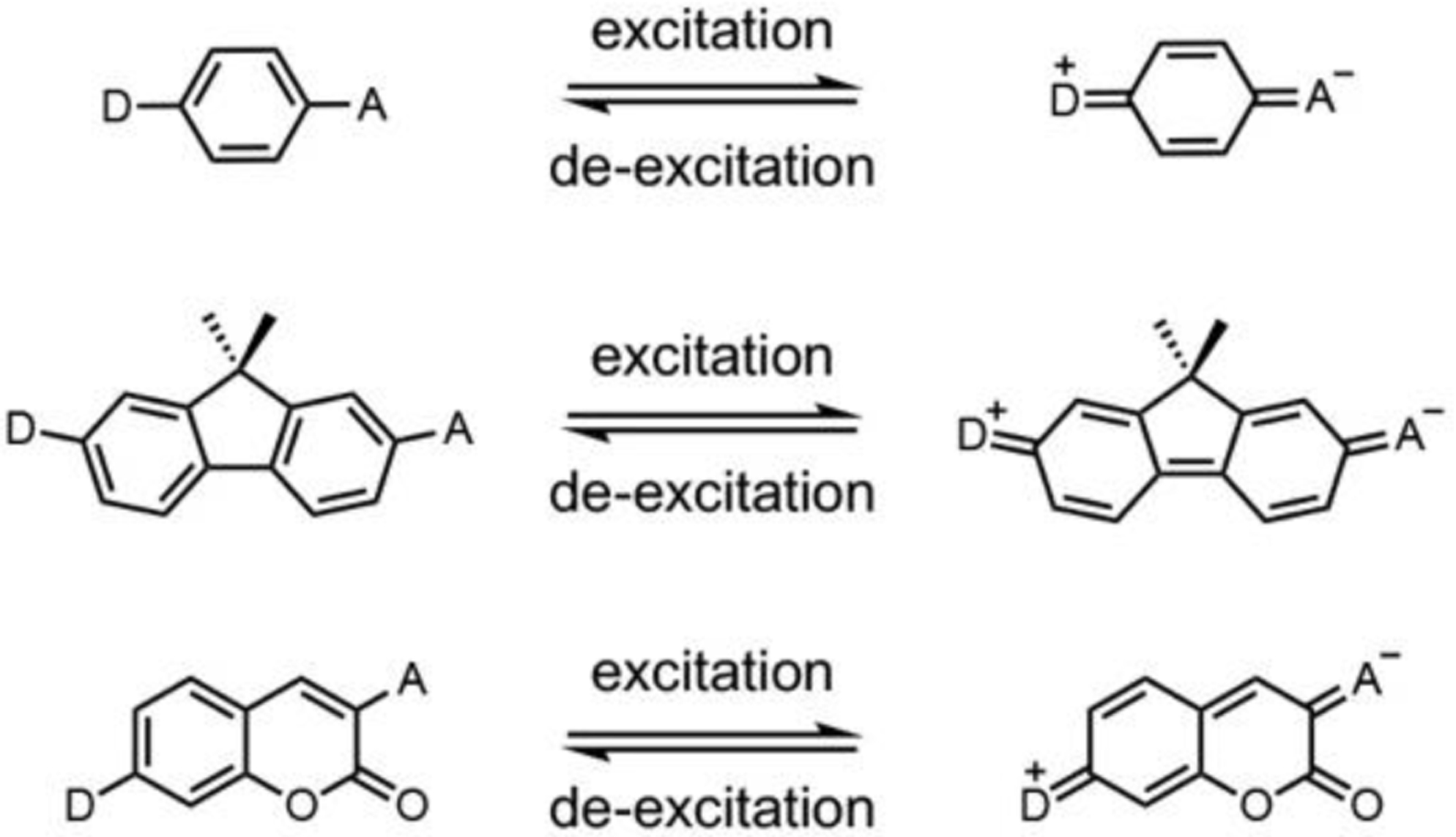

In general, a donor-π-acceptor moiety is the key structural framework to give fluorescence to small organic compounds (Fig. 4).43, 44 Within the core fluorophore, changes in the electronics of the donor-π-acceptor dye can cause changes in fluorescence.45, 46 An increase in the “push−pull” effect of electronics in dyes, whose excitation involves intramolecular charge transfer (ICT), results in a bathochromic (red) shift in their UV−vis absorption and emission spectra.34

Fig. 4.

Donor-π-Acceptor “Push-Pull” moiety in three fluorescent small molecule scaffolds. Donor (D) typically refers to aliphatic, aromatic, or saturated cyclic amines. Acceptor (A) frequently refers to formyl, succinyl, keto, or triazolyl electron withdrawing groups.

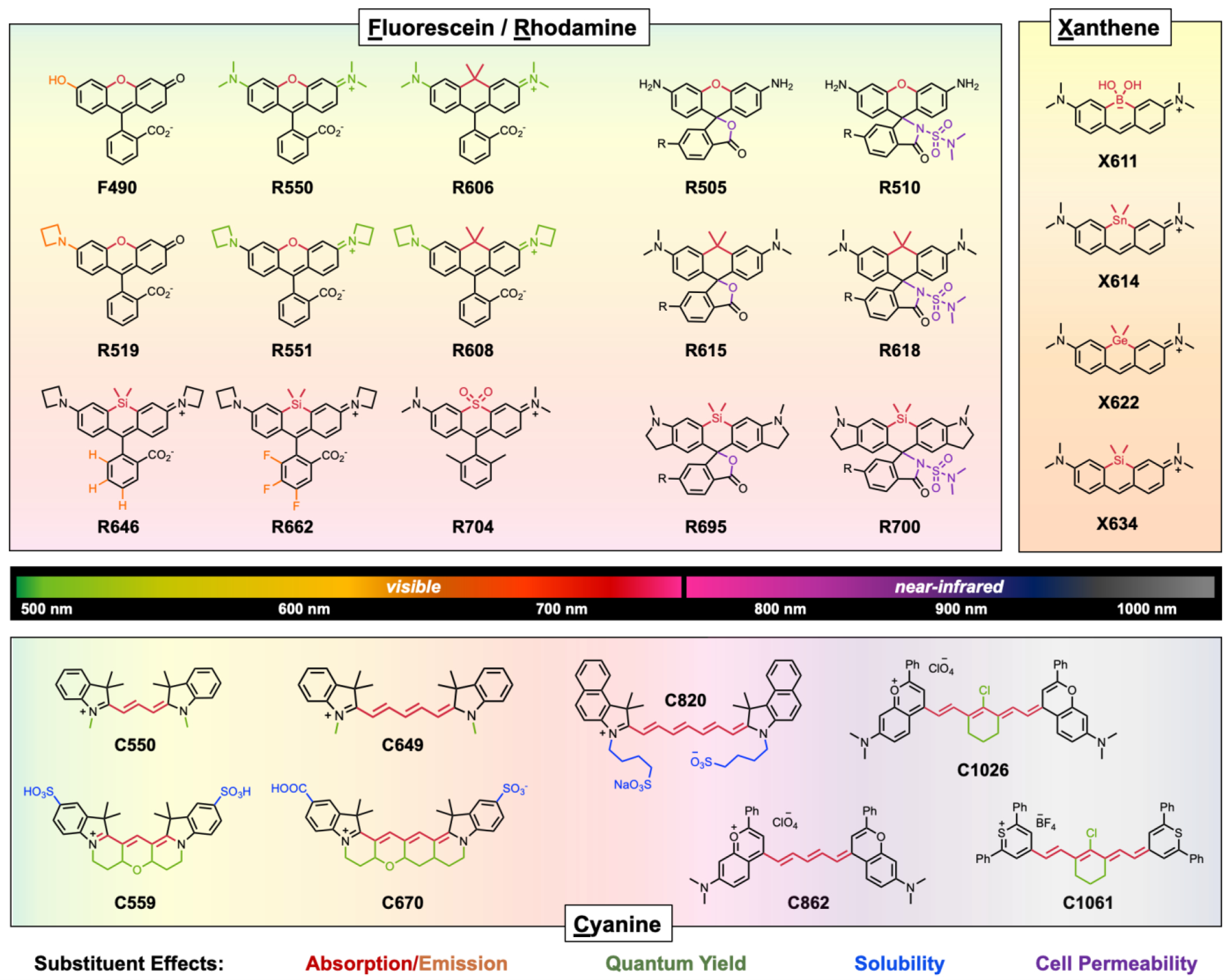

Additionally, expanding the π-conjugated network by appendages such as methylene moieties or aromatic substituents leads to a bathochromic shift and typically to an enhanced extinction coefficient (Fig. 5). Nagano and Lavis separately developed series of fluorescein and rhodamine derivatives with fine-tuned absorption and emission spectra by changing substituents.47, 48 Replacing the oxygen at the 10-position of fluorescein (compound F490) or rhodamine (compound R550) with a C or Si atom red-shifted λem up to 650 nm (R606, R646). Additional general methods to increase both absorption and the lactonization equilibrium constant (KL-Z regulates brightness, see details in Fig. 9B) were realized by fluorinating the pendant phenyl ring of rhodamine (R662).49 Near-Infrared (NIR) florescent dyes (λem>700 nm) are essential for live-cell and in vivo imaging because of deep tissue penetration, reduced phototoxicity, and lower autofluorescence of biological substances.50 A NIR rhodamine (R704) was achieved by modifying the 10-position of rhodamine to a sulfone group, exhibiting 700–704 nm absorption and 733–742 nm emission due to unusual d*−π* conjugation.51

Fig. 5.

Structure-photophysical relationship chart of visible and NIR dyes. From ‘top to down’ or ‘left to right’ within the core, increase in absorption and emission (red-xanthene substituent /orange-phenyl ring substituent), Increase in quantum yield (green), increase in cell permeability (purple), and increase in solubility in water (blue). Compound naming consist of first letter (F, R, X, or C) of core scaffold and its maximum absorption. R group is HaloTag ligand.

Fig. 9.

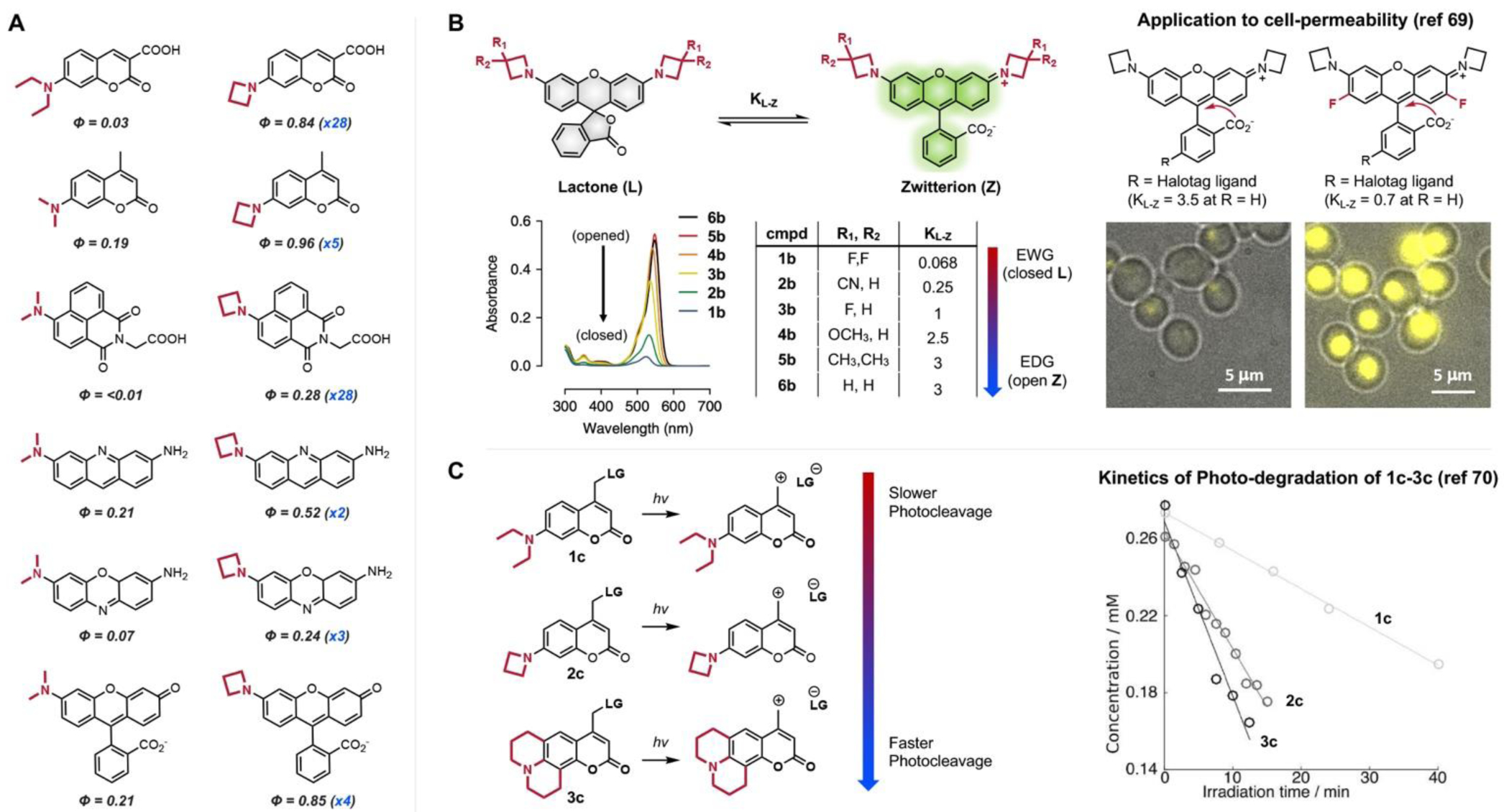

Effect of restricting the bond rotation of dialkyl amine by installing restricted azetidine. A. Improved quantum yields of fluorophore with azetidine than that with dialkyl amine. B. Electronic effect of azetidinyl ring in spirolactam equilibrium constant (KL-Z) and cell permeability.69 Adapted with permission from ref 69. Copyright (2019) American Chemical Society. C. Effect of the bond rotation in photocleavage.70 Adapted with permission from ref 70. Copyright (2018) Published by Royal Society of Chemistry

This general trend was also observed in xanthene chromophores (pyronines) supporting the use of xanthene as a an “antenna” for absorption in modular fluorophore design. Replacing the 10-position of the xanthene with boron (X611)52 or group 14 elements such as tin (X614), germanium (X622), or silicon (X634), showed bathochromic shifts compared to the oxygenated parent molecule.53 The trend indicated that the red-shift in absorption was due to stabilization of lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) energy levels by σ*−π* conjugation between σ* orbitals (Si-C, Ge-C, or Sn-C) and a π* orbital of the fluorophore.53

Absorption and emission of cyanine dyes can be red-shifted by extending the methylene bridge or modifying heterocycles with stronger electronic donating and accepting groups. Moving away from traditional NIR region (750–800 nm), the Sletten group has developed fluorophores in the shortwave infrared region of the spectrum with λem of 908 nm(C862) to 1045 nm (C1026) by utilizing a 7-dimethylamino flavylium heterocycle within the cyanine dye scaffold.41 Including the most bathochromic NIR agent, C1061, which is commercially available, most NIR agents suffer from problems of insolubility (Table 1). Thus, cyanine probes are generally utilized with nanoparticles or micelle carriers for biological imaging.54

Alteration of substituents can also contribute to improving Φ or water solubility of synthetic dyes.55–57 Briefly, Lavis and coworkers reported that azetidinyl substitutions in place of dimethylamino groups in rhodamine derivatives greatly enhance Φ without modifying absorption or emission spectra.57 Likewise, Michie and Renikuntla et. al. dramatically improved Φ of cyanine dyes by conformationally restraining the trimethine or pentamethine bridge (C559, C670).58, 59 Through installation of fused 6-membred rings to the polymethine bridge, the major deactivation pathway, excited-state trans-to-cis polyene rotation, is blocked. Hence, the photon output is maximized by reducing the energy loss.58

To overcome lipophilicity and water insolubility of synthetic dyes due to the planar structure of fused rings, sulfonate or carboxylic groups can be installed (C820). However, highly charged or polar fluorogenic probes can be limited by poor cell permeability possibly due to affinity for the cell membrane. Recently, the Johnsson group reported a general strategy to improve cell permeability of rhodamines and related fluorophores by simply converting a carboxyl group into an electron-deficient amide, N,N-dimethylsulfamide,(R510, R618, R700).60 By rationally tuning the lactonization equilibrium (KL-Z) with chemical modifications, amidated rhodamines showed increases in fluorescence up to 1,000-fold without affecting the spectroscopic properties of the fluorophore.

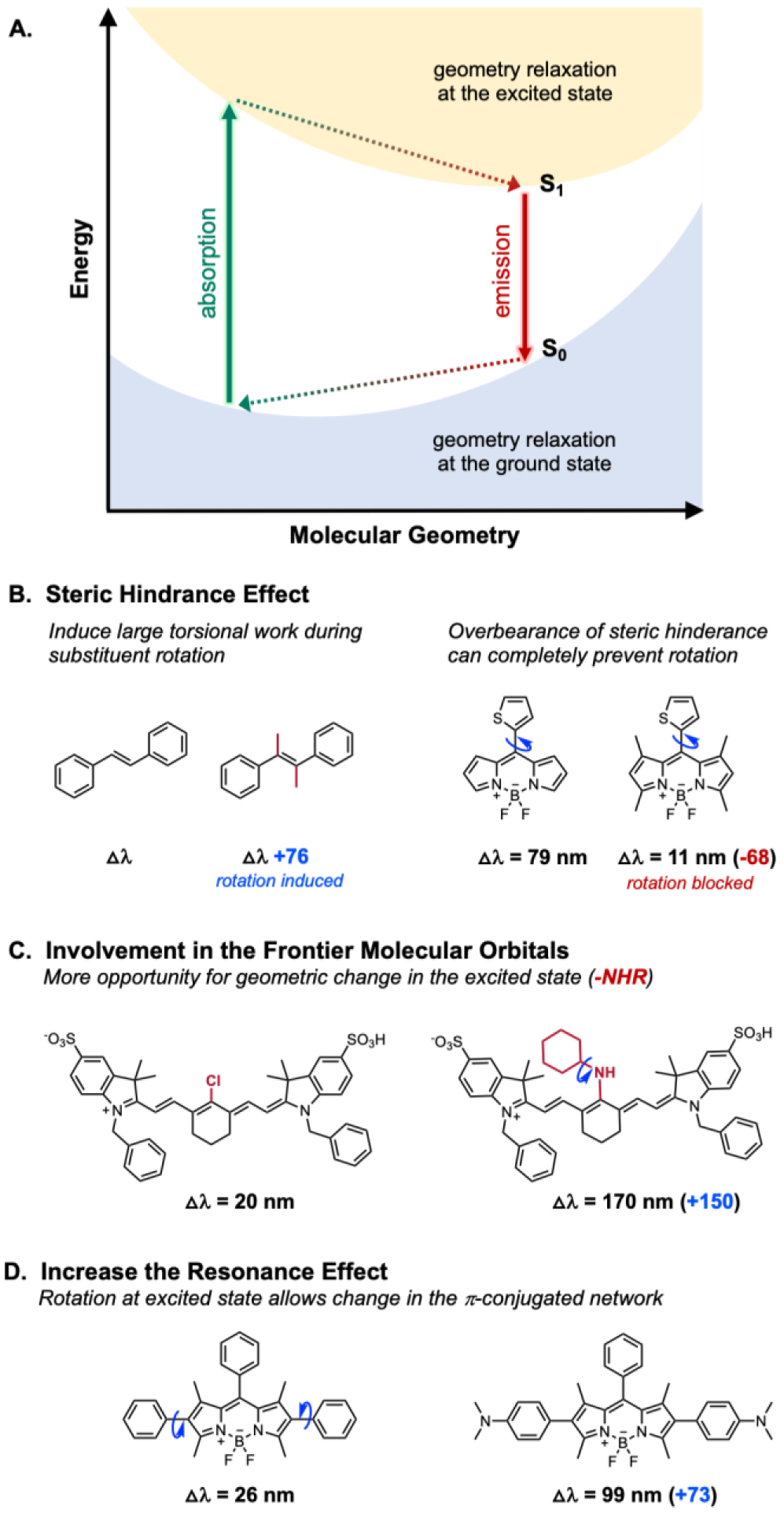

The addition of substituents to a fluorophore framework shifts not only the absorption but also the emission spectra. The main challenge in developing detailed strategies to modulate fluorescence is that multiple factors change upon a single modification. However, because substitution affects both the absorption and emission spectra, the Stokes shift generally remains unchanged. To modulate the Stokes shift, it has been suggested that a large structural change (e.g., the rotation of a key bond or substituent) upon its excitation leads to increased geometrical relaxation, resulting in a large Stokes shift (Fig. 6).61 Such molecular structure perturbations can be quantified by taking the root-mean-square (RMS) of the cumulative atomic displacements in comparison to the ground-state molecular structure. This geometry relaxation-induced change in Stokes shift can be found in biphenyl, 9-tert-butylanthracene, stilbene derivatives, heptamethine cyanine dyes, and BODIPY dyes (Fig. 6).40, 42, 43

Fig. 6.

Choice of rotating substituent on Stokes shift (△λ). A. Schematic illustration of absorption and emission process in fluorophore, B. Steric hinderance effect on Stokes shift, C. Effect of frontier molecular orbital in Stokes shift, and D. Resonance effect on Stokes shift.

PeT-Based Fluorescent Sensor

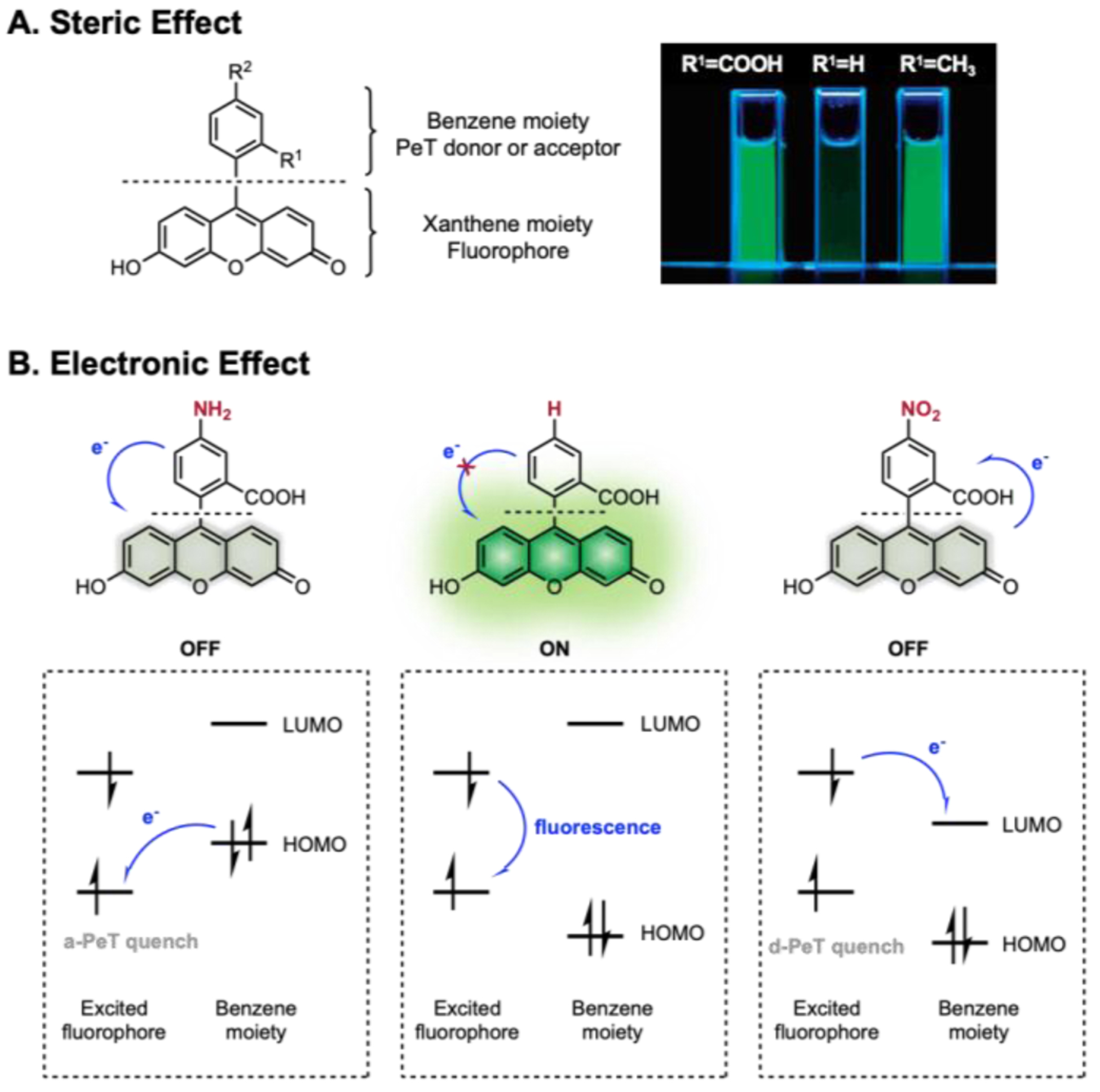

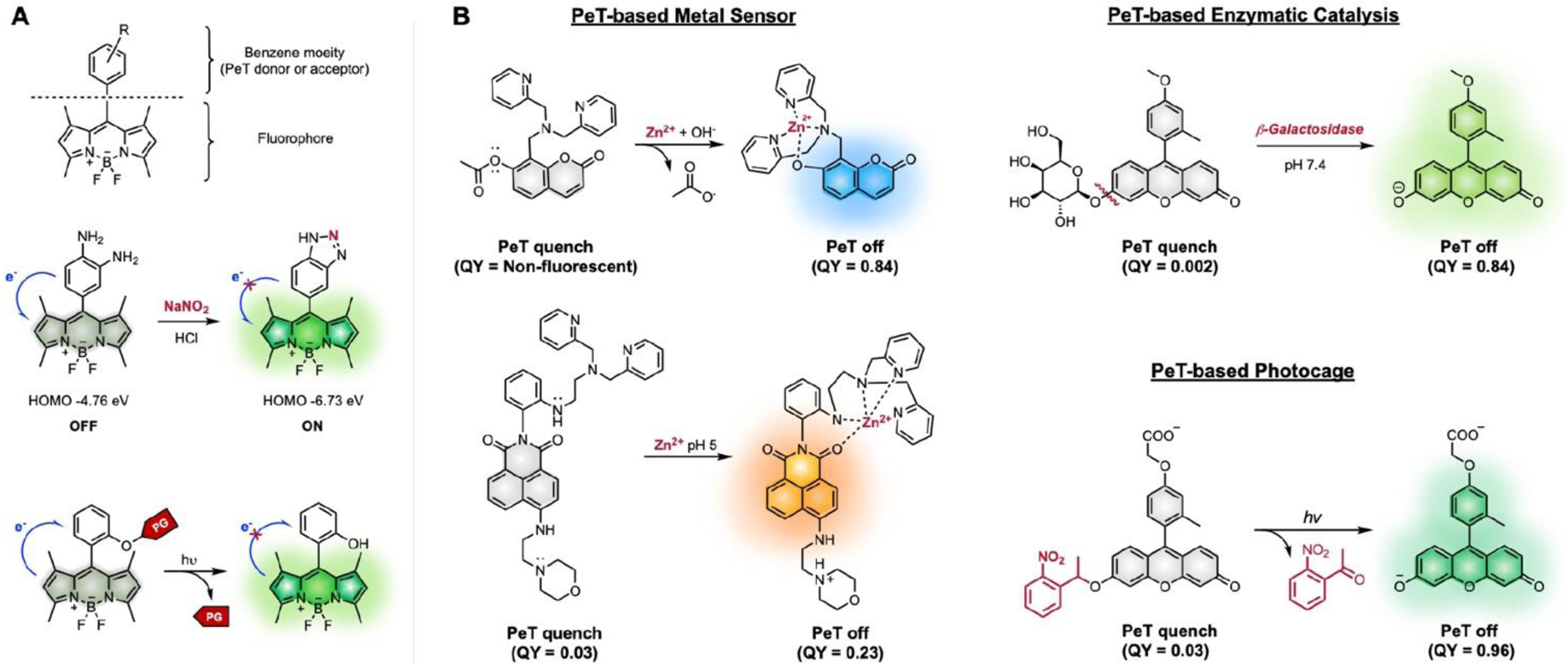

We can modulate the brightness (via Φ) of small molecule dyes through PeT or the tailoring of bond rotations. Fig. 7 presents a schematic representation of these different modes of modulation and corresponding examples of fluorogenic compounds based on the fluorescein scaffold.62, 63 This concept was successfully applied to BODIPY as well (Fig. 8).64 Nagano and co-workers have divided the fluorophore into acceptor and donor regions: the xanthene moiety is the source of fluorescence, and the benzene moiety acts as an intensity switch.65, 66 The benzene moiety can be either a PeT donor or acceptor depending on the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO)-lowest occupied molecular orbital (LUMO) gap relative to that of the xanthene moiety. Fig. 8A shows that the PeT-based molecular switch can be tuned by installing steric groups in the benzene moiety. Although the fluorescein derivative with the unsubstituted benzene ring is weakly fluorescent, those with substituted benzene rings are highly fluorescent. This demonstrates that the steric bulk of the group at R1 reduces the PeT quenching in fluorescence by keeping the benzene moiety orthogonal to the fluorophore.62 Fig. 7B shows that the molecular switch can also be modulated by introducing electronic substituents that change the HOMO-LUMO levels. Fig 9 shows that the change in electronic properties of substituents upon structural modification leads to either suppression or restoration of fluorescence. The most straightforward method for structural modification is to install a protecting group onto the dye to suppress fluorescence, which can later be removed by external stimuli to restore fluorescence. Such protecting groups can be light-sensitive photocages, enzyme-cleavable linkers, or other covalent bonds that can be removed upon exposure to chemical stimuli. Initially suppressed fluorescence can be restored by an enzyme-catalyzed reaction, photolysis, or other bond cleavage event. Expanding this chemical concept, zinc sensing and enzymatic or photoactivable probes have been developed (Fig. 8).31, 67

Fig. 7.

Rational design of PeT-based fluorescein scaffold. A. Steric effect of R1 in modulating PeT by rotation restriction of benzene moiety. B. Electronic effect of R2 in modulating PeT by tuning HOMO/LUMO of benzene moiety. Adapted with permission from ref 62. Copyright (2005) American Chemical Society.

Fig. 8.

Examples of PeT based turn-on probes.67. A. Development of PeT-based sensors in BODIPY scaffold. Chemical stimuli (nitric oxide) or light to change stereo-electronic property of benzene moiety via chemical modification or removal of photocleavable protecting group (PG), respectively. B. PeT-based sensors utilizing metal, enzyme, or light.

Tuning Bond Rotations

Another general method to modulate brightness or Φ of fluorophores relies on restricting bond rotation. Lavis and co-workers have shown that installing azetidine in place of a dimethylamino donor greatly enhances brightness by increasing the rotational barrier and eliminating quenching through twisted ICT (Fig. 9).49 Azetidinyl substituents have improved the fluorescence quantum yield of several classes of fluorophores (Fig. 9A). The azetidinyl moiety has also been shown to tune the ring opening-closing equilibrium (KL-Z), which dictates important parameters of rhodamine dyes (Fig. 9B). Electron-withdrawing groups on the azetidine force the molecule to adopt a “closed” lactone form (L), which is nonfluorescent, while electron donating groups favor the “open,” highly fluorescent, zwitterionic form (Z) of rhodamine. Precise control of the open–closed equilibrium in rhodamine provides a rational guideline to modulate brightness and cell-permeability.49, 57, 68 For a smaller KL-Z, rhodamine exist more in the L form, which is non-fluorescent, but highly cell-permeable due to lipophilicity. KL-Z can also play a role as a turn-on probe when rhodamines are used as a fluorogenic ligand as shown in Fig. 9B. In order to improve cell permeability, the electron density of the xanthene core was decreased via fluorine substitutions, resulting in an even smaller KL-Z than for the non-fluorine substituted probe (Fig. 9B). A recent study showed that a KL-Z between 10−2 and 10−3 is needed for rhodamines to have effective fluorescence turn-on up to 10-fold upon binding to their protein targets.69

Lastly, restricting the rotation of the dimethylamino group in a coumarin photocage has also been shown to improve the efficiency of photocleavage (Fig. 9C). As azetidinyl substitution increased Φ, and this relationship was utilized to modulate photochemical process of photocages. A series of photocleavable coumarins (1c-3c) were tested for photorelease by measuring the disappearance of starting material upon irradiation.70 Similarly, the KL-Z of fluorescein can be modulated via acetylation of the phenolic oxygens.8, 71, 72 Acylated fluorescein diacetate forces the molecule to adopt a nonfluorescent “closed” lactone form and the “open” form fluorescein can be generated upon hydrolysis of those acetates.

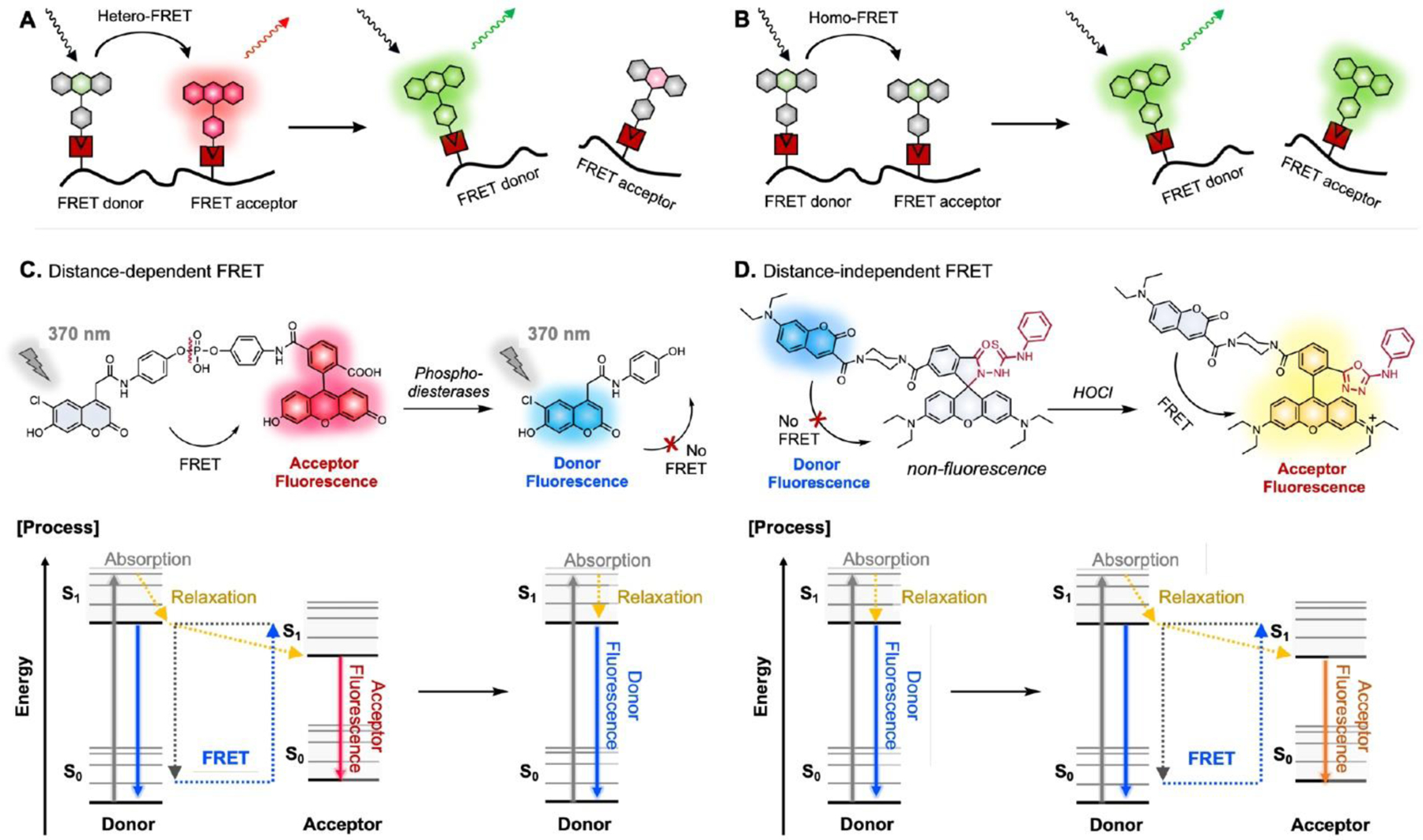

FRET-Based Fluorescent Sensor

Another approach to modulate fluorescence is to use FRET or interchromophore PeT. FRET requires energy transfer from the excited state of one “donor” dye to another “acceptor” dye (Fig. 10).36 Generally, two structurally distinct dyes are assigned as a

Fig. 10.

A. General scheme for hetero-FRET and homo-FRET. C-D. Distance dependent/independent FRET and its photophysical process in Jabłoński diagram.36

FRET-pair, where the FRET efficiency is related to the overlap of regions of the emission spectrum from the donor fluorophore and the absorption spectrum of the acceptor dye. Homo-FRET can also occur between two dyes with the same structure if there is a small Stokes shift (Fig. 10B). Such energy transfer mechanism can be useful for versatile applications: for instance, BODIPY dyes, which show small Stokes shifts of <20 nm, can be utilized as homo-FRET probes (Table 1).73, 74 In one example, calpain and casein proteins over-labelled with BODIPY dyes in close proximity are auto-quenched because homo-FRET among BODIPYs increases the probability of non-radiative processes occurring.73 Upon calpain proteolytic activity, fluorescence increased as the BODIPY dyes got farther apart.

Metal-Based Fluorescent Sensor

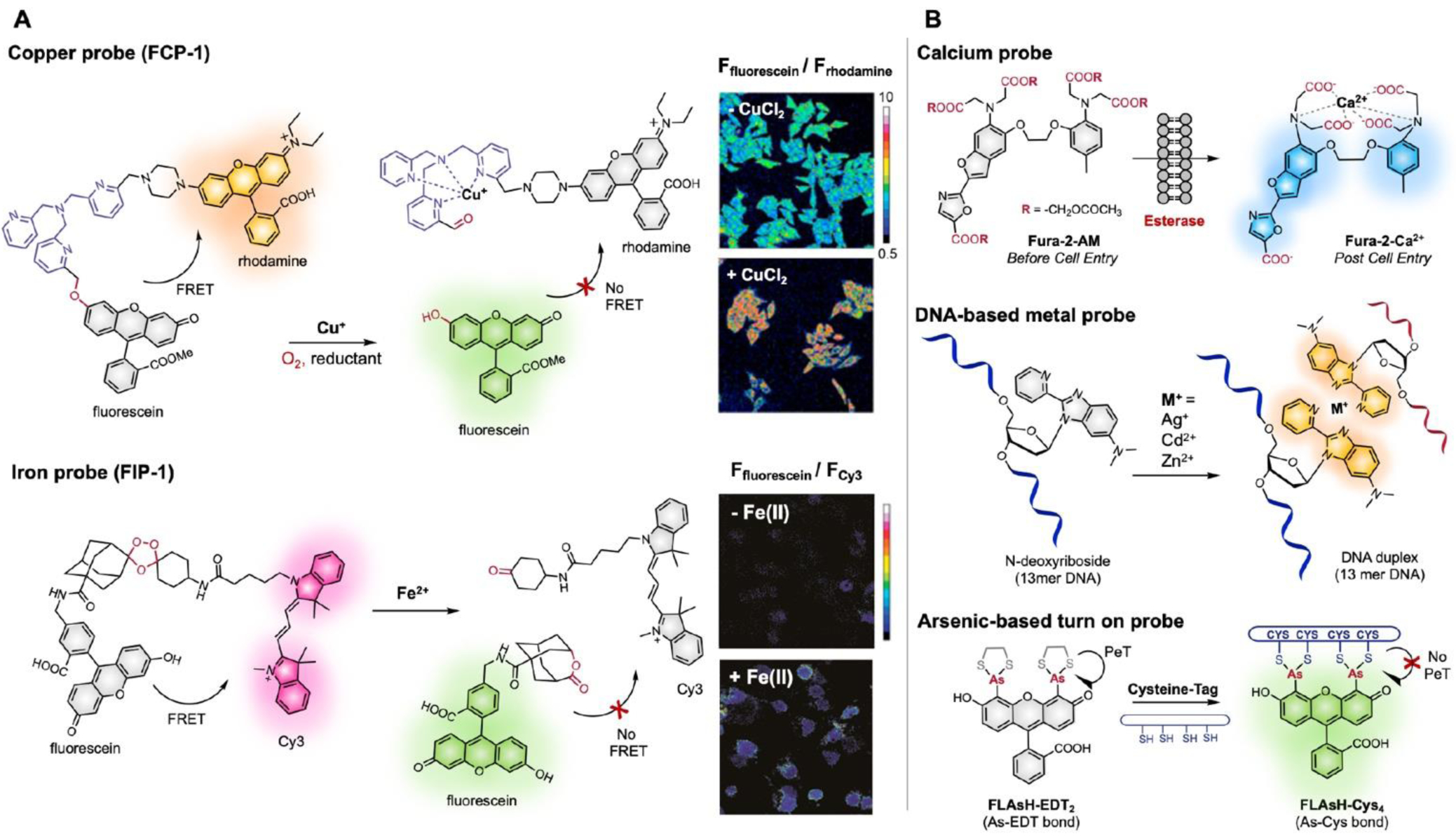

Previous sections discussed several methods to modulate photophysical properties of fluorophores with rationally designed chemical modifications. The utility of these probes can be further extended by incorporating metals in controlling fluorescence output. These metal-based sensors can be divided into two main categories: activity-based fluorescent probes triggered by metals (molecular reactivity) and metal-chelating probes (molecular recognition).75 Probes in the first category have been extensively explored by Chris Chang, including several biologically important metal (e.g. Cu+, Fe2+) detecting probes based on molecular reactivity.76 To develop ratiometric fluorescent probes, a copper probe (FCP-1) used a Tris[(2-pyridyl)methyl]amine bridge between a FRET pair (fluorescein donor and rhodamine acceptor), which can be oxidatively cleaved upon coordination of Cu(I) to the bridge.77 Similarly, an iron-selective fluorescence probe (FIP-1) was developed with a Fe(II) cleavable endoperoxide bridge between a FRET pair (fluorescein and Cy3).78 The second category exploits metal-based sensors by utilizing metal-chelating groups. Fura-2 is one of the most commonly used ratiometric fluorescent dyes for quantitative [Ca2+] measurement.79 Fura-2 AM is an esterified cell permeable form of Fura-2. As esterase enzymes cleave the ester groups (R) of Fura-2 AM, the free acid of Fura-2 is released to bind Ca2+, which changes the Fura-2 λabs from 380 nm (Ca2+ free) to 340 nm (Ca2+ bound).79 The Kool group localized fluorescence sensing of metal ions to DNA by developing novel fluorescent N-deoxyribosides having 2-pyrido-2-benzimidazole groups.80 Though the probe lacks selectivity toward one specific metal, substantial enhancements in emission intensity with Ag+, Cd2+, and Zn2+ are seen, even after the probe in incorporated into oligonucleotides (13mer DNAs). Lastly, metals can also be utilized as part of a biomolecule labelling sites. Tsien and coworkers reported a membrane-permeable non-fluorescent arsenic(III)-based probe called FLAsH-EDT2 (EDT = ethanedithiol) that fluoresces upon binding to a liner amino acid sequence including four cysteines.81 The mechanism for fluorescence turn-on when bound to the tetracysteine motif can be a change in orbital alignment due to hindered rotation or a decrease in ring strain, eliminating PeT quenching.82

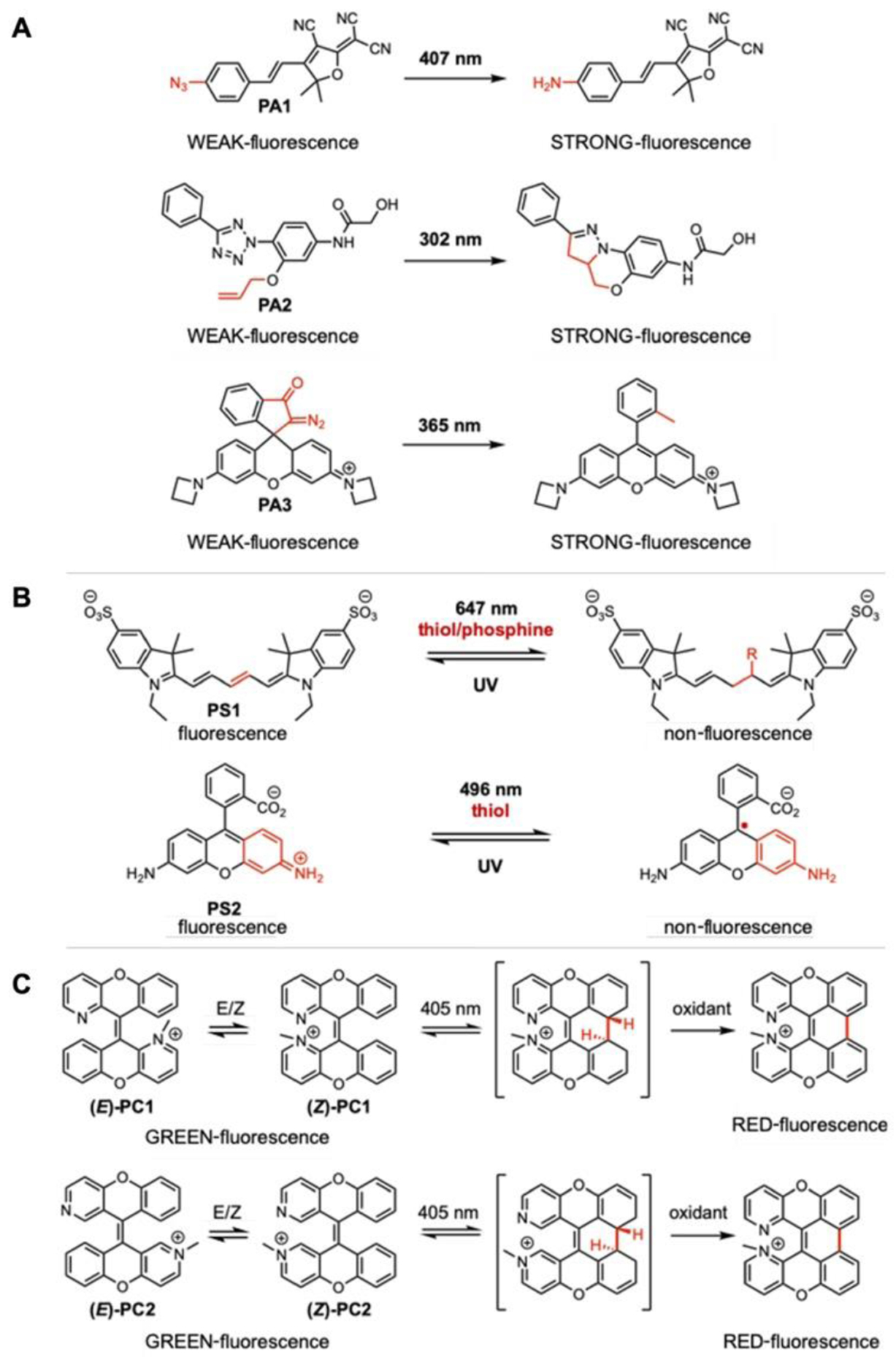

Optically Controlled Fluorescent Sensors

The utility of fluorogenic probes can be further extended by developing them into photo-activatable fluorescent dyes, a group of activatable fluorophores that can be triggered by light. Photoactivatable dyes are compatible with many of the recently developed super-resolution microscopy techniques such as stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy (STORM) and (fluorescence) photoactivated localization microscopy ((F)PALM).83 These dyes are generally grouped into three categories: photoactivatable, photoswitchable, and photoconvertible molecules. Photoactivatable probes switch from a weakly fluorescent “off” state to a strongly fluorescent “on” state upon illumination (Fig. 12A). Similarly, photoswitchable probes switch “on and off” but in a reversible manner (Fig. 12B). In contrast to photoactivatable and photoswitchable probes, photoconvertible dyes are initially “on” but change their fluorescent emission spectrum by irradiation with light (Fig. 12C).84, 85

Fig. 12.

A. Examples of photoactivatable dyes that undergo irreversible fluorescence off to ON (i.e., turn-on), B. examples of photoswitchable dyes with reversible fluorescence on and off, and C. examples of photoconvertible dyes with irreversible change in fluorescence from one to the other (e.g., change from green to red fluorescence) upon light illumination.

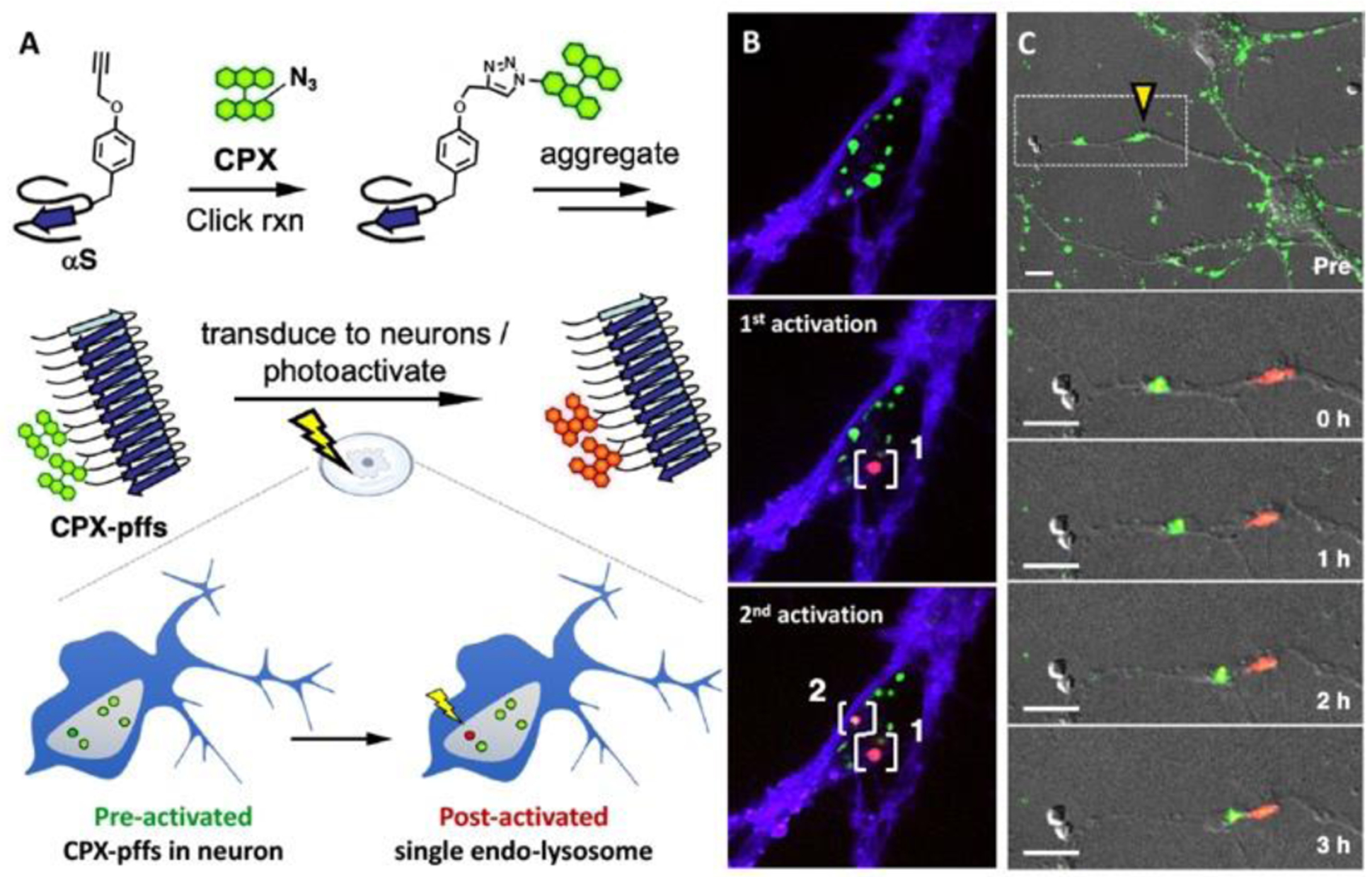

A variety of photoactivatable fluorescent probes have been previously reported (Fig. 12). Photoactivation can occur by azide decomposition (PA1), a “photo-click” reaction (PA2), and by uncaging photolabile protecting group (PA3). Photoswitching can be achieved by light-activation, reversible thiol or phosphine addition to the polymethine chain of Cy5 (PS1), or by the generation of a long-lived reduced non-fluorescent radical in a rhodamine dye (PS2). A stable radical anion of rhodamine dye, which can survive up to several hours, is generated when the triplet state of the dye is quenched by thiol or oxygen in aqueous solution yielding thiyl radical or singlet oxygen species.86, 87 Unlike previously described “on and off” probes, the number of reported photoconvertible small molecules are extremely low. Generally, a photoconvertible effect was achieved by using light as a source to cleave the linker between two FRET pairs.88 Recently, Chenoweth and coworkers serendipitously discovered diazaxanthilidene-based compounds (PC1,PC2) that change emission from green to red via photo-electrocyclization and oxidation reactions.84, 85, 89 The Chenoweth and Petersson groups further expanded the utility of PC1 into a clickable and photoconvertible probe, termed CPX, that can be conjugated to any targets through azide−alkyne cycloaddition. They successfully demonstrated that CPX labelled α-synuclein (αS) aggregates can be transduced to live neurons, where a single lyso/endosome can be precisely photoconverted in a spatiotemporally controlled manner to allow tracking over its intracellular fate (Fig. 13).85

Fig. 13.

Application of photoconvertible probe (PC1) in tracking α-synuclein (αS). A. Synthesis and transduction of CPX labelled preformed fibrils of engineered αS (CPX-pffs) B. Sequential photoconversion of internalized CPX-pffs in white brackets. (blue channel: trypan blue staining extracellular membrane, green channel: unactivated CPX-pffs, and red channel: post-activated CPX-pffs) are shown in merged images. C. Tracking of CPX-pffs under yellow triangle after irradiation, zoomed in (white dotted box) below. Merged images of differential interference contrast (DIC), green and red channels are shown. Scale bars are 10 μm. Adapted from ref 85. Copyright (2019) American Chemical Society.

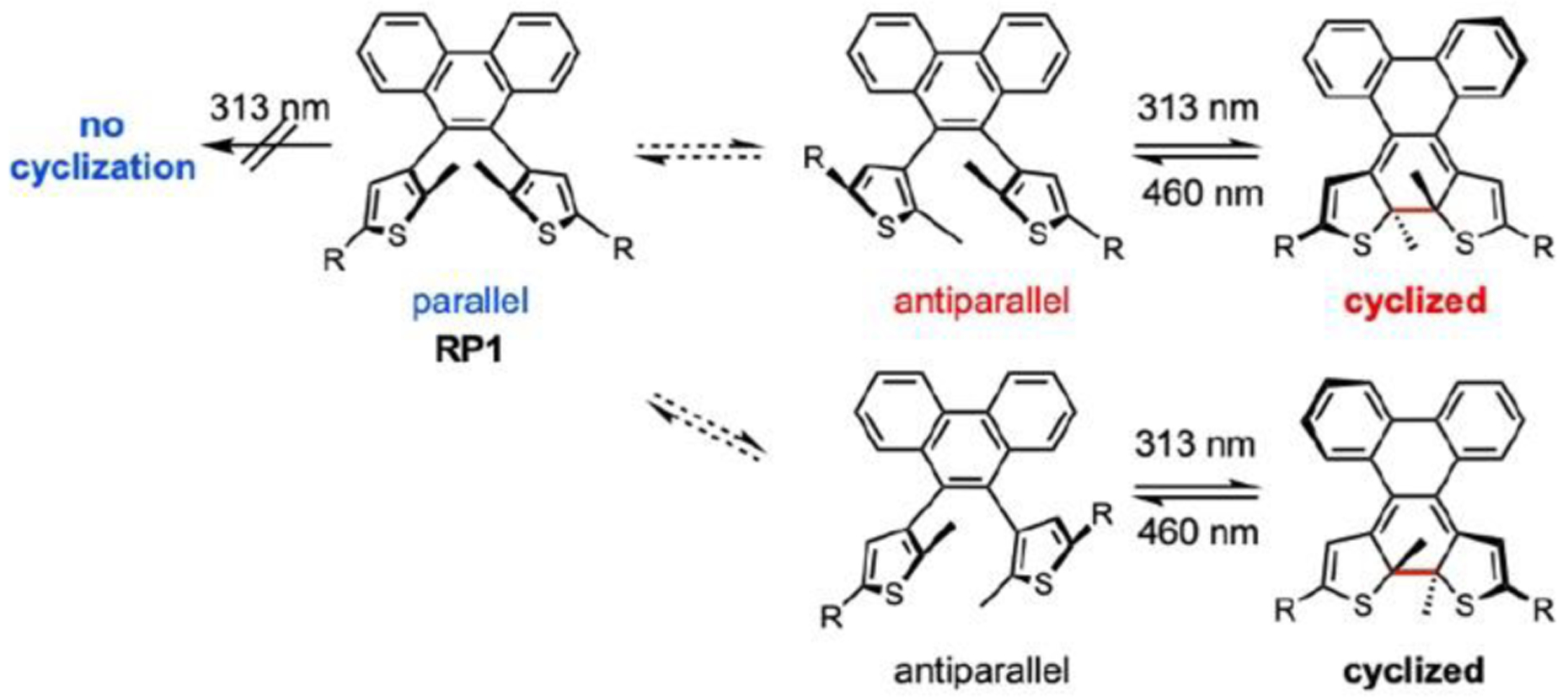

Whereas PC1 and PC2 undergo irreversible photocyclization, 2016 Nobel Laureate Ben Feringa and coworkers have generated compounds incorporating an ethene bridge with 2,5-substituted thiophene groups (RP1) display reversible fluorescence switching upon photo-isomerization (Fig. 14).90 Just as the Nobel Prizes awarded for GFP and super-resolution microscopy signalled large shifts in fluorophore research, we envision that the 2016 Nobel Prize will demarcate an increase in research on optically-controlled fluorescent sensors.

Fig. 14.

Reversible photocyclization processes of atropisomeric dithienylethenes (RP1). Reversible switching of a conformational isomer (antiparallel rotamer only) upon irradiation.

Rational Design and Beyond

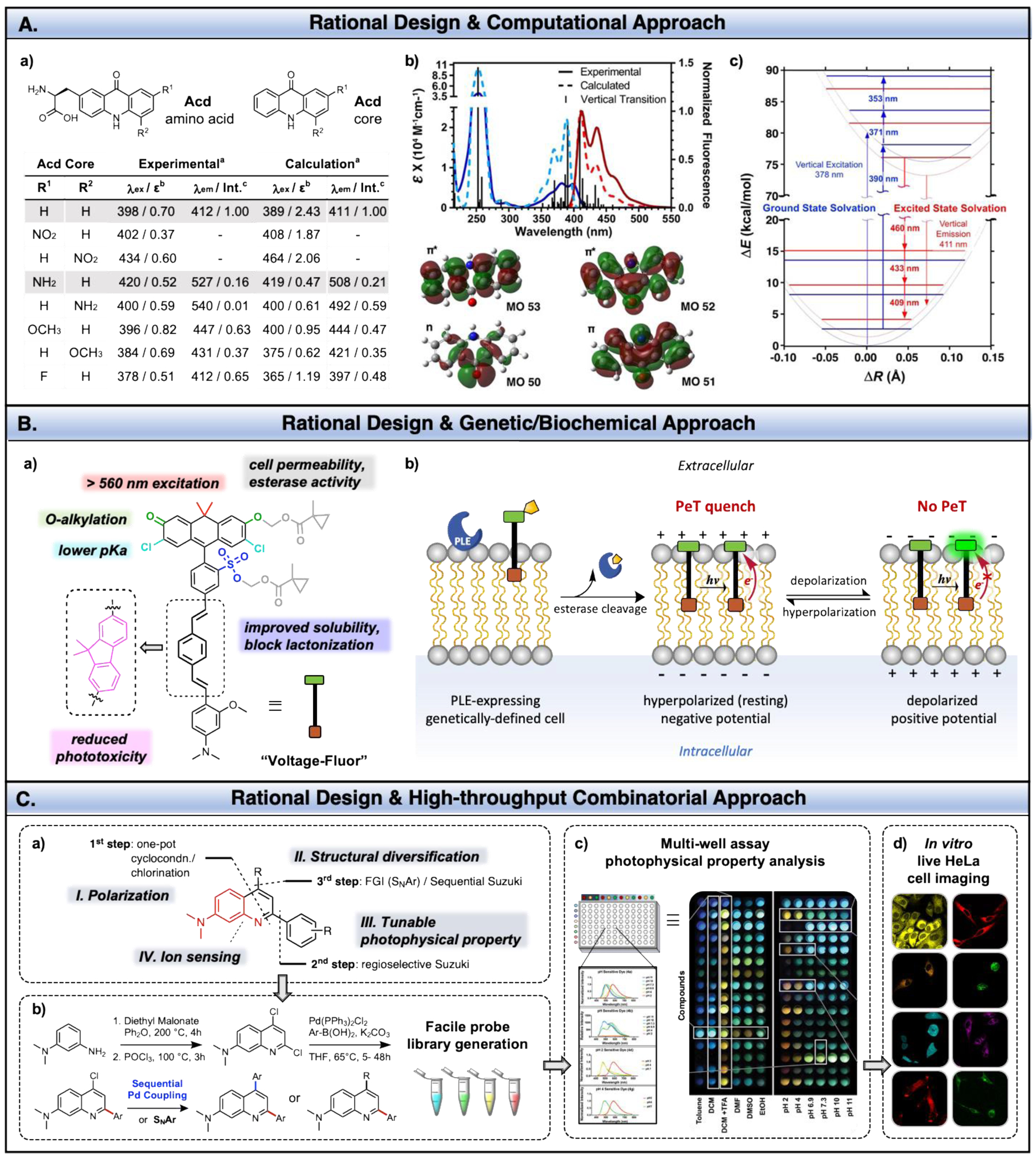

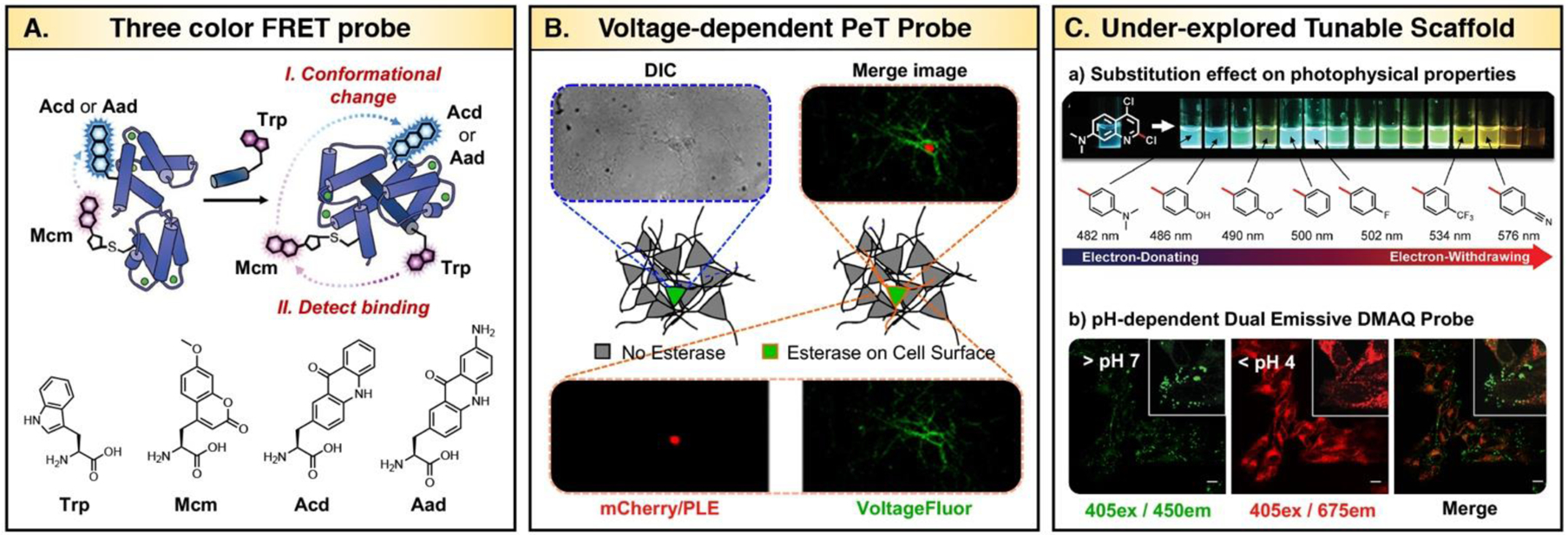

In the last part of this review, we highlight progress and guidelines for fluorescent probe development through ‘rational’ design. Emphasis is placed on combining the rational design approach with other methods to discover novel or underexplored probes. We have summarized representative examples of cases showing how rational design has been applied in parallel with computational analysis, genetic engineering, or combinatorial approach to build unprecedented multi-functional probes (Figs. 15 and 16).

Fig. 15.

A. Design and photophysical properties of acridonylalanine (Acd) based probe. a) Calculated and experimental values of Acd core derivatives. aLowest energy absorption and highest intensity emission values. bExtinction coefficients (ε) reported as 104 M‐1 cm‐1. c Normalized emission intensity (Int.) of the highest emission of acridone (R1, R2 = H). b) Franck‐Condon corrected spectra with molecular orbitals (MOs) involved in the n→π* and π → π* transitions of acridone (R1,R2=H). c) Jabłoński diagram of frozen ground or excited state solvation. Adapted from ref 96. Copyright (2018) John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. B. a) Rational design of Voltage-Fluor. b) Scheme of voltage-sensitive fluorescence mechanism is shown. Membrane labelling of Voltage-Fluor to porcine liver esterase (PLE)-expressing cells. At rest, negative membrane potential (hyperpolarized) enhances PeT quenching and diminishing fluorescence. Upon depolarization, the positive membrane potential reduces PeT quenching, resulting in enhanced fluorescence. C. a) Modularity and b) synthesis of dimethylamino quinoline (DMAQ) dyes. Stream-line probe discovery from scaffold design to c) multi-well plate reader analysis followed by d) live cell imaging. Specific examples of applications of these fluorophores are shown in Fig. 16. Adapted from ref ref 34. Copyright (2019) American Chemical Society.

Fig. 16.

A. Three color FRET to detect binding (Trp excitation) and conformational change (Mcm excitation) simultaneously. Adapted from ref 35 and 96. Copyright (2018) John Wiley & Sons, Ltd and Copyright (2017) Published by The Royal Society of Chemistry B. Functional imaging in neurons with Voltage-Fluor. Differential interference contrast (DIC) images of neurons, nuclear-localized mCherry to indicate PLE expression, wide-field fluorescence images of Voltage-Fluor on membrane, and merged images of Voltage-Fluor and mCherry. Adapted from ref 99. Copyright (2017) American Chemical Society. C. a) DMAQ domain allotted for tunable photophysical property is shown. A range of aryl substitution with emission maximum under 405 nm excitation is shown. b) Confocal imaging of DMAQ probe with two-stage fluorescence response to intracellular pH. Excitation laser (λex) and emission filter (λem25 nm) used for imaging is indicated as 405ex/450em. Adapted from ref 34. Copyright (2019) American Chemical Society.

One of the remaining challenges is to accurately predict photophysical properties by quantum calculation.31 Recently, progress has been made by performing systematic studies of a single fluorescent core scaffold assuming that its derivatives will undergo similar nonradiative decay.91 For instance, Park and coworkers successfully extrapolated the linear relationship between the calculated energy gap (S0 and S1 states using time-dependent DFT) and the wavenumber (1/λem) of indolizine-based fluorophore (Seoul-Fluor) analogues to predict λem of “virtual” Seoul-Fluor derivatives.91 Unlike many reports based on gas-phase calculations, Petersson and coworkers optimized and improved the calculations to represent aqueous solution λabs and λem spectra of derivatives of fluorescent unnatural amino acid acridonylalanine (Acd), used previously in protein labelling (Fig. 15A).92–95 They performed ab initio electronic structure calculations (APF‐D density functional, Gaussian16™, 6‐311+G(2d,p)) and vibrational calculations to generate Franck‐Condon corrected spectra. Calculated wavelengths and intensities of the π → π* transition, which is important in microscopy and spectroscopy applications, agreed well with the experimental data validating the success of this theoretical approach to guide synthetic efforts.96 Screening different substituents on the Acd core predicted aminoacridonylalanine (Aad) to be a superior FRET partner for methoxycoumarinylalanine (Mcm) than the parent Acd. This non-classical Acd/Mcm FRET pair was applied in three color FRET experiments with tryptophan (Trp) to simultaneously monitor multiple interactions of proteins (Fig. 16A).35

It should be noted that fluorescent amino acid probes are designed in forms appropriate for site-specific genetic incorporation by tRNA synthetases, which requires synthetic effort as well as genetic engineering.95 Likewise, now the effort on rational probe design has expanded to both synthetic and genetic means. Miller and coworkers reported a series of PeT-based fluorescent voltage indicators, called Voltage-Fluors, for studying membrane potential (Figs. 15B and 16B).97 Voltage-Fluors consist of a xanthene based fluorescent reporter (fluorophore) and an electron-rich aniline (PeT donor) bridged by a conjugated molecular wire that facilitates PeT as well as membrane-specific localization.98 Here, efficiency of PeT is dictated by the changes in the membrane voltage.

The carbofluorescein skeleton was chosen to have red-shifted excitation (>560 nm) in the presence of oxygen substitution at the 3’ and 6’ position for O-alkylation. A sulfonic acid functional group and chlorines were installed to reduce spirocyclization, which is a nonfluorescent configuration.98 Alkylation with a hydrolytically stable ether at phenolic oxygen also results in weak fluorescence, but it is designed to restore the fluorescence when the ether bond is cleaved by exogenously expressed porcine liver esterase (PLE).99 Lastly, Boggess et al. showed a fluorene-based molecular wire in place of the canonical phenylenevinylene moiety substantially decreased phototoxicity.100

As Voltage-Fluors demonstrated, the high modularity of fluorescein scaffold can be leveraged to make highly functional probes. The majority of early work has focused on manipulating chemical structures of conventional scaffolds such as fluorescein or rhodamines. Thus, there is still a need for non-traditional scaffolds, which allow for the rational design of molecules with predictable photophysical properties and are readily synthesized for high-throughput screening. To meet those requirements, Jun, Petersson, and Chenoweth introduced a highly modular quinoline-based probe, called DMAQ (Fig. 15C).34 DMAQ contains four strategic domains that are allotted for (I) compound polarization, (II) structural diversity, (III) tuning of photophysical properties, and (IV) ion sensing. The library of DMAQ was synthesized in two to three steps from commercially available starting materials enabling combinatorial development of structurally diverse quinoline-based probes. This work highlights an efficient strategy in rational design and stream-lined probe analysis in a high-throughput manner to reveal unique properties of underexplored quinoline-based probes such as a pH dependent dual emissive property (>170nm shift, Fig. 16C).

6. Conclusions and Perspective

This review has summarized current methods to modulate the fluorescence of synthetic dyes and sensors in biological applications. The rational design approach has successfully improved intrinsic photophysical or chemical properties of the dyes in a test tube (or in vitro), but the behaviors of dyes in a physiological setting are still unpredictable.67 Designing probes for in cellulo or in vivo experiments is an additional challenge due to the intricate and dynamic nature biological systems.40 Moreover, the oft-used dyes in biochemical research are still limited to a few fluorogenic core families shown in ESI Fig. S4.

The development of new fluorophores is still largely based on trial-and-error or by serendipitous discovery. Addressing these issues, the combinatorial chemistry approach has sped up the probe discovery process with efficient syntheses of diversity-oriented fluorescent libraries, or DOFLs, by Yong-Tae Chang (ESI, Fig. S5–S7).101 With DOFLs, a series of cell-permeable and highly selective probes were successfully discovered and helped to revolutionize the fluorophore field. Taken together, rationally designed, tunable fluorescent cores can be used to generate DOFLs through combinatorial synthesis methods for high-throughput analysis which can then further inform a rational understanding of photophysical properties, a combined approach to enable design a next generation of fluorophores with improved optoelectronic properties.

Supplementary Material

Fig. 11.

Examples of activity-based metal sensing probes (left),77, 78 and metal-chelation based probes (right). Adapted from ref 77 with Copyright (2016) American Chemical Society. Adapted from ref 78 with Copyright (2019) National Academy of Science

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by funding from the University of Pennsylvania, National Science Foundation (NSF CHE-1708759 to E.J.P.), and National Institutes of Health (Grant NIH R01-GM118510 to D.M.C.).

Footnotes

Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available: Additional figures and literature data analysis. See DOI: 10.1039/x0xx00000x

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

Notes and references

- 1.Lavis LD and Raines RT, ACS Chemical Biology, 2014, 9, 855–866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Silva AP, Gunaratne HQN, Gunnlaugsson T, Huxley AJM, McCoy CP, Rademacher JT and Rice TE, Chemical Reviews, 1997, 97, 1515–1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnson I, The Histochemical Journal, 1998, 30, 123–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Staderini M, Martín MA, Bolognesi ML and Menéndez JC, Chemical Society Reviews, 2015, 44, 1807–1819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alamudi SH and Chang Y-T, Chemical Communications, 2018, 54, 13641–13653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shaner NC, Steinbach PA and Tsien RY, Nature Methods, 2005, 2, 905–909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Denis S and Aaron MM, Current Medicinal Chemistry, 2018, 25, 1–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lavis LD and Raines RT, ACS Chemical Biology, 2008, 3, 142–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herschel John Frederick W, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, 1845, 135, 143–145. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stokes George G, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, 1852, 142, 463–562. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Udenfriend S, Protein Sci, 1995, 4, 542–551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heim R, Cubitt AB and Tsien RY, Nature, 1995, 373, 663–664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chalfie M, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2009, 106, 10073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chalfie M, Tu Y, Euskirchen G, Ward WW and Prasher DC, Science, 1994, 263, 802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lippincott-Schwartz J, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2015, 112, 2630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tipirneni KE, Rosenthal EL, Moore LS, Haskins AD, Udayakumar N, Jani AH, Carroll WR, Morlandt AB, Bogyo M, Rao J and Warram JM, Molecular Imaging and Biology, 2017, 19, 645–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garland M, Yim Joshua J. and Bogyo M, Cell Chemical Biology, 2016, 23, 122–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Newton AD, Predina JD, Corbett CJ, Frenzel-Sulyok LG, Xia L, Petersson EJ, Tsourkas A, Nie S, Delikatny EJ and Singhal S, Journal of the American College of Surgeons, 2019, 228, 188–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shieh P, Hangauer MJ and Bertozzi CR, Journal of the American Chemical Society, 2012, 134, 17428–17431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Encell LP, Friedman Ohana R, Zimmerman K, Otto P, Vidugiris G, Wood MG, Los GV, McDougall MG, Zimprich C, Karassina N, Learish RD, Hurst R, Hartnett J, Wheeler S, Stecha P, English J, Zhao K, Mendez J, Benink HA, Murphy N, Daniels DL, Slater MR, Urh M, Darzins A, Klaubert DH, Bulleit RF and Wood KV, Curr Chem Genomics, 2012, 6, 55–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Los GV, Encell LP, McDougall MG, Hartzell DD, Karassina N, Zimprich C, Wood MG, Learish R, Ohana RF, Urh M, Simpson D, Mendez J, Zimmerman K, Otto P, Vidugiris G, Zhu J, Darzins A, Klaubert DH, Bulleit RF and Wood KV, ACS Chemical Biology, 2008, 3, 373–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Keppler A, Gendreizig S, Gronemeyer T, Pick H, Vogel H and Johnsson K, Nature Biotechnology, 2002, 21, 86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Evans MJ and Cravatt BF, Chemical Reviews, 2006, 106, 3279–3301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kenmoku S, Urano Y, Kanda K, Kojima H, Kikuchi K and Nagano T, Tetrahedron, 2004, 60, 11067–11073. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Puliti D, Warther D, Orange C, Specht A and Goeldner M, Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry, 2011, 19, 1023–1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sakabe M, Asanuma D, Kamiya M, Iwatate RJ, Hanaoka K, Terai T, Nagano T and Urano Y, Journal of the American Chemical Society, 2013, 135, 409–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jia S, Ramos-Torres KM, Kolemen S, Ackerman CM and Chang CJ, ACS Chemical Biology, 2018, 13, 1844–1852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Herman, V. E. C. BF; Lakowicz JR; Murphy DB; Spring KR; Davidson MW , Basic Concepts in Fluorescence, https://micro.magnet.fsu.edu/primer/techniques/fluorescence/fluorescenceintro.html, (accessed July 31, 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reynolds GA and Drexhage KH, Optics Communications, 1975, 13, 222–225. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Myochin T, Kiyose K, Hanaoka K, Kojima H, Terai T and Nagano T, Journal of the American Chemical Society, 2011, 133, 3401–3409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Terai T and Nagano T, Pflügers Archiv - European Journal of Physiology, 2013, 465, 347–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grimm JB, Heckman LM and Lavis LD, in Progress in Molecular Biology and Translational Science, ed. Morris MC, Academic Press, 2013, vol. 113, pp. 1–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.SciFinder; Chemical Abstracts Service, https://scifinder.cas.org, (accessed August, 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 34.(a) Jun JV, Petersson EJ and Chenoweth DM, Journal of the American Chemical Society, 2018, 140, 9486–9493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Lackner RM, Jun JV, Petersson EJ and Chenoweth DM, Methods Enzymol, 2020, 640, 309–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.(a) Ferrie JJ, Ieda N, Haney CM, Walters CR, Sungwienwong I, Yoon J and Petersson EJ, Chemical Communications, 2017, 53, 11072–11075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Jones CM, Venkatesh Y and Petersson EJ, in Methods Enzymol, ed. Chenoweth DM, Academic Press, 2020, vol. 639, pp. 37–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yuan L, Lin W, Zheng K and Zhu S, Accounts of Chemical Research, 2013, 46, 1462–1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Taniguchi M, Du H and Lindsey JS, Photochemistry and Photobiology, 2018, 94, 277–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Taniguchi M and Lindsey JS, Photochemistry and Photobiology, 2018, 94, 290–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.The Molecular Probes Handbook—A Guide to Fluorescent Probes and Labeling Technologies, https://www.thermofisher.com/us/en/home/references/molecular-probes-the-handbook.html).

- 40.Carr JA, Franke D, Caram JR, Perkinson CF, Saif M, Askoxylakis V, Datta M, Fukumura D, Jain RK, Bawendi MG and Bruns OT, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2018, 115, 4465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cosco ED, Caram JR, Bruns OT, Franke D, Day RA, Farr EP, Bawendi MG and Sletten EM, Angewandte Chemie International Edition, 2017, 56, 13126–13129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stryer L and Haugland RP, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 1967, 58, 719–726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shaya J, Fontaine-Vive F, Michel BY and Burger A, Chemistry – A European Journal, 2016, 22, 10627–10637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thirion D, Rault-Berthelot J, Vignau L and Poriel C, Organic Letters, 2011, 13, 4418–4421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu J, Diwu Z, Leung W-Y, Lu Y, Patch B and Haugland RP, Tetrahedron Letters, 2003, 44, 4355–4359. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ren Y, Fan D, Ying H and Li X, Tetrahedron Letters, 2019, 60, 1060–1065. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Grimm JB, Sung AJ, Legant WR, Hulamm P, Matlosz SM, Betzig E and Lavis LD, ACS Chemical Biology, 2013, 8, 1303–1310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hirabayashi K, Hanaoka K, Takayanagi T, Toki Y, Egawa T, Kamiya M, Komatsu T, Ueno T, Terai T, Yoshida K, Uchiyama M, Nagano T and Urano Y, Analytical Chemistry, 2015, 87, 9061–9069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Grimm JB, Tkachuk AN, Choi H, Mohar B, Falco N, Patel R, Lippincott-Schwartz J, Brown TA and Lavis LD, bioRxiv, 2019, DOI: 10.1101/2019.12.20.881227, 2019.2012.2020.881227. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Escobedo JO, Rusin O, Lim S and Strongin RM, Current Opinion in Chemical Biology, 2010, 14, 64–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liu J, Sun Y-Q, Zhang H, Shi H, Shi Y and Guo W, ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces, 2016, 8, 22953–22962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shimomura N, Egawa Y, Miki R, Fujihara T, Ishimaru Y and Seki T, Organic & Biomolecular Chemistry, 2016, 14, 10031–10036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Koide Y, Urano Y, Hanaoka K, Terai T and Nagano T, ACS Chemical Biology, 2011, 6, 600–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tao Z, Hong G, Shinji C, Chen C, Diao S, Antaris AL, Zhang B, Zou Y and Dai H, Angewandte Chemie International Edition, 2013, 52, 13002–13006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Myochin T, Hanaoka K, Iwaki S, Ueno T, Komatsu T, Terai T, Nagano T and Urano Y, Journal of the American Chemical Society, 2015, 137, 4759–4765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dickinson BC, Huynh C and Chang CJ, Journal of the American Chemical Society, 2010, 132, 5906–5915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Grimm JB, English BP, Chen J, Slaughter JP, Zhang Z, Revyakin A, Patel R, Macklin JJ, Normanno D, Singer RH, Lionnet T and Lavis LD, Nature Methods, 2015, 12, 244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Michie MS, Götz R, Franke C, Bowler M, Kumari N, Magidson V, Levitus M, Loncarek J, Sauer M and Schnermann MJ, Journal of the American Chemical Society, 2017, 139, 12406–12409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Renikuntla BR, Rose HC, Eldo J, Waggoner AS and Armitage BA, Organic Letters, 2004, 6, 909–912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang L, Tran M, D’Este E, Roberti J, Koch B, Xue L and Johnsson K, Nature Chemistry, 2020, 12, 165–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Liu X, Xu Z and Cole JM, The Journal of Physical Chemistry C, 2013, 117, 16584–16595. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Urano Y, Kamiya M, Kanda K, Ueno T, Hirose K and Nagano T, Journal of the American Chemical Society, 2005, 127, 4888–4894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Miura T, Urano Y, Tanaka K, Nagano T, Ohkubo K and Fukuzumi S, Journal of the American Chemical Society, 2003, 125, 8666–8671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gabe Y, Urano Y, Kikuchi K, Kojima H and Nagano T, Journal of the American Chemical Society, 2004, 126, 3357–3367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tanaka K, Miura T, Umezawa N, Urano Y, Kikuchi K, Higuchi T and Nagano T, Journal of the American Chemical Society, 2001, 123, 2530–2536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ueno T, Urano Y, Setsukinai K.-i., Takakusa H, Kojima H, Kikuchi K, Ohkubo K, Fukuzumi S and Nagano T, Journal of the American Chemical Society, 2004, 126, 14079–14085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Terai T and Nagano T, Current Opinion in Chemical Biology, 2008, 12, 515–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Grimm JB, Muthusamy AK, Liang Y, Brown TA, Lemon WC, Patel R, Lu R, Macklin JJ, Keller PJ, Ji N and Lavis LD, Nature Methods, 2017, 14, 987–994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zheng Q, Ayala AX, Chung I, Weigel AV, Ranjan A, Falco N, Grimm JB, Tkachuk AN, Wu C, Lippincott-Schwartz J, Singer RH and Lavis LD, ACS Central Science, 2019, 5, 1602–1613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bassolino G, Nançoz C, Thiel Z, Bois E, Vauthey E and Rivera-Fuentes P, Chem Sci, 2018, 9, 387–391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rotman B and Papermaster BW, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 1966, 55, 134–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rotman B, Zderic JA and Edelstein M, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 1963, 50, 1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Thompson VF, Saldaña S, Cong J and Goll DE, Analytical Biochemistry, 2000, 279, 170–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cabré EJ, Martínez-Calle M, Prieto M, Fedorov A, Olmeda B, Loura LMS and Pérez-Gil J, Journal of Biological Chemistry, 2018, 293, 9399–9411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Aron AT, Ramos-Torres KM, Cotruvo JA and Chang CJ, Accounts of Chemical Research, 2015, 48, 2434–2442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bruemmer KJ, Crossley SWM and Chang CJ, Angewandte Chemie International Edition, n/a. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chung CY-S, Posimo JM, Lee S, Tsang T, Davis JM, Brady DC and Chang CJ, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2019, 116, 18285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Aron AT, Loehr MO, Bogena J and Chang CJ, Journal of the American Chemical Society, 2016, 138, 14338–14346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Jiang N, Li H and Sun H, Frontiers in Chemistry, 2019, 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kim SJ and Kool ET, Journal of the American Chemical Society, 2006, 128, 6164–6171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Griffin BA, Adams SR and Tsien RY, Science, 1998, 281, 269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Scheck RA and Schepartz A, Accounts of Chemical Research, 2011, 44, 654–665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Jradi FM and Lavis LD, ACS Chemical Biology, 2019, 14, 1077–1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.(a) Tran MN and Chenoweth DM, Angew Chem Int Ed Engl, 2015, 54, 6442–6446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Lackner RM, Johnny CL and Chenoweth DM, in Methods Enzymol, ed. Chenoweth DM, Academic Press, 2020, vol. 639, pp. 379–388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Jun JV, Haney CM, Karpowicz RJ, Giannakoulias S, Lee VMY, Petersson EJ and Chenoweth DM, Journal of the American Chemical Society, 2019, 141, 1893–1897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Chozinski TJ, Gagnon LA and Vaughan JC, FEBS Letters, 2014, 588, 3603–3612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.van de Linde S, Krstić I, Prisner T, Doose S, Heilemann M and Sauer M, Photochemical & Photobiological Sciences, 2011, 10, 499–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Maurel D, Banala S, Laroche T and Johnsson K, ACS Chemical Biology, 2010, 5, 507–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Tran MN, Rarig R-AF and Chenoweth DM, Chem Sci, 2015, 6, 4508–4512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Walko M and Feringa BL, Chemical Communications, 2007, DOI: 10.1039/B702264F, 1745–1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kim E, Lee Y, Lee S and Park SB, Accounts of Chemical Research, 2015, 48, 538–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Sungwienwong I, Hostetler ZM, Blizzard RJ, Porter JJ, Driggers CM, Mbengi LZ, Villegas JA, Speight LC, Saven JG, Perona JJ, Kohli RM, Mehl RA and Petersson EJ, Organic & Biomolecular Chemistry, 2017, 15, 3603–3610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Batjargal S, Walters CR and Petersson EJ, Journal of the American Chemical Society, 2015, 137, 1734–1737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Padmanarayana M, Hams N, Speight LC, Petersson EJ, Mehl RA and Johnson CP, Biochemistry, 2014, 53, 5023–5033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Speight LC, Muthusamy AK, Goldberg JM, Warner JB, Wissner RF, Willi TS, Woodman BF, Mehl RA and Petersson EJ, Journal of the American Chemical Society, 2013, 135, 18806–18814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Sungwienwong I, Ferrie JJ, Jun JV, Liu C, Barrett TM, Hostetler ZM, Ieda N, Hendricks A, Muthusamy AK, Kohli RM, Chenoweth DM, Petersson GA and Petersson EJ, Journal of Physical Organic Chemistry, 2018, 31, e3813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Miller EW, Lin JY, Frady EP, Steinbach PA, Kristan WB and Tsien RY, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2012, 109, 2114–2119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ortiz G, Liu P, Naing SHH, Muller VR and Miller EW, Journal of the American Chemical Society, 2019, 141, 6631–6638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Liu P, Grenier V, Hong W, Muller VR and Miller EW, Journal of the American Chemical Society, 2017, 139, 17334–17340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Boggess SC, Gandhi SS, Siemons BA, Huebsch N, Healy KE and Miller EW, ACS Chemical Biology, 2019, 14, 390–396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Lee J-S, Kim YK, Vendrell M and Chang Y-T, Molecular BioSystems, 2009, 5, 411–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.