Abstract

Family caregiver engagement in clinical encounters can promote relationship-centered care and optimize outcomes for people with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (ADRD). Little is known, however, about effective ways for health care providers to engage family caregivers in clinical appointments to provide the highest quality care. We describe what caregivers of people with ADRD and people with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) consider potential best practices for engaging caregivers as partners in clinical appointments. Seven online focus groups were convened. Three groups included spousal caregivers (n = 42), three included non-spousal caregivers (n = 36), and one included people with MCI (n = 15). Seven potential best practices were identified, including the following: “acknowledge caregivers’ role and assess unmet needs and capacity to care” and “communicate directly with person with ADRD yet provide opportunities for caregivers to have separate interactions with providers.” Participants outlined concrete steps for providers and health care systems to improve care delivery quality for people with ADRD.

Keywords: online focus groups, relationship-centered care, patient-centered care, best practices, Alzheimer’s disease

Family engagement in clinical encounters can promote effective communication, patient-centered care, and have meaningful impact on patient health and well-being (Wolff, 2012; Wolff et al., 2017). Family caregivers, however, are often seen by health care providers as ancillary agents to patients instead of partners in care (Boehmer et al., 2014). Training programs, decision guides, and toolkits have been developed to help clinicians and patients learn how to communicate and share in decisions at different points in the care continuum (Burns, Bellows, Eigenseher, & Gallivan, 2014; Coulter & Ellins, 2007; Elwyn et al., 2005; Stacey et al., 2008), but less has been done to identify strategies for effectively integrating family caregivers into care (Borson & Chodosh, 2014; Miller, Whitlatch, & Lyons, 2016; Wolff & Roter, 2011). Shared decision-making research has examined patient/caregiver dyads in the clinical encounter (Lyons & Lee, 2018; Miller et al., 2016; Northouse, Williams, Given, & Mccorkle, 2012), but less is known about caregivers’ expectations about their engagement in clinical care and about care recipients’ expectations of caregiver engagement in clinical care.

Family members caring for people with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (ADRD; henceforth, “caregiver,” defined as someone who routinely provides direct care or support to a relative or close friend) are responsible for a significant share of care including adherence to medication regimens, support with complex behaviors and memory impairment, avoidance of unnecessary health care utilization, and mitigation of risks associated with ADRD (Speice et al., 2000; Wittenberg-Lyles, Oliver, Demiris, Burt, & Regehr, 2010; Wolff, 2012; Wolff et al., 2017; Wolff & Roter, 2011). Integrating caregivers into health care appointments is beneficial in earlier stages of ADRD to provide clinical support for sustaining autonomy, but becomes imperative when a person with ADRD lacks capacity to reliably articulate personal health information, independently make treatment decisions, or communicate preferences (Barello, Savarese, & Graffigna, 2015). Evidence-based clinical guidelines for managing care for people with ADRD encourage caregiver engagement (Borson & Chodosh, 2014; Hogan et al., 2008; Sadak, Wright, & Borson, 2018) and ways to effectively manage communication among providers, people with ADRD and their caregivers have been studied (Adams & Gardiner, 2005; Karnieli-Miller, Werner, Neufeld-Kroszynski, & Eidelman, 2012). Studies, however, are typically designed to understand providers’ perspectives of how to engage caregivers and people with ADRD. The expectations of caregivers and people with ADRD have been overlooked, but are critical for effective implementation of any intervention to address this gap. This study aims to understand what potential best practices are for including caregivers of people with ADRD into clinical appointments from the perspective of these two stakeholder groups.

Method

We convened seven asynchronous online focus groups with the principal investigator, a health services researcher with qualitative research training and experience as the group moderator. Caregivers’ experiences, stressors, and burdens vary by the caregiver’s relationship to the person with ADRD (e.g., spouse, adult child, and other family or friend; Conde-Sala, Garre-Olmo, Turró-Garriga, Vilalta-Franch, & López-Pousa, 2010), and therefore, we conducted three focus groups with spousal caregivers and three with non-spousal caregivers (e.g., children, friend, siblings). The remaining focus group included people who self-identified as having mild cognitive impairment (MCI).

Online focus groups are a convenient, cost-effective research method, providing flexibility for participants to participate remotely at times convenient for them. Although online focus groups inhibit the observation of group interactions and non-verbal cues and may bias participation toward people with better technological skills, research shows they capture a more geographically diverse group of participants (Rupert, Poehlman, Hayes, Ray, & Moultrie, 2017) and, because a moderator is not physically present, some studies suggest a decrease social desirability bias (Duffy, Smith, Terhanian, & Bremer, 2005; Skelton et al., 2018).

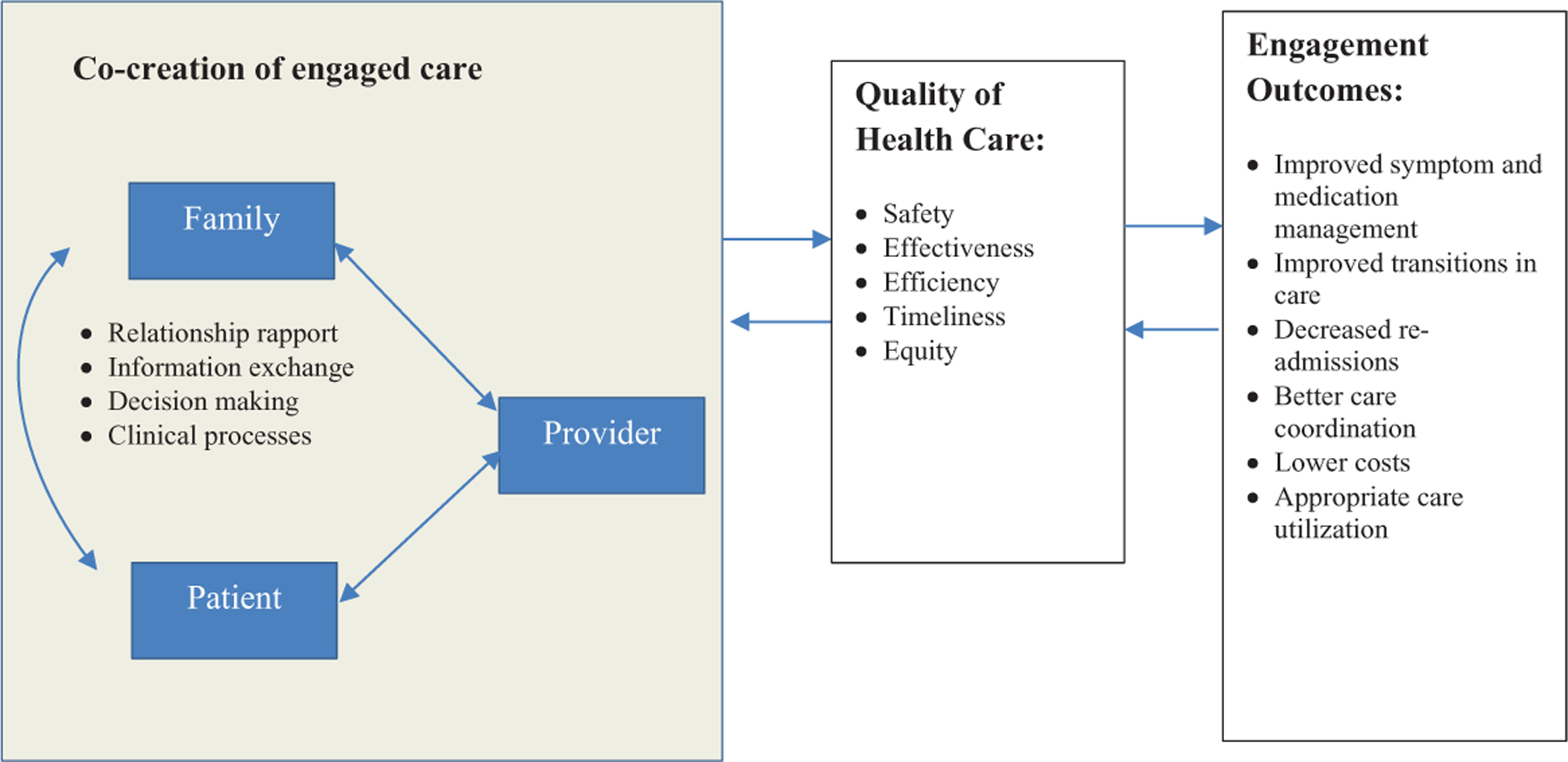

To inform the moderator guide, we draw from models developed from literature reviews on engagement of dyads and families in health care (Frampton et al., 2017; Lyons & Lee, 2018; Northouse et al., 2012; Wolff & Roter, 2011). Our model (Figure 1) describes a recursive process by which intentional engagement of families in face-to-face clinical encounters with patients and providers could influence health care practice quality, clinical interaction, and outcomes. Relationship rapport, information exchange, and decision making, interpersonal processes highlighted in the review of quantitative studies by Wolff et al., are broad and general constructs, providing an ideal starting point for focus-group questions. We expected that people with self-identified MCI and caregivers would provide qualitative definitions for these constructs, identify other constructs to consider, and offer ideas on how to implement them in real-world clinical practices.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of factors and processes of caregiver engagement in clinical appointments.

The focus group platform we used assigned a pseudonym to each participant so that researchers could not identify participants. No protected health information was requested during the focus group. For these reasons, the institutional review board (IRB), after reviewing the study protocol, deemed the research exempt from the requirement for IRB approval.

Participants

We used convenience sampling to recruit participants. Participants were recruited in collaboration with UsAgainstAlzheimer’s, an advocacy group that aims to mobilize participation in research on effective treatments and improvements in care quality for persons with ADRD (usagainstalzheimers.org). UsAgainstAlzheimer’s administers the A-LIST, a unique online network of over 6,000 individuals who self-identify either as someone at risk for or with MCI or ADRD, a current or former caregiver for someone with ADRD, or someone interested in brain health (alist4research.org).

A-LIST administrators sent an email outlining study details to people on the A-LIST. Emails explicitly asked for caregivers of people with ADRD or people with MCI and included a hyperlink to additional information about the study. Those interested were given an option to share their name, email address, role (caregiver or person with MCI), and phone number for the study’s research team to contact them by telephone. Three attempts were made at different times of day to reach interested participants by phone. Inclusion criteria, assessed by phone during recruitment, included participants who were 18 years or older, able to read and understand English, enrolled in the A-LIST, had access to and ability to use a computer, and availability to participate over the 9-day study period. Caregiver participants were required to either currently provide or have previously provided care to someone with ADRD. For people reporting to have MCI, we did not verify a diagnosis, but instead relied on a self-report of their condition. We did, however, require that they would be able to participate independently in the online focus group at least once a day for 9 days.

Procedures

We used self-reported demographic information to determine group assignment (spousal caregiver, non-spousal caregiver, person with MCI). We then sent participants an email with a hyperlink to the study’s online, subscription-based focus-group platform. After registering for the platform, participants were automatically assigned an alias to assure their identity was not disclosed to others or the study team. Two team members were group “observers.” They followed focus-group threads and suggested additional probes to the moderator.

Three researchers developed the moderator guide with input from UsAgainstAlzheimer’s. Questions focused on caregivers’ perceptions of their role, experiences working with clinical teams, expectations about the clinical teams’ engagement, and strategies for improving clinical care and outcomes (Table 1). The principal investigator posted a new question on the focus-group platform every other day for 9 days to provide adequate time for discussion. Participants logged onto the platform and were able to respond any time after the question was posted. The principal investigator reviewed postings each day, allowing for an initial preview of the data, and added probes and follow-up questions when appropriate. Participants were encouraged to respond to each other’s posts and to post as often as they wished about the same question. Data were downloaded and stored on a secure server for analysis.

Table 1.

Focus-Group Questions for Family Caregivers and People With Mild Cognitive Impairment.

| Examples of focus-group questions for caregivers | Examples of focus-group questions for people with mild cognitive impairment |

|---|---|

| 1. What kinds of things do you wish or want your loved one’s health care provider to know about you, your health, or the care you provide? | 1. Families often provide care and accompany their loved ones to appointments. They often can provide a different perspective about their loved one’s health. What do you think about health care providers (such as doctors, nurses, social workers, and psychologists) getting your caregiver’s perspective on your health? |

| 2. What do you think your role is on your loved one’s health care team? What do you think your loved one’s doctors and nurses think your role is? | 2. How involved would you like your caregiver to be in the health care decisions for you right now? In the long term? |

| 3. How important is it for your loved one’s health care providers to know about your health and well-being? | 3. How important is it for your health care providers to know about the health and well-being of your caregiver? |

| 4. How involved would you like to be in the health care decisions for your loved one? | 4. What are some things that doctors and nurses have said or done that have helped engage your caregiver to the degree you think is most appropriate? What are some of the things that have been unhelpful? |

| 5. What are some things that doctors and nurses have said or done that have helped you as a caregiver? What are some of the things that have been unhelpful? |

Analysis

We used a thematic content analysis to analyze study data (Krueger & Casey, 2014). We read all transcripts multiple times to achieve immersion in the data. We then read the transcripts word-for-word to derive themes capturing key thoughts or concepts from the data and organized themes into codes. We developed a code book based on the initial coding schemes and definitions for each code. To structure the data, we applied the themes back to the transcripts using line-by-line inductive coding (Bradley, Curry, & Devers, 2007; Patton, 2002).

Our team also included two trained qualitative PhD researchers with expertise in gerontology and developmental psychology. The three researchers coded data to assure that open coding was consistent and reproducible. Coding decisions were documented to provide a clear audit trail on the origin of the codes. We triangulated data by comparing and contrasting the data from people living with MCI and spousal and non-spousal caregivers. Approximately 1 year after the focus groups, when analysis was complete, we developed a summary of the findings and shared it with the original focus-group participants (i.e., member checking) by re-opening the online focus-group platform, asking participants how the summative findings matched their experiences, and whether there were obvious gaps that should have been included.

Results

Participants

A total of 200 people expressed interest in participating in the focus groups. Study staff attempted to contact all 200. Of those, 78 caregivers agreed to participate and 15 people with MCI agreed to participate (n = 93, response rate = 46.5%). Of the 78 caregivers who participated, 42 were spouses and 36 were non-spouses. Ninety-one could not be reached after three attempts by phone at different times of day. Of the remaining 109 interested participants, nine were contacted, but ineligible (e.g., did not have access to a computer) and nine were contacted, but were not available to respond during the timeframe the focus group was open.

Demographics

Participants represented 28 states from each region in the United States, the District of Columbia, and three Canadian provinces. As shown in Table 2, 88% of caregivers were women and 53% of those with MCI were men. Nearly half of caregivers were retired (49%) and all with MCI identified as retired, not working, or disabled. Most caregivers were married (73%), White (95%), and had high at least a college education (77%). The average age for caregivers was 64 years and for people with MCI, 67 years.

Table 2.

Self-Reported Demographics of Focus-Group Participants.

| Family caregiver (n = 78) | Person with dementia (n = 15) | |

|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | n (%) | n (%) |

| Female | 69 (88) | 8 (53) |

| Employment statusa | ||

| Employed full-time | 20 (26) | 0 (0) |

| Employed part-time | 11 (14) | 0 (0) |

| Disabled/unemployed | 8 (10) | 5 (33) |

| Retired | 38 (49) | 10 (66) |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 60 (77) | 12 (80) |

| Divorced/separated | 9 (12) | 0 (0) |

| Single | 5 (6) | 1 (7) |

| Widowed | 4 (5) | 2 (13) |

| Educational attainment | ||

| Some high school or diploma/GED | 3 (4) | 3 (20) |

| Some college or associate’s degree | 15 (19) | 5 (33) |

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 60 (77) | 7 (47) |

| Race | ||

| White | 74 (95) | 15 (100) |

| Other | 4 (5) | 0 |

| Age at interview (years) | ||

| M ± SD (range) | 63.9 ±10.1 (28–82) | 67.3 ±10.2 (56–88) |

| Self-reported healtha | ||

| Excellent | 19 (24) | 2 (13) |

| Very good | 26 (33) | 4 (26) |

| Good | 24 (31) | 6 (40) |

| Fair | 7 (9) | 3 (20) |

| Poor | 1 (1) | 0 (0) |

Missing = 1.

Potential Best Practices

Emergent themes included relationship rapport, information exchange, and decision making and were seen as the core elements of co-creating reciprocal care processes that engage caregivers, people with ADRD, and providers to improve outcomes. Data included details about what these domains mean to participants and how best to achieve them in clinical practice, including structural barriers that need to be addressed. Illustrative quotes from the focus groups are included, with additional quotes in Table 3.

Table 3.

Additional Illustrative Quotes by Potential Best Practice and Theme.

| Theme | Potential best practice | Quote |

|---|---|---|

| Relationship rapport | Build trust with caregivers and people with dementia | “I think my doctor’s statement was that he would work with me until I could not remember and then he would work for me.” (Person with MCI, #8) |

| Respectfully acknowledge caregiver role and assess caregiver’s unmet needs and capacity to care | “My husband’s doctors and nurses should absolutely be aware, and acknowledge, that they are treating a family, although my spouse is the official patient. Most often, my presence in the exam room is tolerated but I’m not acknowledged as my spouse’s primary caregiver and advocate. How should they do this? Acknowledge that they know (most don’t) that my spouse and I are a team, and that I am as important in his care as the doctor is.” (Spouse, Group 1, #3) | |

| Information exchange | Communicate directly with person with ADRD and provide opportunities for caregivers to have separate interactions with the providers | “As long as I am still competent enough to speak for myself and understand what is being said to me, I would prefer to do all the talking … I do strongly object to a health provider speaking only to the caregiver, treating the person with dementia as if he or she were not present … health providers should speak first and foremost TO us, explain things TO us, ask questions OF us.” (Person with MCI, #6) |

| “I don’t want to be questioned about his status in front of him. I see no point in that, and sometimes I do not feel comfortable being honest about what I see happening. It would be different, perhaps, if the medical person asked his permission for me to report on what I see. But sometimes I think it just makes him feel more depressed and I don’t find that helpful.” (Spouse, Group 3, #8) | ||

| “My husband is now in the severe category; however, he is very aware of his inabilities and depressed when he can’t answer, BUT more upset when he’s ignored. No matter what stage of Alzheimer’s the patient is in, questions dealing with their care should be addressed to them first and then when there is no answer, the eye contact goes to the caregiver.” (Spouse, Group 1, #10) | ||

| Improve provider knowledge of the disease and training on how to communicate knowledge | “NOT helpful: local primary care provider who had to be pushed to make requested referrals … Also unhelpful was Mom’s primary MD who initially delayed evaluation by recommending a ‘medical food’ supplement (for which Medicare was billed) even after mental status exam was clearly abnormal … Thankful that both my sister and I are nurses—and thus able to advocate for our Mom from a place of some level of expertise or she would have gotten very little from the local medical community.” (Non-spouse, Group 2, #2) | |

| “I’ve learned to say, ‘I don’t expect you to know this because no one really does. Lewy Body information is still evolving and we are all learning together.’ The most important thing is that they know I have researched this and not by just reading something on the Internet.” (Spouse, Group 1, #1) | ||

| Screen and assess caregiver needs and provide information about helpful resources to contact for additional support | “When I took my husband to his doctor yesterday, the second of three different appointments in two days, I thought how easy it could be for them to appear concerned. If they asked caregivers to rate their stress on a 1–10 scale, which they could do by handing them a piece of paper when they walk in, they’d know what’s going on for the caregiver. Depending on what the caregiver self-reports, they could minimally give them information that might be useful. Really, a list of free downloadable apps for meditation or mindfulness, a list of relaxing music, a list of free resources in the community and how to access them would all be helpful. The only thing that would not be helpful is telling a caregiver that they need to take care of themselves.” (Spouse, Group 2, # 9) | |

| Coordinate care between members of the clinical team | “…my loved one had his primary care provider as well as numerous specialty care providers and it became difficult for me to coordinate care and communication across so many providers.” (Spouse, Group 3, #4) | |

| Decision making | Train providers in shared decision making and how to resolve conflicts with caregivers and people with ADRD | “With medical professionals it is harder; they often pay only lip service to us as family members. Medication changes are big. Doctors want to change them even when things are going well. For my FIL [father-in-law] we are being very vigilant as he is very stable with no hallucinations now and only a few delusions. We want to maintain his medications as they are until he needs a change. We find that we must be very strong in this or there will be a change made without us knowing. It seemed they could not ‘hear’ me and my husband when we said not to change his medications.” (Daughter-in-law, Group 1, #4) |

| “If it’s an important meeting with my doctors, they will usually ask me if I can bring someone and if they can speak with them, my friends and family are aware that I want and will make my own decisions for as long as possible and things are in place for when I no longer can, they do provide important information and can remind of things that I may forget during the doctor’s visit because it is harder and longer to process information. Their perspective sometimes is shocking to me, but I am aware it is essential that they can relay information because often I think I’m managing fine when I am having new struggles. It is a fine line between keeping your privacy and being willing to share, sometimes I struggle with the sharing part as it’s so personal.” (Person with MCI, #3) |

Note. MCI = mild cognitive impairment; ADRD = Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias; FIL = father-in-law.

Relationship rapport.

Caregivers identified themselves as critical members of the clinical care team. They described themselves as advocates, navigators, liaisons, and translators, all roles for which a central responsibility is to interact routinely and effectively with clinical care teams. Non-spousal caregivers, 83% of whom were children of the person with ADRD, described challenges in building rapport with clinicians, including how providers were often wary of their abilities, motivations, and involvement with the person with ADRD.

Potential best practice: Build trust with caregivers and people with dementia.

Participants reported that part of the provider’s role in delivering quality care was to build rapport with caregivers and people with ADRD. Building trust through honest and compassionate interactions, respecting the history and legacy of the person with ADRD and their relationship with the caregiver, and recognition of the burden of living with or living with someone who has ADRD were important for building rapport. Skilled and trusted providers were identified as those who do not use jargon, are transparent in their communication by openly and honestly discussing challenging subjects, and effectively managing conflicting reports between people with ADRD and caregivers:

When my mother first was diagnosed, her long-term primary care provider would not listen to me when I tried to explain what happens at home. She presented so well in the Dr.’s office he thought I was “difficult.” I want healthcare providers to know I am watching carefully and have her safety in my mind … I was looking for a care partner but instead he fought me every step … We see what is happening on a day to day basis—they should be our partners not just be “in charge.”

(Adult daughter, Group 1, #4)

Potential best practice: Respectfully acknowledge caregiver role and assess caregiver’s unmet needs and capacity to care.

There was strong support for a “family-centered” approach to care, where the caregiver’s well-being is considered an important part of the person with ADRD’s care. Although there was no consensus on the best approach, caregivers suggested providers use short surveys, checklists, or open-ended questions either prior to appointments, in the waiting room, or during a patient appointment to assess caregiver burden and capacity to provide care:

I think healthcare providers should take a holistic approach to this diagnosis. Not only treat the patient but also the main caregiver and family. In our family, it is truly a family diagnosis.

(Adult daughter, Group 3, #8)

Information exchange.

Caregivers described themselves as having valuable information about the person with ADRD. Caregivers bring knowledge of the person before ADRD began, daily habits and routines, personality, other health issues, and also hold a unique understanding of the person with ADRD’s preferences and values. Focus groups revealed that this information is not always sought, valued, or exchanged between caregivers and the clinical team.

Potential best practice: Communicate directly with person with ADRD and provide opportunities for caregivers to have separate interactions with the providers.

Participants were unequivocal in their belief that health care providers need to direct their communication to the person with ADRD, even when it appears that the person may not understand or remember the information.

Despite this firm belief, caregivers also discussed how people with ADRD often are not reliable reporters of personal behaviors or changes in cognition. Thus, it is critical that caregiver reports and insights are respected and considered by providers. Suggestions for integrating caregivers included having a clinical process in place, either a separate meeting with clinical staff or electronic communication prior to an encounter, allowing a person with ADRD to maintain their dignity in the encounter, but assuring providers have full and accurate information:

I would like my husband’s healthcare providers to know I was not comfortable talking about my husband’s health in front of him. I wanted and needed to answer the questions they posed in a separate room. My husband was proud and determined and would get angry when I spoke about him in terms of Alzheimer’s.

(Spouse, Group 1, #2)

Even with the best intentions, however, this potential practice could be misconstrued or seen as undermining by the person with ADRD:

I welcome the perspective that my caregiver can give to my healthcare team for the most part but sometimes (especially with my social worker), I wish they wouldn’t share so many secrets.

(Person with MCI, #13)

Potential best practice: Improve provider knowledge of the disease and training on how to communicate knowledge.

Participants discussed the need for training providers about ADRD because health care providers often do not have a thorough understanding of different types of dementia, effective treatments, or what behaviors to expect in the short- and long term. They discussed the need for providers to set expectations for caregivers and people with ADRD about how changes in cognition will begin a shift in the autonomy and safety of the person with ADRD to the caregiver and how both roles will change over time:

… it behooves every clinic and hospital to assure their staff/ personnel know how to make sure that a patient with Alz [sic] understands questions. In order to do that, the staff needs to learn how to listen and speak to an Alz [sic] patient … . Training would be valuable. If not available, a check-list would be a good start, including what to expect from an Alz [sic] patient, i.e. asking questions over & over … .

(Person with MCI, #2)

Potential best practice: Screen and assess caregiver needs and provide information about helpful resources to contact for additional support.

Participants agreed that provider knowledge about caregiver health and capacity was important, but were not unified about the degree to which health care providers should assess caregiver well-being, capacity to provide care, or willingness to provide care. Some participants suggested that simple acknowledgment of the burden of care would be enough. Others described that, because the caregiver was an essential part of the care team, any compromise of the caregiver’s health and well-being should be understood by the provider. Some caregivers were well aware of clinical constraints on providers diverting attention away from patients and commented that although an assessment of caregiver burden and capacity might be considered an ideal practice, with provider time constraints, privacy laws and inability for clinics to bill for time spent with caregivers, any assessment of caregiver health or well-being is not currently feasible. Caregivers were unified, however, on the importance of providers being knowledgeable about and able to refer them to community and social service resources that may benefit caregivers in their caregiving role:

I think it is extremely important that the loved one’s doctor know about the caregiver’s health because it directly impacts their ability to provide care … this includes physical, mental, emotional and maybe spiritual health which some doctors may not think to ask about. Doctors need to be aware of resources for the caregiver, such as day care and respite programs.

(Spouse, Group 1, #13)

Potential best practice: Coordinate care between members of the clinical team.

Caregivers identified one of their roles as navigators, or someone who takes action to facilitate a patient’s medical care. They discussed the boundaries of that role, and that the exchange of information between different health care providers should be coordinated by the clinical team, not by the caregiver:

… I really wish my husband’s providers would talk to each other instead of asking me, a non-medical person, to relay information back and forth when I don’t really understand either the information or the impact of it.

(Spouse, Group 2, #9)

Decision making.

With progressive declines expected in the cognition of people with ADRD, participants understood that over time caregivers will take on more responsibility for decision making from the person with ADRD. Both discussed how shared decision-making principles should be followed throughout the trajectory of care.

Potential best practice: Train providers in shared decision making and how to resolve conflicts with caregivers and people with ADRD.

Results indicate that participants expect providers to help navigate shared decision-making processes. People with MCI emphasized their desire for autonomy in decision making and also acknowledged that autonomy is relational, and that information needed for decisions is shared not just between clinician and patient but among multiple people including caregivers.

Related to discussions about personal and relational autonomy were conversations about how shared decisions should take into consideration caregiver capacity and values, not as a proxy to the person with ADRD but as an important contributor to the care of the person with ADRD. Setting a pattern of shared decision making early in the disease process can familiarize the provider and caregiver in negotiating care once the person no longer has capacity to make decisions.

Non-spousal caregivers commonly cited examples of how clinical teams would change medication or care practices without consulting them. Because non-spousal caregivers often did not live with the care recipient, providers did not always value the significance of non-spousal caregiver’s role and how changes in treatment without their knowledge made it difficult for them to stay apprised of current medications and presented challenges for monitoring side-effects and medication adherence:

Caregivers often have numerous responsibilities and limited time and flexibility. While I’m sure providers are somewhat aware of this, it is likely not the first thing on their minds when they prescribe complex care routines or medications … Providers need to be mindful of not only the best treatment for patients, but the best treatment that can realistically be properly administered to the patient by the caregiver in light of extenuating circumstances.

(Granddaughter, Group 1, #2)

Discussion

This study aimed to understand what people with MCI and caregivers of people with ADRD consider ideal practices for health care providers to integrate caregivers into medical appointments and health care teams. Research has examined similar questions, but primarily through the lens of the health care provider (Groen van de Ven et al., 2017; Mitnick, Leffler, & Hood, 2010; Yaffe, Orzeck, & Barylak, 2008). A smaller number of studies have explored caregiver engagement in the encounter and focused on caregiver perceptions of their role in the encounter (Borson & Chodosh, 2014; Sadak et al., 2018). Emerging theory on illness management suggests that a clinical focus on the patient/caregiver dyad helps optimize the inter-related and reciprocal issues experienced by patients and their caregivers (Lyons & Lee, 2018; Northouse et al., 2012). Our initial conceptual model and results are consistent with these studies, but extend the work with specific suggestions for potential clinical best practices ranging from small-scale, individual practices (e.g., Build trust with caregivers and people with dementia) to larger system-level practices (e.g., Screen and assess caregiver needs and provide information about helpful resources to contact for additional support).

Results emphasized the centrality of relationships between and among the clinical team, caregivers, and people with ADRD. Participants had expectations of care being “relationship-centered.” This meant in the delivery of care, not only was the patient–provider relationship considered but also the caregiver–provider relationships and relationships among clinical team members. The potential best practices identified by participants were consistent with the four principles associated with relationship-centered care: (a) relationships in health care ought to include the personhood of all participants; (b) affect and emotion are important components of care relationships; (c) all health care relationships occur in the context of reciprocal influence; and (d) the formation and maintenance of genuine relationships in health care is morally valuable (Beach, Inui, & Relationship-Centered Care Research Network, 2006).

Participants discussed the deep knowledge caregivers have about their care recipients’ behaviors and ways they help manage daily and social activities. Caregivers saw themselves as valuable allies to providers, people who, with support and resources, can effectively co-manage the care recipients’ health alongside the providers or clinical teams. Consistent with research on shared decision making for people with ADRD, both people with MCI and caregivers discussed their desire for a person with ADRD to be engaged in decision making as long as possible (Miller et al., 2016). Values clarification is a key component in shared decision making and caregivers advocated for their values and values of people with ADRD, be considered.

Implications

Participants provided ideas for practices ranging from small-scale practice changes that can be implemented by a single provider to large-scale institutional practice changes, such as restructuring clinical encounters. Evaluation of the Support, Health, Activities, Resources, and Education (SHARE) program suggests that both caregivers and persons with early-stage dementia can effectively and meaningfully participate in interventions that include both dyadic and individual sessions (Whitlatch et al., 2019). Like the sessions in SHARE, separate clinical encounters would allow institutional practice changes, such as restructuring clinical encounters, to allow for separate, yet coordinated, interactions for patients and accompanying caregivers. Separate encounters would allow clinical teams to collect patient information in a respectful way while maintaining patient autonomy. The benefits of including caregivers or companions in appointments improve communication and autonomy-related behaviors (Groen van de Ven et al., 2017; Laidsaar-Powell et al., 2013; Schilling et al., 2002), but far less research examines the impact of separate appointments (Swetenham, Tieman, Butow, & Currow, 2015; Swetenham, Tieman, & Currow, 2014).

Participants recommend providers receive training on (a) the prognosis and disease course of different types of dementia; (b) effective pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions; and (c) caregiving resources. The majority of participants express a desire for the far more simple skill of compassionate interpersonal communication from providers. Advances in medical education afford new opportunities for provider training in compassionate communication with caregivers. With the Association of American Medical Colleges embracing a new “kindness curriculum,” several medical schools now provide instruction in the neuroscience of empathy, teaching practical techniques for improving rapport and using virtual reality to engage medical residents in practicing empathetic communication (Howard, 2018; Louie et al., 2018; Zielke et al., 2017).

Research has reported that providers, too, feel under-trained in diagnosis and care management and also perceive assessing and addressing caregiver needs out of their purview (Yaffe et al., 2008). Creative and efficient solutions need to be developed to cross-train interdisciplinary teams with expertise in different aspects of the care experience. Drawing from comprehensive frameworks of integrated care, such as the Assessing Caregivers for Team Interventions (ACT) used in hospice care (Demiris, Oliver, & Wittenberg-Lyles, 2009), may prove especially useful.

For the large-scale practice changes to become reality, alternative payment mechanisms and performance standards are required. Especially needed are reimbursement models that compensate providers for interactions with caregivers and performance standards that hold providers accountable for caregiver support. Although important features of Medicare and Medicaid payment policies, such as cost, coverage, and eligibility, are influenced by political factors and vary considerably from state to state, several advances hold promise for expansion, particularly chronic care management and transitional care service codes that allow providers to bill for non-face-to-face discussions with caregivers about the beneficiary’s care (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid, 2015; Medicare Payment Advisory Commission [MedPAC], 2015). To the extent that legislative progress can be made toward implementing scalable and sustainable reimbursement models, aligning this study’s potential best practices with relevant, progressive payment reforms will be crucial to ensuring future health care delivery innovations fully embrace relationship-centered care.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, we recruited participants for only one focus group of people with MCI. Of those, all but one had an actively involved caregiver. Our results may be more weighted toward perceptions of caregivers than people living with MCI or ADRD with or without a caregiver. We did, however, compare data across all focus groups and found similar responses and expectations. Second, our sample was a convenience sample. Participants were recruited from an Alzheimer’s disease advocacy group and because of their active engagement in advocacy to improve care for people with ADRD, they may not represent all people with ADRD or their caregivers and, by virtue of their participating in the study, may have greater health and technological literacy than other caregivers of people with ADRD. Third, the sample captured different caregiving experiences (e.g., caregivers who were spouses, adult children, grandchildren). Despite this diversity, few were either people newly diagnosed or caregivers of people newly diagnosed with ADRD. Finally, the use of online focus groups may have limited interaction between participants who often enrich in-person focus groups. Research shows, however, that online focus groups foster more forthright and robust interactions and are less prone to social desirability bias, in part because the anonymity allows participants to be frank (Reisner et al., 2017). Online focus groups may also benefit those who struggle with the pace of in-person focus groups by allowing them to follow the conversation by reading the threads in their own time.

Conclusion

Our study gives voice to people with MCI and their caregivers and identifies potential best practices to integrate caregivers of people with ADRD into clinical appointments through individual and systemic adoption. These practices are rarely assessed but critical for developing models of care that meet the needs of people with ADRD and their caregivers, who remain the cornerstones to the health and well-being of this growing population. This research offers guidance for small-and large-scale changes that providers and health systems with vested interests in better serving the needs of these individuals could implement. Measuring the efficacy and effectiveness of these practices and outcomes for people with ADRD and their caregivers is an important next step toward validating these approaches.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the participants who gave their time and shared their experiences for this research and Ashley Baker and Amanda Nelson for their assistance.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by Robert D. and Patricia E. Kern Center for the Science of Health Care Delivery at Mayo Clinic and through collaboration with USAgainstAlzheimer’s.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Adams T, & Gardiner P (2005). Communication and interaction within dementia care triads: Developing a theory for relationship-centred care. Dementia, 4, 185–205. [Google Scholar]

- Barello S, Savarese M, & Graffigna G (2015). The role of caregivers in the elderly healthcare journey: Insights for sustaining elderly patient engagement In Graffigna G, Barello S, & Triberti S (Eds.), Patient engagement: A consumer-centered model to innovate healthcare (pp. 108–119). Berlin, Germany: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Beach MC, Inui T, & Relationship-Centered Care Research Network. (2006). Relationship-centered care: A constructive reframing. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 21(S1), S3–S8. doi: 10.1111/J.1525-1497.2006.00302.X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boehmer K, Egginton JS, Branda ME, Kryworuchko J, Bodde A, Montori VM, & Leblanc A (2014). Missed opportunity? Caregiver participation in the clinical encounter: A videographic analysis. Patient Education and Counseling, 96, 302–307. doi: 10.1016/J.Pec.2014.05.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borson S, & Chodosh J (2014). Developing dementia-capable health care systems: A 12-step program. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine, 30, 395–420. doi: 10.1016/J.Cger.2014.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley E, Curry L, & Devers KJ (2007). Qualitative data analysis for health services research: Developing taxonomy, themes, and theory. Health Services Research, 42, 1758–1772. doi: 10.1111/J.1475-6773.2006.00684.X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns KK, Bellows M, Eigenseher C, & Gallivan J (2014). “Practical” resources to support patient and family engagement in healthcare decisions: A scoping review. BMC Health Services Research, 14(1), Article 175. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid. (2015). Chronic care management services. Retrieved from https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-Mln/Mlnproducts/Downloads/Chroniccaremanagement.Pdf.

- Conde-Sala JL, Garre-Olmo J, Turró-Garriga O, Vilalta-Franch J, & López-Pousa S (2010). Differential features of burden between spouse and adult-child caregivers of patients with Alzheimer’s disease: An exploratory comparative design. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 47, 1262–1273. doi: 10.1016/J.Ijnurstu.2010.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulter A, & Ellins J (2007). Effectiveness of strategies for informing, educating, and involving patients. BMJ, 335, 24–27. doi: 10.1136/Bmj.39246.581169.80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demiris G, Oliver DP, & Wittenberg-Lyles E (2009). Assessing caregivers for team interventions (ACT): A new paradigm for comprehensive hospice quality care. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine®, 26, 128–134. doi: 10.1177/1049909108328697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy B, Smith K, Terhanian G, & Bremer J (2005). Comparing data from online and face-to-face surveys. International Journal of Market Research, 47, 615–639. doi: 10.1177/147078530504700602 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elwyn G, Hutchings H, Edwards A, Rapport F, Wensing M, Cheung W-Y, & Grol R (2005). The OPTION Scale: Measuring the extent that clinicians involve patients in decision-making tasks. Health Expectations, 8, 34–42. doi: 10.1111/J.1369-7625.2004.00311.X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frampton SB, Guastello S, Hoy L, Naylor M, Sheridan S, & Johnston-Fleece M (2017). Harnessing evidence and experience to change culture: A guiding framework for patient and family engaged care (Nam Perspectives Discussion Paper, pp. 1–38). Washington, DC: National Academy of Medicine; Retrieved from https://nam.edu/harnessing-evidence-and-experience-to-change-culture-a-guiding-framework-for-patient-and-family-engaged-care/ [Google Scholar]

- Groen van de Ven L, Smits C, Elwyn G, Span M, Jukema J, Eefsting J, & Vernooij-Dassen M (2017). Recognizing decision needs: First step for collaborative deliberation in dementia care networks. Patient Education and Counseling, 100, 1329–1337. doi: 10.1016/J.Pec.2017.01.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan DB, Bailey P, Black S, Carswell A, Chertkow H, Clarke B, & Thorpe L (2008). Diagnosis and treatment of dementia: 4—Approach to management of mild to moderate dementia. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 179, 787–793. doi: 10.1503/Cmaj.070803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard B (2018). Kindness in the curriculum. Retrieved from https://news.aamc.org/medical-education/article/putting-kindness-curriculum/

- Karnieli-Miller O, Werner P, Neufeld-Kroszynski G, & Eidelman S (2012). Are you talking to me?! An exploration of the triadic physician-patient-companion communication within memory clinics encounters. Patient Education and Counseling, 88, 381–390. doi: 10.1016/J.Pec.2012.06.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger R, & Casey MA (2014). Focus groups: A practical guide for applied research. Washington, DC: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Laidsaar-Powell R, Butow PN, Bu S, Charles C, Gafni A, Lam WWT, & Tattersall MHN (2013). Physician-patient-companion communication and decision-making: A systematic review of triadic medical consultations. Patient Education and Counseling, 91, 3–13. doi: 10.1016/J.Pec.2012.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louie AK, Coverdale JH, Balon R, Beresin EV, Brenner AM, Guerrero A, & Roberts LW (2018). Enhancing empathy: A role for virtual reality? Academic Psychiatry, 42, 747–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons K, & Lee C (2018). The theory of dyadic illness management. Journal of Family Nursing, 24, 8–28. doi: 10.1177/1074840717745669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. (2015). Report to the congress: Medicare and the health care delivery system. Washington, DC: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Miller L, Whitlatch C, & Lyons K (2016). Shared decision-making in dementia: A review of patient and family carer involvement. Dementia, 15, 1141–1157. doi: 10.1177/1471301214555542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitnick S, Leffler C, & Hood VL (2010). Family caregivers, patients and physicians: Ethical guidance to optimize relationships. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 25, 255–260. doi: 10.1007/S11606-009-1206-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Northouse L, Williams A-L, Given B, & Mccorkle R (2012). Psychosocial care for family caregivers of patients with cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 30, 1227–1234. doi: 10.1200/Jco.2011.39.5798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton MQ (2002). Qualitative research and evaluation methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Reisner SL, Randazzo RK, White Hughto JM, Peitzmeier S, Dubois LZ, Pardee DJ, … Potter J (2017). Sensitive health topics with underserved patient populations: Methodological considerations for online focus group discussions. Qualitative Health Research, 28, 1658–1673. doi: 10.1177/1049732317705355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rupert DJ, Poehlman JA, Hayes JJ, Ray SE, & Moultrie RR (2017). Virtual versus in-person focus groups: Comparison of costs, recruitment, and participant logistics. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 19(3), e80. doi: 10.2196/Jmir.6980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadak T, Wright J, & Borson S (2018). Managing your loved one’s health: Development of a new care management measure for dementia family caregivers. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 37, 620–643. doi: 10.1177/0733464816657472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schilling LM, Scatena L, Steiner JF, Albertson GA, Lin CT, Cyran L, & Anderson RJ (2002). The third person in the room: Frequency, role, and influence of companions during primary care medical encounters. Journal of Family Practice, 51, 685–692. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skelton K, Evans R, Lachenaye J, Amsbary J, Wingate M, & Talbott L (2018). Utilization of online focus groups to include mothers: A use-case design, reflection, and recommendations. Digital Health, 4. doi: 10.1177/2055207618777675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speice J, Harkness J, Laneri H, Frankel R, Roter D, Kornblith AB, & Holland JC (2000). Involving family members in cancer care: Focus group considerations of patients and oncological providers. Psycho-Oncology, 9, 101–112. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stacey D, Murray MA, Légaré F, Sandy D, Menard P, & O’Connor A (2008). Decision coaching to support shared decision making: A framework, evidence, and implications for nursing practice, education, and policy. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing, 5, 25–35. doi: 10.1111/J.1741-6787.2007.00108.X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swetenham K, Tieman J, Butow P, & Currow D (2015). Communication differences when patients and caregivers are seen separately or together. International Journal of Palliative Nursing, 21, 557–563. doi: 10.12968/Ijpn.2015.21.11.557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swetenham K, Tieman J, & Currow D (2014). Do patients and carers find separate palliative care clinic consultations acceptable? A pilot study. International Journal of Palliative Nursing, 20, 301–305. doi: 10.12968/Ijpn.2014.20.6.301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitlatch CJ, Heid AR, Femia EE, Orsulic-Jeras S, Szabo S, & Zarit SH (2019). The support, health, activities, resources, and education program for early stage dementia: Results from a randomized controlled trial. Dementia, 18, 2122–2139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittenberg-Lyles E, Oliver DP, Demiris G, Burt S, & Regehr K (2010). Inviting the absent members: Examining how caregivers’ participation affects hospice team communication. Palliative Medicine, 24, 192–195. doi: 10.1177/0269216309352066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff J (2012). Family matters in health care delivery. JAMA, 308, 1529–1530. doi: 10.1001/Jama.2012.13366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff J, Darer J, Berger A, Clarke D, Green J, Stametz RA, & Walker J (2017). Inviting patients and care partners to read doctors’ notes: Opennotes and shared access to electronic medical records. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 24(e1), e166–e172. doi: 10.1093/Jamia/Ocw108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff J, & Roter D (2011). Family presence in routine medical visits: A meta-analytical review. Social Science & Medicine, 72, 823–831. doi: 10.1016/J.Socscimed.2011.01.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaffe M, Orzeck P, & Barylak L (2008). Family physicians’ perspectives on care of dementia patients and family caregivers. Canadian Family Physician, 54, 1008–1015. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zielke M, Zakhidov D, Hardee G, Evans L, Lenox S, Orr N, & Mathialagan G (2017, April 2–4). Developing virtual patients with VR/AR for a natural user interface in medical teaching Paper presented at the 2017 IEEE 5th International Conference on Serious Games and Applications for Health (SeGAH), Perth, WA. [Google Scholar]